Structure-Based Design of Peptide Mimetics: Bridging AI, Chemistry, and Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge computational and AI-driven methodologies revolutionizing the structure-based design of peptide mimetics.

Structure-Based Design of Peptide Mimetics: Bridging AI, Chemistry, and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge computational and AI-driven methodologies revolutionizing the structure-based design of peptide mimetics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of mimicking endogenous peptides, details advanced techniques from equivariant diffusion models to transformer networks, and addresses key challenges in optimization and stability. Further, it critically examines the validation frameworks and comparative advantages of these novel therapeutics over conventional biologics, synthesizing the current landscape and future trajectory of this rapidly evolving field aimed at modulating challenging protein-protein interactions.

The Rationale for Peptide Mimetics: Overcoming Nature's Limits with Designed Molecules

Therapeutic peptides occupy a unique and growing niche in the pharmaceutical landscape, bridging the gap between small molecule drugs and large biologics. They are typically composed of well-ordered amino acid sequences with molecular weights ranging from 500 to 5000 Da [1]. Their primary advantage lies in their exceptional target specificity and potency, enabling them to modulate complex biological targets like protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that are often "undruggable" by conventional small molecules [2] [3]. Peptides can engage with large protein surfaces (1500–3000 Ų), a feat difficult for small molecules that cover only 300–1000 Ų [2]. This results in potent therapeutic effects with minimal off-target activity and a favorable safety profile, as their metabolites are natural amino acids with low risk of toxic accumulation [1] [4].

However, these benefits are counterbalanced by significant pharmacokinetic challenges that hinder clinical development. Peptides suffer from poor membrane permeability, limiting their targets largely to extracellular receptors [2] [3]. Furthermore, they exhibit inherent chemical and physical instability, with natural amide bonds prone to enzymatic degradation, leading to short plasma half-lives and rapid elimination [2] [4]. Consequently, oral bioavailability is typically less than 1%, necessitating parenteral administration (e.g., subcutaneous injection) which reduces patient compliance for chronic conditions [5] [2]. This document details the application of structure-based design and experimental protocols to overcome these limitations through advanced peptidomimetic strategies.

Structural Modification Strategies to Enhance Peptide Stability

The structure-based classification of peptidomimetics provides a systematic framework for designing therapeutics with improved stability. This classification, ranging from Class A (most similar to the native peptide) to Class D (least similar), guides the degree of abstraction from the natural precursor [6].

Table 1: Classification of Peptidomimetics for Stability Enhancement

| Class | Description | Key Strategies | Impact on Stability/Permeability | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A | Peptides with minimal modified amino acids to stabilize bioactive conformation. | Side-chain modulation, N- and C-terminal capping (e.g., acetylation, amidation). | Moderate improvement in enzymatic stability; minimal effect on permeability. | Stabilized analogues of native hormones (e.g., Oxytocin, Desmopressin). |

| Class B | Peptides with major backbone alterations and non-natural amino acids. | Incorporation of D-amino acids, peptoids, β-amino acids, and foldamers. | Significant resistance to proteolysis; variable effect on membrane penetration. | Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), GLP-1 analogue Liraglutide (fatty acid chain). |

| Class C | Small-molecule scaffolds that project key pharmacophores from the parent peptide. | De novo design of synthetic scaffolds (e.g., benzodiazepines, terphenyl). | High metabolic stability and potential for oral bioavailability; challenging design. | Inhibitors of PPIs (e.g., Bcl-2, MDM2/p53). |

| Class D | Molecules mimicking peptide mode of action without direct structural link. | Fragment-based screening, virtual library screening, affinity optimization. | Drug-like pharmacokinetic properties; no peptide-like degradation. | Identified via high-throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries. |

Protocol: Stabilizing Peptides via Backbone Cyclization

Cyclization is a highly effective Class B strategy to rigidify peptide structure, reducing conformational flexibility and shielding backbone amide bonds from proteases [4].

Materials:

- Resin: Rink Amide MBHA or Wang resin (for C-terminal acid).

- Coupling Reagents: HATU, HBTU, or DIC/Oxyma Pure.

- Orthogonal Protecting Groups: Fmoc-Lys(Dde)-OH, Fmoc-Asp(OAll)-OH, Fmoc-Glu(OAll)-OH.

- Cleavage Reagents: Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), Triisopropylsilane (TIS), Water.

- Cyclization Reagents: PyBOP or HATU with DIPEA in dilute DMF.

Method:

- Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS): Perform standard Fmoc-SPPS to assemble the linear sequence on the resin.

- Selective Deprotection:

- For head-to-tail cyclization (amide bond between N- and C-termini), use a mild acid to deprotect the C-terminal carboxylic acid if an allyl ester is employed.

- For side-chain-to-side-chain cyclization (e.g., lactam bridge), selectively deprotect the side chains of a lysine (Dde group removable with 2% hydrazine) and an aspartic/glutamic acid (OAll group removable with Pd(PPh₃)₄).

- On-Resin Cyclization: After deprotection, treat the resin-bound peptide with PyBOP (4 eq) and DIPEA (8 eq) in DMF for 2-4 hours. Use a high dilution (0.5-1 mM peptide concentration) to minimize dimerization.

- Cleavage and Global Deprotection: Cleave the cyclized peptide from the resin using a standard TFA cocktail (e.g., TFA/TIS/water, 95:2.5:2.5) for 2-3 hours.

- Purification and Characterization: Precipitate the crude peptide in cold diethyl ether, then purify via reverse-phase HPLC (C18 column, water/acetonitrile gradient with 0.1% TFA). Verify the product using LC-MS and analytical HPLC.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Peptide Mimetics

Protocol: Assessing In Vitro Metabolic Stability in Plasma

This protocol determines the half-life of a peptide candidate in biological media, a critical parameter for lead optimization.

Materials:

- Test Compound: Purified peptide or peptidomimetic (1 mg/mL stock in DMSO or buffer).

- Plasma: Mouse, rat, or human heparinized plasma (commercially sourced).

- Precipitation Solvents: Acetonitrile (ACN), Trichloroacetic acid (TCA).

- Equipment: Thermostatted water bath or incubator (37°C), microcentrifuge, LC-MS system.

Method:

- Incubation Preparation: Pre-warm plasma to 37°C. Prepare a 100 µM working solution of the test compound in pre-warmed plasma (final DMSO concentration <1%).

- Time-Course Sampling: Immediately after spiking (t=0), withdraw a 50 µL aliquot and transfer to a microcentrifuge tube containing 100 µL of ice-cold ACN (or 20% TCA) to precipitate proteins.

- Repeat sampling at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes).

- Sample Processing: Vortex each sample thoroughly and incubate on ice for 10 minutes. Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet precipitated proteins.

- Analysis: Transfer the clear supernatant to a new vial and analyze by LC-MS. Quantify the remaining intact peptide by integrating the peak area in the extracted ion chromatogram.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of the remaining peptide percentage versus time. The slope of the linear regression (k) is used to calculate the half-life: tâ‚/â‚‚ = ln(2)/k.

Protocol: Measuring Permeability in Caco-2 Cell Monolayers

The Caco-2 assay models intestinal absorption and is a standard for predicting oral bioavailability.

Materials:

- Cell Line: Caco-2 cells (human colon adenocarcinoma).

- Culture Media: DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin.

- Transwell Inserts: 12-well or 24-well plates with polycarbonate membranes (0.4 µm pore size).

- Transport Buffer: HBSS with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

- Test Compound: 100 µM in transport buffer.

- Integrity Marker: Lucifer Yellow (1 mg/mL).

- Equipment: Cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂), plate reader or LC-MS.

Method:

- Cell Culture and Seeding: Maintain Caco-2 cells in culture media. Seed onto Transwell inserts at a density of 1 × 10ⵠcells/cm². Change media every 2-3 days and allow cells to differentiate for 21-28 days until transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) exceeds 500 Ω·cm².

- Experiment Pre-treatment: On the day of the experiment, wash monolayers twice with pre-warmed transport buffer. Measure TEER to confirm monolayer integrity.

- Bidirectional Transport Assay:

- Apical-to-Basolateral (A-B): Add test compound to the apical (donor) chamber. Sample from the basolateral (receiver) chamber at intervals (e.g., 30, 60, 90, 120 min). Replace with fresh buffer.

- Basolateral-to-Apical (B-A): Add test compound to the basolateral chamber and sample from the apical chamber.

- Include Lucifer Yellow to check for paracellular leakage.

- Sample Analysis: Quantify the concentration of the test compound in all samples using LC-MS.

