Independent Prognostic lncRNA Biomarkers in HCC: From Multivariate Cox Validation to Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes current advancements in validating long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) prognosis using multivariate Cox regression models.

Independent Prognostic lncRNA Biomarkers in HCC: From Multivariate Cox Validation to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes current advancements in validating long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) prognosis using multivariate Cox regression models. It explores the foundational role of specific lncRNAs across biological processes like amino acid metabolism and ferroptosis, detailing rigorous methodologies for constructing multi-lncRNA signatures. The content addresses critical challenges in analytical optimization and troubleshooting, and emphasizes the necessity of robust validation through functional assays and clinical correlation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive framework for developing clinically actionable lncRNA-based prognostic tools to guide personalized therapy and improve patient outcomes in HCC.

The Landscape of Prognostic lncRNAs in HCC: Core Biological Functions and Pathways

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a significant global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most prevalent cancer worldwide and the fourth most common cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. As the predominant histological form of primary liver cancer, HCC constitutes more than 90% of total liver cancer cases worldwide, with its pathogenesis involving complex biological processes including DNA damage, epigenetic modification, and oncogene mutation [2] [3]. Over the past two decades, the role of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)—RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding capacity—has received increasing attention in HCC research [2]. These molecules have emerged as crucial regulators of gene expression through multiple mechanisms: serving as signaling molecules that recruit transcription factors; acting as guiding molecules that direct chromatin-modifying enzymes to specific genomic locations; functioning as decoy molecules that sequester transcription factors or microRNAs; and working as scaffolding molecules that mediate the formation of multi-component complexes [3].

The investigation of lncRNAs in HCC has progressed from initial observations of dysregulated expression to sophisticated multivariate Cox regression analyses that validate their independent prognostic significance. This evolution has positioned lncRNAs as promising biomarkers for prognostic assessment and potential targets for therapeutic intervention. The functional characterization of these molecules reveals a complex regulatory network where specific lncRNAs can act either as oncogenes promoting tumor development or as tumor suppressors inhibiting carcinogenesis [4] [2]. This comparative analysis systematically examines the roles of dysregulated lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis, focusing on their validated prognostic significance through multivariate Cox regression studies, with the aim of providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for understanding this dynamic field.

Oncogenic lncRNAs in HCC: Mechanisms and Prognostic Value

Oncogenic lncRNAs demonstrate upregulated expression in HCC tissues and contribute to tumor development and progression through diverse molecular mechanisms. These molecules promote malignant phenotypes including uncontrolled cell proliferation, enhanced metastatic potential, evasion of apoptosis, and treatment resistance. Their elevated expression consistently correlates with advanced disease stage and poorer clinical outcomes, making them valuable prognostic indicators and potential therapeutic targets.

Table 1: Key Oncogenic lncRNAs in HCC and Their Prognostic Significance

| lncRNA Name | Expression in HCC | Molecular Mechanisms | Prognostic Value (Multivariate Cox Analysis) | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINC00152 | Upregulated [1] | Promotes cell proliferation through regulation of CCDN1 [1] | HR: 2.524; 95% CI: 1.661-4.015; P=0.001 for shorter OS [3] | Independent prognostic biomarker; potential therapeutic target |

| LINC01063 | Upregulated [5] | Regulates ferroptosis; promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [5] | Part of 7-FRlncRNA signature predicting outcome [5] | Component of ferroptosis-related prognostic signature; oncogenic driver |

| UCA1 | Upregulated [1] | Promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of HCC cells [1] | Combined with other lncRNAs improves diagnostic power [1] | Diagnostic biomarker, especially in combination panels |

| HOTAIR | Upregulated [4] | Competes with BRCA1 protein; regulated by mir-7 and mir-34a [4] | Associated with poor overall survival and disease-free survival [1] | Prognostic biomarker; promotes invasion and metastasis |

| H19 | Upregulated [2] | Stimulates CDC42/PAK1 axis by down-regulating miRNA-15b [2] | Contributes to HCC progression [2] | Oncogenic role; potential therapeutic target |

| ANRIL | Upregulated [4] | Enhances tumor growth in various cancers [4] | Positive correlation with poor prognosis in osteosarcoma [4] | Potential pan-cancer oncogenic marker |

| LINC01094 | Upregulated [3] | Not fully characterized | HR: 2.091; 95% CI: 1.447-3.021; P<0.001 for shorter OS [3] | Independent prognostic biomarker |

The functional validation of oncogenic lncRNAs extends beyond correlation studies to direct experimental demonstration of their cancer-promoting properties. For instance, LINC01063 was comprehensively validated as an oncogene in HCC through both in vitro and in vivo experiments. Knockdown of LINC01063 inhibited cell proliferation, disrupted colony formation ability, and reduced the migration and invasion capacities of HCC cells. In vivo studies using nude BALB/c mice injected with LINC01063-knockdown HCC cells exhibited reduced tumor growth compared to controls, providing direct evidence of its oncogenic function [5]. Similarly, H19 has been shown to affect proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis of HCC cells through epigenetic modification, drug resistance, and regulation of downstream pathways [2].

The prognostic significance of these oncogenic lncRNAs has been rigorously validated through multivariate Cox regression analyses, confirming their independent value in predicting patient outcomes. For example, high pre-treatment expression of LINC00152 in tumor tissues independently predicted shorter overall survival (HR: 2.524; 95% CI: 1.661-4.015; P=0.001) in 63 HCC patients treated with curative surgical resection [3]. Similarly, LINC01094 expression was identified as an independent factor associated with shorter overall survival (HR: 2.091; 95% CI: 1.447-3.021; P<0.001) in 365 HCC patients [3]. These robust statistical analyses controlling for other clinical variables strengthen the case for incorporating these molecular markers into clinical prognostic assessment.

Figure 1: Mechanism of Action for Oncogenic lncRNAs in HCC. Oncogenic lncRNAs drive hepatocellular carcinoma progression through multiple molecular mechanisms including epigenetic regulation, miRNA sponging, and protein interactions, ultimately leading to enhanced proliferation, invasion, and treatment resistance.

Tumor-Suppressor lncRNAs in HCC: Protective Functions and Clinical Significance

Tumor-suppressor lncRNAs exhibit downregulated expression in HCC tissues and normally function to constrain malignant transformation and tumor progression. The loss of their protective activity through silencing or reduced expression removes critical brakes on cellular proliferation and creates a permissive environment for carcinogenesis. The restoration of their function represents a promising therapeutic strategy for HCC treatment.

Table 2: Key Tumor-Suppressor lncRNAs in HCC and Their Prognostic Significance

| lncRNA Name | Expression in HCC | Molecular Mechanisms | Prognostic Value (Multivariate Cox Analysis) | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAS5 | Downregulated [1] | Triggers CHOP and caspase-9 signal pathways; affects miR-32-5p/PTEN axis [4] [1] | Higher LINC00152 to GAS5 ratio correlated with increased mortality [1] | Tumor suppressor; inhibits cancer cell development and metastasis |

| LINC01146 | Downregulated [3] | Not fully characterized | HR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.16-0.92; P=0.033 for longer OS [3] | Independent favorable prognostic biomarker |

| LINC01554 | Downregulated [3] | Not fully characterized | Low expression: HR: 2.507; 95% CI: 1.153-2.832; P=0.017 for shorter OS [3] | Independent prognostic biomarker |

| LASP1-AS | Downregulated [3] | Not fully characterized | Low expression: HR: 1.884; 95% CI: 1.427-2.841; P<0.0001 for shorter OS [3] | Independent prognostic biomarker |

| MEG3 | Downregulated [6] | Multiple tumor suppressor functions | Associated with tumor expansion, metastasis, prognosis [6] | Potential tumor suppressor lncRNA |

The molecular mechanisms of tumor-suppressor lncRNAs involve constraining key cancer-promoting pathways and activating cellular processes that inhibit malignant transformation. GAS5, for instance, has been demonstrated to inhibit invasion, migration, and proliferation of colorectal cancer HT-29 cells, and induces apoptosis in these cells [4]. In pancreatic carcinoma, overexpression of GAS5 prevents cancer cells from developing and metastasizing by affecting the miR-32-5p/PTEN axis [4]. This lncRNA represents a compelling example of a tumor suppressor with potential relevance across multiple cancer types, including HCC.

