Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI): A Comprehensive Guide to Binding Kinetics for Drug Development

This article provides a thorough exploration of Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI), a powerful, label-free optical biosensing technology for real-time biomolecular interaction analysis.

Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI): A Comprehensive Guide to Binding Kinetics for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI), a powerful, label-free optical biosensing technology for real-time biomolecular interaction analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles and kinetic theory to advanced methodological protocols for diverse applications, including membrane protein, protein-liposome, and ribosome-protein interactions. It offers practical troubleshooting guidance, compares BLI with complementary technologies like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), and validates its role in high-throughput screening and kinetic characterization. The synthesis of current research and best practices aims to equip the target audience with the knowledge to effectively implement BLI in their workflows, from basic research to therapeutic optimization.

Understanding Bio-Layer Interferometry: Core Principles and Kinetic Fundamentals

Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) is a powerful label-free optical biosensing technology that enables real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions. By measuring shifts in white light interference patterns, BLI provides researchers with precise tools for determining binding kinetics and affinities, which are crucial parameters in drug discovery and basic research. This application note details the fundamental optical principles underlying BLI technology, presents standardized protocols for kinetic analysis, and provides practical guidance for implementation across various molecular interaction studies. The technology's unique "dip-and-read" format eliminates the need for microfluidics while providing high-throughput capabilities, making it particularly valuable for antibody characterization, protein-protein interaction studies, and small molecule analysis [1] [2].

Bio-Layer Interferometry represents a significant advancement in label-free biosensing technology that has transformed how researchers study molecular interactions. Unlike traditional methods that require fluorescent or radioactive labeling, BLI enables direct, real-time monitoring of binding events without modifying the interacting molecules. This capability preserves native binding characteristics and provides more physiologically relevant data. The technology has gained widespread adoption in pharmaceutical development, academic research, and bioprocessing due to its robust methodology and relatively simple operational requirements compared to other label-free techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [2] [3].

BLI operates on the fundamental principle of white light interferometry, where changes in the optical thickness at the biosensor tip correlate directly with molecular binding events. This physical relationship allows researchers to quantify interaction kinetics—including association rates (kon), dissociation rates (koff), and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD)—with high precision and accuracy. The technology's flexibility supports diverse applications ranging from antibody screening and epitope binning to DNA-protein interaction analysis and small molecule characterization [4] [5] [6].

A key advantage of BLI in modern research contexts is its compatibility with high-throughput screening approaches. The ability to simultaneously analyze up to 96 samples in parallel addresses the growing need for rapid characterization of large molecular libraries generated through computational design, phage display, and other discovery platforms. Furthermore, as artificial intelligence-driven protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold become more prevalent, BLI provides essential empirical validation for computationally derived models, creating a powerful synergy between in silico and wet-lab approaches [4].

The Optical Physics of White Light Interference

Fundamental Interference Phenomenon

At its core, BLI exploits the wave nature of light through the physical principle of thin-film interference. When white light from a tungsten lamp illuminates the biosensor tip, it reflects from two distinct surfaces: the internal reference layer (a stationary mirror) and the external biosensor surface where molecular binding occurs. These two reflected light beams travel different path lengths before recombining, creating an interference pattern that depends on their relative phase relationship [1] [2].

The interference pattern manifests as a spectrum of constructive and destructive interference across different wavelengths. Constructive interference occurs when the path difference equals integer multiples of the wavelength, amplifying specific colors, while destructive interference happens with half-integer multiples, diminishing those colors. The resulting pattern is highly sensitive to minute changes in the optical path length between the two reflecting surfaces—changes as small as picometers can be detected, enabling the technology to monitor molecular binding events in real time [7].

From Interference Patterns to Binding Data

In BLI, the biosensor tip constitutes a Fabry-Pérot interferometer where the biological layer forms the resonant cavity. As molecules bind to the biosensor surface, the optical thickness of this cavity increases, altering the path difference between the two reflected light beams. This change shifts the interference pattern toward longer wavelengths, which the instrument detects and records as a response signal in nanometers [4].

The relationship between interference pattern shift and molecular binding is direct and quantitative. A positive wavelength shift indicates an increase in biolayer thickness due to molecular association, while a negative wavelength shift corresponds to decreased thickness from molecular dissociation. This real-time monitoring capability provides a continuous measurement of binding progression without requiring separation or washing steps that might disturb equilibrium conditions [2].

Table 1: Key Optical Parameters in BLI Systems

| Parameter | Typical Specification | Significance in Molecular Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Broadband tungsten lamp (≈400-750 nm) | Provides multiple wavelengths for interference pattern generation |

| Detection Method | Spectrometer analyzing wavelength shift | Measures interference pattern changes with sub-nanometer resolution |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited by sensor tip diameter (≈1 mm) | Defines measurement area and total molecule capacity |

| Thickness Sensitivity | Picometer scale | Enables detection of small molecule binding events |

| Temporal Resolution | 0.1-10 seconds per data point | Determines ability to resolve rapid binding kinetics |

The exceptional sensitivity of BLI stems from the coherence properties of white light sources. Unlike laser interferometry, white light interferometry exploits the short coherence length of broadband sources (typically a few micrometers) to precisely define the measurement zone immediately adjacent to the biosensor surface. This inherent property eliminates interference from distant surfaces or non-specifically bound molecules in solution, providing exceptional signal-to-noise ratio for specific binding events [7].

BLI Experimental Workflow

The standard BLI experiment follows a consistent workflow that can be divided into distinct phases, each critical for obtaining reliable kinetic data.

Biosensor Preparation and Molecule Immobilization

The process begins with selection of an appropriate biosensor, which consists of a fiber optic tip functionalized with specific chemistry to capture the molecule of interest (ligand). Common surfaces include streptavidin for biotinylated molecules, anti-His tags for His-tagged proteins, or Protein A for antibody Fc regions. The biosensor is hydrated and baseline signal established by incubating in buffer, then the ligand is immobilized through dipping into the ligand solution, creating the reactive surface [1] [6].

Association and Dissociation Measurement

Once prepared, the biosensor is transferred to a solution containing the binding partner (analyte), initiating the association phase. During this period, molecules bind to the immobilized ligand, increasing optical thickness and generating a positive signal shift. After sufficient association monitoring, the biosensor is moved to a buffer-only solution to measure dissociation, where bound molecules release from the ligand, causing a negative signal shift back toward baseline [1] [2].

Data Processing and Kinetic Analysis

The raw interference data undergoes processing to extract kinetic parameters. Baseline signals are normalized, and reference sensor data (exposed to buffer only) is subtracted to control for non-specific binding and buffer effects. The resulting binding curve is fitted to appropriate interaction models (most commonly 1:1 binding) using non-linear regression analysis to calculate the association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = koff/kon) [4] [6].

Comparative Instrumentation and Technical Specifications

BLI platforms are available in various configurations tailored to different throughput and sensitivity requirements. The table below summarizes key systems and their capabilities:

Table 2: Comparison of Commercial BLI Instruments

| Instrument Model | Throughput (Channels) | Sample Volume | Key Applications | Sensitivity Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octet RH96 | 96 simultaneous | 5-20 µL | High-throughput screening, clone selection | Macromolecules to small molecules >150 Da |

| Octet R8/R8e | 8 simultaneous | 50-200 µL | Detailed kinetic analysis, antibody characterization | Small molecule sensitivity (150 Da) |

| Octet RH16 | 16 simultaneous | 50-200 µL | Balanced throughput and sensitivity | Optimized for protein interactions |

| BLItz/Octet N1 | Single channel | 4-10 µL | Quick assays, limited sample availability | Proteins >10 kDa |

Instrument selection depends on specific research needs. The Octet RH96 provides unparalleled throughput for screening applications, while the Octet R8 series offers enhanced sensitivity for detailed kinetic analysis of challenging interactions like small molecule binding. The single-channel BLItz system is ideal for low-volume applications or educational settings where cost considerations are paramount [1] [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful BLI experiments require appropriate selection of biosensors and supporting reagents. The table below outlines key components:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BLI Experiments

| Reagent/Biosensor | Composition/Type | Function in BLI Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Streptavidin (SA) Biosensors | Streptavidin immobilized on tip surface | Captures biotinylated ligands (proteins, DNA, antibodies) |

| Anti-His (HIS1K) Biosensors | Anti-histidine antibody functionalized | Binds His-tagged recombinant proteins |

| Ni-NTA (NTA) Biosensors | Nickel chelate chemistry | Immobilizes His-tagged proteins through metal affinity |

| Anti-Human IgG Fc Biosensors | Protein A or anti-Fc antibody | Captures human antibodies without purification |

| Super-Streptavidin (SSA) Biosensors | High-density streptavidin | Enhanced sensitivity for small molecule analysis |

| Association Buffer | Compatible aqueous buffer | Maintains analyte activity during binding phase |

| Regeneration Solutions | Low pH buffer or specific eluents | Removes bound analyte for sensor reuse |

Biosensor selection is critical for experimental success and depends on the molecular system under investigation. Streptavidin sensors provide exceptional versatility for biotinylated ligands, while Anti-His sensors are ideal for recombinant protein studies. For antibody characterization, Protein A or Fc-specific sensors offer direct capture from crude supernatants without purification [1] [6].

