Optimizing Lipid Extraction from Plasma and Serum: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Lipidomics

Lipidomic analysis of plasma and serum is crucial for discovering biomarkers and understanding disease mechanisms in biomedical research.

Optimizing Lipid Extraction from Plasma and Serum: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Lipidomics

Abstract

Lipidomic analysis of plasma and serum is crucial for discovering biomarkers and understanding disease mechanisms in biomedical research. However, the diverse chemical nature of lipids and the complexity of blood matrices make efficient and unbiased extraction a significant challenge. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of lipid extraction, a detailed comparison of modern methodological protocols, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and rigorous approaches for method validation. By synthesizing current literature and comparative studies, this content aims to empower scientists to select and optimize lipid extraction methods that ensure high recovery, reproducibility, and biological relevance for their specific research applications.

The Critical Role of Lipid Extraction: Principles and Challenges in Plasma/Serum Analysis

Why Lipid Extraction is a Bottleneck in Plasma/Serum Lipidomics

In lipidomics, the comprehensive analysis of lipid molecules within biological systems, the sample preparation stage is frequently identified as a major critical point. Lipid extraction, in particular, presents significant challenges that can constrain the reliability, reproducibility, and scope of entire studies [1]. This is especially true for complex biofluids like plasma and serum, which contain a diverse array of lipid classes alongside potential interfering compounds such as proteins and salts [2]. The selection of an optimal extraction protocol is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental determinant of data quality, influencing downstream analysis from chromatographic separation to mass spectrometric detection and biological interpretation [3]. This guide addresses the core challenges and provides actionable troubleshooting protocols to overcome the bottleneck of lipid extraction in plasma and serum lipidomics.

FAQ: Fundamental Challenges in Lipid Extraction

1. Why is lipid extraction from plasma/serum particularly challenging?

Plasma and serum present a unique set of challenges due to their complex composition. They contain a wide range of lipid classes with vastly different chemical properties, from polar phospholipids to non-polar cholesteryl esters and triglycerides [2] [3]. This structural diversity means no single solvent system can optimally extract all lipid classes simultaneously. Furthermore, the high abundance of proteins can bind lipids, leading to incomplete recovery, while salts and other water-soluble metabolites can cause ion suppression during mass spectrometric analysis, reducing sensitivity [2] [4]. The ideal extraction method must navigate these challenges to achieve maximum recovery of a broad range of lipids with minimal co-extraction of interfering compounds.

2. What are the key differences between monophasic and biphasic extraction methods, and how do I choose?

The choice between monophasic and biphasic methods is a central consideration in protocol design.

- Biphasic Methods (e.g., Folch, Matyash/MTBE): These methods use a mixture of water-immiscible organic solvents (like chloroform or MTBE) and water/methanol to create two separate phases after centrifugation. Lipids partition into the organic phase, while highly polar contaminants remain in the aqueous phase. This results in cleaner extracts, which is crucial for shotgun lipidomics approaches where samples are directly infused into the mass spectrometer [2]. A key advantage of methods like Matyash (MTBE) is that the lipid-containing organic phase is the top layer, making it easier to collect without contamination [1] [2].

- Monophasic Methods (e.g., IPA, MMC, EE): These methods use a single-phase solvent mixture to precipitate proteins and solubilize lipids. They are typically faster, simpler, and more amenable to automation. However, the resulting extract is "less clean" as it contains salts and other polar metabolites [2]. This is less of an issue for LC-MS-based lipidomics, where chromatographic separation removes these interferences before detection [2].

3. How does the choice of extraction solvent impact my final lipidomic data?

The solvent system directly dictates the efficiency and breadth of lipid recovery. Different solvent combinations have varying affinities for specific lipid classes based on their polarity. Consequently, the selected protocol can significantly skew the observed lipid profile.

- Recovery Bias: Studies show that while methods like Folch and Matyash perform well for many lipid classes, some protocols (e.g., the MTBE method) can yield significantly lower recoveries for specific polar lipids like lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), and sphingomyelins (SM) [2].

- Reproducibility: Some monophasic methods, such as Isopropanol (IPA) and Ethyl Acetate/Ethanol (EE), have been reported to show poor reproducibility for lipids extracted from most tissues, which is a critical consideration for robust statistical analysis [2].

- Chemical Noise vs. Biological Signal: Beyond simply counting the number of detected features, the optimal method should maximize the recovery of biologically relevant lipids while minimizing chemical noise. The ability of a method to capture true biological variability between sample groups is a key metric for enhancing statistical power [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Lipid Extraction Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Lipid Recovery | - Inefficient protein denaturation/lipid release.- Solvent mixture not optimized for target lipid classes.- Incomplete phase separation (for biphasic methods). | - Ensure thorough homogenization/vortexing.- Increase solvent-to-sample ratio.- Consider adding a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA). |

| Poor Reproducibility (High %RSD) | - Inconsistent sample handling or vortexing time.- Human error in collecting the organic phase.- Variable solvent evaporation conditions. | - Strictly standardize all timing and volumes.- Automate steps where possible.- Use internal standards added before extraction. |

| Ion Suppression in MS | - Co-extraction of salts and polar metabolites.- Inefficient chromatographic separation. | - Use biphasic methods for cleaner extracts.- Ensure proper LC column conditioning and mobile phase preparation.- Dilute sample and re-inject if necessary. |

| Incomplete Protein Precipitation | - Insufficiently denaturing solvents.- Solvent-to-sample ratio too low. | - Use proven monophasic cocktails (e.g., MMC) or biphasic systems.- Increase the proportion of organic solvent. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Biphasic MTBE (Matyash) Extraction for Broad Lipid Coverage

This method is widely used for its effectiveness and safety compared to chloroform-based protocols [2] [4].

- Materials: Methanol (MeOH), Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Water (LC-MS grade), Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (SIL-ISTD) mixture.

- Procedure:

- Transfer a measured volume of plasma/serum (e.g., 10-50 µL) to a glass tube.

- Add SIL-ISTDs: Spike with a mixture of internal standards prior to extraction to correct for losses and matrix effects [2].

- Add MeOH: Add 225 µL of MeOH to the sample. Vortex vigorously for 10-30 seconds to denature proteins and initiate lipid solubilization.

- Add MTBE: Add 750 µL of MTBE. Vortex vigorously for 30-60 minutes at room temperature.

- Induce Phase Separation: Add 188 µL of water (LC-MS grade) to induce phase separation. Vortex again briefly and then centrifuge at ~1,000-2,000 RCF for 10-15 minutes.

- Collect Organic Layer: Two phases will form. The upper layer is the lipid-rich MTBE phase. Carefully collect ~80-90% of this upper phase into a new tube.

- Dry and Reconstitute: Evaporate the solvent under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent blend (e.g., Isopropanol/Acetonitrile/Water, 65:30:5 v/v/v) for LC-MS analysis [4].

Protocol 2: Monophasic MMC Extraction for High-Throughput Processing

The MeOH/MTBE/CHCl3 (MMC) method is a monophasic protocol noted for its performance with tissues like liver and intestine, and is suitable for automated workflows [2].

- Materials: Methanol (MeOH), Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Chloroform (CHCl3).

- Procedure:

- Aliquot plasma/serum into a microcentrifuge tube and add internal standards.

- Add Solvent Cocktail: Add a pre-mixed monophasic solvent blend of MeOH/MTBE/CHCl3 in a specified ratio (e.g., 4:3:1 v/v/v) [2].

- Vortex and Centrifuge: Vortex the mixture thoroughly for several minutes to ensure complete protein precipitation and lipid dissolution. Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., >14,000 RCF) for 10 minutes to pellet the precipitated proteins.

- Collect Supernatant: Transfer the clear supernatant, which contains the extracted lipids, to a new vial.

- The extract can be directly analyzed or dried and reconstituted as needed.

