Ligand Pose Prediction: Mastering Molecular Docking from Foundations to AI-Driven Advances

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular docking for ligand pose prediction, a critical technique in structure-based drug design.

Ligand Pose Prediction: Mastering Molecular Docking from Foundations to AI-Driven Advances

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular docking for ligand pose prediction, a critical technique in structure-based drug design. It explores the fundamental physical principles of protein-ligand interactions, compares traditional search algorithms and scoring functions, and details modern best practices for troubleshooting and validation. A significant focus is placed on the emerging role of AI and deep learning methods, including co-folding models and deep learning pose selectors, benchmarking their performance against established physics-based docking programs. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current methodologies to enhance the accuracy and biological relevance of docking studies for virtual screening and lead optimization.

The Physical Basis of Molecular Recognition: From Lock-and-Key to Conformational Selection

Molecular docking is a cornerstone computational technique in structure-based drug design that predicts the preferred orientation and conformation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a biological target (receptor) [1]. This method has evolved from a theoretical concept in the 1980s to an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery pipelines, enabling researchers to efficiently explore molecular interactions in a simulated environment [1]. By virtually screening massive compound libraries, molecular docking significantly accelerates the identification and optimization of potential drug candidates while reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental methods alone [1] [2].

The fundamental principle underlying molecular docking is molecular complementarity - the concept that interacting molecules fit together like jigsaw pieces due to complementary shapes and chemical properties [1]. Docking simulations predict the binding pose (three-dimensional orientation and conformation) and estimate the binding affinity (strength of interaction) between ligands and their targets, typically proteins or enzymes involved in disease pathways [1] [3]. This capability makes docking particularly valuable for rational drug design, where understanding interaction mechanisms at the atomic level guides the development of more effective therapeutics.

Key Methodologies and Approaches

Molecular Docking Types and Flexibility

Docking approaches are primarily categorized based on how they handle molecular flexibility:

- Rigid Docking: Treats both the ligand and receptor as fixed structures, searching only for optimal relative orientation. This approach is computationally efficient but may overlook important interactions that require conformational adjustments [1].

- Flexible Docking: Accounts for ligand conformational flexibility, and sometimes receptor flexibility, allowing for a more accurate representation of the binding process. This approach demands significantly more computational resources but provides more biologically realistic results [1].

- Induced-Fit Docking: An advanced form of flexible docking that models conformational changes in the receptor upon ligand binding, addressing the challenge where both molecules adjust their shapes to achieve optimal complementarity [4].

Conformational Search Algorithms

Docking programs employ various algorithms to explore the vast conformational space of ligand-receptor interactions:

Systematic Methods: These exhaustively explore conformational space by systematically rotating rotatable bonds at fixed intervals. Examples include:

- Systematic Search: Used in programs like Glide and FRED, this method thoroughly explores all possible conformations but faces exponential complexity with increasing rotatable bonds [3].

- Incremental Construction: Employed by FlexX and DOCK, this approach fragments molecules into rigid components and flexible linkers, docking fragments sequentially to reduce computational complexity [3].

Stochastic Methods: These utilize random sampling and probabilistic approaches to explore conformational space:

- Monte Carlo Algorithms: Make random changes to molecular conformation, accepting or rejecting based on energy criteria and Boltzmann distribution probabilities [3].

- Genetic Algorithms (GA): Inspired by natural selection, GA encodes conformational degrees of freedom and evolves populations of poses through selection, crossover, and mutation operations based on fitness scores. Used in AutoDock and GOLD [3].

- Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm: A variant used in AutoDock that incorporates local optimization, allowing individuals to pass acquired traits to offspring [5].

Diffusion Models: Emerging deep learning approaches that generate poses through a denoising process, showing exceptional pose accuracy in benchmarks [6].

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions estimate binding affinity by evaluating protein-ligand interactions, serving as the objective function for search algorithms. The binding free energy (ΔG_binding) comprises both enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) components [3]:

ΔG_binding = ΔH - TΔS

Scoring function types include:

- Force Field-Based: Calculate energy based on molecular mechanics terms (van der Waals, electrostatics, bond stretching, angle bending)

- Empirical: Use weighted sums of interaction types fitted to experimental binding data

- Knowledge-Based: Derive potentials from statistical analyses of atom pair frequencies in known structures

- Machine Learning-Based: Train models on diverse structural and interaction data to predict binding affinities

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Molecular Docking Protocol

The following workflow outlines a comprehensive docking procedure, adaptable to various software platforms:

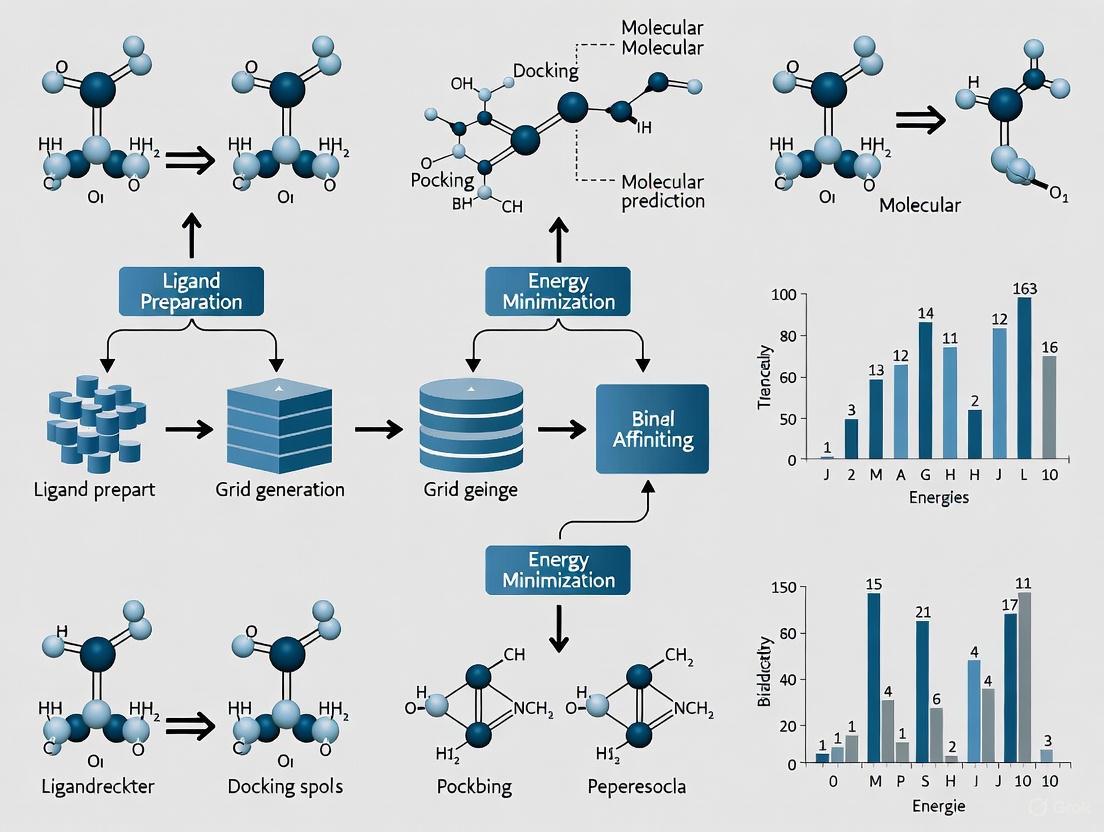

Diagram 1: Comprehensive molecular docking workflow.

Step 1: Protein Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from experimental sources (Protein Data Bank) or computational predictions (AlphaFold) [7] [5].

- Remove water molecules, cofactors, and unnecessary ions, except those critical for binding.

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states to ionizable residues at physiological pH.

- Calculate and assign partial charges using appropriate force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS).

- Model any missing residues or loops using homology modeling or database searching.

- Energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and optimize geometry.

