A Comprehensive Guide to Lipidomics Workflows: From Sample Collection to Data Analysis

This article provides a detailed guide to lipidomics workflows, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Lipidomics Workflows: From Sample Collection to Data Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide to lipidomics workflows, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from lipid classification and the importance of proper sample collection to the intricacies of mass spectrometry-based analysis. The scope extends to methodological choices between LC-MS and shotgun lipidomics, advanced data processing with machine learning, and critical steps for troubleshooting, quality control, and validation to ensure reproducible and biologically relevant results.

Understanding the Lipidome: Core Concepts and Pre-Analytical Planning

Lipids are ubiquitous biomolecules that constitute a highly diverse class of metabolites, serving as crucial structural components of cell membranes, acting as signaling molecules, and providing a dense energy source for cellular functions [1] [2]. Their fundamental roles extend to regulating critical biological processes including cell proliferation, survival, death, and intercellular interactions [3]. The structural diversity of lipids arises from variations in their head groups and aliphatic chains, which differ in length, unsaturation, double bond position, cis-trans isomerism, and branched chains, contributing to their complex physicochemical properties and functional versatility [3].

In 2005, the LIPID MAPS consortium established a comprehensive classification system that categorizes lipid molecular species into eight major categories: fatty acids (FA), glycerolipids (GL), glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP), sterol lipids (ST), prenol lipids (PR), saccharolipids (SL), and polyketides (PK) [3]. This systematic organization has enabled more standardized research and communication within the lipidomics community. Beyond their foundational roles in membrane structure, lipids function as essential signaling molecules in inflammation and immune responses, and participate in key cellular processes including division, growth, migration, and apoptosis [4]. The growing understanding of how different lipid types influence health and disease has positioned lipidomics as a critical field in medical research, particularly for understanding pathological mechanisms and developing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [3].

Lipid Functions in Cellular Systems and Organisms

Key Functional Roles of Lipid Classes

Table 1: Major Lipid Classes and Their Primary Biological Functions

| Lipid Category | Main Subclasses | Primary Biological Functions | Role in Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylcholine (PC), Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Basic skeleton of cell membrane; cell integrity and relative independence [3] | Membrane dysfunction in metabolic and neurological disorders |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramides (CER), Sphingomyelins (SM), Hexosylceramide (HCER) | Powerful signaling molecules regulating inflammation, cell death, and metabolic processes [5] | Elevated ceramides strongly predict cardiovascular events and correlate with insulin resistance [5] |

| Glycerolipids | Triacylglycerols (TAG), Diacylglycerols (DAG) | Energy source for cells; maintain basic cellular activities and functions [3] | Dysregulation linked to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance [6] |

| Sterol Lipids | Cholesterol, Cholesterol Esters (CE) | Membrane fluidity regulation; precursor for steroid hormones | Atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease |

| Fatty Acids | Saturated, Unsaturated, Polyunsaturated | Energy substrates; precursors for signaling molecules; membrane composition | Inflammation regulation; roles in chronic diseases [6] |

Signaling and Metabolic Functions

Lipids play dynamic roles as signaling molecules and metabolic regulators. Specific lipid species function as secondary signaling molecules, with examples including arachidonic acid and lysophospholipids that participate in complex cellular communication networks [3]. Recent research has revealed that lipids have crucial roles in immune homeostasis and inflammation regulation, with dynamic changes observed in the plasma lipidome during respiratory viral infection, insulin resistance, and ageing [6].

Ether-linked lipids, including alkyl- and alkenyl- (plasmalogen) substituent containing lipids such as PE-O and PE-P, demonstrate distinct behavior from their ester-linked counterparts, suggesting unique physiological functions that are currently under investigation [6]. These lipids appear to have specialized roles in cellular signaling and membrane properties that may be particularly important in neurological function and oxidative stress response.

The complexity of lipid functions is further exemplified by the distinct physiological roles of lipid subclasses such as large and small triacylglycerols, which comprise ≤48 and ≥49 carbons across all fatty acids, respectively. These subclasses exhibit significant differences in variance and abundance distribution, suggesting specialized metabolic roles and regulation [6].

Lipidomic Workflows: From Sample Collection to Data Analysis

Sample Collection and Preparation Techniques

Proper sample collection and preparation are critical steps in lipidomic workflows to ensure accurate and reproducible results. Blood sampling protocols have been standardized for lipidomic analysis, typically requiring fasting samples collected in specialized tubes that prevent lipid oxidation [5]. For single-cell lipidomics, capillary sampling methods have been developed that enable user-selected sampling of individual cells, providing detailed lipid profiles that reveal critical differences between cell types and states [7].

Table 2: Sample Collection Methods in Lipidomics

| Method | Application Context | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venous Blood Collection | Clinical lipid profiling; biomarker studies | Standardized protocols; specialized anti-oxidant tubes; fasting samples | [5] |

| Capillary Sampling | Single-cell lipidomics | Enables living whole-cell extraction; minimal perturbation; real-time analysis | [7] |

| Volumetric Absorptive Microsampling (VAMS) | Remote sampling; longitudinal studies | Small blood volumes; improved quantification; dried blood spots | [8] |

| Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) | Tissue-specific lipidomics | Spatially resolved sampling; specific cell populations from tissue sections | [7] |

Recent advances in microsampling technologies have enabled lipidomic profiling from minimal sample volumes. Methods such as dried blood spots (DBS), quantitative dried blood spots (qDBS), and volumetric absorptive microsampling (VAMS) facilitate global lipidomic profiling of human whole blood using high-throughput LC-MS approaches [8]. These techniques are particularly valuable for longitudinal studies, pediatric populations, and situations where sample volume is limited.

For single-cell lipidomics, both manual and automated capillary sampling methods have been developed. Manual capillary sampling is typically performed under ambient conditions using capillary tips mounted on a nanomanipulator with cell selection under an inverted microscope [7]. Automated systems such as the Yokogawa SS2000 Single Cellome System offer controlled conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) with humidity control, enhancing reproducibility [7]. Critical parameters affecting lipid profiling include capillary tip type, aspiration volume, and appropriate blank correction, while sampling medium selection shows minimal impact [7].

Lipid Extraction and Analysis Methods

Lipid extraction represents a crucial step in sample preparation, with recent developments focusing on high-throughput methodologies. Novel approaches include single-phase lipid extraction using 1-octanol and methanol with 10mM ammonium formate as a carrier solvent, enabling efficient extraction of multiple lipid classes including phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and sphingomyelin, with extraction recoveries typically between 89% and 95% [9].

Advanced mass spectrometry platforms have significantly enhanced lipidomic capabilities. The Echo MS+ system, an acoustic ejection (AE) system coupled with mass spectrometry, offers a high-throughput, contactless workflow for comprehensive lipid profiling, operating at speeds as fast as 4 seconds per sample for targeted lipid panels [9]. This technology enables minimal solvent volumes and small nanoliter extracts while maintaining sensitivity and minimizing variability.

