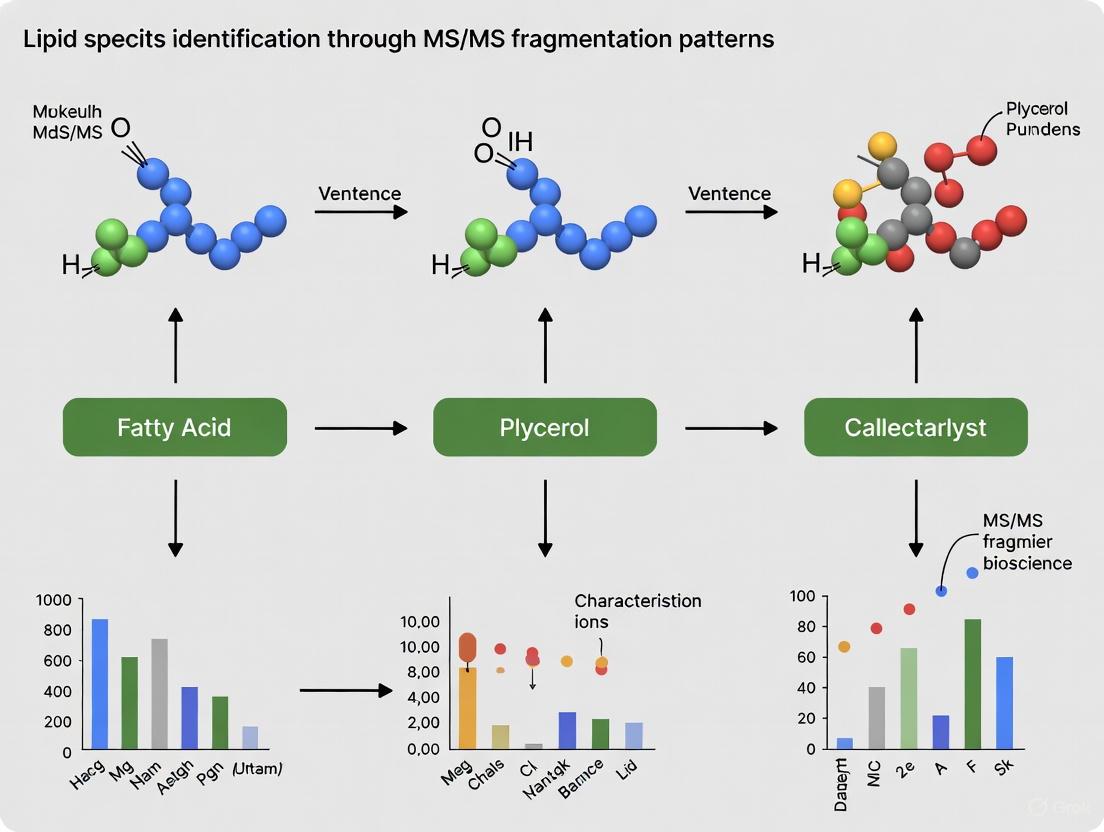

Decoding Lipidomes: A Comprehensive Guide to Lipid Species Identification via MS/MS Fragmentation Patterns

This article provides a systematic overview of modern strategies for lipid species identification using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS).

Decoding Lipidomes: A Comprehensive Guide to Lipid Species Identification via MS/MS Fragmentation Patterns

Abstract

This article provides a systematic overview of modern strategies for lipid species identification using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). It covers the foundational principles of lipid fragmentation, explores advanced methodologies including in-silico spectral libraries and machine learning, addresses key challenges in data analysis and standardization, and discusses rigorous validation techniques. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to enhance accuracy and confidence in lipidomics workflows, with direct implications for biomarker discovery and precision medicine.

The Building Blocks of Lipid Fragmentation: Understanding Core Principles and Lipid Class Signatures

Core Concepts: The Architectural Principles of Lipids

Lipids are a broad group of biomolecules, broadly defined as hydrophobic or amphipathic compounds soluble in organic solvents but insoluble in water [1] [2]. Their structural design consistently follows a modular architecture, built from conserved structural units and highly variable chains. This modularity is key to their diverse biological roles, which include forming cellular membranes, storing energy, and serving as chemical messengers [3] [1].

The international LIPID MAPS consortium classifies lipids into eight major categories based on their core structural modules and biosynthetic origins [4] [2]. The table below summarizes this classification and the core modular components of each category.

Table 1: Lipid Classification and Core Structural Modules

| Lipid Category | Conserved Structural Unit (Backbone) | Variable Elements | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acyls [2] | Carboxyl group (-COOH) [1] |

Hydrocarbon chain length, saturation/unsaturation, double bond position/configuration [1] [2] | Energy source, building block for complex lipids, signaling [3] |

| Glycerolipids [2] | Glycerol backbone [3] | Three fatty acyl chains (can be different combinations) [3] [2] | Energy storage (fats & oils), insulation [3] |

| Glycerophospholipids [2] | Glycerol + Phosphate + Head Group (e.g., choline, ethanolamine) [3] [4] | Head group type, two fatty acyl chains, sn-position subclasses (ester, ether, vinyl ether) [4] | Primary structural component of cell membranes, signaling [3] [4] |

| Sphingolipids [2] | Sphingoid base backbone (from serine & fatty acyl-CoA) [2] | Head group (can be complex carbohydrates), N-linked fatty acid chain [4] [2] | Membrane structural component, cell recognition & signaling [3] |

| Sterol Lipids [2] | Four fused hydrocarbon rings [3] | Side chain structure and functional groups [3] | Membrane fluidity regulation (cholesterol), hormone precursors (steroid hormones) [3] |

The Module-Chain Relationship in Membrane Lipids

The amphipathic nature of many lipids, particularly glycerophospholipids and sphingolipids, is a direct result of their modular design. The conserved "head group" module is hydrophilic (water-loving), while the variable fatty acyl chains are hydrophobic (water-fearing) [1]. In an aqueous environment, these molecules spontaneously organize into bilayers, with hydrophilic heads facing the water and hydrophobic tails shielded inside [3] [1]. This fundamental behavior is the basis for all cellular membranes.

The variable fatty acyl chains are not passive components; their specific structures—such as chain length, degree of unsaturation, and branch points—directly determine membrane physical properties like fluidity and permeability [4]. This allows cells to fine-tune their membrane characteristics in response to environmental changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Platforms for Lipid Analysis

Modern lipid research relies on advanced mass spectrometry (MS) platforms and specialized reagents to deconvolute the immense structural diversity of the lipidome.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) [4] [5] | A soft ionization technique that produces gas-phase ions from a liquid solution, essential for analyzing intact lipid molecular species without fragmentation. |

| Paternò-Büchi (P-B) Reaction [6] | A derivatization technique using photochemical reaction to pin double bonds, enabling determination of C=C double-bond locations in lipids via MS/MS. |

| Charge-Switch Derivatization [4] | Chemical modification of lipids to alter their inherent charge, improving ionization efficiency and enabling access to low-abundance species. |

| Liquid Chromatography (LC) [5] [6] | Separates complex lipid mixtures prior to MS analysis, reducing ion suppression and providing an orthogonal separation dimension (retention time). |

| Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID) [4] [5] | A common fragmentation method in MS/MS that breaks lipid ions by collision with inert gas, generating characteristic fragments for head groups and acyl chains. |

| LipidIN Library [6] | A comprehensive hierarchical fragmentation library containing 168.5 million theoretical lipid entries, used for high-confidence annotation. |

| RAF709 | RAF709, MF:C28H29F3N4O4, MW:542.5 g/mol |

| Nlrp3-IN-62 | Nlrp3-IN-62, MF:C21H15F3N4O3, MW:428.4 g/mol |

Table 3: Core Instrumentation Platforms in Lipidomics

| Platform / Technology | Core Principle | Utility in Lipid Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Shotgun Lipidomics [5] | Direct infusion of lipid extracts into the MS without chromatographic separation. | High-throughput, relative quantification; uses "intrasource separation" based on inherent charge of lipid classes [5]. |

| LC-MS/MS Lipidomics [6] | Couples liquid chromatography separation with tandem mass spectrometry. | Reduces sample complexity, improves ionization, uses retention time as an additional identifier [6]. |

| Ion Mobility-MS (IM-MS) [7] | Separates ions in the gas-phase based on their size, shape, and charge before mass analysis. | Provides an orthogonal separation, resolves isomeric lipids, and generates Collision Cross-Section (CCS) values for identification [7]. |

| Agilent 6560 DTIMS [7] | Drift-Tube Ion Mobility Spectrometry using a uniform electric field. | Considered the gold standard for direct, calibration-free CCS measurement, enabling high-accuracy lipid identification [7]. |

| Waters Cyclic IMS [7] | Traveling-wave IMS with a circular path, allowing multiple passes. | Enables ultra-high resolution separation for challenging isomers (e.g., distinguishing double bond position and geometry) by extending path length [7]. |

| LipidIN Framework [6] | An advanced computational tool integrating a massive spectral library and AI. | Facilitates flash platform-independent annotation and "reverse lipidomics" for high-accuracy fingerprint spectrogram regeneration [6]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs: Addressing Key Experimental Challenges

This section addresses common pitfalls and specific issues researchers encounter during lipid species identification via MS/MS.

