MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA: A Comprehensive Guide to Binding Free Energy Calculations in Drug Discovery

This article provides a thorough exploration of Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA) methods for estimating binding free energies in structure-based drug design.

MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA: A Comprehensive Guide to Binding Free Energy Calculations in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA) methods for estimating binding free energies in structure-based drug design. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational theory, practical methodologies, critical optimization parameters, and comparative performance against other computational techniques. The content synthesizes recent scientific literature to offer actionable insights for applying these end-point methods to virtual screening, lead optimization, and biomolecular recognition studies, while acknowledging current limitations and future directions in the field.

Theoretical Foundations of End-Point Free Energy Methods

Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) are end-point free energy calculation methods that have gained significant popularity in structure-based drug design. These approaches occupy a crucial middle ground between computationally inexpensive but approximate docking scores and highly accurate but resource-intensive alchemical perturbation methods. First developed by Kollman et al. in the late 1990s, these methods enjoy widespread application with approximately 100-200 publications annually in recent years [1].

The fundamental goal of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA is to calculate the binding free energy (ΔGbind) for the receptor-ligand binding reaction R + L → RL. This is achieved by estimating the difference in free energies between the complex and the isolated receptor and ligand in solution: ΔGbind = Gcomplex - Greceptor - Gligand [1]. The free energy of each species is calculated using the following formulation:

G = EMM + Gsolv - TS

Where EMM represents the molecular mechanics energy in vacuum (including bonded, electrostatic, and van der Waals interactions), Gsolv is the solvation free energy, and TS represents the entropy term [1]. The solvation free energy is further decomposed into polar (Gpol) and non-polar (Gnp) components. The key distinction between MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA lies in how they calculate the polar solvation term: MM/PBSA employs the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, while MM/GBSA uses the Generalized Born approximation [2].

Table 1: Energy Components in MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Calculations

| Energy Component | Description | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanics (EMM) | Gas-phase interaction energy | Force field calculations |

| Electrostatic (Eele) | Coulombic interactions | Molecular mechanics |

| van der Waals (EvdW) | Dispersion and repulsion forces | Molecular mechanics |

| Polar Solvation (Gpol) | Electrostatic contribution to solvation | PB or GB equation |

| Non-polar Solvation (Gnp) | Non-electrostatic solvation contribution | Solvent accessible surface area |

| Entropy (-TS) | Conformational entropy change | Normal mode or quasi-harmonic analysis |

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Accuracy

Multiple large-scale studies have systematically evaluated the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA for binding affinity prediction and pose selection. A comprehensive assessment on 98 protein-ligand complexes revealed that MM/GBSA significantly outperformed MM/PBSA in identifying correct binding conformations, with success rates of 69.4% versus 45.5%, respectively [3]. Both methods demonstrated superior performance compared to standard docking scoring functions.

In predicting binding affinities, MM/GBSA with an internal dielectric constant of 2.0 achieved a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.66 with experimental data, outperforming MM/PBSA (0.49) and most docking scoring functions [3]. A separate study on 59 ligands across six different proteins found that MM/PBSA performed better in calculating absolute binding free energies, while MM/GBSA provided excellent relative rankings of inhibitors, making it particularly valuable for lead optimization in drug design [4].

More recent benchmarks incorporating both soluble and membrane proteins have demonstrated that MM/PB(GB)SA can achieve comparable accuracy to Free Energy Perturbation in many systems, while requiring substantially less computational resources [5]. The performance varies significantly based on system characteristics, with soluble proteins generally showing better agreement with experimental data than membrane-bound targets.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Free Energy Calculation Methods

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Scoring | Low | Moderate | High-throughput virtual screening |

| MM/GBSA | Medium | Good | Pose selection, lead optimization |

| MM/PBSA | Medium-High | Good | Absolute binding energy estimation |

| Free Energy Perturbation | Very High | Excellent | Lead optimization with high precision |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

System Preparation and Parameterization

The initial step involves preparing the protein-ligand complex structure. Begin by obtaining the PDB file and determining appropriate protonation states for ionizable residues using tools like the H++ webserver, which automatically assigns protonation states based on the specified pH environment [6]. For the ligand, partial atomic charges can be derived using various methods, with AM1-BCC charges providing a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, though RESP charges derived from quantum mechanical calculations may offer improved accuracy for certain systems [3] [5].

Generate topology and coordinate files using molecular mechanics programs. For AMBER-compatible workflows, the tleap module can be employed with appropriate force fields (e.g., ff14SB for proteins, GAFF for ligands). It is critical to set the PBRadii parameter consistently across all topology files, typically using the mbondi2 set for compatibility with GB models [6].

Molecular Dynamics Sampling

Explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations are recommended to generate conformational ensembles. After system setup, perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes, followed by gradual heating to the target temperature (typically 300K) and equilibration under constant pressure conditions. Production simulations should be sufficiently long to ensure adequate sampling; studies indicate that simulation length between 400-4800 ps can be sufficient, with longer simulations not always providing improved predictions [4].

For the single-trajectory approach (most common), simulate only the protein-ligand complex. The snapshots for MM/PBSA analysis are typically extracted at regular intervals from the production trajectory, with frames from the equilibration phase discarded. To reduce correlation between frames and computational expense, snapshots can be saved every 100-1000 ps, or a stride can be applied during post-processing [6].

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Calculation

The binding free energy calculation decomposes into three major components. The gas-phase molecular mechanics energy (ΔEMM) includes the internal energy (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and nonbonded interactions (electrostatic and van der Waals) between the receptor and ligand [2].

The solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) is calculated as the sum of polar (ΔGpol) and non-polar (ΔGnp) contributions. For MM/PBSA, the Poisson-Boltzmann equation solves for the electrostatic potential, while MM/GBSA employs the Generalized Born approximation as a faster alternative [2]. The non-polar component is typically estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area using the relation ΔGnp = γ × SASA + β [1].

The conformational entropy change (-TΔS) is often estimated using normal mode analysis, but this calculation is computationally demanding and may be omitted in high-throughput applications, despite potential accuracy costs [1] [7].

Key Parameters and Optimization Strategies

Dielectric Constants and GB Models

The solute dielectric constant significantly impacts the predicted binding affinities. Studies systematically testing values of 1, 2, and 4 have demonstrated that the optimal setting depends on the binding interface characteristics, with ε = 2 often providing the best balance for protein-ligand complexes [4]. The exterior dielectric is typically set to 80 for aqueous solutions, while membrane protein systems may require adjustment of the membrane dielectric constant [5].

For MM/GBSA calculations, the choice of GB model substantially influences results. The GB model developed by Onufriev and Case has demonstrated superior performance in ranking binding affinities compared to alternatives [4]. When using the mbondi2 atomic radii set, compatible GB models include igb=2 and igb=5 in AMBER implementations [6].

Entropy Considerations and Sampling

The entropic contribution to binding remains one of the most challenging aspects of MM/PBSA calculations. While normal mode analysis provides the most theoretically rigorous approach, it requires substantial computational resources and extensive sampling to achieve stable predictions [4]. In virtual screening applications where relative ranking is prioritized over absolute accuracy, the entropy term is often omitted to enhance throughput, though this simplification can be problematic for entropy-driven binding processes [7] [5].

