Navigating Biological Variability in Lipidomics: From Experimental Design to Clinical Translation

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, is increasingly recognized for its role in precision health, with profiles often predicting disease onset years earlier than genetic markers.

Navigating Biological Variability in Lipidomics: From Experimental Design to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, is increasingly recognized for its role in precision health, with profiles often predicting disease onset years earlier than genetic markers. However, the inherent biological variability of lipids—driven by circadian rhythms, diet, and individual metabolism—poses a significant challenge to data reproducibility and clinical interpretation. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address this variability. We explore the foundational sources of lipid fluctuation, present advanced methodological approaches for robust data acquisition, detail statistical workflows for troubleshooting and normalization, and establish best practices for validating lipid-based biomarkers. By synthesizing the latest technological advances and analytical strategies, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and clinical applicability of lipidomic studies.

Understanding the Sources and Impact of Lipid Fluctuation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is a single time-point measurement insufficient for understanding lipid dynamics in my study? Lipid concentrations are highly dynamic and fluctuate in response to factors like circadian rhythm, dietary habits, and stress [1]. A single snapshot cannot capture these temporal patterns, which are crucial for understanding metabolic health and disease progression. Studies show that lipid profiles can reveal disease onset 3-5 years earlier than genetic markers, but this requires observing changes over time [2].

FAQ 2: What is the primary source of variability in lipidomics data, and how can I account for it? The major source of variability is biological (between-subject and within-subject), not technical. High-throughput LC-MS/MS studies demonstrate that biological variability significantly exceeds analytical batch-to-batch variability [3]. Accounting for this requires a study design that includes repeated measurements over time and the use of appropriate quality controls, such as National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) reference materials, to isolate technical noise from true biological signal [3] [1].

FAQ 3: Which lipid classes have the biggest impact on health and should be prioritized in longitudinal studies? Two major lipid classes have emerged as particularly significant:

- Phospholipids: Form the structural foundation of all cell membranes and determine cellular function. Their composition impacts how cells respond to hormones and medications, and abnormalities can precede insulin resistance by up to five years [2].

- Sphingolipids (particularly ceramides): Function as powerful signaling molecules that regulate inflammation, cell death, and metabolic processes. Elevated ceramide levels strongly predict cardiovascular events, and ceramide risk scores now outperform traditional cholesterol measurements in predicting heart attack risk [2].

FAQ 4: My lipidomics dataset has many missing values. How should I handle them before statistical analysis? The strategy depends on the nature of the missing data:

- Missing Not at Random (MNAR): If values are missing because they are below the detection limit, imputation with a percentage (e.g., half) of the lowest measured concentration for that lipid is often effective [1].

- Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) or at Random (MAR): k-nearest neighbors (kNN)-based imputation or random forest methods are generally recommended [1]. Before imputation, it is best practice to filter out lipid species with a high percentage of missing values (e.g., >35%) across samples [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Unwanted Variation in Lipidomics Data

Problem: Data is dominated by technical noise from batch effects or sample preparation inconsistencies, obscuring the biological signal.

Solution: Implement a rigorous quality control (QC) and normalization protocol.

- Step 1: Pre-acquisition Sample Preparation. Normalize sample aliquots based on cell count, protein amount, or volume before processing [1].

- Step 2: Use Quality Control Samples. Intersperse pooled QC samples (from all study samples) or commercial reference materials (e.g., NIST SRM 1950) throughout the analysis batch [3] [1].

- Step 3: Post-acquisition Normalization.

- With Internal Standards: Use software like ADViSELipidomics to normalize raw data against internal lipid standards, correcting for instrument response and lipid recovery efficiency to obtain absolute concentrations [4].

- Without Internal Standards: Apply statistical normalization methods (e.g., median, probabilistic quotient normalization) to remove batch effects [1].

Issue 2: Inability to Capture Cellular Heterogeneity

Problem: Bulk lipid analysis of tissues or cell populations averages the signal, masking crucial cell-to-cell differences.

Solution: Employ single-cell lipidomics or spatial lipidomics techniques.

- Step 1: Choose the Appropriate Technology. Utilize advanced mass spectrometry such as high-resolution Orbitrap or Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) MS for ultra-sensitive profiling of individual cells [5].

- Step 2: Incorporate Spatial Context. For tissue samples, apply Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) techniques like MALDI-MSI or SIMS. This visualizes the distribution of lipids within a tissue, revealing spatial heterogeneity related to cellular function and disease pathology [5].

- Step 3: Data Integration. Combine single-cell lipidomic data with transcriptomic or proteomic data from the same cells to unravel lipid-mediated regulatory networks [5].

Issue 3: Interpreting Statistically Significant Lipid Lists

Problem: After statistical analysis, you have a list of differentially abundant lipids but struggle to extract biological meaning.

Solution: Follow a structured data analysis and interpretation workflow.

- Step 1: Robust Statistical Processing. Use tools in R or Python for hypothesis testing (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA with FDR correction) and dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA, PLS-DA) to identify key lipid species [1].

- Step 2: Pathway and Enrichment Analysis. Input the significant lipid list into tools like MetaboAnalyst or LipidSig to identify enriched metabolic pathways (e.g., using Over-Representation Analysis) [6].

- Step 3: Biological Interpretation. Contextualize the results by cross-referencing with existing literature in databases like LIPID MAPS and PubMed. Generate testable hypotheses about the functional role of the altered lipids, for example, in membrane integrity or inflammatory signaling [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standardized Protocol for Longitudinal Plasma Lipidomics

This protocol is designed for large-scale clinical studies to ensure high-throughput and reproducible measurement of the circulatory lipidome over time [3].

- Sample Collection: Collect fasted plasma samples in specialized tubes that prevent lipid oxidation at multiple time points from each participant.

- Sample Preparation (Semi-automated): Use a stable isotope dilution approach for robust and accurate quantification during the extraction process.

- Quality Control: Include the NIST plasma reference material as a QC in every batch to monitor analytical performance.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Apply a high-coverage hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) method to separate a wide range of lipid classes. The MS should be operated in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or targeted mode.

- Data Processing: Use software like LIQUID or LipidSearch for peak picking, lipid identification, and integration. Process the QC samples to assess between-batch reproducibility, aiming for a median coefficient of variation (CV) <15% [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for robust lipidomics studies.

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| NIST SRM 1950 | Standardized reference material of human plasma; used to monitor batch-to-batch reproducibility and accuracy across longitudinal studies [3] [1]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to each sample prior to extraction; corrects for variations in sample preparation and MS ionization efficiency, enabling absolute quantification [3]. |

| Pooled QC Samples | A quality control created by mixing a small aliquot of every biological sample in the study; used to monitor instrument stability and for data normalization [1]. |

| LIPID MAPS Database | A curated database providing standardized lipid classification, structures, and nomenclature; essential for accurate lipid identification and reporting [5] [4]. |

