Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Hyperuricemia Patients with Diabetes: Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate crosstalk between lipid metabolism and hyperuricemia in diabetic patients.

Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Hyperuricemia Patients with Diabetes: Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate crosstalk between lipid metabolism and hyperuricemia in diabetic patients. It explores foundational discoveries of specific dysregulated lipid species and pathways, such as glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism, identified via advanced lipidomics. The content delves into methodological approaches for analyzing these disruptions, examines the associated challenges in patient management and drug development, and evaluates emerging therapeutic strategies, including GLP-1 receptor agonists and novel small molecule inhibitors. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms and identifies promising targets for future biomarker discovery and precision medicine interventions in this complex comorbidity.

Unraveling the Core Lipid Pathways: Molecular Connections Between Hyperuricemia and Diabetic Dysregulation

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represents a complex metabolic disorder characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion. Beyond its direct glycemic effects, T2DM frequently presents with a cluster of metabolic comorbidities, notably dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia, which independently and synergistically contribute to increased cardiovascular disease (CKD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and microvascular complications [1] [2]. The co-occurrence of these conditions signifies a more advanced stage of metabolic dysregulation, warranting earlier and more aggressive intervention strategies [1].

The pathophysiological interplay between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in T2DM involves overlapping mechanisms including insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction [1] [3]. In uncontrolled T2DM—typically defined by persistently elevated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) above target thresholds—these mechanisms are amplified, leading to accelerated vascular damage and a higher incidence of adverse renal and cardiovascular outcomes [1]. Understanding the epidemiological landscape and underlying biological pathways connecting these conditions is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic approaches for high-risk T2DM populations.

Epidemiological Landscape: Quantifying the Co-Occurrence

Prevalence Estimates and Population Risk

Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate a strong association between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in T2DM populations, with significant variations across geographic regions and patient subgroups.

Table 1: Epidemiological Studies on Dyslipidemia and Hyperuricemia Co-Occurrence

| Study Population | Sample Size | Prevalence/Association | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled T2DM (Romania) | 304 patients | 81.6% co-occurrence prevalence | RMRS significantly higher in co-occurrence group (median 16.9 vs. 10.0; p<0.001) | [1] [2] |

| General Population (Wuhu, China) | 298,891 participants | OR: 1.878 (95% CI: 1.835-1.922) | Dyslipidemia associated with 1.9x higher odds of hyperuricemia in multivariate analysis | [4] [5] |

| Hypertensive Chinese Population | 274 patients | Significant indirect effect via triglycerides | Hyperuricemia linked to T2DM through triglyceride mediation (coefficient=0.87, P=0.04) | [6] |

| Japanese vs. American Populations | 90,047 Japanese; 14,734 Americans | BMI cut-off for hyperuricemia: 23 kg/m² (Japan) vs. 27 kg/m² (U.S.) | Higher BMI associated with hyperuricemia risk in both populations, but at lower BMI thresholds in Japan | [7] |

The relationship between specific dyslipidemia subtypes and hyperuricemia reveals important patterns. In the large Wuhu population study, individuals with hypertriglyceridemia had 1.753 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.706-1.802), while those with mixed hyperlipidemia had 1.925 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.870-1.982) of hyperuricemia compared to those without dyslipidemia [4] [5]. This suggests that combined lipid abnormalities confer the greatest risk for elevated uric acid levels.

When examining lipid components, triglycerides demonstrate the strongest association with hyperuricemia. Individuals in the highest triglyceride quartile had 3.744 times higher odds of hyperuricemia (95% CI: 3.636-3.918) compared to those in the lowest quartile [4] [5]. Other significant lipid parameters included total cholesterol (OR: 1.518) and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (OR: 1.775) in fully adjusted models.

Demographic and Clinical Risk Modifiers

The relationship between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in T2DM is further modulated by demographic and clinical factors:

Body Mass Index (BMI): A comparative study of Japanese and American populations revealed that while higher BMI was an independent risk factor for hyperuricemia in both populations, the BMI cut-off point above which hyperuricemia prevalence significantly increased was substantially lower in Japan (23 kg/m²) compared to the U.S. (27 kg/m²) [7]. This suggests ethnic variations in susceptibility to metabolic complications of obesity.

Hypertension: In hypertensive populations, the triad of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperuricemia creates a particularly high-risk metabolic profile. Research indicates that hypertensive individuals with hyperuricemia demonstrate significantly higher triglyceride levels, which mediate diabetes risk in this population [6].

Diabetic Control Status: The Romanian study focusing specifically on uncontrolled T2DM (HbA1c ≥7%) found an exceptionally high co-occurrence rate of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia (81.6%), suggesting that poor glycemic control exacerbates the clustering of these metabolic abnormalities [1] [2].

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The strong epidemiological association between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in T2DM is underpinned by several interconnected biological pathways.

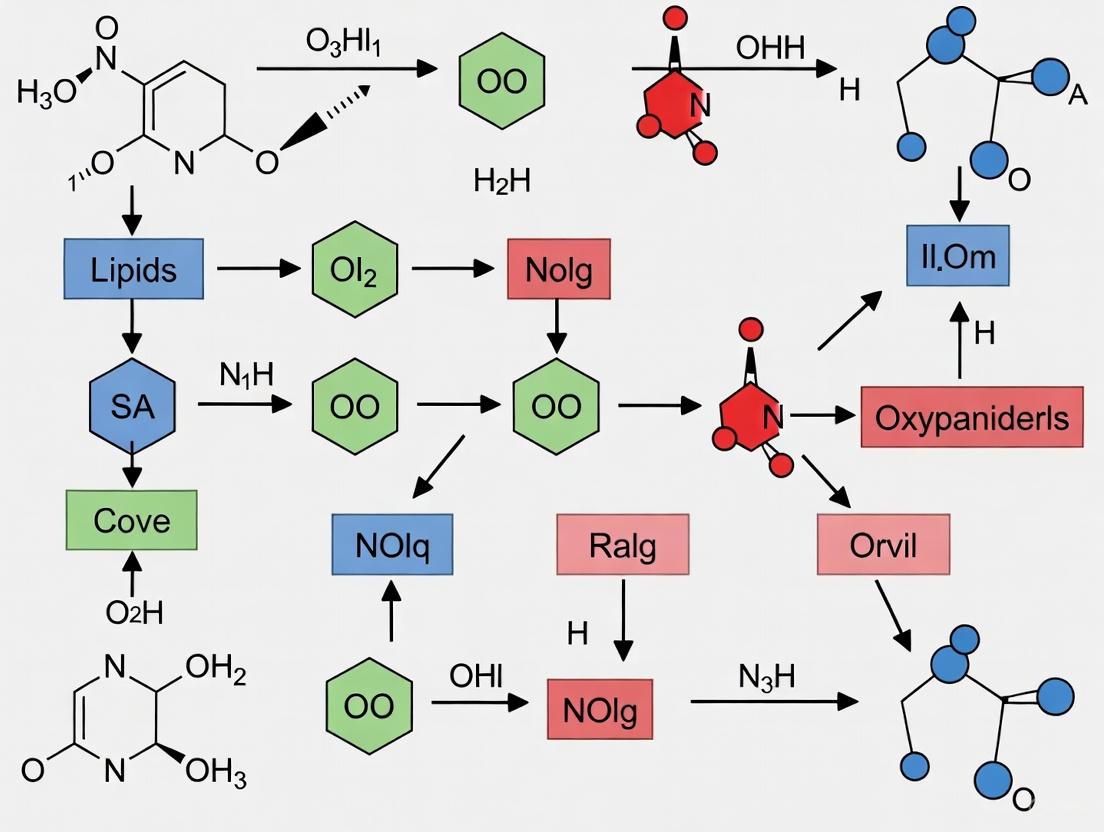

Integrated Metabolic Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key pathophysiological mechanisms connecting dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in T2DM:

Key Mechanistic Insights

Lipid Metabolism Disorders in Hyperuricemia

Advanced lipidomics approaches have revealed specific alterations in lipid metabolism associated with hyperuricemia. A multiomics study analyzing serum from 60 healthy individuals and 60 hyperuricemia patients identified 33 significantly upregulated lipid metabolites in hyperuricemia patients [8]. These metabolites were primarily involved in:

- Arachidonic acid metabolism

- Glycerophospholipid metabolism

- Linoleic acid metabolism

- GPI-anchor biosynthesis

- Alpha-linolenic acid metabolism

The study further established connections between specific immune factors and glycerophospholipid metabolism, including IL-10, CPT1, IL-6, SEP1, TGF-β1, Glu, TNF-α, and LD [8]. This suggests that hyperuricemia promotes a pro-inflammatory state that disrupts normal lipid metabolic pathways.