The prognostic significance of tumor-suppressor lncRNAs is evident in multivariate Cox regression analyses, where their reduced expression independently predicts unfavorable outcomes. For example, a low pre-treatment expression level of LINC01554 in tumor tissues was an independent predictor for shorter overall survival (HR: 2.507; 95% CI: 1.153-2.832; P=0.017) in 167 HCC patients treated with curative surgical resection [3]. Similarly, low expression of LASP1-AS independently predicted shorter overall survival in both training (HR: 1.884; 95% CI: 1.427-2.841; P<0.0001) and validation cohorts (HR: 3.539; 95% CI: 2.698-6.030; P<0.0001) encompassing 423 HCC patients [3]. These findings highlight the clinical importance of preserving the function of these protective lncRNAs.

The ratio between oncogenic and tumor-suppressor lncRNAs may provide even more powerful prognostic information than individual markers. One study found that a higher LINC00152 to GAS5 expression ratio significantly correlated with increased mortality risk, suggesting that the balance between competing lncRNA influences may critically determine disease outcome [1]. This ratio-based approach acknowledges the complex interplay within lncRNA networks and may offer enhanced prognostic precision.

Multivariate Cox Regression Studies: Validating lncRNA Prognostic Signatures

The application of multivariate Cox regression analysis has been instrumental in validating the independent prognostic value of lncRNA biomarkers in HCC, accounting for potential confounding factors such as age, sex, disease stage, and treatment modality. These rigorous statistical approaches have evolved from examining single lncRNAs to constructing multi-lncRNA signatures that offer superior predictive accuracy.

Table 3: Multivariate Cox Regression-Validated lncRNA Signatures in HCC

| lncRNA Signature | Number of lncRNAs | Study Cohort | Statistical Performance | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferroptosis-Related Signature [5] | 7 FRlncRNAs | 365 HCC patients (TCGA) | AUC: 0.745 (1-year), 0.745 (2-year), 0.719 (3-year OS) | Predicts outcome and correlates with immunity and activated oncogene pathways |

| Five-lncRNA Signature [7] | 5 lncRNAs (RP11-325L7.2, DKFZP434L187, RP11-100L22.4, DLX2-AS1, RP11-104L21.3) | 167 early-stage HCC samples | Risk score was an independent prognostic factor for HCC | Prognosis prediction in early-stage HCC |

| Four-lncRNA Machine Learning Model [1] | 4 lncRNAs (LINC00152, LINC00853, UCA1, GAS5) | 52 HCC patients and 30 controls | 100% sensitivity, 97% specificity for HCC diagnosis | Diagnostic tool when integrated with conventional laboratory data |

| Plasma Exosomal lncRNA-derived 6-Gene Signature [8] | 6 genes (G6PD, KIF20A, NDRG1, ADH1C, RECQL4, MCM4) | 230 plasma exosomes and 831 HCC tissues | High prognostic accuracy in random survival forest model | Molecular subtyping, prognostic stratification, treatment response prediction |

| Four-lncRNA Prognostic Model [9] | 4 lncRNAs (DDX11-AS1, ZFPM2-AS1, AC016717.2, LINC00462) | 342 HCC patients (TCGA) | Reliably stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups (P<0.05) | Survival prediction based on risk score |

The integration of machine learning approaches with lncRNA biomarker analysis has enhanced the precision of prognostic stratification in HCC. One study demonstrated that a machine learning model integrating four lncRNAs (LINC00152, LINC00853, UCA1, and GAS5) with conventional laboratory parameters achieved 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity for HCC diagnosis, significantly outperforming individual lncRNAs which showed moderate diagnostic accuracy with sensitivity and specificity ranging from 60-83% and 53-67%, respectively [1]. This highlights the power of computational approaches to leverage lncRNA biomarkers for clinical application.

Ferroptosis-related lncRNA signatures represent a particularly innovative approach, leveraging the central role of ferroptosis in HCC development. One study established a prognostic signature comprising seven ferroptosis-related lncRNAs that effectively classified patients into low-risk and high-risk groups with significantly different prognosis [5]. The time-dependent receiver operating characteristic analysis yielded area under the curve values of 0.745, 0.745, and 0.719 for 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival, respectively, demonstrating robust predictive accuracy. Importantly, this signature also correlated with immune cell infiltration and expression of immune checkpoint genes, providing insights into the tumor microenvironment and potential implications for immunotherapy response [5].

Plasma exosomal lncRNAs offer a promising non-invasive approach for HCC management. One comprehensive study integrated transcriptomic data from 230 plasma exosomes and 831 HCC tissues to identify dysregulated plasma exosomal lncRNAs that form competitive endogenous RNA networks regulating 61 exosome-related genes [8]. Using unsupervised consensus clustering based on exosome-related gene expression profiles, HCC patients were stratified into three molecular subtypes with distinct survival outcomes, tumor microenvironments, and pathway activities. A subsequent random survival forest-derived 6-gene risk score demonstrated high prognostic accuracy and predicted differential treatment responses, with low-risk patients showing superior anti-PD-1 immunotherapy responses while high-risk patients exhibited increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and sorafenib [8].

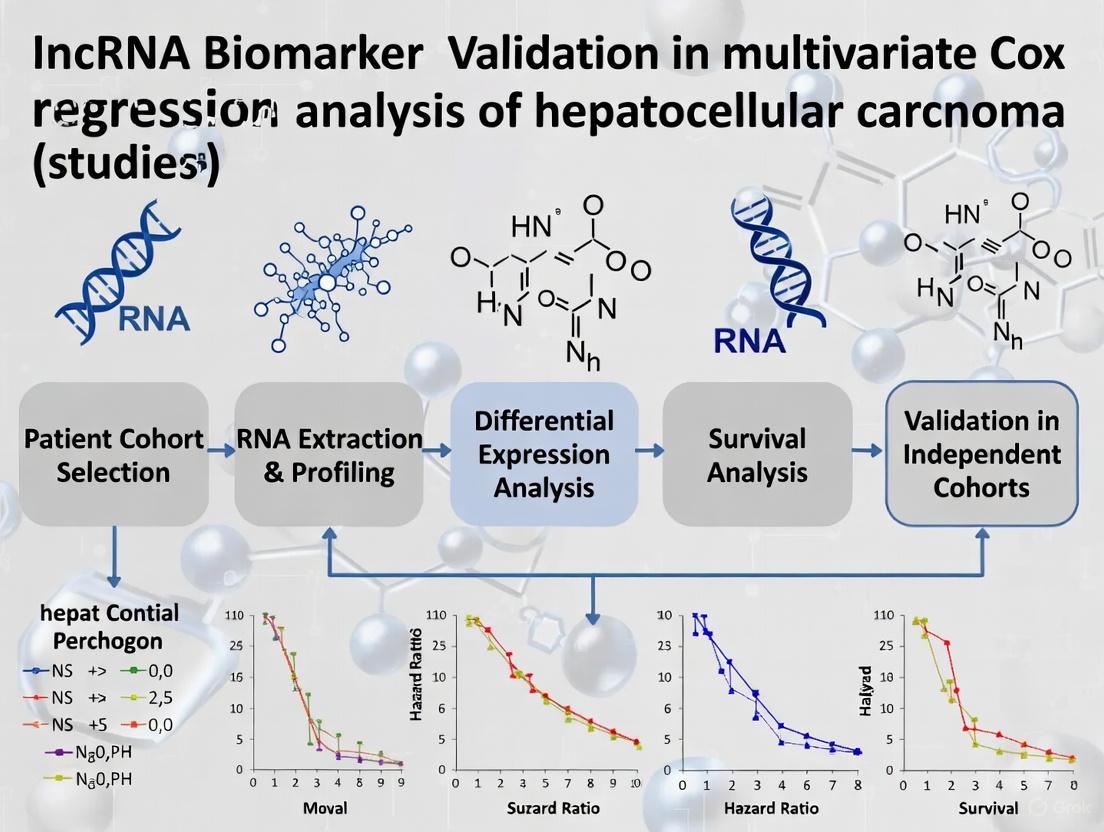

Figure 2: Workflow for Developing lncRNA-Based Prognostic Signatures in HCC. The standardized approach involves lncRNA profiling from patient samples, statistical analysis to identify prognostic candidates, signature construction using rigorous regression methods, risk model development, and validation in independent cohorts before clinical application.

