Fragment-Based Drug Discovery for PPI Modulation: Cracking the 'Undruggable' Code

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs), once considered 'undruggable' due to their flat and extensive interfaces, are now being successfully targeted thanks to fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD).

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery for PPI Modulation: Cracking the 'Undruggable' Code

Abstract

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs), once considered 'undruggable' due to their flat and extensive interfaces, are now being successfully targeted thanks to fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD). This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging FBDD to identify and optimize PPI modulators. We explore the foundational principles of PPIs and FBDD, detail the integrated workflow from fragment screening to lead generation, address key challenges in optimization, and validate the approach through clinical success stories. The content synthesizes current methodologies, troubleshooting strategies, and future directions, highlighting how FBDD has become a premier strategy for pioneering therapeutics against challenging targets in oncology, immunology, and beyond.

Understanding the Landscape: From Undruggable PPIs to Fragment-Based Opportunities

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) represent a formidable frontier in drug discovery, governing virtually all cellular processes from signal transduction to apoptosis. The human interactome, estimated to comprise up to approximately 650,000 interactions, presents a vast therapeutic landscape that remains largely untapped [1] [2]. Historically, PPIs were deemed "undruggable" due to their extensive, flat, and featureless interfaces that lack deep pockets traditionally targeted by small molecules [1] [3] [4]. These interfaces typically span 1,000-2,000 Ų, significantly larger than the 300-500 Ų surface areas characteristic of conventional drug-binding pockets [1] [2].

The paradigm shift in targeting PPIs emerged with the recognition of binding energy hot spots—localized regions within larger PPI interfaces where mutations (typically to alanine) cause substantial binding energy deficits (ΔΔG ≥ 2 kcal/mol) [5] [2]. These hot spots, often enriched with specific amino acids like tryptophan, tyrosine, and arginine, constitute the crucial energetic cores of PPIs and provide viable footholds for therapeutic intervention [1] [5]. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) has proven particularly effective for targeting these sites, with several compounds now in clinical trials and marketed drugs like venetoclax demonstrating the feasibility of this approach [1] [3] [6].

Defining Key Concepts and Quantitative Parameters

Characterizing PPI Interface Landscapes

The following table summarizes the fundamental structural and energetic properties that differentiate PPI interfaces from conventional drug targets, providing a quantitative framework for assessing their druggability.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PPI Interfaces Versus Conventional Drug Targets

| Parameter | PPI Interfaces | Conventional Drug Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Area | 1,000-6,000 Ų [1] [2] | 300-1,000 Ų [1] |

| Typical Binding Site | ~1,600 Ų ("standard size") [2] | 300-500 Ų [2] |

| Hot Spot Area | ~600 Ų (central region) [2] | Not applicable |

| Interface Topography | Flat, featureless, lacking deep pockets [1] [3] | Defined cavities and clefts [1] |

| Key Energetic Residues | Trp, Tyr, Arg, Asp, Leu, Phe [1] [5] | Varies by target class |

| Binding Affinity Contribution | Hot spots contribute disproportionately to binding energy [5] | More evenly distributed |

Hot Spot Energetics and Composition

Hot spots represent the functional epitopes within PPI interfaces, characterized by their exceptional contribution to binding free energy. The following table details the experimental and computational parameters used to define and identify these critical regions.

Table 2: Hot Spot Definition and Experimental Characterization

| Parameter | Technical Specification | Application in PPI Drugging |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Threshold | ΔΔG ≥ 2 kcal/mol upon alanine mutation [5] [2] | Identifies residues critical for binding |

| Primary Hot Spot Residues | Arg, Asp, Leu, Phe, Trp, Tyr [1] | Prioritize for mimicry in drug design |

| Experimental Identification | Alanine scanning mutagenesis [1] [5] | Quantifies residue-specific energy contributions |

| Computational Prediction | FTMap, GRID, MCSS [5] | Maps probe clusters to identify favorable binding regions |

| Fragment Screening | NMR, X-ray crystallography [1] [5] | Experimentally validates hot spot locations |

| Hot Region Architecture | Network of tightly packed hot spots [1] | Defines minimal pharmacophore for inhibition |

Experimental Protocols for Hot Spot Identification

Protocol 1: Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis for Hot Spot Validation

Purpose: To experimentally identify hot spot residues by quantifying their contribution to binding free energy.

Materials:

- Purified wild-type and mutant proteins

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) instrumentation

- Reaction buffers optimized for specific PPI

Procedure:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Systematically mutate interface residues to alanine using PCR-based techniques

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express wild-type and mutant proteins in appropriate expression system; purify to >95% homogeneity

- Binding Affinity Measurement:

- For ITC: Titrate one binding partner into cell containing other partner at constant temperature

- For SPR: Immobilize one partner on chip surface; measure binding kinetics of flowing partner

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate ΔΔG = -RTln(KD,mutant/KD,wild-type)

- Classify residues with ΔΔG ≥ 2 kcal/mol as hot spots

- Structural Validation: Confirm mutant proteins maintain proper folding via circular dichroism or analytical ultracentrifugation

Technical Notes: Include positive controls (known hot spots) and negative controls (non-interface residues). Account for potential structural perturbations by verifying mutant protein stability [5] [2].

Protocol 2: Crystallographic Fragment Screening for Hot Spot Mapping

Purpose: To experimentally map hot spots and identify fragment hits using X-ray crystallography.

Materials:

- Crystallized target protein

- Fragment library (typically 500-2,000 compounds)

- High-throughput crystallization and X-ray diffraction facilities

- Soaking apparatus

Procedure:

- Library Design: Curate fragment library with MW 150-250 Da, complying with Rule of Three for optimal coverage

- Protein Crystallization: Grow reproducible crystals of target protein using vapor diffusion or microbatch methods

- Fragment Soaking:

- Soak crystals in solutions containing individual fragments (typically 50-200 mM)

- Optimize soaking time (minutes to hours) and fragment concentration to maximize binding while preserving crystal quality

- Data Collection and Processing:

- Collect high-resolution (<2.5 Ã…) X-ray diffraction data

- Process data using HKL-2000 or XDS

- Structure Determination:

- Solve structures by molecular replacement

- Identify bound fragments in electron density maps

- Calculate ligand efficiency: LE = (-RTlnKD)/HA, where HA = number of heavy atoms

Technical Notes: Prioritize fragments with LE ≥ 0.3 kcal/mol/HA. Identify regions with multiple overlapping fragment binders as primary hot spots [1] [5].

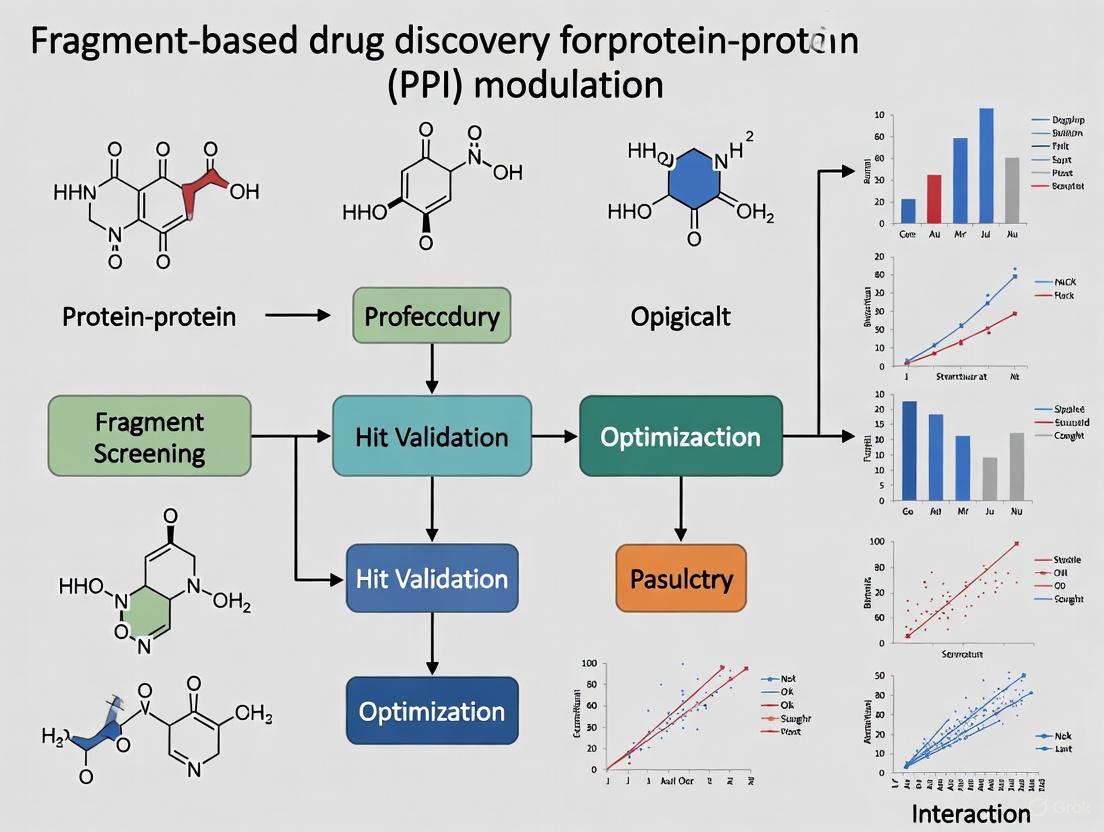

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for identifying and validating PPI hot spots

Computational Approaches for Hot Spot Prediction

Protocol 3: FTMap Computational Mapping of Binding Sites

Purpose: To computationally identify and rank binding hot spots using the FTMap algorithm.