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Protein-Protein Interaction Kinetics

This protocol describes the determination of binding kinetics between two proteins, such as an antibody-antigen pair, using BLI. The procedure requires approximately 3 hours and is suitable for researchers with minimal BLI experience [4].

Materials Required:

- BLI instrument (Octet R4, R8, or equivalent)

- Appropriate biosensors (e.g., Anti-Human IgG Fc for antibodies)

- Black 96-well microplate (flat-bottom, polypropylene)

- Assay buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.1% BSA)

- Purified ligand and analyte proteins

- Pipettes and tips for liquid handling

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the BLI system and computer. Open the data acquisition software and initialize the instrument. Allow the system to stabilize for 15 minutes.

- Experimental Plate Setup: Hydrate biosensors in buffer for at least 10 minutes. Prepare a 96-well plate with columns arranged as follows:

- Column 1: 200 µL assay buffer (baseline)

- Column 2: 150-200 µL ligand solution (10-50 µg/mL in buffer)

- Column 3: 200 µL assay buffer (second baseline)

- Columns 4-11: Two-fold serial dilutions of analyte (50-200 µL per well)

- Column 12: 200 µL regeneration solution (if reusing sensors)

- Baseline Acquisition (300 seconds): Dip biosensors into Column 1 (buffer) to establish a stable baseline signal. This step ensures consistent starting conditions.

- Ligand Loading (500 seconds): Transfer biosensors to Column 2 (ligand solution) to immobilize the ligand on the sensor surface. Monitor until adequate loading is achieved (typically 1-5 nm wavelength shift).

- Second Baseline (300 seconds): Return biosensors to buffer (Column 3) to wash away unbound ligand and stabilize signal before analyte exposure.

- Association Phase (600 seconds): Move biosensors to analyte solutions (Columns 4-11) to monitor binding. Use a range of concentrations (e.g., from nM to µM) for robust kinetic analysis.

- Dissociation Phase (900-1800 seconds): Transfer biosensors back to buffer (Column 1 or fresh buffer) to monitor complex dissociation. Longer dissociation times improve accuracy for high-affinity interactions.

- Sensor Regeneration (Optional): For reusable sensors, dip into regeneration solution (Column 12) for 5-15 seconds to remove bound analyte, then re-equilibrate in buffer.

Data Analysis:

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract signals from buffer-only reference sensors to correct for non-specific binding and buffer effects.

- Alignment: Align dissociation phases to the start of buffer immersion and adjust baselines to zero.

- Curve Fitting: Fit processed data to a 1:1 binding model using the instrument software or external tools like GraphPad Prism to determine kon, koff, and KD values.

Protocol for DNA-Protein Interaction Analysis

This protocol adapts BLI methodology for studying DNA-protein interactions, which are fundamental to transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and replication processes [5].

Specialized Materials:

- Streptavidin (SA) biosensors

- Biotinylated double-stranded DNA probes (50-100 bp)

- DNA-binding protein of interest

- DNA binding buffer (typically Tris or HEPES with salts, Mg2+, DTT)

Procedure:

- DNA Probe Design: Design complementary oligonucleotides containing target sequence and 5' biotin modification on one strand. Anneal equimolar strands to form double-stranded probes.

- Probe Immobilization (600 seconds): Hydrate SA biosensors, then dip into solution containing biotinylated DNA probes (5-50 nM in binding buffer) to capture DNA on sensor surface.

- Baseline Equilibration (300 seconds): Transfer sensors to binding buffer to establish stable baseline.

- Association Phase (600 seconds): Move sensors to wells containing serial dilutions of DNA-binding protein to monitor complex formation.

- Dissociation Phase (1200 seconds): Transfer sensors to binding buffer to monitor protein dissociation from DNA.

- Data Processing: Analyze data as described in Protocol 6.1, using steady-state analysis for low-affinity interactions that may not reach equilibrium during association.

Technical Considerations:

- Include scrambled-sequence DNA controls to verify binding specificity

- Optimize salt concentration in binding buffer to mimic physiological conditions

- For transcription factors with cooperative binding, consider more complex binding models

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

Epitope Binning and Competition Assays

BLI enables efficient epitope binning for monoclonal antibody characterization, determining whether different antibodies bind identical, overlapping, or distinct epitopes on a target antigen. The methodology involves sequential antibody binding, where a first antibody is immobilized on the biosensor, antigen is bound, then a second antibody is tested for binding to the antigen-antibody complex. Lack of second antibody binding indicates competing antibodies that share an epitope, while successful binding indicates non-competing antibodies that can bind simultaneously [4].

Small Molecule Interaction Analysis

Measuring small molecule binding presents unique challenges due to minimal mass change upon binding. BLI addresses this through Super Streptavidin (SSA) biosensors with enhanced sensitivity and careful experimental design. Small molecule analytes typically require higher concentrations (μM to mM range) and longer averaging times to detect binding signals above noise. Competition formats, where small molecules compete with larger reference binders, often provide more robust data than direct binding approaches [1] [6].

Crude Sample Analysis

A distinctive BLI advantage is direct analysis of unpurified samples, including cell culture supernatants, lysates, and hybridoma media. This capability streamlines antibody screening and cell line development by eliminating purification steps. When working with crude samples, include additional controls for matrix effects and non-specific binding, using reference sensors with irrelevant capture molecules to establish background signals [6].

Troubleshooting and Data Quality Assessment

Successful BLI implementation requires awareness of potential technical challenges and their solutions:

Common Issues and Solutions:

- Non-specific Binding: Add carrier proteins (BSA, casein) to assay buffer, reduce sample complexity, or optimize pH/salt conditions

- Signal Drift: Ensure temperature equilibrium, degas buffers, and extend baseline acquisition

- Incomplete Dissociation: Optimize regeneration conditions (pH, additives) or use disposable sensors

- Low Signal-to-Noise: Increase ligand density, extend measurement times, or use higher-sensitivity biosensors

Data Quality Metrics:

- Binding Curves: Should show smooth, monophasic association and dissociation

- Chi² Values: <10% of maximum response indicates good model fit

- Parameter Standard Error: <20% of value suggests reliable determination

- Concentration Gradient: Responses should increase systematically with analyte concentration

BLI technology provides researchers with a powerful platform for characterizing molecular interactions through the elegant application of white light interferometry. Its label-free nature, real-time monitoring capability, and compatibility with diverse sample types make it particularly valuable for drug discovery, antibody engineering, and basic research applications. As molecular interaction analysis continues to evolve toward higher throughput and greater sensitivity, BLI methodologies offer robust solutions that bridge computational prediction and empirical validation, accelerating the pace of biomedical discovery.

In the realm of molecular interaction analysis, sensorgrams serve as the primary data output for label-free techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI). These real-time graphical representations provide a dynamic view of binding events, enabling researchers to quantify interaction kinetics and affinity. A sensorgram plots the change in an optical signal (e.g., resonance units or wavelength shift) against time, directly reflecting the binding status between an immobilized ligand and an analyte in solution [8] [9]. For researchers employing bio-layer interferometry, mastering the interpretation of each phase within a sensorgram is fundamental to extracting accurate kinetic parameters, which in turn informs critical decisions in drug discovery, antibody characterization, and proteomics research.