- Data Calculation:

- Apparent Permeability (Papp) is calculated as: Papp = (dQ/dt) / (A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the membrane area, and C₀ is the initial donor concentration.

- Efflux Ratio (ER) is calculated as: ER = Papp (B-A) / Papp (A-B). An ER > 2 suggests active efflux.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Peptide Mimetic Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids | Building blocks for solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). | Include non-natural amino acids (e.g., D-amino acids, N-methylated) for Class A/B mimetics. |

| Rink Amide MBHA Resin | Solid support for SPPS; yields C-terminal amide upon cleavage. | C-terminal amidation can enhance metabolic stability. |

| Orthogonal Protecting Groups (Dde, OAll) | Enables selective deprotection for on-resin cyclization. | Critical for introducing lactam bridges or other macrocyclizations. |

| Coupling Reagents (HATU, PyBOP) | Activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation during SPPS. | HATU/PyBOP are efficient for coupling sterically hindered residues. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro model of human intestinal permeability. | Requires 21-28 day culture to form fully differentiated monolayers. TEER measurement is essential. |

| Heparinized Plasma (Human/Rat) | Matrix for in vitro metabolic stability studies. | Species selection should align with planned preclinical in vivo studies. |

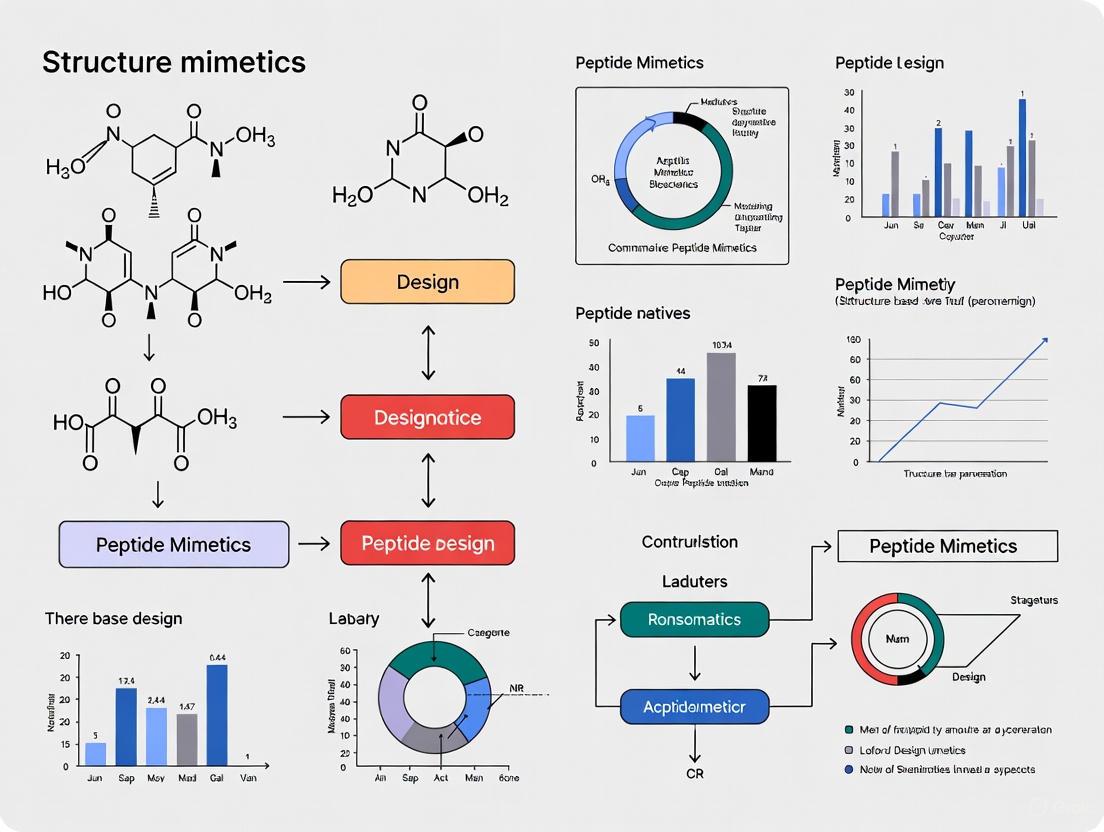

Visualization of Peptide Mimetic Design and Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for tackling the peptide dilemma and the structural evolution of peptidomimetics.

Diagram 1: Peptide Optimization Workflow. This flowchart outlines the iterative process of designing and optimizing peptide therapeutics, highlighting the feedback loops for re-design based on pharmacokinetic data.

Diagram 2: Peptidomimetic Design Pathways. This diagram shows the transition from a native peptide with poor pharmacokinetics (PK) to optimized mimetics via distinct structural design pathways (Classes A-D), ultimately achieving a balance of specificity and PK.

The therapeutic peptide dilemma is being systematically addressed through structure-based design strategies that move beyond simple peptide sequences toward advanced peptidomimetics (Classes A-D). By applying rigorous experimental protocols for synthesis, stabilization, and pharmacokinetic evaluation, researchers can transform highly specific but vulnerable peptide leads into robust drug candidates. The integration of computational tools, green synthesis principles, and sophisticated delivery platforms continues to expand the potential of peptide-based therapeutics to target previously intractable diseases, promising a new era of precision medicine.

Peptidomimetics represent a transformative approach in medicinal chemistry and drug development, designed to overcome the inherent limitations of native therapeutic peptides. These sophisticated molecules retain the biologically active conformation of peptides while incorporating strategic modifications to enhance metabolic stability, membrane permeability, and binding affinity. This application note explores the fundamental principles of peptidomimetic design, from stable secondary structure scaffolds to fully synthetic backbones, providing detailed experimental protocols for their development and analysis. Within the broader context of structure-based design of peptide mimetics research, we demonstrate how rational engineering approaches are yielding novel therapeutic candidates with improved drug-like properties across multiple disease areas, including metabolic disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases.

Therapeutic peptides occupy a crucial niche between small molecules and biologics, offering high specificity and affinity for challenging targets like protein-protein interactions [2]. However, their development as drugs faces significant hurdles, including poor metabolic stability, rapid clearance, and limited membrane permeability [2] [5]. Nearly 90% of peptide drugs in clinical development target extracellular receptors due to their inability to efficiently cross cell membranes [2]. Additionally, natural peptides typically exhibit half-lives of only minutes in circulation due to enzymatic degradation [5] [7].

Peptidomimetics address these limitations through strategic structural modifications that enhance stability while maintaining biological activity. The term encompasses a spectrum of designs, from minimally modified peptides with non-natural amino acids to fully synthetic scaffolds that mimic peptide topology without retaining natural backbone chemistry. This evolution from natural peptides to peptidomimetics has enabled the development of groundbreaking therapeutics, including GLP-1 receptor agonists for diabetes and obesity, with worldwide peptide drug sales exceeding $70 billion [2].

Stable Scaffold Engineering: The WW Domain Case Study

Protein scaffolds provide robust frameworks for engineering novel binding functions while maintaining structural stability. The WW domain, a small protein domain of 38-40 residues with a three β-sheet structure, exemplifies this approach [8]. Its small size, efficient expression, and robust folding independent of disulfide bonds make it ideal for protein engineering applications.

WW Domain Library Design and Selection Protocol

Objective: Engineer WW domains to bind non-cognate targets through loop extension and randomization.

Materials:

- WW prototype (WWp) sequence (PDB: 1E0M) as starting scaffold

- Phage display library system

- Human serum albumin (HSA) as model target

- E. coli expression system for protein production

Methodology:

Scaffold Design:

- Base scaffold on WW prototype sequence maintaining β-sheet framework residues

- Extend loop I to 5 residues and loop II to 4 residues (creating WWp5_4 scaffold)

- Fully randomize extended loop regions while preserving structural stability

Library Construction:

- Generate DNA library encoding randomized loops using degenerate codons

- Clone library into phage display vector

- Transform E. coli for library amplification

Binder Selection:

- Perform 3-5 rounds of panning against immobilized HSA

- Apply stringent washing conditions (e.g., containing mild detergent)

- Elute bound phage and amplify for subsequent rounds

Characterization:

- Express selected variants biologically or chemically synthesize

- Determine binding affinity via surface plasmon resonance or ELISA

- Assess structural stability using circular dichroism and molecular dynamics simulations

Expected Outcomes: Identification of WW domain variants with nanomolar to micromolar affinity for HSA, maintaining thermal stability (Tm ~44°C comparable to wild-type) [8].

