Ligand Binding and Unbinding Kinetics: From Molecular Mechanisms to Drug Discovery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the dynamics of ligand binding and unbinding kinetics, a critical area in biophysics and drug discovery.

Ligand Binding and Unbinding Kinetics: From Molecular Mechanisms to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the dynamics of ligand binding and unbinding kinetics, a critical area in biophysics and drug discovery. It explores the foundational theories of molecular recognition, including induced fit and conformational selection mechanisms. The content details state-of-the-art experimental and computational methodologies for measuring kinetic parameters, addresses common challenges in data analysis and interpretation, and reviews advanced techniques for validating and predicting kinetic profiles. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to highlight how a deep understanding of binding kinetics, beyond mere affinity, is essential for optimizing drug efficacy and safety.

Molecular Recognition: Unraveling the Fundamental Mechanisms of Ligand-Target Interactions

The paradigm for understanding molecular recognition has evolved significantly from its simplistic beginnings. The concept of binding affinity, a fundamental parameter in drug design describing the strength of interaction between a molecule and its target protein, is intrinsically linked to these evolving models of recognition [1] [2]. For decades, the lock-and-key analogy dominated our understanding of how proteins and ligands interact. However, with advancements in structural biology and computational chemistry, it has become clear that this rigid model provides an incomplete picture of the dynamic process of molecular binding [1].

The limitations of the lock-and-key model became particularly evident in computational drug design, where docking programs successfully predict ligand binding poses but often fail to accurately correlate scoring functions with experimental binding affinity [1] [2]. This discrepancy highlighted a fundamental gap in our understanding of the mechanisms governing binding affinity, prompting the development of more sophisticated models that account for molecular flexibility and dynamics [1]. The induced fit and conformational selection models emerged as competing yet complementary frameworks that better reflect the reality of protein-ligand interactions, acknowledging that both partners can undergo significant structural adaptations during binding [1] [2].

This review explores the evolution of binding theory within the critical context of ligand binding and unbinding kinetics. We will examine how each theoretical framework—from lock-and-key to induced fit and conformational selection—contributes to our understanding of the dynamic process of molecular recognition, with particular emphasis on its implications for drug discovery and the accurate prediction of binding kinetics.

Historical Foundation: The Lock-and-Key Model

The first model of enzyme-substrate binding, proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, introduced the lock-and-key analogy to explain molecular recognition [1] [2]. This seminal concept suggested that the substrate possesses a shape perfectly complementary to the enzyme's catalytic site, akin to a key fitting into a lock [1]. The model implied that only substrates with precisely matching shapes could bind to the enzyme, providing valuable initial insights into the mechanisms underlying molecular specificity and selectivity [2].

The lock-and-key model was initially devised to explain how enzymes selectively recognize and bind to specific substrates or their stereoisomers, and was later extrapolated to elucidate interactions between inhibitors and enzymes, as well as protein-ligand interactions in general [1] [2]. Despite its enduring legacy as one of the most prominent paradigms in biochemistry, the model portrayed both proteins and ligands as essentially rigid structures, implying that recognition was determined solely by static steric complementarity [1].

With the advent of crystallographic analysis, significant limitations of the lock-and-key model became apparent. Experimental evidence revealed that proteins are highly flexible molecules capable of shifting their shape and topology, while ligands can adopt multiple conformations depending on their rotatable bonds [1] [2]. These observations contradicted the central tenet of the lock-and-key model, prompting the scientific community to develop more sophisticated frameworks that could account for the dynamic nature of molecular recognition.

Table 1: Core Principles and Limitations of the Lock-and-Key Model

| Aspect | Description | Modern Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Perfect steric complementarity between rigid protein and ligand [1]. | Overly simplistic view of molecular recognition [1]. |

| Molecular Flexibility | Treats both protein and ligand as static, rigid bodies [1] [2]. | Proteins and ligands are highly flexible in reality [1]. |

| Binding Mechanism | Recognition is determined purely by pre-existing shape compatibility [1]. | Recognition involves complex dynamics and mutual adaptation [1] [3]. |

| Historical Significance | Provided the first paradigm for understanding enzyme specificity [1] [2]. | Foundation for later, more dynamic models [1]. |

Modern Paradigms: Induced Fit and Conformational Selection

The Induced Fit Model

In 1958, Daniel Koshland proposed the induced fit model to address the limitations of the lock-and-key analogy [1] [2]. This model suggested that the ligand structure may not be perfectly complementary to the binding site initially, but as they interact, the protein adjusts its conformation to achieve a better fit, akin to a hand adjusting to a glove [1]. This revolutionary concept acknowledged that proteins are not static entities but dynamic structures capable of conformational changes upon ligand binding [1].

The induced fit model gained widespread acceptance as structural evidence accumulated demonstrating that proteins frequently undergo conformational rearrangements—ranging from subtle side-chain adjustments to substantial domain movements—when engaging with ligands [1] [2]. These observations aligned with the induced fit theory's central prediction that binding is a cooperative process where the ligand induces the optimal binding conformation in the protein [1]. For over half a century, this model remained the textbook explanation for molecular recognition events, significantly influencing drug discovery approaches and computational methods [1].

The model's legacy continues in modern computational frameworks. For instance, ColdstartCPI, a contemporary compound-protein interaction prediction model, is explicitly inspired by induced fit theory, treating proteins and compounds as flexible molecules to better reflect biological reality [3]. This approach demonstrates how the core principle of induced fit remains relevant in current research methodologies.

The Conformational Selection Model

In 2009, David Boehr, Ruth Nussinov, and Peter Wright proposed an alternative model known as conformational selection, which has since gained considerable traction [1] [2]. According to this model, proteins exist in an equilibrium of multiple conformational states even in the absence of ligand, and the ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes the most complementary pre-existing conformation [1]. This framework effectively reverses the sequence of events proposed by induced fit, suggesting that ligand binding does not induce a new conformation but rather shifts the equilibrium toward a pre-existing but previously minor population state [1].

The conformational selection model is particularly relevant for understanding the behavior of intrinsically disordered proteins and those with significant inherent flexibility [4]. Support for this model comes from techniques like molecular dynamics simulations and advanced spectroscopic methods, which can detect these pre-existing conformational equilibria [1]. The model provides a compelling explanation for allosteric regulation and the behavior of proteins that sample multiple states under physiological conditions [1].

The FiveFold methodology for conformation ensemble-based protein structure prediction represents a modern implementation of conformational selection principles [4]. This approach explicitly acknowledges and models the inherent conformational diversity of proteins through an ensemble-based strategy that leverages multiple prediction algorithms, moving beyond single-structure paradigms to capture the dynamic landscape of protein conformations [4].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Modern Binding Theory Paradigms

| Characteristic | Induced Fit Model | Conformational Selection Model |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed By | Daniel Koshland (1958) [1] | David Boehr, Ruth Nussinov, Peter Wright (2009) [1] |

| Sequence of Events | 1. Ligand binds → 2. Protein conformation changes [1] | 1. Protein exists in multiple states → 2. Ligand selects preferred state [1] |

| Pre-existing Conformations | Binding conformation exists only transiently or not at all before binding [1]. | All conformational states pre-exist in equilibrium before binding [1] [4]. |

| Impact on Protein Population | Stabilizes a previously unpopulated or minor conformation [1]. | Shifts equilibrium toward the bound-compatible conformation [1]. |

| Therapeutic Implications | Rational design of ligands that induce beneficial conformational changes [1]. | Targeting cryptic or alternative conformational states [4]. |

| Modern Implementation | ColdstartCPI framework for compound-protein interaction prediction [3]. | FiveFold ensemble methodology for structure prediction [4]. |

The Critical Role of Binding and Unbinding Kinetics

Binding affinity is fundamentally a kinetic parameter, determined by the ratio of association (k~on~) and dissociation (k~off~) rate constants [1] [2]. The affinity constant K~a~ and its reciprocal, the dissociation constant K~d~, are defined by the relationship K~d~ = k~off~/k~on~ [1] [2]. This relationship highlights that binding affinity reflects the stability of the protein-ligand complex at equilibrium, rather than merely the "attractiveness" or strength of interaction [1] [2].