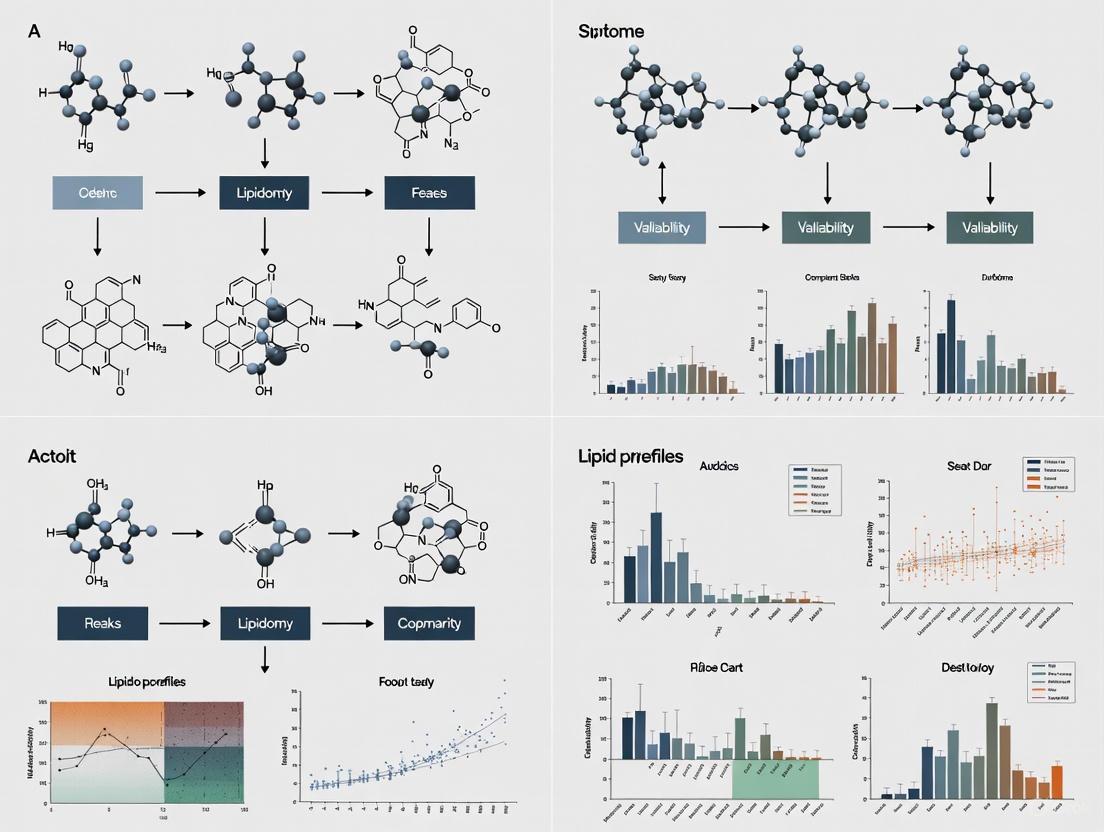

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Longitudinal lipidomics workflow.

Diagram 2: Data analysis pipeline.

FAQs on Circadian Lipid Biology

What percentage of lipids show circadian rhythmicity?

Approximately 13% to 25% of the plasma lipidome demonstrates endogenous circadian regulation under controlled conditions [7] [8]. This rhythmicity spans multiple lipid classes, including glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids. At an individual level, the percentage of rhythmic lipids can range much higher—from 5% to 33% across different people—highlighting significant interindividual variation [7].

How consistent are lipid rhythms between individuals?

There is striking interindividual variability in lipid circadian rhythms. When comparing which specific lipid species are rhythmic between subjects, the median agreement is only about 20% [7]. The timing of peak concentrations (acrophase) for the same lipid can vary by up to 12 hours between individuals [7]. This suggests the existence of different circadian metabolic phenotypes in the population.

Does aging affect circadian lipid rhythms?

Yes, healthy aging significantly alters circadian lipid regulation. Middle-aged and older adults (average age ~58 years) exhibit:

- ~14% lower rhythm amplitude [8]

- ~2.1 hour earlier acrophase (peak timing) [8]

- Greater prevalence of combined sinusoidal and linear trends across constant routines (44/56 lipids in older vs. 18/58 in younger adults) [8]

These changes occur despite preservation of central circadian timing, suggesting peripheral clock alterations.

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Challenge: High Variability in Lipid Measurements

Problem: Lipid measurements show unexpected variability, potentially obscuring circadian signals.

Solutions:

- Control sampling time: Collect samples at consistent circadian times across subjects [7] [8]

- Account for age effects: Stratify analyses by age group or include age as covariate [8]

- Use repeated measures: Collect multiple samples from the same individuals over time [9]

- Implement constant routines: For precise circadian assessment, use constant routine protocols that eliminate masking effects from sleep, posture, and feeding [8] [10]

Challenge: Discrepancies Between Group and Individual Rhythms

Problem: Lipids that appear arrhythmic in group-level analyses show clear rhythms at individual levels.

Solutions:

- Perform individual-level rhythm analysis in addition to group-level analyses [7] [11]

- Increase sampling frequency to better capture individual patterns [7]

- Cluster subjects based on rhythmicity patterns using consensus clustering with iterative feature selection [7]

Table 1: Circadian Lipid Rhythm Characteristics Across Studies

| Parameter | Young Adults | Older Adults | Interindividual Range | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhythmic Lipids | 13-25% | ~25% (reduced amplitude) | 5-33% | [7] [8] |

| Amplitude Reduction | - | ~14% | - | [8] |

| Phase Advancement | - | ~2.1 hours | Up to 12 hours | [7] [8] |

| Interindividual Agreement | ~20% | - | - | [7] |

Table 2: Phase Response Curve Magnitudes for Lipids vs. Melatonin

| Analyte | Maximum Phase Shift (hours) | PRC Pattern vs. Melatonin | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin | ~3.0 | Reference | [10] |

| Triglycerides | ~8.3 | Generally greater shifts | [10] |

| Albumin | ~7.1 | Similar timing | [10] |

| Total Cholesterol | ~7.2 | Offset by ~12 hours | [10] |

| HDL-C | ~4.6 | Offset by ~12 hours | [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Constant Routine Protocol for Endogenous Rhythm Assessment

The constant routine (CR) protocol is the gold standard for assessing endogenous circadian rhythms without environmental masking [8] [10].

Key Components:

- Duration: 27-55 hours of continuous wakefulness [8] [10]

- Posture: Maintain semi-recumbent position [8]

- Lighting: Constant dim light (<10 lux) to eliminate photic entrainment [10]

- Nutrition: Identical isocaloric snacks hourly to eliminate feeding-fasting effects [10]

- Sampling: Blood collection every 3-4 hours for lipidomic analysis [7] [8]

Applications: Isolates endogenously generated oscillations from evoked changes in lipid physiology [8].

Phase Response Curve Assessment Protocol

This protocol characterizes how lipid rhythms shift in response to zeitgebers like light and meals [10].

Procedure:

- Initial CR (CR1): Assess baseline circadian phase

- Intervention Day: 16-hour combined light (6.5h blue light) and meal exposure

- Systematic Variation: Schedule intervention at different circadian phases across participants

- Final CR (CR2): Assess phase shifts in lipid rhythms

Outcome: Generates phase response curves showing direction/magnitude of lipid rhythm shifts [10].

Visualization of Circadian Lipid Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC/MS Systems | Targeted lipidomics profiling of 260+ lipid species | Quantitative measurement of glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids [7] |

| UPLC-QTOF-MS | Untargeted lipidomics with high resolution | Comprehensive skin surface lipid analysis [12] [13] |

| Constant Routine Facilities | Environmental control for circadian studies | Eliminating masking effects from light, feeding, activity [8] [10] |

| Cosinor Analysis Software | Statistical identification of circadian rhythms | Determining acrophase, amplitude, significance of rhythms [7] [8] |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Absolute quantification of lipid species | Normalizing lipid measurements in complex mixtures [9] |

| AZ13705339 | AZ13705339, MF:C33H36FN7O3S, MW:629.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kif18A-IN-12 | Kif18A-IN-12, MF:C30H39F2N5O4S, MW:603.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Key Technical Recommendations

- Standardize sampling times across participants to minimize circadian variability [7] [9]

- Account for age effects in study design and statistical analysis [8]

- Consider individual metabolic phenotypes rather than assuming uniform rhythms [7]

- Use appropriate statistical methods (Cosinor, JTK_CYCLE) designed for circadian analysis [7] [8]

- For intervention studies, note that lipid rhythms may shift differently than melatonin rhythms [10]

Understanding and accounting for circadian regulation is essential for reducing variability and improving reproducibility in lipidomic studies.

Dietary and Metabolic Drivers of Short-Term Lipid Variability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary biological factors that cause short-term lipid variability?

Short-term fluctuations in lipid levels are driven by several key biological and lifestyle factors. Dietary intake is a major driver; saturated fatty acids (SFA) from foods like milk, butter, cheese, and red meat increase LDL-C, while monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids from sources like olive oil and nuts lower LDL-C [14]. Carbohydrate quality also plays a significant role; low-quality carbohydrates, particularly simple sugars and fructose, promote hepatic de novo lipogenesis, leading to a robust increase in triglycerides (TG) [14]. Furthermore, non-fasting states, recent exercise, alcohol consumption, and circadian rhythms contribute to dynamic changes in the lipidome over short timeframes [15] [16].

How does short-term dietary fat intake specifically alter lipid profiles?