FAQ 1: My lipid coverage is low, and I struggle to detect low-abundance species. What strategies can I employ?

Answer: Low coverage and sensitivity are common challenges. Consider these multi-dimensional approaches:

- Implement Charge-Switch Derivatization: Chemically modifying lipids to alter their inherent charge can dramatically improve ionization efficiency in ESI-MS, particularly for low-abundance species that are otherwise masked by highly abundant lipids [4].

- Utilize Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS): Platforms like the Agilent 6560 in demultiplexed (HRdm) mode can increase signal-to-noise ratio and resolution. This mode enhances sensitivity and resolution by computationally deconvoluting signals from multiple, overlapping ion packets injected into the drift tube [7].

- Adopt a Reverse Lipidomics Approach: Tools like LipidIN use a Wide-spectrum Modeling Yield network (WMYn) to regenerate high-accuracy fingerprint spectra from limited data. This "reverse" strategy helps annotate species with weak signals and improves overall coverage by transferring learned patterns across datasets [6].

FAQ 2: How can I confidently resolve and identify lipid isomers that co-elute and have nearly identical mass spectra?

Answer: Distinguishing isomers requires separation beyond traditional LC-MS/MS.

- Leverage High-Resolution Ion Mobility: Platforms like Cyclic IMS are designed for this challenge. By allowing ions to undergo multiple passes around a circular path, the separation path length is extended, increasing resolution. This can baseline-separate isomers based on double-bond position (n-9 vs. n-7) or geometry (cis vs. trans) [7].

- Incorporate CCS Values into Identification Workflows: Collision Cross Section (CCS) values provided by IM-MS are a reproducible, physicochemical property that is unique to an ion's structure. Using CCS values as a mandatory filter in your identification workflow provides an orthogonal identification point that is independent of mass and retention time, drastically reducing false annotations [7].

- Apply Advanced Fragmentation and Computational Libraries: Use specialized techniques like the Paternò-Büchi (P-B) reaction with MS/MS to pinpoint double-bond locations [6]. Furthermore, search your data against comprehensive, hierarchical libraries like the one in LipidIN, which contains theoretical fragmentation data for isomers with different C=C locations [6].

FAQ 3: My lipid annotations are plagued by false positives. How can I improve the confidence of my structural assignments?

Answer: Moving beyond simple mass and fragment matching is key to high-confidence annotation.

- Employ Multi-dimensional MS (MDMS-SL) in Shotgun Lipidomics: This approach involves acquiring data in multiple MS and MS/MS scan modes on the same sample. Cross-examining data from precursor ion scans (PIS), neutral loss scans (NLS), and high-resolution mass measurements acts as a series of filters, significantly increasing the specificity of identification [5].

- Integrate Retention Time (RT) Rules as a Validation Filter: For LC-MS workflows, leverage the predictable relationship between lipid structure and RT. The LipidIN framework, for example, uses three core rules—Equivalent Carbon Number (ECN), Intra-subclass Unsaturation Parallelism (IUP), and Equivalent Separated Carbon Number (ESCN)—to build models that can flag annotations that violate these physicochemical trends, thereby filtering out false positives [6].

- Require Multiple Lines of Evidence for Each Annotation: The highest confidence annotations are achieved by combining multiple data points. A robust annotation should be consistent with: 1) Accurate mass (MS1), 2) Characteristic MS/MS fragments (e.g., head group), 3) Chromatographic retention behavior, and 4) When possible, a matching CCS value from ion mobility [7] [6].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Lipid Structural Elucidation

Protocol: Mapping the Lipidome Using Shotgun Lipidomics with MDMS-SL

This protocol outlines the steps for a comprehensive, direct-infusion lipid analysis, ideal for relative quantification of hundreds of lipid species across multiple classes [5].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation & Lipid Extraction: Homogenize tissue or lyse cells. Perform a multiplexed lipid extraction using a method like Bligh & Dyer (chloroform:methanol:water) to recover a broad range of lipid classes. Add internal standards (e.g., odd-chain or deuterated lipids) for each class of interest at the beginning of extraction for accurate quantification [5].

- Direct Infusion: Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a known volume of a pre-defined infusion solvent (e.g., chloroform:methanol:isopropanol with additives like ammonium acetate or formic acid to promote ionization). Continuously infuse the sample into the ESI source of a mass spectrometer (often a QqQ or Q-TOF) using a syringe pump at a constant flow rate [5].

- Data Acquisition in Multiple Modes:

- MS¹ Full Scan: Acquire a full mass spectrum to profile all ionized lipid species. High mass accuracy is crucial here [5].

- Utilize Intrasource Separation: Exploit the fact that different lipid classes ionize with different efficiencies in positive or negative mode and under specific solvent conditions. This provides a "pseudo-separation" in the ion source [5].

- Tandem MS (MS/MS) Scans: Conduct a series of targeted MS/MS scans to identify individual molecular species within each class.

- Precursor Ion Scan (PIS): For example, in positive mode, a PIS of m/z 184 is specific for phosphocholine-containing lipids (PC, SM). A PIS of m/z 264 can detect ceramide-backbone lipids [5].

- Neutral Loss Scan (NLS): For example, an NLS of 141 Da is characteristic of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) in positive mode [5].

- Data Analysis and Identification: Process the data using specialized software. Identify lipid classes based on characteristic fragments from PIS/NLS. Identify individual molecular species within a class by the combination of the precursor ion mass and the fragment ions corresponding to their specific fatty acyl chains. Quantify species by comparing their signal intensity to that of the pre-added internal standard of the same class [5].

Protocol: Advanced Structural Elucidation of Lipid Isomers Using LC-Ion Mobility-MS

This protocol describes a workflow for separating and identifying structurally similar lipids that are indistinguishable by conventional LC-MS/MS.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Chromatographic Separation: First, separate the complex lipid extract using reversed-phase or HILIC liquid chromatography. This reduces sample complexity and minimizes ion suppression before the sample enters the mass spectrometer [6].

- Ion Mobility Separation: As ions elute from the LC, they are introduced into the ion mobility spectrometer (e.g., DTIMS, TIMS, or Cyclic IMS). Here, an electric field drives ions through a buffer gas. Compact isomers (e.g., with trans double bonds or double bonds closer to the head group) will drift faster and have a smaller Collision Cross Section (CCS), while extended isomers (e.g., with cis double bonds or double bonds near the chain center) will drift slower and have a larger CCS [7].

- Mass Analysis and Fragmentation: After mobility separation, ions are analyzed by a high-resolution mass analyzer (e.g., TOF) to determine their accurate mass. Ions of interest can be selectively fragmented (CID) to obtain structural MS/MS spectra.

- Data Integration and Confident Annotation: The key step is to integrate all dimensions of data:

- Use the accurate mass from the MS1 spectrum.

- Use the retention time from the LC separation.

- Use the CCS value from the ion mobility separation as a highly specific identifier.

- Use the MS/MS spectrum for final confirmation of the lipid class and acyl chains.

- Match all these parameters (mass, RT, CCS, MS/MS) against experimental or predicted databases (e.g., the LipidIN library) for a high-confidence, definitive annotation of isomeric species [7] [6].

In lipidomics, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) enables structural elucidation by breaking precursor lipid ions into characteristic fragments. These fragmentation pathways fall into two primary categories: those that reveal the lipid's headgroup and those that provide information about its fatty acyl chains. The predictable nature of these fragments is foundational for lipid identification [8].

Lipids fragment in predictable ways due to their modular construction, typically comprising a conserved polar headgroup and variable-length hydrocarbon chains [8]. During MS/MS analysis, the first step in data interpretation is often to identify the headgroup, which defines the lipid class (e.g., Phosphatidylcholine (PC), Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)). This is achieved by detecting either a low-mass, charged headgroup fragment or a neutral loss (NL) corresponding to the mass of the headgroup [9]. Subsequently, fragments revealing the composition of the fatty acyl chains, such as ketenes or free fatty acid ions, are used to determine the individual chain lengths and degrees of unsaturation [8] [10].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: Why are my headgroup diagnostic ions absent or of low intensity in my MS/MS spectra?