Current computational methods for predicting binding affinity often produce unsatisfactory results that diverge by orders of magnitude from experimental values [1] [2]. This discrepancy can be attributed to two plausible reasons: inaccurate estimation of energetic factors in scoring functions, or more fundamentally, the failure to comprehensively model the biological and chemical mechanisms determining binding affinity [1] [2]. Notably, traditional models like lock-and-key, induced fit, and conformational selection primarily focus on the binding step of complex formation but do not adequately address the dissociation rate of the ligand [1] [2].

The critical importance of dissociation kinetics is exemplified by the ligand trapping mechanism, recently reported in N-myristoyltransferases and kinases, which results in a dramatic increase in binding affinity [1] [2]. In this mechanism, structural rearrangements after initial binding effectively "trap" the ligand, significantly slowing its dissociation and thereby enhancing apparent affinity [1]. This mechanism is not considered in existing computational tools for affinity prediction, highlighting a significant gap in current methodologies [1] [2].

Emerging research emphasizes that drug residence time (reciprocal of k~off~) often correlates better with therapeutic efficacy than binding affinity alone [5]. This understanding has stimulated the development of experimental and computational approaches specifically focused on measuring and predicting binding kinetic parameters [5]. Databases such as KDBI, BindingDB, KOFFI, and others now systematically collect binding kinetic data, facilitating the development of quantitative structure-kinetic relationship (QSKR) models [5].

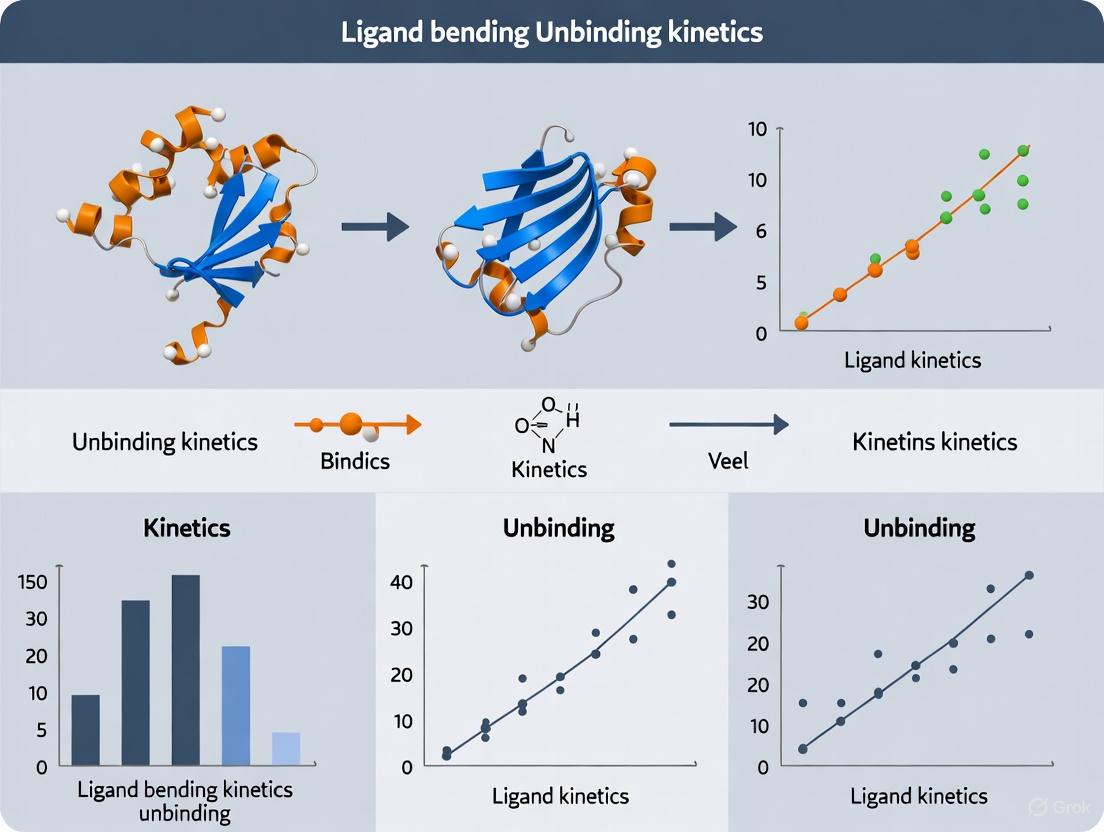

Diagram 1: Ligand binding and unbinding kinetics pathway. The diagram illustrates the dynamic equilibrium between free and bound states of protein and ligand, highlighting the critical kinetic parameters k_on and k_off that determine binding affinity. Conformational changes in the protein (induced fit or conformational selection) influence these kinetic parameters.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Techniques for Kinetic Analysis

A range of experimental techniques has been developed to measure biomolecular binding kinetic rates, primarily relying on monitoring specific signals over time during binding and dissociation processes [5]. These methods can be broadly divided into two classes: label-based and label-free assays [5].

Label-based approaches include radiometric binding assays, where ligands are tagged with radioactive isotopes to follow the time course of their binding to targets, allowing spontaneous measurement of binding kinetic rates [5]. Spectroscopy-based assays utilize fluorophore groups attached to ligands, which emit characteristic light after absorbing specific wavelengths, enabling detection of binding and dissociation processes [5]. Fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) represents one popular spectroscopy-based approach [5].

Among label-free techniques, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has emerged as one of the most widely used methods, particularly in pharmaceutical research for characterizing biomolecular binding kinetics [5]. SPR measures binding events in real-time without requiring molecular labels, providing direct information about association and dissociation rates [5].

The growing importance of binding kinetics in drug discovery is reflected in the establishment of specialized databases that systematically collect kinetic parameters [5]. These include the Kinetic Data of Biomolecular Interactions (KDBI), BindingDB, Kinetics of Featured Interactions (KOFFI), and others that provide curated experimental data for developing and validating computational models [5].

Computational Approaches and Protocols

Computational methods for predicting binding kinetics have advanced significantly, ranging from quantitative structure-kinetic relationship (QSKR) models to molecular dynamics simulations and machine learning approaches [5]. These methodologies aim to complement experimental techniques and provide high-throughput prediction of kinetic parameters [5].

The COMBINE (COMParative BINding Energy) analysis represents one computational approach that uses protein-ligand complex structures to predict binding parameters [5]. This method can be modified to incorporate multiple protein conformations by using ensemble docking, where small molecules are docked to a conformational ensemble obtained from MD simulations [5]. The interaction energy components are calculated using molecular mechanics force fields, with weights determined through partial least squares regression to predict kinetic parameters [5].

Modern machine learning frameworks like ColdstartCPI implement induced fit theory principles by treating proteins and compounds as flexible molecules during inference [3]. This approach uses pre-trained feature extraction (Mol2Vec for compounds, ProtTrans for proteins) combined with Transformer architecture to learn compound and protein features by extracting inter- and intra-molecular interaction characteristics [3]. The methodology consists of five key steps: input (SMILES strings and amino acid sequences), pre-trained feature generation, feature space unification via MLPs, Transformer module for learning flexible interactions, and final prediction using a fully connected neural network [3].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Kinetics Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Experimental Platform | Label-free measurement of biomolecular binding kinetics in real-time [5]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Computational Method | Models atomistic interactions and conformational changes over time [1] [5]. |

| ColdstartCPI Framework | Computational Model | Implements induced fit theory for predicting compound-protein interactions [3]. |

| FiveFold Methodology | Computational Tool | Ensemble-based protein structure prediction for conformational diversity [4]. |

| COMBINE Analysis | Computational Algorithm | Predicts binding parameters using interaction energy decomposition [5]. |

| MMP Analysis | Computational Approach | Matched molecular pair analysis to elucidate structural impact on kinetics [5]. |

Integrated Framework and Future Perspectives

The evolving understanding of molecular recognition suggests that induced fit and conformational selection are not mutually exclusive mechanisms but rather represent complementary aspects of a unified binding process [1]. Rather than adhering to a single model, the prevailing view acknowledges that most protein-ligand interactions likely incorporate elements of both conformational selection and induced fit, with their relative contributions varying across different systems [1].

