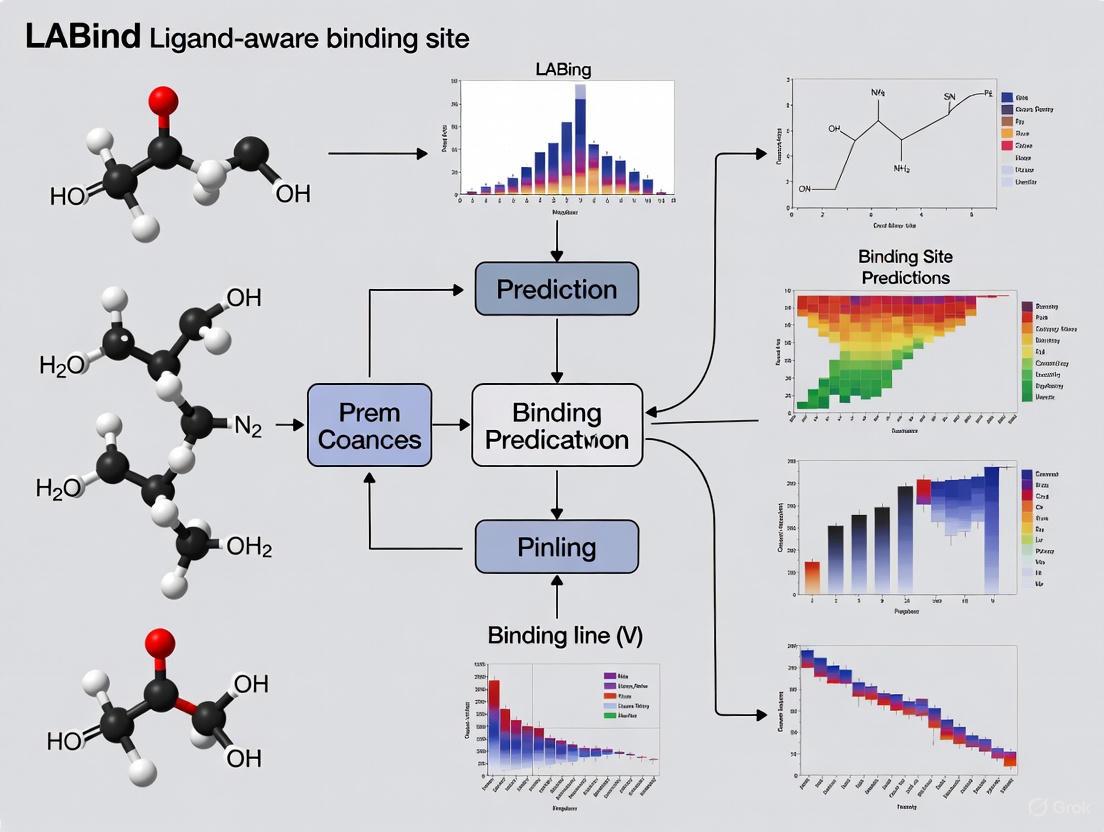

LABind: A Ligand-Aware Deep Learning Framework for Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding Sites

This article explores LABind, a novel structure-based deep learning method that revolutionizes protein-ligand binding site prediction by explicitly incorporating ligand information.

LABind: A Ligand-Aware Deep Learning Framework for Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding Sites

Abstract

This article explores LABind, a novel structure-based deep learning method that revolutionizes protein-ligand binding site prediction by explicitly incorporating ligand information. Unlike traditional single-ligand or ligand-agnostic methods, LABind utilizes a graph transformer and cross-attention mechanism to learn distinct binding characteristics for different ligands, including small molecules and ions. We detail its architecture, which integrates protein sequence (Ankh), structural features (DSSP), and ligand representations (MolFormer). The content covers LABind's superior performance on benchmark datasets, its unique ability to generalize to unseen ligands, and its practical applications in molecular docking and drug discovery. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of LABind's methodology, validation, and implementation for enhancing structure-based drug design.

The Paradigm Shift in Binding Site Prediction: From Ligand-Agnostic to Ligand-Aware

The Critical Role of Protein-Ligand Interactions in Biology and Drug Discovery

Protein-ligand interactions are fundamental processes in which proteins form specific complexes with small molecules (ligands) or other macromolecules. These interactions govern a vast array of crucial biochemical processes in living organisms, including enzyme catalysis, signal transduction, gene regulation, and molecular recognition [1]. In enzyme catalysis, the chemical transformation of enzyme-bound ligands occurs, while in signal transduction, ligands such as hormones bind to receptors to initiate cellular responses. The profound biological significance of these interactions has made them a central focus in pharmaceutical research, as they provide the fundamental mechanism by which most drugs exert their therapeutic effects [2].

The study of these interactions has evolved significantly from the early lock-and-key principle proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894 to more contemporary models that better account for protein dynamics. Our current understanding has been enriched by induced-fit theory and conformational selection mechanisms, which recognize that both protein and ligand can undergo mutual conformational adjustments during binding [1]. Advances in structural biology, particularly through techniques like X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), have provided atomic-resolution views of numerous protein-ligand complexes, while molecular dynamics simulations have enabled direct observation of binding events and accompanying conformational transitions [1].

For drug discovery professionals, understanding protein-ligand interactions is paramount. The affinity and specificity of these interactions directly determine the efficacy and safety of therapeutic compounds. The binding affinity, quantified by the dissociation constant (Kd), and the binding kinetics, characterized by association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates, are fundamental properties optimized during drug development [2]. Furthermore, the drug-target residence time has emerged as a critical parameter influencing drug efficacy in vivo, sometimes proving more important than binding affinity alone [1].

Mechanisms and Models of Molecular Recognition

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Principles

The formation of a protein-ligand complex is governed by the fundamental principles of thermodynamics and kinetics. Spontaneous binding occurs only when the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the system is negative at constant pressure and temperature. The standard binding free energy (ΔG°) relates to the binding constant (Kb) through the fundamental equation: ΔG° = -RTlnKb, where R is the universal gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin [2]. This relationship highlights that the stability of a protein-ligand complex is directly determined by the ratio of the kinetic rate constants for association (kon) and dissociation (koff).

The binding free energy can be further decomposed into its enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) components through the equation: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [2]. Enthalpy changes primarily reflect the formation and breaking of non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions. Entropy changes encompass alterations in the conformational freedom of the protein and ligand, as well as changes in solvent organization upon binding. A phenomenon known as enthalpy-entropy compensation often complicates the optimization of binding affinity, where improvements in enthalpic contributions may be offset by unfavorable entropic changes, and vice versa [2].

Binding Mechanisms

The molecular mechanisms underlying protein-ligand binding have been conceptualized through several models that have evolved with our understanding of protein dynamics:

Lock-and-Key Model: This historical model proposes that proteins and ligands possess complementary rigid structures that fit together precisely, similar to a key fitting into a lock. While simplistic, this model explains the high specificity observed in many molecular recognition events [2].

Induced Fit Model: Proposed by Koshland in 1958, this model suggests that the binding of a ligand induces conformational changes in the protein that enhance complementarity and binding affinity. This mechanism acknowledges the flexibility of protein structures and their ability to adapt to ligand binding [1] [2].