Short-term changes in dietary fat composition can rapidly influence circulating lipid levels. The table below summarizes the effects of different dietary fats on key lipoproteins [14]:

| Dietary Constituent | Major Food Sources | Effect on LDL-C | Effect on HDL-C | Effect on TGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Fatty Acids (SFA) | Milk, butter, cheese, beef, pork, poultry, palm oil, coconut oil | Increase | Modest increase | Neutral |

| Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) | Olive oil, canola oil, avocados, nuts, seeds | Decrease | Neutral | Neutral |

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) | Soybean oil, corn oil, sunflower oil, tofu, soybeans | Decrease | Neutral | Neutral |

| Trans Fatty Acids (TFA) | Naturally in meat/dairy; formed in hydrogenated oils | Increase | Decrease | Neutral |

| Dietary Cholesterol | Egg yolks, shrimp, beef, pork, poultry, cheese, butter | Modest increase (highly variable) | Neutral | Neutral |

Replacing SFA with PUFA in the diet not only lowers LDL-C but is also associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [14]. Short-term high-fat feeding studies have specifically demonstrated its impact on postprandial lipemia, the temporary increase in blood triglycerides after a meal [17].

Why is understanding lipid variability critical for lipidomic study design and interpretation?

Accounting for lipid variability is essential for both the statistical power and biological validity of lipidomics research. High within-individual variance can severely attenuate observed effect sizes in association studies, requiring larger sample sizes to detect true relationships [9]. For instance, one study estimated that to detect a relative risk of 3.0 with high confidence, a case-control study would require a total of 1,000 participants to achieve 57% power, and 5,000 participants to achieve 99% power, after correcting for multiple comparisons [9].

Moreover, lipid variability is not just noise; it can be a meaningful clinical signal. Studies using electronic health records have shown that high variability in total cholesterol, LDL-C, and HDL-C—measured as the variation independent of the mean (VIM) from at least three measurements—is associated with an increased risk of incident cardiovascular disease, independent of traditional risk factors and mean lipid levels [18]. This underscores that fluctuating lipid levels may themselves be a pathophysiological risk marker.

What is the typical magnitude of lipid changes one can expect from short-term dietary interventions?

The average lipid response to dietary changes is relatively modest, typically in the range of ~10% reductions [14]. However, the response can vary significantly between individuals due to factors like genetics. For example, individuals with an apo E4 allele experience a more robust decrease in LDL-C in response to a reduction in dietary fat and cholesterol than those with other variants [14]. Clinical conditions also modulate this response, as the expected lipid-lowering effect of a low SFA diet is blunted in obese individuals [14]. This highlights the importance of personalized approaches and monitoring individual responses in both clinical and research settings.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Impact of Short-Term Diet on the Plasma Lipidome

This protocol outlines a randomized crossover dietary intervention study to measure acute lipidomic changes.

1. Study Design:

- Design Type: Randomized, controlled, crossover trial.

- Participants: Recruit healthy participants or a cohort with a specific metabolic phenotype (e.g., insulin-sensitive vs. insulin-resistant) [16].

- Intervention Diets: Participants consume isoenergetic diets differing in macronutrient composition for a short term (e.g., 3 days) [17].

- High-Carbohydrate Diet: For example, 75% of total energy (TE) from carbohydrates, 10% TE from fat.

- High-Fat Diet: For example, 40% TE from fat, 45% TE from carbohydrates [17].

- Washout Period: A sufficient washout period (e.g., several days to weeks) is implemented between dietary phases to avoid carryover effects.

2. Sample Collection:

- Timeline: Collect fasting plasma samples before the diet (baseline) and at the end of the intervention period. To capture postprandial lipemia, collect additional samples at specific timepoints (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6 hours) after a standardized test meal on the final day [17].

- Standardization: Control for pre-analytical variables by standardizing the blood draw time of day to account for circadian rhythms, and ensure consistent processing protocols (e.g., centrifugation speed/time, storage at -80°C) for all samples [15].

3. Lipidomic Profiling:

- Platform: Use a high-throughput quantitative lipidomics platform like the Lipidyzer, which combines liquid chromatography (LC) with a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS) and differential mobility separation (DMS) [16].

- Internal Standards: Spike all samples with a mix of deuterated internal standards immediately upon sample preparation to enable accurate quantification and control for extraction efficiency and instrument variance [16].

- Batch Randomization: Randomize samples across analytical batches to ensure that the factor of interest (diet) is not confounded with batch effects or measurement order [19].

- Quality Control (QC): Inject pooled QC samples (made from an aliquot of all samples) repeatedly at the beginning of the run, after every batch of experimental samples, and at the end to monitor and correct for instrumental drift [19].

4. Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Perform peak picking, alignment, and normalization. Use the QC samples for batch effect correction and signal drift compensation.

- Quantification: Calculate lipid species concentrations using the ratio of target compound peak areas to their assigned deuterated internal standard [9] [16].

- Statistical Analysis: Use paired t-tests or linear mixed models to identify lipid species and classes that are significantly altered between the two dietary regimens. Employ False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Intra-Individual Lipid Variability from Longitudinal Data

This protocol describes how to calculate and interpret lipid variability from serial measurements, such as those from electronic health records (EHR) or dedicated longitudinal cohorts.

1. Data Source and Cohort Definition:

- Source: Identify individuals with at least three measurements of a lipid type (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, or triglycerides) taken on different days over a defined period (e.g., 5 years) [18].

- Cohort: Define a baseline index date. Include individuals without prior cardiovascular disease at baseline to study variability as a risk factor for incident events [18].

2. Calculation of Lipid Variability:

- Metric: Use Variability Independent of the Mean (VIM). VIM is robust to the statistical issue of heteroscedasticity (where variability correlates with the mean level) and is uncorrelated with the mean measurement, providing a cleaner measure of fluctuation [18].

- Formula: VIM is calculated for each lipid type and each individual as:

VIM = k × SD / mean^x- Where

xis derived from fitting the power model:SD = constant × mean^x - And

kis a scaling factor to make VIM comparable to the SD:k = mean(mean^x)[18].

- Alternative Metrics: For sensitivity analyses, variability can also be assessed using the standard deviation (SD) or coefficient of variation (CV = SD/mean) [18].

3. Statistical Analysis for Association with Outcomes:

- Categorization: Group individuals into quintiles (Q1-Q5) based on their VIM value for a given lipid, with Q5 representing the highest variability [18].

- Outcomes: Follow participants for clinical outcomes like incident myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or cardiovascular death.

- Modeling: Use Cox proportional hazards regression to investigate the association between lipid variability quintiles and the risk of incident CVD. Adjust for traditional risk factors, including baseline lipid level, sex, age, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, and lipid-lowering medication use [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and materials for conducting robust lipidomics studies focused on short-term variability.

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Enables absolute quantification of lipids; corrects for extraction efficiency and instrument variance. | Use a comprehensive mix covering major lipid classes (e.g., CE, TAG, DAG, PC, PE, SM, CER) [16]. Add to samples as early as possible in extraction. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Precursors | Tracks the incorporation of dietary components into complex lipids; studies de novo lipogenesis. | Use precursors like 13C-acetate or deuterated fatty acids in cell culture or animal models to trace metabolic flux. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pooled Plasma | Monitors instrument stability and reproducibility across batches; used for data normalization. | Create a large, homogeneous pool from an aliquot of all study samples. Analyze repeatedly throughout the analytical run [19]. |

| Structured Dietary Formulae | Provides precise control over macronutrient and fatty acid composition in intervention studies. | Macronutrient ratios (e.g., high-fat vs. high-carb) and specific fat sources (SFA, MUFA, PUFA) must be well-defined [14] [17]. |

| Automated Lipid Extraction Solvents | Isolates the lipid fraction from biological matrices like plasma or tissue. | Butanol:methanol or chloroform:methanol mixtures are common. Automated systems improve throughput and reproducibility [9] [19]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Separates complex lipid mixtures by class and species prior to mass spectrometry. | Reversed-phase (e.g., C8 or C18) columns are widely used in LC-MS for separating lipids by hydrophobicity [19]. |

| GUB03385 | GUB03385, MF:C198H322N60O52S, MW:4407 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ON1231320 | ON1231320, MF:C22H15F2N5O3S, MW:467.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Distinguishing Biological Signal from Technical Noise in Cohort Studies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main sources of variability in lipidomic cohort studies? The total variability in lipidomic measurements comes from three main sources: between-individual variance (biological differences in "usual" lipid levels among subjects), within-individual variance (temporal fluctuations in lipid levels within the same person), and technical variance (variability introduced by laboratory procedures, sample processing, and instrumentation). In serum lipidomic studies, the combination of technical and within-individual variances accounts for most of the variability in 74% of lipid species, which can significantly attenuate observed effect sizes in epidemiological studies [9].

