High-Throughput Screening for Protein-Small Molecule Interactions: Strategies, Technologies, and Validation

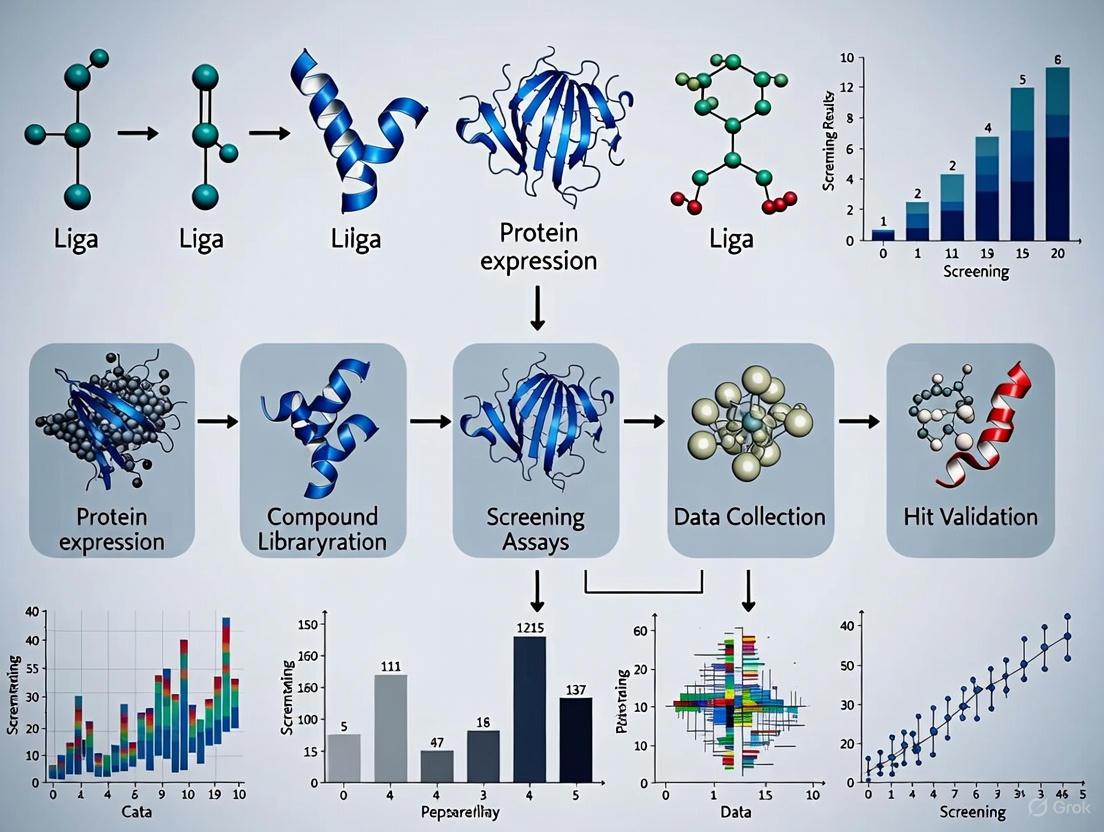

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies for identifying protein-small molecule interactors, crucial for chemical probe and drug discovery.

High-Throughput Screening for Protein-Small Molecule Interactions: Strategies, Technologies, and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies for identifying protein-small molecule interactors, crucial for chemical probe and drug discovery. It covers foundational principles, diverse screening strategies—including target-based biochemical assays and phenotypic cellular screens—and emerging technologies that enhance throughput and reliability. The content details rigorous statistical approaches for hit selection, addresses common challenges like false positives, and outlines essential validation techniques to confirm binding and biological relevance. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current best practices and innovative trends shaping the field.

The Foundation of High-Throughput Screening: Principles and Evolving Landscapes

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a foundational methodology in modern biological research and drug discovery, enabling the rapid experimental testing of thousands to millions of chemical or biological compounds for a specific biological activity [1]. This approach has revolutionized how researchers identify potential drug candidates, molecular probes, and therapeutic targets by allowing massive parallel processing that would be impossible with traditional one-at-a-time methods. The core principle of HTS involves automating assays to quickly conduct vast numbers of tests, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery while reducing costs per sample [2].

The applications of HTS span across both industrial pharmaceutical development and academic basic research. In industrial settings, HTS is indispensable for early-stage drug discovery, allowing pharmaceutical companies to efficiently screen extensive compound libraries against therapeutic targets [3]. In academia, HTS facilitates probe development for pathway analysis and target validation, providing crucial tools for understanding fundamental biological processes and disease mechanisms [4]. The technology has evolved significantly from its origins, with current platforms incorporating advanced automation, miniaturization, and sophisticated data analytics to enhance sensitivity, reliability, and throughput [1].

HTS Market Landscape and Technological Evolution

The HTS market demonstrates robust growth driven by increasing demands for efficient drug discovery processes and technological advancements. Current market valuations are projected to rise from USD 32.0 billion in 2025 to USD 82.9 billion by 2035, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.0% [3]. This expansion reflects the critical role HTS plays across pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and academic research sectors.

Market Segmentation and Dominant Technologies

Table 1: High-Throughput Screening Market Segmentation (2025)

| Segment Category | Leading Segment | Market Share (%) | Key Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Cell-Based Assays | 39.4% | Physiologically relevant data, predictive accuracy in early drug discovery [3] |

| Application | Primary Screening | 42.7% | Essential role in identifying active compounds from large chemical libraries [3] |

| Products & Services | Reagents and Kits | 36.5% | Need for reliable, high-quality consumables ensuring reproducibility [3] |

| End User | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Firms | Not Specified | Rising R&D investment and need for faster validation cycles [3] |

Emerging Technological Trends

The HTS landscape is witnessing several transformative trends that are reshaping its capabilities and applications. Cell-based assays continue to dominate the technology segment due to their ability to provide physiologically relevant data within living systems, offering more predictive accuracy for in vivo responses compared to biochemical assays [3]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is revolutionizing data analysis capabilities, enabling more efficient processing of complex biological data and improving hit identification accuracy [1]. There is also a notable shift toward ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) technologies, which are anticipated to grow at a CAGR of 12% through 2035, driven by their unprecedented ability to screen millions of compounds rapidly and thoroughly explore chemical space [3].

The adoption of miniaturized assay formats, advanced robotic liquid handling systems, and lab automation tools continues to enhance throughput and cost-effectiveness [3]. These technological advancements are particularly crucial for addressing the increasing complexity of drug pipelines and the need for faster validation cycles in both industrial and academic settings. Furthermore, the growing focus on personalized medicine and targeted therapies is creating new opportunities for HTS applications in genomics, proteomics, and chemical biology [1].

Core HTS Technologies for Protein-Small Molecule Interaction Studies

Understanding protein-small molecule interactions is fundamental to drug discovery and probe development, as these interactions modulate protein activity and impact cellular processes and disease pathways [4]. Several core technologies have been developed to study these interactions, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Immobilized Binder Light-Based Sensors

Immobilized Binder Light-Based Sensors (IBLBS) represent a sophisticated approach for quantifying interactions between proteins and small molecules or nucleic acids. These techniques immobilize one interaction partner (ligand) on a sensor surface while the other partner (analyte) is introduced in solution, allowing real-time measurement of binding events [4].

Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI)

BLI utilizes white light reflection to measure molecular interactions through specialized biosensor tips. The technique employs constructive and destructive interference patterns generated when white light reflects from the sensor layer, with alterations in these patterns indicating molecular binding events [4]. As molecules bind to the tip surface, the optical thickness changes, resulting in wavelength shifts that are measured in real-time.

Key Advantages: BLI enables label-free detection and provides both kinetic data (association/dissociation rates) and affinity measurements (KD values). It can detect weak interactions with high sensitivity (limit of detection lower than 10 pg/mL) and is compatible with crude samples, including cell-free expression mixtures [4]. A significant benefit over some other techniques is the extended association phase measurement capability (up to 8000 seconds) due to diffusion-based analyte delivery.