A significant advancement in this integrated framework is the introduction of the inhibitor trapping concept, which specifically addresses the dissociation mechanism that traditional models overlook [1] [2]. When combined with established models, this concept provides a more comprehensive theoretical framework that may enable accurate determination of binding affinity [1] [2]. The trapping mechanism, observed in systems like N-myristoyltransferases and kinases, involves structural rearrangements that effectively imprison the ligand, dramatically slowing dissociation and thereby increasing binding affinity [1] [2].

Future directions in binding kinetics research point toward ensemble-based approaches that capture the full spectrum of protein conformational dynamics [4]. Methods like FiveFold, which combines predictions from multiple complementary algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D), represent promising strategies for modeling conformational ensembles rather than single static structures [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for intrinsically disordered proteins and those with significant flexibility, which comprise challenging targets for traditional structure-based drug design [4].

The expanding role of machine learning, particularly frameworks that incorporate biophysical principles like induced fit theory, offers exciting possibilities for more accurate prediction of binding kinetics [3]. As these models mature and integrate more comprehensive data from kinetic databases, they hold promise for accelerating drug discovery and enabling targeting of previously "undruggable" proteins [4] [3] [5].

Diagram 2: Unified framework of molecular recognition. This diagram integrates conformational selection, induced fit, and inhibitor trapping mechanisms into a comprehensive model of binding and unbinding kinetics, highlighting the critical role of dissociation pathways in determining binding affinity.

The evolution from lock-and-key to induced fit and conformational selection models represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of molecular recognition. This theoretical progression has been paralleled by growing recognition that binding and unbinding kinetics are critical determinants of biological function and therapeutic efficacy. The integration of these concepts into a unified framework that accounts for both association and dissociation mechanisms provides a more complete picture of the dynamics governing protein-ligand interactions.

Future advances in this field will likely come from ensemble-based approaches that capture protein conformational diversity, combined with computational methods that explicitly model the temporal dimension of binding events. As these techniques mature, they promise to enhance our ability to predict binding kinetics accurately and design therapeutics with optimized kinetic profiles, ultimately expanding the druggable proteome and enabling more effective targeting of challenging disease pathways.

For decades, Koshland's 'induced fit' hypothesis served as the predominant model for biomolecular recognition, positing that ligands induce conformational changes in proteins upon binding [6]. However, accumulating experimental evidence now supports conformational selection as a fundamental mechanism governing molecular interactions. This paradigm shift proposes that proteins exist as dynamic ensembles of pre-existing conformations, and ligands selectively bind to compatible structures, subsequently driving population shifts across the conformational landscape [6]. This framework has profound implications for understanding diverse biological processes including signaling, catalysis, gene regulation, and protein aggregation in disease contexts [6]. The conformational selection model not only redefines our fundamental understanding of molecular recognition but also opens new avenues for drug design, biomolecular engineering, and molecular evolution strategies.

Theoretical Foundation and Mechanistic Principles

Core Mechanism and Energetic Landscape

The conformational selection mechanism postulates that all functionally relevant protein conformations pre-exist in dynamic equilibrium, even in the absence of ligand [6]. The ligand does not induce a new structure but rather selectively binds to the complementary conformation it recognizes from this pre-existing ensemble. Following binding, the system undergoes a population shift, redistributing the conformational states toward the bound conformation [6]. This process is governed by the intrinsic dynamics of the protein's energy landscape, where conformational states interconvert through thermally activated motions [6] [7].

The theoretical basis for conformational dynamics lies in energy landscape perspectives originally developed for protein folding [7]. Proteins in their native state sample multiple higher-energy, excited-state conformations that dynamically exchange with the lowest-energy ground-state conformation observed in crystal structures [7]. These higher-energy states often structurally resemble the conformations observed during ligand binding or catalytic activity, demonstrating that functional conformational changes can occur intrinsically without ligand presence [7].

Temporal Ordering and Relationship to Induced Fit

A key distinguishing feature between conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms lies in the temporal ordering of binding events and conformational changes:

- In conformational selection, the conformational change occurs prior to ligand binding, where the protein transiently accesses a higher-energy state that the ligand then selects for binding [7].

- In induced fit, the conformational change occurs after ligand binding, where the ligand initially binds to the ground state conformation and subsequently induces structural rearrangements [7].

These mechanisms represent two sides of the same coin, as the temporal ordering is reversed in the binding and unbinding directions [7]. The reverse of an induced-fit binding pathway represents unbinding via conformational selection, while the reverse of a conformational-selection binding pathway involves a conformational relaxation induced by unbinding [7].

Table 1: Characteristic Features of Conformational Selection Versus Induced Fit

| Feature | Conformational Selection | Induced Fit |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Ordering | Conformational change precedes binding | Binding precedes conformational change |

| Nature of Conformational Change | Conformational excitation to higher-energy state | Conformational relaxation to lower-energy state |

| Ligand Role | Selects pre-existing conformation | Induces new conformation |

| Protein Dynamics | Intrinsic motions govern availability | Binding-driven motions dominate |

| Unbinding Mechanism | Conformational relaxation after unbinding | Conformational selection for unbinding |

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Considerations

The distinction between conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms requires examination of binding kinetics and thermodynamics. For small ligand molecules, conformational selection becomes plausible when transition times for ligand binding and unbinding are small compared to the dwell times of proteins in different conformations [7]. This separation of timescales leads to a decoupling and clear temporal ordering of binding/unbinding events and conformational changes [7].

For larger ligand molecules such as peptides, conformational changes and binding events can be intricately coupled, exhibiting aspects of both conformational selection and induced fit processes in both binding and unbinding directions [7]. In these cases, the clear temporal ordering may be obscured, requiring more sophisticated analytical approaches to decipher the dominant mechanism.

Quantitative Analysis and Experimental Evidence

Key Experimental Findings Across Biological Systems

Conformational selection has been experimentally demonstrated for diverse biomolecular interactions including protein-ligand, protein-protein, protein-DNA, protein-RNA, and RNA-ligand systems [6]. Several landmark studies have provided compelling evidence through advanced biophysical techniques:

- Rhodopsin kinase binding to recoverin: Direct demonstration of exclusive conformational selection in protein-protein recognition through dynamic pathway analysis, showing that recoverin populates a minor conformation in solution that exposes a hydrophobic binding pocket before binding occurs [8].

- Adenylate kinase dynamics: Experimental support from X-ray crystallography, NMR, and single-molecule fluorescence shows that this enzyme fluctuates between open and closed states in the absence of ligand, demonstrating intrinsic conformational dynamics [6].

- Dihydrofolate reductase catalysis: Studies suggest that every functional intermediate fluctuates into higher-energy conformations structurally similar to adjacent complexes in the catalytic cycle, indicating conformational selection in enzymatic mechanisms [6].

- Antibody-antigen recognition: Conformational adaptation has been observed in peptide-antibody interactions, where pre-existing conformations are selected during recognition events [6].

Quantitative Parameters from Experimental Systems

Table 2: Experimental Kinetic and Thermodynamic Parameters in Conformational Selection

| Protein System | Experimental Technique | Key Parameters | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlnBP (Glutamine-binding protein) | smFRET, SPR, ITC, MD simulations | Conformational exchange <100 ns; Binding affinity (sub-μM for Gln) | Compatibility with induced fit; Limited evidence for conformational selection [9] |

| Recoverin | NMR, Stopped-flow kinetics, ITC | Low population of binding-competent state; Protein dynamics limit binding rate | Exclusive conformational selection pathway [8] |

| SARS-CoV-2 Spike variants | MD simulations, Markov state models, HDX-MS | Enhanced stability in BA.2.75; Variant-specific conformational distributions | Mutation-induced modulation of conformational landscapes [10] |

| DNA Hydrogel | Kinetic analysis | Tunable response kinetics via crosslink stability | Exploitation of conformational selection for material control [11] |

Methodological Approaches for Studying Conformational Selection

Experimental Techniques and Protocols

Dissecting conformational selection mechanisms requires specialized methodologies capable of detecting low-population states and their exchange kinetics:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Advanced NMR methods including relaxation dispersion, residual dipolar coupling, and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement can detect excited-state conformations and measure their exchange rates on microsecond to millisecond timescales [6] [7]. These techniques provide atomic-resolution information about low-population states and their dynamics.