Quantitative Comparison of Lipid Extraction Methods

The following table summarizes performance data from a systematic evaluation of six common extraction methods across multiple mouse tissues, which serves as a relevant model for plasma/serum challenges [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common Lipid Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Recovery Concerns | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folch (CHCl3:MeOH 2:1) | Biphasic | High efficacy & reproducibility for many tissues; considered a "gold standard" [2]. | Uses hazardous chloroform; lower organic phase is hard to collect cleanly [2] [4]. | General purpose for pancreas, spleen, brain, plasma [2]. |

| Matyash (MTBE) (MTBE:MeOH) | Biphasic | Less toxic solvents; top-layer organic phase for easy collection [1] [2]. | Significantly lower recovery of LPC, LPE, AcCa, SM, and Sph [2]. | General purpose (with ISTD correction for polar lipids). |

| BUME (BuOH:MeOH) | Biphasic | Designed for automation; top-layer organic phase [2]. | High boiling point of BuOH may risk lipid hydrolysis [2]. | Recommended for liver and intestine [2]. |

| MMC (MeOH/MTBE/CHCl3) | Monophasic | Fast, high-throughput; good performance for liver [2]. | Less clean extract (co-extracts salts) [2]. | High-throughput LC-MS; liver/intestine studies [2]. |

| IPA (Isopropanol) | Monophasic | Rapid, simple protein precipitation [2]. | Poor reproducibility for most tissues [2]. | Use with caution; not recommended for robust studies. |

| mSAP-Spin Column | Solid-Phase | ~10x faster than Matyash; excellent recovery & reproducibility; low LOD [4]. | Requires specialized spin columns and SAP beads [4]. | Fast, sensitive analysis of low-volume plasma samples [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Lipid Extraction

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-ISTDs) | Correct for variable recovery, matrix effects, and instrument variability [2]. | SPLASH Lipidomix (Avanti Polar Lipids). Must be added at the very beginning of extraction [2]. |

| Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Primary solvent in biphasic Matyash method; forms top lipid-containing layer [2]. | HPLC/MS grade. Less toxic alternative to chloroform [2] [4]. |

| Chloroform (CHCl3) | Primary solvent in Folch method; high extraction efficiency for many lipids [2]. | HPLC grade. Highly toxic—use in fume hood with proper PPE [2]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) & Isopropanol (IPA) | Denatures proteins and solubilizes lipids; used in most solvent systems [2]. | LC-MS grade to reduce background noise. |

| Superabsorbent Polymer (SAP) Beads | Solid-phase material for rapid, efficient lipid isolation from small sample volumes [4]. | Used in the mSAP spin-column method [4]. |

| Ammonium Formate / Formic Acid | Mobile phase additives in LC-MS to improve ionization efficiency and chromatographic separation [5] [6]. | Optima LC/MS grade. |

| TLR7-IN-1 | TLR7-IN-1, MF:C17H16N6O2, MW:336.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pan-RAS-IN-5 | Pan-RAS-IN-5, MF:C45H58N8O5S, MW:823.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

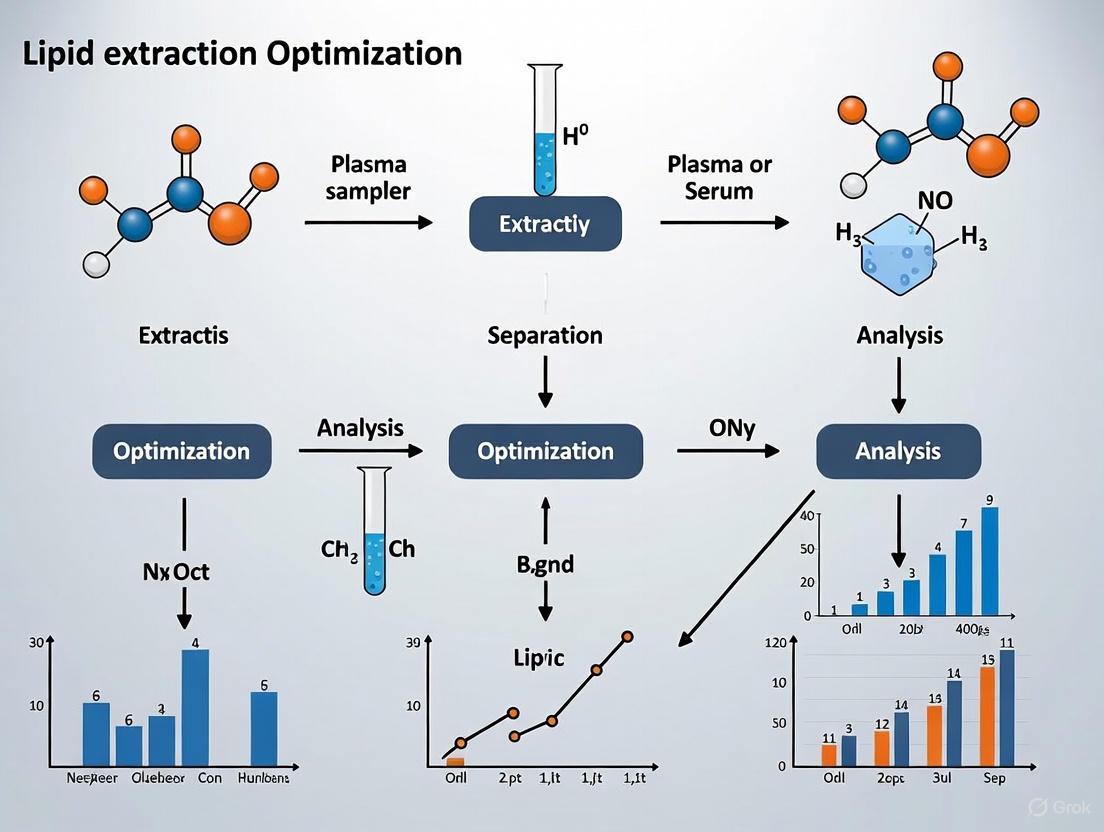

Workflow Visualization: The Lipid Extraction Bottleneck

The following diagram illustrates the lipidomics workflow, highlighting how challenges at the extraction stage create a bottleneck that affects all downstream data.

Overcoming the lipid extraction bottleneck requires a strategic shift from simply maximizing feature count to optimizing for biological relevance and data reliability [1]. This involves:

- Systematic Method Evaluation: Compare a few candidate methods (e.g., Folch, MTBE, MMC) using your specific plasma/serum samples and LC-MS platform. Evaluate them based on reproducibility, recovery of key lipid classes (using ISTDs), and their ability to reveal true biological variance [1].

- Rigorous Quality Control: Incorporate Extraction Quality Controls (EQCs)—pooled samples extracted with each batch—to monitor and correct for technical variability introduced during sample preparation [1].

- Embrace Automation: Where feasible, automate liquid handling steps to significantly improve reproducibility and throughput [2] [4].

- Context-Aware Protocol Selection: Base your choice on the research question. For high-throughput biomarker screening with LC-MS, a monophasic method like MMC may be optimal. For absolute quantification of specific polar lipids, a biphasic method like Folch with carefully chosen ISTDs might be necessary.

By adopting this framework, researchers can transform lipid extraction from a problematic bottleneck into a robust, reliable, and reproducible foundation for impactful lipidomics research.

FAQs: Fundamental Lipid Properties and Analysis

Q1: What are the key lipid classes found in human blood, and what are their primary functions? Blood lipids are broadly categorized into several classes, each with distinct functions. Triacylglycerols (Triglycerides) are the main form of energy storage and transport. They are carried in the core of lipoproteins like chylomicrons and VLDL to be delivered to adipose and muscle tissues [7] [8]. Phospholipids, which are amphipathic molecules with hydrophilic heads and hydrophobic tails, are the primary structural components of all cellular membranes and lipoprotein particles [7] [9]. Sterols, chiefly cholesterol, are another major class; they are essential for modulating membrane fluidity and serve as precursors for steroid hormones and bile acids [7]. Cholesterol is transported in the blood primarily by Low-Density Lipoproteins (LDL) and High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL) [10].

Q2: How does the chemical structure of a lipid influence its physical properties and biological role? The physical properties of lipids are largely dictated by their fatty acid components. Saturation is a key factor.

- Saturated fatty acids have no double bonds, allowing their straight chains to pack tightly. This results in higher melting points, making them solid at room temperature [11] [9].

- Unsaturated fatty acids contain one (monounsaturated) or more (polyunsaturated) double bonds, which are almost always in the cis configuration. This introduces kinks in the hydrocarbon chain, preventing tight packing and leading to lower melting points (e.g., liquid oils) [11] [9]. The degree of unsaturation directly affects membrane fluidity. Furthermore, the position of the double bonds (e.g., omega-3 or omega-6) is critical for their role as signaling molecule precursors [9].

Q3: Why is a biphasic solvent system like chloroform-methanol so effective for lipid extraction? Lipid extraction from biological matrices like plasma is a mass transfer process that must overcome lipid-protein and lipid-membrane associations. A biphasic system, such as the classic Folch method (Chloroform:MeOH, 2:1 v/v), is effective because the mixture serves two key roles [12]:

- The polar solvent (Methanol) disrupts hydrogen bonds and ion-dipole interactions between lipids and proteins, dissolving the more polar lipids and breaking up the matrix [13] [12].

