Non-Coding RNA Dysregulation in the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor Microenvironment: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Avenues

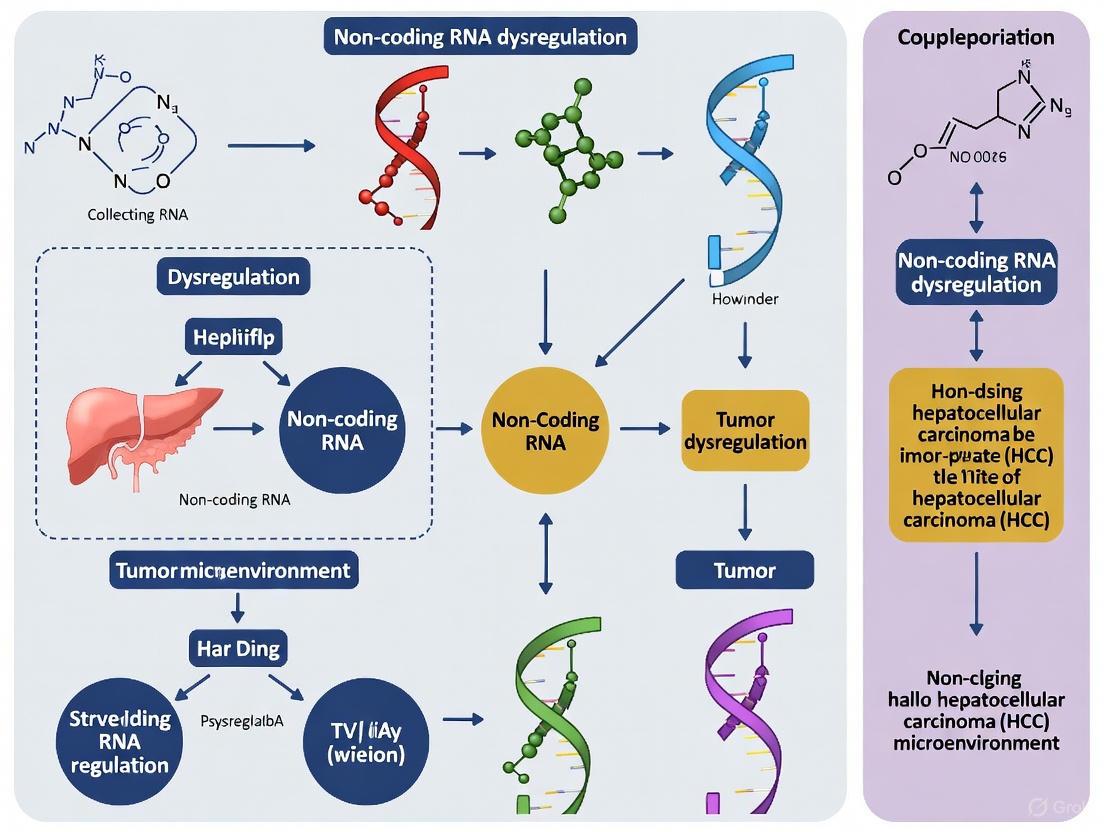

This article comprehensively explores the critical roles of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—including miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs—in reshaping the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumor microenvironment (TME).

Non-Coding RNA Dysregulation in the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor Microenvironment: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Avenues

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the critical roles of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—including miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs—in reshaping the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumor microenvironment (TME). It details the foundational mechanisms by which dysregulated ncRNAs influence key processes such as metabolic reprogramming, immune evasion, and metastasis. The scope extends to methodological advances in targeting ncRNAs, troubleshooting delivery and specificity challenges, and validating ncRNAs as prognostic biomarkers and predictors of immunotherapy response. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to highlight the significant potential of ncRNA-based strategies in improving HCC diagnosis and therapy.

The Landscape of ncRNA Dysregulation in HCC: Core Players and Microenvironmental Crosstalk

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression and central players in cellular physiology and disease. Once dismissed as transcriptional "noise," these RNA molecules are now recognized for their roles in fine-tuning nearly every aspect of cell biology [1] [2]. In the context of cancer, and particularly in the complex ecosystem of the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tumor microenvironment (TME), the dysregulation of ncRNAs contributes significantly to tumor progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance [3] [4]. This review provides a comprehensive technical guide to three principal ncRNA classes—microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs)—focusing on their biogenesis, molecular functions, and specific roles in shaping the HCC TME to inform future research and therapeutic development.

miRNA: Biogenesis and Functional Mechanisms

Canonical Biogenesis Pathway

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs approximately 22-23 nucleotides in length that function as key post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression [5]. Their biogenesis begins with RNA Polymerase II/III transcription of primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts, which can be several kilobases long and contain one or more hairpin structures [6] [5]. In the nucleus, the microprocessor complex—comprising the RNase III enzyme Drosha and its cofactor DGCR8—cleaves the pri-miRNA to release a ~60-90 nucleotide precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) featuring a 2-nucleotide 3' overhang [6] [7]. Exportin-5 then transports the pre-miRNA to the cytoplasm in a Ran-GTP-dependent manner, where the RNase III enzyme Dicer cleaves off the terminal loop to generate an unstable miRNA:miRNA* duplex of approximately 19-22 nucleotides [6] [5].

One strand of this duplex (the guide strand) is selectively loaded into an Argonaute (AGO) protein to form the core of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), while the passenger strand is typically degraded [6] [5]. Strand selection depends on thermodynamic stability, with the strand possessing lower 5' stability often being preferentially selected [5]. The mature RISC complex uses the miRNA as a guide to identify complementary mRNA targets through base pairing, primarily between the miRNA "seed region" (nucleotides 2-8) and sequences in the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) of target mRNAs [6].

Non-Canonical Biogenesis Pathways

Several non-canonical miRNA biogenesis pathways bypass elements of the canonical pathway. Mirtrons represent one well-characterized class of non-canonical miRNAs that are processed from introns during mRNA splicing, independent of Drosha/DGCR8 processing [5]. These short intronic RNAs fold into pre-miRNA-like structures that are directly exported by Exportin-1 and processed by Dicer in the cytoplasm [5]. Another non-canonical pathway involves 7-methylguanosine (m7G)-capped pre-miRNAs that are transcribed as short hairpin RNAs and exported via Exportin-1 without Drosha cleavage, exhibiting strong 3p strand bias due to the 5' cap preventing 5p strand loading into Argonaute [5]. Additionally, some Dicer-independent miRNAs are processed by Drosha from endogenous short hairpin RNA (shRNA) transcripts and require AGO2 for their cytoplasmic maturation [5].

Mechanisms of Gene Regulation

miRNAs regulate gene expression through several mechanisms, with the outcome largely determined by the degree of complementarity between the miRNA and its target. Perfect or near-perfect complementarity typically leads to AGO2-mediated endonucleolytic cleavage and destruction of the target mRNA [5]. However, most animal miRNA-target interactions involve imperfect complementarity, particularly with central mismatches that prevent AGO2 cleavage activity [5]. In these cases, gene silencing occurs through translational repression coupled with mRNA destabilization via deadenylation and decapping [5].

The canonical targeting mechanism involves base pairing between the miRNA seed region and complementary sequences in the 3' UTR of target mRNAs [6]. However, functional miRNA binding sites have also been identified in 5' UTRs, coding sequences, and gene promoters, expanding the regulatory potential of miRNAs [5]. Under certain conditions, miRNA binding can even activate translation rather than repress it, demonstrating the context-dependent nature of miRNA-mediated regulation [5].

Table 1: Key Proteins in miRNA Biogenesis and Function

| Protein | Function | Localization |

|---|---|---|

| Drosha | RNase III enzyme that cleaves pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA | Nucleus |

| DGCR8 | DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8; cofactor for Drosha | Nucleus |

| Exportin-5 | Transports pre-miRNA from nucleus to cytoplasm | Nuclear membrane/Cytoplasm |

| Dicer | RNase III enzyme that cleaves pre-miRNA to mature miRNA duplex | Cytoplasm |

| Argonaute (AGO) | Core component of RISC; facilitates miRNA-guided target recognition | Cytoplasm |

| GW182 | Scaffolding protein that recruits effector complexes for silencing | Cytoplasm |

Figure 1: miRNA Biogenesis Pathway. The diagram illustrates the sequential nuclear and cytoplasmic processing steps from miRNA gene transcription to mature miRNA-mediated gene silencing.

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

Definition and Genomic Origins

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are broadly defined as RNA transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides that lack significant protein-coding potential [2]. A more precise classification suggests lncRNAs should be considered as transcripts longer than 500 nucleotides, distinguishing them from other non-coding RNA classes [2]. These molecules display tremendous diversity in their genomic origins and structures. lncRNAs can be intergenic (lincRNAs), antisense, intronic, or sense-overlapping relative to protein-coding genes [2]. They are primarily transcribed by RNA Polymerase II and often undergo 5' capping, splicing, and polyadenylation, though notable exceptions exist [2]. The genomic organization of lncRNA genes is particularly complex, with many overlapping protein-coding genes or being located within intronic regions, creating challenges for functional annotation and genetic manipulation [2].