Table 1: WW Domain Engineering Parameters

| Parameter | Wild-Type WW Domain | Engineered WWp5_4 |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 37-40 residues | 42 residues |

| Molecular Weight | ~4.4 kDa | ~5 kDa |

| Loop I Size | Variable (up to 6 residues) | 5 residues |

| Loop II Size | Variable (3-4 residues) | 4 residues |

| Thermal Stability (Tm) | ~44°C | Comparable to wild-type |

| Production | Recombinant or chemical synthesis | Recombinant or chemical synthesis |

Rational Design: From Linear Peptides to Cyclic Peptidomimetics

Rational design approaches transform biologically active but unstable linear peptides into optimized peptidomimetics through structure-based optimization.

Hsp90/Cdc37 Interaction Inhibitor Development

Background: The Hsp90/Cdc37 complex regulates client protein kinases and represents a therapeutic target in cancers including leukemia and hepatocellular carcinoma [9].

Stepwise Protocol:

Lead Identification:

- Identify critical interaction motif from Cdc37 (KTGDEK)

- Perform computational docking to define binding mode and orientation

Peptide Conjugation:

- Conjugate lead peptide with cell-penetrating peptide (TAT) for cellular uptake

- Add fluorescent dye for localization studies

- Confirm colocalization with Hsp90 in HCC cells via fluorescence microscopy

Cyclization and Optimization:

- Develop library of pre-cyclic and cyclic derivatives based on parent linear sequence

- Synthesize using solid-phase peptide synthesis with Fmoc chemistry

- Employ macrocyclization strategies (head-to-tail, sidechain-to-sidechain)

Evaluation:

- Determine binding affinity to Hsp90 via surface plasmon resonance

- Assess bioactivity in HCC cell lines (proliferation, apoptosis assays)

- Evaluate effects on downstream signaling (MEK1/2 phosphorylation)

Results: This approach yielded a pre-cyclic peptidomimetic with high binding affinity and bioactivity, reducing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in HCC cells [9].

Computational Approaches and AI-Driven Design

Computational methods have revolutionized peptidomimetic design, enabling rapid exploration of chemical space and prediction of optimized structures.

PepINVENT: Generative AI for Peptidomimetic Design

Platform: PepINVENT extends the REINVENT framework with chemistry-aware generative capabilities for peptide design [10].

Workflow:

Data Preparation:

- Incorporate natural amino acids and 10,000 non-natural α-amino acids from virtual libraries

- Utilize CHUCKLES representation for atomic-level encoding of amino acids

- Generate semi-synthetic peptide data covering diverse topologies

Model Training:

- Train generative model to understand peptide granularity

- Enable de novo design of amino acids for masked positions within peptides

Optimization:

- Apply reinforcement learning for multi-parameter optimization

- Optimize for properties including permeability, solubility, and metabolic stability

Application: The platform successfully designs cyclic REV-binding protein analogs with enhanced permeability and solubility [10].

Comparative Modeling of Short Peptides

Objective: Evaluate computational approaches for predicting peptide structures.

Protocol:

Algorithm Selection:

- Compare AlphaFold, PEP-FOLD, Threading, and Homology Modeling

- Use 10 randomly selected peptides from human gut metagenome

Structure Analysis:

- Assess predicted structures using Ramachandran plots and VADAR

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns each)

Validation:

- Correlate with physicochemical properties and sequence characteristics

- Evaluate folding accuracy and stability over simulation time

Key Finding: AlphaFold and Threading complement each other for hydrophobic peptides, while PEP-FOLD and Homology Modeling perform better for hydrophilic peptides [11].

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for peptidomimetic design combining computational and experimental approaches.

Structural Characterization and Analytical Protocols

MS/MS Analysis of Peptidomimetics

Challenge: Commercial MS/MS analysis software is typically restricted to linear natural amino acid sequences [12].

Solution: PICKAPEP application for computational representation of diverse peptidomimetic structures.

Protocol:

Sample Preparation:

- Dissolve peptidomimetics in appropriate solvent (acetonitrile/water with 0.1% formic acid)

- Prepare concentrations of 1-10 μM for analysis

Data Acquisition:

- Perform collision-induced dissociation (CID) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD)

- Use ion trap mass spectrometer for fragmentation analysis

- Apply stepped collision energies for comprehensive fragmentation

Data Analysis:

- Implement custom algorithm for theoretical fragment calculation

- Process MS/MS data automatically against generated structures

- Validate against known fragmentation patterns (e.g., cyclosporin, semaglutide)

Outcome: Enables high-throughput evaluation and confirms literature-reported fragmentation patterns [12].

Chromatographic Purification and Analysis

Challenge: Closely related impurities in synthetic peptides exhibit subtle mass and physicochemical differences [12].

Comprehensive HPLC/FPLC Protocol:

Method Development:

- Evaluate multiple RP columns (e.g., InnoPep, ResiPure Advanced C18, SunFire C18)

- Systematically vary parameters: column temperature, gradient steepness, organic modifier

- Synthesize model peptides simulating common modifications (amide-acid variants, misincorporation, isoaspartate)

Method Transfer:

- Incorporate key parameters from analytical to preparative system

- Account for column volume and dwell volume differences

- Reduce prediction deviations from 17% to under 3%

Separation Optimization:

- Identify gradient steepness and modifier choice as most impactful factors

- Achieve >90% purity in first-pass purification for all cases

Key Finding: Both scouting columns with 10 μm particle size performed comparably to reference columns with 3 μm particles [12].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Peptidomimetic Development

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| SiliCycle SiPPS Resin | Silica-based solid-phase peptide synthesis | Reduces solvent usage and waste in SPPS |

| PepINVENT AI Platform | Generative peptide design with non-natural amino acids | De novo design of permeable cyclic peptides |

| PICKAPEP Software | Computational representation of modified peptides | MS/MS analysis of cyclized peptidomimetics |

| WW Domain Scaffold | Stable β-sheet framework for engineering | Phage display against non-cognate targets like HSA |

| Macrocyclic Glycopeptide-based Selectors | Enantioseparation of fluorinated amino acids | Purification of fluorinated tryptophan analogs |

Structure-Activity Relationship Studies: Ultra-Short GLP-1 Agonists

SAR studies enable systematic optimization of peptide properties through strategic modifications.

Ultra-Short GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Optimization

Background: Development of 11-mer peptides mimicking the N-terminal activity of full-length GLP-1 (39 amino acids) [7].

Comprehensive SAR Protocol:

Template Identification:

- Start with benchmark sequence: H-His-Aib-Glu-Gly-Thr-Phe-Thr-Ser-Asp-Bip-Bip-NHâ‚‚

- Focus on Aib² and Bip¹â°-Bip¹¹ modifications

Systematic Scanning:

- Perform Ala- and Aib-scanning throughout 11-mer template

- Differentiate side chain vs. backbone conformational contributions

Position 6 Optimization:

- Evaluate Pheⶠmodifications including fluorination and α-methylation

- Test diverse amino acids (Hph, Bip, Tyr, Trp, D-Phe)

QSAR Modeling:

- Correlate structural modifications with GLP-1R agonist potency

- Use YASARA Structure for computational modeling

- Map interactions with recent GLP-1R co-structures

Key Results:

- α-Me-Phe(2-F)ⶠmodification significantly enhanced potency

- Aib² provided structural bias and DPP-4 proteolysis resistance

- Achieved 1000-fold potency optimization from initial template [7]

Diagram 2: Strategic approaches to overcoming GLP-1 therapeutic limitations through peptidomimetic design.

Peptidomimetics represent the frontier of peptide-based therapeutic development, addressing fundamental limitations of natural peptides while maintaining their favorable specificity and affinity characteristics. The integrated approaches described herein—from stable scaffold engineering and rational design to AI-driven computational methods—provide robust frameworks for advancing peptidomimetic candidates. As demonstrated through the case studies, successful peptidomimetic development requires interdisciplinary strategies combining structural biology, computational modeling, synthetic chemistry, and comprehensive analytical characterization. The continued evolution of these methodologies promises to expand the druggable landscape, enabling targeting of challenging protein-protein interactions and intracellular targets previously considered undruggable. Within the broader context of structure-based design of peptide mimetics research, these advances highlight the transformative potential of peptidomimetics in shaping the next generation of therapeutics.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) govern nearly all biological processes, including cellular signaling. A significant proportion of these interactions are mediated by a small cluster of key residues within three main recognition motifs: the α-helix, β-turn, and β-strand [13] [14]. While these interfaces present challenges for traditional small molecule drugs due to their relatively large surface areas, they offer compelling targets for therapeutic intervention. Peptide mimetics have emerged as a powerful approach to modulate these interactions by reproducing the essential structural features of these motifs without the limitations of native peptides, such as poor metabolic stability and membrane impermeability [2] [15]. This application note details the design principles, synthesis, and validation protocols for mimetics targeting α-helices and β-turns, key secondary structures that serve as hubs for PPIs [16].