- The non-polar solvent (Chloroform) then efficiently solubilizes the freed neutral lipids and facilitates the formation of a separate organic phase where all lipids partition, allowing for easy separation from water-soluble contaminants [13] [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Lipid Extraction from Plasma/Serum

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Lipid Yield | Inefficient cell membrane/protein disruption; incorrect solvent-to-sample ratio. | Incorporate a pretreatment step (e.g., bead beating, sonication) [12]. Ensure the Folch (2:1) or Bligh & Dyer (1:2:0.8, CHCl₃:MeOH:H₂O) ratios are meticulously followed [12]. |

| Poor Sample Cleanup (contamination with non-lipids) | Incomplete phase separation; inadequate washing of the organic phase. | Add a saline solution (e.g., 0.9% NaCl or KCl) to improve phase separation [7] [12]. Wash the collected organic (lower) phase with a theoretical upper phase (CHCl₃:MeOH:H₂O, 3:48:47) to remove water-soluble impurities [12]. |

| Oxidation of Unsaturated Lipids | Exposure to oxygen during extraction and storage. | Add an antioxidant, such as Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT), to the solvent mixtures [13]. Perform procedures under an inert nitrogen atmosphere and store lipid extracts at -80°C [14]. |

| Inconsistent LC-MS Results | Pre-analytical variables; solvent effects. | Standardize blood collection, processing time, and storage conditions (fast-freeze in liquid Nâ‚‚) [14]. Use mass spectrometry-grade solvents and ensure complete dryness and consistent reconstitution for LC-MS [14] [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Chloroform-Free Total Lipid Extraction from Human Plasma

This protocol is adapted from modern sustainable lipidomics research [13] and provides an alternative to traditional chloroform-based methods.

Principle: This single-phase extraction uses Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) as a greener alternative to chloroform, mixed with methanol and MTBE to efficiently extract a broad range of lipids from plasma by disrupting hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions.

Materials & Reagents:

- Reconstituted human plasma sample

- Ice-cold Methanol (MeOH)

- Ice-cold Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)

- Cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME)

- Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, 0.01% w/v in solvent mixtures)

- Isopropanol (i-PrOH)

- Water (Hâ‚‚O, ULC-MS grade)

- Centrifuge and microcentrifuge tubes

- Vortex mixer and rotary shaker

- Nitrogen evaporator

Procedure:

- Preparation: Spike all solvent mixtures with 0.01% BHT to prevent lipid oxidation.

- Protein Precipitation & Extraction: To 5 µL of human plasma in a microcentrifuge tube, add 180 µL of ice-cold MeOH. Vortex for 30 seconds.

- Solvent Addition: Add 600 µL of ice-cold MTBE and 300 µL of CPME. Vortex vigorously for 30 seconds.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture on a rotary shaker for 60 minutes at 40 rpm and 4°C.

- Phase Separation: Add 150 µL of ice-cold H₂O to induce phase separation. Vortex for 30 seconds and shake for 10 minutes at 40 rpm and 4°C.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge for 10 minutes at 1,000 × g and 4°C to achieve clear phase separation.

- Collection: Carefully collect the upper organic phase (approximately 540 µL) into a new tube.

- Concentration: Evaporate the organic solvent to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in 50 µL of i-PrOH, shake for 15 minutes, and centrifuge briefly. The sample is now ready for downstream analysis (e.g., LC-MS).

Lipid Transport and Metabolism Pathways

Lipid Transport Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Lipid Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) | Classic non-polar solvent for biphasic extraction; dissolves neutral lipids [12]. | High toxicity and environmental hazard. Use in fume hood with proper PPE [13]. |

| Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) | Greener alternative to chloroform; used in single-phase extraction [13]. | Lower health risk, good sustainability profile, and comparable extraction efficiency for many lipid classes [13]. |

| Methanol (MeOH) | Polar solvent that disrupts lipid-protein complexes and dissolves polar lipids [12]. | Essential component of most extraction mixtures. Miscible with water. |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Antioxidant added to solvent mixtures [13]. | Prevents oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) during extraction and storage. |

| MTBE (Methyl tert-butyl ether) | Solvent used in single-phase and biphasic extraction protocols [13]. | Often combined with methanol. Forms the upper organic phase in the MTBE method [13]. |

| Ammonium Formate / Formic Acid | Mobile phase additives for LC-MS [13]. | Promotes protonation and improves ionization efficiency of lipids in mass spectrometry. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Lipid Extraction Issues in Plasma/Serum Research

Problem 1: Low Lipid Recovery from Plasma Samples

- Possible Cause: Inefficient disruption of lipoprotein complexes or incorrect solvent-to-sample ratio.

- Solution: Ensure adequate sample pre-treatment. For delipidation of plasma while preserving proteins, use a mixture of butanol and di-isopropyl ether (40/60, v/v). One volume of plasma is added to two volumes of this solvent mixture and rotated for 30 minutes [15].

- Prevention: Standardize the sample volume and always use the correct solvent proportions. For the classical Folch method, use a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of chloroform to methanol [16].

Problem 2: Persistent Lipemic Interference in Biochemical Assays

- Possible Cause: Incomplete removal of lipoproteins (chylomicrons) leads to turbidity, which affects spectrophotometric measurements [17].

- Solution: Employ high-speed centrifugation. Centrifuging serum/plasma samples at 10,000×g for 15 minutes effectively removes the lipid layer, and the infranatant (aqueous phase) can be collected for analysis [17].

- Prevention: For clinical samples, ensure patient fasting when required. Avoid using chemical agents like LipoClear or 1,1,2-trichlorotrifluoroethane for lipemia removal, as they can interfere with the measurement of certain parameters like total protein, albumin, and calcium [17].

Problem 3: Solvent Toxicity and Environmental Concerns

- Possible Cause: Use of hazardous solvents like chloroform.

- Solution: Investigate safer solvent alternatives. Some studies show that toluene can be a valid substitute for chloroform in specific extraction protocols for microbial lipids [18]. Ethanol is another potential, though sometimes less effective, substitute for methanol [18].

- Prevention: Transition to green solvent-based methods where possible, such as supercritical CO2 extraction (SCE), which is non-toxic and leaves no residue [16] [19].

Problem 4: Emulsification During Liquid-Liquid Extraction

- Possible Cause: Over-vigorous mixing or the nature of the biological sample can create stable emulsions, trapping lipids and preventing phase separation [20].

- Solution: Use controlled, gentle agitation during extraction. If an emulsion forms, low-speed centrifugation can often break it. Bead beating can also be optimized to disrupt cells without excessive emulsion formation [18].

- Prevention: Ensure the correct pH and ionic strength. Adding salts like NaCl or KCl, as in the Folch wash step, can facilitate cleaner phase separation [16].

Problem 5: Inconsistent Results Between Different Sample Types

- Possible Cause: The efficiency of a single extraction protocol can vary significantly based on the cell wall structure and lipid composition of the source material [16] [18].

- Solution: Optimize the extraction method for each specific biological matrix (e.g., plasma, yeast, microalgae). This may require testing different solvent polarities and cell disruption methods [21] [18].

- Prevention: Do not assume a universal method. For high-value applications, use a hybrid AI-powered simulation approach that combines mechanistic modeling and machine learning to predict the optimal extraction process for a specific sample and desired outcome [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind selecting solvents for lipid extraction? The core principle is selectivity based on solubility, governed by the partition coefficient (K). A solvent mixture, typically comprising a polar (e.g., methanol) and a non-polar (e.g., chloroform) solvent, is used because of the chemical diversity of lipids. The polar solvent disrupts protein-lipid complexes and dissolves polar lipids, while the non-polar solvent dissolves neutral lipids [16] [22]. A higher partition coefficient for a lipid in the organic solvent phase leads to more efficient extraction.

Q2: Why are chloroform and methanol so commonly used together? This combination is effective because it covers a broad range of lipid polarities. Chloroform (non-polar) efficiently solubilizes neutral lipids like triacylglycerols, while methanol (polar) disrupts hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions between polar lipids (like phospholipids) and membranes or proteins. The classic Folch method uses a 2:1 chloroform-methanol ratio, and the Bligh and Dyer method is a modification of this for smaller sample sizes [16].

Q3: How does solvent polarity directly affect the yield and profile of extracted lipids? Solvent polarity directly determines which lipid species are solubilized. Non-polar solvents like hexane and chloroform yield higher total amounts of neutral lipids, which are rich in saturated fatty acids. In contrast, polar solvents like methanol are more effective at extracting polar lipids, which often contain more unsaturated fatty acids [21]. Therefore, the choice of solvent dictates the resulting fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) composition and subsequent biodiesel properties if used for biofuel [21].

Q4: What are the key considerations for delipidating plasma without denaturing proteins? The primary goal is to extract lipids while keeping proteins in a soluble, native state in the aqueous phase. A specific solvent system like butanol/di-isopropyl ether (40/60, v/v) is recommended for this purpose. Butanol helps to dissociate lipids from proteins without causing irreversible denaturation, allowing the delipidated proteins to be recovered from the aqueous phase [15].

Q5: Are there effective and safer alternatives to chlorinated solvents? Yes, research into greener alternatives is ongoing. Supercritical CO2 is a prominent non-toxic, non-flammable alternative, especially for neutral lipids [16] [19]. Other options include solvent substitution, such as using toluene instead of chloroform or ethanol instead of methanol, though their efficacy can be species-dependent and requires validation for each application [18].

Quantitative Data: Solvent Polarity and Extraction Performance

The following table summarizes quantitative findings on how solvent polarity influences lipid extraction efficiency and profile, based on experimental data.