Structural Features and Functional Diversity

lncRNAs exhibit complex secondary and tertiary structures that are crucial for their function. They can form hairpins, stem-loops, and pseudoknots through base pairing, creating conserved short structural modules that mediate specific interactions [6]. For instance, SINEUP lncRNAs contain conserved modules that enhance translational efficiency, while TERRA lncRNAs interact with LSD1 through specific structural domains to promote R-loop formation and telomere maintenance via phase separation mechanisms [6]. The TubAR lncRNA exemplifies how specific secondary structures enable functional interactions, as it binds to α- and β-tubulin heterodimers to stabilize microtubules and support cerebellar myelination [6].

The functional repertoire of lncRNAs is equally diverse. They participate in transcriptional regulation by modulating chromatin accessibility and transcription factor activity [6] [3]. For example, LINC00673 can alter chromatin architecture in breast cancer cells, thereby influencing gene expression patterns [6]. lncRNAs also play important roles in epigenetic regulation by recruiting histone modification complexes or DNA methyltransferases to specific genomic loci [6]. Additionally, many lncRNAs function as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) by sequestering miRNAs and preventing them from repressing their target mRNAs [1] [3]. NEAT1 represents a well-characterized example of this sponge function in HCC, where it regulates the miR-155/Tim-3 pathway in CD8+ T cells [3].

Table 2: lncRNA Functional Mechanisms and Examples

| Mechanism | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Regulation | Modulate chromatin structure and transcription factor activity | LINC00673 in breast cancer [6] |

| Epigenetic Modification | Recruit histone/DNA modifying complexes to specific loci | Multiple lncRNAs in cancer [6] |

| miRNA Sponging | Sequester miRNAs to prevent target mRNA repression | NEAT1 in HCC [3] |

| Protein Scaffolding | Serve as platforms for assembling multi-protein complexes | TERRA in telomere maintenance [6] |

| Structural Role | Directly interact with cellular structures | TubAR in microtubule stabilization [6] |

Circular RNAs (circRNAs)

Biogenesis and Structural Characteristics

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) constitute a widespread class of covalently closed circular RNAs generated through a "back-splicing" mechanism where a downstream 5' splice site joins an upstream 3' splice site [8] [4]. This unique biogenesis creates circular molecules that lack free 5' and 3' ends, making them exceptionally resistant to exonuclease degradation and conferring greater stability than their linear counterparts [8] [4]. Based on their sequence composition, circRNAs are categorized into several types: exonic circRNAs (EciRNAs) derived solely from exons; circular intronic RNAs (ciRNAs) originating from introns; exonic-intronic circRNAs (EIciRNAs) containing both exonic and intronic sequences; and antisense or intergenic circRNAs transcribed from non-annotated genomic regions [4]. Approximately 80% of identified circRNAs are EciRNAs that predominantly localize to the cytoplasm, while ciRNAs and EIciRNAs are often nuclear [4].

Molecular Functions and Mechanisms

circRNAs employ diverse molecular mechanisms to regulate cellular processes:

miRNA Sponging: Many circRNAs function as competitive endogenous RNAs by containing multiple binding sites for specific miRNAs, effectively sequestering them and preventing their interaction with target mRNAs [8] [4]. For instance, circ_0056618 promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer by binding miR-206 and consequently upregulating CXCR4 and VEGFA expression [8].

Protein Interactions: circRNAs can bind to RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) to form ribonucleoprotein complexes that influence protein function, localization, or stability [8] [4]. This interaction can modulate various aspects of RNA metabolism, including splicing, stability, and translation.

Translation: Although traditionally classified as non-coding, some circRNAs have been shown to be translatable, producing unique peptides with biological functions [8]. This translation typically occurs through cap-independent mechanisms, often involving internal ribosome entry sites (IRES).

Gene Expression Regulation: Nuclear circRNAs can influence transcription by interacting with U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) or by modulating RNA Polymerase II activity [4]. EIciRNAs, for example, can enhance the expression of their parental genes through such mechanisms.

Figure 2: circRNA Functional Mechanisms. The diagram illustrates four primary functions of circRNAs: miRNA sponging, protein interactions, peptide translation, and transcription regulation.

ncRNA Crosstalk in the HCC Tumor Microenvironment

The Competitive Endogenous RNA (ceRNA) Hypothesis

The competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis proposes a sophisticated regulatory network where different RNA species communicate through shared miRNA response elements (MREs) [1]. In this model, lncRNAs and circRNAs function as molecular "sponges" that compete for miRNA binding, thereby preventing these miRNAs from repressing their target mRNAs [1]. This ceRNA network creates an intricate layer of post-transcriptional regulation that fine-tunes gene expression dynamics. In HCC, this crosstalk is particularly relevant for regulating oncogenic pathways, immune responses, and cellular metabolism within the tumor microenvironment [1] [3].

ncRNA-Mediated Regulation of the HCC Immune Microenvironment

The HCC tumor microenvironment features a complex ecosystem where tumor cells interact with various immune cells, stromal components, and extracellular matrix [3]. ncRNAs play pivotal roles in shaping this microenvironment to either promote or suppress antitumor immunity. lncRNAs such as TUG1, LINC01116, CRNDE, and NEAT1 have been identified as key regulators of immune cell function in HCC [3]. For instance, NEAT1 and Tim-3 are significantly upregulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of HCC patients, where NEAT1 promotes CD8+ T cell apoptosis and suppresses their cytolytic activity by regulating the miR-155/Tim-3 pathway [3]. Similarly, lnc-Tim3 directly binds to Tim-3 protein, preventing its interaction with Bat3 and consequently inhibiting downstream signaling in the Lck/NFAT1/AP-1 pathway, which contributes to T cell exhaustion [3].

CircRNAs also contribute significantly to immune regulation in HCC. Tumor-derived exosomes can deliver circRNAs to immune cells, influencing their function and promoting immune evasion [4]. For example, exosomal circ-0001068 from ovarian cancer cells enters T cells and upregulates PD-1 expression by sponging miR-28-5p, leading to T cell exhaustion [4]. Similarly, circRNA-002178 from lung adenocarcinoma can be transferred to CD8+ T cells via exosomes and upregulate PD-1 through miR-34a sponging [4]. Beyond T cells, circRNAs regulate other immune populations including natural killer cells and macrophages, further shaping the immunosuppressive HCC microenvironment [4].

Angiogenesis and Matrix Remodeling

ncRNAs play crucial roles in promoting tumor angiogenesis and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling in HCC. Multiple circRNAs regulate angiogenesis through the ceRNA network, with VEGF being a primary target [8]. For instance, circARF1 in glioblastoma stem cells upregulates ISL2 expression by sponging miR-342-3p, which in turn regulates VEGFA expression and promotes endothelial cell proliferation through the VEGFA-mediated ERK signaling pathway [8]. circRNAs also contribute to ECM remodeling by regulating the expression of collagen proteins (COL5A1, COL1A1) and other ECM components in various cancers, processes that are similarly relevant to HCC progression [8].

Table 3: ncRNA Dysregulation in HCC Tumor Microenvironment

| ncRNA | Class | Expression in HCC | Target/Mechanism | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEAT1 | lncRNA | Upregulated | miR-155/Tim-3 pathway | CD8+ T cell apoptosis, reduced cytolytic activity [3] |

| lnc-Tim3 | lncRNA | Upregulated | Binds Tim-3, disrupts Bat3 interaction | T cell exhaustion [3] |

| circ-0001068 | circRNA | Upregulated (exosomal) | miR-28-5p/PD-1 axis | T cell exhaustion [4] |

| circRNA-002178 | circRNA | Upregulated (exosomal) | miR-34a/PD-1 axis | CD8+ T cell exhaustion [4] |

| circARF1 | circRNA | Upregulated | miR-342-3p/ISL2/VEGFA | Angiogenesis promotion [8] |

Experimental Approaches and Research Reagents

Methodologies for ncRNA Research

Advanced technologies have been developed to identify, characterize, and functionally validate ncRNAs. High-throughput RNA sequencing, particularly with ribosomal RNA depletion protocols, enables comprehensive profiling of lncRNA and circRNA expression patterns [8] [4]. For circRNA identification, treatment with RNase R (which degrades linear RNAs but not circRNAs) followed by RNA sequencing provides a robust approach to enrich and detect circular transcripts [4]. Cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) methods, particularly HITS-CLIP and PAR-CLIP, allow researchers to map the interactions between ncRNAs and RNA-binding proteins or between miRNAs and their targets [6]. Functional characterization typically involves loss-of-function approaches using RNA interference or CRISPR-based systems, and gain-of-function studies through plasmid-based overexpression or synthetic RNA delivery [3]. For circRNA-specific manipulation, algorithms that target the back-splicing junction are particularly effective [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ncRNA Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitors | RNaseOUT, SUPERase•In | Protect RNA during processing and analysis |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq Small RNA Library Prep Kit, SMARTer smRNA-Seq Kit | Sequencing library construction for different ncRNA classes |

| Enrichment Reagents | RNase R | Circular RNA enrichment by degrading linear RNAs |

| Detection Assays | qRT-PCR assays with divergent primers | circRNA-specific detection and quantification |

| Functional Tools | Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) inhibitors, siRNA, shRNA, CRISPR-Cas9 systems | ncRNA knockdown and functional characterization |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid nanoparticles, viral vectors | Introduction of ncRNA mimics/inhibitors into cells |

| Exosome Isolation | Total Exosome Isolation Kits, ultracentrifugation protocols | Study of extracellular ncRNAs and their transfer mechanisms |

