Decoding the lncRNA-mRNA Regulatory Network in Liver Cancer: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), interacting with mRNAs through complex networks to drive tumor initiation, progression, and therapy resistance.

Decoding the lncRNA-mRNA Regulatory Network in Liver Cancer: From Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), interacting with mRNAs through complex networks to drive tumor initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. This article synthesizes current research on lncRNA-mRNA interactions, exploring their foundational biology, methodological approaches for network analysis, challenges in therapeutic targeting, and validation strategies. We examine how these networks influence key oncogenic pathways—including PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MAPK, Wnt/β-catenin, and autophagy—and discuss their emerging roles as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. By integrating findings from transcriptomic analyses, functional studies, and clinical validation efforts, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and targeting lncRNA-mRNA networks in liver cancer precision medicine.

The Landscape of lncRNA-mRNA Crosstalk in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Defining lncRNA Classification and Molecular Functions in Liver Physiology

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as RNA transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding capacity, have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression and liver physiology [1] [2]. The liver exhibits a unique repertoire of lncRNAs that coordinate essential biological processes, including metabolic homeostasis, stress response, and cell proliferation [1]. Dysregulation of these molecules contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of liver diseases, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3] [4]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for lncRNA classification, molecular mechanisms, and experimental methodologies within the context of liver physiology and pathobiology, with specific emphasis on their roles in lncRNA-mRNA regulatory networks in liver cancer research.

LncRNA Classification and Genomic Origins

LncRNAs can be systematically categorized based on their genomic context relative to protein-coding genes. This classification provides insights into their potential regulatory relationships with neighboring genes and their biogenesis.

Table 1: Classification of LncRNAs by Genomic Position

| Classification Type | Genomic Position Relative to Protein-Coding Genes | Example in Liver Physiology |

|---|---|---|

| Intergenic (lincRNA) | Located between protein-coding genes | NEAT1, involved in paraspeckle formation and stress response [5] |

| Intronic | Derived entirely from within an intron | |

| Sense | Overlaps exons of protein-coding gene on same strand | |

| Antisense | Overlaps exons of protein-coding gene on opposite strand | |

| Bidirectional | Transcribed from shared promoter region in opposite direction | |

| Enhancer-associated | Transcribed from enhancer regions |

Beyond positional classification, a functionally significant category is liver-specific lncRNAs, which exhibit predominant or exclusive expression in hepatic tissue and perform tissue-specific functions [6]. A systematic analysis of the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) dataset has identified several such lncRNAs, including FAM99B, which is expressed almost exclusively in the liver and frequently demonstrates loss of expression in liver cancer, often functioning as tumor suppressors [6].

Molecular Functions and Mechanisms of Action

The functional capacity of a lncRNA is intimately tied to its subcellular localization. Nuclear-enriched lncRNAs predominantly regulate transcription and chromatin organization, while cytoplasmic lncRNAs influence mRNA stability and translation [1].

Key Functional Mechanisms

Transcriptional Regulation and Chromatin Remodeling: Nuclear lncRNAs can recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci to alter the epigenetic landscape. For example, they can facilitate histone modifications such as H3K4me3 (associated with activation) or H3K27me3 (associated with repression) at gene promoters [2]. The lncRNA FAM99B, which is predominantly nuclear, interacts with the RNA helicase DDX21 and promotes its nuclear export, ultimately inhibiting ribosome biogenesis and suppressing HCC progression [6].

Post-Transcriptional Regulation (ceRNA Network): Many cytoplasmic lncRNAs function as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or "molecular sponges." They sequester microRNAs (miRNAs), thereby preventing these miRNAs from binding and repressing their target mRNAs. The well-characterized oncogenic lncRNA HULC promotes HCC progression partly by acting as a ceRNA for miR-372, alleviating the miRNA's repression on its targets and creating a positive feedback loop that further enhances HULC expression [2].

Protein Interactions and Scaffolding: LncRNAs can serve as modular scaffolds to bring multiple proteins together into functional complexes. NEAT1 is a critical architectural component of nuclear paraspeckles, where it acts as a scaffold for proteins like PSPC1, SFPQ/PSF, and NONO, thereby influencing gene expression by retaining specific RNAs in the nucleus [5].

Regulation of Enzyme Activity and Signaling Pathways: LncRNAs can directly interact with and modulate the activity of metabolic enzymes. For instance, HULC has been shown to bind to and increase the phosphorylation of key glycolytic enzymes lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), thereby enhancing the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) in HCC cells to support tumor growth [2].

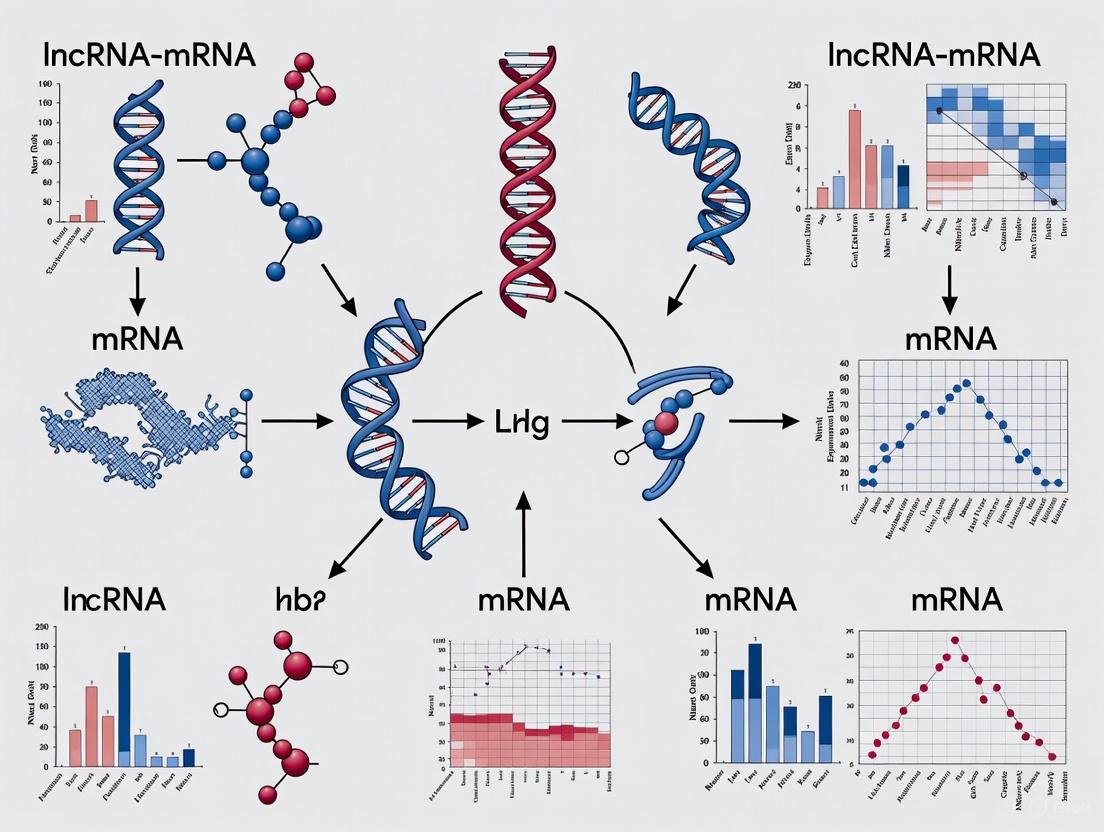

The following diagram illustrates the primary molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs based on their subcellular localization:

Key Liver LncRNAs and Their Functional Roles

Specific lncRNAs have been identified as critical players in maintaining liver homeostasis, and their dysregulation is a hallmark of liver disease, especially HCC.

Table 2: Key LncRNAs in Liver Physiology and Pathophysiology

| LncRNA | Expression in HCC | Primary Function | Molecular Mechanism | Role in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | Upregulated [2] | Promotes proliferation, metabolism, metastasis | ceRNA for miR-372; enhances CREB signaling; binds LDHA/PKM2 [2] | Oncogene |

| FAM99B | Downregulated [6] | Inhibits proliferation and metastasis | Binds DDX21; inhibits ribosome biogenesis [6] | Tumor Suppressor |

| NEAT1 | Context-dependent | Stress response, paraspeckle formation | Scaffold for paraspeckle proteins; ceRNA for multiple miRs [5] | Oncogene / Context-dependent |

| MEG3 | Downregulated [1] | Promotes apoptosis, inhibits proliferation | Recruits chromatin modifiers; interacts with p53 protein [1] | Tumor Suppressor |

LncRNA-mRNA Regulatory Networks in Liver Cancer

LncRNAs do not function in isolation but are embedded in complex, interconnected regulatory networks with mRNAs, miRNAs, and proteins. Investigating these networks is crucial for understanding the systems-level impact of lncRNAs in liver carcinogenesis.