- Single-Molecule Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET): This technique enables direct observation of individual molecules sampling different conformational states, allowing characterization of heterogeneous populations and dynamics without ensemble averaging [7] [9]. Critical considerations include dye selection, labeling efficiency, and photon-limited time resolution.

- Stopped-Flow Kinetics: Rapid mixing experiments under pseudo-first-order conditions provide relaxation rates that can distinguish between conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms based on concentration dependence [7]. Global analysis of multiple ligand concentrations is essential for unambiguous interpretation.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations and Markov State Models (MSMs): Computational approaches can simulate conformational landscapes and identify functionally relevant states [10]. MSMs built from extensive simulations can quantify transition probabilities between states and predict binding pathways [10].

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Provides thermodynamic parameters (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS) that can support mechanistic interpretations when combined with kinetic data [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for Conformational Selection Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Conformational Selection

| Reagent/Technique | Function in Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins ((^{15})N, (^{13})C) | Enables advanced NMR experiments | Detection of low-population states; Measurement of exchange kinetics [6] |

| Site-Specific Fluorophore Labeling (e.g., Cy3/Cy5 pairs) | smFRET studies of conformational dynamics | Single-molecule observation of state interconversion [7] [9] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensors | Measurement of binding kinetics without labels | Determination of binding and dissociation rates [9] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulation of conformational ensembles | Atomistic modeling of energy landscapes and transitions [10] |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) | Probing protein dynamics and allostery | Mapping conformational changes and allosteric networks [10] |

Biological Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Role in Cellular Signaling and Regulation

Conformational selection provides a fundamental mechanism for regulating cellular processes through dynamic population shifts. In signaling pathways, the pre-existing equilibrium between conformational states allows rapid response to environmental changes or ligand availability without requiring slow structural rearrangements [6]. This enables efficient signal transduction and allosteric regulation, where binding events at one site influence protein activity at distant sites through population redistribution [6] [10].

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein exemplifies how conformational dynamics impact biological function. Omicron variants BA.2, BA.2.75, and XBB.1 exhibit unique conformational dynamic signatures and specific distributions of conformational states despite considerable structural similarities [10]. These variant-sensitive dynamics influence host receptor binding, immune evasion, and potentially transmissibility.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomaterial Design

The conformational selection framework has transformative potential for therapeutic development:

- Drug Design Strategies: Understanding conformational equilibria enables targeting of specific conformational states with therapeutics. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting allosteric sites and designing drugs that modulate protein function by stabilizing inactive conformations [6] [10].

- Biomaterial Engineering: The conformational selection mechanism has been exploited to control response kinetics in smart DNA hydrogels by modulating thermodynamic stability of crosslinks [11]. This demonstrates the potential for engineering materials with precisely tunable dynamic properties.

- Allosteric Drug Development: Comprehensive cryptic pocket screening using conformational ensembles enables identification of novel allosteric binding sites that emerge through variant-sensitive conformational adaptability [10]. These sites offer opportunities for targeting proteins that lack conventional binding pockets.

Visualizing Conformational Selection Pathways and Experimental Approaches

Conceptual Workflow for Mechanism Discrimination

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational approach required to distinguish conformational selection from induced fit mechanisms:

Kinetic Pathways in Molecular Recognition

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental pathways for conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms, highlighting their temporal ordering and relationship:

Conformational selection represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of biomolecular recognition, moving beyond the static structural view to a dynamic ensemble perspective. This framework provides powerful insights into the mechanisms governing diverse biological processes, from enzymatic catalysis to allosteric regulation and protein-protein interactions. The temporal ordering of conformational changes prior to binding events distinguishes this mechanism from induced fit and highlights the importance of intrinsic protein dynamics in molecular recognition.

Advanced experimental and computational approaches have enabled researchers to characterize conformational ensembles and quantify population shifts, providing compelling evidence for conformational selection across biological systems. This paradigm has significant implications for therapeutic development, particularly in targeting allosteric sites and designing drugs that modulate protein function through population-shift mechanisms. As methodologies continue to advance, further elucidating the intricate relationship between conformational dynamics and biological function will undoubtedly yield new insights and opportunities for intervention in disease processes.

In conventional drug discovery, the optimization of drug-target interactions has historically relied on thermodynamic parameters such as the dissociation constant (Kd), inhibition constant (Ki), and half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) [12]. These metrics, measured at equilibrium, provide valuable insights into binding affinity but offer an incomplete picture of dynamic drug behavior in living systems [13] [14]. The translational challenge of converting in vitro potency to in vivo efficacy remains significant, with insufficient efficacy contributing to approximately 66% of drug failures in Phase II and III clinical trials [12].

The dynamic nature of physiological systems demands a more comprehensive understanding of drug-target interactions [15]. Binding kinetics, specifically the association rate (kon) and dissociation rate (koff), along with their relationship to residence time (RT), provide crucial insights into the temporal dimension of pharmacodynamics [12]. Residence time, defined as the reciprocal of koff (RT = 1/koff), represents the mean lifetime of the drug-target complex [13] [14]. A prolonged residence time often correlates with sustained pharmacological activity, potentially enabling lower dosing frequencies and improved therapeutic windows [15] [13]. This review examines the critical link between binding kinetics and drug efficacy, exploring the molecular mechanisms, measurement methodologies, and strategic implementation of kinetic parameters in modern drug discovery.

Fundamental Concepts of Binding Kinetics

Kinetic Parameters and Their Interrelationships

The interaction between a drug (L) and its target (R) can be represented by the fundamental equation: L + R ⇌ LR, where kon is the association rate constant and koff is the dissociation rate constant [14]. The dissociation constant (Kd) is determined by the ratio Kd = koff/kon, representing the concentration of drug required to occupy 50% of receptors at equilibrium [12] [14]. While Kd reflects binding affinity under equilibrium conditions, it does not reveal the temporal dynamics of the interaction—how quickly the complex forms and how long it persists [13].

Residence time (RT), the reciprocal of koff, quantitatively measures the lifetime of the drug-target complex and has emerged as a critical parameter for predicting duration of pharmacological effect in vivo [13] [12]. Interestingly, the upper limit of kon is constrained by diffusion rates under physiological conditions (approximately 10â¹ Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹), and kon is influenced by ligand concentration, whereas koff is concentration-independent [12]. This independence makes koff, and consequently residence time, particularly valuable parameters for predicting in vivo behavior where local drug concentrations fluctuate due to ADME processes [12].

Molecular Models of Ligand Binding

Three primary models describe the mechanistic nature of ligand-receptor interactions, each with distinct implications for binding kinetics:

Lock-and-Key Model: This simplest model conceptualizes binding as a single-step process where the ligand (key) fits precisely into the receptor's binding pocket (lock) through steric and electronic complementarity [12]. The residence time is simply the reciprocal of koff [12].

Induced-Fit Model: Introduced by Koshland, this model proposes that initial ligand binding induces conformational changes in the receptor, leading to a stabilized complex (LR*) [12]. This multi-step mechanism introduces additional kinetic steps, with residence time represented by the equation: RT = (k₂ + k₃ + k₄)/(k₂ × k₄), where k₂ represents dissociation of the initial complex, k₃ the transition to the active conformation, and k₄ dissociation of the final complex [12].

Conformational Selection Model: This model posits that receptors exist in an equilibrium of conformations before ligand binding, with ligands selectively stabilizing pre-existing active (R) or inactive (R) states [12]. Within this framework, residence time is defined as the inverse of the dissociation rate constant (k₆) governing the disassembly of the active complex (LR) [12].