Experimental Workflow:

- Functionalize biosensor tip with capture molecule (e.g., streptavidin, Ni-NTA)

- Immobilize ligand (protein or nucleic acid) on the tip

- Measure baseline signal in buffer solution

- Expose tip to analyte solution and monitor association phase

- Transfer tip to buffer solution and monitor dissociation phase

- Analyze binding curves to determine kinetic parameters

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

SPR measures molecular interactions through changes in the refractive index on a sensor chip surface. When analytes bind to immobilized ligands, the mass and charge changes alter the refractive index, which is detected as shifts in the resonance angle of reflected light [4]. Modern SPR instruments can measure nearly 400 interactions simultaneously, making the technique highly suitable for high-throughput applications in drug candidate characterization [4].

Key Advantages: SPR provides real-time, label-free analysis of binding events with high throughput capabilities. The technology offers robust and reliable reporting of kinetic data, making it particularly valuable for characterizing drug candidates. SPR has been optimized for detecting various biomarkers, including cancer biomarkers, through signal enhancement and dynamic range improvements [4].

Solution-Based Fluorescent Techniques (SBFTs)

Solution-Based Fluorescent Techniques monitor protein-small molecule interactions with both interaction partners free in solution, using labeled dyes or analytes as reporters [4]. These methods include fluorescence polarization (FP), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), and time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET). SBFTs are particularly valuable for studying interactions in physiologically relevant conditions and for high-throughput applications where solution-phase kinetics more closely mimic cellular environments.

Mass Spectrometry (MS) in HTS

Mass spectrometry techniques can measure interactions between proteins and small molecules by quantifying mass shifts in the native protein spectra [4]. MS-based approaches provide direct measurement of binding events without requiring labeling or immobilization, offering orthogonal validation for other HTS methods. Advanced MS techniques can characterize complex binding stoichiometries and detect post-translational modifications affected by small molecule binding.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful HTS implementation requires carefully selected reagents and materials that ensure assay robustness, reproducibility, and physiological relevance. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions essential for protein-small molecule interaction studies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for HTS of Protein-Small Molecule Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTS | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Engineered cell lines, Primary cells, Stem cells | Provide physiologically relevant environment for compound testing | Ensure relevance to native tissue; consider genetic background; verify expression of target protein [3] |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorescent dyes, Luminescent substrates, Antibodies | Enable quantification of binding events and cellular responses | Optimize for sensitivity and dynamic range; minimize background interference; validate specificity [3] |

| Ligand Immobilization Systems | Ni-NTA tips, Streptavidin biosensors, Protein A/G chips | Facilitate capture of proteins/nucleic acids for binding studies | Confirm immobilization efficiency; minimize nonspecific binding; ensure orientation preserves function [4] |

| Compound Libraries | Small molecule collections, Natural product extracts, Fragment libraries | Source of potential binders/modulators for screening | Ensure chemical diversity; verify compound integrity; consider physicochemical properties [3] |

| Buffer Components | Detergents, Reducing agents, Cofactors, Stabilizers | Maintain protein stability and function during assay | Optimize pH and ionic strength; include necessary cofactors; minimize nonspecific interactions [5] |

Comprehensive HTS Assay Validation Protocols

Rigorous validation is essential for ensuring that HTS assays generate reliable, reproducible data suitable for both industrial drug discovery and academic probe development. The following protocols outline critical validation steps based on established guidelines from the Assay Guidance Manual [5].

Reagent Stability and Storage Validation

Purpose: Determine optimal storage conditions and stability limits for all critical assay components to maintain assay performance over time and across multiple screening sessions.

Procedure:

- Prepare multiple aliquots of each reagent under proposed storage conditions (e.g., -80°C, -20°C, 4°C)

- Subject aliquots to multiple freeze-thaw cycles (0, 1, 3, 5 cycles) with testing after each cycle

- Assess long-term stability by testing reagents stored for different durations (1 week, 1 month, 3 months)

- Evaluate working solution stability by testing reagents held at assay temperature for various times (0, 1, 2, 4, 8 hours)

- For combination reagents, test stability of individual components and mixtures separately

Acceptance Criteria: Reagents should maintain ≥80% activity compared to fresh preparations after specified storage periods and freeze-thaw cycles. Critical reagents should show minimal activity loss (<15%) over the expected duration of a screening campaign.

DMSO Compatibility Testing

Purpose: Establish the tolerance of the assay system to dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the universal solvent for compound libraries in HTS.

Procedure:

- Prepare assay mixtures with DMSO concentrations spanning expected screening conditions (typically 0.1% to 5%, including planned screening concentration)

- Include DMSO-free controls as reference

- Run complete assay protocol with all DMSO concentrations in replicates (n≥8)

- Measure both signal window (Max-Min) and control well responses at each DMSO concentration

- Assess effects on assay kinetics by monitoring reaction progress at different DMSO levels

Acceptance Criteria: The selected DMSO concentration should not significantly affect assay signal window (Z'-factor ≥0.5), control well responses (CV <15%), or assay kinetics compared to DMSO-free conditions.

Plate Uniformity and Signal Variability Assessment

Purpose: Evaluate assay performance across entire microplates and between different plates/runs to identify spatial biases and ensure consistent performance.

Procedure - Interleaved-Signal Format:

- Prepare assay plates with systematic distribution of three signal levels:

- Max Signal: Maximum assay response (e.g., uninhibited enzyme activity, full agonist response)

- Min Signal: Background or minimum response (e.g., fully inhibited enzyme, buffer control)

- Mid Signal: Intermediate response (e.g., EC/IC50 concentration of control compound)

- Utilize standardized plate layouts with alternating signals across columns and rows

- Run minimum of three independent experiments on separate days with freshly prepared reagents

- For cell-based assays, include additional plates to assess edge effects and evaporation

- Analyze data for positional effects, temporal drift, and between-plate variability

Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate Z'-factor = 1 - [3×(σmax + σmin) / |μmax - μmin|]

- Determine signal-to-background ratio (S/B) = μmax / μmin

- Assess coefficient of variation (CV) for each signal type: CV = (σ/μ) × 100%

Acceptance Criteria: For robust HTS assays, Z'-factor should be ≥0.5, S/B ratio ≥5-fold, and CV for control wells <15% [5].

Advanced HTS Applications in Protein-Small Molecule Research

Carbohydrate-Lectin Binding Studies Using BLI

A recent innovative application combined cell-free expression (CFE) systems with BLI to analyze carbohydrate-lectin binding interactions. Researchers used streptavidin-coated BLI tips coated with biotinylated L-rhamnose to isolate rhamnose-binding lectins directly from crude cell-free expression mixtures without purification steps [4]. This approach enabled comprehensive analysis of lectin specificity toward different glycans through competition experiments, determining kinetic parameters (Kon, Koff, Kd) for various interactions. The study demonstrated translational relevance by measuring interactions between lectins and O-antigen, a Shigella serotype targeted in vaccine development [4].

Protein-Liposome Interaction Analysis

BLI was employed to study interactions between recombinant human erythropoietin (rh-Epo) and multilamellar liposomes, determining which liposome compositions interacted most effectively with the therapeutic protein [4]. Streptavidin BLI tips were loaded with biotinylated rh-Epo and exposed to different liposome formulations, with real-time monitoring of association and dissociation phases. Results revealed preferential binding to liposomes with more saturated lipid chains, providing insights for drug formulation development. This application highlighted BLI's advantage for studying weakly associating binding partners through extended association phase measurements (up to 8000 seconds) [4].

High-Throughput Screening for Drug Repurposing

HTS technologies are increasingly applied to drug repurposing initiatives, enabling rapid evaluation of existing drug libraries for new therapeutic applications. This approach significantly reduces development time and costs compared to de novo drug discovery [3]. The successful repurposing of sildenafil from hypertension treatment to erectile dysfunction therapy exemplifies the power of HTS in identifying novel applications for existing compounds. Implementation requires carefully designed assays that can detect unanticipated activities while controlling for false positives through robust validation and counter-screening strategies.