Single-trajectory versus separate-trajectory approaches present an important methodological consideration. The single-trajectory approach (1A-MM/PBSA), which uses only the complex simulation and extracts receptor and ligand configurations, offers improved precision and computational efficiency but ignores conformational changes upon binding [1]. The three-trajectory approach (3A-MM/PBSA), with separate simulations for complex, receptor, and ligand, better captures binding-induced reorganization but exhibits significantly larger statistical uncertainty [1].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Tools and Parameters for MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Calculations

| Tool/Parameter | Function | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| MD Engine | Generates conformational trajectories | AMBER, GROMACS, OpenMM |

| Continuum Solvation | Calculates polar solvation energy | Poisson-Boltzmann vs. Generalized Born |

| MMPBSA.py | Automated MM/PBSA analysis | Part of AMBER Tools |

| gmx_MMPBSA | MM/PBSA for GROMACS users | Integration with GROMACS workflows |

| Ligand Charge Methods | Partial charge assignment | AM1-BCC for efficiency, RESP for accuracy |

| Internal Dielectric | Solute dielectric constant | 1-4 (system-dependent optimization required) |

| Force Fields | Molecular mechanics parameters | ff14SB (proteins), GAFF (ligands) |

| Solvent Model | Implicit solvation | PBSA, GBSA (Onufriev-Case model) |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Outlook

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA have found diverse applications across the drug discovery pipeline. In virtual screening, these methods serve as powerful rescoring tools to improve the identification of true active compounds from docking hits [7]. For binding pose prediction, MM/GBSA has demonstrated exceptional performance in identifying correct binding modes, achieving success rates exceeding those of standard docking scoring functions [3]. In lead optimization, the methods provide insights into structure-activity relationships by decomposing binding energies into residue-specific contributions, guiding medicinal chemistry efforts [7].

Recent methodological developments continue to enhance the applicability and accuracy of these approaches. Incorporation of halogen bonding parameters improves treatment of this important molecular interaction [5]. The development of interaction entropy approaches addresses limitations in traditional entropy calculations [5]. High-throughput implementations enable broader application in virtual screening, while specialized extensions facilitate studies on membrane protein targets like GPCRs [5] [2].

While MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA present powerful tools for binding affinity prediction, their performance remains system-dependent, requiring careful parameterization and validation against experimental data. As computational resources expand and methodologies refine, these end-point methods continue to bridge the critical gap between rapid docking and exhaustive free energy calculations, maintaining their essential role in the modern drug discovery toolkit.

Core Theoretical Framework and Thermodynamic Cycle

Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) are computational methods that provide an efficient intermediate approach for estimating binding free energies (ΔGbind) in molecular recognition processes, particularly in structure-based drug design [1]. These end-point methods are positioned between fast but less accurate empirical scoring functions and computationally intensive but highly accurate alchemical perturbation methods, offering a balance of reasonable accuracy and computational feasibility [1] [2]. The fundamental goal of these methods is to calculate the binding free energy for the receptor-ligand association process: R + L → RL, where R denotes the receptor (typically a protein) and L represents the ligand [1].

Since their development by Kollman et al. in the late 1990s, MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA have gained substantial popularity, with hundreds of publications annually applying these methods to various challenges including protein-ligand interactions, protein design, protein-protein interactions, conformer stability, and virtual screening rescoring [1] [2]. The modular nature of these methods and their independence from training sets make them particularly attractive for research applications where experimental binding data may be limited [1].

Core Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Thermodynamic Cycle

The theoretical foundation of MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA is built upon a thermodynamic cycle that separates the binding process into gas phase and solvation components. This approach allows for the decomposition of the binding free energy into computationally tractable terms. The binding free energy in solution is calculated as the difference between the free energy of the complex and the separated receptor and ligand [1] [5]:

ΔGbind = Gcomplex - Greceptor - Gligand

Each term in this equation represents the total free energy of the respective species, which is estimated using the relationship [1] [2]:

G = EMM + Gsolv - TS

Where:

- EMM represents the molecular mechanics energy in vacuum

- Gsolv denotes the solvation free energy

- -TS is the entropic contribution at absolute temperature T

Table 1: Components of the MM-PBSA/GBSA Binding Free Energy Calculation

| Component | Description | Subcomponents |

|---|---|---|

| EMM | Molecular mechanics energy in vacuum | Ebonded + Eelectrostatic + EvdW |

| Ebonded | Covalent bonding energy | Bond, angle, and dihedral energies |

| Eelectrostatic | Electrostatic interactions | Coulomb's law calculations |

| EvdW | van der Waals interactions | Lennard-Jones potential |

| Gsolv | Solvation free energy | Gpolar + Gnon-polar |

| Gpolar | Polar solvation contribution | PB or GB equation solutions |

| Gnon-polar | Non-polar solvation contribution | Linear function of SASA |

| -TS | Entropic contribution | Conformational entropy |

Molecular Mechanics Energy (EMM)

The molecular mechanics energy term (EMM) captures the gas-phase interaction energy between the receptor and ligand using classical force field parameters. This component is further decomposed into bonded (Ecovalent), electrostatic (Eelectrostatic), and van der Waals (EvdW) contributions [2]:

EMM = Ecovalent + Eelectrostatic + EvdW

The covalent term includes energy contributions from bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional rotations. The non-bonded components (electrostatic and van der Waals) are particularly important as they capture the essential intermolecular interactions between the receptor and ligand. In the single-trajectory approach, which is commonly used for improved precision, the bonded terms typically cancel out in the final binding free energy calculation [1].

Solvation Free Energy (Gsolv)

The solvation free energy term accounts for the transfer of the molecules from vacuum to aqueous solution and is separated into polar (Gpolar) and non-polar (Gnon-polar) components [1] [2]:

Gsolv = Gpolar + Gnon-polar

The polar solvation term is computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation in MM-PBSA or approximated using the Generalized Born (GB) model in MM-GBSA. The PB equation provides a more rigorous treatment of electrostatic interactions in dielectric environments but at greater computational cost, while the GB model offers a faster approximation suitable for high-throughput applications [2].

The non-polar solvation term is typically estimated using a linear relationship with the solvent accessible surface area (SASA): Gnon-polar = γ × SASA + β, where γ and β are empirically derived constants [1].

Entropic Contribution (-TS)

The entropic term represents the change in conformational entropy upon binding and is typically the most computationally expensive component to calculate. This term is often estimated using normal mode analysis (NMA) of vibrational frequencies, though this approach requires significant computational resources [1] [8]. Due to the high computational cost and associated large errors, the entropic contribution is sometimes neglected in screening applications, particularly when comparing structurally similar ligands where the entropy change is expected to be similar across the series [8] [5].

Recent research has focused on developing more efficient entropy estimation methods. The interaction entropy approach and formulaic entropy methods based on SASA and rotatable bond counts have shown promise as computationally efficient alternatives to NMA [8] [9]. These approaches can provide reasonable entropy estimates without the excessive computational burden of traditional methods.