Conformational Selection Model: This more recent model posits that proteins exist in multiple conformational states in equilibrium. Ligands selectively bind to and stabilize specific pre-existing conformations, shifting the equilibrium toward these states. Evidence suggests this mechanism is at least as common as induced fit, and both mechanisms may operate in the same binding process [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein-Ligand Binding Mechanisms

| Binding Mechanism | Key Principle | Role of Protein Dynamics | Thermodynamic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lock-and-Key | Pre-formed structural complementarity | Minimal | Often favorable entropy due to limited conformational changes |

| Induced Fit | Ligand-induced conformational changes | Central to binding process | Often unfavorable entropy due to conformational restriction |

| Conformational Selection | Selection of pre-existing conformations | Foundation of binding equilibrium | Favorable binding entropy through population shift |

Contemporary research has revealed additional nuances in protein-ligand interactions, including the biological significance of weak and transient interactions characterized by low affinity constants and short lifetimes, and multivalent binding where multiple binding sites simultaneously engage, leading to enhanced affinity and selectivity [1]. Allosteric binding, where molecules interact at sites distinct from the active site, causing conformational changes that alter protein activity, plays particularly important roles in signaling and regulatory pathways [1].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Approaches for Binding Analysis

Experimental characterization of protein-ligand interactions employs diverse methodologies that provide complementary information about binding affinity, kinetics, and structural aspects:

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): This technique directly measures the heat change associated with binding, allowing simultaneous determination of binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS). ITC is considered the gold standard for thermodynamic characterization but requires significant amounts of sample and may lack the sensitivity for very tight binding interactions [2].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): SPR measures binding events in real-time without labeling, providing detailed information about association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates in addition to binding affinity. High-throughput SPR (HT-SPR) platforms have expanded the capability for large-scale screening campaigns [1] [2].

Fluorescence Polarization (FP): This method monitors the change in fluorescence polarization when a small fluorescent ligand binds to a larger protein, enabling determination of binding constants. FP is sensitive, suitable for high-throughput screening, but requires labeling with fluorescent probes [2].

High-Throughput Mass Spectrometry (HT-MS): This label-free method has gained popularity for large-scale screening campaigns, allowing direct probing of protein-ligand binding without interfering optical or fluorescent labels [1].

HT-PELSA (High-Throughput Peptide-Centric Local Stability Assay): This recently developed method detects protein-ligand interactions by monitoring how ligand binding affects protein stability and resistance to proteolytic cleavage. HT-PELSA significantly improves throughput (400 samples per day compared to 30 with previous methods) and works directly with complex biological samples including crude cell lysates, tissues, and bacterial extracts. This enables detection of previously challenging targets like membrane proteins, which represent approximately 60% of all known drug targets [3].

Computational Prediction Methods

Computational approaches have become indispensable tools for predicting and analyzing protein-ligand interactions, especially with advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning:

Molecular Docking: These methods predict the binding pose (orientation and conformation) of a ligand in a protein binding site using efficient search algorithms and empirical scoring functions. Docking is widely used for virtual screening of compound libraries in structure-based drug design [2].

Binding Free Energy Calculations: These more rigorous approaches compute binding free energies based on statistical thermodynamics, providing higher accuracy but requiring extensive conformational sampling and computational resources. Methods include free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI) [2].

Deep Learning Models: Recent advances have introduced various deep learning approaches for predicting protein-ligand interactions. Interformer is an interaction-aware model built on a Graph-Transformer architecture that explicitly captures non-covalent interactions using an interaction-aware mixture density network. This model achieves state-of-the-art performance in docking tasks, with 84.09% accuracy on the Posebusters benchmark and 63.9% on the PDBbind time-split benchmark [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for Protein-Ligand Interaction Analysis

| Method | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Binding pose prediction, virtual screening | Fast, suitable for large compound libraries | Limited accuracy in scoring and affinity prediction |

| Free Energy Calculations | Accurate binding affinity prediction | High accuracy for relative binding affinities | Computationally intensive, limited throughput |

| Deep Learning Docking (e.g., Interformer) | Binding pose and affinity prediction | High accuracy, ability to model specific interactions | Requires extensive training data, limited interpretability |

| Binding Site Prediction (e.g., LABind) | Identification of ligand binding sites | Ligand-aware prediction, handles unseen ligands | Dependent on quality of protein structure |

LABind: A Ligand-Aware Approach to Binding Site Prediction

Methodological Framework

LABind represents a significant advancement in binding site prediction through its unique ligand-aware architecture that explicitly incorporates information about both the protein and ligand. Traditional computational methods for predicting protein-ligand binding sites have limitations: single-ligand-oriented methods are tailored to specific ligands, while multi-ligand-oriented methods typically lack explicit ligand encoding, constraining their ability to generalize to unseen ligands [5]. LABind addresses these limitations by learning the distinct binding characteristics between proteins and ligands through a sophisticated computational framework.

The LABind architecture integrates multiple components to achieve ligand-aware binding site prediction. The method takes as input the SMILES sequence of the ligand and the sequence and structure of the protein receptor. Ligand representation is obtained using the MolFormer pre-trained model, while protein representation combines sequence embeddings from the Ankh pre-trained language model with structural features derived from DSSP (Dictionary of Protein Secondary Structure). The protein structure is converted into a graph where nodes represent residues and edges capture spatial relationships. A cross-attention mechanism then learns the interactions between the ligand representation and protein representation, enabling the model to capture binding patterns specific to the given ligand. Finally, a multi-layer perceptron classifier predicts the binding sites based on these learned interactions [5].

Performance and Applications

LABind has demonstrated superior performance across multiple benchmark datasets (DS1, DS2, and DS3), outperforming both single-ligand-oriented and other multi-ligand-oriented methods. The model's effectiveness extends to predicting binding sites for unseen ligands not encountered during training, highlighting its generalization capability [5]. This attribute is particularly valuable in drug discovery, where researchers often investigate novel compounds with limited structural information.

The applications of LABind extend beyond basic binding site prediction. The method has been successfully applied to binding site center localization, where it identifies the central coordinates of binding pockets through clustering of predicted binding residues. Additionally, LABind enhances molecular docking tasks by providing more accurate binding site information, leading to improved docking pose generation when combined with docking programs like Smina [5]. A sequence-based implementation of LABind that leverages protein structures predicted by ESMFold further expands its utility to proteins without experimentally determined structures [5].

In practical applications, LABind has demonstrated its value through case studies such as predicting binding sites of the SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 macrodomain with unseen ligands [5]. This real-world validation underscores the method's potential to accelerate drug discovery by providing accurate binding site predictions for emerging therapeutic targets.

Protocols for Binding Site Analysis and Validation

Protocol 1: LABind-Based Binding Site Prediction

This protocol details the procedure for predicting ligand-aware binding sites using the LABind framework.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials:

- Protein Structure Files: PDB format files from experimental determination or prediction tools (AlphaFold2, ESMFold)

- Ligand Information: SMILES strings representing ligand structures

- Computational Environment: Python with PyTorch deep learning framework

- LABind Model: Pre-trained LABind model available from publication supplements

- Sequence Analysis Tools: DSSP for secondary structure assignment

- Embedding Models: Ankh protein language model and MolFormer molecular model

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- For the protein receptor, obtain both the amino acid sequence and 3D structure file. If using an experimentally determined structure, ensure proper preprocessing including removal of heteroatoms and hydrogens.

- For the ligand, generate or obtain the canonical SMILES string representing its structure.

Feature Extraction:

- Process the protein sequence through the Ankh protein language model to generate sequence embeddings.

- Calculate structural features using DSSP, including secondary structure, solvent accessibility, and backbone torsion angles.

- Process the ligand SMILES string through the MolFormer model to generate molecular representations.

Graph Construction:

- Convert the protein structure into a graph representation where nodes correspond to amino acid residues.

- Compute spatial features for nodes (angles, distances, directions) and edges (directions, rotations, distances between residues).

- Concatenate sequence embeddings with structural features to create comprehensive node representations.

Interaction Learning:

- Process the protein graph through the graph transformer to capture local spatial contexts and binding patterns.

- Apply the cross-attention mechanism between the ligand representation and protein representation to learn binding characteristics.

Binding Site Prediction:

- Feed the interaction-aware representations into the multi-layer perceptron classifier.

- Generate per-residue predictions indicating the probability of each residue belonging to a binding site.

- Apply a distance threshold (typically 5Ã…) to define binding site boundaries based on predicted residues.