2. What sample size is typically required for robust lipidomic cohort studies? Lipidomic studies require substantial sample sizes to detect moderate effect sizes. For a true relative risk of 3.0 (comparing upper and lower quartiles) after Bonferroni correction for testing 918 lipid species (α = 5.45×10â»âµ), studies with 500, 1,000, and 5,000 total participants (1:1 case-control ratio) would have approximately 19%, 57%, and 99% power, respectively. The required sample size depends on the specific effect sizes you expect to detect and the number of lipid species being tested [9].

3. How can I minimize technical variability during sample preparation?

- Standardize extraction protocols: Use consistent, validated extraction methods like modified Bligh & Dyer (chloroform/methanol/water), modified Folch (chloroform/methanol), MTBE (methyl tert-butyl ether/methanol/water), or BUME (butanol/methanol) methods [20]

- Implement internal standards: Add appropriate deuterated internal standards during extraction to normalize for recovery and ionization efficiency [20]

- Control pre-analytical variables: Standardize sample collection, processing, and storage conditions across all samples to minimize batch effects [9] [21]

4. Which statistical approaches best distinguish biological signals from technical noise?

- For initial analysis: Use principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize data structure and identify outliers [6]

- For group comparisons: Apply t-tests (two groups) or ANOVA (multiple groups) with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing [6]

- For classification: Employ multivariate methods like Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) or machine learning approaches (Random Forests, SVM) to handle highly correlated lipid data [6]

- For power considerations: Account for the moderate technical reliability of lipid measurements (median intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.79) when designing studies and interpreting results [9]

5. What computational tools are available for lipidomic data analysis? LipidSig provides a comprehensive web-based platform with data checking, differential expression analysis, enrichment analysis, and network visualization capabilities. Other tools include MS-DIAL for untargeted lipidomics data processing, LipidMatch for lipid identification, and MetaboAnalyst for pathway analysis [22] [6].

Quantitative Data on Lipidomic Variability

Table 1: Sources of Variance in Serum Lipidomic Measurements from the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial (n=693) [9]

| Variance Component | Proportion of Total Variance | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Between-individual variance | Varies by lipid species | Represents true biological differences between subjects; optimal for detecting associations |

| Within-individual variance | Accounts for most variability in 74% of lipids | Temporal fluctuations within individuals; can attenuate observed effect sizes |

| Technical variance | Median ICC = 0.79 | Introduced by laboratory procedures; moderate reliability across measurements |

Table 2: Statistical Power for Lipidomic Case-Control Studies Based on Variance Components [9]

| Total Sample Size | Power to Detect RR=3.0* | Practical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 500 (250 cases/250 controls) | 19% | Underpowered for most applications |

| 1,000 (500 cases/500 controls) | 57% | Moderate power for strong effects |

| 5,000 (2,500 cases/2,500 controls) | 99% | Well-powered for moderate to strong effects |

RR = Relative Risk comparing upper and lower quartiles, after Bonferroni correction for 918 tests (α = 5.45×10â»âµ)

Experimental Protocols for Minimizing Variability

Protocol 1: Standardized Sample Processing for Serum/Plasma Lipidomics

Materials:

- Serum collection tubes (SST)

- Pre-labeled cryovials for storage

- Internal standard mixture (SPLASH LipidoMix or equivalent)

- Extraction solvents (HPLC-grade methanol, methyl tert-butyl ether, water)

Procedure:

- Collect blood following standardized venipuncture procedures after consistent fasting status

- Process samples within 2 hours of collection: allow clotting (30 min), centrifuge (2000×g, 15 min, 4°C)

- Aliquot serum into cryovials, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, store at -80°C

- Thaw samples on ice immediately before extraction

- Add internal standards (normalized to protein content or fluid volume) prior to extraction [20] [9]

- Perform lipid extraction using validated methods (e.g., BUME: butanol/methanol 3:1 v/v followed by heptane/ethyl acetate 3:1 v/v with 1% acetic acid) [20]

- Evaporate organic phases under nitrogen and reconstitute in MS-compatible solvents

- Use randomized injection order with quality control samples (pooled reference samples) every 6-10 injections [9]

Protocol 2: Quality Control and Batch Effect Correction

Materials:

- Quality control (QC) samples: pooled from all study samples or commercial reference material

- Internal standards for retention time alignment

- Blank samples (extraction solvent only)

Procedure:

- Prepare QC samples identical to study samples

- Inject QC samples at beginning of sequence for system conditioning, then throughout analysis (every 6-10 samples)

- Monitor retention time drift: acceptable variation < 0.1 min over sequence

- Assess signal intensity: CV < 15-20% in QC samples for most lipid species

- Evaluate mass accuracy: < 5 ppm deviation for high-resolution instruments

- Apply batch correction algorithms (ComBat, LOESS normalization) if analyzing samples in multiple batches [6]

- Use signal filtering and noise reduction techniques to enhance data quality

- Perform systematic data quality assessment using tools like LipidQA or built-in instrument software [6]

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Minimizing Technical Variability in Lipidomics

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Lipidomic Studies with Variability Control

| Reagent/Material | Function | Variability Control Application |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated internal standards (SPLASH LipidoMix, Avanti Polar Lipids) | Quantification reference | Normalizes extraction efficiency and ionization variation; added prior to extraction [20] |

| Stable isotope-labeled lipids (e.g., D₃-16:0, ¹³C-18:0) | Method development and validation | Creates retention time databases; helps identify C=C positions in complex lipids [23] |

| Pooled reference material (NIST SRM 1950 or study-specific pools) | Quality control monitoring | Monitors technical performance across batches; identifies instrumental drift [9] |

| Standardized extraction kits (BUME, MTBE-based) | Lipid extraction | Provides consistent recovery across samples and batches; minimizes extraction bias [20] |

| Retention time markers (e.g., 1,3-dipentadecanoyl-2-oleoyl-glycerol) | Chromatographic alignment | Enables peak alignment across samples; corrects for retention time shifts [6] |

| Matrix-matched calibrators | Quantification | Compensates for matrix effects; improves accuracy of absolute quantification [21] |

Advanced Structural Resolution Protocol

Protocol 3: Determining C=C Positions in Complex Lipids

Background: Carbon-carbon double bond (C=C) positions in unsaturated complex lipids provide critical structural information but are challenging to determine with routine LC-MS/MS. Recent computational approaches now enable this without specialized instrumentation [23].

Materials:

- RAW264.7 macrophage cell line

- Stable isotope-labeled fatty acids (n-3, n-6, n-7, n-9, n-10 SIL-FAs)

- RPLC-MS/MS system with reverse-phase chromatography

- LC=CL computational tool (Lipid Data Analyzer extension)

Procedure:

- Supplement RAW264.7 cells with individual SIL-FAs for 24 hours

- Extract lipids using standardized protocols

- Analyze by RPLC-MS/MS with data-dependent acquisition

- Process data through LC=CL computational pipeline:

- Map retention times to reference database

- Use machine learning (cubic spline interpolation) for retention time alignment

- Automatically assign ω-positions based on established elution profiles

- Validate assignments using SIL-FA paired supplementation experiments [23]

Application: This approach revealed previously undetected C=C position specificity of cytosolic phospholipase Aâ‚‚ (cPLAâ‚‚), demonstrating how structural resolution can uncover novel biological insights that would be obscured by conventional lipidomics [23].

Advanced Structural Resolution Workflow

Scientific Foundation: Lipidomic Dynamics in Critical Illness

Critical illness triggers profound and dynamic alterations in the circulating lipidome, which are closely associated with patient outcomes and recovery trajectories. Research reveals that these changes are not random but follow specific temporal patterns that can inform prognostic stratification.

Key Lipidomic Patterns in Critical Illness

Table 1: Temporal Lipidomic Signatures in Critical Illness Trajectories

| Time Point | Resolving Patients (ICU <7 days) | Non-Resolving Patients (ICU ≥7 days/Late Death) | Early Non-Survivors (Death within 3 days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 hours | Moderate reduction in most lipid species | Moderate reduction in most lipid species | Severe depletion of all lipid classes |

| 24 hours | Persistent suppression of most lipids | Ongoing lipid suppression | N/A |

| 72 hours | Continued lipid suppression | Selective increase in TAG, DAG, PE, and ceramides | N/A |

| Prognostic Value | Favorable outcome | Worse outcomes | Worst outcomes |

The previously reported survival benefit of early thawed plasma administration was associated with preserved lipid levels that related to favorable changes in coagulation and inflammation biomarkers in causal modelling [24]. Phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) were elevated in patients with persistent critical illness and PE levels were prognostic for worse outcomes not only in trauma but also in severe COVID-19 patients, showing a selective rise in systemic PE as a common prognostic feature of critical illness [24].

