Dysregulated Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetic Patients with Hyperuricemia: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Implications

This article synthesizes current research on the distinct lipidomic profiles in diabetic patients with concurrent hyperuricemia, a high-risk clinical phenotype.

Dysregulated Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetic Patients with Hyperuricemia: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the distinct lipidomic profiles in diabetic patients with concurrent hyperuricemia, a high-risk clinical phenotype. We explore the foundational pathophysiological links between uric acid and lipid metabolism, detailing specific alterations in glycerophospholipids, glycerolipids, and sphingolipids identified via advanced mass spectrometry. The content covers methodological approaches for lipidomic analysis, tackles challenges in data interpretation and confounding factors, and validates the clinical significance of lipid signatures against diabetic complications like nephropathy and retinopathy. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights the potential of lipid species as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, offering a roadmap for future mechanistic and translational investigations.

Unraveling the Pathophysiological Link Between Uric Acid and Lipid Metabolism in Diabetes

The co-occurrence of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represents a significant clinical synergy that amplifies renal, cardiovascular, and metabolic risks. This comprehensive review examines the epidemiological burden, underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, and advanced methodological approaches for investigating this metabolic interplay. We synthesize evidence from recent clinical studies and experimental models, highlighting the uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR) as a promising composite biomarker for risk stratification. The integration of lipidomic and metabolomic profiling provides novel insights into the shared pathways driving disease progression, offering new avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions and personalized medicine approaches in diabetic patients with concurrent metabolic abnormalities.

Diabetes mellitus represents a global health challenge, with projections estimating that 783 million people will be affected by 2045 [1]. Beyond its classic glycemic manifestations, T2DM frequently presents with a cluster of metabolic comorbidities, notably dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia, which collectively contribute to a heightened risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and microvascular complications [2]. The epidemiological synergy between these conditions reflects shared pathophysiological mechanisms including insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction [2].

Recent evidence suggests that the co-occurrence of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia may represent a more advanced stage of metabolic dysregulation, warranting earlier and more aggressive intervention strategies [2]. This review synthesizes current understanding of this clinical synergy within the context of a broader thesis on lipidomic profiles in diabetic patients with high uric acid, providing researchers and drug development professionals with methodological frameworks and analytical approaches for investigating this complex metabolic interplay.

Epidemiological Burden and Clinical Significance

Prevalence and Population Impact

The co-occurrence of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in diabetic populations presents a substantial clinical burden. A recent retrospective observational study involving 304 patients with uncontrolled T2DM reported a striking prevalence of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia co-occurrence of 81.6% [2] [3]. This high prevalence underscores the clinical significance of this metabolic synergy in advanced diabetes.

Table 1: Prevalence of Dyslipidemia and Hyperuricemia Co-occurrence in Diabetic Populations

| Population Characteristics | Sample Size | Prevalence of Co-occurrence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled T2DM (HbA1c ≥7%) | 304 | 81.6% | [2] |

| Hypertensive diabetic patients | 274 | Significant association (P=0.01) | [4] |

| Non-obese T2DM with MAFLD | 506 | Gradually increased with UHR | [5] |

Hyperuricemia itself demonstrates varying global prevalence, with rates of 21% in the U.S., 11.4% in Korea, and 17.7% in China as of 2017 [6]. The prevalence is notably higher in developed countries and urban environments, with geographical variations showing highest rates in southern China (9.1%) compared to northern China (3.2%) [6].

Quantitative Risk Associations

Multiple studies have quantified the risk relationships between uric acid metrics and diabetic complications:

Table 2: Risk Associations Between Uric Acid Metrics and Diabetic Complications

| Uric Acid Metric | Population | Outcome Measure | Effect Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHR | 2,731 participants | AAC scores | β: 0.53 (0.31, 0.75) per log2-UHR | [7] |

| UHR | 17,227 participants | Diabetic nephropathy | OR: 1.19 (1.17-1.22) | [1] |

| UHR | 285 T2DM patients | Depression (SDS scores) | β: 1.55 (0.57-2.53) | [8] |

| UHR | 285 T2DM patients | Anxiety (SAS scores) | β: 0.72 (0.35-1.09) | [8] |

The uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR) has emerged as a particularly valuable biomarker, integrating both pro-oxidant (uric acid) and antioxidant (HDL-C) pathways [7] [1] [8]. Studies have identified specific UHR thresholds for clinical risk stratification, with values above 5.02 and 4.00 associated with significantly exacerbated depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively, in T2DM patients [8].

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Shared Metabolic Pathways

The interrelationship between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in diabetes is underpinned by several interconnected pathophysiological mechanisms. Both conditions share overlapping pathways including insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction [2]. Uric acid possesses dualistic biological roles—acting as an antioxidant at physiological levels but transforming into a pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory molecule at elevated concentrations [6].

The role of triglycerides as a mediator in the hyperuricemia-diabetes link has been demonstrated in hypertensive populations, where hyperuricemia was positively associated with elevated triglyceride levels (coefficient = 0.67, P=0.01), which in turn significantly increased DM risk (coefficient = 1.29, P < 0.001) [4]. Although the direct effect of hyperuricemia on DM was not statistically significant (coefficient = -0.61, P=0.10), the indirect effect mediated by triglycerides was substantial (coefficient = 0.87, P=0.04) [4].

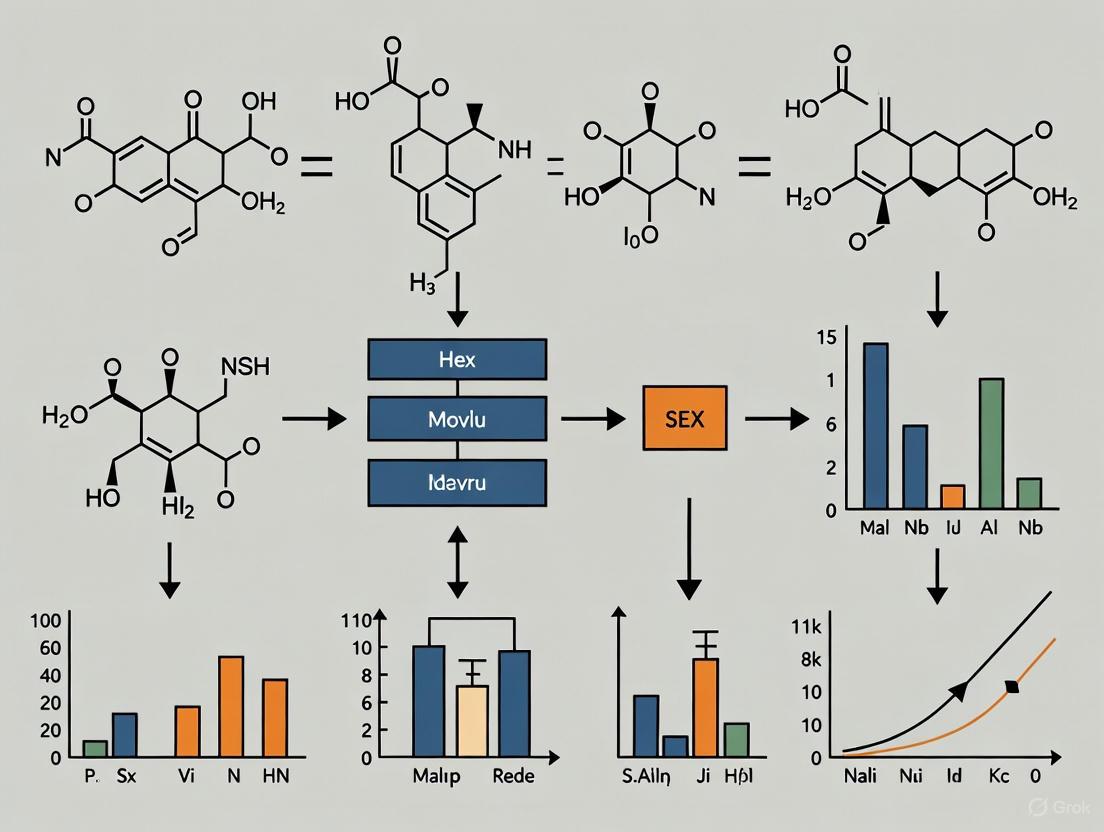

Diagram: Pathophysiological Interplay Between Hyperuricemia and Dyslipidemia in Diabetes. This pathway illustrates the key mechanistic links between hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia, highlighting their synergistic effects on diabetic complications.