Triglyceride-Mediated Pathway to Diabetes

In hypertensive populations, triglycerides play a crucial mediating role between hyperuricemia and T2DM. Generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) analysis revealed that while the direct effect of hyperuricemia on diabetes was not statistically significant (coefficient = -0.61, P=0.10), the indirect effect mediated by triglycerides was substantial (coefficient = 0.87, P=0.04) [6]. The path analysis demonstrated:

- Hyperuricemia → Elevated triglycerides (coefficient = 0.67, P=0.01)

- Elevated triglycerides → Increased diabetes risk (coefficient = 1.29, P<0.001)

This pathway underscores the importance of triglyceride metabolism as a mechanistic bridge between uric acid elevation and diabetes development in high-risk populations.

Uric Acid's Dual Role in Oxidative Stress

Uric acid exhibits a double-edged sword role in physiological and pathological contexts [3]. At normal levels, uric acid functions as a powerful antioxidant, effectively neutralizing singlet oxygen molecules, oxygen radicals, and peroxynitrite molecules due to its ability to provide electrons and act as a reducing agent [3]. However, when uric acid levels become elevated, it transforms into a pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory molecule that exacerbates oxidative stress [3]. This paradoxical behavior contributes to the complex relationship between uric acid levels and metabolic dysfunction.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Core Laboratory Techniques

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Method/Reagent | Application | Technical Specifics | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/HPLC Lipidomics | Identification of differential lipid metabolites | UPLC system; Q-Exactive Plus MS; C18 column; positive/negative ion modes | Quantified 33 dysregulated lipids in hyperuricemia; identified 5 affected metabolic pathways [8] |

| ELISA Kits | Measurement of inflammatory cytokines & metabolic markers | Commercial kits for TNF-α, IL-6, CPT1, TGF-β1, etc.; microplate reader detection | Confirmed dysregulation of immune factors linked to glycerophospholipid metabolism [8] |

| Automatic Biochemical Analyzer | Standard lipid & uric acid profiling | Enzymatic colorimetric methods for TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, SUA | Enabled large-scale epidemiological studies (n=298,891) with standardized measurements [4] [5] |

| Generalized Structural Equation Modeling (GSEM) | Mediation analysis of metabolic pathways | Bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs (5,000 resamples); adjustment for age, sex, BMI, medications | Quantified triglyceride mediation between HUA and T2DM (indirect effect: 0.87, P=0.04) [6] |

Analytical Workflows

The following diagram illustrates a standardized experimental workflow for investigating the dyslipidemia-hyperuricemia relationship in metabolic disease research:

Advanced Statistical Approaches

Contemporary research employs sophisticated statistical models to unravel the complex relationships between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia:

Multivariable Logistic Regression: The large-scale Chinese study (n=298,891) employed binary logistic regression with sequential adjustment models (Model 1: unadjusted; Model 2: age and sex-adjusted; Model 3: fully adjusted for age, sex, smoking, drinking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and renal function parameters) to isolate the independent association between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia [4] [5].

Risk Score Development: The Renal-Metabolic Risk Score (RMRS) was developed using standardized values of urea, TG/HDL ratio, and eGFR, with variable weights derived from logistic regression coefficients. The score was normalized to a 0-100 scale and demonstrated good discriminative performance (AUC: 0.78) for identifying T2DM patients with combined hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia [1] [2].

Mediation Analysis: The triglyceride mediation effect was tested using generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) containing three paths: (i) hyperuricemia → triglycerides, (ii) triglycerides → T2DM, and (iii) hyperuricemia → T2DM, with adjustment for clinical covariates including renal function and medication use [6].

The robust epidemiological association between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia in T2DM populations is supported by large-scale clinical evidence across diverse ethnic groups. The co-occurrence of these conditions, particularly in uncontrolled diabetes, identifies a high-risk subgroup requiring aggressive therapeutic management. The pathophysiological interplay involves complex mechanisms including shared metabolic pathways, inflammatory activation, and oxidative stress, with emerging evidence highlighting triglycerides as a key mediator in the hyperuricemia-diabetes relationship.

From a drug development perspective, these insights suggest that therapeutic strategies targeting both lipid metabolism and uric acid pathways may provide synergistic benefits for high-risk T2DM patients. Future research should focus on validating the RMRS in diverse populations, exploring the therapeutic potential of combined lipid- and urate-lowering approaches, and investigating specific molecular targets within the identified lipid metabolic pathways that link these two common metabolic disorders.

In the intricate landscape of metabolic disorders, the comorbidity of hyperuricemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents a significant clinical challenge, with dysregulated lipid metabolism serving as a crucial pathological link. Hyperuricemia, characterized by elevated serum uric acid levels, and T2DM, defined by impaired glucose regulation, frequently coexist, with epidemiological studies reporting a hyperuricemia prevalence of 21-32% among T2DM patients [9]. The interplay between these conditions is mediated substantially through perturbations in specific lipid classes, primarily triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and phosphatidylcholines (PCs). These lipids are not merely biomarkers but active participants in the pathophysiological processes, influencing insulin resistance, inflammatory responses, and metabolic homeostasis [10] [8] [11]. This review synthesizes current evidence on the roles of these three key lipid classes within the context of hyperuricemia and diabetes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical resource encompassing quantitative findings, methodological protocols, and visualized pathways.

Quantitative Profiling of Dysregulated Lipids

Advanced lipidomic technologies have revealed distinct alterations in triglyceride, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylcholine profiles in patients with coexisting hyperuricemia and diabetes. These quantitative changes provide critical insights into the metabolic disturbances characterizing this comorbidity.

Table 1: Summary of Key Lipid Alterations in Hyperuricemia with Diabetes

| Lipid Class | Specific Lipid Species | Change Direction | Statistical Significance | Study Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG (16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significant upregulation | P < 0.001, FDR < 0.05 | DH vs. NGT (n=17/group) | [10] |

| Triglycerides | Overall TG levels | Significant elevation | P = 0.005 | Hypertensive diabetic patients (n=274) | [12] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE (18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significant upregulation | P < 0.001, FDR < 0.05 | DH vs. NGT (n=17/group) | [10] |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC (36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significant upregulation | P < 0.001, FDR < 0.05 | DH vs. NGT (n=17/group) | [10] |

| Diacylglycerols (DAGs) | DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5), DAG (18:1/22:6) | Significant upregulation | P < 0.05 | Middle-aged/elderly Chinese (n=2247) | [11] |

Table 2: Mediation and Pathway Analysis of Dysregulated Lipids

| Analytical Approach | Key Finding | Effect Size/Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Structural Equation Modeling (GSEM) | Triglycerides mediate hyperuricemia-diabetes association | Indirect effect: coefficient = 0.87, P = 0.04 | [12] |

| Pathway Enrichment Analysis | Glycerophospholipid metabolism disturbance | Impact value = 0.199 | [10] |

| Pathway Enrichment Analysis | Glycerolipid metabolism disturbance | Impact value = 0.014 | [10] |

| Network Analysis | TAGs/PCs/DAGs module association with HUA risk | Positive association, P < 0.01 | [11] |

The magnitude of triglyceride dysregulation is particularly striking, with one study reporting that occasional smoking increased diabetes risk (OR=3.92, 95% CI: 1.00-15.35), while hyperuricemia was positively associated with elevated triglyceride levels (coefficient = 0.67, P=0.01), which subsequently increased DM risk (coefficient = 1.29, P < 0.001) [12]. The mediating role of triglycerides between hyperuricemia and diabetes underscores their central position in the metabolic cascade, explaining why although the direct effect of hyperuricemia on DM was not statistically significant (coefficient = -0.61, P=0.10), the indirect effect mediated by triglycerides was substantial (coefficient = 0.87, P=0.04) [12].