Concluding Perspectives

The intricate networks formed by miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs represent a critical regulatory layer in hepatocellular carcinoma biology, with particular significance for understanding and therapeutically targeting the tumor microenvironment. The ceRNA hypothesis provides a framework for understanding how these different ncRNA classes communicate to fine-tune gene expression patterns that drive HCC progression and immune evasion. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the specific molecular mechanisms by which individual ncRNAs function within the HCC TME, developing more sophisticated models to study ncRNA interactions, and translating this knowledge into novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. As technologies for ncRNA detection and manipulation continue to advance, targeting these molecules holds significant promise for improving outcomes in HCC and other cancers characterized by ncRNA dysregulation.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a major global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [9]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) has emerged as a critical determinant of HCC progression, therapeutic resistance, and patient outcomes. The HCC TME comprises a complex network of cellular components, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and infiltrating immune cells, alongside non-cellular factors such as extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, cytokines, and angiogenic mediators [9]. These elements collectively promote immune evasion, stromal remodeling, and neovascularization, driving tumor aggressiveness [9]. Hypoxia, a pivotal characteristic of the HCC TME, is intimately linked to disease progression and unfavorable patient outcomes [10]. This in-depth technical guide examines the core components of the HCC TME and hypoxic niches within the broader context of non-coding RNA dysregulation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with current insights and methodologies for investigating this complex ecosystem.

Cellular Architecture of the HCC TME

The HCC TME features a highly organized cellular architecture where stromal and immune components interact dynamically with malignant hepatocytes. The table below summarizes the key cellular constituents, their origins, markers, and protumorigenic functions.

Table 1: Key Cellular Components of the HCC Tumor Microenvironment

| Cell Type | Origin | Key Markers | Major Protumorigenic Functions | Regulation by ncRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), portal fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells | α-SMA, FAP, COL1A1, COL1A2 [11] | ECM remodeling, secretion of growth factors (CXCL11, CCL5), recruitment of immunosuppressive cells (MDSCs, Tregs), promotion of angiogenesis via VEGF/PDGF [9] | miR-1228-3p delivered via exosomes promotes immune evasion [9] |

| Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) | Circulating monocytes, tissue-resident Kupffer cells | CD163, CD206, VEGF, ARG1 [11] | M2 polarization promotes immunosuppression via IL-4, IL-10, IL-13; angiogenesis via VEGF; tissue remodeling [12] [11] | Exosomal miR-3184-3p induces M2-like polarization [6] |

| Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) | Immature myeloid cells | STAT3, NF-κB [11] | Expansion driven by GM-CSF, IL-6, VEGF; suppression of T cell function, promotion of Treg expansion [11] | Not specified in search results |

| Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) | CD4+ T cell differentiation | FOXP3, CD25, CTLA-4 [11] | Enforcement of immune tolerance via TGF-β and IL-2 signaling; recruitment via CCL22/CCL28 chemokines [11] | Lnc-Tim3 binding to Tim-3 modulates T cell activity [3] |

| CD8+ T Lymphocytes | Thymic development | PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3, LAG-3 [11] | Functional exhaustion characterized by upregulated inhibitory receptors and loss of effector cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α) [11] | NEAT1 regulates apoptosis and cytolytic activity via miR-155/Tim-3 pathway [3] |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells | Hematopoietic stem cells | NKG2D, DNAM-1 [11] | Impaired cytotoxicity due to downregulation of activating receptors (NKG2D, DNAM-1) mediated by TGF-β and adenosine [11] | Not specified in search results |

CAFs are the predominant stromal population, accounting for 50-70% of TME cells [9]. Their activation primarily occurs through transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) stimulated by cytokines including TGF-β and PDGF [9]. Activated CAFs promote HCC metastasis through CCL5-mediated activation of the HIF1α/ZEB1 axis and directly enhance tumor proliferation via CXCL11 secretion [9]. The immune landscape within the HCC TME demonstrates significant heterogeneity, with high infiltration of MDSCs and Tregs associated with poor prognosis, while robust presence of activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes and NK cells correlates with better patient outcomes [12].

Hypoxic Niches in HCC

Hypoxia is a fundamental characteristic of the HCC TME, with oxygen tension (PaO2) decreasing from approximately 33 mmHg in normal liver tissue to as low as 6 mmHg in HCC tissues [10]. This hypoxic niche drives aggressive tumor behavior through multiple interconnected mechanisms.

Molecular Mediators of Hypoxia

The cellular response to hypoxia is primarily mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), particularly the HIF-1α subunit, which promotes tumor growth, metastasis, and therapy resistance [10]. Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses have identified distinct hypoxia subpopulations within HCC with significant overexpression of genes including MEG3, KLF6, and JUN [10]. Research has revealed that hypoxia induces epigenetic modifications such as m6A RNA demethylation, with HIF-1α binding to the promoter region of ALKBH5 (an m6A demethylase), thereby upregulating its expression and enhancing the stability of pro-tumorigenic transcripts like Galectin-1 [13].

Functional Consequences of Hypoxia

Hypoxia triggers multifaceted adaptations in the HCC TME:

- Angiogenesis: HIF-1α enhances angiogenesis through regulation of VEGF, driving the formation of abnormal tumor vasculature [10].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: Hypoxia induces metabolic changes that reduce ROS levels in TKI-treated HCC, contributing to drug resistance [10].

- Immunosuppression: Alterations in metabolite levels (glucose, lactate, adenosine) within the hypoxic TME collectively foster an immunosuppressive milieu that significantly hinders the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors [10].

- Invasion and Metastasis: Hypoxic conditions promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and facilitate the formation of premetastatic niches (PMN) through exosome-mediated communication [10].

Diagram 1: Hypoxia signaling cascade in HCC. This diagram illustrates the central role of HIF-1α in mediating cellular responses to hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis, epigenetic modification, metastasis, and drug resistance. Created with DOT language.

Non-Coding RNA Dysregulation in the HCC TME

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression and cellular processes in the HCC TME, functioning as key intermediaries between hypoxic stress and tumor progression.

ncRNA Biogenesis and Classification

ncRNAs comprise several distinct classes:

MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Approximately 22 nucleotides long, single-stranded RNAs that regulate gene expression by binding to specific sequences in target mRNAs, leading to degradation, destabilization, or translational repression [6]. MiRNA biogenesis involves sequential processing from primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) to precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) and finally to mature miRNA, which associates with Argonaute proteins to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [6].

Long Non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs): RNA molecules exceeding 200 nucleotides that regulate gene expression through diverse mechanisms including transcriptional regulation, epigenetic modification, microRNA sponging, and splicing regulation [6] [3]. LncRNAs form complex secondary structures that enable specific molecular interactions.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs): A more recently characterized class of ncRNAs that form covalently closed continuous loops, often functioning as miRNA sponges or protein decoys [6].

Functional Roles of ncRNAs in TME Regulation

ncRNAs modulate the HCC TME through several key mechanisms:

Table 2: ncRNA-Mediated Regulation of the HCC Tumor Microenvironment

| ncRNA Class | Representative Molecules | Regulatory Targets/Mechanisms | Functional Outcomes in HCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNAs | miR-1228-3p, miR-3184-3p, miR-155 | Target mRNA degradation/translational repression; delivered via exosomes [9] [6] | CAF-mediated immune evasion; macrophage polarization; T cell exhaustion |

| lncRNAs | NEAT1, lnc-Tim3, TUG1, LINC01116, CRNDE | miRNA sponging, chromatin remodeling, protein interactions [3] [14] | Regulation of T cell activity (via miR-155/Tim-3); modulation of autophagy; immune checkpoint regulation |

| circRNAs | circPS-MA1 | Activation of miR-637/Akt1/β-catenin axis [6] | Promotion of tumorigenesis, metastasis, and migration |

lncRNAs have been shown to regulate autophagy in HCC through integration into key signaling networks such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR, AMPK, and Beclin-1 pathways [14]. This regulatory function positions lncRNAs as critical modulators of the cellular stress response in the TME. The formation and function of lncRNAs involve transcription by RNA polymerase II, followed by processing including 5' capping, 3' polyadenylation, and splicing to generate mature transcripts that function in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments [3].