Renal and Hepatic Implications

The coexistence of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia amplifies renal injury through multiple pathways. Experimental models demonstrate that hyperuricemia is closely related to decreased antioxidant capacity, increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and transforming growth factor-β expressions, and altered epithelial integrity of the gut microbiota in diabetic animals [9]. These changes collectively promote glomerular mesangial cells and matrix proliferation, protein casts, and urate deposition [9].

In hepatic manifestations, UHR has shown significant predictive value for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) in non-obese T2DM patients [5]. The relationship follows a dose-response pattern, with MAFLD prevalence gradually increasing across UHR tertiles, highlighting the clinical utility of this ratio for identifying hepatic complications in apparently lower-risk, non-obese diabetic populations.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Models

Animal Model Development

The establishment of a novel diabetic model of hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia in male Golden Syrian hamsters provides a valuable platform for investigating this metabolic synergy [9]. The experimental protocol involves specific reagents and induction methods:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Models

| Reagent/Model | Function/Purpose | Experimental Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Oxonate (PO) | Uricase inhibitor | Induces hyperuricemia (350 mg/kg intragastric) | [9] |

| High-Fat/Cholesterol Diet (HFCD) | Induces dyslipidemia | 15% fat, 0.5% cholesterol diet | [9] |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | β-cell cytotoxin | Induces diabetes (30 mg/kg i.p. for 3 days) | [9] |

| Adenine | Uric acid precursor | Potentiates hyperuricemia (150 mg/kg) | [9] |

The combination of PO treatment and HFCD successfully established a hamster model with both hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia, characterized by serum uric acid levels of 499.5 ± 61.96 μmol/L, glucose of 16.88 ± 2.81 mmol/L, triglyceride of 119.88 ± 27.14 mmol/L, and total cholesterol of 72.92 ± 16.62 mmol/L [9]. This model faithfully replicates the clinical phenotype observed in diabetic patients with combined metabolic disturbances.

Analytical and Omics Technologies

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomic and lipidomic profiling has emerged as a powerful approach for stratifying stages of diabetic complications and understanding the metabolic underpinnings of the dyslipidemia-hyperuricemia synergy [10]. The methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE)/methanol extraction method demonstrates superior performance for simultaneous extraction of polar and nonpolar metabolites, with the lowest coefficient of variation compared to ethanol and chloroform systems [10].

Diagram: Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomic/Lipidomic Workflow. This experimental workflow outlines the integrated approach for comprehensive metabolic profiling in diabetic dyslipidemia-hyperuricemia research.

Machine learning algorithms applied to metabolomic datasets have shown promise in identifying pattern recognition and improving prediction of disease progression. These computational approaches can detect subtle patterns in complex datasets that might not be apparent through conventional statistical methods [10].

Risk Stratification and Clinical Assessment Tools

Composite Risk Scores

The Renal-Metabolic Risk Score (RMRS) represents a novel approach for identifying patients with uncontrolled T2DM at risk for combined hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia [2]. This optimized score integrates renal and lipid parameters, calculated from standardized values of urea, TG/HDL ratio, and eGFR, with variable weights derived from logistic regression coefficients and normalized to a 0-100 scale [2].

The RMRS demonstrated good discriminative performance with an AUC of 0.78 in ROC analysis, effectively stratifying patients into risk quartiles with a monotonic gradient in co-occurrence prevalence from 64.5% in Q1 to 96.1% in Q4 [2]. The utilization of inexpensive, routine laboratory parameters makes this score particularly valuable for resource-limited settings to support early risk stratification, dietary counseling, and timely referral [2].

UHR as a Composite Biomarker

The uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR) has demonstrated versatile clinical utility across multiple diabetic complications:

Table 4: Clinical Utility of UHR Across Diabetic Complications

| Complication | Study Population | UHR Threshold | Clinical Utility | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal Aortic Calcification | 2,731 participants | Continuous association | Diabetes mediated 7.5-14% of association | [7] |

| Diabetic Nephropathy | 17,227 participants | >5.44 | 44% increased risk per unit UHR | [1] |

| Depression/Anxiety | 285 T2DM patients | 5.02/4.00 | Threshold effect for symptoms | [8] |

| MAFLD | 506 non-obese T2DM | Tertiles | Gradual risk increase across tertiles | [5] |

The UHR reflects the balance between pro-oxidant (uric acid) and antioxidant (HDL-C) pathways, capturing multiple dimensions of metabolic dysfunction in a single metric [7] [1] [8]. Its calculation is straightforward: UHR = UA (mg/dL)/HDL (mg/dL), making it easily implementable in clinical and research settings [7].

The epidemiological synergy between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in diabetes represents a significant clinical challenge with implications for renal, cardiovascular, hepatic, and mental health outcomes. The high prevalence of this co-occurrence, particularly in uncontrolled T2DM, underscores the need for integrated assessment and management strategies.

Future research directions should focus on validating composite biomarkers like UHR in diverse populations and exploring the gut-kidney axis in hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia progression. The application of multi-omics technologies, including mass spectrometry-based lipidomics and metabolomics, provides unprecedented opportunities to unravel the complex metabolic networks underlying this synergy. Furthermore, the development of targeted interventions addressing both conditions simultaneously may yield superior outcomes compared to single-target approaches.

For drug development professionals, these findings highlight potential therapeutic targets within the shared pathological pathways, including xanthine oxidase inhibition combined with lipid-modifying agents, and novel compounds addressing the inflammatory cascade common to both conditions. The integration of advanced risk stratification tools like RMRS and UHR into clinical trial design may enhance patient selection and enable personalized treatment approaches for this metabolically complex population.

Hyperuricemia is increasingly recognized as a significant contributor to metabolic dysregulation, particularly in the context of diabetes. This technical review synthesizes current mechanistic insights into how elevated uric acid disrupts lipid handling in hepatic and adipose tissues. We examine the molecular pathways through which uric acid induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, activates inflammatory cascades, and alters lipidomic profiles, with particular emphasis on its role in diabetic dyslipidemia. The analysis incorporates lipidomics data revealing specific alterations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways in hyperuricemic conditions. Furthermore, we evaluate experimental models and pharmacological interventions that demonstrate reversal of uric acid-induced lipid metabolic disturbances, providing a foundation for targeted therapeutic strategies in diabetic populations with comorbid hyperuricemia.

Uric acid, the final enzymatic product of purine metabolism, has evolved from being solely considered in the context of gout to a recognized mediator of metabolic dysfunction [6]. In diabetic patients, hyperuricemia presents a particularly complex clinical challenge, with epidemiological studies indicating a 17% increase in diabetes risk for every 1 mg/dL rise in serum uric acid [11]. The global prevalence of hyperuricemia has reached alarming levels, with reports indicating rates of 17.7% in mainland China and approximately 20% in the United States [12] [6]. Within diabetic populations, this comorbidity signifies a more severe metabolic disturbance characterized by exacerbated dyslipidemia and accelerated end-organ damage [11] [13].

The physiological paradox of uric acid – acting as both an antioxidant and pro-oxidant molecule depending on concentration and cellular context – complicates its mechanistic role in metabolic pathways [6]. At physiological levels, uric acid functions as a powerful antioxidant, neutralizing free radicals and reactive oxygen species. However, when elevated, it transforms into a pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory molecule that exacerbates oxidative stress and promotes metabolic dysfunction [6]. This dual nature is particularly relevant in the diabetic milieu, where underlying oxidative stress and inflammation already create a vulnerable metabolic environment.

This review examines the specific mechanistic pathways through which elevated uric acid disrupts lipid homeostasis in hepatic and adipose tissues, with particular focus on insights gained from lipidomic profiling in diabetic models. We synthesize evidence from molecular studies, animal models, and human lipidomic analyses to provide a comprehensive picture of uric acid's role in diabetic dyslipidemia, highlighting novel therapeutic targets and research directions.

