Conformational Selection vs. Induced Fit: Decoding Molecular Recognition Mechanisms for Advanced Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the two dominant paradigms in molecular recognition—conformational selection and induced fit—and their critical implications for structure-based drug discovery.

Conformational Selection vs. Induced Fit: Decoding Molecular Recognition Mechanisms for Advanced Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the two dominant paradigms in molecular recognition—conformational selection and induced fit—and their critical implications for structure-based drug discovery. We explore the foundational thermodynamic and kinetic principles that distinguish these mechanisms, detailing advanced computational methodologies like IFD-MD and ensemble docking that address protein flexibility. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content offers practical insights on troubleshooting pose prediction inaccuracies and validating models through free energy calculations and kinetic analysis. By synthesizing current evidence that conformational selection may be more prevalent than historically assumed, and highlighting the emergence of hybrid mechanisms, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select optimal strategies for predicting ligand binding and accelerating therapeutic development.

Lock-and-Key and Beyond: Foundational Models of Molecular Recognition

The mechanism by which proteins recognize and bind their ligands represents a fundamental problem in molecular biology with profound implications for understanding cellular signaling, enzyme catalysis, and rational drug design. For over a century, our conceptual framework for describing these interactions has evolved substantially—from viewing biomolecules as static structures to understanding them as dynamic entities exploring complex energy landscapes. This evolution reflects a deeper understanding of protein dynamics and how conformational flexibility dictates function. Within the context of modern molecular recognition research, a central thesis has emerged: the debate between conformational selection and induced fit as competing or complementary mechanisms for binding. While early models presented these as mutually exclusive pathways, contemporary research reveals a more nuanced reality where both processes often operate in concert, with their relative contributions determined by the specific biological system, experimental conditions, and temporal scales examined. This whitepaper traces the conceptual journey from rigid structural models to dynamic ensemble-based perspectives, synthesizing current experimental and computational approaches for dissecting binding mechanisms, and providing researchers with methodological frameworks for probing these fundamental biological processes.

Historical Trajectory of Binding Models

The Lock-and-Key Hypothesis (1894)

- Proposer: Emil Fischer

- Core Principle: Complementarity in rigid structures; the ligand (key) possesses a shape that perfectly fits the static binding site of the protein (lock).

- Historical Context: This model provided a foundational understanding of molecular specificity, explaining how enzymes distinguish between stereoisomers. Its limitation lay in the inability to explain allosteric regulation or binding-induced conformational changes.

- Modern Perspective: Now understood as a special case within broader models, applicable primarily to systems with minimal conformational change upon binding [1] [2].

The Induced Fit Model (1958)

- Proposer: Daniel Koshland

- Core Principle: Binding precedes conformational change; the initial collision between a protein and ligand induces a structural rearrangement in the protein to form a complementary binding interface [3] [4].

- Significance: Successfully explained cooperativity in allosteric proteins and how proteins can bind multiple different ligands. It represented the first major step toward incorporating protein flexibility into recognition models.

- Kinetic Signature: Under pseudo-first-order conditions ([L]â‚€ >> [P]â‚€), the dominant relaxation rate (kâ‚’bâ‚›) increases monotonically with ligand concentration [L]â‚€ [5].

The Conformational Selection Model (1964+)

- Proposers: Straub (concept), Frauenfelder, Sligar, and Wolynes (energy landscape theory)

- Core Principle: Conformational change precedes binding; an unliganded protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium between multiple conformations. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing complementary conformation, shifting the equilibrium toward the bound state [1] [4].

- Significance: Emphasized the intrinsic dynamics of proteins and connected binding phenomena to the energy landscape theory.

- Kinetic Signature: The relationship between kâ‚’bâ‚› and [L]â‚€ is more complex. kâ‚’bâ‚› can decrease monotonically with [L]â‚€ (when conformational excitation rate kâ‚‘ < unbinding rate kâ‚‹) or increase under other conditions [5].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Historical Binding Models

| Model | Temporal Order | View of Protein Dynamics | Theoretical Basis | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lock-and-Key | N/A | Proteins are essentially rigid. | Structural complementarity. | Cannot explain conformational changes or allostery. |

| Induced Fit | Binding => Change | Flexibility is induced by the ligand. | KNF allosteric model. | Downplays intrinsic protein dynamics in the unbound state. |

| Conformational Selection | Change => Binding | Proteins are dynamic ensembles. | MWC allosteric model & energy landscape theory. | Can underemphasize ligand-induced adjustments. |

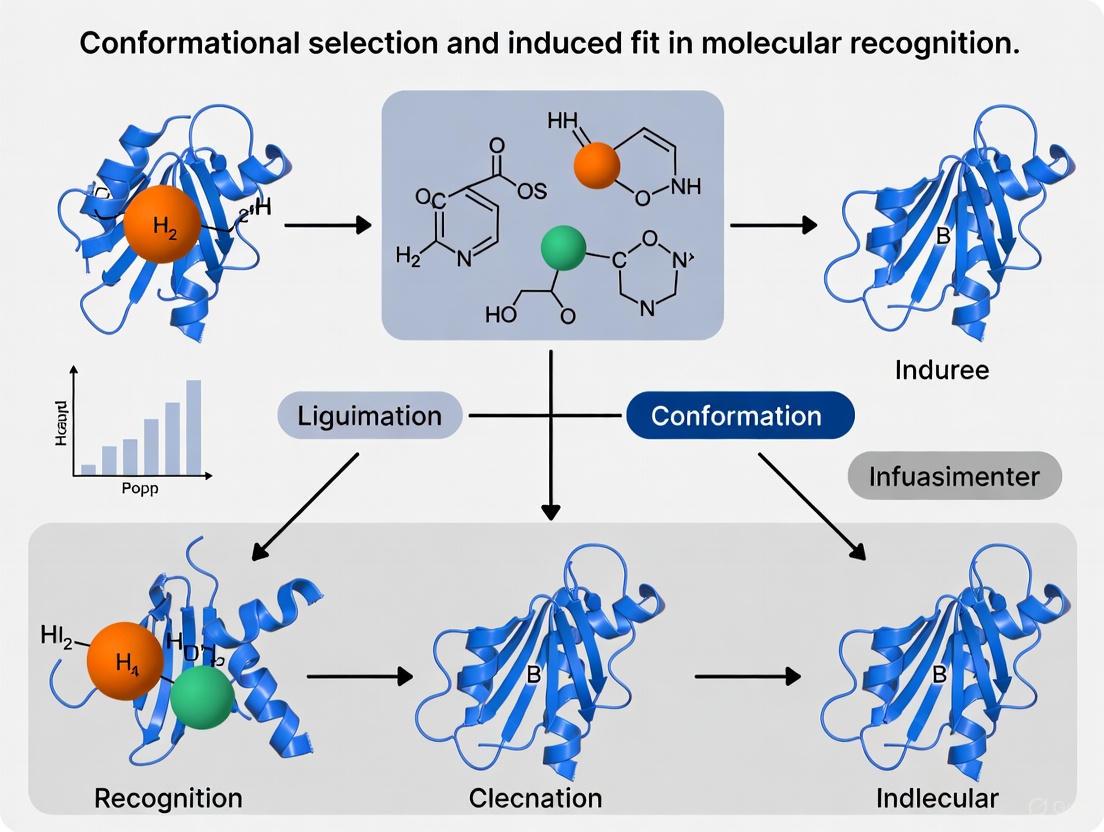

Figure 1: The conceptual evolution of protein-ligand binding models, culminating in the modern integrated view.

The Modern Synthesis: An Integrated View of Binding

The historical dichotomy between induced fit and conformational selection has been largely resolved by experimental evidence showing that both mechanisms are often at play in a single binding event, forming an extended conformational selection model [1] [2] [6].

The Extended Conformational Selection Model

This generalized framework posits that binding occurs through a repertoire of selection and adjustment steps [1]. The initial encounter may involve selection from a pre-existing ensemble of protein conformations, followed by subsequent, often minor, induced-fit adjustments to optimize complementarity and binding affinity. This model successfully incorporates the older models as special cases:

- Lock-and-Key: A single, rigid pre-existing conformation is selected.