Lipidomic Pathways in Stress Response

The metabolic response to stress in critical illness unfolds across three distinct phases: acute, subacute, and chronic [25]. These phases involve significant endocrine and immune-inflammatory responses that lead to dramatic changes in cellular and mitochondrial functions, creating what is termed "anabolic resistance" that complicates metabolic recovery.

Methodological Framework: Lipidomic Analysis in Critical Care Research

Core Analytical Workflow

Table 2: Essential Methodologies for Critical Illness Lipidomics

| Methodological Component | Technical Specifications | Application in Critical Illness |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | EDTA plasma; immediate processing or flash freezing; avoid freeze-thaw cycles | Trauma, sepsis, COVID-19 cohorts with known onset timing |

| Lipid Extraction | Modified Folch/Bligh & Dyer; MTBE; acidification for anionic lipids | High-throughput processing for critical care biobanks |

| LC-MS/MS Analysis | QTRAP platforms; C18 columns; DMS devices; polarity switching | Quantification of 800-1000+ lipid species across classes |

| Quality Control | Deuterated internal standards; pooled QC samples; batch correction | Monitoring technical variability in longitudinal studies |

| Data Processing | Peak alignment, annotation, missing value imputation, normalization | Handling heterogeneous ICU patient samples |

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) serves as the cornerstone technology for targeted lipidomic analysis in critical illness research. In comprehensive studies, this approach has enabled quantification of 996 lipids using internal standards, with quality control analysis showing a median relative standard deviation (RSD) of 4% for the lipid panel [24]. The representation typically spans 14 sub-classes, with triglyceride (TAG) being the most abundant lipid class identified in plasma, followed by phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), and diacylglycerols (DAG) [24].

Experimental Protocol: Longitudinal Lipidome Profiling in ICU Patients

Protocol: Comprehensive Lipidomic Profiling in Critical Illness

Patient Stratification and Sampling

- Enroll critically ill patients with precise onset timing (e.g., severe trauma, sepsis with known infection time)

- Collect serial blood samples at admission (0h), 24h, and 72h

- Include healthy controls for baseline reference

- Process samples immediately: centrifuge at 4°C, aliquot, store at -80°C under argon atmosphere

Lipid Extraction and Preparation

- Use modified Bligh & Dyer or MTBE-based extraction

- Add antioxidant butylhydroxytoluene (BHT) for oxidation-sensitive lipids

- Include 54 deuterated internal standards for accurate quantification

- Employ automated butanol:methanol extraction for high-throughput processing

LC-MS/MS Analysis

- Platform: SCIEX QTRAP 5500 or Q Exactive HF-X with DMS device

- Chromatography: C18 column with binary gradient (water/acetonitrile to isopropanol/acetonitrile)

- Mass detection: MRM mode for targeted analysis, m/z 100-1350

- Polarity switching: Positive and negative electrospray modes

Data Processing and Normalization

- Use XCMS, MS-DIAL, or Lipid4DAnalyzer for peak alignment

- Apply quality control filters (RSD <30% in QC samples)

- Impute missing values using k-nearest neighbors (k=10)

- Normalize to internal standards and total protein content

This protocol enables robust quantification of lipidomic signatures that align with inflammatory patterns and outcomes in critical illness [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Biological Variability in Lipidomic Studies

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can we distinguish biological signals from technical variability in longitudinal critical care lipidomics?

A: Technical variability is moderate in lipidomics, with a median intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.79 [9]. However, the combination of technical and within-individual variances accounts for most of the variability in 74% of lipid species [9]. To address this:

- Implement rigorous quality control with blinded replicate samples

- Use multiple internal standards for each lipid class

- Apply batch correction algorithms like Combat

- Ensure sample randomization during extraction and analysis

- Calculate biological variance that sums between- and within-individual variances

Q2: What are the key considerations for sample handling in critical care lipidomics?

A: Sample processing is the most vital step in lipidomic workflow [26]. Specific challenges include:

- Circadian variations: Process samples at consistent times or record collection time

- Lipid degradation: Plasma concentration of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) increases when left at room temperature [26]

- Freeze-thaw effects: Particularly problematic for sphingosine, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids [26]

- Oxidation: Major concern for polyunsaturated fatty acids; use argon atmosphere and antioxidants

Q3: How much statistical power do we need for lipidomic studies in critical illness?

A: Epidemiologic studies examining associations between lipidomic profiles and disease require large sample sizes to detect moderate effect sizes [9]. For a true relative risk of 3 (comparing upper and lower quartiles) after Bonferroni correction:

- 500 participants: 19% power

- 1,000 participants: 57% power

- 5,000 participants: 99% power Always conduct power analysis during study design and consider pooled samples or repeated measurements to enhance power.

Q4: What lipid extraction method is most suitable for critical care samples?

A: The choice depends on lipid classes of interest:

- Folch/Bligh & Dyer: Good for global lipidomics

- MTBE-based: Better for high-throughput with less emulsion formation

- Acidified butanol: Optimal for lysophosphatidic acid extraction

- SPE methods: Useful for specific lipid class enrichment

Q5: How do we validate lipidomic biomarkers for clinical application in critical care?

A: Validation requires a multi-phase approach addressing pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical challenges [21]:

- Demonstrate reproducibility across platforms and laboratories

- Validate in independent cohorts with different critical illness etiologies

- Establish standard operating procedures for sample handling

- Integrate with clinical, genomic, and proteomic data

- Assess clinical utility through decision curve analysis

Advanced Technical Challenges and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Lipidomics Challenges in Critical Care Research

| Challenge | Root Cause | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low lipid recovery | Improper extraction solvent ratio; incomplete protein precipitation | Optimize chloroform:methanol:water ratio; use acidification for anionic lipids | Validate extraction efficiency with internal standards |

| Poor chromatographic separation | Column degradation; inappropriate gradient | Replace column; optimize mobile phase composition | Use guard columns; establish QC retention time markers |

| High background noise | Solvent impurities; column bleed | Use HPLC-grade solvents; condition columns properly | Implement blank injections; use high-purity reagents |

| Lipid oxidation | Polyunsaturated fatty acid degradation; metal ion catalysis | Add antioxidants; use argon atmosphere; chelating agents | Minimize sample processing time; store under inert gas |

| Inconsistent identification | Isomer separation limitations; software misannotation | Use ion mobility; manual validation; orthogonal fragmentation | Implement multi-platform validation; reference standards |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Critical Illness Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated internal standards | Quantification reference; extraction control | Include 54 standards across 9 subclasses; add before extraction |

| Butylhydroxytoluene (BHT) | Antioxidant protection | 0.1-0.01% in extraction solvents; prevents PUFA oxidation |

| Ammonium formate/acetate | Mobile phase additive; promotes ionization | 10 mM in water/acetonitrile and isopropanol/acetonitrile |

| Chloroform-methanol mixtures | Lipid extraction solvents | Folch (2:1) or Bligh & Dyer (1:2:0.8) ratios; toxic handling required |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether | Alternative extraction solvent | Less toxic; forms distinct upper organic phase |

| C18 chromatography columns | Lipid separation | 100-150mm length, 1.7-2.1μm particle size; 55°C temperature |

| Quality control plasma pools | Process monitoring | Create from leftover patient samples; run every 6-10 injections |

| Solid-phase extraction cartridges | Lipid class enrichment | Useful for phosphoinositides, sphingolipids, or oxylipins |

| Pyrimidyn 7 | Pyrimidyn 7, MF:C21H41N5, MW:363.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GNE 2861 | GNE 2861, MF:C22H26N6O2, MW:406.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Lipid-Immune Signaling Networks in Critical Illness

The integration of lipidomic data with immune parameters reveals critical networks in sepsis and critical illness. Studies demonstrate that phosphatidylcholine (PC) levels correlate with monocytes, while cholesteryl ester (CE) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) associate with complement proteins and CD8+ T cells [27]. These lipid-immune relationships differ significantly between younger and elderly patients, suggesting distinct pathophysiological mechanisms across age groups [27].