In reality, these models are interconnected, with most systems exhibiting elements of both conformational selection and induced-fit mechanisms [12].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Drug-Target Binding Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Relationship to Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate Constant | kâ‚’â‚™ | Speed at which drug binds to target | Faster kon may lead to rapid target engagement |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | kâ‚’ff | Speed at which drug leaves target | Slower kâ‚’ff prolongs target occupancy |

| Residence Time | RT | Mean lifetime of drug-target complex | RT = 1/kâ‚’ff; longer RT often correlates with sustained efficacy |

| Dissociation Constant | Kd | Drug concentration for 50% target occupancy | Kd = kâ‚’ff/kâ‚’â‚™; reflects affinity but not duration |

| Kinetic Selectivity | - | Differential kâ‚’ff for on-target vs off-target | Enables improved therapeutic window |

The Energy Landscape of Drug-Target Interactions

The formation and breakdown of drug-target complexes can be visualized through reaction coordinate diagrams that map the energy changes during binding [13]. Several key principles emerge from this perspective:

- Transition state stability significantly influences koff, yet transition states are short-lived and difficult to characterize structurally [13].

- Compounds can bind to different targets with identical thermodynamic affinity but markedly different kinetic profiles, enabling kinetic selectivity [13].

- A drug with a slow association rate will always have a slow dissociation rate, but a drug with a slow dissociation rate may or may not bind rapidly [13].

The concept of an "energy cage" illustrates how proteins can create steric hindrance through conformational changes (e.g., flap-closing mechanisms) that physically trap ligands, requiring substantial energy to overcome these barriers for dissociation [12].

Diagram 1: Multi-step binding kinetics pathway (55 characters)

Experimental Measurement of Binding Kinetics

High-Throughput Kinetic Assays

Advancements in screening technologies have enabled robust measurement of binding kinetics in high-throughput formats, facilitating early incorporation of kinetic parameters in drug discovery [16]. Key methodologies include:

TR-FRET Kinetic Probe Competition (kPCA): This method detects time-resolved FRET between a lanthanide-based donor fluorophore linked to the target and an acceptor dye conjugated to a tracer compound [16]. After characterizing tracer binding kinetics, unlabeled compounds are screened competitively, with binding parameters derived by fitting signal curves to mathematical models [16]. This approach has been successfully applied to profile 270 kinase inhibitors across 40 cancer drug targets, generating 3,230 interaction datasets [16].

Jump Dilution Catalytic Assays: This HTS-compatible method monitors recovery of kinase activity as drugs dissociate from preformed inhibitor-kinase complexes [17]. Using a universal, homogenous detection method (Transcreener ADP2 Kinase assay), researchers can determine koff values without labeled ligands, with compatibility across fluorescence polarization, fluorescence intensity, and TR-FRET detection modes [17].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Measuring Binding Kinetics

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TR-FRET kPCA | Competitive displacement of fluorescent tracer monitored via FRET | High | Kinase inhibitor profiling, selectivity screening |

| Jump Dilution | Catalytic activity recovery after rapid dissociation | High | Kinase drug discovery, compound prioritization |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | Biosensor detection of binding mass changes | Medium | Fragment screening, mechanism studies |

| Steered MD Simulations | Computational force application to induce dissociation | Low (computational) | Atomic-level pathway analysis, hotspot identification |

Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Binding Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Kinetic Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Tracers | Alexa 647-labeled kinase tracers | Compete with test compounds for binding; generate FRET signal |

| Detection Systems | Streptavidin-Terbium (Cisbio) | TR-FRET donor for high-sensitivity detection |

| Purified Targets | Biotinylated kinases (Carna Biosciences) | Immobilization-ready protein for binding studies |

| Assay Platforms | Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) | Measure target engagement in intact cells/tissues |

| Enzyme Systems | Transcreener ADP2 Kinase Assay | Monitor kinase activity recovery in jump dilution |

Experimental Workflow: TR-FRET kPCA

A detailed TR-FRET kPCA protocol for kinase inhibitors includes the following steps [16]:

Assay Plate Preparation: Dispense 5 μL of fluorescent tracer with varying concentrations of competitive molecule into 384-well microplates.

Reaction Initiation: Add 5 μL of terbium-labeled kinase using an automated injector system (e.g., PHERAstar FS) to start the reaction.

Signal Monitoring: Continuously monitor TR-FRET signals using specific instrument settings (laser excitation, 5 flashes, 100 μs integration start, 400 μs integration time).

Data Collection: Perform kinetic reads in octants with 41 cycles at 10-second intervals for approximately 7 minutes total duration.

Parameter Calculation: Fit resulting signal curves to appropriate mathematical models to derive kon and koff values for unlabeled compounds.

Diagram 2: TR-FRET binding kinetics workflow (49 characters)

Computational Approaches and Molecular Dynamics

Computational methods have become indispensable for studying binding kinetics, providing atomic-level insights difficult to obtain experimentally [18] [14].

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) and the Bell-Evans Model

SMD simulations apply external forces to accelerate ligand dissociation, generating data for predicting absolute residence times through the Bell-Evans model [14]. This approach relates the unbinding force (FR) to kinetic parameters through the equation:

FR = (kBT/xb) × ln(F'xb/(kB T koff))

where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, xb is the reaction coordinate, and F' is the loading rate [14]. Applied to GPCR targets like the A2A adenosine receptor, this method has predicted residence times on the timescale of seconds, though absolute values may differ from experimental measurements, highlighting areas for methodological refinement [14].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Hypersound-accelerated MD uses high-frequency ultrasound perturbation to accelerate slow biomolecular processes [19]. In CDK2-inhibitor binding studies, this method increased binding event observation by up to 10-20 times compared to conventional MD, enabling identification of multiple conformational pathways and energy barriers [19]. These simulations revealed that ligands adopt energetically unstable configurations when entering binding pockets or during internal rearrangements, with varying transition state positions and heights depending on the pathway [19].

Advanced Sampling Algorithms including weighted ensemble methods, milestoning, and Markov state models help overcome the timescale limitations of conventional MD simulations [14]. These approaches have been particularly valuable for studying complex processes like allosteric modulation and conformational selection in GPCRs and kinases [18] [14].

Residence Time in Clinical Translation and Drug Design

Correlating Kinetic Parameters with Clinical Outcomes

Retrospective analysis of kinase inhibitors at different development stages reveals a striking pattern: compounds further in clinical development show greater frequency of slow-dissociating interactions (characterized by high negative decadic off-rate logarithm) [16]. Interestingly, association rates show minimal difference between preclinical compounds and approved drugs, suggesting that prolonged target occupancy (rather than rapid binding) better predicts clinical success [16].

For antibacterial agents targeting bacterial enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI), residence time directly correlated with in vivo efficacy and served as a better indicator of preclinical antibacterial activity than thermodynamic affinity [13]. Similarly, in kinase drug discovery, the kinetic selectivity profile—differential koff values for on-target versus off-target kinases—can significantly influence therapeutic windows and safety profiles [16] [13].

Structure-Kinetic Relationships (SKRs)

Understanding the molecular determinants of residence time enables rational design of compounds with optimized kinetic profiles [13]. Key mechanisms include:

- Slow Conformational Changes: In FabI inhibitors, residence time correlates with ordering of the substrate binding loop, with hydrophobic substituents increasing residence time through ground state stabilization [13].

- Reversible Covalent Inhibition: Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitors like acalabrutinib achieve prolonged residence through reversible covalent binding, with steric hindrance of α-proton abstraction modulating dissociation rates [13].

- Gating Mechanisms: For purine nucleoside phosphorylase inhibitors, a gating mechanism involving rotation of Val260 controls ligand dissociation, with residence times of approximately 12 minutes at 37°C [13].

- Allosteric Trapping: GPCR antagonists like tiotropium achieve remarkably long residence times (>39 hours) through Coulomb repulsion with Lys523 and allosteric stabilization of alternative receptor conformations [13].

The integration of binding kinetics and residence time into drug discovery represents a paradigm shift from purely affinity-based optimization to a more comprehensive understanding of drug-target interactions [15] [12]. Experimental advances in high-throughput kinetic assays and computational methods for predicting dissociation pathways provide unprecedented insight into the temporal dimension of pharmacodynamics [16] [14] [19].