- Pure Conformational Selection: Binding to a pre-existing state without subsequent adjustment.

- Pure Induced Fit: Binding to an initial state followed by a major conformational change.

Factors Governing the Dominant Mechanism

The balance between selection and induced fit is influenced by system-specific variables:

- Ligand Concentration: High ligand concentrations favor induced fit by increasing the probability of initial collision with the dominant, unliganded state [1].

- Interaction Nature: Strong, long-range electrostatic interactions favor induced fit, while weaker, short-range hydrophobic interactions favor conformational selection [3] [4].

- Timescales: Conformational selection dominates when intrinsic protein dynamics are slow relative to binding; induced fit dominates when conformational transitions are fast [3] [4].

- Partner Rigidity: A large flexibility difference between partners (e.g., a rigid small molecule and a flexible protein) favors induced fit in the more flexible partner [1].

Table 2: Experimental Distinction Between Induced Fit and Conformational Selection

| Characteristic | Induced Fit | Conformational Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Sequence | Ligand binds before conformational change. | Conformational change occurs before binding. |

| Ligand Role | Active inducer of change. | Passive selector of pre-existing state. |

| Kinetics (kâ‚’bâ‚› vs. [L]â‚€) | Monotonic increase under pseudo-first-order conditions. | Can decrease or increase; complex dependence. |

| Dominant When... | Ligand concentration is high; conformational transitions are fast. | Ligand concentration is low; conformational transitions are slow. |

| Representative System | GID4 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase [7] | LAO Protein (partial mechanism) [3] [4] |

Experimental Toolkit for Dissecting Binding Mechanisms

Distinguishing between binding mechanisms requires techniques that probe protein structure, dynamics, and kinetics, often under native-like conditions.

Key Biophysical Techniques

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Ideal for detecting low-populated, excited states in the unliganded protein and characterizing dynamics on microsecond-to-millisecond timescales. Chemical shift perturbations and relaxation dispersion can reveal pre-existing conformations.

- Single-Molecule Fluorescence/FRET: Allows direct observation of heterogeneity in conformational states and dynamics without ensemble averaging. Can track individual molecules transitioning between states before and after binding.

- Stopped-Flow Chemical Relaxation: The gold-standard for kinetic analysis. By rapidly perturbing binding equilibrium (e.g., by temperature jump or rapid mixing) and monitoring the relaxation of the system, one can measure the dominant relaxation rate kâ‚’bâ‚› as a function of ligand concentration [L]â‚€, which provides the critical signature for mechanism identification [5].

- X-ray Crystallography & Cryo-EM: Provide high-resolution structural snapshots of end states (apo and holo). Comparison can reveal the scale of conformational change but cannot directly speak to dynamics or the order of events.

Critical Reagents and Assays

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Mechanism Studies

| Reagent / Assay | Function in Research | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins (¹âµN, ¹³C) | Enables detailed NMR spectroscopy by providing observable nuclei. | Essential for probing backbone and side-chain dynamics and identifying minor states. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (Donor/Acceptor Pairs) | Label proteins for FRET-based distance measurements. | Critical for single-molecule and ensemble FRET studies tracking conformational changes in real time. |

| Stopped-Flow Instrumentation | Rapidly mixes protein and ligand solutions to initiate binding. | Enables measurement of binding kinetics on millisecond timescales. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Generates proteins with specific mutations in the binding site or allosteric networks. | Tests the functional role of specific residues in stabilizing certain conformations. |

| T-Type calcium channel inhibitor 2 | T-Type Calcium Channel Inhibitor 2|CaV3 Blocker | T-Type Calcium Channel Inhibitor 2 is a potent CaV3.1, CaV3.2, and CaV3.3 blocker for neurology and cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Pim1-IN-7 | Pim1-IN-7, MF:C23H23N5O, MW:385.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Framework: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis

The most rigorous method for distinguishing mechanisms is through the quantitative analysis of binding kinetics.

General Kinetic Analysis Beyond Pseudo-First-Order Conditions

Traditional analyses often rely on the pseudo-first-order approximation ([L]â‚€ >> [P]â‚€). However, recent work provides general analytical results for the dominant relaxation rate kâ‚’bâ‚› that are valid for all protein and ligand concentrations [5]. This is critical because an increase of kâ‚’bâ‚› with [L]â‚€ under pseudo-first-order conditions is ambiguous, as it can occur in both induced fit and conformational selection.

- For Induced Fit Binding: The function kâ‚’bâ‚›([L]â‚€) exhibits a symmetrical minimum at [L]â‚€áµâ±â¿ = [P]â‚€ - Kð’¹ for [P]â‚€ > Kð’¹. At high [P]â‚€, kâ‚’bâ‚› approaches the same value for [L]â‚€ << [P]â‚€ and [L]â‚€ >> [P]â‚€ [5].

- For Conformational Selection Binding: The function kâ‚’bâ‚›([L]â‚€) can exhibit a minimum, but it is not symmetrical. At high [P]â‚€, the value of kâ‚’bâ‚› for [L]â‚€ << [P]â‚€ can be much larger than for [L]â‚€ >> [P]â‚€ [5].

Experimental Protocol: Temperature-Jump Relaxation Kinetics

This is a classic method for probing the kinetics of biological reactions.

- Objective: To measure the rate at which a protein-ligand mixture returns to equilibrium after a rapid perturbation.

- Procedure: a. Prepare a solution of protein and ligand at a defined concentration ratio and allow it to reach binding equilibrium. b. Apply a rapid temperature jump (e.g., using an infrared laser pulse), which instantaneously shifts the equilibrium constant. c. Monitor a spectroscopic signal (e.g., fluorescence, UV-Vis absorbance) as a function of time as the system relaxes to the new equilibrium. d. Fit the relaxation curve to extract the observed rate constant(s), kâ‚’bâ‚›. e. Repeat the experiment across a wide range of total ligand [L]â‚€ and protein [P]â‚€ concentrations.

- Data Analysis: Plot kâ‚’bâ‚› as a function of [L]â‚€. The shape and symmetry of this plot are used to discriminate between the induced fit and conformational selection models according to the general principles outlined above [5].

Figure 2: A generalized workflow for using chemical relaxation kinetics to distinguish between binding mechanisms.

Case Studies in Hybrid Binding Mechanisms

LAO Binding Protein

The LAO protein, which undergoes a large open-to-closed transition upon binding arginine, was long assumed to operate via a pure induced fit mechanism because the closed state completely buries the ligand.

- Finding: Atomistic simulations using Markov State Models (MSMs) revealed a more complex picture. The ligand-free protein can sample a partially closed "encounter complex" state, indicating conformational selection. However, the fully closed state was only achieved after ligand binding to this intermediate, demonstrating a clear induced fit step [3] [4].

- Mechanism: Conformational selection (Open ⇌ Partially Closed) followed by induced fit (Partially Closed + Ligand → Closed).

GID4 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase

GID4 recognizes N-degrons, with structural data showing loop rearrangements upon peptide binding, suggesting induced fit.

- Finding: All-atom molecular dynamics simulations showed that the binding loops are highly flexible and spontaneously sample "open" and "closed" conformations even without the ligand.

- Mechanism: A hybrid mechanism where the ligand selects for pre-existing closed-conformer populations, with binding subsequently inducing further structural quakes to optimize the interaction [7].

Calreticulin Family of Chaperones

These lectins specifically recognize monoglucosylated N-glycan during ER protein folding.

- Finding: Simulations of the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) in free and bound states showed an ensemble of conformations. The initial contact is driven by conformational selection, which is then followed by glycan-induced fluctuations in key residues for stronger binding [6].

- Mechanism: A mixed mechanism of conformational selection and induced fit is critical for selective recognition among a pool of similar glycans [6].

The evolution of binding models from rigid bodies to dynamic partners underscores a fundamental shift in molecular biology: a transition from a purely structural view to a statistical mechanical and kinetic perspective. The "extended conformational selection" model, which integrates concepts of selection and adjustment, currently provides the most comprehensive framework for understanding molecular recognition. The prevailing thesis in the field is that pure mechanisms are the exception; most biological binding events proceed through a combination of pathways, with the dominant route influenced by environmental conditions and intrinsic protein properties.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated view has critical implications. Rational drug design, particularly for allosteric modulators, must account for the intrinsic conformational landscape of the target protein. Strategies that combine ensemble-based docking (to account for conformational selection) with flexibility in the binding site (to account for induced fit) are likely to be more successful. The future of unravelling binding mechanisms lies in the integration of multiple experimental techniques with advanced computational simulations, such as MSMs, to map the complete energy landscape of binding, thereby bridging the gap between static structural biology and the dynamic reality of protein function in the cellular environment.