Validation:

- Compare predictions with experimentally determined binding sites from PDB structures when available.

- Evaluate prediction quality using metrics including AUC, AUPR, MCC, and F1-score.

LABind Binding Site Prediction Workflow

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation Using HT-PELSA

This protocol describes the procedure for experimental validation of protein-ligand interactions using the high-throughput HT-PELSA method, which is particularly valuable for membrane proteins and complex biological samples.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials:

- Biological Samples: Purified proteins, cell lysates, tissue homogenates, or bacterial lysates

- Ligand Solutions: Compounds of interest dissolved in appropriate buffers

- Protease Solution: Trypsin or other specific proteases

- HT-PELSA Kit: Commercially available reagents or custom components

- Multi-well Plates: 96-well or 384-well format for high-throughput processing

- Mass Spectrometry System: LC-MS/MS system with high sensitivity

- Automation Platform: Liquid handling system for sample processing

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein samples (purified proteins, cell lysates, or tissue extracts) in appropriate buffer conditions.

- Distribute samples into multi-well plates using automated liquid handling systems.

Ligand Treatment:

- Add ligands of interest to sample wells at varying concentrations.

- Include control wells without ligands for baseline comparison.

- Incubate plates to allow binding equilibrium (typically 30 minutes to 2 hours at appropriate temperature).

Proteolysis:

- Add protease (typically trypsin) to all wells under controlled conditions.

- Allow limited proteolysis for a specific duration (optimized for each system).

- Quench proteolysis by adding protease inhibitors or adjusting pH.

Peptide Separation:

- Utilize the hydrophobic nature of intact proteins versus peptides for separation.

- Apply samples to a surface that preferentially retains intact proteins.

- Collect the flow-through containing the proteolytic peptides.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze peptides using LC-MS/MS to identify and quantify proteolytic fragments.

- Compare peptide abundance between ligand-treated and control samples.

Data Analysis:

- Identify regions of increased protein stability (reduced proteolysis) in ligand-treated samples.

- Map stabilized regions to protein structures to infer ligand binding sites.

- Integrate data across multiple ligand concentrations for dose-response analysis.

HT-PELSA Experimental Workflow

Protocol 3: Interformer-Based Molecular Docking

This protocol describes the procedure for protein-ligand docking using the Interformer model, which explicitly captures non-covalent interactions for improved pose prediction.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials:

- Protein Structures: PDB files with binding site definitions

- Ligand Structures: 3D conformations in SDF or MOL2 format

- Interformer Model: Pre-trained Interformer implementation

- Computational Resources: GPU-accelerated computing environment

- Analysis Tools: RMSD calculation scripts, visualization software

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Prepare the protein structure by selecting relevant chains and removing irrelevant heteroatoms.

- Define the binding site using known ligand coordinates or binding site prediction tools.

- Prepare ligand structures with correct protonation states and initial 3D conformations.

Feature Generation:

- Represent the protein and ligand as graphs with atoms as nodes.

- Assign pharmacophore atom types as node features to capture chemical properties.

- Calculate Euclidean distances between atoms as edge features.

Model Processing:

- Process protein and ligand graphs through Intra-Blocks to capture intra-molecular interactions.

- Pass updated features through Inter-Blocks to capture protein-ligand inter-interactions.

- Generate Inter-representations for each protein-ligand atom pair.

Interaction-Aware Sampling:

- Process Inter-representations through the mixture density network (MDN) to predict parameters of Gaussian functions.

- Model specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) with dedicated Gaussian components.

- Aggregate mixture density functions into a combined energy function.

Pose Generation:

- Use Monte Carlo sampling to generate candidate ligand conformations by minimizing the energy function.

- Generate top-k candidate poses ranked by energy scores.

Pose Scoring and Affinity Prediction:

- Process generated poses through the scoring pipeline to predict binding affinity and pose confidence.

- Apply contrastive learning to distinguish favorable from unfavorable poses.

- Select final poses based on combined evaluation of geometry and interaction patterns.

Protein-ligand interactions represent a fundamental paradigm in molecular biology and drug discovery, governing critical cellular processes and providing the mechanistic basis for most therapeutic interventions. The study of these interactions has evolved from simple lock-and-key models to sophisticated frameworks that incorporate protein dynamics, conformational selection, and allosteric mechanisms. Contemporary research continues to reveal new complexities, including the biological significance of weak and transient interactions, multivalent binding, and the roles of intrinsically disordered protein regions.

The emergence of ligand-aware computational methods like LABind represents a significant advancement in binding site prediction, addressing limitations of previous approaches by explicitly modeling ligand properties and their interactions with protein targets. The ability to predict binding sites for unseen ligands opens new possibilities for drug discovery, particularly in the early stages of target validation and lead compound identification. Similarly, interaction-aware docking models like Interformer demonstrate how explicit modeling of non-covalent interactions can significantly improve the accuracy of binding pose prediction, a critical factor in structure-based drug design.

Future developments in protein-ligand interaction research will likely focus on several key areas. First, the integration of experimental high-throughput methods like HT-PELSA with advanced computational predictions will provide more comprehensive validation frameworks. Second, the application of these methods to challenging target classes, particularly membrane proteins and intrinsically disordered proteins, will expand the druggable proteome. Finally, the increasing availability of large-scale structural databases and continuing advances in deep learning methodologies promise to further accelerate our understanding of these fundamental biological interactions and their therapeutic exploitation.

Application Note

This document, framed within the broader research on the LABind (Ligand-Aware Binding site prediction) method, delineates the critical limitations inherent in traditional computational approaches for predicting protein-ligand binding sites. It is intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to inform the selection and development of computational tools in structural biology and drug discovery.

Protein-ligand interactions are fundamental to understanding biological processes and are pivotal in drug discovery and design [5]. While experimental methods like X-ray crystallography provide high-resolution data, they are resource-intensive and lack the scalability required for high-throughput analysis [5] [6]. Consequently, computational methods have been developed to predict binding sites. These methods are broadly categorized as single-ligand-oriented or multi-ligand-oriented, each with a distinct set of constraints that hinder their generalizability and effectiveness, particularly for novel ligands [5]. The emergence of ligand-aware models like LABind aims to directly address these limitations by explicitly learning interactions between proteins and ligands [5] [7].

Critical Limitations of Traditional Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core limitations of traditional single-ligand and multi-ligand oriented methods, which are further explicated in the subsequent sections.

| Method Category | Core Principle | Key Limitations | Impact on Research & Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Ligand-Oriented Methods [5] | Train individual models for a specific ligand type (e.g., calcium ions, ATP). | 1. Inability to Generalize: Models fail for ligands not seen during training [5].2. Template Dependency: Template-based methods (e.g., IonCom) fail without high-quality protein templates [5].3. Information Scarcity: Sequence-based methods (e.g., TargetS) lack spatial structure data, limiting accuracy [5]. | Hinders screening against diverse compound libraries and novel target identification. |

| Multi-Ligand-Oriented Methods [5] | Train a single model on datasets containing multiple ligands, often ignoring specific ligand properties. | 1. Ligand-Agnostic Modeling: Methods (e.g., P2Rank, DeepPocket) use protein structure but overlook binding pattern differences between ligands [5].2. Restricted Ligand Scope: Models (e.g., LMetalSite, GPSite) are often limited to a pre-defined set of ligands and cannot handle unseen ones [5]. | Limits understanding of ligand-specific interactions, reducing predictive accuracy and utility for novel drug candidates. |

| General Workflow Deficits | Most existing models treat protein and ligand encoding as separate streams [7]. | Failure to Integrate Ligand Chemistry: The protein representation is learned without "seeing" the ligand, missing nuances of biochemical context [7]. | Models struggle to distinguish paralogues with high sequence identity but different ligand binding profiles, affecting specificity predictions [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Binding Site Prediction Methods

To objectively evaluate and compare new ligand-aware methods against traditional ones, a rigorous benchmarking protocol is essential. The following methodology, derived from the development and validation of LABind and related models, provides a standardized framework.