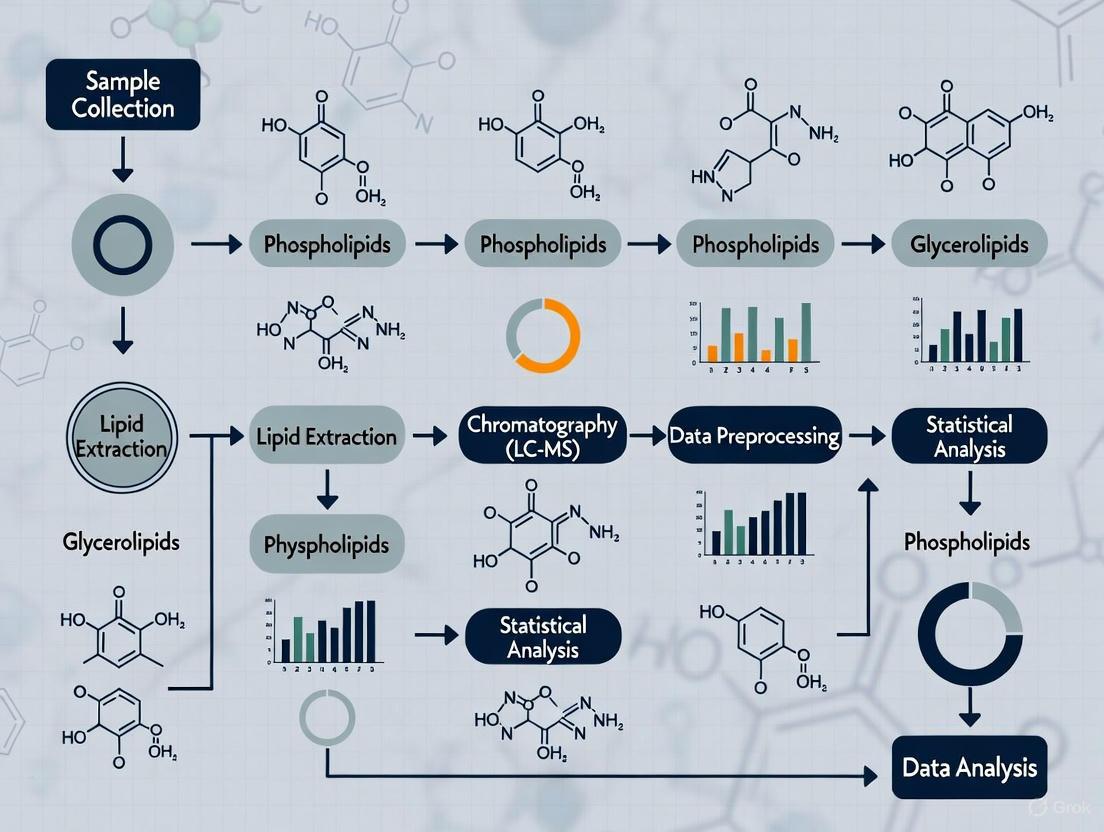

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Lipidomics Workflow from Sample to Analysis. This workflow outlines the major steps in lipidomic analysis, from sample preparation through data processing and application.

Analytical Approaches in Lipidomics

Lipidomics employs three primary analytical strategies, each with distinct applications and advantages:

Untargeted Lipidomics provides comprehensive, unbiased analysis of all detectable lipids in a sample. This approach utilizes high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) techniques including Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (Q-TOF MS), Orbitrap MS, and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance MS [3]. Data acquisition modes such as data-dependent acquisition (DDA), information-dependent acquisition (IDA), and data-independent acquisition (DIA) enable broad lipid coverage, making untargeted approaches particularly suitable for discovering novel lipid biomarkers and exploratory studies [3].

Targeted Lipidomics focuses on precise identification and quantification of specific, pre-defined lipid molecules with higher accuracy and sensitivity. This approach typically employs techniques such as ultra-performance liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (UPLC-QQQ MS) operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) or parallel-reaction monitoring modes [3]. Targeted lipidomics is often used to validate potential biomarkers identified through initial untargeted screens and for rigorous quantitative analysis of specific lipid pathways.

Pseudo-targeted Lipidomics represents a hybrid approach that combines the comprehensive coverage of untargeted methods with the quantitative rigor of targeted techniques. This method uses information from initial untargeted analyses to develop targeted methods that achieve high coverage while maintaining quantitative accuracy [3]. Pseudo-targeted approaches offer high sensitivity, reliability, and good coverage, making them suitable for studying metabolic characteristics in complex diseases.

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics in Lipidomics

Statistical Processing and Visualization

The analysis of lipidomics data presents unique challenges due to the complexity and high-dimensionality of lipidomic datasets. Recent advances have addressed the need for standardized guidance for statistical processing and visualization in lipidomics and metabolomics [10]. Modern workflows utilize R and Python packages to perform critical steps including normalization, imputation, scaling, and visualization in a transparent and reproducible manner.

Essential statistical approaches include:

- Data normalization: Standards-based normalization accounting for analytical response factors and sample preparation variability

- Batch effect correction: Advanced algorithms such as LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) and SERRF (Systematic Error Removal using Random Forest)

- Missing value imputation: Investigation of underlying causes of missingness rather than automatic imputation

- Multivariate statistics: Principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA)

Effective visualization techniques are crucial for interpreting lipidomics data. Recommended approaches include box plots with jitter or violin plots instead of traditional bar charts, volcano plots for differential analysis, dendrogram-heatmap combinations for visualizing sample clustering, and specialized visualizations such as lipid maps and fatty acyl-chain plots that reveal trends within lipid classes [10]. Dimensionality reduction techniques including PCA and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) support unsupervised data exploration and pattern recognition.

The lipidomics community has developed comprehensive resources to support data analysis and interpretation:

- LIPID MAPS Database: Provides reference information on lipid structures, taxonomy, and pathways

- Metabolights: Public repository for metabolomics and lipidomics data

- Lipidomics Standards Initiative: Develops and promotes standards for lipidomics data

- Laboratory of Lipid Metabolism GitBook: Curated resource with R/Python code for lipidomics data analysis [10]

These resources support the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles, enabling reproducible research and collaborative science in the lipidomics community [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipidomics

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | EquiSPLASH (16 ng mL−1), deuterated spike-in standards (54-component mix) | Quantitative accuracy; normalization against extraction variance | Included at known concentrations for nine lipid subclasses [7] [6] |

| Extraction Solvents | 1-octanol, methanol, butanol, ammonium formate (10mM) | Lipid extraction from biological matrices; carrier solvent for MS | Single-phase 1-octanol/methanol extraction shows 89-95% recovery [9] |

| Antioxidants | Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Prevent lipid oxidation during sample processing | Added to internal standard solution (0.01% v/v) [7] |

| Chromatography | Reversed-phase columns, HILIC columns, mobile phase solvents | Lipid separation prior to MS detection | Reduces spectral complexity and ion suppression [7] |

| Sampling Devices | Capillary tips (10 μm), microsampling devices (Mitra) | Single-cell isolation; volumetric microsampling | Yokogawa and Humanix tips for manual/automated sampling [7] |

| Cell Culture | DMEM, FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, L-glutamine | Cell maintenance for in vitro studies | Standard cell culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) [7] |

| S 9788 | S 9788, CAS:140945-01-3, MF:C28H33F2N7, MW:505.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SB-568849 | SB-568849|GPCR Research Compound|RUO | SB-568849 is a high-purity compound for GPCR and neuropharmacology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Lipid Alterations in Disease and Clinical Applications

Lipidomics in Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases

Comprehensive longitudinal lipidomic profiling has revealed dynamic alterations in the plasma lipidome associated with human health, disease, and ageing [6]. Studies analyzing >1,500 plasma samples from 112 participants followed for up to 9 years have identified distinct lipid signatures associated with health-to-disease transitions in diabetes, ageing, and inflammation.

Key findings include:

- Individuals with insulin resistance exhibit disturbed immune homeostasis and altered associations between lipids and clinical markers

- Accelerated changes in specific lipid subclasses occur during ageing in insulin-resistant individuals

- Dynamic changes in the plasma lipidome are observed during respiratory viral infection

- Lipid-cytokine networks demonstrate complex interactions between inflammatory mediators and lipid species

These findings suggest that lipids play roles in immune homeostasis and inflammation regulation, potentially guiding future monitoring and intervention strategies [6]. The highly personalized nature of lipid signatures, with intraparticipant variance consistently lower than interparticipant variance, highlights the potential for personalized approaches to disease management [6].

Lipidomics in Cancer and Gynecological Diseases

Lipidomics has shown significant promise in oncology, particularly in gynecological cancers where delayed diagnosis often impacts patient outcomes. In ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, and endometriosis, lipidomics offers new technical pathways for identifying potential biomarkers and understanding disease mechanisms [3].

Lipid metabolism is reprogrammed in cancer to support the energy demands of rapidly proliferating cancer cells [3]. Specific alterations include:

- Changes in phospholipid and sphingolipid profiles that may serve as early detection biomarkers

- Modifications in glycerophospholipid metabolism that influence membrane composition and signaling

- Alterations in eicosanoid and related lipid mediators that affect cancer-related inflammation

- Changes in sphingolipid ceramides that regulate cell death and survival pathways

These lipid alterations provide insights into cancer pathogenesis and offer opportunities for developing diagnostic tools and targeted therapeutic interventions [3].

Clinical Translation and Precision Health

Lipid profiling has demonstrated superior predictive capability for disease onset compared to genetic markers alone, with studies showing lipid profiles can predict disease 3-5 years earlier than genetic markers [5]. This early predictive capability has significant clinical implications, enabling earlier interventions and improved outcomes.