The Induced Fit Hypothesis stands as a foundational concept in molecular biology, proposing that the conformational change in a protein occurs after the initial binding of a ligand. This model contrasts with the Conformational Selection mechanism, wherein the ligand selectively binds to a pre-existing, minor conformation within the protein's dynamic ensemble. The distinction between these two mechanisms—whether a conformational change happens before (Conformational Selection) or after (Induced Fit) ligand binding—is not merely academic; it has profound implications for understanding signaling kinetics, allosteric regulation, and rational drug design [8] [5].

For decades, the Induced Fit model, introduced by Daniel Koshland, has provided a intuitive framework for explaining how enzymes achieve specificity and how ligands can stabilize active conformations. This technical guide deconstructs the Induced Fit hypothesis by examining the fundamental principles, experimental methodologies, and computational tools used to characterize ligand-induced conformational changes. Furthermore, it situates this mechanism within the modern context of conformational ensembles, where the binary view of Induced Fit versus Conformational Selection is increasingly giving way to a more integrated perspective that acknowledges contributions from both pathways [9] [10].

Core Principles and the Energetics of Induced Fit

The central tenet of the Induced Fit model is that the binding event itself alters the energy landscape of the protein, making previously inaccessible conformational states thermally accessible. In this mechanism, the ligand first binds to the protein in a conformation that may not be the most complementary, forming an initial encounter complex. This binding then induces a conformational rearrangement—often involving sidechain reorientations, loop movements, or shifts in secondary structure elements—that results in the final, stable complex [8].

From a thermodynamic perspective, the stabilization of the bound conformation is described by the dissociation free energy. When a ligand binds, the protein-ligand complex is stabilized, leading to measurable changes in the protein's energetic properties. These include an increase in thermodynamic stability and a decrease in the unfolding rate. This stabilization forms the basis for energetics-based methods to detect and study protein-ligand interactions, as the ligand-bound form will be more resistant to denaturation by chaotropic agents or proteolysis [11].

A key functional outcome of Induced Fit is the creation of a complementary binding surface. The initial binding site may be more open or accessible, with the final, high-affinity interface forming only after the conformational change. This process is particularly relevant for enzymes and receptors where precise alignment of catalytic residues or gating elements is required for function.

Distinguishing Induced Fit from Conformational Selection

While both Induced Fit and Conformational Selection can lead to the same final ligand-bound structure, their kinetic pathways and ligand concentration dependencies are fundamentally different. Accurately distinguishing between them is crucial for a mechanistic understanding.

Kinetic Signatures and Mutational Analysis

The most definitive way to distinguish these mechanisms is through kinetic analysis, specifically by examining how the dominant relaxation rate ((k_{obs})) of the binding reaction changes as a function of total ligand concentration ([L]â‚€) and through the use of allosteric mutants [8] [5].

- Induced Fit Mechanism: The conformational change occurs after binding. Therefore, an allosteric mutation that affects the conformational equilibrium will predominantly alter the dissociation rate constant ((k{off})), while the association rate constant ((k{on})) remains relatively unaffected. The plot of (k_{obs}) versus [L]â‚€ is symmetric and exhibits a minimum at [L]â‚€ = [P]â‚€ - Kd for protein concentrations [P]â‚€ larger than the dissociation constant Kd [5].

- Conformational Selection Mechanism: The conformational change occurs before binding. Here, the same allosteric mutation will primarily affect (k{on}), as it alters the population of the pre-existing binding-competent state. The function (k{obs})([L]â‚€) is not symmetric and can decrease monotonically with [L]â‚€ (for low conformational excitation rates) or show a minimum at a different location than in Induced Fit [5].

This kinetic strategy was successfully applied to a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel. Mutagenesis of allosteric residues was found to affect only the dissociation rate constant, providing strong evidence that binding follows an Induced Fit mechanism [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics for Distinguishing Binding Mechanisms

| Feature | Induced Fit | Conformational Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Order | Conformational change occurs after ligand binding. | Conformational change occurs before ligand binding. |

| Effect of Allosteric Mutant on (k_{on}) | Minimal or no effect. | Significant effect. |

| Effect of Allosteric Mutant on (k_{off}) | Significant effect. | Minimal or no effect. |

| Dependence of (k_{obs}) on [L]â‚€ | Symmetric function with a minimum at [L]â‚€ = [P]â‚€ - Kd. | Not symmetric; can decrease monotonically or show a minimum at a different [L]â‚€. |

| Pre-existing Conformation | Not required; the active state may be poorly populated or non-existent without ligand. | Required; the active state must exist, albeit potentially at low population, in the apo ensemble. |

Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Discrimination

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for distinguishing between Induced Fit and Conformational Selection using kinetic analysis.

Quantitative Experimental Methods and Protocols

Several sophisticated biophysical and biochemical techniques are employed to detect and quantify ligand-induced conformational changes.

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Kinetics

This rapid-mixing technique is ideal for measuring the kinetics of binding and conformational changes on millisecond timescales [8].

- Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Purify the protein (e.g., a cyclic nucleotide-binding domain) and ensure it is free of endogenous ligand. The ligand is typically conjugated to a fluorescent probe like 8-NBD-cAMP.

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a stopped-flow apparatus (e.g., SFM-400) with a microcuvette and a dead time of approximately 325 μs. Set appropriate excitation and emission filters.

- Data Collection: Mix protein and ligand solutions at a 1:1 ratio under pseudo-first-order conditions (where [L]â‚€ >> [P]â‚€). Monitor the fluorescence change over time.

- Data Analysis: Fit the fluorescence traces to the solution of the bimolecular rate equation to extract the apparent rate constants ((k{app})). Derive the association ((k{on})) and dissociation ((k{off})) rate constants from experiments at multiple ligand concentrations. Perform competition experiments with non-fluorescent ligands to directly determine (k{off}) [8].

Energetics-Based Target Identification via Pulse Proteolysis

This method leverages the increase in thermodynamic stability upon ligand binding to identify protein targets in complex mixtures like cell lysates [11].

- Protocol:

- Incubation with Ligand: Incubate a cell lysate (e.g., from E. coli) with and without the test ligand (e.g., ATPγS) in a buffer containing a denaturant like urea (e.g., 3.0 M).

- Pulse Proteolysis: Subject both samples to a brief, controlled proteolysis (e.g., 0.20 mg/mL thermolysin for 1 minute). The stabilized, folded proteins will be resistant to digestion.

- Analysis: Analyze the remaining proteins by 2D gel electrophoresis. Identify protein spots whose intensity is consistently higher in the ligand-treated sample compared to the control.

- Validation: Identify the stabilized proteins using mass spectrometry (e.g., MALDI-TOF-TOF) and validate binding through independent assays [11].

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS)

HDX-MS measures the exchange rate of backbone amide hydrogens with deuterium in the solvent. A slowed exchange rate in specific regions upon ligand binding indicates stabilization and often a conformational change.

- Protocol:

- Labeling: Dilute the apo and ligand-bound protein into a deuterated buffer for a defined period.

- Quenching: Lower the pH and temperature to quench the exchange reaction.

- Digestion and Analysis: Digest the protein with pepsin and analyze the peptide fragments using mass spectrometry to determine the deuteration level of each peptide.

- Mapping: Map the peptides with reduced deuteration in the ligand-bound state onto the protein structure to identify the regions involved in the conformational change.

Computational and Simulation Approaches

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an atomistic view of conformational dynamics, complementing experimental observations.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations with Enhanced Sampling

Conventional MD simulations may not sufficiently sample rare conformational transitions. Enhanced sampling methods are critical for studying Induced Fit events [9] [10].