Molecular Mechanisms of Uric Acid-Induced Hepatic Lipid Dysregulation

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and SREBP-1c Activation

Uric acid promotes hepatic lipogenesis through induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and subsequent activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) pathway [14]. Mechanistic studies demonstrate that uric acid treatment in hepatocytes significantly upregulates GRP78/94 expression, promotes XBP-1 splicing, and enhances phosphorylation of PERK and eIF-2α, hallmark indicators of ER stress activation [14]. This ER stress response activates SREBP-1c, leading to transcriptional upregulation of key lipogenic enzymes including acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1), fatty acid synthase (FAS), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) [14]. The critical role of this pathway is confirmed by intervention studies showing that the ER stress blocker tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) and the SREBP-1c inhibitor metformin effectively prevent uric acid-induced hepatic fat accumulation [14].

Table 1: Key Lipogenic Enzymes Upregulated by Uric Acid Via SREBP-1c Activation

| Enzyme | Function in Lipogenesis | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) | Catalyzes conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, the rate-limiting step in fatty acid synthesis | Upregulated in uric acid-treated HepG2 cells and primary hepatocytes [14] |

| Fatty acid synthase (FAS) | Multi-enzyme complex that synthesizes palmitate from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA | Significantly increased expression following uric acid exposure [14] |

| Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) | Introduces double bonds in fatty acids, regulating membrane fluidity and lipid storage | Enhanced expression contributes to triglyceride accumulation [14] |

miRNA Dysregulation and FGF21 Signaling Impairment

A separate mechanism involves uric acid-mediated dysregulation of microRNA expression, particularly miR-149-5p, which directly targets fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) [15]. Hepatic miRNA microarray analysis revealed that miR-149-5p is significantly upregulated in livers of high-fat diet-fed mice, while allopurinol-mediated uric acid reduction normalizes its expression [15]. Functional studies demonstrate that miR-149-5p overexpression exacerbates uric acid-induced triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes, while miR-149-5p inhibition ameliorates lipid accumulation [15]. Luciferase reporter assays confirmed FGF21 as a direct target gene of miR-149-5p, establishing the miR-149-5p/FGF21 axis as a key regulatory mechanism in uric acid-induced hepatic steatosis [15].

Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Pathways

Uric acid induces a cascade of oxidative stress events beginning with NADPH oxidase activation, which precedes ER stress and subsequently induces mitochondrial ROS production [14]. This pro-oxidant environment promotes hepatic lipid accumulation through multiple mechanisms, including direct oxidation of lipids, activation of stress-sensitive signaling pathways, and induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In gouty models, hepatic injury is characterized by impaired mitochondrial function evidenced by decreased tetra 18:2 cardiolipin and reduced 4-hydroxyalkenal bioavailability [16]. These metabolic disturbances create a permissive environment for ectopic fat accumulation in hepatocytes and are ameliorated by urate-lowering therapy [16].

Figure 1: Hepatic Lipid Accumulation Pathways. Elevated uric acid triggers multiple mechanisms including oxidative stress, ER stress, and miRNA dysregulation that converge to promote hepatic triglyceride accumulation.

Adipose Tissue as an Active Site of Uric Acid Production and Lipid Dysregulation

Adipose Tissue Xanthine Oxidoreductase Activity

Contrary to traditional understanding that uric acid is primarily produced in the liver, emerging evidence demonstrates that adipose tissue expresses abundant xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) activity and actively secretes uric acid [17]. This discovery positions adipose tissue as a significant contributor to systemic uric acid homeostasis, particularly in obese states. Studies comparing XOR activity across tissues reveal adipose tissue as one of the major organs with substantial XOR expression and activity [17]. Critically, adipose tissues from obese mice demonstrate higher XOR activities than those from control mice, suggesting enhanced uric acid production capacity in expanded adipose mass [17].

Table 2: Evidence for Adipose Tissue as a Site of Uric Acid Production

| Experimental Model | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| 3T3-L1 adipocytes | Mature adipocytes produce and secrete uric acid into culture medium | Secretion inhibited by febuxostat in dose-dependent manner or XOR gene knockdown [17] |

| Mouse primary adipocytes | Differentiation increases uric acid production capacity | Confirms adipocytes as source of uric acid, not just stromal vascular fraction [17] |

| Ob/ob mice | Adipose tissue XOR activity elevated in genetic obesity model | Obesity enhances enzymatic capacity for uric acid production [17] |

| Surgical ischemia | Increases local uric acid production in adipose tissue | Hypoxia may drive uric acid production in expanded adipose tissue [17] |

Hypoxia-Induced Uric Acid Production

Adipose tissue expansion in obesity creates relative hypoxia that further stimulates uric acid production. Experimental studies demonstrate that uric acid secretion from 3T3-L1 adipocytes increases significantly under hypoxic conditions [17]. This hypoxia-induced uric acid production establishes a vicious cycle in expanded adipose tissue, where inadequate oxygenation drives uric acid production, which in turn promotes local inflammation and insulin resistance. Surgical induction of ischemia in adipose tissue experimentally confirms this relationship, resulting in increased local uric acid production and secretion via XOR, with subsequent elevation in circulating uric acid levels [17].

Alterations in Adipokine Profile

Uric acid disruption of adipose tissue function extends to altered adipokine secretion, characterized by elevated leptin, resistin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and decreased adiponectin levels [18]. This dysregulated adipokine profile promotes systemic insulin resistance and creates a pro-inflammatory environment that further exacerbates lipid metabolic disturbances. The altered adipokine secretion may represent a mechanism through which adipose tissue communicates uric acid-mediated metabolic stress to other tissues, including liver and muscle, potentially explaining the multi-organ insulin resistance observed in hyperuricemic states.

Lipidomic Profiles in Hyperuricemia and Diabetic Comorbidity

Distinct Lipidomic Signatures in Hyperuricemia

Advanced lipidomic technologies have revealed specific alterations in lipid species associated with hyperuricemia, particularly in the context of diabetes. A comprehensive lipidomic analysis of 2247 community-based Chinese individuals identified 123 lipids significantly associated with uric acid levels, predominantly glycerolipids (GLs) and glycerophospholipids (GPs) [12]. Specific lipid signatures positively associated with hyperuricemia risk include diacylglycerols [DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5), DAG (18:1/22:6)], phosphatidylcholine [PC (16:0/20:5)], and triacylglycerol [TAG (53:0)], while lysophosphatidylcholine [LPC (20:2)] was inversely associated with hyperuricemia risk [12].

In patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia, untargeted lipidomic analysis identifies 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites compared to healthy controls, with 13 triglycerides, 10 phosphatidylethanolamines, and 7 phosphatidylcholines significantly upregulated, and one phosphatidylinositol downregulated [11]. Pathway analysis reveals these differential lipids are predominantly enriched in glycerophospholipid metabolism and glycerolipid metabolism pathways, highlighting these as central metabolic disturbances in the diabetic-hyperuricemic state [11].

Mediation by Adipokines and Dietary Influences

The relationship between specific lipid species and uric acid appears partially mediated by adipokines, with retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) accounting for 5-14% of the mediation effect in statistical models [12]. RBP4, an adipokine linked with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, may serve as a mechanistic bridge between uric acid elevation and specific lipid alterations. Furthermore, dietary factors significantly influence both uric acid levels and associated lipid patterns, with increased aquatic product intake correlating with elevated hyperuricemia risk and HUA-associated lipids, while high dairy consumption correlates with lower levels of HUA-associated lipids [12].

Table 3: Lipid Classes Altered in Hyperuricemia with Diabetes

| Lipid Class | Specific Examples | Direction of Change | Proposed Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG (16:0/18:1/18:2), TG (53:0) | Upregulated [12] [11] | Hepatic and adipose lipid storage; energy homeostasis |

| Diacylglycerols (DAGs) | DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5), DAG (18:1/22:6) | Upregulated [12] | Signaling molecules; insulin resistance |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC (16:0/20:5), PC (36:1) | Upregulated [12] [11] | Membrane integrity; lipoprotein metabolism |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE (18:0/20:4) | Upregulated [11] | Mitochondrial function; membrane fusion |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) | LPC (20:2) | Downregulated [12] | Anti-inflammatory properties; insulin sensitivity |

Figure 2: Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetic Hyperuricemia. Lipidomics reveals specific lipid class alterations enriched in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways in diabetic hyperuricemia.