- Potential Cause: The issue often relates to instrument-specific parameters, particularly the applied collision energy.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize Collision Energy: Perform a collision energy ramp for the lipid class of interest. Too low energy may not induce fragmentation, while too high energy may shatter the precursor ion into non-diagnostic small fragments [10].

- Verify Polarity Mode: Ensure you are using the correct ionization polarity. For example, precursor ion scan for m/z 184 is highly specific for PCs in positive mode, but many lipid classes (e.g., PI, PG) are better analyzed in negative mode where they form [M-H]â» or [M+acetate]â» adducts [9].

- Check for Isobaric Interference: Low-abundance lipids can be obscured by background noise or co-eluting isobaric species. Improved chromatographic separation or using a higher-resolution mass spectrometer can mitigate this [11].

Q2: How can I differentiate isomeric lipids that share the same mass and headgroup?

- Potential Cause: Routine MS/MS often cannot distinguish isomers differing in sn-position (acyl chain attachment site on the glycerol backbone) or double bond (C=C) location.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- For sn-Position: Use advanced methods like the Paternò-Büchi (PB) reaction with MS³. This photochemical reaction, using reagents like 2-acetylpyridine, generates sn-position diagnostic ions through cross-ring cleavage fragments [12].

- For C=C Location:

- Method A (Chemical Derivatization): Implement an offline PB reaction with acetone. The reaction adds a carbonyl group across the double bond, and subsequent CID produces diagnostic ions that reveal the C=C location [12] [13].

- Method B (Computational Prediction): Employ software tools like LC=CL which uses machine learning to predict C=C locations based on the lipid's retention time in routine RPLC-MS/MS analyses, without requiring specialized instrumentation [14].

Q3: My lipid coverage is low in data-dependent acquisition (DDA). How can I improve it?

- Potential Cause: DDA preferentially selects the most abundant precursor ions, causing low-abundance lipids to be missed.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use Data-Driven Acquisition: Implement an automated, iterative inclusion/exclusion list approach. The mass spectrometer first performs a full scan, and ions above a threshold are added to an inclusion list for MS/MS in subsequent runs. After fragmentation, these ions are moved to an exclusion list to ensure comprehensive coverage of lower-abundance species [11].

- Employ Dual Dissociation Techniques: For complex lipids like phosphatidylcholines, combining higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) with collision-induced dissociation (CID) can produce complementary fragment ions, improving characterization confidence [11].

Lipid Headgroup Diagnostic Ions and Neutral Losses

The table below summarizes common diagnostic scans for major lipid classes, which can be performed on triple quadrupole instruments [9].

Table 1: Common Headgroup-Diagnostic MS/MS Scans for Lipid Identification

| Lipid Class | Scan Mode | Diagnostic Ion or Neutral Loss (Da) | Adduct | Key Fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC, LysoPC, SM | Precursor (Prec) | 184 | [M+H]⺠| Phosphocholine headgroup (Câ‚…Hâ‚â‚…NOâ‚„Pâº) |

| PE, LysoPE | Neutral Loss (NL) | 141 | [M+H]⺠| Phosphoethanolamine |

| PS | Neutral Loss (NL) | 185 | [M+H]⺠| Serine headgroup |

| PI | Neutral Loss (NL) | 277 | [M+NH₄]⺠| Inositol phosphate |

| PG | Neutral Loss (NL) | 189 | [M+NH₄]⺠| Glycerophosphate |

| PA | Neutral Loss (NL) | 115 | [M+NH₄]⺠| Phosphate acid |

| MGDG | Neutral Loss (NL) | 179 | [M+NH₄]⺠| Monogalactose |

| DGDG | Neutral Loss (NL) | 341 | [M+NH₄]⺠| Digalactose |

| LysoPG | Precursor (Prec) | 153 | [M-H]â» | Dehydroglycerophosphate |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Lipid Structural Elucidation

Protocol 1: Determining Double Bond Position via Paternò-Büchi (PB) Derivatization

This protocol uses an in-solution PB reaction with acetone to pinpoint C=C locations in unsaturated lipids [12] [13].

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the lipid extract in a suitable solvent (e.g., chloroform/methanol).

- PB Reaction Setup:

- Mix the lipid sample with a large molar excess of acetone (e.g., 1:100 lipid/acetone).

- Load the mixture into a UV-transparent fused silica capillary flow cell.

- Photochemical Reaction:

- Irradiate the flowing mixture with UV light (254 nm) for a short, controlled duration (e.g., 4-5 seconds).

- The acetone undergoes a [2+2] cycloaddition across the carbon-carbon double bond(s) in the fatty acyl chains, forming an oxetane ring.

- MS/MS Analysis:

- Analyze the reacted solution using nanoESI-MS/MS.

- Subject the PB-derivatized lipid precursor ion ([M+PB reagent+H]âº) to low-energy CID.

- Data Interpretation: The oxetane ring cleaves preferentially, generating two pairs of diagnostic ions for each original C=C bond. The mass difference between these ions directly reveals the location of the double bond in the fatty acyl chain.

Protocol 2: Generating a Tailored Spectral Library with Library Forge

For high-confidence identification, you can create instrument-specific spectral libraries using tools like Library Forge within the LipiDex environment [8].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution MS/MS data from a mixture of lipid reference standards or a complex lipid extract.

- Data Processing:

- Convert raw files to MGF format.

- LipiDex performs putative lipid identifications using an existing library (e.g., LipidBlast).

- Consensus Spectrum Generation:

- The software clusters high-quality, putatively identified MS/MS spectra and generates a single consensus spectrum (median m/z and intensity) for each lipid identification.

- Rule Learning with Library Forge:

- An adaptive set of m/z offsets is applied to each consensus spectrum to create "annotation spectra."

- The algorithm compares annotation spectra within a lipid class to automatically deduce the conserved fragmentation rules (e.g., neutral losses, characteristic ions) without manual annotation.

- In-Silico Library Generation: The derived rules are applied to a database of theoretical lipid structures, creating a tailored, high-quality in-silico spectral library ready for searching experimental data.

Workflow Diagram: Lipid Identification via MS/MS Fragmentation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying a lipid's structure through a series of decisions based on its MS/MS fragmentation pattern.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for Lipid Fragmentation Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Acetone | PB Reagent | Serves as the photochemical reagent for derivatizing C=C bonds, enabling localization via CID [12] [13]. |

| 2-Acetylpyridine | PB Reagent | An alternative PB reagent that enhances the generation of sn-position diagnostic ions during MS³ analysis [12]. |

| 13C-diazomethane (¹³C-TrEnDi) | Derivatization Reagent | Enhances ionization efficiency and uniformity of glycerophospholipids (like PE) in positive ion mode by adding a fixed positive charge [13]. |

| Library Forge (in LipiDex) | Software Algorithm | Automatically derives lipid fragmentation rules from experimental MS/MS data, enabling rapid creation of tailored in-silico spectral libraries [8]. |

| LipidBlast | Software / Database | A large, in-silico generated MS/MS library of 212,516 spectra for 119,200 lipids, used as a reference for lipid identification across platforms [10]. |

| LC=CL (LDA C=C Localizer) | Software Tool | Uses machine learning and retention time data from routine RPLC-MS/MS to automatically assign fatty acyl C=C positions [14]. |

| MitoCur-1 | MitoCur-1, MF:C65H64Cl2O6P2, MW:1074.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cenisertib benzoate | Cenisertib benzoate, CAS:1145859-64-8, MF:C31H36FN7O3, MW:573.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Concepts and Fundamental FAQs

FAQ: What are neutral loss and precursor-ion scans, and why are they fundamental in lipidomics?

Neutral loss (NL) and precursor-ion (PI) scans are targeted data acquisition strategies in tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) used to selectively detect classes of molecules that share common fragmentation behaviors. In lipidomics, they are essential for screening complex biological samples for specific lipid families.

- Precursor-Ion Scan: This scan mode identifies all precursor ions that fragment to produce a specific, common product ion. For example, in negative ion mode, a precursor-ion scan for m/z 153.0 can selectively detect sulfatides, as this ion is a characteristic fragment of the sulfate group in their head structure [10].

- Neutral Loss Scan: This mode detects all precursor ions that lose a specific, uncharged molecule (neutral loss) during fragmentation. A classic example is the neutral loss of 141 Da in positive ion mode, which is characteristic of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipids due to the loss of their phosphoethanolamine head group [10].

These techniques move beyond simple library matching by leveraging class-specific fragmentation rules, allowing researchers to fish out specific lipid families from a sea of thousands of ions, thus providing a targeted approach to lipidome characterization [15] [10].