Network Analysis Methodology

The construction of lncRNA-mRNA regulatory networks typically involves integrated transcriptomic and bioinformatic approaches:

- High-Throughput Sequencing: RNA-Seq is performed on patient-derived samples (e.g., HCC tissues vs. normal adjacent tissue) or experimental models to identify differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs [7] [8].

- Target Prediction:

- Cis-regulation: Protein-coding genes within a defined genomic window (e.g., 100 kb upstream and downstream) of a lncRNA are predicted as potential cis-targets [8].

- Trans-regulation: Co-expression analysis across samples is performed. LncRNA-mRNA pairs with a strong positive or negative correlation (e.g., |Pearson r| > 0.9) are identified as potential trans-regulatory pairs [8].

- Competitive Endogenous RNA (ceRNA) Network Construction: For a given lncRNA, miRNAs with complementary binding sites are predicted. Shared miRNAs that also bind to an mRNA target are identified, forming a lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA axis. For example, the network involving HULC, miR-675, and its target PKM2 has been validated in liver cancer stem cells [2].

- Functional Enrichment and Network Visualization: Differentially expressed mRNAs and the predicted target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs are subjected to GO and KEGG pathway analysis. Networks are visualized using software like Cytoscape, and key hub genes can be identified using plugins like CytoHubba [7] [8].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for constructing and analyzing lncRNA-mRNA regulatory networks:

Experimental Protocols for lncRNA Functional Characterization

Protocol: Extracellular Vesicle (EV)-Derived lncRNA Isolation and Sequencing

EVs are a promising source of disease-specific lncRNAs for liquid biopsy applications [7].

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect fasting venous blood. For serum, use vacuum tubes with inert separation gel and procoagulant. For plasma, use tubes with EDTA anticoagulant. Centrifuge samples and aliquot serum/plasma, storing at -80°C.

- EV Isolation via Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC):

- Thaw serum/plasma samples and pre-filter through a 0.8 μm filter.

- Load the sample onto a gel-permeation column (e.g., ES911).

- Collect the eluent from specific tube fractions (e.g., tubes 7-9) known to contain EVs.

- Concentrate the EV-containing eluent using a 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off ultrafiltration tube.

- EV Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Use a Nanoflow Analyzer to determine EV particle size distribution and concentration.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualize EV morphology by staining with uranyl acetate.

- Western Blot: Confirm the presence of EV marker proteins (e.g., TSG101, Alix, CD9) and the absence of negative control proteins (e.g., Calnexin).

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Isolate total RNA from EVs using a commercial RNA Purification Kit.

- Deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from the total RNA to enrich for lncRNAs and other non-rRNA species.

- Construct cDNA libraries using standard protocols (fragmentation, adapter ligation, PCR amplification).

- Perform high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq 6000).

Protocol: Functional Validation via Gene Knockdown and Phenotypic Assays

- LncRNA Knockdown:

- Design: Synthesize small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) complementary to the target lncRNA sequence. For in vivo delivery, conjugate ASOs with N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) for targeted liver uptake.

- Transfection: Transfect siRNAs/ASOs into relevant HCC cell lines (e.g., Huh7, HepG2) using lipid-based transfection reagents. For stable knockdown, use lentiviral vectors expressing short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs).

- Phenotypic Assays:

- Proliferation: Perform Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-transfection. Conduct colony formation assays by staining fixed colonies with crystal violet after 10-14 days.

- Migration/Invasion: Use Transwell chambers coated with (invasion) or without (migration) Matrigel. Seed transfected cells in the upper chamber and count cells that migrate to the lower chamber after 24-48 hours.

- In Vivo Tumorigenesis: Subcutaneously inject control and lncRNA-knockdown HCC cells into the flanks of immunodeficient mice. Monitor tumor volume and weight over 4-6 weeks. For metastasis models, perform intrahepatic or tail vein injections.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for lncRNA Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns | Isolation of intact EVs from biofluids | Enrichment of EV-associated lncRNAs from patient serum [7] |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Enrichment for non-coding RNAs prior to sequencing | Preparation of RNA-Seq libraries for comprehensive lncRNA transcriptome analysis [7] [8] |

| GalNAc-conjugated ASOs | Targeted delivery of therapeutic oligonucleotides to hepatocytes | In vivo knockdown of oncogenic lncRNAs like HULC in preclinical models [6] |

| RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) Kits | Identification of lncRNA-protein interactions | Validation of FAM99B-DDX21 protein interaction [6] |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) | High-throughput assessment of cell proliferation | Evaluation of proliferation changes after lncRNA FAM99B overexpression [6] |

| Transwell Assay Plates | Quantification of cell migration and invasion | Measurement of metastatic potential following HULC knockdown [2] |

| 2-amino-N-(3-ethoxypropyl)benzamide | 2-amino-N-(3-ethoxypropyl)benzamide, CAS:923184-33-2, MF:C12H18N2O2, MW:222.288 | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-3-pyridazinol | 6-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-3-pyridazinol | 6-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-3-pyridazinol is a pyridazinone-based compound for research use only (RUO). It is for laboratory studies and not for human or veterinary use. Explore its potential as a vasodilator. |

Concluding Perspectives

The systematic classification and functional characterization of lncRNAs have unveiled a complex layer of regulation critical to liver physiology and carcinogenesis. The integration of multi-omics data, particularly through the construction of lncRNA-mRNA regulatory networks, provides a powerful framework for identifying key drivers of HCC. Future research will focus on translating this knowledge into clinical applications, leveraging liver-specific lncRNAs like FAM99B for novel RNA-based therapeutics and exploiting circulating EV-derived lncRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of liver disease [7] [6]. Overcoming challenges in therapeutic delivery, such as through GalNAc-conjugation, represents a promising path toward targeting the lncRNA-autophagy axis and other critical regulatory networks in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Key lncRNA-mRNA Regulatory Axes in HCC Pathogenesis

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a significant global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer death [9]. The poor prognosis of HCC patients stems from asymptomatic early stages, limited therapeutic options, frequent tumor metastasis, and high recurrence rates [9] [10]. In recent decades, research on the molecular mechanisms of HCC has primarily focused on protein-encoding oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. However, with advancements in deep sequencing technologies, scientific attention has shifted to non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), particularly long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [9].

LncRNAs are functionally defined as RNA molecules exceeding 200 nucleotides in length that lack protein-coding capacity [9] [11]. These molecules represent the majority of ncRNAs in the human genome and exhibit complex regulatory functions through interactions with DNA, RNA, and proteins. According to genomic context, lncRNAs are classified into several categories: long intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs), intron-derived lncRNAs, bidirectional lncRNAs, and natural antisense transcripts [9]. Their functional mechanisms include: (1) serving as molecular signals in response to various stimuli; (2) guiding histone modification complexes to chromatin; (3) acting as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) that sequester miRNAs; and (4) scaffolding for protein complex formation [9]. The dysregulation of specific lncRNAs has been implicated in multiple aspects of HCC pathogenesis, including tumor angiogenesis, cell proliferation, vascular invasion, and metastasis [9] [10].

Fundamental Mechanisms of lncRNA-mRNA Regulation in HCC

Epigenetic, Transcriptional, and Post-Transcriptional Control

LncRNAs regulate gene expression through multifaceted mechanisms operating at epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels. At the epigenetic level, lncRNAs such as HOTAIR interact with polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to mediate histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3), leading to transcriptional repression of target genes [10]. In HCC tissues, HOTAIR overexpression correlates with poor tumor differentiation, metastasis, and early recurrence [10]. At the post-transcriptional level, lncRNAs function as miRNA sponges through the ceRNA mechanism. For instance, HULC acts as a ceRNA to adsorb and inhibit miR-372 activity, thereby relieving miR-372-mediated repression of its target gene PRKACB [9].

The subcellular localization of lncRNAs significantly influences their functional mechanisms. Nuclear-enriched lncRNAs (e.g., MALAT1, HOTAIR) predominantly regulate transcription and chromatin organization, while cytoplasmic lncRNAs (e.g., HULC) often function as miRNA sponges or modulate signaling pathways [11]. This compartmentalization enables lncRNAs to participate in diverse regulatory networks relevant to HCC pathogenesis.