Step 2: Ligand Preparation

- Generate 3D coordinates from 2D structures using tools like BIOVIA Draw or Avogadro [5].

- Perform geometry optimization and energy minimization using semi-empirical methods (PM3) or molecular mechanics [5].

- Identify rotatable bonds for flexible docking treatments.

- Generate multiple low-energy conformers if using rigid docking approaches.

- Assign appropriate partial charges and atom types.

Step 3: Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation

- Identify the binding site using known experimental data, cavity detection algorithms, or blind docking approaches.

- Define a grid box encompassing the binding site with sufficient margin for ligand movement.

- Common approaches include:

- Site-Specific Docking: Grid centered on known binding site with 20-30Ã… dimensions

- Blind Docking: Large grid covering entire protein surface to identify novel binding sites [5]

- Calculate energy maps for efficient scoring function evaluation during docking.

Step 4: Docking Execution and Parameter Setting

- Select appropriate search algorithm based on ligand flexibility and computational resources.

- Configure docking parameters:

- Number of docking runs and poses to generate

- Population size and number of generations (for genetic algorithms)

- Maximum number of energy evaluations

- Cluster analysis parameters for result diversity

- Execute docking simulations, typically generating 10-100 poses per ligand.

Step 5: Pose Analysis and Validation

- Visualize top-ranked poses using molecular graphics software (PyMOL, Chimera, Discovery Studio)

- Analyze specific protein-ligand interactions: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking, salt bridges

- Calculate binding energies and interaction energies for different pose clusters

- Validate results by redocking known ligands and comparing with experimental structures

- Check physical plausibility using tools like PoseBusters to identify geometric and chemical inconsistencies [6]

Advanced Protocol: Template-Based Docking (TEMPL)

For targets with known ligand complexes, template-based approaches can significantly improve accuracy:

Diagram 2: Template-based docking (TEMPL) workflow.

Application Context: This approach is particularly valuable for congeneric series or targets with abundant structural data, such as SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease [8].

Methodology Details:

- Reference Identification: Search structural databases (PDB) for complexes with similar ligands or binding sites

- Maximal Common Substructure (MCS): Use the RascalMCES algorithm to identify maximum common edge substructure between query and reference ligands [8]

- Constrained Embedding: Generate conformers using knowledge-enhanced distance geometry (ETKDGv3) with MCS atoms constrained to reference coordinates [8]

- Scoring and Ranking: Rank poses using ShapeTanimoto and ColorTanimoto scores measuring shape and feature complementarity [8]

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Docking Software Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of molecular docking methods across key metrics.

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid) | Virtual Screening Performance | Computational Speed | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Physics-Based | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina, GOLD | 60-80% [6] | >94% [6] | High enrichment [6] | Medium to Fast | Excellent physical plausibility, proven reliability [9] [6] |

| Generative Diffusion Models | SurfDock, DiffBindFR | 70-92% [6] | 40-64% [6] | Variable | Fast (after training) | Superior pose accuracy, efficient sampling [6] |

| Regression-Based Models | KarmaDock, GAABind | 30-60% [6] | 20-50% [6] | Limited | Very Fast | Rapid prediction, but often produces invalid geometries [6] |

| Hybrid Methods | Interformer | 70-85% [6] | 80-90% [6] | Good | Medium | Balanced performance, combines AI scoring with traditional search [6] |

| Template-Based | TEMPL, FRED, HYBRID | Comparable to traditional [8] | High (structure-based) | Good for analogous compounds | Fast when templates available | Excellent for congeneric series, interpretable results [8] [4] |

Performance Across Dataset Types

Recent comprehensive evaluations reveal distinct performance patterns across different benchmarking scenarios:

Known Complexes (Astex Diverse Set): Traditional methods and hybrid approaches show robust performance with high physical validity (>94% for Glide SP), while diffusion models achieve exceptional pose accuracy (>91% for SurfDock) but with reduced physical plausibility (63.5%) [6].

Unseen Complexes (PoseBusters Benchmark): Performance gaps widen, with traditional methods maintaining stability while some AI methods show significant drops in both pose accuracy and physical validity, highlighting generalization challenges [6].

Novel Binding Pockets (DockGen Dataset): All methods show reduced performance, but traditional and hybrid methods demonstrate better adaptation to novel protein environments compared to pure AI approaches [6].

Table 2: Essential resources for molecular docking studies.

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Sources | Key Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Source experimental and predicted protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/, https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [1] [7] |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, PubChem, ChEMBL, DrugBank | Source commercially available and bioactive compounds for virtual screening | https://zinc.docking.org/, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ [1] |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD, DOCK, FRED, HYBRID | Perform docking simulations and virtual screening | Varies: open-source (AutoDock) to commercial (Glide) [1] [4] |

| Structure Preparation Tools | CHARMM-GUI, AutoDock Tools, BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Prepare and optimize protein and ligand structures | https://www.charmm-gui.org/, https://autodocksuite.scripps.edu/ [5] |

| Visualization & Analysis | PyMOL, UCSF Chimera, BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer | Visualize docking results and analyze interactions | https://pymol.org/, https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ [1] [5] |

| Validation Tools | PoseBusters | Check physical plausibility and geometric quality of docking poses | https://github.com/posebusters/posebusters [6] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

AI and Machine Learning Integration

The field of molecular docking is undergoing rapid transformation with the integration of artificial intelligence:

Deep Learning Pose Prediction: Methods like EquiBind, DiffDock, and TankBind use geometric deep learning and diffusion models to achieve superior pose accuracy, though concerns about physical plausibility and data leakage remain [8] [6].

Cofolding Approaches: AlphaFold3 and related methods simultaneously predict protein structure and ligand placement, showing promise particularly when experimental structures are unavailable [8] [9].

AI-Enhanced Scoring Functions: Machine learning models are being developed to improve binding affinity predictions by learning complex patterns from large structural datasets, addressing limitations of traditional scoring functions [3] [6].

Large-Scale Virtual Screening

Ultra-large virtual screening campaigns involving billions of compounds have become feasible with current computing resources [2]. Best practices for such campaigns include:

- Pre-screening Filters: Use rapid similarity searching and property-based filters to reduce library size before docking

- Staged Docking Protocols: Implement multi-tiered approaches with increasing precision at each stage

- Control Calculations: Include known actives and decoys to validate screening performance for each target

- Cluster Computing: Leverage distributed computing resources for processing massive compound libraries

Challenges and Limitations

Despite significant advances, important challenges persist:

- Generalization Gap: AI methods often struggle with novel protein targets or binding pockets not well-represented in training data [6]

- Interaction Recovery: Many ML docking methods prioritize low RMSD but fail to recapitulate key molecular interactions critical for biological activity [9]

- Receptor Flexibility: Accurate modeling of full receptor flexibility remains computationally challenging, though molecular dynamics simulations can provide post-docking refinement [3]

- Solvation Effects: Explicit treatment of water molecules and solvation energies in binding remains difficult in standard docking protocols

- Accuracy vs. Speed Trade-offs: Balancing computational efficiency with prediction accuracy continues to drive method development

The continued integration of physical principles with data-driven approaches, improved handling of flexibility, and enhanced generalization capabilities represent the most promising directions for advancing molecular docking methodologies in computer-aided drug design.

Non-covalent interactions are fundamental forces governing molecular recognition in biological systems, forming the physical basis for protein-ligand interactions in structure-based drug design [10]. These weak, reversible forces—hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects—collectively determine binding specificity and affinity between pharmaceutical compounds and their protein targets [10]. Unlike covalent bonds, non-covalent interactions range from 1-5 kcal/mol in strength but produce highly stable and specific associations through cumulative effects at binding interfaces [10]. Understanding these interactions is crucial for predicting ligand binding poses and accelerating rational drug discovery through molecular docking approaches [10] [11].

