Intrinsically Disordered Protein Binding: From Molecular Mechanisms to AI-Driven Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the molecular interactions governing intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) and region (IDR) binding.

Intrinsically Disordered Protein Binding: From Molecular Mechanisms to AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the molecular interactions governing intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) and region (IDR) binding. It explores the fundamental biophysical principles that distinguish IDPs from structured proteins and details the 'folding upon binding' mechanisms, including conformational selection and induced fit. The content covers cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for studying and targeting IDPs, with a special focus on recent breakthroughs in AI-based binder design, such as RFdiffusion and the 'logos' strategy. It also addresses the significant challenges in characterizing these dynamic systems and validates various approaches through comparative analysis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes foundational knowledge with the latest advances, highlighting the immense potential of IDP-targeting strategies for diagnosing and treating diseases like cancer, diabetes, and neurodegeneration.

Defining Disorder: The Sequence-Ensemble-Function Paradigm of IDPs

For decades, the central dogma of structural biology has maintained that a protein's amino acid sequence determines a specific three-dimensional structure, which in turn defines its function—a concept often likened to a lock-and-key mechanism [1]. However, the discovery that a substantial portion of the proteome consists of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) has fundamentally challenged this foundational principle [2]. These proteins lack a stable three-dimensional structure under physiological conditions yet remain fully functional, representing a profound contradiction to the established structure-function paradigm [1].

IDPs and IDRs are not rare exceptions but rather constitute approximately 30-40% of the eukaryotic proteome, with some estimates reaching as high as 60% when considering partial disorder [3] [2]. Their conformational malleability enables functional promiscuity that provides cells with multiplexed and flexible recognition and response systems [2]. Unlike their structured counterparts, IDPs exist as dynamic ensembles of rapidly interconverting structures, sampling a broad distribution of conformations rather than occupying a single stable state [4] [5]. This inherent flexibility allows IDPs to perform highly specialized functions that cannot be accomplished by globular proteins, particularly in regulatory processes such as cell signaling, transcriptional regulation, and molecular recognition [6] [7].

The study of IDPs has necessitated a reformulation of the traditional sequence-structure-function relationship to a sequence-ensemble-function paradigm, where the ensemble denotes the collection of states that a protein exists in at any given time [2]. This shift in perspective has profound implications for our understanding of cellular biology and presents new opportunities for therapeutic intervention, particularly for diseases linked to protein misfunction and aggregation [4] [1].

The Functional Repertoire of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Biological Roles and Molecular Recognition

The functional repertoire of IDPs and IDRs is remarkably diverse, encompassing critical roles across cellular signaling networks, transcriptional regulation, and stress response pathways [2] [7]. Their conformational plasticity makes them ideally suited for roles that require sensitivity to environmental changes and the ability to integrate multiple signals [4]. Key functional attributes include:

- Multivalent interaction capacity: IDPs typically interact with hundreds of different partners, acting as social hubs within the protein interaction network [2]. For example, the hepatitis C nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) is known to have dozens of binding partners [2].

- Post-translational modification sensing: Disordered regions frequently contain sites for post-translational modifications (PTMs) that can tune downstream signaling events [4]. The synergy between protein disorder, alternative splicing, and PTMs contributes to complex cellular signaling in eukaryotic organisms [4].

- Allosteric regulation: Intrinsic disorder enables allosteric regulation through mechanisms that may involve modulation of correlated protein dynamics without the formation of stable complexes [4].

- Liquid-liquid phase separation: IDPs can drive the formation of membraneless organelles through liquid-liquid phase separation, creating cellular compartments with distinct biochemical properties [8].

Table 1: Key Functional Attributes of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Regions

| Functional Attribute | Molecular Mechanism | Biological Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Multivalent Interactions | Dynamic, fluctuating structures enable binding to multiple partners | Hepatitis C NS5A protein with dozens of binding partners [2] |

| Environmental Sensing | Conformational ensembles responsive to cellular cues | Signaling receptors with disordered linkers and tails [2] |

| Allosteric Regulation | Modulation of correlated protein dynamics | α-Synuclein and Calmodulin interactions [4] |

| Phase Separation | Multivalent stochastic interactions driving condensate formation | Stress granule formation via G3BP1 [3] |

Disease Associations and Therapeutic Implications

The misfunction of IDPs is frequently associated with severe human diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders and cancer [4] [1]. In neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, most proteins contained in amyloid deposits are disordered peptides and proteins [1]. For example, α-synuclein, which is implicated in Parkinson's pathogenesis, exhibits a broad distribution of conformations in its native state but forms toxic aggregates in disease conditions [2]. Similarly, the formation of pathological amyloid fibrils by disordered proteins like amylin is linked to type 2 diabetes [3].

The involvement of IDPs in disease pathways makes them attractive therapeutic targets, though their lack of defined structures has long placed them in the "undruggable" category [9] [10]. Recent advances in computational methods and AI-based protein design are beginning to overcome these challenges, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention [9] [3].

Methodological Framework: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Experimental Techniques for Characterizing Disorder

The dynamic nature of IDPs makes them resistant to conventional structural biology methods like X-ray crystallography, which require stable, crystallizable proteins [2]. Consequently, researchers employ a suite of biophysical techniques that can capture structural heterogeneity and dynamics:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy: Provides residue-specific information on dynamics and transient structural propensities across multiple time scales [10] [5]. NMR parameters such as chemical shifts, J-couplings, and relaxation rates (R1, R2) offer insights into local conformations and dynamics [8].

- Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): Offers information about the global dimensions and shape characteristics of disordered ensembles [4] [5].

- Single-molecule Fluorescence Techniques: Methods such as single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) enable the characterization of distributions within conformational ensembles rather than just average properties [4].

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Detects secondary structure elements and monitors conformational changes [10].

Each technique provides complementary information, and integrative approaches that combine multiple data sources are often necessary to construct accurate models of IDP ensembles [5].

Computational and Simulation Approaches

Computational methods have become indispensable tools for studying IDPs, either alone or in combination with experimental data [6]. Key approaches include:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: All-atom MD simulations provide atomically detailed structural descriptions of conformational states and their dynamics [8] [5]. Modern force fields such as AMBER ff99SBnmr2 and CHARMM36m have been specifically improved to better represent disordered proteins [8] [5].

- Integrative Modeling: Maximum entropy reweighting approaches combine MD simulations with experimental data from NMR and SAXS to determine accurate atomic-resolution conformational ensembles [5].

- AI-Based Structure Prediction: While traditional structure prediction tools struggle with IDPs, new approaches like RFdiffusion are being developed to target disordered regions [3].