- Protocol:

- System Preparation: Obtain a starting structure (from crystallography or homology modeling). Dock the ligand if necessary. Solvate the protein-ligand system in a water box and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Enhanced Sampling: Run simulations using methods like accelerated MD (aMD) or metadynamics. These methods reduce the energy barriers between states, allowing the system to explore its conformational landscape more efficiently.

- Ensemble Generation and Analysis: Generate ensembles of structures for both the apo and ligand-bound states. Use clustering algorithms and dimensionality reduction techniques (like Principal Component Analysis) to identify dominant conformational states. Analyze how the population of these states shifts upon ligand binding [9] [10]. For example, studies on nuclear receptors showed that agonist binding shifted the conformational ensemble toward active states characterized by the stable positioning of helix 12 [10].

Advanced Analysis with Tools like gmx_RRCS

Specialized analysis tools have been developed to detect subtle conformational changes that standard metrics like Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) might miss. The gmx_RRCS tool quantifies interaction strengths between residues by analyzing residue-residue contact scores (RRCS) throughout a simulation trajectory [12].

- Application: This tool can reveal subtle sidechain reorientations and the dynamics of salt bridges or hydrophobic packing that are crucial for the Induced Fit mechanism. It has been applied to systems like PI3Kα to distinguish conformational states of oncogenic mutants [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Studying Induced Fit

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Apparatus | Allows rapid mixing (dead-times < 1 ms) and monitoring of fast binding kinetics via fluorescence or absorbance. |

| Fluorescent Ligand Analogs | Enable direct observation of binding events; e.g., 8-NBD-cAMP for studying cyclic nucleotide-binding domains. |

| Thermolysin | A robust protease used in pulse proteolysis experiments to distinguish stabilized (ligand-bound) from destabilized proteins. |

| Urea / Guanidine HCl | Chaotropic denaturants used to create a stability challenge in pulse proteolysis or equilibrium unfolding assays. |

| Allosteric Mutants | Engineered protein variants used to perturb the conformational equilibrium and dissect the kinetic mechanism. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software like NAMD or GROMACS for running MD simulations to visualize and quantify conformational trajectories. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins | Tools like PLUMED or built-in methods (aMD, metadynamics) to overcome sampling limitations in MD. |

| Ezh2-IN-14 | Ezh2-IN-14, MF:C31H39N7O2, MW:541.7 g/mol |

| Hdac10-IN-2 | Hdac10-IN-2, MF:C19H22N2O2, MW:310.4 g/mol |

Biological Case Studies

Nuclear Receptors

Nuclear receptors are classic models for studying ligand-induced conformational changes. They function as ligand-regulated transcription factors. Research on an ancestral steroid receptor demonstrated that different ligands shift the conformational ensemble of the receptor in distinct ways [9] [10]. Using accelerated MD simulations, it was observed that agonist ligands shift the ensemble population toward the active state, where the C-terminal helix (H12) is positioned to form a docking site for coactivator proteins. The degree of this population shift correlated directly with the ligand's transcriptional efficacy, providing a quantitative link between an Induced Fit-like ensemble shift and biological function [10].

Ion Channels: Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

MD simulations of the α7 nicotinic receptor ligand-binding domain revealed how different ligands induce distinct conformational states. Simulations with the agonist acetylcholine (ACh) promoted a more open and symmetric arrangement of the five subunits, particularly in the lower portion of the domain near the channel gate. In contrast, simulations without ligand or with the antagonist d-tubocurarine resulted in a more closed and asymmetric arrangement. This demonstrated how an agonist-induced change in the binding domain could be transmitted to the transmembrane gate, a hallmark of Induced Fit signaling [13].

Enzymes: Caffeoyl coenzyme A O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT)

Comparative MD simulations of the enzyme CCoAOMT in its apo and substrate-bound forms revealed a significant conformational switch. Upon binding its substrate (CCoA), the enzyme's structure became more compact, and the substrate transport channel transitioned from an open to a closed state. This ligand-induced closure, trapping the substrate in the active site, is a clear example of an Induced Fit mechanism that is critical for the enzyme's function in lignin biosynthesis [14].

Implications for Drug Discovery

Understanding Induced Fit is critical in rational drug design. The conformational changes induced by a ligand can influence:

- Drug Specificity: A drug can be designed to preferentially bind to and stabilize a specific protein conformation that is unique to a target, reducing off-target effects.

- Allosteric Modulator Design: Allosteric drugs often work by inducing conformational changes that either enhance or inhibit the protein's activity. The principles of Induced Fit guide the design of such molecules.

- Membrane Protein Drug Design: For membrane proteins, where many drug binding sites are embedded in the lipid bilayer, the ligand's properties must facilitate partitioning into the membrane and then induce the desired conformational change at the protein-lipid interface [15]. Ligands for these sites often have distinct chemical properties, such as higher lipophilicity (clogP) and molecular weight [15].

The Induced Fit hypothesis remains a vital and powerful model for explaining how proteins dynamically respond to their chemical environment. While the simple dichotomy between Induced Fit and Conformational Selection is evolving, the core concept that ligand binding can actively reshape a protein's structure is undeniable. Modern research, leveraging advanced kinetic experiments, energetics-based profiling, and sophisticated computational simulations, has deconstructed the hypothesis to reveal a complex reality where proteins exist as dynamic conformational ensembles. Within this framework, ligand binding often acts to shift the equilibrium of these pre-existing ensembles, stabilizing a specific functional state—a process that kinetically manifests as Induced Fit [9] [10] [5].

This refined understanding provides a more powerful and predictive framework for molecular recognition. For researchers and drug developers, the ability to not only visualize but also quantitatively predict how a ligand will alter a protein's conformational landscape is invaluable. It enables the rational design of synthetic modulators with precise efficacy and specificity, ultimately illuminating the path to targeting therapeutically relevant proteins with unprecedented control.

The conformational selection model represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of molecular recognition, challenging the long-held view that proteins exist as single, static structures awaiting ligand binding. This model posits that proteins inherently sample a diverse ensemble of conformational states even in their unliganded form, and ligands selectively bind to and stabilize pre-existing conformations that complement their binding interface [16] [17]. This framework stands in contrast to the induced fit hypothesis, which asserts that conformational changes occur only after initial ligand contact, effectively "inducing" the protein to adopt a complementary shape [16] [18].

Historically, induced fit and conformational selection were regarded as mutually exclusive mechanisms [19]. However, contemporary research reveals this to be a "false dichotomy" [19]. These mechanisms are now understood to operate alongside one another within a thermodynamic cycle, with their relative contributions determined by specific kinetic parameters and ligand concentration [19] [20]. The conformational selection model is grounded in the energy landscape theory of protein dynamics, which describes proteins as navigating a complex topography of conformational substates through thermal fluctuations [16]. From this perspective, ligand binding does not create new structures but rather causes a population shift in the equilibrium distribution of pre-existing conformations [16].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the conformational selection model, detailing its theoretical foundations, experimental validation, and significant implications for drug discovery and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Framework and Fundamental Principles

Core Mechanism and Temporal Ordering

The defining characteristic of conformational selection is the temporal ordering of molecular events: a conformational change precedes the binding event [20]. In this mechanism, an unbound protein transiently samples a higher-energy, excited-state conformation through thermal fluctuations. A ligand then selectively binds to this rare conformation, which structurally resembles the final bound state.

The reverse process follows an induced-change pathway: during unbinding, the conformational change occurs after the ligand dissociates [20]. This relationship illustrates that conformational selection and induced fit are "two sides of the same coin," differentiated by the sequence of chemical and physical steps in binding versus unbinding directions [20].

The Energy Landscape Perspective

The conformational selection model finds its foundation in the energy landscape theory of protein structure and dynamics [16]. A protein's free energy landscape comprises numerous conformational substates in dynamic equilibrium. Rather than residing in a single rigid structure, proteins exist as statistical ensembles of interconverting conformations [16].

- Pre-existing Conformations: Conformations observed in ligand-bound complexes fundamentally pre-exist within the ensemble sampled by the unliganded protein [16]. Binding does not create novel structures but selects and stabilizes functionally competent conformations that already occur, albeit potentially with low probability, in the absence of ligand.