The binding process is governed by the thermodynamic principle of Gibbs free energy (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS), where favorable binding requires a negative ΔG value achieved through complementary balancing of enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) contributions [10]. Molecular docking algorithms leverage this principle to predict how small molecule ligands interact with protein targets by simulating the complex formation through computational methods [10] [11]. This document provides a comprehensive overview of these key non-covalent interactions, their quantitative characteristics, and experimental protocols for their investigation in the context of molecular docking research.

Theoretical Foundations of Non-Covalent Interactions

Hydrogen Bonds

Hydrogen bonds are polar electrostatic interactions represented as D—H···A, where D is an electron donor atom, H is a hydrogen atom attached to the donor, and A is an electron acceptor atom [10]. The donor atom must be electronegative (typically oxygen or nitrogen in biological systems), while the acceptor possesses lone electron pairs [10]. With a strength of approximately 5 kcal/mol—significantly weaker than covalent bonds (~110 kcal/mol for O-H)—hydrogen bonds play crucial roles in biomolecular recognition and stability [10]. In aqueous environments, the extensive hydrogen bonding network with solvent molecules creates a dynamic equilibrium where bonds constantly break and reform, significantly influencing the enthalpy and entropy of protein-ligand complex formation [10].

Ionic Interactions

Ionic interactions (also called salt bridges or electrostatic interactions) occur between permanently charged groups or strongly polarized atoms, creating attractive forces between oppositely charged ionic pairs [10]. These highly specific electrostatic interactions are strongly influenced by the solvent environment, particularly in aqueous solutions where ions become surrounded by hydration shells of water molecules, modulating their interaction strength [10]. The dielectric constant of the medium significantly affects the strength of ionic interactions, making them particularly important in partially shielded protein binding pockets where the local dielectric constant may be lower than in bulk solvent [10].

Van der Waals Interactions

Van der Waals interactions arise from transient fluctuations in electron distribution around atoms and molecules, creating temporary dipoles that induce complementary dipoles in neighboring molecules [10]. These nonspecific interactions are relatively weak (~1 kcal/mol) but become biologically significant when numerous atoms at optimal separation distances (typically 3-4 Ã…) contribute collectively to molecular recognition [10]. Recent research has revealed that van der Waals interactions in multilayer structures exhibit many-body characteristics that cannot be adequately described by simple pairwise addition, highlighting their quantum mechanical complexity [12]. Atomic force microscopy studies demonstrate that these interactions are significantly influenced by the broader molecular context, including underlying substrates in supported molecular systems [12].

Hydrophobic Interactions

Hydrophobic interactions describe the tendency of nonpolar molecules and surfaces to associate in aqueous environments, primarily driven by entropy changes in the surrounding water molecules rather than direct attractive forces between the nonpolar entities [10]. When nonpolar groups aggregate, they release structured water molecules from hydration shells into bulk solvent, increasing system entropy and providing a favorable thermodynamic driving force (ΔG < 0) despite minimal enthalpy changes [10]. According to scaled-particle theory, the molecular mechanisms of hydrophobic effects are multifaceted and depend on solute size, with different thermodynamic principles governing small versus large hydrophobic surfaces [10] [13].

Quantitative Comparison of Non-Covalent Interactions

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Non-Covalent Interactions in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Interaction Type | Strength (kcal/mol) | Distance Dependence | Directionality | Key Role in Binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | ~5 [10] | ~1/r³ [10] | High (linear D-H···A preferred) | Specificity and orientation |

| Ionic Interactions | 3-8 (context dependent) [10] | ~1/r² (in vacuum) [10] | Moderate (charge-centered) | Binding affinity, especially in buried pockets |

| Van der Waals | ~1 [10] | ~1/rⶠ[10] | None (nonspecific) | Shape complementarity, close contact |

| Hydrophobic | ~0.1-1 per Ų [10] [13] | Entropy-driven | None | Driving force for association |

Table 2: Experimental and Computational Techniques for Studying Non-Covalent Interactions

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Key Measured Parameters | Applicable Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | ~1-3 Ã… [10] | Atomic positions, distances, angles | All types, especially hydrogen bonds |

| Cryo-EM | ~3-5 Ã… [10] | Molecular shapes, interfaces | Hydrophobic, van der Waals |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Atomic [10] | Dynamics, distances, chemical shifts | All in solution state |

| Atomic Force Microscopy | Sub-nanometer [12] | Adhesion forces, interaction energy | Van der Waals, hydrophobic |

| Molecular Dynamics | Atomic | Energy components, stability, kinetics | All, with computational models |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry | N/A | ΔH, ΔS, Ka, stoichiometry | Overall binding thermodynamics |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Assessment of Non-Covalent Interactions via Molecular Docking

Purpose: To predict and characterize non-covalent interactions between a protein target and small molecule ligands using molecular docking approaches [10] [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein Structure: experimentally determined (PDB format) or computationally predicted structure [10] [14]

- Ligand Structures: 2D or 3D chemical structures in SDF, MOL2, or similar formats [15]

- Docking Software: AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD, or deep learning-based tools (DiffDock, SurfDock) [6]

- Computational Resources: Workstation with multi-core CPU, GPU acceleration recommended for deep learning methods [11]

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure from Protein Data Bank or predictive models (AlphaFold2, ESMFold) [10] [14]

- Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, except crucial structural waters [15]

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states at physiological pH [15]

- Identify binding site residues based on experimental data or binding site prediction tools (LABind, DeepSite) [14]

Ligand Preparation:

Docking Execution:

- Define search space using grid boxes centered on binding site (typically 30×30×30 ų) [15]

- For blind docking, encompass entire protein surface or predicted binding regions [11] [14]

- Set docking parameters (exhaustiveness, number of poses) based on method requirements [6]

- Execute docking runs and generate multiple pose predictions (typically 10-20 per ligand) [15]

Interaction Analysis:

- Visualize top-ranked poses in molecular visualization software [15]

- Identify specific non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, ionic pairs, hydrophobic contacts) [10] [13]

- Measure interaction distances and geometries against optimal values [10]

- Calculate binding free energy estimates using scoring functions [6]

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If poses lack chemical realism, apply post-docking minimization or use physics-based refinement [6]

- For poor pose prediction accuracy, consider flexible residue docking or ensemble docking approaches [11]

- If binding affinity correlations are weak, use consensus scoring or machine-learning scoring functions [6]

Protocol 2: Binding Free Energy Calculation Using MM/GBSA

Purpose: To estimate protein-ligand binding free energies by molecular mechanics approaches with generalized Born and surface area solvation [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- Molecular Dynamics Software: GROMACS, AMBER, or similar packages [15] [16]

- Force Fields: CHARMM, AMBER, or OPLS parameters for proteins and ligands [16]

- Trajectory Analysis Tools: In-built packages or custom scripts for energy decomposition [15]

Procedure:

- System Setup:

Equilibration:

Production MD:

MM/GBSA Calculation:

Notes: The MM/GBSA method provides more reliable binding affinity estimates than docking scoring functions but requires significantly more computational resources [15]. Entropy calculations remain challenging and may be omitted for high-throughput applications [15].