Methodological Framework for Lipid Analysis

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

The accuracy of lipidomic profiling hinges on standardized sample preparation protocols. In studies of hyperuricemia and diabetes, the following methodology has been employed:

Sample Collection: Fasting venous blood samples (5 mL) are collected in EDTA-containing tubes or serum separation tubes [10] [8]. For plasma preparation, whole blood is immediately inverted for homogenization and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C [8]. The resulting plasma or serum is aliquoted and stored at -80°C until analysis.

Lipid Extraction: A modified methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) protocol is widely implemented [10] [11]. Briefly, 100 μL of plasma is mixed with 200 μL of 4°C water and 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol. After vortexing, 800 μL of MTBE is added, followed by sonication in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes and incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes [10]. The mixture is centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C, and the upper organic phase is collected and dried under nitrogen gas [8]. The dried lipids are reconstituted in 200 μL of 90% isopropanol/acetonitrile for mass spectrometric analysis.

Lipid Quantification Using UHPLC-MS/MS

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) represents the gold standard for comprehensive lipid profiling:

Chromatographic Conditions: Separation is typically performed using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) maintained at 45°C [10] [8]. The mobile phase consists of:

- Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile:water (6:4 v/v)

- Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile:isopropanol (2:9 v/v) The gradient elution program runs from 30% mobile phase B (0-2 min) to 100% B (2-25 min), followed by re-equilibration [8].

Mass Spectrometry Parameters: Analysis is conducted using a SCIEX 5500 QTRAP or similar mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization [11]. Positive ion mode settings typically include: heater temperature 300°C, sheath gas flow rate 45 arb, spray voltage 3.0 kV, and capillary temperature 350°C. Negative ion mode uses a spray voltage of 2.5 kV [8]. Data acquisition employs both full scans (MS1, range 200-1800 m/z) and fragment scans (MS2) for structural identification.

Quality Control and Data Processing

Robust quality control measures are essential for reliable lipidomic data:

- Quality Control Samples: Pooled samples from all participants are prepared and analyzed every 10-15 experimental samples to monitor instrument stability [10] [11].

- Data Processing: Lipid identification and quantification are performed using specialized software (e.g., Analyst 1.6.3, MarkerView) [11]. Lipids with >20% missing data or coefficient of variation >30% in quality controls are typically excluded from further analysis [11].

- Statistical Analysis: Multivariate statistical approaches including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) are employed to identify differentially abundant lipids [10]. Significant lipid species are determined using a combination of p-value (<0.05) and false discovery rate (FDR) correction (<0.05) to account for multiple testing [10].

Pathophysiological Pathways and Mechanisms

The dysregulated lipid classes participate in interconnected metabolic pathways that bridge hyperuricemia and diabetes pathophysiology. The following diagram illustrates key mechanistic relationships:

The mechanistic relationships illustrate how triglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylcholines occupy central positions in the pathological network connecting hyperuricemia to diabetes. Hyperuricemia directly promotes elevations in all three lipid classes, with triglycerides demonstrating particularly strong association (coefficient = 0.67, P=0.01) [12]. These lipids subsequently contribute to diabetes development through multiple pathways: triglycerides directly increase diabetes risk (coefficient = 1.29, P<0.001) [12], while phosphatidylethanolamines and phosphatidylcholines primarily drive pro-inflammatory responses that exacerbate insulin resistance [8].

Notably, de novo lipogenesis—particularly involving 16:1n-7 fatty acids—strongly correlates with triglyceride and phosphatidylcholine elevations (Spearman correlation coefficients = 0.32-0.41, p<0.001) [11]. The adipokine retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) mediates approximately 5-14% of the lipid-hyperuricemia association, providing a molecular link between dyslipidemia and insulin resistance [11]. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where insulin resistance impairs renal uric acid excretion, further elevating serum uric acid levels and perpetuating the metabolic disturbances [9].

Experimental Workflow for Lipidomic Analysis

The technical workflow for comprehensive lipid profiling in hyperuricemia-diabetes research involves multiple standardized steps from sample collection to data interpretation, as visualized below:

This standardized workflow ensures reproducible lipidomic profiling across studies. The MTBE-based extraction efficiently recovers a broad lipid spectrum, while the UHPLC-MS/MS platform provides the sensitivity and resolution needed to distinguish structurally similar lipid species [10] [11]. Critical quality control measures, including randomized sample analysis and regular quality control injections, minimize technical variability and enhance data reliability [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipidomic Studies

| Category | Specific Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column (2.1×100mm, 1.7μm) | Lipid separation | Maintain at 45°C for optimal resolution [10] [8] |

| Mobile Phases | Ammonium formate in ACN/Hâ‚‚O (10mM) | Mobile phase A | Improves ionization efficiency [8] |

| Ammonium formate in ACN/IPA (10mM) | Mobile phase B | Facilitates elution of nonpolar lipids [8] | |

| Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction | Less toxic alternative to chloroform [10] [11] |

| HPLC-grade methanol | Protein precipitation | Pre-cooled to 4°C [8] | |

| Mass Spectrometry | SCIEX 5500 QTRAP Mass Spectrometer | Lipid detection & quantification | ESI source, positive/negative mode switching [11] |

| Internal Standards | Deuterated lipid standards | Quantification normalization | Species-specific for each lipid class [11] |

| Sample Preparation | Low-protein binding tubes | Sample storage | Prevents lipid adsorption [10] |

| Data Analysis | Analyst 1.6.3 Software | Data acquisition | Enables MS1 and MS2 data collection [11] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and equipment is critical for successful lipidomic profiling. The MTBE extraction method offers advantages over traditional chloroform-based methods, including higher recovery of polar lipids and formation of a upper organic phase that simplifies collection [10] [11]. The use of ammonium formate in mobile phases enhances ionization efficiency in mass spectrometry, improving detection sensitivity [8]. Deuterated internal standards are essential for accurate quantification, correcting for matrix effects and extraction efficiency variations [11].

The comprehensive profiling of triglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylcholines in the context of hyperuricemia and diabetes has revealed their crucial roles as mediators, biomarkers, and potential therapeutic targets. The consistent upregulation of these lipid classes across multiple studies, their participation in key metabolic pathways, and their demonstrated mediation effects underscore the interconnected nature of purine, glucose, and lipid metabolism.

Future research directions should focus on several key areas: First, the development of targeted therapeutic approaches that simultaneously address hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, potentially through agents that modulate glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism [9]. Second, the exploration of specific lipid species as precision medicine biomarkers for identifying high-risk individuals and monitoring intervention efficacy. Third, deeper investigation into the molecular mechanisms through which specific PE and PC species initiate and propagate inflammatory signaling in the context of hyperuricemia [8]. Finally, research into dietary and pharmacological interventions that specifically target the de novo lipogenesis pathway to reduce the production of atherogenic lipid species [11].

The integration of advanced lipidomics with other omics technologies and the application of causal inference methods like Mendelian randomization will further elucidate the complex relationships between these lipid classes and metabolic diseases, ultimately accelerating the development of effective interventions for patients with coexisting hyperuricemia and diabetes.

The coexistence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) represents a complex pathological condition characterized by concurrent disturbances in glucose and urate metabolism. The underlying pathophysiology is multifactorial, involving insulin resistance, oxidative stress, lipid metabolic dysfunction, and impaired renal urate excretion [9]. Epidemiological studies across diverse populations have consistently demonstrated a substantial prevalence of hyperuricemia among individuals with T2DM, ranging from 21% to 32% [9]. This comorbidity is typically associated with worsened insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and pronounced visceral obesity [9]. The bidirectional pathophysiological relationship between T2DM and HUA contributes to an increased risk of multisystem complications, with lipid metabolism disruptions serving as a central connecting pathway [13] [8] [9].