Table 1: Impact of Solvent Polarity on Microalgal Lipid Yield and Biodiesel Properties [21]

| Solvent Type | Example Solvents | Total Lipid Yield (mg/g microalgae) | Total Saturated Fatty Acids (SFAs) | Total Unsaturated Fatty Acids (UFAs) | Key Biodiesel Property (Cetane Number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Polar | Chloroform, Hexane | 94.33 - 100.01 | 61.53% (Chloroform) | 38.47% (Chloroform) | Higher |

| Polar | Methanol, Acetone | 40.12 - 86.91 | 38.85% (Methanol) | 61.15% (Methanol) | Lower |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Lipid Extraction Methods for Biological Samples

| Extraction Method | Solvent System | Typical Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folch Method [16] | Chloroform/Methanol (2:1, v/v) | General lipidomics; animal tissues | High extraction efficiency; considered a gold standard | Uses toxic chloroform; requires a purification wash step |

| Bligh & Dyer Method [16] | Chloroform/Methanol/Water (1:2:0.8, v/v) | High-throughput screening; animal tissues with high water content | Rapid; adapted for smaller sample sizes | Less effective for samples with very high water content |

| Butanol/Diisopropyl Ether [15] | Butanol/Diisopropyl Ether (40:60, v/v) | Plasma/Serum delipidation | Preserves protein integrity; effective for clinical samples | May not extract all lipid classes with equal efficiency |

| High-Speed Centrifugation [17] | N/A (Physical separation) | Removing lipemia from serum/plasma for clinical assays | No chemical interference; simple and practicable | Only removes lipoproteins, does not extract lipids for analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Protocol 1: Folch Method for Total Lipid Extraction from Tissues [16]

- Homogenize the tissue sample in a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of chloroform-methanol (e.g., 20 mL solvent per 1 g of tissue).

- Filter the homogenate to remove solid debris.

- Add a salt solution (e.g., 0.05 N NaCl or KCl) at a ratio of 0.2 volumes of salt solution to 1 volume of the chloroform-methanol filtrate. This promotes phase separation.

- Mix thoroughly and let the phases separate. The lower organic phase (chloroform) contains the extracted lipids.

- Recover the lower chloroform phase carefully, avoiding the interface.

- Evaporate the chloroform under a stream of nitrogen or using a rotary evaporator to obtain the purified lipid extract.

Protocol 2: Delipidation of Plasma/Serum with Protein Preservation [15]

- To one volume of serum or plasma (containing 0.1 mg/ml EDTA as an anticoagulant/antioxidant), add two volumes of a butanol/di-isopropyl ether (40/60, v/v) mixture.

- Tightly close the vials and fasten them on a mechanical rotator. Provide end-over-end rotation at 30 rpm for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuge the mixture at low speed (approx. 2,000×g) for 2 minutes to achieve clear phase separation.

- The aqueous phase (lower phase) contains the delipidated proteins. Remove it carefully using a needle and syringe or pipette.

- To remove traces of butanol, the aqueous phase can be washed with two volumes of pure di-isopropyl ether.

- Residual solvent in the aqueous protein solution can be removed by aspiration under vacuum at 37°C for a few minutes.

Protocol 3: Removing Lipemia via High-Speed Centrifugation [17]

- Homogenize the lipemic serum or plasma sample using a vortex mixer.

- Pipette 1 mL of the sample into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge at 10,000×g for 15 minutes.

- After centrifugation, the lipid layer will form a compact upper phase. Carefully collect the clarified infranatant (the aqueous phase at the bottom of the tube) using a fine-needle syringe, taking care not to aspirate the lipid layer.

- The infranatant is now suitable for downstream biochemical analysis.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Decision Workflow for Lipid Handling in Plasma/Serum Research

How Solvent Polarity Targets Different Lipid Classes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Lipid Extraction from Plasma/Serum

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform | Non-polar solvent for dissolving neutral lipids [16] | Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods for total lipid extraction. |

| Methanol | Polar solvent for disrupting lipid-protein complexes and dissolving polar lipids [16] | Used in combination with chloroform in classical methods. |

| Butanol/Diisopropyl Ether Mix | Solvent system for delipidation with protein preservation [15] | Extracting lipids from plasma or serum without denaturing apolipoproteins. |

| Ethylenediamine Tetraacetate (EDTA) | Chelating agent that binds metal ions to prevent oxidation [15] | Added to plasma/serum samples before delipidation to preserve sample integrity. |

| Glass Beads (425-600 μm) | Mechanical means for cell disruption to enhance solvent access [18] | Bead beating for efficient lipid extraction from yeast or other tough cell walls. |

| High-Speed Centrifuge | Physical separation of lipid layers from aqueous samples [17] | Removing lipemia from clinical serum/plasma samples prior to analysis. |

| ML349 | ML349, MF:C23H22N2O4S2, MW:454.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| WR99210 | WR99210, CAS:30711-93-4; 30737-44-1; 47326-86-3, MF:C14H18Cl3N5O2, MW:394.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Lipid Extraction from Plasma Serum Samples

FAQ 1: How can I prevent the co-extraction of non-lipid contaminants that interfere with my LC-MS analysis?

Issue: Non-lipid contaminants, such as proteins and sugars, are co-extracted, leading to ion suppression in MS, column fouling in HPLC, and reduced analytical sensitivity [23] [12].

Solution & Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement a Robust Wash Step: The classical Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods include a wash step with a salt solution (e.g., KCl, NaCl, or water) to partition non-lipid polar contaminants into the aqueous-methanol phase while lipids remain in the organic phase [12]. Ensure the extraction mixture reaches the correct final solvent-to-sample ratio for proper phase separation.

- Adopt the BUME Method: This automated, chloroform-free method is designed to minimize contamination. It uses a two-phase system with 1% acetic acid, which helps purify the lipid extract. The lipids are recovered from the upper heptane-ethyl acetate phase, reducing the risk of aspirating the protein-rich interphase [23].

- Verify Phase Separation: After adding the wash buffer, allow the mixture to separate completely. Carefully aspirate the upper aqueous phase without disturbing the interphase or the lower organic phase. If the interphase is thick and protein-rich, it may be better to sacrifice a small amount of the organic phase to avoid contamination [23].

FAQ 2: What is the most effective way to ensure complete cell wall disruption for maximal lipid yield from complex samples?

Issue: Incomplete disruption of cells, such as those with tough walls in microbial samples, results in low and inconsistent lipid yields because solvents cannot access intracellular lipids [12] [24].

Solution & Troubleshooting Steps:

- Choose a Physical Disruption Method: For samples with robust cell walls (e.g., plants, fungi, microalgae), mechanical methods are highly effective.

- Bead Milling: Agitate the sample at high speed with beads. Use 0.5 mm glass beads for yeast and 3–7 mm stainless steel or tungsten carbide beads for plant and fungal tissues [25].

- Rotor-Stator Homogenization: Effective for animal and plant tissues, using mechanical shearing for disruption in seconds [25].

- High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH): Forces a cell suspension through a narrow valve at high pressure (e.g., 10-300 MPa). Pressures above 100 MPa are often needed for robust microalgal cells [24].

- Sonication: Uses high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles, whose collapse generates shear forces that break open cells [24].

- Optimize Pretreatment for Your Sample: The optimal method depends on the sample's cell wall composition. A combination of treatments may be necessary for maximum yield [12].

- For Plasma/Serum: Note that mechanical disruption is typically not required for plasma or serum samples, as lipids are already compartmentalized within lipoproteins. The primary step here is the efficient disruption of these lipoprotein complexes using a solvent like methanol in the initial one-phase extraction [23].

FAQ 3: My lipid recoveries are low and variable. How can I improve the efficiency and reproducibility of my extraction?

Issue: Low recovery can stem from inefficient solvent systems, incomplete sample mixing, or failure to optimize the protocol for your specific sample matrix.

Solution & Troubleshooting Steps:

- Select the Appropriate Solvent System: The solvent must be capable of both disrupting lipid-protein complexes and dissolving a wide range of lipids. A mixture of polar and non-polar solvents is essential [12].

- Ensure Complete Homogenization: During the initial one-phase extraction, ensure the sample and solvents are mixed thoroughly to form a fine suspension. This is critical for efficient and reproducible lipid solubilization [23].