Risk stratification models incorporating six key lipids (LPC(19:0), PC(P-19:0), SM 32:3;2O(FA 16:3), PC(P-20:0), PC(O-18:1/20:3), CE(15:0)) and age have demonstrated accurate prediction of septic shock (AUC: 0.87 training, 0.82 validation) and mortality risk in elderly patients [27]. This highlights the translational potential of lipidomic signatures in critical care settings.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Capturing Lipid Dynamics

Lipidomics provides critical insight into metabolic changes in health and disease, but traditional methods face challenges in sensitivity, lipid coverage, and annotation accuracy [28]. The integration of C30 reversed-phase chromatography with scheduled data-dependent acquisition (SDDA) addresses these limitations by significantly improving chromatographic separation and data acquisition efficiency.

Core Technological Advantages

- Enhanced Lipid Annotation: SDDA demonstrates a 2-fold increase in the number of lipids annotated compared to conventional DDA, with a 2-fold higher annotation confidence (Grade A and B) [28].

- Superior Separation: C30 stationary phases provide improved separation of complex lipid mixtures compared to traditional C18 columns, particularly for lipid isomers and isobaric species.

- Acquisition Efficiency: SDDA optimizes instrument time by triggering MS/MS scans only when precursors are eluting, increasing identification rates without compromising data quality.

Method Performance Across Matrices

The C30-SDDA method has been rigorously validated across clinical blood matrices, with performance characteristics summarized below:

Table 1: C30-SDDA Performance Across Blood Matrices

| Matrix Type | Number of Lipids Annotated | Repeatability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | >2000 lipid species | Highest | Primary for clinical diagnostics |

| EDTA-Plasma | Comprehensive coverage | High | Epidemiological studies |

| Dried Blood Spots (DBS) | Substantial coverage | Robust | Biobanking, remote sampling |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Chromatographic Issues

Problem: Peak broadening and reduced resolution in C30 separation

- Solution: Ensure proper column conditioning with gradual solvent transition; use longer gradient times for complex samples; maintain column temperature consistency (±2°C)

- Preventive measures: Implement guard columns, filter samples (0.2μm), and avoid pH extremes outside 2-8 range

Problem: Retention time drift affecting SDDA scheduling

- Solution: Implement robust system suitability tests using internal retention time markers; extend column equilibration time between runs; monitor pressure trends for early detection of column degradation

- Advanced tuning: Use quality control samples to update retention time windows in SDDA methods periodically

Mass Spectrometry Acquisition Problems

Problem: Insufficient MS/MS triggering in crowded chromatographic regions

- Solution: Adjust SDDA parameters to include dynamic exclusion with shorter durations; increase MS1 resolution for better precursor selection; implement intensity-based triggering thresholds

- Parameter optimization: Set maximum injection time to balance sensitivity and scan speed; use apex-triggering for optimal fragmentation spectra

Problem: Spectral quality issues affecting lipid identification

- Solution: Optimize collision energies based on lipid class; use lipid-class specific fragmentation rules; implement stepped collision energy for comprehensive fragmentation patterns

- Quality metrics: Monitor precursor isolation efficiency (>80%); ensure fragment ion accuracy (<5ppm)

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation for Blood Matrices

Serum/Plasma Lipid Extraction (Based on [28])

- Sample Volume: Use 10-50μL of serum or plasma per extraction

- Protein Precipitation: Add 500μL cold methanol, vortex 30 seconds, incubate at -20°C for 1 hour

- Lipid Extraction: Add 500μL methyl-tert-butyl ether, vortex 1 minute, sonicate 15 minutes

- Phase Separation: Add 125μL water, centrifuge at 14,000×g for 15 minutes

- Collection: Transfer upper organic phase to new tube, evaporate under nitrogen

- Reconstitution: Resuspend in 100μL 2-propanol/acetonitrile (60:40, v/v) for LC-MS analysis

Quality Control Measures:

- Include pooled quality control samples every 6-10 injections [3]

- Use internal standards covering major lipid classes for normalization

- Monitor extraction efficiency through reference materials

LC-MS Method Parameters

C30 Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C30 reversed-phase (150×2.1mm, 2.6μm)

- Temperature: 45°C

- Flow Rate: 0.4 mL/min

- Mobile Phase A: acetonitrile/water (60:40) with 10mM ammonium formate

- Mobile Phase B: 2-propanol/acetonitrile (90:10) with 10mM ammonium formate

- Gradient: 30-100% B over 60 minutes, 5-minute wash at 100% B, 10-minute re-equilibration

- Injection Volume: 5μL

SDDA Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- MS1 Resolution: 120,000 @ m/z 200

- Scan Range: m/z 200-2000

- MS2 Resolution: 30,000 @ m/z 200

- Isolation Window: 1.2 m/z

- Maximum Injection Time: 100ms (MS1), 50ms (MS2)

- Collision Energies: Stepped 20, 30, 40eV

- Scheduling Window: ±1.5 minutes based on retention time

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflow

Figure 1: C30-SDDA Lipidomics Workflow from Sample to Biological Interpretation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for C30-SDDA Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| C30 UHPLC Column | Superior separation of lipid isomers | 150×2.1mm, 2.6μm particle size |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive for improved ionization | LC-MS grade, 10mM concentration |

| MTBE | Lipid extraction solvent | High purity, low peroxide levels |

| Internal Standard Mix | Quantification normalization | SPLASH LipidoMix or equivalent |

| NIST Plasma SRM 1950 | Quality control and method validation | Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma |

| Acetonitrile (LC-MS) | Mobile phase component | Optima LC/MS grade or equivalent |

| 2-Propanol (LC-MS) | Strong elution solvent | Optima LC/MS grade or equivalent |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does C30 chromatography provide better lipid separation than C18?

A: C30 stationary phases have higher hydrophobicity and greater shape selectivity, particularly beneficial for separating lipid isomers and isobaric species that co-elute on C18 columns. The longer alkyl chains provide enhanced retention and resolution of complex lipid mixtures.

Q: How does SDDA improve upon conventional DDA in lipidomics?

A: SDDA increases identification rates by 2-fold compared to conventional DDA by triggering MS/MS acquisition only when precursors are expected to elute, reducing redundant sequencing and increasing coverage of lower-abundance species [28].

Q: What is the evidence for addressing biological variability using this method?

A: Large-scale studies applying quantitative LC-MS/MS lipidomics to population cohorts have demonstrated that biological variability significantly exceeds analytical variability, with high individuality and sex specificity observed in circulatory lipidomes [3]. The robustness of C30-SDDA across batches (median reproducibility 8.5%) makes it suitable for detecting true biological variation.

Q: Can this method be applied to single-cell lipidomics?

A: While the current protocol is optimized for bulk analysis, the sensitivity enhancements of SDDA provide a foundation for adapting to single-cell applications. Emerging technologies in mass spectrometry are pushing sensitivity limits to enable single-cell lipid profiling [5].

Q: What are the key quality control measures for implementing this method?

A: Essential QC includes: regular analysis of reference materials (e.g., NIST plasma), monitoring retention time stability, evaluating peak shape and intensity, tracking internal standard performance, and assessing batch-to-batch reproducibility with quality control pools.

Lipids are fundamental biomolecules that serve as structural components of cell membranes, function as energy storage units, and play crucial roles in cellular signaling processes [29]. Consequently, dysregulated lipid metabolism is closely correlated with the occurrence and progression of pathological conditions, including diabetes, cancers, and neurodegenerative diseases [29]. However, a significant portion of the lipidome remains "dark" or "unmapped" due to analytical challenges in resolving structural isomers [29]. The structural complexity of lipids arises from variations in class, headgroup, fatty acyl chain composition, sn-position, and carbon-carbon double bond (C=C) location and geometry [30] [31]. In particular, C=C location isomers confer distinct biological functions and physical properties to lipids, yet they remain exceptionally challenging to characterize using conventional mass spectrometry approaches [29] [32].