Recent advances in lipidomic technologies have enabled researchers to characterize specific alterations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism that occur in patients with concurrent diabetes and hyperuricemia [10]. These disruptions are not merely secondary phenomena but actively contribute to disease progression through multiple mechanisms, including inflammatory activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular signaling interference [8] [10]. Understanding these metabolic perturbations at a molecular level provides crucial insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at interrupting this detrimental cycle.

Quantitative Lipidomic Profiling in Diabetic Hyperuricemia

Comprehensive lipidomic analyses reveal significant alterations in plasma lipid profiles among patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH) compared to those with diabetes alone (DM) and healthy controls (NGT). Using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS), researchers have identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses in patient plasma samples, demonstrating the extensive scope of metabolic disruption in this comorbidity [10].

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Metabolites in DH Patients vs. Controls

| Lipid Class | Representative Molecules | Regulation Trend | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) | Significantly upregulated | Energy storage, lipid droplet formation |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) | Significantly upregulated | Membrane structure, cellular signaling |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) | Significantly upregulated | Membrane fluidity, lipid transport |

| Phosphatidylinositols (PIs) | Not specified | Downregulated | Cell signaling, membrane trafficking |

Multivariate statistical analyses including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) have confirmed distinct separation trends among DH, DM, and NGT groups, validating the unique lipidomic signature of the comorbid condition [10]. A total of 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites were pinpointed in the DH group compared to NGT controls, with 13 triglycerides, 10 phosphatidylethanolamines, and 7 phosphatidylcholines showing significant upregulation, while one phosphatidylinositol was downregulated [10].

The collective analysis of these metabolite groups revealed their enrichment in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [10]. Furthermore, comparison of DH versus DM groups identified 12 differential lipids that were also predominantly enriched in these same core pathways, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [10].

Table 2: Pathway Analysis of Lipid Metabolic Disruption in Diabetic Hyperuricemia

| Metabolic Pathway | Impact Value | Key Lipid Classes Involved | Biological Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid Metabolism | 0.199 | PCs, PEs, PIs | Membrane integrity, inflammatory signaling |

| Glycerolipid Metabolism | 0.014 | TGs, DAGs | Energy homeostasis, lipid storage |

| Linoleic Acid Metabolism | Not specified | Fatty acid derivatives | Inflammatory mediator production |

| Arachidonic Acid Metabolism | Not specified | Eicosanoids | Pro-inflammatory signaling |

| Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor Biosynthesis | Not specified | GPI-anchored proteins | Membrane protein anchoring |

Additional studies involving Xinjiang patients with hyperuricemia have identified 33 significantly different lipid metabolites that were markedly upregulated and primarily involved in arachidonic acid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis, and alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism pathways [8]. These lipid metabolites demonstrated significant correlations with immune factors including IL-10, CPT1, IL-6, SEP1, TGF-β1, Glu, TNF-α, and LD, suggesting intricate cross-talk between lipid disruption and inflammatory activation in hyperuricemia [8].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Animal Model Development

To investigate the effects of high uric acid on glucolipid metabolism in diabetes, researchers have developed novel diabetic models of hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia in male Golden Syrian hamsters [13]. The selection of this animal model is strategic, as hamsters better reproduce hyperlipidemia patterns similar to human hepatic lipid metabolism and cholesteryl ester transfer protein activities compared to mice or rats [13].

The experimental design involved forty-two healthy male Golden Syrian hamsters (10 weeks old, 163 ± 7.43 g) obtained from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Company (Beijing, China) [13]. Diabetes was induced in thirty hamsters by intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ) (30 mg/kg) once daily for 3 consecutive days [13]. After ten days, 24 hamsters with fasting blood glucose concentration (>12 mmol/L) were randomly divided into 4 groups (n = 6):

- DC group: standard diet

- DHF group: high-fat/cholesterol diet (HFCD)

- DHU group: PO treatment (intragastric potassium oxonate at 350 mg/kg and adenine at 150 mg/kg with 5% fructose water) with standard diet

- DHFU group: PO treatment with HFCD [13]

An additional twelve healthy hamsters were divided into two groups (n = 6): CHF group (HFCD) and C group (standard diet) as controls [13]. This comprehensive design enabled researchers to examine the individual and synergistic effects of hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, and diabetes.

Analytical Techniques for Lipidomic Profiling

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as the cornerstone technology for comprehensive lipidomic analysis in metabolic disorder research [10]. The detailed methodology encompasses several critical phases:

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction: Plasma samples (100 μL) are mixed with 200 μL of 4°C water, followed by addition of 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol [10]. After mixing, 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) is added, followed by 20 minutes of sonication in a low-temperature water bath and 30 minutes of standing at room temperature [10]. Centrifugation at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C separates the phases, with the upper organic phase collected and dried under nitrogen stream [10].

Chromatographic Separation: Sample separation employs a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm length, 1.7 μm particle size) [10]. The mobile phase consists of:

- Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile solution in water

- Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile isopropanol solution [10]

The analysis uses a 3 μL injection volume, maintains a column temperature of 45°C, and a flow rate of 300 μL per minute [10].

Mass Spectrometric Analysis: Untargeted lipidomic analyses are performed using electrospray ionization mass spectrometers with Q active plus [10]. Positive ion mode source conditions include: heater temperature 300°C, sheath gas flow rate 45 ARB, auxiliary gas flow rate 15 ARB, sweep gas flow rate 1 ARB, spray voltage 3.0 kV, capillary temperature 350°C, and S-lens RF level 50% [10]. Negative ion mode parameters are similar with adjustments to spray voltage (2.5 kV) and S-lens RF level (60%) [10]. Data acquisition covers a scanning range of 200-1800 for MS1, with fragmentation patterns (MS2, HCD) collected to determine mass-to-charge ratios of lipid molecules and fragments [10].

Biochemical and Histopathological Assessments

Complementary to lipidomic profiling, comprehensive biochemical analyses are essential for correlating molecular findings with physiological manifestations. In animal studies, measurements include:

Serum Biochemical Parameters:

- Uric acid, glucose, triglyceride, and total cholesterol levels

- Liver xanthine oxidase activity

- Urea nitrogen and creatinine levels [13]

Molecular Markers:

- Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)

- Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) expressions

- Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [13]

Histopathological Examinations:

- Renal tissue analysis for glomerular mesangial cells and matrix proliferation

- Identification of protein casts and urate deposition

- Assessment of renal structural integrity [13]

Gut Microbiota Analysis:

- Fecal short-chain fatty acids content

- Relative abundance of specific bacterial taxa (e.g., Lieibacterium)

- Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratios [13]

These multidisciplinary approaches enable researchers to establish connections between lipid metabolic disruptions, organ damage, and systemic metabolic consequences in diabetic hyperuricemia.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The disruption of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism in diabetic hyperuricemia activates multiple interconnected pathophysiological mechanisms that accelerate disease progression. Uric acid-induced oxidative stress plays a central role in this process, directly impairing cellular function and promoting inflammatory signaling cascades [13] [9].

Experimental evidence indicates that high uric acid levels are closely associated with decreased antioxidant capacity and increased renal expression of pro-fibrotic factors including plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [13]. These molecular changes manifest structurally as glomerular mesangial cells and matrix proliferation, protein casts, and urate deposition in renal tissues [13]. The synergistic effects of hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia on these parameters highlight the multifaceted nature of organ damage in this comorbidity.

The gut-kidney axis emerges as another significant mechanism in the pathophysiology of diabetic hyperuricemia. Studies demonstrate that high uric acid significantly alters the balance of intestinal flora in diabetic animals, characterized by increased acetic acid content, decreased butyric, propanoic, and isobutyric acid levels, and decreased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratios [13]. These changes in microbial composition and metabolite production further influence host metabolism through effects on epithelial integrity, inflammation, and nutrient absorption [13].