Objective: To assess the performance and generalizability of protein-ligand binding site prediction methods across diverse datasets and ligands, including those not seen during training.

Materials:

- Datasets: Use multiple, curated benchmark datasets with non-redundant protein-ligand complexes. Common examples include DS1, DS2, and DS3, as used in LABind validation [5]. Ensure strict sequence identity thresholds (e.g., <30%) between training and test sets to prevent homology bias [7].

- Pre-processed Structures: Experimentally determined structures from the PDB or high-confidence predicted structures from tools like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold [5] [8].

- Ligand Information: SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings for all ligands to facilitate ligand-aware encoding [5] [7].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Partitioning

- Curate protein-ligand complexes from sources like the PDBbind dataset [7] [9].

- Partition the data into training, validation, and test sets using homology-aware clustering algorithms (e.g., GraphPart) to ensure generalization to unseen protein folds [7].

- For "unseen ligand" tests, explicitly hold out all complexes containing specific ligands from the training phase [5].

Model Training and Prediction

- For traditional methods, train or execute models according to their specific design (e.g., single-ligand model for a specific ion, or a multi-ligand model like P2Rank).

- For ligand-aware methods (e.g., LABind, ProtLigand), input both the protein structure and the ligand's SMILES string. The model will learn a joint representation using mechanisms like cross-attention [5] [7].

Performance Evaluation and Analysis

- Primary Metrics: Calculate standard metrics for binary classification, prioritizing Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) due to the inherent class imbalance between binding and non-binding residues [5]. Also report Recall (Rec), Precision (Pre), F1 score, and AUC [5].

- Binding Center Localization: For functional analysis, cluster predicted binding residues and calculate the distance (DCC) between the predicted binding site center and the true center [5].

- Downstream Task Validation: Use the predicted binding sites to constrain molecular docking tasks (e.g., using Smina) and evaluate the improvement in docking pose accuracy [5].

The table below lists key computational tools and datasets essential for research in this field.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PDBbind [7] [9] | Dataset | A widely used, curated database of protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data, serving as a standard for training and benchmarking. |

| AlphaFold DB / ESMFold [5] [7] | Software/Database | Provides high-accuracy predicted protein structures, enabling binding site prediction for proteins without experimentally solved structures. |

| SMILES [5] [7] | Representation | A line notation system for representing ligand molecular structures as text, which can be encoded by molecular language models (e.g., MolFormer). |

| LABind [5] | Software | A structure-based method that uses graph transformers and cross-attention to predict binding sites for small molecules and ions in a ligand-aware manner. |

| ProtLigand [7] | Software | A general-purpose protein language model that incorporates ligand context via cross-attention to enrich protein representations for downstream tasks. |

| Smina [5] | Software | A molecular docking tool used to evaluate the practical utility of predicted binding sites by refining and scoring docking poses. |

Conceptual Workflow and Method Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between traditional methods, their limitations, and the integrated approach of ligand-aware prediction.

Conceptual Workflow of Binding Site Prediction

LABind's Integrated Architecture to Overcome Traditional Limitations

LABind addresses the core deficits of previous methods through a unified architecture that explicitly learns protein-ligand interactions, as shown in the workflow below.

LABind's Ligand-Aware Prediction Workflow

This integrated workflow allows LABind to capture distinct binding characteristics for any given ligand, enabling accurate predictions even for ligands not present in its training data, thereby directly overcoming the primary limitation of traditional methods [5].

Predicting protein-ligand binding sites is fundamental to understanding biological processes and accelerating drug discovery. Traditional computational methods face significant limitations when encountering novel compounds. Single-ligand-oriented methods (e.g., IonCom, GraphBind) are trained on specific ligand types but fail to generalize to unseen ligands [5]. Multi-ligand-oriented methods (e.g., P2Rank, DeepSurf) combine multiple datasets but often lack explicit ligand encoding, limiting their predictive capability for novel compounds [5]. This creates a critical unmet need: accurately predicting binding sites for ligands not present in training datasets.

LABind (Ligand-Aware Binding site prediction) addresses this gap through a structure-based approach that explicitly models interactions between proteins and ligands. By learning distinct binding characteristics, LABind achieves generalized predictive capability without requiring ligand-specific retraining [5] [10]. This Application Note details the methodology, experimental validation, and implementation protocols for predicting binding sites for unseen ligands using LABind.

LABind Architecture and Workflow

LABind employs an integrated computational architecture that processes both ligand and protein information through specialized feature extraction modules [5]. The system utilizes a graph transformer to capture binding patterns within protein spatial contexts and incorporates a cross-attention mechanism to learn protein-ligand interaction characteristics [5]. This architecture enables the model to generalize to ligands not encountered during training.

Table: LABind System Components and Functions

| Component | Function | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Representation Module | Encodes molecular properties from SMILES sequences | MolFormer pre-trained model [5] |

| Protein Representation Module | Generates embeddings from sequence and structural features | Ankh pre-trained model & DSSP [5] |

| Graph Converter | Transforms protein structure into graph representation | Protein atomic coordinates [5] |

| Attention-Based Learning Interaction | Learns distinct binding characteristics between proteins and ligands | Cross-attention mechanism [5] |

| MLP Classifier | Predicts binding residue probabilities | Integrated protein-ligand features [5] |

Computational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates LABind's complete computational workflow for binding site prediction:

Experimental Validation and Performance

Benchmark Dataset Composition

LABind was rigorously evaluated on three benchmark datasets (DS1, DS2, DS3) containing diverse protein-ligand complexes [5]. The model's performance was assessed specifically for its capability to predict binding sites for unseen ligands—those not present in the training data. The experimental design validated LABind's generalized binding site prediction capability across small molecules, ions, and novel compounds.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

LABind demonstrated superior performance compared to existing methods across multiple evaluation metrics, particularly for unseen ligands [5]. The following table summarizes the key performance metrics from benchmark evaluations:

Table: LABind Performance Metrics on Benchmark Datasets

| Evaluation Metric | LABind Performance | Comparison Methods | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under ROC Curve) | Superior to competing methods | Outperformed single-ligand and multi-ligand oriented methods | Robust discriminative ability [5] |

| AUPR (Area Under Precision-Recall Curve) | Superior to competing methods | Consistently higher across datasets | Effective handling of class imbalance [5] |

| MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) | Superior to competing methods | Better balanced performance | Comprehensive metric for binary classification [5] |

| F1 Score | Superior to competing methods | Improved precision-recall balance | Optimal threshold selection [5] |

| Binding Site Center Localization (DCC) | Superior to competing methods | More accurate center identification | Enhanced utility for molecular docking [5] |

Performance on Unseen Ligands

LABind's architectural innovation enables exceptional performance on unseen ligands. The cross-attention mechanism allows the model to learn generalized interaction patterns rather than memorizing specific ligand characteristics [5]. In practical applications, LABind successfully predicted binding sites for the SARS-CoV-2 NSP3 macrodomain with unseen ligands, demonstrating real-world utility in drug discovery [5].

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Binding Site Prediction

Purpose: Predict binding sites for a specific ligand using experimentally determined protein structures.