The ceRNA Hypothesis: Cross-Regulatory Networks in HCC

The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis posits that lncRNAs can function as molecular sponges for miRNAs, thereby attenuating miRNA-mediated repression of target mRNAs. This cross-regulatory network creates a sophisticated layer of post-transcriptional regulation that significantly impacts HCC development and progression [12] [13]. Through this mechanism, relatively small changes in lncRNA expression can produce substantial effects on mRNA expression patterns and cellular phenotypes.

Table 1: Experimentally Validated ceRNA Axes in HCC Pathogenesis

| lncRNA | miRNA Sponge | Target mRNA | Functional Outcome in HCC | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNHG3 | miR-214-3p | ASF1B | Promotes recurrence and immune infiltration; correlates with poor DFS [12] | Dual-luciferase reporter assay, RT-qPCR, Flow cytometry [12] |

| H19 | miR-15b | CDC42/PAK1 | Stimulates proliferation via CDC42/PAK1 axis [11] | Functional assays in HCC cells [11] |

| linc-RoR | miR-145 | p70S6K1, PDK1, HIF-1α | Promotes self-renewal and proliferation under hypoxia [11] | Expression analysis, target validation [11] |

| HULC | miR-372 | PRKACB | Promotes hepatoma cell proliferation [9] | Expression correlation, functional studies [9] |

Clinically Significant lncRNA-mRNA Regulatory Axes in HCC

The SNHG3/miR-214-3p/ASF1B Axis in HCC Recurrence and Immune Regulation

The SNHG3/miR-214-3p/ASF1B axis represents a clinically significant regulatory network in HCC pathogenesis, particularly in tumor recurrence and immune regulation. Comprehensive analysis of datasets from GEO and TCGA revealed that SNHG3 and ASF1B are significantly overexpressed in HCC tissues from patients with recurrence [12]. Clinical correlation analysis demonstrated that these molecules are closely associated with HCC grade and stage, while survival analysis indicated their significant correlation with poor disease-free survival [12].

The molecular mechanism of this axis was experimentally validated through dual-luciferase reporter assays, which confirmed that both SNHG3 and ASF1B directly bind to miR-214-3p [12]. Functionally, SNHG3 acts as a molecular sponge for miR-214-3p, thereby inhibiting miR-214-3p activity and increasing ASF1B expression. This regulatory relationship creates a pro-tumorigenic circuit that promotes HCC recurrence through multiple mechanisms, including modulation of immune infiltration [12].

Table 2: Key lncRNA-mRNA Axes in HCC and Their Clinical Implications

| Regulatory Axis | Expression in HCC | Primary Functions | Clinical Significance | Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC/SPHK1 | Upregulated [9] [10] | Promotes angiogenesis via miR-107/E2F1/SPHK1 signaling [10] | Associated with TNM stage, intrahepatic metastases, recurrence [10] | Potential therapeutic target; detected in plasma [9] |

| MALAT1/HIF-2α | Upregulated [10] | Forms feedback loop promoting arsenite-induced carcinogenesis [10] | Prognostic for recurrence after liver transplant [10] | Inhibition increases sensitivity to apoptosis [10] |

| HOTAIR/MMP-9, VEGF | Upregulated [10] | Promotes migration, invasion, metastasis [10] | Correlates with poor differentiation, lymph node metastasis [10] | Independent prognostic factor [10] |

| H19/CDC42/PAK1 | Upregulated [11] | Stimulates proliferation via CDC42/PAK1 axis [11] | Induces drug resistance, promotes progression [10] [11] | Oncogenic role; potential therapeutic target [11] |

| MEG3/p53 | Downregulated [9] [10] | Interacts with p53 to enhance its activity [9] | Tumor-suppressive; downregulated in HBV-associated HCC [9] | Potential tumor suppressor to be therapeutically restored [9] |

ASF1B exhibits significant correlation with immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment. Experimental evidence demonstrates that ASF1B knockdown markedly inhibits the expression of immune-related markers including CD86, CD8, STAT1, STAT4, CD68, and PD-1 in HCC cells [12]. Furthermore, flow cytometry analysis confirmed that SNHG3 promotes PD-1 expression by regulating ASF1B, suggesting this axis may contribute to immune evasion mechanisms in HCC [12]. The identification of this regulatory network provides not only prognostic biomarkers but also potential targets for immunotherapy in HCC management.

The HULC/SPHK1 Axis in Angiogenesis and Metabolic Reprogramming

The Highly Up-regulated in Liver Cancer (HULC) lncRNA represents one of the first identified and most extensively characterized oncogenic lncRNAs in HCC. Located at chromosome 6p24.3 with a length of 500 nucleotides, HULC is specifically expressed in hepatocytes and highly upregulated in HCC tissues and plasma [9] [10]. Clinically, HULC abundance positively correlates with Edmondson grade and hepatitis B virus infection [9].

HULC promotes HCC progression through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming. Research by Lu et al. demonstrated a positive correlation between HULC levels and sphingosine kinase 1 (SPHK1) in HCC tissues, revealing that HULC promotes tumor angiogenesis via the miR-107/E2F1/SPHK1 signaling cascade [10]. Additionally, HULC contributes to abnormal lipid metabolism in hepatoma cells through a pathway involving miR-9, PPARA, and ACSL1 [10]. HULC also influences hepatocarcinogenesis by altering circadian rhythms through upregulation of the circadian oscillator CLOCK in hepatoma cells [10].

Beyond these mechanisms, HULC functions as a critical autophagy regulator in HCC. Experimental evidence indicates that ectopic HULC expression decreases P62 levels while increasing LC3 expression at the transcriptional level [9]. HULC activates LC3 through Sirt1 deacetylase, thereby increasing expression of autophagy-related genes including becline-1, ultimately accelerating malignant progression of hepatoma cells [9]. This multifaceted regulatory capacity establishes HULC as a central orchestrator of HCC pathogenesis through diverse molecular pathways.

The MALAT1/HIF-2α Feedback Loop in Carcinogenesis

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) is a nuclear-enriched lncRNA over 8000 nucleotides in length that originates from chromosome 11q13. MALAT1 is highly conserved across species and demonstrates significant overexpression in HCC tissues and cell lines [10]. Clinically, higher MALAT1 expression associates with shorter disease-free survival in HCC patients who have undergone liver transplantation, serving as an independent prognostic factor for HCC recurrence alongside tumor size and portal vein tumor thrombus [10].

A critical mechanism through which MALAT1 promotes HCC involves the formation of a positive feedback loop with hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α). Research by Luo et al. demonstrated that MALAT1 overexpression induced by arsenite exposure leads to disassociation of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein from HIF-2α, reducing VHL-mediated HIF-2α ubiquitination and resulting in HIF-2α accumulation [10]. Consequently, HIF-2α transcriptionally regulates MALAT1, establishing a MALAT1/HIF-2α feedback loop that drives arsenite-related carcinogenesis [10].

MALAT1 also contributes to liver fibrosis progression, a known precursor to HCC development, through mediation of SIRT1 expression and function [10]. The multifaceted nature of MALAT1 regulatory networks underscores its significance as both a biomarker and therapeutic target in HCC pathogenesis.

Methodological Framework for lncRNA-mRNA Network Analysis

Integrated Bioinformatics Approaches for Axis Identification

The identification and validation of lncRNA-mRNA regulatory axes in HCC employs sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines integrating multiple data sources and analytical approaches. A representative methodology involves several sequential phases [12]:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: RNA sequencing data and clinical information are obtained from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-LIHC dataset and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The TCGA-LIHC dataset contains transcriptomic data from 375 HCC tissues and 49 adjacent normal liver tissues, while relevant GEO datasets (e.g., GSE69164, GSE77509, GSE76903) provide additional expression profiles [12].

Differential Expression Analysis: Differentially expressed lncRNAs (DELs), miRNAs (DEMIs), and mRNAs (DEMs) between HCC tissues and normal controls are identified using specialized R packages. For RNA sequencing count data from TCGA, the "DESeq2" package is employed with screening criteria of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 and |log2 fold change| ≥ 2 [12]. For microarray data from GEO datasets, the "limma" package is utilized with similar stringency thresholds.

ceRNA Network Construction: Experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions are predicted using miRTarBase, while lncRNA-miRNA interactions are identified through the starBase database [12]. Integration of these interactions with differentially expressed RNAs enables construction of preliminary ceRNA networks, which are visualized using Cytoscape software.

