Lipidomics Biomarker Discovery in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia: From Pathophysiological Insights to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of lipidomics in the context of the co-occurrence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA), a prevalent and clinically significant metabolic constellation.

Lipidomics Biomarker Discovery in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia: From Pathophysiological Insights to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of lipidomics in the context of the co-occurrence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA), a prevalent and clinically significant metabolic constellation. We synthesize foundational research identifying distinct lipidomic signatures, including upregulated triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and diacylglycerols (DAGs), and the central disruption of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways. The content details advanced methodological approaches, such as UHPLC-MS/MS, for biomarker discovery and validation, while also addressing key challenges in reproducibility and clinical integration. Furthermore, we examine comparative studies that stratify lipidomic profiles across disease stages and patient subgroups, and discuss the translational potential of these findings for developing diagnostic tools, informing therapeutic strategies like dietary interventions, and advancing personalized medicine for complex metabolic disorders.

Unraveling the Lipidomic Landscape: Core Signatures and Pathways in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Comorbidity

In the evolving landscape of metabolic disease research, lipidomics has emerged as a powerful tool for uncovering the complex alterations in lipid metabolism that underpin conditions like diabetes mellitus and hyperuricemia. The comprehensive analysis of lipid classes—including triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), and diacylglycerols (DAGs)—provides critical insights into disease mechanisms and potential biomarker discovery [1]. These lipid classes are not merely energy storage molecules but play active roles in cellular signaling, membrane integrity, and metabolic regulation, making them prime targets for investigation in the context of diabetes and its common comorbidities [1] [2].

The integration of lipidomic data with clinical parameters offers a multidimensional perspective on disease pathophysiology. For instance, the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, calculated from fasting triglycerides and glucose levels, has gained recognition as a reliable surrogate marker of insulin resistance and predictor of diabetic complications [3] [4] [5]. This intersection of traditional clinical measures with advanced lipidomic profiling creates a powerful framework for understanding the complex interplay between lipid metabolism and metabolic diseases, potentially leading to improved diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic strategies.

Key Altered Lipid Classes in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Quantitative Alterations in Lipid Classes

Table 1: Key Lipid Class Alterations in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Lipid Class | Specific Molecular Species | Alteration Trend | Biological Context | Potential Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs [6] | Significantly upregulated [6] | Diabetes with hyperuricemia (DH) vs. healthy controls | Hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, ectopic fat deposition [7] [2] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs [6] | Significantly upregulated [6] | DH vs. healthy controls | Membrane fluidity alterations, signaling pathway disruption |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs [6] | Significantly upregulated [6] | DH vs. healthy controls | Impaired cell signaling, membrane integrity compromise |

| Diacylglycerols (DAGs) | 1,3-DAG species [2] | Accumulated in skeletal muscle | Prediabetic insulin resistance | PKC activation, impaired insulin signaling [2] |

| Ceramides (CERs) | CER(18:0, 22:0, 24:0, 24:1) [2] | Significantly increased | Skeletal muscle in prediabetes | Attenuated insulin signaling, insulin resistance [2] |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not specified [6] | Downregulated | DH vs. healthy controls | Disrupted cellular signaling processes |

Table 2: Lipid Ratios and Derived Indices in Metabolic Research

| Parameter | Calculation Method | Clinical/Research Utility | Association with Disease States |

|---|---|---|---|

| TyG Index | Ln[fasting TGs (mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2] [3] [4] | Surrogate marker of insulin resistance [3] [4] | Predictor of diabetic retinopathy (OR: 1.57-1.89) [3], cerebrovascular diseases [4] |

| HOMA-IR | (Fasting insulin × fasting glucose)/405 [5] | Assessment of insulin resistance | Limited value in insulin-treated patients [5] |

| DAG Species Ratio | 1,3-DAG/1,2-DAG [2] | Marker of lipotoxicity | Associated with skeletal muscle insulin resistance [2] |

Pathophysiological Significance of Altered Lipid Classes

The dysregulation of specific lipid classes represents not merely a secondary consequence but an active contributor to metabolic disease progression. Triglycerides serve as the most abundant energy reservoir, yet their ectopic accumulation in non-adipose tissues induces lipotoxicity, a fundamental mechanism driving insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in diabetes [7] [2]. The recently recognized TyG index, incorporating both triglyceride and glucose measurements, has demonstrated significant predictive value for microvascular complications such as diabetic retinopathy, with pooled odds ratios of 1.89 (categorical) and 1.57 (continuous) according to a recent meta-analysis [3].

Phosphatidylethanolamines and phosphatidylcholines are fundamental structural components of cellular membranes, and their alteration directly impacts membrane fluidity, signaling transduction, and cellular integrity. The simultaneous upregulation of both PE and PC subclasses in diabetes with hyperuricemia suggests profound membrane remodeling occurs in this comorbid condition [6]. Diacylglycerols function as crucial signaling molecules that activate protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, leading to the phosphorylation and inhibition of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), thereby disrupting the insulin signaling cascade at a critical node [2]. This mechanism establishes DAGs as central mediators of insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, particularly skeletal muscle.

Experimental Methodologies in Lipidomics Research

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Lipidomics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) | Separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to mass analysis [6] | Untargeted lipidomics of plasma samples [6] |

| Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) | Structural identification and quantification of lipid species [6] [1] | Differential lipid molecule identification [6] |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction from biological samples [6] | Plasma lipid extraction in diabetes with hyperuricemia study [6] |

| Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) Mass Spectrometer | High-resolution mass accuracy for lipid identification [8] | Lipidomic profiling in diabetic kidney disease [8] |

| C18 Chromatography Column | Reverse-phase separation of lipid molecules [6] | UHPLC separation of lipid classes [6] |

| Precooled Methanol | Protein precipitation and lipid stabilization [6] | Sample pre-processing in plasma lipidomics [6] |

The foundation of reliable lipidomics research lies in robust sample preparation protocols. For plasma lipid analysis, the recommended approach involves collecting fasting blood samples in appropriate anticoagulant tubes, followed by immediate centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma [6]. The resulting plasma supernatant should be aliquoted and stored at -80°C until analysis to prevent lipid degradation. For lipid extraction, the methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) method has demonstrated excellent performance: briefly, 100 μL of plasma is mixed with 200 μL of 4°C water, followed by addition of 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol and 800 μL of MTBE [6]. After low-temperature sonication for 20 minutes and room temperature incubation for 30 minutes, centrifugation at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C yields distinct phases, with the upper organic phase containing the extracted lipids ready for nitrogen drying and subsequent analysis [6].

Lipidomic Analysis Techniques

Untargeted lipidomics employing ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) represents the gold standard for comprehensive lipid profiling. The analytical conditions typically utilize a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) with a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile-water (10 mM ammonium formate) and acetonitrile-isopropanol (10 mM ammonium formate) in a gradient elution [6]. Mass spectrometry parameters should be optimized for broad lipid coverage, with both positive and negative ionization modes to capture the diverse lipid classes. Data processing utilizes specialized software platforms (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar) for peak alignment, identification, and quantification, though recent studies indicate concerning variability, with agreement rates as low as 14-36% across different platforms [1].

For specific investigation of diacylglycerol and ceramide species in tissues, additional methodologies are required. Skeletal muscle samples should be powdered under liquid nitrogen and extracted in dichloromethane-methanol, followed by thin-layer chromatography separation using hexane-diethylether-acetic acid (70:30:1) as the solvent system [2]. The isolated DAG bands can then be scraped, extracted, and quantified enzymatically, providing specific information about different DAG isomers that may have distinct signaling roles in insulin resistance [2].