Experimental Methodologies: Protocols for lncRNA Functional Characterization

The functional characterization of lncRNAs in HCC relies on standardized experimental protocols that validate their biological roles and clinical utility. These methodologies encompass approaches for lncRNA detection, quantification, functional manipulation, and mechanistic investigation.

lncRNA Detection and Quantification

Accurate measurement of lncRNA expression represents the foundation of HCC lncRNA research. The predominant methodology involves RNA isolation followed by reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR. One study protocol detailed RNA isolation using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol, followed by reverse transcription into complementary DNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) on a T100 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) [1]. Quantitative real-time PCR was then performed using the PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems) on a ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), with the housekeeping gene GAPDH used for normalization of expression data [1]. Each reaction was typically performed in triplicate to ensure technical reproducibility, with the ΔΔCT method used for relative quantification and data analysis.

For large-scale lncRNA profiling, RNA sequencing represents the gold standard. Studies utilizing The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data typically process RNA-seq data downloaded as raw counts transformed to Transcripts Per Million values, followed by log2 transformation [8]. For microarray data from repositories such as GEO, data are used as provided by the authors after log2 transformation and quantile normalization [8]. Differential expression analysis typically employs packages such as DEseq and edgeR in R, with thresholds set at false discovery rate <0.05 and |log(fold change)|>1.3 [7].

Functional Validation Experiments

Functional characterization of candidate lncRNAs typically involves gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies in HCC cell lines. For instance, the oncogenic role of LINC01063 was validated through knockdown experiments that inhibited cell proliferation, disrupted colony formation ability, and reduced migration and invasion capacities of HCC cells [5]. In vivo validation was performed using nude BALB/c mice injected with LINC01063-knockdown HCC cells, which exhibited reduced tumor growth compared to controls [5]. These complementary approaches provide compelling evidence for the functional significance of lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis.

The construction of competitive endogenous RNA networks represents a key methodology for elucidating lncRNA mechanistic actions. One comprehensive approach employed a multilevel strategy: first, miRNA binding sites of differentially expressed lncRNAs were predicted via the miRcode database; subsequently, the miRTarBase, TargetScan, and miRDB databases were integrated, retaining only miRNA-mRNA relationships supported by all three databases; finally, the intersection of target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs and upregulated mRNAs in HCC tissues was used to define exosome-related genes, and a ternary regulatory network was constructed via Cytoscape [8]. This rigorous approach minimizes false positives and enhances the biological relevance of predicted interactions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for lncRNA Studies in HCC

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) [1] | Total RNA extraction from tissues/cells | Preserves lncRNA integrity; removes contaminants |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) [1] | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Includes gDNA eraser; high efficiency for long transcripts |

| qPCR Master Mixes | PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) [1] | Quantitative real-time PCR detection | Optimized for lncRNA detection; high sensitivity |

| PCR Systems | ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) [1] | Real-time PCR amplification and detection | Multi-channel detection; high precision |

| Computational Tools | edgeR, DEseq [7] | Differential expression analysis | Handles count data; robust statistical framework |

| Pathway Analysis | clusterProfiler [8] | Functional enrichment analysis | GO/KEGG analysis; visualization capabilities |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape [8] [9] | Biological network construction and visualization | Interactive interface; extensive plugin ecosystem |

| Survival Analysis | survival package in R [7] [9] | Cox regression and survival analysis | Handles time-to-event data; multivariate analysis |

Statistical Analysis and Model Validation

Robust statistical analysis is essential for validating the prognostic value of lncRNA biomarkers. Multivariate Cox regression analysis represents the gold standard for establishing independent prognostic significance while controlling for clinical covariates. Studies typically employ the survival package in R for this purpose [7]. For prognostic model development, multiple machine learning algorithms are often integrated, including CoxBoost, stepwise Cox, Lasso, Ridge, elastic net, survival support vector machines, generalized boosted regression models, supervised principal components, partial least squares Cox, and random survival forest, typically within a 10-fold cross-validation framework [8].

Model performance is typically evaluated using the concordance index as the primary metric for prognostic models, with additional assessment via time-dependent receiver operating characteristic analysis calculating area under the curve values for 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival [5]. Risk scores are calculated using weighted formulae based on regression coefficients from multivariate Cox regression analysis, with patients subsequently stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on median risk score for survival comparison via Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test [9].

The comprehensive analysis of dysregulated lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis reveals a complex regulatory landscape with significant implications for clinical practice. The rigorous validation of both oncogenic and tumor-suppressor lncRNAs through multivariate Cox regression analyses provides a robust statistical foundation for their implementation as prognostic biomarkers. The development of multi-lncRNA signatures leveraging machine learning approaches demonstrates superior predictive accuracy compared to single lncRNA biomarkers, suggesting that combinatorial approaches may offer the most promising path toward clinical translation.

The therapeutic targeting of lncRNAs represents an emerging frontier in HCC management. Several strategies show promise, including the use of pHLIP-PNA to target solid tumors, with lncRNAs such as 91H, BCAR4, HULC, MALAT-1, TUG1, and UCA1 identified as oncogenic targets, while Loc285194 and MEG3 represent tumor suppressor candidates [4]. Advanced gene editing technologies such as TALEN or CRISPR/Cas9 methodologies are thought to enable detailed evaluation of lncRNA functions, potentially paving the way for therapeutic applications [4].

Future research directions should focus on validating lncRNA biomarkers in prospective clinical trials, standardizing detection methodologies for clinical implementation, and developing lncRNA-targeted therapeutics. The integration of lncRNA biomarkers with existing clinical parameters and imaging findings may facilitate personalized treatment approaches, ultimately improving the dismal survival statistics that currently characterize HCC. As our understanding of lncRNA biology in HCC continues to mature, these molecules hold exceptional promise for transforming the clinical management of this devastating malignancy.

Comparative Analysis of lncRNA Prognostic Models in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Across Key Biological Contexts

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a formidable global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most prevalent cancer and third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [10]. The disease often progresses asymptomatically in early stages, resulting in advanced presentation with limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis [10]. This clinical reality has driven extensive research into novel biomarkers for early detection, prognosis prediction, and treatment guidance. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), once considered "junk DNA," have emerged as crucial regulators of gene expression through transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and epigenetic mechanisms [10]. Their involvement in cancer initiation, progression, metastasis, immune escape, and drug resistance has positioned them as promising biomarkers and therapeutic targets [11].

The complex molecular landscape of HCC necessitates biomarker development within specific biological contexts that drive tumor progression. Key pathways including amino acid metabolism, ferroptosis, autophagy, and migrasome formation represent critical biological processes with distinct roles in hepatocarcinogenesis. Amino acids serve not only as building blocks for protein synthesis but also as key regulators of metabolic pathways and immune responses [12]. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of programmed cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation, offers promising avenues for combating drug-resistant tumors [13]. Autophagy, a cellular degradation pathway essential for maintaining homeostasis, plays dual roles in tumor suppression and promotion depending on context [14]. More recently discovered, migrasomes—organelles that form during cell migration—facilitate intercellular communication and influence tumor microenvironment dynamics [15].

This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of lncRNA-based prognostic signatures derived from these four key biological contexts in HCC. By examining their construction methodologies, predictive performance, and clinical applicability, we aim to guide researchers and clinicians in selecting appropriate biomarker approaches for specific research and therapeutic objectives.

Comparative Performance of Biological Context-Specific lncRNA Signatures

Table 1: Comparative performance of lncRNA prognostic models across biological contexts in HCC

| Biological Context | Key lncRNAs in Signature | Patient Cohort | Predictive Performance (AUC) | Clinical Utility | Immune Response Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Metabolism | 4-lncRNA signature (includes AL590681.1) | TCGA (n=340) | 1-year: ~0.753-year: ~0.725-year: NA | Prognostic stratification; enhanced cell activity confirmed functionally [10] | Correlates with immunosuppressive cell infiltration; anti-PD1 response prediction [10] |

| Migrasome Formation | LINC00839, MIR4435-2HG | TCGA (n=372) + external validation (n=100) | Consistent predictive accuracy across cohorts [11] | Prognostic stratification; promotes malignant behaviors and immune evasion [11] | Elevated immunosuppressive infiltration; immune checkpoint expression; ICI response prediction [11] |

| PANoptosis | Multiple lncRNAs (specific identities not highlighted) | TCGA + GEO databases | ROC and calibration curves confirm good predictive ability [16] | Prognostic stratification; distinguishes two molecular subtypes with different outcomes [16] | Cluster 1 subtype shows better prognosis and higher immune infiltration [16] |

| Ferroptosis | Not specifically developed in retrieved literature | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Table 2: Methodological approaches for lncRNA signature development across studies

| Development Phase | Amino Acid Metabolism Study [10] | Migrasome Formation Study [11] | PANoptosis Study [16] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Gene Set | 374 AAM-related genes from MSigDB | 12 migrasome-related genes (TSPAN4, NDST1, CPQ, ITGAV) from GeneCards and literature | PANoptosis-related genes from published studies |

| lncRNA Identification | Pearson correlation (∣R∣ > 0.4, p < 0.05) | Pearson correlation (∣R∣ > 0.55, p < 0.001) | Correlation analysis with PANoptosis genes |

| Prognostic Filtering | Univariate Cox (p < 0.05) → 24 lncRNAs | Univariate Cox (p < 0.05) → 16 lncRNAs | Not explicitly detailed |

| Signature Refinement | LASSO + Multivariate Cox → 4-lncRNA model | LASSO-Cox with 1000x 10-fold CV → 2-lncRNA model | Lasso-Cox regression analysis |

| Validation Approach | Internal TCGA split (1:1 training:validation) | Internal TCGA split + external clinical cohort (n=100) | Internal validation with ROC and calibration curves |