At the cellular level, uric acid has been shown to contribute to diabetes progression by hindering islet beta cell survival rather than directly triggering the disease [14]. This mechanism complements the established understanding of insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, providing a more comprehensive picture of glucose homeostasis disruption in hyperuricemic states. Additionally, research indicates that thioredoxin-interacting protein reduces oxidative stress and counters HUA-induced insulin resistance, suggesting it as a potential therapeutic target [14].

The identification of specific lipid species that are upregulated in diabetic hyperuricemia, including triglycerides with specific fatty acid compositions (e.g., TG(16:0/18:1/18:2)) and phospholipids (e.g., PE(18:0/20:4)), provides molecular targets for understanding how lipid disruptions contribute to metabolic disease progression [10]. These lipids may directly interfere with insulin signaling pathways, promote ceramide accumulation, or serve as precursors for inflammatory mediators that sustain low-grade inflammation characteristic of both diabetes and hyperuricemia.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Lipidomic and Metabolic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specific Application | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Oxonate (PO) | Hyperuricemia induction in animal models | Competitive inhibitor of uricase to increase uric acid concentrations [13] |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | Diabetes induction in animal models | Selective toxicity to pancreatic β-cells to impair insulin production [13] |

| High-Fat/Cholesterol Diet (HFCD) | Metabolic disorder induction | 15% fat, 0.5% cholesterol diet to induce dyslipidemia in animal models [13] |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction from biological samples | Organic solvent for efficient lipid separation from aqueous phases [8] [10] |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive for LC-MS | Enhances ionization efficiency and improves chromatographic separation [10] |

| ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column | Chromatographic separation | 2.1×100mm, 1.7μm particles for high-resolution lipid separation [10] |

| Q-Exactive Plus Mass Spectrometer | Untargeted lipidomic analysis | High-resolution mass detection with electrospray ionization capabilities [8] [10] |

| ELISA Kits for Cytokines | Inflammatory marker quantification | Measures TNF-α, IL-6, TGF-β1, IL-10 levels in patient/animal sera [8] |

| 3'-Hydroxy Simvastatin | 3'-Hydroxy Simvastatin, MF:C25H38O6, MW:434.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,5,6-trihydroxy-3-methoxyxanthone | 1,5,6-trihydroxy-3-methoxyxanthone, CAS:50868-52-5, MF:C14H10O6, MW:274.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comprehensive toolkit enables researchers to model the complex interplay between hyperuricemia, diabetes, and lipid metabolic disruptions, from whole-organism physiology to molecular-level mechanisms. The combination of these reagents and methodologies facilitates the development of translational research approaches that can bridge basic science discoveries with clinical applications.

The selection of appropriate animal models is particularly crucial in this field. While rodent models have traditionally been used, the hamster model offers distinct advantages for hyperlipidemia research due to similarities with human hepatic lipid metabolism and cholesteryl ester transfer protein activities [13]. Additionally, the effects of dietary cholesterol on blood lipid profiles in hamsters more closely mirror human responses compared to other rodent species [13].

Advanced mass spectrometry platforms represent another critical component, with the Q-Exactive Plus instrument providing the sensitivity, resolution, and mass accuracy necessary for comprehensive lipidome characterization [10]. The implementation of both positive and negative ionization modes enables detection of a broad spectrum of lipid classes with diverse chemical properties, from non-polar triglycerides to polar phospholipids [10].

The disruption of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism represents a central pathological mechanism connecting hyperuricemia and diabetes, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle that accelerates metabolic deterioration and promotes end-organ damage. Through advanced lipidomic technologies, researchers have identified specific lipid species and metabolic pathways that are consistently altered in this comorbidity, providing both biomarkers for early detection and targets for therapeutic intervention.

The intricate interplay between uric acid metabolism, lipid homeostasis, and glucose regulation involves multiple organ systems and molecular networks, including inflammatory activation, oxidative stress, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and cellular signaling disruptions. The development of sophisticated animal models that recapitulate the human condition, combined with comprehensive analytical approaches, has enabled significant advances in understanding these complex relationships.

Future research directions should prioritize the development of "dual-action" therapeutic agents capable of simultaneously addressing hyperuricemia and diabetes through targeting of shared metabolic pathways [9]. Additionally, personalized management strategies based on individual metabolic phenotypes hold promise for improving outcomes in this complex patient population. The continued application of lipidomic technologies in longitudinal studies and clinical trials will further elucidate the temporal relationships between lipid disruptions and disease progression, potentially enabling earlier interventions to prevent the devastating consequences of these interconnected metabolic disorders.

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, is revolutionizing our understanding of complex metabolic diseases. In the context of comorbid diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA), advanced lipidomic profiling is moving beyond single-molecule diagnostics to reveal specific lipid species and perturbed pathways that underlie this dangerous synergy. This whitepaper details the identification of definitive lipid biomarkers—including the triglycerides TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and phosphatidylethanolamines PE(18:0/20:4)—and elucidates the glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways as central hubs of the pathological interplay between hyperuricemia and diabetes, offering new avenues for targeted therapeutic strategies.

The coexistence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) represents a significant clinical challenge, driven by intertwined pathophysiological mechanisms including insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and systemic metabolic dysfunction [9]. Epidemiological studies reveal a substantial prevalence of HUA among individuals with T2DM, ranging from 21% to 32%, underscoring a shared metabolic burden that predisposes patients to higher risks of cardiovascular and renal complications [9]. While serum uric acid has traditionally been the focus in HUA management, it fails to capture the full spectrum of metabolic disarray. Lipidomics, a branch of metabolomics, provides a powerful framework to comprehensively characterize lipid metabolites, offering unprecedented insights into the specific molecular changes that occur when diabetes and hyperuricemia converge [10] [15]. This technical guide explores how lipidomic technologies are uncovering novel biomarkers and pathways, moving the field beyond uric acid toward a more integrated and mechanistic understanding of this complex comorbidity.

Key Lipid Biomarkers Identified in Comorbid DM and HUA

Advanced lipidomic profiling using techniques like UHPLC-MS/MS has enabled the precise identification of lipid species that are significantly altered in patients with coexisting diabetes and hyperuricemia (DH) compared to those with diabetes alone (DM) or healthy controls (NGT). The table below summarizes the most relevant lipid biomarkers identified in a recent clinical study [10].

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Molecules in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperuricemia (DH)

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Molecules | Trend in DH vs. NGT | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significantly Upregulated | Key energy reservoirs; elevated levels indicate disrupted energy storage and lipid overload. |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significantly Upregulated | Major constituents of cell membranes; influence membrane fluidity and cell signaling. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significantly Upregulated | Essential for lipoprotein structure and lipid transport; alterations linked to insulin resistance. |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | One unspecified PI | Significantly Downregulated | Precursor for second messengers; downregulation may disrupt intracellular signaling cascades. |

The study identified a total of 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in the DH group compared to healthy controls, with a strong predominance of upregulated species [10]. A separate comparison between DH and DM-only groups further pinpointed 12 differential lipids, confirming that the lipidomic profile of the comorbid condition is distinct and not merely an extension of diabetes-related lipid disturbances [10]. The consistent upregulation of specific TGs like TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) underscores their potential role as central mediators in the disease process.

Disrupted Metabolic Pathways: A Systems Biology View

The identified differential lipid metabolites are not isolated entities; they are interconnected components of specific biological pathways. Pathway enrichment analysis using platforms like MetaboAnalyst 5.0 has revealed that these lipids are predominantly enriched in a limited number of core metabolic pathways, highlighting their systemic impact [10].