Hub Gene Selection and Validation: Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks are constructed using the STRING database, with nodes of degree ≥35 typically selected as hub genes [12]. Clinical correlation and survival analyses are performed to identify relapse-related genes, followed by experimental validation using techniques such as dual-luciferase reporter assays and quantitative PCR.

Experimental Validation of Regulatory Axes

The functional validation of predicted lncRNA-mRNA regulatory axes employs a multifaceted experimental approach centered on the dual-luciferase reporter assay system [12] [13]. This methodology provides critical evidence for direct molecular interactions within proposed regulatory networks.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay: This technique involves cloning wild-type or mutant sequences of the lncRNA or mRNA 3'UTR containing predicted miRNA binding sites into a reporter vector downstream of the luciferase gene [12]. HCC cells are then co-transfected with the reporter construct and miRNA mimics or inhibitors. Following transfection, luciferase activity is measured using specialized detection systems. A significant decrease in luciferase activity in cells transfected with wild-type constructs and miRNA mimics indicates direct binding, while mutant constructs serve as negative controls [12].

Functional Validation Approaches: Additional experimental techniques include:

- Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR): Validates expression patterns of lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs in HCC tissues and cell lines using SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistries [14] [15]. Data analysis typically employs the 2−ΔΔCt method with normalization to housekeeping genes such as GAPDH or β-actin [14] [15].

- In Vitro Functional Assays: Includes siRNA-mediated knockdown or overexpression studies followed by assessments of proliferation (CCK-8, colony formation), apoptosis (flow cytometry), migration/invasion (transwell assays), and autophagy (LC3 puncta formation, p62 degradation) [16].

- Immune Infiltration Analysis: Utilizes databases such as TIMER to correlate gene expression with immune cell infiltration, validated through flow cytometry analysis of immune markers [12].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for lncRNA-mRNA Axis Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | TCGA-LIHC, GEO datasets | Data acquisition for differential expression analysis | 375 HCC tissues vs. 49 normal liver tissues [12] |

| Analysis Tools | R packages (DESeq2, limma), STRING, Cytoscape | Bioinformatics analysis and visualization | Differential expression, PPI network construction [12] |

| Prediction Databases | miRTarBase, starBase, lncRNAdb | Prediction of RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions | Experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions [17] [12] |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | SYBR Green Master Mix, TaqMan assays, specific primers | Expression validation | LINC00152, UCA1, GAS5 quantification [14] |

| Luciferase Assay System | Dual-Luciferase Reporter vectors, miRNA mimics/inhibitors | Validation of direct binding interactions | SNHG3-miR-214-3p-ASF1B validation [12] |

| Cell Culture Models | HepG2, Huh7, primary HCC cells | Functional validation of regulatory axes | Proliferation, apoptosis, invasion assays [10] |

Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Implications

Clinical Applications as Biomarkers

The distinctive expression patterns of lncRNAs in HCC tissues and biological fluids position them as promising biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. Numerous studies have demonstrated the diagnostic potential of lncRNA panels in distinguishing HCC patients from healthy controls or individuals with benign liver conditions.

Research investigating plasma levels of four lncRNAs (LINC00152, LINC00853, UCA1, and GAS5) in a cohort of 52 HCC patients and 30 age-matched controls revealed moderate individual diagnostic accuracy, with sensitivity and specificity ranging from 60% to 83% and 53% to 67%, respectively [14]. However, machine learning approaches integrating these lncRNAs with conventional laboratory parameters demonstrated superior performance, achieving 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity for HCC detection [14]. This highlights the enhanced diagnostic power of multi-analyte panels compared to single lncRNA biomarkers.

The prognostic utility of lncRNAs is particularly valuable in clinical decision-making. For instance, a higher LINC00152 to GAS5 expression ratio significantly correlates with increased mortality risk, providing a potential stratification tool for identifying high-risk patients [14]. Similarly, MALAT1 expression serves as an independent prognostic factor for HCC recurrence after liver transplantation, particularly in patients with larger tumors (diameter >5 cm) [10]. These applications facilitate personalized treatment approaches based on individual molecular profiles.

Emerging Therapeutic Approaches

The strategic targeting of lncRNA-mRNA regulatory axes represents a promising frontier in HCC therapeutics. Several innovative approaches are currently under investigation:

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs): These chemically modified single-stranded DNA analogs specifically bind to complementary lncRNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing, triggering RNase H-mediated degradation of the target lncRNA [16]. ASOs can be further modified with cholesterol conjugates or nanoparticle formulations to enhance cellular uptake and stability in vivo.

Small Interfering RNAs (siRNAs): Synthetic double-stranded RNA molecules designed to target oncogenic lncRNAs for degradation via the RNA interference pathway [16]. Advances in delivery systems, including lipid nanoparticles and ligand-conjugated approaches, improve hepatocyte-specific targeting while minimizing off-target effects.

CRISPR/Cas9 Systems: Genome editing technology enables precise deletion or disruption of lncRNA genomic loci or promoter regions [16]. Catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional repressors (CRISPRi) or activators (CRISPRa) allows for epigenetic silencing or activation of lncRNA expression without altering DNA sequence.

Small Molecule Inhibitors: High-throughput screening approaches identify chemical compounds that disrupt specific lncRNA-protein or lncRNA-secondary structure interactions [16]. These compounds offer potential advantages in terms of bioavailability and pharmacokinetic properties compared to oligonucleotide-based therapies.

The therapeutic targeting of the lncRNA-autophagy axis presents particular promise, as several lncRNAs (including HULC) have been shown to modulate drug resistance by altering autophagic flux and associated molecular pathways [16]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that combining lncRNA-targeting approaches with conventional chemotherapeutic agents can resensitize resistant HCC cells, suggesting potential synergistic treatment strategies.

The comprehensive investigation of lncRNA-mRNA regulatory axes has substantially advanced our understanding of HCC pathogenesis at the molecular level. These complex networks influence critical cancer hallmarks including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppression, activation of invasion and metastasis, induction of angiogenesis, and metabolic reprogramming. The SNHG3/miR-214-3p/ASF1B, HULC/SPHK1, and MALAT1/HIF-2α axes represent particularly promising targets for diagnostic and therapeutic development.

Future research directions should prioritize the integration of multi-omics approaches to validate additional functional lncRNA-mRNA networks in HCC pathogenesis. The development of sophisticated delivery systems for lncRNA-targeting therapeutics remains a critical challenge requiring innovative solutions. Furthermore, prospective clinical studies validating the prognostic utility of lncRNA signatures in well-defined patient cohorts will be essential for translating these molecular discoveries into clinical practice.

As our understanding of lncRNA biology continues to evolve, these molecules will undoubtedly assume increasingly prominent roles as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in HCC management. The ongoing characterization of lncRNA-mRNA regulatory networks promises to unlock novel approaches for combating this devastating malignancy, ultimately improving outcomes for patients worldwide.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression in cancer biology, functioning through intricate networks with messenger RNAs (mRNAs). This technical review examines the current understanding of lncRNA-mRNA networks within three core signaling pathways—PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MAPK, and Wnt/β-catenin—with specific focus on their implications in liver cancer pathogenesis. We synthesize evidence from recent transcriptomic studies demonstrating how these regulatory networks influence critical oncogenic processes including cell proliferation, metastasis, metabolic reprogramming, and therapeutic resistance. The analysis incorporates experimental methodologies for network identification, functional validation techniques, and computational approaches that enable researchers to decipher these complex interactions. Additionally, we provide a curated toolkit of research reagents and resources to facilitate investigation of lncRNA-mRNA networks in liver cancer models, offering a foundation for developing novel diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies.

The complexity of cancer signaling pathways extends beyond protein-coding genes to encompass a vast regulatory architecture orchestrated by non-coding RNAs. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited protein-coding potential, represent a critical layer of regulation within oncogenic signaling networks [18]. These molecules exhibit precise spatial and temporal expression patterns and function through diverse mechanisms including chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, and post-transcriptional processing [19]. In hepatic malignancies, including hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and other liver cancer subtypes, lncRNAs are frequently dysregulated and contribute significantly to disease progression [4].

The integration of lncRNAs with core signaling pathways creates sophisticated regulatory circuits that both influence and are influenced by traditional oncogenic signaling. This review focuses specifically on the interplay between lncRNAs and three fundamentally important pathways in liver cancer: PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MAPK, and Wnt/β-catenin. Understanding these networks provides not only insights into liver cancer biology but also reveals potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. We present a comprehensive analysis of established methodologies for mapping these networks, summarize key experimental findings, and provide resources to advance research in this evolving field.