Materials:

- Protein structure (PDB format)

- FTMap server access or local installation

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or homology modeling

- Remove bound ligands and water molecules

- Add hydrogen atoms and optimize side-chain conformations

- FTMap Processing:

- Submit prepared structure to FTMap server (http://ftmap.bu.edu)

- Algorithm places 16 different organic molecular probes on dense grid around protein

- Clusters low-energy probe positions and ranks consensus clusters (CCs)

- Results Analysis:

- Identify primary hot spot (CC1) as consensus cluster with most probe clusters

- Note secondary hot spots (CC2, CC3, etc.) with fewer probe clusters

- Sites with ≥16 probe clusters indicate highly druggable regions

Technical Notes: FTMap successfully identifies hot spots even in the absence of visible binding pockets. The method is particularly valuable for prioritizing PPI targets for FBDD campaigns [5].

Protocol 4: Machine Learning for PPI Prediction and Hot Spot Identification

Purpose: To leverage machine learning algorithms for predicting PPIs and identifying potential hot spot regions.

Materials:

- Curated PPI databases (STRING, BioGRID)

- Protein sequence and structural data

- Machine learning frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch)

Procedure:

- Data Curation:

- Collect known PPIs from public databases

- Generate negative examples (non-interacting pairs) carefully to avoid false negatives

- Address class imbalance through oversampling or weighted loss functions

- Feature Engineering:

- Sequence-based features: amino acid composition, evolutionary conservation, co-evolution signals

- Structure-based features: surface topography, residue propensity, solvent accessibility

- Model Training:

- Implement transformer architectures for sequence-based prediction

- Train on 80% of data, validate on 20% with strict separation to prevent data leakage

- Use 5-fold cross-validation for robust performance assessment

- Hot Spot Prediction:

- Integrate with structural data to map predicted interfaces to 3D structures

- Apply FTMap or similar tools to predicted interfaces

Technical Notes: Sequence-based methods offer advantages when high-quality structures are unavailable. Recent models like PepMLM have successfully designed peptide binders where structure-based methods failed [7].

Diagram 2: Logical relationship from PPI interface to drug candidate via hot spot targeting

Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PPI Hot Spot Analysis and Modulation

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Libraries | MW 150-250 Da, ≤3 H-bond donors/acceptors, ≤3 rotatable bonds | Identify initial chemical starting points against hot spots [8] |

| PLIP (Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler) | Web server or standalone tool, detects 8 interaction types | Analyze interaction patterns in PPIs and small molecule complexes [6] |

| Alanine Scanning Kits | Site-directed mutagenesis kits, expression vectors | Experimental hot spot identification [1] [5] |

| SPR Biosensors | Biacore systems with CMS chips, low molecular weight settings | Detect weak fragment binding (KD 1 μM-10 mM) [8] |

| Crystallography Screens | 96-well sparse matrix screens, fragment soaking solutions | Structural characterization of fragment binding [1] [5] |

| FTMap Server | Web-based or local installation, 16 probe molecules | Computational hot spot mapping [5] |

| PPI-Focused Compound Libraries | Curated collections enriched for PPI inhibitors (e.g., Life Chemicals) | Screening starting points for challenging PPIs [9] |

The systematic identification and characterization of hot spots within PPI interfaces has transformed our approach to targeting these historically "undruggable" systems. Through integrated experimental and computational protocols—including alanine scanning, fragment-based screening, and computational mapping—researchers can now deconstruct complex PPI interfaces into pharmacologically tractable targets. The quantitative frameworks and standardized protocols presented here provide a roadmap for advancing PPI-targeted drug discovery programs.

Future directions in this field will likely see increased integration of machine learning methods for predicting PPI interfaces and hot spots, particularly for targets lacking structural data [10] [7]. Additionally, the emergence of covalent fragment strategies and targeted protein degradation approaches expands the toolbox for addressing challenging PPIs [8]. As these technologies mature, combined with the foundational principles of hot spot-based design, the PPI drugging landscape will continue to evolve from confronting "undruggable" targets to employing systematic, rational design strategies.

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) has emerged as a powerful approach for identifying chemical starting points against challenging biological targets, particularly protein-protein interactions (PPIs) which were long considered "undruggable" [10] [11]. Unlike traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) that searches libraries of drug-like molecules, FBDD utilizes very small chemical fragments (typically ≤ 20 heavy atoms) as building blocks for drug development [12]. This methodology has proven exceptionally valuable in PPIs modulation research, yielding several clinical successes including venetoclax (Bcl-2 inhibitor) and sotorasib (KRAS G12C inhibitor) [12]. The fundamental premise of FBDD lies in the superior efficiency of small fragments at sampling chemical space and identifying productive binding interactions that can be systematically optimized into potent, drug-like compounds [12] [13]. This Application Note details the core principles underpinning FBDD's success against PPIs and provides practical protocols for implementation.

Core Principle 1: Superior Chemical Space Sampling

Fragment libraries achieve dramatically better coverage of chemical space than traditional HTS libraries despite their significantly smaller size. This advantage stems from the exponential relationship between molecular size and the number of possible compounds [12]. A library of 1,000-2,000 fragments can effectively sample a much broader range of molecular architectures than HTS libraries containing millions of larger compounds [12].

Table 1: Chemical Space Coverage Comparison: FBDD vs. HTS

| Parameter | FBDD Approach | HTS Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Library Size | 1,000 - 2,000 compounds [12] | >1,000,000 compounds |

| Molecular Weight | ≤ 300 Da [12] | 200-500 Da [11] |

| Heavy Atom Count | ≤ 20 [12] | Typically >20 |

| Chemical Space Coverage | High with limited compounds [12] | Limited despite large numbers |

| Hit Rate | 0.1 - 3% (higher for druggable targets) [12] | Typically <0.001% |

The mathematical rationale for this superior sampling is straightforward: as molecular size increases, the number of possible molecules grows exponentially [12]. Fragments, with their low heavy atom count, represent the most efficient way to sample diverse molecular architectures. This comprehensive sampling is particularly crucial for PPIs, which often feature discontinuous binding epitopes that may not be effectively targeted by pre-assembled drug-like molecules [10].

Core Principle 2: Binding Efficiency and Atom Economy

Fragments exhibit superior binding efficiency compared to larger molecules, making them more optimal starting points for medicinal chemistry optimization. Because of their small size and simplicity, fragments typically make fewer but higher quality interactions with their protein targets [12]. This "atom economy" means that each heavy atom contributes more significantly to binding energy compared to larger molecules where portions of the molecule may form suboptimal interactions or even clash with the target [12].

Table 2: Binding Properties Comparison Between Fragments and HTS Hits

| Property | Fragment Hits | HTS Hits |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Range (Kd) | μM - mM [12] | nM - low μM [12] |

| Ligand Efficiency (LE) | High | Variable to low |

| Binding Mode | Atom-efficient [12] | May contain unproductive interactions |

| Optimization Potential | High | Limited |

| Molecular Complexity | Low | High |

The high ligand efficiency of fragments is particularly advantageous for targeting PPIs, which typically feature large, flat interaction interfaces (1,500-3,000 Ų) with limited deep pockets [11]. These interfaces contain specific "hot spots" - residues that contribute significantly to binding free energy - which are ideally targeted by efficient fragment binders [10] [11]. By starting with efficient fragments that bind to these hot spots, researchers can build compounds that maintain favorable physicochemical properties while achieving sufficient potency to disrupt the PPI [10].