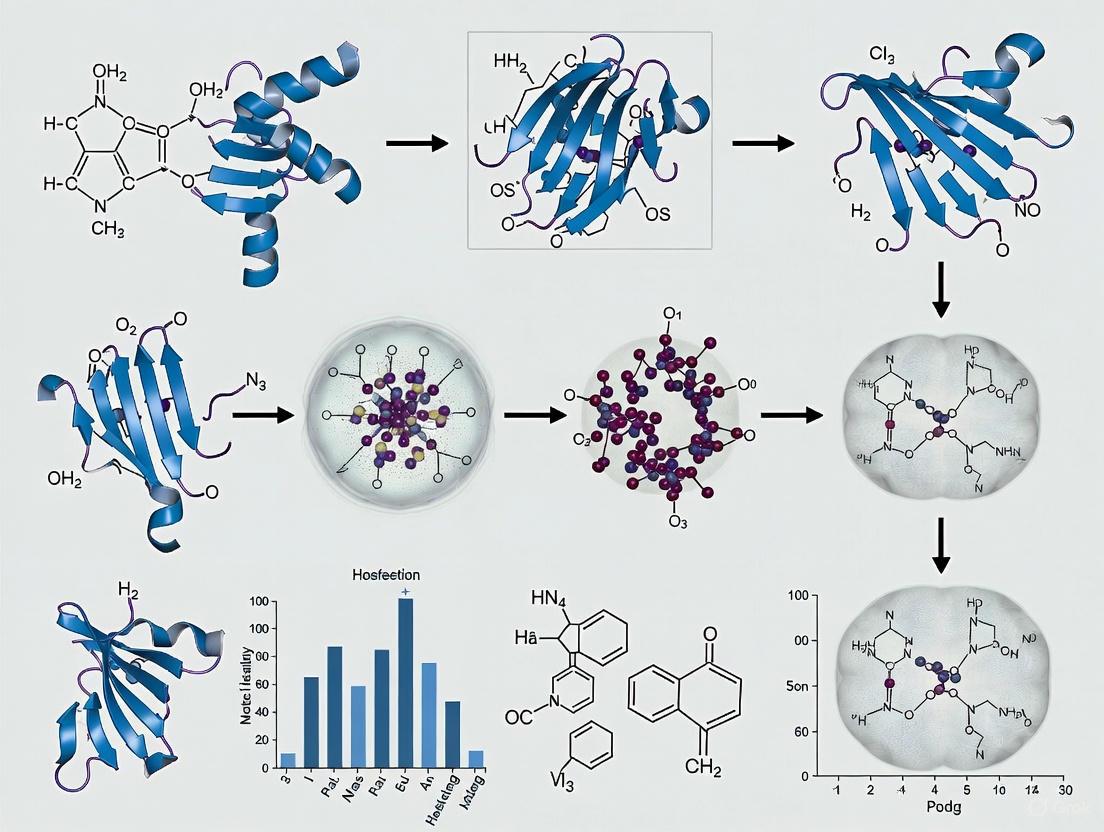

Diagram 1: Workflow for Determining IDP Conformational Ensembles. This integrative approach combines experimental data with molecular dynamics simulations to generate accurate atomic-resolution ensembles [5].

Cutting-Edge Research: Targeting the Untargetable

AI-Driven Design of IDP Binders

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have enabled the design of protein binders that target IDPs with high affinity and specificity, addressing a long-standing challenge in drug development [9] [3]. Two complementary approaches have demonstrated remarkable success:

- RFdiffusion-Based Method: This approach uses RFdiffusion to generate proteins that wrap around flexible targets, sampling both target and binder conformations simultaneously [3]. The method starts only from the target sequence and freely samples both target and binding protein conformations, generating complexes spanning a wide range of conformations [3].

- Logos Strategy: This method involves assembling binding proteins from a library of approximately 1,000 pre-made parts, creating binders for disordered targets by combining these modular components [9].

These approaches have produced high-affinity binders (with dissociation constants ranging from 3-100 nM) for various disordered targets, including amylin, C-peptide, VP48, and the prion protein [3]. The resulting designed binders are well-folded proteins that interact with specific subregions of the target in particular conformations rather than with the full disordered ensemble—an induced fit mechanism where the binder selects a specific conformation from the broad ensemble [3].

Experimental Validation and Therapeutic Applications

The functional efficacy of these designed binders has been demonstrated in various biochemical and cellular assays:

- Amylin binders inhibited amyloid fibril formation and dissociated existing fibrils linked to type 2 diabetes [3].

- G3BP1 binders disrupted stress granule formation in cells, demonstrating the potential to modulate phase separation behavior [3].

- Dynorphin binders blocked pain signaling inside lab-grown human cells, showing potential for therapeutic applications [9].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Designed Binders for Intrinsically Disordered Targets

| Target | Binder Affinity (Kd) | Therapeutic Relevance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amylin | 3.8 - 100 nM | Type 2 Diabetes | Inhibits fibril formation, dissociates existing fibrils [3] |

| C-peptide | 28 nM | Diabetes Diagnostics | High-affinity binding enables detection [3] |

| VP48 | 39 nM | Transcription Regulation | Binds activator with high specificity [3] |

| Dynorphin | Not specified | Pain Management | Blocks pain signaling in human cells [9] |

| G3BP1 | 10-100 nM | Stress Granule Formation | Disrupts granule formation in cells [3] |

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Approaches for Targeting Disordered Proteins. Two complementary strategies enable the design of high-affinity binders to previously "undruggable" disordered targets [9] [3].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Intrinsically Disordered Protein Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Reagents | Application in IDP Research |

|---|---|---|

| Spectroscopy | NMR Spectroscopy (15N R1/R2 relaxation) | Residue-specific dynamics and time scales [8] [10] |

| Scattering | Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) | Global dimensions and ensemble shape [4] [5] |

| Simulation | Molecular Dynamics (MD) with ff99SBnmr2, a99SB-disp | Atomic-resolution conformational sampling [8] [5] |

| AI Design | RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN | De novo binder design for disordered targets [3] |

| Ensemble Modeling | Maximum Entropy Reweighting | Integrating simulation and experimental data [5] |

| Cellular Validation | Fluorescence Imaging, BLI | Cellular localization and binding affinity [3] |

| Salvianolic acid E | Salvianolic acid E, CAS:142998-46-7, MF:C36H30O16, MW:718.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ginsenoside Ra2 | Ginsenoside Ra2, CAS:83459-42-1, MF:C58H98O26, MW:1211.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The study of intrinsically disordered proteins has fundamentally transformed our understanding of the structure-function relationship in molecular biology. The shift from a lock-and-key paradigm to a sequence-ensemble-function model represents not merely a minor adjustment but a profound reconceptualization of how proteins operate in cellular environments [2]. The inherent conformational heterogeneity of IDPs is not a structural failure but rather a functional adaptation that enables complex signaling, regulation, and response capabilities essential for eukaryotic life [4] [6].

The recent development of AI-based methods for designing high-affinity binders to disordered targets suggests that we are entering a new era where these previously "undruggable" proteins may become tractable therapeutic targets [9] [3]. As these technologies mature and integrate with advanced experimental characterization and simulation methods, we can anticipate significant advances in both our fundamental understanding of protein disorder and our ability to target these proteins for therapeutic purposes.

The continued exploration of intrinsically disordered proteins promises to reveal not only new biological mechanisms but also novel approaches to addressing some of the most challenging diseases, particularly in the realms of neurodegeneration and cancer. As we move beyond the lock-and-key metaphor, we embrace a more dynamic, nuanced, and ultimately more accurate view of protein function that reflects the complexity and adaptability of living systems.

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) represent a significant class of proteins that lack stable three-dimensional structures under physiological conditions yet are ubiquitous in eukaryotic proteomes. Comprising approximately one-third of eukaryotic proteomes and present in about 79% of proteins associated with human cancer, IDPs are now recognized as critical players in cellular signaling, transcriptional regulation, and dynamic protein-protein interactions [11]. Their structural flexibility enables unique functions, such as binding to multiple partners and facilitating rapid, reversible interactions crucial for cellular decision-making. This whitepaper delineates the quantitative aspects of IDP abundance, their thermodynamic and functional characteristics in signaling and regulation, and the associated experimental and computational methodologies. Furthermore, it explores the emerging therapeutic paradigm of targeting IDPs and the biomolecular condensates they form, which is particularly relevant for diseases like cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) challenge the long-held structure-function paradigm in protein science. Strictly defined, IDPs are proteins that are entirely disordered and do not fold into a single, stable globular shape [11]. Instead of the full-length protein, IDRs are partial regions of a protein that are disordered and are typically longer than 30 residues [11]. Unlike structured proteins, IDPs exist as dynamic ensembles of interconverting conformations, a property that confers distinct functional advantages. These include the ability to bind to multiple partners, high-specificity but low-affinity interactions, and the capacity to undergo rapid and often reversible structural transitions upon interaction with binding partners or in response to post-translational modifications.

The abundance of disorder is a hallmark of eukaryotic proteomes. IDRs longer than 30 residues account for approximately one-third of the proteomes of most eukaryotic organisms [11]. This prevalence is not merely incidental; it underscores the fundamental role protein disorder plays in complex cellular processes. According to analyses of the SWISS-PROT database, unstructured regions are present in about 79% of proteins associated with human cancer, highlighting their profound clinical significance [11]. The functions of IDPs are deeply linked to their dynamic nature, enabling them to participate in critical biological activities such as signal transduction, transcriptional control, and DNA repair, processes that require high plasticity and integrative capabilities.