- Population Shift: Ligand binding alters the thermodynamic equilibrium between conformational states. The bound conformation becomes more populated, while other conformations decrease in abundance [16]. This redistribution occurs without changing the inherent structural repertoire of the protein.

- Barrier Crossing: Transitions between conformational states involve crossing free-energy barriers. The actual "transition time" for crossing these barriers is significantly shorter than the dwell times in stable states, making conformational changes appear as sudden jumps in experimental observations [20].

Quantitative Kinetic and Thermodynamic Basis

The thermodynamic cycle for conformational selection can be represented through discrete states and transitions, characterized by specific kinetic rate constants that dictate which recognition pathway dominates under given conditions [19] [16].

Table 1: Key Rate Constants in the Conformational Selection Model

| Rate Constant | Description | Role in Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| k1,CS | Conformational transition from unbound ground state (P1) to unbound excited state (P2) | Determines spontaneous population of bind-competent state |

| k-1,CS | Reverse conformational transition (P2 to P1) | Competes with binding from P2 state |

| k2,CS | Ligand binding to pre-existing conformation P2 | Bimolecular step forming final complex |

| k-2,CS | Ligand dissociation from P2L complex | Determines complex stability |

The diagram below illustrates the conformational selection pathway and its relationship with induced fit within a complete thermodynamic cycle:

Figure 1: Thermodynamic cycle of conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms. The conformational selection pathway (blue) involves a conformational change preceding binding, while induced fit (green) involves binding followed by conformational adjustment.

A critical insight from recent studies is that the relative contribution of induced fit increases with ligand concentration [19]. At low ligand concentrations, conformational selection typically dominates, as the rare, bind-competent conformations are sufficient to accommodate limited ligand molecules. At high concentrations, induced fit becomes more significant as ligands initially bind with lower affinity to more abundant conformations, subsequently inducing conformational changes. This concentration-dependent interplay underscores why these mechanisms are no longer considered mutually exclusive [19].

Experimental Evidence and Validation

Key Experimental Methodologies

Multiple advanced experimental techniques have been crucial in validating the conformational selection model by detecting and characterizing the pre-existing conformational ensembles of proteins.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Studying Conformational Selection

| Method | Key Principle | Information Obtained | Applications & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Measures chemical shift perturbations and dynamics on μs-ms timescales | Detects low-population excited states; determines kinetic rates of conformational exchange | Ubiquitin conformational ensembles [16] [17]; Ribonuclease A; Dihydrofolate reductase [16] |

| Relaxation Dispersion NMR | Analyzes R₂ relaxation rates to characterize μs-ms exchange processes | Quantifies populations, chemical shifts, and kinetics of invisible excited states | Adenylate kinase open/closed states [16] |

| Single-Molecule FRET | Measures distance changes via energy transfer between fluorophores | Observes real-time transitions between conformational states | Protein folding/unfolding dynamics; Conformational heterogeneity [20] [16] |

| Residual Dipolar Coupling (RDC) | Measures residual anisotropic interactions in weakly aligned molecules | Provides structural restraints for characterizing conformational ensembles | Ubiquitin solution structures matching bound conformations [17] |

| Chemical Relaxation | Probes kinetics of system relaxation to equilibrium after perturbation | Determines dominant relaxation rate kobs and its ligand concentration dependence | Distinguishing CS vs. IF mechanisms [21] |

| Computational Solvent Mapping | Computationally docks small probe molecules to protein surfaces | Identifies binding hot spots and pre-formed binding sites in unbound ensembles | Binding site formation in protein-protein interfaces [22] |

Critical Experimental Findings

Evidence supporting conformational selection has emerged across diverse biological systems:

Antibody-Antigen Recognition: Studies of the SPE7 antibody demonstrated that a single antibody molecule can exist in multiple pre-existing conformations capable of binding distinct antigens [17] [23]. Crystallographic analyses revealed different conformations in the absence of antigen, with each conformation specialized for binding particular antigenic structures [16].

Ubiquitin Signaling: Groundbreaking NMR studies compared ensembles of free ubiquitin structures with ubiquitin bound to various target proteins [17]. For each bound ubiquitin structure, the unbound ensemble contained members with remarkable structural similarity, strongly supporting conformational selection as the primary recognition mechanism [17] [22].

Enzyme Catalysis: Numerous enzymes previously classified as induced-fit systems, including adenylate kinase, ribonuclease A, and dihydrofolate reductase, have been re-evaluated through relaxation dispersion NMR [16]. These studies revealed conformational exchange between ground and excited states on microsecond-to-millisecond timescales, with excited states matching ligand-bound conformations [16].

Distinguishing Conformational Selection from Induced Fit

A critical advancement in the field has been the development of methodologies to quantitatively distinguish conformational selection from induced fit based on chemical relaxation rates [21]. The characteristic dependence of the dominant relaxation rate (kobs) on ligand concentration provides a key diagnostic tool:

Figure 2: Characteristic dependence of observed relaxation rate (kobs) on ligand concentration for conformational selection versus induced fit mechanisms.

Under pseudo-first-order conditions (high ligand concentration), conformational selection typically exhibits a decreasing kobs with increasing [L] when the conformational excitation rate ke is lower than the unbinding rate k- [21]. Induced fit consistently shows an increasing kobs with [L] under these conditions. However, distinction becomes unambiguous only when considering a broader range of protein and ligand concentrations beyond pseudo-first-order conditions [21].

Computational Approaches and Modern Methodologies

Contemporary research into conformational selection employs an integrated suite of experimental and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Conformational Selection Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectrometer | Instrumentation | Detects atomic-level structure and dynamics | Measures chemical shifts, relaxation rates, residual dipolar couplings |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules | Captures conformational transitions; Examples: GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, CHARMM [24] |

| ATLAS Database | Database | Stores molecular dynamics trajectories | ~2000 representative proteins; 5841 trajectories [24] |

| GPCRmd Database | Database | Specialized MD database for GPCR proteins | 705 simulations; 2115 trajectories [24] |

| FiveFold Methodology | Computational Method | Ensemble-based structure prediction | Combines 5 algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, etc.) [25] |

| Computational Solvent Mapping | Computational Method | Identifies binding hot spots | Uses small molecular probes to map binding sites [22] |

Advanced Computational Modeling

The emergence of artificial intelligence has revolutionized protein structure prediction, with methods like AlphaFold achieving remarkable accuracy for static structures [24] [25]. However, these methods face challenges in capturing the intrinsic conformational diversity essential for biological function. Several innovative approaches have been developed to address this limitation:

Ensemble-Based Prediction Methods: The FiveFold methodology represents a paradigm-shifting advancement that combines predictions from five complementary algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D) to model conformational diversity [25]. This approach explicitly acknowledges and models the inherent conformational heterogeneity of proteins through its Protein Folding Shape Code and Protein Folding Variation Matrix systems [25].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: MD simulations directly simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing atomic-level insights into conformational transitions [24]. Specialized databases such as ATLAS and GPCRmd collect and curate MD simulation data, making conformational dynamics data accessible to the research community [24].

Generative Models: Recent advances include diffusion and flow matching models that can predict equilibrium distributions of molecular systems, enabling sampling of diverse and functionally relevant structures [24]. These approaches show promise in overcoming limitations of traditional structure prediction methods.

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Expanding the Druggable Proteome

The conformational selection paradigm has profound implications for drug discovery, particularly for targeting proteins traditionally considered "undruggable." Approximately 80% of human proteins fall into this category when using conventional structure-based drug design approaches [25]. Many challenging targets, including transcription factors, protein-protein interaction interfaces, and intrinsically disordered proteins, require therapeutic strategies that account for conformational flexibility and transient binding sites [25].

Ensemble-based structure prediction methods like FiveFold show particular promise in expanding the druggable proteome by modeling multiple conformational states simultaneously [25]. This capability enables the identification of cryptic binding pockets and transient binding sites that may not be apparent in single, static structures [25] [22].

Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), which comprise approximately 30-40% of the human proteome, represent a particularly compelling application for conformational selection principles [25]. IDPs lack stable tertiary structure under physiological conditions yet play crucial roles in cellular regulation and disease pathways [25].