Implementation Considerations for Different Research Settings

Industrial Drug Discovery Implementation

Pharmaceutical HTS operations require robust, reproducible systems capable of processing millions of compounds with strict quality control. Key considerations include:

- Automation Integration: Implement seamless workflows connecting compound management, liquid handling, assay execution, and data processing

- Quality Control: Establish rigorous QC protocols including daily system suitability tests and periodic full validation

- Data Management: Develop infrastructure for storing, processing, and analyzing massive datasets generated by HTS campaigns

- Hit Triage: Create multi-parameter prioritization schemes to identify promising hits from primary screens

Academic Probe Development Implementation

Academic HTS operations often focus on specialized targets with more limited compound libraries, requiring:

- Resource Optimization: Adapt protocols for smaller scale with maintained robustness through careful statistical design

- Collaborative Networks: Leverage core facilities and consortia to access HTS infrastructure and expertise

- Follow-up Capacity: Plan secondary assay cascades early to efficiently validate screening hits

- Probe Criteria: Establish clear chemical and biological criteria for useful chemical probes before screening

The continuous innovation in HTS technologies, combined with rigorous validation and implementation practices, ensures that both industrial and academic researchers can reliably identify and characterize protein-small molecule interactions critical for advancing therapeutic development and biological understanding.

Chemical genetics represents a pivotal approach in modern biological research and drug discovery, employing small molecules to perturb and study complex biological systems with temporal and dose-dependent control [6]. This methodology serves as a critical bridge between phenotypic screening and target-based drug discovery, enabling researchers to deconvolute complex protein-small molecule interactions. The field is fundamentally divided into two complementary paradigms: forward and reverse chemical genetics.

Forward chemical genetics initiates with phenotypic observation of biological systems treated with small molecules, working backward to identify the molecular targets responsible for the observed effects [7] [8]. Conversely, reverse chemical genetics begins with a specific protein target of interest and seeks small molecules that modulate its function, subsequently observing the resulting phenotypic consequences [7] [6]. Both approaches provide powerful strategies to unravel biological pathways, identify novel drug targets, and advance therapeutic development, each with distinct advantages and methodological considerations.

Table: Core Characteristics of Forward and Reverse Chemical Genetics

| Characteristic | Forward Chemical Genetics | Reverse Chemical Genetics |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Phenotypic screening in biological systems [7] | Defined protein target [7] [6] |

| Primary Goal | Identify molecular targets of bioactive compounds [7] [8] | Discover modulators of specific protein function [7] [6] |

| Screening Context | Cells, tissues, or whole organisms [7] | Purified proteins or simplified systems [6] |

| Target Deconvolution | Required; often challenging [7] [8] | Not required; target is known a priori |

| Advantages | Unbiased discovery; identifies novel targets/pathways [7] | Straightforward SAR; rational design [7] |

| Limitations | Target identification can be difficult [8] | May overlook complex system biology [7] |

Core Methodologies and Workflows

Forward Chemical Genetics Screening Protocol

Forward chemical genetic screening follows a systematic, three-stage process to identify novel bioactive compounds and their cellular targets:

Phenotypic Screening:

- Compound Library Preparation: Utilize diverse small molecule collections (typically 10,000-100,000 compounds) in multi-well plate formats [6]. Libraries may include synthetic compounds, natural products, or known bioactive molecules.

- Biological System Treatment: Apply compounds to cells, tissues, or model organisms at appropriate concentrations (typically 1-10 μM) and time points [8].

- Phenotypic Assessment: Monitor for desired phenotypic changes using automated imaging, viability assays, transcriptional reporters, or other relevant readouts [8].

Target Identification:

- Chemical Probe Design: Convert bioactive hit compounds into chemical probes by incorporating affinity tags (biotin) or bio-orthogonal handles (azide/alkyne) while maintaining biological activity [7] [9].

- Target Enrichment: Incubate probes with biological systems, followed by covalent capture using photoaffinity labeling (for reversible binders) or inherent reactivity (for covalent binders) [7] [9].

- Protein Isolation and Identification: Enrich probe-bound proteins using affinity chromatography (streptavidin for biotinylated probes), followed by on-bead digestion and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis for protein identification [7] [9].

Target Validation:

- Competition Assays: Confirm binding specificity by demonstrating reduced probe binding in the presence of excess unmodified compound [8].

- Genetic Validation: Use RNAi, CRISPR/Cas9, or overexpression studies to determine if genetic manipulation of the putative target recapitulates the compound-induced phenotype [8].

- Functional Assays: Establish correlation between compound potency in phenotypic assays and binding affinity for the putative target [7].

Reverse Chemical Genetics Screening Protocol

Reverse chemical genetics employs a target-centric approach with the following methodology:

Target Selection and Protein Production:

- Select a purified, functionally active protein target relevant to the biological pathway or disease of interest.

- Ensure protein purity (>90%) and functional integrity through quality control assays.

In Vitro Compound Screening:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Screen compound libraries (typically 100,000-1,000,000 compounds) against the target using biochemical assays measuring binding or functional modulation [10].

- Primary Assay: Implement fluorescence-based, radiometric, or spectrophotometric assays in 384- or 1536-well plate formats with appropriate controls (blanks, positive/negative controls).

- Hit Selection: Identify initial hits based on statistical significance (typically >3 standard deviations from mean) and dose-response relationships.

Cellular Validation:

- Cellular Activity Assessment: Test compounds identified from in vitro screening in cellular models expressing the target protein.

- Selectivity Profiling: Evaluate compound specificity using counter-screens against related protein family members or general cytotoxicity assays.

- Phenotypic Characterization: Observe and document resulting cellular phenotypes following target engagement [6].

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis:

- Systematically modify hit compound structures to establish SAR and improve potency, selectivity, and physicochemical properties.

- Utilize structural biology (X-ray crystallography, NMR) where possible to guide rational compound optimization.

Key Research Reagents and Tools

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Genetics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Probe | Tool molecule with molecular recognition group, reactive group, and reporter tag [9] | Target identification and validation; must demonstrate high selectivity and potency [7] |

| Compound Libraries | Diverse collections of small molecules for screening [6] | Phenotypic screening (forward) or target-based screening (reverse); NIH library of ~500,000 compounds [6] |

| Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) Groups | Photoreactive moieties (aryl azide, benzophenone, diazirine) to capture transient interactions [9] | Mapping non-covalent small molecule-protein interactions in live cells [9] |

| Bio-orthogonal Handles | Chemical groups (azide, alkyne) for late-stage conjugation without disrupting biological systems [9] | Copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) for appending detection tags after target capture [9] |

| Affinity Tags | Molecular handles (biotin) for enrichment and purification [9] | Streptavidin-based pull-down of probe-bound proteins for MS identification [7] [9] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Analytical technique for protein identification and quantification [7] | Liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) for chemoproteomic target identification [7] |

Workflow Visualization

Forward vs. Reverse Chemical Genetics Workflows

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental differences between forward (yellow-to-green) and reverse (blue-to-green) chemical genetic approaches. Forward chemical genetics begins with phenotypic screening and progresses to target identification, while reverse chemical genetics initiates with a defined protein target and progresses to phenotypic analysis.

Comparative Analysis and Applications

Strategic Considerations for Approach Selection

The choice between forward and reverse chemical genetics depends heavily on research goals, available resources, and the biological context:

Novel Target Discovery: Forward chemical genetics excels at identifying novel druggable targets and pathways without predefined hypotheses about involved mechanisms [7]. This approach is particularly valuable for complex biological processes where key regulatory proteins remain unknown.

Pathway Elucidation: When studying poorly characterized phenotypic responses, forward approaches can reveal unexpected protein functions and pathway connections through unbiased target identification [10].

Target-Based Therapeutic Development: Reverse chemical genetics provides a direct path for developing modulators of well-validated targets with known disease relevance, enabling structure-based drug design [7].

Tool Compound Development: For investigating specific protein functions, reverse approaches efficiently generate selective chemical probes that complement genetic techniques [7].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biological Research

Both forward and reverse chemical genetics have contributed significantly to biomedical research and therapeutic development:

Pain Management: The discovery of COX-2 inhibitors emerged from reverse chemical genetics approaches targeting the cyclooxygenase pathway, building upon earlier understanding of aspirin's mechanism [6].

