Solvent Accessibility and Hydrophobic Effects: Decoding the Key Drivers of Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity

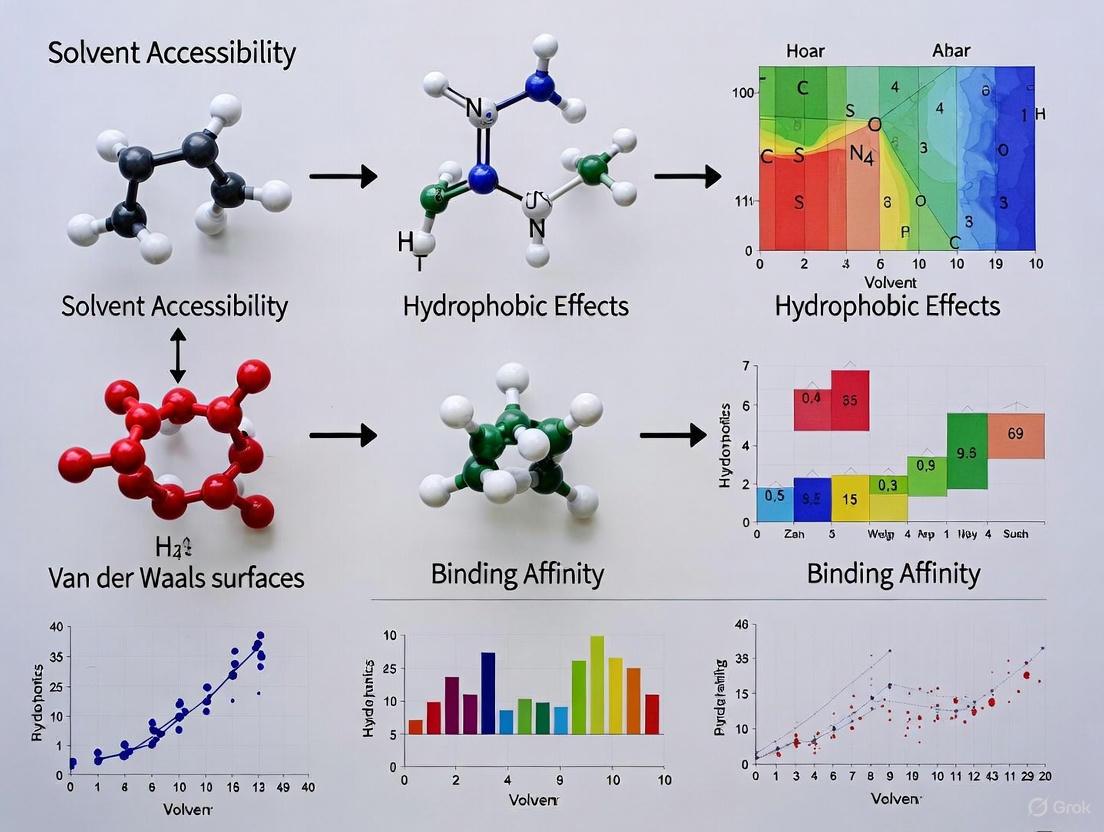

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical roles played by solvent accessibility and hydrophobic effects in determining protein-ligand binding affinity.

Solvent Accessibility and Hydrophobic Effects: Decoding the Key Drivers of Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical roles played by solvent accessibility and hydrophobic effects in determining protein-ligand binding affinity. We explore fundamental biophysical principles, from accurate solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) calculation to the molecular mechanisms of hydrophobic interactions. The review covers cutting-edge computational methodologies for binding affinity prediction, including machine learning approaches and enhanced sampling techniques that explicitly incorporate water molecules. We address common challenges in theoretical and empirical models, highlighting optimization strategies for improved accuracy. Through comparative validation against experimental data, we assess the performance of current predictive frameworks. This synthesis offers researchers and drug development professionals essential insights for advancing structure-based drug design and overcoming persistent challenges in binding affinity prediction.

The Biophysical Foundation: How Solvent Accessibility and Hydrophobic Effects Govern Molecular Interactions

The Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) represents a fundamental concept in molecular biology and biophysics, defined as the surface area of a biomolecule that is accessible to a solvent [1]. This geometric measure quantifies the degree to which atoms or amino acids within a protein are exposed to their aqueous environment, thereby serving as a critical parameter for understanding solvation effects, protein folding, and molecular recognition processes [2] [3]. The conceptual framework for SASA was first established by Lee and Richards in 1971, whose pioneering work introduced a method for interpreting protein structures through estimation of static accessibility [1]. This breakthrough provided researchers with an analytical approach to quantify how different regions of a protein interact with surrounding solvent molecules, creating what is sometimes referred to as the Lee-Richards molecular surface [1].

The relationship between SASA and biomolecular function emerges from fundamental thermodynamic principles. The burial of hydrophobic amino acids in the protein core constitutes a primary driving force in protein folding, while the extent to which an amino acid interacts with solvent versus the protein core is naturally proportional to the surface area exposed to these environments [2]. This connection makes SASA an essential parameter for calculating transfer free energy required to move a biomolecule from an aqueous solvent to a non-polar environment [1], and for understanding how osmolytes modulate protein stability through their interaction with solvent-exposed regions [4]. In the context of binding affinity research, the surface area buried upon complex formation directly correlates with interaction strength, highlighting SASA's critical role in molecular recognition processes [5].

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The Lee-Richards Breakthrough

The conceptual foundation of SASA emerged from the seminal 1971 work by Lee and Richards, who introduced a novel method for interpreting protein structures through estimation of static accessibility [1]. Their approach involved calculating the surface area accessible to water molecules by representing the solvent as a probe with finite size rolling over the van der Waals surface of the molecule. This methodological breakthrough provided, for the first time, an objective way to quantify the exposure of atoms and residues in protein structures, moving beyond qualitative descriptions of molecular surfaces [1]. The Lee-Richards method essentially extends the van der Waals radius for each atom by the radius of a solvent probe (typically 1.4Ã…, approximating a water molecule) and calculates the surface area of these expanded-radius atoms [2].

Evolution to the Rolling Ball Algorithm

The theoretical framework established by Lee and Richards was subsequently transformed into a practical computational algorithm by Shrake and Rupley in 1973 [1] [2]. Their implementation, known as the Shrake-Rupley algorithm, introduced a numerical method that draws a mesh of points equidistant from each atom of the molecule and uses the number of these points that are solvent accessible to determine the surface area [1]. This approach effectively simulates the process of "rolling a ball" along the molecular surface, where the ball represents a solvent molecule with a specified radius. The algorithm checks all generated points against the surfaces of neighboring atoms to determine whether they are buried or accessible, with the number of accessible points multiplied by the portion of surface area each point represents to calculate the final SASA value [1].

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in SASA Methodology

| Year | Researchers | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Lee & Richards | Introduced accessible surface area concept [1] | First theoretical framework for quantifying solvent accessibility |

| 1973 | Shrake & Rupley | Developed "rolling ball" algorithm [1] [2] | Practical numerical implementation for SASA calculation |

| 1983 | Connolly | Implemented 3D molecular surface calculation [1] | Advanced analytical molecular surface computation |

| 1999 | Weiser et al. | Introduced LCPO method [1] | Linear approximation for faster analytical SASA calculation |

| 2024 | Various | Developed dSASA algorithm [6] [7] | Exact analytical calculation with derivatives on GPUs |

The choice of probe radius significantly influences the calculated SASA values, as using a smaller probe radius detects more surface details and consequently reports a larger surface area [1]. Additionally, the definition of van der Waals radii for atoms in the molecule affects results, particularly for molecules that may lack hydrogen atoms, which are often implicit in the structure [1]. The discretization level, determined by the number of points created on the van der Waals surface of each atom, represents another factor influencing computational accuracy, where more points provide increased detail at the cost of greater computational requirements [1].

Computational Methods and Algorithms for SASA Calculation

Foundational Algorithms

The computational landscape for SASA calculation encompasses multiple algorithmic approaches with varying trade-offs between accuracy, speed, and implementation complexity. The Shrake-Rupley algorithm stands as a foundational numerical method that employs a spherical probe representing a solvent molecule rolled over the van der Waals surface of the molecule [1] [3]. This method generates a mesh of points equidistant from each atom and determines solvent accessibility by checking these points against neighboring atom surfaces [1]. The proportion of accessible points relative to the total generated provides the basis for SASA calculation. Key parameters influencing accuracy include the probe radius (typically 1.4Ã… for water), van der Waals radii definitions for different atoms, and the number of points generated on each atomic surface [1].

