Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions: A Strategic Guide to Hot Spots for Small Molecule Drug Discovery

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to biological processes and represent a promising yet challenging class of therapeutic targets.

Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions: A Strategic Guide to Hot Spots for Small Molecule Drug Discovery

Abstract

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to biological processes and represent a promising yet challenging class of therapeutic targets. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on targeting PPIs through hot spots—critical residues that contribute the majority of the binding energy. We explore the foundational principles of hot spot identification, from the O-ring theory to amino acid composition. The review then details state-of-the-art computational and experimental methodologies for hot spot prediction and application, including machine learning and alanine scanning. Furthermore, we address key challenges such as molecular cooperativity and pocket transience, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation techniques and prediction tools, equipping scientists with a validated framework for advancing PPI-targeted drug discovery programs.

The Blueprint of Binding: Deconstructing Hot Spot Fundamentals and Energetic Landscapes

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) serve as fundamental regulators of diverse biological processes, including signal transduction, cell cycle control, and transcriptional regulation [1]. The binding sites through which these interactions occur are known as protein interfaces. Research over recent decades has revealed that the binding energy within these interfaces is not uniformly distributed; instead, it is concentrated at critical residues known as "hot spots" [2] [3]. These hot spots comprise only a small fraction of the interface yet account for the majority of the binding free energy, making them crucial for understanding the function and stability of protein complexes [2] [4]. The seminal work of Clackson and Wells on human growth hormone binding to its receptor first introduced the hot spot concept, defining them specifically as residues whose mutation to alanine causes a decrease in binding free energy (ΔΔG) of ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol [3]. This definition has become the standard in experimental and computational studies of PPIs.

The identification and characterization of hot spots hold profound implications for drug discovery, particularly in targeting PPIs with small molecules. As protein-protein interactions are often dysregulated in diseases such as cancer, infectious diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders, hot spots represent attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [4] [5]. Despite the challenges presented by the typically large and flat surfaces of PPIs, hot spots provide structural and energetic footholds that small molecules can exploit to modulate these interactions [3] [4]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of hot spot characteristics, prediction methodologies, experimental validation protocols, and their application in drug development, framing this discussion within the context of small molecule targeting research.

Characteristics and Structural Properties of Hot Spots

Energetic and Compositional Profiles

Hot spots exhibit distinctive energetic and compositional profiles that set them apart from other interface residues. Statistically, they constitute approximately 9.5% of interfacial residues yet dominate the binding energy landscape [3]. The amino acid composition of hot spots is notably non-random, with a strong preference for specific residues. Tryptophan (21%), arginine (13.3%), and tyrosine (12.3%) occur with the highest frequency, collectively accounting for nearly half of all hot spot residues [3]. This compositional bias reflects the unique physicochemical properties these residues contribute, including their large surface area, aromaticity, and potential for forming multiple hydrogen bonds and π-interactions.

The structural conservation of hot spots is another defining characteristic. Comparative analyses of protein interfaces reveal that hot spots mutate at a slower rate compared to other surface residues, indicating evolutionary pressure to maintain these critical regions [2] [3]. This conservation extends beyond sequence preservation to include the spatial arrangement of hot spots within the interface. They often cluster together in densely packed regions termed "hot regions," where they function cooperatively to enhance binding affinity and specificity [4]. This modular organization enables proteins to achieve high-affinity binding while maintaining the potential for interaction with multiple partners through similar interface architectures.

Structural Microenvironments and Solvent Exclusion

The structural microenvironments surrounding hot spots follow distinctive patterns that contribute to their energetic importance. The "O-ring" theory proposed by Bogan and Thorn suggests that hot spots are often surrounded by energetically less critical residues that form a ring-like structure, occluding bulk solvent from the hot spot and enhancing its energetic contribution [4]. This theory has been refined through subsequent studies into a "double water exclusion" hypothesis, which provides a more detailed roadmap for understanding the relationship between solvent accessibility and binding affinity in protein interfaces [6].

The solvent accessibility of hot spots follows a consistent pattern: they tend to be more buried within the interface compared to non-hot spot residues. Computational analyses incorporate solvent accessibility parameters such as the change in accessible surface area (ΔASA) upon complex formation, with typical thresholds requiring ΔASA > 49 Ų and ASA in the complex form (ASAcomplex) < 12 Ų for a residue to be considered a potential hot spot [2]. This burial protects the hydrophobic effects and hydrogen bonds that hot spots form from competing water interactions, thereby maximizing their contribution to binding stability.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Hot Spot Residues in Protein-Protein Interfaces

| Characteristic | Description | Experimental/Computational Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Energetic Contribution | ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol upon alanine mutation | Alanine scanning mutagenesis |

| Amino Acid Preference | Trp (21%), Arg (13.3%), Tyr (12.3%) most frequent | Statistical analysis of known hot spots |

| Structural Conservation | Evolve slower than other surface residues | Phylogenetic analysis, sequence alignment |

| Spatial Organization | Tend to cluster in "hot regions" | Structural analysis of protein complexes |

| Solvent Accessibility | Highly buried (ΔASA > 49Ų, ASAcomplex < 12Ų) | Solvent accessibility calculations (e.g., NACCESS) |

| Microenvironment | Often surrounded by O-ring of less critical residues | Structural and energetic analysis |

Computational Prediction Methods for Hot Spots

Feature-Based Machine Learning Approaches

Computational prediction of hot spots has evolved substantially, with feature-based machine learning approaches demonstrating particular success. These methods employ classifiers trained on diverse features extracted from protein sequences, structures, and evolutionary profiles. The PredHS2 method exemplifies this approach, utilizing Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with 26 optimally selected features from an initial set of 600 candidate properties [6]. The feature selection process employs a two-step methodology: first, minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) sorting, followed by sequential forward selection to identify the most discriminative features. Critical features identified through this process include solvent exposure characteristics, secondary structure elements, disorder scores, and various neighborhood properties that capture the structural environment around target residues [6].

Other notable machine learning methods include KFC2 (Knowledge-based FADE and Contacts), which combines features such as atomic density, contact potentials, and solvation energy [3], and Hotpoint, which utilizes empirical potentials and accessibility measures [5]. The performance of these methods is typically evaluated using metrics such as sensitivity, precision, accuracy, F1-score, and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), with comparative analyses demonstrating progressive improvements in prediction accuracy over time [6].

Conservation-Based and Energy-Based Methods

Conservation-based methods represent another important approach for hot spot prediction. The HotSprint database employs an empirical method that combines evolutionary conservation scores from Rate4Site algorithm with solvent accessibility parameters to identify hot spots [2]. The conservation scores are rescaled using amino acid-specific propensities, as different residues have varying likelihoods of functioning as hot spots independent of their sequence position. This method achieved 76.83% accuracy in correlating with experimental hot spots, demonstrating the power of integrating evolutionary information with structural parameters [2].