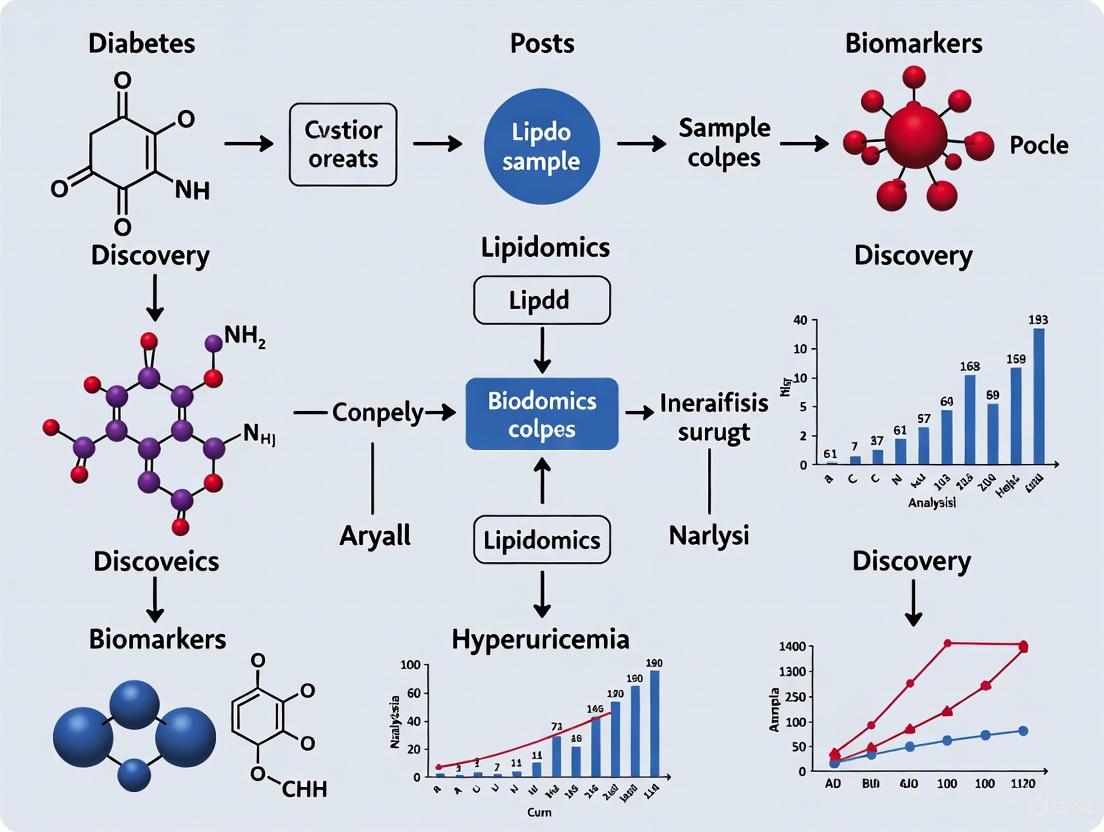

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Lipidomics Workflow and Key Lipid Classes. This diagram illustrates the standardized experimental workflow for lipidomics research, from sample collection to biomarker validation, and highlights the four key lipid classes frequently altered in diabetes and hyperuricemia.

Metabolic Pathways and Signaling Mechanisms

Disrupted Metabolic Pathways

Lipidomic analyses of diabetes with hyperuricemia have identified two primary metabolic pathways consistently disrupted: glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) [6]. These pathways represent the core metabolic disturbances underlying the observed lipid class alterations, with glycerophospholipid metabolism being particularly significantly perturbed. The integration of these pathway analyses with quantitative lipid data provides a systems-level understanding of how diabetes and hyperuricemia jointly disrupt lipid homeostasis, creating a metabolically detrimental environment that promotes disease progression and complication development.

The accumulation of specific lipid species activates multiple intracellular signaling cascades that impair insulin action. Diacylglycerols activate protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, particularly PKCε and PKCθ, which phosphorylate insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) on inhibitory serine residues, reducing its ability to activate downstream PI3K/Akt signaling [2]. Concurrently, ceramides activate protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and protein kinase C ζ (PKCζ), which further attenuate Akt activation and promote insulin resistance through multiple mechanisms [2]. These parallel pathways create a self-reinforcing cycle of metabolic dysfunction that characterizes advanced diabetes and its complications.

Diagram 2: Lipid-Mediated Insulin Resistance Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates how accumulated lipid species (DAGs, ceramides) activate signaling kinases that disrupt normal insulin signal transduction, leading to insulin resistance. The TyG index, derived from triglycerides and glucose, serves as a clinical indicator of this metabolic dysfunction.

Implications for Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The consistent alteration patterns in specific lipid classes offer promising avenues for biomarker development in diabetes and hyperuricemia. The TyG index has already demonstrated clinical utility as a simple, cost-effective biomarker for insulin resistance and diabetic complications [3] [4] [5]. However, more sophisticated lipidomic signatures incorporating specific TG, PE, PC, and DAG species may provide enhanced diagnostic and prognostic precision. For instance, the identification of 31 significantly altered lipid molecules in diabetes with hyperuricemia, including 13 specific triglycerides, 10 phosphatidylethanolamines, and 7 phosphatidylcholines, provides a foundation for developing specialized biomarker panels for this common comorbidity [6].

From a therapeutic perspective, targeting lipid metabolism pathways represents a promising strategy. Interventions that reduce ectopic lipid accumulation, such as very low-calorie diets or bariatric surgery, have demonstrated efficacy in reversing insulin resistance and normalizing metabolic parameters, at least partially through reduction of intracellular DAG content and ectopic fat deposition [7]. Pharmacological approaches targeting specific enzymes in glycerophospholipid or glycerolipid metabolism pathways may offer more precise interventions for restoring lipid homeostasis in diabetes and hyperuricemia.

The comprehensive analysis of triglyceride, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and diacylglycerol classes provides invaluable insights into the pathological mechanisms underlying diabetes and hyperuricemia. The standardized methodologies presented here for lipidomic analysis, from sample preparation through mass spectrometric analysis and data processing, provide a rigorous framework for advancing research in this field. The integration of these lipidomic approaches with clinical indices like the TyG index creates a powerful multidimensional perspective on metabolic disease pathophysiology, offering promising avenues for improved diagnosis, risk stratification, and therapeutic development in diabetes and its related metabolic disorders.

The integration of lipidomics into metabolic disease research has revolutionized our understanding of pathological mechanisms underlying conditions like diabetes and hyperuricemia. Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, enables the comprehensive analysis of lipid molecules within biological systems, providing crucial insights into their structural, functional, and dynamic roles in health and disease [1]. The molecular structures of the majority of lipids determine their functions, with the Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy (LIPID MAPS) classification system organizing lipids into eight key categories: fatty acyls, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides [1]. Understanding how lipids are affected in various disorders provides essential information about disease mechanisms, potential biomarkers for diagnosis, and possible therapeutic targets [1].

Within the context of diabetes and hyperuricemia research, lipidomic approaches have revealed significant disruptions in specific metabolic pathways, particularly glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism. These perturbations are not merely consequences of disease states but may represent fundamental mechanistic links between these interconnected metabolic disorders. The transition of lipid research from bench to bedside relies heavily on the discovery of biomarkers that are clinically reliable, repeatable, and validated across various populations [1]. This technical guide explores the current state of knowledge regarding perturbed glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways within the broader thesis of lipidomics biomarker discovery for diabetes and hyperuricemia research, providing researchers with methodological frameworks, analytical approaches, and contextual interpretation for advancing this critical field.

Analytical Methodologies in Lipidomics

Untargeted versus Targeted Approaches

Lipidomics methodologies have advanced significantly with the development of targeted, untargeted, and pseudotargeted techniques that improve structural lipid profiling, resolution, and quantification. Untargeted lipidomics represents a powerful discovery-oriented approach that aims to detect and quantify all lipid species present in a biological sample, regardless of whether the lipid species of interest are known or unknown. This method provides a comprehensive picture of a sample's lipid profile, although it may be limited by lower sensitivity for low-abundance lipids and challenges in structural identification [1]. In contrast, targeted lipidomics focuses on precise identification and absolute quantification of a predefined set of lipids, offering higher sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility for specific lipid classes of interest [9]. The pseudotargeted approach represents a middle ground, beginning with untargeted analysis to identify differential lipids, then developing targeted methods for more accurate quantification of these specific candidates [1].