Materials:

- Protein Structure: PDB format file from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM

- Ligand Information: SMILES sequence of the target ligand

- Computational Environment: LABind installation with required dependencies

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Prepare protein structure file in PDB format

- Extract or generate ligand SMILES sequence

- Validate file formats and completeness

Feature Extraction:

- Process ligand SMILES through MolFormer to generate molecular representations [5]

- Process protein sequence through Ankh pre-trained model to obtain sequence embeddings [5]

- Analyze protein structure with DSSP to obtain structural features [5]

- Convert protein structure to graph representation with spatial features

Interaction Analysis:

- Integrate protein and ligand representations through cross-attention mechanism

- Generate protein-ligand interaction features

Binding Site Prediction:

- Process integrated features through MLP classifier

- Generate residue-level binding probability predictions

- Apply threshold (default 0.5) to identify binding residues

Result Interpretation:

- Visualize predicted binding sites on protein structure

- Calculate binding site centers through clustering of predicted residues

- Generate confidence metrics for predictions

Troubleshooting:

- Low confidence predictions may indicate poor quality input structures

- Consider using alternative protein structure prediction tools if experimental structure unavailable

- Verify ligand SMILES sequence validity before processing

Protocol 2: Sequence-Based Binding Site Prediction

Purpose: Predict binding sites using only protein sequence information when 3D structures are unavailable.

Materials:

- Protein Sequence: FASTA format file containing amino acid sequence

- Ligand Information: SMILES sequence of the target ligand

- Computational Environment: LABind with ESMFold or OmegaFold integration

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Prepare protein sequence in FASTA format

- Extract or generate ligand SMILES sequence

Protein Structure Prediction:

- Process protein sequence through ESMFold or OmegaFold to predict 3D structure [5]

- Validate predicted structure quality using confidence metrics

Binding Site Prediction:

- Follow Protocol 1 steps 2-5 using predicted protein structure

- Account for potential reduced accuracy due to structure prediction limitations

Result Validation:

- Compare predictions with known homologous structures if available

- Assess consistency across multiple structure prediction algorithms

Note: Sequence-based predictions may show reduced accuracy compared to structure-based approaches but remain valuable for preliminary screening [5].

Protocol 3: Binding Site Center Localization

Purpose: Identify binding site centers from predicted binding residues for molecular docking applications.

Materials:

- Predicted Binding Residues: Output from Protocol 1 or 2

- Protein Structure: Corresponding 3D structure file

Procedure:

- Residue Clustering:

- Cluster predicted binding residues based on spatial proximity

- Apply distance threshold (default 8Ã…) to define binding sites [11]

Center Calculation:

- Calculate geometric center of each binding residue cluster

- Refine center position based on predicted residue probabilities

Validation Metrics:

- Calculate DCC (Distance to true binding site Center)

- Calculate DCA (Distance to Closest ligand Atom) [5]

- Compare with known binding sites for validation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in LABind Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| MolFormer | Molecular representation learning | Generates ligand features from SMILES sequences [5] |

| Ankh | Protein language model | Provides protein sequence embeddings [5] |

| DSSP | Secondary structure assignment | Extracts structural features from protein 3D coordinates [5] |

| ESMFold/OmegaFold | Protein structure prediction | Generates 3D structures from sequences for sequence-based protocol [5] |

| Graph Transformer | Spatial pattern recognition | Captures binding patterns in protein structural graphs [5] |

| Cross-Attention Mechanism | Protein-ligand interaction learning | Learns distinct binding characteristics between proteins and ligands [5] |

| SMILES Sequences | Ligand representation | Standardized input format for ligand molecular structures [5] |

| PDB Files | Protein structure storage | Standardized format for experimental and predicted structures [5] |

Implementation Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the implementation pathway for LABind binding site prediction, highlighting critical decision points and methodology selection:

Technical Notes and Applications

Performance Optimization

LABind's performance can be optimized through several strategies. For proteins with unknown structures, using multiple structure prediction algorithms (ESMFold, OmegaFold) and comparing results can enhance reliability [5]. The model effectively handles various ligand types including small molecules and ions through its unified architecture [5]. For critical applications, consider ensemble approaches combining LABind predictions with complementary methods.

Molecular Docking Enhancement

LABind significantly enhances molecular docking accuracy by providing precise binding site information. When applied to docking pose generation with Smina, LABind-predicted binding sites substantially improved pose accuracy [5]. This integration is particularly valuable for virtual screening campaigns targeting novel ligands without known binding sites.

Limitations and Considerations

While LABind advances prediction for unseen ligands, performance may vary for highly unusual ligand chemistries distant from training data. Predictions based on computationally generated structures show slightly reduced accuracy compared to experimental structures [5]. The cross-attention mechanism, while enabling generalization, may have higher computational requirements than simpler methods.

LABind is a structure-based computational method designed to predict protein binding sites for small molecules and ions in a ligand-aware manner. By explicitly learning the representations of both proteins and ligands, LABind can generalize to predict binding sites for ligands not encountered during its training phase, addressing a significant limitation of previous single-ligand and multi-ligand-oriented methods [5]. This framework captures distinct binding characteristics between proteins and ligands, demonstrating superior performance across multiple benchmark datasets and showing strong potential to enhance downstream applications in drug discovery, such as molecular docking and the identification of previously underexploited binding sites [5] [12].

Protein-ligand interactions are fundamental to biological processes like enzyme catalysis and signal transduction, making their accurate prediction a critical objective in drug discovery and design [5]. While experimental methods exist to determine these interactions, they are often resource-intensive and low-throughput. Existing computational methods face a core limitation: they are either tailored to specific ligands, which restricts their applicability, or they are multi-ligand methods that fail to explicitly incorporate ligand information during training, thus constraining their predictive power and generalizability [5].

The LABind framework was developed to overcome these challenges. Its key innovation lies in its ability to be truly "ligand-aware." Unlike previous methods, LABind explicitly models ions and small molecules alongside proteins during training. This allows it to learn a unified model that integrates ligand properties, enabling the accurate prediction of binding sites for a wide range of ligands, including those not present in the training data (unseen ligands) [5]. This capability is particularly valuable for targeting challenging membrane-protein interfaces, where ligands exhibit distinct chemical properties and binding sites have unique amino acid compositions [12].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the key computational tools and data resources essential for implementing and utilizing the LABind framework.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for LABind

| Item Name | Type | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure/Sequence | Input Data | Provides the primary input for the model, either as a 3D atomic coordinate file (PDB format) or an amino acid sequence [5]. |

| Ligand SMILES String | Input Data | A text-based representation of the ligand's molecular structure, used by the molecular pre-trained language model to generate ligand representations [5]. |

| Ankh | Software Tool | A protein pre-trained language model. It generates sophisticated sequence-based embeddings from the protein's amino acid sequence [5]. |

| DSSP | Software Tool | A database of secondary structure assignments. It takes the protein structure and calculates key structural features (e.g., solvent accessibility, secondary structure) [5]. |

| MolFormer | Software Model | A molecular pre-trained language model. It processes the ligand's SMILES string to generate a numerical representation that encodes the ligand's chemical properties [5]. |

| ESMFold / OmegaFold | Software Tool | Protein structure prediction tools. They are used in LABind's sequence-based mode to generate 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences when an experimental structure is unavailable [5]. |

Methodological Protocols

The LABind architecture integrates information from proteins and ligands to make its final prediction. The diagram below illustrates the logical flow and data transformations involved in the process.

Protocol 1: Data Preparation and Feature Extraction

This protocol details the steps for preparing input data for LABind, which can accept both protein structures and sequences.

1.1 Protein Input via Experimental Structure * Input: A protein structure file in PDB format. * Step 1: Sequence Embedding. Extract the protein's amino acid sequence from the PDB file and process it using the Ankh pre-trained language model to obtain a sequence embedding vector for each residue [5]. * Step 2: Structural Feature Extraction. Process the PDB file with DSSP to compute structure-derived features for each residue, such as solvent accessibility and secondary structure [5]. * Step 3: Graph Construction. Convert the 3D protein structure into a graph where nodes represent residues. For each residue (node), calculate spatial features including angles, distances, and directions from atomic coordinates. For each residue pair (edge), calculate spatial features including directions, rotations, and distances [5].

1.2 Protein Input via Sequence Only * Input: A protein amino acid sequence (FASTA format). * Step 1: Structure Prediction. Submit the sequence to a protein structure prediction tool such as ESMFold or OmegaFold to generate a predicted 3D structure [5]. * Step 2. Proceed with Steps 1, 2, and 3 from section 1.1 using the predicted structure.