FAQ: What are the main limitations of using only MS/MS for lipid identification?

While powerful, conventional MS/MS has several limitations:

- Inability to Distinguish Isomers: MS/MS often cannot differentiate between lipids that are positional isomers (e.g., differing in the sn-1/sn-2 chain position on the glycerol backbone) or that have the same double bond count but different double bond locations [15] [16].

- Incomplete Fragmentation Pathways: Many fragment ions in an MS/MS spectrum remain unannotated, and the pathways linking them are not always clear. Product ions may be derived from intermediary ions, not directly from the precursor, making structural interpretation challenging [15].

- Limited Structural Information: MS/MS alone frequently fails to provide specific positional information on sub-structures, such as the glycosylation site in flavonoids or the exact location of acyl chains [15].

FAQ: How can multi-stage mass spectrometry (MSâ¿) address the limitations of MS/MS?

Multi-stage MS (MSâ¿) extends the fragmentation process, breaking down a precursor ion, isolating one of its product ions, and then fragmenting that ion further. This creates a hierarchical fragmentation tree or mass spectral tree that delineates the relationships between ions [15].

- Elucidating Fragmentation Pathways: MSâ¿ allows for the recursive reconstruction of fragmentation pathways, linking specific sub-structures to the complete molecular structure [15].

- Differentiating Isomers: Isomers that produce nearly identical MS/MS spectra can often be distinguished by their unique fragmentation patterns in MS³ or MSâ´. For instance, 6-C- and 8-C-glycosidic flavonoid isomers could only be differentiated using clear diagnostic ions present in MS³ spectra [15].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between an MSâ¿ experimental sequence and the resulting fragmentation tree.

Advanced Applications & Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: My data-dependent acquisition (DDA) is missing low-abundance lipids. How can I improve coverage?

Conventional DDA methods often prioritize the most abundant ions, missing lower-intensity signals. An automated, data-driven MS/MS acquisition scheme can significantly improve lipidome coverage [11].

- Problem: Low-abundance precursor ions fall below the intensity threshold for triggering fragmentation in DDA experiments.

- Solution: Implement an iterative inclusion/exclusion list strategy.

- Step 1: Perform an initial full-scan MS analysis of the sample to create a list of precursor ions of interest (the "inclusion list").

- Step 2: In subsequent injections, the mass spectrometer is programmed to preferentially fragment ions on the inclusion list.

- Step 3: After fragmentation, these ions are automatically moved to an "exclusion list" to prevent re-analysis, freeing up instrument time for the next set of targets.

- Step 4: The process is repeated over iterative analyses, updating the lists each time. This ensures comprehensive coverage of both high- and low-abundance species [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: How can I gain more structural detail for challenging lipid classes like phosphatidylcholines?

Some lipid classes require more than one fragmentation method for complete characterization. Combining multiple dissociation techniques provides complementary structural information [11].

- Problem: Standard collision-induced dissociation (CID) of phosphatidylcholines (PCs) in positive mode primarily provides headgroup information (e.g., m/z 184) but limited detail on the fatty acyl chains.

- Solution: Incorporate dual dissociation techniques.

- Protocol: For the same PC species, acquire MS/MS spectra using both higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) and CID.

- Outcome: HCD can provide more informative fragments related to the fatty acyl side chains, while CID confirms the headgroup identity. The combination of these spectra yields a more complete structural picture for accurate annotation [11].

Table 1: Characteristic Ions for Precursor-Ion Scanning of Major Lipid Classes

| Lipid Class | Adduct | Scan Type | Characteristic Ion (m/z) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfatides | [M-H]â» | Precursor-ion | 153.0 | [HSOâ‚„]â» fragment from the sulfate headgroup [10] |

| Phosphatidic Acid (PA) | [M-H]⻠| Precursor-ion | 153.0 | [C₃H₆O₅P]⻠fragment (glycerophosphate) [10] |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | [M-H]⻠| Precursor-ion | 87.0 | [C₂H₃O₂]⻠fragment (serine headgroup) [10] |

| Ceramides (Multiple Classes) | [M+H]⺠| Precursor-ion | 264.3 | Sphingoid base-related ion for Ceramide [NS] (d18:1/ * ) [17] |

| Sphingomyelin (SM) | [M+H]⺠| Precursor-ion | 184.1 | Phosphocholine headgroup [10] |

Table 2: Characteristic Neutral Losses for Major Lipid Classes

| Lipid Class | Adduct | Neutral Loss (Da) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | [M+H]⺠| 141.0 | Loss of phosphoethanolamine headgroup [10] |

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | [M+H]⺠| 59.0 | Loss of trimethylamine [(CH₃)₃N] from the headgroup [10] |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | [M+H]⺠| 185.0 | Loss of serine headgroup [10] |

| Monohexosylceramide (HexCer) | [M+CH₃COO]⻠| 162.1 | Loss of a hexose sugar moiety (e.g., glucose or galactose) [17] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Databases for Lipid MS/MS Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| LipidBlast [10] | In-silico MS/MS Library | Provides a massive library of 212,516 theoretically generated MS/MS spectra for 119,200 lipids. | Serves as a spectral reference for annotating lipids in the absence of an authentic standard. |

| LIPID MAPS Tools [18] | Online MS Analysis Tools | Performs precursor-ion and neutral loss searches using computationally generated or database-derived masses. | Enables targeted searches for specific lipid classes based on characteristic fragments. |

| MS-DIAL [17] | Data Analysis Software | Integrates retention time, precursor m/z, and MS/MS spectral matching for untargeted metabolomics/lipidomics. | Comprehensive identification and quantification of lipids from raw LC-MS/MS data files. |

| MassQL [19] | Query Language | A universal language for flexibly searching MS data for complex patterns (isotopes, neutral losses, fragments). | Reproducible mining of public and private MS data repositories for specific compounds or classes. |

| MS-FINDER [17] | Structure Elucidation Software | Predicts fragmentation and annotates substructures of fragment ions using hydrogen rearrangement rules. | Provides substructure-level annotation for unknown MS/MS spectra and assists in de novo identification. |

| SC99 | SC99, MF:C15H8Cl2FN3O, MW:336.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Mlk3-IN-1 | Mlk3-IN-1, MF:C20H16F6N4O2S, MW:490.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The Impact of Instrumentation and Dissociation Techniques on Observed Fragmentation

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my lipid identification confidence low, and how can I improve it?

Issue: Low-confidence lipid identifications from MS/MS data, often due to suboptimal fragmentation spectra that lack specific fragment ions needed for definitive side chain assignment.

Solution: Implement a dual-dissociation technique workflow. This approach leverages the complementary strengths of different fragmentation methods to generate more comprehensive structural information [11].

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Perform an initial data-dependent acquisition (DDA) using Higher-energy Collisional Dissociation (HCD) to obtain spectra rich in headgroup and characteristic neutral loss fragments [20].

- Automate a second analysis using an inclusion list generated from the first run. Target the precursor ions of interest, this time using Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID) [11].

- Integrate the spectra from both HCD and CID analyses. HCD often provides better coverage of low mass-to-charge (

m/z) fragments (e.g., for headgroups), while CID can yield more detailed information on fatty acyl chains [11]. - Search the combined spectral information against a tailored, data-driven spectral library generated using tools like Library Forge within the LipiDex environment to increase matching confidence [8].

FAQ 2: How can I identify lipids for which I have no reference standards?

Issue: The inability to identify novel or unanticipated lipids because they are absent from commercial spectral libraries.

Solution: Utilize in-silico generated spectral libraries and data-driven algorithms that learn fragmentation rules directly from experimental data, bypassing the need for a physical reference standard for every potential lipid [8] [10].

Step-by-Step Guide:

- Acquire high-quality MS/MS spectra from a complex lipid extract or any available reference standards using your specific instrumental platform [8].

- Process the data using a software tool like LipiDex. Putative identifications are used to generate high-quality consensus spectra [8].

- Employ the Library Forge algorithm (embedded in LipiDex) to analyze these consensus spectra. The algorithm exploits the modular structure of lipids to derive

m/zand intensity patterns, automatically extracting the minimal set of conserved fragmentation rules for a given lipid class [8]. - Apply these learned rules to a database of theoretical lipid species to generate a large, tailored in-silico spectral library. This library is specific to your instrument and dissociation techniques, improving identification rates for lipids without commercially available standards [8] [10].

FAQ 3: Which dissociation technique should I use to preserve and locate labile post-translational modifications (PTMs) on proteins or peptides?

Issue: Traditional fragmentation methods like CID can cleave off labile PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation, glycosylation) before backbone fragmentation, preventing localization of the modification site.