Immunosuppressants: Compounds like cyclosporine A were initially identified through phenotypic screening (forward approach), with subsequent target identification revealing their mechanisms of action [6].

Oncology Target Discovery: Forward screens identifying compounds with desired anti-proliferative or differentiation phenotypes have revealed novel cancer targets and mechanisms [7] [10].

Chemical Probe Development: Both approaches generate valuable chemical tools for studying protein function, with publicly available resources expanding access to these reagents [10].

Advanced Techniques and Emerging Technologies

Chemoproteomic Methods for Target Identification

Recent advancements in chemoproteomics have significantly enhanced target deconvolution capabilities in forward chemical genetics:

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): Utilizes electrophilic probes that covalently react with active site nucleophiles of specific enzyme families, enabling monitoring of enzyme activity and ligandability [9].

Photoaffinity Labeling (PAL) Strategies: Incorporates photoreactive groups (diazirines, benzophenones) that form covalent bonds with target proteins upon UV irradiation, capturing transient interactions for identification [9].

Cleavable Enrichment Tags: Implementation of photo-, chemically-, or enzymatically-cleavable linkers between affinity tags and chemical probes enables efficient elution of probe-modified peptides for precise binding site mapping [9].

Integrated Proteomic Workflows: Combination of PAL with isotopically labeled enrichment tags and advanced computational algorithms enables global profiling of small molecule binding sites directly in live cells [9].

Technological Innovations

High-Throughput Screening Automation: Robotic systems enable screening of >100,000 compounds per day in nanoliter-scale volumes, increasing efficiency while reducing reagent costs [10].

Advanced Mass Spectrometry: High-resolution LC-MS systems with improved sensitivity enable identification of low-abundance targets and precise mapping of binding sites [7] [9].

CRISPR Screening Integration: Combination of chemical genetic approaches with CRISPR-based genetic screening validates target engagement and identifies resistance mechanisms [7].

Chemical Bioinformatics: Publicly available databases and computational tools facilitate compound prioritization, target prediction, and mechanism analysis [10].

Forward and reverse chemical genetics represent complementary paradigms that together provide a powerful framework for investigating biological systems and advancing therapeutic discovery. Forward chemical genetics offers an unbiased approach to identify novel drug targets and biological mechanisms by starting with phenotypic observations, while reverse chemical genetics enables rational development of targeted therapeutics through focused modulation of specific proteins. The integration of advanced chemoproteomic methods, particularly photoaffinity labeling and activity-based protein profiling, has dramatically enhanced our ability to deconvolute complex small molecule-protein interactions. As chemical genomic resources continue to expand and technologies evolve, these approaches will remain essential for mapping biological pathways, validating therapeutic targets, and developing precision medicines that address unmet medical needs.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a fundamental methodology in modern drug discovery and protein-small molecule interaction research, enabling the rapid testing of hundreds of thousands of compounds against biological targets. The operational shift from manual processing to HTS constitutes a fundamental change in the scale and reliability of chemical and biological analyses, dramatically increasing the number of samples processed per unit time [11]. This paradigm shift is essential in modern drug discovery where target validation and compound library exploration require massive parallel experimentation. The scientific principle guiding HTS is the generation of robust, reproducible data sets under standardized conditions to accurately identify potential "hits" from extensive chemical libraries [11].

The capacity of HTS to rapidly identify novel lead compounds for new or established diseases provides significant advantages over rational drug design or structure-based approaches by enabling more rapid delivery of diverse drug leads [12]. However, these advantages come with associated challenges including substantial costs, technical complexity, and the potential for false positives and negative hits [12]. Successfully implementing HTS requires a deep understanding of assay robustness metrics and the seamless integration of specialized instrumentation, data management systems, and validated experimental protocols. The focus of current HTS development has shifted toward creating more practical, integrated systems that combine precision, transparency, and usability, with an emphasis on technologies that save time, connect data systems, and support biology that better reflects human complexity [13].

Core HTS System Components

Automation and Robotic Systems

The integration of sophisticated automation and robotics provides the precise, repetitive, and continuous movement required to realize the full potential of HTS workflows. Robotic systems form the core of any HTS platform, moving microplates between functional modules without human intervention to enable continuous, 24/7 operation that dramatically improves the utilization rate of expensive analytical equipment [11]. The primary types of laboratory robotics include Cartesian and articulated robotic arms for plate movement, and dedicated liquid handling systems for managing complex pipetting routines [11].

Modern HTS automation emphasizes usability and accessibility for scientists. The industry is experiencing a "third wave" of automation focused on empowering scientists to use automation confidently, saving time for analysis and thinking rather than manual tasks like pipetting [13]. This philosophy has led to the development of more ergonomic and user-friendly equipment, such as Eppendorf's Research 3 neo pipette, designed with input from working scientists to feature a lighter frame, shorter travel distance, and larger plunger to distribute pressure [13]. The sector is branching in two distinct directions: simple, accessible benchtop systems on one side, and large, unattended multi-robot workflows on the other [13]. Systems like Tecan's Veya liquid handler represent the first path, offering quick, walk-up automation that any researcher can use, while their FlowPilot software schedules complex workflows where liquid handlers, robots, and instruments operate seamlessly [13].

Table 1: Key Automation Modules in Integrated HTS Workflows

| Module Type | Primary Function | Technical Requirements | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handler | Precise fluid dispensing and aspiration | Sub-microliter accuracy; low dead volume | Beckman Echo 655 acoustic dispenser [14]; Agilent Bravo [14] |

| Robotic Plate Mover | Transfer microplates between instruments | High positioning accuracy; compatibility with labware | Cartesian and articulated robotic arms [11] |

| Plate Incubator | Temperature and atmospheric control | Uniform heating across microplates | Cytomat 5 C450 incubator [15] |

| Microplate Reader | Signal detection | High sensitivity and rapid data acquisition | Molecular Devices ImageXpress Micro Confocal [14]; BMG Clariostar Plus [14] |

| Plate Washer | Automated washing cycles | Minimal residual volume and cross-contamination control | Integrated washer-stackers [11] |

Effective system design ensures the smooth flow of materials, preventing bottlenecks at any single point. This engineering approach focuses on maximizing uptime and maintaining a standardized environment crucial for reliable HTS results [11]. The integration software, or scheduler, acts as the central orchestrator, managing the timing and sequencing of all actions, which is particularly critical for time-sensitive kinetic measurements [11]. Companies like SPT Labtech emphasize collaboration and interoperability in their automation platforms, as demonstrated by their firefly+ platform that combines pipetting, dispensing, mixing, and thermocycling within a single compact unit designed to simplify complex genomic workflows [13].

Microplate Technology and Selection

Microplates constitute the fundamental physical platform for HTS experiments, with format selection directly impacting assay performance, reagent consumption, and data quality. The evolution of microplate technology has enabled progressive miniaturization from 96-well to 384-well and 1536-well formats, significantly increasing throughput while reducing reagent volumes and associated costs [16] [12]. This miniaturization demands extreme precision in fluid handling that manual pipetting cannot reliably deliver across thousands of replicates [11].

The initial step in designing any HTS experiment involves selecting the appropriate microplate format based on specific assay requirements, throughput needs, and available instrumentation [16]. Standard plate formats have been optimized for various applications, with 96-well plates typically used for assay development and low-throughput validation, 384-well plates for medium- to high-throughput screening, and 1536-well plates for ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) [16]. Each format presents distinct advantages and challenges; for instance, while 1536-well plates enable tremendous throughput, they require specialized, high-precision dispensing equipment and are more susceptible to evaporation and edge effects [16].