Core Principle 3: Effective Targeting of PPI Hot Spots

PPI interfaces, while large, typically contain localized regions known as "hot spots" that contribute disproportionately to binding energy [10] [11]. These hot spots are defined as residues where alanine mutation causes a significant increase in binding free energy (ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [11]. Although the total PPI interface may encompass 1,500-3,000 Ų, the combined area of all hot spots is typically only about 600 Ų [11]. This structural characteristic makes PPIs amenable to fragment targeting.

The discontinuous nature of PPI hot spots creates an ideal environment for fragment binding [10]. While traditional drug-like molecules might struggle to make productive interactions across the entire interface, smaller fragments can bind to individual sub-pockets within these hot spot regions [10]. This binding mechanism explains why FBDD has been particularly successful against challenging PPI targets, with fragments exploiting the intrinsic energetic landscape of the interaction interface [10] [14].

Diagram 1: Fragment Binding to PPI Hot Spots

Experimental Protocols for FBDD in PPI Research

Protocol 1: Fragment Library Design and Screening

Objective: Construct a diverse fragment library optimized for PPI targets and identify initial binders using orthogonal biophysical methods.

Materials and Reagents:

- Rule of Three compliant fragments (MW ≤ 300, cLogP ≤ 3, HBD ≤ 3, HBA ≤ 3) [12]

- Optional: PPI-focused fragments with known privileged scaffolds

- Target protein in purified form (>95% purity)

- Biophysical screening buffers

Procedure:

- Library Design (2-4 weeks):

- Select 1,000-2,000 fragments ensuring chemical diversity and favorable physicochemical properties [12]

- Enhance 3D character by including fragments with Fsp3 > 0.4 to improve success against flat PPI interfaces [12]

- Confirm aqueous solubility >200 μM to ensure detectability in biophysical assays [12]

Primary Screening (2-3 weeks):

- Perform initial screening using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

- For SPR: Use high protein immobilization density and multi-cycle kinetics

- For NMR: Monitor chemical shift perturbations or line broadening

- Identify hits showing concentration-dependent response

Hit Validation (1-2 weeks):

- Confirm binding using orthogonal method (e.g., thermal shift assay, X-ray crystallography)

- Determine approximate affinity (typically Kd values in μM-mM range for fragments)

- Assess compound integrity and purity post-assay

Structural Characterization (4-8 weeks):

- Pursue X-ray co-crystal structures of protein-fragment complexes [14]

- Utilize synchrotron sources for weak binders if needed

- Identify binding mode and vector for fragment optimization

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For weakly binding fragments, use higher concentrations while monitoring compound aggregation

- If no hits observed, consider expanding library diversity or screening under different buffer conditions

- For membrane protein targets, incorporate appropriate detergents or nanodiscs

Protocol 2: Computational Fragment Screening and Optimization

Objective: Identify and optimize fragment hits using computational approaches to accelerate PPI inhibitor development.

Materials:

- High-resolution protein structure (X-ray or cryo-EM)

- Fragment library in suitable format for docking

- Molecular dynamics simulation software

- Structure-based drug design platform

Procedure:

- Virtual Screening (1-2 weeks):

- Prepare protein structure, ensuring proper protonation states

- Define binding site based on known hot spot regions [10]

- Perform molecular docking of fragment library

- Rank compounds based on scoring function and interaction analysis

Binding Mode Analysis (1 week):

- Cluster docking poses to identify preferred binding geometries

- Analyze fragment-protein interactions at atomic level

- Prioritize fragments making key interactions with hot spot residues

Advanced Sampling (2-4 weeks):

Fragment Growing/Linking (Ongoing):

- Identify optimal vectors for fragment elaboration using structural information

- Design follow-up compounds using structure-based approaches

- Synthesize and test optimized compounds iteratively

Diagram 2: FBDD Workflow for PPI Inhibitor Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FBDD in PPI Research

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diverse Fragment Library | Primary screening collection | 1,000-2,000 compounds; Rule of Three compliance; high solubility [12] |

| SPR Chip Surfaces | Immobilization of PPI target for binding studies | CMS chips for amine coupling; NTA chips for his-tagged proteins |

| NMR Screening Buffers | Maintain protein stability during NMR screening | Deuterated buffers; reducing agents; protease inhibitors |

| Crystallization Screens | Co-crystallization of protein-fragment complexes | Sparse matrix screens; additive screens; optimized for PPIs |

| GC/NCMC Simulation Software | Computational fragment screening | Enhanced sampling of fragment binding modes [15] |

| Fragment Optimization Kits | Chemical elaboration of confirmed hits | Building blocks with appropriate functional handles |

| (20R)-Ginsenoside Rh1 | (20R)-Ginsenoside Rh1, MF:C36H62O9, MW:638.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hexyl hexanoate | Hexyl hexanoate, CAS:6378-65-0, MF:C12H24O2, MW:200.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Study: Keap1-Nrf2 PPI Inhibition

The development of noncovalent inhibitors for the Keap1-Nrf2 PPI exemplifies the successful application of FBDD principles [14]. Researchers began with a weak fragment hit identified through crystallographic screening against the Keap1 Kelch domain. Despite initial low affinity, the fragment provided a critical starting point that was systematically optimized through structure-based design [14]. A two-step growing strategy guided by multiple X-ray co-crystal structures ultimately yielded compounds with low nanomolar affinities and complete selectivity for Keap1 over homologous Kelch domains [14]. These optimized compounds demonstrated potent activation of Nrf2-controlled gene expression and anti-inflammatory effects in cellular models, highlighting the potential of FBDD to generate high-quality chemical probes against challenging PPI targets [14].

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery represents a paradigm shift in addressing challenging targets like PPIs, overcoming the limitations of traditional HTS through superior chemical space sampling, enhanced binding efficiency, and precise targeting of interaction hot spots. The systematic workflow from fragment screening to lead optimization, supported by robust biophysical and structural methods, enables the development of high-quality chemical tools and drug candidates against targets once considered undruggable. As computational methods like GCNCMC continue to enhance sampling capabilities [15], and machine learning approaches facilitate fragment assembly [13] [16], the application of FBDD in PPI research is poised for continued growth and success.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) represent a highly attractive yet challenging class of therapeutic targets due to their pivotal role in cellular signaling and disease progression [17] [10]. The large, flat, and often featureless interfaces of PPIs, which typically span 1500–3000 Ų, initially rendered them "undruggable" by conventional small molecules designed for traditional enzymatic targets [17] [18]. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome these challenges by starting from small, low molecular weight compounds (fragments) that bind weakly to specific regions of the PPI interface [19] [20]. These fragments, typically ranging from 150-250 Da, exhibit high ligand efficiency and provide starting points for developing potent inhibitors through structure-based design [19] [20].

The synergy between FBDD and PPI modulation stems from FBDD's ability to identify fragments that bind to key "hot-spots"—small regions within the PPI interface that contribute disproportionately to the binding free energy [17] [10]. Through strategic optimization, these weakly binding fragments can be evolved into clinical candidates capable of disrupting therapeutically relevant PPIs, transforming drug discovery for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other conditions [17] [10] [21]. This application note traces the historical development of this synergistic relationship, documents key milestones, and provides detailed protocols for implementing FBDD campaigns against challenging PPI targets.