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

In Vivo Models of Hyperuricemia and Gout

Animal models have been instrumental in elucidating the mechanistic links between uric acid and lipid metabolic disturbances. The gouty model induced by monosodium urate (MSU) crystals combined with high-fat diet recapitulates key features of human disease, including hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation [16]. In this model, lipidomic analysis of hepatic tissue reveals ectopic fat accumulation, altered fatty acyls composition in TAG pools, impaired mitochondrial function (decreased tetra 18:2 cardiolipin), and reduced 4-hydroxyalkenal bioavailability [16]. Pharmacological interventions with colchicine or febuxostat in these models not only ameliorate gouty symptoms but also correct abnormal hepatic lipid metabolism patterns, supporting a direct role for uric acid and inflammation in driving lipid disturbances [16].

Cell Culture Systems

Primary hepatocytes and hepatocyte cell lines (e.g., HepG2, AML-12) have been extensively used to study the direct effects of uric acid on hepatic lipid metabolism [15] [17] [14]. These systems allow for controlled investigation of specific pathways without the confounding factors present in vivo. Established protocols typically involve treating hepatocytes with 250-750 μmol/L uric acid for 48 hours to induce lipid accumulation, which can be quantified via Oil Red O staining or triglyceride measurement assays [15]. Similarly, 3T3-L1 adipocytes and primary mature adipocytes demonstrate uric acid production capability and respond to uric acid exposure with altered lipid metabolism and adipokine secretion [17].

Lipidomic Methodologies

Comprehensive lipid profiling employs multi-dimensional mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics (MDMS-SL) and UHPLC-MS/MS-based platforms to quantify hundreds of lipid species across multiple classes [11] [16]. These techniques enable identification of specific lipid alterations associated with hyperuricemia, providing insights into disturbed metabolic pathways. Sample preparation typically involves lipid extraction using methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) protocols, followed by chromatographic separation and mass spectrometry analysis [12] [11]. Sophisticated data analysis approaches, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), help identify lipid patterns distinguishing hyperuricemic from normouricemic states [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Models for Studying Uric Acid-Lipid Metabolism Interactions

| Reagent/Model | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HepG2, AML-12 hepatocytes; 3T3-L1 adipocytes | In vitro mechanistic studies | Uric acid induces ER stress, SREBP-1c activation, and lipogenic gene expression [15] [14] |

| Animal Models | ob/ob mice; MSU crystal + HFD model; Febuxostat-treated controls | In vivo pathophysiology and therapeutic studies | Adipose tissue XOR activity increased in obesity; Urate-lowering therapies improve lipid metabolism [17] [16] |

| Inhibitors | Allopurinol, Febuxostat (XOR inhibitors); TUDCA (ER stress blocker) | Pathway inhibition studies | XOR inhibition reduces uric acid production and hepatic steatosis; ER stress blockade prevents SREBP-1c activation [15] [14] |

| Molecular Tools | miR-149-5p mimic/inhibitor; FGF21 overexpression plasmids | Gain/loss-of-function studies | miR-149-5p targets FGF21 to regulate lipid accumulation; FGF21 overexpression prevents uric acid-induced steatosis [15] |

| Analytical Platforms | UHPLC-MS/MS; Shotgun lipidomics | Comprehensive lipid profiling | Identification of specific lipid species and pathways disrupted in hyperuricemia [12] [11] [16] |

| NOT Receptor Modulator 1 | NOT Receptor Modulator 1, MF:C22H19ClN2O, MW:362.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Potassium Channel Activator 1 | Potassium Channel Activator 1, CAS:908608-06-0, MF:C₁₉H₂₃N₃O₃, MW:341.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The mechanistic evidence compiled in this review establishes uric acid as a significant disruptor of hepatic and adipose tissue lipid handling, with particular relevance to diabetic dyslipidemia. Through multiple interconnected pathways including ER stress activation, miRNA dysregulation, oxidative stress induction, and direct enzymatic effects, uric acid promotes a metabolic environment conducive to lipid accumulation and systemic dyslipidemia. The emerging role of adipose tissue as an active site of uric acid production, especially under hypoxic conditions present in expanded adipose tissue, adds complexity to our understanding of the relationship between hyperuricemia and obesity.

The lipidomic signatures characteristic of hyperuricemia, particularly in the context of diabetes, highlight specific disturbances in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways. These signatures not only provide insights into disease mechanisms but also offer potential biomarkers for identifying individuals at risk for progressive metabolic disease. The partial mediation of uric acid-lipid relationships by adipokines like RBP4 suggests complex tissue crosstalk in the metabolic response to elevated uric acid.

Future research directions should include deeper investigation of tissue-specific uric acid transporters in lipid metabolic disturbances, exploration of circadian influences on uric acid metabolism and lipid handling, and development of dual-target therapeutic approaches that simultaneously address hyperuricemia and associated dyslipidemia. The integration of multi-omics approaches including genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics with lipidomic data will further elucidate the complex networks linking uric acid metabolism to lipid homeostasis in diabetic populations.

Disorders of lipid metabolism are a cornerstone of the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and its associated complications. The intricate relationship between diabetic pathology and elevated serum uric acid (hyperuricemia) is increasingly recognized, with lipidomic dysregulation serving as a critical interface. Glycerophospholipids, glycerolipids, and sphingolipids represent three crucial lipid classes that undergo significant remodeling in the diabetic state, particularly when concurrent hyperuricemia is present. These alterations are not merely biomarkers of disease but actively contribute to disease progression through mechanisms including insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, inflammatory activation, and the development of vascular and renal complications. Advanced mass spectrometry-based lipidomics has begun to unravel the complex and specific changes within these lipid families, providing unprecedented insights for developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for a patient population with significant unmet clinical needs [11] [19].

Quantitative Lipid Alterations in Diabetic Patients with High Uric Acid

Comprehensive lipidomic profiling reveals distinct quantitative changes in glycerophospholipids, glycerolipids, and sphingolipids in diabetic patients, with further modulation in the presence of hyperuricemia. The tables below synthesize key findings from recent clinical and preclinical studies.

Table 1: Alterations in Glycerophospholipid and Glycerolipid Metabolites

| Lipid Class | Specific Metabolites | Change in DM vs. Control | Change in DH vs. DM | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) e.g., PC (36:1) | Conflicting Reports [20] | Significantly Upregulated [11] | Membrane integrity, cell signaling |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) e.g., PE (18:0/20:4) | Not Specified | Significantly Upregulated [11] | Membrane curvature, autophagy | |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not Specified | Downregulated [11] | Insulin signaling, vesicle trafficking | |

| Glycerolipids | Triglycerides (TGs) e.g., TG (16:0/18:1/18:2) | Established Risk Factor [19] | 13 TGs Significantly Upregulated [11] | Energy storage, lipotoxicity |

Table 2: Alterations in Sphingolipid Metabolites

| Sphingolipid Metabolite | Change in T2DM/Pre-DM vs. Control | Association with Complications | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P/So1P) | Gradually decreases from control to pre-DM to T2DM [21] | Predictor of elevated CVD risk [21] | Cell proliferation, migration, vascular integrity |

| Sphinganine (Sa) | Decreased in pre-DM & T2DM [21] | Indicator of CVD complications [21] | Ceramide synthesis precursor |

| Dihydro-S1P (dhS1P) | Baseline levels elevated prior to T2DM onset [22] | Associated with increased diabetes risk [22] | Regulation of insulin resistance & β-cell function |

| Ceramide (Cer) | Long-chain and ultra-long-chain Cer elevated in DKD [19] | Insulin resistance, apoptosis, renal damage [23] [19] | Central hub of sphingolipid metabolism, cell stress |

| Sphingomyelin (SM) | "U" shaped change (decreases in pre-DM, rises in T2DM) [21] | Correlated with CVD [21] | Major membrane component |

Detailed Methodologies for Lipidomic Analysis

The robust identification and quantification of lipid species rely on sophisticated analytical platforms. The following sections detail the core experimental protocols cited in the literature.

Untargeted Lipidomics by LC-MS

This methodology is designed for the broad-scale profiling of lipid species in biological samples.

- Sample Preparation: Fasting serum or plasma samples are collected and stored at -80°C. For analysis, samples are thawed, and proteins are precipitated using cold methanol. An internal standard (e.g., L-2-chlorophenylalanine) is added for quality control. The mixture is vortexed and centrifuged, and the supernatant is collected for analysis. Quality control (QC) samples are prepared by pooling an aliquot from all samples [20] [11].