Energy-based methods constitute a third major category, with tools such as FoldX and Robetta performing computational alanine scanning to estimate the energetic contribution of interface residues [3]. These methods calculate the difference in binding free energy between wild-type and alanine-mutated structures using empirical force fields or physical energy functions. While generally accurate, energy-based approaches tend to be computationally intensive compared to machine learning or conservation-based methods, making them less practical for large-scale screenings but valuable for detailed analyses of specific complexes.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representative Hot Spot Prediction Methods

| Method | Approach | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PredHS2 | Machine Learning | 26 optimal features (solvent exposure, secondary structure, etc.) with XGBoost | F1-score: 0.689 (10-fold CV) [6] |

| HotSprint | Conservation-Based | Conservation scores + solvent accessibility | Accuracy: 76.83% [2] |

| PPI-hotspotID | Machine Learning | Ensemble classifiers with 4 residue features | F1-score: 0.71 [5] |

| KFC2 | Knowledge-Based | Atomic density, contact potentials, solvation | AUC: ~0.70 [3] |

| FoldX | Energy-Based | Computational alanine scanning with empirical force field | Accuracy: ~80% on specific test sets [3] |

Emerging Approaches and Integration with Structural Prediction

Recent advances in deep learning and structural bioinformatics are opening new frontiers in hot spot prediction. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), including Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) and Graph Attention Networks (GATs), have shown remarkable capability in capturing both local patterns and global relationships in protein structures [1]. These architectures naturally represent proteins as graphs with residues as nodes and their interactions as edges, enabling effective learning of structural features relevant to hot spot identification.

The integration of AlphaFold-Multimer predictions represents another significant development. AlphaFold-Multimer has demonstrated exceptional performance in predicting protein-protein complex structures, and its predicted interface residues can be combined with dedicated hot spot prediction methods like PPI-hotspotID to enhance performance [5]. This hybrid approach leverages the complementary strengths of complex structure prediction and residue-level energetic importance assessment, potentially offering more reliable identification of hot spots, particularly for proteins without experimentally determined complex structures.

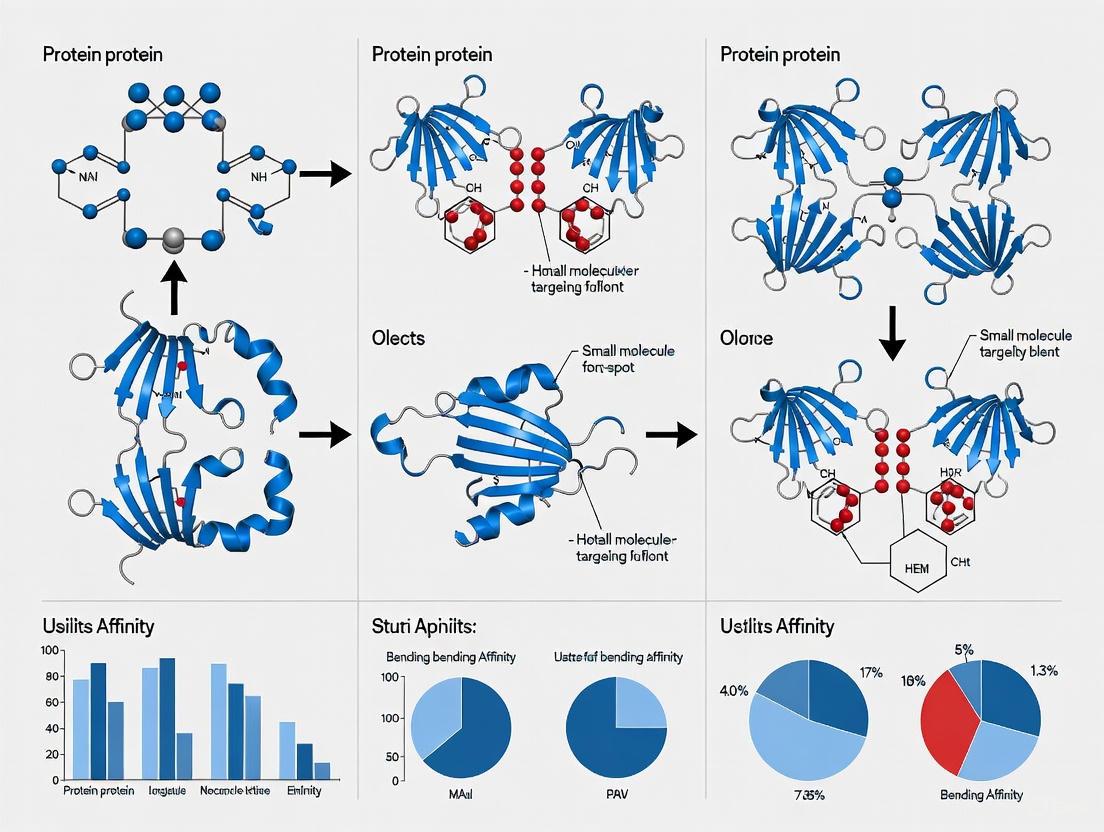

Computational Prediction Workflow for Hot Spots

Experimental Protocols for Hot Spot Validation

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis

Alanine scanning mutagenesis serves as the gold standard for experimental identification and validation of hot spot residues. This technique involves systematically mutating interface residues to alanine and measuring the resulting changes in binding affinity. The experimental protocol begins with site-directed mutagenesis to replace the target residue with alanine, effectively removing all side-chain atoms beyond the β-carbon while minimizing perturbations to protein backbone flexibility [3]. Each mutant protein must then be expressed, purified, and in some cases refolded before binding affinity assessment.

The binding affinity measurements typically employ techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), surface plasmon resonance (SPR), or fluorescence-based binding assays. The change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) is calculated as ΔΔG = ΔGmut - ΔGwt, where ΔGmut and ΔGwt represent the binding free energies of the mutant and wild-type proteins, respectively. Residues yielding ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol are classified as hot spots [3]. While highly informative, traditional alanine scanning is resource-intensive, as each mutant requires individual construction, purification, and analysis. Approaches such as "shotgun scanning" have been developed to increase throughput by creating and analyzing multiple mutants simultaneously [3].

High-Throughput Experimental Methods

To address the scalability limitations of conventional alanine scanning, several high-throughput experimental methods have been developed. The yeast two-hybrid system provides a powerful platform for screening protein interactions and identifying critical residues [7]. In this system, the protein of interest is fused to a DNA-binding domain, while its interaction partner is fused to an activation domain. Mutation of hot spot residues typically disrupts the interaction, which can be detected through reporter gene expression.

Other high-throughput approaches include co-immunoprecipitation combined with mutational analysis, protein fragment complementation assays, and deep mutational scanning techniques that leverage next-generation sequencing to assess the functional consequences of thousands of mutations in parallel [5]. While these methods may not provide the precise energetic measurements of alanine scanning, they enable large-scale identification of residues critical for protein interactions, effectively expanding the definition of hot spots to include any residues whose mutation significantly impairs or disrupts PPIs [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hot Spot Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine Scanning Kits | Site-directed mutagenesis for hot spot validation | Commercial kits (e.g., QuikChange) |

| Expression Vectors | Protein expression and purification for binding assays | pET, pGEX series vectors |

| Binding Assay Reagents | Measuring binding affinity changes | ITC reagents, SPR chips, fluorescence dyes |

| Hot Spot Databases | Reference data for validation and benchmarking | ASEdb, BID, SKEMPI, PPI-HotspotDB [3] [5] |

| Prediction Servers | Computational hot spot identification | HotSprint, KFC2, PredHS2, PPI-hotspotID [2] [5] |

| Structural Biology Tools | Visualization and analysis of protein interfaces | PyMOL, Chimera, NACCESS [2] |

| KRAS G12C inhibitor 46 | KRAS G12C inhibitor 46, MF:C32H33F2N7O2, MW:585.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-mannose-13C6,d7 | D-mannose-13C6,d7, MF:C6H12O6, MW:193.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Therapeutic Targeting of Hot Spots

Hot Spots in Drug Discovery

The therapeutic targeting of hot spots represents a promising strategy for modulating PPIs with small molecules. Despite the historical challenges presented by the large and relatively flat surfaces typical of protein interfaces, hot spots provide localized regions of high energetic contribution that can be exploited by small molecules [4]. These regions often exhibit structural and physicochemical properties more amenable to small-molecule binding, including concave topography, higher hydrophobicity, and preorganization in the unbound state [4]. The successful development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting hot spots in proteins such as Bcl-2, MDM2-p53, and IL-2 has validated this approach and stimulated continued research in this area [3] [4].