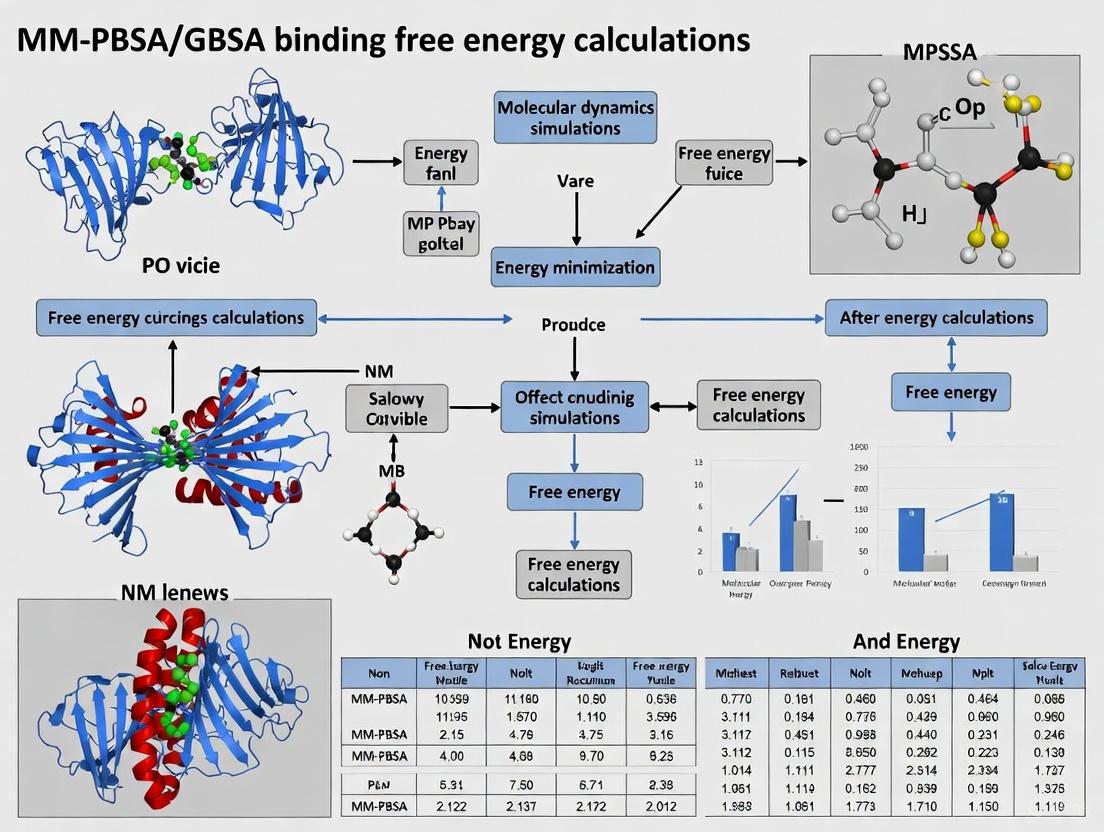

Diagram 1: MM-PBSA/GBSA Calculation Workflow - This flowchart illustrates the sequential steps involved in binding free energy calculations, highlighting key decision points throughout the process.

Methodological Approaches and Protocols

Trajectory Sampling Strategies

MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations can employ different trajectory approaches for ensemble averaging, each with distinct advantages and limitations [1]:

Single-Trajectory Approach (1A-MM/PBSA): This method uses only the complex simulation to generate ensembles for the free receptor and ligand by removing the appropriate atoms. It offers better precision and requires fewer computational resources but ignores structural changes in the receptor and ligand upon binding [1].

Multiple-Trajectory Approach (3A-MM/PBSA): This approach employs three separate simulations for the complex, free receptor, and free ligand. While theoretically more rigorous, it typically results in larger standard errors (4-5 times higher in some studies) and may yield less accurate results due to insufficient sampling [1].

Comparative studies have shown that the single-trajectory approach often provides more accurate results despite its simplifications, particularly when the binding does not involve substantial conformational changes [1] [8]. The two-trajectory approach (2A), which includes sampling of both the complex and free ligand, has been suggested as a compromise that captures ligand reorganization energy while maintaining reasonable computational requirements [1] [10].

Solvation Models and Parameterization

The selection of solvation models and parameters significantly impacts the accuracy of MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations. Key considerations include:

Dielectric Constants: The interior dielectric constant (εin) represents the protein environment's dielectric properties. Studies have shown that optimal values are system-dependent, with low dielectric constants (εin = 1-2) often appropriate for hydrophobic binding pockets and higher values (εin = 4) needed for more polar interfaces [8] [11].

GB Models: Various Generalized Born implementations offer different trade-offs between accuracy and speed. The GB model developed by Onufriev et al. has demonstrated good performance for protein-protein binding affinity predictions [11].

Force Field Selection: Studies comparing AMBER force fields found that while the ff03 force field performed best, predictions across different force fields were generally comparable, suggesting MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations are not overly sensitive to force field selection [8].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for MM-PBSA/GBSA Calculations

| Step | Protocol Description | Key Parameters | Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Preparation | Generate receptor, ligand, and complex structures; assign partial charges | Force field selection (FF14SB, GAFF2); charge method (AM1-BCC, RESP) | AmberTools, Schrödinger Suite, AutoDockTools [10] [12] |

| Conformational Sampling | Generate ensemble of structures using MD simulation or minimization | Simulation length; implicit/explicit solvent; sampling frequency | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD [1] [2] |

| Energy Calculation | Calculate molecular mechanics energy components | Interior dielectric constant; force field parameters | MMPBSA.py, g_mmpbsa, Schrodinger [10] [5] |

| Solvation Energy | Compute polar and non-polar solvation contributions | GB model; SASA method; dielectric constants | APBS, MMPBSA.py [10] [2] |

| Entropy Estimation | Calculate conformational entropy change | Entropy method (NMA, interaction entropy, formulaic) | Normal mode analysis, interaction entropy approach [8] [9] |

Specialized Applications and Extensions

Membrane Protein Systems

Traditional MM-PBSA/GBSA methods face challenges when applied to membrane proteins due to the heterogeneous dielectric environment of lipid bilayers. Recent developments have addressed these limitations through specialized implementations that account for the membrane environment [13] [5]. Key advancements include:

- Automated determination of membrane thickness and location

- Consistent treatment of continuum dielectric in electrostatic energy calculations

- Specialized GB models designed for membrane systems (GBMEM) [13]

These improvements have demonstrated enhanced performance for membrane protein-ligand systems such as the P2Y12 receptor, providing more reliable binding free energy estimates for this important class of drug targets [13].

Entropy Calculation Improvements

The accurate and efficient calculation of entropic contributions remains an active area of research. Recent developments include:

Interaction Entropy Approach: This method estimates entropy directly from MD simulations without additional computational cost and has shown comparable or better performance than traditional NMA, particularly at low dielectric constants [8].

Formulaic Entropy: This recently developed approach computes entropy from a single structure based on SASA and rotatable bond counts, systematically improving MM-PBSA/GBSA performance without significant computational overhead [9].

Truncated NMA: Using truncated structures for normal mode analysis reduces computational cost while maintaining reasonable accuracy, particularly when applied to MD trajectories with higher dielectric constants [8].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MM-PBSA/GBSA Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER/AmberTools | MD simulations & MM-PBSA analysis | Comprehensive suite for simulation and end-point free energy calculations [10] [13] |

| MMPBSA.py | Automated MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations | Streamlined workflow implementation within AmberTools [10] |

| Schrödinger Suite | Molecular modeling & MM-GBSA | Commercial platform with integrated binding free energy capabilities [10] [14] |

| g_mmpbsa | MM-PBSA/GBSA with GROMACS | Integration with GROMACS MD simulation package [5] |

| APBS | Poisson-Boltzmann equation solver | Accurate calculation of polar solvation energies [2] |

| FF14SB/GAFF2 | Protein and small molecule force fields | Standard parameterization for biomolecular systems [10] [5] |

| AM1-BCC/RESP | Partial charge assignment methods | Charge derivation for ligands and modified residues [10] [5] |

Diagram 2: Component Integration in MM-PBSA/GBSA - This diagram illustrates the relationships between different computational components and resources in binding free energy calculations, highlighting how various tools and methods integrate within the overall framework.

Performance Benchmarking and Validation

Accuracy Across Protein Systems

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA across diverse protein systems. Key findings include:

Soluble Proteins: For six soluble protein systems (CDK2, TYK2, P38, Mcl1, Jnk1, and thrombin), MM-PBSA/GBSA demonstrated competitive performance compared to more computationally intensive free energy perturbation (FEP) methods, while significantly outperforming standard docking scoring functions [5].

Membrane Proteins: In evaluations with three membrane protein systems (mPGES, GPBAR, and OX1), the performance was more variable and highly dependent on parameter selection, particularly the membrane dielectric constant [5].

Protein-Protein Interactions: For 46 protein-protein complexes, MM-GBSA with the ff02 force field and GB model by Onufriev et al. using εin = 1 achieved the best correlation with experimental data (rp = -0.647), outperforming MM-PBSA and several empirical scoring functions [11].

Practical Considerations for Applications

When applying MM-PBSA/GBSA methods in research and drug development, several practical considerations emerge:

Virtual Screening: The methods show utility in re-ranking docking poses and improving virtual screening enrichment, though computational cost may limit large-scale application [1] [14].

Lead Optimization: For series of structurally similar compounds, MM-PBSA/GBSA can provide valuable trends in binding affinity to guide medicinal chemistry efforts, with the single-trajectory approach offering the best balance of precision and computational efficiency [1].