Traditional collision-induced dissociation (CID) in tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fails to generate diagnostic fragment ions for pinpointing C=C locations because cleavage of non-polar C–C bonds adjacent to a C=C bond is not favored [29]. This limitation represents a critical gap in lipidomic studies, especially when investigating biological variability where isomeric ratios may change in response to physiological or pathological stimuli [15]. The Paternò-Büchi (P-B) reaction has emerged as a powerful derivatization strategy that enables precise localization of C=C bonds in unsaturated lipids when coupled with MS/MS analysis [29] [30]. This technical support guide provides comprehensive troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers implementing P-B reactions in lipidomic studies, with particular emphasis on addressing biological variability in lipid isomer research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of P-B reactions for lipid isomer analysis requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The table below summarizes key components and their functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for P-B Reaction Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PB Reagents | Forms oxetane ring with C=C bonds via [2+2] photocycloaddition | Acetone (58 Da mass shift) [30], Benzophenone [29], 2-Acetylpyridine (2-AP) [29], 2′,4′,6′-Trifluoroacetophenone (triFAP) [29], Methyl Benzoylformate (MBF) with photocatalyst for visible-light activation [32] |

| Photocatalysts | Enables visible-light activation via triplet-energy transfer | Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (triplet energy ~60.1 kcal/mol) for use with MBF [32] |

| Light Sources | Activates carbonyl compounds to excited state | UV lamps (254 nm for aliphatic carbonyls) [33] [34], Visible light systems for photocatalytic approaches [32], Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) [35] |

| Reaction Vessels | Container for photochemical reaction | Quartz cuvettes (transparent to UV) [29], Gas-tight round bottom flasks (prevent oxygen leakage) [29], Microreactors for online setups [29] |

| MS-Compatible Solvents | Medium for reaction and MS analysis | Acetonitrile, Methanol, Chloroform; Must be UV-transparent and minimize side reactions [29] |

| Internal Standards | Quality control and quantification | Deuterated lipid standards (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX) [36] |

| Vilobelimab | Vilobelimab, CAS:2250440-41-4, MF:C43H60O6, MW:672.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TJ-M2010-5 | TJ-M2010-5, CAS:1357471-57-8, MF:C23H26N4OS, MW:406.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for P-B Reaction in Lipidomics

Online RPLC-PB-MS/MS for Triacylglycerol Analysis

Objective: To separate and characterize triacylglycerol (TG) species from human plasma with confident C=C location assignment [37].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Extract lipids from human plasma using modified Folch method with chloroform:methanol (2:1 v/v) supplemented with 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) to prevent oxidation [36].

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Column: Reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 50 × 0.3 mm, 3 μm particles)

- Mobile Phase: A: 60:40 acetonitrile/water; B: 85:10:5 isopropanol/water/acetonitrile, both with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient: 0-0.5 min (40% B), 0.5-5 min (99% B), 5-10 min (99% B), 10-12.5 min (40% B), 12.5-15 min (40% B)

- Flow Rate: 8 μL/min [37] [36]

- Online P-B Derivatization:

- Mix acetone (10% v/v) with column effluent via T-connector

- Use UV photochemical reactor (254 nm) with knitted polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) reactor coil

- Maintain reaction temperature at 20°C [37]

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Ionization: ESI in positive mode

- MS/MS: Select PB-modified lipids (original mass + 58 Da for acetone) for CID

- Identification: Look for diagnostic pair fragments (difference of 26 Da) indicating C=C location

- Limit of Identification: 50 nM [37]

Visible-Light Activated PCPI for Dual-Resolving of C=C Isomers

Objective: To simultaneously resolve both positional and geometric isomers of C=C bonds in bacterial and mouse brain lipids [32].

Protocol:

- Reaction System Setup:

- Carbonyl Substrate: Methyl benzoylformate (MBF, 10 mM)

- Photocatalyst: Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6 (0.5 mol%)

- Solvent: Acetonitrile

- Light Source: 455 nm blue LED lamp [32]

- Reaction Conditions:

- Incubate lipid extracts with reaction system for 10 minutes under light irradiation

- Maintain inert atmosphere with argon or nitrogen to prevent side reactions

- For offline derivatization, use quartz cuvettes as reaction vessels [32]

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Use reversed-phase LC with C18 column for separation

- Employ high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF) for detection

- Monitor both oxetane products (for C=C location) and isomerized lipids (for cis/trans configuration) [32]

- Data Interpretation:

- Positional Isomers: Identify via diagnostic fragments from oxetane ring cleavage in MS/MS

- Geometric Isomers: Determine by comparing LC patterns before and after photoisomerization; cis isomers show decreased peak areas while trans isomers increase [32]

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for P-B Reaction in Lipidomics

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Low Reaction Yield or Efficiency

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low P-B Reaction Efficiency

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete derivatization | Insufficient UV light intensity or inappropriate wavelength | Use quartz vessels for UV transparency at 254 nm; Ensure proper light source alignment; Consider visible-light photocatalytic system for improved efficiency [32] |

| Low product formation | Oxygen quenching of excited states | Degas solvents with argon/nitrogen; Use gas-tight reaction vessels; Maintain inert atmosphere throughout reaction [29] |

| Side reactions predominant | Prolonged reaction time or inappropriate solvent | Optimize reaction time (typically seconds to minutes in flow systems); Use non-polar solvents when possible; Test different PB reagents (acetone, benzophenone derivatives) [29] [34] |

| Poor MS response of products | Ionization suppression or inefficient fragmentation | Incorporate nanoESI for improved sensitivity; For free fatty acids, use double derivatization (PB reaction + carboxyl group labeling with DEEA) [30] |

Quantitative and Reproducibility Issues

Challenge: Inconsistent quantification of isomer ratios across batches or platforms.

Solutions:

- Internal Standards: Use deuterated lipid internal standards (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX) added at the beginning of extraction to correct for technical variability [36].

- Quality Control Samples: Implement pooled quality control (QC) samples analyzed throughout the batch to monitor and correct for instrumental drift [15].

- Platform Validation: Validate identifications across both positive and negative LC-MS modes to reduce false positives caused by co-elution [36].

- Manual Curation: Manually inspect spectral outputs and software identifications; use data-driven outlier detection to flag potential misidentifications [36].

- Control Reaction Parameters: Standardize light intensity, reaction time, temperature, and PB reagent concentration across all samples [29].

Biological Sample-Specific Challenges

Challenge: Addressing biological variability while minimizing technical artifacts.

Solutions:

- Pre-analytical Standardization:

- Batch Design:

- Data Normalization:

Figure 2: Troubleshooting Common P-B Reaction Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the principle behind the Paternò-Büchi reaction for lipid C=C location analysis?

The P-B reaction is a photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition between an excited carbonyl compound (e.g., acetone) and a C=C bond in an unsaturated lipid, forming an oxetane ring. When this modified lipid is fragmented in MS/MS, the oxetane ring cleaves to produce a pair of diagnostic ions with a specific mass difference (e.g., 26 Da for acetone), which reveals the original location of the C=C bond in the fatty acyl chain [29] [30].

Q2: How can I minimize side reactions during P-B derivatization?

Key strategies include: (1) Using degassed solvents and maintaining an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation; (2) Optimizing reaction time to avoid over-exposure to UV light; (3) Selecting appropriate PB reagents - aliphatic carbonyls like acetone generally produce fewer side products than aromatic carbonyls; (4) Implementing microreactors or flow systems to precisely control reaction parameters and minimize side product formation [29].

Q3: Can the P-B reaction distinguish between cis and trans geometric isomers?

Standard P-B reactions show limited capability for distinguishing cis/trans isomers. However, the recently developed photocycloaddition-photoisomerization (PCPI) reaction system using methyl benzoylformate with a photocatalyst under visible light can simultaneously resolve both C=C positions and geometric configurations. This system induces cis to trans isomerization, allowing identification by comparing LC patterns before and after the reaction [32].

Q4: What is the sensitivity and dynamic range of PB-MS/MS for lipid isomer analysis?

PB-MS/MS offers high sensitivity (sub-nM to nM detection limits) and a linear dynamic range spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude for profiling C=C location isomers. The limit of identification for triacylglycerol species in human plasma using online RPLC-PB-MS/MS is approximately 50 nM [29] [37].

Q5: How reproducible are lipid isomer ratio measurements using PB-MS/MS, and how does this help with biological variability studies?

The technique shows high precision with approximately 5% RSD for technical replicates. By measuring isomeric ratios rather than absolute abundances, the method further diminishes RSD from biological replicates, making it particularly valuable for detecting subtle but biologically relevant changes in isomer distributions in disease states [29].

Q6: What software tools are available for processing PB-MS/MS data, and how consistent are their results?

