Navigating the Reproducibility Crisis in Lipidomic Biomarker Validation: From Foundational Challenges to Clinical Translation

Lipidomics has emerged as a powerful tool for discovering biomarkers that reflect real-time metabolic states in diseases ranging from cancer to inflammatory disorders.

Navigating the Reproducibility Crisis in Lipidomic Biomarker Validation: From Foundational Challenges to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Lipidomics has emerged as a powerful tool for discovering biomarkers that reflect real-time metabolic states in diseases ranging from cancer to inflammatory disorders. However, the translation of these discoveries into clinically validated diagnostics faces significant reproducibility challenges. This article explores the entire lipidomic biomarker pipeline, from foundational principles and methodological approaches in mass spectrometry to the critical troubleshooting of analytical variability and the rigorous validation required for clinical adoption. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current evidence on the sources of irreproducibility—including software discrepancies, pre-analytical variables, and a lack of standardized protocols—while highlighting advanced solutions such as machine learning and standardized workflows that are paving the way for more robust, clinically applicable lipidomic biomarkers.

The Promise and Peril of Lipidomic Biomarkers: Understanding the Fundamental Landscape

Lipids, once considered merely as passive structural components of cellular membranes, are now recognized as dynamic bioactive molecules that play critical roles in cellular signaling, metabolic regulation, and disease pathogenesis. The emergence of lipidomics—the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks—has revealed the astonishing complexity of lipid-mediated processes, with thousands of distinct lipid species participating in sophisticated signaling cascades [1] [2].

This paradigm shift underscores lipids as active participants in health and disease, functioning as signaling hubs that regulate inflammation, metabolism, and immune responses [3] [2]. Understanding these dynamic roles is particularly crucial for advancing biomarker discovery and therapeutic development, though it presents significant challenges in validation and reproducibility that this technical support center aims to address.

Core Concepts: Lipid Signaling in Cellular Communication

Lipid Rafts as Signaling Platforms

What are lipid rafts? Lipid rafts are specialized, cholesterol- and sphingolipid-enriched microdomains within cellular membranes that create more ordered and less fluid environments than the surrounding membrane [4]. These dynamic structures serve as organizing platforms for signaling complexes and facilitate crucial cellular processes.

Table 1: Key Components of Lipid Rafts and Their Functions

| Component | Primary Function | Signaling Role |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | Regulates membrane fluidity and stability | Maintains platform integrity for signaling assembly |

| Sphingolipids | Ensures tight packing and structural integrity | Forms ordered domains for receptor clustering |

| Gangliosides | Modulates cell signaling and adhesion | Serves as raft markers and signaling modulators |

| GPI-Anchored Proteins | Facilitates immune cell signaling | Links extracellular stimuli to intracellular responses |

| Transmembrane Proteins | Enables precise control of signaling events | Includes growth factor receptors and ion channels |

Lipid rafts are not static structures but exhibit dynamic fluidity within the fluid mosaic model of the cell membrane. Their ability to cluster or coalesce into larger domains in response to stimuli significantly influences cellular processes, including signal transduction and membrane trafficking [4]. For example, during immune activation, T-cell receptors accumulate in lipid rafts upon antigen binding, facilitating downstream signaling events essential for immune responses.

Bioactive Lipid Signaling in Immune Regulation

Lipids function as potent signaling molecules that regulate immune cell function and polarization. Macrophages, in particular, exhibit distinct lipid-driven metabolic reprogramming during polarization between pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 states [3].

M1 Macrophage Lipid Signaling:

- Increased glycolytic flux with glucose-6P diversion to pentose phosphate pathway for NADPH and ROS production

- Disruptions in TCA cycle leading to mitochondrial export of citrate and succinate

- Citrate conversion to acetyl-CoA for synthesis of acyl-CoA and phospholipids

- Free arachidonic acid release from phospholipids serving as substrate for pro-inflammatory eicosanoids [3]

M2 Macrophage Lipid Signaling:

- Dependence on oxidative phosphorylation with intact TCA cycle

- Functional glycolytic pathways supporting alternative activation

- CD36-mediated endocytosis of modified LDLs for membrane remodeling and energy production [3]

Figure 1: Lipid Raft Organization and Signaling Function. Lipid rafts serve as platforms that concentrate specific lipids and proteins to facilitate efficient signaling cascades.

Methodologies: Lipidomics Workflows and Protocols

Untargeted Lipidomics: LC-MS Workflow

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) has become the analytical tool of choice for untargeted lipidomics due to its high sensitivity, convenient sample preparation, and broad coverage of lipid species [5].

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Homogenization: Homogenize tissue samples or aliquot biological liquids

- Standard Addition: Add isotope-labeled internal standards as early as possible to enable normalization

- Stratified Randomization: Randomize samples in batches of 48-96 samples

- Blank Insertion: Insert blank extraction samples after every 23rd sample

- Lipid Extraction: Perform extraction in predetermined batches

- Centrifugation: Separate organic and aqueous phases by centrifugation

- Quality Control: Prepare QC samples by collecting aliquots from each sample into a pooled sample [5]

LC-MS Analysis Parameters:

- Chromatography: Reversed-Phase Bridged Ethyl Hybrid (BEH) C8 column

- Mass Detection: High-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF instruments)

- Ionization Modes: Both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes

- QC Placement: Inject QC samples several times before initiating run, after each batch, and after completion [5]

Data Processing and Analysis

Data Conversion and Import:

- Convert centroid data to conventional mzXML format using ProteoWizard

- Organize files into folder structure reflecting study design

- Import into R environment using xcms Bioconductor package

- Group samples based on subfolder structure for peak alignment [5]

Statistical Analysis Framework:

- Univariate Methods: Student's t-test, ANOVA for analyzing lipid features independently

- Multivariate Methods: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify relationship patterns

- Peak Alignment: Match MS peaks with similar m/z and retention times across samples [6]

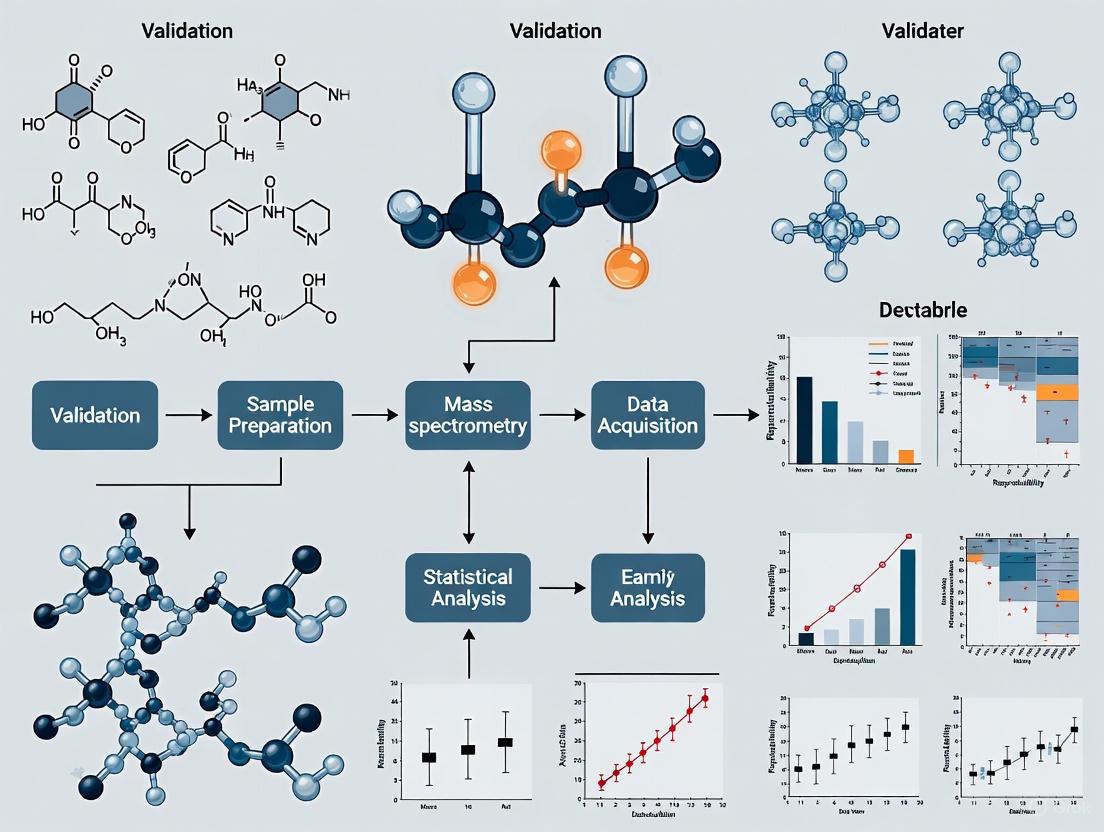

Figure 2: Untargeted Lipidomics Workflow. The comprehensive process from sample preparation to lipid identification ensures broad coverage of lipid species.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Lipidomics Research