Hot spots facilitate drug design in two primary ways. First, they can identify druggable binding sites within larger protein interfaces, providing starting points for docking and screening campaigns [3]. Second, the relative structural rigidity of hot spots compared to surrounding interface regions can be leveraged in structure-based drug design, as their conformations tend to be more conserved between bound and unbound states [4]. Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that hot spots often exist in preformed configurations that resemble their bound-state geometry, reducing the entropic penalty upon small-molecule binding [4].

Integration with Modern Drug Discovery Platforms

The integration of hot spot analysis with modern drug discovery platforms has created powerful workflows for PPI modulator development. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) approaches particularly benefit from hot spot information, as they often identify small fragments that bind to these energetically important regions [4]. Biophysical techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), X-ray crystallography, and thermal shift assays can detect the binding of small fragments to hot spots, even with weak affinity, providing starting points for medicinal chemistry optimization.

Computational approaches further enhance this integration. FTMap, a computational mapping server, identifies hot spots on protein surfaces by determining consensus regions where multiple small organic probes bind [5]. When applied to protein-protein interfaces, FTMap can pinpoint regions likely to bind small molecules, guiding experimental screening efforts. The combination of these computational mapping approaches with experimental fragment screening creates a powerful cycle for identifying and validating small molecules that target hot spots, accelerating the development of PPI modulators into clinical candidates.

Hot Spot-Driven Drug Discovery Pipeline

Hot spots represent the energetic powerhouses of protein-protein interfaces, contributing disproportionately to binding affinity while maintaining distinct structural and evolutionary characteristics. Their identification through both computational and experimental methods has matured significantly, with current approaches achieving robust prediction accuracy by integrating multiple features and advanced machine learning algorithms. For drug discovery professionals targeting PPIs, hot spots offer strategic footholds for small molecule intervention, transforming previously "undruggable" targets into tractable opportunities. As prediction methods continue to evolve through deep learning and integration with structural biology advances, and as experimental techniques increase in throughput and precision, the systematic identification and targeting of hot spots will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in therapeutic development for diseases driven by aberrant protein interactions.

The O-ring theory, first introduced by Bogan and Thorn in 1998, represents a foundational principle for understanding the architecture and energetic landscape of protein-protein interfaces [8] [9]. This theory, also termed the "water exclusion" hypothesis, posits that the stability of a protein complex is governed by a small number of energetically outstanding residues, known as hot spots, which are typically surrounded by a ring of residues that are energetically less important [8]. This surrounding ring functions to occlude bulk water molecules from the hot spot, creating a local environment with a lower dielectric constant that enhances specific electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions critical for binding stability [8] [9]. The profound insight offered by this theory has shaped experimental and computational approaches to protein-protein interaction analysis for decades.

The original O-ring theory has subsequently been refined through further research. Li and Liu proposed a "double water exclusion" hypothesis that accepts the existence of a protective ring surrounding the hot spot but further assumes that the hot spot itself is water-free [8] [6]. They computationally modeled this water-free hot spot using a biclique pattern—defined as two maximal groups of residues from two chains in a protein complex where every residue contacts all residues in the opposing group [8]. This dense interaction network leaves no sufficient room between residues to accommodate water molecules, representing an interface structure with zero-water tolerance that enhances binding stability through collective forces of multiple, dense atom-atom pairs [8]. This refinement theoretically strengthens and signifies the earlier "hot region" proposition by Keskin et al., which described assemblies of hot residues within densely packed regions with extensive interaction networks [8].

Table: Key Theoretical Models of Protein Binding Site Architecture

| Theory Name | Proposed/Refined By | Core Principle | Structural Organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-Ring Theory (Water Exclusion) | Bogan & Thorn (1998) | Hot spots surrounded by less important residues that exclude solvent | Central hot spot → Ring of occluding residues |

| Double Water Exclusion | Li & Liu (2009) | Hot spot itself is water-free, in addition to being surrounded by protective ring | Water-free hot spot → Protective ring → Bulk solvent |

| Hot Region Concept | Keskin et al. (2005) | Assemblies of hot residues within densely packed regions with interaction networks | Clustered hot spots forming cooperative networks |

| Biclique Pattern | Li & Liu (2009) | Two maximal residue groups with all-to-all contacting interactions | Maximal clusters of residues with complete inter-group contacts |

The O-ring theory's applicability has been extended beyond protein-protein interactions. Research has demonstrated that a similar architectural principle governs protein-DNA interfaces, where hot spots are organized in the central region of the interface, though with a different residue composition biased toward positively charged residues (Arginine and Lysine) to facilitate DNA binding [9]. This extension underscores the fundamental nature of solvent exclusion principles across different biological complex types.

Experimental Methodologies for Hot Spot Characterization

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis

Alanine scanning mutagenesis remains the established experimental standard for identifying hot spot residues and validating the O-ring theory [10] [9]. This method involves systematically mutating each interface residue to alanine and measuring the resulting impact on binding affinity [10]. A residue is typically defined as a hot spot if its mutation to alanine causes a substantial drop in binding affinity (ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [6] [9]. The experimental procedure follows a standardized protocol: first, target residues for mutation are selected based on interface localization; second, site-directed mutagenesis is performed to create alanine substitutions; third, binding affinity changes are quantified using techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR); finally, residues are classified as hot spots or null spots based on the measured energy thresholds [10] [9].

The databases collecting experimental alanine scanning data include the Alanine Scanning Energetics Database (ASEdb), Binding Interface Database (BID), SKEMPI database, and Alexov_sDB [6]. These databases have enabled large-scale analysis of hot spot properties and provided training data for computational prediction methods. Despite being considered the gold standard, alanine scanning mutagenesis is costly, time-consuming, and not always applicable to all protein systems, particularly those with highly charged interfaces like protein-DNA complexes [9].

Protein Painting Technique

A novel experimental method called "protein painting" has emerged as a powerful tool for rapidly identifying solvent-excluded hot spots within native protein-protein interfaces [11]. This technique employs small molecules as molecular paints that tightly coat the exposed surfaces of protein complexes but cannot access solvent-excluded hot spots between interacting native proteins [11]. The experimental workflow consists of several key steps: first, a pulse of small-molecule paints (e.g., RBB, AO50, R49, ANSA) is applied in vast molar excess to native preformed protein complexes; second, non-bound paint molecules are rapidly removed using a Sephadex G25 molecular sieve quick spin column; third, the painted protein-protein interactions are dissociated; finally, the proteins are linearized, digested with trypsin, and sequenced by mass spectrometry [11].