Solution: Use electron-based dissociation techniques, specifically Electron Transfer Dissociation (ETD) or Electron Capture Dissociation (ECD). These are "non-ergodic" processes that cleave the backbone without dissipating energy into labile side chains [20] [21].

Step-by-Step Guide:

- For peptide/protein analysis with suspected labile PTMs, configure your mass spectrometer method to include ETD if available.

- ETD works by transferring an electron from a radical anion to a positively charged peptide/protein. This induces fragmentation along the backbone N–Cα bonds, producing c- and z-type ions while leaving labile PTMs intact [20].

- For a more complete structural picture, toggle between ETD and CID/HCD in parallel experiments. ETD will preserve PTMs and provide sequence coverage, while CID/HCD can generate complementary b- and y-type ions, helping to confirm the sequence and potentially provide additional information [20].

Technical Reference Data

Table 1: Comparison of Common Molecular Dissociation Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism | Best For | Fragment Ions (e.g., Peptides) | Effect on Labile PTMs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CID / CAD [20] [21] | Collisions with neutral gas; "slow-heating" method that increases Boltzmann temperature. | Peptides, lipids, and other small molecules. | b-, y- type ions. | Often cleaves labile PTMs. |

| HCD [20] | A type of CID with higher energy collisions in a dedicated cell. | Detecting low m/z fragments; TMT experiments; phosphotyrosine. |

b-, y- type ions. | Can cleave labile PTMs. |

| ETD [20] [21] | Electron transfer from a radical anion to a multiply charged cation. | Peptides/proteins with labile PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation, glycosylation). | c-, z- type ions. | Preserves labile PTMs. |

| ECD [20] [21] | Capture of a thermal-energy electron by a multiply charged cation. | Primarily used in FT-ICR MS for proteins/peptides with PTMs. | c-, z- type ions. | Preserves labile PTMs. |

| UVPD [20] | Photons from a laser are absorbed, leading to rapid excitation and fragmentation. | Provides complementary fragments; no low-mass cutoff in ion traps. | a-, x-, b-, y-, c-, z-type ions; diverse fragments. | Offers a mix of backbone and side-chain fragments. |

Table 2: Key Instrumentation Platforms and Tandem MS Capabilities

| Instrument Platform | Tandem MS Method | Dissociation Techniques Typically Available | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triple Quadrupole (QqQ) [21] | In-space | CID | Robust, quantitative; Q1 selects precursor, Q2 is collision cell, Q3 analyzes products. |

| Q-TOF [21] | In-space | CID, HCD | High mass accuracy for both precursor and product ions. |

| Ion Trap [21] | In-time | CID, ETD, UVPD | Can perform MSn (multiple stages of fragmentation). |

| Orbitrap (Hybrid) [20] [21] | In-space & In-time | CID, HCD, ETD, UVPD | High resolution and mass accuracy; often multiple dissociation sources in one system. |

| FT-ICR [21] | In-time | ECD, IRMPD | Ultra-high resolution and mass accuracy. |

Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Lipid Identification Workflow with Data-Driven Libraries

Diagram: Technique Selection for Structural Elucidation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Software for Fragmentation Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Reference Standards (e.g., Avanti Polar Lipids) [8] | Provide experimental MS/MS spectra for method development and validation. | Creating a ground-truth dataset to model fragmentation rules for a new lipid class. |

| Pierce HeLa Protein Digest Standard [22] | Checks overall LC-MS/MS system performance and sample preparation efficacy. | Troubleshooting poor fragmentation quality by isolating whether the issue is with the sample or the instrument. |

| Pierce Calibration Solutions [22] | Calibrates the mass axis of the mass spectrometer for accurate mass measurement. | Ensuring accurate m/z assignment for precursor and product ions, which is critical for database searching. |

| LipiDex Software Suite [8] | Integrates spectral library generation and data-driven fragmentation rule learning. | Processing raw MS/MS data to create instrument-specific lipid libraries and confident identifications. |

| LipidBlast Library [10] | A large, in-silico generated MS/MS library of 212,516 spectra for 119,200 lipids. | Identifying lipid species for which a physical reference standard is not available. |

| Library Forge Algorithm [8] | Derives lipid fragment m/z and intensity patterns directly from high-resolution experimental spectra. |

Automating the creation of tailored spectral libraries, reducing development time from days to minutes. |

| Antitumor agent-182 | Antitumor agent-182, MF:C33H30BrClNO2PS2, MW:683.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| hAChE-IN-7 | hAChE-IN-7, MF:C38H55N3O3, MW:601.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

From Spectra to Identifications: Advanced Workflows and Spectral Library Generation

Lipid species identification via MS/MS fragmentation patterns represents a cornerstone of modern metabolomics research. The structural diversity of lipids, however, presents a significant analytical challenge, as the number of potential lipid structures far exceeds the availability of purified chemical standards for experimental spectral libraries. In-silico spectral libraries bridge this gap by using computational methods to predict theoretical tandem mass spectra for hundreds of thousands of lipid structures. This technical support center addresses the most common experimental and computational issues researchers encounter when implementing these powerful tools, with particular focus on the widely adopted LipidBlast database and its contemporary alternatives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is LipidBlast compatible with my mass spectrometer? LipidBlast is designed for platform independence and has been validated using tandem mass spectra from over 40 different mass spectrometer types, including both low-resolution and high-resolution instruments. This covers major vendors such as Sciex, Agilent, Bruker, Thermo Fisher, and Waters. The libraries work with both low-resolution ion traps and high-resolution instruments like Q-TOF and Orbitrap systems. [23]

How comprehensive is LipidBlast's lipid coverage? The LipidBlast database contains 212,516 in-silico generated MS/MS spectra covering 119,200 compounds from 26 lipid classes, including phospholipids, glycerolipids, bacterial lipoglycans, and plant glycolipids. This extensive coverage includes common lipid categories such as phosphatidylcholines (PC), phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), triacylglycerols (TG), sphingomyelins (SM), and many others. [10]

What validation metrics exist for LipidBlast's predictive accuracy? Independent validation of LipidBlast has demonstrated strong performance characteristics with a true positive rate (sensitivity) of 89%, a specificity of 96%, and a false positive rate of 4%. When tested against 325 accurate mass QTOF MS/MS spectra from the NIST11 database not included in its development, LipidBlast correctly annotated 87% of spectra for lipid class, carbon number, and double bond count. [10]

Which lipid structural details can LipidBlast identify? LipidBlast reliably identifies lipid class, total carbon numbers, and total double bonds from MS/MS spectra. However, it cannot determine double bond positions, stereospecificity, or regiospecificity (sn-1/sn-2 positioning) based on current fragmentation rules. [10]

How does LipidBlast handle different adduct ions? LipidBlast generates spectra for multiple common adduct ions observed in both positive and negative ionization modes, including [M+H]âº, [M+Na]âº, [M+NHâ‚„]âº, [M-H]â», and [M-2H]²â». The number of spectra per lipid class varies based on the biologically relevant adducts, with some classes like phosphatidylethanolamines represented in three different adduct forms. [10]

Can I use LipidBlast if I only have LC-MS (without MS/MS) capability? Yes, but with limitations. For instruments with only MS1 capability, LipidBlast provides an m/z lookup table containing all lipids and their adduct masses. This approach requires high mass accuracy instruments (e.g., LC-TOF-MS, Orbitrap) and should incorporate retention time information to resolve isobaric compounds that yield multiple hits. [23]

LipidBlast Database Composition

Table 1: Lipid classes and spectral coverage in the LipidBlast database

| Lipid Class | Short Name | Number of Compounds | Number of MS/MS Spectra |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholines | PC | 5,476 | 10,952 |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines | lysoPC | 80 | 160 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines | PE | 5,476 | 16,428 |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamines | lysoPE | 80 | 240 |

| Phosphatidylserines | PS | 5,123 | 15,369 |

| Sphingomyelins | SM | 168 | 336 |

| Phosphatidic acids | PA | 5,476 | 16,428 |

| Phosphatidylinositols | PI | 5,476 | 5,476 |

| Phosphatidylglycerols | PG | 5,476 | 5,476 |

| Cardiolipins | CL | 25,426 | 50,852 |

| Triacylglycerols | TG | 2,640 | 7,920 |

| Monoacylglycerols | MG | 74 | 148 |

| Diacylglycerols | DG | 1,764 | 3,528 |

| Monogalactosyldiacylglycerols | MGDG | 5,476 | 21,904 |

| Digalactosyldiacylglycerols | DGDG | 5,476 | 10,952 |

| Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerols | SQDG | 5,476 | 5,476 |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Getting multiple duplicate hits during UPLC-MS/MS analysis. Solution: This frequently occurs with fast-scanning MS/MS instruments that generate numerous spectra for the same compound. Implement post-processing algorithms to exclude these duplicates. Software tools like MS-DIAL and LipiDex contain built-in functionality to consolidate duplicate identifications based on retention time and spectral similarity. [23]