Clinical applications of lipidomics include:

- Personalized lipid analysis: Driving treatment decisions beyond genetic testing, with lipid-focused interventions showing 43% greater improvement in insulin sensitivity compared to genetic-based approaches [5]

- Therapeutic monitoring: Tracking lipid changes in response to interventions

- Risk stratification: Ceramide risk scores outperforming traditional cholesterol measurements in predicting cardiovascular events [5]

- Drug delivery systems: Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) technology enabling precise targeting of medications to specific tissues and cells, particularly in oncology [5]

The integration of lipidomics with other omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) provides a comprehensive view of biological systems and enhances our understanding of disease mechanisms, supporting the development of precision medicine approaches [3].

Lipid diversity encompasses a vast array of molecular species with essential functions in cellular structure, signaling, and metabolism. The field of lipidomics has evolved rapidly, driven by technological advances in mass spectrometry, chromatography, and bioinformatics. Comprehensive lipidomic workflows now enable detailed characterization of lipid alterations associated with human health, disease, and ageing, providing insights into physiological and pathological processes.

The clinical translation of lipidomics is already demonstrating significant potential, with lipid-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies outperforming traditional approaches for various conditions. As standardization improves and analytical technologies advance, lipidomics is poised to become an increasingly integral component of precision medicine, offering personalized insights into health and disease management.

Future directions include increased automation in lipid annotation, AI-driven feature assignment, closer integration with separation methods, and the development of scalable preprocessing approaches to handle increasing data volumes. These advances will further enhance our understanding of lipid diversity and function, opening new possibilities for diagnostic and therapeutic innovation.

Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, has evolved into a distinct discipline dedicated to the comprehensive study of lipid molecules within biological systems [11]. Lipids are crucial cellular components, serving not only as structural elements of membranes but also as energy storage molecules and signaling mediators [12] [13]. The structural diversity of lipids—with over 180,000 possible species at the fatty acid constituent level—presents unique analytical challenges that require sophisticated workflows to unravel [14]. Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as the cornerstone technology for modern lipidomics due to its unparalleled sensitivity, selectivity, and versatility [13] [15]. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step overview of the lipidomics workflow, framed within the context of methodological research from sample collection to data analysis, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in implementing robust lipidomics protocols.

Sample Collection and Preparation

Initial Collection Considerations

The foundation of any successful lipidomics study lies in proper sample collection and handling. Immediate processing or flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen is crucial, as enzymatic and chemical processes can rapidly alter lipid profiles post-collection [12]. For instance, leaving plasma samples at room temperature can artificially increase concentrations of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) [12]. Storage at -80°C is recommended for long-term preservation, though even at this temperature, storage duration should be minimized to prevent degradation [16] [12].

To minimize enzymatic activity and lipid degradation during collection, several strategies are effective:

- Use of appropriate anticoagulants (e.g., EDTA or heparin) for blood samples [16]

- Rapid processing and snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen for tissues [16]

- Immediate placement of samples on ice during handling [16]

- Incorporation of antioxidants like butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) in extraction solvents to prevent oxidation, particularly for polyunsaturated fatty acids [14] [16]

Sample Homogenization

Homogenization methods must be tailored to sample type to ensure equal solvent accessibility to all lipids:

- Biofluids (serum, plasma): Homogenization is typically minimal [12]

- Tissue samples: Shear-force-based grinding with Potter-Elvehjem homogenizers or ULTRA-TURRAX systems in solvent, or crushing of liquid-nitrogen-frozen tissue using pestle and mortar [12]

- Cells: Disruption via pebble mill with beads or nitrogen cavitation bomb [12]

For tissue samples, recording the exact weight of tissue powder is critical as subsequent extraction volumes are adjusted based on this weight (typically 20 times the tissue weight in mg) [14].

Lipid Extraction Techniques

Several liquid-liquid extraction methods are commonly employed in lipidomics, each with distinct advantages:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Lipid Extraction Methods

| Method | Solvent Ratio | Phase Containing Lipids | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folch [17] | Chloroform:methanol:water (8:4:3, v/v/v) [14] | Lower organic phase (chloroform) | Well-established standard; high extraction efficiency | Use of hazardous chloroform; difficult automation |

| Bligh & Dyer [13] | Chloroform:methanol:water (1:2:0.8, v/v/v) | Lower organic phase (chloroform) | Suitable for small sample amounts (<50 mg tissue) | Chloroform collection from bottom layer; water-soluble impurity carry-over |

| MTBE [12] [13] | MTBE:methanol:water (5:1.5:1.45, v/v/v) | Upper organic phase (MTBE) | Easier handling; less hazardous; more feasible for automation | MTBE phase may carry water-soluble contaminants |

| BUME [12] [13] | Butanol:methanol + heptane:ethyl acetate + 1% acetic acid | Upper organic phase | Suitable for high-throughput in 96-well plates; avoids chloroform | Difficulty evaporating butanol component |

The Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods remain the most widely used protocols, though MTBE extraction is gaining popularity due to easier handling and reduced health concerns [12]. For specialized applications, solid-phase extraction (SPE) can be employed to purify or enrich specific lipid classes using normal phase silica gel, reverse phase (C8, C18), or ion exchange columns [17].

Internal Standards and Quality Control

Incorporation of internal standards is critical for quantitative lipidomics. These should be added prior to extraction to account for variations in extraction efficiency and matrix effects [14] [13]. A combination of class-representative internal standards is recommended, such as:

- Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC 17:0, LPC 19:0)

- Phosphatidylcholine (PC 17:0/17:0, PC 19:0/19:0)

- Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE 15:0/15:0, PE 17:0/17:0)

- Triacylglyceride standards (TG 15:0/15:0/15:0, TG 17:0/17:0/17:0) [14]

Quality control procedures should include:

- Pooled quality control samples from all study samples [14]

- Standard reference materials (e.g., NIST SRM) [14] [18]

- Extraction blanks to monitor contamination [14]

Lipidomics Workflow: From Sample to Data

The following diagram illustrates the complete lipidomics workflow, integrating both sample preparation and analytical phases:

Analytical Approaches: LC-MS-Based Lipidomics

Chromatographic Separation

Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is the predominant approach in comprehensive lipidomics [11]. Reverse-phase chromatography using C18 columns is most common, separating lipids based on class, fatty acid constituents, and even positional isomers and double bond positions [14] [11]. The separation enhances specificity, reduces ion suppression, and aids in lipid identification [14].

Table 2: Typical LC Conditions for Lipid Separation

| Parameter | Specification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Column | C18 UHPLC column [14] | C30 columns also used for enhanced isomer separation [11] |

| Mobile Phase A | Acetonitrile:water (60:40, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid [14] | Aqueous phase |

| Mobile Phase B | Isopropanol:acetonitrile:water (90:8:2, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid [14] | Organic phase |

| Gradient | Increasing organic phase (B) from 30% to 100% | Optimized for lipid class elution |

| Reconstitution | 100% isopropanol [14] | After lipid extraction and drying |

Mass Spectrometric Analysis

High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is essential for distinguishing isobaric lipid species and achieving confident identifications [14] [11]. The following diagram details the LC-MS/MS data acquisition process:

Ionization techniques: Electrospray ionization (ESI) is the most popular soft-ionization method for lipid analysis, efficiently ionizing a broad range of intact molecular structures with minimal in-source fragmentation [13] [15]. Alternative techniques include atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), the latter being particularly useful for MS imaging [13].

Tandem MS approaches: Both data-dependent acquisition (DDA) and data-independent acquisition (DIA) are employed:

- DDA: Selects most abundant precursors for fragmentation, providing rich MS/MS spectra

- DIA: Fragments all ions within selected m/z windows, providing more extensive coverage [14]

Common MS/MS techniques include product ion scan, precursor ion scan (PIS), neutral loss scan (NLS), and selected/multiple reaction monitoring (SRM/MRM) [13].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data Preprocessing

Raw MS data undergoes multiple processing steps before statistical analysis:

Feature detection and identification: Open-source software packages are commonly used for peak picking, alignment, and feature detection [14]. Lipid identification utilizes both MS and MS/MS spectra, matching fragmentation patterns against lipid databases [11].