The fundamental principle underlying this technique is that paint molecules block trypsin cleavage sites on coated protein surfaces, while unmodified contact points between protein partners remain accessible to proteolysis [11]. Consequently, only peptides derived from interaction interfaces emerge as positive hits in mass spectrometry analysis. This method has been successfully validated on the interleukin-1β complex (IL1β ligand, receptor IL1R1, and accessory protein IL1RAcP), revealing critical contact regions that were then targeted with inhibitory peptides and monoclonal antibodies that abolished IL1β cell signaling [11]. The major advantage of protein painting is its ability to directly identify the amino acid sequence of physically interacting regions of native proteins without requiring protein modification through crosslinking, mutation, or genetic tagging [11].

Fragment Screening Approaches

Fragment-based screening methods provide another experimental avenue for identifying hot spots relevant to drug discovery [10]. The Structure-Activity Relationship by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (SAR by NMR) method screens libraries of fragment-sized organic compounds for binding to target proteins using NMR, with fragments clustering at ligand binding sites [10]. Similarly, the Multiple Solvent Crystal Structures (MSCS) method involves determining X-ray structures of a target protein in aqueous solutions containing high concentrations of organic co-solvents, then superimposing these structures to find consensus binding sites that accommodate multiple organic probes [10]. These consensus sites identified by fragment screening represent surface regions with high propensity for ligand binding and have been shown to frequently coincide with functionally important regions of proteins [10].

Table: Experimental Methods for Hot Spot Identification

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Output | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis | Measure binding affinity changes after mutation to alanine | ΔΔG values for each mutated residue | Direct thermodynamic measurement; considered gold standard | Time-consuming; expensive; not always applicable |

| Protein Painting | Small molecule dyes coat exposed surfaces but not interfaces | Mass spectrometry peptides from interaction regions | Works on native proteins; rapid results | Requires optimization of painting conditions |

| Fragment Screening (SAR by NMR, MSCS) | Identify consensus sites binding multiple small molecules | Hot spot locations based on fragment clustering | Identifies druggable sites; provides structural information | Requires specialized equipment/expertise |

| Computational Solvent Mapping (FTMap) | Computational analog of MSCS using molecular probes | Ranked consensus sites based on probe clustering | Fast; low cost; web server available | Computational approximation of experimental methods |

Computational Prediction Methods

Feature-Based Machine Learning Approaches

Computational prediction of hot spots has advanced significantly with the adoption of machine learning methods that leverage various features derived from protein sequence and structure [6]. The PredHS2 method represents the state-of-the-art in this category, employing Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) trained on a comprehensive set of 26 optimal features selected from an initial pool of 600 candidate features [6]. These features encompass several categories: sequence features include amino acid composition, evolutionary conservation, and pairing potential; structural features incorporate solvent accessible surface area (SASA), protrusion index, atomic density, and secondary structure elements; energy features involve van der Waals contacts, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding potentials; and neighborhood properties capture information about the local environment around target residues using both Euclidean and Voronoi neighborhood definitions [6].

The feature selection process in PredHS2 employs a two-step approach: first, the Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) method ranks features by their importance, followed by a sequential forward selection (SFS) procedure that adds features until prediction performance no longer improves [6]. Notable novel features found to be particularly discriminative include solvent exposure characteristics, secondary structure features, and disorder scores [6]. When evaluated on independent test sets, PredHS2 achieved superior performance compared to other machine learning algorithms and existing prediction methods, demonstrating the power of sophisticated feature engineering and selection combined with advanced machine learning algorithms [6].

Biclique Pattern Detection

To computationally model the "double water exclusion" hypothesis, Li and Liu developed a method to identify biclique patterns at protein-protein interfaces [8]. The algorithm processes protein complexes from the Protein Data Bank through several stages: first, interatomic distances are calculated for all possible atom pairs between two chains; second, the chains are represented as a bipartite graph based on distance information; third, maximal biclique subgraphs are identified from all bipartite graphs to locate biclique patterns at interfaces [8]. A residue contact is typically defined as existing when the distance between any two atoms of the residues is below the sum of their van der Waals radii plus the diameter of a water molecule (2.75Ã…) [8].

The key properties of biclique patterns include their non-redundant occurrence in PDB and correspondence with hot spots when the solvent-accessible surface area of the pattern in the complex form is small [8]. Through extensive queries to hot spot databases, biclique patterns have been verified to be rich in true hot residues, providing a structural topology that reflects the double water exclusion principle [8]. This method offers a structure-based approach to hot spot prediction that directly embodies the theoretical framework of solvent exclusion at binding interfaces.

Applications to Drug Discovery

The understanding of O-ring theory and solvent exclusion principles has profound implications for drug discovery, particularly in targeting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with small molecules [12] [13]. PPIs have traditionally been challenging therapeutic targets because their interfaces often appear flat and featureless, lacking obvious binding pockets for small molecules [11]. However, the recognition that binding energy is concentrated in hot spots surrounded by solvent-excluding rings has provided a strategic approach to addressing this challenge [13].

Hot Spot-Based Inhibitor Design

Hot spot-based design of small-molecule inhibitors leverages the knowledge that certain regions at PPI interfaces contribute disproportionately to binding energy and may present more druggable sites [13]. This approach typically follows a systematic procedure: first, hot spots are identified experimentally through alanine scanning or computationally using prediction methods; second, the structural and physicochemical properties of these hot spots are characterized to assess their "druggability"; third, fragment-based screening or structure-based design is employed to identify small molecules that target these regions; finally, initial hits are optimized for potency and selectivity [13]. Successful examples of this strategy demonstrate the importance of hot spots in discovering potent and selective PPI inhibitors [13].

Relationship Between Hot Spot Concepts

A critical insight for drug discovery comes from understanding the relationship between two different hot spot concepts: the energetic hot spots identified by alanine scanning mutagenesis and the ligand-binding hot spots identified by fragment screening [10]. Research comparing these two types of hot spots has revealed that they are largely complementary—residues protruding into hot spot regions identified by computational mapping or experimental fragment screening are almost always themselves hot spot residues as defined by alanine scanning experiments [10]. However, only a minority of hot spots identified by alanine scanning represent sites that are potentially useful for small inhibitor binding, and it is this subset that is identified by experimental or computational fragment screening [10]. This distinction is crucial for prioritizing targets for drug discovery efforts.