LncRNA-mRNA Networks in Core Signaling Pathways

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway Networks

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway represents a crucial intracellular signaling axis that maintains balance among various cellular physiological processes, including cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and survival [20]. Frequent dysregulation of this pathway occurs in gastrointestinal tumors, including hepatocellular carcinoma, where aberrant activation drives tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms [20]. LncRNAs modulate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway through diverse mechanisms, primarily by acting as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) that regulate miRNA expression and associated genes [20].

In the context of liver cancer, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activation requires the coordinated function of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) to integrate extra- and intracellular signals that promote protein synthesis, cell metabolism, growth, proliferation, apoptosis evasion, migration, and invasion [18]. The normal function of this axis can be disrupted by genetic and epigenetic alterations that induce increased pathway activity in abnormal cells. lncRNAs have been demonstrated to regulate this pathway at multiple nodal points, offering both diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities.

Table 1: Key lncRNAs Regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Cancer

| LncRNA | Expression in Cancer | Target/Mechanism | Functional Outcome | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPCART | Upregulated | Modulates AKT/mTORC1 pathway; regulates PDCD4 | Inhibits translation suppression; promotes proliferation | Prostate Cancer [21] |

| Multiple lncRNAs | Variably dysregulated | Act as ceRNAs for miRNAs targeting PI3K/AKT | Influences cell proliferation, metastasis, drug resistance | Gastric Cancer [18] |

Experimental Evidence: Investigation of the lncRNA EPCART in prostate cancer models revealed its function as a translation-associated lncRNA that operates through modulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 pathway [21]. EPCART reduction resulted in increased PDCD4, an inhibitor of protein translation, accompanied by reduced activation of AKT and inhibition of the mTORC1 pathway. This study exemplifies how cytoplasmic lncRNAs can participate directly in the modulation of translation in cancer cells through this signaling axis.

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway Networks

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway comprises a family of proteins that play critical roles in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis [22]. This pathway can be categorized into canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) signaling, with the canonical pathway being particularly relevant in cancer contexts. The canonical Wnt pathway involves the nuclear translocation of β-catenin and activation of target genes via TCF/LEF transcription factors, primarily controlling cell proliferation [22]. Deregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling leads to various serious diseases, including liver cancer.

In lung cancer models, which share some pathogenic mechanisms with hepatic malignancies, multiple lncRNAs have been identified as regulators of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [23]. For instance, lncRNAs such as CBR3-AS1, CASC15, and MALAT1 function as oncogenes by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, promoting proliferation, migration, invasion, and treatment resistance [23]. These lncRNAs employ diverse mechanisms including miRNA sponging and direct interaction with pathway components.

Table 2: LncRNAs Regulating Wnt/β-catenin Signaling in Lung Cancer Models

| LncRNA | Role | Target miRNA | Regulation of Wnt/β-catenin | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBR3-AS1 | Oncogene | Not available | Activation | Promotes proliferation, migration, invasion of LUAD cells [23] |

| MALAT1 | Oncogene | miR-1297 | Activation | Suppresses apoptosis and cisplatin sensitivity of LUAD cells [23] |

| DANCR | Oncogene | miR-216a | Activation | Promotes proliferation, stemness, invasion of NSCLC cells [23] |

| LINC00514 | Oncogene | Not available | Activation | Promotes proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT of NSCLC cells [23] |

The cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling of β-catenin represents an important feature of Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation that can be influenced by lncRNAs [22]. In the absence of Wnt ligands, a "destruction complex" comprising adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), AXIN, casein kinase 1 (CK1) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 protein (GSK3 protein) captures β-catenin by phosphorylation, activating its degradation. When Wnt signaling is activated, this destruction complex is disrupted, allowing β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation. lncRNAs can intervene at multiple points in this process, offering numerous regulatory opportunities.

MAPK Pathway Networks

The MAPK signaling pathway represents another crucial signaling cascade frequently dysregulated in cancer. While the search results provided limited specific information about lncRNA-MAPK networks in liver cancer, evidence from other cancer types confirms significant crosstalk. In myocardial infarction research, which shares some signaling characteristics with stress responses in cancer cells, the MAPK signaling pathway has been identified as a crucial pathway regulated by lncRNAs [24]. Similarly, in pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network analysis revealed enrichment in positive regulation of MAPK cascade and JNK cascade (a subpathway of MAPK signaling) [25].

Network-based analyses have proven particularly valuable for identifying lncRNAs associated with the MAPK pathway. By constructing lncRNA-mRNA co-expression networks, researchers can identify lncRNAs with similar expression patterns to MAPK pathway genes, suggesting potential functional relationships [24]. This approach has revealed that lncRNAs can regulate crucial pathways in disease states, with the MAPK pathway emerging as a significant target.

Experimental Approaches for Network Analysis

Transcriptomic Profiling and Co-expression Network Construction

The identification of functional lncRNAs and their associated networks typically begins with comprehensive transcriptomic profiling. Both microarray and RNA-sequencing technologies have been successfully employed to characterize lncRNA and mRNA expression patterns in liver cancer and other malignancies [19] [8]. Following data acquisition, co-expression network analysis provides a powerful framework for identifying functionally related genes based on their expression patterns across samples.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) represents a particularly effective approach for constructing lncRNA-mRNA networks [25]. This method clusters highly synergistic changed lncRNAs and mRNAs into modules containing genes with similar expression patterns. The distinct advantage of WGCNA is its ability to identify candidate biomarkers from large gene sets rather than limited differentially expressed genes, providing insights into hub genes responsible for phenotypic traits [25].

A typical WGCNA workflow includes:

- Data preprocessing and normalization of expression matrices

- Network construction and module detection using hierarchical clustering

- Correlation of module eigengenes with clinical traits

- Functional enrichment analysis of module genes

- Construction of lncRNA-mRNA co-expression networks within significant modules

Table 3: Key Analytical Tools for lncRNA-mRNA Network Construction

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Application in Network Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| WGCNA | Weighted co-expression network analysis | Identifies modules of highly correlated genes; correlates modules with clinical traits [25] |

| Pearson's Correlation Coefficient | Measure co-expression relationships | Identifies lncRNA-mRNA pairs with similar expression patterns [19] |

| Functional Enrichment Analysis | Determines biological pathway enrichment | Reveals pathways enriched in co-expressed mRNA partners of lncRNAs [24] |

| STRING database | Protein-protein interaction networks | Identifies interconnected networks among differentially expressed genes [8] |

Functional Validation of Network Components

After identifying candidate lncRNAs through co-expression networks, functional validation becomes essential. Multiple experimental approaches can confirm the biological roles of these molecules:

Cellular Localization Studies: Determining the subcellular localization of lncRNAs provides critical insights into their potential mechanisms. Fractionation experiments followed by qRT-PCR or RNA in situ hybridization can determine whether lncRNAs function in the nucleus or cytoplasm [21]. For example, the lncRNA EPCART was found to be largely located in the cytoplasm and at sites of translation, consistent with its role in modulating translation [21].

Loss-of-Function and Gain-of-Function Experiments: siRNA- or CRISPR-based approaches can effectively knock down or knockout lncRNA expression, while overexpression plasmids can increase their expression [21]. Subsequent phenotypic assays can assess changes in proliferation, migration, invasion, and drug sensitivity. For instance, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma models, siRNA-mediated lncRNA knockdown followed by wound healing and Transwell assays demonstrated functional roles in cell migration and invasion [19].