System-Specific Optimization: Parameters such as GB models, interior dielectric constants, and entropy treatment should be optimized for specific systems to maximize accuracy [5] [11].

While MM-PBSA/GBSA methods contain approximations that limit their absolute accuracy, their ability to reproduce experimental trends and rationalize structural data makes them valuable tools in the computational drug discovery pipeline, particularly when used with appropriate validation and understanding of their limitations.

Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) are established computational methods for estimating binding free energies in biomolecular systems, playing a crucial role in modern drug discovery and design [15] [16]. These methods decompose the overall binding free energy into constituent components, providing insights into the physical drivers of molecular recognition. The accuracy and predictive power of these calculations hinge on the proper treatment of three key energy components: the molecular mechanics (MM) energy from the force field, the solvation free energy, and the entropic contribution [9] [17]. This application note details the theoretical foundation, calculation protocols, and practical implementation for each of these components, framed within ongoing research efforts to enhance the reliability of binding free energy calculations.

The binding free energy (ΔGbind) for a receptor (R) ligand (L) complex is calculated as: ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Greceptor + Gligand) where each term (G) represents the total free energy of the respective species in solvent [16]. The total free energy for any molecule is computed as: G = EMM + Gsolv - TS Here, EMM is the molecular mechanics energy in vacuum, Gsolv is the solvation free energy, and TS represents the entropic contribution at temperature T [18].

Theoretical Background and Energy Decomposition

The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Framework

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA are end-state methods that compute binding free energies from ensembles of structures, typically generated by Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [18]. They offer a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy, sitting between faster but less accurate docking scores and more rigorous but computationally expensive alchemical methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [19]. The fundamental distinction between MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA lies in how the polar component of solvation is treated: MM/PBSA uses the more accurate but computationally intensive Poisson-Boltzmann equation, while MM/GBSA approximates it with the faster Generalized Born model [18].

Thermodynamic Cycle

The calculation relies on a thermodynamic cycle that connects the solvated and vacuum states of the receptor, ligand, and complex, avoiding direct simulation of the binding process in explicit solvent.

Diagram 1: Thermodynamic cycle for MM/P(G)BSA binding free energy calculation. The experimental binding free energy in solution (ΔGsolv_bind) is obtained via the horizontal vacuum pathway [18].

Key Energy Components

Molecular Mechanics (MM) Energy

The molecular mechanics energy (EMM) represents the gas-phase potential energy calculated using a classical force field. It is decomposed into bonded and non-bonded interactions:

EMM = Ebonded + Enon-bonded

The bonded term includes energy from bond stretching (Ebond), angle bending (Eangle), and dihedral torsions (Edihedral). The non-bonded term encompasses van der Waals interactions (EvdW) modeled by the Lennard-Jones potential, and electrostatic interactions (Eele) calculated using Coulomb's law [18]. In many MM/PBSA implementations, internal strain energy is often neglected assuming similar bonding in bound and unbound states.

Solvation Free Energy

The solvation free energy (Gsolv) quantifies the energy change associated with transferring a molecule from vacuum to solvent. It is partitioned into polar and non-polar components:

Gsolv = Gpolar + Gnon-polar

Polar Solvation (Gpolar): This is calculated using the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation in MM/PBSA or approximated by the Generalized Born (GB) model in MM/GBSA. These models treat the solute as a low-dielectric cavity embedded in a high-dielectric continuum representing the solvent [15] [18]. The choice of internal dielectric constant is critical, with values >1.0 (often between 2-4) sometimes necessary to account for electronic polarization and preserve native structures in MD simulations [15].

Non-Polar Solvation (Gnon-polar): This term accounts for the hydrophobic effect and cavity formation. It is typically modeled as being proportional to the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA): Gnon-polar = γ × SASA + b, where γ is the surface tension parameter and b is a constant [15].

Entropic Contribution

The entropic contribution (-TS) is a critical but often computationally challenging component. Entropy represents the change in conformational freedom upon binding and is frequently a major determinant of binding affinity [17] [18].

Translational and Rotational Entropy: These are calculated using standard formulas from statistical mechanics for a rigid rotor.

Vibrational Entropy: This is the most significant and difficult component to compute. Two primary methods are used:

- Normal Mode Analysis (NMA): Involves calculating vibrational frequencies at local energy minima. It is computationally expensive due to the need for matrix diagonalization, scaling approximately as (3N)3 for a system with N atoms [18].

- Quasi-Harmonic Analysis (QHA): Approximates entropy from the covariance matrix of atomic fluctuations during MD simulations. It requires extensive sampling for convergence [18].

A major advancement is the development of formulaic entropy approaches, which compute entropy from a single structure based on polar/non-polar solvent-accessible surface areas and rotatable bond counts. This method integrates into MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA without additional computational cost, systematically improving performance [9].

Table 1: Key Energy Components in MM/P(G)BSA Calculations

| Component | Description | Calculation Methods | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanics (EMM) | Gas-phase potential energy from force field | Force field evaluation (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) | Force constants, atomic charges, Lennard-Jones parameters |

| Polar Solvation (Gpolar) | Electrostatic solute-solvent interactions | Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) or Generalized Born (GB) | Internal/external dielectric constants, atomic radii |

| Non-Polar Solvation (Gnon-polar) | Hydrophobic effect, cavity formation | Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) proportionality | Surface tension coefficient (γ) |

| Entropy (-TS) | Loss of conformational freedom upon binding | Normal Mode Analysis, Quasi-Harmonic Analysis, or Formulaic Entropy | - |

Detailed Protocol for MM/PBSA Calculation

This protocol outlines the steps for performing an MM/PBSA calculation to determine the binding free energy of a protein-ligand complex, incorporating the latest advancements in entropy treatment.

System Preparation and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Step 1: Initial Structure Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from PDB or via docking.

- Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign protonation states appropriate for physiological pH.

- For membrane proteins, implement specialized protocols that automatically determine membrane thickness and location [13].

Step 2: Solvation and Electrolyte Addition

- Solvate the complex in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with a minimum buffer distance (e.g., 10-12 Ã…).

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and simulate physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Step 3: Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes (steepest descent/conjugate gradient).

- Equilibrate the system with positional restraints on solute atoms, gradually releasing restraints.

- Conduct production MD simulation in an isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) at 300 K and 1 atm.

Trajectory Processing and Snapshot Extraction

Step 4: Trajectory Analysis and Snapshot Selection

- Remove periodicity and center the complex in the simulation box.

- Align trajectories to a reference structure to eliminate global rotation/translation.

- Extract snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., every 100-200 ps) from the equilibrated portion of the trajectory for MM/PBSA calculations.

Free Energy Calculation and Decomposition

Step 5: Calculate Energy Components For each snapshot, compute:

- Molecular mechanics energy (EMM) using the chosen force field.

- Polar solvation energy (Gpolar) using PB or GB solver.

- Non-polar solvation energy (Gnon-polar) from SASA.

Step 6: Incorporate Entropic Contribution

- Apply formulaic entropy calculation based on SASA variations and rotatable bond count [9].

- Alternatively, for higher accuracy at greater computational cost, perform Normal Mode Analysis on selected snapshots.

Step 7: Ensemble Averaging and Binding Energy Calculation

- Average each energy component over all snapshots.

- Compute final binding free energy using the ensemble-averaged components.

Diagram 2: MM/PBSA calculation workflow from system preparation to binding free energy estimation.

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Membrane Protein Systems

MM/PBSA has been extended for membrane protein-ligand systems through specialized implementations that address unique challenges:

- Automated determination of membrane thickness and location eliminates manual parameter extraction [13].

- Consistent treatment of continuum dielectric in electrostatic energy calculations improves accuracy [13].

- Multitrajectory approaches assigning distinct pre- and post-binding conformations as receptors and complexes, combined with ensemble simulations and entropy corrections, significantly enhance performance for systems like the P2Y12 receptor [13].