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separation is typically performed using Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) systems. A common stationary phase is a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm). The mobile phase often consists of a binary solvent system, for example, (A) 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water and (B) 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol, under a gradient elution [11].

- Mass Spectrometry: Detection is carried out using a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., QTrap5500). Data can be acquired in a data-dependent MS/MS (dd-MS2) mode for metabolite identification, with a full-scan mass resolution of 17,000 at m/z 200 [20]. Electrospray ionization (ESI) is standard, and analysis is performed in both positive and negative ion modes to capture a wide range of lipids.

- Data Processing: Raw data are processed using software to perform peak picking, alignment, and identification by matching against standard compound libraries. Multivariate statistical analyses like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) are used to identify differentially expressed lipids [11].

Targeted Sphingolipid Analysis by HPLC-MS/MS

This protocol provides precise quantification of specific sphingolipid metabolites.

- Sample Extraction: Serum samples (e.g., 100 μL) are mixed with deuterated internal standards (e.g., S1P-d7). Lipids are extracted using a solution of isopropanol/methanol/formic acid (45:45:10, v/v). The mixture is vortexed, sonicated, and centrifuged. The supernatant is diluted and injected into the HPLC-MS/MS system [22].

- HPLC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separation is achieved on an analytical column (e.g., Agilent Eclipse XDB-C8) using a gradient elution with mobile phases such as (A) methanol/water/formic acid with ammonium formate and (B) methanol/tetrahydrofuran/formic acid with ammonium formate [22].

- Mass Spectrometry: The mass spectrometer is operated in positive-ion electrospray ionization (ESI) mode with Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for high sensitivity and specificity. This allows for the targeted quantification of metabolites like sphingosine (Sph), sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), dihydrosphingosine (dhSph), and dihydro-S1P (dhS1P) [21] [22].

- Quantification: Concentrations of target analytes are determined by calculating the ratio of their peak areas to the peak areas of the corresponding internal standards, using calibration curves constructed from authentic standards.

Pathway Diagrams and Metabolic Interrelationships

Sphingolipid Metabolism and Signaling Pathway

The sphingolipid pathway is a dynamic network where the balance between metabolites dictates cellular fate. Ceramide, the central hub, can be synthesized de novo from serine and palmitoyl-CoA, a reaction catalyzed by the rate-limiting enzyme serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT). It can also be generated from the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin by sphingomyelinases (SMases). Ceramide is metabolized to sphingosine, which is subsequently phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases (SphK1 and SphK2) to produce sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P). This conversion is a critical "rheostat," as ceramide and sphingosine typically promote apoptosis and cell stress, while S1P favors cell proliferation and survival. In diabetes, this balance is disrupted, with evidence pointing to elevated ceramides contributing to insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction, and altered S1P levels associated with cardiovascular complications. The diagram below illustrates these key metabolic and signaling relationships [21] [23] [22].

Experimental Workflow for Lipidomics

A typical integrated workflow for a lipidomic study, from sample collection to biological interpretation, involves multiple critical steps as illustrated below. This process enables the systematic identification of lipid signatures associated with diabetes and hyperuricemia [20] [11] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful lipidomic research requires a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table catalogues key solutions used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Lipidomics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC/MS-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase for chromatographic separation; ensures minimal background noise and high sensitivity. | 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water; methanol; isopropanol; methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [11]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization of extraction efficiency, instrument variability, and quantitative accuracy. | S1P-d7; L-2-chlorophenylalanine [20] [22]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Purification and class-specific fractionation of complex lipid mixtures from biological samples. | Not explicitly detailed in results, but standard practice in lipidomics for clean-up. |

| UPLC BEH C18 Column | Reverse-phase chromatography column for separating a wide range of lipid species based on hydrophobicity. | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) [11]. |

| Potassium Oxonate (PO) | Uricase inhibitor used to induce hyperuricemia in animal models for mechanistic studies. | Intragastric administration at 350 mg/kg with adenine and fructose water to establish hyperuricemic diabetic models [9]. |

| Enzyme Activity Assays | Measurement of key enzymatic activities in lipid metabolism pathways (e.g., SphK, SPT). | Assays for liver xanthine oxidase activity to confirm hyperuricemic state [9]. |

| Olcegepant hydrochloride | Olcegepant hydrochloride, MF:C38H48Br2ClN9O5, MW:906.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Benalfocin hydrochloride | Benalfocin hydrochloride, CAS:86129-54-6, MF:C11H15Cl2N, MW:232.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion and Pathophysiological Implications

The coordinated dysregulation of glycerophospholipids, glycerolipids, and sphingolipids creates a deleterious lipid environment that exacerbates diabetes pathology, particularly in the context of high uric acid. Glycerophospholipid remodeling, especially in pathways involving PC and PE, directly impacts membrane fluidity, signal transduction, and the production of inflammatory mediators. The significant upregulation of specific triglycerides in DH patients points to a pronounced state of lipotoxicity, where lipid oversupply overwhelms storage capacity and leads to ectopic lipid deposition, insulin resistance, and cellular dysfunction in tissues like the pancreas, liver, and kidney [11] [19].

The role of the sphingolipid rheostat is particularly critical. The shift in balance towards pro-apoptotic and pro-resistance molecules like ceramide, and away from protective mediators like S1P and dhS1P, creates a cellular environment prone to failure. The finding that dhS1P and the dhS1P/dhSph ratio are elevated prior to diabetes onset suggests that sphingolipid dysregulation is an early event in pathogenesis, offering a potential window for early intervention [22]. These lipid alterations are not confined to systemic circulation but are also manifest at the tissue level in complications such as Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD), where injured renal cells exhibit increased lipid biosynthetic activity [24] [19].

In conclusion, the intricate interplay between glycerophospholipid, glycerolipid, and sphingolipid metabolism underlies the complex pathophysiology of diabetes and hyperuricemia. The distinct lipidomic signatures uncovered through advanced LC-MS/MS platforms provide a powerful resource for biomarker discovery and the development of targeted therapies aimed at restoring lipid metabolic homeostasis in this high-risk patient population.

The gut-liver-kidney axis represents a critical physiological network of interconnected organs that communicate bidirectionally through metabolic pathways, neural signaling, and inflammatory mediators, with the gut microbiota serving as a central regulator of this system. This axis has gained substantial research attention as studies reveal the fundamental roles that gut microbiota and their metabolites play in the development and progression of liver and kidney diseases [25]. Within the context of diabetic complications, particularly in patients with concurrent hyperuricemia, this axis becomes increasingly relevant as dysbiosis can lead to elevated production of harmful uremic toxins, impaired lipid metabolism, and progressive renal dysfunction [25] [26]. The intricate relationship between uric acid metabolism and gut microbiota involves a bidirectional interaction that influences both the host's gut environment and systemic metabolic homeostasis [9].

Understanding this axis is essential for creating targeted therapies that can modulate gut microbiota to enhance the health of both the liver and kidneys, particularly in complex metabolic scenarios such as diabetes with hyperuricemia where lipidomic disturbances are prominent [27] [11]. This technical review explores the mechanisms connecting the gut, liver, and kidneys within the framework of lipidomic research in diabetic patients with high uric acid, with emphasis on pathological mechanisms, advanced research methodologies, and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting this axis.

Physiological Mechanisms of the Gut-Liver-Kidney Axis

Gut Microbiota Composition and Metabolic Functions

The gut microbiota constitutes a diverse community of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, that colonize the gastrointestinal tract and play vital roles in host digestion, metabolism, and immune system regulation [25]. The primary bacterial phyla include Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria, each performing specific metabolic functions [25] [26]. Firmicutes are particularly important for fermenting dietary fibers into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which provide energy to colon cells and exert anti-inflammatory properties [25] [26]. Bacteroidetes specialize in breaking down complex carbohydrates, thereby enhancing nutrient absorption, while genera such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (under Actinobacteria) are recognized for their probiotic effects, promoting gut health and modulating immune responses [25].

The composition of the gut microbiota is dynamic and influenced by various factors including diet, age, genetics, and environmental exposures [25]. Maintaining a balanced gut microbiota is crucial for metabolic stability, immune system performance, and defense against pathogens. When dysbiosis (an imbalance in gut microbiota composition) occurs, it is characterized by decreased microbial diversity and an increase in harmful bacteria, leading to negative health consequences including metabolic disorders, inflammatory diseases, and neurological conditions [25] [26].