The correlation between prolonged residence time and improved clinical outcomes across multiple target classes underscores the translational value of kinetic optimization [15] [16] [13]. As drug discovery continues to evolve, the strategic incorporation of structure-kinetic relationships, combined with functional validation of target engagement in physiologically relevant systems, will enhance our ability to design therapeutics with optimal efficacy, safety, and durability [20] [12]. The ongoing development of innovative experimental and computational approaches promises to further illuminate the critical link between binding kinetics and drug efficacy, ultimately improving success rates in clinical translation.

The interactions between proteins and ligands form the bedrock of cellular signaling and rational drug design. For decades, the binding affinity, quantified by the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), has been the principal metric for evaluating these interactions. However, a comprehensive understanding requires decoding the full energy landscape, which encompasses both the thermodynamic stability of the bound state and the kinetic rates of association and dissociation. This whitepaper delves into the core principles governing protein-ligand binding pathways, highlighting the critical interplay between thermodynamics and kinetics. We explore innovative experimental and computational methodologies that are pushing the boundaries of our ability to measure these parameters, even in complex biological environments like tissue sections. Furthermore, we provide a detailed overview of the scientist's toolkit, including structured protocols and essential reagents, to equip researchers with the practical knowledge to investigate these fundamental processes.

Protein-ligand binding is not a simple static association but a dynamic process governed by an underlying energy landscape. This landscape defines all possible states of the system—from the unbound partners to the final complex—and the pathways connecting them.

- Thermodynamics describes the energetic balance between the bound and unbound states, defining the overall affinity. It answers the question: "How stable is the final complex?"

- Kinetics describes the rates and pathways of the transition between these states. It answers the question: "How quickly does the complex form and how long does it last?"

Historically, the binding affinity (Kd) was assumed to be the primary indicator of a drug's efficacy in vivo. However, recent research has established that the kinetics of binding, particularly the drug-target residence time (tr = 1/koff), can be an equally important or even superior predictor [21]. A drug with a long residence time can maintain pharmacological effects even after its systemic concentration has dropped, potentially increasing therapeutic efficacy and selectivity [21]. Understanding the molecular features that govern the heights and depths of the energy landscape is therefore central to the rational control of drug action.

Core Principles: Thermodynamics vs. Kinetics

Thermodynamics: The Drive for Equilibrium

Thermodynamics captures the balance of energies that determine the population of bound versus unbound states at equilibrium. The fundamental metric is the Gibbs Free Energy of binding (ΔGbind), which is directly related to the experimentally measurable dissociation constant (Kd):

Where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature. A negative ΔGbind (or a low Kd value) indicates a spontaneous binding reaction and a high-affinity interaction [21].

The binding free energy can be decomposed into enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (-TΔS) components:

- Enthalpy (ΔH) arises from the formation and breaking of specific molecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces, between the protein, ligand, and solvent.

- Entropy (-TΔS) reflects changes in the disorder of the system, often dominated by the displacement of ordered water molecules from the binding pocket (which increases entropy) versus the restriction of rotational and translational freedom upon binding (which decreases entropy).

Kinetics: The Speed of Association and Dissociation

While thermodynamics defines the endpoints, kinetics describes the journey between them. The simple bimolecular binding process is represented as:

The association rate constant (kon) and the dissociation rate constant (koff) quantify the speed of complex formation and breakdown, respectively [21]. These kinetic parameters are governed by the transition state (TS), the highest-energy, ephemeral configuration along the reaction pathway.

- The free energy barrier for association (ΔG‡on) determines kon.

- The free energy barrier for dissociation (ΔG‡off) determines koff.

The critical link between kinetics and thermodynamics is given by the relationship:

This equation reveals that the same affinity (Kd) can be achieved through vastly different kinetic mechanisms: a high-affinity interaction could result from a fast kon and a slow koff, or a slow kon and an even slower koff [21]. This distinction has profound implications for drug action, as these different scenarios will lead to different in vivo behaviors.

Table 1: Key Parameters Defining the Protein-Ligand Energy Landscape

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Determines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Constant | Kd | [P][L]/[PL] at equilibrium | Affinity: The concentration of ligand needed for half-maximal binding. |

| Gibbs Free Energy | ΔGbind | -RT ln(1/Kd) | Thermodynamic drive: The overall stability of the complex. |

| Association Rate Constant | kon | Rate of complex formation | Binding speed: How quickly the ligand finds and binds the protein. |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | koff | Rate of complex breakdown | Residence time: How long the ligand remains bound (tr = 1/koff). |

Figure 1: Free Energy Profile of Ligand Binding. The diagram illustrates the energy barriers for association (ΔG‡on) and dissociation (ΔG‡off), and the overall binding free energy (ΔGbind).

Advanced Methodologies for Probing the Energy Landscape

Experimental Innovations

Cutting-edge experimental techniques are now enabling researchers to measure binding parameters in increasingly complex and physiologically relevant contexts.

Native Mass Spectrometry with a Dilution Method A recent groundbreaking method uses native mass spectrometry (MS) to determine binding affinities for proteins of unknown concentration directly from biological tissues, bypassing the need for protein purification [22].

- Workflow: The customized workflow involves surface sampling of tissue sections with a ligand-doped solvent, serial dilution of the extracted protein-ligand mixture, and infusion ESI-MS measurement.

- Core Principle: When the protein-bound fraction remains constant upon dilution, a simplified calculation allows for the accurate determination of the dissociation constant (Kd) without prior knowledge of the protein concentration [22]. This method has been successfully applied to measure the binding affinity of drugs to fatty acid binding protein (FABP) directly in mouse liver tissue sections.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Techniques for Studying Binding

| Technique | Measured Parameters | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Kd, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS | Provides full thermodynamic profile; no labeling required. | Requires high ligand solubility; relatively large sample consumption. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Kd, kon, koff | Provides real-time kinetic data; high sensitivity. | Requires immobilization, which can alter protein behavior. |

| Native MS (Dilution Method) | Kd | Works with unpurified proteins and complex mixtures like tissues. | Potential for in-source dissociation of labile complexes. |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Kd, kon, koff | High throughput and sensitivity. | Requires fluorescent labeling or intrinsic chromophores. |

Figure 2: Native MS Workflow for Tissue Binding Studies. This diagram outlines the experimental protocol for measuring binding affinities directly from tissue samples [22].

Computational and Simulation Approaches

Computational methods provide atomic-level insights into binding pathways and energetics, complementing experimental data.

Free Energy Calculations These methods calculate the binding free energy (ΔGbind) and are crucial for in silico drug discovery.

- MM/PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area): An end-point method that estimates ΔGbind from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the bound and unbound states using implicit solvation. It offers a good balance between accuracy and computational cost [23].

- Alchemical Methods: These methods calculate free energy differences by gradually transforming the ligand between bound and unbound states via non-physical pathways. They are highly accurate but computationally demanding [24] [23].

Multiscale Simulations for Binding Kinetics Computing kinetic parameters like kon is a grand challenge. A promising approach combines:

- Brownian Dynamics (BD) Simulations: Used to simulate the long-range diffusion and formation of encounter complexes between protein and ligand. BD is efficient but often treats molecules as rigid bodies [25] [26].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Used to simulate the short-range interactions, molecular flexibility, and the final steps of complex formation from the encounter complexes generated by BD [25].