Quantitative Analysis of IDP Abundance and Functional Distribution

Genome-wide surveys have revealed that intrinsic disorder is not randomly distributed across functional categories but is instead selected for specific physiological roles. Quantitative analyses classify proteomes into distinct types based on their preference for disorder in key functional categories, as detailed in Table 1 [12].

Table 1: Genome Classification Based on Disorder Preference Across Functional Categories

| Genome Type | Preference in Binding Proteins | Preference in Transcription Proteins | Preference in Catalytic Proteins | Example Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | No strong preference | Preference for disorder | Strong preference for order | Human, Mouse, Fruit Fly |

| Type II | No strong preference | No strong preference | Strong preference for order | Yeast, C. elegans |

| Type III | Strong preference for order | Strong preference for order | Strong preference for order | E. coli, B. anthracis |

This classification reveals a compelling evolutionary trend. The smaller bacterial genomes (e.g., E. coli) are universally Type III, exhibiting a strong preference for ordered structures across all major functional categories [12]. In contrast, eukaryotes are either Type I or II, with the larger, more complex genomes (e.g., human, mouse) typically falling into Type I, showing a distinct preference for disorder in transcription-related proteins [12]. This suggests that the evolution of cellular complexity in eukaryotes is correlated with the increased utilization of protein disorder, particularly in regulatory functions.

The thermodynamic properties of IDPs provide a foundation for understanding their functional distribution. A protein's stability is quantified by its folding free energy (ΔGf), where a positive ΔGf corresponds to a disordered protein [12]. The efficiency of a protein's function is directly linked to its ΔGf, and natural selection appears to act on stability to optimize function. For binding proteins, the equilibrium complex concentration [FS] is given by the relationship derived from the binding equilibrium, where only Kd < 10â»â· M can efficiently utilize disordered proteins (ΔGf > 0) [12]. This explains why high-affinity binding proteins, which are more common in eukaryotes, can tolerate or even prefer disorder. In contrast, for catalytic activity, the rate of substrate conversion (Vcat) is optimized only when ΔGf is less than approximately -1.0 kcal/mol, strongly favoring ordered structures [12]. This fundamental thermodynamic distinction is a key driver behind the observed functional distribution of IDPs.

The Role of IDPs in Signaling and Regulatory Pathways

IDPs are integral components of cellular signaling and regulatory networks, where their flexibility allows them to act as hubs and orchestrators of complex biochemical processes.

Signaling Transduction and Transcriptional Regulation

The conformational flexibility of IDPs enables them to be involved in a vast array of signaling transduction pathways [11]. They can act as scaffolds to bring together multiple components of a signaling cascade, facilitating rapid and efficient signal propagation. Furthermore, their ability to adopt different conformations allows them to integrate signals from various upstream regulators and translate them into specific downstream outputs. In transcriptional control, IDPs are particularly prevalent [11]. Many transcription factors contain extensive disordered regions that are critical for their function. These regions can facilitate the assembly of large multi-protein complexes on DNA, interact with co-activators and co-repressors, and undergo regulatory post-translational modifications that modulate their activity. The dynamic nature of IDPs is perfectly suited for the precise and often reversible control required for gene regulation.

Biomolecular Condensates and Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation

A fundamental mechanism through which IDPs exert their regulatory functions is by driving the formation of biomolecular condensates via a process called liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [11]. These are membrane-less organelles that compartmentalize and concentrate cellular components, thereby organizing the intracellular environment and regulating biochemical reactions spatially and temporally. In these condensates, molecules are classified as either scaffolds or clients [11]. Scaffolds, which are frequently IDPs, have a high local concentration and multiple interaction domains (valence); they initiate phase separation and form the structural backbone of the condensate [11]. Clients, on the other hand, are recruited into condensates through interactions with the scaffolds [11]. The following diagram illustrates the process of condensate formation and function.

Diagram: IDP-Driven Biomolecular Condensate Formation. Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) engage in multivalent interactions leading to liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and the formation of a biomolecular condensate. Within the condensate, IDPs often act as scaffolds to recruit client proteins, enabling functions like enhanced transcription or signal integration.

The role of IDPs in condensates is critically demonstrated in cancer. For example, the leukemogenic fusion protein NUP98-HOXA9 forms condensates that contribute to the formation of a super-enhancer-like binding pattern, promoting the transcription of leukemogenic genes [11]. Similarly, the oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc and the tumor suppressor p53 can form condensates that recruit RNA Polymerase II and P-TEFb to regulate downstream gene expression [11]. This mechanism allows powerful regulatory proteins, which often lack defined binding pockets for small molecules, to exert their effects, making the condensates themselves attractive therapeutic targets.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies for IDP Research

Studying IDPs is challenging due to their inherent lack of stable structure, which renders traditional structural biology methods like X-ray crystallography less effective. Consequently, the field relies on a combination of biophysical, biochemical, and computational approaches.

Key Experimental Protocols

A detailed methodology for analyzing protein disorder and binding affinity involves several key steps and reagents, as outlined in the table below.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for IDP Analysis

| Research Reagent / Method | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Equilibrium Binding Assays | Used to determine the dissociation constant (Kd) of protein interactions. For unstable proteins, the experimental Kdexp accounts for both folded and unfolded populations [12]. |

| Folding Free Energy (ΔGf) Measurement | Determined via a two-state equilibrium between unfolded (U) and folded (F) states, where [F]ₑₑ/[U]ₑₑ = e^(–ΔGf/RT). A positive ΔGf indicates a disordered protein [12]. |

| Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) Assays | In vitro experiments to observe condensate formation, typically by mixing scaffold proteins and clients under physiological conditions to monitor droplet formation [11]. |

| Stress Granule Induction | A cellular assay where environmental stress (e.g., oxidative stress) is applied to trigger the formation of membrane-less organelles, which can be studied to understand pathological condensates [11]. |

The logical workflow for an integrated study of an IDP's stability, function, and role in condensates is a multi-stage process, as visualized below.

Diagram: Integrated IDP Research Workflow. A proposed methodology for characterizing an IDP, beginning with computational disorder prediction, followed by experimental measurement of folding stability, functional biochemical assays, validation of phase separation behavior, and culminating in therapeutic exploration.

Advanced Computational Prediction

The experimental limitations in characterizing IDPs have driven the development of sophisticated computational predictors. Recent advances in 2025 include several key developments [7]:

- Ensemble deep-learning frameworks like IDP-EDL that integrate task-specific predictors.

- Transformer-based language models, such as ProtT5 and ESM-2, which provide rich residue-level embeddings for predicting disorder and molecular recognition features (MoRFs).

- Multi-feature fusion models like FusionEncoder that combine evolutionary, physicochemical, and semantic features to improve the accuracy of disorder boundary prediction.

- Hybrid approaches that integrate AlphaFold-predicted distance restraints with molecular dynamics simulations to generate structural ensembles of IDPs.

These tools, benchmarked by initiatives like the Critical Assessment of protein Intrinsic Disorder prediction (CAID2), have significantly improved the high-throughput identification and analysis of IDPs, facilitating their study in proteomics, post-translational modification mapping, and interactome analysis [7].

Therapeutic Targeting of IDPs in Human Disease

The critical roles of IDPs in signaling and regulation, coupled with their dysregulation in disease, make them compelling therapeutic targets. This is especially true for many oncoproteins previously considered "undruggable" due to their lack of stable binding pockets.

IDPs in Cancer and Neurodegeneration

The presence of aberrant biomolecular condensates has been robustly linked to cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [11]. In cancer, dysregulation can occur through three primary mechanisms:

- Genetic Mutations: Mutations in a scaffold or client protein can alter its valence and phase separation propensity. For example, cancer-related mutations in TIA1 protein increase its propensity to phase separate and form non-dynamic stress granules [11].

- Upstream Regulator Mutations: Mutations in regulators can lead to abnormal condensates. In Alzheimer's disease, Fyn-mediated tau phosphorylation can alter tau trafficking and cause synaptic impairment [11].

- Environmental Perturbations: Changes in cellular conditions like ATP levels, salt concentration, or pH can promote aberrant condensate formation throughout the cell, such as the stress granules that accelerate aging [11].