The complementary nature of these approaches is particularly valuable in diabetes and hyperuricemia research. Untargeted methods can reveal novel lipid signatures associated with disease states, while targeted validation ensures robust, reproducible quantification of promising biomarkers. For instance, in a study investigating hyperuricemia patients with hyperlipidaemia, researchers initially employed untargeted analysis to identify differential metabolites, followed by targeted validation to confirm these findings [10]. This sequential approach leverages the strengths of both methodologies while mitigating their respective limitations.

Technical Platforms and Instrumentation

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as the cornerstone technology for comprehensive lipidomic analysis in diabetes and hyperuricemia research. The technical specifications for lipidomic analysis typically involve:

Chromatographic Separation: Reversed-phase chromatography using C18 columns (e.g., Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) provides excellent separation of complex lipid mixtures. Mobile phases commonly consist of acetonitrile/water mixtures with ammonium formate or formic acid modifiers (mobile phase A) and isopropanol/acetonitrile mixtures with similar modifiers (mobile phase B) [11] [6]. The gradient elution typically progresses from higher aqueous content to predominantly organic solvent over 10-30 minutes, effectively separating lipid classes based on their hydrophobicity.

Mass Spectrometric Detection: High-resolution mass spectrometers, particularly Q-TOF (Quadrupole-Time of Flight) and Orbitrap instruments, provide accurate mass measurements crucial for lipid identification [6]. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on triple quadrupole instruments offers superior sensitivity for targeted quantification [9]. Electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative ion modes enables comprehensive detection of various lipid classes, with specific lipid species exhibiting preferential ionization in particular modes [11].

Table 1: Core Instrumentation for Lipidomic Analysis in Metabolic Disease Research

| Component | Specifications | Application in Diabetes/Hyperuricemia Research |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography | UHPLC system with C18 column (2.1×100mm, 1.7μm); column temperature 45°C; flow rate 0.2-0.3 mL/min | Separation of complex lipid mixtures from biological samples |

| Mass Spectrometry | Q-TOF, Orbitrap, or QqQ mass analyzers; ESI source; resolution >20,000 for TOF/Orbitrap | Identification and quantification of lipid species |

| Ionization Source | Electrospray ionization; positive/negative mode switching; source temperature 300-450°C; sheath gas flow 45 arb | Efficient ionization of diverse lipid classes |

| Data Acquisition | Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) for untargeted; MRM for targeted; mass range 200-1800 m/z | Comprehensive lipid profiling and targeted validation |

Sample Preparation Protocols

Standardized sample preparation is critical for reliable lipidomic results. The methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) extraction method has gained prominence for its efficiency in extracting a broad range of lipid classes [11] [6]. The protocol typically involves:

- Protein Precipitation: Addition of cold methanol to serum/plasma samples (typically 100μL sample + 300μL methanol) to precipitate proteins and initiate lipid extraction.

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction: Introduction of MTBE (800μL) followed by vortex mixing and sonication in a low-temperature water bath to facilitate complete lipid extraction.

- Phase Separation: Centrifugation (14,000g, 15min, 10°C) to separate organic and aqueous phases, with the upper organic phase containing the extracted lipids.

- Concentration and Reconstitution: Collection of the organic phase, drying under nitrogen gas, and reconstitution in isopropanol/acetonitrile mixtures compatible with reversed-phase LC-MS analysis [6].

This extraction method demonstrates excellent recovery for diverse lipid classes including glycerophospholipids, glycerolipids, and sphingolipids, all relevant to diabetes and hyperuricemia research. Quality control measures should include pooled quality control (QC) samples from all study samples, inserted regularly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument stability and data quality [9].

Lipidomic Alterations in Hyperuricemia and Diabetes

Glycerophospholipid Metabolism Disruptions

Glycerophospholipids, essential components of cellular membranes and signaling molecules, demonstrate consistent alterations in both hyperuricemia and diabetes. Multiple studies have identified significant perturbations in glycerophospholipid metabolism pathways in these metabolic disorders. In a comprehensive investigation of hyperuricemia patients, 33 differential lipid metabolites were significantly upregulated, with these metabolites prominently involved in arachidonic acid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis, and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism pathways [11]. The interconnection between these lipid alterations and immune factors was further established, with IL-10, CPT1, IL-6, SEP1, TGF-β1, Glu, TNF-α, and LD showing associations with glycerophospholipid metabolism [11].

In diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), more pronounced disturbances emerge. A targeted lipidomic analysis of 2247 middle-aged and elderly Chinese participants revealed 123 lipids significantly associated with uric acid levels, predominantly glycerolipids and glycerophospholipids [9]. Specific molecular species including diacylglycerols (DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5), DAG (18:1/22:6)), phosphatidylcholines (PC (16:0/20:5)), and triacylglycerols (TAG (53:0)) emerged as the most significant lipid signatures positively associated with hyperuricemia risk, while lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC (20:2)) was inversely associated with hyperuricemia risk [9]. Network analysis further strengthened these findings, showing a positive association between TAGs/PCs/DAGs contained module and hyperuricemia risk [9].

Table 2: Key Lipid Classes and Species Altered in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Lipid Class | Specific Species | Change in Disease | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC (16:0/20:5), PC (36:1) | Upregulated in DH [6] [9] | Membrane integrity, signaling precursors |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE (18:0/20:4) | Upregulated in DH [6] | Membrane curvature, cellular signaling |

| Diacylglycerols (DAGs) | DAG (16:0/22:5), DAG (16:0/22:6), DAG (18:1/20:5) | Upregulated in HUA/DH [9] | Insulin resistance, protein kinase C activation |

| Triacylglycerols (TAGs) | TAG (53:0) | Upregulated in HUA [9] | Energy storage, lipid droplet formation |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) | LPC (20:2) | Downregulated in HUA [9] | Anti-inflammatory signaling, metabolic regulation |

Glycerolipid Metabolism Perturbations

Glycerolipids, particularly triacylglycerols and diacylglycerols, show marked alterations in combined diabetes and hyperuricemia. In a UHPLC-MS/MS-based plasma untargeted lipidomic analysis comparing patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH) against those with diabetes alone (DM) and healthy controls (NGT), researchers identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses [6]. Multivariate analyses revealed significant separation trends among the DH, DM, and NGT groups, confirming distinct lipidomic profiles. Specifically, 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites were pinpointed in the DH group compared to NGT controls [6]. Among the most relevant individual metabolites, 13 triglycerides (TGs), 10 phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and 7 phosphatidylcholines (PCs) were significantly upregulated, while one phosphatidylinositol (PI) was downregulated [6].

Pathway analysis of these differential metabolites revealed their enrichment in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [6]. The comparison between DH and DM groups further identified 12 differential lipids that were also predominantly enriched in these same core pathways, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [6]. These findings highlight the synergistic disruption of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism in the comorbidity of diabetes and hyperuricemia, suggesting potential amplified metabolic dysfunction beyond either condition alone.

Pathway Interconnections and Network Analysis

The perturbations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism do not occur in isolation but rather within complex metabolic networks. Advanced network analysis has revealed significant associations between HUA-related lipids and de novo lipogenesis fatty acids, particularly 16:1n-7 (Spearman correlation coefficients = 0.32–0.41, p < 0.001) [9]. These correlations suggest coordinated regulation between lipid metabolic pathways in hyperuricemia, potentially mediated through transcription factors such as sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), which has been shown to be activated by uric acid in hepatocyte models [12].

Mediation analyses further suggest that lipid-HUA associations are partially mediated by retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), with mediation proportions ranging from 5–14% [9]. RBP4, an adipokine linked with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, may represent an important mechanistic connection between disturbed lipid metabolism and hyperuricemia. Dietary factors also modify these associations, with increased aquatic product intake correlated with elevated HUA risk and HUA-associated lipids, while high dairy consumption correlated with lower levels of HUA-associated lipids [9]. These findings highlight the multifactorial nature of lipid disruptions in hyperuricemia and diabetes, involving interactions between metabolic, endocrine, and dietary factors.