Historical Development and Key Milestones

The evolution of FBDD as a solution for targeting PPIs represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery methodology. The table below chronicles the key milestones in this developing field.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Milestones in FBDD and PPI Modulation

| Year | Milestone | Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Jencks introduces conceptual foundation for FBDD | Theoretical framework for studying molecular interactions through fragments | [20] |

| 1990s | Development of SAR by NMR by Shuker et al. | First practical implementation of FBDD using NMR to detect fragment binding | [20] |

| 1995 | Alanine scanning mutagenesis identifies PPI hot-spots | Demonstrated that small regions contribute most binding energy in PPI interfaces | [17] [18] |

| 1997 | Discovery of first small-molecule IL-2/IL-2Rα inhibitor (Ro26-4550) | Proof-of-concept that small molecules can modulate PPIs | [18] |

| 2003 | Human Protein Atlas project launched | Provided comprehensive dataset accelerating PPI research | [10] |

| 2005 | Astex-GSK collaboration on Pyramid platform | Early industry validation of FBDD for drug discovery | [22] [23] |

| 2011 | FDA approves vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor) | First FBDD-derived drug approved, targeting kinase domain | [20] |

| 2016 | FDA approves venetoclax (Bcl-2 inhibitor) | First FBDD-derived PPI modulator approved, validating FBDD for PPIs | [10] [20] |

| 2021 | FDA approves sotorasib (KRAS-G12C inhibitor) | Milestone for targeting "undruggable" oncogenic mutants via FBDD | [10] [20] |

| 2021 | Release of AlphaFold and RosettaFold | Revolutionized structural prediction of proteins and PPIs | [10] |

| 2023 | FDA approves capivasertib (AKT inhibitor) | Eighth FBDD-derived drug approval, demonstrating continued productivity | [20] |

| 2025 | Advanced parallel SPR screening on target arrays | High-throughput fragment screening across multiple targets simultaneously | [8] |

The timeline demonstrates a clear progression from conceptual foundations to practical implementation and eventual clinical validation. The period between 2011-2023 marked a particularly productive era with eight FDA-approved drugs originating from FBDD, several of which directly target therapeutically relevant PPIs [20]. The approval of venetoclax in 2016 represented a watershed moment, providing definitive proof that FBDD could yield clinically effective PPI modulators [10] [20]. This success has stimulated increased investment and technological innovation in the field, with the global FBDD market projected to grow from USD 939.29 million in 2025 to USD 2.69 billion by 2033, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.5% [22].

Fundamental Concepts and Mechanisms

The PPI Druggability Challenge and the Hot-Spot Concept

Protein-protein interfaces present unique challenges for conventional drug discovery approaches. Unlike enzymatic active sites with well-defined deep pockets, PPI interfaces tend to be large, flat, and lacking obvious binding pockets for small molecules [17] [18]. This topographic feature initially led to the classification of most PPIs as "undruggable." The discovery of "hot-spots" revolutionized this perspective by revealing that binding energy is not uniformly distributed across the entire interface [17]. Instead, these are specific regions where alanine mutations cause a significant increase in binding free energy (≥2.0 kcal/mol) [17] [10]. Tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine residues occur more frequently in these hot-spots than other amino acids [17]. Although the total PPI interface may span 1500–3000 Ų, the combined area of all hot-spots is typically only about 600 Ų, presenting a more tractable target for small molecule intervention [17].

FBDD as a Strategic Solution for PPI Modulation

Fragment-based drug discovery is uniquely suited to address the challenges of PPI modulation through its bottom-up approach. FBDD begins with screening small molecular fragments (150-250 Da) that bind weakly (millimolar to micromolar affinity) to hot-spot regions [19] [20]. Despite their low affinity, fragments exhibit high ligand efficiency (binding energy per atom), providing optimal starting points for optimization [19]. The small size and simplicity of fragments enable them to access cryptic pockets and bind in ways that larger, more complex drug-like molecules cannot [19]. Compared to high-throughput screening (HTS), FBDD offers several advantages for PPI targets: it covers broader chemical space with fewer compounds (typically 1,000-2,000 fragments versus millions in HTS), achieves higher hit rates, and generates hits with favorable physicochemical properties [17] [20].

Table 2: Comparison of FBDD and HTS for PPI Modulator Discovery

| Parameter | Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) |

|---|---|---|

| Library Size | 1,000-2,000 compounds | >1,000,000 compounds |

| Molecular Weight | 150-250 Da | 350-500 Da |

| Typical Affinity of Initial Hits | Millimolar to micromolar (weak) | Micromolar to nanomolar (strong) |

| Hit Rate | 1-10% (higher) | 0.001-0.1% (lower) |

| Chemical Space Coverage | More efficient with fewer compounds | Less efficient, requires large libraries |

| Screening Methods | Biophysical (X-ray, NMR, SPR) | Biochemical activity-based |

| Suitability for PPIs | Excellent for targeting hot-spots | Limited due to flat interfaces |

| Optimization Complexity | High (requires fragment growing/linking) | Lower (direct optimization of hits) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Core FBDD Workflow for PPI Targets

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for identifying and optimizing PPI modulators using FBDD approaches.

Fragment Library Design and Screening

Objective: To design a diverse fragment library and identify initial binders to the PPI target. Materials and Reagents:

- Purified, stable target protein (>95% purity)

- Fragment library (1,000-2,000 compounds)

- Crystallization screens (if using X-ray)

- NMR buffers (if using NMR)

- Sensor chips (if using SPR)

Procedure:

- Library Design: Curate a fragment library emphasizing chemical diversity, solubility, and synthetic tractability. Ideal fragments should comply with the "rule of 3" (MW <300, cLogP ≤3, HBD ≤3, HBA ≤3) [19] [20].

- Primary Screening: Screen the library against the target protein using orthogonal biophysical methods:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Immobilize target protein on sensor chip. Screen fragments at high concentrations (0.1-1 mM) in single-point measurements. Identify hits showing concentration-dependent binding [8] [20].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Perform protein-observed or ligand-observed NMR experiments. Monitor chemical shift perturbations or signal attenuation to confirm binding [18] [20].

- X-ray Crystallography: Soak fragments into protein crystals or co-crystallize. Collect diffraction data to determine atomic-level binding modes [20].

- Hit Validation: Confirm initial hits using secondary techniques such as ITC (isothermal titration calorimetry) or MST (microscale thermophoresis) to quantify binding affinities and thermodynamic parameters [20].

- Triaging: Prioritize fragments based on ligand efficiency (LE), binding mode, chemical tractability, and lack of assay interference.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If hit rate is too low (<1%), consider expanding chemical diversity or increasing fragment concentration.

- If hit rate is too high (>10%), implement stricter binding criteria or counter-screens against unrelated proteins.

- For insoluble fragments, modify buffer conditions or exclude problematic compounds.

Fragment to Lead Optimization

Objective: To transform validated fragment hits into lead compounds with improved potency and drug-like properties. Materials and Reagents:

- Structure determination equipment (X-ray, NMR)

- Medicinal chemistry tools for synthetic optimization

- Functional assays for PPI inhibition

Procedure:

- Structural Characterization: Determine high-resolution structures of protein-fragment complexes to guide optimization [17] [20].

- Optimization Strategy Selection:

- Fragment Growing: Systematically add functional groups to the core fragment to extend into adjacent sub-pockets. Monitor LE to ensure efficiency is maintained or improved [20].

- Fragment Linking: If two fragments bind to proximal sites, design linkers to connect them into a single molecule with additive binding energy [18] [20].

- Fragment Merging: When overlapping fragments are identified, design hybrid compounds incorporating features of multiple hits [20].

- Iterative Design Cycles: Synthesize analog series based on structural data. Evaluate using biophysical and functional assays. Continue optimization until lead criteria are met (typically IC50 <100 nM for PPI targets).

- Selectivity Profiling: Screen optimized compounds against related proteins to establish selectivity profile.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If potency plateaus, explore alternative vector directions or scaffold hopping.

- If physicochemical properties deteriorate, balance hydrophobicity with polar groups.

- If synthetic complexity increases excessively, evaluate whether the added complexity is justified by potency gains.

Protocol 2: Advanced Targeted Screening Approaches

Parallel SPR Fragment Screening

Objective: To accelerate fragment screening by evaluating binding across multiple targets simultaneously. Materials and Reagents:

- SPR instrument with multi-channel capability

- Array of target proteins and unrelated controls

- Fragment library

Procedure:

- Target Immobilization: Immobilize a panel of related target proteins and negative controls on separate flow cells of an SPR sensor chip [8].

- Parallel Screening: Screen fragments against the entire target array in a single experiment.

- Selectivity Analysis: Identify fragments with desired selectivity profiles based on differential binding across the target panel.