Table: Comparison of Hot Spot Types in Drug Discovery

| Hot Spot Type | Identification Method | Key Characteristics | Relevance to Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energetic Hot Spots | Alanine scanning mutagenesis | High ΔΔG upon mutation (>2.0 kcal/mol); often enriched in Trp, Arg, Tyr | Define critical regions for binding energy; indicate potential target regions |

| Ligand-binding Hot Spots | Fragment screening (X-ray, NMR) | Consensus sites binding multiple fragments; specific physicochemical properties | Directly indicate druggable sites; starting points for inhibitor design |

| Biclique Patterns | Structural graph theory | Dense residue clusters with all-to-all contacts; water exclusion properties | Suggest stable interaction networks; potential for disruptive targeting |

Visualization of Core Concepts and Methodologies

O-Ring Theory Architectural Principles

Protein Painting Experimental Workflow

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Solvent Exclusion Studies

| Category | Resource/Tool | Specific Examples | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Reagents | Molecular Paints | RBB, AO50, R49, ANSA [11] | Protein painting technique | Rapid on-rates, slow off-rates, trypsin blockade |

| Databases | Hot Spot Databases | ASEdb, BID, SKEMPI [6] | Training and validation | Curated experimental ΔΔG values |

| Databases | Protein Interaction Networks | HPRD, MINT, STRING, DIP [14] [15] | Contextual analysis | Protein-protein interaction maps |

| Computational Tools | Hot Spot Prediction Servers | PredHS2, SpotOn, FTMap [6] [10] | Computational identification | Machine learning, energy-based methods |

| Computational Tools | Structural Analysis | NACCESS [8] [16] | Solvent accessibility calculation | ASA calculations for interface definition |

| Computational Tools | Biclique Pattern Mining | Custom algorithm [8] | Double water exclusion modeling | Identifies dense residue clusters |

| Experimental Kits | Alanine Scanning Kits | Commercial mutagenesis kits | Experimental validation | Site-directed mutagenesis |

| Analytical Software | Molecular Visualization | VMD [9], Cytoscape [14] | Structure analysis and visualization | Interface characterization, network analysis |

The O-ring theory and its subsequent refinements provide a fundamental architectural framework for understanding the organization and energetics of protein binding sites. The principle of solvent exclusion represents a unifying concept across diverse biological interactions, from protein-protein to protein-DNA complexes. Experimental methods ranging from traditional alanine scanning to innovative protein painting techniques continue to validate and refine these theoretical models, while computational approaches increasingly enable accurate prediction of hot spots. The integration of these principles into drug discovery pipelines, particularly through hot spot-based inhibitor design, has created promising avenues for targeting previously challenging protein-protein interactions. As these methods continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the molecular principles governing biomolecular recognition and enable more effective therapeutic interventions.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to virtually all biological processes, and the targeted disruption of these interfaces with small molecules represents a promising therapeutic strategy. The conceptual breakthrough that made this approach feasible was the discovery that binding energy is not distributed evenly across an interface but is concentrated at specific "hot spot" residues. This whitepaper delves into the molecular and structural underpinnings of why three amino acids—tryptophan (Trp), tyrosine (Tyr), and arginine (Arg)—are disproportionately enriched at these hot spots. We synthesize data from large-scale mutagenesis studies, structural analyses, and computational predictions to explain the unique biochemical properties that equip these residues for dominant roles in binding energy. Furthermore, we detail the experimental and computational methodologies essential for hot spot identification and characterization, framing this knowledge within the context of rational drug discovery for PPI targets.

Protein-protein interactions are often governed by a small subset of interface residues, known as hot spots, which contribute the majority of the binding free energy. A residue is typically defined as a hot spot if its mutation to alanine causes a significant change in binding free energy (ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [6]. The seminal work by Bogan and Thorn in 1998 first systematically analyzed these regions, revealing that tryptophan, tyrosine, and arginine are the most frequently occurring residues in hot spots [17].

From a drug discovery perspective, hot spots are critically important because they represent druggable epitopes within often large and flat PPI interfaces. While the complete interface may encompass 1,000-2,000 Ų, the central hot spot region often covers an area comparable to the size of a typical small-molecule binding site (approximately 250-900 Ų) [18]. This insight overturned the previous dogma that PPIs were "undruggable" and provided a roadmap for designing small molecules that can potently and specifically disrupt these interactions. Successful targeting of PPIs has since led to several FDA-approved drugs, such as venetoclax, and many more candidates in clinical trials [19] [20].

Quantitative Propensity of Tyr, Trp, and Arg in Hot Spots

Statistical analysis of alanine scanning mutagenesis databases provides unambiguous evidence for the enrichment of specific amino acids in hot spots. The following table summarizes the propensity of different amino acids to function as hot spot residues, compiled from large-scale experimental studies.

Table 1: Amino Acid Propensities in Protein-Protein Interaction Hot Spots

| Amino Acid | Frequency in Hot Spots (%) | Key Biochemical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan (W) | 21% | Large, hydrophobic indole ring; Amphipathic; Can form π-π, cation-π, and hydrogen bond interactions. |

| Arginine (R) | 13.1% | Positively charged guanidinium group; Can form multiple bidentate hydrogen bonds and cation-Ï€ interactions. |

| Tyrosine (Y) | 12.3% | Hydrophobic aromatic ring; Amphipathic; Phenolic -OH group can form strong hydrogen bonds. |

| Other Residues | ~53.6% (combined) | Varying properties; includes other hydrophobic (I, L, V) and polar (N, D, E) residues. |

Data derived from Bogan & Thorn (1998) and subsequent analyses [17] [6].

The data shows that Trp, Arg, and Tyr together constitute nearly half of all hot spot residues, a significant overrepresentation compared to their overall abundance in protein sequences. This enrichment is a direct consequence of their unique and versatile biochemical properties, which enable them to make outsized contributions to binding affinity.

Structural and Energetic Basis for Dominance

The dominance of Tyr, Trp, and Arg at hot spots is not accidental but stems from a combination of structural and energetic factors that maximize binding energy within a minimal footprint.

Versatile Molecular Interactions

These three residues are uniquely capable of engaging in multiple, strong non-covalent interactions:

- Tryptophan: Its bulky, dual-ring indole side chain is a versatile interaction platform. It is predominantly hydrophobic, providing substantial energy through the hydrophobic effect when shielded from solvent. The indole nitrogen can serve as both a strong hydrogen bond donor and acceptor. Furthermore, the electron-rich ring system can engage in π-π stacking with other aromatic residues and cation-π interactions with positively charged residues like arginine and lysine [17] [6].

- Tyrosine: Tyr shares the hydrophobic character of Trp via its phenolic ring, contributing to van der Waals interactions and the hydrophobic effect. Its key feature is the phenolic hydroxyl group, which can form high-energy hydrogen bonds that are stronger than those from main-chain carbonyls or amides due to the electron-withdrawing nature of the aromatic ring. This makes Tyr amphipathic, capable of straddling hydrophobic and polar regions of the interface [17].

- Arginine: The guanidinium group of Arg is a potent source of electrostatic interactions. Its planar structure, with multiple nitrogen atoms, allows it to form multiple, often bidentate hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups on the binding partner. This group can also participate in cation-Ï€ interactions and salt bridges with negatively charged residues like aspartate and glutamate [17] [6].

The O-Ring and Solvent Exclusion Effect

A critical theory explaining the architecture of hot spots is the "O-ring" model proposed by Bogan and Thorn [17]. This model posits that the central hot spot residues (frequently containing Trp, Tyr, and Arg) are often surrounded by a ring of energetically less critical, but tightly packed, residues. The primary function of this O-ring is to occlude bulk solvent from the central hot spot.

The exclusion of water is crucial because the strong interactions formed by Trp, Tyr, and Arg (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic effects) are significantly amplified in a low-dielectric environment. When water is displaced, the effective strength of these interactions increases dramatically. The O-ring theory has been refined by the "double water exclusion" hypothesis, which further emphasizes the role of structured water molecules in shaping binding affinity [6].