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Comprehensive Lipidomic Workflow

Diagram 1: Lipidomics workflow for biomarker discovery.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Sample Collection and Preparation Protocol:

- Collect fasting venous blood samples in EDTA-containing tubes

- Centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma/serum

- Aliquot and store at -80°C until analysis

- For lipid extraction, thaw samples on ice and vortex mix

- Precipitate proteins with cold methanol (sample:methanol ratio 1:3)

- Perform liquid-liquid extraction with MTBE (sample:MTBE ratio 1:8)

- Sonicate in low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes

- Centrifuge at 14,000g for 15 minutes at 10°C

- Collect upper organic phase and dry under nitrogen stream

- Reconstitute in 100μL isopropanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) for LC-MS analysis [11] [6]

LC-MS Analysis Conditions:

- Chromatography: UHPLC system with ACQUITY UPLC CSH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: A: 10mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water (6:4, v/v); B: 10mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol (2:9, v/v)

- Gradient Program: 30% B (0-2 min), 30-100% B (2-25 min), 100% B (25-30 min), 30% B (30-35 min)

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min; Column Temperature: 45°C; Injection Volume: 3-5μL

- Mass Spectrometry: Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer with ESI source

- Ionization Parameters: Sheath gas flow: 45 arb, Aux gas flow: 15 arb, Spray voltage: 3.0 kV (positive), 2.5 kV (negative), Capillary temperature: 350°C

- Scan Range: 200-1800 m/z; Resolution: 70,000 (MS1), 17,500 (MS2) [11] [6]

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis:

- Convert raw data to appropriate format (e.g., mzML)

- Perform peak detection, alignment, and retention time correction

- Normalize data using quality control-based robust LOESS signal correction

- Conduct multivariate statistical analysis including PCA and OPLS-DA

- Identify significant features with VIP >1.0 and p<0.05 (Student's t-test)

- Annotate lipids using LIPID MAPS and HMDB databases

- Perform pathway analysis using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 [6] [10]

Pathway Mapping and Metabolic Interconnections

Glycerophospholipid and Glycerolipid Pathway Disruptions

Diagram 2: Glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolic pathways.

The diagram above illustrates the complex metabolic network of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism, highlighting key enzymatic steps and intermediates. In both diabetes and hyperuricemia, multiple nodes within this network demonstrate significant alterations. The conversion of phosphatidic acid (PA) to diacylglycerol (DAG), catalyzed by phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase (PAP), represents a critical branch point that is dysregulated in these metabolic disorders [6] [9]. The subsequent conversion of DAG to triacylglycerol (TAG) by diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) is also significantly impacted, as evidenced by the elevated TAG species observed in hyperuricemia and diabetes [9].

The glycerophospholipid biosynthesis branch from CDP-diacylglycerol to various phospholipid classes, including phosphatidylglycerol, cardiolipin, and phosphatidylinositol, also shows substantial perturbations. Specifically, phosphatidylcholines (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) are consistently elevated in diabetes with hyperuricemia [6]. The remodeling of phosphatidylcholine to lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) is similarly affected, with specific LPC species demonstrating inverse associations with hyperuricemia risk [9]. These coordinated alterations suggest systemic dysregulation of lipid metabolic pathways rather than isolated enzyme defects, potentially reflecting broader disruptions in cellular energy metabolism, membrane biosynthesis, and signaling processes in diabetes and hyperuricemia.

Cross-Talk with Other Metabolic Pathways

The perturbations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism do not occur in isolation but exhibit significant cross-talk with other metabolic pathways. In hyperuricemia patients, lipidomic analyses have revealed concurrent disruptions in arachidonic acid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis [11]. This metabolic network extends to amino acid metabolism pathways, including alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, as well as phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis [10]. The interconnection between lipid metabolism and immune signaling is further highlighted by associations between specific lipid species and inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and TGF-β1 [11].

The mediation of lipid-hyperuricemia associations by retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) further demonstrates the endocrine dimension of these metabolic disruptions [9]. RBP4, primarily secreted from adipose tissue and liver, has been implicated in insulin resistance and represents a potential mechanistic link between dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia. The influence of dietary factors, including aquatic products and dairy consumption, on both lipid profiles and hyperuricemia risk underscores the multifactorial nature of these metabolic interrelationships [9]. This complex network of metabolic, endocrine, and dietary factors highlights the need for integrated, systems-level approaches to understanding lipid disruptions in diabetes and hyperuricemia.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipidomics in Metabolic Disease Research

| Category | Specific Items | Purpose/Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | EDTA blood collection tubes | Plasma preparation with minimized degradation | K2EDTA Vacutainers (BD) |

| Cryogenic vials | Long-term sample storage at -80°C | Nunc CryoStorage Tubes | |

| Lipid Extraction | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Liquid-liquid lipid extraction | HPLC grade, ≥99% purity |

| Methanol, acetonitrile, isopropanol | Solvent system for lipid extraction | LC-MS grade, 99.9% purity | |

| Ammonium formate | Mobile phase additive for LC-MS | MS-grade, 99.99% purity | |

| LC-MS Analysis | UPLC C18 columns | Chromatographic separation of lipids | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1×100mm, 1.7μm) |

| Mass spec standards | Quality control and quantification | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard | |

| Internal standards | Quantification normalization | Ceramide (d18:1-d7/15:0), Oleic acid-d9 | |

| Data Analysis | Reference standards | Lipid identification and confirmation | Avanti Polar Lipids standards |

| Software packages | Data processing and statistical analysis | MS-DIAL, Lipostar, SIMCA-P, MetaboAnalyst | |

| 6-Methoxypyridine-3-carbaldehyde | 6-Methoxypyridine-3-carbaldehyde, CAS:65873-72-5, MF:C7H7NO2, MW:137.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Erythronic acid potassium | Erythronic acid potassium, CAS:88759-55-1, MF:C4H7KO5, MW:174.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The mapping of perturbed glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways in diabetes and hyperuricemia represents a significant advancement in our understanding of the metabolic interconnections between these conditions. Lipidomics has revealed consistent alterations in specific lipid classes and species, providing insights into potential mechanistic links and biomarker candidates. The technical methodologies outlined in this guide, including standardized sample preparation, advanced LC-MS platforms, and comprehensive data analysis workflows, provide researchers with robust tools for further investigation in this field.

Future directions in this research area will likely focus on several key aspects. First, the integration of lipidomics with other omics technologies, including genomics, proteomics, and metagenomics, will provide more comprehensive insights into the systemic metabolic disruptions in diabetes and hyperuricemia [13]. Second, the implementation of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches for lipidomic data analysis shows promise for enhanced biomarker discovery and pathway analysis [1]. Finally, larger-scale validation studies across diverse populations will be essential for translating lipidomic findings into clinically applicable biomarkers and therapeutic targets. As these advancements unfold, the continued refinement of analytical methodologies and bioinformatic tools will further accelerate progress in understanding and addressing the complex metabolic disruptions in diabetes and hyperuricemia.

Linking Lipid Dysregulation to Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Lipid dysregulation represents a critical pathophysiological mechanism underlying a spectrum of metabolic, cardiovascular, neurological, and inflammatory disorders. This technical review examines the intricate interplay between disrupted lipid metabolism and disease pathogenesis, with particular emphasis on diabetes-hyperuricemia comorbidity as a model system. We synthesize evidence from lipidomic studies to elucidate how specific alterations in lipid species—including triglycerides, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids—drive disease processes through inflammatory signaling, oxidative stress, and immune-metabolic cross-talk. The integration of advanced lipidomic methodologies with biochemical and clinical data provides a powerful framework for identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets, ultimately advancing personalized medicine approaches for complex metabolic diseases.

Lipids constitute a diverse class of hydrophobic molecules essential for cellular structure, energy storage, and signaling processes. Lipid dysregulation, characterized by imbalances in lipid synthesis, metabolism, or trafficking, has emerged as a cornerstone pathology in numerous disease states [14]. Beyond its established role in cardiovascular disease, lipid dysregulation demonstrates significant involvement in neurological disorders, metabolic conditions, and immune-inflammatory pathologies through mechanisms that remain incompletely understood [14] [15] [16].

The pathophysiological impact of lipid dysregulation extends far beyond circulating cholesterol levels to encompass complex alterations in lipid species composition, membrane dynamics, and bioactive lipid signaling. Technological advances in lipidomics have revealed that specific lipid metabolites and profiles serve as sensitive indicators of disease states, often preceding clinical symptom onset [1]. This review examines how dysregulated lipid metabolism initiates and perpetuates disease processes across multiple organ systems, with special attention to the diabetes-hyperuricemia nexus as a paradigm for understanding broader lipid-mediated pathophysiological mechanisms.