Table 2: Key Perturbed Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

| Metabolic Pathway | Impact Value | Key Lipid Classes Involved | Pathological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid Metabolism | 0.199 | PEs, PCs, PI | Most significantly perturbed pathway; crucial for cell membrane integrity, signaling, and inflammation. |

| Glycerolipid Metabolism | 0.014 | TGs, DAGs | Central to energy homeostasis; dysregulation directly contributes to lipid accumulation and insulin resistance. |

The glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway, with the highest impact value, is critically involved in maintaining cellular membrane structure and function. Its disruption can affect insulin receptor signaling and promote inflammatory processes. Concurrently, abnormalities in glycerolipid metabolism, primarily involving triglycerides, reflect a fundamental disturbance in energy storage and utilization, a hallmark of both diabetes and hyperuricemia [10]. This pathway-centric view is supported by independent research in hyperuricemic populations, which also found significant enrichment in glycerophospholipid metabolism, affirming its central role in HUA-related lipid disorders [8] [16].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected nature of these disrupted pathways and their relationship to the core pathophysiology of hyperuricemia and diabetes:

Diagram 1: Pathway Crosstalk in Hyperuricemia and Diabetes. This diagram maps the core pathophysiological drivers (HUA, DM) through intermediate mechanisms (insulin resistance, oxidative stress) to the dysregulation of key lipid metabolic pathways, resulting in the specific lipid biomarkers identified and culminating in exacerbated systemic metabolic dysfunction.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Lipidomic Analysis

The discovery of these biomarkers relies on robust, sensitive, and reproducible lipidomic workflows. The following section details the standard protocol for plasma untargeted lipidomics, as applied in the cited research [10] [8].

Sample Collection and Pre-processing

- Blood Collection: Collect ~5 mL of fasting venous blood into sodium heparin or EDTA tubes.

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge whole blood at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Aliquot the upper plasma layer (e.g., 0.2 mL) into cryotubes and immediately store at -80°C until analysis.

- Quality Control (QC) Preparation: Pool equal volumes of plasma from all study samples to create a quality control (QC) sample, which is used to monitor instrumental performance throughout the analytical run.

Lipid Extraction

The following steps should be performed on ice or at 4°C using pre-cooled solvents to minimize lipid degradation [10] [8]:

- Thawing: Thaw plasma samples on ice.

- Aliquot: Transfer 100 μL of plasma into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Protein Precipitation: Add 200 μL of ice-cold water and 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol. Vortex thoroughly.

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction: Add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). Vortex vigorously for 1 minute and sonicate in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes.

- Phase Separation: Let the mixture stand at room temperature for 30 minutes, then centrifuge at 14,000 g at 10°C for 15 minutes.

- Organic Phase Collection: Carefully collect the upper organic phase.

- Drying and Reconstitution: Dry the organic extract under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. Reconstitute the dried lipid residue in 100-200 μL of isopropanol/acetonitrile (e.g., 90:10 v/v) or a similar suitable solvent for MS analysis. Centrifuge again before injection to remove any insoluble material.

Instrumental Analysis: UHPLC-MS/MS Conditions

Chromatography (UHPLC)

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 or CSH C18 (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm).

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water.

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol.

- Gradient Elution: Utilize a linear gradient from 30% B to 100% B over 20-25 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 45°C.

- Injection Volume: 3-5 μL.

Mass Spectrometry (Tandem MS - Q-TOF)

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), operating in both positive and negative ion modes.

- Source Parameters:

- Sheath Gas Flow: 45 arb

- Auxiliary Gas Flow: 15 arb

- Spray Voltage: 3.0 kV (positive), 2.5 kV (negative)

- Capillary Temperature: 350°C

- Heater Temperature: 300-400°C

- Data Acquisition: Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. A full MS1 scan (e.g., m/z 200-1800) is followed by MS2 scans of the top N most intense precursor ions using High-Energy Collisional Dissociation (HCD).

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of this lipidomic analysis:

Diagram 2: Untargeted Lipidomics Workflow. The process from sample collection through lipid extraction, quality control, instrumental analysis, and data processing leading to biomarker identification and pathway analysis.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

- Peak Picking and Alignment: Process raw LC-MS data using software (e.g., MarkerLynx, MS-DIAL) to perform peak detection, alignment, and integration, generating a data matrix of m/z, retention time, and peak intensity.

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Import the data matrix into software like SIMCA-P.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): An unsupervised method to overview data clustering and identify outliers.

- Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA): A supervised method to maximize separation between pre-defined groups (e.g., DH vs. DM) and identify significant lipid features (Variables Important in Projection, VIP > 1.0).

- Biomarker Identification: Combine significant statistical results (VIP > 1.0 and p-value < 0.05 from univariate t-tests) with MS/MS spectral data to identify lipid structures by querying databases such as LIPID MAPS and HMDB.

- Pathway Analysis: Input the list of identified differential lipids into pathway analysis tools (e.g., MetaboAnalyst 5.0) to determine enriched metabolic pathways based on pathway impact and p-values.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists critical reagents and materials required to establish the described lipidomic workflow, based on the methodologies from the cited studies [10] [8] [16].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics

| Category / Item | Specific Example / Specification | Critical Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 / CSH C18 (2.1x100mm, 1.7μm) | High-resolution separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to MS detection. |

| Mass Spectrometry System | Q-Exactive Plus / Xevo G2-S Q-TOF (Orbitrap/Tof mass analyzer) | Provides high mass accuracy and resolution for precise lipid identification and structural elucidation via MS/MS. |

| Key Solvents | HPLC/LC-MS grade: Methanol, Acetonitrile, Isopropanol, MTBE, Water, Chloroform | Used for mobile phases and lipid extraction; high purity is critical to minimize background noise and ion suppression. |

| Additives for LC-MS | Ammonium Formate, Formic Acid | Volatile buffers and pH modifiers for mobile phases to enhance ionization efficiency and chromatographic separation. |

| Sample Preparation | Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Nitrogen Evaporator, Low-Temperature Centrifuge, Vortex Mixer | Enables efficient liquid-liquid extraction of a broad lipidome, concentration of samples, and preparation for injection. |

| Data Analysis Software | SIMCA-P (Multivariate Stats), MS-DIAL / Lipostar (Lipid ID), MetaboAnalyst (Pathway Analysis) | Tools for statistical analysis, lipid annotation, and biological interpretation of high-dimensional lipidomic data. |

| Ethyl 3-oxoheptanoate | Ethyl 3-oxoheptanoate, CAS:7737-62-4, MF:C9H16O3, MW:172.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Lactose monohydrate | D-Lactose monohydrate, CAS:5989-81-1, MF:C12H22O11.H2O, MW:360.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Lipidomics has unequivocally demonstrated that the pathophysiological interplay between diabetes and hyperuricemia is reflected in a distinct plasma lipid signature. The specific upregulation of lipids like TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and PE(18:0/20:4), along with the central disruption of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism, provides a molecular rationale for the exacerbated clinical outcomes observed in patients with this comorbidity. These findings move the field beyond uric acid, offering a new panel of potential biomarkers for early risk stratification, disease monitoring, and assessing therapeutic efficacy.

Future research must focus on the translational validation of these lipidomic signatures in larger, multi-center cohorts to establish standardized reference ranges and clinical cut-off values. Furthermore, integrating lipidomics with other omics data (genomics, proteomics) will paint a more complete picture of the regulatory networks at play. From a therapeutic perspective, these specific lipid pathways and species represent novel targets for the development of "dual-action" interventions designed to concurrently ameliorate hyperuricemia and improve glycemic and lipid control, ultimately paving the way for a more precise and effective management strategy for this complex metabolic syndrome.

Lipid metabolites serve as pivotal signaling molecules that orchestrate immune responses and modulate oxidative stress, creating a pathological bridge between metabolic dysfunction and chronic inflammation. In the context of hyperuricemia and diabetes, this interplay becomes increasingly complex, driving disease progression through well-defined immunometabolic pathways. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on how specific lipid classes—including fatty acids, phospholipids, and cholesterol—influence immune cell function, activate inflammatory signaling cascades, and exacerbate oxidative stress. We present comprehensive experimental data, detailed methodologies for investigating these relationships, and visualizations of key pathological mechanisms. Understanding these processes provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions that disrupt the inflammatory bridge in patients with coexisting hyperuricemia and diabetes.