Methodologies for Experimental Identification and Analysis

The identification and validation of hot spots rely on a combination of experimental and computational techniques. The gold standard is alanine scanning mutagenesis, but several other methods provide complementary data.

Core Experimental Protocol: Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis

This is the primary experimental method for identifying hot spot residues.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Alanine Scanning

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Wild-Type Gene Construct | Template for site-directed mutagenesis to create alanine point mutants. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | For introducing specific point mutations (e.g., to alanine) into the gene of interest. |

| Recombinant Protein Expression System | (e.g., E. coli, insect cells). To produce and purify wild-type and mutant proteins. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) / Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) | Label-free techniques to measure binding kinetics (KD, Kon, Koff) between protein partners. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Provides direct measurement of binding affinity (KD) and thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS). |

Detailed Workflow:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Identify all residues at the PPI interface via structural analysis (e.g., X-ray crystallography). Systematically mutate each interfacial residue to alanine, which removes the side-chain atoms beyond the Cβ while preserving the protein backbone, thereby isolating the functional contribution of that side chain.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify the wild-type protein and each alanine mutant to homogeneity.

- Binding Affinity Measurement: Determine the binding affinity of the wild-type complex and each mutant complex using a technique like SPR or ITC.

- Free Energy Calculation: For each mutant, calculate the change in binding free energy: ΔΔG = ΔG(mutant) - ΔG(wild-type). A residue is typically classified as a hot spot if ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol [6].

Supporting and Alternative Methodologies

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Utilizes diverse chemical libraries to identify small molecules that disrupt a PPI. While not a direct mapping technique, a successful hit can indicate the presence of a druggable hot spot [19].

- Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): Particularly suited for targeting the discontinuous hot spots of PPI interfaces. Small, low molecular weight fragments are screened for binding to the target protein. These fragments often bind to sub-pockets within the hot spot region and can be linked or elaborated into high-affinity inhibitors [19] [18].

- Biophysical and Structural Techniques: X-ray crystallography and NMR are used to solve the structures of protein complexes, revealing atomic-level details of the interactions at the interface. This structural information is invaluable for rational drug design.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating these methods to identify and target hot spots.

Computational Prediction of Hot Spots

Given the cost and time associated with experimental methods, robust computational prediction of hot spots is a major focus in bioinformatics. Modern machine learning (ML) approaches have demonstrated high accuracy.

Feature Selection for Machine Learning

Effective prediction relies on extracting informative features from protein sequences and structures. The PredHS2 method, for example, uses a two-step feature selection process (mRMR followed by sequential forward selection) to identify 26 optimal features from an initial set of 600 [6]. Key features include:

- Evolutionary Conservation: Hot spot residues are often more evolutionarily conserved than non-hot spot interface residues.

- Solvent Accessibility / Exclusion: Measures the extent to which a residue is buried at the interface, a key tenet of the O-ring theory.

- Atomic Packing Density: Describes how tightly atoms are packed around a residue.

- Energy Terms: Estimates of various interaction energies (e.g., van der Waals, electrostatic).

- Secondary Structure and Disorder Scores: Propensity for certain structural elements can be indicative.

- Amino Acid-Specific Features: Including the inherent physicochemical properties of the residue.

Machine Learning Algorithms

Classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests (RF), and more recently, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) are trained on datasets of known hot spots and non-hot spots (e.g., from ASEdb or BID databases) using the selected features [6]. The XGBoost-based PredHS2 model, for instance, has been shown to outperform other state-of-the-art methods.

Application in Small Molecule Drug Discovery

The strategic importance of hot spots is fully realized in the design of PPI modulators. Understanding the chemical composition of hot spots directly informs the design of small-molecule inhibitors.

- Mimicking Key Residues: Small molecules can be designed to mimic the interactions of a critical hot spot residue. For example, an inhibitor might incorporate a heteroaromatic ring system to mimic the indole of tryptophan or a guanidinium group to mimic arginine, thereby recapitulating the essential binding interactions [18].

- Targeting Hot Spot Pockets: Although PPI interfaces are generally flat, the regions around central Trp, Tyr, and Arg residues often contain small, druggable pockets that can be targeted by fragments or small molecules. This is the basis for the success of FBDD in this field [19] [18].

- Case Study: Bcl-2 Family Proteins: The successful development of venetoclax, a Bcl-2 inhibitor, exemplifies hot spot targeting. The drug binds to a hydrophobic cleft on Bcl-2, a cleft that normally engages with a BH3 α-helix from its binding partner. The inhibitor effectively mimics key hydrophobic and aromatic hot spot residues of the native helix [18].

The diagram below outlines the strategic pipeline for translating hot spot knowledge into a therapeutic lead.

The dominance of tyrosine, tryptophan, and arginine in protein-protein interaction hot spots is a direct consequence of their superior and versatile molecular interaction capabilities. Their ability to contribute significantly to binding affinity through a combination of the hydrophobic effect, hydrogen bonding, and complex electrostatic interactions, all within the context of a solvent-excluded environment, makes them indispensable for high-affinity binding. The continued refinement of experimental and computational methods for hot spot identification, coupled with advanced drug design strategies like FBDD, ensures that targeting these critical residues will remain a cornerstone of therapeutic PPI modulation. As our understanding of the nuanced roles these residues play in specific complexes deepens, so too will our ability to design potent and selective small-molecule drugs for previously intractable targets.

The study of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) is pivotal for understanding cellular physiology and designing targeted therapeutic interventions. Within the vast landscape of protein interfaces, hot spots—a small subset of residues accounting for the majority of binding free energy—have emerged as critical targets. Recent research has revealed that these hot spots are not randomly distributed but rather form clustered, cooperative networks known as hot regions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the transition from identifying individual hot spots to understanding the organization and function of hot regions. Framed within the context of small molecule targeting research, we detail experimental and computational methodologies for identifying these features, analyze their structural and energetic properties, and discuss their implications for drug discovery, particularly in stabilizing or disrupting PPIs with molecular glues and other small molecules.

Protein-protein interactions are fundamental to virtually all biological processes, from signal transduction to immune response. The binding energy in these complexes is not uniformly distributed across the interface; instead, it is concentrated at specific residues termed "hot spots" [21]. Experimentally, hot spots are defined as residues whose mutation to alanine causes a significant increase in binding free energy (ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [22] [21]. From a drug discovery perspective, these residues represent promising targets for small molecules aimed at modulating PPIs.

A critical advancement in this field has been the recognition that hot spots tend to cluster together within protein interfaces, forming what are known as "hot regions" [23] [21]. These are defined as spatially clustered sets of three or more hot spot residues [23]. This clustering is not merely structural; it reflects functional cooperativity, where the collective contribution of clustered residues to binding affinity exceeds the sum of their individual contributions. For researchers targeting PPIs, understanding these cooperative networks is essential, as targeting an entire hot region may prove more effective than targeting individual hot spots.

Methodologies for Identifying Hot Spots and Hot Regions

Experimental Approaches

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis

Alanine scanning mutagenesis remains the gold standard for experimental identification of hot spots.

Protocol:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduce point mutations to substitute target interface residues with alanine, one at a time.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify both wild-type and mutant proteins.

- Binding Affinity Measurement: Determine the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) using techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

- Hot Spot Classification: Residues whose alanine substitution results in ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol are classified as hot spots [22] [21].