Experimental Methodologies for TME Investigation

Advanced technological approaches have enabled comprehensive dissection of the HCC TME at unprecedented resolution. The following experimental protocols represent cutting-edge methodologies for investigating hypoxic niches and ncRNA dysregulation.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) Workflow

scRNA-seq provides high-resolution analysis of cellular heterogeneity and gene expression patterns within the HCC TME [10].

Protocol: Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of HCC TME

Sample Preparation: Obtain fresh HCC tissue samples (e.g., primary tumors, portal vein tumor thrombi, metastatic lymph nodes) and process immediately to preserve cell viability [10].

Single-Cell Suspension: Dissociate tissue using enzymatic digestion (collagenase/hyaluronidase mixtures) with gentle mechanical disruption. Filter through 40μm strainers to obtain single-cell suspensions.

Cell Viability Assessment: Evaluate viability using trypan blue exclusion or fluorescent viability dyes, maintaining >80% viability for optimal results.

Single-Cell Partitioning: Use microfluidic devices (10X Genomics Chromium system) to partition individual cells with barcoded beads.

Library Preparation: Perform reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library construction following manufacturer protocols. Incorporate unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias.

Sequencing: Conduct high-throughput sequencing on Illumina platforms (recommended depth: 50,000 reads/cell).

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality control: Filter cells with mitochondrial content >20%, hemocyte content >3%, UMI counts 200-50,000, and gene counts 200-8,000 [10].

- Data normalization using Seurat package functions:

NormalizeData,FindVariableFeatures,ScaleData[10]. - Batch effect correction using Harmony algorithm.

- Dimensionality reduction with UMAP and t-SNE algorithms.

- Cell clustering using Louvain algorithm.

- Cell type annotation using marker panels:

- Neoplastic cells: CDH1, EPCAM, KRT18, KRT19

- Fibroblasts: SLRR1B, CD90, COL1A1, COL1A2

- Endothelial cells: CD31, CLDN2, VEGFR-1, RAMP2

- T-cells: CD3D/E/G, IMD7

- Myeloid cells: AMYLD5, SCARA2, CD16, CD68 [10]

Hypoxia Analysis: Identify hypoxic cell populations using specialized computational tools (e.g., CHPF software) that integrate scRNA-seq profiles with hypoxia-induced gene clusters [10].

Intercellular Communication: Analyze ligand-receptor interactions using CellChat package with

computeCommunProb,filterCommunication, andcomputeCommunProbPathwayfunctions [10].

Diagram 2: Single-cell RNA sequencing workflow for HCC TME analysis. Key steps include tissue processing, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis to characterize cellular heterogeneity and hypoxic niches. Created with DOT language.

Hypoxia-Related Prognostic Model Development

The construction of prognostic models based on hypoxia-related genes provides clinically relevant tools for outcome prediction [10].

Protocol: Development of Hypoxia Prognostic Signatures

Data Acquisition: Obtain transcriptomic data and clinical records from public databases (TCGA, ICGC). Convert expression data to TPM format followed by log2 transformation [10].

Hypoxia Cell Identification: Apply computational framework (CHPF software) to single-cell data to identify hypoxic cell populations and their characteristic gene expression patterns [10].

Differential Expression Analysis: Identify genes significantly overexpressed in hypoxic subpopulations (e.g., MEG3, KLF6, JUN) using FindAllMarkers function with thresholds: p-value <0.05, log2 fold change >0.25, expression proportion >0.1 [10].

Transcription Factor Analysis: Utilize SCENIC package with GRNboost2 software to construct gene regulatory networks and identify key transcription factors (e.g., NOP58, MED8) in hypoxic populations [10].

Prognostic Model Construction: Apply machine learning algorithms (LASSO Cox regression) to select most predictive features. Calculate risk scores based on gene expression weighted by regression coefficients.

Model Validation: Validate prognostic performance in independent datasets (e.g., LIRI-JP from ICGC) using survival analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves [10].

ncRNA Functional Characterization

Elucidating the functional roles of specific ncRNAs in the HCC TME requires integrated experimental approaches.

Protocol: Functional Analysis of ncRNA in Hypoxic Niches

ncRNA Identification: Profile ncRNA expression patterns using small RNA-seq for miRNAs and total RNA-seq for lncRNAs/circRNAs from matched normoxic and hypoxic HCC regions.

Hypoxia Manipulation: Culture HCC cells in hypoxic chambers (1% O2) or with chemical hypoxia mimetics (CoCl2, DMOG) for specified durations (6-48 hours).

Loss/Gain-of-Function Studies:

- miRNA modulation: Transfect with miRNA mimics (gain-of-function) or inhibitors (loss-of-function)

- lncRNA/circRNA modulation: Use siRNA/shRNA-mediated knockdown or plasmid-based overexpression

- CRISPR/Cas9 systems for genomic editing of ncRNA loci

Phenotypic Assays:

- Proliferation: CCK-8, EdU incorporation assays

- Invasion: Transwell Matrigel invasion assays

- Angiogenesis: Endothelial tube formation assays using conditioned media

- Immune cell function: Coculture systems with peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Mechanistic Studies:

- miRNA target validation: Dual-luciferase reporter assays with wild-type and mutant 3'UTR constructs

- lncRNA-protein interactions: RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP), RNA pull-down assays

- lncRNA-miRNA sponging: Luciferase-based miRNA target reporters, AGO2-RIP

In Vivo Validation: Utilize orthotopic or subcutaneous xenograft models in immunodeficient mice. Implement ncRNA modulation via lentiviral transduction or nanoparticle-based delivery systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below summarizes key reagents and computational tools for investigating the HCC TME and hypoxic niches.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for HCC TME Investigation

| Category | Reagent/Tool | Specific Application | Function/Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Seurat Package (R) | scRNA-seq data analysis | Data normalization, dimensionality reduction, cell clustering, and visualization [10] |

| CHPF Software | Hypoxia cell identification | Predicts cellular hypoxia conditions by integrating scRNA-seq profiles with hypoxia-induced gene clusters [10] | |

| CellChat Package | Intercellular communication analysis | Infers and analyzes cell-cell communication networks from scRNA-seq data [10] | |

| SCENIC Package | Transcription factor analysis | Constructs gene regulatory networks from scRNA-seq data [10] | |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Harmony Algorithm | Batch effect correction | Corrects for technical variations between different scRNA-seq batches [10] |

| Infercnv Package | Copy number variation analysis | Estimates CNV in tumor cells using endothelial cells as reference [6] | |

| Monocle2 Package | Cell trajectory analysis | Reconstructs cellular developmental trajectories from scRNA-seq data [10] | |

| Cell Culture Models | Hypoxic Chambers | Hypoxia modeling | Creates controlled low-oxygen environments (typically 1-5% O2) for in vitro studies [10] |

| Chemical Hypoxia Mimetics (CoCl2, DMOG) | HIF pathway stabilization | Stabilizes HIF-α subunits under normoxic conditions for hypoxia pathway studies [13] | |

| Therapeutic Agents | LNP-siRNA Formulations | ncRNA modulation in vivo | Enables efficient delivery of RNAi therapeutics to target specific ncRNAs in animal models [13] |

| 1H,2H,3H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]quinoline | 1H,2H,3H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]quinoline, CAS:40041-77-8, MF:C11H10N2, MW:170.215 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-methyl-1,2-thiazol-3-one;hydrate | 2-methyl-1,2-thiazol-3-one;hydrate|133.17 g/mol | 2-methyl-1,2-thiazol-3-one;hydrate (CAS 2089381-44-0) is a biocide preservative for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The HCC tumor microenvironment represents a highly organized ecosystem where cellular components interact within hypoxic niches to drive tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Non-coding RNAs serve as critical regulatory molecules in this ecosystem, mediating the cellular response to hypoxia and coordinating intercellular communication. Advanced methodologies including single-cell RNA sequencing, sophisticated computational algorithms, and functional genomic approaches provide powerful tools for dissecting this complexity. The integration of these technologies with mechanistic studies of ncRNA function offers promising avenues for identifying novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers. Future research should focus on validating specific ncRNA-autophagy axes, developing efficient ncRNA-targeting delivery systems, and exploring combination therapies that simultaneously target malignant cells and modulate the TME. Such integrated approaches hold significant potential for advancing precision medicine in HCC treatment.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a major global health challenge characterized by a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) that plays a pivotal role in tumor progression and therapeutic response [3]. Within this ecosystem, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression, influencing various biological processes despite not encoding proteins themselves [15] [6]. The TME comprises diverse cell types, including tumor cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, all interacting dynamically to influence tumor behavior [3]. Understanding how ncRNAs control gene expression within this microenvironment provides crucial insights into HCC pathogenesis and reveals potential therapeutic targets. This review explores the mechanisms through which different ncRNA classes—including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs)—orchestrate gene expression within the HCC TME, highlighting their roles as both regulators and effectors of tumor progression.

ncRNA Biogenesis and Functional Classes

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

MiRNAs are approximately 22-nucleotide-long, single-stranded ncRNA molecules that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [6]. The biogenesis of miRNAs involves a meticulously controlled multi-step process: RNA polymerase II transcribes primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) containing imperfect hairpin structures from DNA [6]. In the nucleus, the Drosha-DGCR8 complex cleaves these hairpins to produce precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) approximately 60-90 nucleotides long with distinctive 2-nucleotide 3' overhangs [6]. These pre-miRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm by XPO5 protein, where Dicer processes them into double-stranded RNA molecules of 19-22 nucleotides [6]. One strand (the guide strand) incorporates into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), while the passenger strand is typically degraded [6]. The mature RISC complex uses the miRNA as a guide to recognize and bind target mRNAs through base pairing between its seed region (nucleotides 2-8) and specific sequences in the 3' untranslated region or coding region of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation, destabilization, or translational repression [6].