Gut-Liver Communication Pathways

The gut-liver axis serves as a two-way communication pathway where gut-derived metabolites and microbial products directly influence liver function via the portal vein [25] [26]. The liver is continuously exposed to substances from the gut, including microbial metabolites such as SCFAs, bile acids (BAs), and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [25] [26]. Among these, SCFAs and BAs primarily focus on metabolic regulation and signal transmission, while LPS mainly affects liver function through inflammatory pathways [25]. These metabolites play significant roles in modulating liver metabolism and immune responses, and can even aid in liver regeneration following injury [25].

The liver, as the body's primary metabolic organ, is crucial for regulating various metabolic processes, including lipid and glucose homeostasis [25]. It detoxifies harmful substances and produces vital proteins, with its metabolic and detoxification capacities being significantly influenced by gut microbiota products [25]. For instance, SCFAs generated during the fermentation of dietary fibers by gut microbiota can improve liver function and reduce inflammation [25]. Dysbiosis has been associated with various liver diseases, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and hepatitis, highlighting the critical need to maintain a healthy gut microbiome to prevent liver-related health issues [25] [26].

Gut-Kidney Interaction Mechanisms

The connection between gut microbiota and kidney health, often referred to as the gut-kidney axis, has emerged as an important area of research [25] [26]. The kidneys play a crucial role in filtering blood, maintaining fluid balance, and eliminating waste products from the body [25]. Dysbiosis can lead to increased production of harmful substances called uremic toxins, which negatively impact kidney function and can accelerate the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [25] [26]. For example, changes in the composition of gut microbiota have been linked to elevated levels of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, both known to cause kidney damage [25].

Furthermore, certain metabolites produced by gut microbes can affect kidney inflammation and fibrosis, suggesting that restoring a healthy gut microbiome might provide a promising therapeutic approach for kidney diseases [25] [26]. This interaction between gut microbiota and kidney function underscores the critical need for a balanced microbiome to support renal health and prevent disease progression, particularly in the context of diabetic kidney injury where uric acid metabolism is disrupted [28] [9].

Integrated Cross-Organ Communication

The gut-liver-kidney axis functions as an integrated system where disturbances in one organ inevitably affect the others through shared metabolic pathways and signaling mechanisms [25]. The liver processes metabolites originating from the gut, which can have widespread effects on kidney health, creating a feedback loop that may influence disease progression [25] [26]. Similarly, renal dysfunction can alter gut microbiota composition through uremic toxins, completing a vicious cycle of metabolic disturbance [26]. This complex interorgan communication is particularly relevant in diabetic patients with hyperuricemia, where systemic metabolic disturbances create a pathological environment that engages all three organs simultaneously [11] [19] [28].

Lipidomic Disturbances in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

Analytical Approaches to Lipidomic Profiling

Advanced lipidomic technologies have enabled comprehensive characterization of lipid disturbances in metabolic diseases. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for untargeted lipidomic analysis, allowing identification and quantification of hundreds of lipid species across multiple subclasses [11]. In typical experimental workflows, plasma samples are processed using liquid-liquid extraction methods with methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) as the organic solvent, followed by chromatographic separation on reversed-phase C18 columns [11]. Mobile phases often consist of acetonitrile-water mixtures with ammonium formate as an additive for positive ionization mode, and acetonitrile-isopropanol mixtures for negative ionization mode [11]. Quality control measures include randomization of sample analysis, insertion of quality control samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 samples), and assessment of coefficient of variation to ensure analytical reproducibility [27] [11].

Table 1: Key Lipid Classes Identified in Lipidomic Studies of Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

| Lipid Class | Abbreviation | Trend in DH vs Controls | Specific Examples | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triacylglycerols | TAG | Significantly upregulated | TAG (16:0/18:1/18:2), TAG (53:0) | Energy storage, associated with de novo lipogenesis |

| Diacylglycerols | DAG | Significantly upregulated | DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5) | Signaling lipids, precursors to complex lipids |

| Phosphatidylcholines | PC | Both up and downregulated | PC (16:0/20:5), PC (36:1) | Membrane integrity, signaling precursors |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines | PE | Significantly upregulated | PE (18:0/20:4) | Membrane fluidity, cellular signaling |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines | LPC | Downregulated | LPC (20:2) | Anti-inflammatory properties, signaling lipids |

| Phosphatidylinositols | PI | Downregulated | Not specified | Cell signaling, membrane trafficking |

Characteristic Lipidomic Signatures

Lipidomic studies reveal distinct perturbations in patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH) compared to those with diabetes alone (DM) or healthy controls. Comprehensive profiling has identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses that demonstrate significant alterations in DH patients [11]. Multivariate analyses including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) confirm distinct lipidomic profiles that effectively separate DH, DM, and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) groups [11].

Specific lipid signatures associated with hyperuricemia risk in diabetic patients include elevated levels of specific glycerolipids and glycerophospholipids [27]. In a large study of middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals, after multivariable adjustment including BMI and lifestyle factors, 123 lipids were significantly associated with uric acid levels, predominantly glycerolipids (GLs) and glycerophospholipids (GPs) [27]. Notably, specific diacylglycerols [DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5), DAG (18:1/22:6)], phosphatidylcholines [PC (16:0/20:5)], and triacylglycerols [TAG (53:0)] emerged as the most significant lipid signatures positively associated with hyperuricemia risk, while lysophosphatidylcholine [LPC (20:2)] was inversely associated with hyperuricemia risk [27]. Network analysis further supported a positive association between TAGs/PCs/DAGs contained module and hyperuricemia risk [27].

Table 2: Key Altered Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

| Metabolic Pathway | Impact Value | Key Lipid Species Involved | Enzymes/Regulators | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.199 | PC, PE, LPC, PI | Phospholipases, acyltransferases | Membrane dysfunction, altered signaling |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 0.014 | TAG, DAG | DGAT, lipases | Lipid storage, insulin signaling disruption |

| De novo lipogenesis | Not quantified | DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6) | FASN, SCD1 | Lipotoxicity, ectopic fat deposition |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | Not quantified | Ceramide, S1P, GM3 | Sphingomyelinases, ceramidases | Insulin resistance, inflammation |

Pathophysiological Implications of Lipidomic Changes

The observed lipidomic alterations in diabetes with hyperuricemia have significant functional implications. HUA-related lipids are associated with de novo lipogenesis fatty acids, especially 16:1n-7, with Spearman correlation coefficients ranging from 0.32 to 0.41 (p < 0.001) [27]. This suggests that enhanced lipogenesis contributes substantially to the lipid disturbances observed in hyperuricemic states. Furthermore, reduced rank regression analyses indicate that specific dietary patterns influence both hyperuricemia risk and associated lipid profiles, with increased aquatic products intake correlating with elevated hyperuricemia risk and HUA-associated lipids, while high dairy consumption correlates with lower levels of HUA-associated lipids [27].

Mediation analyses suggest that the associations between specific lipids and hyperuricemia are partially mediated by retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), an adipokine linked with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, with mediation proportions ranging from 5% to 14% [27]. This indicates that RBP4 may serve as an important mechanistic link between disturbed lipid metabolism and hyperuricemia in the context of diabetes. Additionally, the uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio (UHR) has emerged as a significant biomarker, with studies demonstrating that a 0.1 point increase in UHR increases diabetic kidney injury odds by 2.3 times, highlighting the clinical relevance of the interplay between uric acid and lipid metabolism [28].

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Animal Models of Combined Metabolic Disturbances

Appropriate animal models are essential for investigating the complex interactions between diabetes, hyperuricemia, and lipid metabolism. The Golden Syrian hamster has emerged as a particularly suitable model for such studies due to its similarity to humans in hepatic lipid metabolism and cholesteryl ester transfer protein activities [9]. The effects of dietary cholesterol on blood lipid profiles in hamsters closely resemble those observed in humans, making them superior to rats and mice for modeling complex metabolic disorders [9].