- Automate the Process: Manual liquid handling can be a significant source of variability. Implementing an automated extraction protocol on a liquid handling robot, as demonstrated with the BUME method, can greatly improve reproducibility and throughput [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Lipid Extraction Method Performance

| Method | Key Solvents | Extraction Efficiency (vs. Reference) | Key Advantages | Reported Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUME [23] | Butanol:MeOH, Heptane:Ethyl Acetate | Similar or better for major lipid classes [23] | Chloroform-free, automated, upper-phase lipid recovery, 96 samples/60 min [23] | Requires optimization for robot parameters [23] |

| Folch [12] | CHCl₃:MeOH (2:1) | Reference Method [12] | High efficiency for wide hydrophobicity range [12] | Chloroform use, lower phase recovery, manual, tedious [23] [12] |

| Bligh & Dyer [12] | CHCl₃:MeOH (1:2) | Reference Method [12] | Adapted for high water content samples [12] | Chloroform use, prone to contamination, manual [23] [12] |

| MTBE [23] | MTBE:MeOH | Similar lipid profiles [23] | Upper-phase lipid recovery [23] | High solvent-to-sample ratio, challenging automation [23] |

Table 2: Performance of Cell Disruption Methods for Intracellular Lipid Extraction

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Typical Application Scale | Reported Effectiveness | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Homogenization [24] | High shear force, turbulence, and cavitation from pressure drop [24] | Industrial / Large-scale [24] | Effective for tough-walled microalgae (e.g., Nannochloropsis); protein release from yeast: 50 µg/g [24] | High energy consumption; cell age and wall composition affect required pressure [24] |

| Ultrasonication [24] | Cavitation from high-frequency sound waves [24] | Lab / Small to medium-scale [24] | Effective for a wide range of cell types; suitable for heat-sensitive compounds [24] | Potential for local heating; scale-up can be challenging [24] |

| Bead Milling [25] | Shearing and crushing from high-speed agitation with beads [25] | Lab / Small-scale [25] | Thorough disruption for bacteria, yeast, and plant tissues [25] | Optimization of bead size and material is critical; can generate heat [25] |

| Rotor-Stator Homogenization [25] | Mechanical shearing from a high-speed rotor [25] | Lab / Small-scale [25] | Rapid disruption (5-90 sec) of animal and plant tissues [25] | Not ideal for very small sample volumes; foaming can occur [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The Automated BUME Extraction Method for Plasma/Serum

This protocol is adapted from Löfgren et al. for a fully automated, high-throughput, and chloroform-free lipid extraction from plasma or serum samples [23].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- BUME Mixture (Solvent 1): Butanol:Methanol (3:1, v/v)

- Solvent 2: Heptane:Ethyl Acetate (3:1, v/v)

- Acetic Acid Solution: 1% (v/v) acetic acid in water

- Plasma/Serum Samples

- Automated Liquid Handling Robot (e.g., Velocity 11 Bravo) equipped with a 96-well head

- 96-well glass vial racks and 1.2 ml glass vials

2. Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Pipette 10–100 µl of plasma/serum into individual glass vials in a 96-well rack [23].

- Initial One-Phase Extraction: Add 300 µl of the BUME Mixture (Solvent 1) to each sample. The robot mixes the contents to form a fine suspension, ensuring efficient dissolution of lipoproteins and solubilization of lipids. This step is critical for complete initial extraction [23].

- Secondary Two-Phase Extraction: Add 300 µl of Solvent 2 (Heptane:Ethyl Acetate) to the mixture, followed by 300 µl of 1% Acetic Acid buffer. The robot mixes the contents. A two-phase system will form spontaneously without centrifugation. The lipids partition into the upper organic phase (heptane/ethyl acetate), while non-lipid contaminants partition into the lower aqueous phase [23].

- Recovery of Lipid Extract: The robot automatically aspirates the upper organic phase containing the purified lipids, ready for downstream analysis like LC-MS [23].

3. Critical Notes:

- The method has demonstrated linear lipid recoveries across a plasma volume of 10–100 µl [23].

- Robot parameters (aspiration/dispensing speed and position) must be optimized for robustness [23].

Protocol 2: High-Pressure Homogenization for Cell Disruption

This protocol describes the use of HPH for disrupting microbial cells to facilitate subsequent lipid solvent extraction [24].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Microbial cell biomass (e.g., microalgal paste)

- Suitable aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer)

- High-Pressure Homogenizer (e.g., from Avestin, GEA Niro Soavi)

- Cooling system

2. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a concentrated suspension of microbial cells in an appropriate buffer.

- Homogenization: Feed the cell suspension into the homogenizer. The pressure and number of passes must be optimized for the specific cell type.

- For the microalgae Porphyridium cruentum, a pressure above 100 MPa was critical for effective disruption and release of the pigment B-Phycoerythrin [24].

- For the microalgae Parachlorella kessleri, increasing passes at 120 MPa released protein concentrations up to 3656 mg/L [24].

- For Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, homogenization at 80 MPa was effective for protein extraction [24].

- Collection: Collect the homogenate, which contains the disrupted cells and released intracellular components, including lipids. This homogenate is now ready for lipid extraction using a solvent-based method like BUME or Folch.

3. Critical Notes:

- The process can generate heat, so using a cooling jacket is advisable to protect heat-sensitive compounds.

- Cell wall composition and cell age significantly impact the required disruption pressure [24].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Troubleshooting Workflow for Common Pitfalls

BUME Method Lipid Extraction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Optimized Lipid Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function in Lipid Extraction | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Butanol:MeOH (BUME) Mixture [23] | Initial one-phase extraction solvent; disrupts protein-lipid complexes and solubilizes a wide range of lipids. | Primary solvent in the automated BUME method for plasma/serum [23]. |

| Heptane:Ethyl Acetate [23] | Secondary two-phase extraction solvent; forms the upper organic phase for easy lipid recovery and reduced contamination. | Used in the BUME method after the initial one-phase extraction [23]. |

| Chloroform:MeOH [12] | Classical solvent mixture for efficient total lipid extraction via Folch or Bligh & Dyer methods. | Reference method for lipid extraction efficiency [12]. |

| 1% Acetic Acid [23] | Aqueous buffer in two-phase systems; facilitates phase separation and purifies lipid extract by partitioning non-lipids into the aqueous phase. | Wash buffer in the BUME method [23]. |

| High-Pressure Homogenizer [24] | Physical disruption equipment for breaking tough cell walls to release intracellular lipids prior to solvent extraction. | Disrupting microalgae (e.g., Nannochloropsis) and yeast cells [24]. |

| Bead Mill [25] | Physical disruption equipment using beads for shearing and crushing cells. | Disruption of bacterial, yeast, and plant tissues in a laboratory setting [25]. |

| J30-8 | J30-8, MF:C17H9ClFN3O2S, MW:373.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PF-06424439 | PF-06424439, MF:C22H26ClN7O, MW:439.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accurate analysis of lipids from biological samples is a critical step in lipidomics and biomedical research. The methods established by Folch et al. and Bligh & Dyer remain the gold standards for lipid extraction over six decades after their development. These biphasic solvent systems, utilizing chloroform, methanol, and water, are designed to efficiently isolate a broad range of lipid classes while removing non-lipid contaminants. Within the context of optimizing lipid extraction from plasma and serum samples, understanding the specific parameters, advantages, and limitations of these foundational protocols is essential for obtaining reliable and reproducible data in drug development and clinical research.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The Folch Method

The Folch method was originally developed for the extraction of lipids from brain tissue and uses a chloroform:methanol:water system in a ratio of 8:4:3 (v/v/v) [26] [12].

Detailed Protocol:

- Homogenization: Homogenize the plasma or tissue sample in a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of chloroform-methanol. The classical sample-to-solvent ratio is 1:20 [26] [27]. For instance, for 1 mL of plasma, add 20 mL of the chloroform-methanol (2:1) mixture.

- Partitioning: Add a volume of water or a salt solution (e.g., 0.9% NaCl or 0.003 N CaClâ‚‚) equal to one-quarter the volume of the chloroform-methanol mixture used. This shifts the solvent system to the biphasic state.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture to separate the phases. The lower, dense chloroform-rich phase contains the extracted lipids. The upper phase is methanol-water rich and contains non-lipid contaminants. An interface of denatured proteins is often present.

- Recovery: Carefully aspirate and discard the upper phase. The lower organic phase can be recovered by siphoning or pipetting through the protein disk.

- Washing (Optional): To further purify the lipid extract, "wash" the lower phase by adding a fresh volume of theoretical upper phase (chloroform:methanol:water, 3:48:47) and repeating the centrifugation and separation [28].

The Bligh & Dyer Method

The Bligh & Dyer method was developed as a rapid, microscale extraction for fish muscle, using a chloroform:methanol:water system in a ratio of 2:2:1.8 (v/v/v) [26] [12]. It uses less solvent than the Folch method.

Detailed Protocol for Liquid Samples (e.g., Plasma):

- Initial Monophasic System: To 1 mL of plasma, add 3.75 mL of a chloroform/methanol mixture in a 1:2 ratio [29]. Vortex vigorously for 10-15 minutes.

- Inducing Biphasic System: Add 1.25 mL of chloroform and mix for 1 minute.

- Final Separation: Add 1.25 mL of water and mix for another minute.

- Centrifugation and Recovery: Centrifuge to separate the phases. The lower, dense chloroform-rich phase contains the lipids and is recovered as described in the Folch method [29].

Comparative Analysis and Optimization for Plasma/Serum

Quantitative Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods, particularly in the context of plasma-based lipidomics.