- Affinity Clustering: Group fragments with similar binding patterns across targets to identify common binding motifs [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of FBDD for PPI modulation requires specialized reagents and technologies. The following table details essential components of the experimental toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for FBDD-PPI Workflows

| Category | Specific Reagents/Technologies | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragment Libraries | • Rule of 3 compliant compounds• Covalent fragment libraries• Natural product-derived fragments | Provide starting points for drug discovery with high ligand efficiency and diversity | Prioritize solubility, synthetic tractability, and 3D character [19] [20] |

| Biophysical Screening Technologies | • Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)• Protein-observed NMR• X-ray Crystallography• Thermal Shift Assays | Detect weak fragment binding and provide structural information | SPR offers kinetics; NMR detects subtle interactions; X-ray gives atomic resolution [8] [20] |

| Structural Biology Tools | • Cryo-EM systems• Automated crystal harvesting• High-throughput crystallography | Enable structure determination of protein-fragment complexes | Cryo-EM suitable for large PPI complexes; X-ray for soluble domains [10] |

| Computational Support | • Molecular docking software• Free energy perturbation• Machine learning algorithms | Predict binding modes and optimize fragments in silico | Essential for visualizing hot-spots and guiding fragment linking [10] [20] |

| Protein Production | • Recombinant expression systems• Isotope-labeled proteins (for NMR)• Tag cleavage enzymes | Generate high-quality protein samples for screening | Require stable, pure, functional proteins; isotope labeling for NMR studies [20] |

| Noroxyhydrastinine | Noroxyhydrastinine, CAS:21796-14-5, MF:C10H9NO3, MW:191.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Persicogenin | Persicogenin, CAS:28590-40-1, MF:C17H16O6, MW:316.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Case Studies and Clinical Successes

Case Study 1: Venetoclax (BCL-2 Inhibitor)

Background: The BCL-2/BAX PPI regulates apoptotic signaling in cancer cells, with overexpression of BCL-2 conferring survival advantage in hematological malignancies [17] [20]. Despite being a challenging PPI target with a large interface, researchers identified a key hot-spot region that could be targeted with small molecules.

FBDD Approach: Using a combination of NMR-based screening and structure-based design, researchers identified fragment hits binding to a critical hydrophobic groove on BCL-2 [18] [20]. Through iterative structure-guided optimization, these fragments were developed into navitoclax and subsequently venetoclax, which displayed nanomolar affinity and high selectivity for BCL-2 over related proteins [18] [20].

Clinical Impact: Venetoclax received FDA approval in 2016 for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia, representing the first approved FBDD-derived PPI modulator [10] [20]. This success demonstrated that FBDD could overcome the druggability challenges of PPIs and produce clinically impactful medicines.

Case Study 2: Sotorasib (KRAS G12C Inhibitor)

Background: KRAS mutations drive approximately 25% of non-small cell lung cancers and other solid tumors, but had been considered "undruggable" for decades due to the absence of traditional binding pockets [22] [20].

FBDD Approach: Researchers employed covalent fragment screening to identify compounds that could bind adjacent to the G12C mutation [20]. Structure-based optimization yielded sotorasib, which forms a covalent bond with cysteine 12 while exploiting a newly created pocket that emerges upon binding [20].

Clinical Impact: Sotorasib's 2021 FDA approval marked a breakthrough in targeting previously intractable oncogenic drivers [10] [20]. This case highlights how FBDD can identify cryptic binding sites that enable targeting of challenging oncoproteins.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The synergy between FBDD and PPI modulation continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being increasingly integrated into FBDD workflows to predict binding affinities, optimize fragments, and design novel chemical entities [10] [19]. The 2021 release of AlphaFold and RosettaFold has revolutionized structural prediction of proteins and PPIs, providing models for targets that lack experimental structures [10]. Covalent FBDD approaches are gaining traction for addressing challenging targets by providing enhanced binding energy through targeted covalent linkages [8]. Additionally, the application of FBDD to targeted protein degradation represents an exciting frontier where fragments can be used to design molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target proteins for degradation [8].

The ongoing technological innovations in screening methods, such as parallel SPR detection on large target arrays, are making fragment screening more efficient and informative [8]. These advances, combined with the growing understanding of PPI hot-spots and allosteric regulation, suggest that FBDD will continue to play a pivotal role in expanding the druggable proteome and delivering new therapeutics for challenging disease targets.

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) has emerged as a powerful approach for identifying chemical starting points in drug development, particularly for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions (PPIs) [10]. Unlike high-throughput screening (HTS), which tests hundreds of thousands of drug-like compounds, FBDD utilizes small, low molecular weight fragments that provide more efficient coverage of chemical space [24]. These fragments typically bind weakly (in the μM–mM range) but form high-quality interactions with their protein targets [25]. The FBDD workflow involves identifying these fragment hits, then progressively optimizing them into potent lead compounds through structure-guided design [26]. Three fundamental concepts govern this process: the Rule of Three for fragment selection, ligand efficiency for hit qualification, and strategic fragment library design. These principles are especially crucial for modulating PPIs, where interaction interfaces are often flat and extensive, presenting unique challenges for small molecule intervention [25] [10].

The Rule of Three in Fragment Library Design

The Rule of Three (RO3) is a set of physicochemical guidelines developed specifically for selecting compounds for fragment libraries. It is derived from, and more stringent than, Lipinski's Rule of Five, which predicts oral bioavailability for drug-like molecules [26]. The RO3 criteria are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: The Rule of Three (RO3) Criteria for Fragment Selection

| Physicochemical Property | Rule of Three (RO3) Threshold | Comparative Rule of Five (for Drug-like Compounds) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | ≤ 300 Da | ≤ 500 Da |

| clogP | ≤ 3.0 | ≤ 5.0 |

| Number of Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | ≤ 3 | ≤ 5 |

| Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | ≤ 3 | ≤ 10 |

| Number of Rotatable Bonds (NRot) | ≤ 3 | Not Specified |

| Polar Surface Area (PSA) | ≤ 60 Ų | Not Specified |

The underlying principle of the RO3 is that fragments should be small and simple. This ensures that any initial, weak binding is efficient and provides ample "chemical space" for optimization through fragment growing, linking, or merging [24] [26]. Adherence to the RO3 increases the likelihood that a fragment hit can be developed into a lead compound that ultimately complies with the Rule of Five, ensuring favorable drug-like properties and oral bioavailability [26].

In practice, these rules are often applied with a degree of flexibility, especially for specific target classes like PPIs. For instance, one research group assembled a PPI-focused fragment library using modified thresholds: MW ≤ 330 Da, clogP ≤ 3.4, and PSA ≤ 70 Ų [25]. This highlights that the RO3 serves as a guiding principle rather than a rigid filter, allowing for the inclusion of attractive, synthetically accessible, or target-relevant chemotypes that might otherwise be excluded.

Ligand Efficiency in Hit Selection and Optimization

Ligand Efficiency is a critical metric for evaluating the quality of a fragment hit. It normalizes the binding affinity of a molecule against its size, providing a measure of how much binding energy is contributed per atom [27] [24]. The most common definition of Ligand Efficiency is:

LE = -ΔG / N ≈ (-RT ln Kd) / N

Where:

- ΔG is the binding free energy (typically in kcal/mol)

- Kd is the dissociation constant

- N is the number of non-hydrogen atoms (heavy atoms)

- R is the gas constant and T is the temperature [24]

For fragments, an LE of ≥ 0.3 kcal/mol per heavy atom is generally considered a threshold for a high-quality hit [26]. This indicates that the fragment makes efficient use of its limited atoms to interact with the target. LE is indispensable for ranking fragments, as a smaller fragment with weaker absolute affinity (e.g., Kd = 1 mM) might have a higher LE and thus represent a better starting point than a larger fragment with stronger affinity (e.g., Kd = 10 μM) but a lower LE [27] [24].

The concept of LE extends throughout the optimization process. As atoms are added during fragment elaboration, the goal is to maintain or only slightly decrease the LE, ensuring that the increase in potency is not achieved at the expense of binding efficiency. This helps prevent the development of oversized, lipophilic molecules with poor physicochemical properties [27].

Designing a Fragment Library for PPI Modulation

The construction of a high-quality fragment library is a foundational step in any FBDD campaign. For PPI targets, which often feature shallow, hydrophobic interaction surfaces, careful library design is even more critical [25] [10]. The process involves multiple stages of filtering and curation, as outlined in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for constructing a PPI-focused fragment library, adapted from the protocol established by Taros [25].

Key Considerations for a PPI-Focused Library

- Chemical Diversity and 3D Character: The library should maximize structural diversity to efficiently sample chemical space. For PPI interfaces, which are often less defined, fragments with a pronounced three-dimensional (sp3-rich) character are highly valuable as they can better explore extended pockets [25].

- Drug-like and Synthetically Tractable: Fragments should contain exit points (vectors) for synthetic elaboration. Reactive or undesirable functional groups (e.g., alkyl halides, Michael acceptors, acyl chlorides) must be removed, while polycyclic and heterocyclic compounds are preferred [25].

- Natural Products as Inspiration: Natural products are excellent sources of complex, sp3-rich fragments. Deconstructing natural products using algorithms like RECAP can generate unique Natural Product-Derived Fragments that access novel chemical space not covered by synthetic libraries alone [28] [29].

- Target Focus: While general diversity is key, creating a library tailored to the specific challenges of PPIs—such as by including fragments known to interact with aromatic hot spots common in PPI interfaces—can enhance success rates [10].