Condensate-Modifying Drugs (c-mods)

A novel class of therapeutics, known as condensate-modifying drugs (c-mods), has emerged to target the structure and function of biomolecular condensates [11]. These agents, which can be small molecules, peptides, or oligonucleotides, are classified based on their phenotypic outcomes, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: Classification of Condensate-Modifying Drugs (c-mods)

| c-mod Class | Mechanism of Action | Example Compound | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolver | Dissolves or prevents the formation of a target condensate. | ISRIB | Reverses eIF2α-dependent stress granule formation, restoring protein translation [11]. |

| Inducer | Triggers the formation of a condensate to increase biochemical reaction rates. | Tankyrase Inhibitors | Promote formation of a degradation condensate that reduces beta-catenin levels [11]. |

| Localizer | Alters the sub-cellular localization of condensate components. | Avrainvillamide | Restores NPM1 to the nucleus and nucleolus, enhancing efficacy against AML [11]. |

| Morpher | Alters condensate morphology and material properties (size, distribution). | Cyclopamine | Modifies material properties of RSV condensates, inhibiting viral replication [11]. |

Targeting the condensates formed by powerful oncoproteins like c-Myc and p53 represents a promising strategy to inhibit their function indirectly, making these previously undruggable targets amenable to therapeutic intervention [11].

IDPs and IDRs are abundant and critically important components of the eukaryotic proteome, playing indispensable roles in cellular signaling and regulation. Their unique biophysical properties, characterized by structural flexibility and dynamic interactions, allow them to perform functions that are poorly suited to structured proteins, including serving as hubs in signaling networks and driving the formation of regulatory biomolecular condensates via LLPS. Quantitative thermodynamic models explain the observed functional distribution of disorder, revealing that evolution acts on folding stability to optimize binding and catalytic functions. The dysregulation of IDPs and their condensates is a hallmark of serious human diseases, most notably cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. The ongoing development of advanced computational predictors and a new generation of therapeutics, the condensate-modifying drugs (c-mods), opens up exciting avenues for basic research and the development of novel treatment strategies aimed at these dynamic and pervasive players in cellular life.

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and multidomain proteins with flexible linkers represent a significant class of biomolecules that perform crucial biological functions without adopting single, stable three-dimensional structures. Unlike their folded counterparts, these proteins exhibit a high degree of structural heterogeneity and are best described not by a single structure but by conformational ensembles—collections of multiple coexisting structures with associated thermodynamic weights [13]. The characterization of these ensembles is fundamental to understanding the structure-function relationship of numerous macromolecular machines implicated in human diseases and increasingly pursued as drug targets [5].

The challenge in structural biology has shifted from determining single static structures to capturing the dynamic continuum of states that proteins, particularly IDPs, sample in solution. This paradigm requires integrative approaches that combine computational modeling with experimental biophysics to create accurate, atomic-resolution representations of protein dynamics [13] [5].

Methodological Frameworks for Ensemble Determination

The Integrative Approach Principle

Determining accurate conformational ensembles requires synthesizing information from multiple experimental and computational sources. No single technique can fully capture the structural heterogeneity of IDPs; therefore, integrative methods have become the gold standard [13] [5]. These approaches typically involve generating initial structural models through computational sampling, then refining these models against experimental data using statistical mechanical principles.

The core challenge lies in the fact that experimental data for IDPs are inherently ensemble-averaged and sparse, meaning they represent averages over millions of molecules and timepoints while reporting on only a subset of structural properties [5]. Computational models must therefore be constrained by multiple complementary experimental techniques to yield physically realistic ensembles.

Maximum Entropy Reweighting

A powerful and robust method for determining atomic-resolution conformational ensembles involves integrating all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental data using maximum entropy reweighting [5]. This approach introduces minimal perturbation to computational models while ensuring agreement with experimental observations.

The protocol involves:

- Running extensive all-atom MD simulations to sample conformational space

- Predicting experimental observables from each simulation frame using forward models

- Calculating statistical weights for each conformation that maximize entropy while fitting experimental data

- Using the Kish effective ensemble size to automatically balance restraint strengths without manual parameter tuning [5]

This method has demonstrated that in favorable cases, IDP ensembles obtained from different MD force fields converge to highly similar conformational distributions after reweighting, suggesting progress toward force-field independent ensemble determination [5].

Cryo-EM Heterogeneity Analysis

For larger macromolecular complexes, cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) single-particle analysis provides a direct method to visualize structural heterogeneity. Advanced computational methods now enable resolution of continuous conformational changes from cryo-EM datasets:

Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) represent protein density maps as sums of Gaussian functions, dramatically reducing computational complexity compared to voxel-based representations [14]. This approach enables analysis of structural variability at high resolution (up to ~3Ã…) by:

- Representing structures with thousands of Gaussian functions

- Using deep neural networks to map particles to conformational spaces

- Generating projection images for comparison with experimental data [14]

Model-guided heterogeneity analysis integrates molecular models into cryo-EM processing through:

- Hierarchical GMM for global movements

- Rigid body domain modeling for localized motions

- Bond constraint regularization from molecular models [14]

Experimental Techniques for Ensemble Constraints

Primary Biophysical Methods

| Technique | Data Type | Structural Information Provided | Application to IDPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shifts, J-couplings, residual dipolar couplings, relaxation rates | Local secondary structure, backbone dihedral angles, long-range contacts, dynamics on ps-ns timescales | Primary source of atomic-level structural and dynamic information [5] |

| SAXS | Scattering intensity I(q) vs. momentum transfer q | Global shape parameters, radius of gyration (Rg), pair distribution function | Sensitive to overall dimensions and shape characteristics [5] |

| Cryo-EM | 2D particle images | 3D density maps, conformational states, heterogeneity | Visualization of distinct compositional/conformational states [14] |

Complementary Approaches

Additional techniques provide valuable constraints for ensemble modeling:

- Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET): Distance distributions between specific sites

- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR): Distance distributions and flexibility

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX): Solvent accessibility and dynamics

- Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS): Collisional cross-sections

Computational Sampling Methods

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

All-atom MD simulations provide the foundation for atomic-resolution ensemble determination, with accuracy heavily dependent on force field selection [5]. State-of-the-art protein force fields and water models include:

| Force Field | Water Model | Key Features | Performance for IDPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| a99SB-disp | a99SB-disp water | Specifically optimized for disordered proteins | Excellent agreement with experimental data [5] |

| Charmm36m | TIP3P water | Corrected backbone parameters, improved side-chain interactions | Good performance, some residual compaction [5] |

| Charmm22* | TIP3P water | Modified backbone torsion potentials | Reasonable agreement, force field dependencies observed [5] |

Enhanced sampling techniques, including replica exchange MD and metadynamics, improve conformational sampling efficiency, particularly for slow dynamics and rare transitions.

Deep Generative Models

Emerging machine learning approaches offer promising alternatives to traditional MD:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for conformational space embedding [14]

- Deep neural networks for mapping cryo-EM particles to continuous conformational spaces [14]

- Generative adversarial networks (GANs) for sampling physically realistic conformations

These methods can be trained on MD simulations and experimental data to efficiently explore conformational landscapes.

Integrated Workflow: From Data to Ensemble

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for determining accurate conformational ensembles of IDPs using the maximum entropy reweighting approach:

Detailed Protocol: Maximum Entropy Reweighting

The maximum entropy reweighting procedure provides a fully automated approach for integrating MD simulations with experimental data [5]:

Step 1: Generate Initial Ensemble

- Perform long-timescale MD simulations (≥30μs) using state-of-the-art force fields

- Collect snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., every 1ns) to build initial ensemble

- Ensure adequate sampling of relevant conformational space

Step 2: Calculate Experimental Observables For each snapshot in the MD ensemble, calculate predicted values for all experimental measurements:

- NMR chemical shifts using empirical predictors (e.g., SPARTA+, SHIFTX2)

- NMR J-couplings and residual dipolar couplings from structure

- SAXS profiles using FoXS or CRYSOL

- Other relevant experimental data

Step 3: Determine Optimal Weights Maximize the entropy functional: $S = -∑{i=1}^N wi \ln wi$ subject to constraints: $∑{i=1}^N wi Oi^{calc} = O^{exp}$ and $∑{i=1}^N wi = 1$ where $wi$ are conformation weights, $Oi^{calc}$ are calculated observables, and $O^{exp}$ are experimental values.