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization for experimental biases | Add early in sample preparation; select based on lipid classes of interest |

| C8 or C18 Reversed-Phase Columns | Chromatographic separation of lipids | Provides optimal separation for diverse lipid classes |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Monitor instrument stability and reproducibility | Prepare from pooled sample aliquots; inject throughout sequence |

| ProteoWizard Software | Convert MS data to mzXML format | Cross-platform tool for data standardization |

| xcms Bioconductor Package | Peak detection and alignment | Most widely used solution for MS data analysis |

| Lipid Maps Database | Lipid identification and classification | International standard for lipid nomenclature |

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Challenges

Biomarker Validation and Reproducibility

Issue: Low reproducibility across lipidomics platforms Problem: Different lipidomics platforms yield divergent outcomes from the same data, with agreement rates as low as 14-36% during validation [1].

Solutions:

- Standardize Pre-analytical Protocols:

- Implement consistent sample collection and processing procedures

- Use identical extraction buffers across comparisons

- Maintain consistent storage conditions (-80°C)

Harmonize Analytical Parameters:

- Standardize LC gradients and mobile phase compositions

- Calibrate mass spectrometers using reference standards

- Implement uniform data quality thresholds

Validate with Multiple Methods:

- Confirm identifications using MS/MS fragmentation patterns

- Cross-validate with orthogonal methods when possible

- Utilize shared reference materials for inter-laboratory comparisons

Issue: Batch effects in large-scale studies Problem: LC-MS batch effects persist even after normalization, confounding biological signals [5].

Solutions:

- Strategic Batch Design:

- Distribute samples among batches to enable within-batch comparisons

- Avoid confounding factors of interest with batch covariates

- Balance confounding factors between samples and controls

Quality Control Integration:

- Insert QC samples after every 10 experimental samples

- Inject blank samples at beginning and end of runs

- Monitor instrument stability through retention time drift

Advanced Normalization:

- Use internal standards for retention time correction

- Apply quality control-based robust spline correction

- Implement batch effect correction algorithms (ComBat, ARSyN)

Structural Characterization Challenges

Issue: Incomplete structural elucidation Problem: Typical high resolution and MS2 may be insufficient for complete structural characterization, particularly for lipid isomers [6].

Solutions:

- Advanced Fragmentation Techniques:

- Implement both HCD and CID fragmentation in tandem

- Utilize MS³ capabilities for complex isomers

- Combine positive and negative ion mode data

Chromatographic Optimization:

- Employ C30 reversed-phase columns for enhanced separation

- Optimize mobile phase modifiers for specific lipid classes

- Extend chromatographic gradients for complex mixtures

Complementary Techniques:

- Utilize chemical derivatization for double bond localization

- Incorporate ion mobility separation for isobaric species

- Apply 2D NMR for unequivocal structural assignment

FAQs: Lipidomics in Biomarker Research

Q1: What are the major challenges in translating lipidomic biomarkers to clinical practice?

A: The transition from research findings to approved lipid-based diagnostic tools faces several hurdles:

- Validation Complexity: Lipid changes are frequently subtle and context-dependent, requiring integration with clinical, genomic, and proteomic data [1]

- Regulatory Gaps: Incomplete regulatory frameworks for lipidomic biomarkers and lack of multi-center validation studies hinder clinical adoption [1]

- Standardization Issues: Biological variability, lipid structural diversity, and inconsistent sample processing exacerbate reproducibility problems [1] [2]

- Technical Limitations: Current platforms struggle with complete structural elucidation, particularly for lipid isomers and low-abundance species [6]

Q2: How can researchers improve reproducibility in lipid raft studies?

A: Enhancing reproducibility in lipid raft research requires:

- Cholesterol Modulation Controls: Include methyl-β-cyclodextrin treatments as positive controls for raft disruption

- Cross-Validation Methods: Combine multiple assessment techniques (e.g., detergent resistance, microscopy, functional assays)

- Standardized Isolation Protocols: Implement consistent detergent concentrations and centrifugation conditions

- Compositional Analysis: Regularly quantify cholesterol-to-phospholipid ratios in isolated raft fractions

Q3: What computational approaches are available for lipid nanoparticle design?

A: Computational methods are increasingly valuable for LNP optimization:

- Physics-Based Modeling: All-atom and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations capture lipid-RNA interactions and endosomal escape mechanisms [7]

- Constant pH Models: Scalable CpHMD models accurately reproduce apparent pKa values for different LNP formulations [7]

- Machine Learning: ML-driven approaches uncover complex patterns in LNP formulation and performance, though they require high-quality experimental datasets for training [7]

- Multiscale Frameworks: Integrative computational strategies bridge molecular properties with therapeutic efficacy across different length scales [7]

Q4: How do glycerophospholipid alterations contribute to neurodegenerative diseases?

A: Glycerophospholipids play active roles in neurodegeneration:

- Metabolic Dysregulation: In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), glycerophospholipid alterations appear before motor symptom onset, suggesting early pathogenic involvement [8]

- Structural Consequences: Changes in glycerophospholipid composition affect membrane fluidity, protein function, and organelle integrity in neuronal tissues [8]

- Signaling Disruption: As precursors for bioactive lipids, glycerophospholipid imbalances perturb inflammatory signaling and cellular communication [8]

- Diagnostic Potential: Glycerophospholipid profiles in cerebrospinal fluid and blood show promise as biomarkers for early diagnosis and progression monitoring [8]

Lipidomics, a rapidly growing field of systems biology, offers an in-depth examination of lipid species and their dynamic changes in both healthy and diseased conditions [2]. This comprehensive analytical approach has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying novel biomarkers for a diverse range of clinical diseases and disorders, including metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and inflammatory conditions [2]. Lipids are increasingly understood to be bioactive molecules that regulate critical biological processes including inflammation, metabolic homeostasis, and cellular signalling [2]. The technological improvements in chromatography, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics over recent years have made it possible to perform global lipidomics analyses, allowing the concomitant detection, identification, and relative quantification of hundreds of lipid species [9]. However, the routine integration of lipidomics into clinical practice and biomarker validation faces significant challenges related to inter-laboratory variability, data standardization, lack of defined procedures, and insufficient clinical validation [2]. This technical support center article addresses these reproducibility challenges by providing detailed troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in implementing robust and reproducible lipidomics workflows.

Lipidomics Workflow: From Sample Preparation to Data Interpretation

The lipidomics workflow is a complex and intricate process that encompasses the interdisciplinary intersection of chemistry, biology, computer science, and medicine [10]. Each step is crucial not only for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of experimental results but also for deepening our understanding of lipid metabolic networks. The schematic below illustrates the comprehensive workflow from sample collection to final data interpretation, highlighting key stages where challenges frequently arise.

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Lipidomics Workflow Challenges

Pre-Analytical Phase: Sample Collection and Lipid Extraction

Problem: Inconsistent sample quality leading to unreliable results Solution: Implement standardized sample collection protocols. For plasma and serum samples, maintain consistent clotting times (30 minutes for serum), centrifugation conditions (2000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C), and immediate storage at -80°C. Add antioxidant preservatives such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, 0.01%) to prevent lipid oxidation during processing [9].