Table 2: Representative Sources for Fragment Libraries in FBDD Research

| Library Source / Type | Description | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Vendors | Commercially available pre-selected fragments. | Enamine (12,000 fragments), ChemDiv (74,000), Maybridge (30,000) [29]. |

| Synthetic / Academic | Fragments based on novel heterocyclic scaffolds. | CRAFT library (1,214 fragments) [29]. |

| Natural Product-Derived | Fragments generated by computational fragmentation of Natural Product (NP) databases. | Non-extensive fragmentation of COCONUT and LANaPDB databases yields diverse, developable fragments [28] [29]. |

| Specialized Software Libraries | Computational toolkits for in silico fragment assembly and design. | BuildAMol (Python toolkit), SeeSAR's FastGrow (medchem set: 120k fragments) [30] [31]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Representative Fragment Screening Campaign for 14-3-3σ

The following protocol details a real-world screening campaign targeting the 14-3-3σ PPI, illustrating the application of the concepts discussed above [25].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for a Fragment Screening Campaign

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein | 14-3-3σ and 14-3-3σΔC17 (C-terminal truncated) | N-terminally His6-tagged, expressed in E. coli [25]. |

| Fragment Library | A customized, PPI-focused library complying with the Rule of Three. | ~800 fragments pre-dissolved in DMSO and combined into cocktails of 5 fragments each [25]. |

| Growth Media | For isotopic labeling of protein for NMR. | Deuterated M9 minimal medium supplemented with ²H/¹²C glucose and ¹âµNHâ‚„Cl [25]. |

| NMR Buffers | For maintaining protein stability and consistency during NMR experiments. | Standard phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, with Dâ‚‚O. |

| Biophysical Assay Reagents | For orthogonal binding confirmation. | Sypro Orange dye for Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) [25]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Protein Production and Purification

- Express the 14-3-3σ protein in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. For NMR studies, use a C-terminal truncated variant (14-3-3σΔC) to improve spectral quality.

- For protein observed NMR, produce uniformly ¹âµN-labeled protein by growing cells in M9 minimal medium containing ¹âµN-ammonium chloride as the sole nitrogen source.

- Purify the protein using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) leveraging the His6-tag, followed by size-exclusion chromatography for polishing and buffer exchange.

Step 2: Primary Screening via Ligand-Observed NMR

- Prepare fragment cocktails in NMR tubes, each containing 5 fragments at a final concentration of 100-200 µM per fragment.

- Acquire 1D ¹H NMR spectra for each cocktail.

- Identify potential binders by detecting changes in the NMR parameters of the fragment signals, such as line broadening (T2 relaxation) or changes in chemical shift, which indicate binding to the protein target.

Step 3: Hit Deconvolution and Validation

- Re-test each fragment from a hit cocktail individually in a 1D ¹H NMR experiment to identify the specific binder(s).

- Confirm binding using an orthogonal, protein-based method. In this case, use:

- 2D ¹H-¹âµN HSQC NMR: Titrate the confirmed fragment into a sample of ¹âµN-labeled 14-3-3σ. Monitor the chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of the protein backbone amide signals. This not only confirms binding but also provides information on the binding site location.

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF): Measure the shift in the protein's thermal melting curve (ΔTm) in the presence of the fragment. A stabilizing ΔTm is indicative of binding.

Step 4: Hit Qualification and Analysis

- For validated hits, determine the dissociation constant (Kd) by performing NMR or DSF titrations and fitting the data to a binding model.

- Calculate the Ligand Efficiency (LE) for each hit using the formula in Section 3 and the determined Kd.

- Prioritize fragments that bind with LE ≥ 0.3 kcal/mol per heavy atom for further structural characterization and optimization.

Diagram 2: A multi-step screening cascade for robust fragment hit identification, using orthogonal biophysical methods [25] [26].

The synergistic application of the Rule of Three, Ligand Efficiency, and principled Fragment Library Design forms the bedrock of a successful FBDD campaign, especially for the challenging yet therapeutically promising arena of PPI modulation. These concepts guide researchers from the initial selection of chemically tractable starting points through the critical evaluation of binding events, ensuring that fragment hits are not merely weak binders, but efficient and developable leads. As demonstrated in the protocol for 14-3-3σ, a rigorous, multi-technique screening cascade is essential for reliably identifying and validating these starting points. By adhering to these core principles, FBDD continues to provide a robust pathway for transforming small, weak fragments into potent, selective drug candidates, with several such compounds, like Vemurafenib and Venetoclax, already achieving clinical success and many more in development [24] [32] [10].

The FBDD Toolbox: An Integrated Workflow from Fragment Hit to PPI Lead

Within the framework of fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) for modulating protein-protein interactions (PPIs), the design of the fragment library is a paramount first step that critically influences the entire campaign's success. PPIs are fundamental to cellular signaling and present attractive yet challenging therapeutic targets due to their often extensive, flat, and featureless interfaces [10]. Fragment-based approaches are particularly well-suited for tackling these "undruggable" targets. Unlike traditional high-throughput screening (HTS) that employs drug-like molecules, FBDD utilizes small, low molecular weight chemical fragments (typically <300 Da) [12] [33]. Their smaller size enables more efficient sampling of chemical space, allows access to cryptic binding pockets, and results in higher ligand efficiency, making them ideal starting points for targeting PPI hot spots [10] [12] [34]. A meticulously designed library is the cornerstone of this strategy, as it maximizes the chances of identifying fragments that can be evolved into potent, drug-like PPI modulators.

Core Principles of Fragment Library Design

The design of a fragment library for PPI modulation extends beyond merely collecting small molecules. It requires a deliberate strategy to ensure comprehensive coverage of chemical and functional space, guided by both empirical rules and the specific challenges posed by PPI interfaces.

Defining the Chemical Space: The Rule of Three and Beyond

The "Rule of Three" (Ro3) has become a standard guideline for defining fragment-like properties [12] [34]. It serves as a useful filter to ensure fragments possess favorable physicochemical characteristics.

- Ro3 Criteria: Molecular weight <300 Da, calculated logarithm of the partition/distribution coefficient (cLogP) ≤ 3, hydrogen bond donors (HBD) ≤ 3, hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) ≤ 3, and rotatable bonds ≤ 3 [12] [33]. Adherence to these rules promotes good aqueous solubility—a critical factor for the sensitive biophysical assays used in screening—and chemical tractability for subsequent optimization [33].

- Moving Beyond the Ro3: While a valuable starting point, the Ro3 is not a strict set of rules. Successful fragment hits, particularly for challenging PPIs, often judiciously violate one or more criteria, most commonly by having a higher HBA count [12]. The ultimate goal is to select fragments that are "social"—possessing synthetic handles or "growth vectors" for straightforward chemical elaboration—and to avoid "unsocial" fragments or those containing toxicophores and pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) [35].

Strategic Selection: Structural vs. Functional Diversity

A primary objective in library design is to maximize diversity to efficiently explore a vast array of potential protein interactions.

- Structural Diversity: The conventional approach emphasizes structural and shape diversity, often achieved using molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MACCS) and algorithms to select a set of maximally dissimilar compounds [34] [35]. This ensures the library encompasses a wide variety of scaffolds and geometries.

- Functional Diversity: An emerging, powerful paradigm shifts the focus from structure to function. This strategy selects fragments based on their propensity to form diverse types of interactions with protein targets (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) [35]. Research demonstrates that structurally diverse fragments can be functionally redundant, making the same interactions, while structurally dissimilar fragments can be functionally diverse [35]. For PPI targets, prioritizing functional diversity can significantly increase the amount of novel interaction information recovered from a screen compared to a similarly sized structurally diverse library [35].

Table 1: Key Properties and Considerations for Fragment Library Design

| Property / Consideration | Typical Range / Guideline | Rationale and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ≤ 300 Da | Maintains small size for efficient chemical space sampling and high ligand efficiency [12] [34]. |

| Heavy Atom Count | < 20 | Complements molecular weight as a size metric [35]. |

| cLogP | ≤ 3 | Ensures sufficient aqueous solubility for biophysical assays [12]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors | ≤ 3 each | Prevents excessive polarity while allowing for key interactions [12]. Often violated in successful hits [12]. |

| Rotatable Bonds | ≤ 3 | Limits flexibility, favoring binding entropy [12]. |

| Synthetic Tractability | Presence of "growth vectors" | Essential for efficient fragment-to-lead optimization; "social fragments" are preferred [35] [33]. |

| 3D Character / Fsp3 | Higher value preferred | Moves beyond flat, aromatic scaffolds; can improve solubility and access novel binding modes [12]. |

| Functional Diversity | Prioritize over mere structural diversity | Increases novel interaction information for the target, especially critical for PPI interfaces [35]. |

Quantitative Metrics and Library Size Optimization

Determining the optimal size for a fragment library is a critical decision, balancing diversity with practical screening costs. Quantitative metrics reveal that while library size matters, there is a point of diminishing returns.