The Linear Combination of Pairwise Overlaps (LCPO) method, developed by Weiser et al. in 1999, represents an important advancement for rapid analytical SASA calculation [1]. This approach uses a linear approximation of the two-body problem to compute SASA more efficiently, achieving speeds suitable for molecular dynamics simulations while maintaining reasonable accuracy with errors typically in the range of 1-3 Ų [1]. The LCPO method has been widely adopted in software packages like AMBER for implicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations [1] [6]. Its principal advantage lies in being pairwise decomposable, making it suitable for energy minimization approaches that require derivative calculations [2].

Modern Computational Advances

Recent algorithmic developments have focused on improving both accuracy and computational efficiency, particularly for applications in molecular dynamics and structure prediction. The Neighbor Vector algorithm addresses limitations in neighborhood density-based approaches by accounting for spatial orientation of neighboring atoms, providing an optimal balance between accuracy and speed for protein structure prediction applications [2]. This method improves upon simple atom-counting approaches (such as counting atoms within a specific radius) by incorporating directional information to better model solvent exposure [2].

Table 2: Comparison of SASA Calculation Methods

| Method | Type | Key Features | Accuracy | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrake-Rupley | Numerical | Rolling ball algorithm with point mesh | High | General SASA calculation [1] |

| LCPO | Analytical | Linear combination of pairwise overlaps | Moderate (1-3 Ų error) [1] | MD simulations in AMBER [1] [6] |

| Neighbor Vector | Approximation | Considers spatial orientation of neighbors | Moderate | Protein structure prediction [2] |

| dSASA | Exact analytical | Alpha Complex theory, inclusion-exclusion | High (>98% accuracy) [6] [7] | Implicit solvent MD on GPUs [6] |

| Power Diagram | Analytical | Power diagram construction | High | Recent advanced implementations [1] |

A significant breakthrough emerged with the development of dSASA (differentiable SASA), an exact geometric method that calculates SASA analytically along with atomic derivatives on GPUs [6] [7]. This approach uses Delaunay tetrahedralization to assign atoms to groups of four, then calculates SASA values based on tetrahedralization information and inclusion-exclusion methods [6] [7]. The dSASA method reproduces numerical icosahedral-based SASA values with more than 98% accuracy for both proteins and RNAs while providing the analytical derivatives necessary for molecular dynamics simulations [6]. Implementation on GPUs has accelerated GB/SA simulations by nearly 20-fold compared to CPU versions, particularly outperforming LCPO as system size increases [6] [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Standard SASA Calculation Protocol

The accurate calculation of SASA requires careful attention to methodological details and parameter selection. For the widely used Shrake-Rupley algorithm, the standard protocol begins with molecular structure preparation, ensuring appropriate hydrogen atom placement and correct bond connectivity [1] [8]. The algorithm then expands atomic radii by the probe radius (typically 1.4Ã… for water) and generates a set of points on the van der Waals surface of each atom [1]. The density of these points determines the resolution of the calculation, with higher point densities providing more accurate results at greater computational cost [1]. Each point is tested for accessibility by checking for overlaps with neighboring atoms, and the accessible area is computed as the product of the number of accessible points and the area represented by each point [1].

For residue-specific SASA calculations, the protocol involves computing the per-residue SASA (rSASA) by summing contributions from all atoms within the residue [2] [8]. This approach enables classification of amino acid residues as buried or exposed based on threshold values, typically with buried residues defined as having less than 2 Ų solvent accessible surface area per side chain atom [3]. The results can be further normalized to generate relative solvent accessibility values, which compare the calculated SASA to reference values obtained from fully exposed residues in extended conformations [8].

SASA Calculation Workflow

Binding Interface Analysis Protocol

In the context of protein-protein interactions and binding affinity research, SASA calculations provide crucial information about interface characteristics [5]. The standard protocol for analyzing binding interfaces involves calculating the difference in accessible surface area (ΔASA) between the free and bound forms of a protein [3]. This is performed according to the Lee-Richards molecular surface definition using a probe radius of 1.4 Å at the atomic level [3]. The interface ASA is defined as the area of atoms comprising the binding surface, while ΔASA represents the area that becomes inaccessible to solvent upon binding [3].

The methodological steps for binding interface analysis include: (1) calculating SASA for each protein in its unbound state; (2) calculating SASA for the same proteins in the complexed state; (3) computing the buried surface area (BSA) as the difference between unbound and complexed SASA values; and (4) correlating BSA with experimentally determined binding affinities [5]. For consistent results, it is essential to use the same probe radius and atomic radii definitions across all calculations, and to properly handle conformational changes that may occur upon binding [5]. Residues with ΔASA > 0.1 Ų are typically identified as binding site residues [3].

SASA in Binding Affinity and Hydrophobic Effect Research

Correlation Between Buried Surface Area and Binding Affinity

Extensive research has established a direct correlation between the surface area buried upon complex formation and the binding affinity of protein-protein interactions [5]. Analysis of curated structural and thermodynamic data for 113 heterodimeric complexes reveals that as buried surface area increases, binding affinity increases (decrease in Kd) [5]. The smallest interfaces bury as little as 381 Ų with dissociation constants (Kd) around 1 mM, while the largest interfaces bury nearly 3393 Ų with Kd values as low as 3 pM [5]. Across this dataset, a least squares fit indicates a free energy change per unit area of approximately 1.6 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â² [5].

Further analysis reveals a significant relationship between interface size and energetic efficiency. The free energy per unit surface area buried, or "surface energy density," follows a distinct pattern: for interfaces burying less than 2000 Ų, the surface energy density decreases linearly as the total buried area increases, ranging from about 13 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â² for smaller interfaces to approximately 4 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â² for larger interfaces [5]. Beyond 2000 Ų of buried surface, the energy density levels off to a relatively constant value of 3-4 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â² [5]. This pattern suggests that smaller interfaces contain a higher proportion of energetically important "hot spot" residues compared to larger interfaces [5].

Table 3: Surface Energy Density Versus Buried Surface Area

| Buried Surface Area Range (Ų) | Surface Energy Density (cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â²) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| < 1000 | 10-13 | High proportion of hot spot residues |

| 1000-1500 | 7-10 | Moderate hot spot density |

| 1500-2000 | 4-7 | Decreasing hot spot fraction |

| > 2000 | 3-4 | Basal energy density; low hot spot fraction |

Context-Dependence of the Hydrophobic Effect

The hydrophobic effect demonstrates significant context dependence at protein-protein interfaces, with central regions exhibiting substantially greater hydrophobicity compared to peripheral areas [9]. This observation aligns with the O-ring hypothesis, which proposes that high-affinity binding requires solvent exclusion from interacting residues, leading to increased hydrophobicity at interface centers [9]. Experimental studies measuring hydrophobicity at central versus peripheral regions estimate values of 46 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â² and 21 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â², respectively, indicating twice the hydrophobic effect at the center [9]. This context dependence explains the characteristic clustering of hot spot residues at interface centers and has important implications for hot spot prediction and small molecule inhibitor design [9].