Core Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Inflammatory Signaling and Immune Activation

Lipid dysregulation directly fuels inflammatory processes through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Elevated levels of specific lipid species, particularly ceramides and modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering caspase-1-mediated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [15]. This inflammatory cascade establishes a self-perpetuating cycle wherein cytokines further disrupt lipid homeostasis, amplifying tissue damage [15] [16].

In the context of metabolic disease, dyslipidemia characterized by elevated triglycerides and reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) promotes monocyte migration and endothelial activation through lysophosphatidylcholine-mediated G protein-coupled receptor signaling [15]. Clinical studies demonstrate that patients with major depressive disorder exhibiting lipid dysregulation show elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α, establishing a direct connection between lipid abnormalities and systemic inflammation [15]. Similar mechanisms operate in Alzheimer's disease, where lipid-driven microglial activation perpetuates neuroinflammation and accelerates neurodegeneration [16].

Metabolic Inflexibility and Insulin Resistance

Lipid dysregulation directly impairs insulin sensitivity through several well-characterized mechanisms. Excess circulating free fatty acids and intracellular accumulation of diacylglycerols and ceramides activate inflammatory kinases such as JNK and IKKβ, which phosphorylate insulin receptor substrate proteins on serine residues, blunting insulin signal transduction [17]. This metabolic inflexibility creates a pathological feedback loop wherein insulin resistance further exacerbates lipid abnormalities [17] [18].

In diabetes-hyperuricemia comorbidity, dysregulated lipid metabolism intersects with purine metabolism, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle of metabolic dysfunction. The uric acid-to-HDL cholesterol ratio (UHR) has emerged as a composite biomarker capturing this dysmetabolic state, with elevated UHR values significantly associated with abdominal aortic calcification and cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients [18]. Lipidomic analyses reveal that this metabolic synergy involves specific alterations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways [19].

Neuroinflammatory Pathways

The central nervous system exhibits particular vulnerability to lipid dysregulation, given its high lipid content and metabolic demands. Disruptions in brain cholesterol homeostasis and sphingolipid metabolism impair synaptic function, reduce membrane fluidity, and trigger neuroinflammatory responses [15] [16]. In major depressive disorder, patients demonstrate altered phospholipid metabolism with increased lysophosphatidylcholine and decreased alkyl phosphatidylethanolamine, creating a pro-oxidant, pro-inflammatory cerebral environment [15].

Lipid-mediated blood-brain barrier dysfunction represents another critical neuroinflammatory mechanism. Peripheral lipid abnormalities compromise barrier integrity through inflammatory cytokine release and oxidative stress, permitting infiltration of immune cells and inflammatory mediators into the CNS [15]. Once within the brain parenchyma, these factors activate microglia and astrocytes, establishing chronic neuroinflammation that disrupts mood regulation, cognitive function, and neuronal survival [15] [16].

Table 1: Lipid Species and Their Pathophysiological Roles in Specific Diseases

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Species | Alteration in Disease | Associated Pathophysiological Mechanisms | Relevant Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphingolipids | Ceramides (e.g., Cer, SM) | Increased | NLRP3 inflammasome activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance | MDD, CVD, T2DM [1] [15] |

| Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylcholines (PC), Phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) | Increased in DH | Membrane disruption, inflammatory signaling | Diabetes-Hyperuricemia, MDD [15] [19] |

| Glycerolipids | Triglycerides (TG) | Increased | Pro-inflammatory cytokine release, ectopic fat accumulation | CVD, T2DM, HUA [14] [19] |

| Sterol Lipids | Cholesterol, HDL, LDL | LDL increased/HDL decreased | Atherosclerotic plaque formation, impaired reverse cholesterol transport | CVD, AD, T2DM [14] [16] |

| Fatty Acyls | Free Fatty Acids (FFA) | Increased | Insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction | T2DM, Metabolic Syndrome [17] |

Abbreviations: MDD (Major Depressive Disorder), CVD (Cardiovascular Disease), T2DM (Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus), DH (Diabetes-Hyperuricemia), HUA (Hyperuricemia), AD (Alzheimer's Disease)

Lipidomic Methodologies for Investigating Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Analytical Platforms and Workflows

Comprehensive lipid analysis employs integrated chromatographic and mass spectrometric platforms to characterize lipid dysregulation at molecular levels. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has emerged as the gold standard for lipidomic profiling, enabling simultaneous quantification of hundreds of lipid species across multiple classes [1] [19]. The typical workflow encompasses sample preparation, chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric detection, data processing, and statistical analysis [1] [19].

Two complementary approaches dominate the field: untargeted lipidomics provides a comprehensive assessment of global lipid profiles without prior hypothesis, while targeted lipidomics enables precise quantification of predefined lipid panels with enhanced sensitivity and accuracy [1] [20]. The integration of these approaches facilitates both discovery and validation phases in biomarker development, as demonstrated in hyperuricemia research where untargeted analysis identified 50 differential metabolites, with 12 subsequently verified through targeted quantification [20].

Diagram 1: Integrated lipidomics workflow for pathophysiological investigation

Key Analytical Considerations

Robust lipidomic analysis requires careful optimization of multiple parameters throughout the analytical pipeline. Sample preparation must efficiently extract diverse lipid classes while minimizing degradation, with methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)/methanol systems providing comprehensive coverage [19]. Chromatographic separation typically employs reversed-phase (C18) columns with acetonitrile/water/isopropanol gradients to resolve lipid species by hydrophobicity [19].

Mass spectrometric detection leverages both high-resolution accurate mass instruments (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) for untargeted discovery and triple quadrupole platforms for targeted quantification using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [1] [20]. Data processing incorporates specialized bioinformatic tools (MS DIAL, Lipostar) for peak detection, alignment, and identification, though inconsistent results across platforms remain a challenge, with agreement rates as low as 14-36% [1]. Rigorous validation through standards, quality controls, and orthogonal methods is essential for reliable biological interpretation.

Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Comorbidity: A Paradigm of Integrated Lipid Pathophysiology

Clinical and Metabolic Interrelationships

The frequent co-occurrence of diabetes and hyperuricemia represents an instructive model for understanding how lipid dysregulation propagates across metabolic pathways. Clinical evidence demonstrates that approximately 81.6% of patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes exhibit combined dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia, creating a high-risk metabolic phenotype [17]. This convergence is mechanistically grounded in shared pathophysiological processes including insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation [17] [18].

The uric acid-to-HDL cholesterol ratio (UHR) quantitatively captures this metabolic intersection, with elevated UHR values significantly associated with abdominal aortic calcification in diabetic patients (OR: 1.43 per 1-unit increase in log2-UHR) [18]. Mediation analysis indicates that diabetes accounts for 7.5-14% of the association between UHR and vascular calcification, highlighting the partial independence of lipid-uric acid interactions from glycemic status [18]. These findings position UHR as a simple but informative composite biomarker reflecting integrated metabolic risk.

Lipidomic Signatures and Pathway Alterations

Comprehensive lipid profiling of patients with diabetes-hyperuricemia comorbidity reveals distinct molecular signatures that illuminate underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. UHPLC-MS/MS analysis identifies 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with 31 significantly altered species in diabetes-hyperuricemia compared to healthy controls [19]. The most prominent changes include upregulation of 13 triglyceride species, 10 phosphatidylethanolamines, and 7 phosphatidylcholines, along with downregulation of select phosphatidylinositols [19].