Problem: Incomplete or biased lipid extraction Solution: Use validated extraction methods with appropriate solvent systems. The Folch (chloroform:methanol 2:1 v/v) and Bligh & Dyer (chloroform:methanol:water 1:2:0.8 v/v/v) methods remain gold standards. Ensure consistent sample-to-solvent ratios (1:20 for Folch) and pH control. Include internal standards before extraction to monitor recovery and matrix effects [10].

Analytical Phase: Chromatographic Separation and Mass Spectrometry

Problem: Poor chromatographic separation leading to co-elution Solution: Optimize LC conditions based on lipid classes. For reversed-phase separation of non-polar lipids, use C8 or C18 columns with acetonitrile-isopropanol-water gradients. For comprehensive polar lipid analysis, employ hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Maintain column temperature (45-55°C) for retention time stability [9].

Problem: Ion suppression and signal instability Solution: Implement quality control samples including pooled quality control (QC) samples, blank injections, and system suitability standards. Use internal standards for each major lipid class to correct for ion suppression. Monitor signal intensity drift (<20% RSD) and retention time shift (<0.1 min) throughout the analytical sequence [11].

Data Processing and Analysis: From Raw Data to Biological Interpretation

Problem: Inconsistent lipid identification across software platforms Solution: A critical study demonstrated that different lipidomics software platforms show alarmingly low agreement in lipid identifications, with just 14.0% identification agreement when analyzing identical LC-MS spectra using default settings [12]. To address this:

- Validate identifications across both positive and negative ionization modes

- Perform manual curation of MS/MS spectra and retention time alignment

- Use orthogonal identification criteria including accurate mass (<5 ppm error), MS/MS spectral matching, and retention time prediction models

- Implement consensus approaches across multiple software platforms [12]

Problem: Batch effects and technical variability Solution: Apply advanced normalization and batch correction methods. Use quality control-based correction algorithms such as LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) and SERRF (Systematic Error Removal using Random Forest) [11]. Incorporate internal standards for each lipid class to correct for technical variation. Design analytical batches with balanced sample groups and regular QC injections (every 6-10 samples) [11].

Problem: Missing data points in lipidomic datasets Solution: Investigate the underlying causes of missingness before applying imputation. For data missing completely at random, use probabilistic imputation methods. For data missing not at random (due to biological absence or below detection limit), apply left-censored imputation approaches. Never apply imputation methods blindly without understanding the missingness mechanism [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Lipidomics Workflows

Q1: What are the key differences between untargeted, targeted, and pseudo-targeted lipidomics approaches?

A1: The selection of an appropriate analytical strategy is crucial for successful lipidomics studies [10]. The table below compares the three main approaches:

| Parameter | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics | Pseudo-targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Comprehensive discovery of altered lipids [10] | Precise quantification of specific lipids [10] | High coverage with quantitative accuracy [10] |

| Workflow | Global profiling without prior bias [10] | Pre-defined lipid panel analysis [10] | Uses untargeted data to develop targeted methods [10] |

| MS Platform | Q-TOF, Orbitrap [10] | Triple quadrupole (QQQ) [10] | Combination of HRMS and QQQ [10] |

| Acquisition Mode | DDA, DIA [10] | MRM, PRM [10] | MRM with extended panels [10] |

| Quantitation | Relative quantification [10] | Absolute quantification [10] | Improved quantitative accuracy [10] |

| Applications | Biomarker discovery, pathway analysis [10] | Clinical validation, targeted assays [10] | Comprehensive metabolic characterization [10] |

Q2: How can we improve reproducibility in lipid identification across different laboratories?

A2: Improving reproducibility requires standardized workflows and cross-validation practices:

- Adopt Lipidomics Standards Initiative (LSI) guidelines for reporting lipidomics data [11]

- Use common reference materials and standardized protocols for sample preparation

- Implement system suitability tests with quality control standards before each batch

- Perform inter-laboratory cross-validation studies using standardized samples

- Apply data-driven outlier detection and machine learning approaches to identify problematic identifications [12]

Q3: What visualization tools are most effective for interpreting lipidomics data?

A3: Effective visualization is key in lipidomics for revealing patterns, trends, and potential outliers [11]. Recommended approaches include:

- Use violin plots or adjusted box plots instead of traditional bar charts to depict data distributions, especially for skewed data common in lipidomics [11]

- Employ specialized visualizations like lipid maps and fatty acyl-chain plots to reveal trends within lipid classes and fatty acid modifications [11]

- Implement dendrogram-heatmap combinations for interpreting quantitative bulk data and sample clustering patterns [11]

- Apply PCA and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) for unsupervised data exploration [11]

- Utilize volcano plots for visualizing significantly altered lipids in case-control studies [11]

Q4: What computational tools are available for lipidomics data processing and analysis?

A4: The field has developed comprehensive tools in both R and Python for statistical processing and visualization:

- R packages: ggpubr, tidyplots, ggplot2, ComplexHeatmap, ggtree, and mixOmics [11]

- Python libraries: seaborn and matplotlib for flexible and publication-ready visualizations [11]

- Lipid identification software: MS DIAL and Lipostar, though these show significant variability (only 14.0% identification agreement) requiring manual validation [12]

- Specialized resources: GitBook with complete code examples for lipidomics data analysis (https://laboratory-of-lipid-metabolism-a.gitbook.io/omics-data-visualization-in-r-and-python) [11]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipidomics

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | Quantification normalization & recovery monitoring | Use isotopically labeled standards for each major lipid class; add before extraction [9] |

| Sample Preservation Reagents | Prevent lipid oxidation & degradation | BHT (0.01%), EDTA, nitrogen flushing for anaerobic storage [9] |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Lipid isolation from matrices | Chloroform:methanol (Folch), methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) methods; HPLC grade with stabilizers [10] |

| Chromatography Columns | Lipid separation by class & molecular species | C18 for reversed-phase, HILIC for polar lipids; maintain temperature control [9] |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Enhance ionization & separation | Ammonium acetate/formate (5-10 mM), acetic/formic acid (0.1%); LC-MS grade [9] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor instrument performance & reproducibility | NIST SRM 1950 plasma, pooled study samples, custom QC pools [11] |

Data Processing Workflow: From Raw Spectra to Biological Insights

The computational workflow for lipidomics data involves multiple critical steps that transform raw spectral data into biologically meaningful information. The following diagram outlines the key stages and decision points in this process, emphasizing steps that impact reproducibility.

Future Perspectives: Addressing Reproducibility Challenges in Lipidomics

The lipidomics field continues to evolve with promising approaches to enhance reproducibility and clinical translation. Key developments include:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Implementation of AI-driven annotation tools for improved lipid identification and reduced false positives [11]. Support vector machine regression combined with leave-one-out cross-validation has shown promise in detecting outliers and improving identification confidence [12].

Standardization Initiatives: The Lipidomics Standards Initiative (LSI) and Metabolomics Society guidelines provide frameworks for standardized reporting and methodology [11]. Adoption of these standards across laboratories is critical for comparability of results.

Integrated Multi-omics Approaches: Combining lipidomics with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to validate findings through convergent evidence across biological layers [10]. This integrated approach helps distinguish true biological signals from technical artifacts.

Advanced Quality Control Systems: Development of real-time quality control feedback systems that monitor instrument performance and automatically flag analytical batches that deviate from predefined quality metrics [11].

Despite these advancements, the manual curation of lipid identifications remains essential. As one study emphasized, "manual curation of spectra and lipidomics software outputs is necessary to reduce identification errors caused by closely related lipids and co-elution issues" [12]. This human oversight, combined with technological improvements, represents the most promising path forward for reliable lipid biomarker discovery and validation.

Lipids are fundamental cellular components with diverse roles in structure, energy storage, and signaling. In clinical biomarker research, phospholipids (PLs) and sphingolipids (SLs) have emerged as particularly significant classes due to their involvement in critical pathological processes. Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, has revealed that dysregulation of these lipids is implicated in a wide range of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular conditions, and osteoarthritis [13].

The transition of lipid research from basic science to clinical applications faces substantial challenges, particularly concerning reproducibility and validation. Understanding these challenges, along with established troubleshooting methodologies, is essential for advancing reliable biomarker discovery and implementation.

â–¼ Core Analytical Challenges in Lipidomics

A primary obstacle in lipid biomarker research is the concerning lack of reproducibility across analytical platforms. Key issues and their quantitative impacts are summarized below.