1.3 Ligand Input * Input: The ligand's SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) string. * Step 1: Ligand Representation. Input the SMILES string into the MolFormer molecular pre-trained language model to generate a numerical representation vector that encapsulates the ligand's chemical properties [5].

Protocol 2: Model Execution and Binding Site Prediction

This protocol covers the core computational steps performed by the LABind model after feature extraction.

2.1 Integration and Interaction Learning * Step 1: Protein Representation Fusion. Combine the Ankh sequence embeddings and DSSP structural features. This combined protein-DSSP embedding is then added to the node spatial features of the protein graph to form the final protein representation [5]. * Step 2: Cross-Attention. Process the final protein representation and the ligand representation from MolFormer through a cross-attention mechanism. This module allows the model to learn the specific binding characteristics and interactions between the given protein and the specific ligand [5].

2.2 Output and Interpretation * Step 3: Classification. The output from the cross-attention module is fed into a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) classifier. This classifier performs a per-residue binary prediction, determining whether each residue in the protein is part of a binding site for the query ligand [5]. * Step 4: Analysis. The output is a list of residues predicted to be binding sites. These residues can be clustered to localize the center of the binding pocket for further analysis or docking studies [5].

Performance and Validation Data

LABind's performance has been rigorously evaluated on multiple benchmark datasets. The following tables summarize its quantitative performance against other advanced methods.

Table 2: Model Performance on Key Benchmark Datasets [5]

| Dataset | Evaluation Metric | LABind Performance | Comparison with Other Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | AUC | > 0.90 | Outperformed single-ligand-oriented (e.g., GraphBind, LigBind) and multi-ligand-oriented methods (e.g., P2Rank, DeepSurf) [5]. |

| DS2 | AUPR | > 0.85 | Demonstrated superior performance, with AUPR and MCC being particularly highlighted due to the class imbalance in binding site prediction [5]. |

| DS3 | MCC | > 0.65 | Showed marked advantages, indicating a strong balance between true positive and true negative predictions [5]. |

| Generalization | F1 Score | High on unseen ligands | Validated the model's ability to effectively integrate ligand information to predict binding sites for ligands not seen during training [5]. |

Table 3: Performance in Downstream Applications [5]

| Application Task | Metric | LABind Performance / Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site Center Localization | DCC / DCA* | Outperformed competing methods by achieving shorter distances between predicted and true binding site centers [5]. |

| Use with Predicted Structures | AUC / AUPR | Maintained robust and reliable performance when experimental structures were replaced with those predicted by ESMFold or OmegaFold [5]. |

| Molecular Docking (with Smina) | Docking Pose Accuracy | Substantially enhanced the accuracy of generated docking poses when the docking search space was restricted to LABind's predicted binding sites [5]. |

*DCC: Distance between predicted and true binding site center. DCA: Distance between predicted center and closest ligand atom.

Application Notes

AN-1: Targeting Lipid-Exposed Binding Sites

Background: Many therapeutically relevant membrane proteins contain ligand binding sites embedded within the lipid bilayer. These sites are often underexploited in drug discovery because ligands that bind there require distinct chemical properties, such as higher lipophilicity (clogP) and molecular weight, compared to ligands for soluble proteins [12].

LABind Application: LABind is uniquely suited for investigating these sites due to its ligand-aware nature. Researchers can input the SMILES string of a lipophilic compound and a membrane protein structure. LABind can then predict potential binding sites at the protein-lipid interface, guided by the chemical features of the ligand. The model's ability to learn from a diverse set of ligands in its training data, including those in the Lipid-Interacting LigAnd Complexes Database (LILAC-DB), allows it to recognize patterns associated with these challenging binding environments [12].

Protocol:

- Identify a target membrane protein (e.g., a GPCR or ion channel).

- Select or design a ligand candidate with properties conducive to membrane partitioning (high clogP, halogens).

- Run LABind with the protein structure and ligand SMILES string.

- Analyze predicted binding sites. Sites located within transmembrane domains and exposed to the membrane are high-priority candidates for lipid-exposed binding.

AN-2: Enhancing Molecular Docking Workflows

Background: Molecular docking is a cornerstone of structure-based drug design, but its accuracy and computational efficiency are highly dependent on the correct definition of the binding site.

LABind Application: Using LABind to predefine the docking search space can significantly improve both the accuracy and speed of molecular docking simulations.

Protocol:

- For a given protein target of unknown binding site, run LABind with the proposed ligand's SMILES string.

- Cluster the predicted binding residues to define a specific binding pocket or volume.

- Use this LABind-defined pocket as the restricted search space in a molecular docking program like Smina [5].

- This protocol filters out incorrect poses generated in irrelevant regions of the protein, leading to a higher success rate in identifying the correct binding pose.

Architecture and Implementation: How LABind's Ligand-Aware Model Works

Accurately predicting protein-ligand binding sites is a critical challenge in computational biology and drug discovery. LABind (Ligand-Aware Binding site prediction) addresses key limitations in existing methods by developing a unified model that explicitly learns the distinct binding characteristics between proteins and various ligands, including small molecules and ions [5]. The model's effectiveness hinges on its sophisticated processing of two primary input modalities: the protein structure and the ligand's SMILES sequence. By transforming these raw inputs into rich, structured representations, LABind captures the complex patterns underlying protein-ligand interactions, enabling high-performance prediction even for ligands not encountered during training [5] [10]. This document details the protocols for processing these inputs and the key reagents required for implementation.

Processing Ligand SMILES Sequences

Background on SMILES Notation

The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) is a line notation for describing the structure of chemical species using short ASCII strings [13]. SMILES strings encode molecular structures—including atoms, bonds, and molecular topology—in a form that is both human-readable and easily processed by computers [14]. They provide a compact and standardized representation, ensuring consistency across different databases and computational tools, which is vital for large-scale cheminformatics and machine learning applications [13] [14].

Protocol: From SMILES to Ligand Representation

Purpose: To convert the SMILES string of a ligand into a numerical representation that encodes its molecular properties for subsequent interaction learning with the protein.

Input: A valid SMILES string (e.g., CCO for ethanol).

Software Requirements: Python environment with the transformers library and a pre-trained MolFormer model [5].

Input Validation and Standardization:

- Receive the ligand SMILES string as input.

- Optional but Recommended: Generate a canonical SMILES string using a tool like RDKit to ensure a standardized representation, which minimizes variability arising from different valid SMILES notations for the same molecule [13].

Feature Extraction via Pre-trained Model:

- Load the pre-trained MolFormer model and its associated tokenizer [5].

- Tokenize the input SMILES string. This step converts the character sequence into a sequence of numerical tokens understood by the model.

- Feed the tokenized sequence into the MolFormer model.

- Extract the output embeddings from the model. These embeddings constitute the final ligand representation, which captures the essential molecular features derived from the SMILES sequence [5].

Output: A high-dimensional vector (or set of vectors) representing the ligand's molecular characteristics.

Processing Protein Structures

Protocol: From Protein Structure to Graph Representation

Purpose: To convert the protein's atomic coordinates and sequence into a structured graph that encapsulates its spatial and biochemical context. Inputs: Protein data file (e.g., PDB format) containing 3D atomic coordinates, and the protein's amino acid sequence. Software Requirements: Python environment with DSSP and deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch).

Sequence Feature Extraction:

Structural Feature Extraction:

- Process the protein's 3D structure file with DSSP (Dictionary of Secondary Structure) to compute structure-based features [5].

- Extract features such as secondary structure, relative solvent accessibility, and dihedral angles for each residue.

Feature Integration and Graph Construction:

- Concatenate the Ankh sequence embeddings and DSSP structural features for each residue to form a comprehensive protein-DSSP embedding [5].