Biological Contexts: Mechanisms and lncRNA Integration

Amino Acid Metabolism in HCC

Amino acids serve fundamental roles in cellular physiology beyond protein synthesis, including energy production, maintenance of redox balance, and activation of key signaling pathways such as mTOR [12]. In cancer cells, reprogramming of amino acid metabolism supports rapid proliferation and adaptation to metabolic stress. The branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—leucine, isoleucine, and valine—deserve particular attention as they account for 35% of essential amino acids in muscle and activate mTOR signaling, thereby promoting protein synthesis [12]. In HCC, dysregulated BCAA metabolism has been associated with cancer progression through multiple mechanisms. Alterations in circulating BCAA levels have been reported in cancer patients, with increased levels associated with higher pancreatic cancer risk [12]. The specific lncRNA AL590681.1, identified in the AAM-related signature, was experimentally validated to enhance HCC cell activity, confirming the functional relevance of this metabolic axis in hepatocarcinogenesis [10].

Ferroptosis Regulation in Cancer

Ferroptosis represents a unique iron-dependent form of programmed cell death characterized by glutathione depletion, GPX4 inactivation, and accumulation of lipid peroxides [13]. Morphologically, it features mitochondrial shrinkage, reduced cristae, and membrane rupture without the classic hallmarks of apoptosis. The core regulatory axis involves system Xc--mediated cystine uptake, glutathione synthesis, and GPX4 activity, which collectively protect against lethal lipid peroxidation [13]. Cancer cells with mesenchymal characteristics demonstrate particular vulnerability to ferroptosis induction due to their elevated polyunsaturated fatty acid incorporation into membrane phospholipids [13]. While the retrieved literature does not describe a specific ferroptosis-related lncRNA signature for HCC, the molecular machinery of ferroptosis offers rich opportunities for biomarker development, particularly given its established role in overcoming chemotherapy resistance in various cancers.

Autophagy in Cellular Stress Response

Autophagy constitutes an essential cellular degradation pathway that maintains homeostasis by recycling damaged organelles and proteins through lysosomal degradation [14]. This process becomes particularly crucial during metabolic stress, such as glucose starvation, where it helps sustain cellular energy production and survival. Recent research has elucidated that glucose starvation-induced autophagy involves distinct mechanisms compared to classic amino acid starvation-induced autophagy, with mitochondrial function playing a central regulatory role [14]. The Mec1-Atg9 phosphorylation axis has been identified as specifically required for energy stress-induced autophagy but not nitrogen starvation-induced autophagy, highlighting the pathway-specific nature of autophagy regulation [14]. While autophagy plays complex, context-dependent roles in cancer—sometimes suppressing and sometimes promoting tumor growth—its modulation represents a promising therapeutic avenue in HCC.

Migrasome Formation and Function

Migrasomes constitute a newly discovered class of extracellular vesicles that form during cell migration at the ends of retraction fibers [15]. These organelles facilitate long-distance communication by transporting various cargo molecules including proteins, lipids, and genetic material. Recent research has illuminated the intricate process of migrasome biogenesis, revealing that tubular endoplasmic reticulum extends through retraction fibers and incorporates into migrasomes through membrane contact sites, delivering cholesterol and calcium ions that promote migrasome growth, stability, and secretion [17]. In HCC, migrasome-related genes have been implicated in promoting invasion, metastasis, and immune evasion [11]. The functional validation of MIR4435-2HG from the migrasome-related lncRNA signature demonstrated its role in promoting proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and PD-L1-mediated immune evasion, establishing a direct connection between migrasome biology and HCC progression [11].

Experimental Protocols for lncRNA Biomarker Development

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The development of context-specific lncRNA signatures follows a consistent bioinformatics workflow. Initial data acquisition typically involves retrieving HCC transcriptome data from TCGA-LIHC and normalizing expression values to transcripts per million [11]. For context-specific lncRNA identification, researchers first compile relevant gene sets—374 amino acid metabolism genes from MSigDB [10] or 12 migrasome-related genes from GeneCards and literature [11]. Pearson correlation analysis then identifies lncRNAs significantly co-expressed with these gene sets, with thresholds varying by study (∣R∣ > 0.4 [10] or ∣R∣ > 0.55 [11]). Prognostic filtration via univariate Cox regression identifies survival-associated lncRNAs, followed by dimensionality reduction using LASSO-Cox regression to construct the final multimarker signature [10] [11]. Model validation employs internal cohort splitting (typically 1:1 training:validation) and, in robust studies, external clinical cohorts [11]. Performance evaluation includes Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, time-dependent ROC curves, and calibration plots [10] [16].

Functional Validation Approaches

Table 3: Experimental methods for functional validation of prognostic lncRNAs

| Experimental Method | Key Reagents | Experimental Output | Application in HCC lncRNA Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockdown | Lipofectamine 3000, specific shRNA/siRNA [10] [11] | Knockdown efficiency (RT-qPCR), phenotypic changes | Confirm role of AL590681.1 in HCC cell activity [10] and MIR4435-2HG in malignant behaviors [11] |

| Proliferation Assays | CCK-8 reagent, colony formation staining [10] | Cell viability, colony formation capacity | Assess impact of lncRNA modulation on HCC growth [10] |

| Gene Expression Analysis | RT-qPCR, specific primers [10] | Expression levels across cell lines | Determine AL590681.1 expression in various HCC cell lines [10] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Single-cell RNA sequencing platforms | Cell type-specific expression patterns | Identify MIR4435-2HG enrichment in cancer-associated fibroblasts [11] |

Figure 1: Bioinformatics workflow for developing context-specific lncRNA signatures in HCC

Research Reagent Solutions for lncRNA Studies

Table 4: Essential research reagents for experimental validation of lncRNA biomarkers

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfection Reagents | Lipofectamine 3000 [10] [11] | lncRNA knockdown/overexpression | High efficiency, low cytotoxicity |

| Cell Culture Media | DMEM with 10% FBS [10] | HCC cell line maintenance | Standardized growth conditions |

| Detection Assays | CCK-8 assay [10] | Cell proliferation measurement | Sensitive, reproducible viability readout |

| RNA Analysis Tools | RT-qPCR reagents, specific primers [10] | lncRNA expression quantification | High specificity and sensitivity |

| Cell Lines | Hep-3B, Huh-1, Huh-7, HCCLM3 [10] | Functional validation studies | Represent HCC molecular heterogeneity |

This comprehensive analysis of lncRNA-based prognostic models across four key biological contexts reveals both the promises and challenges in translating these findings to clinical practice. The migrasome-related and amino acid metabolism-related signatures currently represent the most advanced approaches, with robust validation and demonstrated functional relevance to HCC pathogenesis. The migrasome-related model particularly stands out for its external validation and detailed mechanistic insights into immune evasion [11], while the amino acid metabolism signature benefits from the fundamental role of metabolic reprogramming in cancer [10] [12].

The absence of a well-developed ferroptosis-related lncRNA signature in the current literature represents a significant gap, given the established importance of ferroptosis in overcoming chemotherapy resistance [13]. Similarly, while autophagy plays crucial roles in HCC progression and treatment response [14], autophagy-focused lncRNA signatures remain underdeveloped. These gaps present valuable opportunities for future research.