Missing value imputation: Lipidomics datasets frequently contain missing values that require imputation strategies:

- Missing completely at random (MCAR): k-nearest neighbors (kNN) imputation recommended [18]

- Missing not at random (MNAR): Imputation using a percentage of the lowest concentration value (half-minimum method) [18]

Data normalization: Both pre-acquisition and post-acquisition normalization methods are employed:

- Pre-acquisition: Normalization to protein amount, tissue weight, cell count, or fluid volume [13] [18]

- Post-acquisition: Normalization to internal standards, quality control-based correction, or statistical normalization (sum, median, probabilistic quotient normalization) [18]

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

A combination of univariate and multivariate statistical methods is employed to extract biological insights:

Univariate methods: Analyze lipid features independently using:

- Student's t-test (for two-group comparisons)

- ANOVA (for multiple group comparisons)

- False discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing [11]

Multivariate methods: Analyze lipid features simultaneously to identify relationship patterns:

- Principal component analysis (PCA) for unsupervised pattern recognition

- Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) for supervised classification [11]

Enrichment analysis and pathway mapping: Tools like LipidSig enable enrichment analysis based on lipid class, chain length, unsaturation, and other structural characteristics [19]. This helps identify biologically relevant patterns beyond individual lipid species.

Advanced visualization: Specialized plots including volcano plots, lipid maps, and fatty acyl chain plots help visualize complex lipidomic data [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Lipidomics Research

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | LC-MS grade chloroform, methanol, MTBE, water | Lipid extraction with minimal interference |

| Internal Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX or custom mixtures | Quantification and quality control |

| LC Mobile Phase Additives | Ammonium formate, formic acid (LC-MS grade) | Enhance ionization and adduct formation |

| Antioxidants | Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Prevent oxidation of unsaturated lipids |

| UHPLC Columns | C18 (1.7-1.9 μm particle size, 100 × 2.1 mm) | Reverse-phase lipid separation |

| Quality Control Materials | NIST SRM 1950, pooled study samples | Monitor analytical performance |

| Solid Phase Extraction | Silica, C8, C18, amine columns | Lipid class-specific purification |

| Sample Tubes | Polypropylene Eppendorf/conical tubes | Prevent lipid adsorption to surfaces |

| (-)-Stylopine | (-)-Stylopine, CAS:7461-02-1, MF:C19H17NO4, MW:323.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N3-D-Dap(Fmoc)-OH | N3-D-Dap(Fmoc)-OH, MF:C18H16N4O4, MW:352.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This application note has detailed the comprehensive lipidomics workflow from sample collection to data interpretation. The critical importance of proper sample handling and preparation cannot be overstated, as these pre-analytical steps profoundly impact data quality and biological conclusions. The combination of robust chromatography with high-resolution mass spectrometry enables the separation and identification of complex lipid mixtures, while appropriate statistical approaches and bioinformatics tools extract meaningful biological insights from the resulting data. As lipidomics continues to evolve, standardization of protocols and data reporting will be essential for advancing our understanding of lipid biology and its implications in health and disease.

In lipidomics, the pre-analytical phase—encompassing sample collection, homogenization, and storage—constitutes the most critical yet vulnerable stage in the workflow. Inappropriate handling during these initial steps can induce significant artifactual changes in the lipid profile, leading to enzymatic degradation, oxidation, and hydrolysis of lipid species [20] [21]. Such alterations obscure true biological signals and compromise data integrity, making subsequent sophisticated analyses futile. This application note details standardized, evidence-based protocols designed to preserve the native lipidome from the moment of sample acquisition, providing a robust foundation for accurate lipidomic analysis in research and drug development.

Sample Collection and Immediate Pre-analytics

The initial moments following sample collection are paramount for preserving lipid integrity. Immediate action is required to quench ongoing metabolism and prevent artifactual generation of lipid species.

Key Principles for Sample Collection

- Rapid Processing: Tissues should be frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, while biofluids like plasma should be processed without delay or frozen at -80°C [20]. Prolonged exposure to room temperature accelerates enzymatic and chemical degradation processes such as lipid peroxidation or hydrolysis [20] [21].

- Inhibition of Degradation: For specific lipid classes like lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), which are generated instantly post-sampling, special precautions are required to preserve in vivo concentrations [20]. Lipolytic activity can continue even after the addition of organic solvents [20].

- Matrix-Specific Considerations: Different sample types demand tailored approaches. For instance, blood plasma collected with EDTA anticoagulant is preferred, and the potential for zonal distribution of lipids in tissues like liver must be accounted for during sampling [22] [14].

Table 1: Recommended Sample Collection Procedures by Sample Type

| Sample Type | Primary Collection Method | Immediate Processing | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen [22] [14] | Homogenize or powder while frozen | Minimize sample heating; ensure representativity [22]. |

| Blood Plasma/Serum | Draw into EDTA tubes; centrifuge to separate [14] | Aliquot and freeze at -80°C | Plasma is generally preferred; note LPA/S1P generation in serum [20]. |

| Mammalian Cells | Pellet cells at 311 × g for 5 min at 4°C [14] | Wash with cold buffer; freeze pellet at -80°C | Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Latent Fingerprints (Sebum) | Deposit on foil [23] | Process immediately or store foil at -20°C | A non-invasive method for specific lipid classes like TAG and WE [23]. |

Preventing Specific Lipid Artefacts

- Oxidation: To prevent oxidation, add Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) to extraction solvents [14]. Protect samples from light and oxygen by storing in airtight containers [21] [24]. Lipids with polyunsaturated fatty acyl chains (PUFAs) are particularly susceptible [21].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Enzymes like phospholipases (PLA1, PLA2, PLD) and lipases can hydrolyze lipids, generating artifacts like lysophospholipids and free fatty acids [21]. Immediate denaturation using organic solvents or heat is effective.

- Hydrolysis and Isomerization: In samples kept at room temperature and pH >6, scrambling of fatty acyls in lysophospholipids can occur, resulting in a loss of regioisomeric specificity [20].

Tissue Homogenization and Lipid Extraction

The goal of homogenization and extraction is to achieve complete and unbiased recovery of all lipid classes from the complex biological matrix. The method chosen significantly influences the final analytical outcome [22].

Homogenization Techniques

Two primary homogenization methods are commonly employed, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

- Grinding in Liquid Nitrogen: This method, using a mortar and pestle, is considered a gold standard for tissues. It minimizes sample heating and provides a homogeneous powder representing the overall lipid composition, which is ideal for experiments requiring identical source material [22] [14].

- Bead-Based Homogenization: This approach is performed directly in organic solvents and is advantageous for high-throughput studies due to its simplicity and throughput capabilities [22]. Studies show bead-based homogenization results in efficient lipid recovery independent of solvent composition, unlike grinding methods [22].

Solvent Selection and Extraction Protocols

The choice of solvent system is critical for efficient lipid recovery. No single solvent perfectly extracts all lipid classes, so the protocol must be matched to the target lipids [20] [25].

- Classical Biphasic Methods: These methods, such as Folch (chloroform:methanol:water, 8:4:3, v/v/v) and Bligh & Dyer, are the gold standards for comprehensive lipid extraction [20] [14]. The MTBE (methyl-tert-butyl ether) method is a less toxic alternative that provides good recovery for many lipid classes [20] [25].

- Monophasic Methods: These are simpler and more amenable to automation but may not provide the same broad lipid coverage as biphasic methods and can lead to selective loss of nonpolar lipids [20].

- Green Solvent Alternatives: Recent research identifies Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) and 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) as sustainable, less hazardous alternatives to chloroform with comparable or even superior extraction efficiency for human plasma [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Lipid Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Solvent Composition | Recommended Application | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folch [14] | Chloroform:MeOH:Water (8:4:3, v/v/v) | Comprehensive lipidomics; broad lipid classes [20] [14] | Pro: High recovery of polar & nonpolar lipids.Con: Chloroform toxicity. |

| Bligh & Dyer [22] | Chloroform:MeOH:Water (1:2:0.8, v/v/v) | Polar lipids (e.g., phospholipids); acidic lipids with protocol adjustment [20] | Pro: Slightly better for polar lipids.Con: Lower nonpolar lipid recovery vs. Folch. |

| MTBE [25] | MTBE:MeOH:Water (10:3:2.5, v/v/v) | Broad lipid profiling; high-throughput needs [20] | Pro: Reduced toxicity; good recovery.Con: May require optimization for specific classes. |

| CPME-based [25] | MeOH/MTBE/CPME (1.33:1:1, v/v/v) | Sustainable alternative to chloroform methods. | Pro: Greener, safer, comparable performance.Con: Relatively new, requires validation. |

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key decision points and steps in the sample preparation process.

Sample Storage Protocols

Proper storage conditions are essential for maintaining lipid stability over time, especially in large-scale studies where samples may be stored for weeks or months before analysis [21].