Pathway analysis of these alterations identifies glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) as the most significantly perturbed pathways in diabetes-hyperuricemia patients [19]. These pathway disturbances reflect fundamental disruptions in membrane biology, signaling transduction, and energy storage that jointly contribute to disease progression. The lipidomic profile further differentiates diabetes-hyperuricemia from diabetes alone, with 12 discriminatory lipids highlighting the specific metabolic impact of uric acid dysregulation on lipid homeostasis [19].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Lipid Alterations in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Comorbidity

| Analytical Method | Sample Size | Key Lipid Alterations | Pathway Enrichment | Statistical Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-MS/MS (Untargeted) | 17 DH, 17 DM, 17 HC | ↑ 13 TGs, ↑ 10 PEs, ↑ 7 PCs, ↓ 1 PI | Glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact: 0.199), Glycerolipid metabolism (impact: 0.014) | OPLS-DA: R2Y=0.909, Q2=0.840 (ESI+) | [19] |

| UPLC-TQ-MS (Targeted) | 20 HUA, 20 HC | 12 validated biomarkers including palmitic acid, lactic acid, valine | Glycerophospholipid metabolism, Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis | AUC > 0.9 for validated biomarkers | [20] |

| Clinical Biobank Analysis | 304 T2DM patients | Elevated UHR (UA/HDL-C ratio) strongly associated with dyslipidemia-hyperuricemia co-occurrence | Integrated purine and lipid metabolism | OR: 1.43 for AAC per 1-unit log2-UHR increase | [17] [18] |

Abbreviations: DH (Diabetes-Hyperuricemia), DM (Diabetes Mellitus), HC (Healthy Controls), HUA (Hyperuricemia), TGs (Triglycerides), PEs (Phosphatidylethanolamines), PCs (Phosphatidylcholines), PI (Phosphatidylinositol), UHR (Uric acid-to-HDL cholesterol Ratio), AAC (Abdominal Aortic Calcification)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipid Dysregulation Studies

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Function in Lipid Dysregulation Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Systems | UHPLC with C18 columns (e.g., Waters ACQUITY) | Separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to detection | Mobile phases: acetonitrile/water/isopropanol with ammonium formate [19] |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Q-TOF (SCIEX, Thermo), Triple Quadrupole (TQ-MS) | Untargeted discovery (Q-TOF) and targeted quantification (TQ-MS) | MRM mode essential for precise quantification of low-abundance species [20] |

| Lipid Extraction Reagents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Methanol | Efficient extraction of diverse lipid classes with minimal degradation | MTBE/methanol/water (10:3:2.5) provides comprehensive coverage [19] |

| Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled lipid analogs | Quantification normalization and quality control | Deuterated or 13C-labeled PC, PE, TG, Cer recommended [20] |

| Data Processing Software | MS DIAL, Lipostar, MetaboAnalyst | Peak detection, alignment, identification, and pathway analysis | Platform discrepancies necessitate cross-validation [1] |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary hepatocytes, adipocytes, neuronal cells | In vitro mechanistic studies of lipid metabolism | Enable genetic and pharmacological manipulation of lipid pathways [15] |

| 7-Methoxycoumarin-3-carboxylic Acid | 7-Methoxycoumarin-3-carboxylic Acid, CAS:20300-59-8, MF:C11H8O5, MW:220.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| NBD dodecanoic acid N-succinimidyl ester | NBD dodecanoic acid N-succinimidyl ester, MF:C22H29N5O7, MW:475.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Lipid dysregulation represents a unifying pathophysiological mechanism that transcends traditional disease boundaries, connecting metabolic, cardiovascular, neurological, and inflammatory disorders through shared molecular pathways. The diabetes-hyperuricemia model exemplifies how integrated lipidomic approaches can decode complex pathophysiological interactions, revealing specific lipid species and metabolic pathways that drive disease progression.

Future research directions should prioritize the translation of lipidomic discoveries into clinical applications, including validated biomarker panels for early risk stratification and personalized intervention. Advancements in artificial intelligence and machine learning (e.g., MS2Lipid with 97.4% subclass prediction accuracy) promise to enhance lipid annotation and biomarker discovery [1]. Simultaneously, standardization of pre-analytical protocols, analytical platforms, and data processing pipelines remains essential to overcome current reproducibility challenges [1].

The developing recognition of lipid-mediated immunometabolic cross-talk opens new therapeutic opportunities for modulating immune function through lipid-targeted interventions [16]. As our understanding of lipid dysregulation continues to evolve, multi-omics integration and systems biology approaches will be crucial for deciphering the complex networks linking lipid metabolism to pathophysiological processes across diverse disease contexts.

Cross-species validation serves as a critical bridge between basic research and clinical application in metabolic disease studies. In the interconnected fields of hyperuricemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), this approach enables researchers to decipher complex pathophysiology and evaluate therapeutic interventions through a coordinated pipeline of animal models and human validation studies. The convergence of lipidomics, gut microbiome analysis, and machine learning with traditional biochemical approaches has generated unprecedented opportunities for biomarker discovery and mechanistic elucidation. This whitepaper examines current methodologies, data integration frameworks, and experimental protocols that facilitate robust cross-species validation in hyperuricemia-diabetes research, providing drug development professionals with validated approaches for translational science.

The pathophysiological interconnection between hyperuricemia and diabetes is well-established, with epidemiological studies indicating that hyperuricemia increases the risk of T2DM by 1.6 to 2.5 times [21]. This relationship is bidirectional: insulin resistance contributes to elevated uric acid levels, while hyperuricemia exacerbates insulin resistance through mechanisms including chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction [21]. Within this complex metabolic cross-talk, lipidomic disturbances emerge as a central feature, with glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways significantly perturbed in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia [19].

Animal Models in Hyperuricemia-Diabetes Research

Model Selection Criteria

Animal models provide controlled systems for investigating hyperuricemia-diabetes pathophysiology and screening therapeutic candidates. An ideal model should recapitulate key aspects of human disease while permitting experimental manipulation impossible in human subjects. Selection criteria include genetic relevance to human pathophysiology, metabolic similarity, reproducibility, and practical considerations regarding cost and handling [22].

Table 1: Hyperuricemia Animal Models and Their Applications

| Model Type | Induction Method | Key Characteristics | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemically Induced Rodent | Uricase inhibitors (potassium oxonate) + purine-rich diet [22] | Rapid induction, reversible, mimics renal excretion impairment | Drug screening, acute metabolic studies [22] |

| Genetic Rodent Model | Urate oxidase gene knockout [23] | Spontaneous hyperuricemia, resembles human metabolism | Long-term pathophysiology, complication studies [23] |

| Poultry Models | High-purine diet (chickens, quails) [22] | Natural absence of uricase, human-like purine metabolism | Uric acid production and excretion studies [22] |

Rodents, particularly rats and mice, remain the most widely used animals due to their clear genetic background, strong reproductive capacity, and physiological similarity to humans [22]. A significant limitation in rodent models is the presence of uricase, which further breaks down uric acid into allantoin, differing from human metabolic characteristics. Researchers commonly address this through uricase inhibition or genetic modification [22]. Sex-based considerations are crucial in model selection, as female rodents exhibit protective effects against hyperuricemia likely due to estrogen influence, which lowers hepatic xanthine oxidase activity and modulates urate transporters [22]. Consequently, adult male rodents are typically preferred for modeling to ensure stability and reproducibility, though female or ovariectomized models are valuable for studying postmenopausal or age-related hyperuricemia [22].

Established Model Systems

Gene-edited models, particularly urate oxidase knockout mice, have emerged as valuable tools for studying spontaneous hyperuricemia and its natural progression. These models demonstrate sustained elevated serum uric acid levels without chemical induction, effectively mimicking the human metabolic state [23]. Recent research utilizing such models has revealed that persistent hyperuricemia promotes metabolic disturbances, including increased blood glucose, insulin resistance, and pancreatic β-cell damage following streptozotocin challenge [23].

Poultry animals, including chickens and quails, offer a distinct advantage due to their natural absence of uricase genes, resulting in purine metabolism that closely resembles humans [22]. These models rely on similar uric acid transporters (BCRP, MRP4, and GLUT9) for excretion, providing a physiologically relevant system for studying uric acid handling without requiring genetic or chemical manipulation [22].

Analytical Frameworks for Cross-Species Validation

Lipidomics Approaches

Lipidomics has revolutionized metabolic disease research by enabling comprehensive characterization of lipid profiles and their alterations in disease states. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying subtle metabolic disturbances that precede clinical manifestation of hyperuricemia-diabetes comorbidity.