For researchers and clinicians, selection of appropriate lncRNA biomarkers should consider specific clinical contexts and therapeutic intentions. The migrasome-related signature shows particular promise for immunotherapy guidance, while amino acid metabolism-related signatures may better inform metabolic targeting approaches. Future directions should focus on integrating multiple biological contexts into unified models, expanding external validation across diverse patient cohorts, and advancing functional studies to establish causal rather than correlative relationships between lncRNAs and HCC progression.

Systematic Identification of Candidate lncRNAs from Public Databases (e.g., TCGA-LIHC)

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a global health challenge with high mortality rates, largely due to late diagnosis and limited prognostic tools [18]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), once considered "transcriptional noise," have emerged as crucial regulators of diverse cellular processes and promising biomarkers for cancer prognosis [18]. Public databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (TCGA-LIHC) repository provide extensive genomic datasets that enable researchers to systematically identify lncRNA signatures associated with HCC prognosis [19]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various computational and experimental approaches for lncRNA biomarker discovery within the context of multivariate Cox regression studies in HCC research.

Performance Comparison of Established lncRNA Signatures

Multiple research groups have developed different lncRNA signatures from TCGA-LIHC data, each demonstrating varying prognostic capabilities. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of four prominent signatures:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of lncRNA Signatures from TCGA-LIHC

| Study & Signature Type | Number of lncRNAs | Validation Cohort | AUC (1/3/5-year) | Key lncRNAs Identified | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-lncRNA prognostic signature [19] | 11 | External GEO (n=203) | Up to 0.846 | GACAT3, AC010547.1, LINC01747 | 3.648 (2.238-5.945) |

| Costimulatory molecule-related 5-lncRNA signature [20] | 5 | Internal TCGA split | 0.735/0.706/0.742 (testing) | AC099850.3, BOK-AS1, NRAV | 2.78 (1.62-4.79) |

| 4-lncRNA early recurrence signature [21] | 4 | External cohort (n=24) | N/A (focused on recurrence) | AC108463.1, AF131217.1, TMCC1-AS1 | N/A |

| Migrasome-related 2-lncRNA signature [11] | 2 | Independent clinical cohort (n=100) | N/A | LINC00839, MIR4435-2HG | N/A |

The performance variation across these signatures highlights several critical aspects of lncRNA biomarker development. The 11-lncRNA signature demonstrated exceptional predictive power with an AUC reaching 0.846, suggesting high diagnostic accuracy [19]. Signatures derived from biologically relevant contexts, such as costimulatory molecules or migrasomes, show particular promise for understanding functional mechanisms in HCC progression [11] [20].

Table 2: Functional Validation Approaches for Candidate lncRNAs

| Functional Assay | Experimental Readout | Key Findings for Specific lncRNAs |

|---|---|---|

| CCK-8 and colony formation [19] [20] | Cell proliferation capacity | Silencing GACAT3 and AC099850.3 suppressed HCC cell proliferation |

| Transwell invasion and migration [19] | Metastatic potential | GACAT3 knockdown inhibited HCC cell invasion and migration |

| Quantitative RT-PCR [19] [1] | Expression levels in tissues/cell lines | GACAT3 highly expressed in HCC tissues; MIR4435-2HG associated with poor prognosis |

| Immune cell infiltration analysis [11] [21] | Tumor microenvironment composition | High-risk groups showed immunosuppressive cell infiltration and checkpoint expression |

Experimental Protocols for lncRNA Identification and Validation

Computational Identification from Public Databases

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Source HCC RNA-seq data and clinical information from TCGA-LIHC portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) [19] [22]

- Normalize expression data to transcripts per million (TPM) or fragments per kilobase million (FPKM)

- Filter patients for complete clinical information, excluding those with survival <30 days [20]

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Identify differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) using "edgeR," "DESeq2," or "limma" R packages [19] [21]

- Apply thresholds of |log2 fold change| >2.0 and adjusted p-value <0.05 [19]

- For specialized signatures, perform co-expression analysis with relevant gene sets (e.g., migrasome-related genes, costimulatory molecules) using Pearson correlation (|r|>0.4-0.55, p<0.001) [11] [20]

Prognostic Model Construction:

- Conduct univariate Cox regression to identify OS-associated lncRNAs (p<0.05) [19]

- Apply machine learning algorithms: LASSO Cox regression with 10-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting [19] [11] [21]

- Calculate risk score using the formula: Risk score = Σ(coefficientlncRNA × expressionlncRNA) [11]

- Validate signatures in internal testing sets and external cohorts (GEO, independent clinical samples) [19] [11]

Figure 1: Computational workflow for lncRNA signature identification from public databases.

Functional Validation of Candidate lncRNAs

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Maintain HCC cell lines (e.g., MHCC-97H, HepG2, LM3) in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [19]

- Perform lncRNA silencing using siRNA or shRNA transfection with appropriate controls

Phenotypic Assays:

- Cell proliferation: Conduct CCK-8 assays and colony formation assays [19] [20]

- Invasion and migration: Perform Transwell assays with or without Matrigel coating [19]

- Apoptosis analysis: Utilize flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining

Molecular Analyses:

- RNA isolation and qRT-PCR: Extract total RNA using TRIzol, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR with SYBR Green [19] [1]

- Pathway analysis: Conduct Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) on high- vs. low-risk groups [19]

Key Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

lncRNAs contribute to HCC progression through multiple interconnected signaling pathways and biological processes. The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms identified through functional studies:

Figure 2: Key mechanisms of lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis and prognosis.

The multifunctional roles of lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis include:

- Epigenetic regulation: Nuclear lncRNAs (e.g., HOTAIR) recruit chromatin-modifying enzymes to specific genomic loci, mediating DNA methylation and histone modifications [18]

- Post-transcriptional control: Cytoplasmic lncRNAs function as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or miRNA sponges, affecting mRNA stability and translation [18]

- Immune modulation: Specific lncRNAs (e.g., MIR4435-2HG) promote immune evasion by regulating PD-L1 expression and establishing an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [11]

- Cell fate determination: lncRNAs influence key processes including proliferation (AC099850.3), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (GACAT3), and apoptosis [19] [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Databases

Table 3: Essential Resources for lncRNA Biomarker Discovery and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Databases | TCGA-LIHC [19] [22] | Genomic data repository | Clinical annotation, multi-omics data |

| GEO/SRA [19] [22] | Gene expression repository | Diverse studies, raw sequencing data | |

| GTEx [22] | Normal tissue reference | Tissue-specific expression patterns | |

| lncRNADisease v2.0/v3.0 [23] | LncRNA-disease associations | Experimentally validated interactions | |

| Computational Tools | "edgeR," "DESeq2," "limma" [19] [21] | Differential expression | Statistical analysis of RNA-seq data |

| "glmnet" (LASSO) [19] [11] | Feature selection | Regularized regression for biomarker selection | |

| "survival" R package [19] | Survival analysis | Cox regression, Kaplan-Meier curves | |

| GSEA software [19] | Pathway analysis | Biological mechanism exploration | |

| Experimental Reagents | HCC cell lines [19] | Functional validation | In vitro models (MHCC-97H, HepG2, LM3) |

| siRNA/shRNA [19] | Gene silencing | lncRNA knockdown studies | |

| qRT-PCR reagents [19] [1] | Expression validation | SYBR Green, target-specific primers | |

| Transwell assays [19] | Migration/invasion | Metastatic potential assessment | |

| Bombinin H-BO1 | Bombinin H-BO1, MF:C76H137N19O17, MW:1589.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Elemicin-d3 | Elemicin-d3, MF:C12H16O3, MW:211.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Systematic identification of candidate lncRNAs from public databases like TCGA-LIHC has established robust prognostic signatures for hepatocellular carcinoma. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that multivariate Cox regression models incorporating lncRNA expression data significantly enhance prognostic stratification beyond conventional clinical parameters. Future directions should focus on standardizing analytical pipelines, incorporating single-cell RNA-seq data for cellular resolution, and advancing functional studies to elucidate the mechanistic roles of candidate lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis. The integration of computational biomarker discovery with experimental validation represents a powerful paradigm for advancing personalized oncology and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Building a Robust Prognostic Model: From Statistical Analysis to Signature Development

In the field of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) research, the validation of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) biomarkers requires robust statistical workflows that can handle high-dimensional genomic data while ensuring model reliability and clinical interpretability. The integration of univariate screening, LASSO-penalized Cox regression, and multivariate Cox analysis has emerged as a powerful framework for identifying stable prognostic signatures from thousands of candidate lncRNAs. This comparative guide examines the performance, implementation, and practical application of these methodological approaches within the context of lncRNA biomarker validation for HCC prognosis and therapeutic development.