Problem: Many lipid signals remain unidentified in my samples. Solution: LipidBlast, while comprehensive, doesn't cover all lipidomic space. Combine LipidBlast with complementary databases such as LIPID MAPS, which contains 48,179 lipid species across 8 major categories. For specialized bacterial or plant lipids not covered in mainstream databases, consider using tools like Library Forge within LipiDex to generate custom spectral libraries from your experimental data. [24] [25]

Problem: Inconsistent spectral matching scores across different instruments. Solution: Lipid fragment intensity patterns vary significantly across instrument platforms and dissociation techniques. Rather than using generic spectral libraries, employ algorithmic approaches like Library Forge that derive fragmentation rules directly from your experimental spectra. This creates instrument-specific libraries that improve matching confidence by accounting for technique-specific intensity variations. [25]

Problem: Distinguishing between isobaric lipid species. Solution: LipidBlast alone may not resolve isobaric compounds with identical mass but different structures. Implement orthogonal separation techniques such as ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) to incorporate collision cross-section (CCS) values as an additional identification parameter. The LIPID MAPS database contains over 3,800 experimental CCS values for this purpose. [24]

Problem: Installing LipidBlast on computers without internet access. Solution: Download the necessary files ("LipidBlast-Full-Release-3.zip") from the Fiehn Lab website on an internet-connected computer. Transfer the "LipidBlast-neg.msp" and "LipidBlast-pos.msp" files from the "LipidBlast-ASCII-spectra" folder to the directory "C:\Users\user.name\AppData\Local\Nonlinear Dynamics\Progenesis QI\LipidBlast" on the target computer. [26]

Experimental Protocol: Lipid Identification Using LipidSearch Software

For researchers using Thermo Scientific instruments, the LipidSearch software provides an integrated workflow for lipid identification that can incorporate LipidBlast libraries. [27]

Data Acquisition:

- Perform LC-MS/MS analysis in both positive and negative ionization modes

- Use data-dependent acquisition (DDA) with CID/HCD fragmentation

- Maintain mass accuracy below 5 ppm for both precursor and product ions

Software Configuration:

- Set Target Database to appropriate instrument type (e.g., Q Exactive)

- Select Search Type: Product

- Set Experiment Type: LC-MS

- Configure mass tolerances: Precursor tolerance 5.0 ppm, Product tolerance 5.0 ppm

- Apply intensity threshold: Product ion 1.0%

- Set m-score threshold: 2.0 [28]

Data Processing:

- Merge results from positive and negative ion mode analyses

- Align samples using Alignment Method: Median

- Apply Toprank Filter: On

- Set Main node Filter: Main isomer peak

- Apply m-Score Threshold: 5.0

- Curate results using ID quality filter grades "A" and "B" for high-confidence identifications [28]

Experimental Protocol: Implementing LipidBlast with NIST MS Search GUI

For visual inspection and manual validation of lipid identifications: [23]

Library Installation:

- Download LipidBlast ASCII library files

- Import into NIST MS Search GUI using the library management utility

- Configure fragment mass tolerance appropriate to your instrument

Spectral Matching:

- Load experimental MS/MS spectra in MGF format

- Perform similarity search against LipidBlast libraries

- Visually inspect spectral matches for characteristic fragment patterns

- Verify headgroup fragments and acyl chain neutral losses

Batch Processing:

- For high-throughput analysis, use NIST MS PepSearch for batch processing

- Configure output to generate Excel-compatible reports

- Process thousands of spectra simultaneously with typical speeds of 1000 spectra/second

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key resources for in-silico lipid identification workflows

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LipidBlast | In-silico MS/MS Library | Provides 212,516 predicted spectra for lipid identification | Free download from Fiehn Lab |

| LIPID MAPS | Comprehensive Lipid Database | Structural and taxonomic data for 48,179 lipids | Online portal |

| MS-DIAL | Data Processing Software | Integrates LipidBlast for LC-MS/MS lipid identification | Open source |

| LipiDex | Data Processing Environment | Includes Library Forge for custom spectral library generation | Free for academic use |

| LipidSearch | Commercial Identification Platform | Automated lipid ID with comprehensive database | Thermo Fisher subscription |

| NIST MS Search | Spectral Matching GUI | Visual inspection and manual validation of spectra | Commercial license |

| Progenesis QI | Data Analysis Software | Compatible with LipidBlast database for lipid identification | Commercial license |

| JAK2 JH2 binder-1 | JAK2 JH2 binder-1, MF:C29H25N7O6S, MW:599.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BI-9787 | BI-9787, MF:C24H29F2N5O2S, MW:489.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Lipid Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for lipid identification using in-silico spectral libraries:

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Custom Library Generation with Library Forge: For specialized research applications beyond LipidBlast's coverage, the Library Forge algorithm embedded in LipiDex enables generation of custom spectral libraries without manual annotation. This approach: [25]

- Learns fragmentation patterns directly from experimental spectra

- Reduces library development time from days to minutes

- Creates instrument-specific libraries for improved matching confidence

- Handles diverse dissociation techniques (CID, HCD, UVPD)

Integrating Multiplatform Data: Advanced lipid identification strategies combine multiple data dimensions:

- Accurate mass measurement (< 5 ppm) for elemental composition

- MS/MS spectral matching against in-silico libraries

- Retention time prediction for additional confirmation

- Collision cross-section (CCS) values from ion mobility spectrometry

- Isotopic labeling for validation of fragmentation pathways [25]

Quality Control Considerations: Implement rigorous QC measures to ensure identification accuracy:

- Analyze standard reference materials (e.g., NIST SRM 1950)

- Use heavy isotope-labeled internal standards

- Establish reproducibility metrics across technical replicates

- Validate identifications with orthogonal analytical methods [25]

Comparison of In-Silico Lipid Identification Approaches

Table 3: Performance characteristics of different lipid identification strategies

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LipidBlast | High coverage (119K compounds), platform independence, validated accuracy | Cannot determine double bond positions or stereochemistry | Untargeted lipid discovery, plant and bacterial lipidomics |

| LIPID MAPS Tools | Integrated with structural database, standardized taxonomy | Smaller coverage for bacterial lipids | Targeted analysis of mammalian lipids |

| Library Forge | Instrument-specific libraries, handles novel fragmentation techniques | Requires experimental data for training | Specialized dissociation methods, novel lipid classes |

| LipidSearch | Automated workflow, optimized for Orbitrap platforms | Commercial license required | High-throughput screening in clinical research |

In-silico spectral libraries have revolutionized lipid identification by overcoming the limitation of available chemical standards. LipidBlast remains a foundational tool with its extensive coverage and platform independence, while newer algorithmic approaches like Library Forge offer customized solutions for specific instrumental platforms and novel lipid classes. By understanding the capabilities, limitations, and proper implementation of these resources, researchers can dramatically improve the accuracy and throughput of their lipidomics workflows, driving advances in basic research and drug development.

Library Forge is an algorithm embedded within the LipiDex data processing environment that addresses a critical bottleneck in lipidomics: the time-consuming manual creation of in-silico lipid spectral libraries. It automates the derivation of lipid fragmentation rules directly from high-resolution experimental MS/MS data, enabling the generation of tailored spectral libraries in minutes rather than days [8].

This tool is particularly valuable for lipid identification because lipids have a modular construction—consisting of conserved headgroups and variable-length fatty acyl chains—that leads to predictable, class-specific fragmentation patterns. Library Forge exploits this property to learn fragmentation pathways directly from data, increasing lipid identification confidence across different instrumental platforms [8].

Key Concepts: Lipid Fragmentation and Identification

The Modular Nature of Lipids

Most lipid structures can be defined as a combination of a fixed number of variable-length hydrocarbon chains attached to a constant chemical moiety (e.g., a headgroup). This structure constrains the possible fragment types to a limited set [8]:

- Constant m/z fragments or neutral losses (typically related to the headgroup)

- Variable m/z fragments or neutral losses (related to the loss of one or more side chains)

The Library Forge Algorithm Workflow

Library Forge processes putatively identified MS/MS spectra through several key steps [8]:

- Spectral Pre-processing: High signal-to-noise (S/N) spectra are extracted, scaled to base peak intensity, and low-intensity fragments are filtered out.

- Consensus Spectrum Generation: Multiple MS/MS spectra with the same identification are clustered, and a single high-quality consensus spectrum is created from the median m/z and relative intensity of shared fragments.