Table 2: Lipidomics Methodologies in Hyperuricemia-Diabetes Research

| Methodology | Technical Approach | Applications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Lipidomics | UHPLC-MS/MS comprehensive profiling [19] | Discovery phase biomarker identification | Revealed 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in DH patients [19] |

| Targeted Lipidomics | Focused MS analysis of specific lipid classes [1] | Validation and quantification | Ceramides and phosphatidylcholines association with cardiovascular risk [1] |

| Pseudotargeted Approach | Combined untargeted and targeted strategies [1] | Enhanced coverage and quantification | Improved reproducibility in clinical validation [1] |

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has identified distinct lipidomic signatures in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia (DH) compared to those with diabetes alone or healthy controls [19]. Specifically, 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses have been characterized, with 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites pinpointed in DH patients [19]. These include 13 triglycerides (e.g., TG 16:0/18:1/18:2), 10 phosphatidylethanolamines (e.g., PE 18:0/20:4), and 7 phosphatidylcholines (e.g., PC 36:1) that were significantly upregulated, while one phosphatidylinositol was downregulated [19]. Pathway analysis has revealed enrichment in glycerophospholipid metabolism and glycerolipid metabolism as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [19].

Gut Microbiome Analysis

The gut microbiome represents a crucial interface between host metabolism and environmental influences, with emerging evidence establishing its significant role in hyperuricemia and diabetes pathophysiology. Microbial community analysis through 16S rRNA sequencing has demonstrated consistent alterations in gut microbiota composition in hyperuricemia and gout patients compared to healthy controls [24] [25].

Studies have observed a dramatic decreasing trend in microbial richness and diversity in hyperuricemic patients, characterized by reduced abundance of butyrate-producing genera including Faecalibacterium, Coprococcus, and Enterococcus [24]. Concurrently, opportunistic pathogens such as Proteobacteria and Fusobacterium are enriched in the hyperuricemia group [24]. These microbial disturbances appear to progress with disease severity, with gout patients exhibiting significantly reduced microbial diversity compared to asymptomatic hyperuricemic individuals, marked by decreased richness of Dialister, Ruminococcus, and Faecalibacterium genera [24] [25].

Machine learning algorithms applied to microbiome data have demonstrated remarkable diagnostic potential. Random Forest models achieved prediction accuracy of 82-96% for distinguishing healthy controls, hyperuricemia, and gout patients based on microbial features [25]. Metabolic function predictions from these analyses indicate that purine metabolism pathway alterations contribute most significantly to distinguishing gout from other groups [25].

Integration of Machine Learning in Metabolic Research

Advanced computational methods have become indispensable for handling the multidimensional datasets generated in cross-species validation studies. Machine learning algorithms, particularly tree-based models like Random Forest and eXtreme Gradient Boosting, have demonstrated superior performance in analyzing complex microbiome and lipidomic data [25]. These approaches consider changes in bacterial populations or lipid species within the context of other community members, rather than assessing relative abundance in isolation [25].

Interpretable machine learning frameworks, such as Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), facilitate identification of core features contributing to predictive models, enabling researchers to move beyond correlation to mechanistic insight [25]. For environmental risk prediction, models like Extreme Gradient Boosting have been successfully applied to identify key chemical exposures associated with hyperuricemia development, providing insights into modifiable risk factors [26].

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Species Investigation

Lipidomics Workflow

A standardized lipidomics protocol ensures reproducible and biologically meaningful results across species:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect biological samples (plasma/serum/tissues) following standardized procedures

- For plasma: Draw fasting blood samples, centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature, aliquot supernatant, and store at -80°C [19]

- For extraction: Thaw samples on ice, vortex, aliquot 100μL into 1.5mL centrifuge tube

- Add 200μL of 4°C water, mix, then add 240μL pre-cooled methanol

- Add 800μL methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), sonicate in low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes

- Incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes, centrifuge at 14,000g for 15 minutes at 10°C

- Collect upper organic phase, dry under nitrogen stream [19]

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Use Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1mm × 100mm, 1.7μm)

- Mobile phase A: 10mM ammonium formate acetonitrile solution in water

- Mobile phase B: 10mM ammonium formate acetonitrile isopropanol solution [19]

- Employ gradient elution with increasing organic phase

- Utilize both positive and negative ionization modes for comprehensive lipid coverage

- Include quality control samples (pooled samples) throughout sequence [19]

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Perform peak detection, alignment, and identification using specialized software (MS-DIAL, Lipostar)

- Apply multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, OPLS-DA) to identify group separations

- Conduct univariate analysis (Student's t-test, fold change) to determine significant alterations

- Execute pathway analysis using platforms such as MetaboAnalyst 5.0 [19]

Gut Microbiome Analysis Protocol

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect fresh stool samples, freeze immediately at -80°C

- Extract bacterial genomic DNA using commercial kits (e.g., Magen Hipure Soil DNA Kit)

- Quantify DNA using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [24]

16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Sequencing:

- Amplify V4 region using primer pair 515F (5'-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3')

- Incorporate adapter sequences and indexing barcodes for multiplexing

- Verify PCR products via agarose gel electrophoresis

- Purify and pool amplicons at equimolar ratios

- Sequence using Illumina MiSeq platform or similar [24] [25]

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform quality control, adapter trimming, and chimera removal using Trimmomatic and UCHIME

- Cluster sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity threshold using USEARCH

- Taxonomically classify sequences using SILVA database

- Conduct α-diversity (Shannon, Simpson indices) and β-diversity (PCoA, OPLS-DA) analyses

- Identify differentially abundant taxa using LEfSe or similar methods

- Apply machine learning algorithms for feature selection and classification [25]

Integrated Cross-Species Validation Framework

A proposed three-dimensional conceptual framework maps animal models according to pathogenic mechanism, modeling strategy, and translational goal [22]. This framework organizes models based on whether they primarily recapitulate excess urate production, impaired excretion, or inflammatory sequelae along the mechanistic axis [22]. Methodologically, models are classified as chemical induction, gene editing, environmental/exercise challenge, or microbiota modulation [22]. Finally, the translational axis aligns each model with its contribution to drug validation, target discovery, or biomarker development [22].

This integrated approach facilitates appropriate model selection for specific research questions and enhances translational predictability by highlighting complementary strengths across different systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Oxonate | Chemical induction of hyperuricemia [22] | Uricase inhibitor, reduces uric acid conversion to allantoin | Typically administered at 100-300mg/kg/day for 7-21 days [22] |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | β-cell ablation, diabetes induction [23] | Selective pancreatic β-cell toxicity, induces insulin deficiency | Multiple intraperitoneal injections at 40mg/kg for 5 consecutive days [23] |

| UHPLC-MS/MS System | Lipidomic profiling [19] | Comprehensive lipid separation, identification, and quantification | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column; electrospray ionization [19] |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Microbiome analysis [24] [25] | Amplification of variable regions for bacterial community profiling | 515F/806R targeting V4 region; Illumina adapter-modified [24] |

| Methyl tert-Butyl Ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction [19] | Liquid-liquid extraction of lipid molecules from biological samples | 800μL added to 240μL methanol + 100μL sample [19] |

| Ethyl Tetradecanoate-d27 | Ethyl Tetradecanoate-d27, CAS:1113009-11-2, MF:C16H32O2, MW:283.59 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| H(-Asn-Pro-Asn-Ala)2-OH | H(-Asn-Pro-Asn-Ala)2-OH, MF:C32H50N12O13, MW:810.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Cross-Talk

Diagram 1: Hyperuricemia-Diabetes Pathophysiological Cross-Talk. This diagram illustrates the key mechanistic interactions between hyperuricemia, insulin resistance, lipid disturbances, gut dysbiosis, and inflammation. SCFA: short-chain fatty acids; TG: triglycerides; PC: phosphatidylcholines; PE: phosphatidylethanolamines.

The pathophysiological relationship between hyperuricemia and diabetes involves complex, bidirectional interactions. Elevated uric acid promotes insulin resistance through oxidative stress mechanisms, while also activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, driving chronic inflammation [22] [21]. Concurrently, hyperuricemia induces lipid disturbances characterized by elevated triglycerides, phosphatidylcholines, and phosphatidylethanolamines [19]. Gut dysbiosis, marked by reduced SCFA-producing bacteria and enrichment of opportunistic pathogens, contributes to both hyperuricemia and inflammation [24]. Insulin resistance further exacerbates hyperuricemia by impairing renal uric acid excretion, completing a vicious cycle of metabolic dysfunction [21].