Storage of Intact Samples and Lipid Extracts

- Intact Tissues and Biofluids: Must be stored at -80°C for long-term preservation [20] [14]. The stability of specific lipid classes under these conditions should be verified for the studied species [20].

- Lipid Extracts: After preparation, dried lipid extracts should be reconstituted and stored in organic solvents with antioxidants like BHT at -20°C or lower in an airtight container without exposure to light or oxygen [21] [24]. This reduces sublimation and chemically/physical induced transformations.

- Alternative Storage for Specific Samples: For latent fingerprint samples, storing the foil deposits directly at -20°C and delaying extraction until analysis is a viable option, minimizing batch-to-batch variability [23].

Quality Control and Stability Assessment

Integrating quality control measures is mandatory for monitoring lipid stability.

- Internal Standards: Add a cocktail of synthetic lipid internal standards prior to homogenization and extraction to correct for losses during sample preparation and analysis [20] [14].

- Stability Markers: Monitor known degradation markers, such as specific lysophospholipids (e.g., LPC 18:2) or sphingosine-1-phosphate, to assess sample quality and pre-analytical variation [21].

- Pooled Quality Controls (QCs): Create a pooled QC sample from an aliquot of all samples to analyze throughout the batch, allowing for the monitoring of instrumental performance and data quality [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, solvents, and materials crucial for implementing robust pre-analytical protocols in lipidomics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipidomics Sample Preparation

| Item | Function & Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | Corrects for extraction efficiency & MS variability; enables quantification [14]. | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX (Avanti); class-specific standards (e.g., PC 17:0/17:0, TG 17:0/17:0/17:0) [22] [14]. |

| Chloroform | Primary solvent in Folch/Bligh & Dyer; dissolves broad lipid range [20] [14]. | Health Warning: Toxic—use in fume hood. Consider greener alternatives like CPME [25]. |

| Methanol | Disrupts H-bonds, denatures proteins, quenches enzymes [25]. | LC-MS grade recommended to avoid contaminants. |

| Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Less toxic alternative for chloroform in biphasic extraction [20] [25]. | Used in MTBE-based extraction protocols [25]. |

| Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) | Green solvent alternative to chloroform [25]. | Shows comparable/superior performance to Folch in some applications [25]. |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Antioxidant added to solvents to inhibit lipid oxidation [21] [14]. | Typical concentration: 1 mM in extraction methanol [14]. |

| Bead Homogenizer | Efficient tissue/cell disruption directly in solvent (e.g., Precellys) [22]. | Uses ceramic/zirconium oxide beads (soft tissue) or stainless steel (hard tissue) [14]. |

| Mortar and Pestle | Grinding frozen tissue in liquid nitrogen for homogenization [22] [14]. | Provides homogenous powder; minimizes heating. |

| Polypropylene Tubes | Sample storage and extraction; prevents lipid adhesion [14]. | Preferred over glass for certain applications to avoid analyte binding. |

| Formic Acid / Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additives for LC-MS to improve ionization and separation [14] [26]. | Concentration typically 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate [14]. |

| E3 ligase Ligand 8 | E3 ligase Ligand 8, MF:C31H34N2O6, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tigloside | Tigloside, CAS:216590-44-2; 3625-57-8, MF:C54H78O27, MW:1159.191 | Chemical Reagent |

{#introduction}

Lipid extraction is a critical first step in the lipidomics workflow, serving as the foundation for accurate and reproducible mass spectrometry analysis. The efficiency and selectivity of the extraction protocol directly influence the depth and coverage of the subsequent lipidomic profile. This Application Note provides a detailed overview and comparison of three major lipid extraction techniques: the classical Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods, which utilize chloroform/methanol, and the increasingly popular methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) method. Understanding the principles, advantages, and limitations of each technique is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal protocol for their specific biological sample, ensuring a robust lipidomic workflow from sample collection to data analysis [27] [28].

{##key-techniques}

Key Techniques and Comparative Analysis

{###comparison-table}

Comparative Analysis of Lipid Extraction Methods

The following table summarizes the key parameters of the three major lipid extraction techniques, facilitating a direct comparison for method selection.

| Parameter | Folch Method [29] [28] [30] | Bligh & Dyer Method [28] [31] | MTBE Method [32] [33] [34] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Solvent System | Chloroform/Methanol (2:1, v/v) [29] [30] | Chloroform/Methanol/Water (1:2:0.8, v/v/v) [31] | MTBE/Methanol/Water (varies; e.g., 8:2:2, v/v/v) [33] [35] |

| Sample Type | Tissues, cells, fluids [28] | Liquid samples, homogenates, cell suspensions [31] | Plasma, cells, tissues, CSF [33] [34] [35] |

| Phase Separation | Organic (lower) phase contains lipids [28] | Organic (lower) phase contains lipids [31] | Organic (upper) phase contains lipids [32] [34] |

| Key Advantage | Considered the "gold-standard"; more accurate for samples with >2% lipid content [31] | Rapid; suitable for samples with high water content [31] | Faster, cleaner recovery; safer solvent; easier collection of upper organic phase [32] |

| Limitation | Uses toxic chloroform; more complex phase collection [28] | Underestimates lipid content in fatty samples (>2% lipids) [31] | Relatively newer method compared to classical protocols [32] |

| Compatibility | High-throughput LC-MS/MS lipidomics with adaptations [28] | LC-MS/MS lipidomics [28] | Highly compatible with automated shotgun profiling and LC-MS/MS [32] [33] |

{###workflow-diagram}

Lipidomic Workflow in Research

The following diagram illustrates the position of lipid extraction within the broader context of a standardized lipidomics research workflow.

{##detailed-protocols}

Detailed Experimental Protocols

{###mtbe-protocol}

MTBE-Based Extraction Protocol

This protocol is well-suited for automated shotgun profiling and LC-MS/MS analysis, offering a safer alternative to chloroform-based methods [32] [33].

{###procedure}

Procedure

- Protein Precipitation and Extraction: To a sample (e.g., 100 µL of plasma in a 1.5 mL microtube), add 200 µL of cold methanol and vortex. Then, add 800 µL of cold methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and vortex again [33] [34].

- Incubation: Cap the tube and incubate at 2-8°C for 1 hour to ensure complete protein precipitation and lipid extraction [34].

- Phase Separation: Add 200-300 µL of water to the mixture [33] [34]. Vortex the tube for 10 seconds and then centrifuge at 4°C for 10 minutes (e.g., 10,000 × g) to achieve phase separation [33] [35].

- Organic Phase Collection: Carefully collect the upper organic phase (MTBE layer), which contains the extracted lipids, using a pipette [33] [34].

- Drying and Storage: Dry the collected organic phase under a stream of nitrogen or in a SpeedVac concentrator. Store the dried lipid extract at -80°C until analysis [33] [35].

- Reconstitution for MS: For mass spectrometry analysis, reconstitute the dried lipids in an appropriate solvent mixture, such as 20-40 µL of acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (65:30:5, v/v/v) [33].

{###folch-protocol}

Modified Folch Protocol

This is a common modification of the classical Folch method for extracting lipids from cell pellets [29].

{####procedure}

Procedure

- Solvent Addition: Add 2 mL of chloroform and 1 mL of methanol to a sample (e.g., a cell pellet resuspended in 1.5 mL of water) in a glass vial. To prevent oxidation, add the antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) at a concentration of 50 µg/mL during extraction [29].

- Acidification: Add 500 µL of 1N HCl to bring the final concentration to 0.1 N. Vortex the mixture thoroughly and incubate it on ice for 20 minutes [29].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the sample at 2,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C to separate the phases [29].

- Organic Phase Collection: Transfer the lower organic (chloroform) layer to a new tube.

- Aqueous Re-extraction: To the remaining aqueous layer, add 1.5 mL of a 2:1 chloroform:methanol solution. Vortex and centrifuge again. Combine this organic layer with the one collected in the previous step [29].

- Drying and Storage: Dry the combined organic layers under a stream of nitrogen. The dried lipid extract can be resuspended in 240 µL of a 1:1 methanol:isopropanol mixture and stored at -80°C [29].

{###bligh-dyer-protocol}

Bligh & Dyer Protocol

This method is particularly suitable for lipid extraction from incubation media, tissue homogenates, or cell suspensions [31].

{####procedure}

Procedure

- Initial Homogenization: To a sample containing 1 mL of water (e.g., cell suspension, plasma), add 3.75 mL of a chloroform/methanol (1:2, v/v) mixture. Vortex for 10-15 minutes [31].