Mechanistic Studies: Identifying specific molecular interactions is crucial for understanding lncRNA functions. Techniques such as RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP), chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP), and luciferase reporter assays can validate interactions between lncRNAs and their protein or DNA targets [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

A comprehensive toolkit of research reagents is essential for investigating lncRNA-mRNA networks in liver cancer. The following table summarizes key reagents and their applications based on methodologies from the cited literature:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for lncRNA-mRNA Network Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | TRIzol Reagent | Total RNA extraction from tissues and cells | [19] [8] |

| Microarray Platforms | Agilent 4×180K lncRNA Array | Genome-wide lncRNA and mRNA expression profiling | [19] |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | HiScript II Q RT SuperMix | Reverse transcription for qPCR analysis | [19] |

| qPCR Master Mix | 2×SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Quantitative PCR for expression validation | [19] |

| Cell Culture Media | Leibovitz's L-15 medium | In vitro tissue incubation for perturbation studies | [8] |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipofectamine 3000 | Plasmid and siRNA delivery for functional studies | [21] |

| Functional Assay Kits | CCK-8 assay | Cell proliferation assessment | [19] |

| Metabolic Assay Kits | Commercial assay kits for CHO, HDL-C, FFA | Biochemical indicator measurement | [8] |

| RNA In Situ Hybridization | ViewRNA ISH Tissue 2-Plex Assay | Spatial localization of lncRNAs in tissue sections | [21] |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

LncRNA-mRNA Co-expression Network Construction Workflow

LncRNA Regulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling

LncRNA Interaction with Wnt/β-catenin Pathway

The investigation of lncRNA-mRNA networks within core signaling pathways represents a frontier in liver cancer research with significant basic and translational implications. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MAPK, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways each interface with extensive lncRNA regulatory networks that influence pathway activity, downstream effects, and ultimately, tumor behavior. Methodologies for mapping these networks continue to evolve, with co-expression analysis providing a powerful starting point for identifying functional relationships.

As research in this field advances, several challenges and opportunities emerge. The tissue-specific nature of lncRNA expression necessitates liver-focused studies, while the complex ceRNA networks require sophisticated validation approaches. Nevertheless, the potential clinical applications—from novel diagnostic biomarkers to innovative therapeutic targets—provide compelling motivation for continued investigation. The research reagents and methodologies summarized in this review offer a foundation for advancing our understanding of these complex regulatory networks in liver cancer pathogenesis and treatment.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as pivotal regulators of gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), functioning through complex interactions with epigenetic machinery. These RNA molecules, exceeding 200 nucleotides in length and lacking protein-coding capacity, orchestrate chromatin remodeling and gene silencing through multiple mechanistic pathways [26] [11]. The biosynthesis of lncRNAs closely resembles that of protein-coding transcripts, with RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription yielding transcripts that undergo 5'-capping, 3'-polyadenylation, and splicing [26]. Their promoter regions typically display active chromatin marks, including H3K27 acetylation and H3K4 methylation, facilitating transcriptional initiation [26].

In the context of liver cancer, lncRNAs form intricate regulatory networks that contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis through epigenetic modifications. The hepatic epigenome is uniquely responsive to environmental stressors, including viral infections, metabolic dysfunction, and xenobiotic exposure, which can lead to persistent changes in chromatin structure and gene expression relevant to HCC initiation and progression [27] [28]. Understanding these epigenetic regulatory mechanisms provides valuable insights for developing novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for HCC.

Mechanisms of Chromatin Remodeling by lncRNAs

Histone Modification Pathways

LncRNAs interact extensively with histone-modifying complexes, recruiting them to specific genomic loci to alter chromatin architecture and gene accessibility. These interactions facilitate the addition or removal of chemical modifications on histone tails, creating activation or repression markers that determine transcriptional states [26] [28].

The enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), a catalytic component of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), frequently partners with oncogenic lncRNAs in HCC. EZH2 catalyzes the addition of trimethyl groups to histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), a repressive mark that silences tumor suppressor genes [27] [28]. Similarly, lncRNAs interact with histone demethylases such as the KDM family, which remove methyl groups from histones. For instance, KDM1B (lysine-specific histone demethylase 1B), which is upregulated in HCC, demethylates H3K4me1/2, contributing to gene repression and enhanced proliferation [28].

Histone acetylation represents another crucial mechanism regulated by lncRNAs. These molecules recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs) to specific genomic regions, promoting histone deacetylation and subsequent chromatin condensation [27]. HDACs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8 are frequently overexpressed in HCC and associate with poor prognosis, while HDAC6 shows tumor-suppressive characteristics [28]. The dynamic interplay between lncRNAs and histone modifiers establishes precise patterns of gene expression that drive oncogenic processes in hepatocellular carcinoma.

DNA Methylation Dynamics

LncRNAs regulate DNA methylation patterns in HCC through several mechanisms, primarily by directing DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to specific genomic loci. DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of cytosine within cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, catalyzed by DNMT enzymes including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B [26] [29].

Research has demonstrated significant correlations between lncRNA promoter methylation and expression levels in HCC. One comprehensive study identified 93 lncRNA genes with significant negative correlations between promoter methylation and expression levels (Pearson correlation coefficient < -0.3) [26]. Another investigation utilizing TCGA data identified 41 lncRNAs differentially expressed between HCC and normal tissues, with expression levels significantly correlated with methylation patterns [26].

Specific examples include the lncRNA MEG3 (maternally expressed 3), which displays heightened promoter region methylation and reduced expression in HCC. Treatment with demethylating agents or DNMT silencing substantially upregulates MEG3 expression, leading to enhanced apoptosis and impeded proliferation of HCC cells [26]. Similarly, the lncRNA SRHC features a hypermethylated CpG-rich island in its promoter region in HCC cells, with demethylation experiments confirming significant upregulation of SRHC expression following treatment [26].

Beyond promoter methylation, gene body methylation also influences lncRNA transcription. The lncRNA MITA1 (metabolically induced tumor activator 1) is markedly upregulated in HCC cells under serum starvation conditions. This upregulation is associated with increased DNA methylation within a CpG island in the second intron of the MITA1 gene, with DNMT3B identified as the critical methyltransferase responsible for this regulation [26].

Gene Silencing Mechanisms

Direct Transcriptional Repression

LncRNAs facilitate gene silencing through direct recruitment of repressive chromatin-modifying complexes to specific genomic loci. This mechanism enables targeted silencing of tumor suppressor genes and other regulatory genes in HCC. Nuclear lncRNAs can interact with chromatin modifiers such as EZH2, G9a, and HDACs, guiding them to specific gene promoters where they establish repressive chromatin domains [26] [11].

The H3K27me3 mark deposited by EZH2 creates a compact chromatin structure that is inaccessible to transcriptional machinery, effectively silencing gene expression. In HCC, multiple lncRNAs have been identified that recruit EZH2 to tumor suppressor gene promoters, contributing to their epigenetic silencing [28]. This targeted repression represents a fundamental mechanism by which lncRNAs contribute to the acquisition of cancer hallmarks in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Competing Endogenous RNA (ceRNA) Networks

LncRNAs function as molecular sponges for microRNAs (miRNAs) through competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks, thereby modulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. In this regulatory paradigm, lncRNAs contain miRNA response elements (MREs) that compete with mRNAs for binding to specific miRNAs, preventing these miRNAs from interacting with their target mRNAs [13].

In liver fibrosis, a precursor condition to HCC, a comprehensive ceRNA network has been identified comprising differentially expressed lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs. This network includes four lncRNAs, six miRNAs, and 148 mRNAs that form interconnected regulatory axes [13]. For example, the lncRNA H19 acts as a ceRNA for miR-148a-3p, regulating the expression of fibrillin-1 (FBN1) in hepatic stellate cell activation [13]. Similarly, the linc-RoR (long intergenic non-coding RNA-ROR) functions as a molecular sponge for tumor suppressor miR-145 in HCC cells, leading to upregulation of miR-145 downstream targets including p70S6K1, PDK1, and HIF-1α, resulting in accelerated cell proliferation [11].

These ceRNA networks create intricate regulatory circuits that fine-tune gene expression patterns in liver cancer, contributing to disease progression and therapeutic resistance. The dynamic interplay between lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs represents a crucial layer of epigenetic regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Experimental Approaches for Studying lncRNA Epigenetic Mechanisms

Transcriptomic Profiling and Bioinformatics Analysis

Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis provides a powerful approach for identifying epigenetically-regulated lncRNAs and their target networks in HCC. The standard workflow involves RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and sophisticated bioinformatic analysis to identify differentially expressed lncRNAs and construct regulatory networks.

Table 1: Key Experimental Reagents for lncRNA Transcriptomic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | TRIzol reagent | Total RNA isolation from tissues/cells | [8] [7] [13] |

| Library Prep | rRNA depletion, fragmentation, adapter ligation | cDNA library construction for sequencing | [8] [7] |

| Sequencing Platform | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput transcriptome sequencing | [8] [7] |

| Alignment Tool | HISAT2 (v2.2.1) | Mapping reads to reference genome | [8] |

| Assembly Tool | StringTie (v2.2.1) | Transcript assembly from mapped reads | [8] |

| Coding Potential Assessment | CPC2, CNCI, CPAT, Pfam | Distinguishing lncRNAs from coding transcripts | [8] |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2 (v1.40.2) | Identifying significantly differentially expressed RNAs | [8] [7] |

| Functional Enrichment | DAVID, KOBAS | GO and KEGG pathway analysis | [8] [13] |

A critical step in lncRNA identification involves distinguishing them from protein-coding transcripts using multiple complementary tools such as CPC2 (Coding Potential Calculator 2), CNCI (Coding-Non-Coding Index), CPAT (Coding Potential Assessment Tool), and Pfam database searches for conserved protein domains [8]. Only transcripts consistently predicted as non-coding by all four tools should be retained for high-confidence lncRNA sets [8].