Step 4: Validate Ensemble Quality

- Assess agreement with experimental data not used in reweighting

- Calculate Kish effective sample size: $K = (∑ wi)^2 / ∑ wi^2$

- Ensure K > 0.10 (retaining >10% of original ensemble diversity) [5]

- Analyze convergence across different force fields

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-labeled Amino Acids ($^{15}$N, $^{13}$C) | NMR spectroscopy for atomic-resolution structural and dynamic information | $^{15}$NH4Cl, $^{13}$C-glucose for uniform labeling; specific amino acids for selective labeling |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Matrices | Purification of IDPs and removal of aggregates that interfere with biophysical measurements | Superdex 75, Superdex 200; appropriate buffer conditions for maintaining protein solubility |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Vitrification of samples for single-particle cryo-EM analysis | Quantifoil, C-flat grids; optimization of blotting conditions and ice thickness |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | All-atom simulation of conformational dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD; compatible with modern force fields (a99SB-disp, CHARMM36m) |

| NMR Buffer Systems | Maintaining protein stability and solubility during data collection | Phosphate or Tris buffers, reducing agents (DTT/TCEP), protease inhibitors |

| SAXS Sample Cells | X-ray scattering measurements for global shape parameters | Capillary cells with precise temperature control; in-line SEC-SAXS capability |

| Mogroside III-E | Mogroside III-E, CAS:88901-37-5, MF:C48H82O19, MW:963.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Methyladenine | 1-Methyladenine|CAS 5142-22-3|Research Chemical |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Molecular Interactions

The determination of accurate conformational ensembles has profound implications for understanding molecular interactions in intrinsically disordered protein binding research:

Mechanistic Insights into Fuzzy Complexes IDPs often form "fuzzy complexes" where structural heterogeneity persists even in bound states. Ensemble characterization reveals:

- Conformational selection vs. induced fit binding mechanisms

- Pre-formed structural elements that facilitate recognition

- Dynamic interactions that enable regulatory functions

Rational Drug Design Strategies Traditional structure-based drug design fails for IDPs due to their inherent disorder. Ensemble-based approaches enable:

- Identification of transient binding pockets

- Targeting of specific conformational subpopulations

- Design of conformation-stabilizing inhibitors [5]

Biomolecular Condensate Formation Many IDPs undergo phase separation to form biomolecular condensates. Ensemble properties determine:

- Driving forces for multivalent interactions

- Material properties of condensates

- Regulation of cellular compartmentalization

The field of conformational ensemble determination is rapidly advancing toward accurate, force-field independent models of IDPs at atomic resolution [5]. Key future directions include:

Methodological Developments

- Integration of AI and deep learning with physical models

- Automated pipeline for multi-technique data integration

- Improved force fields through machine learning correction

- High-throughput ensemble determination for proteome-scale studies

Biological Applications

- Quantitative understanding of allosteric regulation in disordered systems

- Design of therapeutics targeting conformational ensembles

- Systems-level modeling of cellular signaling networks

- Relationship between conformational heterogeneity and cellular function

The convergence of experimental and computational approaches has transformed our ability to characterize structural heterogeneity, moving the field from assessing computational model accuracy toward genuine atomic-resolution integrative structural biology. As methods continue to mature, conformational ensemble determination will play an increasingly central role in understanding molecular interactions and enabling rational intervention in disordered protein systems.

Intrinsically disordered proteins and regions (IDPs/IDRs) challenge the traditional structure-function paradigm by performing critical cellular functions without adopting stable three-dimensional structures. This whitepaper examines the sophisticated mechanisms that enable IDPs to function as dynamic signaling hubs, balancing promiscuous interactions with specific binding to facilitate diverse cellular processes. Through an analysis of quantitative proteomic data, structural studies, and computational modeling, we delineate how intrinsic disorder enables functional versatility in molecular recognition, allosteric regulation, and cellular signaling. The findings presented herein have significant implications for understanding molecular interaction networks and developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting disordered proteins.

The classical structure-function paradigm, which posits that a unique three-dimensional structure is a prerequisite for protein function, has been fundamentally challenged by the discovery of intrinsically disordered proteins and regions. IDPs and IDRs exist as dynamic ensembles of interconverting conformations, lacking a well-defined hydrophobic core and stable tertiary structure [15] [16]. These proteins are characterized by distinctive sequence features, including low hydrophobicity, high net charge, and enrichment in specific amino acids (Pro, Gly, Glu, Ser, Lys) while being depleted in bulky hydrophobic and aromatic residues (Ile, Leu, Val, Phe, Tyr, Trp) that drive folding [15] [16]. This composition prevents collapse into a stable fold, instead favoring conformational heterogeneity.

Despite their lack of stable structure, IDPs are highly prevalent in eukaryotic proteomes and are central to crucial biological processes, including cell cycle regulation, signal transduction, transcription, and chromatin remodeling [17] [16]. Their prevalence increases with organismal complexity, suggesting an evolutionary selection for disorder to enable sophisticated regulatory mechanisms [16]. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to elucidate how IDPs achieve a remarkable balance—exhibiting sufficient promiscuity to interact with numerous partners while maintaining the specificity required for precise signaling, thereby establishing themselves as dynamic hubs in cellular networks.

Molecular Mechanisms of Promiscuity and Specificity

The functional advantages of IDPs stem from their unique structural dynamics and modular organization. Their ability to act as promiscuous yet specific hubs is encoded in their sequence and structural properties.

Anatomical Modules of IDPs/IDRs

The primary sequences of IDPs can be decomposed into functional modules that govern their interactions:

- Molecular Recognition Features (MoRFs): These are short segments (10-70 residues) within disordered regions that undergo disorder-to-order transitions upon binding to partner proteins [15]. MoRFs can be classified based on the secondary structure they adopt: α-MoRFs (α-helices), β-MoRFs (β-strands), ι-MoRFs (irregular structures), and complex-MoRFs (mixed structures) [15]. The tumor suppressor p53 exemplifies this mechanism, utilizing different MoRFs to interact with over 40 known partners.

- Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs): These are compact interaction modules, typically 3-10 residues long, that mediate transient protein-protein interactions in signaling networks [15]. Unlike MoRFs, SLiMs do not necessarily fold upon binding and often serve as sites for post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation [15].

- Low-Complexity Regions (LCRs): LCRs are sequences with biased amino acid composition and repetitive patterns that facilitate promiscuous interactions and are often involved in forming higher-order assemblies [15].

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Principles of Binding

IDPs employ diverse binding modes that exist on a continuum between fully ordered and fully disordered states:

- Folding-Upon-Binding: Many IDPs gain stable secondary and tertiary structure upon engaging with their binding partners. This process is driven by a favorable enthalpy gain that compensates for the entropic penalty of conformational restriction [15].

- Fuzzy Interactions: In many complexes, IDPs retain significant structural heterogeneity even in the bound state. This "fuzziness" can be static (disordered regions in fixed positions) or dynamic (random fuzziness), allowing for binding plasticity and adaptability [15].

- Preformed Structural Elements (PSEs): Some IDPs contain transiently structured regions within their conformational ensembles that serve as templates for binding, facilitating molecular recognition by reducing the entropic cost of folding-upon-binding [16].

Table 1: Characterization of IDP Binding Modules

| Module Type | Length (residues) | Structural Transition | Primary Function | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoRF | 10-70 | Disorder-to-order | Specific protein-protein interaction | p53-MDM2 interaction |

| SLiM | 3-10 | Variable (can remain disordered) | Transient signaling, PTM sites | Phosphodegrons, nuclear localization signals |

| LCR | Variable (often >40) | Variable | Promiscuous interactions, phase separation | Polyglutamine regions |

Quantitative Analysis of IDP Properties and Functions

Large-scale proteomic studies in model organisms like S. cerevisiae have revealed fundamental principles governing IDP abundance, interaction networks, and evolutionary constraints.