Notably, research shows no direct correlation between the percentage of hydrophobic surface area buried and either the total buried area or binding affinity across protein complexes [5]. The average percentage of hydrophobic buried surface is approximately 60% across interfaces of different sizes, suggesting evolutionary constraints may limit total hydrophobic surface area to prevent non-specific interactions and inappropriate aggregation when uncomplexed proteins expose their interfaces [5]. This finding indicates that hydrophobic interactions alone cannot explain binding affinity variations, with specific packing arrangements and polar interactions playing complementary roles in molecular recognition [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for SASA Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Software Suite | Molecular dynamics with LCPO/dSASA | Implicit solvent simulations [1] [6] |

| Shrake-Rupley Algorithm | Computational Method | Numerical SASA calculation | General SASA computation [1] |

| dSASA | Computational Method | Exact analytical SASA with derivatives | GPU-accelerated MD simulations [6] [7] |

| ICOSA Method | Computational Method | Numerical SASA reference standard | Validation of approximate methods [6] |

| 1.4 Ã… Probe Radius | Parameter | Represents water molecule size | Standard SASA calculation [1] [3] |

| VADAR | Analysis Tool | Protein structure analysis | SASA calculation and visualization [1] |

| MSMS | Software | Molecular surface calculation | Reference SASA values [2] |

| Obtusafuran methyl ether | Obtusafuran methyl ether, MF:C17H18O3, MW:270.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Calophyllic acid | Calophyllic acid, MF:C25H24O6, MW:420.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolution of Solvent Accessible Surface Area methodology from Lee-Richards theory to modern rolling-ball algorithms represents a significant advancement in computational structural biology. The concept has proven indispensable for understanding hydrophobic effects in protein folding, molecular recognition, and binding affinity research [5] [9]. Current trends indicate continued development of more accurate and efficient algorithms, particularly those capable of leveraging GPU acceleration for large-scale simulations [6] [7]. The integration of SASA-based energy terms into implicit solvent models has demonstrated improved stability in molecular dynamics simulations, addressing previous limitations in protein folding studies [6].

Future directions will likely focus on enhancing the accuracy of nonpolar solvation energy calculations, possibly through combined surface-area and volume-based approaches [6] [7]. Additionally, the development of methods applicable to diverse molecular systems beyond standard proteins, including nucleic acids, glycans, and small molecule ligands, represents an important frontier [6]. As these computational tools continue to evolve, SASA will remain a fundamental parameter for elucidating the relationship between molecular structure, solvation effects, and biological function, with particular relevance for drug development professionals seeking to understand and modulate molecular interactions.

The hydrophobic effect, a fundamental force governing molecular interactions in aqueous environments, has evolved in its theoretical understanding from simple "iceberg" formations to sophisticated models of entropy-enthalpy compensation. This review traces the conceptual development of hydrophobic interactions, examining how classical views of water structure reorganization around non-polar solutes have been refined through modern research revealing complex thermodynamic behavior. Within the context of solvent accessibility in binding affinity research, we analyze how size-dependent hydrophobic interactions and their characteristic entropy-enthalpy compensation patterns directly influence molecular recognition, protein folding, and ligand-receptor interactions. The integration of advanced computational and experimental methodologies has provided unprecedented insight into the molecular mechanisms driving these processes, offering valuable frameworks for rational drug design and biomolecular engineering.

Hydrophobic interactions represent one of the most significant driving forces in chemical and biological systems, influencing phenomena ranging from molecular recognition and protein folding to surfactant aggregation and membrane stability [10]. The historical concept of hydrophobicity emerged from observations of the limited solubility of nonpolar substances in water, leading to the empirical calculation of partition coefficients (logP) that remain widely used in drug design and medicinal chemistry [10]. The physical origin of this effect, however, has undergone substantial theoretical refinement since the mid-20th century.

In contemporary research, understanding the hydrophobic effect is particularly crucial for investigating solvent accessibility and binding affinity in biological systems. Water is increasingly recognized not as a passive bystander but as an active participant in binding events, often mediating interactions between ligands and their receptor sites [11] [12]. The displacement and reorganization of water molecules during binding processes create distinct thermodynamic signatures that can be exploited for therapeutic design. This review examines the evolution of hydrophobic effect theories, with particular emphasis on their implications for predicting and optimizing molecular interactions in drug development.

From Icebergs to Structural Competition: Evolving Theoretical Frameworks

Classical "Iceberg" Model and Its Evolution

The seminal "iceberg" model proposed by Frank and Evans in 1945 suggested that water forms a kind of "cage" or structured arrangement around nonpolar solutes, analogous to gas clathrates [10]. This model emerged from observations of large negative entropy changes during hydrocarbon transfer into aqueous environments. The classical view of hydrophobic interactions held that as two such "caged" hydrophobes approach each other, the structured water between them is released into the bulk, resulting in an entropy increase that drives the association [10]. This interpretation positioned hydrophobic interactions as primarily entropy-driven at room temperature.

However, empirical evidence began challenging this simplistic view. Studies by Diederich et al. demonstrated that benzene complexation in a cyclophane host molecule was enthalpy-driven at room temperature, accompanied by a slightly negative entropy change [10]. Similarly, molecular dynamics simulations of hydrophobic receptor-ligand systems revealed associations driven by enthalpy and opposed by entropy [10]. These "non-classical" hydrophobic effects were attributed to the release of weakly hydrogen-bonded water molecules into the more strongly hydrogen-bonded bulk water [10], highlighting the nuanced role of water restructuring in hydrophobic interactions.

Size-Dependent Hydration Behavior

Modern theoretical approaches have revealed that hydrophobic effects exhibit significant dependence on solute size, a crucial consideration for binding affinity research:

Table 1: Size-Dependent Hydration Behavior

| Solute Size | Hydration Free Energy Relationship | Primary Driving Force | Molecular Distribution in Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small solutes | Grows linearly with solvated volume | Entropy-dominated | Dispersed distribution |

| Large solutes | Grows linearly with solvated surface area | Enthalpy-dominated | Accumulated distribution |

The crossover between these regimes occurs at the nanometer length scale [10], suggesting different theoretical frameworks are needed to describe hydrophobic interactions for small molecules versus extended hydrophobic surfaces. This size dependence has profound implications for molecular recognition, where both small molecule ligands and protein binding pockets span this size range.

Structural Competition Model

Current understanding suggests hydrophobic effects originate from structural competition between hydrogen bonding in interfacial versus bulk water [10]. When a solute is embedded in water, an interface forms that primarily affects the structure of the topmost water layer. The hydration free energy derived from this interfacial water structure provides the driving force for hydrophobic interactions, with different solvation processes (initial and hydrophobic) occurring as solute size increases [10].

Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation in Hydrophobic Interactions

Thermodynamic Fundamentals

The Gibbs free energy equation (ΔG = ΔH - T·ΔS) provides the fundamental framework for understanding hydrophobic interactions. The overall free energy change incorporates contributions from water-water, solute-water, and solute-solute interactions [10]. In hydrophobic association, the complex balance between these components gives rise to the phenomenon of entropy-enthalpy compensation, where favorable changes in one thermodynamic parameter are offset by opposing changes in the other.

The dissolution of hydrophobic substances involves cavity formation in the solvent, displacing nw water molecules. This process exhibits characteristic entropy/enthalpy compensation linearly dependent on temperature [13]. The apparent enthalpy change (ΔHapp) demonstrates a non-zero, positive ΔCp,app, which can be expressed as ΔCp,app = nwCp,w, where Cp,w represents the isobaric heat capacity of water [13]. The number of displaced water molecules (nw > 0) correlates with solute size and thus cavity dimensions.

Table 2: Thermodynamic Parameters in Hydrophobic Interactions

| Parameter | Symbol | Relationship | Experimental Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy change per water molecule | Δscav | ΔScav = -23.2 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹Â·nwâ»Â¹ | -23.2 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹ per water molecule [13] |

| Entropy change for cavity contraction | Δsfill | ΔSfill = 22.4 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹Â·âŽ¹nw⎸â»Â¹ | 22.4 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹ per water molecule [13] |

| Apparent heat capacity | ΔCp,app | ΔCp,app = nwCp,w | Proportional to number of water molecules displaced [13] |

Molecular Interpretation of Compensation

The molecular basis for entropy-enthalpy compensation lies in the behavior of water molecules surrounding hydrophobic solutes. Cavity formation is associated with a negative entropy change (Δscav = -23.2 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹Â·nwâ»Â¹), while cavity contraction during processes like micellization or protein folding yields a positive entropy change (Δsfill = 22.4 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹Â·âŽ¹nw⎸â»Â¹) [13]. This positive entropy change during cavity contraction constitutes the main driving force for what is traditionally termed the "hydrophobic bond."

For protein folding and protein-substrate association, the behavior resembles micellization (nw < 0), where the consolidated hydrophobic interface reduces the total excluded volume, allowing some water molecules to be reintroduced into the bulk solvent structure [13]. This release of constrained water generates the characteristic entropy gain that dominates the free energy change at room temperature.