α-Helix Mimetics

Design Principles and Scaffold Optimization

The α-helix is the most prevalent protein secondary structure, with analysis of the Protein Data Bank indicating that interacting helices are typically 8-12 residues long [16]. In many PPIs, the key binding residues lie along one face of the helix. The primary design goal is to create a scaffold that projects side-chain functionality to mimic the i, i+4, and i+7 residues of the natural α-helix [14].

Initial designs based on a triaryl amide scaffold were refined through iterative synthesis and evaluation against the MDM2/p53 interaction, a prototypical α-helix-mediated PPI [14]. The optimized scaffold maintains the spatial orientation of critical hydrophobic residues (Phe19, Trp23, Leu26) from p53 while improving synthetic accessibility and aqueous solubility compared to earlier terphenyl designs.

Library Synthesis Protocol

Title: Solution-Phase Synthesis of an α-Helix Mimetic Library

Objective: To prepare an 8,000-compound α-helix mimetic library representing all permutations of 20 natural amino acid side chains at the i, i+4, and i+7 positions using a solution-phase synthetic protocol.

Materials:

- Boc-protected amino acids

- 3-fluoro-4-nitrobenzoate derivatives for side chain incorporation

- Coupling reagents (HATU, HBTU, or DCC)

- Solvents: DMF, DCM, MeOH, EtOAc, hexanes

- Extraction solutions: 1M HCl, 1M NaOH, saturated NaHCO~3~, brine

- Silica gel for chromatography

Procedure:

- Diversification of Aryl Nitro Subunits: Perform nucleophilic aromatic substitution of 3-fluoro-4-nitrobenzoates with 20 different alcohols representing amino acid side chains.

- Reduction of Nitro Group: Reduce the nitro group to an aniline using SnCl~2~ or catalytic hydrogenation.

- Dimer Formation: Couple the aniline with carboxylic acid-containing subunits using standard amide coupling conditions.

- Second Diversification: Introduce the R~2~ diversity element via nucleophilic aromatic substitution on the second 3-fluoro-4-nitrobenzoate moiety.

- Final Trimer Assembly: Conduct the final coupling with a full mixture of 20 natural amino acids to generate 400 mixtures of 20 compounds (20 × 20 × 20-mix).

- Purification: Employ acid/base liquid-liquid extractions between each step to achieve >95% purity irrespective of reaction efficiency.

- Deprotection: Remove Boc and tert-butyl ester protecting groups with TFA to yield final library compounds.

Validation: The library was validated by screening against MDM2/p53, successfully identifying the lead α-helix mimetic used in its design and providing structure-activity relationship insights [14].

Constrained Peptide Helices

As an alternative to small molecule scaffolds, side chain crosslinking can stabilize short peptides in helical conformations. Several covalent constraints have been developed:

- Lactam Bridging: Forms an amide bridge between Lys/Asp or Glu/Orn residues at i and i+4 or i and i+7 positions. Optimal stabilization occurs with linkers 50-60% of the full pitch distance [16].

- Disulfide Crosslinking: Forms reversible bridges between cysteine residues, though limited by reduction in the cytosol [16].

- Thioether Crosslinking: Creates stable bridges via reaction between cysteine thiols and bromoacetamide-modified side chains [16].

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing α-helix mimetics, showing parallel strategies for small molecule scaffolds and constrained peptides.

β-Turn Mimetics

Rational Design and Geometric Considerations

β-Turns represent sites where polypeptide strands reverse direction and consist of four amino acid residues (i to i+3) [13]. Analysis of 10,245 β-turns in the Protein Data Bank revealed that trans-pyrrolidine-3,4-dicarboxamide serves as an optimal scaffold that closely matches the triangle geometries of Cα triplets found in natural β-turns [13].

Key design features:

- C~2~ Symmetry: Simplifies library synthesis by reducing the number of compounds needed to represent all side chain permutations

- Flexibility: Maintains a degree of conformational flexibility to accommodate variable H-bond donor/acceptor patterns

- Synthetic Accessibility: Amenable to solution-phase synthesis with amide coupling chemistry

Library Synthesis Protocol

Title: Synthesis of a 4,200-Member β-Turn Mimetic Library

Objective: To prepare a comprehensive β-turn mimetic library using trans-pyrrolidine-3,4-dicarboxamide template to mimic all possible permutations of 3 of the 4 residues in naturally occurring β-turns.

Materials:

- Trans-pyrrolidine-3,4-dicarboxylic acid core template

- Fmoc-protected amino acids (20 natural)

- Coupling reagents (HATU, HOAt)

- Base: DIPEA

- Solvents: DMF, DCM, MeOH

- Extraction solutions: 1M HCl, 1M NaOH, brine

- Resins for liquid-solid extraction (optional)

Procedure:

- Template Preparation: Synthesize or obtain enantiomerically pure trans-pyrrolidine-3,4-dicarboxylic acid.

- First Amide Coupling: Couple the template with a mixture of 20 Fmoc-amino acids using HATU/HOAt and DIPEA in DMF.

- Fmoc Deprotection: Treat with 20% piperidine in DMF to remove Fmoc protecting groups.

- Second Amide Coupling: Couple with a second mixture of 20 amino acids.

- Library Formatting: Assemble as 210 mixtures of 20 compounds, exploiting C~2~ symmetry to reduce the typical 8,000-member library to 4,200 compounds.

- Purification: Employ liquid-liquid or liquid-solid extractions between steps to achieve >95% purity.

- Quality Control: Analyze random samples by LC-MS to confirm identity and purity.

Validation: The library was validated against human opioid receptors (KOR, MOR, DOR), identifying compounds with high affinities (K~i~ = 23 nM for KOR) and enhanced selectivities (>100-fold) [13]. Key insights included the role of tyrosine phenol in receptor selectivity.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Binding Affinity Assays

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Protocol

- Immobilization: Immobilize target protein on CMS chip via amine coupling.

- Running Buffer: HBS-EP (10mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, 3mM EDTA, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4).

- Kinetic Measurements: Inject mimetics at varying concentrations (0.1-100μM) at 30μL/min flow rate.

- Data Analysis: Fit sensorygrams to 1:1 Langmuir binding model to determine K~D~.

Fluorescence Polarization Competition Assay

- Reagents: Fluorescently labeled native peptide, purified target protein, test compounds.

- Procedure: Incubate constant concentrations of tracer and protein with serially diluted mimetics.

- Measurement: Read polarization after 30-minute incubation.

- Analysis: Fit data to determine IC~50~, convert to K~i~ using Cheng-Prusoff equation.

Cellular Activity Assays

Cell Permeability Assessment

- Caco-2 Model: Grow Caco-2 cells to confluence on transwell inserts.

- Transport Buffer: HBSS with 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

- Procedure: Add mimetics to donor compartment, sample receiver compartment over 2 hours.

- Analysis: Calculate P~app~ and efflux ratio.

Cytotoxicity Profiling

- Cell Lines: Use relevant cell lines (e.g., MM96L, HeLa for cancer targets).

- MTT Assay: Incubate cells with serially diluted mimetics for 72 hours.

- Measurement: Measure absorbance at 570nm after MTT addition.

- Analysis: Calculate IC~50~ values for cytotoxicity.