These proteins often contain Molecular Recognition Features (MoRFs) - short regions that undergo disorder-to-order transitions upon binding [23]. The conformational selection model provides a framework for understanding how these flexible regions sample bound-like conformations even in their unbound state, enabling highly specific binding interactions despite their inherent flexibility [23].

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Optimization of Therapeutics

Understanding the conformational selection mechanism enables more rational optimization of drug binding kinetics and residence times, which are increasingly recognized as critical determinants of in vivo drug efficacy [19]. Drugs with longer residence times often demonstrate superior target selectivity and duration of action [19].

The flux-based analysis approach reveals that a limited set of "microscopic" rate constants regulate the relative contributions of conformational selection and induced fit across different ligand concentrations [19]. This insight allows medicinal chemists to deliberately design compounds that preferentially utilize specific binding pathways optimized for therapeutic effect.

The conformational selection model represents a fundamental advancement in our understanding of molecular recognition, displacing the historical view of proteins as static entities with a dynamic perspective of proteins as conformational ensembles. This paradigm shift from structure to ensemble has far-reaching implications for basic biological research and therapeutic development.

Rather than operating in isolation, conformational selection and induced fit function as complementary mechanisms within a unified thermodynamic framework [19] [20]. Their relative contributions are governed by specific kinetic parameters and ligand concentrations, explaining why both mechanisms are observed across different experimental systems and conditions [19].

The ongoing integration of advanced experimental techniques with sophisticated computational approaches continues to reveal the intricate relationship between conformational dynamics and biological function. As ensemble-based drug discovery strategies mature, they hold significant promise for addressing currently intractable therapeutic targets and advancing precision medicine. The conformational selection model thus represents not merely a theoretical concept but a practical framework with transformative potential for biomedical research and drug development.

The binding of a ligand to its biological target is a fundamental process in biochemistry, central to drug design and therapeutic development. The affinity of this interaction is quantifiably expressed by the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔG, which represents the thermodynamic driving force for binding. As defined by the fundamental equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, the binding free energy is partitioned into two components: the enthalpic change (ΔH), which reflects the heat released or absorbed during bond formation and breaking, and the entropic change (-TΔS), which represents the change in system disorder, encompassing conformational, solvation, and rotational degrees of freedom [26].

A phenomenon frequently observed in ligand-binding studies is enthalpy-entropy compensation (EEC). This occurs when a modification to a ligand or protein results in a favorable change in one thermodynamic component (e.g., a more negative ΔH) that is partially or fully offset by an unfavorable change in the other (e.g., a more negative TΔS). In its most severe form, this leads to no net change in binding affinity (ΔΔG ≈ 0) despite significant underlying thermodynamic perturbations, posing a substantial challenge for rational ligand optimization in drug discovery [26]. This whitepaper explores the evidence for EEC, its physical origins, and its critical interrelationship with the mechanisms of molecular recognition—conformational selection and induced fit—framed for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Phenomenon of Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation

Defining Compensation

In the context of ligand binding, enthalpy-entropy compensation generally describes a situation where a ligand modification produces a change in the enthalpic contribution to binding (ΔΔH), which is opposed by a corresponding change in the entropic contribution (TΔΔS). For a strong, nearly complete compensation where the net change in binding affinity is minimal, the relationship ΔΔH ≈ TΔΔS holds true [26]. Evidence for EEC is often presented graphically, with TΔS plotted against ΔH for a series of related ligands or systems; a linear regression with a slope near unity is frequently interpreted as signature of compensation [26].

Experimental Evidence and Calorimetric Insights

The widespread adoption of isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) has provided a rich dataset of binding thermodynamics, fueling the observation of EEC. ITC simultaneously measures the equilibrium constant ((K_a)) and the enthalpy change (ΔH) in a single experiment, allowing for the direct calculation of ΔG and TΔS [26].

Numerous ITC studies have reported apparent EEC. A meta-analysis of approximately 100 protein-ligand complexes from the BindingDB database concluded that a plot of ΔH versus TΔS showed a slope of nearly unity, suggesting a pervasive form of severe compensation [26]. Specific case studies further illustrate this:

- HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors: Introducing a hydrogen bond acceptor into an inhibitor resulted in a substantial enthalpic gain of 3.9 kcal/mol. However, this was entirely offset by an entropic penalty of similar magnitude, resulting in no net improvement in affinity. This was interpreted as the entropic cost of structuring associated with hydrogen bond formation [26].

- Trypsin Inhibitors: A study of para-substituted benzamidinium inhibitors of trypsin found that nearly all ligands in the series exhibited EEC, with the free energy of binding remaining almost constant despite large variations in ΔH and TΔS [26].

- Thrombin Ligands: Studies on congeneric series of thrombin ligands indicated that chemical modifications could lead to competing entropic and enthalpic responses, creating apparent non-additive effects [26].

Table 1: Documented Cases of Apparent Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation

| Protein Target | Ligand Modification | Observed ΔΔH | Observed TΔΔS | Net ΔΔG | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease | Introduction of H-bond acceptor | ~ -3.9 kcal/mol | ~ -3.9 kcal/mol | ~ 0 kcal/mol | [26] |

| Trypsin | para-substitution of benzamidinium | Large variation | Opposing variation | Minimal change | [26] |

| Thrombin | Congeneric series modifications | Competing changes | Competing changes | Non-additive | [26] |

The Conformational Selection vs. Induced Fit Paradigm

The mechanism by which a ligand and its protein target recognize each other is intrinsically linked to the observed binding thermodynamics. The two dominant, historically competing models are induced fit and conformational selection [1].

The Induced Fit Model

This model posits that the binding partner, often the protein, is initially in a conformation that does not perfectly complement the ligand. The binding event itself induces a conformational change in the protein to achieve optimal fit and binding [1] [27]. This model aligns with the traditional view where binding precedes structural adjustment.

The Conformational Selection Model

This model proposes that the unliganded protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium of multiple conformations. The ligand does not induce a new shape but rather selects and binds preferentially to a pre-existing, complementary conformation. This binding event shifts the population equilibrium toward the selected state [1] [27].

An Integrated View: The Extended Conformational Selection Model

Modern understanding, supported by single-molecule studies and NMR, reveals that the distinction between these models is not absolute. An extended conformational selection model has been proposed, which embraces a repertoire of selection and adjustment processes [1]. In this integrated view, binding often begins with conformational selection of a roughly compatible state, which is then followed by local induced-fit adjustments to optimize the interaction. The lock-and-key, induced fit, and pure conformational selection models can all be seen as special cases of this broader repertoire [1]. Recent research on the calreticulin family of proteins, for instance, demonstrated a mixed mechanism initially driven by conformational selection, followed by glycan-induced fluctuations in key residues to strengthen binding [6].

Diagram 1: An integrated binding mechanism showing initial conformational selection from a dynamic ensemble, followed by a final induced-fit adjustment.

Interplay Between Recognition Mechanisms and Thermodynamics

The chosen molecular recognition pathway has profound and distinguishable implications for the observed thermodynamics and kinetics of binding, which in turn influence EEC.

Kinetic Signatures and the Pitfalls of Interpretation

A classic method for distinguishing between induced fit and conformational selection relies on analyzing the observed rate constant for binding ((k_{obs})) as a function of ligand concentration ([L]) [27].

- Induced Fit Prediction: (k_{obs}) increases with [L], eventually plateauing at high concentrations.

- Conformational Selection Prediction: (k_{obs}) decreases with [L], eventually reaching a lower limit at high concentrations.

However, this diagnostic, based on the rapid-equilibrium approximation, is not universally reliable. A more rigorous kinetic analysis reveals that conformational selection can exhibit a rich repertoire of kinetic properties. While a decrease in (k{obs}) with [L] remains unequivocal evidence for conformational selection, an increase in (k{obs}) with [L] is not unequivocal evidence for induced-fit and can, under certain conditions, also be consistent with conformational selection [27]. This complexity suggests that conformational selection may be a far more common mechanism than previously assumed.

Thermodynamic Footprints and Compensation

The recognition mechanism directly dictates the thermodynamic "price" paid upon binding.

- Induced Fit is typically associated with a significant entropic penalty.

- Conformational Selection also incurs an entropic cost, known as a "conformational entropy penalty".