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

LncRNAs are RNA molecules exceeding 200 nucleotides in length that perform essential biological functions despite not coding for proteins [6]. The formation process of lncRNAs involves transcription from genomic DNA by RNA polymerase II, typically adjacent to or independently from protein-coding genes [3]. After transcription, lncRNAs undergo processing, including 5' capping, 3' polyadenylation, and splicing, to reach maturity [3]. Mature lncRNAs can function in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, regulating gene expression through interactions with DNA, RNA, or proteins [3]. Their structural complexity is evident in their ability to form secondary structures like hairpins, stem-loops, and pseudoknots via base pairing, which enhances their morphological diversity and contains conserved short modules crucial for specific functions [6]. For instance, SINEUP lncRNAs feature conserved short structural modules that boost translational enhancement [6].

Circular RNAs (circRNAs)

CircRNAs are produced by non-canonical splicing events that join a splice donor to an upstream splice acceptor, forming continuous closed loops [16]. RNA sequencing studies based on rRNA-depleted libraries have identified that approximately 85.82% of circRNAs originate from exonic regions, while 7.0% and 7.18% come from intergenic and intronic regions, respectively [16]. Notably, about 52.81% of genes produce more than two circRNA isoforms, indicating that alternative circularization extensively occurs in HCC and para-cancerous tissues [16]. These circRNAs can act as key regulators in cancer by regulating transcription or post-transcription of driver genes, often functioning as miRNA sponges or participating in other regulatory mechanisms [16].

Table 1: Major ncRNA Classes and Their Characteristics in HCC

| ncRNA Class | Size Range | Primary Functions | Key Features in HCC | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | ~22 nucleotides | mRNA degradation, translational repression | Frequently dysregulated by epigenetic mechanisms; can act as tumor suppressors or promoters | miR-122 (downregulated), miR-191 (upregulated) [15] |

| lncRNA | >200 nucleotides | Chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, miRNA sponging | Often show copy number variations; regulate immune cell function in TME | NEAT1 (upregulated), FENDRR (downregulated) [15] [3] |

| circRNA | Variable | miRNA sponging, protein sequestration | Formed by back-splicing; highly stable structure; abundant in exosomes | cZRANB1 (upregulated), circTRIM33-12 (downregulated) [15] [16] |

Mechanisms of ncRNA Dysregulation in HCC

Genetic Alterations Driving ncRNA Dysregulation

Copy number variations (CNVs) represent one of the most common genetic alterations affecting ncRNA expression in HCC. Whole-genome sequencing data from 49 Chinese HCC patients revealed that lncRNAs are frequently amplified in HCC tumor tissues, with amplifications predominantly located on chromosomes 1q, 8q, 17q, and 20q [15]. Conversely, lncRNAs deleted in tumor tissues are mostly located on chromosomes 4q, 9q, 13q, and 16q [15]. TaqMan copy number assays of HCC tumors and normal liver tissues from 238 patients further confirmed that lncRNAs with copy number gain in >50% of HCC samples were consistently upregulated in tumor tissues [15]. Specific examples include the tumor suppressor lncRNA TSLNC8, located on chromosome 8p12, which is frequently deleted in HCC tissues [15], and FENDRR, which shows a pattern of decreased expression associated with CNV-driven dysregulation [15].

Epigenetic Modifications Regulating ncRNA Expression

Epigenetic mechanisms, particularly DNA methylation and histone modifications, play crucial roles in ncRNA dysregulation in HCC. DNA methylation of CpG islands within promoter regions can silence tumor suppressor miRNAs, while DNA hypomethylation can activate oncogenic miRNAs [15]. For instance, the CpG island of miR-1 is methylated in HCC cells (HepG2 and Hep3B) and tissues, with lower miR-1 expression in HCC tissues compared to normal liver tissues [15]. Treatment with the DNA hypomethylating agent 5-azacytidine restores miR-1 expression in HCC cells [15]. Conversely, hypomethylation of the CpG islands of miR-191 and miR-519d leads to their upregulated expression, enhancing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in HCC [15].

Histone modifications also significantly contribute to ncRNA dysregulation. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), an essential enzymatic unit of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), promotes H3K27me3, leading to the silencing of genes by interacting with miRNA promoters [15]. PRC2 mediates the downregulation of tumor suppressive miRNAs, including miR-101-1, miR-9, and miR-144/451a, by interacting with EZH2 in HCC [15]. Additionally, histone deacetylases (HDACs) contribute to ncRNA dysregulation, as demonstrated by HDAC9 and HDAC10 recruitment to the miR-223 promoter, where deacetylation contributes to miR-223 downregulation [15]. Similarly, HDAC3-mediated histone deacetylation regulates miR-195 expression [15].

Table 2: Epigenetic Regulation of ncRNAs in HCC

| Epigenetic Mechanism | Effect on ncRNAs | Regulatory Factors | Example ncRNAs | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Hypermethylation | Silencing of tumor suppressor ncRNAs | DNA methyltransferases | miR-1 [15] | Reduced expression; promotes tumor progression |

| DNA Hypomethylation | Activation of oncogenic ncRNAs | Demethylating agents | miR-191, miR-519d [15] | Increased expression; enhances EMT |

| H3K27me3 | Transcriptional repression | EZH2/PRC2 complex | miR-101-1, miR-9, miR-144/451a [15] | Silencing of tumor suppressors |

| Histone Deacetylation | Gene silencing | HDAC9, HDAC10, HDAC3 | miR-223, miR-195 [15] | Downregulation of tumor suppressive miRNAs |

| H3K27ac/H3K4me3 | Transcriptional activation | EP300, WDR5 | circSOD2 [15] | Enhanced expression; tumor promotion |

Functional Mechanisms of ncRNAs in the TME

Regulation of Immune Cell Function

Within the HCC TME, ncRNAs critically regulate the infiltration and function of various immune cells. The immune landscape of HCC features diverse immune cell populations, including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), with the balance between these cell types determining anti-tumor immune effectiveness [3]. LncRNAs have emerged as important regulators of these immune cells, influencing both pro-tumor and anti-tumor activities [3].

T cell regulation represents a key mechanism through which lncRNAs modulate the immune microenvironment. Several oncogenic lncRNAs, including TUG1, LINC01116, CRNDE, MIAT, E2F1, LINC01132, and Lnc-Tim3, are overexpressed in HCC and influence T cell activity through various pathways [3]. For instance, NEAT1 and Tim-3 are significantly upregulated in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of HCC patients [3]. Downregulation of NEAT1 inhibits CD8+ T cell apoptosis and enhances their cytolytic activity against HCC cells by regulating the miR-155/Tim-3 pathway [3]. Similarly, Lnc-Tim3 specifically binds to Tim-3, preventing its interaction with Bat3 and thereby modulating downstream signaling in T cells [3].

Myeloid cell populations are also regulated by ncRNAs within the TME. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) can be polarized toward M2-like immunosuppressive phenotypes under the influence of specific ncRNAs [6]. In gliomas, exosomes enriched with miR-3184-3p from cerebrospinal fluid not only boost glioma progression but also induce M2-like macrophage polarization, enhancing tumor aggression [6]. Although this specific example comes from glioma research, similar mechanisms likely operate in HCC, given the conserved nature of ncRNA-mediated regulation across different cancer types.

ceRNA Networks and miRNA Sponging

The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis describes a mechanism through which different RNA species cross-regulate each other by competing for shared miRNA response elements. This network creates a complex regulatory system where lncRNAs, circRNAs, and mRNAs communicate through miRNA sponging [16]. In HCC, integrative analyses have uncovered specific ceRNA networks where circRNAs and lncRNAs function as miRNA sponges, regulating mRNA expression by competing for shared miRNAs [16]. For instance, cZRANB1, LINC00501, CTD-2008L17.2, and SLC7A11-AS1 may function as ceRNAs that regulate mRNAs by competing for shared miRNAs [16].