Abundance-Disorder Relationships and Evolutionary Constraints

Analysis of the S. cerevisiae proteome demonstrates a strong negative correlation between protein abundance and IDR content. Proteins with ≥30% of their residues in IDRs of ≥20 consecutive residues decrease in frequency as cellular concentration increases (Spearman's correlation rS = -0.76, p = 0.02) [17]. This correlation becomes more pronounced (rS = -0.94, p = 2e-16) when excluding the lowest abundance proteins (<8 ppm), where membrane proteins and rarely detected proteins are overrepresented [17]. This trend indicates negative selection against extensive disorder in highly abundant proteins, likely to minimize promiscuous non-functional interactions that could lead to deleterious sequestration of interaction partners in the crowded cellular environment [17].

Further analysis reveals that the amino acid composition of IDRs is also adapted to cellular abundance. IDRs in high-abundance proteins show reduced frequency of 'sticky' amino acids—those frequently involved in protein interfaces—suggesting evolutionary pressure to mitigate non-specific interactions while maintaining functional binding capabilities [17].

Functional Specialization and Multifunctionality

Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis reveals that high-abundance proteins with low IDR content are overrepresented in metabolic processes, ribosome biogenesis, translation, and protein folding [17]. Conversely, low-abundance proteins with high IDR content are enriched in cell cycle regulation, chromosome segregation, transcription, and signal transduction [17].

A clustering analysis of GO terms identified approximately 600 putative multifunctional proteins in S. cerevisiae that are significantly enriched in IDRs [17]. These multifunctional proteins contribute substantially to the observed network properties, as their IDRs contain more 'sticky' amino acids than both IDRs of non-multifunctional proteins and the surfaces of structured yeast proteins [17]. This compositional bias likely provides sufficient binding affinity for functional interactions, counterbalancing the entropic penalty associated with IDR binding.

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships Between IDP Properties and Cellular Parameters in S. cerevisiae

| Cellular Parameter | Relationship with IDP Content | Statistical Significance | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Abundance | Negative correlation | rS = -0.94, p = 2e-16 [17] | Negative selection against disorder in abundant proteins |

| PPI Network Connectivity | Positive correlation with partner diversity | Not specified | IDPs act as interaction hubs with functionally diverse partners |

| Multifunctionality | Positive correlation | ~600 proteins identified [17] | IDRs enable participation in multiple biological processes |

| "Sticky" Amino Acid Content | Higher in multifunctional proteins | Significant (p-value not specified) [17] | Compensates for entropic penalty of binding |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Advancements in both experimental and computational approaches have been crucial for characterizing the dynamic nature of IDPs and their interactions.

Experimental Techniques for IDP Characterization

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR is particularly suited for studying IDPs at atomic resolution, providing information about conformational dynamics, residual secondary structure, and transient interactions. 1H-15N HSQC spectra of IDPs exhibit characteristic narrow chemical shift dispersions, reflecting conformational heterogeneity [16]. In-cell NMR has enabled the study of IDPs like α-synuclein in their native cellular environments [16].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): While challenging for highly flexible systems, cryo-EM can visualize IDPs within larger complexes and has revealed structural insights into fuzzy complexes where disorder is retained in the bound state [16].

- Biophysical and Biochemical Assays: Techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry, fluorescence anisotropy, and circular dichroism provide complementary information about binding affinities, stoichiometries, and structural transitions.

Computational Approaches and Prediction Tools

- Disorder Prediction Algorithms: Tools like IUPred [17], DISOPRED, and PONDR analyze amino acid composition, charge/hydropathy relationships, and sequence patterns to predict disordered regions from primary sequences.

- Molecular Simulations: All-atom and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations model IDP conformational ensembles and binding processes, providing temporal resolution inaccessible to experimental methods [16]. These approaches have been particularly valuable for studying amyloid-forming proteins like Aβ and tau [16].

- Protein-Protein Interaction Analysis: Methods like PPI-Surfer employ 3D Zernike descriptors to quantitatively compare and classify protein-protein interaction interfaces, enabling identification of similar binding regions even in the absence of sequence or structural similarity [18]. This alignment-free approach characterizes PPI surfaces by segmenting them into overlapping patches described by mathematical representations of 3D shape and physicochemical properties [18].

Table 3: Methodologies for IDP/IDR Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology | NMR spectroscopy, Cryo-EM | Residue-specific dynamics, transient structures, fuzzy complexes | NMR ideal for dynamics; Cryo-EM for larger assemblies |

| Biophysical | ITC, fluorescence, CD | Binding affinities, thermodynamics, secondary structure | Solution studies under controlled conditions |

| Computational Prediction | IUPred, DISOPRED, PONDR | Disorder prediction from sequence | Various algorithms use different principles |

| Interaction Analysis | PPI-Surfer, iAlign, MAPPIS | Comparing PPI interfaces, identifying similar binding sites | Alignment-based and alignment-free methods available |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

The unique properties of IDPs present both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention, particularly in disease areas where traditional structured targets have proven difficult to drug.

IDPs are implicated in numerous human diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's (Aβ, tau), Parkinson's (α-synuclein), and Huntington's disease [16]. Their susceptibility to misfolding and aggregation, coupled with their central roles in signaling networks, makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Additionally, many oncoproteins and tumor suppressors, including p53, contain extensive disordered regions that mediate their regulatory functions [15].

Targeting IDPs requires innovative strategies beyond conventional small-molecule approaches that typically target well-defined pockets:

- Stabilization or Inhibition of Interactions: Small molecules that modulate IDP interactions with their binding partners can alter signaling pathways. For example, compounds that disrupt the p53-MDM2 interaction can reactivate p53 tumor suppressor function in cancer cells [18].

- Targeting Post-Translational Modifications: Since IDPs are frequently regulated by PTMs, targeting the modifying enzymes (kinases, acetyltransferases) represents an indirect approach to modulate IDP function.

- Structural Dispensation Compounds: Some successful SMPPIIs (Small Molecule Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitors) follow the "Rule of Four": molecular weight >400 Da, logP >4, >4 rings, and >4 hydrogen-bond acceptors [18]. These properties differ significantly from Lipinski's Rule of 5 for traditional drugs.

The development of PPI-Surfer and similar computational tools enables the identification of similar PPI interfaces across different protein complexes, facilitating drug repurposing and the discovery of novel SMPPIIs by recognizing common binding features [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for IDP Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Specific Function | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder Prediction Tools | Bioinformatics | Predict disordered regions from sequence | IUPred [17], DISOPRED, PONDR |

| IDP Databases | Bioinformatics | Curated structural and functional annotations | DisProt [16], MobiDB [16] |

| PPI Network Databases | Bioinformatics | Experimentally verified and predicted interactions | STRING, UniHI, IID [19] |

| NMR Isotope Labeling | Experimental | Enable high-resolution structural studies | 15N, 13C-labeled proteins for HSQC |

| PPI Interface Comparison | Computational | Quantify similarity of PPI surfaces | PPI-Surfer [18], iAlign, MAPPIS |

| Molecular Simulation Software | Computational | Model IDP conformational ensembles and dynamics | All-atom and coarse-grained MD packages |

| Platycoside K | Platycoside K, MF:C42H68O17, MW:845.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Himbadine | Himbadine, MF:C21H31NO2, MW:329.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

IDPs represent a fundamental expansion of the protein structure-function paradigm, employing unique mechanistic strategies to balance promiscuity and specificity in cellular networks. Their conformational plasticity enables multifunctional capabilities, serving as dynamic signaling hubs that integrate diverse cellular inputs. Quantitative proteomic studies reveal evolutionary constraints on IDP abundance and composition, reflecting the need to mitigate non-functional interactions while preserving functional versatility.

The continued development of specialized experimental and computational methods is essential for deciphering the mechanistic principles of IDP function. These advances will accelerate the targeting of IDPs in human diseases, particularly for conditions where traditional structured targets have proven intractable. As research in this field progresses, IDPs will undoubtedly yield new insights into cellular regulation and provide novel therapeutic opportunities for some of medicine's most challenging disorders.