- Annotation Spectrum Generation: An adaptive set of m/z offsets is applied to each consensus spectrum to generate "annotation spectra." This transformation makes spectral peaks from the same fragmentation pathway isobaric.

- Rule Extraction: Annotation spectra from the same lipid class and adduct are compared to determine the set of conserved fragmentation rules.

- In-Silico Library Generation: The derived rules are applied to a database of theoretical lipid species to generate a comprehensive in-silico library.

Table: Key Lipid Categories and Examples (based on LipidMaps classification) [29]

| Category | Abbreviation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acyls | FA | Oleic acid |

| Glycerolipids | GL | 1-hexadecanoyl-2-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycerol |

| Glycerophospholipids | GP | 1-hexadecanoyl-2-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| Sphingolipids | SP | N-(tetradecanoyl)-sphing-4-enine |

| Sterol Lipids | ST | Cholest-5-en-3β-ol |

Library Forge Data Processing Workflow

Experimental Protocol: Creating a Spectral Library with Library Forge

Materials and Reagents

- Lipid Reference Standards: Purchase from commercial suppliers (e.g., Avanti Polar Lipids). Used for library development and validation [8].

- Complex Lipid Extracts: For example, from HAP1 cells or the NIST 1950 Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma standard [8].

- Extraction Solvents: Chloroform (CHCl₃), Methanol (MeOH), Acetonitrile (ACN), Isopropanol (IPA) [8].

- Mobile Phase Additives: e.g., 10 mM ammonium acetate in ACN/Hâ‚‚O with acetic acid [8].

Sample Preparation and LC-MS/MS Acquisition

- Lipid Extraction: Add cold CHCl₃/MeOH (1:1, v/v) to the sample (e.g., cell pellet or plasma aliquot). Vortex, add HCl, vortex again, and centrifuge to separate phases [8].

- Reconstitution: Transfer the organic phase, dry under argon, and reconstitute the lipid-containing residue in ACN/IPA/Hâ‚‚O (65:30:5, v/v/v) [8].

- Chromatographic Separation: Use a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., ACQUITY CSH C18). Employ a binary mobile phase system with appropriate additives for lipid separation [8].

- Mass Spectrometry: Couple the LC system to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Scientific Q Exactive HF). Acquire data in both positive and negative polarity modes using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) [8].

Data Processing with Library Forge in LipiDex

- Convert Data: Use Proteowizard to convert acquired MS/MS spectra to MGF format [8].

- Obtain Putative Identifications: Generate an initial set of lipid identifications by searching spectra against a pre-existing spectral library (e.g., LipiDex HCD Acetate library or LipidBlast) [8].

- Run Library Forge: Feed these putative identifications into Library Forge to execute its algorithm for rule derivation and in-silico library generation. Key parameters (e.g., S/N threshold) are user-defined [8].

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Reference Standards | Library validation and development; structural confirmation | Avanti Polar Lipids; Sciex Internal Standards Kit |

| NIST 1950 SRM | Standard reference material for method validation | Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma |

| Chromatography Column | Separation of complex lipid mixtures | ACQUITY CSH C18 (2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm) |

| Ammonium Acetate | Mobile phase additive; promotes ionization | 10 mM in ACN/Hâ‚‚O or IPA/ACN |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer | Accurate mass and MS/MS fragmentation measurement | Q Exactive HF; Orbitrap Fusion Lumos |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

1. Problem: Poor Spectral Quality or Low-Signal-to-Noise Ratio

- Potential Cause: Insufficient lipid concentration or ion suppression.

- Solution: Check the extraction efficiency and potentially concentrate the sample further. Optimize the LC gradient to separate lipids more effectively, reducing co-elution and ion suppression.

- Prevention: Ensure proper sample preparation and use internal standards to monitor recovery and ionization efficiency.

2. Problem: Library Forge Fails to Derive Fragmentation Rules

- Potential Cause: The initial set of putative identifications from the pre-existing library is of low confidence or incorrect.

- Solution: Manually curate a subset of high-quality, confident identifications to serve as the input seed for Library Forge. Visually inspect spectra to confirm key fragment ions are present.

- Prevention: Use a well-curated, instrument-specific library for the initial search where possible.

3. Problem: Derived Rules are Too Restrictive or Do Not Generalize

- Potential Cause: The input data set lacks diversity in lipid chain lengths and classes, or contains too many low-abundance species.

- Solution: Increase the diversity of lipid reference standards used for rule derivation. Adjust the algorithm's parameters, such as relaxing the consensus threshold for accepting a fragmentation rule.

- Prevention: Use a complex lipid extract from a relevant biological source (e.g., human plasma, diverse cell lines) in addition to pure standards to capture a wider range of lipid structures.

4. Problem: Low Confidence in Final Lipid Identifications

- Potential Cause: The in-silico spectra generated from the rules do not adequately match the experimental data from your specific instrument.

- Solution: Use the

-ms-high-contrast-adjust: none;CSS property or similar platform-specific commands to ensure the OS does not override your defined styles in high-contrast mode, which can be analogous to ensuring your spectral processing parameters are correctly set and not being overridden by default settings [30]. Supplement the in-silico library with a small set of empirically validated spectra from standards run on your own instrument to "anchor" the identifications. - Prevention: Validate the generated library by running a set of known standards not used in the library creation process and check the spectral similarity scores.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does Library Forge differ from other in-silico library generation tools like LipidBlast? A1: While LipidBlast uses extensively curated, expert-defined fragmentation rules aimed for platform independence, Library Forge uses a data-driven approach. It learns the fragmentation rules and their associated relative intensities directly from experimental data provided by the user, creating a tailored library that reflects the specific conditions of your LC-MS/MS setup and fragmentation technique [8].

Q2: Can Library Forge handle data from any lipid class? A2: Library Forge is designed to work with lipids that have a modular construction containing variable-length carbon chains. It may not be suitable for lipids that do not contain such chains (e.g., some prostaglandins or polyketides) or for lipid fragments whose formation depends on specific, non-modular structural features [8].

Q3: What are the minimum computational requirements for running Library Forge within LipiDex? A3: The specific computational requirements (RAM, CPU) are not detailed in the search results. However, as Library Forge processes high-resolution MS/MS data and performs multiple comparisons across spectra, a modern computer with sufficient memory (likely 16GB RAM or more) is recommended for efficient processing of large datasets.

Q4: How can I validate the accuracy of a spectral library created with Library Forge? A4: The library should be validated using heavy isotope-labeled lipid standards and well-characterized standard reference materials (SRM) like the NIST 1950 [8]. The identification confidence is quantified by a modified dot product score (ranging from 0 to 1000) that measures the similarity between experimental and in-silico spectra [8].

Q5: My laboratory uses a different fragmentation technique (e.g., CID instead of HCD). Can I still use Library Forge? A5: Yes. A key advantage of Library Forge is its ability to learn fragmentation patterns from the data it is given. By providing it with MS/MS spectra generated using your specific dissociation technique (CID, HCD, etc.), it will derive rules specific to that technique, making it highly adaptable [8].

Modular Lipid Structure and Fragment Types

In the context of lipid species identification research using MS/MS fragmentation patterns, liquid chromatography (LC) separation provides a critical orthogonal dimension of information. Retention time (RT) serves as a molecular filter, narrowing down the pool of potential compound matches that would otherwise be overwhelming if MS data alone were used [31]. However, accurate lipid identification in untargeted lipidomics remains challenging due to the diversity of fatty acid chains and the prevalence of unsaturated bonds [32]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a crucial tool to address this challenge, enabling the development of accurate RT prediction models that enhance confidence in lipid annotation and minimize identification errors [32] [33].

Machine Learning Approaches for RT Prediction

Key Algorithms and Workflows

Various machine learning algorithms have been successfully applied to retention time prediction for lipids and small molecules. Research demonstrates that Random Forest (RF) models can achieve high correlation coefficients of 0.998 and 0.990 for training and test sets respectively, with mean absolute error (MAE) values of 0.107 and 0.240 minutes [32] [33]. For specialized applications such as sphingolipid analysis, lasso (alpha = 0.001) and ridge regression (alpha = 0.4) have shown exceptional performance for ceramide and sphingomyelin lipid species respectively, with R² values exceeding 0.9 and root mean squared error (RMSE) values below 0.25 [34].