Protocol 3: Experimental Validation of Non-Covalent Interactions

Purpose: To experimentally characterize non-covalent interactions in protein-ligand complexes using biophysical and structural biology techniques.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified Protein: ≥95% purity, correctly folded, in appropriate buffer [10]

- Ligand Compounds: High-purity (>95%) compounds dissolved in DMSO or buffer [15]

- Crystallization Reagents: Commercially available screening kits [10]

- Biophysical Instruments: X-ray diffractometer, isothermal titration calorimeter, surface plasmon resonance biosensor [10]

Procedure:

- X-ray Crystallography:

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC):

- Degas protein and ligand solutions to eliminate air bubbles [10]

- Load protein solution into sample cell and ligand solution into syringe [10]

- Program automated injections with adequate spacing between injections [10]

- Measure heat changes upon each injection and fit data to binding model [10]

- Extract ΔH, ΔS, Ka, and stoichiometry (n) parameters [10]

Atomic Force Microscopy (for surface interactions):

Data Interpretation: Crystallography provides atomic-level interaction details, ITC delivers complete thermodynamic profiles, and AFM measures single-molecule interaction forces under various conditions [10] [12].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for comprehensive characterization of non-covalent interactions in protein-ligand complexes, integrating computational and experimental approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Non-Covalent Interaction Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Protein-ligand docking with scoring function [15] [6] | Initial pose prediction, virtual screening |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | MD simulation with free energy calculations [16] | Binding stability, conformational sampling |

| LABind | Binding Site Prediction | Graph transformer for ligand-aware site prediction [14] | Binding residue identification |

| PoseBusters | Validation Toolkit | Checks physical/chemical plausibility of poses [6] | Pose quality assessment |

| DiffDock | Deep Learning Docking | Diffusion model for blind docking [11] [6] | Pose prediction without predefined site |

| PDBBind Database | Structural Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding data [10] [11] | Method training and benchmarking |

| CHARMM Force Field | Molecular Mechanics | Potential functions for energy calculations [16] | MD simulations, energy minimization |

| ITC Instrument | Experimental Setup | Measures binding thermodynamics directly [10] | ΔH, ΔS, and Ka determination |

| Cytosaminomycin D | Cytosaminomycin D, MF:C23H36N4O8, MW:496.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Asparenomycin A | Asparenomycin A, MF:C14H16N2O6S, MW:340.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Non-covalent interactions represent the fundamental language of molecular recognition in biological systems, with hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects collectively dictating the specificity and affinity of protein-ligand binding [10]. Molecular docking methodologies continue to evolve, with traditional physics-based approaches now complemented by deep learning methods that show promising results in pose prediction, though challenges remain in ensuring physical plausibility and generalization to novel targets [11] [6]. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation through structural biology and biophysical techniques provides the most robust approach for characterizing these complex interactions [10] [15] [12]. As molecular docking continues to advance, particularly with incorporation of protein flexibility and many-body physical effects, researchers are better equipped to leverage understanding of non-covalent interactions for accelerated drug discovery and biological mechanism elucidation [11] [12].

The thermodynamics of protein-ligand interactions form the fundamental basis for understanding molecular recognition in biological systems and rational drug design. The binding affinity between a protein and ligand is quantitatively expressed by the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG), which relates to the binding constant through the equation ΔG = -RTlnKeq [10]. This free energy change comprises two competing components: the enthalpy change (ΔH), representing the heat released or absorbed during binding primarily through formation and breaking of chemical bonds, and the entropy change (ΔS), representing the change in system disorder, multiplied by temperature (TΔS) [10].

A phenomenon frequently observed in protein-ligand interactions is enthalpy-entropy compensation (EEC), where a more favorable (negative) enthalpy change is counterbalanced by a less favorable (negative) entropy change, or vice versa, resulting in minimal net change in the overall binding free energy [17]. This compensation effect presents significant challenges in drug discovery, where structural modifications designed to improve binding affinity often yield disappointing results due to this thermodynamic balancing act.

The Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation Phenomenon

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Analysis

Enthalpy-entropy compensation is a well-documented phenomenon in protein-ligand interactions. Statistical analysis of 3025 protein-ligand affinities from the Protein Data Bank reveals that ΔG values for protein-ligand interactions follow a Gaussian distribution centered around -36.5 kJ/mol, with approximately 70% of cases falling between -46 and -26 kJ/mol [17]. This narrow range of ΔG values occurs despite enormously varied enthalpy and entropy values spanning ranges of -232 kJ/mol to 59.2 kJ/mol for ΔH and -190 kJ/mol to 64 kJ/mol for TΔS [17].

The linear relationship between ΔH and TΔS leads to an approximately constant value of ΔG around -30 to -35 kJ/mol across diverse protein-ligand systems [17]. This compensation behavior has been observed consistently for over fifty years in thermodynamic studies of protein-ligand interactions in aqueous solution and is particularly problematic in drug discovery campaigns where medicinal chemists seek to optimize lead compounds through structural modifications.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameter Ranges in Protein-Ligand Interactions

| Parameter | Typical Range | Average Value | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG | -46 to -26 kJ/mol | -36.5 kJ/mol | Gaussian distribution, narrow range |

| ΔH | -232 to 59.2 kJ/mol | Variable | Large variability between systems |

| TΔS | -190 to 64 kJ/mol | Variable | Large variability between systems |

| Compensation Slope | ~1 | — | Linear ΔH vs TΔS relationship |

Molecular Origins and Implications

The molecular origin of enthalpy-entropy compensation remains controversial and has been attributed to various factors. From an evolutionary perspective, the narrow range of ΔG values may reflect adaptive optimization of proteins to achieve maximum regulatory capacity through conformational versatility and exchange of minute energy quanta with the environment [17]. At the molecular level, binding involves complex rearrangements of water molecules, protein conformational changes, and formation of non-covalent interactions, all of which contribute to both enthalpy and entropy changes.

The functional implication of this compensation is profound for drug discovery. When structural modifications to a lead compound produce a more favorable enthalpy change through improved interactions with the target protein, this gain is frequently offset by entropy losses due to reduced flexibility or increased solvent ordering [17]. Consequently, substantial efforts in optimizing ligand-receptor interactions often yield disappointingly small improvements in binding affinity.

Non-Covalent Interactions in Molecular Recognition

Fundamental Interaction Types

Protein-ligand recognition is mediated through several types of non-covalent interactions, each with characteristic energy contributions and structural properties:

- Hydrogen bonds: Polar electrostatic interactions between hydrogen bond donors (D-H) and acceptors (A) with typical strengths of approximately 5 kcal/mol (~21 kJ/mol). These interactions are highly directional and strongly influenced by the solvent environment [10].

- Van der Waals interactions: Non-specific attractions between transient dipoles in electron clouds with strengths of approximately 1 kcal/mol (~4 kJ/mol). These interactions, while weak individually, contribute significantly to binding through cumulative effects [10].

- Ionic interactions: Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged groups, highly specific but influenced by solvent screening and solvation shells [10].

- Hydrophobic interactions: Associations of non-polar groups in aqueous solution, primarily driven by entropy gain from water molecule reorganization [10].

Table 2: Non-Covalent Interactions in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Interaction Type | Strength (kJ/mol) | Characteristics | Role in Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | ~21 | Directional, solvent-sensitive | Specificity, enthalpy contribution |

| Van der Waals | ~4 | Non-specific, distance-dependent | Packing, shape complementarity |

| Ionic Interactions | Variable | Distance and dielectric-dependent | Strong electrostatic contributions |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Variable | Entropy-driven, area-dependent | Major entropy contribution |

Molecular Recognition Models

Three conceptual models describe the mechanism of molecular recognition in protein-ligand binding:

Lock-and-Key Model: Theorizes pre-complementary binding interfaces between rigid proteins and ligands, representing an entropy-dominated binding process with minimal conformational changes [10].

Induced-Fit Model: Proposes conformational changes in the protein during binding to optimally accommodate the ligand, adding flexibility to the lock-and-key concept [10].

Conformational Selection Model: Suggests ligands bind selectively to the most suitable conformational state from an ensemble of pre-existing protein conformations [10].

Experimental Protocols for Thermodynamic Characterization

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Protocol

Purpose: Direct measurement of binding thermodynamics including ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, and binding stoichiometry.

Materials:

- Isothermal titration calorimeter (e.g., MicroCal VP-ITC)

- Purified protein solution (>95% purity)

- Ligand solution in matching buffer

- Dialysis buffer for exact solvent matching

- Degassing apparatus

Procedure:

- Precisely match the buffer composition between protein and ligand solutions through dialysis or careful preparation.

- Degas all solutions to prevent bubble formation during measurements.

- Load the protein solution into the sample cell (typically 1.4 mL volume) and ligand solution into the injection syringe.

- Program the titration method: typically 25-30 injections of 2-10 μL each with 120-180 second intervals between injections.