Methodological Comparison and Experimental Performance

Core Methodologies and Comparative Performance

The statistical workflow for lncRNA biomarker validation typically follows a sequential approach that balances variable screening intensity with model stability. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of each methodological stage based on recent HCC studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of statistical methods in lncRNA-HCC studies

| Methodological Stage | Key Characteristics | Typical Variable Reduction | Reported C-index (HCC Studies) | Primary Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Screening | Initial filter based on univariate Cox p-values or correlation coefficients | 80-95% reduction (e.g., 191 to 16 lncRNAs) [11] | 0.60-0.68 (alone) [11] | Computational efficiency; removes obvious noise | Ignores multivariate relationships; potential false negatives |

| LASSO-Cox Regression | L1-penalization with cross-validation; automated variable selection | 70-90% further reduction (e.g., 16 to 2-8 lncRNAs) [11] | 0.65-0.75 [24] [11] | Handles high-dimensional data; prevents overfitting; creates sparse models | May exclude correlated predictors; sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning |

| Multivariate Cox Regression | Final model refinement with selected variables | Fixed number of predictors (typically 2-10 lncRNAs) | 0.70-0.85 (in final models) [10] [11] | Provides interpretable hazard ratios; clinical familiarity | Requires limited predictors; assumes proportional hazards |

Experimental Data from Recent HCC Studies

Recent investigations applying this statistical workflow to lncRNA biomarker discovery in HCC demonstrate consistent patterns of performance:

A migrasome-related lncRNA study utilized this sequential approach, beginning with 191 candidate MRlncRNAs identified through correlation analysis. Univariate Cox screening reduced these to 16 significant candidates, with subsequent LASSO-Cox regression further refining the signature to just two lncRNAs (LINC00839 and MIR4435-2HG). The final multivariate Cox model achieved a C-index of 0.72 in the validation cohort, effectively stratifying patients into distinct prognostic groups (p < 0.001) [11].

An amino acid metabolism-related lncRNA study in HCC applied a similar workflow, identifying 24 prognostic AAM-related lncRNAs through univariate analysis before employing LASSO-Cox to develop a 4-lncRNA risk signature. The resulting model showed significant predictive power for overall survival (p < 0.001) and demonstrated clinical utility for immunotherapy response prediction [10].

Research on elderly glioma patients provided comparative data, showing that LASSO-Cox models with five variables demonstrated superior predictive performance (higher C-index) compared to full Cox models with four variables, highlighting the value of penalized regression even after initial variable screening [24].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized Workflow for lncRNA Biomarker Validation

The following diagram illustrates the complete statistical workflow for lncRNA biomarker development and validation in HCC studies, integrating the three methodological components:

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Univariate Screening Protocol

The initial screening phase focuses on reducing dimensionality while retaining potentially significant lncRNAs:

Expression Filtering: Begin with normalization of lncRNA expression data (typically TPM or FPKM) and removal of lowly expressed transcripts (e.g., those with zero counts in >80% of samples) [11].

Correlation Analysis: Calculate Pearson correlation coefficients between candidate lncRNAs and reference gene sets (e.g., migrasome-related genes, amino acid metabolism genes). Apply thresholds of |correlation coefficient| > 0.4-0.55 with p < 0.001 to identify biologically relevant lncRNAs [10] [11].

Univariate Cox Regression: Perform survival analysis for each candidate lncRNA using Cox proportional hazards models. Retain transcripts with p-values < 0.05 for further analysis. This typically reduces the candidate pool by 80-95% while preserving potentially significant predictors [11].

LASSO-Cox Regression Implementation

The LASSO-Cox regression provides the critical variable selection mechanism:

Parameter Tuning: Implement 10-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal penalty parameter (λ). Both λ.min (value that gives minimum mean cross-validated error) and λ.1se (most regularized model within one standard error of the minimum) are commonly used, with λ.1se preferred for more parsimonious models [25] [11].

Model Training: Fit the LASSO-Cox model using the remaining lncRNAs after univariate screening. The L1 penalty shrinks coefficients of less relevant variables to exactly zero, automatically performing variable selection. The optimization follows:

(\hat{\beta}(lasso) = \underset{\beta}{\text{argmax }} l(\beta) - \lambda || \beta ||_1)

where (l(\beta)) is the log-partial likelihood and (|| \beta ||_1) is the L1-norm penalty [26] [25].

Iteration and Stability: Repeat the LASSO procedure multiple times (e.g., 1000 iterations) with different random seeds to ensure selection stability. Retain only those lncRNAs consistently selected across iterations for the final model [11].

Multivariate Cox Model Development

The final stage refines the prognostic model:

Proportional Hazards Assumption: Verify the proportional hazards assumption for each selected lncRNA using Schoenfeld residuals before final model construction.

Model Optimization: Enter the LASSO-selected lncRNAs into a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model alongside key clinical variables (e.g., age, stage, tumor size) to adjust for potential confounders.

Risk Score Calculation: Compute individual risk scores using the formula:

(Riskscore = \sum{i} Coefficient{MRlncRNAsi} \times Expression{MRlncRNAs_i})

Stratify patients into high-risk and low-risk groups using the median risk score as cutoff [11].

Successful implementation of this statistical workflow requires both biological and computational resources. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in lncRNA biomarker validation for HCC.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for lncRNA biomarker validation

| Category | Specific Resource | Application in Workflow | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | TCGA-LIHC Database | Primary source of lncRNA expression and clinical data | Includes 372 LIHC tumors and 50 normal tissues; provides survival outcomes [10] [11] |

| Molecular Databases | GeneCards | Identification of reference gene sets (e.g., migrasome-related genes) | Provides comprehensive gene annotation; enables biological context [11] |

| Statistical Software | R Statistical Environment | Implementation of all statistical analyses | Essential packages: survival, glmnet, timeROC, caret [26] [11] |

| Specialized R Packages | glmnet | LASSO-Cox regression implementation | Handles high-dimensional data; efficient cross-validation [26] [25] |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2, survminer | Creation of publication-quality figures | Kaplan-Meier curves, ROC plots, risk stratification visualizations [10] [11] |

| Validation Tools | timeROC | Time-dependent ROC analysis | Evaluates prognostic accuracy at 1, 3, and 5 years [11] |

The integrated statistical workflow combining univariate screening, LASSO-Cox regression, and multivariate Cox analysis represents a robust methodology for lncRNA biomarker validation in HCC research. Experimental data from recent studies consistently demonstrates that this approach effectively handles high-dimensional genomic data while producing clinically interpretable prognostic signatures. The sequential application of these methods balances statistical rigor with practical implementation, enabling researchers to distill complex lncRNA expression patterns into stable, clinically relevant biomarkers. As HCC research continues to evolve toward more personalized therapeutic approaches, this statistical framework provides a validated foundation for translating lncRNA discoveries into meaningful prognostic tools and potential therapeutic targets.

Constructing Multi-lncRNA Prognostic Signatures and Calculating Risk Scores

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a significant global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality [10] [27]. The disease exhibits considerable genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity, making accurate prognosis prediction particularly challenging [28]. Traditional clinicopathological factors often provide insufficient prognostic information, driving the search for more precise molecular biomarkers. Within this context, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)—transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited protein-coding potential—have emerged as crucial regulators of gene expression and promising biomarker candidates [1] [3].