Temperature Dependence and Hydration Dynamics

The thermodynamic signature of hydrophobic interactions exhibits complex temperature dependence. Beyond a compound-specific minimum temperature (Tmin), the hydration process becomes endothermic [13]. The highly negative entropy change at Tmin (where ΔHapp = 0) relates to the loss of kinetic energy when solute molecules become trapped in their hydration cages [13].

Advanced computational approaches now enable direct calculation of enthalpic and entropic contributions to hydrophobicity. Molecular Dynamics simulations combined with Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) allow researchers to compute these contributions directly from the phase space occupied by water molecules, rather than deriving them indirectly from temperature dependence [14]. This methodology identifies regions with specific enthalpic and entropic properties, including "unhappy water" molecules characterized by weak enthalpic interactions and unfavorable entropic constraints [14].

Methodological Approaches: Experimental and Computational Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Hydration Analysis

Protocol Objective: To calculate spatially resolved enthalpic and entropic contributions to hydrophobicity using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST).

System Preparation:

- Molecular Model: Construct amino acid or target molecule including backbone atoms (essential for reliable results) [14].

- Solvation: Employ TIP3P, TIP4P, or TIP5P water models in a simulation box with periodic boundary conditions [14].

- Force Field: Apply AMBER force field parameters for both solute and solvent interactions [14].

Simulation Procedure:

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent algorithm to remove atomic clashes.

- Equilibration: Conduct gradual heating from 0K to 300K over 100ps in NVT ensemble, followed by density equilibration for 1ns in NPT ensemble at 1 bar.

- Production Run: Execute extended simulation (typically 50-100ns) in NPT ensemble at 300K and 1 bar, saving trajectories at 1-10ps intervals for analysis [14].

GIST Analysis:

- Grid Setup: Define a rectangular grid encompassing the solute molecule with 0.5Ã… resolution.

- Trajectory Processing: Align simulation frames to solute coordinates to remove global translation/rotation.

- Thermodynamic Calculation: For each grid voxel, compute:

- Solute-water interaction energy (ΔESW)

- Water-water enthalpy change (ΔEWW)

- Translational entropy (ΔStrans) from water oxygen distributions

- Orientational entropy (ΔSorient) from water molecule orientations [14]

This protocol enables direct identification of hydrophobic regions through characteristic patterns of weak solute-water interactions but favorable entropy from released water constraints.

Binding Kinetics Analysis with Hydration Fluctuations

Protocol Objective: To characterize the role of solvent fluctuations in hydrophobic cavity-ligand binding kinetics using explicit-water MD simulations.

System Setup:

- Model Construction: Create a simplified hydrophobic pocket-ligand system with concave-convex geometry to mimic key-lock association [11].

- Coordinate Definition: Establish reaction coordinate (z) with origin at pocket mouth and target position deep inside pocket (z = -5Ã…) [11].

Simulation and Analysis:

- Equilibrium Simulations: Run multiple independent explicit-water MD simulations to observe spontaneous binding/unbinding events.

- Mean First Passage Time (mfpt) Calculation: For each starting position z, compute average time for ligand to reach binding site:

- Track ligand position relative to pocket mouth

- Calculate distribution of binding times from multiple trajectories [11]

- Potential of Mean Force (PMF): Determine free energy profile along z coordinate using umbrella sampling or adaptive biasing methods [11].

- Diffusivity Profiling: Under Markovian assumption, calculate position-dependent diffusivity using:

D(z) = -kBT / [mfp't(z) × PMF'(z)]

where mfp't(z) is the derivative of the mfpt distribution and PMF'(z) is the mean force [11].

This approach reveals how hydration fluctuations create position-dependent friction that significantly influences binding kinetics beyond the effects captured by the PMF alone.

Biological Implications and Research Applications

Hydrophobic Interactions in Molecular Recognition

Water-mediated hydrophobic interactions play crucial roles in biological recognition processes. In hydrophobic cavity-ligand binding, the concave pocket exhibits wet/dry hydration oscillations whose magnitude and timescale amplify as ligands approach [11]. This coupling between ligand motion and slow hydration fluctuations creates increased friction near the pocket entrance, substantially decelerating association even in barrierless systems [11]. These hydrodynamic coupling effects may provide biological timing mechanisms for conformational adjustments in induced-fit binding paradigms.

Molecular dynamics simulations of generic hydrophobic pocket-ligand systems reveal that binding involves expulsion of highly distorted water networks from the pocket, generating characteristic enthalpic signatures [11]. The resulting friction profile peaks at the pocket entrance, with local diffusivity decreasing up to sixfold compared to bulk solution [11]. This position-dependent friction must be incorporated into kinetic models for accurate prediction of binding rates.

Role in Protein Folding and Complex Assembly

The hydrophobic effect provides the primary driving force for protein folding through the burial of nonpolar residues. During folding, the consolidated hydrophobic core reduces the total excluded volume, analogous to micellization (nw < 0) [13]. This consolidation releases constrained water molecules into the bulk, generating a positive entropy change that dominates the folding free energy at physiological temperatures.

In voltage-sensing phosphatases (VSPs), hydrophobic residues create a "hydrophobic spine" at the membrane interface that enables coupling between voltage sensing and enzymatic domains [15]. Molecular dynamics simulations show this hydrophobic spine exhibits compromised nature—despite its hydrophobicity, it maintains loose association with the bilayer surface, providing hinge-like motion for the cytoplasmic domain [15]. Mutational studies confirm that hydrophobicity and aromatic character at this spine are essential for voltage-dependent phosphatase activity [15], illustrating how precise hydrophobic matching enables biological function.

Implications for Drug Design

In structure-based drug design, understanding hydrophobic hydration is essential for predicting binding affinities. Displacement of unfavorable water molecules from hydrophobic binding pockets contributes significantly to binding free energy, particularly when the pocket contains highly ordered water molecules with constrained dynamics [11] [14]. The spatial resolution of hydrophobic character enabled by GIST analysis allows identification of specific regions where ligand modifications can maximize hydrophobic interactions while maintaining optimal physicochemical properties.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hydrophobic Effect Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER Force Field | Parameterizes molecular interactions for simulations | Molecular dynamics of biomolecules [14] |

| TIP3P/TIP4P Water Models | Represents water structure and hydrogen bonding | Explicit solvent simulations [14] |

| Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) | Calculates spatially resolved thermodynamics | Hydration analysis from MD trajectories [14] |

| Coarse-Grained (CG) MD | Simulates longer timescales and larger systems | Membrane-protein interactions [15] |

| Voltage-Sensing Phosphatases (VSPs) | Model system for hydrophobic coupling mechanisms | Membrane-mediated allostery [15] |

| Fluorescent PIP Sensors | Measures phosphoinositide phosphatase activity | VSP enzymatic activity assays [15] |

The understanding of hydrophobic effects has evolved substantially from the classical iceberg model to contemporary views emphasizing entropy-enthalpy compensation and size-dependent behavior. Current research recognizes hydrophobic interactions as arising from structural competition between interfacial and bulk water, with thermodynamic signatures determined by complex relationships between solute size, geometry, and surface chemistry. These insights fundamentally shape our approach to predicting and optimizing binding affinities in biological systems.

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating high-resolution structural data with dynamic information about water networks in binding sites. Advances in simulation methodologies, particularly in capturing non-Markovian effects in hydration dynamics, will improve kinetic predictions for drug binding. Furthermore, the development of multi-scale models that bridge from atomic-level water interactions to macroscopic hydrophobic phenomena will enhance our ability to engineer molecular recognition in both biological and synthetic systems. As these methodologies mature, they will provide increasingly powerful tools for exploiting hydrophobic effects in therapeutic design, protein engineering, and materials science.

The calculation of binding affinity between proteins and ligands is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and structural biology. A critical, yet often overlooked, component in these calculations is the accurate normalization of residue-specific Accessible Surface Area (ASA). This whitepaper delineates how the choice of normalization scale—contrasting context-free extended state models against context-dependent observed maxima—fundamentally alters the derived thermodynamic parameters and predictive accuracy of binding affinity models. Framed within the broader context of solvent accessibility and hydrophobic effects, we present quantitative evidence that adopting structurally-realistic, context-dependent reference states significantly enhances the performance of machine learning models in predicting mutation impacts on ligand binding and protein stability. The findings underscore the necessity of moving beyond simplistic normalization schemes to advance the precision of computational biophysics.