The following workflow illustrates the typical process for developing and applying ML-based RT prediction models in lipidomics:

Molecular Descriptors and Features

The performance of ML models heavily depends on the molecular representations used as input features:

Molecular descriptors include constitutional descriptors (0D) such as counts of carbon (nC), hydrogen (nH), nitrogen (nN), oxygen (nO), phosphorus (nP), sulfur (nS), fluorine (nF), chlorine (nCl), bromine (nBr), and iodine (nI) atoms [35]. Studies comparing molecular descriptors and molecular fingerprints found that molecular descriptors consistently outperformed molecular fingerprints across all datasets when using Random Forest for model construction [33].

Molecular fingerprints encode structural information as bit vectors representing the presence or absence of specific substructures or chemical features [32].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of various ML approaches for RT prediction reported in recent studies:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML-Based Retention Time Prediction Models

| Model/Algorithm | Application Focus | Correlation (R²) | Mean Absolute Error | Root Mean Squared Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest [32] [33] | General lipids | 0.990 (test set) | 0.240 min (test set) | - |

| Lasso Regression [34] | Ceramide lipids | 0.930 | - | 0.091 |

| Ridge Regression [34] | Sphingomyelin lipids | 0.928 | - | 0.178 |

| Graph Neural Network [36] | Small molecules | - | 2.48 s | - |

| Support Vector Regression [35] | Pesticides | 0.63 (test set) | - | 1.11 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for Model Development

A proven workflow for developing ML-based RT prediction models involves these key steps:

Dataset Preparation: Collect experimental RT data from LC-MS analyses. A typical dataset might include 286 lipids for training and 142 for testing, generated using UHPLC systems with reversed-phase columns (e.g., BEH C8 column, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) with total run times of 20 minutes operating in both positive and negative ion modes [32].

Data Division: Split data into training and test sets in a 2:1 ratio, applying K-fold cross-validation (K = 10) to the training set for parameter optimization [32].

Feature Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors or fingerprints for all compounds in the dataset. For lipid analysis, this may include structural characteristics like sphingoid backbone type, fatty acyl chain length, and degree of unsaturation [34].

Model Training: Train multiple ML algorithms (RF, SVR, ANN) and compare their performance using metrics such as R², MAE, and RMSE.

Model Validation: Conduct external validation using independent datasets not used in training, with performance benchmarks of R² = 0.991 and MAE = 0.241 minutes demonstrating robust generalization [33].

LC-MS/MS Conditions for Lipid Analysis

For optimal results in lipidomics research, the following LC-MS/MS conditions are recommended:

Chromatography: Reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) with C8 or C18 columns (e.g., ACQUITY CSH C18 column, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) maintained at 50°C [8].

Mobile Phase: For positive ion mode, mobile phase A composed of 10 mM ammonium acetate in ACN/H₂O (70:30, v/v) containing 250 μL/L acetic acid; mobile phase B composed of 10 mM ammonium acetate in IPA/ACN (90:10, v/v) with the same additives [8].

Mass Spectrometry: High-resolution mass spectrometers such as Q Exactive HF or Orbitrap Fusion Lumos with HESI heated ESI source, acquiring data in both positive and negative polarity mode during sequential injections [8].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my ML model show excellent training performance but poor performance on new data?

This typically indicates overfitting. Implement k-fold cross-validation (e.g., K=10) during training and ensure your training set is sufficiently large and diverse. Studies show that model performance increases with training set size, with optimal results achieved with 9 datasets for ceramides and 6 for sphingomyelins [34]. Also consider using simpler models or regularization techniques like lasso or ridge regression [34].

Q2: How can I transfer RT predictions between different chromatographic systems?

Employ a linear retention time calibration method. Research has established a linear relationship to adjust retention times between different chromatographic systems (CSs), enabling the transfer of retention times from an old CS to a new one with the aid of the ML model [32]. This approach provides an effective solution for accurately predicting retention times regardless of chromatographic conditions.

Q3: What are the minimum data requirements for building a custom RT prediction model?

While requirements vary by application, successful models for sphingolipid analysis have been built with sequentially increased training data, achieving acceptable performance (R² > 0.9, RMSE < 0.25) with 6-9 datasets containing various molecular features [34]. For general small molecules, models trained on 20,000 data points have shown good predictive capability [36].

Q4: How can I distinguish between isomeric lipids with identical fragmentation patterns?

Combine RT prediction with MS/MS data. ReTimeML has demonstrated the capacity to resolve ion interferences and guide accurate annotations for expressional differences in complex biological samples by incorporating RT information alongside mass and fragmentation data [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High prediction variance across different lipid classes.

Solution: Develop class-specific models rather than a universal model. Research shows that separate models for ceramides and sphingomyelins outperform generalized approaches [34]. This accounts for class-specific retention behaviors and fragmentation patterns.

Problem: Inconsistent RT measurements affecting model accuracy.

Solution: Implement rigorous system suitability testing and standardize LC conditions. Use reference standards as internal calibrators to normalize RT measurements across runs [34]. Also ensure mobile phases are freshly prepared and columns are properly conditioned.

Problem: Limited commercial standards for model training.

Solution: Leverage in silico fragmentation tools like Library Forge, which generates tailored lipid mass spectral libraries from experimental data with minimal user input, reducing dependency on commercial standards [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LC-MS Lipidomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | RT calibration and model training | Avanti Polar Lipids; System Suitability Lipid Classes Light Mix (Sciex) [8] [34] |

| LC Columns | Chromatographic separation | Reversed-phase (e.g., BEH C8, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm; ACQUITY CSH C18) [32] [8] |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Improve separation and ionization | 10 mM ammonium acetate with 250 μL/L acetic acid [8] |

| Internal Standards | Quantification and RT normalization | Deuterated compounds; Internal Standards Kit for Lipidyzer Platform [8] [34] |

| Extraction Solvents | Lipid isolation from biological samples | CHCl₃/MeOH (1:1, v/v) for sample preparation [8] |

| Software Tools | Data processing and analysis | LipiDex, RT-Pred, ReTimeML, LipidSearch [31] [8] [34] |

| DETD-35 | DETD-35, MF:C27H24O6, MW:444.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fak-IN-22 | Fak-IN-22, MF:C21H16F3N5O2, MW:427.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Machine learning-based retention time prediction represents a powerful approach to enhance lipid identification in LC-MS-based analyses. By integrating accurate RT predictions with MS/MS fragmentation data, researchers can significantly improve confidence in lipid annotation, particularly for challenging isomeric species. The continued development of web-based tools like RT-Pred and ReTimeML [31] [34], alongside advances in molecular descriptor calculation and machine learning algorithms, promises to further streamline lipidomics workflows and accelerate discoveries in biomedical research, drug development, and biomarker identification.

The untargeted lipidomics workflow using Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is a powerful, high-sensitivity approach for comprehensively identifying and quantifying hundreds to thousands of lipid species in a biological sample. [37] [38] Success hinges on meticulous experimental design and sample preparation to minimize technical artifacts and biological confounding factors.

Key Considerations for Study Design

- Batch Layout and Randomization: LC-MS experiments are typically limited to batch sizes of 48–96 samples. It is critical to distribute samples from different experimental groups across all batches to avoid confounding the factor of interest with batch-specific technical effects. Samples should be randomized within each batch. [37]

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: A pooled QC sample, created by combining a small aliquot of every sample, should be analyzed repeatedly throughout the run. QC samples are used to:

- Condition the column with several initial injections.

- Monitor instrument stability and reproducibility by being injected after every ten samples and at the end of the run. [37]

- Blank Samples: Blank extraction samples (containing no biological material) should be processed alongside experimental samples. These are essential for identifying and filtering out peaks resulting from solvent impurities or laboratory contamination. [37]

- Internal Standards: Isotope-labeled internal standards should be added to the samples as early as possible in the extraction process. These standards enable correction for variations in sample preparation, injection, and ionization efficiency. [37] [38]

The following diagram illustrates the major stages of the untargeted lipidomics workflow, from sample preparation to lipid identification:

Troubleshooting Common LC-MS/MS Issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do you optimize LC-MS/MS for lipidomics analysis? Optimization requires attention to both chromatography and mass spectrometry. Select a stationary phase (e.g., C8 or C18 column) suitable for separating diverse lipid classes. Fine-tune the mobile phase composition and gradient elution to improve peak resolution. On the MS side, optimize ion source parameters (e.g., gas temperatures, voltages) and collision energies to maximize sensitivity and produce informative fragments for lipid identification. [39]

2. What is the role of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in lipidomics? MS/MS is pivotal for structural characterization. A specific precursor ion is isolated and fragmented, producing product ions that reveal structural information. For example, fragmentation of glycerophospholipids like phosphatidylcholine (PC) produces a characteristic phosphocholine headgroup ion at m/z 184, while phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) exhibits a neutral loss of the ethanolamine group. These patterns are diagnostic for identifying lipid classes and their fatty acyl chains. [39]