The underlying principle for BLI involves a fiber optic biosensor that generates an interference pattern from light reflected at two surfaces: an internal reference layer and the external biosensor tip where biomolecular binding occurs [10] [11]. As molecules bind to the tip, the optical path length shifts, altering the interference pattern. This shift, measured in real-time, produces the sensorgram, which is proportional to the mass of bound analyte [12] [13]. Unlike other methods, BLI is notably less affected by changes in the refractive index of the bulk solution, making it particularly robust for assays involving complex buffers or allosteric effectors [11].

The Core Phases of a Sensorgram

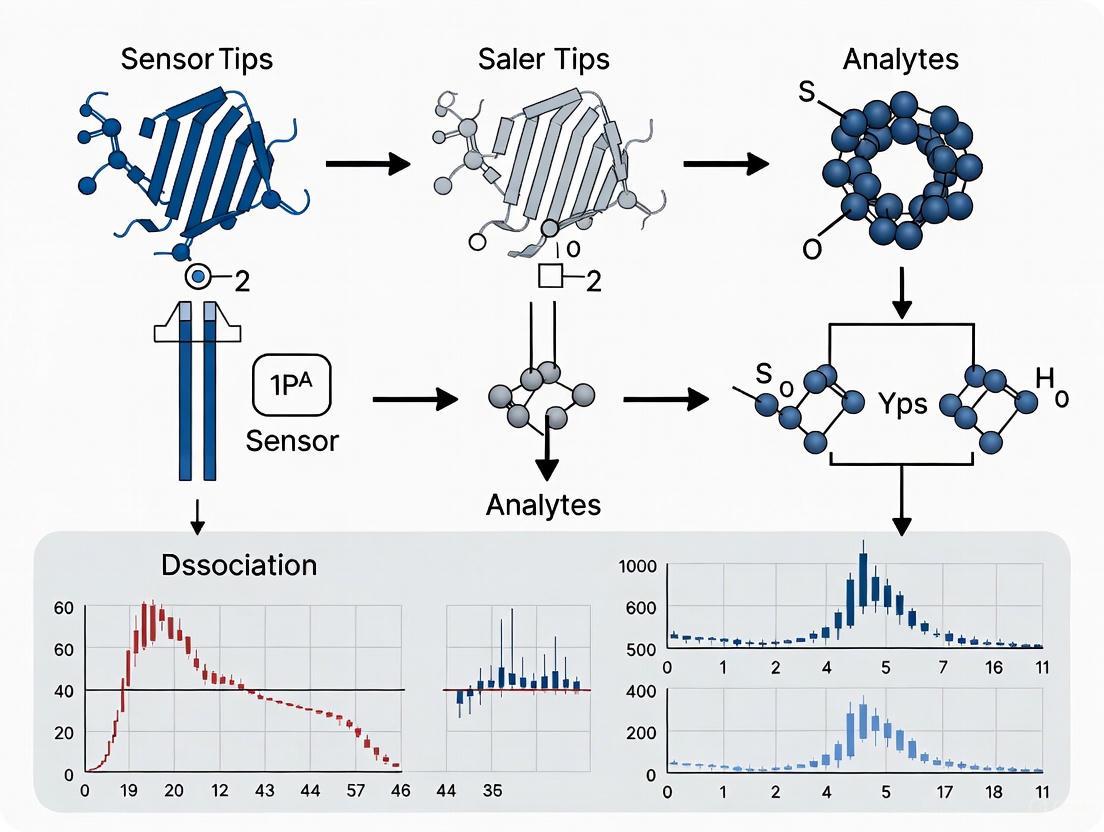

A standard sensorgram is composed of five distinct phases, each revealing specific aspects of the molecular interaction: Baseline, Association, Steady-State, Dissociation, and Regeneration [9]. The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of a BLI experiment and how each step corresponds to a segment of the resulting sensorgram.

Baseline Phase: Establishing Stability

The baseline phase represents the starting point of the experiment, where the sensor, conditioned in the running buffer, establishes a stable optical signal [8] [9]. A flat, straight line indicates a stable system, which is crucial for accurate subsequent measurements [8]. This phase is used to check for system anomalies or instability. Baseline drift, often caused by contaminants in the buffer, residual analytes on the sensor surface, or temperature fluctuations, can significantly compromise data quality [8]. Before proceeding to the loading or association steps, it is critical to achieve a stable baseline, as any drift, injection spikes, or high buffer response is an indication that the system should be inspected and cleaned [9].

Association Phase: Capturing Binding Events

The association phase begins at the moment of analyte injection. As analyte molecules in solution bind to the immobilized ligand on the sensor surface, the mass at the tip increases, resulting in a sharp rise in the SPR or BLI signal [8] [14]. This phase ideally forms a single exponential curve, the shape of which is governed by the association rate constant (kâ‚ or k_ON) and the analyte concentration [8] [9]. A steeper curve indicates faster binding. The binding process during this phase is controlled by two key events: the mass transfer of the analyte from the bulk solution to the surface, and the subsequent binding event to the surface-fixed ligand [8]. If the movement of the analyte from the bulk solution to the surface is slower than the actual binding kinetics (a phenomenon known as mass transfer limitation), the correlation curve will appear more linear [8].

Steady-State Phase: Reaching Equilibrium

Following the association phase, the sensorgram may reach a steady-state or equilibrium phase. This is represented by a top flat portion of the sensorgram where the net rate of bound analytes is zero, meaning the rate of analyte association equals the rate of dissociation [9]. At this plateau, the response level is directly related to the concentration of the analyte and the binding affinity. The steady-state phase is critical for determining the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) by plotting the response at equilibrium (Req) against a range of analyte concentrations [15].

Dissociation Phase: Monitoring Complex Decay

The dissociation phase is initiated when the analyte solution is replaced by a wash buffer. This removal of free analyte allows the bound complexes to dissociate, leading to a decrease in the signal as analyte molecules unbind from the ligand [8] [14]. The dissociation phase is represented by a downward-sloping curve, which ideally follows a single exponential decay [8]. The slope of this curve provides the dissociation rate constant (kd or kOFF) [9]. The rate of dissociation offers direct insight into the stability of the complex; a slower dissociation indicates a more stable complex, which for a therapeutic antibody, for example, could translate to a longer residence time and potentially improved efficacy [16].

Regeneration Phase: Resetting the Sensor

The final phase, regeneration, involves flowing a specific solution (often low pH, like glycine, or high salt) over the sensor surface to disrupt the ligand-analyte interaction completely [8] [9]. The goal is to remove all bound analyte and return the signal to the original baseline without damaging the functionality of the immobilized ligand [8]. This step is essential for reusing the sensor surface for the next analysis cycle, making the experimental process more efficient and cost-effective. It is important to establish a steady baseline signal after regeneration to indicate that the sensor system is free of bound analytes and non-specifically adsorbed molecules, and has stability for the next measurement [9].

Quantitative Analysis of Sensorgram Data

The ultimate goal of sensorgram analysis is to extract quantitative kinetic and affinity parameters that describe the molecular interaction. This is achieved by fitting the data from the association and dissociation phases to appropriate binding models.

Key Kinetic and Affinity Parameters

The following table summarizes the core parameters obtained from sensorgram analysis.

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Typical Units | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate Constant | kâ‚ (k_ON) | Measures how quickly the analyte binds to the ligand. | Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ | A higher value indicates faster binding. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | kd (kOFF) | Measures how quickly the analyte unbinds from the ligand. | sâ»Â¹ | A lower value indicates a more stable complex. |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant | K_D | KD = kd / kâ‚. Represents the binding affinity. | M | A lower K_D indicates higher affinity (tighter binding). |

| Maximal Response | R_max | Theoretical maximum signal when all ligand sites are occupied. | RU or nm | Used for curve fitting and stoichiometry assessment. |

Binding Models and Curve Fitting

To determine the kinetic constants (kâ‚ and k_d), the sensorgram data must be fitted to a kinetic model using a mathematical algorithm [15]. The most commonly used model is the Langmuir binding model, which describes a simple 1:1 interaction where one ligand molecule interacts with one analyte molecule, assuming that all binding sites are equivalent and independent [15]. The graph below visualizes the process of extracting these parameters through data fitting.

In practice, the Langmuir model is often the first choice. However, more complex interactions may require advanced models such as Heterogeneous Ligand (for surfaces with more than one type of binding site) or Langmuir with Mass Transport (if analyte diffusion to the surface is rate-limiting) [15]. The quality of the fit is often judged by the χ² (Chi-squared) value and the randomness of the residual plots [15].