Quantitative Data and Research Reagents

Performance Metrics of Validated Mimetics

Table 1: Representative binding affinities of validated α-helix and β-turn mimetics

| Mimetic Type | Target | Best K~i~ (nM) | Selectivity | Cellular Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triaryl α-helix | MDM2/p53 | ~100-500 | >10-fold vs. related PPIs | Yes (with CTP) | [14] |

| Pyrrolidine β-turn | KOR | 23 | >100-fold vs. MOR/DOR | Not reported | [13] |

| Pyrrolidine β-turn | KOR | 80-390 | >10-fold vs. MOR/DOR | Not reported | [13] |

| Lactam-stapled α-helix | MDM2/p53 | ~nM range | Not reported | Yes (with CTP) | [16] |

Table 2: Research reagent solutions for peptide mimetics research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Scaffolds | Triaryl amide; trans-Pyrrolidine-3,4-dicarboxamide | Provides structural foundation for mimetics | Defined geometry, synthetic accessibility, solubility |

| Amino Acid Building Blocks | Fmoc-protected amino acids; Side-chain modified analogs | Introduces structural diversity | High purity, compatibility with synthesis protocol |

| Coupling Reagents | HATU, HOAt, HBTU, DCC | Facilitates amide bond formation | High efficiency, minimal racemization |

| Purification Materials | Silica gel; Extraction solvents (1M HCl/NaOH) | Isolates and purifies intermediates and final products | >95% purity, scalable |

| Screening Platforms | SPR chips; Fluorescent tracers | Validates binding affinity and specificity | High sensitivity, quantitative output |

The targeted mimicry of α-helices and β-turns represents a robust strategy for modulating protein-protein interactions with therapeutic potential. The structured approaches outlined herein—from rational scaffold design and library synthesis to comprehensive validation protocols—provide researchers with a roadmap for developing effective peptide mimetics. The integration of solution-phase library synthesis with rigorous biological screening enables the identification of lead compounds with optimized affinity and selectivity profiles. As structural insights into PPIs continue to grow, these methodologies will prove increasingly valuable for translating fundamental understanding of protein recognition into therapeutic interventions.

Biomimetic peptides represent a rapidly advancing frontier in both cosmetic and pharmaceutical science. These molecules are designed to mimic the structure and function of natural peptides and proteins within the skin and body, offering targeted therapeutic and restorative actions. The global biomimetic peptide market is experiencing substantial growth, projected to reach $423.8 million in 2025, with continued expansion driven by their increasing application in anti-aging skincare and targeted drug delivery systems [17].

The fundamental premise of biomimetic peptide technology lies in its structure-based design, which aims to replicate the minimal functional sites (MFS) of natural enzymes and structural proteins. This approach allows researchers to create simplified, stable, and highly effective peptide sequences that retain biological activity while offering superior stability and processability compared to their natural counterparts [18]. The market's strength stems from this unique combination of natural biological efficacy with the precision of bioengineering, positioning biomimetic peptides as transformative ingredients across multiple industries.

Table 1: Global Biomimetic Peptide Market Overview

| Market Aspect | 2025 Projection | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Total Market Value | $423.8 million [17] | Robust growth driven by cosmetics and pharmaceuticals |

| Market Concentration | Cosmetics: ~60% (est. $1.2B) [17] | Highest concentration in anti-aging skincare |

| Production Volume | ~300,000 kg annually [17] | Projected CAGR of 8% over next five years |

| Pharmaceutical Segment | Projected $500 million by 2028 [17] | Significant growth despite regulatory hurdles |

Application Notes: Cosmetics versus Pharmaceuticals

The application of biomimetic peptides diverges significantly between cosmetic and pharmaceutical contexts, each with distinct design considerations, regulatory pathways, and performance metrics.

Cosmetic Applications

In cosmetics, biomimetic peptides primarily function as bioactive signaling molecules that stimulate skin repair processes, promote collagen production, and inhibit neurotransmitter activity that leads to wrinkle formation [19] [20]. Their mechanism of action typically involves mimicking natural extracellular matrix (ECM) components or signaling peptides to trick the skin into initiating rejuvenation processes. Notable examples include Rejuline and Boostrin, established brands known for their skin rejuvenation properties, and CG-EGP3 and CG-TGP2 from Caregen, which demonstrate potential for targeted biological activity [17].

The cosmetic peptide market is substantial and growing, with the cosmetic peptide manufacturing market alone projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.3% through 2034, expected to increase from USD $3.77 billion in 2024 to USD $8.26 billion by 2032 [19]. This growth is fueled by consumer preference for natural and bio-identical ingredients and advancements in peptide stability and delivery systems that enhance topical efficacy.

Pharmaceutical Applications

In the pharmaceutical sector, biomimetic peptides are engineered for more complex therapeutic roles, including drug delivery systems, enzyme mimetics, and targeted therapeutics. Unlike cosmetic applications, pharmaceutical peptides must navigate stringent regulatory requirements and demonstrate robust efficacy in biological environments beyond the skin's surface [17] [21].

A prominent example of biomimetic design in pharmaceuticals comes from laccase enzyme mimicry, where researchers created an eight-amino acid peptide (H4pep) that self-assembles with copper ions to form a catalytically active complex capable of oxygen reduction [18]. This approach demonstrates how minimal peptide sequences can replicate essential functions of natural enzymes, offering potential for therapeutic intervention in redox-related diseases.

Table 2: Application Comparison of Biomimetic Peptides

| Parameter | Cosmetic Applications | Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Skin rejuvenation, anti-aging, moisturizing [19] | Targeted drug delivery, enzyme mimicry, therapeutics [21] |

| Key Examples | Rejuline, Boostrin, CG-EGP3, CG-TGP2 [17] | H4pep (laccase mimic), incretin mimetics, CPP-drug conjugates [18] [22] |

| Market Drivers | Consumer demand for natural ingredients, aging population [17] | Chronic disease prevalence, targeted therapy advantages [23] |

| Regulatory Hurdles | Moderate (cosmetic regulations) [17] | Stringent (pharmaceutical drug approvals) [17] [23] |

| Design Priority | Topical efficacy, stability in formulations [19] | Biological activity, metabolic stability, specificity [18] |

Structural Design Principles and Bioinformatics

The structure-based design of biomimetic peptides represents a paradigm shift from traditional discovery methods to rational, informatics-driven approaches.

Minimal Functional Site (MFS) Design

The MFS concept, developed by Andreini et al., describes the minimal three-dimensional environment that determines a metal's chemical behavior in metalloenzymes, including all residues within 5Ã… distance from any metal-binding ligand [18]. This approach forms the basis for designing minimal peptide sequences that retain the essential catalytic or binding functions of much larger protein structures. By focusing exclusively on the active site rather than the entire protein scaffold, researchers can create peptides with vastly simplified structures while maintaining biological functionality.

Bioinformatics Tools for Peptide Design

The MetalSite-Analyzer (MeSA) bioinformatics tool exemplifies the modern approach to biomimetic peptide design. This web-accessible platform (https://metalsite-analyzer.cerm.unifi.it/) enables researchers to extract relevant sequence motifs for binding metals of choice by leveraging MFS sequence alignments to identify conserved residues in metal sites belonging to protein families of interest [18]. The tool processes input PDB structures, allows selection of user-defined metal sites, extracts MFS fragments, and runs PSI-BLAST searches to analyze residue conservation across related sequences in the UniProt database.

The conservation analysis provided by MeSA highlights:

- Completely conserved residues: Presumably strictly necessary for function

- Moderately variable positions: Where one of two/three different amino acids can be selected

- Highly variable positions: Where almost any amino acid can be introduced [18]

This bioinformatics-guided approach dramatically accelerates the design process and increases the success rate of creating functional peptide mimics.

Bioinformatics Peptide Design Workflow

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bioinformatics-Driven Peptide Design

Objective: Design a minimal biomimetic peptide using the MetalSite-Analyzer (MeSA) platform [18]

Materials:

- MeSA web server (https://metalsite-analyzer.cerm.unifi.it/)

- Target protein PDB structure

- Computer with internet access

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Identify a target metalloenzyme and obtain its PDB code from the Protein Data Bank.