Table 2: Microplate Formats and Applications in HTS

| Plate Format | Typical Assay Volume | Primary Application | Key Design Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| 96-well | 50-200 µL | Assay Development, Low-Throughput Validation | High reagent consumption |

| 384-well | 5-50 µL | Medium- to High-Throughput Screening | Increased risk of evaporation and edge effects |

| 1536-well | 2-10 µL | Ultra-High Throughput Screening (uHTS) | Requires specialized, high-precision dispensing |

Miniaturization protocols must carefully manage several physical parameters. Decreasing the liquid volume increases the surface-to-volume ratio, which accelerates solvent evaporation [16]. To counteract this, low-profile plates with fitted lids, humidified incubators, and specialized environmental control units are often integrated into the HTS workflow [16]. Furthermore, plate material selection (e.g., polystyrene, polypropylene, cyclic olefin copolymer) and surface chemistry (e.g., tissue culture treated, non-binding, or functionalized) must be rigorously tested to ensure compatibility with assay components and to mitigate non-specific binding of compounds or biological reagents [16]. Companies like Corning have developed specialized microplates with glass-bottom or COC film-bottom options that provide high-optical quality with industry-leading flatness, reducing autofocus time and improving high-content screening assay performance [17].

Detection and Reader Technologies

Detection technologies form the critical endpoint of HTS experiments, transforming biological interactions into quantifiable signals. HTS assays can be generally subdivided into biochemical or cell-based methods, each requiring appropriate detection methodologies [12]. Biochemical targets typically utilize enzymes and employ detection methods including fluorescence, luminescence, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), and differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) [12]. Fluorescence-based methods remain the most common due to their sensitivity, responsiveness, ease of use, and adaptability to HTS formats [12].

Modern detection systems have evolved to support increasingly complex assay requirements. High-content screening systems, such as the Molecular Devices ImageXpress Micro Confocal High-Content fluorescence microplate imager, combine imaging capabilities with multiparametric analysis, enabling detailed morphological assessment in addition to quantitative measurements [14]. Mass spectrometry-based methods of unlabeled biomolecules are becoming more generally utilized in HTS, permitting the screening of compounds in both biochemical and cellular settings [12]. The recent development of HT-PELSA (High-Throughput Peptide-centric Local Stability Assay) combines limited proteolysis with next-generation mass spectrometry to enable sensitive protein-ligand profiling in crude cell, tissue, and bacterial lysates, substantially extending HTS capabilities to membrane protein targets across diverse biological systems [18].

Detection systems must be carefully matched to assay requirements, considering factors such as sensitivity, dynamic range, compatibility with microplate formats, and speed of acquisition. For cell-based assays, systems capable of maintaining physiological conditions during reading, such as controlled temperature and atmospheric conditions, may be necessary. The trend toward more physiologically relevant 3D cell culture models further complicates detection requirements, often necessitating confocal imaging capabilities to capture signals throughout the depth of the sample [17]. As detection technologies advance, the integration of multiple detection modalities within single platforms provides researchers with greater flexibility in assay design and development.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Peptide-Centric Local Stability Assay (HT-PELSA) for Protein-Ligand Interaction Screening

Principle and Applications

HT-PELSA represents a significant advancement in proteome-wide mapping of protein-small molecule interactions, enabling the identification of potential binding sites by detecting protein regions stabilized by ligand binding through limited proteolysis [18]. This method substantially extends the capabilities of the original PELSA workflow by enabling sensitive protein-ligand profiling in crude cell, tissue, and bacterial lysates, allowing the identification of membrane protein targets in diverse biological systems [18]. The protocol increases sample processing efficiency by 100-fold while maintaining high sensitivity and reproducibility, making it particularly valuable for system-wide drug screening across a wide range of sample types [18].

Step-by-Step Workflow

Sample Preparation: Prepare cell, tissue, or bacterial lysates in appropriate buffer systems. For membrane protein targets, include compatible detergents to maintain protein solubility and function.

Ligand Incubation: Distribute lysates into 96-well plates and add ligands at desired concentrations. Include vehicle controls for reference samples. The high-throughput format enables testing multiple ligand concentrations in parallel for dose-response studies.

Limited Proteolysis: Add trypsin (or other appropriate protease) to each well and incubate for exactly 4 minutes at room temperature. The standardized digestion time ensures reproducibility across plates.

Digestion Termination: Acidify samples to stop proteolysis, maintaining consistent timing across all wells.

Peptide Separation: Transfer samples to 96-well C18 plates to remove intact, undigested proteins and large protein fragments. This step replaces molecular weight cut-off filters used in the original protocol, increasing throughput and compatibility with crude lysates.

Peptide Elution: Elute peptides using appropriate acetonitrile gradients directly into mass spectrometry-compatible plates.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze samples using next-generation mass spectrometry systems such as Orbitrap Astral, which improves throughput threefold and increases the number of identified targets by 22% compared to previous generation instruments [18].

The entire workflow requires under 2 hours for processing up to 96 samples from cell lysis to mass spectrometry-ready peptides, with the possibility to process multiple plates in parallel [18].

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Target Identification: Proteins are considered stabilized by the ligand if they become protected from digestion upon ligand binding. Peptides that show decreased abundance in the treatment-control comparison are classified as stabilized peptides [18].

Binding Affinity Determination: The high-throughput approach facilitates reproducible measurement of protein-ligand interactions across different ligand concentrations, enabling generation of dose-response curves and determination of half-maximum effective concentration (EC50) values for each protein target [18].

Quality Assessment: For kinase-staurosporine interactions, HT-PELSA demonstrates high precision with median coefficient of variation of 2% for pEC50 values across replicates [18].

Protocol 2: Robust Biochemical HTS Assay Development and Validation

Assay Design Principles

Biochemical HTS assays measure direct enzyme or receptor activity in a defined system, providing highly quantitative, interference-resistant readouts for enzyme activity [19]. Successful assay development requires creating systems that are robust, reproducible, and sensitive, with methods appropriate for miniaturization to reduce reagent consumption and suitable for automation [12]. Universal biochemical assays, such as the Transcreener platform capable of testing multiple targets due to their flexible design, provide significant advantages for screening diverse target classes including kinases, ATPases, GTPases, helicases, PARPs, sirtuins, and cGAS [19].

Validation Protocol

Assay Optimization: Determine optimal reagent concentrations, incubation times, and buffer conditions using statistical design of experiments (DoE) approaches. Test compatibility with detection method (fluorescence polarization, TR-FRET, luminescence, etc.).

Miniaturization Validation: Transition assay from initial format (typically 96-well) to target HTS format (384-well or 1536-well). Validate performance at reduced volumes, addressing challenges such as increased surface-to-volume ratio that accelerates solvent evaporation [16].

Robustness Testing:

- Compound Tolerance: Determine if compounds or their solvents (e.g., DMSO) interfere with assay performance [16].

- Plate Drift Analysis: Run control plates over a sustained period to confirm signal window stability, addressing potential issues related to reagent degradation or instrument warm-up [16].

- Edge Effect Mitigation: Identify and correct for systematic signal gradients across the plate caused by uneven heating or differential evaporation through strategic placement of controls or use of specific sealants [16].

Statistical Validation:

- Calculate Z'-factor using positive and negative controls: Z' = 1 - (3σp + 3σn)/|μp - μn|, where σp and σn are standard deviations of positive and negative controls, and μp and μn are their means [11]. A Z'-factor between 0.5 and 1.0 indicates an excellent assay [19].

- Determine signal-to-background ratio (S/B) and signal-to-noise ratio (S/N).

- Calculate coefficient of variation (CV) across wells and plates.

Automation Integration: Transfer validated assay to automated HTS system, verifying liquid handling accuracy, incubation timing, and detection parameters. Implement scheduling to maximize utilization rate of bottleneck instruments, typically the plate reader or most complex liquid handler [11].