Entropy Calculation Methods Comparison

Table 2: Comparison of Entropy Calculation Methods in MM/P(G)BSA

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) | Very High (O(N³)) | High for harmonic systems | Small, rigid systems with sufficient resources |

| Quasi-Harmonic Analysis (QHA) | Medium-High (requires extensive sampling) | Medium (affected by sampling) | Systems where anharmonicity is significant |

| Formulaic Entropy | Low (from single structure) | Medium-High (systematically improves correlation) | High-throughput screening, large systems |

Protocol for Formulaic Entropy Integration

The integration of formulaic entropy represents a significant advancement for practical MM/PBSA applications:

Step 1: For each snapshot, compute the polar and non-polar solvent-accessible surface areas of the ligand. Step 2: Count the number of rotatable bonds in the ligand. Step 3: Apply the empirical formula: Sformulaic = f(ΔSASApolar, ΔSASAnon-polar, Nrotatable) Step 4: Incorporate the entropy directly into the binding free energy calculation without additional structural processing.

This approach has been shown to systematically enhance both MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA performance across diverse datasets, with MM/PBSA_S (including formulaic entropy but excluding dispersion) outperforming other variants [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for MM/P(G)BSA Calculations

| Tool Name | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Software Suite | MD simulations & MM/PBSA | Includes MMPBSA.py for end-state calculations; AMBER24 has new functions for membrane proteins [13] |

| g_mmpbsa | Software Tool | MM/PBSA calculations with APBS | Calculates interaction energies from MD trajectories; works with GROMACS [16] |

| Open Free Energy | Open Source Ecosystem | Binding free energy calculations | MIT-licensed tools for pharmaceutical drug discovery [20] |

| Flare FEP | Commercial Software | Free Energy Perturbation | Quantitative relative & absolute binding affinity calculations [19] |

| APBS | Software Tool | Poisson-Boltzmann Equation Solver | Calculates electrostatic potentials for biomolecules [16] |

| Modeller | Software Tool | Homology Modeling | Models missing loops in protein structures [13] |

| Arborcandin C | Arborcandin C, MF:C59H105N13O18, MW:1284.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MEK-IN-4 | MEK Inhibitor I|RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK Pathway Blocker | MEK Inhibitor I is a selective small molecule targeting the MAPK pathway for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The accurate calculation of binding free energies using MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods requires careful attention to three fundamental energy components: molecular mechanics interactions, solvation effects, and entropic contributions. Recent advancements, particularly the development of formulaic entropy approaches that efficiently compute entropy from single structures, have systematically improved method performance without increasing computational cost [9]. For membrane protein systems, specialized protocols that automate key parameters and ensure consistent dielectric treatment have extended the applicability of these methods [13]. By following the detailed protocols outlined in this application note and leveraging the appropriate tools from the scientist's toolkit, researchers can implement robust MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA calculations to guide drug discovery and design efforts across diverse biological systems.

Historical Development and Growing Adoption in Scientific Literature

Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) are computational methods that estimate the binding free energy of molecular complexes, most commonly protein-ligand interactions. These end-point free energy calculation methods occupy a crucial middle ground in computational drug design, offering a balance between the high computational cost of rigorous alchemical methods like free energy perturbation (FEP) and the limited accuracy of empirical docking scores [1] [21]. First developed by Kollman et al. in the late 1990s, these methods have enjoyed steadily growing adoption, with approximately 100-200 publications annually in recent years [1]. Their popularity stems from the ability to provide physically transparent insights into binding interactions while remaining computationally feasible for many research applications.

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical foundation of MM/PBSA was established with the recognition that binding free energy could be decomposed into distinct physical components. The method calculates the binding free energy (ΔGbind) from the free energies of the receptor-ligand complex (PL), the free receptor (P), and the free ligand (L) using the equation:

ΔGbind = GPL - (GP + GL) [21]

The free energy of each state is estimated as a sum of molecular mechanics energy, solvation contributions, and entropy terms:

G = EMM + Gsolv - TS

Where EMM represents the gas-phase molecular mechanics energy (including bonded, electrostatic, and van der Waals interactions), Gsolv is the solvation free energy, and -TS is the entropic contribution [1]. The solvation term is further decomposed into polar (Gpol) and non-polar (Gnp) components, with the polar component calculated either by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation (MM/PBSA) or using the approximative Generalized Born model (MM/GBSA) [22].

A significant methodological variation concerns the sampling approach. The theoretically rigorous "three-average" method (3A-MM/PBSA) uses separate simulations for the complex, receptor, and ligand. However, the more commonly employed "one-average" approach (1A-MM/PBSA) uses only the complex simulation, extracting the unbound states by molecular separation, which improves precision through cancellation of errors [1].

Table 1: Key Components of MM/PB(GB)SA Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Energy Component | Description | Typical Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanics (EMM) | Gas-phase energy from bonded, electrostatic, and van der Waals interactions | Molecular mechanics force fields (AMBER, CHARMM) |

| Polar Solvation (Gpol) | Electrostatic contribution to solvation | Poisson-Boltzmann equation or Generalized Born model |

| Non-Polar Solvation (Gnp) | Non-electrostatic contribution to solvation | Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) model |

| Entropic Contribution (-TS) | Conformational entropy change upon binding | Normal-mode analysis or quasi-harmonic approximation |

Growing Adoption and Application Diversity

The application spectrum of MM/PB(GB)SA methods has expanded remarkably from initial protein-ligand systems to diverse biological complexes. The method's modular nature and lack of requirement for training data have made it particularly attractive for drug discovery applications [1]. MM/PB(GB)SA has been successfully used to reproduce and rationalize experimental findings and improve the results of virtual screening and docking [1] [21].

Recent methodological extensions have addressed previously challenging systems. For membrane proteins—which constitute over 50% of drug targets but present unique computational challenges—researchers have developed automated approaches for determining membrane thickness and location, significantly enhancing accessibility and accuracy compared to methods relying on default values [23]. These improvements, combined with multitrajectory approaches that assign distinct protein conformations as receptors and complexes, have substantially reduced computational costs while maintaining accuracy [23].

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the utility of these methods in rapid response scenarios. Researchers developed effective MM/GBSA protocols for studying the binding mechanism between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and the human ACE2 receptor, establishing bounds for experimental validation and creating frameworks for studying emerging variants [22]. The method has also been extended to non-traditional systems, including RNA-ligand complexes, where specific parameterization (such as higher interior dielectric constants of εin = 12-20) has shown improved correlation with experimental binding affinities [24].

Table 2: Performance of MM/PB(GB)SA Across Various Biomolecular Systems

| System Type | Performance | Optimal Parameters/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Soluble Proteins | Good correlation with experiment for many systems; improved virtual screening enrichment over docking | Standard dielectric constants; entropy calculation crucial for absolute binding |

| Membrane Proteins | Challenging but improved with recent automated membrane parameterization | Specialized membrane GB models; consideration of membrane thickness and embedding |

| Protein-Protein Complexes | Variable performance; successful application to antibody-antigen systems | Often requires extensive sampling; replica exchange can improve results |

| RNA-Ligand Complexes | Moderate correlation with experiment (Rp = -0.513 with optimized parameters) | Higher interior dielectric constants (εin = 12-20) improve performance |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Effective for ranking congeneric series; identifies key binding interactions | Decomposition analysis reveals hotspot residues; good for lead optimization |

Detailed MM/GBSA Protocol for Binding Free Energy Calculations

System Preparation

Begin with the three-dimensional structure of the protein-ligand complex from crystallography, NMR, or homology modeling. Remove crystallographic water molecules and other non-essential heteroatoms. Add hydrogen atoms using standard protonation states at physiological pH, paying special attention to histidine tautomers. For the ligand, ensure proper bond orders and geometry optimization using quantum mechanical methods such as DFT at the B3LYP/6-311++G level [12].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Solvate the system in an explicit water model (e.g., TIP3P) using a rectangular water box extending at least 10 Ã… from the solute. Add counterions to neutralize system charge. Employ the AMBER or CHARMM force fields with appropriate parameterization for unusual ligands. Energy minimization should proceed in two stages: first restraining solute heavy atoms, then without restraints. Gradually heat the system to 300 K over 100 ps with restrained solute, then equilibrate at constant pressure (1 bar) for 1 ns. Production simulation should run for a sufficient duration to ensure convergence (typically 50-200 ns) with a 2 fs time step using bonds constraint algorithms [25].