- MFS Extraction:

- Input the PDB code into MeSA

- Select the metal ion(s) of interest from the structure

- Run the MFS extraction algorithm to identify metal-binding fragments

- Conservation Analysis:

- Execute PSI-BLAST search on extracted fragments

- Analyze conservation patterns across protein family

- Identify strictly conserved residues (essential for function)

- Note variable positions (available for optimization)

- Peptide Sequence Design:

- Incorporate conserved residues at appropriate positions

- Select amino acids for variable positions based on structural constraints

- Aim for peptide length of 8-30 amino acids for optimal synthesis and function

- Structural Validation:

- Utilize computational tools (e.g., molecular dynamics) to predict peptide structure

- Verify metal-binding capability through in silico docking studies

Protocol 2: Synthesis and Characterization of Biomimetic Peptides

Objective: Synthesize and characterize the copper-binding peptide H4pep (HTVHYHGH) as a laccase mimic [18]

Materials:

- Protected amino acids for SPPS

- Solid support resin (e.g., Rink amide resin)

- Coupling reagents (HBTU, HOBt, DIPEA)

- Cleavage cocktail (TFA/TIS/water)

- HPLC system with C18 column

- Copper(II) chloride

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- CD (Circular Dichroism) spectrometer

- NMR spectrometer

Synthesis Procedure:

- Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis:

- Use Fmoc-chemistry strategy on Rink amide resin

- Perform sequential deprotection (20% piperidine in DMF) and coupling reactions

- Employ HBTU/HOBt/DIPEA as coupling agents in DMF

- Monitor coupling completion with Kaiser test

- Cleavage and Deprotection:

- Treat resin with cleavage cocktail (TFA:TIS:water, 95:2.5:2.5) for 3 hours

- Precipitate peptide in cold diethyl ether

- Centrifuge and dissolve in water-acetonitrile for purification

- Purification:

- Purify crude peptide by reverse-phase HPLC using C18 column

- Employ water-acetonitrile gradient with 0.1% TFA

- Analyze fractions by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

- Lyophilize pure fractions

Characterization Procedure:

- Metal Binding Studies:

- Prepare peptide solution (0.1-1.0 mM) in buffer (pH 5.6)

- Titrate with Cu(II) chloride solution (0-2 equivalents)

- Monitor by UV-Vis spectroscopy (250-800 nm)

- Record d-d transition bands (500-800 nm) indicating metal coordination

- Secondary Structure Analysis:

- Perform Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

- Measure spectra (190-260 nm) of apo- and metal-bound peptide

- Identify structural features (β-sheet, α-helix, random coil)

- Catalytic Activity Assessment:

- Test oxygen reduction capability using oxygen electrode

- Compare activity to native laccase enzyme

- Determine kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomimetic Peptide Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Synthesis | Stepwise peptide assembly on insoluble support [19] | Rink amide resin, Fmoc-protected amino acids, HBTU/HOBt coupling reagents |

| Bioinformatics Tools | In silico design and analysis of peptide sequences [18] [24] | MetalSite-Analyzer (MeSA), CPP prediction servers, molecular dynamics software |

| Characterization | Structural and functional analysis of peptides [18] | HPLC systems, CD spectrometer, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer |

| Cell-Penetrating Tags | Enhancing intracellular delivery of therapeutic peptides [24] | Tat peptide (GRKKRRQRRRPPQ), Oligoarginines (Rn, n=6-12), Penetratin |

| Stability Enhancers | Protecting against proteolytic degradation [24] | D-amino acids, cyclization, PEGylation reagents, non-natural amino acids |

| Anwuweizonic Acid | Anwuweizonic Acid, CAS:117020-59-4, MF:C30H46O3, MW:454.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Odoratisol A | Odoratisol A, CAS:891182-93-7, MF:C21H24O5, MW:356.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

AI-Driven Peptide Design

Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing biomimetic peptide design through machine learning algorithms that predict peptide behavior based on primary amino acid sequences. These tools analyze massive datasets to identify novel peptide candidates and optimize their molecular design, significantly accelerating the discovery process [24]. Supervised machine learning approaches can predict cell-penetrating capabilities, toxicity profiles, and metabolic stability without requiring extensive prior knowledge from researchers, making these tools accessible to bioscientists with limited programming experience [24].

Advanced Delivery Systems

Biomimetic peptide conjugates are increasingly being designed for controlled release applications in biomedical contexts. These systems utilize biomimetic peptides that interact with native proteins to stabilize release kinetics and maximize therapeutic benefits [21]. For instance, elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) and silk fibroin repeats can be engineered to mimic natural protein domains, modulating material properties and drug release profiles for sustained therapeutic effects [21].

Genetic Engineering Approaches

Recombinant DNA technology enables production of biomimetic peptides directly conjugated to therapeutic proteins within host cells. This approach offers advantages in precision, scalability, and functional customization compared to chemical synthesis methods [21]. Genetic engineering allows for highly specific control over peptide sequences and their linkage to target proteins, facilitating fine-tuning of structure and function for optimal biological activity [21].

Biomimetic Peptide Technology Directions

The future of biomimetic peptides lies at the intersection of these advanced technologies, enabling the development of increasingly sophisticated peptides with enhanced stability, specificity, and functionality. As AI design tools become more accessible and genetic engineering techniques more refined, researchers can expect to accelerate the development of novel biomimetic peptides for both cosmetic and pharmaceutical applications, ultimately bridging the gap between laboratory discovery and clinical implementation.

AI and Computational Arsenal for De Novo Mimetic Design

The design of small molecules that mimic the binding and function of native peptides represents a frontier in structure-based drug design. Peptides offer high affinity and specificity for their protein targets but are often hampered by poor metabolic stability and cell permeability. Converting these peptides into drug-like small molecules, or peptidomimetics, combines the advantages of both modalities [25] [26]. E(3)-equivariant diffusion models have emerged as a powerful artificial intelligence (AI) framework to address this challenge. These models learn to generate novel 3D molecular structures directly within a target protein pocket by referencing the original peptide binder, enabling the systematic and scalable design of peptide-inspired small molecules [25].

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for employing these models, framing them within a broader research thesis on the computational design of peptide mimetics.

Background and Computational Framework

The Case for Peptidomimetics in Drug Discovery

Small molecules constitute a majority of approved drugs, prized for their oral bioavailability and ease of synthesis. Peptides, in contrast, often target "undruggable" protein-protein interactions but face developmental hurdles. The success of peptidomimetics, as exemplified by drugs like Captopril, validates the therapeutic potential of translating peptide binders into small molecules [25] [26]. Traditional computational methods, which primarily rely on protein-ligand complex data, often overlook the rich structural information present in protein-peptide interactions, limiting the diversity and novelty of generated compounds [25].

E(3)-Equivariant Diffusion Models

Diffusion models are generative AI models that learn to create data by reversing a gradual noising process. In the context of molecular generation, a forward process systematically adds noise to a molecule's 3D coordinates and features until it becomes pure noise. A neural network then learns to reverse this process, iteratively denoising a random initial state to generate a novel, coherent 3D molecular structure [26] [27].

E(3)-equivariance is a critical property for 3D molecular generation. It ensures that the model's outputs (e.g., generated molecular structures) transform consistently with its inputs (e.g., the protein pocket structure) under any rotation, translation, or reflection in 3D space. This guarantees that the generated molecule is not dependent on the arbitrary orientation of the target protein in the coordinate system, a fundamental requirement for physically meaningful and reliable generation [25] [28].

Table 1: Key Components of an E(3)-Equivariant Diffusion Model for Molecular Generation

| Component | Description | Role in Peptidomimetic Design |

|---|---|---|

| Data Representation | Molecules and pockets as graphs with atomic coordinates, element types, and bond features [25]. | Captures the precise 3D spatial relationships between the peptide binder and the protein pocket. |

| Forward Diffusion Process | Progressive addition of Gaussian noise to atomic coordinates and features over a series of timesteps [25] [27]. | Systematically disrupts the reference peptide's structure to explore the chemical space around it. |

| E(3)-Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EGNN) | The denoising network that updates atomic features and coordinates using rotation-equivariant operations [25]. | Ensures generated molecules are geometrically consistent with the pocket, regardless of orientation. |

| Conditioning Mechanism | The process of feeding protein pocket and reference peptide information into the model during denoising [25] [29]. | Guides generation to produce small molecules that mimic the key interactions of the original peptide. |

| Reverse Denoising Process | The iterative prediction and removal of noise by the EGNN to generate a new 3D molecule [25]. | Produces a novel, stable small molecule candidate optimized for the target pocket. |

Protocols for Generating Peptide Mimetics

This section outlines a detailed workflow for using the Peptide2Mol model, a specific implementation of an E(3)-equivariant diffusion model designed for this task [25].

Protocol 1: Data Preparation and Featurization

Objective: To prepare and represent the protein pocket and reference peptide binder in a format suitable for the diffusion model.

Input Structure Acquisition:

- Obtain a 3D structure of the target protein complexed with the peptide of interest. Sources include the Protein Data Bank (PDB), or computationally predicted structures from the AlphaFold Database [25].

- Ensure the structure is pre-processed (e.g., add hydrogens, correct protonation states) using tools like RDKit [25].

Pocket and Ligand Definition:

Molecular Featurization:

- Represent the pocket and reference ligand as an undirected atomic graph,

M = (V, E). - Node Features (

v_i ∈ V): For each atom, define:- Spatial coordinates

r_i ∈ R^3. - Element-type feature

a_i ∈ R^8(a one-hot encoding for C, N, O, F, P, S, Cl, Br) [25].