- Size-Diversity Relationship: Studies on commercially available fragments show that structural diversity, measured by metrics like "true diversity" (which accounts for the number and abundance of unique structural fingerprints), increases with library size but only up to a point. The marginal gain in diversity per additional fragment decreases as the library grows [34].

- Optimal Size and Coverage Efficiency: Quantitative analysis indicates that a library of approximately 2,000 fragments can capture the same level of "true diversity" as the entire set of over 227,000 commercially available fragments [34]. Furthermore, an optimally diverse, diversity-based selection of about 1,715 fragments (0.75% of the total) can achieve 5% of the total structural richness (unique fingerprints), and ~4,100 fragments (1.8%) can achieve 10% coverage, demonstrating high efficiency [34]. Strikingly, true diversity for diversity-based selections peaks at around 18,000 fragments and then begins to decline, suggesting an upper limit for beneficial expansion [34]. Most successful FBDD campaigns and industrial libraries typically contain between 1,000 and 2,000 compounds [12] [34].

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships Between Fragment Library Size and Diversity

| Library Size (Number of Fragments) | Proportion of Total Commercial Fragments | Quantitative Diversity Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| ~1,715 | 0.75% | Achieves 5% of total structural richness (coverage of unique fingerprints) [34]. |

| ~2,000 | ~0.9% | Attains the same level of "true diversity" as the entire set of >227,000 fragments [34]. A typical size for many successful FBDD libraries [12] [34]. |

| ~4,100 | 1.80% | Achieves 10% of total structural richness [34]. |

| ~18,000 | 7.76% | Represents the point of maximum "true diversity" in diversity-based selections [34]. |

Experimental Protocols for Library Screening and Validation

The weak affinities (μM to mM) of fragment hits necessitate highly sensitive, label-free biophysical methods for detection and validation. A robust workflow employs orthogonal techniques to confirm binding.

Protocol 4.1: Primary Screening via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Purpose: To identify initial fragment binders in a real-time, label-free manner and obtain kinetic data [33].

- Target Immobilization: Immobilize the purified, recombinant target protein on a CMS sensor chip using standard amine-coupling chemistry to achieve a response of ~5-10 kRU.

- Fragment Screening: Prepare fragment library as 1 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO. Dilute fragments in running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP) for a final concentration of 50-100 μM and ≤1% DMSO.

- Data Collection: Inject fragments over the target and reference surfaces for a 60-second association phase, followed by a 120-second dissociation phase, at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. Use a multi-cycle or single-cycle kinetics method.

- Hit Identification: Analyze sensorgrams using evaluation software (e.g., Biacore Insight Software). A positive hit is defined by a significant, dose-dependent binding response and reproducible binding profile. Hits are typically prioritized for further study based on binding level and kinetics.

Protocol 4.2: Orthogonal Validation and Affinity Measurement

Purpose: To confirm primary hits and quantify binding affinity using an orthogonal technique [33].

- Hit Validation via MicroScale Thermophoresis (MST):

- Label the target protein using a dedicated RED-NHS 2nd generation dye kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Prepare a 16-step serial dilution of the fragment hit in assay buffer, keeping the fluorescently labeled protein concentration constant.

- Load samples into standard capillaries and measure using the Monolith NT.Automated system.

- Analyze the data from the capillary scan to determine the dissociation constant (K_D) from the dose-response curve.

- Structural Validation via X-ray Crystallography:

- Co-crystallize the target protein with the validated fragment hit or soak the fragment into pre-grown crystals.

- Collect X-ray diffraction data and solve the structure by molecular replacement.

- Identify and analyze the fragment's binding mode, focusing on specific interactions (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts) and the location of unoccupied "hot spots" for future growth [10] [33].

Diagram 1: FBDD Workflow for PPI Modulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

The following table details key reagents, technologies, and computational tools essential for implementing a successful FBDD campaign against PPI targets.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for FBDD

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application in FBDD for PPIs |

|---|---|---|

| Rule of Three Filtered Library | A collection of 1,000-2,000 small molecules adhering to Ro3 principles. | The core asset for screening; provides a diverse set of starting points for identifying PPI binders [34] [33]. |

| SPR Instrumentation (e.g., Biacore) | Label-free technology for real-time kinetic analysis of biomolecular interactions. | Primary screening and hit validation; provides kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity (K_D) for weak fragment binding [33]. |

| X-ray Crystallography System | High-resolution structural biology technique for determining 3D atomic structures. | Gold standard for elucidating the binding mode of fragments at PPI interfaces, revealing key interactions and "hot spots" [10] [33]. |

| Covalent Fragment Library | A subset of fragments containing weak electrophiles (e.g., acrylamides) designed to form reversible covalent bonds with nucleophilic residues (e.g., Cysteine) in the target. | Unlocks difficult-to-drug targets by providing an additional anchoring energy boost, crucial for targeting shallow PPI interfaces [8]. |

| Computational Chemistry Suite | Software for molecular docking, dynamics (MD), and free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations. | Used for virtual screening, predicting binding poses, understanding protein dynamics, and prioritizing fragments for synthesis during optimization [10] [33]. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction Fingerprints (IFPs) | Computational descriptors that encode the patterns of interactions between a ligand and a protein binding site. | Critical for analyzing functional diversity of a fragment library and moving beyond simple structural similarity [35]. |

| 4-Ethylbenzaldehyde | 4-Ethylbenzaldehyde, CAS:4748-78-1, MF:C9H10O, MW:134.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nb-Feruloyltryptamine | Nb-Feruloyltryptamine, CAS:53905-13-8, MF:C20H20N2O3, MW:336.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Library Design Strategy Comparison.

Concluding Remarks

The strategic design of a fragment library is a decisive factor in the success of FBDD campaigns aimed at modulating therapeutically relevant PPIs. Moving beyond simple adherence to the Rule of Three and a sole focus on structural diversity, the most promising approaches now emphasize functional diversity to maximize the recovery of novel interaction information from each screen [35]. Quantitative studies support the use of optimized libraries in the 1,000 to 2,000 fragment range to efficiently cover chemical space without incurring unnecessary redundancy [34]. When combined with a robust, orthogonal workflow of sensitive biophysical screening and high-resolution structural elucidation, a thoughtfully designed fragment library provides a powerful and systematic pipeline for generating innovative chemical leads against targets once deemed "undruggable."

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) has emerged as a powerful alternative to high-throughput screening (HTS), particularly for challenging targets like Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs). PPIs are fundamental to cellular signaling but have historically been considered "undruggable" due to their extensive, flat, and often featureless interfaces [36]. FBDD addresses this challenge by using small, low molecular weight chemical fragments (typically 150-300 Da) that efficiently probe protein surfaces and are subsequently optimized into potent inhibitors [37] [38]. These fragments, while binding weakly, serve as efficient starting points with high ligand efficiency, meaning most atoms participate in target interaction [37] [39].

The identification of these weak binders (with affinities in the µM to mM range) necessitates highly sensitive biophysical methods [39] [40]. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), X-ray Crystallography, and Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) form the cornerstone of successful FBDD campaigns. These techniques enable researchers to detect and validate fragment binding, determine binding modes, and guide the optimization of fragments into lead compounds, making them indispensable for modern PPI drug discovery [36] [41].

Technology Application Notes

The following section provides a detailed comparison and protocol for the key biophysical techniques used in fragment screening for PPI targets.