- Solvent Reorganization: Both mechanisms involve changes in solvent structure. The release of ordered water molecules from hydrophobic surfaces into the bulk solvent is a classic example of an entropic gain that can drive binding, while the formation of new hydrogen bonds can be enthalpically favorable but entropically costly if they restrict motion.

The phenomenon of EEC often arises from the intricate balance between these factors. For example, a ligand engineered to form an additional hydrogen bond (a favorable enthalpic change, ΔΔH < 0) may rigidify the protein structure or restrict water motion, leading to a loss of entropy (unfavorable entropic change, TΔΔS < 0). If the system operates under a paradigm where conformational flexibility is key, this entropic penalty can be substantial, leading to compensation. The mixed mechanism revealed in the calreticulin family suggests a hierarchical contribution to this balance, where the initial selection step governs the major thermodynamic signature, which is then fine-tuned by subsequent adjustments [6].

Experimental Protocols for Probing Thermodynamics and Mechanism

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Protocol

ITC is the gold standard for directly measuring the thermodynamic parameters of binding.

- Objective: To directly determine the binding affinity ((K_d)), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy change (ΔH), and by calculation, the free energy change (ΔG) and entropic change (TΔS).

- Methodology:

- The protein solution is loaded into the sample cell of the calorimeter.

- The ligand solution is loaded into the injection syringe.

- The instrument performs a series of automated injections of the ligand into the protein cell.

- After each injection, the instrument measures the minute amount of heat released or absorbed to maintain thermal equilibrium between the sample and reference cells.

- The raw data is a plot of power (μcal/s) versus time (min).

- Data Analysis:

- The integrated heat from each injection is plotted against the molar ratio of ligand to protein.

- This isotherm is fit to a suitable binding model.

- The fit directly yields n, (Ka) (1/(Kd)), and ΔH.

- ΔG is calculated as (\Delta G = -RT \ln(K_a)).

- TΔS is calculated from the relationship (T\Delta S = \Delta H - \Delta G) [26].

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Kinetics Protocol

This technique is used to probe the kinetics and mechanism of binding, complementing the thermodynamic data from ITC.

- Objective: To measure the observed rate constant ((k_{obs})) of binding as a function of ligand concentration ([L]) to distinguish between potential binding mechanisms.

- Methodology:

- One syringe is filled with the protein solution, and another with the ligand solution.

- The solutions are rapidly pushed into a mixing chamber and then into an observation cell, achieving complete mixing in milliseconds.

- The fluorescence of a tryptophan residue (intrinsic) or an added fluorescent probe, which changes upon binding, is monitored over time.

- The experiment is repeated at multiple ligand concentrations.

- Data Analysis:

- Each fluorescence trace is fit to a single or multi-exponential equation to extract the (k{obs}).

- The values of (k{obs}) are then plotted against the corresponding [L].

- The shape of this plot (increasing, decreasing, or more complex) is analyzed using the full kinetic equations for multi-step mechanisms (e.g., Schemes 2 and 3 from [27]) to infer the underlying mechanism, moving beyond the rapid-equilibrium approximation.

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Studying Binding Thermodynamics and Mechanisms

| Technique | Primary Measured Output(s) | Derived Information | Utility for Studying EEC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | (K_a), ΔH, n | ΔG, TΔS | Directly measures the enthalpic and entropic components for a full thermodynamic profile. Essential for observing EEC. |

| Stopped-Flow Fluorescence | (k_{obs}) vs. [L] | Kinetic mechanism (Conformational Selection vs. Induced Fit) | Provides mechanistic context for observed thermodynamic compensation. |

| Van't Hoff Analysis | (K_a) at multiple temperatures | ΔH, ΔS, Δcₚ | Provides an alternative, indirect route to ΔH and ΔS. Can reveal the heat capacity change. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Atomic-level trajectories of motion | Conformational ensembles, dynamics, interaction energies | Offers atomistic insight into the structural origins of entropic penalties and enthalpic gains, e.g., as in [6]. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Ligand Engineering

The prevalence of EEC, particularly its severe form, poses a significant challenge in rational drug design.

- The Frustration of Optimization: Efforts to improve affinity by introducing groups to form strong, enthalpically favorable interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, salt bridges) can be thwarted if they introduce conformational rigidity or alter solvation in a way that produces a compensatory entropic penalty [26]. Conversely, strategies to reduce entropic penalties by pre-organizing the ligand can result in enthalpic penalties if the rigidified ligand cannot perfectly adapt to the binding site.

- A Shift in Design Strategy: Given the difficulty of predicting or measuring entropic and enthalpic changes with useful precision, and the prevalence of compensation, a pragmatic approach is to focus ligand engineering efforts on computational and experimental methodologies that directly assess changes in binding free energy (ΔG) [26]. While understanding the thermodynamic partitioning is insightful, the primary goal should be net affinity improvement.

- Leveraging Mechanism: Understanding whether a system follows conformational selection or induced fit can inform design. For a system dominated by conformational selection, designing ligands that better complement the shape and chemistry of the rarely populated, high-affinity conformation could be a powerful strategy. The mixed mechanism suggests that ligands should be designed not only for optimal fit to a selected state but also with flexibility to accommodate subsequent fine-tuning adjustments [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Purity, Well-Characterized Protein | The protein target must be highly pure and monodisperse. Stability and the absence of aggregates are critical for obtaining reliable ITC and kinetic data. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | The primary instrument for directly measuring binding thermodynamics. It provides a complete dataset (Ka, ΔH, n) from a single experiment. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrofluorimeter | An essential instrument for rapid kinetics studies. It allows the measurement of binding rates on millisecond timescales, which is crucial for mechanistic discrimination. |

| Congeneric Ligand Series | A series of structurally related ligands with systematic modifications is fundamental for probing structure-thermodynamic relationships and observing EEC. |

| High-Affinity Binding Site Probe (e.g., PABA for serine proteases) | A fluorescent probe like p-aminobenzamidine (PABA), which exhibits a strong fluorescence signal sensitive to its binding environment, is invaluable for stopped-flow binding studies [27]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Software like GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD allows researchers to simulate the dynamic behavior of proteins and ligands, providing atomistic insights into conformational ensembles and binding pathways [6]. |

| Eleven-Nineteen-Leukemia Protein IN-3 | ENL Inhibitor: Eleven-Nineteen-Leukemia Protein IN-3 |

| Atr-IN-22 | Atr-IN-22, MF:C25H31N7O, MW:445.6 g/mol |

Molecular recognition, the fundamental process by which biological molecules interact specifically and transiently with their partners, serves as the cornerstone of nearly all biological processes, including enzymatic catalysis, immune recognition, cellular signaling, and genomic regulation. The physical basis for these precise interactions lies primarily in the realm of non-covalent chemistry—specifically, the coordinated action of hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects. These interactions, while individually weak compared to covalent bonds, collectively confer the specificity, directionality, and reversibility essential to biological function [28] [29].

For decades, two competing paradigms have sought to explain the mechanism of molecular recognition: induced fit and conformational selection. The induced fit model, introduced by Koshland, posits that the ligand first binds to its target, subsequently inducing the conformational change necessary for optimal complementarity. In contrast, the conformational selection model suggests that the target protein exists in an equilibrium of conformations, with the ligand selectively binding to and stabilizing a pre-existing complementary state [27] [30]. Historically, these were viewed as mutually exclusive mechanisms, but a growing body of evidence now reveals that they are often intertwined, with many systems employing a hybrid approach where conformational selection provides the initial recognition and induced fit refines the binding interface [31] [6] [3].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the three primary non-covalent interactions, their quantitative energetics, and their integrated roles in molecular recognition mechanisms. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, it also synthesizes current experimental approaches for distinguishing binding mechanisms and explores the critical implications for rational drug design.

Fundamental Non-Covalent Interactions

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonds are a specific type of electrostatic interaction involving a partially positive hydrogen atom bound to a highly electronegative donor (most commonly oxygen or nitrogen) and a partially negative acceptor atom, typically oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine [28]. While not covalent bonds, they represent one of the strongest non-covalent interactions, with energies typically ranging from 10–40 kJ/mol, and in some specific contexts, can be as strong as 40 kcal/mol (∼167 kJ/mol) [28]. The strength of a hydrogen bond is primarily determined by electrostatic factors, making it highly directional and dependent on the geometry of the participating atoms [28].