The construction of multi-lncRNA prognostic signatures represents a paradigm shift in HCC prognosis prediction, moving beyond single-marker approaches to integrated models that better reflect the molecular complexity of the disease. These signatures leverage the power of high-throughput sequencing technologies and sophisticated statistical methods to generate risk scores that stratify patients according to their clinical outcomes [29] [7]. This comparative guide examines the methodology, performance, and clinical applicability of various multi-lncRNA signatures currently advancing the field of HCC research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-lncRNA Prognostic Signatures

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Multi-lncRNA Prognostic Signatures in HCC

| Signature Focus | Specific lncRNAs Identified | Patient Cohort Size | Performance (AUC) | Key Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Response [28] | AC145207.5, POLH-AS1, AL928654.1, MKLN1-AS, AL031985.3, PRRT3-AS1, AC023157.2 | 369 HCC samples from TCGA | Not specified | Prognosis prediction, immune targeted therapy guidance |

| Cuproptosis-Related [30] | AL590705.3, SPRY4-AS1, AC135050.5, AL031985.3 | Not specified | 1-year: 0.715 | Prognosis prediction, immunotherapy response assessment |

| Amino Acid Metabolism [10] | 4-lncRNA signature (including AL590681.1) | 340 HCC samples (170 training/170 validation) | Not specified | Prognosis prediction, immunotherapy response, cell proliferation assessment |

| Five-lncRNA Signature [7] | RP11-325L7.2, DKFZP434L187, RP11-100L22.4, DLX2-AS1, RP11-104L21.3 | 167 early-stage HCC samples | Not specified | Early-stage prognosis prediction, understanding HCC development mechanisms |

| Disulfidptosis-Related [27] | AC016717.2, AC124798.1, AL031985.3 | 369 HCC cases (185 training/184 validation) | 1-year: 0.756, 3-year: 0.695, 5-year: 0.701 | Prognosis prediction, immune function analysis, drug sensitivity assessment |

Table 2: Analytical Comparison of Signature Performance and Clinical Value

| Signature Type | Statistical Strength | Biological Relevance | Therapeutic Guidance Potential | Validation Rigor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Response | Multivariate Cox regression with LASSO | Direct link to tumor microenvironment | High for immune-targeted therapies | Internal validation with TCGA data |

| Cuproptosis-Related | Superior to traditional clinical factors (age, gender, stage) | Connection to copper-induced cell death | Promising for immunotherapy selection | ROC analysis demonstrating outperformance of conventional factors |

| Amino Acid Metabolism | Significant risk stratification (p < 0.05) | Addresses metabolic reprogramming in cancer | Identified responders to anti-PD1 treatment | Experimental validation in HCC cell lines |

| Five-lncRNA Signature | Independent prognostic factor across subgroups | Multiple cancer pathways identified | Limited direct therapeutic guidance | Validation across age, sex, and alcohol consumption subgroups |

| Disulfidptosis-Related | Strong time-dependent ROC performance | Links novel cell death mechanism to HCC | Drug sensitivity predictions provided | Training and validation cohort approach |

Core Methodological Framework: From Data to Risk Score

The construction of multi-lncRNA prognostic signatures follows a systematic workflow that integrates bioinformatics, statistical modeling, and clinical validation. The standard methodology encompasses several critical phases that ensure the robustness and clinical applicability of the resulting risk scores.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The foundation of any robust lncRNA signature begins with comprehensive data acquisition. Researchers typically obtain RNA sequencing data and corresponding clinical information from large-scale repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (LIHC) dataset [28] [10] [7]. To ensure data quality, stringent preprocessing is applied, including the removal of samples with survival times of less than 30 days to avoid perioperative mortality bias [10] [31]. The remaining samples are typically randomly divided into training and validation cohorts, often in a 1:1 ratio, to enable internal validation of the derived signature [10] [27].

Identification of Relevant lncRNAs

The identification of biologically relevant lncRNAs represents a critical step in signature development. Two primary approaches dominate current methodologies:

Pathway-focused identification links lncRNAs to specific biological processes by retrieving relevant gene sets from databases such as the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [28] [10]. For example, in developing an inflammatory response-related signature, researchers identified 154 inflammatory response-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between HCC and noncancerous liver tissues (36 upregulated and 118 downregulated) [28]. Similarly, amino acid metabolism-related signatures began with 374 genes associated with amino acid metabolism pathways [10].

Correlation-based filtering applies Pearson correlation analysis to identify lncRNAs significantly correlated with the target genes. Standard thresholds include |correlation coefficient| > 0.4-0.5 with statistical significance of P < 0.05 [28] [10] [27]. This process typically identifies hundreds to thousands of candidate lncRNAs, which are subsequently refined through differential expression analysis comparing tumor versus normal tissues or poor versus good prognosis samples [7].

Signature Construction and Risk Score Calculation

The core analytical phase employs sophisticated statistical approaches to distill the candidate lncRNAs into a focused prognostic signature:

Univariate Cox regression analysis serves as the initial filter, identifying lncRNAs significantly associated with overall survival (OS) or recurrence-free survival (RFS) at a significance threshold of typically P < 0.05 [28] [7]. This step might identify dozens of potentially significant lncRNAs—for instance, 62 inflammatory response-related lncRNAs were identified in one study [28].

LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression addresses the risk of overfitting by penalizing the magnitude of coefficients, effectively reducing the number of lncRNAs in the signature while preserving the most prognostically relevant ones [28] [30] [32].

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression finally establishes the independent prognostic value of each selected lncRNA, generating weighted coefficients that reflect their relative contribution to the prognostic model [28] [7] [27].

The risk score formula represents the culmination of this analytical process, taking the form of a linear combination: [ \text{Risk Score} = \sum{i=1}^{n} (\text{coefficient}i \times \text{expression level of lncRNA}_i) ] where ( n ) represents the number of lncRNAs in the final signature, typically ranging from 3-9 lncRNAs [28] [30] [27]. Patients are then stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score for subsequent survival analysis and clinical correlation studies.

Experimental Validation and Functional Analysis

Assessment of Prognostic Performance

Rigorous validation constitutes an essential component of signature development, employing multiple analytical approaches to assess prognostic performance:

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis consistently demonstrates significant separation between high-risk and low-risk groups across multiple studies, with high-risk patients exhibiting poorer overall survival (p < 0.05) [28] [30] [10]. For example, the disulfidptosis-related lncRNA signature showed clear stratification, with high-risk patients experiencing significantly worse survival outcomes [27].

Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis quantifies the predictive accuracy of the risk scores at clinically relevant timepoints. The disulfidptosis-related signature achieved AUCs of 0.756, 0.695, and 0.701 for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, respectively [27]. Similarly, the cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature demonstrated an AUC of 0.715 for overall survival, outperforming traditional clinical factors such as age (AUC=0.531), gender (AUC=0.509), and stage (AUC=0.671) [30].

Decision curve analysis (DCA) provides clinical utility assessment by quantifying the net benefits of using the lncRNA signatures for prognostic decision-making compared to traditional approaches [28].

Exploration of Biological Mechanisms and Immune Microenvironment

Advanced bioinformatic analyses elucidate the potential biological mechanisms underlying the prognostic signatures:

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) identifies signaling pathways preferentially enriched in high-risk versus low-risk groups. For inflammatory response-related signatures, pathways including the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, focal adhesion, TNF signaling pathway, and NF-kappa B signaling pathway were significantly enriched [28]. Similarly, amino acid metabolism-related signatures revealed expected enrichments in metabolic pathways alongside cancer-related pathways [10].

Immune microenvironment analysis leverages algorithms such as CIBERSORT, QUANTISEQ, MCPCOUNTER, XCELL, EPIC, and TIMER to quantify immune cell infiltration [28] [10]. Studies consistently reveal distinct immune profiles between risk groups, with high-risk patients typically exhibiting increased immunosuppressive cell populations and altered immune function. For instance, the inflammatory response-related signature identified significant differences in cytolytic activity, MHC class I, type I INF response, type II INF response, inflammation-promoting, and T cell coinhibition between risk groups [28].

Immune checkpoint analysis demonstrates clinical relevance by revealing differential expression of checkpoint molecules between risk groups. High-risk patients in the inflammatory response-related signature study showed elevated expression of HHLA2, NRP1, CD276, TNFRSF9, TNFSF4, CD80, and VTCN1, suggesting potential responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors [28].

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for lncRNA Signature Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | TCGA-LIHC, ICGC-LIRI-JP | Provide transcriptomic and clinical data | Annotated HCC cohorts with survival data |

| Pathway Databases | Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) | Curated gene sets for biological pathways | Pathway-specific gene collections |

| Analytical Tools | R packages: limma, survival, survminer, GSVA, clusterProfiler | Statistical analysis and visualization | Specialized packages for bioinformatic analysis |

| Experimental Validation | miRNeasy Mini Kit, RevertAid cDNA Synthesis Kit, PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix | lncRNA quantification from patient samples | RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, qRT-PCR |

| Cell Line Models | THLE2, Hep-3B, Huh-1, Huh-7, HCCLM3 | Functional validation of signature lncRNAs | Representative HCC and normal liver cells |

Pathway Integration and Biological Significance

The biological relevance of multi-lncRNA signatures extends beyond statistical association to encompass direct involvement in critical cancer pathways. The diagram below illustrates how different lncRNA classes interface with key hepatocellular carcinoma processes:

The development of multi-lncRNA prognostic signatures represents a significant advancement in hepatocellular carcinoma management, offering superior prognostic stratification compared to conventional clinical parameters. These signatures successfully integrate complex biological pathways—including inflammatory response, cuproptosis, amino acid metabolism, and disulfidptosis—into clinically applicable risk scores that inform both prognosis and therapeutic selection.