Differential expression analysis typically employs statistical methods like DESeq2, which models count data with a negative binomial distribution and applies shrinkage estimation for dispersion and fold change to improve stability and interpretability of results [8] [7]. Significance thresholds commonly used include fold change ≥ 1.5 and P-value < 0.05 [8].

Epigenetic Modification Analyses

Investigating the epigenetic regulation of lncRNAs requires specific methodologies to assess DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin accessibility. These approaches provide mechanistic insights into how lncRNA expression is controlled in HCC.

Table 2: Methodologies for Epigenetic Analysis of lncRNAs

| Methodology | Key Reagents/Resources | Application | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Analysis | Bisulfite conversion, Methylation-specific PCR, Methylation arrays | Promoter and gene body methylation assessment | Methylation levels at CpG islands, correlation with expression |

| Histone Modification Mapping | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), Antibodies against specific marks (H3K27me3, H3K4me3) | Histone modification profiling at lncRNA loci | Enrichment of activating/repressive marks, spatial distribution |

| Chromatin Accessibility Assays | ATAC-seq, DNase I hypersensitivity | Chromatin structure assessment | Accessible chromatin regions, regulatory elements |

| Functional Validation | Decitabine (DNMT inhibitor), HDAC inhibitors, CRISPR/dCas9 systems | Epigenetic modulator manipulation | Causality establishment between specific modifications and expression |

Bisulfite conversion followed by sequencing represents a gold standard for DNA methylation analysis, enabling base-resolution mapping of 5-methylcytosine residues [26]. This approach has been successfully employed to identify hypermethylated CpG islands in the promoter regions of lncRNAs such as MEG3 and SRHC in HCC [26]. For functional validation, demethylating agents like decitabine can be applied to HCC cell lines to demonstrate causal relationships between DNA methylation and lncRNA expression [26].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays utilizing antibodies specific to histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K9ac) allow researchers to map the spatial distribution of these epigenetic marks at lncRNA loci [26] [28]. When combined with sequencing (ChIP-seq), this approach provides genome-wide profiles of histone modifications associated with lncRNA expression changes in HCC.

Extracellular Vesicle Isolation and Analysis

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as valuable sources of disease-associated lncRNAs for biomarker discovery in HCC. These vesicles carry molecular cargo, including lncRNAs, that reflect the pathophysiological state of originating cells [7].

The standard EV isolation protocol involves serial centrifugation steps, size-exclusion chromatography, and ultrafiltration to purify EVs from serum or plasma samples [7]. EV characterization typically includes nanoparticle tracking analysis for size distribution assessment, transmission electron microscopy for morphological examination, and Western blot analysis for marker detection (TSG101, Alix, CD9) with Calnexin as a negative control [7].

RNA extraction from EVs followed by high-throughput transcriptome sequencing enables comprehensive profiling of EV-derived lncRNAs across different stages of liver disease progression [7]. This approach has identified 133 significantly differentially expressed lncRNAs in HCC-derived EVs, with 10 core lncRNAs showing consistent association with HCC progression [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for lncRNA-Epigenetic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for lncRNA-Epigenetic Investigations

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Modulators | Decitabine, 5-azacytidine, HDAC inhibitors (vorinostat), EZH2 inhibitors | Chemical manipulation of epigenetic machinery | Decitabine treatment upregulates MEG3 expression [26] |

| Antibodies for Histone Modifications | Anti-H3K27me3, Anti-H3K4me3, Anti-H3K9ac, Anti-H3K36me2 | Chromatin immunoprecipitation, Western blot | EZH2 deposits H3K27me3 mark [28] |

| DNA Methylation Tools | Bisulfite conversion kits, Methylation-specific PCR primers, Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation kits | DNA methylation mapping | Bisulfite sequencing of MITA1 CpG island [26] |

| RNA Detection & Quantification | RT-qPCR primers/probes, RNA sequencing kits, RNA FISH probes | lncRNA expression assessment | RT-qPCR validation of ceRNA network components [13] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | TGF-β1, serum-free media, hypoxia chamber systems | In vitro disease modeling | TGF-β1-induced JS-1 cells for liver fibrosis modeling [13] |

Concluding Perspectives

The epigenetic regulation of lncRNAs represents a crucial layer of gene expression control in hepatocellular carcinoma. Through mechanisms including histone modification, DNA methylation, and ceRNA network interactions, lncRNAs fine-tune the transcriptional landscape of liver cancer cells, driving oncogenic phenotypes. The experimental methodologies outlined herein provide robust frameworks for investigating these mechanisms, while the identified research reagents offer practical solutions for implementing these approaches. As our understanding of lncRNA epigenetics continues to evolve, these insights promise to inform the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma.

The Impact of Etiological Factors (HBV, HCV, NAFLD) on lncRNA Dysregulation

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as RNA transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides with limited or no protein-coding capacity, have emerged as vital regulators of gene expression, influencing epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional processes [30]. Their expression is frequently dysregulated in cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The major etiological factors for HCC—chronic Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—orchestrate distinct patterns of lncRNA dysregulation, contributing to hepatocarcinogenesis through shared and unique mechanisms [30] [31] [32]. Understanding the interplay between specific liver diseases and lncRNA networks is crucial for unraveling the molecular pathogenesis of HCC and identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. This review synthesizes current knowledge on how HBV, HCV, and NAFLD reshape the lncRNA landscape within the context of liver cancer research.

HBV-Induced lncRNA Dysregulation

Chronic Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major global risk factor for HCC, with approximately 292 million people living with the chronic form of the disease [30] [4]. The viral protein HBx is a key driver of lncRNA dysregulation, which in turn facilitates viral persistence and promotes malignant transformation.

Table 1: Key lncRNAs Dysregulated in HBV-Related HCC and Their Mechanisms of Action

| LncRNA | Dysregulation | Mechanism of Action | Role in HBV-related HCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | Upregulated | Stimulates HBx to activate STAT3; sequesters miR-372; represses p18 transcription [30]. | Stabilizes cccDNA; promotes HBV replication; cell proliferation [30]. |

| HEIH | Upregulated | EZH2-mediated epigenetic silencing of p15, p16, p21, and p57 [30]. | Promotes cell proliferation [30]. |

| DLEU2 | Upregulated | Relieves EZH2 suppression of cccDNA [30]. | Promotes viral replication [30]. |

| HOTAIR | Upregulated | Functions as a scaffold for ubiquitination complexes; recruits transcription factor Sp1 to the HBV promoter [30]. | Promotes viral replication and pluripotency of hepatocytes [30]. |

| PCNAP1 | Upregulated | Sequesters miR-154 and miR-340-5p, preventing inhibition of PCNA and ATF7, respectively [30]. | Promotes HBV replication, cccDNA accumulation, and cell proliferation [30]. |

| MALAT1 | Upregulated | Recruits Sp1 to the promoter of the LTBP3 gene [30]. | Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) [30]. |

| DREH/hDREH | Downregulated | Binds to and alters the structure of vimentin to inhibit metastasis [30]. | Downregulation increases cell proliferation and EMT [30]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic pathways through which HBx-mediated lncRNA dysregulation promotes HBV replication and HCC pathogenesis.

NAFLD and lncRNA Dysregulation in Hepatocarcinogenesis

NAFLD, affecting about 25% of adults globally, encompasses a spectrum from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and HCC [32]. The metabolic dysfunction inherent to NAFLD drives lncRNA dysregulation, which interacts with and can exacerbate the pathways of virus-induced HCC.

A primary mechanism involves immune and inflammatory signaling. The NAFLD microenvironment, characterized by lipotoxicity and elevated free fatty acids (FFAs), promotes activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways, particularly TLR4/MyD88 [32]. This signaling leads to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and profibrogenic factors (e.g., TGF-β), activating hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and driving fibrosis [32]. This inflammatory milieu can also inhibit HBV replication by inducing antiviral cytokines like IFN-β, yet it simultaneously creates a protumorigenic environment that accelerates the progression to HCC in co-existing conditions [32].