Only after an assay demonstrates a consistent, acceptable Z'-factor should it proceed to full screening campaigns [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of HTS infrastructure requires careful selection of specialized reagents and materials optimized for automated, miniaturized formats. These solutions must provide consistency, reliability, and compatibility with the physical and chemical demands of high-throughput environments. The table below details essential research reagent solutions for protein-small molecule interaction studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTS | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Small molecule collections (225,000+ compounds [14]); cDNA libraries (15,000 cDNAs [14]); siRNA libraries (whole genome targeting [14]) | Source of potential modulators for targets | Library diversity, quality, relevance to target class, minimization of PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) [19] |

| Detection Reagents | Transcreener ADP² Assay [19]; Fluorescence polarization tracers; TR-FRET reagents | Signal generation for quantifying molecular interactions | Compatibility with detection platform, minimal interference, stability in assay buffer, homogenous format ("mix-and-read") |

| Microplates | Corning glass-bottom plates [17]; 384-well PCR plates [17]; 1536-well assay plates | Physical platform for miniaturized reactions | Well geometry, material composition, surface treatment, optical properties, automation compatibility |

| Cell Culture Systems | Corning Elplasia for spheroid formation [17]; 3D cell culture tools; Organoid counting software [17] | Biologically relevant screening environments | Physiological relevance, reproducibility, scalability, compatibility with automation and detection |

| Lysate Preparation | Lysis buffers with protease/phosphatase inhibitors; Membrane protein extraction reagents | Source of native protein targets | Preservation of protein activity and modification states, compatibility with detection method, minimal interference |

Workflow Integration and Data Management

Integrated HTS Workflow

The power of modern HTS emerges from the seamless integration of individual components into a continuous, optimized workflow. A fully integrated HTS system combines liquid handling systems, robotic plate movers, environmental control units, and detection systems into a coordinated platform [11]. Workflow optimization involves establishing a time-motion study for every process step, with the goal of maximizing the utilization rate of the "bottleneck" instrument—typically the reader or the most complex liquid handler—by minimizing plate transfer times and ensuring proper synchronization [16]. Scheduling software manages the timing of each plate movement, preventing traffic jams and ensuring precise kinetic timing for time-sensitive reactions [16].

Data Management and Quality Control

Managing the immense data output from HTS requires robust informatics systems to ensure data integrity and facilitate hit identification. Every microplate processed generates thousands of raw data points, often including intensity values, spectral information, and kinetic curves [11]. Accurately transforming this raw data into scientifically meaningful results requires a comprehensive laboratory information management system (LIMS) or similar data management infrastructure that tracks the source of every compound, registers plate layouts, and applies necessary correction algorithms (e.g., background subtraction, normalization) [11].

The volume and complexity of data generated by high-throughput screening necessitate specialized processing approaches. Raw data from microplate readers often requires normalization to account for systematic plate-to-plate variation [16]. Common normalization techniques include Z-Score normalization (expressing each well's signal in terms of standard deviations away from the mean of all wells on the plate) and Percent Inhibition/Activation (calculating the signal relative to positive controls) [16]. These normalization steps convert raw photometric or fluorescent values into biologically meaningful, comparable metrics, allowing for consistent evaluation of compound activity across the entire screen [16].

Quality control metrics extend beyond the Z'-factor to include the Signal-to-Background Ratio (S/B), which should be sufficiently large to ensure the signal is detectable above background noise, and the Control Coefficient of Variation (CV), which should remain low to indicate good well-to-well reproducibility [16]. Plates that fail to meet pre-defined QC thresholds must be flagged or excluded from analysis to maintain data integrity [16]. The emergence of AI and machine learning approaches is helping to address the fundamental issue of false positive data generation in HTS, with methods based on expert rule-based approaches (e.g., pan-assay interferent substructure filters) or ML models trained on historical HTS data [12]. Successfully managing HTS data ultimately depends on treating the entire system—from compound management to data analysis—as a single, cohesive unit rather than merely a collection of individual instruments [11].

The global High-Throughput Screening (HTS) market is experiencing substantial growth, driven by increasing demand for efficient drug discovery processes and the integration of advanced technologies. The market expansion is quantified across multiple reports as shown below.

Table 1: Global High-Throughput Screening Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Aspect | 2025 Base Value | 2032/2035 Projection | CAGR (%) | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Market Size | USD 26.12-27.14 billion [20] [21] | USD 53.21-75 billion [20] [21] | 10.6-10.7% [22] [20] [21] | Drug discovery demand, automation, chronic disease burden |

| Instrument Segment Share | 49.3% [21] | - | - | Automation precision, liquid handling systems |

| Cell-Based Assays Segment Share | 33.4% [21] | - | - | Physiologically relevant screening models |

| Drug Discovery Application Share | 45.6% [21] | - | - | Rapid candidate identification needs |

| North America Regional Share | 39.3-50% [22] [21] | - | - | Strong biopharma ecosystem, R&D spending |

| Asia Pacific Regional Share | 24.5% [21] | - | - | Expanding pharmaceutical industries, government initiatives |

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening Market Segmentation Analysis

| Segment Type | Leading Segment | Market Share (%) | Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product & Services | Consumables [20] | Largest segment | Increasing drug discovery needs, advanced HTS trials |

| Technology | Cell-Based Assays [21] | 33.4% [21] | Physiological relevance, functional genomics |

| Application | Target Identification [22] | USD 7.64 billion (2023) [22] | Chronic disease prevalence, regulatory demands |

| End-user | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology [22] [20] | Largest segment | Widespread use for chronic disease treatments |

Technological Drivers: Automation and AI Integration

The Role of Automation in Overcoming HTS Limitations

Automation addresses critical challenges in traditional HTS workflows, including variability, human error, and data handling complexities [23]. Automated systems enhance reproducibility through standardized protocols and integrated verification features, such as DropDetection technology that confirms liquid dispensing accuracy [23]. The implementation of automated work cells enables screening of thousands of compounds with minimal manual intervention, significantly increasing throughput while reducing operational costs through miniaturization [23] [24].

Key Benefits of Automation in HTS:

- Reproducibility Enhancement: Standardized workflows reduce inter- and intra-user variability, addressing the >70% irreproducibility rate reported by researchers [23]

- Cost Reduction: Miniaturization capabilities reduce reagent consumption and overall costs by up to 90% [23]

- Efficiency Gains: Automated platforms screen thousands of compounds in significantly reduced timeframes, with some systems processing 40 plates in approximately 8 hours [24]

- Data Quality Improvement: Integrated sensors and verification systems ensure reliable data collection and documentation [23]

AI as a Transformative Force in HTS

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), is reshaping HTS by enabling predictive compound selection and data analysis. The AtomNet convolutional neural network has demonstrated the capability to successfully identify novel hits across diverse therapeutic areas and protein classes, achieving an average hit rate of 6.7-7.6% across 318 targets [25]. AI-driven systems can screen synthesis-on-demand libraries comprising trillions of molecules, vastly exceeding the capacity of physical HTS libraries [25].

AI Applications in HTS Workflows:

- Virtual Screening: AI systems can process billions of compound-target interactions, ranking molecules by predicted binding probability without physical screening [25]

- Hit Identification: ML algorithms prioritize compounds with higher likelihood of bioactivity, reducing false positives and negatives [26]

- Multi-parameter Optimization: AI integrates HTS data with multi-omics and clinical data to predict efficacy, toxicity, and mechanism of action [26] [27]

- Novel Target Identification: AI analysis uncovers unrecognized patterns and correlations, leading to discovery of new biological targets [26]

Automated HTS with AI-Enhanced Analysis Workflow

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols for Protein-Small Molecule Interaction Screening

Automated HTS Protocol for Protein-Small Molecule Binding Assays

Objective: To identify small molecule binders to a target protein using an automated, high-throughput fluorescence-based assay.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified target protein in appropriate buffer

- Compound library (1,280 compounds in 384-well format)

- Assay buffer (optimized for protein stability and binding)

- Fluorescent tracer ligand

- Reference controls (positive/negative)

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein-Small Molecule HTS

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Specifications | Example Vendor/Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precise nanodispensing of compounds and reagents | 384/1536-well capability, nanoliter precision | Agilent Bravo, Tecan Fluent, Hamilton Vantage [24] |

| Microplate Reader | Detection of binding signals | Multimode (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance) | PerkinElmer EnVision [20] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Physiologically relevant screening | 3D cell models, organ-on-chip | INDIGO Biosciences Reporter Assays [21] |

| Non-Contact Dispenser | Reagent addition without cross-contamination | DropDetection verification | I.DOT Liquid Handler [23] |

| Automated Incubator | Maintain optimal assay conditions | Temperature, COâ‚‚, humidity control | HighRes ELEMENTS System [24] |