Essential Reagents and Materials for BLI Experiments

Successful execution of a BLI kinetics experiment requires careful preparation and the use of specific reagents. The table below lists key research reagent solutions and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensors | Solid support for immobilizing the ligand. | Streptavidin (SA), Anti-His (AHQ), Ni-NTA (NTA) sensors. Choice depends on ligand tag [11] [13]. |

| Running Buffer | Stable background matrix for all assay steps. | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), HEPES-NaCl. Must be optimized for pH and ionic strength [9] [17]. |

| Ligand | The molecule immobilized on the sensor surface. | Usually biotinylated or His-tagged protein. Purity and activity are critical. |

| Analyte | The binding partner free in solution. | Tested across a dilution series (e.g., 5-8 concentrations) for reliable kinetics [16]. |

| Regeneration Buffer | Removes bound analyte to reset the sensor surface. | Low pH glycine (e.g., 10 mM, pH 2.0) or high salt (e.g., 2 M NaCl). Condition must be optimized for each interaction [8] [17]. |

Detailed BLI Experimental Protocol

Pre-experiment Preparation and Instrument Setup

- Biosensor Hydration: Hydrate the required biosensors (e.g., Streptavidin) in running buffer for at least 10 minutes before the experiment [11].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the biotinylated or His-tagged ligand and the analyte samples into the running buffer. A typical experiment involves a dilution series of the analyte (e.g., 3-fold serial dilutions across 6-8 concentrations) to span a range from below to above the expected K_D [16].

- Instrument Programming: Using the instrument software (e.g., Octet), define a new kinetics experiment. Program the following steps in the assay definition [11] [13]:

- Initial Baseline: 60 seconds in running buffer.

- Loading: Immobilize the ligand to a predetermined threshold level.

- Secondary Baseline: 300-600 seconds in running buffer to establish a stable baseline post-loading.

- Association: 300-600 seconds with the analyte.

- Dissociation: 300-1800 seconds in running buffer.

Step-by-Step Execution and Data Collection

- Baseline Acquisition: Load the sample plate and biosensor tray into the instrument. Begin the experiment to establish the initial baseline, confirming system stability [11].

- Ligand Immobilization: The instrument moves the sensors to the wells containing the ligand solution. The loading step continues until the desired level of ligand is captured on the biosensor surface [13].

- Baseline Stabilization: Sensors are moved back to running buffer to wash away unbound ligand and stabilize the signal, establishing a new baseline for the binding experiment.

- Association Phase: Sensors are dipped into the wells containing the analyte dilution series. The binding response is recorded in real-time for each concentration.

- Dissociation Phase: Sensors are moved to wells containing running buffer only, and the decay of the signal is monitored as the complex dissociates.

- Regeneration (If applicable): For reusable sensors, a regeneration solution is applied to strip the bound analyte. A final baseline check ensures the surface is ready for another cycle.

Data Analysis and Quality Control

- Data Processing: Use the instrument's analysis software to process the raw data. Subtract signals from a reference sensor (loaded with a non-interacting ligand or left blank) to correct for non-specific binding and buffer effects [15].

- Curve Fitting: Select the processed sensorgrams for all analyte concentrations and fit them globally to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. The software will simultaneously fit the association and dissociation data across all curves to calculate kâ‚, kd, and KD [15].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate the goodness-of-fit by examining the χ² value and the residuals. The fitted curve should closely overlap the experimental data, and residuals should be randomly distributed around zero [15].

Troubleshooting Common Sensorgram Issues

Even with careful planning, experimental artifacts can occur. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Issue | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Drift | Buffer contamination, air bubbles, temperature fluctuations, or deteriorating sensor surface [8]. | Clean the fluid system, prepare fresh buffer, degas buffers, ensure proper sample preparation without aggregates [8]. |

| Low Binding Signal | Low analyte concentration, insufficient ligand immobilization, low affinity interaction, or suboptimal buffer conditions [8]. | Increase analyte concentration, optimize ligand immobilization to increase density, verify ligand activity, and adjust buffer pH or composition [8]. |

| Non-Specific Binding | Hydrophobic or charged sensor surfaces attracting analyte non-specifically, or impurities in the analyte solution [8]. | Use appropriate control sensors, improve sample purity, include a blocking step after ligand immobilization, and adjust buffer ionic strength or add a mild detergent [8]. |

| Irregular Curve Shape | Mass transport limitations, heterogeneous ligand surface, or analyte aggregation [8] [15]. | Increase flow rate (in flow-based systems) or agitation; use a different immobilization chemistry for a more uniform surface; filter or centrifuge analyte to remove aggregates. |

The quantitative analysis of biomolecular interactions is fundamental to advancing our understanding of biological processes and accelerating therapeutic development. The binding event between a ligand and an analyte is comprehensively described by three key kinetic parameters: the association rate constant (kon or ka), the dissociation rate constant (koff or kd), and the equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D). These parameters provide critical insight into the kinetics, stability, and overall affinity of an interaction, going beyond what is possible with simple endpoint assays. Among the technologies available for such characterization, bio-layer interferometry (BLI) has emerged as a powerful, label-free technique that enables real-time measurement of these kinetic parameters. This application note details the theoretical foundation of these constants and provides a robust experimental protocol for their determination using BLI, framed within the context of drug development and basic research.

Theoretical Foundations of Binding Kinetics

The Kinetic Parameter Triad

The interaction between a ligand (L) immobilized on a biosensor and an analyte (A) in solution can be represented by the simple binding model: L + A <==> LA. This reversible reaction is governed by two kinetic rates and one equilibrium constant.

- Association Rate Constant (kon or ka): This parameter describes the rate at which the ligand and analyte form a complex. It is influenced by factors such as molecular diffusion, electrostatic steering, and the structural complementarity between the binding partners. A higher k_on value typically indicates a faster formation of the complex.

- Dissociation Rate Constant (koff or kd): This parameter describes the rate at which the pre-formed complex breaks apart, reverting to the free ligand and analyte. It is a direct measure of the complex's stability; a lower k_off value indicates a more stable complex with a longer half-life.

- Equilibrium Dissociation Constant (KD): This parameter represents the analyte concentration at which half of the ligand binding sites are occupied at equilibrium. It is a ratio of the dissociation and association rates (KD = koff / kon) and is the most commonly cited measure of binding affinity. A lower K_D value indicates a higher affinity interaction.

The following table summarizes these core parameters and their significance.

Table 1: Fundamental Kinetic and Affinity Parameters in Biomolecular Interaction Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol(s) | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate Constant | kon, ka | Rate of complex formation (Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) | A higher value indicates faster binding. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | koff, kd | Rate of complex breakdown (sâ»Â¹) | A lower value indicates a more stable complex. |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant | K_D | Ratio koff / kon (M) | A lower value indicates higher binding affinity. |

| Half Maximal Effective Concentration | ECâ‚…â‚€ / ICâ‚…â‚€ | Concentration for 50% effect (M) | Potency of an effector (enhancing/inhibiting). |

The Critical Role of Effector Molecules

Many biological interactions are modulated by small molecules or metabolites, making the characterization of these effectors essential for understanding regulatory mechanisms [18]. The Half Maximal Effective Concentration (EC₅₀), or IC₅₀ for inhibitory effectors, quantifies the potency of such a molecule. It is defined as the concentration required to elicit a half-maximal response—for instance, to enhance or disrupt a protein-protein interaction by 50% [18] [13]. Determining the EC₅₀/IC₅₀ provides deep insight into allosteric regulation and is crucial for drug discovery, where a small molecule may act as an agonist or antagonist.

Bio-Layer Interferometry: A Primer

BLI is an optical analytical technique that measures the interference pattern of white light reflected from two surfaces: an internal reference layer and a biosensor tip surface where a biological layer is immobilized [18] [2]. A shift in the interference pattern wavelength (Δλ) is directly proportional to the change in thickness of the biological layer on the tip, enabling real-time, label-free monitoring of molecular binding and dissociation [2].

A key operational advantage of BLI is its "dip-and-read" format, where biosensor tips are transported to samples in open microplate wells, eliminating the need for microfluidic systems and reducing maintenance and clogging issues common in other technologies like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [18] [2] [19]. This makes BLI particularly suitable for high-throughput kinetic screening and analysis of samples in complex matrices, including crude supernatants [18] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow and the resulting data generated by a BLI assay.