- Perform the experiment at constant temperature (typically 25°C or 37°C).

- Include a control experiment of ligand injections into buffer alone for heat of dilution correction.

- Analyze data using nonlinear least-squares fitting to obtain ΔH, Ka (association constant), and stoichiometry (n).

- Calculate ΔG from ΔG = -RTlnKa and ΔS from ΔS = (ΔH - ΔG)/T.

Data Interpretation:

- Exothermic reactions (negative ΔH) typically indicate favorable hydrogen bonding or van der Waals interactions.

- Entropy-driven binding (positive TΔS) often suggests hydrophobic effects or release of bound water molecules.

- Enthalpy-entropy compensation manifests when improvements in ΔH are offset by decreases in TΔS.

Computational Docking and Free Energy Calculations

Purpose: Prediction of binding modes and affinities through computational approaches.

Materials:

- High-performance computing resources

- Protein structure (experimental or predicted)

- Ligand structure database

- Docking software (e.g., Glide, AutoDock, GOLD)

- Molecular dynamics simulation packages

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or generate with AlphaFold2 [18]

- Remove crystallographic water molecules except those mediating key interactions

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states at physiological pH

- Energy minimization to relieve steric clashes

Binding Site Identification:

- Define binding pocket from known complexes or predicted active sites

- Generate grid maps encompassing the binding region

Molecular Docking:

- Perform flexible ligand docking with multiple conformational searches

- Score poses using empirical, force-field, or knowledge-based scoring functions

- Cluster results and select representative binding modes

Molecular Dynamics Refinement (Optional):

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in explicit water molecules

- Apply physiological ionic concentration

- Equilibrate system with positional restraints followed by free dynamics

- Run production simulation (typically 50-500 ns) [18]

- Analyze trajectories for stability and interaction persistence

Free Energy Calculations:

- Employ methods like MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA, or free energy perturbation

- Decompose energy contributions per residue or interaction type

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Thermodynamic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| ITC Instrumentation | MicroCal VP-ITC or equivalent | Direct measurement of binding thermodynamics |

| Protein Purification System | FPLC with affinity columns | Production of pure, functional protein |

| Buffer Components | High-purity salts, buffers | Maintain physiological conditions |

| AlphaFold2 | Computational structure prediction | Generate protein models when experimental structures unavailable [18] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Refine structures and simulate dynamics [18] |

| Docking Software | Glide, AutoDock Vina, TankBind | Predict binding modes and affinities [18] |

Visualization of Thermodynamic Relationships and Methodologies

Thermodynamic Relationships in Protein-Ligand Binding

ITC Experimental Workflow

Implications for Drug Discovery and Molecular Docking

The phenomenon of enthalpy-entropy compensation has profound implications for structure-based drug design. While molecular docking approaches have advanced significantly, challenges remain in accurately predicting binding affinities, particularly for protein-protein interactions [18]. Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that AlphaFold2-generated structures perform comparably to experimental structures in docking protocols, expanding the structural database available for drug discovery [18].

Local docking strategies generally outperform blind docking approaches, with TankBind_local and Glide providing particularly robust results across diverse protein structures [18]. Integration of molecular dynamics simulations and ensemble-based approaches can improve docking outcomes in selected cases, though performance improvements vary significantly across different conformations [18].

The limited range of ΔG values observed across diverse protein-ligand systems (-46 to -26 kJ/mol) suggests evolutionary optimization of protein flexibility and interaction energies to achieve optimal regulatory function [17]. This fundamental constraint underscores the importance of considering thermodynamic profiles in lead optimization, moving beyond simple affinity measurements to understand the enthalpic and entropic drivers of molecular recognition.

{#introduction} Molecular recognition, the process by which biological molecules interact specifically with each other and with small ligands, forms the cornerstone of all biological processes and structure-based drug design. The conceptual models describing these interactions have evolved significantly from Emil Fischer's initial "lock-and-key" analogy proposed in 1894 to more sophisticated frameworks that account for protein dynamics and flexibility [19] [20]. This evolution reflects our growing understanding of the intricate dance between proteins and ligands, which is crucial for advancing molecular docking methodologies and improving the accuracy of ligand pose prediction [19] [10]. As the central thesis of this article, we posit that the progression from static to dynamic recognition models has been, and continues to be, the primary driver of innovation in computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to tackle increasingly complex challenges in predicting protein-ligand complex structures.

{##conceptual-evolution}

Conceptual Evolution of Molecular Recognition Models

{###lock-and-key}

The Lock-and-Key Model

Introduced by Emil Fischer in 1894, the lock-and-key model conceptualizes molecular recognition through a simple analogy: the enzyme (lock) and the substrate (key) possess complementary, pre-formed geometric shapes that fit perfectly together [19] [21]. This model posits that both interacting partners are essentially rigid, and their conformations remain unchanged during the binding event [10]. While this model successfully explained early observations of enzyme specificity, its major limitation was the failure to account for the inherent flexibility of proteins and the conformational changes that often accompany ligand binding [19]. Despite its simplicity, the lock-and-key paradigm profoundly influenced the philosophical underpinnings of early molecular docking approaches, which treated both the protein receptor and the ligand as static entities [19].

{###induced-fit}

The Induced-Fit Model

In 1958, Daniel Koshland proposed the induced-fit model as a necessary modification to address the shortcomings of the lock-and-key analogy [19] [20]. This model suggests that the active site of an enzyme is not a static cavity; rather, it is reshaped during interactions with the substrate [19]. The ligand induces conformational changes in the protein, leading to an optimal binding arrangement that would not occur with a rigid protein structure [10] [20]. This concept is more akin to a "pin tumbler lock," where the key (ligand) allows internal components (protein residues) to move into the correct alignment [19]. The induced-fit model accounts for why certain ligands that appear sterically compatible may not bind, as they fail to induce the necessary conformational adjustments. It also explains phenomena like allosteric and non-competitive inhibition [20]. From a computational perspective, incorporating induced-fit effects remains a significant challenge due to the vast conformational space that must be sampled [19].

{###conformational-selection}

The Conformational Selection Model

The conformational selection model, sometimes referred to as selected-fit, represents a further refinement of our understanding [21]. In this model, the protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium between multiple conformational states even in the absence of ligand [10] [21]. The ligand does not "induce" a new conformation but rather selectively binds to the pre-existing conformational state for which it has the highest affinity, thereby stabilizing that state and shifting the equilibrium population [10] [21]. In an extended recognition mechanism, ligands may first bind to a favorable initial protein conformation, which is then followed by additional conformational adjustments [10]. This model aligns with the modern understanding of proteins as dynamic ensembles and provides a more robust thermodynamic explanation for many allosteric effects.

{###keyhole-lock-key}

The Keyhole-Lock-Key Model

For enzymes with deeply buried active sites, a more specialized model has been proposed: the keyhole-lock-key model [21]. This model incorporates the critical role of access tunnels (keyholes) that connect the active site (lock) to the bulk solvent [21]. These tunnels are not merely passive conduits; their anatomy, physico-chemical properties, and dynamics can discriminate between substrates, control the entry of co-substrates, and prevent cellular damage by sequestering reactive intermediates [21]. The catalytic cycle, therefore, involves the passage of the ligand through the tunnel, reorganization of water molecules, binding to catalytic residues, chemical transformation, and finally, product exit [21]. This model is particularly relevant for engineering enzyme activity, specificity, and stability by modifying these access pathways rather than the active site itself [21].