A recently developed multiscale pipeline optimizes this BD/MD combination by generating encounter complexes where the ligand is very close to the binding site, thereby reducing the required MD simulation time and enabling efficient calculation of kon values that align well with experiments [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful investigation into protein-ligand interactions relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Binding Studies |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Purified Proteins | Provides a well-defined system for initial affinity and kinetic measurements using ITC, SPR, etc. |

| Ligand Libraries | Collections of small molecules for screening and characterizing binding specificity and structure-activity relationships (SAR). |

| Native MS Sampling Solvents | Gentle, volatile buffers (e.g., ammonium acetate) that maintain non-covalent interactions during ionization for native MS [22]. |

| Biosensor Chips (e.g., for SPR) | Surfaces functionalized with carboxymethyl dextran or other groups for the immobilization of protein targets. |

| TriVersa NanoMate (or similar) | Automated robotic system for liquid extraction surface analysis (LESA) and chip-based nano-ESI, enabling direct tissue analysis [22]. |

| Cryopreserved Tissue Sections | Provides a physiologically relevant source of native proteins in their natural environment for techniques like LESA-MS [22]. |

| Mogroside II-A2 | Mogroside II-A2, MF:C42H72O14, MW:801.0 g/mol |

| Glycohyocholic acid | Glycohyocholic Acid|High Purity|For Research Use |

The paradigm for understanding and optimizing molecular recognition is shifting from a purely thermodynamic perspective to an integrated view that encompasses the full energy landscape. The synergy between thermodynamics and kinetics—between affinity and residence time—is now recognized as critical for predicting in vivo drug efficacy. The emergence of powerful techniques, such as label-free native MS for direct tissue measurement and sophisticated multiscale computational simulations, is providing unprecedented access to the parameters that define this landscape. By leveraging these advanced tools and the fundamental principles outlined in this whitepaper, researchers and drug developers can decode the complexities of binding pathways, accelerating the rational design of more effective and selective therapeutic agents.

Measuring the Clockwork: Experimental and Computational Methods for Kinetic Analysis

The dynamics of ligand binding and unbinding are fundamental to biological function and therapeutic intervention. While traditional pharmacology has long relied on equilibrium constants (such as KD, IC50) to describe ligand affinity, a paradigm shift is underway, emphasizing the critical importance of binding kinetics—the rates at which drugs associate with and dissociate from their targets. The temporal stability of the ligand-receptor complex, known as residence time (RT, calculated as 1/koff), is increasingly acknowledged as a superior predictor of in vivo drug efficacy and duration of action than affinity alone [27]. Insufficient efficacy accounts for a significant proportion of drug failures in late-stage clinical trials, driving the need for better predictive parameters early in the discovery process [27]. Direct binding assays provide the methodological foundation for quantifying the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants that underpin these kinetic profiles, offering a more nuanced understanding of drug-target interactions within the dynamic physiological environment.

This guide details the core principles, experimental methodologies, and data analysis techniques for determining these critical kinetic parameters, framing them within the broader context of modern ligand binding kinetics research for drug development.

Theoretical Foundations of Binding Kinetics

Basic Kinetic Principles and Models

The binding of a ligand (L) to a receptor (R) to form a complex (LR) is characterized by the association rate constant (kon) and dissociation rate constant (koff).

The dissociation constant (KD), a thermodynamic parameter, is defined as the ratio koff/kon. The inverse of koff defines the residence time (RT) [27]. Beyond this simple model, three primary mechanistic frameworks describe the binding process [27]:

- Lock-and-Key Model: This model posits a simple, first-order binding process where the ligand (key) fits perfectly into a pre-formed binding pocket (lock). The kinetics are defined solely by kon and koff.

- Induced-Fit Model: Here, the initial ligand binding induces a conformational change in the receptor, leading to a stabilized active complex (LR*). This model introduces additional kinetic steps and can separate the concepts of affinity (complex formation) from efficacy (conversion to the active state).

- Conformational Selection Model: This model proposes that the receptor exists in an equilibrium of conformations. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing active conformation (R*), shifting the equilibrium.

In practice, induced-fit and conformational selection are often viewed as interconnected processes, with implications for phenomena like biased agonism, where ligands stabilize specific receptor conformations that preferentially activate distinct signaling pathways [27].

Relationship Between Kinetics, Residence Time, and Efficacy

The residence time of a drug-target complex is a crucial determinant of its pharmacodynamic profile. A long RT can result in a prolonged duration of effect, even after systemic drug concentrations have declined [27]. This can be particularly advantageous for therapeutics, potentially allowing for lower dosing frequencies and improved safety profiles. The kinetic signature of a ligand (i.e., its specific kon and koff values) can also influence signaling bias at G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), as different signaling pathways may be sensitive to the duration of receptor activation [28] [27].

Experimental Methods for Measuring Binding Kinetics

A variety of experimental approaches are available to determine kon and koff, ranging from label-free single-molecule techniques to functional kinetic assays.

Label-Free Single-Molecule Techniques

Label-free methods quantify binding by directly measuring physical changes upon complex formation, eliminating potential artifacts from labels.

- Nanoaperture Optical Tweezers (NOT): This highly sensitive technique can trap a single protein using a laser and a double-nanohole aperture. Binding of a small molecule alters the protein's polarizability, which is observed as a change in the transmitted light intensity. By analyzing the fluctuations between bound and unbound states in real-time, both the association and dissociation rate constants can be determined directly from single molecules, providing a dissociation constant consistent with ensemble methods like fluorescence anisotropy [29].

Functional Kinetic Assays

These assays measure binding kinetics indirectly by monitoring a downstream functional response.

- G Protein-Coupled Inward Rectifier Potassium (GIRK) Channel Assay: This electrophysiology-based assay is used for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Receptor activation leads to the release of Gβγ subunits, which directly open GIRK channels, producing a measurable current. Upon agonist washout, the deactivation time course of the GIRK current reflects the rate of agonist dissociation (koff) from the receptor [28]. This method was used, for example, to show that agonists A77636 and tavapadon have slower dissociation rates from the dopamine D1 receptor compared to dopamine [28].

Radioligand and Fluorescence-Based Binding Assays

Traditional and widely used methods involve measuring the binding of a labeled ligand in real-time.

Time-Resolved β-arrestin Recruitment Assay: This assay uses nanoluciferase complementation to measure the recruitment of β-arrestin to an activated GPCR. The time course of signal decay after the addition of a competitive antagonist can be used to estimate the dissociation kinetics of the pre-bound agonist from the receptor-arrestin complex [28].

Kinetic Multiplex Assays: Recent advancements allow for the simultaneous assessment of multiple signaling pathways (e.g., cAMP production and β-arrestin recruitment) from the same cell population, enabling a comprehensive and kinetically resolved understanding of biased signaling [30].

Quantitative Data from Kinetic Studies

The following table summarizes kinetic parameters for a series of dopamine D1 receptor agonists, as determined by the GIRK channel and β-arrestin recruitment assays [28].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Binding Kinetics of Dopamine D1 Receptor Agonists

| Agonist | Type | koff (sâ»Â¹) from GIRK Assay | kon (Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) from GIRK Assay | Kinetic KD (pK_d) | Relative Efficacy (vs. Dopamine) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Endogenous | 0.132 ± 0.010 | 122,325 ± 37,072 | 5.969 ± 0.090 | 1.022 ± 0.022 |

| A77636 | Catechol Agonist | 0.025 ± 0.004 | 903,422 ± 78,561 | 7.556 ± 0.028 | 1.173 ± 0.119 |

| Dihydrexidine | Catechol Agonist | 0.095 ± 0.005 | 952,419 ± 174,431 | 7.002 ± 0.054 | 0.808 ± 0.044 |

| Apomorphine | Clinical Catechol | 0.090 ± 0.016 | 6,910 ± 8,354 | 4.883 ± 0.309 | 0.133 ± 0.040 |

| Tavapadon | Noncatechol Agonist | 0.027 ± 0.008 | 41,157 ± 28,432 | 6.179 ± 0.149 | 0.106 ± 0.023 |

Note: Data adapted from [28]. koff and kon are presented as Mean ± SEM. The slow koff of A77636 and tavapadon correlates with a long residence time.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Agonist koff via GIRK Channel Deactivation

This protocol outlines the steps for estimating the dissociation rate constant (koff) for a GPCR agonist using the GIRK assay in Xenopus laevis oocytes [28].

- System Preparation: Co-express the GPCR of interest (e.g., dopamine D1 receptor) with GIRK1/4 channel subunits in Xenopus oocytes.

- Electrophysiological Recording: Place the oocyte in a recording chamber and impale with two electrodes for voltage-clamp recording. Clamp the membrane potential at a level that facilitates GIRK current measurement (e.g., -70 mV).