- Spatial coordinates

- Edge Features (

e_ij ∈ E): For atom pairs, define a bond feature vectorb_ij ∈ R^6encoding bond types (single, double, triple, aromatic) and non-bonded proximity [25].

- Represent the pocket and reference ligand as an undirected atomic graph,

Protocol 2: Model Training and Conditioning

Objective: To train the diffusion model on a diverse set of complexes, enabling it to learn the mapping from peptide-protein interfaces to small molecules.

Dataset Curation:

Conditional Training:

- The model is trained to denoise a noisy ligand

M_twhile being conditioned on two key inputs: - The loss function is the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the predicted reverse distribution and the true denoising step, often optimized by having the network predict the original data

M_0[29].

- The model is trained to denoise a noisy ligand

Protocol 3: Inference and Molecular Generation

Objective: To generate novel small molecules conditioned on a target pocket and a reference peptide.

Initialization: Start with a ligand graph

M_Twhere atomic coordinates and features are sampled from a prior Gaussian distribution [25] [29].Iterative Denoising:

- For timestep

tfromTdown to 1: - This loop continues until a final, clean 3D molecular structure

M_0is generated.

- For timestep

Post-processing: The generated molecule can be further refined using tools like RDKit to check valency and ensure chemical validity. Clash resolution tools like Pocket2Mol can be applied to refine ligand-pocket complementarity [25].

The following diagram illustrates the core generative workflow implemented in these protocols.

Validation and Analysis

Protocol 4: Evaluating Generated Molecules

Objective: To computationally assess the quality, drug-likeness, and binding potential of the generated small molecules.

Structural Plausibility:

- Use RDKit to check for parsability and the presence of unusual bond lengths or angles.

- Employ the PoseBusters test suite to check for steric clashes, strain energy, and correct geometry [30].

Binding Affinity and Pose Assessment:

- Perform molecular docking (e.g., with AutoDock Vina, Gnina) to predict the binding pose and affinity of the generated molecule to the target pocket.

- Compare the docking scores and poses with those of the original reference peptide and known binders.

Chemical Property Analysis:

- Calculate key physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors).

- Evaluate compliance with drug-likeness rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [29].

Similarity to Reference:

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from Recent Model Implementations

| Model / Study | Primary Application | Reported Key Outcome | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide2Mol [25] | Peptide-to-small-molecule generation | Generates molecules with similarity to the original peptide binder; enables molecule optimization. | State-of-the-art performance on non-autoregressive generative tasks. |

| PoLiGenX [29] | Hit expansion and optimization | Generated ligands show enhanced binding affinities, lower strain energies, and fewer steric clashes than references. | Superior adherence to drug-likeness criteria (Lipinski's Rule of Five). |

| 3D-EDiffMG [31] | Lead structure optimization | Effectively generates unique, novel, stable, and diverse drug-like molecules. | Experimental results highlight potential for accelerating drug discovery. |

| Conditional EDM [30] | Improving structural plausibility | Framework generates molecules with controllable levels of structural plausibility and improved validity. | Assessed by RDKit parsability and PoseBusters test suite on QM9, GEOM, and ZINC datasets. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for E(3)-Equivariant Diffusion Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [25] | Software Library | Cheminformatics toolkit used for molecule parsing, featurization, property calculation, and similarity analysis. |

| GEOM Dataset [25] [30] | Dataset | Provides a large set of drug-like small molecules and their conformational ensembles for model training. |

| PDBBind / BioLip2 [25] | Dataset | Curated databases of protein-ligand and protein-peptide complexes with binding affinity data for training and testing. |

| AlphaFold Database [25] | Dataset | Source of computationally predicted protein structures and protein-peptide interaction models to expand training data. |

| PoseBusters [30] | Validation Tool | Test suite for checking the physical plausibility and steric compatibility of generated molecular complexes. |

| EQGAT-diff / EDM [28] [29] | Model Architecture | Core E(3)-equivariant graph neural network architectures that form the backbone of many diffusion models. |

| Sophorabioside | Sophorabioside (CAS 2945-88-2) - For Research Use Only | Sophorabioside is a bioactive flavonoid fromSophora japonicawith research value in bone health and anti-inflammatory studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Isosakuranin | Isosakuranin, CAS:491-69-0, MF:C22H24O10, MW:448.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

E(3)-equivariant diffusion models represent a transformative advancement in the structure-based design of peptide mimetics. By directly learning from structural data of protein-peptide interactions, models like Peptide2Mol provide a principled, AI-driven path for generating novel small molecules that retain the functional essence of their peptide counterparts. The protocols outlined herein offer a roadmap for researchers to implement, validate, and leverage these powerful generative tools. As these models continue to evolve, integrating more sophisticated conditioning and better physical constraints, they hold the promise of significantly accelerating the discovery of peptide-inspired therapeutics, ultimately bridging a critical gap between biologic and small-molecule drug modalities.

The rational design of compounds that mimic the structure and function of bioactive peptides is a critical endeavor in medicinal chemistry, particularly for modulating challenging targets like protein-protein interactions (PPIs) [6]. Traditional methods for converting peptide ligands into peptidomimetics often rely on incremental structural modifications guided by known structure-activity relationships. However, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) has introduced powerful new paradigms for molecular design. Among these, transformer-based chemical language models (CLMs) represent a cutting-edge approach that can directly transform input peptide sequences into diverse peptidomimetic candidates with optimized properties [32]. This application note details the integration of these models within a structure-based design framework for peptide mimetics, providing both quantitative performance data and detailed experimental protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Background and Significance

Protein-protein interactions are fundamental to cellular processes but have proven challenging to target with conventional small molecules due to their extensive and relatively flat interfaces [6]. Peptides and their mimetics offer a promising strategy by mimicking key binding epitopes from secondary structure elements such as α-helices, β-sheets, and turns [6] [33]. The structural peptidomimetics approach (Class C mimetics) involves complete replacement of the peptide backbone with a synthetic scaffold that projects side-chain functionalities in spatial orientations analogous to those in the native peptide [33]. Quantitative analysis of how well these mimetics replicate the original peptide structure is crucial; methods like the Peptide Conformation Distribution (PCD) plot and Peptidomimetic Analysis (PMA) map enable visual and quantitative evaluation by comparing Cα–Cβ bond vectors of peptide fragments with corresponding pseudo-Cα–Cβ bonds in mimetic molecules [33].

Transformer-based models have recently been applied to navigate the complex transition from peptide sequences to drug-like peptidomimetics. These models learn from molecular representation data and can directly generate peptidomimetic candidates from input peptides, gradually altering chemical features and reducing peptide character while preserving or enhancing bioactivity [32]. This capability is particularly valuable for addressing common limitations of therapeutic peptides, such as proteolytic degradation, poor pharmacokinetics, and low membrane permeability [34].

Quantitative Performance of Transformer Models

Extensive validation studies have demonstrated the capability of transformer-based models to generate chemically diverse and structurally relevant peptidomimetics. The models have shown particular strength in creating compounds that balance novelty with desired drug-like properties.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Transformer-Based Models in Peptidomimetic Design

| Model/Approach | Key Function | Validation Outcome | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| General CLM [32] | Direct conversion of peptides to diverse peptidomimetics | Generates candidates with varying similarity and diminishing peptide-likeness | Broad applicability across different target classes |

| Fine-tuned CLM [32] | Application-specific peptidomimetic design | Produces candidates with optimized properties for specific targets | Enhanced performance for specialized applications |

| GRU-based VAE with Rosetta FlexPepDock [35] | Peptide sequence generation and binding affinity assessment | 15-fold improvement in binding affinity for best β-catenin peptide | Integrates deep learning with physics-based binding assessment |

| TransGEM [36] | Molecule generation from gene expression profiles | Generated molecules with good binding affinity to disease targets | Phenotype-based approach independent of target protein information |

Table 2: Experimental Results for Peptide Inhibitors Designed Using Integrated AI/Physics Approaches

| Target Protein | Peptide Type | Binding Affinity (ICâ‚…â‚€ or Kâ‚„) | Improvement Over Parent Peptide | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-catenin [35] | C-terminal extended peptide | 0.010 ± 0.06 μM | 15-fold better | Fluorescence-based binding assays |

| β-catenin [35] | 6 of 12 designed peptides | Improved binding affinity | Varied | Fluorescence-based binding assays |

| NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) [35] | 2 of 4 tested peptides | Substantially enhanced binding | Significant | Fluorescence-based binding assays |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct Peptide-to-Peptidomimetic Conversion Using Transformer CLMs

Purpose: To generate diverse peptidomimetic candidates from a parent peptide sequence using a transformer-based chemical language model.