Comparative Analysis of Etiological Factors

While all three etiologies converge on HCC, they engage distinct and overlapping lncRNA networks. HBV strongly dysregulates lncRNAs via the HBx protein, directly manipulating host machinery for viral replication and incidentally promoting oncogenesis [30]. NAFLD-driven dysregulation is tightly linked to metabolic stress and lipotoxicity, activating innate immune and pro-fibrotic pathways [32]. Although specific lncRNAs for HCV were less featured in the provided search results, it is understood that HCV infection also induces a specific profile of lncRNA dysregulation. Research indicates that the lncRNA networks perturbed in non-viral NAFLD-driven HCC can exhibit significant differences from those in virus-induced HCC [30] [33].

Table 2: LncRNAs as Prognostic Biomarkers in HCC: A Meta-Analysis Summary

| Prognostic Measure | Number of Studies/LncRNAs | Pooled Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% Confidence Interval | Significance (p-value) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival (OS) | 19 lncRNAs (low expr.) & 30 lncRNAs (high expr.) | 1.25 | 1.03 - 1.52 | p = 0.03 | High lncRNA expression predicts poorer overall survival [31]. |

| Recurrence-Free Survival (RFS) | 15 lncRNAs | 1.66 | 1.26 - 2.17 | p < 0.01 | High lncRNA expression predicts significantly worse recurrence-free survival [31]. |

| Disease-Free Survival (DFS) | 6 lncRNAs | 1.04 | 0.52 - 2.07 | p = 0.91 | Association not statistically significant [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for lncRNA Research

Identifying Clinically-Relevant lncRNA-mRNA Networks

This protocol outlines a bioinformatics-driven approach to identify lncRNAs with prognostic value and their co-regulated mRNA networks in HCC [33].

- Sample Collection and Profiling: Obtain paired HCC tumor and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues from a patient cohort. Extract total RNA and perform genome-wide expression profiling using microarrays or RNA-Seq for both lncRNAs and mRNAs.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify differentially expressed (DE) lncRNAs and mRNAs using a threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05 and absolute fold change > 2.0) with tools like DESeq2 or the limma R package [34] [33].

- Co-expression Network Construction: Perform Pearson correlation analysis between DE lncRNAs and DE mRNAs. Construct co-expression networks using a high stringency threshold (e.g., |Pearson R| ≥ 0.90) and visualize them with Cytoscape software [33].

- Clinical Association and Pathway Analysis: Integrate patient clinicopathological data (e.g., tumor grade, capsule formation, survival). Statistically associate lncRNA expression levels with clinical phenotypes. Perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., GO, KEGG using databases like ConsensusPathDB) on mRNAs within clinically significant co-expression networks to infer biological functions [33].

The workflow for this integrative analysis is summarized below.

Validating miRNA Sponging (ceRNA) Mechanisms

A common functional mechanism for lncRNAs is acting as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) or "sponge" for microRNAs (miRNAs). The following steps outline a standard validation protocol [34] [35].

- Prediction of miRNA Binding Sites: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., miRanda, TargetScan) to predict potential binding sites for miRNAs within the lncRNA sequence of interest.

- Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay:

- Vector Construction: Clone the wild-type lncRNA sequence or a fragment containing the predicted miRNA binding site into a reporter plasmid downstream of a luciferase gene. Generate a mutant plasmid with seed sequence mutations.

- Co-transfection: Co-transfect the reporter plasmid along with a synthetic mimic of the target miRNA (or a negative control miRNA) into a relevant HCC cell line (e.g., Huh7, PLC/PRF/5).

- Measurement: After 24-48 hours, measure firefly and renilla luciferase activities. A significant reduction in luciferase activity for the wild-type vector, but not the mutant, upon miRNA mimic co-transfection confirms direct interaction.

- Functional Rescue: Transfert cells with the lncRNA and its targeting miRNA mimic simultaneously. Assess downstream gene expression (e.g., by qPCR) or phenotypic changes (e.g., proliferation, invasion) to confirm the functional consequence of the ceRNA interaction.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for lncRNA Research in Liver Cancer

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Huh7, SMMC7721, PLC/PRF/5, Bel7404, L02 (normal hepatocyte) | In vitro modeling of HCC biology, viral infection, and functional validation of lncRNAs [34]. | Maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS [34]. |

| Molecular Biology | miRNA Mimics and Inhibitors | Functionally gain or loss of miRNA activity to validate ceRNA mechanisms [34]. | Synthetically designed RNA molecules. |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System | Quantifying transcriptional activity and validating direct miRNA-lncRNA interactions [35]. | A standard for confirming binding. | |

| Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Gold standard for validating expression levels of lncRNAs, mRNAs, and miRNAs. | Uses GAPDH or β-actin as reference genes [31]. | |

| Bioinformatics | GEO Datasets (NCBI) | Public repository for transcriptomic data (mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA) for integrative analysis [34]. | Source for primary data. |

| Cytoscape Software | Visualization and analysis of complex molecular interaction networks [34] [33]. | Essential for network biology. | |

| STRING Database, KEGG, GO | Protein-protein interaction and functional pathway enrichment analysis [34]. | For functional annotation. |

The dysregulation of lncRNAs is a central mechanism through which diverse etiological factors like HBV, HCV, and NAFLD drive hepatocarcinogenesis. Each etiology imposes a distinct selective pressure, leading to unique lncRNA signatures that modulate viral replication, metabolic pathways, immune responses, and core cancer hallmarks such as proliferation, EMT, and metastasis. The integration of advanced transcriptomic profiling with clinical data is uncovering complex, clinically-relevant lncRNA-mRNA networks, positioning lncRNAs as promising prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Future research, leveraging single-cell technologies and sophisticated in vivo models, will be crucial to dissect the precise functional hierarchies of these networks and translate these findings into novel therapeutic strategies for HCC.

Analytical Approaches and Network Construction Strategies

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as RNA transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides in length that lack functional open reading frames [36]. These molecules represent a vast and rapidly growing component of the transcriptome, with over 60,000 lncRNAs currently identified in humans [11]. Unlike mRNA, lncRNAs exhibit remarkable tissue specificity, making them particularly valuable as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in diseases with defined tissue pathology, such as liver cancer [36].

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), lncRNAs function as crucial epigenetic modifiers that regulate gene expression through diverse mechanisms, including chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, and post-transcriptional processing [37] [11]. They can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors, influencing key cancer pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT, and cell cycle regulation [11]. For instance, lncRNA H19 stimulates the CDC42/PAK1 axis to increase HCC cell proliferation, while lncRNA-p21 forms a positive feedback loop with HIF-1α to drive tumor growth [11]. The discovery and characterization of these molecules rely heavily on advanced transcriptomic profiling technologies, primarily RNA sequencing and microarray platforms.

Transcriptomic Profiling Technologies: Principles and Methodologies

RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) for lncRNA Discovery

RNA-Seq represents a powerful, high-resolution approach for transcriptome-wide lncRNA discovery. This technology involves several critical steps that collectively enable comprehensive lncRNA characterization.

Table 1: Key Steps in RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

| Step | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | Isolation of total RNA using reagents such as TRIzol | RNA integrity number (RIN) >8.0 ensures high-quality input material [38] [8] |

| Library Preparation | rRNA depletion, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation | rRNA reduction crucial for lncRNA enrichment; TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit commonly used [38] |

| Sequencing | High-throughput sequencing on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq | 150bp paired-end reads recommended; 45-60 million reads per sample typical [38] [8] |

| Quality Control | Assessment of raw read quality using Fastp, FastQC | Q30 scores >90% indicate high base call accuracy; filter low-quality bases [39] [8] |

Following sequencing, a specialized bioinformatics pipeline is required to identify and characterize lncRNAs. This process begins with read alignment to a reference genome using tools such as HISAT2, followed by transcript assembly with StringTie [39] [8]. The critical differentiation between mRNA and lncRNA involves a multi-step filtering approach:

- Structural Filtering: Retain transcripts with class codes "i", "x", "u", "o", or "e" indicating novel intergenic, antisense, or intronic transcripts [8]

- Length Threshold: Exclude transcripts shorter than 200 nucleotides [39]

- Coding Potential Assessment: Apply multiple computational tools including CPC2, CNCI, CPAT, and Pfam to reliably distinguish non-coding from protein-coding transcripts [39] [8]