A well-characterized experimental approach involves inducing diabetes in hamsters through intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ) at 30 mg/kg once daily for 3 consecutive days, followed by verification of diabetes through fasting blood glucose concentrations exceeding 12 mmol/L after ten days [9]. Hyperuricemia is then induced through administration of potassium oxonate (PO), a selectively competitive inhibitor of uricase, at doses of 350 mg/kg in combination with adenine (150 mg/kg) and 5% fructose water [9]. This combined intervention successfully establishes a model with characteristic features of diabetes, hyperuricemia, and dyslipidemia, with reported serum levels of uric acid reaching 499.5 ± 61.96 μmol/L, glucose 16.88 ± 2.81 mmol/L, triglyceride 119.88 ± 27.14 mmol/L, and total cholesterol 72.92 ± 16.62 mmol/L [9].

Analytical Assessment Methods

Comprehensive characterization of the gut-liver-kidney axis in experimental models involves multiple analytical approaches. Serum biochemical parameters including uric acid, glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, urea nitrogen, and creatinine are typically measured using automated analyzers with commercial kits [27] [9]. Tissue antioxidant parameters such as hepatic xanthine oxidase activity provide insights into oxidative stress pathways [9]. Histopathological examination of renal tissues assesses glomerular mesangial cells and matrix proliferation, protein casts, and urate deposition, providing structural correlates to functional impairments [9].

Molecular analyses include measurement of gene expression patterns for key regulators such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which are typically elevated in diabetic kidney injury [9]. Assessment of gut microbiota composition through 16S rRNA sequencing, combined with quantification of fecal short-chain fatty acids via gas chromatography, provides comprehensive characterization of microbial communities and their metabolic outputs [9]. These integrated approaches allow researchers to establish correlations between specific bacterial taxa, metabolic parameters, and pathological outcomes, enabling a systems-level understanding of the gut-liver-kidney axis.

Clinical Assessment and Biomarker Validation

In human studies, the uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio (UHR) has emerged as a clinically accessible biomarker that integrates information about both purine and lipid metabolism [1] [7] [28]. Calculation of UHR follows a straightforward formula: UHR = uric acid (mg/dL) / HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) [1] [7]. Large-scale epidemiological studies involving over 17,000 participants from the NHANES database have demonstrated that higher UHR quartiles translate to increased risk of diabetic nephropathy, with a 44% increased risk for every unit rise in UHR (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.23-1.69) [1]. The area under the curve (AUC) for UHR in predicting diabetic nephropathy risk was 0.617, indicating modest discriminatory capability [1].

Additional clinical assessments include measurement of albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) for diagnosis of diabetic kidney injury, with ACR ≥30 µg/mg considered diagnostic for diabetic nephropathy [1]. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimation using established equations such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation for Chinese populations provides complementary information about renal function [27]. These clinical parameters, when combined with lipidomic profiling, offer a comprehensive approach to stratifying patients and understanding individual variations in disease progression.

Visualization of Metabolic Pathways

Gut-Liver-Kidney Axis Signaling Pathways

Gut-Liver-Kidney Axis Signaling Pathways

This diagram illustrates the bidirectional communication between gut, liver, and kidney tissues, with the gut microbiota serving as a central regulator. The pathway highlights how microbial metabolites including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and bile acids (BAs) transit through the portal vein to influence liver function, while processed metabolites from the liver subsequently affect kidney health. The detrimental consequences of dysbiosis are shown in the dashed box, demonstrating how microbial imbalance leads to increased intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and elevated uremic toxins that collectively contribute to organ dysfunction.

Lipidomic Workflow in Metabolic Research

Lipidomic Analysis Workflow

This workflow diagram outlines the standard procedures for comprehensive lipidomic analysis in metabolic research, from sample collection through data interpretation. The process begins with plasma collection followed by lipid extraction using methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) methods, chromatographic separation via UHPLC with C18 columns, and mass spectrometric analysis using QTRAP systems. Critical quality control measures are shown in the dashed box, including insertion of quality control samples at regular intervals and assessment of coefficient of variation to ensure analytical reproducibility. Subsequent data processing, multivariate statistical analysis, and pathway analysis enable identification of significantly altered lipid species and metabolic pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gut-Kidney-Liver Axis Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipidomic Analysis | MTBE, ammonium formate, C18 columns | Lipid extraction and separation | Solvent for lipid extraction, mobile phase additive, chromatographic separation |

| Mass Spectrometry | SCIEX 5500 QTRAP, Analyst software | Lipid identification and quantification | High-sensitivity detection, data acquisition, and processing |

| Animal Modeling | Streptozotocin (STZ), potassium oxonate, adenine | Induction of diabetes and hyperuricemia | Pancreatic β-cell destruction, uricase inhibition, renal injury induction |

| Molecular Biology | ELISA kits for RBP4, TGF-β, PAI-1 antibodies | Protein quantification and expression | Measurement of adipokines, fibrotic factors, and inflammatory markers |

| Microbiome Analysis | 16S rRNA primers, gas chromatography systems | Microbial community profiling and SCFA measurement | Bacterial identification and quantification, microbial metabolite analysis |

| Histopathology | Hematoxylin and eosin, Masson's trichrome | Tissue structure and fibrosis assessment | Morphological evaluation, collagen deposition visualization |

The gut-liver-kidney axis represents a sophisticated network of interorgan communication in which the gut microbiota serves as a central regulator, particularly in the context of diabetes with concurrent hyperuricemia. Lipidomic studies have revealed characteristic disturbances in glycerolipid and glycerophospholipid metabolism that distinguish patients with combined diabetic hyperuricemia from those with diabetes alone. The emerging role of the uric acid to HDL cholesterol ratio as a clinically accessible biomarker underscores the interconnected nature of purine and lipid metabolism in diabetic complications.

Future research directions should focus on developing targeted interventions that modulate specific aspects of this axis, potentially through dietary strategies that influence HUA-associated lipids or through direct modulation of gut microbiota composition. The experimental methodologies and analytical approaches outlined in this review provide a foundation for systematic investigation of this complex physiological network, with potential applications in drug development, personalized medicine, and nutritional interventions for metabolic diseases.

The interplay between uric acid (UA) and insulin resistance (IR) represents a critical nexus in metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and cardiovascular disease pathogenesis. Hyperuricemia, defined as serum uric acid (SUA) exceeding 6.8 mg/dL, is traditionally associated with gout and nephrolithiasis but is increasingly recognized as a contributor to metabolic dysfunction through inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways [29]. Epidemiological evidence indicates that hyperuricemia increases the risk of developing T2DM by 1.6 to 2.5 times, suggesting a pathophysiological relationship beyond mere association [29]. This technical review examines the mechanistic pathways connecting elevated uric acid to impaired insulin signaling, focusing on the interplay between inflammatory cascades, oxidative stress, and emerging connections to lipidomic disruptions in diabetic patients.

The clinical relevance of this relationship is particularly pronounced in diabetic populations, where comorbid dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia create a pathological synergy. A cross-sectional study of 230 hospitalized diabetic patients revealed that abnormal SUA levels were significantly associated with elevated triglycerides (TG), with 77% of patients with SUA >6.8 mg/dL exhibiting TG >150 mg/dL compared to 55% in those with normal uric acid levels [13]. This statistical relationship (P=0.03) underscores the clinical interconnection between purine metabolism and lipid regulation in diabetes. Furthermore, recent investigations have identified the uric acid to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (UHR) as a promising biomarker, with thresholds of 5.02 for depressive symptoms and 4.00 for anxiety symptoms identified in T2DM patients, highlighting the intersection of metabolic and neuropsychiatric health in this population [8].

Table 1: Clinical Evidence Linking Uric Acid to Metabolic Parameters in Human Studies

| Study Population | Key Finding | Statistical Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 285 T2DM patients | UHR >5.02 associated with worsened depressive symptoms | β=1.55, 95%CI: 0.57-2.53 | [8] |

| 285 T2DM patients | UHR >4.00 associated with worsened anxiety symptoms | β=0.72, 95%CI: 0.35-1.09 | [8] |

| 230 diabetic inpatients | Abnormal SUA associated with elevated triglycerides | P=0.03 | [13] |

| 1,835 newly diagnosed CAD patients | TyG index mediated UA-CAD relationship (18.89%) | P=0.026 | [30] |

| Non-diabetic Finnish adults (n=2322) | SUA >400 μmol/L associated with increased HOMA-IR | Adjusted β=0.21, 95%CI: 0.17-0.25 | [31] |

Molecular Mechanisms: Inflammatory and Oxidative Pathways

Inflammatory Bridges Between Hyperuricemia and Insulin Resistance

The pathophysiological relationship between hyperuricemia and insulin resistance is fundamentally mediated through chronic low-grade inflammation. Uric acid contributes to a pro-inflammatory state through multiple interconnected mechanisms. At the cellular level, elevated SUA promotes endothelial dysfunction by impairing insulin-dependent nitric oxide stimulation in endothelial cells, thereby disrupting vascular function and insulin signaling [29]. Soluble uric acid enters vascular smooth muscle cells, where it activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathways, leading to increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [32] [29].