Table 1: Key Reproducibility Challenges in Lipid Identification

| Challenge Area | Specific Issue | Quantitative Impact | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Inconsistency | Different software platforms (MS DIAL, Lipostar) analyzing identical LC-MS data | 14.0% identification agreement using default settings [14] [12] | Manual curation of spectra and software outputs |

| Fragmentation Data Use | Use of MS2 spectra for improved identification | Agreement increases to only 36.1% [14] [12] | Validation across positive and negative LC-MS modes |

| Retention Time Utilization | Underutilization of retention time (tR) data in software | Contributes to inconsistent peak identification and alignment [14] | Implement data-driven outlier detection and machine learning |

★ Featured Experimental Protocol: Validating Sphingolipid Biomarkers in Parkinson's Disease

The following detailed protocol is adapted from a study that identified and validated five sphingolipid metabolism-related genes (SMRGs) as potential biomarkers for Parkinson's Disease (PD) [15].

Objective

To identify and validate sphingolipid metabolism-related biomarkers for Parkinson's Disease using transcriptomic data and clinical samples.

Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Source: PD-related transcriptome data were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database.

- Samples: Utilize peripheral blood samples, which are more accessible than brain tissue and can reflect systemic physiological and pathological states. The study used datasets GSE100054 (10 PD vs. 9 healthy controls) and GSE99039 (205 PD vs. 233 healthy controls) [15].

- Gene List: A predefined list of 97 Sphingolipid Metabolism-Related Genes (SMRGs) was compiled from previous literature [15].

Identification of Differentially Expressed SMRGs

- Differential Analysis: Screen for Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) between PD and healthy control samples using the "limma" R package (version 3.52.4) with thresholds of |log2FC| ≥ 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 [15].

- Intersection Analysis: Obtain Differentially Expressed SMRGs (DE-SMRGs) by intersecting the list of DEGs with the list of SMRGs. The referenced study identified 14 DE-SMRGs [15].

- Functional Enrichment: Conduct functional enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology, KEGG pathways) on the DE-SMRGs using tools like the "clusterProfiler" R package (version 4.7.1) to identify involved biological processes (e.g., ceramide metabolic process) [15].

Biomarker Screening and Validation

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network: Construct a PPI network using STRING database (version 11.5) with a confidence score threshold (e.g., 0.4). Analyze the network to identify hub genes using centrality measures like "Closeness." These hub genes (e.g., ARSB, ASAH1, GLB1, HEXB, PSAP) are defined as candidate biomarkers [15].

- Diagnostic Power Assessment: Evaluate the ability of each biomarker to distinguish PD from controls by drawing Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC) using the "pROC" R package (version 1.18.0) [15].

- Expression Validation: Compare the expression levels of the candidate biomarkers between PD and controls in both the discovery and validation datasets (GSE100054 and GSE99039) [15].

Experimental Validation via qRT-PCR

- Technical Validation: Confirm the expression levels of the identified biomarkers (e.g., GLB1, ASAH1, PSAP) in independent clinical human samples using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Consistency with bioinformatics analysis results strengthens the findings [15].

Mechanistic and Translational Exploration

- Immune Infiltration Analysis: Use algorithms like single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) to calculate the proportions of 28 immune cell types in PD versus control samples. Study correlations between biomarker expression and differential immune cells (e.g., macrophages) to explore immune-related mechanisms [15].

- Regulatory Network Construction: Predict targeted miRNAs of the biomarkers using databases like Starbase and construct an mRNA-miRNA regulatory network to reveal potential post-transcriptional regulation [15].

- Drug Prediction: Predict targeted drugs for the biomarkers that could be relevant for clinical treatment of PD (e.g., Chondroitin sulfate was predicted to target ARSB and HEXB simultaneously) [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Sphingolipid Biomarker Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic Datasets | GEO Accession Numbers (e.g., GSE100054, GSE99039) | Provide raw gene expression data for differential analysis [15]. |

| SMRG Gene List | 97 predefined Sphingolipid Metabolism-Related Genes | Serves as a reference list for intersecting with DEGs [15]. |

| R Packages | "limma", "clusterProfiler", "pROC", "WGCNA" | Perform statistical analysis, enrichment analysis, ROC analysis, and co-expression network analysis [15] [16]. |

| PPI Database | STRING database | Provides protein interaction data to identify hub genes [15]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Primers, reverse transcriptase, fluorescent dyes | Experimentally validate gene expression levels in clinical samples [15]. |

| ssGSEA Algorithm | - | Calculates immune cell infiltration scores from gene expression data [15] [16]. |

| miRNA Database | Starbase | Predicts miRNA-mRNA interactions for network construction [15]. |

| BOC-ARG(DI-Z)-OH | Boc-Arg(di-Z)-OH|Amino Acid Derivative | Boc-Arg(di-Z)-OH is a protected L-arginine derivative for peptide synthesis and proteinase inhibitor research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Koumine (Standard) | Koumine (Standard), MF:C20H22N2O, MW:306.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

â–¼ Sphingolipid Metabolism in Disease: Key Pathways

Sphingolipids are not just structural components; they are active signaling molecules. The balance between different sphingolipid species is crucial in determining cell fate, such as in cancer progression.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our lipidomics software identifies different lipid species from the same raw data file than my colleague's software. What is the root cause and how can we resolve this?

A: This is a documented reproducibility challenge. The root cause includes:

- Software-Specific Algorithms: Different platforms use proprietary algorithms for baseline correction, peak identification, and spectral alignment [14].

- Lipid Library Differences: Platforms may rely on different lipid databases (e.g., LipidBlast, LipidMAPS), leading to conflicting identifications [14].

- Solution: Do not rely solely on default "top hit" identifications. Implement a rigorous manual curation process for spectra. Validate identifications across both positive and negative LC-MS modes if possible. As a quality control step, consider using a machine learning-based outlier detection (e.g., support vector machine regression) to flag potential false positives [14] [12].

Q2: How can I determine if a detected lipid change is biologically relevant or just a statistical artifact?

A: To minimize false discoveries:

- Control for Multiplicity: When analyzing thousands of lipid species, use statistical corrections for multiple testing (e.g., False Discovery Rate - FDR) to control the number of false positives [17] [18].

- Account for Biological Variation: Use mixed-effects models if your study design includes multiple observations from the same subject (e.g., longitudinal samples, multiple tumors from one patient) to account for within-subject correlation. Ignoring this can inflate type I error and produce spurious results [17].

- Independent Validation: The most crucial step is to validate your findings in an independent set of samples or a separate cohort [18].

Q3: What is the evidence for phospholipids and sphingolipids as clinically useful biomarkers?

A: Growing evidence from lipidomic profiling supports their clinical relevance:

- Osteoarthritis (OA): Specific PL and SL species are significantly elevated in the serum of patients with early-stage OA (eOA), even before radiologic detection is possible. Serum levels were 3–12 times higher than in synovial fluid, suggesting a systemic response to the local joint disease [19].

- Parkinson's Disease (PD): Five sphingolipid metabolism-related genes (ARSB, ASAH1, GLB1, HEXB, PSAP) were identified as potential biomarkers, with validated expression changes in clinical human samples. These biomarkers are also linked to immune mechanisms like macrophage infiltration in PD [15].

- Cancer: Sphingolipid-related genes can be used to construct prognostic models for cancers like breast cancer. The ceramide/S1P "rheostat" is a key pathway where the balance between these opposing signals influences tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [16].

Q4: How many lipid species should I expect to identify in a typical sample, and why does direct infusion give fewer IDs?

A:

- Expected Identifications: The number varies greatly by sample type, volume, and ion mode. For example, you might identify between 100 to 1,000 lipids in samples ranging from 1 million yeast cells to 80 µL of human plasma extract [20].

- Direct Infusion Limitations: LipidSearch and similar software are less accurate for direct infusion analysis of complex mixtures. This is because several overlapping precursor ions may be co-isolated and co-fragmented, leading to mixture MS2 spectra and lower identification accuracy and numbers. LC-MS separation is strongly recommended for complex samples [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Software Disagreement in Lipid Identification

Problem: Different lipidomics software platforms (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar) provide conflicting lipid identifications from the same raw LC-MS dataset, leading to irreproducible results and hindering biomarker discovery.