Materials:

- Hardware: Workstation with GPU acceleration (minimum 8GB VRAM)

- Software: Python 3.8+, transformer CLM implementation [32]

- Input Data: Parent peptide sequence in standard one-letter code

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Format the parent peptide sequence as a string of one-letter amino acid codes

- Optional: Include known structural constraints or preferred modifications as control tokens

Model Configuration:

- Load pre-trained transformer CLM for peptidomimetics [32]

- Set generation parameters: temperature=0.7, top-k=50, max_length=100 tokens

Sequence Generation:

- Input parent peptide to the model

- Generate multiple candidates (typically 100-1000) through iterative sampling

- Decode output tokens into chemical structures (SMILES or SELFIES representation)

Post-processing:

- Validate chemical structures for synthetic accessibility

- Filter based on drug-likeness criteria (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five)

- Cluster candidates by structural similarity to ensure diversity

Validation:

- Select top candidates for molecular docking against target protein structure

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability

- Synthesize and experimentally test highest-ranking candidates

Troubleshooting:

- If generated structures are too similar to parent peptide, increase temperature parameter

- If generated structures are chemically invalid, implement additional structure validation steps

- For poor synthetic accessibility, incorporate retrosynthesis analysis tools

Protocol 2: Integrated Generative and Structure-Based Design

Purpose: To combine transformer-based generation with physics-based binding assessment for improved peptidomimetic design.

Materials:

- Software: GRU-based VAE, Rosetta FlexPepDock, MD simulation software (e.g., GROMACS) [35]

- Input Data: Target protein structure (PDB format), template peptide-protein complex

Procedure:

- Sequence Generation:

- Employ Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)-based Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with Metropolis Hasting sampling to generate potential peptide sequences [35]

- Reduce sequence search space from millions to hundreds of candidates

Initial Binding Assessment:

- Superimpose generated peptides onto template structure bound to target protein

- Refine peptide-protein complexes using Rosetta FlexPepDock with full flexibility to peptide backbone and side chains [35]

- Rank-order peptides using Rosetta peptide-protein scoring functions

Binding Affinity Refinement:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations on high-ranked complexes

- Calculate binding energies using molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) method [35]

- Select final candidates based on consensus from multiple scoring metrics

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize selected peptidomimetics using solid-phase peptide synthesis or organic chemistry methods

- Evaluate binding affinity using fluorescence-based assays or surface plasmon resonance

- Assess biological activity in cell-based assays

Troubleshooting:

- If Rosetta docking fails to converge, adjust flexibility parameters and increase sampling

- For unstable MD simulations, check initial structure and minimize energy before production run

- When experimental binding does not match predictions, verify force field parameters and solvation model

Visualizations

Workflow for Transformer-Based Peptidomimetic Design

Transformer-Based Peptidomimetic Design Workflow

Structural Peptidomimetics Classification

Structural Classification of Peptidomimetics

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Transformer-Based Peptidomimetic Design

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer CLM [32] | Direct conversion of peptide sequences to diverse peptidomimetics | Pre-trained on peptide-peptidomimetic pairs; generates SELFIES representations |

| Molecular Dynamics Software [35] | Binding pose refinement and affinity calculation | GROMACS, AMBER; MM/GBSA binding energy calculations |

| Rosetta FlexPepDock [35] | Peptide-protein docking and binding energy assessment | Flexible peptide docking with full backbone and side chain flexibility |

| SELFIES Representation [36] | Robust molecular string representation for deep learning | Ensures 100% valid chemical structures during generation |

| PCD Plot & PMA Map [33] | Quantitative analysis of peptidomimetic similarity to target peptide | Alignment-free and alignment-based comparison of Cα–Cβ bond vectors |

| Gene Expression Encoder [36] | Embedding of phenotypic information for conditional generation | Processes gene expression difference values for phenotype-based design |

| Ganoderic Acid T-Q | Ganoderic Acid T-Q, CAS:112430-66-7, MF:C32H46O5, MW:510.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isolindleyin | Isolindleyin, CAS:87075-18-1, MF:C23H26O11, MW:478.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The structure-based design of peptide mimetics represents a frontier in therapeutic development, aiming to modulate challenging biological targets such as protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Protein-peptide interactions mediate 15–40% of all cellular PPIs, making them highly attractive yet difficult targets for therapeutic intervention due to their often shallow and transient binding interfaces [6] [37]. The emergence of accurate computational structure prediction tools, particularly AlphaFold 3, combined with carefully curated structural databases like PDBBind, has created unprecedented opportunities for rational peptide mimetic design. However, these advances come with significant methodological considerations, including data leakage issues in public datasets and the critical need for experimental validation of computational predictions [38] [39].

This Application Note provides detailed protocols for integrating structural data from PDBBind and AlphaFold to advance peptide mimetics research. We present a standardized framework for generating reliable protein-peptide complex structures, validating them against experimental data, and applying them to the design of peptidomimetic inhibitors classified from Class A to Class D based on their similarity to natural peptide precursors [6]. These methodologies are essential for researchers pursuing structure-based design of peptide-based therapeutics, as they address critical gaps in current computational workflows.

Background and Significance

Peptide Mimetics in Therapeutic Development

Peptidomimetics are designed molecules that mimic the binding properties of natural peptide precursors while overcoming their pharmacological limitations, including proteolytic degradation, poor bioavailability, and entropic penalties upon binding [6]. The classification system for peptidomimetics has evolved to better represent the continuum of approaches:

Table: Classification of Peptidomimetics for Therapeutic Development

| Class | Description | Key Features | Therapeutic Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Modified peptides from parent sequence | Limited modified amino acids; backbone closely aligns with bioactive conformation | Maintains high specificity; improved stability over native peptide |

| B | Significantly modified peptides | Non-natural amino acids, major backbone alterations, foldamers (β-peptides, peptoids) | Enhanced metabolic stability; customizable pharmacokinetics |

| C | Small-molecule scaffolds | Complete backbone replacement; projects key residue functionalities | Oral bioavailability; improved tissue penetration |

| D | Functional mimetics | No direct structural link to parent peptide; identified via screening | Drug-like properties; novel intellectual property space |

Class A and B mimetics preserve significant peptide character while addressing stability issues, whereas Class C and D mimetics represent increasingly abstracted small-molecule approaches that maintain therapeutic targeting while achieving superior drug-like properties [6].

Key Databases and Predictive Tools

PDBBind is a comprehensively curated database collecting experimental protein-ligand complex structures and their binding affinities from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). It serves as the primary training resource for most machine learning scoring functions and physics-based binding affinity prediction methods. However, recent analyses have revealed significant data leakage in standard PDBBind benchmarks, where high similarity between proteins and ligands in training and test sets artificially inflates perceived performance [38] [39].

AlphaFold has revolutionized structural biology through deep learning-based protein structure prediction. The recently released AlphaFold 3 extends capabilities to predict structures of complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues. For protein-ligand interactions, AlphaFold 3 demonstrates substantially improved accuracy over traditional docking tools without requiring structural inputs, achieving high accuracy in blind predictions [40].

Integrated Workflow for Structure-Based Peptide Mimetic Design

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive integration of PDBBind and AlphaFold in a structured workflow for peptide mimetic design:

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for structure-based peptide mimetic design combining PDBBind, AlphaFold, and experimental validation with iterative refinement loops.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein-Peptide Complex Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | PDBBind | Training and benchmarking scoring functions | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding affinities; requires cleaning for data leakage |

| LP-PDBBind | Leak-proof training of ML models | Reorganized PDBBind with controlled similarity between splits | |

| BDB2020+ | Independent validation dataset | BindingDB entries post-2020 filtered for low similarity | |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold 3 | Joint structure prediction of biomolecular complexes | Diffusion-based architecture; handles proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Protein-protein and protein-peptide complex prediction | Specialized training for multimeric interfaces | |

| CSP_Rank | Integrative modeling with experimental data | Combines AlphaFold2 with NMR Chemical Shift Perturbation data | |

| Validation Tools | NMR CSP | Experimental validation of binding interfaces | Detects binding-induced structural and dynamic changes |

| NOESY | Cross-validation of structural models | Provides distance restraints for model validation | |

| Specialized Algorithms | Struct2Graph | PPI prediction from 3D structures | Graph attention network; 98.89% accuracy on balanced PPI sets |

| Enhanced Sampling (AFSample2) | Conformational diversity exploration | MSA manipulation for alternative state prediction |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Leak-Proof Structural Datasets