Comparative Analysis of Biophysical Screening Technologies

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Major Biophysical Screening Technologies in FBDD

| Technology | Affinity Range | Throughput | Sample Consumption | Key Information Provided | Primary Application in FBDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR | µM - mM [39] | Medium-High (500-2000 fragments in days) [39] | Low (25-100 µg per campaign) [39] | Binding confirmation, kinetics (kâ‚, kd), affinity (K_D), thermodynamics [39] | Primary screening and hit validation [39] |

| NMR | µM - mM [40] | Medium | Medium-High | Binding confirmation, binding site (epitope), stoichiometry [40] | Primary screening and hit validation [40] |

| X-ray Crystallography | µM - mM [42] [43] | Low-Medium | High | Atomic-resolution 3D structure of protein-fragment complex [42] | Hit validation and structure-based optimization [42] [40] |

| MST | nM - mM | Low-Medium | Very Low (µL volumes) | Binding affinity (K_D), changes in hydration shell [37] [42] | Orthogonal validation and affinity determination [37] |

Table 2: Advantages and Challenges of Biophysical Screening Technologies

| Technology | Key Advantages | Major Challenges / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SPR | Label-free, real-time kinetics, low protein consumption, high throughput capable [39] | Nonspecific binding, mass transport limitations, requires immobilization [39] |

| NMR | Can detect very weak binders, provides epitope mapping, studies proteins in solution [40] | High instrument cost, requires isotopic labeling for protein-detected methods, lower throughput [40] |

| X-ray Crystallography | Gold standard; provides detailed binding mode and protein conformational changes [42] [43] | Requires high-resolution, robust crystals; high protein consumption; time-consuming [42] [43] |

| MST | Extremely low sample consumption, label-free, works in complex biological solutions [37] [42] | Signal can be influenced by buffer composition and fluorescence properties of the sample [42] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fragment Screening using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Application Note: SPR is highly effective for primary fragment screening due to its label-free nature, real-time kinetic profiling, and medium-to-high throughput capabilities. It is particularly valuable for detecting weak, transient interactions common in initial PPI fragment hits [39].

Materials:

- Instrument: Biacore T200 or equivalent SPR system [39].

- Sensor Chip: CM5 series S or equivalent, suitable for amine coupling [39].

- Running Buffer: HBS-EP+ (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% v/v Surfactant P20), pH 7.4.

- Regeneration Solution: 10-50 mM NaOH or defined based on target stability.

- Fragment Library: 500-2000 compounds, dissolved in 100% DMSO [39] [38].

- Target Protein: Highly purified, preferably >95% homogeneity.

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize the target protein on the sensor chip surface via standard amine coupling chemistry to achieve a density of 5-10 kDa per Rmax response unit (RU). A reference surface (e.g., immobilized inactive mutant or BSA) must be prepared for signal subtraction [39].

- Assay Optimization: Determine optimal fragment screening concentration (typically 50-200 µM) and contact/dissociation times. Perform solvent correction calibration to account for DMSO effects [39].

- Primary Screening: Inject fragments singly or in small mixtures (≤5 fragments) over target and reference surfaces at a flow rate of 30 µL/min. Use multi-cycle or single-cycle kinetics methods.

- Hit Identification: Analyze sensorgrams to identify hits based on specific binding responses (>50% of theoretical Rmax for fragments is a common threshold) and sensogram shapes consistent with binding [37].

- Affinity & Kinetics: For confirmed hits, perform a dose-response series (e.g., 5 concentrations in a 2- or 3-fold dilution series) to determine equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), and association (kâ‚) and dissociation (kd) rate constants [37] [39].

Protocol: Fragment Screening using X-ray Crystallography

Application Note: X-ray crystallography provides the atomic-level structural information critical for rational fragment optimization, especially for flat PPI interfaces. It can detect binders with a wide range of affinities and is often used as a secondary screen to validate hits from other methods [42] [43].

Materials:

- Protein Crystals: Reproducible crystal system diffracting to at least 2.5 Ã… resolution, tolerant of DMSO (preferably up to 10-30%) [42].

- Fragment Library: A curated, highly soluble library (e.g., 400-1000 fragments) [42].

- Soaking Plates: 96-well plates compatible with acoustic dispensing.

- Liquid Handling: Echo acoustic dispenser for precise, non-destructive fragment delivery [42] [43].

- X-ray Source: In-house generator or synchrotron beamline (e.g., Diamond Light Source I04-1) [43].

Procedure:

- Crystal Soaking: Dispense individual fragments dissolved in DMSO (typically 100-500 mM stock) directly into crystal drops using an acoustic dispenser to achieve a final concentration of 5-50 mM. Soak crystals for 2 hours to overnight [42].

- Cryo-Cooling: After soaking, harvest crystals and cryo-cool them in liquid nitrogen for data collection.

- Data Collection: Collect X-ray diffraction data for each fragment-soaked crystal. Modern facilities can automate this, collecting hundreds of datasets [43].

- Data Processing: Process diffraction data automatically using pipelines like DIALS and Xia2 [43].

- Density Analysis: Use the PanDDA (Pan-Dataset Density Analysis) method to identify electron density for weakly bound, partial-occupancy fragments that may be obscured in conventional maps [42] [43].

- Model Building & Refinement: Build and refine atomic models of the protein-fragment complex to confirm the binding pose and identify key interactions.

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: A generalized FBDD screening workflow. The process begins with target and library preparation, proceeds through primary screening and hit validation, and culminates in an iterative cycle of structural analysis and chemical optimization [38] [40].

Figure 2: Detailed workflow for a crystallographic fragment screening campaign. The key step of PanDDA analysis enables the detection of fragments bound with low occupancy, which are common in initial screens [42] [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biophysical Fragment Screening

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Library | A collection of 500-2000 low molecular weight compounds for screening. | Curated according to the "Rule of 3" (MW <300, HBD ≤3, HBA ≤3, cLogP ≤3), high solubility (>1 mM), and chemical diversity [37] [40]. |

| Stabilized GPCRs (StaRs) | Engineered GPCR targets with enhanced thermostability for biophysical studies. | Crucial for enabling SPR and other screens for challenging membrane protein targets like GPCRs [39]. |

| Biacore T200 / Sierra MASS-1 | Modern SPR instruments with high sensitivity. | Capable of detecting binding of fragments as small as 50 Da, with sub-1 RU noise levels [39]. |

| Sensor Chips (CM5, NTA) | Solid supports for immobilizing target proteins in SPR. | Choice of chip and immobilization chemistry (amine, His-capture) depends on target properties [39]. |

| Echo Acoustic Dispenser | Non-contact liquid handler for transferring fragment solutions. | Precisely delivers nanoliter volumes of fragments into crystal drops without damaging crystals [42] [43]. |

| PanDDA Software | Computational algorithm for analyzing crystallographic data. | Identifies and models weak, partial-occupancy fragment binding events from large screening datasets [42] [43]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Protein | Protein enriched with 15N and/or 13C for NMR spectroscopy. | Required for protein-observed NMR methods (e.g., 2D 1H-15N HSQC) to detect binding and map the interaction site [40]. |

| Scopolamine hydrochloride | Scopolamine hydrochloride, CAS:55-16-3, MF:C17H22ClNO4, MW:339.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Acetoxyflavone | 3-Acetoxyflavone|High-Purity Research Compound | 3-Acetoxyflavone is a bioactive flavone derivative for anticancer research. It shows potent antiproliferative activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) represent a highly promising yet challenging class of therapeutic targets in modern drug discovery. The modulation of PPIs holds particular relevance for numerous human pathologies, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and viral infections [10] [44]. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) has emerged as a powerful strategy for targeting PPIs, as small, low molecular weight fragments can access the discontinuous and often flat binding interfaces that characterize these interactions [10] [45]. The success of FBDD campaigns relies fundamentally on high-resolution structural techniques to elucidate the precise binding modes of weak-affinity fragments. X-ray crystallography (XRC) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) serve as cornerstone technologies in this endeavor, providing the atomic-level detail necessary to guide the rational optimization of fragments into potent lead compounds [46] [47]. This Application Note details standardized protocols for employing XRC and cryo-EM to map fragment binding modes within the context of PPI modulation research.

Comparative Analysis of Structural Techniques

The selection of an appropriate structural biology technique depends on the properties of the target protein and the specific stage of the FBDD pipeline. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of XRC and cryo-EM for fragment screening.

Table 1: Comparison of XRC and Cryo-EM in Fragment-Based PPI Modulator Discovery

| Parameter | X-Ray Crystallography (XRC) | Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Resolution Range | 1.5 - 3.0 Ã… [47] | 2.0 - 5.0 Ã… (SPA/CryoSTAC) [47] |

| Sample Requirement | Highly homogeneous, crystallizable protein [46] | Modest homogeneity, tolerance to some heterogeneity [47] |

| Sample State | Static crystal lattice | Vitrified, near-native state |

| Throughput | Medium to High [48] | Lower (increasing) |

| Protein Consumption | Medium to High [48] | Low [47] |

| Key Strength in FBDD | Detects very weak binders; unambiguous electron density for small fragments [15] | Studies dynamic complexes and membrane proteins difficult to crystallize [47] |