Explanation: A 2024 study directly compared two popular open-access platforms, MS DIAL and Lipostar, processing identical LC-MS spectral files from a PANC-1 cell line lipid extract. The analysis revealed a critical lack of consensus between the software outputs [14].

Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Quantify Disagreement | Process identical raw data with multiple software platforms and cross-reference the lists of identified lipids. | Benchmark the scale of the problem. In the referenced study, only 14.0% of lipid identifications agreed when using MS1 data with default settings. Agreement improved to 36.1% when using MS2 fragmentation data, but this remains a significant gap [14]. |

| 2. Mandate Manual Curation | Visually inspect MS2 spectra for top-hit identifications. Check for key fragment ions, signal-to-noise ratios, and co-elution of other compounds. | Software algorithms can be misled by closely related lipids or co-eluting species. Manual verification is the most effective way to reduce false positives. This is a required step, not an optional one [14] [12]. |

| 3. Validate Across Modes | Acquire and process data in both positive and negative ionization modes for your sample. | Many lipids ionize more efficiently in one mode. Confirming an identification in both modes dramatically increases confidence in the result [14]. |

| 4. Implement ML-Based QC | Use a data-driven outlier detection method, such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) regression with Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV). | This machine learning approach can flag lipid identifications with aberrant retention time behavior for further inspection, identifying potential false positives that may slip through initial processing [14]. |

Guide: Improving Analytical Reproducibility Across Batches and Labs

Problem: Lipidomic data suffers from batch effects, instrument variability, and a lack of standardized protocols, making it difficult to reproduce findings in different laboratories or at different times.

Explanation: Reproducibility is hampered by biological variability, lipid structural diversity, inconsistent sample processing, and a lack of defined procedures. One inter-laboratory comparison found only about 40% agreement in post-processed lipid features [14] [1].

Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Plan the Sequence | Use a randomized injection order and include Quality Control (QC) samples—pooled from all samples—throughout the acquisition sequence. | A well-planned sequence with frequent QCs is essential for detecting and correcting for technical noise and systematic drift [11]. |

| 2. Apply Batch Correction | Use advanced algorithms like LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) or SERRF (Systematic Error Removal using Random Forest) on the QC data. | These algorithms model and remove systematic technical variance from the entire dataset, significantly improving data quality and cross-batch comparability [11]. |

| 3. Handle Missing Data | Investigate the cause of missing values before applying imputation. Avoid blind imputation. | Values can be Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), at Random (MAR), or Not at Random (MNAR). The appropriate imputation method (e.g., k-nearest neighbors, minimum value) depends on the underlying cause [11]. |

| 4. Normalize Carefully | Prioritize pre-acquisition normalization using internal standards (e.g., deuterated lipids like the Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX standard). | This accounts for analytical response factors, extraction efficiency, and instrument variability. For post-acquisition, use standards-based normalization where possible [14] [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my lipid identifications differ so much when I use MS DIAL versus Lipostar, even with the same raw data?

A: The core issue lies in the proprietary algorithms, peak-picking logic, and default lipid libraries (e.g., LipidBlast, LipidMAPS) used by each platform. A 2024 benchmark study demonstrated that using default settings, the agreement between MS DIAL and Lipostar can be as low as 14.0% for MS1 data. Even with more confident MS2 data, agreement only reaches 36.1%. This highlights that software output is not ground truth and requires manual curation [14] [12].

Q2: What is the minimum validation required for a confident lipid identification?

A: Following the evolving guidelines of the Lipidomics Standards Initiative (LSI), a confident identification should include [14] [1]:

- MS1 Accurate Mass: Match within a specified ppm error (e.g., < 5 ppm).

- MS2 Spectral Match: MS2 spectrum should match a reference standard or library entry.

- Chromatographic Retention Time: Retention time should align with a authentic standard analyzed under identical LC conditions.

- Ionization Mode Confirmation: Where possible, validate the identification in both positive and negative ionization modes.

Q3: How can I effectively visualize and explore my lipidomics data to identify patterns and outliers?

A: Move beyond simple bar charts. The field is moving towards more informative visualizations [11]:

- Distribution Plots: Use box plots with jitter or violin plots to show the full data distribution.

- Volcano Plots: To visualize the relationship between p-values and fold-change for differential analysis.

- Lipid Maps & Acyl-Chain Plots: Specialized plots that reveal trends within lipid classes and fatty acyl-chain properties.

- Dendrogram-Heatmap Combinations: Powerful for visualizing sample clustering and lipid abundance patterns.

- PCA and UMAP: For unsupervised exploration to reveal sample groupings and potential outliers.

Q4: We have identified a promising lipid biomarker signature. What are the key steps to ensure it is robust and translatable?

A: Transitioning from a discovery signature to a validated biomarker requires rigorous steps [1] [21]:

- Independent Cohort Validation: Confirm the signature's performance in a completely separate, well-designed cohort that reflects the intended-use population.

- Multi-Center Validation: Demonstrate that the signature is reproducible across different clinical sites and analytical laboratories.

- Assay Development: Translate the lipidomic signature into a scalable, targeted, and CLIA-validated assay suitable for clinical settings.

- Integration with Clinical Data: Combine the lipid signature with established clinical variables or other omics data (e.g., proteomics) to improve diagnostic power, as demonstrated in a recent ovarian cancer study [22].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Cross-Platform Software Comparison

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 case study that quantified the reproducibility gap between lipidomics software [14].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Cell Line: Human pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PANC-1).

- Lipid Extraction: Modified Folch extraction using a chilled methanol/chloroform (1:2 v/v) solution, supplemented with 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) to prevent oxidation.

- Internal Standard: Add a quantitative MS internal standard (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX) to a final concentration of 16 ng/mL.

2. LC-MS Analysis:

- Instrumentation: UPLC system coupled to a ZenoToF 7600 mass spectrometer (or equivalent high-resolution instrument).

- Column: Luna Omega 3 µm polar C18 (50 × 0.3 mm).

- Mobile Phase: A) 60:40 Acetonitrile/Water; B) 85:10:5 Isopropanol/Water/Acetonitrile. Both supplemented with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid.

- Gradient:

0 – 0.5 min: 40% B0.5 – 5 min: Ramp to 99% B5 – 10 min: Hold at 99% B10 – 12.5 min: Re-equilibrate to 40% B12.5 – 15 min: Hold at 40% B

- Flow Rate: 8 µL/min.

- Injection Volume: 5 µL.

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), positive mode.

3. Data Processing:

- Software Platforms: Process the identical set of raw spectral files (.wiff, .d, or other format) in both MS DIAL (v4.9 or newer) and Lipostar (v2.1 or newer).

- Settings: Use default parameters for each software initially to simulate a "out-of-the-box" experience for new users. Key settings should include:

- Mass Accuracy: 5 ppm (or as recommended for your instrument).

- Retention Time Tolerance: 0.1 min.

- Peak Width: Automatically detected.

- Identification Score Threshold: >80%.

- Output: Export the final aligned lipid identification tables from each software, including lipid name, formula, class, and aligned retention time.

4. Data Comparison:

- Lipid identifications are considered to be in agreement only if the lipid formula, lipid class, and aligned retention time (within a 5-second window) are identical between MS DIAL and Lipostar.

- Calculate the percentage agreement as:

(Number of Agreed Identifications / Total Number of Unique Identifications) * 100.

Protocol: Implementing a Data-Driven QC Step with Machine Learning

This protocol outlines the SVM-based outlier detection method described in the same 2024 study [14].

1. Input Data Preparation:

- From your lipidomics software output, create a .csv file containing the following columns for each putative lipid identification:

- Chemical formula of the parent molecule

- Lipid class

- Experimental retention time (tR)

- MS1 and MS2 identification status

- Pre-filtering: Exclude lipids with a retention time below 1 minute (or the time of your solvent front), as they have no meaningful column interaction.

2. Model Training and Prediction:

- Algorithm: Support Vector Machine (SVM) Regression.

- Validation: Use Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV).

- Dependent Variable: The experimental retention time (tR).