BLI Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

A successful BLI experiment requires specific reagents and equipment. The table below lists the core components as used in a protocol for studying a His-tagged protein complex and its metabolite effector [18].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for a BLI Kinetic Assay

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| BLI Instrument | Platform for performing the assay and collecting real-time data. | FortéBio Octet K2 System [18] |

| Biosensors | Disposable fiber-optic tips that immobilize the ligand. | Ni-NTA (NTA) Dip and Read Biosensors for His-tagged proteins [18] [1] |

| Ligand | The molecule immobilized on the biosensor. | Purified 6xHis-tagged bait protein (e.g., PII signaling protein), 5-25 µg/ml [18] |

| Analyte | The molecule in solution that binds to the ligand. | Purified prey protein (e.g., PirC protein); molar concentration should be at least 5x that of the ligand [18] |

| Kinetics Buffer | The solution matrix for baseline, association, and dissociation steps. | Typically contains HEPES, salts (e.g., KCl, MgClâ‚‚), and sometimes detergent (e.g., Nonident-P40) [18] |

| Regeneration Solution | Used to remove bound analyte and ligand from the sensor for potential reuse. | 10 mM Glycine, pH 1.7 [18] |

| Microplate | Holds buffer, samples, and reagents for the "dip-and-read" process. | Black, 96-well, non-binding surface plates (e.g., Greiner Bio-One) [1] |

| Oxamicetin | Oxamicetin, CAS:52665-75-5, MF:C29H42N6O10, MW:634.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KF 13218 | KF 13218, CAS:127654-03-9, MF:C20H20N2O3, MW:336.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Determining K_D and ECâ‚…â‚€

This protocol is adapted from a published method for analyzing the interaction between a His-tagged PII protein and its binding partner PirC, and for determining the ECâ‚…â‚€ of the metabolite 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG) [18] [13].

Pre-experiment Preparation

- Reconstitute Reagents: Prepare the kinetics buffer, regeneration solution (10 mM glycine, pH 1.7), and 10 mM NiClâ‚‚ solution. thaw all proteins and effectors on ice.

- Instrument Setup: Power on the Octet system and pre-warm the sample compartment to the desired temperature (e.g., 30°C) for at least 30 minutes.

- Plate Preparation: Hydrate a black 96-well non-binding microplate by adding 200 µL of kinetics buffer to all wells that will be used. Then, prepare the working plate as follows:

- Column 1 (Baseline): Kinetics buffer.

- Column 2 (Loading): His-tagged ligand protein diluted in kinetics buffer to 5-25 µg/mL.

- Column 3 (Baseline): Kinetics buffer.

- Columns 4-6 (Association): Two-fold or three-fold serial dilutions of the analyte protein in kinetics buffer. For effector (ECâ‚…â‚€) analysis, also include a concentration gradient of the small molecule (e.g., 2-OG).

- Column 7 (Dissociation): Kinetics buffer.

- Column 8 (Regeneration): 10 mM glycine, pH 1.7, and 10 mM NiClâ‚‚ solution.

Step-by-Step Assay Procedure

The step-by-step procedure mirrors the workflow diagrammed in Section 2 and should be programmed into the BLI instrument's software.

- Baseline 1 (60 s): Dip the sensors into kinetics buffer (Column 1) to establish a stable baseline.

- Loading (300 s): Move the sensors to the ligand solution (Column 2) to immobilize the His-tagged protein onto the Ni-NTA biosensors. The signal should increase.

- Baseline 2 (60-180 s): Return the sensors to kinetics buffer (Column 3) to wash away unbound ligand and stabilize the signal.

- Association (600 s): Move the sensors to the wells containing the analyte (Columns 4-6). The binding of the analyte to the immobilized ligand will cause a positive wavelength shift. For robust kinetics, use at least five different analyte concentrations.

- Dissociation (600 s): Transfer the sensors back to kinetics buffer (Column 7). The dissociation of the analyte from the complex will cause a decrease in the signal.

- Regeneration (Optional): To reuse sensors, dip them into the regeneration solution (Column 8) to strip the ligand and analyte, followed by a brief immersion in NiClâ‚‚ to recharge the sensor surface.

Data Analysis and Kinetic Fitting

- Data Processing: In the BLI analysis software (e.g., FortéBio Data Analysis HT), load your dataset. Subtract the signal from a reference sensor dipped in buffer only (to correct for bulk refractive index shift) and align the curves to the start of the association phase.

- Model Fitting: Fit the processed association and dissociation data to a 1:1 binding model. The software will calculate the kon and koff for each analyte concentration and report a global KD (= koff / k_on).

- ECâ‚…â‚€ Determination: To determine the ECâ‚…â‚€ of an effector, plot the relative binding response (from the association phase) against the logarithm of the effector concentration. Fit the data to a sigmoidal dose-response curve in software like GraphPad Prism to calculate the ECâ‚…â‚€ value [18].

The following diagram visualizes the key steps in processing raw BLI data to extract meaningful kinetic constants.

Data Analysis Process

Advanced Applications and Protocol Notes

Emerging Techniques: The SpyBLI Pipeline

A significant innovation in BLI methodology is the SpyBLI pipeline, which addresses the major bottlenecks of binder purification and concentration determination [20]. This approach leverages the rapid, covalent SpyCatcher003-SpyTag003 interaction to achieve highly ordered and uniform immobilization of binders directly from crude mixtures, such as mammalian-cell supernatants or cell-free expression blends [20]. This enables accurate measurement of binding kinetics for numerous candidates in high throughput, dramatically accelerating workflows in antibody engineering and computational protein design.

Critical Considerations for a Robust Assay

- Ligand Immobilization Level: Optimal loading is critical. Overloading can cause steric hindrance and mass-transport limitations, while underloading results in a poor signal-to-noise ratio [20]. Aim for a loading level that gives a robust signal without distorting the kinetics.

- Analyte Concentration Range: The highest analyte concentration should be at least 5-10 times the expected KD to fully define the association curve, and the lowest should be around or below the KD to define the curvature accurately.

- Specificity Controls: Always include control sensors to test for non-specific binding of the analyte to the biosensor matrix itself. This is essential for validating that the observed signal is due to the specific interaction of interest.

- Regeneration Efficiency: If reusing sensors, ensure the regeneration step completely returns the signal to the original baseline without damaging the sensor's binding capacity over multiple cycles.

The precise determination of association (kon), dissociation (koff), and equilibrium (KD) constants is indispensable for a mechanistic understanding of biomolecular interactions. Bio-layer interferometry stands out as a powerful and accessible platform for obtaining these kinetic parameters in real time. The protocol detailed herein, encompassing both KD and ECâ‚…â‚€ determination, provides a reliable framework for researchers. Furthermore, the advent of advanced pipelines like SpyBLI promises to further enhance the throughput and efficiency of kinetic characterization, solidifying BLI's role as a cornerstone technology in modern life sciences research and therapeutic development.

Within the field of binding kinetics, particularly in the context of bio-layer interferometry (BLI), the "dip and read" methodology epitomizes a simplified, open-system approach. Unlike integrated microfluidic systems that manipulate fluids within sealed microchannels [21] [22], "dip and read" operates on an open architecture where sensor tips are directly immersed into sample-containing microwell plates. This paradigm eliminates the need for complex fluidic plumbing, valving, and priming, thereby streamlining the workflow for researchers focused on characterizing molecular interactions, such as protein-protein binding or nanobody affinity [23].

The core advantage of this system lies in its directness and operational simplicity. It functions on the "sample-in answer-out" principle [22], but without the fabrication and operational complexities associated with microfluidic chips. This makes it exceptionally suitable for high-throughput experimental designs [23], allowing scientists to run multiple kinetics experiments in parallel with minimal setup time. This article details the application of this elegant system, providing structured protocols and data analysis frameworks for binding kinetics research.

Key Advantages: Simplicity, Flexibility, and Throughput

The "dip and read" system offers several compelling benefits that align with the needs of modern drug development and basic research. These advantages are quantitative and qualitative, impacting both experimental outcomes and laboratory efficiency.