- Graph Conversion: Represent the protein structure as a graph where:

- Nodes: Represent amino acid residues.

- Node Features: The combined protein-DSSP embedding is added to spatial features (angles, distances, directions) derived from the atomic coordinates [5].

- Edges: Connect residues based on spatial proximity or sequence adjacency.

- Edge Features: Include spatial relationships such as directions, rotations, and distances between residues [5].

Output: A protein graph where nodes contain rich, multi-modal feature vectors, and edges represent spatial relationships.

Integrated Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the complete input processing and prediction pipeline of LABind.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and resources for implementing the LABind input processing pipeline.

| Item Name | Type/Format | Function in Input Processing |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES String | Line Notation (ASCII) | Serves as the primary, human-readable input describing the 2D molecular structure of the ligand [13] [14]. |

| MolFormer | Pre-trained Language Model | Converts the SMILES string into a numerical representation, capturing underlying molecular properties and features [5]. |

| Protein Structure File | PDB Format File | Provides the experimentally determined or predicted 3D atomic coordinates of the protein receptor [5]. |

| Ankh | Pre-trained Protein Language Model | Generates evolutionary and biochemical feature embeddings from the protein's amino acid sequence alone [5]. |

| DSSP | Software Tool | Analyzes the protein structure to compute key structural features such as secondary structure and solvent accessibility [5]. |

| Graph Transformer | Deep Learning Architecture | Operates on the protein graph to capture complex, long-range binding patterns within the protein's spatial context [5]. |

| Cross-Attention Mechanism | Neural Network Layer | Enables the model to learn the specific interactions between the processed protein graph and ligand representations [5]. |

| Griselimycin | Griselimycin, MF:C57H96N10O12, MW:1113.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gomisin D | Gomisin D, MF:C28H34O10, MW:530.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Performance Metrics and Data Presentation

LABind's performance was rigorously evaluated against other methods on benchmark datasets (DS1, DS2, DS3). The following metrics are particularly relevant for imbalanced classification tasks like binding site prediction, where non-binding residues far outnumber binding residues [5].

Table 2: Key performance metrics used to evaluate LABind and other binding site prediction methods [5].

| Metric | Full Name | Description and Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient | A balanced measure that accounts for true and false positives/negatives, ideal for imbalanced datasets [5]. |

| AUPR | Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve | Reflects performance across all classification thresholds, focusing on the positive class (binding sites), making it crucial for imbalanced data [5]. |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve | Measures the overall ability to distinguish between binding and non-binding sites across all thresholds [5]. |

| F1 Score | F1 Score | The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single score to balance these two concerns [5]. |

| DCC | Distance to true Binding Site Center | Evaluates the accuracy of predicting the geometric center of a binding site, important for applications like docking [5]. |

Advanced Application: Protocol for Sequence-Based Prediction

Purpose: To predict protein-ligand binding sites using only protein sequence information, without an experimentally determined structure. Input: Protein amino acid sequence and ligand SMILES string. Software Requirements: ESMFold or OmegaFold for protein structure prediction, and the LABind framework.

Protein Structure Prediction:

- Input the target protein sequence into a structure prediction tool such as ESMFold or OmegaFold [5].

- Run the prediction to generate a 3D structural model of the protein.

Structure Processing and Binding Site Prediction:

- Use the predicted protein structure as the "Protein Structure" input for the standard LABind protocol detailed in Section 3.1.

- Process the ligand SMILES as described in Section 2.2.

- Run the integrated LABind model to obtain predictions for binding site residues.

Output: A set of predicted binding site residues for the given protein-ligand pair. This protocol extends LABind's applicability to proteins without solved structures, maintaining robust performance [5].

The graph transformer serves as the foundational element for processing the protein's 3D structure in ligand-aware binding site prediction. Unlike standard Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that may rely on hand-crafted aggregation functions, graph transformers utilize a purely attention-based mechanism to learn effective representations from graph-structured data directly from the data itself [15]. In the context of protein structures, the graph transformer operates on a protein graph where nodes represent amino acid residues, and edges represent spatial relationships or interactions between them. The self-attention mechanism within the graph transformer allows each residue in the protein to gather information from all other residues, weighted by their computed relevance. This enables the model to capture long-range interactions and complex binding patterns within the protein's spatial context that are critical for accurate binding site identification [5].

The cross-attention mechanism acts as the critical communication bridge between the protein and ligand informational domains. Formally, cross-attention operates by using one set of representations as a "query" to search through and aggregate information from another set of "key" and "value" representations [16]. For LABind, this mechanism enables the protein structure (query) to selectively attend to the most relevant chemical characteristics of the ligand (key and value) [5]. This process allows the model to learn the distinct binding characteristics specific to each protein-ligand pair, moving beyond static, ligand-agnostic predictions. By dynamically integrating ligand information into the protein representation, the cross-attention mechanism provides the "ligand-aware" capability that allows LABind to generalize to predicting binding sites for novel ligands not encountered during training [5] [10].

LABind Architectural Framework

The LABind architecture integrates protein and ligand information through a sophisticated pipeline that culminates in a binding site prediction. Figure 1 illustrates the end-to-end workflow and data transformations occurring within the system.

Figure 1. LABind System Workflow for Binding Site Prediction. This diagram illustrates the flow of protein structure and ligand SMILES data through their respective representation modules, integration via cross-attention, and final binding site classification.

Protein Encoding with Graph Transformers

The protein graph construction begins by converting the protein's 3D structure into a graph representation where nodes correspond to amino acid residues. The initial node features ( f_i^0 ) for residue ( i ) are created by concatenating multiple data sources [5]:

1. Sequence Embeddings: Protein sequences are processed through the Ankh protein language model to generate evolutionary and contextual residue representations [5].

2. Structural Features: DSSP-derived secondary structure and solvent accessibility features provide information about the local structural environment of each residue [5].

3. Spatial Features: Angular and distance relationships derived from atomic coordinates capture the 3D geometric arrangement of the protein structure [5].

Edge features ( e{ij} ) between residues ( i ) and ( j ) are encoded using radial basis functions applied to the distance between their Cα atoms, capturing spatial relationships: ( e{ij}^k = \exp(-\gamma(||ri - rj|| - \muk)^2) ), where ( ri ) and ( rj ) are coordinate vectors, and ( \muk ) are distance centers [17].

The graph transformer processes this protein graph through multiple layers of self-attention. In each layer ( l ), the node features ( f_i^l ) are updated using multi-head attention mechanism [17]:

[ \begin{align} qi^h, ki^h, vi^h &= \text{Linear}(fi^l) \ a{ij}^h &= \text{softmax}j\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{dh}} \sumk q{ik}^h \cdot k{jk}^h \cdot b{ijk}^h\right) \ oi^h &= \sumj a{ij}^h vj^h \ fi^{l+1} &= \text{LayerNorm}(\text{FFN}(\text{Concat}h(oi^h)) + f_i^l) \end{align} ]

Where ( b{ij}^h ) represents projected edge features, and ( dh ) is the dimension of each attention head. This architecture allows the model to capture both local binding patterns and long-range allosteric interactions that influence binding site formation [5].

Ligand Representation Learning

Ligand information is encoded from their Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings using the MolFormer molecular language model [5]. This pre-trained transformer model processes the SMILES string to generate a comprehensive molecular representation that captures atomic properties, functional groups, and overall molecular characteristics relevant to protein-ligand interactions. The resulting ligand embedding serves as a queryable memory for the cross-attention mechanism, enabling the protein structure to selectively attend to chemically relevant ligand features during the binding site prediction process.