- Independent Variables: Features derived from the lipid's chemical structure and class that are predictive of tR.

- Process: The model is trained to predict the expected tR for each lipid based on its chemical properties. Lipids whose experimental tR is a significant outlier from the model's prediction are flagged for manual review.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Lipid Identification Reproducibility Gap

Lipidomics Data Analysis & Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX | A quantitative mass spectrometry internal standard containing a mixture of deuterated lipids across multiple classes. | Used for pre-acquisition normalization to account for extraction efficiency, instrument response, and matrix effects. Added prior to lipid extraction [14]. |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | An antioxidant added to lipid extraction solvents. | Prevents oxidation of unsaturated lipids during the extraction and storage process, preserving the native lipid profile [14]. |

| Ammonium Formate / Formic Acid | Common mobile phase additives in LC-MS. | Ammonium formate promotes efficient ionization in ESI-MS. Formic acid helps with protonation in positive ion mode, improving signal for many lipid classes [14]. |

| QC Pooled Sample | A quality control sample created by pooling a small aliquot of every biological sample in the study. | Injected repeatedly throughout the LC-MS sequence to monitor instrument stability, correct for batch effects, and assess data quality [11]. |

| R and Python Scripts (GitBook) | Open-source code for statistical processing, normalization, and visualization of lipidomics data. | Provides standardized, reproducible workflows for data analysis, moving away from ad-hoc choices. Includes modules for batch correction (SERRF), PCA, and advanced plots [11]. |

| GW-406381 | GW-406381, CAS:537697-89-5, MF:C21H19N3O3S, MW:393.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isoscabertopin | Isoscabertopin, MF:C20H22O6, MW:358.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagnostic Lipidomic Signature for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

A 2024 study identified and validated a blood-based diagnostic lipidomic signature for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [23] [24]. This signature, comprising just two molecular lipids, demonstrated superior diagnostic performance compared to high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and performed comparably to fecal calprotectin, a standard marker of gastrointestinal inflammation [23].

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of the Pediatric IBD Lipidomic Signature

| Biomarker | Lipid Species | Concentration Change in IBD | Comparison to hs-CRP | Comparison to Fecal Calprotectin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Lipid Signature | Lactosyl ceramide (d18:1/16:0) | Increased | Improved diagnostic prediction | No substantial difference in performance |

| Phosphatidylcholine (18:0p/22:6) | Decreased | Adding hs-CRP to signature did not improve performance |

The study analyzed blood samples from a discovery cohort and validated the findings in an independent inception cohort, confirming the results in a third pediatric cohort [23] [24]. The signature's translation into a scalable blood test has the potential to support clinical decision-making by providing a reliable, easily obtained biomarker [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow outlines the key experimental steps for identifying and validating the lipidomic signature, from cohort design to data analysis.

Key Methodological Details:

- Cohorts: The study used three independent pediatric cohorts: a discovery cohort (n=94), a validation cohort (n=117), and a confirmation cohort (n=263). All IBD patients were newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve, and were compared to age-comparable symptomatic non-IBD controls [23].

- Sample Preparation: Blood samples were collected, and plasma or serum was isolated. Proper pre-analytical handling is critical; samples should be immediately processed or frozen at -80°C to prevent enzymatic degradation of lipids, such as the generation of lysophospholipids [25]. Internal standards were likely added prior to lipid extraction for accurate quantification, as this is considered a best practice [25] [26].

- Lipid Extraction and Analysis: Lipids were extracted from plasma/serum. While the specific method was not detailed, common approaches include liquid-liquid extraction methods like Bligh & Dyer or MTBE-based protocols, which are considered the gold standard [25] [26]. Lipidomic analysis was performed using mass spectrometry-based techniques, likely liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), which provides high sensitivity and specificity for lipid identification and quantification [23] [26].

- Data Processing and Statistical Analysis: Raw MS data were processed using software for peak identification, alignment, and quantification. The specific two-lipid signature was identified through statistical analysis comparing the lipid profiles of IBD patients and controls. Best practices for data analysis include handling missing values, normalization to correct for unwanted variation, and the use of multivariate statistics [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Lipidomics Biomarker Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards (IS) | Corrects for variability in extraction and analysis; enables absolute quantification. | Use stable isotope-labeled IS for each lipid class of interest. Add prior to extraction [25] [26]. |

| Chloroform & Methanol | Primary solvents for biphasic liquid-liquid lipid extraction (e.g., Folch, Bligh & Dyer). | Chloroform is hazardous. MTBE is a less toxic alternative for some protocols [25] [26]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Identification and quantification of individual lipid species. | LC-MS/MS systems are widely used. High mass resolution (>75,000) helps avoid overlaps [26]. |

| Chromatography Column | Separates lipid species by class or within class prior to MS detection. | Reversed-phase C18 columns are common for separating lipid species [28]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Monitors instrument performance and technical variability during sequence. | Use pooled samples from all study samples; essential for batch effect correction [27]. |

| Data Processing Software | Converts raw MS data into identified and quantified lipid species. | Platforms include MS DIAL, Lipostar. Manual curation of results is critical due to low inter-software reproducibility [28]. |

| Asatone | Asatone, MF:C24H32O8, MW:448.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-(+)-Cellotetraose | D-(+)-Cellotetraose, MF:C24H42O21, MW:666.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Lipidomic Biomarkers in Osteonecrosis

At the time of this writing, the provided search results do not contain specific information on successful lipidomic signatures for osteonecrosis. Research in this area may be emerging but is not captured in the current search. For this field, the general principles, challenges, and best practices outlined in this document serve as a foundational guide.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our lipidomics software outputs are inconsistent. How can we improve the confidence of our lipid identifications?

A: Inconsistent identification across different software platforms is a major challenge. One study found only 14-36% agreement between popular platforms like MS DIAL and Lipostar, even when using identical data [28].

- Multi-platform Validation: Process your data with more than one software tool and manually curate lipids that are consistently identified.

- Leverage Multiple Data Dimensions: Do not rely solely on mass-to-charge ratio (m/z). Use MS/MS fragmentation spectra and retention time (RT) matching to authentic standards, if available [25] [28].

- Manual Curation: Visually inspect MS2 spectra to confirm fragment ions match the proposed lipid structure and rule out co-eluting interferences [28].

- Follow Reporting Standards: Adhere to the Lipidomics Standards Initiative (LSI) guidelines for reporting lipid data, clearly stating the level of identification confidence [25].

Q2: We see high variability in our lipid measurements. What are the critical pre-analytical steps to control?

A: Pre-analytical factors are a primary source of variability.

- Sample Stability: Enzymatic activity continues after sampling. Immediately freeze samples in liquid nitrogen (tissues) or at -80°C (biofluids) [25] [26].

- Control Lipolysis: Lipids like lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) are generated artificially after blood draw. Special protocols, such as acidified Bligh & Dyer extraction, are required to preserve in vivo concentrations [25].

- Standardize Extraction: Add a cocktail of internal standards before the extraction step to account for recovery differences. Choose an extraction method (e.g., Folch, Bligh & Dyer, MTBE) appropriate for your lipid classes of interest, as recovery can vary [25] [26].

Q3: How should we handle missing values in our lipidomics dataset before statistical analysis?

A: Missing values are common, often because a lipid's abundance is below the limit of detection (LOD).

- Filter First: Remove lipid species with a high percentage of missing values (e.g., >35%) across all samples [27].

- Impute Intelligently: Use imputation methods suitable for the nature of the missingness. A common and effective strategy for values missing not at random (MNAR, e.g., below LOD) is to impute with a small constant value, such as a percentage of the minimum concentration for that lipid. For data missing at random, k-nearest neighbors (kNN) or random forest imputation are often recommended [27].

Q4: What are the biggest hurdles in translating a discovered lipidomic signature, like the pediatric IBD signature, into a clinically approved test?

A: The path from discovery to clinic is challenging [1] [2].

- Reproducibility and Standardization: The lack of standardized protocols across labs leads to inter-laboratory variability. Analytical techniques and results must be harmonized [1] [25] [2].

- Multi-Center Validation: A signature must be validated in large, independent, and multi-center cohorts that reflect the intended-use population. This is often lacking in early-stage studies [1].