In biological systems, hydrogen bonds are indispensable for maintaining the three-dimensional structure of proteins and nucleic acids. They are responsible for the stability of the DNA double helix through base pairing and form the backbone of secondary structural elements in proteins, such as α-helices and β-sheets [28] [29]. In molecular recognition, hydrogen bonds provide fine-tuning for specificity, as seen in the precise interactions between enzymes and their substrates or antibodies and their antigens [29].

Van der Waals Forces

Van der Waals forces are a subset of electrostatic interactions involving permanent or induced dipoles. They encompass three distinct types of interactions [28]:

- Keesom forces: Interactions between two permanent dipoles.

- Debye forces: Interactions between a permanent dipole and an induced dipole.

- London dispersion forces: Interactions between two instantaneously induced dipoles.

London dispersion forces, the weakest among non-covalent interactions (0.4–4 kJ/mol), are also the most universal, present between all atoms and molecules [28] [29]. Despite their individual weakness, the cumulative effect of numerous van der Waals contacts across a molecular interface can contribute significantly to binding affinity and specificity. These forces are highly dependent on the polarizability of the interacting atoms and the distance between them, following a 1/rⶠdependence [28]. In drug-protein interactions, van der Waals forces are often the initial driving force that allows a drug molecule to enter a hydrophobic pocket [29].

Hydrophobic Effects

The hydrophobic effect describes the tendency of non-polar molecules or molecular surfaces to aggregate in an aqueous environment to minimize their contact with water molecules. This phenomenon is not driven by an attractive force between the non-polar species but rather by the entropic gain of the surrounding water molecules. When a hydrophobic solute is immersed in water, the water molecules form a more ordered "cage" or clathrate structure around it, resulting in a decrease in entropy. The aggregation of hydrophobic groups reduces the total surface area exposed to water, thereby minimizing the entropic penalty [32].

The hydrophobic effect is a major driving force in biological processes such as protein folding, membrane formation, and the stabilization of protein complexes [32] [29]. Its strength is context-dependent, with hydration free energy scaling with the volume of small solutes but with the surface area of large solutes, exhibiting a crossover on the nanometer length scale [32]. The classic view of hydrophobic interactions as purely entropy-driven is being revised, as some systems show that complexation can be enthalpy-driven at room temperature, attributed to the release of poorly hydrogen-bonded water molecules from the interface into the bulk solvent [32].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Non-Covalent Interactions

| Interaction Type | Energy Range (kJ/mol) | Distance Dependence | Key Features & Biological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | 10 - 40 (up to ~167 in specific cases) | ~1/r³ | Directional; fine-tunes specificity in enzyme-substrate and antigen-antibody binding. |

| Van der Waals Forces | 0.4 - 4 | ~1/rⶠ| Universal, weak, and additive; crucial for molecular packing and drug binding. |

| Hydrophobic Effect | 10 - 40 | N/A (Collective Phenomenon) | Entropically driven; key for protein folding, membrane formation, and molecular aggregation. |

Conformational Selection vs. Induced Fit: A Kinetic and Structural Perspective

Kinetic Distinctions Between the Mechanisms

The induced fit and conformational selection mechanisms can be distinguished through detailed kinetic analysis, particularly by observing the dependence of the observed rate constant ((k_{obs})) on ligand concentration ([L]) [27] [30].

Induced Fit Mechanism: In this model, the ligand (L) first binds to the protein's ground state (E) to form an encounter complex (E:L), which then undergoes a conformational change to the final bound state (E:L). The (k_{obs}) for this mechanism increases hyperbolically with [L], approaching a maximum limit at saturating ligand concentrations. The reaction can be simplified as: ( E + L \rightleftharpoons E:L \rightarrow E:L )

Conformational Selection Mechanism: Here, the protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium between at least two conformations (E and E), with only one (E) being competent for binding. The ligand selectively binds to this pre-existing, minor population. The (k_{obs}) for this mechanism decreases hyperbolically with increasing [L]. The reaction pathway is: ( E \rightleftharpoons E* + L \rightleftharpoons E*:L )

A critical advancement in this field is the recognition that a hyperbolic increase in (k{obs}) with [L] can be consistent with *both* models. However, a definitive diagnosis of conformational selection is possible when (k{obs}) decreases with increasing ligand concentration. Conversely, while an increase in (k_{obs}) suggests induced fit, it is not conclusive proof on its own [27] [30].

Diagram 1: Distinguishing binding mechanisms by kinetics.

The Emergence of Hybrid Mechanisms

Advanced analytical techniques, particularly NMR and molecular dynamics simulations, have revealed that a strict dichotomy between conformational selection and induced fit is often an oversimplification. For many systems, a hybrid mechanism is operative [6] [3].

A seminal study on the LAO binding protein used Markov State Models (MSMs) built from atomistic simulations to dissect its binding mechanism. The research identified an intermediate encounter complex state, where the protein is partially closed and only weakly interacts with the substrate. The simulations showed that the ligand-free protein could spontaneously sample this partially closed state, demonstrating conformational selection. However, the transition from this encounter complex to the fully closed, bound state was driven by interactions with the ligand, a clear example of induced fit [3].

Similarly, an extensive structural analysis of ubiquitin binding demonstrated that conformational selection and induced fit work sequentially. The unbound ubiquitin samples conformational states that are globally similar to its various bound forms, supporting a conformational selection step. However, after this initial selection, the region immediately surrounding the binding site undergoes significant structural adjustments. These localized changes, comparable in magnitude to the initial selection, constitute a subsequent induced-fit process that optimizes the binding interface [31]. This two-step model—initial conformational selection followed by induced-fit refinement—is now believed to be widespread in molecular recognition [6].

Quantitative Energetics and Experimental Characterization

Energetic Contributions and Context Dependence

The free energy of binding ((ΔG)) is the ultimate determinant of molecular recognition, and it results from the sum of the favorable energetic contributions of non-covalent interactions and the unfavorable energy required for any desolvation and conformational change.

Table 2: Energetic Contributions and Context-Dependent Behaviors

| Interaction | Typical Contribution to ΔG | Context-Dependent Behavior & Anomalies |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | -10 to -40 kJ/mol | Strength is highly directional. A single bond can be worth ~5 kJ/mol in organic solvents. Net contribution can be minimal if bond formation requires desolvation of polar groups. |

| Van der Waals Forces | -0.4 to -4 kJ/mol per contact | Collective effect of many contacts is significant. Weakened in polarizable solvents. Can regulate hydrophobic hydration via weak H-bonds at the VDW limit [33]. |

| Hydrophobic Effect | -10 to -40 kJ/mol | Can be entropy-driven (classic) or enthalpy-driven ("non-classic") due to release of poorly H-bonded water [32]. Strength depends on solute size (volume vs. surface area scaling) [32]. |

Experimental Techniques for Probing Interactions and Mechanisms

A variety of biophysical techniques are employed to characterize non-covalent interactions and distinguish binding mechanisms.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): SPR is a powerful label-free technique that monitors biomolecular interactions in real-time. When a molecule binds to a target immobilized on a sensor chip, it causes a change in the refractive index at the surface, which is detected as a resonance angle shift. SPR can provide both kinetic rate constants ((k{on}), (k{off})) and the equilibrium binding affinity ((K_D)), which are essential for mechanistic studies [29] [30]. Its main limitations are a relatively narrow detection range and reduced effectiveness for small molecules or low-affinity interactions [29].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): NMR provides atomic-resolution insights into protein structure, dynamics, and interactions. By measuring chemical shifts, residual dipolar couplings, and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement, NMR can identify low-populated conformational states in the unbound protein that resemble the bound state—a key evidence for conformational selection [31] [3]. Its main drawbacks are low sensitivity, requiring high protein concentrations, and spectral complexity for large systems [29].

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Spectroscopy: This rapid-kinetics technique is ideal for measuring the observed rate constant ((k{obs})) of binding over a wide range of ligand concentrations. By analyzing the dependence of (k{obs}) on [L], as detailed in Section 3.1, one can discriminate between induced fit and conformational selection mechanisms [27] [30].