Table 1: Key Advantages of the "Dip and Read" Open System

| Advantage | Description | Impact on Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Simplified Setup | Eliminates intricate networks of microchannels, valves, and external pumps [21] [22]. | Reduces initial setup time and potential for fluidic failures; lowers the barrier to entry for non-specialists. |

| Low Sample Consumption | Manipulates samples in the microliter to picoliter range, consistent with microfluidic principles [21]. | Preserves valuable reagents and enables analysis from small sample volumes, such as patient biopsies. |

| High-Throughput Compatibility | Inherently parallel process; sensor tips can be run simultaneously in standard multi-well plates [23]. | Dramatically accelerates data collection for kinetics and epitope binning studies, streamlining drug screening. |

| Operational Flexibility | Open system allows for easy intervention, sample addition, or protocol adjustment between steps. | Facilitates complex, multi-step assays like competition experiments without redesigning the entire fluidic path. |

| Minimal Maintenance | No internal microchannels to clog or require cleaning; disposable sensor tips prevent cross-contamination. | Increases instrument uptime and reliability, reducing the need for extensive maintenance protocols. |

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful "dip and read" kinetics experiment relies on a defined set of core reagents and materials. The following table outlines the essential components for a standard protein-protein interaction study using BLI.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for BLI Kinetics

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BLI Instrument | Optical analytical instrument that measures biomolecular binding in real-time. | Instruments like the Octet platform are specifically designed for "dip and read" kinetics [23]. |

| Biosensor Tips | Disposable fiber-optic sensors functionalized with a capture molecule. | Pre-immobilized with Protein A, Streptavidin, or Anti-GST for ligand capture. |

| Ligand | The molecule immobilized on the biosensor surface. | A purified protein, antibody, or nanobody [23]. |

| Analyte | The molecule in solution that binds to the ligand. | Typically a purified protein; tested over a range of concentrations. |

| Assay Buffer | The solution matrix for dilution and binding steps. | Must be optimized to minimize non-specific binding; e.g., PBS with BSA. |

| Black 96- or 384-Well Plate | Microplate for housing samples and buffers. | Black plates minimize optical interference and well-to-well cross-talk. |

| Kinetics Analysis Software | Software for data processing, fitting, and calculating kinetic parameters. | Software provided with the instrument automates the calculation of ka, kd, and KD. |

Quantitative Data and Analysis

The primary output of a BLI kinetics experiment is a sensorgram, a real-time plot of binding response versus time. Analyzing this data provides the quantitative parameters that define the molecular interaction.

Table 3: Key Quantitative Parameters in Binding Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate Constant | ka | 1/Ms | Measures how quickly the analyte binds to the ligand. A higher ka indicates faster binding. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | kd | 1/s | Measures how quickly the complex falls apart. A lower kd indicates a more stable complex. |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant | KD | M | The ratio kd/ka; quantifies overall binding affinity. A lower KD indicates a higher affinity. |

| Response at Saturation | Rmax | nm | The maximum binding response, used to validate the assay model and immobilization level. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Nanobody Binding Kinetics

This protocol, adapted from a standard procedure for measuring protein-protein interactions [23], can be completed in approximately 3 hours and is suitable for users with minimal experience.

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Instrument and Software Setup: Power on the BLI instrument and open the kinetics analysis software. Initialize the system according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Biosensor Hydration: Hydrate a set of Anti-His Capture (HIS1K) biosensor tips in 200 µL of assay buffer in a black 96-well plate for at least 10 minutes before the experiment.

- Ligand and Analyte Preparation:

- Ligand (His-tagged antigen): Dilute the His-tagged target antigen to a final concentration of 5 µg/mL in assay buffer. Load 200 µL per well into at least 5 wells.

- Analyte (Nanobody): Prepare a 2-fold serial dilution series of the nanobody in assay buffer. A standard 5-point dilution starting from 100 nM is recommended. Include a zero-concentration well (buffer only) for double-referencing.

- Experimental Run: Set up the following method sequence in the software and execute the run.

- Baseline (60 sec): Dip sensors into a well containing 200 µL of assay buffer to establish a stable baseline.

- Loading (300 sec): Dip sensors into the ligand solution wells to capture the His-tagged antigen onto the biosensor surface.

- Baseline 2 (60 sec): Return to the assay buffer well to wash and stabilize the baseline post-loading.

- Association (300 sec): Dip sensors into the respective analyte (nanobody) dilution wells to measure the binding phase.

- Dissociation (600 sec): Return to the assay buffer well to measure the dissociation of the nanobody from the antigen.

- Data Analysis:

- Load the collected sensorgrams into the analysis software.

- Align the curves and subtract the reference sensorgram (buffer only) and baseline drift.

- Fit the processed data to a 1:1 binding model to extract the kinetic rate constants (ka and kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key stages of the "dip and read" BLI experiment protocol.

Advanced Applications: Competition and Epitope Binning

The "dip and read" system is highly adaptable for more complex assays. A prime example is epitope binning, used in antibody and nanobody screening to classify molecules based on their binding to overlapping regions (epitopes) on the target antigen [23].

In a sequential binding assay, the antigen is first loaded onto the sensor. A first nanobody (Nb 1) is associated, followed by a second nanobody (Nb 2). If Nb 2 cannot bind, it suggests it shares an epitope with Nb 1 and they are grouped in the same "bin." If Nb 2 binds additively, they target different epitopes.

Epitope Binning Experimental Design

Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) represents a powerful, label-free technology for the real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions. The core of the Octet BLI system lies in its disposable fiber-optic biosensors, which function as the solid support for capturing molecular partners. The critical first step in designing a robust BLI experiment is the appropriate selection of the biosensor, a choice that directly dictates the success of kinetic, affinity, and concentration analyses. This guide provides a detailed framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select between four fundamental biosensor formats: Streptavidin (SA), Ni-NTA, and Anti-IgG Fc (exemplified by the ARC and AHC2 biosensors), within the context of a binding kinetics research thesis. The selection directly influences the orientation, activity, and stability of the immobilized ligand, thereby affecting the quality and reliability of the derived kinetic parameters (kon, koff, KD). This document synthesizes application notes and protocols to streamline this vital decision-making process, ensuring data generated is both accurate and reproducible.

Biosensor Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles of BLI Biosensors

Octet BLI biosensors are dip-and-read probes coated with a proprietary biocompatible matrix that is uniform and non-denaturing, minimizing non-specific binding [24]. As light reflects from the sensor surface, an interference pattern is generated. The binding of molecules to the biosensor tip shifts this pattern, allowing for the real-time monitoring of binding events without any fluidics. This robust design supports a vast array of approaches to detecting and characterizing biological interactions, from simple quantitation to complex kinetic profiling.

Biosensor Comparison Table

The choice of biosensor is dictated by the biochemical properties of the molecules under investigation. The table below provides a quantitative summary of the key characteristics of the four primary biosensor types.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key BLI Biosensors

| Biosensor Type | Immobilization Target | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptavidin (SA) [25] | Biotinylated proteins or nucleic acids | Kinetic analysis, screening, and quantitation | High affinity and stability; robust, sensitive baseline; versatile for custom assays |

| Ni-NTA [26] | Poly-histidine (HIS) tags | Quantitation and kinetic characterization of HIS-tagged biomolecules | Direct quantitation; easy capture; works in buffer and diluted complex media |

| Anti-IgG Fc (ARC) [24] | Rabbit IgG (RbIgG) proteins | Lead identification, cell line and process development, QC | Flexible platform for a broad range of high-throughput applications |

| Anti-IgG Fc (AHC2) [24] | Human Fc-region containing proteins | Affinity characterization and quantitation of human IgGs | Second-generation biosensor for high-performance quantitation and kinetics |

Biosensor Selection Workflow

The following decision diagram outlines the logical process for selecting the most appropriate biosensor based on the properties of the molecule to be immobilized (the ligand).

Diagram 1: Biosensor Selection Flowchart

Detailed Biosensor Profiles and Protocols

Streptavidin (SA) Biosensors

Application Note

Octet SA Biosensors are among the most versatile tools in the BLI arsenal. They are designed for the immobilization of biotinylated biomolecules, including proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids, leveraging the high-affinity streptavidin-biotin interaction [25]. This interaction is renowned for its robustness and stability, making SA biosensors ideal for demanding applications such as detailed kinetic analysis (e.g., determining kon and koff rates), high-throughput screening, and precise quantitation of target analytes [25]. The biosensor surface provides a highly sensitive and stable baseline, which is critical for obtaining high-quality kinetic data.