The consistent methodological framework underlying these signatures, combining high-throughput data analysis with rigorous statistical modeling, ensures robust performance across diverse patient populations. Furthermore, the ability of these signatures to reflect the tumor immune microenvironment positions them as valuable tools for guiding immunotherapy decisions in an era of increasing personalized medicine.

As validation efforts expand and functional characterization deepens, multi-lncRNA signatures are poised to transition from research tools to clinical applications, ultimately fulfilling their potential to improve risk stratification, treatment selection, and clinical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma patients worldwide.

In the field of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) research, the validation of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) biomarkers relies on robust statistical methods to assess their prognostic performance. Among these, Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis and time-dependent Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves serve as fundamental tools for evaluating the ability of biomarkers to stratify patient risk and predict survival outcomes. While KM analysis visually represents survival probability differences between groups over time, time-dependent ROC curves provide a dynamic measure of a biomarker's discriminatory accuracy at specific clinical follow-up points. These methodologies are particularly crucial in lncRNA biomarker studies where researchers aim to translate molecular signatures into clinically applicable prognostic tools. This guide provides an objective comparison of methodological approaches and software implementations for these analytical techniques within the context of multivariate Cox regression studies in HCC research.

Analytical Framework for lncRNA Biomarker Validation

Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis in HCC lncRNA Studies

Kaplan-Meier estimation is a non-parametric statistic used to estimate survival functions from time-to-event data, commonly employed to visualize differences in survival outcomes between patient groups stratified by lncRNA expression levels. In typical HCC biomarker studies, patients are categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups based on lncRNA expression thresholds, and KM curves are generated to compare overall survival (OS) or recurrence-free survival (RFS) between these groups. The statistical significance of observed differences is typically assessed using the log-rank test.

The accuracy of KM analysis depends heavily on proper methodology implementation. Recent methodological research has demonstrated that reconstructed individual-level patient data (IPD) from published KM curves can generate hazard ratio (HR) estimates with a high degree of similarity to originally reported values, with mean absolute percentage differences of approximately 2.85% [33]. This approach is particularly valuable for meta-analyses when original datasets are inaccessible.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Kaplan-Meier Analysis in HCC lncRNA Studies

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in HCC Context | Typical Values in lncRNA Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | Ratio of hazard rates between groups | Measure of effect size for lncRNA biomarker | Values >1 indicate increased risk with high lncRNA expression [3] |

| Log-rank P-value | Significance of survival difference | Statistical significance of lncRNA stratification | P < 0.05 considered significant [27] [11] |

| Median Survival | Time until 50% of group experiences event | Clinical relevance of risk stratification | Often reported separately for high/low risk groups [11] |

| Censoring Rate | Proportion of patients with incomplete follow-up | Data completeness indicator | Varies by study; affects statistical power |

Time-Dependent ROC Curve Methodology

Traditional ROC analysis evaluates diagnostic accuracy at a single time point, but this approach is insufficient for survival data where disease status changes over time. Time-dependent ROC curves address this limitation by evaluating a marker's classification accuracy at specific time points during follow-up [34]. Three primary definitions exist for time-dependent sensitivity and specificity:

- Cumulative/Dynamic (C/D): Cases are defined as individuals experiencing the event before time t, while controls are those event-free at time t [34]. This approach is most clinically intuitive for determining prognosis at a specific time point.

- Incident/Dynamic (I/D): Cases are defined as individuals with an event at exactly time t, while controls are those event-free at time t [34]. This method is more appropriate for evaluating early detection capabilities.

- Incident/Static (I/S): Cases are individuals with an event at time t, while controls are a fixed set of individuals who remain event-free throughout the study [34].

For HCC studies with lncRNA biomarkers, the C/D approach is most commonly employed as it aligns with clinical decision-making at specific time horizons (e.g., 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival) [34].

Table 2: Time-Dependent ROC Curve Definitions and Applications

| Definition Type | Case Definition | Control Definition | Appropriate Use Cases in HCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative/Dynamic (C/D) | T ≤ t | T > t | Prognostic assessment at fixed time points (1, 3, 5 years) |

| Incident/Dynamic (I/D) | T = t | T > t | Early detection capability evaluation |

| Incident/Static (I/S) | T = t | T > t* for all t* | Fixed control group comparisons |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: IPD Reconstruction from Published KM Curves

The reconstruction of individual-level survival data from published KM curves enables validation and meta-analysis of lncRNA biomarkers in HCC research. This process involves two critical steps [33]:

- Digitization Step: Extract coordinates from KM survival curve images using specialized software. Tools such as CurveSnap, ScanIt, or the R Shiny application IPDfromKM can be employed for this purpose. To ensure accuracy: preprocess images to eliminate unwanted regions, draw two guidelines parallel to the axes to specify coordinate information, and use semi-automated or automated programs to reduce noise and errors [33].

- Reconstruction Step: Apply an iterative algorithm to generate IPD from the extracted coordinates. The algorithm proposed by Guyot et al. and enhanced by Liu et al. is recommended. This algorithm requires the number of patients at risk at different time points and the corresponding time points as reported in the published paper to ensure accurate reconstruction. The IPDfromKM R package automatically adjusts coordinates to maintain the non-increasing trend of KM survival curves over time [33].

Validation studies using this methodology have demonstrated reconstructed hazard ratios with less than 5% difference from originally reported values in most cases, confirming the reliability of this approach for secondary analyses and meta-analyses [33].

Protocol 2: Time-Dependent ROC Analysis for lncRNA Biomarkers

Implementing time-dependent ROC analysis for lncRNA biomarkers in HCC involves the following workflow [34]:

- Data Preparation: Organize dataset with time-to-event (overall survival or recurrence-free survival), event indicator (censoring status), and lncRNA expression values (often as a continuous risk score derived from a multivariate model).

- Time Point Selection: Identify clinically relevant time points for evaluation (typically 1, 3, and 5 years based on HCC clinical guidelines).

- Method Selection: Choose the appropriate time-dependent ROC definition (C/D recommended for prognostic assessment in HCC).

- Estimation Procedure: Calculate time-dependent sensitivity and specificity using inverse probability of censoring weights (IPCW) or cumulative sensitivity/dynamic specificity approaches.

- AUC Calculation: Compute the area under the time-dependent ROC curve at each selected time point using non-parametric or semi-parametric estimators.

- Visualization: Plot ROC curves at each time point and create AUC-over-time graphs to visualize discriminatory performance trends.

This protocol allows researchers to quantify how the prognostic accuracy of lncRNA biomarkers evolves throughout the disease course, providing insights beyond single-time-point assessments.

Software Comparison for Analysis Implementation

Kaplan-Meier Analysis Software Tools

Several software platforms support Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with varying capabilities:

Table 3: Software Solutions for Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis

| Software | Key Features | KM Curve Digitization | IPD Reconstruction | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R Survival Package | Comprehensive survival analysis, log-rank tests, multivariate Cox models | No | Through IPDfromKM package [33] | Open source |

| IPDfromKM R Package | Specialized in reconstructing IPD from KM curves, automatic coordinate modification | Yes | Yes, primary function [33] | Open source |

| MedCalc | User-friendly interface, log-rank tests, hazard ratio calculations | No | No | Commercial |

| NCSS | Complete survival analysis module, multiple comparison tests | No | No | Commercial |

ROC Analysis Software Comparison

Various software tools offer ROC analysis capabilities with different strengths for time-dependent applications:

Table 4: Software Solutions for ROC Curve Analysis

| Software | Time-Dependent ROC | AUC Comparison | Clinical Utility Features | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R timeROC Package | Yes, comprehensive implementations | DeLong method, bootstrapping | Limited | Open source |

| MedCalc | Limited | DeLong et al. method, Hanley & McNeil | Cost analysis, optimal threshold determination [35] | Commercial |

| NCSS | Limited | DeLong et al., Hanley & McNeil | Partial AUC, multiple curve comparisons [36] | Commercial |

| XLSTAT | No | DeLong, Hanley & McNeil, Sen | Decision plots, cost analysis [37] | Commercial |