Interaction Attention Module

The cross-attention module forms the core innovation that enables ligand-aware binding site prediction. In this module, the protein residue representations serve as queries (( Q )), while the ligand representation provides keys (( K )) and values (( V )) [5] [18]. The attention mechanism is computed as [16]:

[ \begin{align} Q &= X{\text{protein}}WQ \ K &= X{\text{ligand}}WK \ V &= X{\text{ligand}}WV \ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) &= \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V \end{align} ]

This formulation creates virtual edges between all protein graph nodes and the ligand representation, allowing each residue to compute a relevance score with the specific ligand [18]. The cross-attention weights ( \alpha_{ij} ) represent the binding relevance between protein residue ( i ) and ligand characteristic ( j ), enabling the model to highlight protein regions that are chemically complementary to the query ligand. The output is a ligand-refined protein representation where residue embeddings now incorporate specific information about their potential interaction with the given ligand.

Binding Site Prediction

The final component of the LABind architecture is a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) classifier that processes the ligand-refined residue representations to predict binding probabilities [5]. Each residue representation output from the cross-attention module is independently passed through the MLP to generate a binary classification (binding vs. non-binding residue). The model is trained using standard binary cross-entropy loss, with binding sites defined as residues located within a specific distance threshold from the ligand in experimentally determined structures [5].

Performance Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking

Table 1 summarizes LABind's performance across multiple benchmark datasets and metrics compared to state-of-the-art methods, demonstrating its consistent superiority across diverse evaluation criteria [5].

Table 1: LABind Performance on Benchmark Datasets

| Dataset | MCC | AUPR | AUC | F1 Score | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | 0.428 | 0.662 | 0.954 | 0.594 | 0.613 | 0.576 |

| DS2 | 0.397 | 0.631 | 0.949 | 0.566 | 0.589 | 0.545 |

| DS3 | 0.415 | 0.654 | 0.955 | 0.584 | 0.612 | 0.559 |

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) are particularly informative metrics given the highly imbalanced nature of binding site prediction, where non-binding residues significantly outnumber binding residues [5]. LABind's strong performance across these metrics demonstrates its robustness in handling this class imbalance.

Comparison with Alternative Architectures

Table 2 compares the core architectural approaches of LABind with other computational methods for binding site prediction, highlighting its unique ligand-aware capabilities.

Table 2: Architectural Comparison of Protein-Ligand Binding Prediction Methods

| Method | Architecture | Ligand Awareness | Generalization to Unseen Ligands | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LABind | Graph Transformer + Cross-Attention | Explicit during training & prediction | Yes | Cross-attention for protein-ligand interaction learning |

| PLAGCA | GNN + Cross-Attention | Explicit during training & prediction | Yes | Graph cross-attention for local 3D pocket features [19] |

| DeepTGIN | Transformer + GIN | Implicit (via affinity prediction) | Limited | Hybrid multimodal architecture [20] |

| Single-ligand methods | Various (GNNs, CNNs) | Rigid (model-specific) | No | Specialization for specific ligands [5] |

| Ligand-agnostic methods | Various (GNNs, CNNs) | None | Not applicable | Focus on protein structure only [5] |

LABind's cross-attention architecture provides distinct advantages over ligand-agnostic methods like P2Rank and DeepSurf, which rely solely on protein structural features without considering specific ligand properties [5]. Similarly, LABind outperforms single-ligand specialized methods, which require training separate models for different ligand types and cannot generalize to novel ligands [5]. The graph cross-attention mechanism in PLAGCA shows similar ligand-aware advantages, demonstrating the emerging pattern that explicit protein-ligand interaction modeling through attention provides significant performance benefits [19].

Experimental Protocols

Data Preprocessing and Preparation

Protocol 1: Protein-Ligand Complex Data Curation

- Data Source Selection: Obtain protein-ligand complexes from public databases such as PDBBind [20] or curated benchmark sets (DS1, DS2, DS3) [5].

- Structure Preprocessing:

- Remove water molecules and non-relevant ions from protein structures

- Separate protein chains and ligand molecules

- Standardize residue naming conventions and protonation states

- Binding Site Annotation:

- Define binding residues as those having any atom within 4Ã… of any ligand atom

- Create binary labels for each residue (1: binding, 0: non-binding)

- Dataset Splitting:

- Partition data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 80%/10%/10%)

- Ensure no significant sequence similarity between splits (typically <30% identity)

Protocol 2: Protein Graph Construction

- Node Definition:

- Represent each amino acid residue as a node using its Cα atom coordinates

- Extract node features: Ankh embeddings (1024D) + DSSP features (secondary structure, solvent accessibility) + spatial features (angles, distances) [5]

- Edge Definition:

- Graph Validation:

- Verify graph connectivity matches protein topology

- Ensure all binding residues are included in the graph

Model Training and Evaluation

Protocol 3: LABind Model Training

- Initialization:

- Training Configuration:

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate of 1e-4 and weight decay of 1e-5

- Implement gradient clipping with maximum norm of 1.0

- Use binary cross-entropy loss with class weighting to handle imbalance

- Train for 100-200 epochs with early stopping based on validation AUPR

- Regularization Strategies:

- Apply dropout (rate=0.1) to attention weights and fully connected layers

- Use layer normalization after each transformer block

- Implement data augmentation through random rotations of protein structures

Protocol 4: Model Evaluation and Benchmarking

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Compute per-residue predictions across test dataset

- Calculate AUPR, AUC, MCC, F1, precision, and recall at optimal threshold [5]

- Generate precision-recall and ROC curves for visualization

- Generalization Testing:

- Evaluate on unseen ligands not present in training data

- Test on proteins with predicted structures from ESMFold or AlphaFold

- Assess performance across different ligand types (small molecules, ions)

- Statistical Validation:

- Perform bootstrap sampling to estimate confidence intervals

- Conduct paired statistical tests against baseline methods

- Report significance levels for performance differences

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3 provides essential computational tools and resources for implementing graph transformer and cross-attention approaches for protein-ligand binding site prediction.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Graph Transformer Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application in LABind |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ankh | Protein Language Model | Generates evolutionary and contextual residue embeddings | Provides sequence representations for protein graph nodes [5] |

| MolFormer | Molecular Language Model | Encodes SMILES strings into molecular representations | Generates ligand embeddings for cross-attention [5] |

| DSSP | Structural Feature Calculator | Derives secondary structure and solvent accessibility | Provides structural features for protein graph nodes [5] |

| Fpocket | Geometry-Based Pocket Detector | Identifies potential binding pockets from protein surface | Alternative approach for benchmark comparison [17] |

| ESMFold/AlphaFold | Structure Prediction Tools | Predicts protein 3D structures from sequences | Enables application to proteins without experimental structures [5] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Processes molecular structures and descriptors | Handles ligand preprocessing and feature calculation |

| PyTorch Geometric | Graph Neural Network Library | Implements graph transformers and GNN architectures | Provides building blocks for protein graph encoder [17] |

| Ribavirin (GMP) | Ribavirin (GMP), MF:C8H12N4O5, MW:244.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 13-HPOT | 13-HPOT, CAS:28836-09-1, MF:C18H30O4, MW:310.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Architectural Variants and Optimization

Alternative Cross-Attention Formulations

The core cross-attention mechanism in LABind can be extended through several architectural variants that have demonstrated success in related domains:

Multi-Head Cross-Attention: Employ multiple parallel attention heads to capture different aspects of protein-ligand interactions simultaneously, with each head potentially specializing in different chemical interaction types (e.g., hydrophobic, electrostatic, hydrogen bonding) [16].

Graph Cross-View Attention: Implement bilateral attention patterns where protein-to-ligand and ligand-to-protein attention are computed simultaneously, creating a co-attention mechanism that mutually refines both representations [16].

Laplacian-Regularized Attention: Apply graph Laplacian smoothing to attention weights to enforce spatial coherence in binding site predictions, ensuring that adjacent residues in the protein structure have similar attention patterns where biochemically justified [16].

Implementation Optimization Strategies

Protocol 5: Computational Efficiency Optimization

- Memory Optimization:

- Use gradient checkpointing for graph transformer layers

- Implement CPU offloading for large protein graphs