The hydrophobic effect is a central driver of biomolecular recognition, folding, and stability [16]. Its quantitative assessment often hinges on accurately measuring the burial of non-polar surface area upon binding or folding. The Accessible Surface Area (ASA) of an amino acid residue, defined as the surface area accessible to a solvent molecule, serves as a key metric in these calculations. To compare residues of different sizes and intrinsic areas, absolute ASA values (typically in Ų) are normalized to a Relative Solvent Accessibility (RSA), expressed as a percentage.

The choice of reference value for this normalization is not merely a procedural detail; it is a molecular determinant that directly influences the computed energy of hydrophobic interactions, the assessment of residue burial, and consequently, the predicted binding affinity. Traditional methods have largely relied on context-free reference states derived from extended tri-peptide conformations (e.g., Ala-X-Ala). However, a growing body of evidence suggests that these idealized states poorly represent the structural constraints present in natively folded proteins, leading to systematic errors [17].

This guide examines the impact of residue-specific ASA normalization scales, placing them within the critical framework of hydrophobic effects and binding affinity research. We detail the methodologies for deriving different scales, present quantitative comparisons of their performance, and provide protocols for their implementation in modern computational workflows, demonstrating that a more nuanced approach to ASA normalization is essential for accurate predictive modeling in drug development.

Core Concepts: ASA Normalization Scales and the Hydrophobic Effect

Defining ASA and Its Role in Binding

The solvent accessible surface area (ASA) is computed by rolling a probe (typically with the radius of a water molecule, ~1.4 Ã…) over the van der Waals surface of a protein. Upon binding or folding, the reduction in ASA (ΔASA) of non-polar groups correlates with the favorable change in binding free energy due to the hydrophobic effect. This relationship is often quantified using an empirical energy density of approximately -20 to -33 cal molâ»Â¹ Ã…â»Â² [16]. The accuracy of this energy calculation is therefore directly dependent on the accurate assessment of ASA changes.

Traditional vs. Context-Dependent Reference States

Extended State ASA (ESA): This is the conventional reference state. The ASA for a residue 'X' is calculated in an extended tri-peptide conformation, typically Gly-X-Gly or Ala-X-Ala, which is assumed to represent its maximally exposed state. The RSA is then calculated as:

- RSA(ESA) = (ASAobserved / ASAAla-X-Ala) × 100%

- This approach is context-free; it ignores the influence of a residue's specific sequence neighborhood in a folded protein.

Highest Observed ASA (HOA): This method proposes a context-dependent reference state. The maximum ASA for a residue 'X' is derived from statistical analysis of its highest observed exposure across a large, high-quality database of native protein structures. Crucially, this maximum can be determined for each of the 400 possible tri-peptide environments (i-1, X, i+1), acknowledging that the flanking residues impose structural constraints.

- RSA(HOA) = (ASAobserved / ASAHOA_tri-peptide-context) × 100%

- This method recognizes that the ESA is a theoretical maximum that is often unattainable in real protein structures due to chain connectivity and local steric and dihedral constraints [17].

Table 1: Comparison of ASA Normalization Reference States

| Feature | Extended State ASA (ESA) | Highest Observed ASA (HOA) |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Theoretical, extended tri-peptide (e.g., Ala-X-Ala) | Empirical, from observed maxima in native protein structures |

| Sequence Context | Ignored (context-free) | Explicitly considered for all 400 tri-peptide combinations |

| Physical Realism | Represents an unconstrained, unfolded state | Represents the realistically achievable exposure in a folded context |

| RSA Range | Can exceed 100% for some residues in native structures | Bounded at 100%, representing the empirically observed maximum |

The Hydrophobic Effect and Its Energetic Interpretation

The hydrophobic effect is traditionally considered an entropy-driven process. However, studies on rigid protein-ligand systems, such as carbonic anhydrase complexed with sulfonamides, have revealed that the burial of hydrophobic surface area can be enthalpy-driven [16]. In these cases, the binding affinity gain is tied to the displacement and reorganization of water molecules that were structured in the binding pocket but in an enthalpically unfavorable state compared to bulk water. The accurate calculation of ΔASA is paramount for correctly attributing these energetic contributions. Misnormalization of ASA can lead to incorrect estimates of the hydrophobic driving force, confounding the interpretation of binding thermodynamics.

Quantitative Data and Performance Comparison

The theoretical superiority of context-dependent normalization is borne out by empirical data. A landmark study systematically compared the performance of ESA and HOA normalization by training neural networks to predict ASA from protein sequence.

Table 2: Prediction Performance: HOA vs. ESA Normalization [17]

| Residue Type | Correlation Coefficient (HOA) | Correlation Coefficient (ESA) | Performance Gain with HOA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cysteine (C) | 0.61 | 0.55 | +10.9% |

| Tryptophan (W) | 0.62 | 0.56 | +10.7% |

| Isoleucine (I) | 0.64 | 0.59 | +8.5% |

| Average (All Residues) | - | - | ~5% Overall Improvement |

The data demonstrates a clear and significant improvement in prediction accuracy when models are trained with HOA-normalized data. The improvement is particularly pronounced for residues with bulky or complex side chains (e.g., Cysteine, Tryptophan), whose maximal exposure is highly sensitive to local sequence context.

Furthermore, the biological relevance of HOA normalization is validated by its improved capacity to identify functional regions. Studies show that defining burial and exposure using HOA-based thresholds leads to better enrichment of DNA-binding sites among exposed residues compared to ESA-based thresholds [17]. This confirms that context-dependent normalization more accurately captures the structural and functional constraints of real proteins.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Deriving a Context-Dependent HOA Scale

This protocol details the creation of a residue-specific, context-dependent HOA normalization scale from a structural database.

Curate a High-Quality, Non-Redundant Protein Structure Set:

- Source: Retrieve protein structures from the PDB.

- Quality Filters: Select structures solved by X-ray crystallography with a resolution of ≤ 2.0 Å and an R-factor of ≤ 0.25. Prefer structures with complete coordinate data and no missing atoms in the main chain to ensure accurate ASA computation [17].

- Redundancy Reduction: Use a tool like

blastclustto cluster sequences at a 25% identity threshold, selecting a representative structure from each cluster to avoid bias.

Compute Absolute ASA Values:

- Tool: Use a program like DSSP [18] or

freeSASAto calculate the absolute ASA for every residue in every structure. - Parameters: Employ a standard water probe radius of 1.4 Ã….

- Tool: Use a program like DSSP [18] or

Compile Context-Dependent HOA Statistics:

- For each residue of type 'X' in every protein, record its absolute ASA and its tri-peptide context (residue types at positions i-1 and i+1).

- For each of the 400 possible tri-peptide combinations, compile the distribution of observed ASA values for the central residue 'X'.

- Define HOA: For each tri-peptide context, define the HOA value as the 99th percentile or maximum of the observed ASA distribution. This becomes the context-specific reference value.

Build the Normalization Scale:

- The final output is a lookup table mapping all 8000 possible tri-peptide sequences (20 x 20 x 20) to their respective HOA reference values.

Protocol 2: Implementing ASA Normalization in a Binding Affinity Prediction Workflow

This protocol integrates a residue-specific ASA scale into a machine learning pipeline for predicting the impact of mutations on binding affinity, similar to the approach used in PSnpBind-ML [19].

Feature Engineering:

- System Representation: Encode the protein-ligand complex using 256+ features. A critical subset of these should be ASA-related.

- ASA Feature Calculation:

- For a given mutation in the binding site, compute the wild-type and mutated protein structures (e.g., via homology modeling or quick energy minimization).

- Calculate the absolute ASA for the wild-type and mutated residue in their respective structural contexts.

- Normalize: Use a pre-computed HOA scale (from Protocol 1) to convert these absolute ASAs to RSA. The HOA value should be selected based on the residue's local tri-peptide context.

- Derived Features: Use the normalized RSA values directly, and also calculate the ΔRSA (RSAmutant - RSAwild-type) as a feature representing the change in solvent exposure.

Model Training and Prediction:

- Architecture: Employ a multi-modal framework. For instance, use one regression model to predict wild-type protein-ligand affinity and a second to predict the mutated affinity, with the ΔRSA feature informing the second model [19].

- Training: Train the model on a large-scale database of docking experiments or experimental binding affinities.