Table 1: Comparison of Folch and Bligh & Dyer Lipid Extraction Methods

| Feature | Folch Method | Bligh & Dyer Method |

|---|---|---|

| Original Solvent Ratio (CHCl₃:MeOH:H₂O) | 8:4:3 (v/v/v) [26] | 2:2:1.8 (v/v/v) [26] |

| Classical Sample-to-Solvent Ratio | 1:20 [26] [27] | 1:3 (does not account for tissue water) [26] |

| Organic Layer Position | Bottom (higher density) [26] | Bottom (higher density) [26] |

| Recommended Plasma Sample Ratio | 1:20 (v/v) [26] [27] | 1:20 (v/v) [26] [27] |

| Extraction Efficiency for High-Lipid Samples | Accurate for a broad range [30] | Underestimates lipid content in samples >2% lipid [29] [30] |

| Multi-Omic Capability (Plasma) | Suitable for lipidomics and metabolomics from organic and aqueous phases [26] [27] | Suitable for lipidomics and metabolomics from organic and aqueous phases [26] [27] |

Optimization for Plasma and Serum Research

Optimizing the sample-to-solvent ratio is vital for comprehensive lipid coverage in untargeted lipidomics.

- Sample-to-Solvent Ratio: A systematic evaluation for human plasma demonstrated that a 1:20 (v/v) plasma-to-total-solvent ratio yielded the highest peak areas for a diverse range of lipid and metabolite species for both Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods. Decreasing the ratio (e.g., to 1:4) or increasing it (e.g., to 1:100) resulted in lower recoveries [26] [27].

- Handling and Storage: To prevent artefact formation and lipid degradation, samples should be frozen immediately at -20°C or lower in an atmosphere of nitrogen. Tissues should be homogenized and extracted with solvent at the lowest temperature practicable without being allowed to thaw [28].

- Modifications for Specific Lipids: The recovery of acidic phospholipids can be improved by replacing water with 1M NaCl or adding 0.5% acetic acid (v/v) to the water phase during partitioning [29].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does the Bligh & Dyer method underestimate lipid content in fatty samples? The Bligh & Dyer method was designed for tissues with low lipid content. In samples with more than 2% lipid, the solvent volumes become insufficient for complete extraction, leading to a significant underestimation of total lipid content that worsens with increasing lipid levels [29] [30]. For fatty tissues, the Folch method with its higher solvent ratio is more reliable [30].

Q2: My lipid extract contains a large amount of free fatty acids and lysophospholipids. What went wrong? This is a classic sign of lipolytic degradation. It indicates that lipids were exposed to active lipases, likely due to improper sample handling. This can occur if tissues were not frozen rapidly after collection, were subjected to slow thawing, or if extraction was not performed promptly on frozen tissue [28]. Ensure rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen and homogenize while the sample is still frozen.

Q3: What is a key practical difference when handling the organic phase between these methods and the newer Matyash (MTBE) method? In both Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods, the chloroform-rich organic phase is denser than water and forms the lower layer [26]. This is the opposite of the Matyash method, which uses methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), where the organic phase is less dense and forms the upper layer, making it easier to collect [26] [31].

Q4: Can I use these extraction methods for a multi-omics approach? Yes. A significant advantage of these biphasic extractions is the ability to analyze both the organic phase (for lipidomics) and the aqueous phase (for metabolomics) from a single sample preparation. This increases analyte coverage and provides a more comprehensive understanding of the biological system [26] [27].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Lipid Extraction

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Lipid Yield | Incorrect solvent ratios; insufficient sample disruption; sample-too-solvent ratio too high. | Precisely measure solvents; optimize homogenization; use a 1:20 (v/v) sample-to-solvent ratio for plasma [26]. |

| Lipid Degradation (High FFAs) | Poor sample storage/handling; lipase activity. | Freeze samples immediately in liquid nitrogen; store at -80°C; add antioxidants to solvents; homogenize frozen tissue [28]. |

| Contamination with Non-Lipid Material | Incomplete phase separation; aqueous phase carried over. | Ensure final solvent ratios are correct for biphasic system; be careful when collecting the organic layer [12] [28]. |

| Poor Recovery of Acidic Phospholipids | Ionic interactions with denatured proteins at the interface. | Acidify the water phase with dilute HCl or use 1M NaCl for partitioning [29]. |

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points and steps for selecting and performing these lipid extraction methods.

Lipid Extraction Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Lipid Extraction

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Chloroform | Primary non-polar solvent; dissolves neutral lipids and forms the dense organic phase [12]. |

| Methanol | Polar solvent; disrupts lipid-protein complexes and hydrogen bonding; deactivates lipolytic enzymes [26] [12]. |

| Water (HPLC/MS Grade) | Used to induce biphasic phase separation and partition non-lipid contaminants into the upper aqueous phase [26]. |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., 1M NaCl, KCl) | Added during partitioning to improve recovery of specific lipid classes (e.g., acidic phospholipids) by altering ionic strength [29] [31]. |

| Glass Tubes with Teflon-lined Caps | Prevents solvent evaporation and leaching of contaminants from plastic [28]. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., BHT) | Added to solvents to prevent autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids during extraction and storage [28]. |

| Inert Atmosphere (Nâ‚‚ Gas) | Used to store tissue samples and final lipid extracts to prevent oxidation [28]. |

| KU004 | KU004, MF:C29H27ClFN4O2P, MW:549.0 g/mol |

| P2X7-IN-2 | P2X7-IN-2, MF:C22H21F4N3O2, MW:435.4 g/mol |

A Practical Guide to Lipid Extraction Protocols for Blood Samples

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Poor Lipid Recovery or Low Extraction Yield

Problem: Inconsistent or lower-than-expected recovery of lipids from plasma samples.

Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incomplete Phase Separation

- Solution: Ensure precise solvent ratios. For the Matyash method, use MTBE/methanol/water in a ratio of 10/3/2.5 (v/v/v). For Folch, use chloroform/methanol 2:1 (v/v) with 0.2 volumes of water or saline. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 minutes at a consistent temperature (20°C) to achieve complete separation [32] [33].

- Prevention: Allow the mixture to settle in a stable, vibration-free environment before and after centrifugation.

Cause 2: Improfficient Cell Disruption

- Solution: For complex samples, implement mechanical pretreatments such as bead beating or high-pressure homogenization to disrupt cell walls and facilitate solvent penetration. Osmotic shock has been shown to increase lipid yield by 2.8-fold in some microorganisms [16].

- Prevention: For tough tissues, consider a combination of pretreatments (e.g., enzymatic disruption followed by mechanical homogenization) [16].

Cause 3: Solvent Evaporation or Handling Errors

- Solution: Always use glass syringes or positive displacement pipettes to accurately transfer the organic phase. When using the Folch method, carefully collect the lower chloroform phase. For Matyash, take the upper MTBE phase [32] [28].

- Prevention: Perform extractions in a temperature-controlled environment to minimize solvent evaporation.

Guide 2: Formation of Persistent Emulsions

Problem: A stable emulsion forms at the interface, preventing clean phase separation.

Solutions:

- Cause 1: Over-Homogenization or Vigorous Mixing

- Solution: If an emulsion forms, increase centrifugation time to 15-20 minutes or briefly recentrifuge. Alternatively, add a small volume of saturated NaCl solution (5-10% of total volume) to break the emulsion [28].

- Prevention: Use gentle inversion mixing instead of vortexing, especially for protein-rich samples like plasma.

- Cause 2: Sample-Specific Interferences

- Solution: For plasma samples with high lipoprotein or protein content, consider a slight modification of the solvent-to-sample ratio. A "modified Matyash" system (MTBE/methanol/water, 2.6/2.0/2.4, v/v/v) has shown improved performance in complex samples [33].

- Prevention: Dilute viscous plasma samples with a minimal amount of saline before extraction.

Guide 3: Lipid Degradation or Artefact Formation

Problem: Detection of elevated levels of free fatty acids, lysophospholipids, or other lipid degradation products.

Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Inactivation of Lipolytic Enzymes

- Solution: Ensure plasma is processed and frozen rapidly after collection. Homogenize samples in the presence of extraction solvents at the lowest practical temperature to denature enzymes [28].

- Prevention: Add lipase inhibitors during plasma collection if profiling sensitive lipid classes. Store plasma at -80°C and limit freeze-thaw cycles [32] [28].

- Cause 2: Sample Oxidation

- Solution: Include antioxidants like butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) (50-100 μM) in your extraction solvents, especially for polyunsaturated fatty acid analysis [28] [34].

- Prevention: Perform extractions under an inert nitrogen atmosphere, and store lipid extracts in apolar solvents like chloroform or hexane at -80°C under nitrogen [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which method, Folch or Matyash, provides superior lipid recovery for LC-MS-based lipidomics of plasma?