Lipid metabolism has evolved from being viewed primarily as an energy storage and structural framework to recognized as a sophisticated signaling network that actively directs immune cell differentiation, activation, and inflammatory potential. In metabolic diseases including hyperuricemia and diabetes, dysregulated lipid metabolism creates a pro-inflammatory milieu that accelerates tissue damage and disease progression [17] [18]. The "inflammatory bridge" concept describes how lipid metabolites activate immune responses and oxidative stress through three primary mechanisms: (1) direct receptor-mediated signaling, (2) modulation of membrane fluidity and lipid raft organization, and (3) generation of oxidative stress through lipid peroxidation.

The coexistence of hyperuricemia and diabetes represents a particularly aggressive metabolic phenotype characterized by amplified inflammatory responses. Epidemiological studies demonstrate that approximately 21-32% of patients with type 2 diabetes have concomitant hyperuricemia, creating a population with enhanced risk for renal and cardiovascular complications [9]. This clinical synergy stems from shared pathophysiological mechanisms, with disordered lipid metabolism serving as a central connector.

Core Mechanisms: Lipid-Mediated Immune and Oxidative Activation

Lipid Metabolites as Immune Signaling Molecules

Specific lipid classes function as potent signaling molecules that directly activate immune pathways:

Fatty Acids and Eicosanoids: Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., arachidonic acid) give rise to eicosanoid mediators (prostaglandins, leukotrienes) that promote pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization and enhance neutrophil recruitment [17]. In contrast, specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) derived from omega-3 fatty acids orchestrate inflammation resolution.

Sphingolipids: The balance between ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) determines immune cell fate. Ceramide promotes apoptosis and inflammatory activation, while S1P regulates lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs and endothelial barrier function [17].

Phospholipids: Glycerophospholipids including phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) are remodeled to produce platelet-activating factor (PAF) and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which activate platelets and innate immune cells [10].

Table 1: Pro-inflammatory Lipid Mediators and Their Immune Functions

| Lipid Class | Specific Mediators | Immune Functions | Receptors/Signaling Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eicosanoids | PGEâ‚‚, LTBâ‚„ | Neutrophil chemotaxis, Vasodilation, Fever | GPCRs (EP, BLT receptors) |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramide, S1P | Apoptosis, Lymphocyte trafficking | Ceramide-activated protein kinases, S1PR1-5 |

| Phospholipids | PAF, LPA | Platelet activation, Monocyte adhesion | PAFR, LPAR1-6 |

| Oxidized Lipids | oxLDL, 4-HNE | Scavenger receptor activation, Protein adduction | CD36, TLR4, KEAP1-Nrf2 |

Membrane Lipid Composition and Immune Receptor Signaling

Beyond soluble mediators, lipids shape immune responses by influencing membrane properties:

Lipid Rafts: Cholesterol and sphingolipid-enriched microdomains serve as signaling platforms that concentrate immune receptors like the T-cell receptor (TCR) and B-cell receptor (BCR). Increased membrane cholesterol content lowers the activation threshold of T cells, promoting hyperactivation as observed in autoimmune conditions [17].

Metabolic Sensors: Nuclear receptors including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and liver X receptors (LXRs) function as lipid sensors that transcriptionally reprogram immune cell function. PPARγ promotes anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization, while its inhibition favors pro-inflammatory M1 phenotypes [17] [18].

Lipid-Induced Oxidative Stress

Lipid overload and metabolism directly contribute to oxidative stress through multiple mechanisms:

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Excess fatty acid oxidation increases electron transport chain activity, leading to electron leakage and superoxide production [19].

NADPH Oxidase Activation: Several lipid mediators directly activate NOX enzyme complexes, which deliberately produce superoxide for inflammatory signaling [19].

Lipid Peroxidation: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) attack polyunsaturated fatty acids in membranes, generating reactive aldehydes like 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA) that amplify oxidative damage by modifying proteins and DNA [19].

In hyperuricemia, uric acid crystals themselves activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, further stimulating ROS production and creating a vicious cycle of inflammation and metabolic dysfunction [14].

Experimental Evidence: Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Distinct Lipidomic Profiles in Clinical Populations

Recent advances in lipidomics have enabled detailed characterization of lipid disturbances in metabolic diseases. A 2025 study employing UHPLC-MS/MS-based plasma untargeted lipidomic analysis revealed striking differences between patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), and healthy controls [10].

Table 2: Significantly Altered Lipid Species in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia (DH) vs. Healthy Controls

| Lipid Subclass | Specific Molecules | Change in DH | Proposed Pathological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2), TG(16:0/18:1/20:4) | ↑ 1.5-2.3 fold | Energy storage, Lipotoxicity precursor |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4), PE(16:0/18:2) | ↑ 1.8-2.1 fold | Membrane fluidity, Inflammatory precursor |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1), PC(34:2) | ↑ 1.3-1.7 fold | Structural membrane lipid |

| Phosphatidylinositols (PIs) | PI(18:0/20:4) | ↓ 1.9 fold | Signaling precursor impairment |

This study identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in the DH group compared to healthy controls. Multivariate analyses revealed clear separation between groups, confirming distinct lipidomic profiles [10]. Pathway analysis demonstrated that glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) were the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [10].

Experimental Protocol: UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

For researchers investigating lipidomic profiles in metabolic diseases, the following methodology provides a robust approach [10]:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect 5 mL of fasting blood in EDTA tubes and centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Aliquot 0.2 mL of plasma into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes.

- Prepare quality control samples by pooling equal volumes from all samples.

- Store samples at -80°C until analysis.

- Thaw samples on ice and vortex thoroughly.

- Extract lipids using methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) method: Add 200 μL of 4°C water to 100 μL plasma, followed by 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol and 800 μL MTBE.

- Sonicate in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes, then stand at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C.

- Collect upper organic phase and dry under nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitute in isopropanol for analysis.

UHPLC-MS/MS Conditions:

- Chromatography: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water; B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol

- Gradient: Optimized linear gradient from 30% B to 100% B over 15 minutes

- Mass Spectrometry: High-resolution tandem mass spectrometry in both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes

- Data Processing: Use software such as LipidSearch, MS-DIAL, or XCMS for peak alignment, identification, and quantification

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) to visualize group separation

- Identify significantly altered lipids using Student's t-test with false discovery rate (FDR) correction

- Conduct pathway analysis using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 or similar platforms

Figure 1: The Inflammatory Bridge Pathway in Hyperuricemia and Diabetes. Lipid metabolism dysregulation serves as a central node connecting hyperuricemia and diabetes to immune activation and oxidative stress, ultimately driving chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

Immunometabolic Reprogramming in Specific Immune Cells

Macrophage Polarization and Lipid Metabolism

Macrophages exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity during polarization, with lipid metabolism playing a decisive role:

M1 Macrophages: Classically activated pro-inflammatory macrophages rely predominantly on glycolysis and exhibit disrupted TCA cycle with accumulation of succinate and citrate, which stabilizes HIF-1α and drives IL-1β production [18]. Fatty acid synthesis is increased in M1 macrophages, providing membranes for proliferation and organelles.

M2 Macrophages: Alternatively activated anti-inflammatory macrophages preferentially utilize oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) [18]. PPARγ and PPARδ activation promotes FAO and M2 polarization, facilitating inflammation resolution.

In hyperuricemia, uric acid crystals are phagocytosed by macrophages, activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and promoting IL-1β secretion, which represents a key link between hyperuricemia and inflammation [14].

T Cell Differentiation and Function

T cell subsets demonstrate distinct lipid metabolic programs that dictate their differentiation and functional capacities:

Effector T Cells: Upon activation, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells increase both glycolysis and fatty acid synthesis to support rapid proliferation and effector function [17].

Regulatory T Cells (Tregs): Tregs primarily rely on oxidative metabolism, particularly fatty acid oxidation, which supports their survival and suppressive function [17] [18].

Memory T Cells: Like Tregs, memory T cells depend on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation for long-term persistence [17].

Cholesterol metabolism critically regulates T cell function by modulating membrane lipid raft composition and TCR signaling intensity. Increased cellular cholesterol content lowers the activation threshold of T cells, contributing to autoimmunity [17].