Trajectory Processing and Energy Calculation

Extract snapshots at regular intervals (typically 10-100 ps) from the stabilized portion of the trajectory. Remove water molecules and counterions from each snapshot. Calculate molecular mechanics energies using the same force field as in simulation. For solvation energies, select an appropriate GB model (e.g., GBNSR6) or PB solver. For the non-polar solvation term, use a linear relation to the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA). Calculate configurational entropy through normal-mode analysis on a minimized subset of snapshots, considering truncation strategies to reduce computational cost while preserving the binding interface [22].

MM/PBSA Calculation Workflow

Case Study: Membrane Protein Application with Advanced Sampling

A recent study on the P2Y12 receptor (P2Y12R), a G-protein coupled receptor, demonstrates advanced application of MMPBSA to membrane protein systems [23]. This research addressed conformational changes upon ligand binding through a multitrajectory approach that assigned distinct pre- and post-ligand binding conformations as receptors and complexes, combined with ensemble simulations and entropy corrections.

Experimental Protocol

Structure Preparation: Three crystal structures of P2Y12R complexed with antagonist AZD1283 and agonists 2MeSADP or 2MeSATP (PDB: 4NTJ, 4PXZ, 4PY0) were obtained. Missing loops were modeled using Modeller in Chimera, selecting conformations with the lowest DOPE score.

Membrane Simulation Setup: The receptor was embedded in a lipid bilayer using CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder. System neutralization and ion concentration to 0.15 M was achieved with NaCl ions.

Enhanced Sampling: Replica exchange molecular dynamics (T-REMD) was performed with 64 replicas across 300-380 K for 100 ns each, applying positional restraints to residues outside the interaction interface to manage computational costs.

MMPBSA Calculation: The automated membrane parameter calculation in Amber24 was employed, eliminating manual trajectory parsing. Membrane thickness and location were determined automatically rather than using default values. Dielectric consistency was maintained between simulations and continuum electrostatics calculations.

Analysis: Binding free energies were calculated from the 300 K replica, excluding the first 20 ns for equilibration. Truncated normal mode analysis provided entropy estimates focused on the binding interface [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MM/PB(GB)SA Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Molecular dynamics package with MMPBSA.py | Includes automated membrane parameter calculation in Amber24; implements new water models and atomic radii [23] [22] |

| GROMACS | MD simulation package with MM/PBSA support | Open-source alternative; compatible with g_mmpbsa tool for binding energy calculations [25] |

| CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder | Membrane system preparation | Creates realistic lipid bilayers for membrane protein simulations [23] |

| fastDRH Webserver | Automated docking and MM/PBSA | Integrates Autodock Vina and truncated MM/PBSA for rapid screening [21] |

| Modeller | Protein structure homology modeling | Completes missing loops in crystal structures for simulation readiness [23] |

| GBNSR6 GB Model | Generalized Born solvation model | New GB flavor with improved accuracy for binding free energies [22] |

| MAZ51 | MAZ51, MF:C21H18N2O, MW:314.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dihydroartemisinin | Dihydroartemisinin, MF:C15H24O5, MW:284.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Methodological Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Despite their widespread adoption, MM/PB(GB)SA methods contain several approximations that require careful consideration. The neglect of conformational entropy and incomplete treatment of binding site water molecules can limit accuracy [1]. Performance varies substantially across different systems, with most attempts to incorporate more accurate approaches (quantum-mechanical calculations, polarizable force fields) actually deteriorating results rather than improving them [1].

Parameter selection significantly impacts results. For example, in RNA-ligand systems, the GBGBn2 model with higher interior dielectric constants (εin = 12, 16, or 20) yields the best correlation with experimental data [24]. Similarly, for membrane proteins, recommended parameters include a membrane dielectric constant of 7.0 and an internal dielectric constant of 20.0 [21]. These observations highlight the importance of system-specific parameterization.

Sampling represents another critical consideration. While some studies obtain reasonable results from single minimized structures, this approach ignores dynamical effects and loses statistical precision information [1]. Enhanced sampling through replica exchange molecular dynamics (T-REMD) improves configuration space exploration, though it increases computational costs substantially [26]. For binding pose prediction in RNA-ligand systems, MM/GBSA has demonstrated limitations, with success rates (39.3%) below those of specialized docking programs [24].

Methodology Interdependencies

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods have evolved from their initial formulation in the 1990s to become established tools in computational structural biology and drug design. Their growing adoption across diverse biological systems—from soluble proteins to membrane receptors and RNA complexes—demonstrates both their versatility and ongoing development. Recent methodological advances, including automated membrane parameterization, enhanced sampling integration, and system-specific parameter optimization, continue to expand their applicability and reliability. While important limitations remain regarding entropy treatment and sampling requirements, these methods offer an effective balance between computational efficiency and physical rigor for binding affinity estimation in both academic and industrial drug discovery pipelines.

In the landscape of structure-based drug design, computational methods are essential for predicting the binding affinity of small molecules to biological targets. These methods exist on a spectrum, balancing computational cost with predictive accuracy. At one end, molecular docking is fast but often lacks the accuracy for quantitative affinity predictions. At the opposite end, alchemical free energy methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI) offer high accuracy but are computationally intensive and complex to set up. Occupying a crucial middle ground are the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) methods. These end-point approaches leverage molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to offer a balanced compromise, providing more physical realism and accuracy than docking while remaining significantly less demanding than full alchemical calculations [1] [21]. This document details the positioning, application, and protocol for these intermediate methods within a broader research context.

Methodological Foundation and Strategic Positioning

The Computational Spectrum in Drug Design

The selection of a computational method in drug discovery is typically a trade-off between speed and accuracy. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the main classes of binding affinity prediction methods:

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Binding Affinity Prediction

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Typical Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking & Scoring | Low (seconds-minutes) | Low to Moderate | Virtual screening, binding mode prediction [1] | Simplified treatment of solvent, entropy, and protein flexibility [21] |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | Intermediate (hours-days) | Moderate | Binding affinity ranking, virtual screening re-scoring, mechanistic studies [1] [21] | Crude approximations in entropy and solvation terms; performance is system-dependent [1] [8] |

| Alchemical (FEP, TI) | High (days-weeks) | High | Lead optimization for congeneric series [27] [28] [29] | Computationally intensive; complex setup; requires chemical similarity for RBFE [29] [30] |

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA are classified as end-point methods, meaning they primarily use structural information from the initial (unbound) and final (bound) states of the binding process, typically obtained from MD simulations [1] [2]. The fundamental equation for the binding free energy, ΔGbind, is:

ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Gprotein + Gligand)

Where the free energy (G) for each species (complex, protein, ligand) is calculated as [1] [2]:

G = EMM + Gsolv - TS

- EMM: The molecular mechanics energy from bonded (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded (electrostatic, van der Waals) interactions.

- Gsolv: The solvation free energy, decomposed into:

- -TS: The entropic contribution, which is computationally expensive to calculate and is often estimated via normal mode analysis or interaction entropy methods [8].

Practical Workflows and Sampling Strategies

Two primary sampling strategies are employed in MM/PBSA/GBSA:

- One-Average (1A-MM/PBSA): The most common approach. It uses a single MD simulation of the protein-ligand complex. The structures of the unbound protein and ligand are generated by simply deleting the other component from each snapshot of the complex trajectory. This improves precision and leads to a beneficial cancellation of the bonded energy terms (Ebnd) [1].

- Three-Average (3A-MM/PBSA): This approach uses three separate MD simulations: one for the complex, one for the unbound protein, and one for the free ligand. While this can account for conformational changes upon binding, it is more computationally expensive and can lead to much larger uncertainties [1].