Cross-species validation represents a powerful paradigm for advancing hyperuricemia-diabetes research, integrating complementary data from controlled animal models and human clinical studies. The convergence of lipidomics, gut microbiome analysis, and machine learning provides multidimensional insights into disease pathophysiology beyond traditional biochemical parameters. Standardized experimental protocols for lipidomic and microbiome analyses ensure reproducibility across research platforms, while interpretable machine learning frameworks extract biologically meaningful patterns from complex datasets. As research in this field evolves, the continued refinement of cross-species validation approaches will accelerate biomarker discovery and therapeutic development for these interconnected metabolic disorders.

Advanced Lipidomics Technologies: From UHPLC-MS/MS Workflows to Diagnostic Applications

Lipidomics, defined as the large-scale study of pathways and networks of cellular lipids in biological systems, has emerged as a crucial discipline for understanding metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) [27] [28]. Lipids are diverse biological molecules that play essential roles in cell structure, energy storage, and signaling processes, with their dysregulation increasingly linked to disease pathogenesis [29]. The structural diversity of lipids is immense—the LIPID MAPS Structure Database has enrolled over 44,000 unique lipid structures distributed across eight main categories, creating significant analytical challenges [29]. In the context of diabetes and hyperuricemia, lipidomics offers unprecedented opportunities to discover novel biomarkers and elucidate pathological mechanisms, as lipid abnormalities are frequently associated with both conditions [6] [12] [30]. Advances in mass spectrometry (MS) platforms, particularly when coupled with ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC), have enabled researchers to comprehensively characterize lipid metabolic disruptions that precede and accompany these metabolic disorders [6] [29].

UHPLC-MS/MS Technology Platform

Fundamental Principles and Technical Advantages

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) represents the analytical cornerstone of modern lipidomics due to its superior separation efficiency, sensitivity, and specificity compared to conventional techniques [6] [31] [29]. The UHPLC component separates complex lipid mixtures using specialized columns with sub-2μm particles under high pressure, providing exceptional resolution of lipid species based on their hydrophobicity prior to mass analysis [6] [31]. The tandem mass spectrometer then detects and identifies separated lipids with high mass accuracy, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis [31] [32]. This platform's technical advantages include its ability to resolve isobaric and isomeric lipids, detect low-abundance lipid species, and provide structural information through fragmentation patterns [29]. These capabilities are particularly valuable in diabetes and hyperuricemia research, where subtle alterations in lipid metabolism may signal early disease stages or progression [6] [12].

Key System Components and Configurations

A typical UHPLC-MS/MS system for lipidomics comprises several integrated components optimized for lipid analysis. The UHPLC subsystem typically utilizes reversed-phase C18 columns (e.g., Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18, 1.7μm) for separation based on fatty acyl chain properties [6] [31]. Mobile phases commonly consist of acetonitrile/water and isopropanol/acetonitrile mixtures with modifiers such as ammonium formate or acetic acid to enhance ionization efficiency [6] [31]. The mass spectrometry component may employ triple quadrupole, time-of-flight (TOF), or Orbitrap mass analyzers, each offering distinct advantages for different lipidomics applications [27] [29]. Triple quadrupole instruments operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode provide exceptional sensitivity for targeted quantification, while high-resolution instruments like Orbitrap and Q-TOF enable comprehensive lipid profiling in untargeted approaches [27] [32] [29]. Ionization is typically achieved via electrospray ionization (ESI) sources, which efficiently generate lipid ions for mass analysis [31].

Table 1: Key UHPLC-MS/MS Components for Lipidomics

| System Component | Typical Specifications | Lipidomics Application |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1×100mm, 1.7μm) | Separation of complex lipid mixtures |

| Mobile Phase | Acetonitrile/water and acetonitrile/isopropanol with 10mM ammonium formate | Optimal lipid separation and ionization |

| Mass Analyzer | Triple quadrupole, Q-TOF, or Orbitrap | Targeted quantification or untargeted profiling |

| Ionization Source | Electrospray ionization (ESI) | Efficient generation of lipid ions |

| Data Acquisition | MRM for targeted; Full scan/data-dependent MS/MS for untargeted | Lipid identification and quantification |

Targeted vs. Untargeted Lipidomics Strategies

Untargeted Lipidomics: Comprehensive Biomarker Discovery

Untargeted lipidomics is a comprehensive, unbiased approach aimed at identifying and quantifying as many lipid species as possible within a biological sample without predefining targets [27]. This exploratory technique is ideal for hypothesis generation and discovery of novel lipid biomarkers, making it particularly valuable for initial investigations into the lipidomic alterations associated with diabetes and hyperuricemia [27] [29]. The methodology typically involves high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) platforms such as Q-TOF, Orbitrap, or Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance MS, which provide the mass accuracy and resolution needed for unknown lipid identification [27] [29]. Sample preparation for untargeted lipidomics requires meticulous extraction using solvents like methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) or chloroform-methanol to recover a broad range of lipid classes while removing proteins and other interferents [6] [27]. Chromatographic separation, typically using UHPLC, reduces ion suppression and enables separation of isomeric lipids before mass analysis [32] [29]. Data processing involves sophisticated bioinformatics tools for peak detection, alignment, and lipid identification using databases such as LIPID MAPS and HMDB [27] [29].

The applications of untargeted lipidomics in diabetes and hyperuricemia research include comprehensive biomarker discovery, disease mechanism elucidation, and novel lipid species identification [27]. For example, in a study comparing patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), diabetes mellitus alone (DM), and healthy controls (NGT), untargeted lipidomics revealed 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in the DH group compared to controls [6]. These included upregulated triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and phosphatidylcholines (PCs), highlighting the profound lipid dysregulation in this patient population [6]. Similarly, another study on hyperuricemia and gout patients identified significant alterations in glycerophospholipids, with the most pronounced dysregulation found in early-onset patients [12].

Targeted Lipidomics: Hypothesis-Driven Validation

Targeted lipidomics represents a focused, hypothesis-driven approach that quantifies specific, predefined lipid species with high precision and accuracy [27]. This method is ideal for validating findings from untargeted studies, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring, where precise quantification of specific lipid biomarkers is required [27] [32]. The methodology employs triple quadrupole mass spectrometers operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, which monitors specific precursor-product ion transitions for each target lipid with exceptional sensitivity and selectivity [27] [32]. Sample preparation incorporates stable isotope-labeled internal standards added prior to extraction to correct for variations in extraction efficiency, ionization suppression, and instrument performance [27] [12]. Chromatographic conditions are optimized for the specific lipid panel of interest, often providing faster analysis times than untargeted approaches [32]. Data processing is more straightforward than in untargeted lipidomics, with automated integration and quantification relative to internal standards [27] [32].

In diabetes and hyperuricemia research, targeted lipidomics enables accurate quantification of candidate biomarkers in large patient cohorts, facilitating clinical validation and potential translation to diagnostic applications [27] [12]. For instance, in a study of hyperuricemia and gout patients, targeted lipidomic analysis semi-quantified 608 lipids in plasma, revealing significant dysregulation of phosphatidylethanolamines and lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogens/plasmanyls [12]. This approach also demonstrated the corrective effect of urate-lowering treatment (ULT) on lipid imbalances, particularly in early-onset patients [12]. Another cross-platform comparison study demonstrated that targeted approaches could quantify hundreds of lipids across multiple classes with high precision (median CV < 5%) and strong correlation with untargeted methods (median r = 0.71) [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Approaches

| Characteristic | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Comprehensive biomarker discovery, novel lipid identification | Hypothesis testing, precise quantification of predefined lipids |

| Analytical Approach | Unbiased, global profiling | Focused analysis of specific lipids |

| MS Platform | High-resolution MS (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) | Triple quadrupole MS with MRM |

| Data Complexity | High, requires advanced bioinformatics | Manageable, streamlined processing |