{##comparison}

Comparative Analysis of Recognition Models

{###table-comparison} Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Recognition Models

| Model | Proposed Year | Core Principle | View of Protein Structure | Thermodynamic Driver | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lock-and-Key [19] [10] | 1894 | Steric and geometric complementarity | Rigid and static | Entropy-dominated (ΔS) [10] | Oversimplified; ignores flexibility |

| Induced-Fit [19] [20] | 1958 | Ligand binding induces conformational change | Flexible and adaptable | Enthalpy-driven (ΔH) | Can be computationally prohibitive to model |

| Conformational Selection [10] [21] | ~2000s | Ligand binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing conformation | Dynamic ensemble of states | Combination of ΔH and ΔS | Requires knowledge of multiple states |

| Keyhole-Lock-Key [21] | ~2000s | Access tunnels (keyholes) are critical for catalysis | Dynamic, with gated access | Kinetically controlled by tunnels | Most applicable to enzymes with buried active sites |

The following diagram illustrates the logical and temporal relationships between the different molecular recognition models, showing how each new theory built upon and refined its predecessors.

{caption="Figure 1: Evolution of molecular recognition models over time"}

{##applications-docking}

Applications in Molecular Docking and Ligand Pose Prediction

The evolution of molecular recognition theories has directly informed the development and application of computational docking methodologies. Modern docking approaches strive to incorporate the dynamic principles of induced-fit and conformational selection to improve predictive accuracy.

{###table-computational-tools} Table 2: Computational Tools Implementing Dynamic Recognition Principles

| Computational Tool | Underlying Recognition Model | Key Methodology | Application in Pose Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| ColdstartCPI [22] | Induced-Fit | Uses Transformers to learn flexible, context-dependent features for compounds and proteins. | Treats proteins and compounds as flexible entities during inference, improving predictions for unseen compounds and proteins. |

| DynamicBind [23] | Conformational Selection & Dynamics | Deep equivariant generative model that constructs a smooth energy landscape. | Efficiently samples large protein conformational changes to recover ligand-specific holo-structures from apo-like inputs. |

| Traditional Rigid Docking [19] | Lock-and-Key | Treats protein as rigid and samples only ligand flexibility. | Fast but often fails when significant protein side-chain or backbone movement is required for binding. |

{###protocol}

Protocol: Implementing a Dynamic Docking Workflow with DynamicBind

Purpose: To predict the binding pose of a ligand to a protein target, accounting for substantial protein conformational changes, using the DynamicBind model [23].

{####materials}

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for DynamicBind Docking Protocol

| Item Name | Function/Description | Specification/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein Sequence | The primary amino acid sequence of the protein target. | FASTA format string. |

| AlphaFold-Predicted Structure | Provides the initial apo-like protein conformation for docking. | PDB file format. |

| Ligand Structure | The small molecule to be docked. | SMILES string or SDF file. |

| DynamicBind Software | The deep learning model for dynamic docking. | Publicly available code (e.g., from GitHub repository). |

| RDKit Library | Open-source cheminformatics library. | Used for generating initial ligand conformations [23]. |

{####procedure}

Procedure

Input Preparation:

- Protein Structure: Obtain the 3D structure of your target protein. If an experimental holo-structure is unavailable, use an AlphaFold-predicted conformation as the input PDB file [23].

- Ligand Structure: Provide the ligand structure in a SMILES string or SDF format. RDKit will be used internally to generate an initial 3D conformation [23].

Ligand Placement:

- Run DynamicBind, which will begin by randomly placing the ligand around the putative binding site of the input protein structure [23].

Iterative Pose Optimization:

- The model will run for a default of 20 iterations. The process involves two phases [23]:

- Steps 1-5: The model optimizes the ligand's pose by translating, rotating, and adjusting its internal torsional angles. The protein remains fixed during this initial phase.

- Steps 6-20: The model simultaneously optimizes both the ligand and the protein. It adjusts the protein's conformation by translating/rotating residues and modifying side-chain chi angles to accommodate the ligand [23].

- The model will run for a default of 20 iterations. The process involves two phases [23]:

Pose Selection and Validation:

- DynamicBind generates multiple output complex structures. Use the built-in contact-LDDT (cLDDT) scoring module to rank the predictions. A higher cLDDT score correlates with a lower ligand RMSD, indicating a more reliable pose [23].

- Select the top-ranked pose for downstream analysis. The final output is a PDB file of the protein-ligand complex, often with a protein conformation closer to the true holo-state than the initial AlphaFold input [23].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

{caption="Figure 2: DynamicBind dynamic docking workflow"}

{##discussion}

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The progression from the rigid lock-and-key model to dynamic and ensemble-based views has fundamentally transformed the field of structure-based drug design. Modern deep learning approaches, such as ColdstartCPI and DynamicBind, are now explicitly embedding the principles of induced-fit and conformational selection into their architectures, leading to significant improvements in handling cold-start scenarios and predicting large-scale protein conformational changes [22] [23]. However, formidable challenges remain. Accurately modeling the role of water molecules in mediating binding interactions and achieving a comprehensive representation of full protein flexibility continue to be active areas of research [19]. The future of molecular docking and ligand pose prediction lies in the development of even more sophisticated models that can seamlessly integrate multiple recognition mechanisms, fully account for solvent dynamics, and efficiently explore the vast energy landscape of protein-ligand complexes. This will be crucial for unlocking new therapeutic targets and accelerating the drug discovery process.

Docking Methodologies in Practice: Algorithms, Software, and Workflow Strategies

Molecular docking is a fundamental computational technique in structural biology and drug discovery that predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor) [24]. The core challenge docking aims to solve is identifying the ligand's binding mode and affinity, which requires efficiently searching the vast conformational and positional space available to the ligand [25]. Systematic search algorithms represent a class of docking methods characterized by their deterministic exploration of this space, in contrast to stochastic methods which rely on random sampling [24] [25]. These algorithms are crucial for reproducing experimental binding modes and have become integral to structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to understand molecular interactions at an atomic level and accelerate the identification of potential therapeutic compounds [26] [27].

The development of systematic approaches is rooted in the evolution of binding theory. The earliest "lock-and-key" theory, proposed by Fischer, treated both ligand and receptor as rigid bodies [24]. This conceptual foundation led to the first docking methods which employed rigid-body treatment. Koshland's "induced-fit" theory advanced this understanding by recognizing that the active site of a protein is often reshaped by interactions with ligands, highlighting the need for algorithms that could account for molecular flexibility [24]. Systematic search algorithms emerged as a solution to this challenge, providing methodologies to comprehensively explore conformational space while maintaining computational feasibility. Their development has been instrumental in transitioning docking from a conceptual model to a practical tool that can accurately predict binding geometries, with modern algorithms capable of reproducing experimentally observed binding modes with root-mean-square deviations (RMSD) of 0.5 to 1.2 Ã… [26].

Classification and Theoretical Framework of Systematic Search Methods

Systematic search algorithms in molecular docking can be broadly categorized into three main approaches: exhaustive methods, incremental construction, and database searches. Each employs distinct strategies to manage the computational complexity of exploring the ligand's conformational and positional degrees of freedom [24] [25].

Exhaustive or Direct Methods involve the systematic enumeration of a ligand's degrees of freedom through gradual changes to its translational, rotational, and torsional parameters [25]. This approach aims to comprehensively explore the conformational space but often requires strategies to prune the search tree and avoid combinatorial explosion. The method guarantees that all possible configurations within defined constraints are evaluated, making it particularly valuable when a complete mapping of the energy landscape is required [25].

Incremental Construction (IC) methods, also known as fragmentation approaches, decompose the ligand into multiple fragments by breaking rotatable bonds [24] [28]. The largest fragment or the one with significant functional interactions is typically selected as the "base" or "anchor" and docked first into the active site [24] [28]. Subsequent fragments are then added incrementally, with different orientations generated to fit the active site, thereby reconstructing the complete ligand while accounting for its flexibility [26] [24]. This method significantly reduces the search space compared to exhaustive approaches and has been implemented in successful docking programs like FlexX, DOCK 4.0, and SLIDE [24]. Research has demonstrated that with multiple automated base selection, the quality of docking predictions is nearly as good as with manually preselected base fragments, making the approach practical for large-scale virtual screening [28].