Limitations: This process is time-consuming, expensive, and low-throughput, which has motivated the development of computational alternatives.

Structural and Biophysical Techniques

- X-ray Crystallography: Reveals atomic-level details of interface architecture and resident water molecules.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Provides information on dynamics and transient interactions.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Used in fragment-based screening to identify small molecules that bind at PPI interfaces [24].

Computational Prediction Methods

Computational methods offer high-throughput alternatives for hot spot and hot region prediction. These can be broadly categorized as sequence-based, structure-based, or machine learning-driven.

Table 1: Key Computational Methods for Hot Spot Prediction

| Method Name | Type | Input | Key Features | Performance (ACC/MCC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) [22] | Machine Learning | Protein Complex Structure | Hybrid features from target residue and spatial neighbors (mirror-contact & intra-contact residues) | ACC: 82.1%, MCC: 0.459 (5-fold CV) |

| PPI-hotspotID [25] | Machine Learning | Free Protein Structure | Conservation, amino acid type, SASA, and gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) | Recall: 0.67, Precision: 0.76, F1-score: 0.71 |

| HotPoint [23] | Knowledge-Based | Protein Complex Structure | Accessible surface area (ASA) and knowledge-based pair potentials | N/A |

| KFC2 [22] | Machine Learning | Protein Complex Structure | Structural features and biochemical properties | Benchmarking available in independent studies |

| Robetta [22] | Energy-Based | Protein Complex Structure | Free energy function calculations | N/A |

| FOLDEF [22] | Energy-Based | Protein Complex Structure | Quantitative estimation of interaction energy | N/A |

Feature Extraction for Machine Learning

Effective machine learning models depend on carefully selected features:

- Evolutionary Conservation: Calculated using Shannon entropy from multiple sequence alignments [26] [27].

- Structural Features: Solvent accessible surface area (SASA), pairwise residue potentials, atomic contacts, and packing density [22] [23].

- Hybrid Spatial Features: Incorporating information from spatial neighbor residues (mirror-contact and intra-contact residues) significantly improves prediction accuracy [22].

Hot Region Identification Protocol

The HotRegion database provides a systematic framework for identifying hot regions [23]:

- Interface Residue Definition: Two residues from different chains are considered in contact if the distance between any of their atoms is less than the sum of their van der Waals radii plus 0.5 Ã….

- Hot Spot Prediction: Predict hot spots using a method like HotPoint, based on ASA and knowledge-based pair energies.

- Network Construction: Represent hot spots as nodes in a network, connecting them with edges if the distance between their Cα atoms is < 6.5 Å.

- Cluster Identification: Find connected components in the network; components with ≥3 nodes are defined as hot regions.

Structural and Functional Characteristics of Hot Regions

Spatial Clustering of Conserved Residues

Evolutionarily conserved residues at protein interfaces show significant spatial clustering. Analysis shows that 96.7% of homodimer interfaces and 86.7% of heterocomplex interfaces have conserved positions clustered within the interface region [26]. The degree of spatial clustering (Ms) can be quantified using the average inverse distance between all pairs of conserved residues [26] [27]:

[ Ms = \frac{1}{N{\text{pairs}}} \sum{i=1}^{Ns-1} \sum{j=i+1}^{Ns} \left( \frac{1}{r_{ij}} \right) ]

Where ( Ns ) is the number of conserved residues and ( r{ij} ) is the distance between residues i and j.

Relationship Between Hot Regions and Hot Spots

Hot regions serve as functional modules where hot spots are concentrated. Analysis reveals that approximately 60% of experimental hot spot residues are localized to these conserved residue clusters [26]. This relationship has important implications for mutagenesis studies and drug targeting.

Table 2: Amino Acid Preferences in Hot Regions

| Residue Type | Preference in Hot Regions | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan (Trp) | Strongly favored | Highest propensity, often central to hot regions |

| Tyrosine (Tyr) | Strongly favored | Aromatic, contributes to packing and interactions |

| Arginine (Arg) | Favored | Positive charge, forms salt bridges and hydrogen bonds |

| Hydrophobic (Leu, Ile, Met) | Favored | Enhance binding through hydrophobic effect |

| Charged (Asp, Glu, Lys) | Less common | Less frequent than aromatic and hydrophobic residues |

Cooperativity Within Hot Regions

Hot regions exhibit cooperativity, where the energetic contribution of the cluster is greater than the sum of individual hot spots. This cooperativity arises from:

- Dense Packing: Tightly packed regions exclude water molecules, enhancing electrostatic interactions [21].

- Networked Interactions: Hot spots within a region form extensive interaction networks with mutual stabilization [21].

- Additivity Between Regions: While contributions within a hot region are cooperative, the contributions of independent hot regions to overall binding affinity are typically additive [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Hot Regions

Table 3: Statistical Analysis of Conserved Residue Clustering at Protein Interfaces

| Interface Type | Interfaces with Clustered Conserved Residues | Interfaces with Multiple Sub-Clusters | Hot Spots in Conserved Clusters | Preferred Residue Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein (Homodimers) | 96.7% [26] | Common in larger interfaces [26] | ~60% [26] | Hydrophobic, Aromatic, Arg [26] |

| Protein-Protein (Heterocomplexes) | 86.7% [26] | Common in larger interfaces [26] | ~60% [26] | Hydrophobic, Aromatic, Arg [26] |

| Protein-RNA | 77.8% [27] | Multiple sub-clusters observed [27] | 51.5% [27] | Hydrophobic, Aromatic, Arg [27] |

The data consistently shows that conserved residues cluster significantly across different interface types, with a strong correlation between these clusters and experimentally determined hot spots.

Applications in Small Molecule Targeting Research

Molecular Glues for PPI Stabilization

Molecular glues (MGs) are small molecules that bind cooperatively at PPI interfaces, stabilizing otherwise transient interactions [24]. These compounds represent a promising strategy for targeting hot regions.

Case Study: 14-3-3/ERα Stabilization [24]

- Fragment-Based Screening: Using disulfide-tethering technology to identify cysteine-reactive fragments binding at the 14-3-3/client interface.

- Structure-Guided Optimization: X-ray crystallography to guide fragment linking and optimization.

- Cellular Validation: NanoBRET assays confirm PPI stabilization in living cells.

Targeting Hot Regions for PPI Inhibition

Small molecules can be designed to disrupt PPI by targeting hot regions:

- Competitive Inhibition: Designing molecules that mimic key residues in the hot region.

- Allosteric Inhibition: Targeting residues adjacent to hot regions that are crucial for maintaining the cooperative network.

Predicting Cooperative vs. Competitive Interactions

Recent computational frameworks using hyperbolic embedding of protein interaction networks and Random Forest classifiers can distinguish between cooperative and competitive triplets (AUC = 0.88) [28]. This helps identify which PPIs are amenable to simultaneous targeting.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hot Region Studies

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function/Application | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| HotRegion Database [23] | Database | Provides hot region information, structural properties, and 3D visualization of interfaces | http://prism.ccbb.ku.edu.tr/hotregion |

| PPI-hotspotID Web Server [25] | Prediction Tool | Identifies PPI-hot spots using free protein structures | https://ppihotspotid.limlab.dnsalias.org/ |

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis Kit | Experimental Kit | Systematically mutate interface residues to alanine for energetic profiling | Commercial vendors |

| Interactome3D [28] | Database | Structurally annotated protein interactions for validation | http://interactome3d.irbbarcelona.org |

| Disulfide Tethering Fragments [24] | Chemical Library | Cysteine-reactive fragments for targeting PPI interfaces | Custom synthesis |

| NanoBRET Assay System [24] | Cellular Assay | Measures PPIs in living cells for compound validation | Commercial vendors |

The paradigm shift from studying individual hot spots to understanding clustered hot regions has significantly advanced our knowledge of protein-protein interactions. The clustered, cooperative nature of these residues has profound implications for drug discovery, particularly for designing small molecules that target PPIs. Molecular glues that stabilize native interactions represent a particularly promising avenue, especially for proteins with intrinsically disordered domains traditionally considered "undruggable."