- Regulatory Hurdles: The regulatory framework for complex lipidomic biomarkers is still evolving. Demonstrating analytical validity, clinical validity, and clinical utility to regulatory bodies like the FDA is a complex process [1]. Currently, very few lipid-based tests are FDA-approved.

Methodological Frameworks and Analytical Strategies for Robust Lipidomics

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of cellular lipids, faces significant challenges in biomarker validation and reproducibility. Selecting the appropriate analytical approach—untargeted or targeted lipidomics—is critical for generating reliable, translatable data in disease research and drug development. This guide provides technical support for navigating these methodologies within the context of biomarker reproducibility challenges.

Core Concepts: Untargeted vs. Targeted Lipidomics

What is the fundamental difference between untargeted and targeted lipidomics?

Untargeted and targeted lipidomics differ primarily in their scope and purpose. Untargeted lipidomics is a comprehensive, discovery-oriented approach that aims to identify and measure as many lipids as possible in a sample without bias. In contrast, targeted lipidomics is a focused, quantitative method that precisely measures a predefined set of lipids, often based on prior hypotheses or untargeted findings [29]. This fundamental distinction guides all subsequent experimental design choices.

When should I choose an untargeted versus a targeted approach?

The choice depends entirely on your research question and goals [29]. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of each approach:

| Feature | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Hypothesis generation, novel biomarker discovery [29] [30] | Hypothesis testing, biomarker validation [29] [30] |

| Scope | Broad, unbiased profiling of known and unknown lipids [29] | Narrow, focused on specific, pre-defined lipids [29] |

| Quantification | Relative quantification (semi-quantitative) [31] [30] | Absolute quantification using internal standards [31] [29] |

| Throughput & Workflow | Complex data processing, time-consuming lipid identification [31] [29] | Streamlined, high-throughput, automated data processing [31] |

| Ideal Application | Exploratory studies, discovering novel lipid pathways [29] | Clinical diagnostics, therapeutic monitoring, validating findings [29] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

What are the standard experimental workflows for untargeted and targeted lipidomics?

The workflows for both methodologies involve distinct steps from sample preparation to data analysis, each optimized for its specific goal.

Untargeted Lipidomics Workflow

- Sample Preparation: Lipids are extracted from biological matrices (e.g., plasma, tissue) using solvents like methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) or chloroform-methanol. This step aims for global metabolite extraction to maintain a representative profile of the entire lipidome [29] [32].

- Data Acquisition: Analysis is typically performed using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). High-resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., Time-of-Flight or Orbitrap) are preferred for their ability to distinguish between thousands of features. Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) modes, such as SWATH, are often used to comprehensively fragment all ions in a sample, ensuring no data is missed [33] [29].

- Data Processing and Lipid Identification: This is a critical and complex step. Software tools (e.g., LipidView, LipidXplorer) are used to process the large datasets. They perform peak alignment, deconvolution, and identification by matching acquired mass-to-charge ratios and fragmentation patterns against lipid databases like LIPID MAPS [33] [1]. This process often requires manual validation due to lipid complexity and potential for misidentification [31].

Targeted Lipidomics Workflow

- Sample Preparation: Lipids are extracted with solvents, but a key difference is the addition of a mixture of stable, isotopically labeled internal standards specific to the lipid classes being targeted. These standards are crucial for correcting for variations in extraction and ionization efficiency, enabling absolute quantification [31] [29] [32].

- Data Acquisition: Analysis often uses LC coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometers. The instrument is operated in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode, which monitors specific precursor-to-product ion transitions for each target lipid. This method offers high sensitivity and specificity by filtering out much of the chemical noise [31] [32]. Some platforms, like the Lipidyzer, also use Differential Mobility Spectrometry (DMS) to add another dimension of separation for isomers and isobars [31].

- Data Processing and Quantification: Data processing is more straightforward. The peak areas for each target lipid are integrated and normalized against their corresponding internal standards. Concentrations are calculated using pre-established linear calibration curves, resulting in absolute quantitative data (e.g., nmol/g) [31] [34].

Technical Performance and Reproducibility

How do the precision and accuracy of these platforms compare, and what are the implications for biomarker validation?

Cross-platform comparisons reveal key performance differences that directly impact biomarker validation. A study comparing an untargeted LC-MS approach with the targeted Lipidyzer platform on mouse plasma found both could profile over 300 lipids [31]. The quantitative performance, however, showed notable differences:

| Performance Metric | Untargeted LC-MS | Targeted Lipidyzer |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-day Precision (Median CV) | 3.1% [31] | 4.7% [31] |

| Inter-day Precision (Median CV) | 10.6% [31] | 5.0% [31] |

| Technical Repeatability (Median CV) | 6.9% [31] | 4.7% [31] |

| Accuracy (Median % Deviation) | 6.9% [31] | 13.0% [31] |

These metrics highlight a critical trade-off: while the targeted platform demonstrated superior precision (repeatability), the untargeted platform showed slightly better accuracy in this specific comparison [31]. Reproducibility remains a major hurdle in lipidomics. One analysis found that different software platforms agreed on only 14-36% of lipid identifications from identical LC-MS data, underscoring the need for standardized protocols and rigorous validation, especially in untargeted studies [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

We often struggle with data reproducibility in our untargeted studies. What steps can we take to improve this?

Improving reproducibility in untargeted lipidomics requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Standardize Protocols: Implement and meticulously document standardized protocols for sample collection, extraction, and data acquisition across all samples and batches.

- Use Quality Controls: Incorporate pooled quality control (QC) samples throughout your batch run to monitor instrument stability and for data normalization.

- Leverage Multi-dimensional Separation: Techniques like Differential Mobility Spectrometry (DMS) can resolve isomeric and isobaric lipids that co-elute in standard LC, reducing misidentification and improving consistency [33].

- Adopt Robust Data Processing: Use validated software and consistently apply stringent filters for identification confidence (e.g., using MS/MS spectral matching) and blank subtraction.

How can we bridge the gap between biomarker discovery and validation?

The most effective strategy is an integrative one. Use untargeted lipidomics for the initial discovery phase to identify a broad list of lipid species that are differentially regulated in your condition of interest. Then, take the most promising candidate biomarkers and develop a targeted, MRM-based method for absolute quantification in a larger, independent cohort of samples [29] [1]. This sequential approach leverages the strengths of both platforms: the breadth of untargeted and the precision of targeted.

Our targeted method seems to be reaching a saturation point for very abundant lipids. How can we address this?

Signal saturation or plateauing at high concentrations, as observed for classes like TAG and CE in the Lipidyzer platform [31], can be mitigated by:

- Sample Dilution: The simplest solution is to dilute the sample and re-inject.

- Calibration Curve Range: Ensure your calibration curves cover the entire dynamic range of your samples. You may need to exclude the highest concentration point if it consistently causes plateauing [31].

- Alternative Ionization: Explore switching ionization modes (e.g., from positive to negative) if applicable, as different lipid classes can ionize with varying efficiencies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for successful lipidomics experiments.

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Enables absolute quantification in targeted methods; corrects for extraction and ionization variability [31] [29]. | Crucial for accurate quantification. Should be added at the beginning of sample preparation. |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Solvent for lipid extraction; separates lipids from proteins and other biomolecules [29] [32]. | A common choice for robust, high-recovery lipid extraction. |

| LC Columns (C18, HILIC) | Separates lipid species by hydrophobicity (C18) or by lipid class based on polar head groups (HILIC) [29] [32]. | Column choice dictates lipid separation and coverage. |

| Mass Spectrometer (Q-TOF, Orbitrap, Triple Quad) | Identifies and quantifies lipids. Q-TOF/Orbitrap for high-res untargeted; Triple Quad for sensitive targeted MRM [31] [33] [29]. | Instrument selection is fundamental to the experimental design. |

| Lipid Identification Software | Processes complex MS data; identifies lipids by matching m/z and MS/MS spectra to databases [33] [1]. | Essential for untargeted data analysis. Database quality limits identification confidence. |

| Anemarsaponin E | Anemarsaponin E, MF:C46H78O19, MW:935.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganoderenic acid E | Ganoderenic acid E, MF:C30H40O8, MW:528.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Navigating the challenges of lipidomic biomarker research requires a deliberate and informed choice between untargeted and targeted strategies. By understanding their complementary strengths and limitations—where untargeted lipidomics excels in unbiased discovery and targeted lipidomics provides the quantitative rigor needed for validation—researchers can design robust workflows. Adhering to rigorous protocols and adopting an integrative approach is paramount for overcoming reproducibility hurdles and translating lipidomic findings into clinically relevant biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

FAQs on Platform Performance and Reprodubility

1. Why do my lipid identifications vary significantly between different lipidomics software platforms when processing the same dataset?