Database Search methods leverage pre-existing structural information to enhance docking efficiency [24] [25]. These approaches generate multiple reasonable conformations for small molecules already cataloged in structural databases and dock them as rigid bodies [25]. The method capitalizes on the known structural diversity of chemical compounds to limit the conformational search space, offering significant computational advantages for screening large compound libraries [24]. Tools utilizing this approach include FLOG, which applies matching algorithms based on molecular shape to map ligands into active sites according to shape features and chemical information [24].

Table 1: Classification of Systematic Search Algorithms in Molecular Docking

| Algorithm Type | Key Principle | Representative Software | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exhaustive/Direct Methods | Systematic enumeration of torsional, translational, and rotational degrees of freedom | DOCK (early versions) | Comprehensive exploration of conformational space; deterministic results |

| Incremental Construction | Fragment-based ligand reconstruction in binding site | FlexX, DOCK 4.0, Hammerhead, SLIDE, eHiTS | Efficient handling of ligand flexibility; fast execution suitable for virtual screening |

| Database Search | Rigid docking of pre-generated conformations from structural databases | FLOG, LibDock, SANDOCK | High speed; excellent for database enrichment and screening large compound libraries |

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Systematic Search Algorithms

Evaluating the performance of systematic search algorithms requires multiple metrics that reflect their computational efficiency, sampling accuracy, and practical utility in drug discovery applications. The performance characteristics vary significantly across different algorithm types, with inherent trade-offs between sampling comprehensiveness and computational demand [24].

The computational speed of these algorithms spans several orders of magnitude, with database search methods typically achieving the highest throughput due to their reliance on pre-computed conformations [24]. Incremental construction approaches offer a balanced compromise, with methods like FlexX capable of docking ligands in seconds to minutes depending on complexity [26] [24]. Exhaustive methods generally demand the greatest computational resources but provide the most complete exploration of the conformational landscape [25]. The accuracy of pose prediction is commonly measured by RMSD between predicted and experimentally determined crystal structures, with values below 2.0 Ã… generally considered successful reproduction of the binding mode [29]. Incremental construction algorithms have demonstrated particular effectiveness, achieving RMSD deviations of 0.5 to 1.2 Ã… across diverse test cases [26].

Sampling effectiveness varies according to each algorithm's approach to managing flexibility. Incremental construction efficiently handles ligand flexibility by focusing on fragment assembly rather than whole-molecule conformational sampling [24] [28]. This approach has proven highly effective, with studies showing that incremental construction can correctly identify experimental binding modes among the highest-ranking conformations in most test cases [26]. The method's performance can be further enhanced through multiple automatic base selection, which generates more diverse solutions and identifies alternative binding modes with low scores [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Systematic Search Algorithms

| Performance Metric | Exhaustive Methods | Incremental Construction | Database Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed | Slowest (hours to days per ligand) | Fast (seconds to minutes per ligand) | Fastest (multiple ligands per second) |

| Accuracy (RMSD) | Variable (dependent on sampling granularity) | High (0.5-1.2 Ã… reported) [26] | Moderate to High (dependent on database coverage) |

| Ligand Flexibility Handling | Comprehensive but computationally expensive | Efficient through fragmentation | Limited to pre-computed conformations |

| Virtual Screening Applicability | Low due to speed constraints | High (balanced speed and accuracy) | Excellent for primary screening |

| Pose Prediction Success Rate | High with sufficient sampling | High (71-85% for optimized algorithms) [26] | Moderate to High |

Experimental Protocols for Systematic Search Algorithms

Protocol for Incremental Construction with FlexX

The FlexX docking software implements the incremental construction algorithm and has been widely validated for molecular docking applications. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for pose prediction using this method [24]:

Step 1: System Preparation

- Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling. Prepare the structure by removing heteroatoms except essential cofactors, adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning partial charges using appropriate force fields [27] [29].

- Prepare the ligand structure by energy minimization using molecular mechanics force fields. Assign Gasteiger-Huckel charges to structure atoms and perform molecular dynamics (e.g., Simulated Annealing) to obtain conformations with minimum global energy [29].

Step 2: Base Fragment Selection

- FlexX automatically fragments the ligand at rotatable bonds, identifying multiple base fragments according to predefined rules and algorithms [28]. The base is typically the largest rigid fragment or the fragment with the most potential interaction points.

- Alternatively, manual selection of a specific base fragment can be performed if prior knowledge suggests its importance in binding [28].

Step 3: Placement of Base Fragment

- The base fragment is positioned in the active site using a pattern-matching algorithm based on chemical feature complementarity [24]. Triangle matching is used to place the base fragment by matching hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, and interaction centers between the protein and ligand [29].

- Multiple placements are generated to ensure adequate sampling of possible orientations.

Step 4: Incremental Reconstruction

- The remaining fragments are added incrementally to the base fragment in a tree-growing process. At each step, conformational space is sampled by rotating around rotatable bonds [24].

- The maximum number of solutions per iteration is typically set to 1000, with the maximum number of solutions per fragmentation set to 200 to balance comprehensiveness and computational efficiency [29].

Step 5: Scoring and Ranking

- Generated poses are evaluated using an empirical scoring function that accounts for hydrophobic contact surfaces, hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and aromatic stacking [24] [29].

- The top poses (typically 10-30) are retained for further analysis, with the highest-ranking conformation representing the predicted binding mode [29].

Validation: The docking protocol should be validated by redocking a known co-crystallized ligand and calculating the RMSD between the docked and native conformation. An RMSD value ≤ 2.0 Å indicates a validated protocol [29].

Protocol for Database Search with FLOG

FLOG (Flexible Ligands Oriented on Grid) utilizes a database search approach to molecular docking, offering high-throughput screening capabilities [24]:

Step 1: Database Preparation

- Compile a database of diverse, drug-like compounds in a standardized format (e.g., SMILES, SDF). Filter compounds according to Lipinski's Rule of Five to enhance drug-likelihood [30].

- Generate multiple conformers for each compound using rule-based or knowledge-based methods. Energy minimization should be performed for each conformer to ensure structural stability.

Step 2: Receptor Setup

- Prepare the protein structure by defining the active site through reference to known binding ligands or active site prediction algorithms (e.g., GRID, PASS) [24].

- Generate molecular interaction fields representing shape and chemical complementarity using programs like DOCK.

Step 3: Shape-Based Matching

- Each conformer from the database is systematically fitted into the active site based on steric and chemical complementarity [24] [25].

- The matching algorithm aligns ligand atoms with complementary interaction sites in the protein binding pocket.

Step 4: Scoring and Prioritization

- Poses are evaluated using force field-based or empirical scoring functions [25].

- High-ranking compounds are selected for further experimental validation or more detailed computational analysis.

Workflow Visualization of Systematic Search Algorithms

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and logical relationships between different systematic search algorithms in molecular docking:

Systematic Search Algorithms Workflow in Molecular Docking

The incremental construction algorithm specifically follows a detailed workflow for flexible ligand docking, as illustrated below:

Incremental Construction Algorithm Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Docking

Successful implementation of systematic search algorithms requires a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources. The table below details essential research reagents and their functions in molecular docking workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Docking Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Docking Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | FlexX | Implements incremental construction algorithm for flexible ligand docking | Fragment-based docking; fast execution; integration with BioSolveIT suite [24] [29] |

| DOCK | Versatile docking package employing multiple algorithms including database search | Geometry-based approach; suitable for virtual screening and database enrichment [24] [2] | |

| FLOG | Database search docking using pre-computed conformations | High-speed screening; shape-based matching [24] | |

| Structure Preparation | AutoDock Tools (MGL Tools) | Prepares receptor and ligand files in PDBQT format | Adds Gasteiger charges; defines rotatable bonds; grid parameter generation [27] [31] |

| Protein Preparation Wizard | Processes protein structures for docking | Adds hydrogens; assigns partial charges; optimizes hydrogen bonding [32] | |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined protein structures | Source of receptor structures and co-crystallized ligands for validation [30] |

| ChEMBL Database | Curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Source of compound libraries for virtual screening [30] | |

| Visualization & Analysis | PyMOL | Molecular visualization and manipulation | Structure analysis; image generation; cavity detection [31] |

| Discovery Studio Visualizer | Comprehensive suite for structural analysis | Interaction analysis; binding pose assessment; visualization of docking results [27] |

Molecular docking is a pivotal technique in computer-aided drug design (CADD) that predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor) [33] [10]. The core challenge lies in efficiently searching the vast conformational and orientational space of the ligand to identify the binding pose that minimizes the free energy of the system. This search space is exceptionally complex and high-dimensional, making exhaustive systematic searches computationally intractable for all but the simplest systems [25] [34].