While both methods are effective for global lipidomics, comparative studies show nuanced differences. The single-phase methanol/1-butanol method demonstrated comparable effectiveness to Folch and Matyash for most lipid classes and was more effective in extracting polar lipids [32]. A "modified Matyash" method (MTBE/methanol/water, 2.6/2.0/2.4) showed a 4-20% higher number of detectable peaks and putatively annotated metabolites compared to the Bligh and Dyer (a Folch-derived method) and original Matyash methods in serum and other samples [33]. The choice depends on your target lipidome; for polar lipids, the single-phase method may be better, while the modified Matyash offers broad coverage.

Q2: Is it necessary to deactivate enzymes in plasma samples prior to lipid extraction?

Yes, this is a critical step. Lipolytic enzymes remain active even at low temperatures and can rapidly alter the lipid profile. Appreciable hydrolysis of phospholipids has been observed in tissues and plasma stored at -20°C and even during extraction if enzymes are not denatured [28]. The best practice is to freeze plasma rapidly at -80°C immediately after collection and to homogenize or mix the thawed plasma directly with the organic solvents, which themselves deactivate many enzymes [28].

Q3: What is the key practical advantage of the MTBE-based (Matyash) method over the chloroform-based (Folch) method?

The primary advantage is safety and convenience. MTBE is less toxic and less dense than chloroform. Its lower density means the lipid-containing organic phase forms the upper layer after phase separation, making it much easier and safer to collect without risk of disturbing the protein interphase or the lower aqueous phase [32] [33]. Furthermore, disposing of MTBE is considered more environmentally friendly.

Q4: How can I improve the reproducibility of my lipid extraction protocol?

Key strategies include:

- Automation: Using automated liquid handlers for solvent addition and phase collection can significantly reduce human error [35] [33].

- Internal Standards: Add a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (SILIS) mixture at the very beginning of extraction, before adding solvents, to correct for variations in extraction efficiency and ionization [32] [36].

- Standardized Washing: If washing the organic phase (e.g., with water or salt solution in the Folch method), keep the volume and ionic concentration consistent. The single-phase Alshehry method eliminates this step, which can reduce variability [32].

Q5: Can I use these methods for very small-volume plasma samples, such as from mice?

Yes, these methods can be successfully miniaturized. The Folch and Matyash methods have been reliably used with plasma volumes as low as 10-50 μL. A study successfully performed the single-phase Alshehry extraction using only 10 μL of pooled human plasma [32]. The key is to scale down the solvent volumes proportionally and use appropriate internal standards for accurate quantification in small sample analyses [35].

Experimental Data & Protocol Comparison

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Lipid Extraction Methods

| Parameter | Folch Method | Matyash Method | Single-Phase (Alshehry) Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Solvents | Chloroform/Methanol/Water (8:4:3 ratio after addition to sample) [32] | MTBE/Methanol/Water (10:3:2.5 ratio after addition to sample) [32] [33] | 1-Butanol/Methanol (1:1) + Water [32] |

| Solvent Toxicity | High (Chloroform is toxic) [32] | Moderate (MTBE is less toxic) [32] | Low (No chlorinated solvents) [32] |

| Organic Phase Location | Lower phase [32] | Upper phase [32] | Single phase (No separation) [32] |

| Extraction Efficiency (Relative Number of Metabolites) | Baseline (Conventional method) [33] | Comparable or 1-29% more than original Matyash [33] | Highly correlated with Folch (r² = 0.99) [32] |

| Reproducibility (Intra-assay CV%) | 15.1% (in positive ion mode) [32] | 21.8% (in positive ion mode) [32] | 14.1% (in positive ion mode) [32] |

| Key Advantage | Established benchmark; high efficiency for many lipids [32] [16] | Safer; lipid-rich top layer; good for sphingolipids [32] [16] | Simple, fast, no phase separation; good for polar lipids [32] |

Table 2: Detailed Protocol Steps for Folch and Matyash Methods

| Step | Folch (Chloroform-Based) Protocol | Matyash (MTBE-Based) Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Preparation | Homogenize 100 μL plasma (or tissue equivalent) [32] [28]. | Homogenize 100 μL plasma (or tissue equivalent) [32] [33]. |

| 2. Solvent Addition | Add 20 volumes of Chloroform:Methanol (2:1, v/v). For 100 μL sample, add 2 mL of solvent mixture [32] [16]. | Add 1 volume of Methanol (e.g., 100 μL) to the sample, vortex. Then add 3.3 volumes of MTBE (e.g., 330 μL) [32] [33]. |

| 3. Mixing & Incubation | Vortex vigorously for 10-30 seconds. Incubate for 10-60 minutes with shaking at room temperature [32]. | Vortex vigorously for 10-30 seconds. Incubate for 10-60 minutes with shaking at room temperature [32] [33]. |

| 4. Phase Separation | Add 0.2 volumes of water or saline (e.g., 0.4 mL for a 2 mL extraction). Vortex. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 minutes [32] [16]. | Add 1.25 volumes of water (e.g., 125 μL for a 100 μL sample). Vortex. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 minutes [32] [33]. |

| 5. Lipid Collection | Carefully collect the lower organic (chloroform) phase using a glass syringe or pipette, avoiding the protein interphase [32] [28]. | Carefully collect the upper organic (MTBE) phase using a glass syringe or pipette [32] [33]. |

| 6. Post-Processing | Evaporate solvent under a stream of nitrogen gas. Reconstitute dried lipids in a suitable solvent for analysis (e.g., isopropanol) [32]. | Evaporate solvent under a stream of nitrogen gas. Reconstitute dried lipids in a suitable solvent for analysis (e.g., isopropanol) [32]. |

Workflow Visualization

Biphasic Lipid Extraction Workflow for Plasma Samples - This diagram outlines the parallel procedural paths for the Folch and Matyash methods, highlighting the key difference in the final collection step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biphasic Lipid Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards (SILIS) | Corrects for extraction and ionization variability; enables accurate quantification [32] [36]. | SPLASH Lipidomix (deuterated PC, PE, PS, TG, SM, etc.) added prior to solvent addition [32]. |

| Chloroform (HPLC grade) | Primary non-polar solvent in Folch method; dissolves neutral lipids efficiently [32] [16]. | Used in 2:1 (v/v) ratio with methanol [32]. |

| Methanol (HPLC grade) | Polar solvent that disrupts hydrogen bonds between lipids and proteins; used in both Folch and Matyash [32] [16]. | Used in Folch (2:1 with CHCl₃) and Matyash (with MTBE) [32] [33]. |

| MTBE (HPLC grade) | Less toxic alternative to chloroform; forms the less-dense upper phase in Matyash method [32] [33]. | Used in original Matyash (10/3/2.5, v/v/v, MTBE/MeOH/water) and modified versions [32] [33]. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., BHT) | Prevents autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids during extraction and storage [28] [34]. | Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) at 50-100 μM concentration in solvents [34]. |

| Salt Solutions (e.g., KCl) | Used in washing steps (Folch) or to induce phase separation; adjusts ionic strength for cleaner partitioning [32] [16]. | 0.05 N NaCl or KCl used in Folch wash [32]. 0.9% saline used for phase induction [16]. |

| Glass Vials with Teflon-lined Caps | Prevents solvent evaporation and leaching of contaminants from plastic; essential for storage [28]. | Recommended for storage of tissues and lipid extracts to minimize contamination and oxidation [28]. |

| Simvastatin acid-d6 | Simvastatin acid-d6, MF:C25H40O6, MW:442.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NDI-101150 | NDI-101150, CAS:2628486-22-4, MF:C27H27FN6O2, MW:486.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Extraction Recovery for Specific Lipid Classes

Problem: Low recovery of lysophospholipids (LPC, LPE), acyl carnitines (AcCa), sphingomyelins (SM), and sphingosines (Sph) from plasma/serum samples.

Explanation: Different monophasic solvents have varying affinities for specific lipid classes due to their physicochemical properties. The polarity and composition of the solvent mixture directly impact which lipids are efficiently solubilized and extracted [2].

Solutions:

- For IPA and EE methods: Add stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-ISTDs) prior to lipid extraction to correct for recovery variations [2]. Consider switching to MMC protocol for more consistent broad-spectrum recovery.

- Optimize solvent-to-sample ratio: For plasma samples, ensure adequate solvent volume to completely precipitate proteins and solubilize lipids. Typical ratios range from 3:1 to 10:1 (solvent:sample) depending on method [37] [38].

- Implement cooling: Use cooled solvents and equipment to significantly improve lipid extraction efficiencies, as demonstrated in CSF lipid extraction studies [39].

Inconsistent Results and Poor Reproducibility

Problem: High variability in lipid quantification between technical replicates, particularly with IPA and EtOAc/EtOH (EE) methods.

Explanation: Monophasic extracts can contain salts and polar metabolites that may cause ion suppression in MS analysis. IPA and EE methods have demonstrated poor reproducibility for most tested tissues in comparative studies [2].

Solutions:

- Standardize mixing parameters: Optimize and strictly control vortexing or mixing times. Excessive mixing can cause lipid degradation, while insufficient mixing leads to incomplete extraction [39].