From Theory to Therapy: Computational and Experimental Approaches for Targeting IDPs

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) challenge the classical structure-function paradigm, as they exist as dynamic ensembles of conformations and are prevalent in key cellular signaling and regulatory processes. Their binding mechanisms, often involving short linear motifs (SLiMs) and domain-motif interactions (DMIs), are crucial for understanding molecular interactions but are notoriously difficult to study experimentally. Computational prediction of protein structure from amino acid sequence has been achieved with unprecedented accuracy; however, the prediction of protein-protein interactions (PPIs), particularly those involving disordered regions, remains a significant challenge [20]. This whitepaper explores the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Protein Language Models (PLMs) to address this gap, providing a technical guide for researchers focused on molecular interactions in intrinsically disordered protein binding research.

Protein language models, trained on millions of protein sequences, learn evolutionary constraints and fundamental principles of protein biophysics. While routinely applied to protein folding, their retraining for interaction prediction opens new frontiers for IDPs [20]. This document details how these models, combined with specialized structural analysis tools, can be harnessed to predict the behavior of disordered regions and their binding interfaces, offering insights for drug development professionals aiming to target these dynamic processes.

Core AI and Protein Language Model Architectures

Evolution of Protein Language Models for Interaction Prediction

Traditional PLM-based PPI predictors use a pre-trained model to generate embeddings for individual proteins; a separate classification head then predicts interaction based on these static representations. This approach ignores the physical and co-evolutionary context between interacting partners [20]. PLM-interact, a novel framework, overcomes this by jointly encoding protein pairs. Inspired by next-sentence prediction in natural language processing, it fine-tunes the ESM-2 model with two key extensions: permitting longer sequence lengths to accommodate residue pairs, and implementing a binary classification task to learn the relationship between sequences [20]. This architecture allows amino acids in one protein to attend to specific residues in its partner through the transformer's attention mechanism, crucial for modeling transient disordered region interactions.

Another model, popEVE, demonstrates how evolutionary information can be calibrated for pathogenicity prediction. While not exclusively for disorder, its architecture—combining a generative AI model (EVE) with a large-language protein model and human population data—showcases the power of integrating cross-species and within-species variation to understand functional impacts of mutations, including those in IDRs [21].

Performance Benchmarking of State-of-the-Art Models

The performance of PLM-interact was rigorously benchmarked against other PPI prediction approaches like TUnA, TT3D, and D-SCRIPT using a multi-species dataset. Models were trained on human data and tested on held-out species. The following table summarizes the quantitative results, with AUPR (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve) as the key metric [20].

Table 1: Benchmarking results of PLM-interact against other models on cross-species PPI prediction. Performance is measured in AUPR.

| Test Species | PLM-interact (AUPR) | TUnA (AUPR) | TT3D (AUPR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | 0.850 | 0.833 | 0.732 |

| Fly | 0.760 | 0.703 | 0.628 |

| Worm | 0.740 | 0.698 | 0.616 |

| Yeast | 0.706 | 0.641 | 0.553 |

| E. coli | 0.722 | 0.675 | 0.605 |

PLM-interact achieved state-of-the-art performance, with significant improvements in evolutionarily divergent species like yeast and E. coli [20]. The model also excelled at assigning higher interaction probabilities to true positive PPIs, indicating a robust learned representation of interaction interfaces. When evaluated on a leakage-free gold standard dataset, PLM-interact matched TUnA in AUPR and AUROC but showed a 9% improvement in recall, highlighting its enhanced sensitivity in identifying positive interactions [20].

Experimental Protocols for Interaction Prediction

Workflow for Predicting Disordered Region Interactions

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for predicting SLiM- and DDI-mediated interactions involving disordered regions, integrating both bottom-up and top-down approaches.

Protocol 1: Bottom-Up Interface Prediction with PPI-ID

This protocol uses PPI-ID to identify candidate interacting regions from sequence alone, guiding targeted structural modeling [22].

- Input Preparation: Provide protein sequences or UniProt accession numbers for the two proteins of interest.

- Domain and Motif Detection:

- For domains, use the InterPro API or run InterProScan locally to generate a TSV file of identified domains (Pfam IDs).

- For SLiMs, use the ELM database or the ELM Predict tool to scan sequences for known motif regular expressions.

- Database Query: PPI-ID checks the compiled databases (3did, DOMINE for DDIs; ELM for DMIs) to determine if the identified domains and motifs constitute a potential interaction pair.

- Output Analysis: The tool outputs a table of amino acid residue ranges for each protein that are predicted to interact. This information is used to select specific regions for structural modeling with AlphaFold-Multimer, reducing computational load and improving model quality by focusing on probable interfaces [22].

Protocol 2: Top-Down Validation with Structural Filtering

This protocol validates a predicted or experimentally derived structural model of a complex [22].

- Model Input: Provide a PDB file of the protein complex, which can be derived from experimental methods or from a computational prediction tool like AlphaFold-Multimer.

- Interface Mapping: PPI-ID maps all known DDIs and DMIs from its databases onto the 3D structure.

- Contact Distance Filtering: Use the

filter_by_distance()function, which employs alpha carbon coordinates, to filter the list of potential interactions. Only pairs within a user-specified distance (e.g., 4-11 Ã…) are considered physically plausible interfaces. - Residue Labeling: PPI-ID labels the specific amino acids involved in the filtered interactions, providing functional insight into the binding mechanism.

Protocol 3: Predicting Mutation Effects on Interactions

A fine-tuned version of PLM-interact can predict how mutations impact PPIs [20].

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of wild-type and mutant protein sequences, along with their interacting partners. Labels should indicate whether the mutation increases or decreases interaction strength (data available from IntAct database: MI:0382 and MI:0119).

- Model Fine-tuning: Fine-tune PLM-interact on this mutation data, treating the effect as a binary classification task.

- Inference: Apply the model to novel mutations in a protein of interest while its interacting partner remains in the wild-type state. The model outputs a prediction of the mutation's effect on the interaction, which is particularly valuable for assessing variants of unknown significance in disordered regions.

Visualization and Analysis of Interaction Networks

Understanding complex interaction data requires effective visualization. The following diagram maps the logical relationships and data flow between key computational tools and resources in this field.

Tools like VISIBIOweb provide free, web-based visualization and layout services for pathway models in BioPAX format, using the standard Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) [23]. This is critical for representing the complex, compound graphs inherent to biological pathways, including those involving molecular complexes and subcellular locations formed through disordered protein interactions.

The following table details key computational tools and databases essential for conducting research in AI-driven prediction of disordered protein interactions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Based Disorder Interaction Prediction.

| Tool / Database Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Disordered Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLM-interact | AI Model | Jointly encodes protein pairs to predict PPIs and mutation effects [20]. | Infers interfaces for SLiM-mediated interactions from sequence. |

| PPI-ID | Analysis Tool | Maps interaction domains/motifs onto structures and filters by contact distance [22]. | Core tool for identifying and validating DMIs involving SLiMs. |

| ESM-2 | Protein Language Model | Provides foundational protein representations; backbone for fine-tuning [20]. | Learns evolutionary features of disordered regions. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Structure Predictor | Predicts 3D structures of protein complexes [22]. | Models complexes where one partner contains disordered regions. |

| ELM Database | Motif Database | Repository of known Short Linear Motifs (SLiMs) and their interacting domains [22]. | Definitive resource for identifying candidate linear motifs. |

| InterPro / Pfam | Domain Database | Identifies structured domains within protein sequences [22]. | Defines potential DDI partners for motifs in disordered regions. |

| 3did & DOMINE | DDI Database | Curated databases of Domain-Domain Interactions from structures and predictions [22]. | Provides data on stable interaction interfaces. |

| VISIBIOweb | Visualization Service | Creates SBGN-standard visualizations of biological pathways from BioPAX models [23]. | Helps map disordered protein interactions into larger network contexts. |

| popEVE | AI Model | Scores variants by disease likelihood, comparing severity across genes [21]. | Assesses impact of mutations in disordered regions on function. |

The integration of AI and Protein Language Models represents a paradigm shift in our ability to decipher the molecular interactions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Frameworks like PLM-interact, which learn the intricate relationships between biomolecules directly from their sequences, coupled with analytical tools like PPI-ID that bridge the gap between sequence motifs and 3D structural interfaces, provide an unprecedented toolkit for researchers. As these models continue to evolve, validated through rigorous cross-species benchmarks and clinical datasets for rare diseases, they hold the promise of not only accelerating fundamental research but also of streamlining the diagnosis of genetic disorders and identifying novel therapeutic targets for conditions driven by dysregulated molecular interactions.