Figure 2: Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Macrophage Polarization. M1 and M2 macrophages utilize distinct lipid metabolic programs that drive their inflammatory versus anti-inflammatory functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immunometabolism Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Chloroform:methanol | Lipidomics sample preparation | MTBE method provides better phase separation than Folch |

| Chromatography Columns | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (1.7 μm) | Lipid separation prior to MS | Suitable for broad lipid classes; specialized columns needed for specific lipids |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX, Avanti Polar Lipids standards | Lipid identification and quantification | Essential for both targeted and untargeted lipidomics |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Etomoxir (CPT1 inhibitor), C75 (FASN inhibitor) | Manipulating lipid pathways in cells | Confirm specificity with rescue experiments |

| Immune Cell Markers | CD86 (M1), CD206 (M2), FOXP3 (Tregs) | Immune phenotyping by flow cytometry | Combine surface and intracellular staining for comprehensive profiling |

| ROS Detection Probes | H2DCFDA, MitoSOX, Amplex Red | Measuring oxidative stress | Use specific probes for different ROS types and compartments |

| Lipid Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | GW9662 (PPARγ antagonist), FTY720 (S1PR modulator) | Studying lipid signaling pathways | Titrate carefully due to potential off-target effects |

| Biliverdin hydrochloride | Biliverdin hydrochloride, CAS:55482-27-4, MF:C33H36Cl2N4O6, MW:655.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| L-Histidine dihydrochloride | L-Histidine dihydrochloride, CAS:6027-02-7, MF:C6H11Cl2N3O2, MW:228.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting the inflammatory bridge represents a promising therapeutic strategy for patients with hyperuricemia and diabetes. Several approaches show particular promise:

PPARγ Agonists: Thiazolidinediones not only improve insulin sensitivity but also promote M2 macrophage polarization, potentially disrupting the inflammatory cascade [17] [18].

SGLT2 Inhibitors: Drugs like empagliflozin reduce both glucose and uric acid levels while demonstrating anti-inflammatory effects, representing a dual-action approach [9].

Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators: Administration of resolvins, protectins, and maresins directly promotes inflammation resolution without immunosuppression [17].

NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors: Targeting uric acid crystal-induced inflammation may break the cycle between hyperuricemia and metabolic dysfunction [14].

Future research should focus on tissue-specific lipidomic signatures, the gut-liver axis in lipid metabolism, and personalized approaches based on individual lipidomic profiles. The development of more specific inhibitors targeting key enzymes in lipid mediator synthesis (e.g., COX-2, SphK) may provide enhanced therapeutic efficacy with reduced side effects.

Lipid metabolites serve as essential connectors between metabolic diseases and immune dysfunction, creating an "inflammatory bridge" that propagates and amplifies tissue damage in hyperuricemia and diabetes. Through multiple mechanisms—including direct receptor activation, membrane reorganization, and oxidative stress generation—dysregulated lipid metabolism establishes a pro-inflammatory milieu that drives disease progression. Advanced lipidomic methodologies now enable detailed characterization of these disturbances, revealing specific lipid signatures and perturbed pathways. Therapeutic strategies that target these lipid-immune interfaces hold significant promise for interrupting the pathological cascade and improving outcomes in this high-risk patient population.

Advanced Analytical Techniques: Applying Lipidomics and Multi-Omics to Decipher Metabolic Dysfunction

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has become a cornerstone technique in modern lipidomics, enabling the precise separation, identification, and quantification of complex lipid mixtures from biological samples [20]. This technical guide details the established workflows from sample preparation to data acquisition, with a specific focus on applications in lipid metabolic pathway research for patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (DH). Dysregulated lipid metabolism is a hallmark of metabolic diseases, and studies have revealed that patients with DH exhibit significant alterations in lipid species like triglycerides (TGs) and glycerophospholipids, alongside perturbations in key metabolic pathways such as glycerophospholipid metabolism [10]. The robustness of UHPLC-MS/MS allows researchers to uncover these critical disease-specific lipid signatures, providing a deeper understanding of the underlying pathophysiology [10] [21].

Core UHPLC-MS/MS Workflow in Lipidomics

The typical lipidomics workflow involves several critical and sequential steps to ensure data quality and reliability.

Sample Collection and Preparation

Proper sample preparation is the foundation for successful lipidomic analysis. For plasma or serum samples, fasting blood is collected and centrifuged to isolate the supernatant, which is then stored at -80°C until analysis [10] [21].

- Lipid Extraction: A liquid-liquid extraction is commonly performed to isolate lipids from the biological matrix. The methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)-based method is widely adopted for its high extraction yield, compatibility with a broad range of lipid classes, and lower toxicity compared to halogenated solvents [22]. Briefly, a sample aliquot (e.g., 100 μL of plasma) is mixed with methanol and MTBE, followed by sonication, incubation, and centrifugation. The upper organic phase containing the lipids is then collected and dried under a stream of nitrogen [10] [22].

- Quality Control (QC): To monitor analytical performance and ensure data reproducibility, a pooled quality control (PQC) sample is created by combining equal aliquots of all study samples. This PQC is injected at regular intervals throughout the acquisition sequence to assess instrument stability, signal drift, and precision [23] [24]. The use of commercial plasma as a surrogate for pooled study samples for long-term QC has also been evaluated [23].

Chromatographic Separation (UHPLC)

Chromatographic separation prior to mass spectrometry reduces ion suppression and enhances sensitivity by separating isobaric and isomeric lipids.

- Column: Reversed-phase chromatography on a C18 column (e.g., 100 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) is standard. The use of sub-2 μm fully porous or core-shell particles enables high resolution at elevated pressures [10] [22]. Charged Surface Hybrid (CSH) columns can further improve peak shape for acidic lipids [22].

- Mobile Phase and Gradient: A binary solvent system is typical. Mobile phase A is often water or an aqueous buffer with additives like ammonium formate or acetate, while mobile phase B is an organic solvent like acetonitrile-isopropanol mixture [10] [25]. The analysis uses a gradient elution, starting with a low percentage of B and ramping to over 95% B to elute the full range of lipids, from polar phospholipids to non-polar cholesteryl esters and triacylglycerols [25]. Advanced methods have successfully reduced total chromatographic run times to as little as 4-12 minutes while maintaining robust lipid coverage [22] [25].

Table 1: Typical UHPLC Gradient for Comprehensive Lipidomics

| Time (min) | Mobile Phase B (%) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 35-40% | Initial condition, elution of lysophospholipids |

| 2.0 | 80% | Elution of phospholipids and sphingolipids |

| 7.0 | 100% | Elution of diacylglycerols and ceramides |

| 7 - 14 | 100% (Hold) | Elution of triacylglycerols and cholesteryl esters |

| 14 - 16 | 35-40% | Column re-equilibration |

Mass Spectrometric Detection (MS/MS)

MS detection provides the high sensitivity and specificity needed for lipid identification and quantification.

- Ionization Source: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is the most prevalent soft ionization technique due to its efficiency in ionizing a wide range of lipid classes. It can be operated in both positive and negative ion modes to achieve comprehensive coverage of the lipidome [26].

- Mass Analyzers: High-resolution mass analyzers are preferred for untargeted lipidomics. Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (QTOF) and Orbitrap instruments deliver the high mass accuracy and resolution required to determine elemental compositions [10] [25]. For targeted quantification, triple quadrupole (QqQ) instruments operating in Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) or Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) modes offer superior sensitivity and dynamic range [26].

- Data Acquisition Modes:

- Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA): In this common untargeted approach, the instrument first performs an MS1 survey scan and then automatically selects the most abundant precursor ions for fragmentation (MS2), providing structural information [22].

- Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA): Methods like Sequential Window Acquisition of all Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH) fragment all ions within sequential isolation windows, capturing fragmentation data for all detectable analytes and allowing retrospective data mining [22].

- Ion Mobility Separation: The integration of Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TIMS) adds a fourth dimension of separation based on the ion's collision cross-section (CCS). This helps separate isomeric lipids and provides a CCS value, a physicochemical property that increases confidence in lipid identification [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from sample to data, incorporating key decision points and outputs.

Application in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia Research