- Control temperature consistently: Perform extractions at controlled room temperature or on ice, depending on lipid stability. Document temperature conditions precisely.

- Add purification step: For particularly problematic samples, consider adding a phospholipid removal solid-phase extraction step after monophasic extraction, though this reduces throughput [38].

Emulsion Formation and Phase Separation Issues

Problem: Formation of stable emulsions during extraction, making it difficult to recover clean supernatant.

Explanation: While more common in biphasic systems, emulsions can occur in monophasic systems when samples contain high amounts of surfactant-like compounds (phospholipids, free fatty acids, triglycerides, proteins) [40].

Solutions:

- Gentle mixing: Swirl containers gently instead of vigorous shaking or vortexing to reduce emulsion formation while maintaining extraction efficiency [40].

- Centrifugation optimization: Increase centrifugation speed or duration. Typical parameters are 10,000-15,000 × g for 10-15 minutes at 4°C [41].

- Brine addition: For samples prone to emulsion, add small volumes of concentrated brine or salt water to increase ionic strength and break emulsions [40].

Matrix Effects and Ion Suppression in MS Analysis

Problem: Reduced MS signal for certain lipid classes due to co-eluting contaminants in crude extracts.

Explanation: Monophasic extracts are "less clean" compared to biphasic extracts as they contain salts, polar metabolites, and other water-soluble impurities that can cause ion suppression during ESI-MS analysis [2].

Solutions:

- Dilute-and-shoot approach: Dilute extracts 2-5 fold with reconstitution solvent to reduce matrix effects, though this may decrease sensitivity for low-abundance lipids.

- LC method adjustment: For RPLC-MS methods, ensure polar impurities elute at solvent front and do not interfere with lipid analysis by optimizing chromatographic conditions [2].

- SPE clean-up: For critical applications, add a rapid SPE clean-up step using phospholipid removal cartridges, accepting the trade-off in throughput [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which monophasic extraction method provides the best overall performance for plasma lipidomics?

A: Based on comparative studies, the MeOH/MTBE/CHCl3 (MMC) method generally provides better reproducibility and broader lipid coverage compared to IPA and EtOAc/EtOH (EE) for plasma samples [2]. However, method choice depends on your specific target lipid classes. For high-throughput applications where sample clean-up is less critical, simple methanol precipitation often shows broad specificity and outstanding accuracy [38].

Q2: How does sample matrix (plasma vs. serum) affect monophasic extraction efficiency?

A: Plasma is generally more suitable for metabolomics and lipidomics approaches combined with methanol-based methods [38]. Plasma shows different metabolite and lipid profiles compared to serum due to the coagulation process, which can release additional compounds and activate enzymes that modify the lipidome. The choice of matrix should be consistent throughout a study.

Q3: Can I use monophasic extraction for simultaneous metabolomics and lipidomics from a single sample?

A: While possible, it's challenging. Monophasic extracts contain both lipids and polar metabolites, but optimal analysis typically requires different LC-MS conditions for each domain. For integrated multi-omics, a single-step extraction with n-butanol:ACN (3:1, v:v) has been successfully used for the simultaneous extraction of metabolites and lipids, with subsequent on-bead protein digestion for proteomics [41].

Q4: What are the critical parameters to control for ensuring reproducibility in high-throughput applications?

A: Key parameters include: (1) consistent solvent-to-sample ratio, (2) controlled mixing time and intensity, (3) precise temperature control during extraction, (4) standardized centrifugation conditions, and (5) consistent evaporation and reconstitution procedures. Automated liquid handlers can significantly improve reproducibility for high-throughput applications [39] [37].

Q5: How do I choose between monophasic and biphasic extraction for my plasma lipidomics study?

A: Monophasic systems are preferred for high-throughput applications due to simpler handling and faster processing. They are particularly suitable when using LC-MS separation, as chromatographic steps can separate lipids from co-extracted contaminants. Biphasic methods (like Folch or MTBE) provide cleaner extracts and are better for shotgun lipidomics where samples are directly infused into the MS without chromatography [2].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized MMC Extraction Protocol for Plasma/Serum

Principle: This monophasic extraction using methanol, methyl tert-butyl ether, and chloroform efficiently precipitates proteins while extracting a broad range of lipid classes with good reproducibility [2].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw plasma/serum samples on ice. Vortex briefly.

- Aliquoting: Transfer 50 μL of plasma/serum to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Internal Standards: Add appropriate stable isotope-labeled internal standards (10-20 μL depending on concentration).

- Solvent Addition: Add 300 μL of MMC solvent (methanol:MTBE:chloroform, 8:5:2, v/v/v).

- Mixing: Vortex vigorously for 30 seconds, then shake on a platform shaker for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet proteins.

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully transfer supernatant to a new tube without disturbing the pellet.

- Evaporation: Evaporate to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen or using a vacuum concentrator.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute in 100 μL of appropriate LC-MS solvent (e.g., n-butanol:IPA:water, 8:23:69, v/v/v with 5 mM phosphoric acid for lipidomics) [41].

- Analysis: Vortex, centrifuge, and transfer to LC-MS vials for analysis.

High-Throughput 96-Well Format Adaptation

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Transfer 10-20 μL of plasma/serum to 96-well plate.

- Automated Liquid Handling: Use automated systems to add 200-300 μL of extraction solvent.

- Sealing and Mixing: Seal plate with silicone mat and mix on plate shaker for 15-20 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge plate at 3,000-4,000 × g for 15 minutes.

- Automated Transfer: Use liquid handler to transfer supernatants to clean 96-well collection plate.

- Evaporation: Evaporate in centrifugal vacuum concentrator with 96-well capability.

- Reconstitution: Automatically reconstitute in 50-100 μL appropriate solvent.

- Analysis: Direct injection from 96-well plate to LC-MS system.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Lipid Class Recovery Comparison Across Monophasic Extraction Methods [2]

| Lipid Class | IPA | MMC | EtOAc/EtOH | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | +++ | +++ | +++ | Comparable recovery |

| PE | ++ | +++ | ++ | MMC superior |

| LPC | + | ++ | + | Challenging for all methods |

| LPE | + | ++ | + | Add SIL-ISTDs recommended |

| TG | +++ | +++ | +++ | Excellent for all |

| DG | ++ | +++ | ++ | MMC optimal |

| SM | + | ++ | + | Lower with IPA and EE |

| Acyl Carnitines | + | ++ | + | MMC shows better recovery |

| Reproducibility | Low | High | Low | IPA and EE show poor reproducibility |

Table 2: Method Characteristics for High-Throughput Applications

| Parameter | IPA | MMC | EtOAc/EtOH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput Potential | High | High | High |

| Ease of Automation | Excellent | Good | Excellent |

| Sample Cleanliness | Low | Medium | Low |

| Reproducibility | Problematic | Good | Problematic |

| Recommended Internal Standards | SIL for LPC, LPE, AcCa, SM, Sph | SIL for quantification | SIL for LPC, LPE, AcCa, SM, Sph |

| Optimal Sample Type | Liver, Intestine [2] | Broad tissue compatibility | Limited application |

Workflow Visualization

Monophasic Extraction Workflow with Critical Control Points

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Monophasic Lipid Extraction

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Quality Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isopropanol (IPA) | Primary extraction solvent, protein precipitation | Shows poor reproducibility for some tissues; suitable for high-throughput [2] | HPLC grade or higher |

| Methanol | Component of MMC, protein precipitation | Improves extraction of polar lipids; common in solvent precipitation [38] | LC-MS grade |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Less hazardous than chloroform, organic phase | Used in MMC mixture; less dense than water [2] | HPLC grade |

| Chloroform | Lipid solubilization, traditional extraction | Component of MMC; hazardous but effective [2] | HPLC grade, stabilize with amylene |

| Ethyl Acetate | Extraction solvent in EE method | Shows poor reproducibility for most tissues [2] | HPLC grade |

| Ethanol | Polar solvent in EE method | Less common than methanol for lipidomics [38] | LC-MS grade |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Quantification correction, recovery monitoring | Essential for normalizing extraction variability; add before extraction [2] | Mixture covering major lipid classes |

| Ammonium Formate/Formic Acid | Mobile phase additive, ionization control | Improves chromatographic separation and MS detection [37] | LC-MS grade |

| Phosphoric Acid | Additive in reconstitution solvent | Enhances negative ion mode detection for acidic lipids [41] | LC-MS grade |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind the BUME method? The BUME method is a chloroform-free total lipid extraction technique that uses a mixture of butanol and methanol (BUME). It involves an initial one-phase extraction to solubilize lipids, followed by a secondary two-phase extraction using heptane:ethyl acetate and an acetic acid buffer. [23] [42] This solvent system is designed to create a lipid-enriched upper organic phase, simplifying recovery and making it ideally suited for automation with standard 96-well pipetting robots. [43] [23]