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a MM/PBSA/GBSA calculation using the single-trajectory approach.

Performance and Validation

The performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA is not uniform and depends heavily on the system being studied and the specific parameters used. A large-scale study assessing entropy effects on over 1500 protein-ligand systems found that the inclusion of conformational entropy could improve the agreement with experimental absolute binding free energies, particularly when calculated from MD trajectories rather than minimized structures [8]. The interaction entropy (IE) approach was highlighted as a computationally efficient method to estimate entropic contributions, providing results comparable to more expensive normal mode analysis [8].

These methods have been successfully applied to reproduce and rationalize experimental findings and to improve the results of virtual screening and docking [1] [21]. For example, when used to re-score the top hits from docking calculations, MM/PBSA can improve the enrichment of active compounds over decoys [21]. However, it is crucial to recognize the limitations. The methods contain several crude approximations, such as the common neglect of conformational entropy or the treatment of water molecules in the binding site, which can limit their predictive accuracy for some systems [1]. Furthermore, most attempts to improve the methods with more advanced physical models (e.g., quantum mechanics, polarizable force fields) have, perhaps counterintuitively, deteriorated the results, suggesting a complex balance of error cancellations in the standard approach [1].

Detailed Protocol for MM/GBSA Calculation

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for performing a MM/GBSA calculation using the AMBER software suite and the MMPBSA.py script, a common and well-documented tool for this purpose [10].

System Setup and MD Simulation

- Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from a source like the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Use a tool like the Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrödinger) or

pdb4amber(AMBER) to add missing hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and correct missing side chains. - Ligand Parameterization: Generate force field parameters for the small molecule ligand. Use the GAFF2 (Generalized Amber Force Field 2) with partial charges derived from methods like AM1-BCC, using the

antechamberprogram in AMBER [10]. - Generate Topology and Coordinate Files: Use the

tleapmodule in AMBER to load the protein (e.g., using the ff14SB or ff19SB force field), ligand (GAFF2), and solvent (e.g., TIP3P) models. Solvate the complex in a rectangular water box with a buffer of at least 10 Ã…, and add ions to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiological salt concentration (~0.15 M NaCl). - Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Energy Minimization: Perform a series of minimizations to remove bad contacts, first restraining the heavy atoms of the protein and ligand, then releasing the restraints.

- System Heating: Gradually heat the system from 0 K to 300 K over 50-100 ps in the NVT ensemble, with weak restraints on solute heavy atoms.

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 100-500 ps in the NPT ensemble (constant pressure) at 300 K to achieve the correct density.

- Production Run: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a sufficient length of time (typically 50-500 ns, depending on system stability) to sample relevant conformations. Save snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) for the MM/GBSA calculation.

MM/GBSA Calculation with MMPBSA.py

- Input Preparation: Create an input file for

MMPBSA.py. A typical example is shown below. - Script Execution: Run the

MMPBSA.pyscript, which will process the MD trajectory, calculate the energies for each snapshot, and output the results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MM/PBSA/GBSA Calculations

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Sources / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | Performs molecular dynamics simulation to generate structural ensembles. | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM |

| MMPBSA.py | The primary tool for performing the end-point free energy calculation. | Packaged with AMBER/AmberTools [10] |

| Force Fields | Defines potential energy parameters for molecules. | Proteins: ff14SB, ff19SB [8]. Ligands: GAFF/GAFF2 with AM1-BCC charges [8] [10]. |

| Solvation Model | Calculates polar solvation energy (ΔGpolar). | GB (GBSA): Faster, approximate (e.g., GBOBC1, GBHCT). PB (PBSA): Slower, more rigorous [21]. |

| Entropy Estimation | Calculates the entropic contribution (-TΔS). | Normal Mode Analysis: Computationally expensive. Interaction Entropy (IE): More efficient, recommended for diverse datasets [8]. |

Sample MMPBSA.py Input File:

Explanation of key parameters:

startframe, endframe, interval: Control which snapshots from the trajectory are analyzed.entropy=1: Enables entropy calculation (e.g., via quasi-harmonic or normal mode analysis).igb=2: Specifies the GB model (e.g., GBOBC1).istrng=0.150: Sets the ionic strength to 0.15 M.inp=2: Sets the internal dielectric constant for the protein (a common value is 2-4) [10].

Application Notes and Integration in Drug Discovery

MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations are best deployed in specific scenarios within the drug discovery pipeline:

- Re-scoring in Virtual Screening: After an initial high-throughput docking screen of a diverse compound library, MM/GBSA can be used to re-score the top hits (e.g., 100-1000 compounds). This provides a more physically rigorous ranking than docking scores alone, improving the enrichment of true actives [21].

- SAR Rationalization: When a series of analogs with measured activity is available, MM/GBSA can decompose the binding free energy per residue. This helps explain the structural origin of affinity differences, guiding the medicinal chemist on which parts of the molecule to modify [1].

- System-Specific Considerations: The performance is highly system-dependent. Testing different internal dielectric constants (εin), solvation models (GB vs. PB), and entropy treatments is critical for achieving optimal results [8] [21]. For example, one study recommends a membrane dielectric constant of 7.0 and an internal dielectric constant of 20.0 for membrane-bound proteins [21].

The following diagram situates MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA within the broader context of a structure-based drug design campaign, illustrating its typical point of application relative to other free energy methods.

Practical Implementation and Real-World Applications

Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) are established computational methods that estimate binding free energies for biomolecular complexes by combining molecular mechanics energies with implicit solvation models [1] [31]. These end-point methods occupy a crucial middle ground in the accuracy-efficiency spectrum, being more theoretically rigorous than empirical docking scores yet less computationally demanding than alchemical perturbation methods like free energy perturbation (FEP) or thermodynamic integration (TI) [1] [32]. A fundamental methodological choice when implementing these approaches is whether to use a single-trajectory or multi-trajectory protocol, each with distinct trade-offs in accuracy, precision, and computational resource requirements [1].

In the single-trajectory approach (often termed 1A-MM/PBSA), the ensemble averages for the free energy calculation are generated from a single molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of the protein-ligand complex [1]. Snapshots from this trajectory are used to calculate the free energy of the complex (GPL), while the free receptor (GP) and ligand (GL) energies are approximated by simply removing the complementary component from each snapshot. This approach benefits from significant error cancellation, particularly for the internal bonded energy terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals), which are completely eliminated from the binding free energy equation [1]. Consequently, it generally provides superior statistical precision [1].

In contrast, the multi-trajectory approach (specifically the three-trajectory method, 3A-MM/PBSA) employs three separate MD simulations: one for the complex, one for the unbound receptor, and one for the free ligand in solution [1]. The binding free energy is then calculated using the ensemble averages from each independent simulation. This method is theoretically more rigorous as it accounts for structural reorganization of both the receptor and ligand upon binding—a potentially significant energetic contribution [1]. However, this comes at the cost of increased computational resources and, critically, much larger statistical uncertainties in the final binding free energy estimate because there is no cancellation of variances between the three independent simulations [1].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Single vs. Multi-Trajectory Approaches

| Feature | Single-Trajectory (1A) | Multi-Trajectory (3A) |

|---|---|---|

| Simulations Required | One (Complex only) | Three (Complex, Receptor, Ligand) |

| Handling of Binding-Induced Reorganization | Neglects structural changes in unbound states | Accounts for conformational changes upon binding |

| Statistical Precision | High (due to variance cancellation) | Low (4-5 times larger standard error [1]) |

| Computational Cost | Lower | ~3x Higher |

| Cancellation of Internal Energies | Complete | Not applicable |

| Recommended Use Case | Congruent bound/unbound states; high-throughput scoring | Systems with significant binding-induced conformational changes |

Performance Comparison and Statistical Implications

The choice between single and multi-trajectory protocols has a profound impact on the outcome and reliability of MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations. Multiple studies indicate that the single-trajectory approach often yields more accurate and significantly more precise results compared to the multi-trajectory alternative [1]. The primary reason is statistical: the standard error for binding free energies calculated with the three-trajectory approach can be four to five times larger than that of the single-trajectory method [1]. This high level of uncertainty can, in some cases, render the results from the 3A approach practically useless for distinguishing between ligands, as the error bars become large enough to encompass the binding free energies of multiple compounds [1].