- Validation: The model should report high performance, with benchmarks such as an RMSE within 0.5-0.6 kcal/mol and an R² of 0.87-0.90 on independent test sets, demonstrating the utility of the engineered features [19].

Diagram 1: ASA Normalization Workflow. This flowchart outlines the general process of converting a raw protein structure into a normalized Relative Solvent Accessibility (RSA) value, highlighting the critical choice between context-free (ESA) and context-dependent (HOA) normalization scales, and the subsequent use of this data in key research applications.

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Datasets for ASA Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ASA Normalization |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSSP [18] | Software | Calculates secondary structure and solvent accessibility from 3D structure. | The standard tool for computing absolute ASA values from PDB coordinate files. |

| PDBbind [20] | Database | A curated database of protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data. | Provides a benchmark dataset for training and validating binding affinity prediction models that use ASA features. |

| PSnpBind Database [19] | Database | Contains hundreds of thousands of docking experiments for protein variants. | A large-scale resource for studying the effect of binding site mutations, ideal for developing models like PSnpBind-ML. |

| dMaSIF [20] | Software/Surface Algorithm | A deep learning-based method for processing molecular surfaces as point clouds. | Used in advanced workflows to extract geometric and chemical features from protein surfaces, which can be integrated with ASA data. |

| HOA Scale Data [17] | Dataset | A lookup table of Highest Observed ASA values for tri-peptide contexts. | The core reference data required for implementing context-dependent ASA normalization as described in this guide. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The integration of sophisticated, context-dependent ASA normalization directly impacts the efficiency and success of drug discovery pipelines.

Improved Prediction of Mutation Impacts: A significant challenge in drug development is accounting for genetic variation in drug targets. Methods like PSnpBind-ML, which leverage carefully engineered features including ASA, can rapidly screen ligands against a panel of protein variants (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms). This helps identify potential leads with consistent affinity across populations and anticipate drug resistance mechanisms [19]. The accuracy of such models is heightened by precise ASA normalization.

Enhanced Assessment of Pathogenicity: Solvent accessibility is a strong predictor of the functional impact of missense mutations. Disease-associated variants are statistically significantly more likely to occur at buried residues (RSA < 20%) compared to neutral polymorphisms [18]. Using a realistic HOA scale to define "buried" improves the signal-to-noise ratio in bioinformatic tools for prioritizing pathogenic variants.

Guiding Protein Engineering: In biologics development, optimizing binding affinity and thermal stability is crucial. The spatial organization of hydrophobic and charged residues, quantified by their ASAs, correlates with thermal stability (Tm) and binding affinity (Kd) [21]. Accurate ASA metrics allow for more reliable in silico screening of engineered protein variants, reducing the experimental burden.

Diagram 2: Predicting Mutation Impacts. This diagram illustrates a modern application of context-dependent ASA, where it is used as a critical input feature for machine learning models that predict how genetic variations in a protein target will affect drug binding, enabling precision medicine.

The normalization of solvent accessibility is far from a mundane preprocessing step in computational biology. The evidence is clear: the transition from context-free, residue-type-only (ESA) scales to context-dependent, statistically derived (HOA) scales yields tangible improvements in the prediction of solvent accessibility from sequence, the assessment of mutation pathogenicity, and the accuracy of binding affinity calculations. As the field moves towards multi-modal deep learning models that integrate sequence, structure, and surface information [20], the precision of foundational features like ASA becomes ever more critical. By adopting these more sophisticated normalization methodologies, researchers and drug developers can achieve a more realistic and predictive understanding of the molecular determinants of biomolecular interaction, ultimately de-risking and accelerating the journey from target to therapeutic.

This technical guide examines the fundamental crossover in solute behavior within aqueous environments, a critical phenomenon driven by hydrophobic effects. The transition from a dispersed state for small solutes to an accumulated state for large solutes is governed by changes in the hydration free energy, which in turn is dictated by the competition between the hydrogen-bonding structures of interfacial water and bulk water [10]. This size-dependent behavior has profound implications for understanding molecular recognition, protein folding, and the binding affinity of ligands to hydrophobic pockets in drug development [11] [10]. The following sections provide a detailed analysis of the underlying thermodynamics, quantitative data on the crossover scale, and methodologies for probing these phenomena.

Hydrophobic interactions, the tendency of nonpolar molecules or molecular regions to aggregate in water, are a fundamental driving force in numerous chemical and biological processes [10]. These include protein folding, the formation of biological membranes and micelles, and, most critically for drug development, molecular recognition and ligand binding [11] [10]. The role of water in these processes is not passive; it is an active constituent that mediates interactions through its unique hydrogen-bonding network.

The classical "iceberg" model proposed by Frank and Evans suggested that water forms a structured "cage" around small hydrophobic solutes, leading to a loss of entropy [10]. Hydrophobic attraction was thus historically considered entropy-driven, resulting from the release of these structured water molecules upon solute association. However, contemporary research reveals a more complex picture. Studies on hydrophobic receptor-ligand systems have shown that association can be enthalpy-driven and opposed by entropy at room temperature [10]. This "non-classic" hydrophobic effect is attributed to the release of weakly hydrogen-bonded water molecules from a hydrophobic binding pocket into the more strongly hydrogen-bonded bulk water [10] [11]. The reconciliation of these views lies in understanding the size-dependent nature of hydration, which is the central theme of this whitepaper.

Theoretical Framework: Thermodynamics and Solute Size

The thermodynamic driving force for any process in solution, including solute dispersion or accumulation, is described by the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG), as shown in Equation 1 [10].

Equation 1: Gibbs Free Energy

Here, ΔH represents the enthalpy change, T is the temperature, and ΔS is the entropy change.

For a solute in aqueous solution, the total Gibbs free energy can be decomposed into contributions from various interactions, as detailed in Equation 2 [10].

Equation 2: Total Gibbs Free Energy of System

The hydrophobic interaction that drives solute accumulation is primarily encapsulated in the ΔG(Water-water) and ΔG(Solute-water) terms. The key differentiator between small and large solutes is the character of the hydration free energy (ΔG_hyd), which is the free energy change associated with transferring a solute from a gaseous reference state into water.

- Small Solutes (Dispersed State): For solutes with dimensions on the order of ~1 nm or smaller, the hydration free energy is favorable and scales linearly with the solvated volume of the solute. Water molecules can rearrange around the solute without significant breaking of hydrogen bonds, leading to a stable dispersed state [10].

- Large Solutes (Accumulated State): For solutes with dimensions greater than ~1 nm, the hydration free energy becomes unfavorable and scales linearly with the solvated surface area. The curvature of the solute surface is too low, forcing the breaking of hydrogen bonds in the interfacial water layer and resulting in a substantial enthalpic penalty. This makes the hydrated state unstable, driving solutes to accumulate and minimize the total hydrophobic surface area exposed to water [10].

This transition represents a crossover from entropy-dominated hydration for small solutes to enthalpy-dominated hydration for large solutes.

Quantitative Data and Analysis

The following tables summarize the key quantitative relationships and parameters that define the size-dependent crossover in solute behavior.

Table 1: Scaling Behavior of Hydration Free Energy with Solute Size

| Solute Size Regime | Scaling of ΔG_hyd | Thermodynamic Driver | Observed Solute Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Solutes (≤ ~1 nm) | Linear with Volume [10] | Entropy Gain (Classical) [10] | Dispersed Distribution [10] |

| Large Solutes (> ~1 nm) | Linear with Surface Area [10] | Enthalpy Penalty (Non-Classical) [10] | Accumulated/Aggregated Distribution [10] |

Table 2: Key Parameters from Molecular Dynamics Studies of Hydrophobic Binding

| Parameter | Value / Relationship | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Crossover Length Scale | ~1 nanometer (nm) [10] | The approximate solute size at which the scaling of ΔG_hyd transitions from volume to surface area. |

| Local Diffusivity Slowdown | D(z) decreases by a factor of 6 near pocket entrance [11] | Measured local ligand diffusivity drops from bulk ~0.65 Ų/ps to a minimum of ~0.1 Ų/ps, drastically slowing association kinetics [11]. |

| Hydration Fluctuation Timescale | Picoseconds to hundreds of nanoseconds [11] | Time scale of "wet/dry" oscillations in a hydrophobic pocket; depends on cavity size and geometry and couples to ligand motion [11]. |

| Hydrophobic Driving Force | Attractive force of ~2.5 kBT/Ã… [11] | The strong, linear free energy decrease inside a hydrophobic pocket (for z < 0) that drives binding [11]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations for Binding Kinetics

Explicit-water MD simulations are a powerful tool for investigating the role of solvent in ligand binding to hydrophobic cavities at the molecular level [11].