Procedure:

Assay Preparation (Automated Workcell)

- Program liquid handler to transfer 10 nL of each compound (10 mM in DMSO) to black, solid-bottom 384-well assay plates

- Include control wells: positive control (known binder), negative control (DMSO only), and reference compound

- Dilute target protein in assay buffer to 2x final concentration

Protein-Compound Incubation

- Using non-contact dispenser, add 10 μL of protein solution to all wells

- Seal plates and incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature with shaking (300 rpm)

- Add 10 μL of fluorescent tracer ligand (2x Kd concentration) using bulk dispenser

Signal Detection and Analysis

- Incubate plates for additional 60 minutes in the dark

- Read fluorescence polarization/intensity using microplate reader with appropriate filters

- Transfer data to AI analysis platform for hit identification

Validation Parameters:

- Z'-factor >0.5 for robust assay performance [22]

- Signal-to-background ratio >3:1

- Coefficient of variation <10% for control wells

AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening Protocol

Objective: To computationally screen ultra-large chemical libraries for potential binders before synthesis and physical testing.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Target protein structure (X-ray crystal, cryo-EM, or homology model)

- Synthesis-on-demand chemical library (e.g., 16-billion compound space) [25]

- AtomNet or equivalent convolutional neural network platform [25]

- High-performance computing infrastructure (CPU/GPU clusters)

Procedure:

Structure Preparation

- Prepare protein structure by removing water molecules and adding hydrogen atoms

- Define binding site coordinates based on known ligand interactions or predicted binding pockets

Virtual Library Preparation

- Filter commercial catalog compounds based on drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five)

- Generate 3D conformers for each compound with rotational isomers

- Remove compounds structurally similar to known binders of the target or homologs

Neural Network Screening

- Score each protein-ligand complex using the AtomNet model, which analyzes 3D coordinates of generated complexes

- Rank compounds by predicted binding probability

- Cluster top-ranked molecules to ensure scaffold diversity

- Algorithmically select highest-scoring exemplars from each cluster without manual cherry-picking

Hit Selection and Validation

- Select 50-100 top-ranking compounds for synthesis and purchasing

- Validate computational predictions using the experimental protocol in section 3.1

- Iteratively refine AI model based on experimental results

AI-Driven Virtual Screening and Validation Workflow

Case Studies and Validation Data

Large-Scale Validation of AI-Driven Screening

In the largest reported virtual HTS campaign comprising 318 individual projects, the AtomNet convolutional neural network successfully identified novel hits across every major therapeutic area and protein class [25]. The system demonstrated particular effectiveness for challenging target classes including protein-protein interactions, allosteric sites, and targets without known binders or high-quality structures.

Key Performance Metrics:

- 91% success rate in identifying single-dose hits that were reconfirmed in dose-response experiments [25]

- Average hit rate of 6.7% for internal projects and 7.6% for academic collaborations [25]

- Successful hit identification using homology models with average sequence identity of only 42% to template proteins [25]

- 26% average hit rate in analog expansion rounds, compared to typical HTS hit rates of 0.001-0.15% [25]

Automation-Enhanced Screening Efficiency

Implementation of integrated automation systems has demonstrated significant improvements in HTS operational efficiency:

Throughput and Cost Metrics:

- Reduction in development timelines by approximately 30%, enabling faster market entry for new drugs [22]

- 90% reduction in manual steps in cell line development through automated screening systems [21]

- 15% reduction in operational costs through automated workflows and miniaturization [22] [23]

- 5-fold improvement in hit identification rates compared to traditional methods [22]

Future Perspectives and Implementation Recommendations

The convergence of automation and AI technologies is positioned to further transform the HTS landscape. Emerging trends include the development of autonomous agentic AI systems that can navigate entire discovery pipelines with minimal human intervention [28], increased integration of 3D cell models and organ-on-chip technologies for more physiologically relevant screening [21], and the growth of AI-driven contract research services offering specialized screening capabilities [26].

Implementation Considerations for Research Organizations:

Workflow Integration: Prioritize flexible automation platforms that can accommodate existing devices while allowing for future technology upgrades [24]

Data Infrastructure: Establish robust data management systems capable of handling multiparametric data generated by AI-enhanced HTS platforms [23] [26]

Talent Development: Address the critical shortage of professionals trained in both experimental biology and computational sciences through specialized training programs [22] [23]

Hybrid Approaches: Implement complementary physical and virtual screening strategies to maximize coverage of chemical space while leveraging the strengths of both methodologies [28] [25]

Advanced HTS Methodologies: From Biochemical Assays to System-Wide Profiling

The discovery and optimization of protein-small molecule interactors is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and basic biomedical research. High-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns rely on robust, sensitive, and reproducible biochemical binding assays to identify and characterize compounds that modulate therapeutic targets. Among the most powerful tools for investigating these interactions are fluorescence polarization (FP), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET), and surface-coated microscale methods (SMMs). These homogeneous assay formats provide solution-based measurements under physiological buffer conditions, enabling the determination of binding affinity, kinetics, and compound potency for structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. This article details the practical application of these technologies, providing standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to accelerate research in both academic and industrial settings.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biochemical Binding Assay Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Typical Throughput | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Measures change in molecular rotation/tumbling speed of a fluorescent tracer upon binding. | High | Homogeneous, simple setup, low reagent consumption, ideal for small molecule binding. | Fragment screening, competitive binding assays, protein-peptide interactions. |

| Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | Energy transfer between a donor and acceptor fluorophore in close proximity (1-10 nm). | Medium to High | Distance-dependent, ratiometric measurement, can be used in live cells. | Protein-protein interactions, protease assays, conformational changes. |

| Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) | FRET combined with long-lifetime lanthanide donors to delay measurement, reducing background fluorescence. | High | Reduced compound autofluorescence interference, robust for HTS, ratiometric. [29] | Nuclear receptor ligand screening, protein-small molecule interactions, post-translational modification studies. [29] [30] |

| Surface-Coated Microscale Methods (SMMs) | Binding interactions measured on a functionalized surface. | Variable (Lower throughput) | Can measure on/off rates, no need for fluorescent labeling of one partner. | Kinetic characterization, interactions where labeling is detrimental. |

Fluorescence Polarization (FP) Assays

Principle and Applications

Fluorescence Polarization measures the change in the rotational diffusion of a small, fluorescently labeled molecule (tracer) when it is bound by a larger protein. A small molecule rotates quickly in solution, leading to low polarization when excited with polarized light. Upon binding to a much larger, slower-tumbling protein, its rotation is hindered, resulting in a significant increase in the emitted polarized light. FP is particularly well-suited for HTS to identify inhibitors of protein-small molecule interactions, as it is a homogeneous, mix-and-read assay that requires no separation steps.

Detailed FP Protocol for Competitive Binding

This protocol is designed to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of a test compound against a fluorescent tracer for a target protein.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Assay Buffer | Provides physiological pH and ionic strength. Common components: Tris or HEPES, NaCl, DTT, and a non-ionic detergent like Tween-20. [29] |

| Black, Low-Volume, 384-Well Microplates | Minimizes background fluorescence and signal cross-talk between wells while reducing reagent consumption. [29] |

| Fluorescent Tracer | A known, high-affinity ligand for the target protein, labeled with a bright, photostable fluorophore (e.g., Fluorescein, TAMRA). |

| Purified Target Protein | The protein of interest, purified to homogeneity. Concentration must be optimized to ensure a strong signal window. |

| Test Compounds | Small molecules or libraries to be screened for inhibitory activity. |

| FP-Capable Microplate Reader | Instrument with polarizing filters to excite with polarized light and detect parallel and perpendicular emission intensities. |

Procedure:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a suitable assay buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 2 mM DTT). Filter through a 0.22 µm membrane to remove particulates. [29]

- Compound Dilution: Serially dilute test compounds in DMSO or buffer in a 384-well polypropylene source plate. Include a negative control (DMSO or buffer only) and a positive control (a known potent inhibitor if available).