Experimental Protocol for Kinetic Analysis

Objective: To determine the binding kinetics between a biotinylated ligand and its analyte in solution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 2: Essential Reagents for SA Biosensor Assay

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Octet SA Biosensors [25] | Solid support for immobilizing biotinylated ligands via streptavidin-biotin interaction. |

| Biotinylated Ligand | The molecule of interest, purified and biotinylated using established protocols. |

| Analyte | The binding partner in solution, serially diluted for the concentration series. |

| Kinetics Buffer | Suitable assay buffer (e.g., PBS), often supplemented with a carrier protein like BSA and a surfactant to minimize non-specific binding. |

| Octet BLI System | The instrument platform for performing the bio-layer interferometry measurements. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Reconstitution and Dilution: Reconstitute or dilute the biotinylated ligand and the analyte in a suitable kinetics buffer. It is critical that the buffer is compatible with the interaction and minimizes non-specific binding.

- Ligand Immobilization: Hydrate the SA biosensors in kinetics buffer for at least 10 minutes. Immobilize the biotinylated ligand by dipping the biosensors into a solution of the ligand for a defined time (typically 5-15 minutes) to achieve an optimal immobilization level (e.g., 1-2 nm shift).

- Baseline Establishment: Transfer the biosensors to a well containing only kinetics buffer for 60-120 seconds to establish a stable baseline.

- Association Phase: Move the biosensors to wells containing a concentration series of the analyte (e.g., 3-fold serial dilutions). The association phase typically lasts 300-600 seconds, during which the analyte binds to the immobilized ligand.

- Dissociation Phase: Finally, transfer the biosensors back to a well with kinetics buffer for 600-1800 seconds to monitor the dissociation of the analyte from the ligand.

- Data Analysis: The collected data is reference-subtracted (using a buffer-only sensor) and fit to a suitable binding model (e.g., 1:1 binding model) using the Octet Analysis Software to extract the association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

Ni-NTA Biosensors

Application Note

Octet NTA Biosensors are pre-immobilized with nickel-charged tris-nitriloacetic acid (Tris-NTA), making them the ideal choice for the capture and study of poly-histidine (HIS) tagged proteins [26]. This format takes advantage of the ubiquitous use of HIS-tags in the biopharmaceutical industry. The primary applications include the direct quantitation of HIS-tagged proteins and their easy capture for subsequent kinetic analysis with binding partners. A significant advantage is their functionality in both simple buffers and diluted complex media, offering flexibility in experimental design [26].

Experimental Protocol for HIS-Tagged Protein Quantitation

Objective: To directly quantify the concentration of an unknown HIS-tagged protein sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ni-NTA Quantitation Assay

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Octet NTA Biosensors [26] | Capture HIS-tagged proteins via coordination with nickel-charged Tris-NTA. |

| HIS-tagged Protein Standard | A purified protein of known concentration for generating a standard curve. |

| Unknown Samples | The samples containing the HIS-tagged protein at an unknown concentration. |

| Assay Buffer | A compatible buffer, which can be PBS or a diluted complex medium like cell culture supernatant. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a series of known concentrations of the HIS-tagged protein standard in assay buffer (e.g., 0, 5, 10, 25, 50 µg/mL).

- Biosensor Hydration: Hydrate the NTA biosensors in assay buffer for at least 10 minutes before the experiment.

- Baseline Step: Dip the biosensors into assay buffer for 60 seconds to establish a stable baseline.

- Loading Step: Transfer the biosensors to the wells containing the standard solutions to load the HIS-tagged protein onto the sensor surface. The loading time should be consistent (e.g., 300 seconds).

- Standard Curve Generation: The Octet system measures the shift in interference for each standard. The response at the end of the loading step is plotted against the known concentration to generate a standard curve, which is fitted with a linear or non-linear regression.

- Unknown Sample Measurement: Repeat steps 3 and 4 with the unknown samples. The response from the unknown is interpolated from the standard curve to determine its concentration.

Anti-IgG Fc Biosensors (ARC & AHC2)

Application Note

Anti-IgG Fc biosensors are workhorses for antibody-related research and development. The Octet ARC Biosensors are designed for capturing rabbit IgG (RbIgG) proteins, while the second-generation Octet AHC2 Biosensors are optimized for the quantitation and kinetic characterization of human IgG and other human Fc-region containing proteins [24]. They offer a flexible platform for a broad range of high-throughput applications, including lead identification and optimization, cell line development, process development, and quality control [24]. Their primary advantage is the oriented capture of antibodies via the Fc region, which leaves the antigen-binding Fab regions free and accessible for interaction, thereby maximizing assay sensitivity.

Experimental Protocol for Affinity Characterization

Objective: To characterize the binding affinity of a captured monoclonal antibody (mAb) to its antigen.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the human or rabbit IgG (the ligand) and a concentration series of its antigen (the analyte) in kinetics buffer.

- Biosensor Preparation: Hydrate the AHC2 (for human IgG) or ARC (for rabbit IgG) biosensors in buffer.

- Antibody Capture: Establish a baseline, then dip the biosensors into a well containing the IgG solution to capture the antibody onto the sensor surface for a fixed time. The goal is a consistent capture level across all sensors.

- Baseline 2: Briefly return the biosensors to a buffer well to stabilize the signal.

- Association: Expose the antibody-loaded biosensors to the serial dilutions of the antigen for a set time to monitor the association phase.

- Dissociation: Transfer the biosensors to a buffer well to monitor the dissociation of the antigen.

- Data Analysis: Reference-subtract the data and fit it to a 1:1 binding model to extract the kinetic rate constants and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized step-by-step workflow for a standard kinetic experiment using BLI, which is applicable across the different biosensor types with modifications primarily in the loading step.

Diagram 2: BLI Kinetic Assay Workflow

The strategic selection of a biosensor is the cornerstone of a successful BLI experiment for binding kinetics research. Streptavidin (SA) biosensors offer unmatched versatility and stability for biotinylated ligands, while Ni-NTA biosensors provide a direct route for working with HIS-tagged molecules. The Anti-IgG Fc formats (AHC2 and ARC) deliver oriented capture for antibody-focused applications, ensuring high-quality data in lead optimization and quality control. By aligning the biochemical properties of the ligand with the immobilized capture agent on the biosensor, as detailed in this guide, researchers can design robust, reproducible, and informative assays. This systematic approach to biosensor selection ultimately accelerates the drug development process, from early-stage discovery through to bioprocessing and quality control.

BLI in Action: Methodologies and Diverse Applications in Biomedical Research

Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) is a powerful, label-free optical technique for analyzing the real-time kinetics of biomolecular interactions. It is extensively used in biomedical research and drug development to determine binding affinity, rates of association and dissociation, and concentration. Unlike other biosensor techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), BLI operates without microfluidics, using a "Dip and Read" approach where disposable biosensor tips are moved between solutions in a microplate. This eliminates issues with system clogging, reduces maintenance, and allows for higher throughput and sample recovery [27] [19]. This application note provides a detailed standard protocol for performing robust BLI experiments, focusing on the critical steps of immobilization, baseline, association, and dissociation.

BLI Workflow and Principle of Operation

The following diagram illustrates the step-by-step workflow of a typical BLI kinetics experiment, from sensor preparation to data analysis.

Figure 1: The standard BLI experimental workflow. The graphic abstract outlines the key stages of a BLI binding experiment, correlating each step with the resulting interferogram. The principle of BLI is based on the interference pattern of white light reflected from two surfaces: an internal reference layer and the protein-coated biosensor layer. The measured wavelength shift (Δλ) is directly proportional to the thickness of the molecular layer bound to the biosensor surface, allowing real-time measurement of binding events [27] [28].

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Biosensor Selection and Ligand Immobilization

The first critical step is the stable and specific immobilization of one binding partner (the ligand) onto the biosensor.

- Biosensor Choice: Select a biosensor with a chemistry that matches your ligand. Common types include Streptavidin (SA), Anti-His (AH), and Amine Reactive (AR) sensors [27] [19]. For example, streptavidin sensors are ideal for capturing biotinylated ligands like lipids or peptides, while Ni-NTA (NTA) sensors are used for his-tagged proteins [27] [28].