- Agonist Application & Activation: Perfuse the oocyte with a solution containing an intermediate concentration of the agonist (ideally near its EC50) until the GIRK current reaches a steady state. This indicates a stable population of agonist-bound receptors.

- Rapid Agonist Washout: Rapidly switch the perfusion to agonist-free solution. The speed of solution exchange must be significantly faster than the expected deactivation rate (e.g., > 2 sâ»Â¹) to ensure that washout itself is not the rate-limiting step.

- Data Collection: Record the decaying GIRK current over time as the agonist dissociates and channels close.

- Data Analysis: Fit the current deactivation time course to a single or multi-exponential decay function. The decay rate constant (Ï„) provides an estimate of the agonist's koff value.

Protocol: Determining Ligand koff and kon via Single-Molecule NOT

This protocol describes how to measure binding kinetics for a single protein-ligand pair using nanoaperture optical tweezers [29].

- Sample Preparation: Purify the target protein (e.g., PR65 subunit of PP2A). Prepare a solution of the protein mixed with the small molecule ligand (e.g., ATUX-8385) at a desired concentration in an appropriate buffer.

- Instrument Setup & Trapping: Introduce the sample to the DNH chamber. Use a laser to trap a single protein molecule within the nanoaperture.

- Signal Acquisition: Monitor the transmission intensity of the laser through the aperture at a high sampling rate (e.g., 100 kHz) for an extended period (e.g., 100 seconds).

- State Discrimination: The binding and unbinding of the ligand will cause discrete shifts in the transmission intensity. For a system with two states (bound and unbound), the signal will fluctuate between two distinct levels.

- Dwell-Time Analysis: Measure the duration of time the signal spends in the "bound" state (Ï„on) and the "unbound" state (Ï„off) over many binding events.

- Kinetic Calculation:

- The dissociation rate constant, koff = 1 / Ï„on.

- The association rate constant, kon = 1 / (τoff × [L]), where [L] is the ligand concentration.

- The equilibrium dissociation constant can be cross-verified as KD = koff / kon.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Binding Assays

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| FLAG-Tagged Receptors | Recombinant receptors with an epitope tag (e.g., FLAG) for detection, purification, or surface expression quantification. | Used in live-cell surface ELISA to measure agonist-induced receptor internalization [28]. |

| GIRK1/4 Channel Subunits | Potassium channel subunits that are directly activated by Gβγ proteins released from activated GPCRs. | Provides an electrophysiological readout for GPCR activation and agonist dissociation kinetics [28]. |

| Nanoluciferase Complementation System | A split luciferase system where β-arrestin is fused to one fragment and the receptor to another; complementation upon recruitment produces light. | Enables time-resolved measurement of β-arrestin recruitment to GPCRs and subsequent complex dissociation [28]. |

| Double-Nanohole (DNH) Apertures | Fabricated nanostructures that create a highly focused laser spot for stable optical trapping of single biomolecules. | The core component of NOT for label-free, single-molecule binding studies [29]. |

| Specific Agonists/Antagonists | Well-characterized ligands with known kinetics used as reference compounds or tools to probe specific receptor states. | A77636, dihydrexidine, and tavapadon as tool compounds for D1R kinetics [28]. |

| 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rg2 | 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rg2, MF:C42H72O13, MW:785.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| urolithin M7 | urolithin M7, CAS:531512-26-2, MF:C13H8O5, MW:244.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Calculating Kinetic Parameters from Progression Curves

For assays where binding is monitored in real-time, the progression curve (signal vs. time) is fitted to appropriate equations to extract kinetic parameters. The most common is a single-phase exponential association (for binding) or dissociation (for washout).

- Dissociation Phase: After washout of free ligand, the decay in signal is fit to:

Y = (Y0 - Plateau) * exp(-koff * t) + Plateau, wherekoffis the dissociation rate constant. - Association Phase: In the presence of a fixed ligand concentration, the increase in signal is fit to:

Y = Ymax * (1 - exp(-kobs * t)), wherekobsis the observed rate constant. The underlyingkoncan be derived fromkobs = kon * [L] + koff.

Integrating Kinetic and Functional Data

Kinetic parameters gain profound meaning when correlated with functional outcomes. For instance, the slow dissociation (koff = 0.025 sâ»Â¹) of the D1 receptor agonist A77636 is associated with pronounced β-arrestin recruitment and receptor internalization, which may contribute to tolerance development. In contrast, tavapadon, despite also having a slow dissociation (koff = 0.027 sâ»Â¹), is a partial agonist and does not induce significant internalization, illustrating that both kinetic and efficacy properties combine to determine a drug's functional profile [28].

Direct binding assays for determining association and dissociation rate constants represent a cornerstone of modern kinetic research in drug discovery. Moving beyond equilibrium affinity measurements to a kinetic perspective provides deeper insights into the temporal dimension of drug action, often yielding better correlations with in vivo efficacy and therapeutic windows. As technological advancements in label-free detection, single-molecule analysis, and computational prediction continue to mature, the integration of kinetic parameters like residence time into the drug design pipeline will be essential for developing the next generation of safer, more effective therapeutics with optimized pharmacodynamic profiles.

The process of ligand binding to a biological target is not a static event but a dynamic process characterized by rates of association and dissociation. While the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) has historically been the primary parameter for assessing ligand affinity, the individual kinetic rate constants (kon and k_off) provide crucial information about the temporal dimension of drug-target interactions [31]. These binding kinetics directly influence a drug's efficacy, duration of action, and side effect profile [32]. Competition kinetics has emerged as a powerful experimental approach for quantifying the binding kinetics of unlabeled test compounds by competing them against a labeled tracer ligand [31]. This method is particularly valuable when direct measurement of test ligand binding is not feasible, enabling researchers to derive association and dissociation rates indirectly through carefully designed competition experiments.

The fundamental principle of competition kinetics relies on the law of mass action, where both the tracer and competitor ligands simultaneously bind to the same target site [33]. By monitoring how the test compound affects the association and dissociation kinetics of a tracer ligand with known binding parameters, researchers can extract kinetic information for unlabeled compounds. This approach has become increasingly popular in drug discovery for evaluating the binding kinetics of large numbers of compounds, especially for membrane-bound targets like G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) where purification for direct binding assays can be challenging [33].

Theoretical Foundations of Ligand Binding Kinetics

Basic Principles of Reversible Ligand-Target Interactions

Most therapeutic molecules interact with their targets through reversible bimolecular interactions that follow simple mass action principles. This process can be represented as:

[ R + L \mathrel{\mathop{\rightleftharpoons}{k2}^{k_1}} RL ]

where R represents the target receptor, L the ligand, RL the target-ligand complex, k1 the association rate constant (M^{-1}min^{-1}), and k2 the dissociation rate constant (min^{-1}) [31]. The association phase begins rapidly upon mixing target and ligand, then slows as binding approaches a plateau representing equilibrium or steady state. Dissociation follows an exponential decay pattern when pre-formed complexes break down over time [31].

The relationship between kinetic rate constants and the equilibrium dissociation constant is fundamental:

[ Kd = \frac{k2}{k_1} ]

This relationship provides an alternative method for determining affinity by measuring association and dissociation rates rather than traditional equilibrium binding approaches [31]. The dissociation rate constant is frequently expressed as residence time (RT = 1/k2) or half-time (t{1/2} = 0.693/k_2), which offer more intuitive measures of complex stability [31].

Quantitative Framework for Competition Kinetics

In competition kinetics, the binding of an unlabeled competitor affects the observed binding kinetics of a tracer ligand. When a competitor is present, the observed association rate (k_obs) for tracer binding becomes:

[ k{obs} = k2 + k_1 \cdot [L] ]

where k1 and k2 are the association and dissociation rate constants for the tracer, and [L] is the tracer concentration [31]. For the unlabeled competitor, the key relationship used to determine its bimolecular rate constant with the target is derived from the relative depletion rates of the competitor and a reference compound with known kinetics [34]:

[ \frac{\ln \frac{[CIP]0}{[CIP]D}}{\ln \frac{[Phenol]0}{[Phenol]D}} = \frac{k{CIP}}{k{Phenol}} ]