- Reaction Assembly: In the 384-well assay plate, combine the following using a multichannel pipette or liquid dispenser:

- Test compound or control: 1 µL

- Purified target protein: 5 µL in assay buffer (at a concentration pre-determined from optimization, typically near the Kd for the tracer)

- Fluorescent tracer: 4 µL in assay buffer (at a concentration near its Kd)

- Final assay volume: 10 µL [29]

- Incubation: Seal the plate with a clear cover, mix gently on a plate shaker for 1 minute, and centrifuge at 1000 × g for 2 minutes. Allow the plate to incubate in the dark at room temperature for 1-2 hours to reach equilibrium.

- Data Acquisition: Read the plate on an FP-capable microplate reader. The instrument will calculate millipolarization (mP) units based on the parallel (I‖) and perpendicular (I⊥) emission intensities: mP = 1000 * (I‖ - I⊥) / (I‖ + I⊥).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage inhibition for each compound well: % Inhibition = 100 * [1 - (mPsample - mPmin) / (mPmax - mPmin)], where mPmax is the average mP of the negative control (no inhibitor) and mPmin is the average mP of the positive control (full inhibition).

- Plot % Inhibition versus the logarithm of compound concentration and fit the data with a four-parameter logistic model to determine the IC50 value.

FRET and Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) Assays

Principle and Applications

FRET is a distance-dependent physical process where energy is transferred from an excited donor fluorophore to a proximal acceptor fluorophore. This transfer results in reduced donor emission and increased acceptor emission (sensitized emission). [31] [32] TR-FRET enhances this technology by utilizing lanthanide chelates (e.g., Europium, Eu) as donors, which have long fluorescence lifetimes. By introducing a delay between excitation and measurement, short-lived background fluorescence from compounds or buffer components is eliminated, leading to a vastly improved signal-to-noise ratio. [29] This makes TR-FRET exceptionally robust for HTS and quantitative applications, such as determining protein-protein interaction affinity (KD). [33]

Detailed TR-FRET Protocol for Protein-Small Molecule Interaction

This protocol uses a generalized, "plug-and-play" TR-FRET platform for a histidine-tagged protein and a biotinylated small molecule or peptide tracer. [29]

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| LANCE Europium (Eu)-Streptavidin | Donor molecule. Binds tightly to the biotinylated tracer. [29] |

| ULight-anti-6x-His Antibody | Acceptor molecule. Binds to the histidine-tagged protein. [29] |

| 6X-His-Tagged Target Protein | The protein of interest, purified with an affinity tag for detection. |

| Biotinylated Tracer Ligand | A high-affinity ligand for the target protein, conjugated to biotin. |

| TR-FRET Compatible Assay Plates | White, low-volume, non-binding surface plates to maximize signal reflection and minimize adhesion. [29] |

| Time-Resolved Fluorescence Plate Reader | Instrument capable of exciting the donor and measuring emission at specific wavelengths after a time delay. |

Procedure:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare Kme reader buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 2 mM DTT) or a buffer appropriate for your target. [29]

- Compound and Reagent Dilution: Dilute test compounds in DMSO or buffer. Prepare a master mix containing the His-tagged protein, biotinylated tracer, Eu-streptavidin, and ULight-anti-6x-His antibody in assay buffer. The concentrations of all components must be optimized in advance; a typical final concentration for the tracer and protein is in the low nanomolar range. [29]

- Reaction Assembly: Dispense the master mix into a white, low-volume 384-well plate. Add test compounds or controls.

- Final assay volume: 10 µL [29]

- Incubation: Seal the plate, mix, centrifuge, and incubate in the dark for 1-2 hours to allow the binding reaction and TR-FRET complex to form.

- Data Acquisition: Read the plate on a compatible reader (e.g., EnVision). The instrument will use a time-delayed measurement. The TR-FRET signal is calculated as the ratio of acceptor emission (e.g., 665 nm) to donor emission (e.g., 615 nm). [29]

Data Analysis: The ratiometric nature of the TR-FRET signal (Acceptor Emission / Donor Emission) normalizes for well-to-well volume variations and compound interference. [29] Data can be analyzed as a percentage of control activity, similar to the FP protocol, to generate IC50 values for inhibitors.

TR-FRET Experimental Workflow

Advanced Applications and Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative FRET (qFRET) for KD Determination

A significant advancement in FRET technology is the development of quantitative FRET (qFRET) methods to determine the dissociation constant (KD) of protein-protein interactions directly in a mixture. [33] This approach differentiates the absolute FRET signal (EmFRET) arising from the interactive complex from the direct emissions of the free donor and acceptor fluorophores. The procedure involves measuring fluorescence emissions at specific wavelengths upon donor excitation and using cross-wavelength correlation constants to calculate the pure FRET signal. The concentration of the bound complex derived from EmFRET is then used in a binding isotherm plot to calculate the KD, providing a sensitive and high-throughput alternative to traditional methods like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). [33]

Flow Cytometry-Based FRET in Living Cells

To study protein-protein interactions in their physiological context, flow cytometry-based FRET in living cells is a powerful technique. This method uses fluorescent protein pairs (e.g., Clover/mRuby2) and flow cytometry to detect FRET efficiency in large populations of cells. [32] It allows for the analysis of binding intensities and the effect of pharmacological agents on these interactions. For instance, this system has been used to characterize the interaction between the nuclear receptor PPARγ1 and its corepressor N-CoR2, demonstrating that binding persists even upon receptor antagonism. [32] This high-throughput, cell-based approach bridges the gap between in vitro biochemistry and cellular physiology.

FRET Mechanism and Readout

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Binding Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Signal Window (FP/TR-FRET) | Protein or tracer concentration is suboptimal. | Perform a checkerboard titration to determine optimal concentrations. Ensure protein is active. |

| High Background Signal | Non-specific binding of components. | Include a non-ionic detergent (e.g., Tween-20) in the buffer, optimize blocking agents. |

| Compound Interference (FP) | Inherent fluorescence of test compounds. | Use a red-shifted fluorophore for the tracer or switch to a TR-FRET format. [29] |

| Low FRET Efficiency | Poor spectral overlap or fluorophore orientation. | Select a FRET pair with minimal cross-talk (e.g., CFP/YFP, Clover/mRuby2). [31] [32] |

| High Well-to-Well Variation | Pipetting inaccuracies or plate effects. | Use liquid handling automation, ensure homogeneous mixing after reagent addition. |

A critical best practice is the careful validation of assay performance before initiating a full HTS campaign. Key parameters to establish include the Z'-factor (a measure of assay robustness and suitability for HTS, with values >0.5 being acceptable), signal-to-background ratio, and intra-assay coefficient of variation. Furthermore, hit validation should always include counter-screens and secondary assays in an orthogonal format (e.g., following a TR-FRET screen with an SPR assay) to eliminate false positives arising from compound interference or assay-specific artifacts. [34]

Cell-Based Phenotypic Screening for Functional Outcomes

Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD) has re-emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying first-in-class medicines by focusing on the modulation of disease phenotypes rather than predefined molecular targets [35]. Modern PDD leverages physiologically relevant models—including immortalized cell lines, primary cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)—to screen for compounds that elicit therapeutic effects in realistic disease contexts [35] [36]. This approach has successfully expanded the "druggable target space," uncovering novel mechanisms of action (MoA) and enabling the development of therapies for complex diseases where single-target strategies have faltered [35]. This Application Note details the essential protocols, assays, and analytical frameworks for implementing cell-based phenotypic screens aimed at detecting functional outcomes, providing a practical guide for researchers in high-throughput screening for protein-small molecule interactors.

Key Principles and Assay Selection

Phenotypic screening's value lies in its ability to identify chemical tools that link therapeutic biology to previously unknown signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms [35]. Success depends on a carefully considered screening strategy that balances biological relevance with practical feasibility.

Core Principles for Screen Design