1. System Setup:

- Model Construction: Create a simplified model system featuring a prototypical hydrophobic concave pocket and a complementary ligand [11].

- Solvation: Embed the model system in a simulation box filled with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E models).

- Force Field: Assign parameters using a modern biomolecular force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER).

2. Simulation Execution:

- Equilibration: Run simulations to equilibrate the temperature and pressure of the system.

- Production Run: Perform multiple long-timescale trajectories using software like GROMACS, NAMD, or OpenMM. The ligand's position relative to the pocket (reaction coordinate, e.g.,

zin Figure 1 of [11]) and water coordinates are recorded over time.

3. Data Analysis:

- Mean First Passage Time (mfpt): Calculate the mfpt distribution for ligand binding from the trajectories, which describes the time scale for the ligand to reach the binding site from a given distance [11].

- Potential of Mean Force (PMF): Compute the free energy landscape (PMF) along the reaction coordinate using methods like umbrella sampling or metadynamics.

- Local Diffusivity Profile D(z): Derive the position-dependent diffusivity from the mfpt distribution under the Markovian assumption using the relationship from [11]: [ D(z) = - \frac{1}{\frac{d}{dz} mfpt(z)} \exp\left(-\beta G(z)\right) \int{z}^{zt} \exp\left(\beta G(z')\right) dz' ]

- Hydration Analysis: Monitor the number of water molecules and the hydrogen-bonding structure within the hydrophobic pocket over time to characterize "wet/dry" fluctuations [11].

Probing the Crossover via Hydration Free Energy Measurement

The crossover can be investigated by measuring the hydration free energy for a series of homologous solutes of increasing size.

1. Solute Series Selection: Select a homologous series of non-polar or sparingly polar solutes (e.g., noble gases, linear alkanes, fullerenes).

2. Experimental Determination:

- Solubility Measurements: The standard hydration free energy can be determined from the solute's solubility in water versus in a vapor or non-polar phase, using the thermodynamic relationship

ΔG_hyd = -RT ln(x_water / x_reference). - Calorimetry: Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) can be used to measure the enthalpy change (ΔH) upon solute dissolution or upon hydrophobic aggregation. Combined with the ΔG from solubility, the entropy term (TΔS) can be derived.

3. Data Fitting and Crossover Identification:

- Plot the measured

ΔG_hydagainst the solute's volume and surface area. - Perform linear fits; the point where the surface-area scaling provides a better fit than the volume-scaling identifies the crossover region, which is expected to be around the nanometer scale [10].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Conceptual Framework of Size-Dependent Hydration

Workflow for MD Simulation of Binding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Hydrophobic Interaction Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose in Research |

|---|---|

| Explicit Water Models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P) | Computational models used in MD simulations to represent water molecules with atomistic detail, crucial for capturing hydrophobic and solvation effects accurately [11]. |

| Biomolecular Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS) | Sets of empirical parameters defining potential energy functions for atoms in a molecular system, enabling realistic MD simulations of proteins, ligands, and their aqueous environment [11]. |

| Hydrophobic Cavity Model Systems | Simplified, well-defined molecular systems (e.g., engineered hydrophobic pockets, host-guest systems like cyclophane-benzene) used to study hydrophobic binding fundamentals without the complexity of a full protein [11] [10]. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | An experimental technique used to directly measure the heat change (enthalpy, ΔH) associated with a binding event, providing full thermodynamic profiling (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS) of hydrophobic interactions [10]. |

| Homologous Non-Polar Solute Series | A series of related molecules of increasing size (e.g., alkanes, fullerenes) used to experimentally probe the scaling of hydration free energy and identify the crossover from volume to surface-area dependence [10]. |

| Platycoside A | Platycoside A, CAS:209404-00-2, MF:C58H94O29, MW:1255.3 g/mol |

| 2,3-Didehydrosomnifericin | 2,3-Didehydrosomnifericin, CAS:173614-88-5, MF:C28H40O7, MW:488.6 g/mol |

Water, the active matrix of life, is far more than a passive spectator in biological processes. It is an integral, active component that governs the structure, dynamics, and function of biomolecular systems. This whitepaper explores the complex hydrogen-bonding networks of water at biological interfaces and their decisive role in biomolecular recognition. By integrating recent advances in experimental probing and computational design, we elucidate how the structured hydration layers surrounding biomolecules directly influence binding affinity, specificity, and stability. The insights presented herein provide a foundational framework for advancing drug discovery, biomaterials engineering, and our fundamental understanding of solvent accessibility in molecular interactions.

Water is the most abundant substance in living organisms, constituting 65–90% of their mass [22]. Its central role in all vital processes has been recognized for over a century, yet its active participation in biological function continues to reveal new complexities. Water is a polar, protic solvent and amphoteric reagent with the ability to ionize both itself and other molecules [22]. The hydrogen bond, with a bond dissociation energy of 21 kJmolâ»Â¹ compared to 464 kJmolâ»Â¹ for covalent bonds, creates a dynamic, continuously breaking and re-forming network that is fundamental to life's processes [22].

The concept of "biological water" has gained prominence in recent literature, referring to water surrounding biomolecules whose properties differ considerably from those of bulk water [22]. This interfacial water forms an active layer that mediates interactions between molecules, participates in chemical reactions, and stabilizes three-dimensional structures. Understanding this interfacial water is particularly crucial for rational drug design, where binding affinity and specificity are often determined by the energetics of water displacement and rearrangement.

The Molecular Architecture of Interfacial Water

Hydrogen Bonding Networks in Aqueous Environments

The hydrogen-bonding network of water provides the underlying framework for its unique physicochemical properties. In liquid water, hydrogen bonds have a lifespan ranging from tens of femtoseconds to picoseconds, creating a continuously dynamic yet structured matrix [22]. This network is not random; it exhibits a tetrahedral coordination that gives water its anomalous properties, including decreased viscosity under pressure, maximum density at 4°C, and unusually high boiling point for such a small molecule [22].

When water interacts with interfaces, particularly biological macromolecules, this network reorganizes in response to chemical and topological features. The strength of water interactions follows a hierarchy: water-ion > water-water = water-polar group > water-hydrophobic group [22]. This hierarchy dictates how water molecules arrange themselves around different chemical moieties, creating distinct hydration environments that influence biomolecular conformation and interaction.

The Three-State Model of Water in Confined Environments

In hydrated polymer systems such as hydrogels—which closely simulate natural biological environments—water exists in three distinct states according to the well-established three-state model [22]:

Table 1: The Three-State Model of Water in Hydrated Biomolecular Systems

| Water State | Location | Hydrogen Bonding Characteristics | Thermodynamic Behavior | Dynamic Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bound Water | Primary hydration shell around hydrophilic polymer chains | Directly hydrogen-bonded to polar groups | Does not show freezing/melting behavior | Restricted mobility, longer residence times |

| Intermediate Water | Secondary hydration shell | Hydrogen-bonded to bound water and other water molecules | Shows altered phase transition behavior | Moderate mobility, dynamic exchange |

| Free Water | Bulk-like water at greater distances from interface | Fully developed hydrogen-bonding network | Normal freezing/melting behavior | High mobility, similar to bulk water |

This model has profound implications for understanding how water structure influences biomolecular recognition. The bound and intermediate water molecules create a hydration shell that must be partially disrupted for molecular binding to occur, with significant energetic consequences for binding affinity.

Probing Interfacial Water Structure in Living Systems

Experimental Challenges and Advanced Methodologies

Despite its fundamental importance, the structure of intracellular water has remained elusive due to experimental difficulties in probing water's hydrogen-bonding network in living cells [23]. Traditional techniques like vibrational sum frequency generation (SFG) require extended planar interfaces incompatible with intracellular environments, while infrared absorption and Raman scattering probe volume properties without inherent interface selectivity [23].