CircRNAs are particularly effective as miRNA sponges due to their stable circular structure and abundance of miRNA binding sites. The deregulation of specific circRNAs in HCC, such as the downregulation of circTRIM33-12, which serves as an independent risk factor for overall survival, highlights their importance in HCC pathogenesis [15]. Similarly, transcriptome sequencing has identified circRNA cZRANB1 as significantly upregulated not only in tumor tissues but also in blood exosomes of HCC patients compared with healthy donors, suggesting its potential as both a functional regulator and biomarker [16].

Regulation of Autophagy in the TME

The lncRNA-autophagy axis represents another crucial mechanism through which ncRNAs influence the HCC TME. Autophagy plays a paradoxical role in HCC, acting as a tumor suppressor during initiation but promoting survival and progression in advanced stages [14]. LncRNAs have emerged as critical regulators of autophagy, influencing tumorigenesis, metastasis, and therapy resistance through mechanisms such as miRNA sponging, chromatin remodeling, and protein interactions [14].

LncRNAs integrate into key signaling networks regulating autophagy, including the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, AMPK, and Beclin-1 pathways [14]. For instance, under nutrient deprivation conditions, AMPK activates ULK1 while inhibition of mTORC1 relieves its suppressive effect, resulting in ULK1 phosphorylating downstream autophagy-related proteins and initiating production of autophagic vesicles [14]. The PI3K complex, which includes VPS34 and Beclin-1, is essential for the nucleation of the phagophore—the initial membrane structure that gives rise to the autophagosome [14]. LncRNAs can modulate these pathways at multiple levels, thereby altering autophagic flux and associated molecular pathways that contribute to drug resistance, including resistance to first-line agents [14].

Experimental Approaches and Research Toolkit

Transcriptome Analysis Methodologies

Comprehensive transcriptome profiling utilizing next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has been instrumental in characterizing ncRNA dysregulation in HCC. The standard workflow for ncRNA detection and quantification involves parallel sequencing approaches for different ncRNA species [16]. For miRNA analysis, small RNA sequencing detects mature miRNAs annotated by miRBase and novel miRNAs identified by miRDeep2 [16]. For lncRNA and circRNA analysis, rRNA depletion-based total RNA sequencing enables the detection of both linear and circular transcripts, with circRNA prediction performed by tools such as CIRI2 [16].

Differential expression analysis typically involves quantifying ncRNAs at a count-based level and applying statistical tests to identify ncRNAs differentially expressed between HCC and para-cancerous tissues, using thresholds such as adjusted p-value <0.1 and fold-change >2 or <1/2 [16]. Validation in independent datasets is crucial, with studies reporting that approximately 65% of dysregulated lncRNAs, 76% of circRNAs, and 62% of miRNAs identified in discovery cohorts can be validated in independent patient cohorts [16].

Functional Validation Techniques

Functional characterization of ncRNAs requires a multi-faceted experimental approach. Gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies using techniques such as siRNA, shRNA, or CRISPR/Cas systems enable researchers to investigate the functional consequences of ncRNA modulation [14]. For instance, downregulation of NEAT1 has been shown to inhibit CD8+ T cell apoptosis and enhance their cytolytic activity against HCC cells, demonstrating its functional role in immune regulation [3].

Mechanistic insights often require additional techniques, including:

- RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) and CLIP-seq to identify protein interaction partners

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to study epigenetic regulation

- Luciferase reporter assays to validate direct miRNA-mRNA or miRNA-ncRNA interactions

- Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to determine subcellular localization

- Exosome isolation and characterization to study ncRNA secretion and intercellular communication

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Small RNA sequencing, rRNA-depleted RNA sequencing | Comprehensive ncRNA profiling | Library preparation method affects ncRNA detection; validation required |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CIRI2 (circRNA prediction), miRDeep2 (miRNA prediction) | ncRNA identification and quantification | Multiple algorithms recommended for improved accuracy |

| Functional Modulation | siRNA, shRNA, CRISPR/Cas systems, ASOs | Gain/loss-of-function studies | Delivery efficiency and specificity crucial for interpretation |

| Interaction Studies | RIP, CLIP-seq, Luciferase reporter assays | Mechanistic validation | Controls essential for distinguishing direct vs. indirect effects |

| Localization Studies | FISH, Subcellular fractionation | Determining ncRNA localization | Critical for understanding mechanism of action |

| 3-Benzoylbenzenesulfonyl fluoride | 3-Benzoylbenzenesulfonyl Fluoride|Covalent Probe | Bench Chemicals | |

| 3-Hydroxy-2-isopropylbenzonitrile | 3-Hydroxy-2-isopropylbenzonitrile, CAS:1243279-74-4, MF:C10H11NO, MW:161.204 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Concluding Remarks

The intricate mechanisms through which ncRNAs control gene expression in the HCC TME represent a rapidly advancing field with significant implications for both basic cancer biology and clinical translation. The dysregulation of ncRNAs through genetic and epigenetic mechanisms creates widespread effects on gene regulatory networks that ultimately shape the immunosuppressive TME characteristic of HCC. Understanding these mechanisms provides not only fundamental insights into HCC pathogenesis but also reveals novel therapeutic targets and biomarker opportunities.

The future of ncRNA research in HCC will likely focus on developing technologies to specifically target oncogenic ncRNAs while restoring tumor-suppressive ncRNAs, potentially through antisense oligonucleotides, small molecule inhibitors, or RNA-based therapeutics. Additionally, the exploration of exosomal ncRNAs as both therapeutic vehicles and diagnostic biomarkers represents a promising frontier. As our understanding of the complex ncRNA regulatory networks in the TME deepens, so too will our ability to develop effective ncRNA-based interventions for this devastating malignancy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the predominant form of primary liver cancer, represents a major global health challenge characterized by high mortality and limited therapeutic options for advanced disease [17] [3]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) of HCC plays a pivotal role in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance, with intratumoral hypoxia emerging as a critical hallmark [18] [19]. This hypoxic state originates from an imbalance between oxygen supply and consumption by rapidly proliferating tumor cells [19] [20]. In response to oxygen deprivation, cancer cells activate sophisticated genetic programs masterfully orchestrated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), the principal transcriptional regulator of cellular adaptation to hypoxia [18] [21].

HIF-1α exerts extensive influence over hypoxic gene expression and signaling networks, modulating processes including metabolism, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, and resistance to therapy [19] [22]. Meanwhile, advances in transcriptome analysis have revealed that non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—once considered transcriptional "noise"—occupy more than 95% of the human transcriptome and play critical regulatory roles in cancer pathogenesis [19] [20]. These ncRNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), have emerged as crucial components in the hypoxic response of HCC tumors [18] [23].

This review comprehensively examines the intricate reciprocal regulation between HIF-1α and ncRNAs in HCC, focusing on their collective impact on tumorigenic processes, the potential of hypoxia-responsive ncRNAs as clinical biomarkers, and the therapeutic implications of targeting these regulatory networks in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Molecular Mechanisms of HIF-1α Regulation and Function

Oxygen-Dependent Regulation of HIF-1α Stability

Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α undergoes rapid proteasomal degradation through an oxygen-sensitive mechanism [19] [22]. Prolyl hydroxylase domain enzymes (PHDs) utilize oxygen to hydroxylate conserved proline residues (Pro-402 and Pro-564) within the HIF-1α protein [19] [20]. This hydroxylation event enables the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein to recognize HIF-1α as a substrate for ubiquitination, marking it for proteasomal destruction [19] [22]. Additionally, the transcriptional activity of HIF-1α is regulated by factor inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH-1), which hydroxylates an asparagine residue in the C-terminal transactivation domain, blocking its interaction with transcriptional coactivators CBP/p300 [19] [20].

In hypoxic conditions, oxygen deprivation halts the hydroxylation activities of both PHDs and FIH-1, leading to HIF-1α stabilization [19]. The stabilized HIF-1α protein translocates to the nucleus, dimerizes with HIF-1β, and recruits the CBP/p300 coactivator complex [19] [22]. This heterodimeric complex then binds to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) containing the core consensus sequence 5'-RCGTG-3' in the promoter regions of target genes, initiating a transcriptional program that facilitates cellular adaptation to hypoxia [19] [22].

HIF-1α-Mediated Transcriptional Programs in HCC

HIF-1α activation drives the expression of numerous genes implicated in key cancer hallmarks [18]. In HCC, this includes genes promoting angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF), metabolic reprogramming (e.g., glycolytic enzymes), invasion and metastasis (e.g., EMT transcription factors), and stemness maintenance [18] [19]. More than one thousand target genes have been reported to be regulated by HIF-1α to mediate hypoxic phenotypes, with hypoxia-responsive ncRNAs representing an especially noteworthy group [19] [20].

Figure 1: HIF-1α Regulation and Transcriptional Activation in Hypoxic HCC Microenvironment. Under normoxia, PHD enzymes hydroxylate HIF-1α, leading to VHL-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. During hypoxia, HIF-1α stabilizes, translocates to the nucleus, dimerizes with HIF-1β, and binds to HREs to activate transcription of genes driving cancer hallmarks and hypoxia-responsive ncRNAs.