- Partitioning: Add 1.25 mL of chloroform, mix for 1 minute, and then add 1.25 mL of water, mixing for another minute [31].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture to separate the two liquid phases. A disk of precipitated proteins will form at the interface [31].

- Organic Phase Collection: Discard the upper aqueous phase. Carefully collect the lower organic (chloroform) phase by pipetting through the protein disk [31].

- Evaporation: After evaporation of the solvent, the lipid extract can be redissolved in a small volume of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) for further analysis [31].

{##the-scientists-toolkit}

The Scientist's Toolkit

{###research-reagent-solutions}

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents used in lipid extraction protocols, along with their primary functions.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Lipid Extraction |

|---|---|

| Chloroform | Primary non-polar solvent for dissolving neutral lipids and forming the organic phase in Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods [28]. |

| Methanol | Polar solvent that disrupts lipid-protein complexes and helps in the extraction of polar lipids [28]. |

| Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Less toxic, low-density ether solvent that forms the upper organic phase in the MTBE method, enabling easier collection [32] [34]. |

| Water | Used to induce phase separation between organic and aqueous layers; hydration aids in solvent penetration [33] [28] [31]. |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Antioxidant added to the solvent mixture to prevent oxidation of unsaturated lipids during the extraction process [29]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) / Acetic Acid | Used to acidify the extraction medium, which improves the recovery of acidic phospholipids by blocking their binding to denatured proteins [29] [31]. |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., NaCl, KCl) | Salt solutions are used in washing steps to remove non-lipid contaminants from the organic extract [28] [31]. |

| Fmoc-Ala-Pro-OH | Fmoc-Ala-Pro-OH, CAS:186023-44-9, MF:C23H24N2O5, MW:408.454 |

| Jasminoside | Jasminoside, MF:C26H30O13, MW:550.5 g/mol |

{###method-selection-diagram}

Lipid Extraction Method Selection Logic

Choosing the correct extraction method is critical for success. The following decision logic aids in selecting the most appropriate protocol based on key sample and research criteria.

{##integration-workflow}

Integration into a Comprehensive Lipidomics Workflow

A robust lipidomics study extends beyond extraction. Subsequent steps, including mass spectrometric analysis and data processing, are crucial for generating high-quality, biologically meaningful data. Following extraction and LC-MS/MS analysis, the application of standardized statistical workflows in R or Python is recommended for data processing, normalization, and visualization. These tools help address challenges in reproducibility and transparency, offering modular components for diagnostic visualization (e.g., PCA, QC trends), batch effect correction, and sophisticated plots like lipid maps and volcano plots, ultimately guiding data interpretation and biological insight [10]. Adherence to guidelines from the Lipidomics Standards Initiative (LSI) throughout the entire workflow ensures data quality and interoperability across studies [10].

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks in biological systems, relies heavily on mass spectrometry (MS) for the identification and quantification of lipid species [36]. The initial and critical step of converting neutral lipid molecules into gas-phase ions is performed by the ion source, making the choice of ionization technique a cornerstone of any lipidomic workflow [37]. The structural diversity of lipids—encompassing variations in acyl chain length, double bond position, and stereochemistry—poses a significant analytical challenge. No single ionization technique is universally optimal, and the choice depends heavily on the analytical goals, the lipid classes of interest, and the chromatographic method employed [38] [37].

This article provides a detailed overview of three key ionization techniques—Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI)—within the context of a complete lipidomic workflow. We will present standardized experimental protocols and data to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate ionization method for their specific lipid analysis challenges.

Ionization techniques are broadly categorized as "hard" or "soft." Hard ionization, such as Electron Ionization (EI), uses high-energy processes that cause extensive analyte fragmentation, which is often undesirable for intact lipid analysis. In contrast, ESI, MALDI, and APCI are "soft" ionization techniques that preserve the molecular ion, making them particularly suitable for lipidomic profiling [37].

The following table summarizes the fundamental principles, strengths, and limitations of ESI, MALDI, and APCI for lipid analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Soft Ionization Techniques in Lipid Analysis

| Feature | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) | Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Spraying a solution to create charged droplets; ions form via desolvation [39] [37]. | Mixing analyte with a light-absorbing matrix; laser pulse causes desorption/ionization [40] [37]. | Nebulization and vaporization followed by gas-phase chemical ionization via corona discharge [41] [37]. |

| Ionization Mode | Solution-phase | Solid-phase | Gas-phase |

| Typical Fragmentation | Minimal in-source fragmentation | Minimal in-source fragmentation | More pronounced in-source fragmentation [41] |

| Compatibility | Direct infusion ("shotgun") or coupled with LC (especially RPLC) [42]. | Primarily used for direct analysis or mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) [40]. | Coupled with LC (compatible with normal-phase solvents like isooctane) [41]. |

| Key Strength | Excellent for polar lipids and large biomolecules; can generate multiply charged ions; high sensitivity [37] [42]. | High spatial resolution for imaging; fast analysis; relatively tolerant to salts [40] [43]. | Effective for less polar, semi-volatile, and neutral lipids (e.g., sterol esters, triacylglycerols) [41] [37]. |

| Key Limitation | Susceptible to ion suppression from matrix effects [37]. | Less suited for quantitative analysis due to matrix interference [37]. | Not ideal for thermally labile or very polar lipids (e.g., lysophospholipids) [41]. |

Detailed Techniques and Application Protocols

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) with Post-Column Lithium Adduct Enhancement

Principle: ESI works by applying a high voltage to a liquid sample, creating a fine spray of charged droplets. As the solvent evaporates, the charge concentrates until gas-phase ions of the analyte are produced. It is highly effective for a wide range of phospholipids and is the most common interface for LC-MS-based lipidomics [37] [42]. A powerful strategy to enhance the detection of certain lipid classes is the post-column infusion of lithium salts to form stable [M+Li]⺠adducts, which improves sensitivity and provides characteristic fragmentation for structural elucidation [41] [39].

Experimental Protocol: NPLC-ESI-MS with Post-Column Lithium Addition

- Sample Preparation: Extract lipids from biological samples (e.g., heart, brain, liver) using a validated liquid-liquid extraction method, such as MeOH/MTBE, which has demonstrated excellent recovery (>85%) for phospholipids [42].

- Chromatography:

- Column: Normal-phase column for lipid class separation.

- Mobile Phase: Non-polar gradient starting with solvents like isooctane, moving to more polar solvents like ethyl acetate or acetone [41].

- Post-Column Modification:

- Solution: Prepare a 0.10 mM solution of lithium chloride in a solvent compatible with both the NPLC eluent and ESI process (e.g., isopropanol) [41].

- Infusion: Use a syringe pump or a dedicated makeup flow to introduce the lithium solution post-column at an optimized flow rate.

- MS Acquisition:

- Ion Source: ESI in positive mode.

- Key Parameters: Monitor for [M+Li]⺠adducts. This method significantly enhances the detection and study of molecular species in sterol esters (SE), triacylglycerols (TG), and acylated steryl glucosides (ASG), while also improving signals for monoacylglycerols (MG) and lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) [41].

Table 2: Lipid Classes Amenable to Lithium Adduct Formation and Their Benefits

| Lipid Class | Adduct Type | Key Analytical Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Triacylglycerols (TG) | [M+Li]⺠| Stabilizes the molecular ion, enables structural analysis via tandem MS [41] [39] |

| Sterol Esters (SE) | [M+Li]⺠| Facilitates detection, which is hindered by in-source fragmentation in APCI [41] |

| Glycerophospholipids | [M+Li]⺠| "Lithium adduct consolidation" can increase sensitivity and provide informative fragments [41] [39] |

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) for Spatial Lipidomics

Principle: In MALDI, the sample is co-crystallized with a UV-absorbing organic matrix. A pulsed laser irradiates the matrix, which transfers energy to the analyte, causing desorption and ionization. A major application is MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MALDI-MSI), which allows for the label-free visualization of the spatial distribution of hundreds of lipids directly in tissue sections [40] [43].

Experimental Protocol: MALDI-MSI of Lipids in Tissue Sections

- Sample Preparation:

- Tissue Preservation: Snap-freeze fresh tissue in liquid nitrogen and section (5-20 µm thickness) using a cryostat. Mount sections on conductive indium tin oxide (ITO) glass slides [40].