The advent of RFdiffusion represents a paradigm shift in de novo protein design, enabling the generation of high-affinity binders targeting structured proteins and challenging intrinsically disordered regions. This whitepaper details how this generative AI technology, particularly when integrated with sequence-design tools like ProteinMPNN, facilitates the creation of picomolar-affinity binders against therapeutic targets. By combining structural prediction networks with generative diffusion models, RFdiffusion provides a powerful computational framework for addressing complex molecular interactions, including those involving helical peptides and disordered regions that have long eluded traditional design approaches. Experimental validation across multiple systems confirms the method's exceptional success rates and precision, opening new frontiers in drug development and molecular research.

RFdiffusion is a guided diffusion model for protein design that combines structure prediction networks with generative diffusion models, a machine-learning algorithm specializing in adding and removing noise to create novel structures [24]. Unlike prior design methods that required testing tens of thousands of molecules to find a single successful candidate, RFdiffusion achieves remarkable computational success, sometimes requiring testing as little as one design per challenge [24]. The system begins with random noise distributions and gradually denoises them into coherent protein structures through a process inspired by image generation systems like DALL-E [24].

The technology emerges at a critical juncture in molecular interaction research, particularly relevant to the study of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). These regions challenge the conventional structure-function paradigm, as they do not adopt specific three-dimensional structures yet perform crucial cellular functions [25]. Recent research has revealed that IDRs are governed by molecular "grammars" - specific amino acid compositions and syntaxes that determine their functions and interaction capabilities [25]. Understanding these grammars is essential for cancer research, as altered IDR grammars can rewire interaction networks and activate cellular proliferation programs [25].

RFdiffusion addresses two fundamental challenges in binder design for such systems. First, designing interactions between proteins and short peptides with helical propensity has been an unmet challenge, despite the importance of helical peptide hormones like parathyroid hormone and glucagon [26]. Second, the conformational variability of disordered peptides presents unique challenges for traditional design approaches that assume structured targets.

Core Methodology: Integration of RFdiffusion with Complementary Tools

RFdiffusion Architecture and Mechanism

RFdiffusion operates as a generative model that leverages the RoseTTAFold architecture, which integrates three-track neural networks processing sequence, distance, and coordinate information simultaneously. The diffusion process involves:

- Forward diffusion: Gradually adding noise to protein structures until they become random distributions

- Reverse diffusion: Guided denoising process that generates novel protein structures conditioned on specific design goals

- Conditioning mechanisms: Input specifications that steer the generation toward desired structural features or binding interfaces

The system can be applied to various design challenges including topology-constrained protein monomer design, protein binder design, symmetric oligomer design, and enzyme active site scaffolding [24].

Integration with ProteinMPNN for Sequence Optimization

Following structure generation with RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN (a deep neural network for protein sequence optimization) is employed to design sequences that fold into the generated structures [27] [26]. This two-step process - generating backbones with RFdiffusion then designing sequences with ProteinMPNN - has proven highly successful. In one case, this combination improved binder affinity by approximately three orders of magnitude, achieving 6.04 nM affinity to parathyroid hormone [26].

Advanced Sampling Strategies

The RFdiffusion framework incorporates several specialized sampling approaches:

- Partial diffusion: Successive noising and denoising of input structure models to refine designs [26]

- Target-guided diffusion: Extension of RFdiffusion to enable binder design to flexible targets [26]

- Hallucination: Monte Carlo search in sequence space optimizing for confident binding metrics (pLDDT and pAE) without pre-specifying binder or peptide geometry [26]

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Comprehensive Binder Design Pipeline

The standard workflow for designing high-affinity binders using RFdiffusion integrates multiple computational and experimental steps as illustrated below:

Specialized Protocols for Challenging Targets

Helical Peptide Binder Design

For designing binders to helical peptides, researchers have employed parametric generation of helical bundle scaffolds with open grooves [26]. This approach samples scaffolds consisting of a three-helix groove supported by two buttressing helices using Crick parameterization of α-helical coiled coils. The protocol involves:

- Scaffold library generation: Sampling a range of supercoiling and helix-helix spacings to accommodate various helical peptide targets

- Interface extension: Using RFjoint Inpainting to extend binder interfaces for more favorable interactions

- Affinity maturation: Combinatorial library generation using degenerate codons followed by yeast display selection

This method has generated binders with picomolar affinity for targets like TGFβRII, CTLA-4, and PD-L1 [28].

Hallucination for Flexible Targets

The Hallucination approach enables binder design without pre-specification of binder or peptide geometry [26]:

- Initialization: Start from random seed binder sequences (length 60-100 residues)

- Monte Carlo optimization: Perform ~5,000 steps of sequence substitutions optimizing for AF2 confidence metrics (pLDDT and pAE)

- Sequence redesign: Apply ProteinMPNN to the output binder structure

- Co-expression screening: Test designs by co-expression of GFP-tagged target peptide and His-tagged binders

This protocol has successfully generated binders to the apoptosis-related BH3 domain of Bid, which is unstructured in isolation but adopts an α-helix upon binding [26].

Quantitative Results and Performance Metrics

Binding Affinity and Biophysical Properties

RFdiffusion-generated binders demonstrate exceptional performance across multiple target classes as summarized below:

Table 1: Experimental Performance of RFdiffusion-Generated Binders

| Target | Application | Binding Affinity | Thermal Stability | Experimental Validation | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) | Peptide hormone detection | 6.04 nM (from µM starting point) | High | Yeast display, FP, SEC | [26] |

| TGFβRII | Cancer immunotherapy | < 1 nM | >95°C | X-ray crystallography (1.24Å), BLI | [28] |

| CTLA-4 | Cancer immunotherapy | < 0.1 nM | >95°C | X-ray crystallography, cell signaling assays | [28] |

| PD-L1 | Cancer immunotherapy | 0.646 ± 0.02 nM | >95°C | BLI, cell assays | [28] |

| Keap1 Kelch domain | Antioxidant pathway modulation | Strong binding affinity | Good biophysical characteristics | MD simulations, in silico screening | [27] |

| Glucagon (GCG) | Metabolic disease | 231 nM | High | Yeast display, FP, SEC | [26] |

| Secretin (SCT) | Gastrointestinal function | 2.7 nM | High | Yeast display, FP | [26] |

Structural Accuracy and Design Precision

The structural precision of RFdiffusion designs has been rigorously validated through experimental methods:

- High-resolution crystallography: Co-crystal structures of TGFβRII and CTLA-4 binders show remarkable agreement with design models (Cα RMSD of 0.55Å over the full complex) [28]

- Accurate interface prediction: Designed hydrophobic patches and hydrogen bonding networks closely match computational models [28]

- Stability metrics: Circular dichroism spectra confirm helical structure with minimal change even at 95°C [28]

Table 2: Structural and Interface Properties of Designed Binders

| Target | Binder ID | Buried Surface Area (Ų) | Polar/Apolar Ratio | Convexity Binder/Target (1/Å) | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβRII | 5HCSTGFBR21 | 637.6 / 1043.2 | 0.61 | -0.0669 / 0.056 | Extended groove with shape complementarity |

| CTLA-4 | 5HCSCTLA41 | 595.6 / 1266.1 | 0.47 | -0.0593 / 0.058 | Concave surface matching convex target |

| PD-L1 | 5HCSPDL11 | 710.4 / 1108.9 | 0.64 | -0.0310 / 0.001 | Optimized hydrophobic packing |