- Loading Concentration and Time: Ligand concentration and loading time must be optimized to achieve an appropriate immobilization level ("response"). A response between 0.5 nm and 2.5 nm is often targeted, as excessively high density can cause steric hindrance or rebinding artifacts [19]. A typical protocol uses 5-25 µg/ml of his-tagged protein for loading onto NTA sensors [28].

- Minimizing Non-Specific Binding: A blocking step with an irrelevant protein like BSA can be included after ligand immobilization to minimize non-specific binding of the analyte to the sensor surface [19].

Table 1: Common Biosensor Types and Their Applications

| Biosensor Type | Immobilization Chemistry | Recommended Ligand | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptavidin (SA) | High-affinity biotin binding | Biotinylated proteins, peptides, lipids (e.g., biotinylated PI3P) [27] | Requires biotinylated ligand; very stable interaction. |

| Anti-His (AH) | Binds polyhistidine tags | His-tagged recombinant proteins [28] | Specific for his-tags; can be regenerated for reuse. |

| Ni-NTA (NTA) | Binds polyhistidine tags | His-tagged recombinant proteins [28] | Similar to AH; requires NiClâ‚‚ solution for recharging [28]. |

| Amine Reactive (AR) | Covalent coupling via NHS-ester | Proteins with primary amines (lysine) [19] | Covalent immobilization; requires specific pH (e.g., pH 5.0) [19]. |

Baseline Establishment

A stable baseline is fundamental for accurate kinetic measurement.

- Purpose: The baseline establishes the optical reference point, representing the signal from the immobilized ligand before analyte binding [27] [28].

- Procedure: After ligand immobilization, the biosensor is transferred to a well containing only the running buffer. The signal is allowed to stabilize, resulting in a flat line.

- Best Practices: Use the same buffer for baseline and dissociation steps to prevent bulk shift effects from buffer mismatches. Ensure adequate shaking (e.g., 1000 rpm) during this step to ensure proper mixing and signal stability [19].

Association Phase

During the association phase, the ligand-immobilized biosensor is dipped into a solution containing the analyte, and binding is measured.

- Procedure: The biosensor is transferred from the baseline well to a well containing the analyte. The subsequent increase in signal thickness corresponds to the binding of analyte to the immobilized ligand over time [27].

- Analyte Concentration Series: To determine kinetic parameters, the association phase must be performed with a series of analyte concentrations, typically using a serial dilution. A minimum five-point, threefold serial dilution is common [19]. The analyte molar concentration should be at least five times higher than that of the ligand [28].

- Duration: The association step should last long enough to approach binding saturation for at least the highest analyte concentration, often 5-15 minutes [19].

Dissociation Phase

The dissociation phase measures the stability of the formed complex.

- Procedure: The biosensor is moved from the analyte solution back into a well containing only running buffer. The subsequent decrease in signal represents the dissociation of the analyte from the ligand over time [27].

- Sink Condition: For accurate measurement of the dissociation rate (k~off~), it is critical to prevent rebinding of analyte to the ligand. This is achieved by using "sink conditions", where the dissociation buffer is spiked with a high concentration of a competing molecule that captures dissociated analyte, or by using a large volume of fresh buffer that is used only once [19].

- Duration: The dissociation phase should be long enough to observe a significant decay in the binding signal, which can sometimes require up to one hour [19].

Data Processing and Analysis

The following diagram outlines the core logic path for processing raw BLI data to extract meaningful kinetic parameters.

Figure 2: BLI data analysis workflow. Software analyzes the wavelength shift over time to generate binding sensorgrams. The response at equilibrium (R~eq~) for each analyte concentration is plotted to determine the dissociation constant (K~D~) via steady-state analysis. Alternatively, by globally fitting the association and dissociation curves to a binding model (e.g., 1:1 binding), the software can determine the association rate (k~on~) and dissociation rate (k~off~), from which the K~D~ (k~off~/k~on~) is derived [28].

Table 2: Key Kinetic Parameters Derived from BLI Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate | k~on~ (Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) | Speed at which the analyte binds to the ligand. | A higher k~on~ indicates faster complex formation. |

| Dissociation Rate | k~off~ (sâ»Â¹) | Speed at which the analyte-ligand complex dissociates. | A lower k~off~ indicates a more stable complex. |

| Dissociation Constant | K~D~ (M) | k~off~ / k~on~; the analyte concentration at which half the ligand is bound. | A lower K~D~ indicates higher binding affinity. |

| Half Maximal Effective Concentration | ECâ‚…â‚€ / ICâ‚…â‚€ (M) | Concentration of an effector that gives a half-maximal response. | Potency of an effector molecule to promote or inhibit binding [28]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful BLI experiment requires careful preparation of high-quality reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BLI

| Reagent / Material | Function and Specification | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| BLI Biosensors | Disposable fiber-optic tips functionalized for ligand capture. | Streptavidin (SA) biosensors for biotinylated phosphoinositides [27]; Ni-NTA (NTA) biosensors for his-tagged proteins [28]. |

| Running Buffer | The solution in which binding takes place; must be optimized for the interaction. | PBS with 0.002% Tween-20 [27]; HBS-EP buffer [19]. |

| Ligand | The molecule immobilized on the biosensor. | Biotinylated Phosphatidic Acid (b-PA) [27]; 6xHis-tagged PII signaling protein [28]. |

| Analyte | The molecule in solution that binds to the immobilized ligand. | Purified full-length Vam7 protein [27]; Strep-tagged PirC protein [28]. |

| Regeneration Buffer | A solution that removes bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand, enabling sensor reuse. | 10 mM Glycine, pH 1.7 [28]; A cocktail of Gentle IgG Elution Buffer and 4 M NaCl [19]. |

| Blocking Agent | Used to coat unused sensor surfaces to prevent non-specific binding of the analyte. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) at 1 mg/ml [19]. |

| Crotocin | Crotocin, CAS:21284-11-7, MF:C19H24O5, MW:332.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Alisol F 24-acetate | Alisol F 24-acetate, CAS:443683-76-9, MF:C32H50O6, MW:530.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Beyond standard protein-protein interaction studies, BLI is highly versatile. It can be used to measure protein-lipid interactions, as demonstrated by binding Vam7 to phosphoinositides [27]. Furthermore, BLI is ideal for competitive binding and epitope binning experiments, which are crucial for antibody and nanobody screening [23]. The platform can also be used to study the allosteric effects of small molecules, where a catalytic-site ligand induces conformational changes in an enzyme [29].

In conclusion, this protocol outlines the best practices for executing a robust BLI experiment. By carefully following these guidelines for immobilization, baseline, association, and dissociation, researchers can obtain high-quality, reproducible kinetic data to advance their research and drug development projects.

Integral membrane proteins are crucial cellular components, governing signal transduction, molecular transport, and intercellular communication. Despite their biological and therapeutic significance, studying their interactions with binding partners presents substantial technical challenges due to their hydrophobic nature and requirement for lipid environments to maintain native structure. Conventional interaction analysis methods typically necessitate time-consuming purification and reconstitution of membrane proteins into artificial membrane systems such as liposomes, nanodiscs, or supported lipid bilayers.

This Application Note presents a groundbreaking methodological advance: the direct analysis of membrane protein-protein interactions in a membraneless setting using proteomicelles coupled with biolayer interferometry (BLI). This approach bypasses the need for functional reconstitution while enabling real-time, label-free kinetics measurements of transient complexes at high signal-to-noise ratios. We detail the underlying principles, provide comprehensive protocols, and demonstrate applications for drug discovery and basic research.

Conceptual Foundation and Advantages

The Proteomicelle Approach

The core innovation described in this method involves utilizing proteomicelles – membrane proteins solubilized in detergent micelles – directly in binding kinetics experiments without reconstitution into lipid bilayers [30]. This membraneless approach maintains membrane proteins in a soluble, functional state by preserving their native extracellular domains while eliminating the multiple steps typically required for protein solubilization, renaturing, and functional reconstitution.

When coupled with BLI technology, this system enables real-time measurements probing both association and dissociation phases of transient membrane protein complexes [30]. The method employs free proteomicelles in solution, containing membrane proteins equipped with programmable antibody mimetic binders that target specific protein ligands attached to sensor surfaces.

Key Advantages Over Conventional Methods

- Elimination of Reconstitution Steps: The most significant advantage is bypassing the need to transfer membrane proteins from native membranes into supported lipid bilayers, liposomes, or nanodiscs [30].