Common lipidomics software includes MS DIAL and Lipostar. However, studies show only 14.0% identification agreement between platforms using default settings with MS1 data, improving to 36.1% with MS2 spectra. This highlights the critical importance of manual curation and validation across multiple platforms and ionization modes to ensure reproducible lipid identifications [36].

The Paternò-Büchi reaction represents a powerful analytical tool that significantly advances our capability to resolve lipid C=C location isomers in complex biological systems. When properly implemented with appropriate troubleshooting and quality control measures, this methodology enables researchers to uncover previously inaccessible dimensions of lipid structural diversity. By integrating robust experimental protocols with careful consideration of biological variability sources, researchers can reliably apply PB-MS/MS to investigate lipid isomer dynamics in health and disease, ultimately contributing to more comprehensive lipidomic phenotyping and biomarker discovery.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Pre-analytical Errors and Corrective Actions

| Error Category | Specific Issue | Impact on Lipidomics Data | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Incorrect collection tube (e.g., wrong anticoagulant) | Alters lipid classes; e.g., EDTA tubes affect lysophospholipids [38] | Standardize on K3EDTA tubes for plasma and validate tube type for your lipid panel [38] |

| Non-fasting state of participant | Introduces significant variability in triglyceride-rich lipids [15] | Implement strict fasting protocols (typically 10-12 hours) prior to blood collection [15] | |

| Hemolysis due to improper technique | Rupture of red blood cells releases lipids and interferes with accurate measurement | Train phlebotomists on proper technique; avoid excessive suction [39] | |

| Sample Handling & Storage | Intermediate storage at incorrect temperature | Degradation of unstable lipids (e.g., lipid mediators, lysophospholipids) [38] | Place plasma samples in ice water immediately after collection and freeze at -80°C within 2 hours [38] |

| Delayed processing of whole blood | Increased ex vivo generation of lysophospholipids and oxidation of fatty acids [40] | Process plasma (centrifugation, aliquoting) within 1-2 hours of draw [38] | |

| Improper long-term storage temperature | Lipid degradation over time, leading to inaccurate concentrations | Store samples at -70°C to -80°C; monitor freezer stability and avoid freeze-thaw cycles [9] [15] | |

| Sample Identification | Mislabeled specimen | Incorrect data attribution, rendering results useless and harmful | Label specimens at the patient's bedside using at least two unique identifiers [41] |

| Incomplete labeling on tube or form | Specimen rejection by laboratory, causing delays | Use barcoding systems where available and verify details against request form [41] |

Table 2: Statistical Implications of Pre-analytical Variability

| Variance Component | Description | Proportion of Total Variance (Median, from [9]) | Impact on Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Variance | Variability from laboratory procedures (e.g., analysis, processing) | Moderate (Median ICCTech = 0.79) [9] | High technical reliability reduces attenuation of observed effect sizes. |

| Within-Individual Variance | Biological variability over time within a single person | High (Combined with technical variance, accounts for most variability in 74% of lipids) [9] | A single measurement may poorly represent the "usual" lipid level, requiring larger sample sizes. |

| Between-Individual Variance | Variability of "usual" lipid levels among different subjects | Lower than other sources for many lipids [9] | This is the key variance for detecting associations; high between-individual variance is ideal. |

| Statistical Power Implication | For a true RR=3 with 500/1000/5000 total participants, power is only 19%/57%/99%, respectively [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is standardizing pre-analytical protocols so critical in lipidomics research?

Pre-analytical sample handling has a major effect on the suitability of metabolites and lipids as biomarkers [38]. Errors introduced during collection, handling, and storage can lead to ex vivo distortions of lipid concentrations, meaning the measured levels do not reflect the true biological state [38]. Since most laboratory errors (61.9%-68.2%) occur in the pre-analytical phase [39], standardizing these protocols is the most effective way to ensure data reliability and quality.

2. What are the most unstable lipids, and how should they be handled?

Lipid mediators and certain lysophospholipids are particularly prone to rapid ex vivo generation or degradation [38] [40]. For these unstable analytes, meticulous processing is required. Recommendations include using ice-cold storage immediately after draw and adding enzyme inhibitors like 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT) to prevent oxidation during sample preparation [38] [15].

3. How does biological variability affect my lipidomics study's power, and how can I mitigate it?

Lipid levels are dynamic and influenced by factors like diet, circadian rhythm, and exercise [9] [15]. The combination of within-individual biological variability and technical variability accounts for most of the total variability for the majority of lipid species [9]. This "noise" attenuates the observed associations between lipids and diseases, drastically reducing statistical power. To mitigate this, use large sample sizes and, where feasible, collect multiple serial samples from participants to better estimate their "usual" lipid level [9].

4. What is "unwanted variation" (UV) in lipidomics, and how is it removed?

Unwanted Variation (UV) is any variation introduced into the data not due to the biological factors under study [15]. This includes variation from pre-analytical factors, analytical platforms, and data processing. The best strategy is to control for UV proactively through careful study design and standardized protocols [15]. Post-analytically, UV can be addressed using global normalization methods (e.g., SERRF, RUV-III) that leverage quality control samples run in each batch to correct for technical drift [15].

5. What are the minimum reporting standards for lipidomics data in publications?

To ensure reproducibility and data quality, journals are increasingly requiring detailed reporting. You should document:

- Sample Collection: Patient fasting status, blood draw tube, processing times and temperatures [40].

- Sample Storage: Long-term storage temperature and duration [40].

- Lipid Extraction: Exact protocol used (e.g., Folch, MTBE, BUME) [40].

- MS Analysis: Platform, identification strategies, and quantification methods (absolute is the "gold standard") [40].

- Data Processing: Software used and how missing values were handled [40].

Essential Workflow Diagrams

Pre-analytical Workflow for Plasma Lipidomics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Pre-analytical Standardization

| Item | Function in Lipidomics | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| K3EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Standard anticoagulant for plasma preparation. Prevents coagulation while minimizing ex vivo lipid alterations [38]. | Preferred over serum for many lipidomic applications due to more controlled and rapid processing [38]. |

| BHT (2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol) | Antioxidant added during sample preparation to inhibit lipid peroxidation and protect unsaturated fatty acids [38] [15]. | Critical for stabilizing oxidation-prone lipids. Concentration should be optimized and standardized across batches. |

| Deuterated Internal Standards (ISTDs) | Added to the sample before extraction to correct for losses during preparation and variability during MS analysis [9] [40]. | Should be selected to cover a broad range of lipid classes. Essential for accurate absolute quantification [40]. |

| MTBE or Chloroform/Methanol | Organic solvents for liquid-liquid extraction of lipids from plasma/serum (e.g., MTBE, Folch, or BUME methods) [15] [40]. | Different solvents have varying extraction efficiencies for different lipid classes. The chosen method must be consistent [40]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pooled Plasma | A homogeneous sample from multiple donors, aliquoted and analyzed repeatedly throughout the analytical batch [9] [15]. | Used to monitor instrument performance, correct for batch effects, and perform post-acquisition normalization (e.g., with SERRF) [15]. |

| Gintemetostat | Gintemetostat, CAS:2604513-16-6, MF:C25H26F4N8O2, MW:546.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| taccalonolide AJ | taccalonolide AJ, MF:C34H44O14, MW:676.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting High-Throughput Lipidomics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the typical number of lipids identified in different sample types, and why does it vary? The number of lipids identified depends heavily on the sample type, volume, and analysis mode. For instance, 1 million yeast cells or 80µL of human plasma extract can yield between 100 to 1000 lipids. The ion mode (positive or negative) also significantly impacts the results. In LC-MS/MS runs, the number of MS2 spectra acquired can range from 5,000 to over 10,000 in a 30-minute Top N experiment, directly influencing the number of lipid species identified and integrated [42].

How can I determine double bond position in lipids using high-throughput platforms? Routine MS-MS analysis alone cannot determine double bond position. This requires additional methodologies, such as:

- Using lipid standards to model retention time and identify likely candidates.

- Employing separate methods like hydrolysis followed by GC-MS.

- Implementing ion-molecule reactions (e.g., ozone-induced dissociation) or UVPD (photodissociation) [42].

Can I use direct infusion for complex lipid mixtures, and what are the drawbacks? While LipidSearch software supports identification from direct infusion (dd-MS2) data, it is not recommended for complex mixtures. Co-isolation of multiple precursor ions or isomers at the same m/z leads to mixed MS2 spectra, which reduces identification accuracy and typically results in a lower number of confidently identified species compared to LC-MS methods [42].