Stochastic search algorithms provide a powerful solution to this challenge by incorporating an element of randomness, allowing them to navigate complex energy landscapes effectively without being trapped in local minima [25] [35]. Unlike systematic methods that explore every possible conformation, stochastic methods sample the search space intelligently, making them particularly suitable for docking simulations where computational efficiency is crucial [25]. These algorithms have become fundamental components of many widely used docking programs, enabling researchers to perform virtual screening, lead optimization, and mechanistic studies in structural biology [33] [10].

The three predominant stochastic approaches in molecular docking are Monte Carlo methods, Genetic Algorithms, and Tabu Search. Each employs distinct strategies for managing the trade-off between exploration (searching new regions of the conformational space) and exploitation (refining promising solutions) [25] [35]. Their performance is critical for predicting accurate binding modes, which directly impacts the success of structure-based drug design campaigns [34].

Table 1: Core Stochastic Search Algorithms in Molecular Docking

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Common Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo | Random sampling with probabilistic acceptance criteria | Simple implementation, avoids local minima | AutoDock Vina, MCDock, ICM |

| Genetic Algorithms | Population-based evolution through selection, crossover, mutation | Effective for complex spaces, parallelizable | AutoDock, GOLD, rDock |

| Tabu Search | Memory-based guidance to avoid revisiting solutions | Prevents cycling, efficient for rugged landscapes | PRO_LEADS, Molegro Virtual Docker |

Algorithm Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Monte Carlo Methods

Monte Carlo (MC) methods in molecular docking rely on random sampling of the ligand's conformational and orientational degrees of freedom [25]. The fundamental principle involves generating random changes to the ligand's position, orientation, and torsion angles, then evaluating the resulting binding energy using a scoring function [25]. A key feature of MC algorithms is the Metropolis criterion, which determines whether to accept or reject new configurations based on the change in energy (ΔE) [25].

The Metropolis criterion accepts energetically favorable moves (ΔE < 0) outright, while permitting unfavorable moves (ΔE > 0) with a probability proportional to e^(-ΔE/kT), where k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature parameter [25]. This controlled acceptance of worse solutions allows the algorithm to escape local energy minima and explore a broader region of the conformational space [25]. Modern docking programs often enhance basic MC with iterative search strategies; for instance, AutoDock Vina 1.2.0 combines Monte Carlo with the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) method for local refinement of ligand conformations [31].

Monte Carlo approaches are particularly valuable in specialized docking scenarios. Recent advancements have integrated MC with other techniques, such as Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC), to simulate the insertion and deletion of fragments in binding sites, overcoming sampling limitations in molecular dynamics-based simulations [36]. Furthermore, combined DFT, Monte Carlo, and molecular docking studies demonstrate the utility of MC in probing adsorption processes and corrosion inhibition properties, highlighting its versatility beyond traditional drug-target applications [37].

Genetic Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are population-based optimization techniques inspired by biological evolution [25] [35]. In molecular docking, GAs operate on a population of candidate ligand poses, each represented as a "chromosome" encoding translational, rotational, and torsional degrees of freedom [25] [34]. The algorithm iteratively improves this population through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, with the "fitness" of each pose typically being the predicted binding affinity [25].

The Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA), implemented in AutoDock 4.2, represents a significant advancement by incorporating local search to refine individual poses within the evolutionary framework [34]. This hybrid approach accelerates convergence by allowing individuals to adapt within their lifetime (Lamarckian evolution) rather than relying solely on genetic operations [34]. Parameter tuning is crucial for GA performance; a study on algorithm selection for protein-ligand docking examined 28 distinct LGA variants, highlighting how parameters like population size, mutation rates, and crossover operations significantly impact docking accuracy and efficiency [34].

GAs have proven particularly effective for de novo drug design. AutoGrow4, an open-source toolkit for semi-automated computer-aided drug discovery, exploits a genetic algorithm combined with molecular docking to generate novel ligands for a given target [38]. This approach efficiently explores chemical space through an evolutionary process that builds new molecules from fragment libraries, though it may exhibit bias toward high molecular weight compounds [38].

Tabu Search

Tabu Search (TS) employs adaptive memory structures to guide the search process, explicitly preventing revisiting recently explored solutions [25] [35]. The core mechanism maintains a "tabu list" of forbidden moves or solutions, effectively prohibiting the algorithm from cycling back to previously visited regions of the conformational space [25]. This memory-based approach allows TS to navigate rugged energy landscapes more efficiently than memoryless algorithms [25].

At each iteration, Tabu Search generates candidate moves from the current solution and selects the best move that is not in the tabu list [25]. This strategy encourages exploration of new territories in the search space, making it particularly effective for problems with numerous local optima [25]. The tabu list is typically maintained as a FIFO (first-in, first-out) queue, with the size of the list carefully balanced to prevent cycling without overly restricting promising directions [25].

Tabu Search has been implemented in docking software such as PRO_LEADS and Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) [25]. Its ability to strategically avoid previously sampled conformations makes it valuable for thorough pose prediction, especially when dealing with flexible ligands that have many rotatable bonds [25] [35].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Stochastic Search Algorithms

| Parameter | Monte Carlo | Genetic Algorithms | Tabu Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Space Coverage | Broad but can miss optima | Excellent due to population | Targeted with memory guidance |

| Convergence Speed | Variable, depends on cooling schedule | Moderate to slow | Fast for local regions |

| Memory Usage | Low | High (maintains population) | Moderate (maintains tabu list) |

| Handling of Local Minima | Good (via probability) | Very good (via diversity) | Excellent (via tabu list) |

| Parallelization Potential | Moderate | High | Low to moderate |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Monte Carlo Docking with AutoDock Vina

Purpose: To predict the binding pose and affinity of a small molecule ligand within a protein active site using Monte Carlo search.

Materials:

- Receptor Preparation: 3D protein structure from PDB, prepared by removing water molecules, adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning partial charges using MGLTools [31].

- Ligand Preparation: 3D ligand structure in PDBQT format, with optimized geometry and correct torsion trees defined [33] [31].

- Software: AutoDock Vina 1.2.0 or newer [31].

- Computing Resources: Multi-core CPU workstation or computing cluster.

Procedure:

- Define Search Space:

- Identify binding site coordinates based on known catalytic residues or co-crystallized ligands.

- Create a grid box centered on the binding site with dimensions sufficient to accommodate the ligand (typically 20×20×20 Å) [31].

- Set the exhaustiveness parameter (default 8) to control search intensity [31].

Parameter Configuration:

- Configure the

search_alg_PSOparameter to 0 to ensure use of the standard MC/BFGS algorithm [31]. - For flexible side chains, define flexible residues in the receptor configuration file.

- Configure the

Execute Docking:

- Run Vina with the prepared receptor, ligand, and configuration file.

- Perform multiple runs (recommended: 10-30 repetitions) to assess consistency [31].

Pose Analysis:

- Extract top-ranked poses based on binding affinity (kcal/mol).

- Calculate Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) relative to crystallographic reference if available.

- Cluster similar conformations to identify predominant binding modes.

Troubleshooting:

- Poor convergence may require increasing exhaustiveness parameter or expanding search space dimensions.

- Physically implausible poses may indicate issues with ligand torsion tree definition or insufficient sampling.

Protocol 2: Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm with AutoDock