HIF-1α-Regulated Non-Coding RNAs in HCC

Classification and Mechanisms of Hypoxia-Responsive ncRNAs

Hypoxia-responsive ncRNAs (HRNs) can be categorized based on their regulatory relationships with HIF-1α [19]. In direct regulation, HIF-1α binds directly to HREs within the promoter regions of ncRNA genes to transactivate their expression [19] [20]. In indirect regulation, HIF-1α induces ncRNA expression through intermediate mechanisms, often involving epigenetic modifications mediated by histone deacetylases (HDACs) or other chromatin-modifying enzymes [19]. The major classes of HRNs in HCC include:

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Small ncRNAs (~22 nucleotides) that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or degradation [19] [6].

- Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs): Transcripts >200 nucleotides that regulate gene expression through chromatin modification, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional mechanisms [19] [3].

- Circular RNAs (circRNAs): Covalently closed circular molecules that function as miRNA sponges, protein decoys, or translational regulators [23] [22].

HIF-1α-Regulated microRNAs in HCC

miR-210: The Master HypoxamiR

Among hypoxia-responsive miRNAs, miR-210 stands out as the most consistently and strongly induced miRNA across multiple cancer types, including HCC [19] [20]. HIF-1α directly binds to HREs in the miR-210 promoter, driving its expression under hypoxic conditions [20]. In HCC, miR-210 promotes proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, and reduces radiosensitivity by targeting apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 3 (AIFM3) [19]. It also enhances migration and invasion by regulating vacuole membrane protein 1 (VMP1) [19]. The table below summarizes key hypoxia-regulated miRNAs in HCC and their functional roles.

Table 1: HIF-1α-Regulated MicroRNAs in HCC and Their Functional Roles

| miRNA | Regulation by Hypoxia | Target Genes | Functional Outcomes in HCC | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-210 | Upregulated | AIFM3, VMP1 | Promotes proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, enhances migration and invasion, reduces radiosensitivity | [19] |

| miR-21 | Upregulated | PTEN | Promotes colony formation, invasion, and migration | [19] |

| miR-382 | Upregulated | PTEN | Promotes proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis | [19] |

| miR-224 | Upregulated | RASSF8 | Promotes growth, migration, and invasion | [19] |

| miR-145 | Upregulated | N.A. | Promotes apoptosis | [19] |

Other Hypoxia-Regulated miRNAs

Beyond miR-210, numerous other miRNAs respond to hypoxic signaling in HCC. For instance, miR-21 is transcriptionally activated by HIF-1α and targets PTEN, thereby promoting colony formation, invasion, and migration in lung cancer models, with similar mechanisms likely operational in HCC [19]. miR-382 upregulation under hypoxia targets PTEN to promote proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis in gastric cancer, suggesting potential conserved functions in HCC [19]. The consistent targeting of tumor suppressors like PTEN by multiple hypoxia-induced miRNAs highlights the strategic importance of these regulatory networks in promoting HCC progression.

HIF-1α-Regulated Long Non-Coding RNAs in HCC

Oncogenic lncRNAs in the Hypoxic Niche

Several lncRNAs have been identified as critical mediators of HIF-1α-driven oncogenesis in HCC. The lncRNA HEIH (upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma) demonstrates elevated expression in HCC tissues and functions as an oncogene [24]. HEIH primarily localizes to the cytoplasm but also accumulates in the nucleus, where it interacts with enhancer of Zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) to suppress cell cycle regulators including p15, p16, p21, and p57, facilitating cell cycle progression [24].

The lncRNA UCA1 has been shown to promote glycolysis, proliferation, and metastasis in HCC under hypoxic conditions by interacting with and stabilizing HIF-1α protein, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies hypoxic responses [21]. Similarly, linc01132 and linc01116 are upregulated in HCC and contribute to immune evasion by modulating T cell activity within the TME [3].

Tumor-Suppressive lncRNAs Repressed by Hypoxia

Some lncRNAs function as tumor suppressors that are downregulated under hypoxic conditions. For example, MEG3 expression is reduced in HCC and associated with poor prognosis [21]. Restoration of MEG3 expression suppresses HIF-1α signaling and inhibits HCC growth, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic agent [21]. The dynamic balance between oncogenic and tumor-suppressive lncRNAs under hypoxia significantly influences HCC progression and therapeutic responses.

HIF-1α-Regulated Circular RNAs in HCC

While less characterized than miRNAs and lncRNAs, circRNAs are emerging as important players in the hypoxic HCC microenvironment. Several circRNAs are dysregulated in HCC and contribute to tumor progression through diverse mechanisms [23] [22]. For instance, circIPP2A2 is upregulated by the HIF-1α-induced writer protein METTL1, which catalyzes N7-methylguanosine (m7G) modification, promoting HCC progression [17]. Other circRNAs function as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) that sequester miRNAs, preventing them from binding to their target mRNAs [23] [22].

Table 2: RNA Methylation Modifications in HCC and Their Hypoxia Connections

| Methylation Type | Writer Proteins | Eraser Proteins | Reader Proteins | Regulation by Hypoxia | Functional Impact in HCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A | METTL3, METTL14, WTAP | FTO, ALKBH5 | IGF2BP1, YTHDF1 | HIF-1α influences expression of writers/erasers | METTL3 promotes HCC via inhibiting RDM1 transcription and promoting USP7 translation; METTL14 reduces HCC progression |

| m5C | NSUN2, NSUN5 | - | ALYREF, YBX1 | Potential indirect regulation | NSUN2 promotes HCC via increasing H19 stability; NSUN5 increases ZBED3 expression |

| m7G | METTL1, WDR4 | - | - | METTL1 upregulated by HIF-1α | METTL1 promotes HCC via increasing circIPP2A2 expression |

| m1A | TRM6/TRM61A | ALKBH3 | - | Potential indirect regulation | TRM6/TRM61A promotes HCC via promoting PPARδ translation |

Regulatory Feedback: ncRNAs Modulating HIF-1α Expression and Activity

The interplay between HIF-1α and ncRNAs extends beyond HIF-1α-mediated regulation to include extensive feedback mechanisms wherein ncRNAs modulate HIF-1α expression and activity at multiple levels.

Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Regulation of HIF-1α by ncRNAs

Several miRNAs directly target HIF-1α mRNA for degradation or translational repression. For example, miR-199a-5p has been shown to directly bind to the 3' untranslated region (3'UTR) of HIF-1α mRNA, reducing its stability and translation in cancer cells [22]. Similarly, miR-17-5p and miR-20a members of the miR-17-92 cluster, target HIF-1α mRNA, creating a negative feedback loop that fine-tunes hypoxic responses [22].

LncRNAs also participate in regulating HIF-1α expression. The lncRNA H19 is induced by hypoxia and promotes HIF-1α protein synthesis by acting as a competing endogenous RNA for miRNAs that target HIF-1α [21]. Conversely, the lncRNA MEG3 suppresses HIF-1α signaling by promoting its degradation or inhibiting its transcriptional activity [21].

Post-Translational Regulation of HIF-1α by ncRNAs

ncRNAs significantly influence HIF-1α protein stability and transcriptional activity through regulation of its modifying enzymes. Multiple miRNAs target the 3'UTRs of PHD enzymes, affecting their expression and consequently HIF-1α stability [22]. For instance, miR-31 directly targets PHD3, leading to enhanced HIF-1α stabilization under moderate hypoxia [22].

Additionally, epi-miRNAs—miRNAs that target epigenetic regulators—indirectly influence HIF-1α activity. miR-137 targets lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), an epigenetic modifier that stabilizes HIF-1α and facilitates expression of glycolytic genes such as hexokinase [23]. Through these multifaceted regulatory mechanisms, ncRNAs establish complex feedback loops that precisely calibrate the hypoxic response in HCC.

Functional Outcomes of HIF-1α-ncRNA Interplay in HCC Pathogenesis

Metabolic Reprogramming

The Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) represents a cornerstone of cancer metabolism that is profoundly influenced by HIF-1α-ncRNA interactions [23]. HIF-1α directly transactivates genes encoding glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes, while ncRNAs provide additional layers of regulation. For example, miR-143 and miR-34a regulate key enzymes in glucose metabolism and the TCA cycle [23]. miR-122, frequently downregulated in HCC, suppresses glycolysis and lipid metabolism by targeting pyruvate kinase and fatty acid synthase (FASN) [23].

LncRNAs such as UCA1 enhance glycolytic flux by stabilizing HIF-1α and increasing its binding to promoters of glycolytic genes [21]. Circular RNAs contribute to metabolic reprogramming through their sponge functions; for instance, circPS-MA1 activates the miR-637/Akt1/β-catenin (cyclin D1) axis, promoting tumorigenesis and metabolism in triple-negative breast cancer, with similar mechanisms likely in HCC [6].