The inflammatory cascade is further amplified through activation of the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which senses cellular stress and facilitates the maturation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18) [32]. These cytokines establish a feed-forward loop of inflammation that directly interferes with insulin signaling. Specifically, inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibit insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation and Akt activation, thereby reducing glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation to the plasma membrane and diminishing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues [32] [33]. This molecular interference creates a state of insulin resistance that further exacerbates metabolic dysfunction.

Oxidative Stress as a Unifying Pathway

Parallel to inflammatory activation, uric acid induces oxidative stress through multiple mechanisms that converge on insulin resistance. Elevated SUA promotes generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via activation of NADPH oxidase and mitochondrial oxidative pathways [33] [29]. In diabetic hamster models, high uric acid levels were closely associated with decreased antioxidant capacity, creating a redox imbalance that promotes cellular damage [9]. Uric acid directly inhibits AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity, a critical energy sensor that regulates glucose uptake and mitochondrial biogenesis [9].

The oxidative stress induced by hyperuricemia has particularly detrimental effects on pancreatic β-cell function. Studies demonstrate that uric acid promotes pancreatic β-cell death through oxidative damage, though alone it may be insufficient to induce diabetes [9] [29]. This oxidative damage to β-cells compounds the existing insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, creating a synergistic deterioration of glucose homeostasis. The resulting hyperglycemia further amplifies oxidative stress through formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), establishing a vicious cycle of metabolic deterioration [32] [33].

Table 2: Key Oxidative and Inflammatory Mediators in Uric Acid-Induced Insulin Resistance

| Mediator | Source | Mechanism in Insulin Resistance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Macrophages, adipocytes | Induces serine phosphorylation of IRS-1; reduces GLUT4 expression | 2-3 fold increase in diabetic patients [33] |

| IL-6 | Hepatocytes, immune cells | Suppresses IRS-1 phosphorylation; inhibits Akt activation | Elevated in T2DM; correlates with HbA1c [33] |

| ROS | Mitochondrial respiration, NADPH oxidase | Damages cellular components; activates stress kinases (JNK, IKKβ) | Decreased antioxidant capacity in hyperuricemic diabetic models [9] |

| CRP | Liver (IL-6 induced) | Promotes endothelial dysfunction; inhibits insulin signaling | Elevated in T2DM patients; marker of systemic inflammation [33] |

| NLRP3 inflammasome | Immune cells | Activates caspase-1; processes pro-IL-1β to active form | Links metabolic stress to inflammation in diabetes [32] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Animal Models of Hyperuricemia and Diabetes

Animal models have been instrumental in elucidating the causal relationships between hyperuricemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes complications. The streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic hamster model represents a robust approach for studying hyperuricemia in the context of diabetes. In this model, diabetes is induced in male Golden Syrian hamsters (10 weeks old, 163±7.43g) by intraperitoneal injection of STZ (30 mg/kg) once daily for 3 consecutive days [9]. After ten days, animals with fasting blood glucose >12 mmol/L are selected for hyperuricemia induction through potassium oxonate (PO) treatment (intragastric administration of 350 mg/kg PO plus 150 mg/kg adenine with 5% fructose water) while being maintained on either standard diet or high-fat/cholesterol diet (HFCD) [9].

This combinatorial approach successfully establishes a diabetic-hyperuricemic-dyslipidemic model with serum parameters reaching 499.5±61.96 μmol/L for UA, 16.88±2.81 mmol/L for glucose, and 119.88±27.14 mmol/L for triglycerides after 4 weeks [9]. The model demonstrates synergistic effects of PO treatment and HFCD on increasing uric acid, urea nitrogen, creatinine levels, liver xanthine oxidase activity, and renal expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [9]. Histopathological examination reveals glomerular mesangial cells and matrix proliferation, protein casts, and urate deposition, providing a comprehensive platform for investigating the interplay between multiple metabolic disturbances.

Human Population Studies and Clinical Assessments

In human research, multiple study designs have been employed to investigate the uric acid-insulin resistance relationship. The GOOD Ageing in Lahti region (GOAL) study exemplifies a prospective, population-based approach, examining 2322 non-diabetic Finnish individuals aged 52-76 years [31]. This study utilized comprehensive data collection including SUA, fasting plasma glucose, insulin levels, and other laboratory parameters alongside comorbidities, lifestyle habits, and socioeconomic factors.

Insulin resistance was assessed using the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), calculated as (fasting plasma insulin [μU/mL] × fasting plasma glucose [mg/dL])/405, with a threshold of ≥2.65 indicating insulin resistance [31]. Statistical analyses employed multivariate linear regression to identify relationships between SUA as a continuous variable and insulin resistance measurements, with potential nonlinearity assessed using 4-knot-restricted cubic spline general linear models [31]. This approach revealed that SUA levels above 400 μmol/L (≈6.7 mg/dL) were associated with a drastic rise in HOMA-IR (adjusted β=0.21, 95%CI: 0.17-0.25), demonstrating a threshold effect rather than a linear relationship [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Assays for Investigating UA-IR Pathways

| Reagent/Assay | Specific Function | Application Example | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Oxonate (PO) | Uricase inhibitor; induces hyperuricemia | Establishing animal models of hyperuricemia | Administered at 350 mg/kg with adenine (150 mg/kg) in 0.5% CMC-Na [9] |

| HOMA-IR Calculation | Surrogate index of insulin resistance | Epidemiological studies | (Fasting insulin [μU/mL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL])/405; cutoff ≥2.65 [31] |

| Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) Index | Marker of insulin resistance; ln[FPG(mg/dl)×TG(mg/dl)/2] | Assessing CAD severity in relation to UA | Cutoff >9.33 identifies high IR risk; mediates UA-CAD relationship [30] |

| ELISA Kits (SOD, GPX1, CAT) | Quantify antioxidant enzyme activity | Measuring oxidative stress in diabetes | Significant alterations in diabetic patients vs controls (p<0.001) [33] |

| Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors (allopurinol, febuxostat) | Lower SUA by inhibiting xanthine oxidase | Intervention studies | Inconsistent effects on insulin sensitivity in clinical trials [29] |

| Cytokine Panels (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) | Quantify inflammatory markers | Assessing low-grade inflammation | Elevated in T2DM; correlate with SUA and IR [32] [33] |

| 7-Hydroxydichloromethotrexate | 7-Hydroxydichloromethotrexate|CAS 751-75-7 | 7-Hydroxydichloromethotrexate is a metabolite of methotrexate and dichloromethotrexate for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Decarbamoylmitomycin C | Decarbamoylmitomycin C, CAS:26909-37-5, MF:C14H17N3O4, MW:291.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integration with Lipidomic Profiles in Diabetic Research

The relationship between uric acid and insulin resistance must be understood within the broader context of lipidomic disruptions in diabetes. Recent lipidomics approaches have revealed profound alterations in lipid metabolism associated with diabetic kidney disease (DKD), including significant changes in lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPEs), lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), and sphingomyelins (SMs) [34]. These lipid species represent not only biomarkers of disease progression but also active mediators in the inflammatory and oxidative pathways linking uric acid to insulin resistance.

Uric acid exacerbates dyslipidemia through multiple mechanisms, including reduced lipoprotein lipase activity, increased hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) production, and promotion of oxidative modification of lipids [9] [13]. The resulting lipid abnormalities create a pro-inflammatory milieu that further amplifies insulin resistance. Specifically, elevated triglycerides and small dense LDL particles characteristic of diabetic dyslipidemia promote endothelial dysfunction and impair insulin signaling, creating a vicious cycle with hyperuricemia-induced inflammation [13]. This integrated perspective highlights the necessity of considering uric acid within the broader lipidomic landscape when investigating insulin resistance in diabetic populations.