- Matrix Application: Apply a homogeneous layer of matrix (e.g., 4-(dimethylamino)cinnamic acid, DMACA) via automated spray coating or sublimation. Sublimation is preferred for high spatial resolution as it minimizes analyte delocalization [40] [43].

- MS Acquisition:

- Instrument: MALDI-time-of-flight (TOF) or MALDI-timsTOF systems.

- Spatial Resolution: Set the raster width to the desired pixel size (typically 5-50 µm for cellular resolution, down to 1 µm for subcellular features) [40] [43].

- Mass Resolution: Acquire data in high-resolution mode to confidently assign lipid masses.

- Data Analysis: Use specialized software to generate ion images based on the intensity of specific m/z values, correlating lipid signatures with tissue histology [40].

Innovation Note: A recent advanced sample preparation method involves pre-staining tissue sections with cresyl violet before matrix application. This method has been shown to enhance lipid signal intensities by an order of magnitude and enables simultaneous imaging of lipids and nucleotides at subcellular resolution (down to 1 µm pixel size) [43].

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) for Neutral Lipids

Principle: APCI is a gas-phase ionization technique. The sample solution is nebulized and vaporized in a heated chamber. A corona discharge needle creates primary ions from the solvent vapour, which then undergo ion-molecule reactions to protonate the analyte molecules ([M+H]âº) [37]. This technique is less susceptible to ion suppression from polar matrix components and is well-suited for less polar lipids.

Experimental Protocol: NPLC-APCI-MS for Global Lipid Class Analysis

- Sample Preparation: Use standard lipid extraction protocols (e.g., Bligh & Dyer).

- Chromatography:

- MS Acquisition:

- Ion Source: APCI in positive mode.

- Key Parameters: Optimize vaporizer temperature and corona current. A key feature of APCI is the generation of in-source fragment ions (e.g., [MG+H-H₂O]⺠for monoacylglycerols) that provide information on the distribution of esterified fatty acyls within a lipid family [41].

Application Insight: The NPLC-APCI-MS method is powerful for profiling up to 30 lipid classes in a single analysis. However, it may struggle with very polar lipids (e.g., LPC) at the end of the gradient and can cause excessive in-source fragmentation of certain classes like sterol esters, which is why the ESI-lithium method serves as a valuable complement [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics Ionization Workflows

| Item / Reagent | Function in Lipid Analysis |

|---|---|

| Lithium Chloride (LiCl) / Lithium Acetate | Cationizing agent for post-column adduct formation in ESI; stabilizes molecular ions and enhances sensitivity for neutral lipids [41]. |

| MALDI Matrix (e.g., DMACA) | Light-absorbing compound mixed with the sample to enable efficient desorption and ionization of lipids by laser irradiation [40] [43]. |

| MTBE (Methyl tert-butyl ether) | Organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction (e.g., MeOH/MTBE); provides high recovery (>85%) for diverse phospholipid classes [42]. |

| Deuterated Internal Standards (e.g., SPLASH Lipidomix) | Mixture of stable isotope-labeled lipids; essential for correcting for extraction efficiency, matrix effects, and instrumental variability during semi-quantification [42]. |

| Cresyl Violet | Pre-staining dye that, when applied before matrix deposition, dramatically improves lipid signal intensity and enables subcellular MSI [43]. |

| Isomorellinol | Isomorellinol, MF:C33H38O7, MW:546.6 g/mol |

| 3-O-Methyl-DL-DOPA | 3-Methoxytyrosine |

Lipidomics Workflow and Technique Selection Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for integrating these ionization techniques into a complete lipidomic workflow, from sample collection to data analysis.

Diagram Title: Lipidomics Workflow & Ionization Technique Selection

The selection of an ionization technique—ESI, MALDI, or APCI—is a fundamental decision that shapes the scope and success of a lipidomics study. ESI excels in sensitivity and compatibility with LC for comprehensive profiling, MALDI is unmatched for spatial mapping in tissues, and APCI provides robust analysis of neutral lipid classes. As demonstrated by innovative approaches like post-column lithium addition in ESI and pre-staining in MALDI-MSI, the ongoing refinement of these core techniques continues to deepen our ability to unravel the complexity of the lipidome. By understanding the principles, applications, and practical protocols outlined in this article, researchers can make informed choices to effectively address their specific biological questions.

Analytical Strategies and Advanced Applications in Lipidomics

Lipidomics, the comprehensive analysis of lipids in biological systems, has emerged as a crucial discipline for understanding cellular functions, signaling pathways, and disease mechanisms. As a branch of metabolomics, lipidomics provides unique insights into lipid metabolism and its dysregulation in various pathological conditions [44]. Mass spectrometry (MS) has become the cornerstone technology in lipidomics due to its high sensitivity and specificity, with two primary approaches dominating the field: shotgun lipidomics and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) based lipidomics [45]. These methodologies offer complementary advantages and limitations, making the choice between them critical for experimental success. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these platforms, along with practical protocols to assist researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate approach for their specific research questions in drug development and basic science.

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in sample introduction. Shotgun lipidomics involves the direct infusion of lipid extracts into the mass spectrometer without prior chromatographic separation, exploiting the unique chemical and physical properties of lipids for their identification and quantification [44] [45]. In contrast, LC-MS based lipidomics incorporates liquid chromatographic separation before mass spectrometric analysis, reducing complexity at the point of ionization and separation of isomeric species [46]. Both approaches have evolved significantly, with shotgun lipidomics expanding into multi-dimensional platforms and high-resolution systems, while LC-MS methodologies have advanced with techniques such as ion mobility spectrometry and electron-activated dissociation to enhance lipid coverage and confidence in identification [45] [46].

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Shotgun Lipidomics: Core Concepts and Platforms

Shotgun lipidomics operates on the principle of analyzing lipids directly from organic extracts of biological samples under constant concentration conditions during direct infusion [44]. This unique feature allows researchers to perform detailed tandem mass spectrometric analyses without time constraints typically encountered during chromatographic elution. The identification of lipid species relies on recognizing that most lipids represent linear combinations of fundamental building blocks, including glycerol, sphingoid bases, polar head groups, and fatty acyl substituents [44].

Three major platforms of shotgun lipidomics are currently in practice:

Profiling by Class-Specific Fragments: This approach uses characteristic fragments after collision-induced dissociation to determine individual molecular species through precursor-ion or neutral loss scanning. Internal standards are added during extraction to correct for experimental factors and enable accurate quantification [44].

Tandem MS with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometers: This methodology employs high mass accuracy/high mass resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., quadrupole-time-of-flight instruments) to acquire product ion spectra of each molecular ion. Identification occurs through bioinformatic reconstruction of fragments from precursor-ion or neutral loss scans, with quantification achieved by comparing fragment intensities to preselected internal standards [44].

Multidimensional Mass Spectrometry-Based Shotgun Lipidomics (MDMS-SL): This advanced platform creates two-dimensional mass spectrometric maps analogous to 2D NMR spectroscopy. The first dimension represents molecular ions, while the second dimension represents building blocks characteristic of lipid classes. This approach facilitates the identification of individual lipid molecular species, including the deconvolution of isomeric species, and employs a two-step quantification procedure to significantly increase dynamic range [44].

LC-MS Based Lipidomics: Separation Mechanisms and Advancements

LC-MS based lipidomics incorporates chromatographic separation prior to mass spectrometric analysis, primarily using two complementary separation mechanisms:

Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC): This method separates lipid species based on their hydrophobic properties, including acyl chain length, and degree of unsaturation [47]. RPLC provides excellent separation within lipid classes and is particularly powerful for resolving non-polar lipids and distinguishing structural isomers that differ in acyl chain composition [48].

Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC): This technique separates lipids according to polarity in a class-specific fashion through interaction of the polar head groups with the stationary phase [47]. The retention mechanism of HILIC is advantageous for quantification due to co-elution of endogenous lipid species and internal standards belonging to the same lipid subclass, enabling appropriate correction for matrix effects [47].

Recent advancements in LC-MS lipidomics have incorporated additional separation dimensions and fragmentation techniques. Ion mobility spectrometry separates lipid ions based on their collision cross section (CCS), a physical property reflecting conformational shape, providing an extra dimension for separating isobaric and isomeric species [48]. Polarity switching during single runs allows acquisition of both positive and negative ion mode data from the same injection, expanding lipid coverage [46]. Additionally, electron-activated dissociation (EAD) has emerged as a powerful fragmentation technique that provides more detailed structural information for confident lipid identification [46].