Variations arise from differences in algorithmic processing, spectral libraries, and alignment methodologies inherent to each platform. A 2024 study directly comparing MS DIAL and Lipostar processing of identical LC-MS spectra found only 14.0% identification agreement using default settings [14]. Even when utilizing fragmentation data (MS2), agreement rose only to 36.1% [14]. Key sources of discrepancy include:

- Spectral Libraries: Platforms use different libraries (e.g., LipidBlast, LipidMAPS), leading to different matching results [14].

- Co-elution and Co-fragmentation: Closely related lipids or isobaric species eluting simultaneously can lead to misinterpreted MS2 spectra [14].

- Underutilization of Retention Time (tR): Many software tools do not fully leverage tR, a critical parameter for distinguishing isobaric lipids [14].

2. What steps can I take to improve confidence in lipid identifications and ensure reproducibility for biomarker validation?

A multi-layered validation strategy is essential to close the reproducibility gap [14].

- Manual Curation: Manually inspect spectral data, including peak shape and fragmentation patterns, to verify software-generated identifications [14].

- Multi-mode Chromatography: Validate identifications across both positive and negative LC-MS modes to confirm lipid class and acyl chain composition [35].

- Leverage Retention Time: Use experimentally derived or predicted retention times to support identifications and discriminate isobars [35].

- Implement Quality Controls: Use internal standards for normalization and monitor analytical precision. One protocol using internal standard normalization achieved relative standard deviations of 5-6% in serum analyses [36].

3. How can I optimize MS/MS fragmentation for confident annotation of phospholipid and sphingolipid classes?

Optimal collision energy is key to generating diagnostic fragment ions.

- For Phosphatidylcholines (PC) in negative ion mode, a collision energy ramp between 20–40 eV is suitable for generating diagnostic ions, including demethylated phosphocholine ions (e.g., m/z 168.0423) and carboxylate ions from fatty acyl chains [35].

- The negative ion mode is particularly valuable for identifying fatty acyl chains across phospholipid subclasses (PE, PI, PS, PG, PA) and can help determine their sn-1/sn-2 positions on the glycerol backbone based on carboxylate ion intensity ratios [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Lipid Identification Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low identification agreement between software platforms | Different default processing parameters and spectral libraries [14] | Manually curate outputs and align software settings where possible. Use a consensus approach from multiple platforms [14]. |

| Inconsistent retention times | Column degradation, mobile phase preparation errors, or gradient instability | Implement a rigorous column cleaning and testing schedule. Calibrate retention times using stable internal standards [36]. |

| Poor fragmentation spectra for low-abundance lipids | Insufficient precursor ion signal, improper collision energy [14] | Increase injection concentration if possible. Use stepped normalized collision energy to capture multiple fragment types [37]. |

| Poor reproducibility in quantitative results | Inconsistent sample preparation, instrument drift, lack of normalization | Use a simple, standardized extraction protocol (e.g., methanol/MTBE). Employ a suite of internal standards for normalization to achieve ~5-6% RSD [36]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Software Identification Agreement

This table summarizes data from a case study processing identical LC-MS spectra with two software platforms [14].

| Comparison Metric | MS1 Data (Accurate Mass) | MS2 Data (Fragmentation) |

|---|---|---|

| Identification Agreement | 14.0% | 36.1% |

| Major Challenge | Inability to distinguish isobaric and co-eluting lipids without fragmentation data [14]. | Co-fragmentation of closely related lipids within the precursor ion selection window [14]. |

| Recommended Action | Require MS2 validation for all putative identifications, especially for biomarker candidates. | Perform manual curation of MS2 spectra and validate across positive and negative ionization modes [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Lipid Annotation

Protocol 1: Molecular Networking Coupled with Retention Time Prediction

This protocol provides a systematic approach for annotating phospholipids and sphingolipids by combining MS/MS spectral similarity with chromatographic behavior [35].

- Standard Acquisition: Analyze a mixture of 65 lipid standards to establish class-specific fragmentation patterns and define the relationship between lipid structure and retention time [35].

- Data Pre-processing: Convert LC-MS/MS data and perform feature detection (e.g., using MzMine 2) to align mass, retention time, and intensity data [35].

- Molecular Network Creation: Upload processed MS/MS data to the GNPS platform to generate a molecular network. Structurally similar lipids will cluster together based on spectral similarity [35].

- Annotation and Validation: Annotate unknown lipids within a cluster based on the annotated standard. Reinforce this annotation by comparing the experimental retention time of the unknown with the predicted retention time derived from the standard curve [35]. This method enabled the annotation of over 150 unique lipid species in a study on human corneal epithelial cells [35].

Protocol 2: A Reproducible Microscale Serum Lipidomics Workflow

This protocol is designed for high-throughput clinical applications with minimal sample consumption [36].

- Sample Extraction: Add 10 µL of serum to a simplified methanol/methyl tert-butyl ether (1:1, v/v) extraction solvent. Vortex and centrifuge to separate phases [36].

- Internal Standard Addition: Incorporate a ready-to-use internal standard mix (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH) at the extraction stage for normalization. A concentration of 16 ng/mL is typical [14] [36].

- LC-HRMS Analysis:

- Column: Use a reversed-phase column (e.g., Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3, 1.8 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm).

- Gradient: Employ a water/acetonitrile (A) and isopropanol/acetonitrile (B) gradient with 10 mM ammonium formate/0.1% formic acid: 30% B to 60% B in 4.0 min, to 100% B at 9.0 min, hold until 15.0 min [36] [37].

- MS Parameters: Use a high-resolution mass spectrometer in both positive and negative ESI mode with data-dependent MS2 (ddMS2) at a resolution of 17,500 and stepped collision energies [37].

- Data Processing: Use a semi-automated script or software (e.g., Compound Discoverer) for feature alignment, normalization against internal standards, and statistical analysis [36] [37].

Workflow Visualization

This workflow highlights the necessity of using multiple software platforms and stringent manual validation steps to overcome reproducibility challenges in lipidomic biomarker discovery [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX | A quantitative mass spectrometry internal standard; a mixture of deuterated lipids used for normalization and quality control [14]. |

| Methanol/MTBE (1:1, v/v) | A simplified extraction solvent protocol for simultaneous lipid and metabolite coverage from minimal serum volumes (e.g., 10 µL) [36]. |

| Ammonium Formate & Formic Acid | Mobile phase additives that enhance ionization efficiency and support the formation of [M+HCOO]â» adducts in negative ion mode for lipids like phosphatidylcholines [35] [37]. |

| Luna Omega Polar C18 / Acquity UPLC HSS T3 | Common UHPLC columns providing reversed-phase separation for complex lipid mixtures, crucial for resolving isobaric species [14] [37]. |

| LipidBlast, LipidMAPS, ALEX123 | Spectral libraries used by software platforms for matching accurate mass and MS/MS data; using multiple libraries can improve annotation coverage [14]. |

| m-PEG3-S-PEG1-C2-Boc | m-PEG3-S-PEG1-C2-Boc, MF:C16H32O6S, MW:352.5 g/mol |

| HKOCl-3 | HKOCl-3, MF:C26H14Cl2O6, MW:493.3 g/mol |

The Critical Role of Internal Standards and Quality Control in Lipid Quantification

Why are Internal Standards (IS) essential for accurate lipid quantification?

Internal Standards (IS) are chemically analogous compounds added to samples at a known concentration before lipid extraction. They are critical for accurate quantification because they correct for losses during sample preparation, matrix effects during ionization, and instrument variability.

| Function | Description | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|