For instance, in a study on the ferritin protein, the statistical uncertainty associated with the three-trajectory MM/PBSA method was a massive 19–21 kJ/mol, making it impossible to draw meaningful conclusions from the calculations [1]. Similarly, Pearlman reported comparable challenges with the p38 MAP kinase system [1]. This does not mean the 1A approach is universally superior. Its critical limitation is the underlying assumption that the conformations of the unbound receptor and ligand are well-represented by their bound-state geometries [1] [33]. For systems where binding involves substantial conformational rearrangements, this assumption fails, introducing a systematic error that can outweigh the benefits of improved precision.

The single-trajectory method demonstrates particular utility in virtual screening (VS) and binding pose ranking, where computational efficiency and high precision are paramount for discriminating between many compounds. A large-scale assessment using the Moira (molecular dynamics trajectory analysis) framework, which analyzed hundreds of trajectories, supports the use of efficient, trajectory-based analysis for distinguishing native binding poses from decoys [33]. However, for systems with known large-scale flexibility, the multi-trajectory approach remains a critical, albeit more expensive and noisier, tool for capturing the true thermodynamics of binding.

Advanced Protocols and Methodological Refinements

Specialized Multi-Trajectory Protocol for Membrane Proteins

A sophisticated multi-trajectory protocol was recently developed to address the challenge of calculating binding free energies for membrane proteins, exemplified by the P2Y12 receptor (P2Y12R) [23]. This method strategically assigns distinct protein conformations (pre- and post-ligand binding) as the "receptor" and "complex" states within the MM/PBSA framework. For example, the structure of P2Y12R bound to an antagonist (AZD1283) was used to represent the "complex," while the structures of P2Y12R bound to nucleotide agonists (2MeSADP, 2MeSATP) were treated as the "receptor" state to model the conformation before antagonist binding [23]. This innovative use of multiple experimental structures in a multi-trajectory setup, combined with ensemble simulations and entropy corrections, significantly improved the accuracy of binding free energy predictions for this pharmaceutically important target while managing computational costs [23].

The Critical Role of Entropy Calculations

The treatment of entropy is a major source of variation in MM-PBSA/GBSA studies. The conformational entropy change (─TΔS) is often omitted due to the prohibitive cost of normal mode analysis (NMA) on thousands of MD snapshots [8]. Research investigating over 1500 protein-ligand systems reveals that including entropic contributions requires careful strategy [8]. For binding free energies calculated from energy-minimized structures, adding conformational entropy generally worsens the agreement with experiment. However, for calculations based on MD trajectories, accuracy can be improved by including entropy estimated either through a computationally efficient truncated-NMA (for a high solute dielectric constant, εin = 4) or the interaction entropy method (for εin = 1–4) [8]. The interaction entropy method is particularly attractive as it provides comparable or even better results than truncated-NMA without incurring significant additional computational cost, making it highly suitable for diverse datasets [8].

Decision Framework and Best Practices

The following workflow diagram synthesizes the key decision points and best practices for choosing between single and multi-trajectory approaches, incorporating insights on entropy and system preparation.

Successful implementation of MM-PBSA/GBSA methodologies requires a suite of specialized software tools and careful parameter selection. The table below details key resources and their primary functions in conducting these calculations.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for MM-PBSA/GBSA Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in MM-PBSA/GBSA |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER [23] | Software Suite | The most widely used suite for MD simulations and post-processing MM/PBSA/GBSA calculations; includes the MMPBSA.py script. |

| GROMACS with g_mmpbsa [31] | Software Suite | An alternative high-performance MD engine with a dedicated tool for MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA post-processing. |

| Schrödinger Prime MM-GBSA [14] | Software Module | Provides a user-friendly, integrated implementation of MM/GBSA for single-conformation or dynamics trajectory-based calculations. |

| Flare MM/GBSA [14] | Software Module | A dedicated implementation offering a variety of implicit solvent models for calculating binding free energies from single structures or dynamics. |

| Moira Framework [33] | Analysis Pipeline | A framework for automating the workflow from molecular docking and MD simulations to multiple trajectory analysis methods (RMSD, PLIP, MM/PBSA). |

| PDBbind Database [33] | Data Resource | A curated database of protein-ligand complex structures and binding affinities essential for method calibration, testing, and validation. |

The decision to employ a single or multi-trajectory approach in MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations is not one-size-fits-all but must be guided by the specific biological system and the trade-offs between statistical precision and thermodynamic rigor. The single-trajectory (1A) method, with its superior precision and lower computational cost, is recommended for most applications, particularly virtual screening and systems without large binding-induced conformational changes. In contrast, the multi-trajectory (3A) approach remains a vital, though more specialized, tool for systems where conformational reorganization is a critical component of the binding mechanism, such as with many membrane proteins and allosteric systems. By adhering to the structured decision framework and best practices outlined herein—including the strategic use of interaction entropy for solvation and the selection of appropriate force fields—researchers can robustly apply these powerful end-point methods to advance drug discovery and molecular recognition studies.

The accurate calculation of binding free energies is a crucial objective in structure-based drug design, providing a quantitative measure of how tightly a small molecule ligand binds to a biological macromolecule [1]. Among the computational methods available, the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) approaches have gained significant popularity as tools with intermediate accuracy and computational cost between empirical scoring and more rigorous alchemical perturbation methods [1]. These end-point methods utilize molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to generate structural ensembles, then apply continuum solvation models to estimate binding affinities [2]. This protocol details a comprehensive, practical workflow for implementing these methods, framed within ongoing research efforts to improve their accuracy and efficiency in drug discovery applications.

Theoretical Foundation of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA

Fundamental Equations

In MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA approaches, the binding free energy (ΔGbind) for the reaction L + R ⇌ RL (where L is the ligand, R is the receptor, and RL is the complex) is calculated as [1] [2]:

ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Greceptor + Gligand)

The free energy of each species (X) is estimated from the following components [2]:

GX = ⟨EMM⟩ + ⟨Gsolv⟩ - T⟨S⟩

Where:

- ⟨EMM⟩ represents the average molecular mechanics potential energy in vacuum

- ⟨Gsolv⟩ represents the average solvation free energy

- T is the absolute temperature

- ⟨S⟩ represents the average conformational entropy

The molecular mechanics term can be decomposed as [2]:

EMM = Ecovalent + Eelectrostatic + EvdW

Ecovalent = Ebond + Eangle + Etorsion

The solvation free energy is separated into polar and non-polar contributions [2]:

Gsolv = Gpolar + Gnon-polar

Key Methodological Variations

Several implementation variants exist, primarily differing in their sampling strategies [1]:

- One-average approach (1A-MM/PBSA): Uses only a simulation of the complex, with the unbound receptor and ligand created by atom removal [1]

- Three-average approach (3A-MM/PBSA): Employs three separate simulations for the complex, receptor, and ligand [1]

The 1A approach is more commonly used due to better convergence and cancellation of errors, though it ignores structural changes upon binding [1].

Table 1: Comparison of MM/PBSA Implementation Approaches

| Approach | Simulations Required | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-average (1A) | Complex only | Better convergence, computational efficiency, error cancellation | Ignoers reorganization energy upon binding |

| Three-average (3A) | Complex, receptor, and ligand | Accounts for structural changes | Poor convergence, large uncertainty |

| Two-average (2A) | Complex and ligand | Includes ligand reorganization | Limited application in literature |

Computational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete MM/PBSA/GBSA workflow from initial system preparation to final binding free energy calculation:

System Preparation and MD Simulations

Initial Structure Preparation

Begin with a high-resolution structure of the protein-ligand complex, obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or docking studies. Critical preparation steps include:

- Add missing atoms and residues: Complete any incomplete side chains or loops