Immune Evasion and Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment

The hypoxic HCC microenvironment shapes immune cell function and promotes immune evasion through HIF-1α-ncRNA networks [3] [24]. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) accumulate in hypoxic regions, suppressing effector T cell function [3]. Multiple lncRNAs regulate this process; for example, NEAT1 and Tim-3 are significantly upregulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HCC patients [3]. Downregulation of NEAT1 inhibits CD8+ T cell apoptosis and enhances their cytolytic activity against HCC cells by regulating the miR-155/Tim-3 pathway [3].

LncRNAs also modulate immune checkpoint expression. Lnc-Tim3 binds to Tim-3, preventing its interaction with Bat3 and thereby inhibiting downstream signaling in the Lck/NFAT1/AP-1 pathway, ultimately contributing to T cell exhaustion [3]. Similarly, HEIH influences PD-L1 expression and T cell function in the HCC microenvironment, promoting immune evasion [24].

Angiogenesis, Invasion, and Metastasis

HIF-1α is the master regulator of tumor angiogenesis, primarily through induction of VEGF expression [18] [19]. ncRNAs fine-tune this process through multiple mechanisms. For instance, miR-210 promotes angiogenesis by targeting FGFRL1, E2F3, VMP1, RAD52, and SDHD in lung cancer models [19]. miR-382 also promotes angiogenesis in gastric cancer through PTEN targeting [19].

Invasion and metastasis are enhanced through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process regulated by both HIF-1α and ncRNAs. In gastric cancer, miR-210 mediates HIF-1α-induced EMT by regulating homeobox A9 (HOXA9) expression [20]. Similarly, in prostate cancer, miR-210 promotes EMT, invasion, and migration by targeting TNIP1 and SOCS1 [19]. LncRNAs such as UCA1 and HEIH further contribute to metastatic progression by enhancing cell motility and invasion capabilities [21] [24].

Experimental Approaches for Studying HIF-1α-ncRNA Interactions

Methodologies for Investigating Hypoxia-ncRNA Networks

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying HIF-1α-ncRNA Interactions in HCC. The schematic outlines key methodological approaches from hypoxia induction to therapeutic testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying HIF-1α-ncRNA Interactions in HCC

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia Inducers | Cobalt chloride (CoClâ‚‚), Deferoxamine (DFO), Hypoxia chambers (1% Oâ‚‚) | Mimicking tumor hypoxia in vitro | CoClâ‚‚ and DFO are chemical inducers; hypoxia chambers provide physiological oxygen levels |

| HIF-1α Modulators | PHD inhibitors (FG-4592), HIF-1α stabilizers, EZN-2968 (HIF-1α antagonist) | Manipulating HIF-1α activity | Specificity and off-target effects should be controlled |

| Gene Expression Analysis | RNA-seq kits, miRNA/qPCR arrays, Northern blot reagents | Profiling ncRNA expression under hypoxia | Normalization to appropriate housekeeping genes is critical |

| HIF-1α Binding Assays | ChIP-seq kits, HIF-1α antibodies, HRE luciferase reporters | Validating direct HIF-1α regulation of ncRNAs | Antibody specificity crucial for ChIP experiments |

| Functional Validation | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, siRNA/shRNAs, ASOs, ncRNA mimics/inhibitors | Loss/gain-of-function studies | Delivery efficiency and specificity must be optimized |

| Interaction Studies | RIP/qPCR kits, Biotin-labeled probe pulldown, Luciferase reporter vectors | Investigating ncRNA-protein interactions | Appropriate negative controls essential |

| HCC Models | HepG2, Huh7, PLC/PRF/5 cells, Patient-derived organoids, Mouse HCC models | In vitro and in vivo validation | Model selection should reflect specific research questions |

| 4-Methyl-4-chromanecarboxylic acid | 4-Methyl-4-chromanecarboxylic Acid | 4-Methyl-4-chromanecarboxylic acid is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. Explore its applications in organic synthesis and pharmaceutical research. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-acetylphenyl 4-methylbenzoate | 2-acetylphenyl 4-methylbenzoate, CAS:4010-26-8, MF:C16H14O3, MW:254.285 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker Potential

The hypoxia-responsive ncRNA signature in HCC holds significant promise as a source of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [18] [19]. For instance, miR-210 expression correlates with HIF-1α levels and serves as an independent prognostic marker in breast cancer and clear cell renal cell cancer, with similar potential in HCC [19] [20]. High HEIH expression in serum and exosomes of HCC patients makes it a promising non-invasive diagnostic marker [24].

RNA methylation regulators also offer prognostic value in HCC. Elevated METTL3 expression is associated with unfavorable overall survival (OS) in HCC patients, while reduced METTL14 and ZC3H13 expression similarly correlates with poor prognosis [17]. These findings highlight the clinical potential of hypoxia-associated ncRNAs and their regulatory proteins as biomarkers for HCC management.

Therapeutic Targeting of HIF-1α-ncRNA Axes

Targeting HIF-1α-ncRNA networks presents innovative opportunities for HCC therapy. Several approaches show promise:

- Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and RNAi technology: These can be designed to target oncogenic ncRNAs such as HEIH, UCA1, or NEAT1 [24]. ASOs complementary to specific lncRNAs can trigger their degradation or block functional interactions [24].

- CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing: This technology enables precise modification of ncRNA genes or their regulatory elements, offering potential for permanent disruption of oncogenic HIF-1α-ncRNA circuits [24].

- Small molecule inhibitors: Compounds that disrupt the interaction between lncRNAs and their protein partners, such as EZH2 inhibitors for HEIH targeting, represent another strategic approach [24].

- ncRNA mimics: Tumor-suppressive ncRNAs such as MEG3 or miR-199a-5p can be restored using synthetic mimics or expression vectors [21] [22].

Despite these promising approaches, challenges remain in delivery efficiency, tissue specificity, and potential toxicity, necessitating further development of targeted delivery systems such as lipid nanoparticles or ligand-conjugated formulations [6] [24].

Enhancing Response to Existing Therapies

Modulating HIF-1α-ncRNA axes may improve responses to conventional HCC therapies. For example, targeting HIF-1α-induced miR-210 could reverse radioresistance in HCC by restoring apoptosis sensitivity [19]. Similarly, combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with lncRNA-targeting approaches might overcome immunosuppression in the hypoxic TME [3] [24]. The lncRNA NEAT1 regulates T cell function through the miR-155/Tim-3 pathway, suggesting that NEAT1 inhibition could enhance checkpoint immunotherapy efficacy [3].

The intricate interplay between HIF-1α and ncRNAs represents a critical regulatory dimension in HCC pathogenesis, with hypoxia serving as a master regulator that coordinates multiple aspects of tumor biology through these networks. The reciprocal regulation between HIF-1α and ncRNAs—with HIF-1α driving ncRNA expression and ncRNAs fine-tuning HIF-1α activity—creates sophisticated feedback loops that amplify oncogenic signaling in the hypoxic TME.

Future research should focus on elucidating the complete landscape of hypoxia-responsive ncRNAs in HCC, particularly circular RNAs which remain relatively unexplored. The development of more sophisticated in vivo models that recapitulate the hypoxic HCC microenvironment will be essential for validating the therapeutic potential of targeting specific HIF-1α-ncRNA axes. Additionally, advancing delivery technologies for ncRNA-based therapeutics will be crucial for clinical translation.

As our understanding of the molecular intricacies between hypoxia and ncRNAs deepens, targeting these networks holds promise for innovative diagnostic strategies and therapeutic interventions in hepatocellular carcinoma, potentially overcoming the limitations of current treatment approaches and improving outcomes for patients with this devastating malignancy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a significant global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most prevalent cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [25]. As the predominant form of primary liver cancer, HCC accounts for approximately 75-90% of all liver cancer cases, with its aggressive progression, unfavorable prognosis, and increasing incidence contributing to its substantial disease burden [26] [27]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) of HCC plays a pivotal role in tumor development, progression, and therapeutic resistance, with recent research highlighting exosomes as crucial mediators of intercellular communication within this niche [26] [25].

Exosomes are nanoscale (30-150 nm) membrane-bound vesicles secreted by nearly all cell types that facilitate intercellular communication by transferring bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [28] [25]. Among these molecules, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as key regulatory elements in HCC pathogenesis. These exosomal ncRNAs include microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), which are selectively packaged and transferred between cells to modulate recipient cell behavior [28]. This review examines the multifaceted roles of exosomal ncRNAs in shaping the immunosuppressive HCC TME, with a focus on their mechanisms of action, experimental methodologies for their study, and their potential clinical applications.

Exosomal ncRNA Biogenesis and Functional Mechanisms

Biogenesis and Delivery

Exosome biogenesis begins with the formation of early endosomes through plasma membrane invagination, which mature into late endosomes or multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [28]. During this process, intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) are generated through inward budding of the endosomal membrane via both ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport)-dependent and ESCRT-independent mechanisms [28]. The ESCRT machinery, composed of four primary complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) along with associated proteins including Hrs, Tsg101, and Alix, facilitates vesicle formation and cargo sorting [28]. ESCRT-independent pathways utilize ceramide-mediated trafficking and tetraspanin-enriched microdomains [28] [29].