Recent advances in Raman micro-spectroscopy have overcome these limitations, enabling researchers to uncover the composition, abundance, and vibrational spectra of intracellular water in individual living cells [23]. This approach combines confocal Raman microscopy with multivariate curve resolution (MCR) spectroscopy to distinguish bulk-like water from structurally altered "biointerfacial water" in the vicinity of biomolecules.

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Probing Interfacial Water Structure

| Technique | Principle | Spatial Resolution | Interface Sensitivity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Micro-spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering of light measuring molecular vibrations | ~2 μm × 2 μm × 10 μm | Moderate (enhanced with MCR) | Intracellular water structure in living cells |

| Chiral SFG | Second-order nonlinear optical process leveraging chirality transfer | N/A (ensemble measurement) | High (intrinsic interface selectivity) | Interfacial water at biomolecular surfaces |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Heat flow measurements during phase transitions | N/A (bulk measurement) | Indirect (through freezing behavior) | Quantifying freezable vs. non-freezable water |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Magnetic properties of atomic nuclei | N/A (ensemble measurement) | Moderate (through relaxation times) | Water dynamics and mobility |

Experimental Protocol: Whole-Cell Raman Spectroscopy of Intracellular Water

Methodology for Probing Intracellular Water Structure in Living Cells [23]

Cell Preparation: Culture mammalian cells (e.g., HeLa cells) under standard physiological conditions. Maintain cells in appropriate growth medium with necessary supplements.

Instrument Configuration: Utilize a home-built whole-cell confocal Raman microscope with the following specifications:

- Objective: 20× with effective numerical aperture (N.A.) ~0.4

- Laser Configuration: Intentional under-filling of the back aperture

- Confocal Pinhole: 40 μm diameter

- Optimal Confocal Volume: ~2 μm × 2 μm × 10 μm

Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire Raman spectra (I_live cell OH region) from multiple individual living cells

- Collect reference spectrum from pure bulk water (I_bulk water) under identical conditions

- Focus specifically on the high-wavenumber region (3100-3800 cmâ»Â¹) corresponding to O-H stretching vibrations

- Ensure acquisition parameters avoid photodamage or photo-driven processes (verify via time series)

Solute Background Quantification:

- Dehydrate intact cells under vacuum in an isothermal manner

- Acquire whole-cell Raman spectrum after thorough dehydration (I_vacuum dehydrated cell)

- Use the amide I band as a proximity sensor to validate minimal spectral shifts in N-H vibrations

Spectral Analysis:

- Employ Raman multivariate curve resolution (MCR) spectroscopy to deconvolute overlapping spectral features

- Separate contributions from bulk-like water and biointerfacial water

- Quantify relative abundances and characteristic vibrational spectra of each component

Experimental Workflow for Intracellular Water Analysis

Key Findings on Intracellular Water Structure

Application of the above methodology has revealed critical insights into intracellular water organization [23]:

Consistent Non-Bulk Population: Across multiple cell types, approximately 3% of intracellular water exists in a non-bulk-like state with a weakened hydrogen-bonded network and more disordered tetrahedral structure.

Biointerfacial Water Layer: Whole-cell modeling suggests all soluble (globular) proteins inside cells are surrounded by, on average, one full molecular layer (approximately 2.6 Ã…) of this biointerfacial water.

Spectral Invariance: Remarkable consistency in biointerfacial water characteristics is observed among different single cells and distinct cell types, suggesting this may underlie thermodynamic stability of the proteome.

The Role of Interfacial Water in Biomolecular Recognition

Water as a Mediator of Binding Affinity and Specificity

Interfacial water molecules play decisive roles in biomolecular recognition processes, including antigen-antibody complexation, protein-ligand binding, and enzyme-substrate interactions [24]. Water mediates these interactions through several mechanisms:

Structural Waters: Individual water molecules can form integral structural components of binding interfaces, creating bridging hydrogen bonds that stabilize complexes. In antigen-antibody interactions, for instance, interfacial water molecules facilitate complexation through extended hydrogen-bonding networks [24].

Energetic Determinants: The thermodynamics of binding are heavily influenced by water reorganization. Displacement of unfavorable hydration from hydrophobic surfaces provides significant driving force (hydrophobic effect), while retention of specific water molecules in binding pockets can enhance specificity through additional hydrogen-bonding interactions.

Allosteric Regulation: Water molecules can transmit allosteric signals through hydrogen-bonding networks, enabling communication between distant sites on proteins and influencing binding affinity at remote locations.

Computational Design of Biomolecular Systems with Enhanced Stability

Recent advances in computational protein design leverage our understanding of hydrogen-bonding networks to create biomolecules with exceptional stability. By maximizing hydrogen-bond networks within force-bearing β strands, researchers have designed proteins exhibiting unfolding forces exceeding 1,000 pN—approximately 400% stronger than natural titin immunoglobulin domains [25].

These computationally designed proteins retain structural integrity after exposure to 150°C, demonstrating how optimized hydrogen-bonding networks can confer extreme stability [25]. When incorporated into hydrogels, these designed proteins translate molecular-level stability directly to macroscopic material properties, creating thermally stable biomaterials [25].

Water-Mediated Biomolecular Recognition Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Interfacial Water

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Microscope System | Confocal configuration, 20× objective (N.A. ~0.4), 40 μm pinhole | Non-destructive probing of intracellular water structure in living cells | Requires tight confocality to eliminate autofluorescence and substrate scattering |

| Cell Culture Lines | HeLa cells or other mammalian cell lines | Model systems for intracellular water studies | Must maintain physiological conditions during measurement |

| Vacuum Dehydration System | Isothermal dehydration chamber | Removal of water for solute background quantification | Must ensure complete dehydration without structural degradation |

| Reference Proteins | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or other model proteins | Validation of solute spectral contributions | Enables quantification of N-H group contributions |

| Dâ‚‚O Buffer Systems | High-purity deuterium oxide | Hydrogen-deuterium exchange studies | Allows separation of O-H and N-H vibrational contributions |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, CHARMM, or other packages | Simulation of water dynamics and hydrogen-bonding networks | Requires force fields parameterized for biological water (e.g., CHARMM36m) |

| Hydrogel Formulations | Natural (collagen, alginate) or synthetic (PEG, PVA) polymers | Model systems for studying water states in hydrated biomaterials | Enable correlation of water organization with material properties |

| Nemoralisin C | Nemoralisin C, MF:C20H28O5, MW:348.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Kanshone H | Kanshone H, MF:C15H20O, MW:216.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

Leveraging Water Structure in Rational Drug Design

The understanding of interfacial water structure has profound implications for drug discovery, particularly in predicting and optimizing drug-target interactions (DTI) and binding affinity (DTA) [26]. Computational approaches that explicitly account for water molecules in binding sites have demonstrated improved accuracy in predicting binding affinities and specificities.

Structure-Based Drug Design: Modern computational methods can identify conserved water molecules in protein binding sites that should be retained as part of the binding interface, as well as unfavorable hydration sites where ligands should be designed to displace water molecules for maximal binding affinity [27].

Solvent Accessibility and Hydrophobic Effects: Mapping solvent accessibility and characterizing hydrophobic surfaces enables optimization of the hydrophobic effect—a major driver of binding affinity. Understanding how water reorganizes around hydrophobic patches informs the design of ligands with improved binding characteristics.

Emerging Computational Approaches

Deep learning models have emerged as powerful tools for DTI/DTA prediction, leveraging large-scale datasets and complex computational models to accurately predict interactions between drugs and their targets [26]. These approaches include:

- Structure-based methods that explicitly model atomic-level interactions including bridging water molecules

- Sequence-based methods that infer binding propensity from primary sequences

- Hybrid approaches that integrate multiple data types including structural information, physicochemical properties, and known interaction networks

Table 4: Computational Methods for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction Incorporating Solvent Effects

| Method Category | Key Features | Treatment of Solvent Effects | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based | Molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations | Explicit or implicit water models, hydration site analysis | Binding pose prediction, affinity optimization |

| Sequence-Based | Protein and ligand sequence analysis, deep learning | Implicit treatment through physicochemical features | Initial screening, target identification |

| Graph Neural Networks | Molecular graph representation of drugs and proteins | Node features encoding solvation properties | Polypharmacology prediction, drug repositioning |