Table 1: Comparison of Chromatographic Separation Methods in LC-MS Lipidomics

| Method | Separation Mechanism | Key Applications | Quantification Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase (RPLC) | Hydrophobicity (acyl chain length & unsaturation) | Separation within lipid classes; non-polar lipids; structural isomers | Wide lipid coverage; high peak capacity |

| Hydrophilic Interaction (HILIC) | Polar head group interaction with stationary phase | Class-specific separation; polar lipids | Co-elution of lipid class with internal standards; reduced matrix effects |

| Ion Mobility | Collision cross section (CCS) in gas phase | Separation of isobaric/isomeric species; complex samples | Additional identification parameter (CCS value) |

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Technical Comparison of Key Parameters

Understanding the technical capabilities of each approach is essential for selecting the appropriate methodology for specific research questions. The following table provides a direct comparison of key performance parameters between shotgun and LC-MS based lipidomics:

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Shotgun vs. LC-MS Based Lipidomics

| Parameter | Shotgun Lipidomics | LC-MS Based Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Throughput | High (no separation step) | Moderate to Low (chromatographic runtime required) |

| Ion Suppression | Higher potential in complex samples | Reduced through chromatographic separation |

| Dynamic Range | Can be extended via MDMS-SL [44] | Naturally wider for low-abundance species |

| Identification of Isobaric/Isomeric Species | Limited in classical approach; improved with MDMS-SL [44] [45] | Superior with RPLC and ion mobility [45] [48] |

| Quantification Accuracy | High with appropriate internal standards [44] | High with co-eluting internal standards in HILIC [47] |

| Lipidome Coverage | Broad for major classes; may miss low-abundance species | Comprehensive, including low-abundance lipids |

| Method Development Complexity | Moderate (optimization of infusion & MS parameters) | High (optimization of chromatography & MS methods) |

| Data Complexity | High (requires advanced bioinformatics) | Very High (additional chromatographic dimension) |

| Instrument Cost | Moderate to High | High to Very High |

| Analysis of Complex Matrices | May require pre-fractionation | Better suited without extensive sample preparation |

Application-Based Selection Guidance

The optimal choice between shotgun and LC-MS lipidomics depends heavily on the specific research objectives, sample types, and analytical requirements:

Clinical and Large-Scale Studies: For high-throughput analysis of large sample cohorts (e.g., population studies, clinical trials), shotgun lipidomics offers significant advantages due to its rapid analysis time and robustness [47]. Similarly, HILIC-based LC-MS approaches provide an excellent compromise for high-throughput quantification when comprehensive lipid class profiling is required [47]. A recent large-scale clinical application demonstrated the robust measurement of 782 circulatory lipid species across 1,086 plasma samples with median between-batch reproducibility of 8.5% using a HILIC-based approach [47].

Single-Cell and Limited Sample Applications: When sample material is extremely limited, as in single-cell lipidomics, LC-MS approaches are particularly advantageous. Recent advances have demonstrated successful lipid profiling from single cells using nanoflow LC-MS systems, with platforms incorporating polarity switching, ion mobility spectrometry, and electron-activated dissociation significantly enhancing both lipidome coverage and confidence in lipid identification [46]. The chromatographic separation in LC-MS reduces matrix effects, which is crucial when analyzing minute sample amounts [46].

Structural Characterization and Isomer Separation: For studies requiring detailed structural information, including identification of double bond positions, acyl chain attachment sites, or separation of isomeric species, RPLC-MS and ion mobility-MS approaches are superior [48]. The combination of chromatographic retention time, collision cross section values, and fragmentation patterns provides multiple dimensions for confident structural annotation.

High-Throughput Screening: In drug discovery applications where rapid screening of lipid changes in response to compound libraries is needed, shotgun lipidomics provides the necessary throughput without compromising data quality, especially when combined with automated sample preparation and data processing workflows [44].

Experimental Protocols

Shotgun Lipidomics Protocol for Clinical Samples

This protocol is adapted from established shotgun lipidomics workflows for clinical samples such as tissue, blood plasma, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [49].

I. Sample Preparation

- Lipid Extraction: Use methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) protocol. Add 225 μL of methanol and 750 μL of MTBE to 50 μL of plasma sample.

- Internal Standard Addition: Add at least two molecular species of each lipid class of interest as internal standards during extraction. Select compounds that are absent or minimal in original extracts and faithfully represent physical properties of the examined lipid class [44].

- Vortex and Incubate: Vortex thoroughly for 1 hour at 4°C in a shaking incubator.

- Phase Separation: Add 188 μL of MS-grade water to induce phase separation. Centrifuge at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Collection: Collect the upper organic phase and evaporate under nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute dried lipids in 100 μL of chloroform:methanol (1:2, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium acetate for ESI-MS analysis.

II. Mass Spectrometric Analysis

- Direct Infusion: Use a syringe pump at flow rate of 5-10 μL/min.

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap, or FT-ICR) or triple quadrupole instrument.

- Acquisition Modes:

- Full Scan MS: Acquire in both positive and negative ion modes with mass resolution >100,000 for lipid profiling.

- Precursor Ion Scans: Perform class-specific scans (e.g., m/z 184.0733 for phosphocholine-containing lipids in positive mode).

- Neutral Loss Scans: Implement (e.g., neutral loss of 141.05 for phosphatidylethanolamines).

- Data-Dependent MS/MS: Acquire fragmentation spectra for structural elucidation.

- Quality Control: Analyze quality control samples (e.g., NIST SRM 1950 plasma) every 12 samples to monitor instrument performance [47].

III. Data Processing and Lipid Identification

- Peak Picking and Alignment: Use instrument software or open-source tools (e.g., MS-DIAL, LipidSearch).

- Lipid Identification: Identify based on accurate mass (mass error < 5 ppm), MS/MS spectra, and characteristic fragmentation patterns.

- Quantification: Calculate lipid concentrations as peak area ratio between analyte and structurally similar internal standard multiplied by its known spiked concentration [47].

- Isotopic Correction: Perform correction for isotopic overlap using tools like LICAR (Lipid Class-based Automatic Correction) [47].

LC-MS Based Lipidomics Protocol for Single Cells

This protocol demonstrates a nanoflow LC-MS method for single-cell lipidomics, as recently evaluated across multiple instrumental platforms [46].

I. Single Cell Isolation and Sample Preparation

- Cell Culture: Culture human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells PANC-1 in appropriate medium. Wash twice with warm FBS-free culture medium before sampling.

- Capillary Sampling: Use Yokogawa SS2000 Single Cellome System with 10 μm capillaries. Apply pressures: pre-sampling 6 kPa, sampling 14 kPa, post-sampling 3 kPa. Hold cells for 200 ms.

- Cell Lysis: Immediately freeze capillary tips on dry ice after sampling. Transfer cells to LC-MS vials by backfilling capillaries with 5 μL lysis solvent (IPA/H₂O/ACN, 51:62:87 v/v/v) spiked with EquiSPLASH internal standard mixture (16 ng/mL).

- Sample Preparation: For nanoflow workflows, freeze-dry samples under low vacuum (0.5 mbar) and store under nitrogen at -80°C until analysis.

II. LC-MS Analysis

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Column: Use C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 75 μm × 150 mm, 1.7 μm particles).

- Mobile Phase: A: acetonitrile:water (60:40) with 10 mM ammonium formate; B: isopropanol:acetonitrile (90:10) with 10 mM ammonium formate.

- Gradient: 0-2 min, 30% B; 2-20 min, 30-100% B; 20-25 min, 100% B; 25-25.1 min, 100-30% B; 25.1-35 min, 30% B.

- Flow Rate: 300 nL/min.

- Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Instrument: Orbitrap Exploris 240 or similar high-sensitivity instrument.

- Ionization: Nano-electrospray ionization at 2.2 kV.

- Acquisition: Full scan MS at resolution 60,000 (m/z 250-1250) with data-dependent MS/MS at resolution 15,000.

- Fragmentation: Higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) at 35 V.

- Polarity Switching: Acquire both positive and negative modes in single run by switching every 10 scans [46].

III. Data Processing

- Feature Detection: Use software such as Compound Discoverer or XCMS for peak picking and alignment.

- Lipid Identification: Match accurate mass (mass error < 5 ppm), MS/MS spectra against databases (e.g., LipidBlast, HMDB), and retention time when available.