Future research directions should focus on:

- Dynamic Characterization: Understanding the temporal dynamics of hot region formation and dissociation.

- Machine Learning Enhancements: Integrating AlphaFold-predicted structures with hot region prediction tools [25].

- Multi-Target Strategies: Designing compounds that simultaneously target multiple hot regions for enhanced specificity and efficacy.

As computational methods continue to improve and experimental techniques become more sophisticated, the systematic targeting of hot regions will likely play an increasingly important role in therapeutic development for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other conditions driven by dysregulated protein interactions.

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to virtually all cellular processes, including signal transduction, gene expression, and immune responses. The dysregulation of these interactions is implicated in numerous diseases, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [19]. However, the development of small-molecule drugs that effectively modulate PPIs has long been considered a formidable challenge. This difficulty primarily stems from the structural nature of PPI interfaces, which are typically large, flat, and lacking the deep, well-defined binding pockets commonly found on traditional enzyme targets [19] [29]. These characteristics limit the ability of small molecules to form specific, high-affinity interactions necessary for effective inhibition or stabilization.

Despite these challenges, the field has witnessed significant progress over the past two decades. Technological advances in structural biology, computational modeling, and screening methodologies have transformed PPIs from "undruggable" targets to increasingly feasible therapeutic opportunities [19]. Central to this progress has been the recognition that binding energy across PPI interfaces is not distributed uniformly but is concentrated at specific regions known as hot spots [19] [30]. These hot spots represent crucial footholds for drug discovery, providing localized regions where small molecules can achieve potent binding despite the extensive interface. This whitepaper examines the current methodologies, challenges, and strategic approaches for targeting PPI hot spots with small molecules, providing researchers with a technical framework for addressing this persistent druggability challenge.

The Structural and Energetic Landscape of PPI Interfaces

Defining Characteristics of PPI Hot Spots

Hot spots are defined as specific residues within a PPI interface that contribute disproportionately to the binding free energy. Experimentally, they are identified as residues whose mutation to alanine causes a significant decrease in binding free energy (typically ΔΔG ≥ 2 kcal/mol) [19] [25]. These regions are characterized by several key structural and physicochemical properties:

- Spatial Localization: Hot spots tend to cluster in tightly packed "hot regions" within the broader interface, rather than being randomly distributed [19].

- Amino Acid Composition: They are frequently enriched in specific residue types, particularly aromatic amino acids (tyrosine, tryptophan, phenylalanine) and arginine, which form strong van der Waals contacts, hydrogen bonds, and electrostatic interactions [19].

- Structural Organization: Unlike enzyme active sites, hot spots do not necessarily form deep pockets but can exist as shallow depressions or even relatively flat surfaces with specific topological features that can be exploited by small molecules [19].

The presence of these hot spots explains a fundamental paradox of PPIs: how a single protein surface can often interact with multiple structurally diverse partners. The clustered, energetically critical nature of hot spots allows for targeted intervention, as disrupting these focal points can effectively inhibit the entire interaction without requiring blockade of the entire interface [19] [30].

The Hydrophobic Effect and Its Role in PPIs

The hydrophobic effect represents a major driving force for PPI formation, with hot spot residues often containing a mix of hydrophobic and polar components [19]. This combination allows for both favorable desolvation energetics and specific hydrogen bonding interactions. The interfacial surface area of typical PPI hot spots ranges from 600-1000 Ų, significantly larger than traditional small-molecule binding sites but considerably smaller than complete PPI interfaces, which often exceed 1500-3000 Ų [19]. This size discrepancy highlights the potential for targeted intervention at these critical regions.

Methodological Approaches for Identifying and Targeting Hot Spots

Computational Prediction of Hot Spots

Computational methods have become indispensable tools for hot spot identification, dramatically reducing the experimental burden of characterizing PPI interfaces. Current approaches can be broadly categorized into sequence-based, structure-based, and hybrid methods:

Table 1: Computational Methods for Hot Spot Prediction

| Method Type | Representative Tools | Key Inputs | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based | PPI-hotspotID [25], FTMap [25], KFC2 [30] | Free or complex protein structure | Higher accuracy; Provides spatial localization | Limited by structural availability and quality |

| Sequence-Based | SPOTONE [25] | Protein sequence only | Applicable when structural data is unavailable | Lower accuracy; Limited structural insights |

| Homology-Based | Various [19] | Sequence of homologs with known interactions | Accurate for well-conserved families | Limited to proteins with characterized homologs |

| Machine Learning | Random Forests, SVMs [19] [25] | Multiple features (conservation, SASA, energy, etc.) | Integrates diverse data types; Improved performance | Requires large training datasets |

Recent advances in machine learning have significantly enhanced prediction accuracy. The PPI-hotspotID method, for instance, employs an ensemble of classifiers using only four residue features: evolutionary conservation, amino acid type, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) [25]. When validated on a dataset containing 414 experimentally known PPI-hot spots and 504 nonhot spots, PPI-hotspotID demonstrated substantially better performance (F1-score: 0.71) compared to FTMap (F1-score: 0.13) and SPOTONE (F1-score: 0.17) [25].

The integration of AlphaFold-Multimer for interface residue prediction with dedicated hot spot detection methods like PPI-hotspotID has shown promise for further improving prediction accuracy, especially for PPIs without experimentally determined complex structures [25].

Figure 1: Workflow for Hot Spot Identification and Targeting. This diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental pipeline for identifying PPI hot spots and developing small molecule modulators.

Experimental Validation of Hot Spots

Computational predictions require experimental validation to confirm biological significance and therapeutic relevance. Several established methodologies provide this essential validation:

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis: This remains the gold standard for experimental hot spot identification. The method involves systematically mutating interface residues to alanine and measuring the resulting changes in binding affinity using techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [19] [25]. Residues whose mutation causes a ≥ 2 kcal/mol reduction in binding free energy are classified as hot spots.

High-Throughput Mutational Approaches: Techniques such as deep mutational scanning combine library-based mutagenesis with next-generation sequencing to assess the functional impact of thousands of mutations in parallel, providing comprehensive maps of energetic contributions across PPI interfaces [19].

Biophysical Mapping: Methods like hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) and chemical cross-linking can identify regions of structural perturbation upon binding, indirectly highlighting critical interfacial residues.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Hot Spot Validation

| Technique | Key Measurements | Throughput | Information Gained | Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine Scanning | ΔΔG of binding | Low | Energetic contribution of specific residues | Protein production and purification |

| Deep Mutational Scanning | Functional impact of mutations | High | Comprehensive interface energetics | DNA library construction; NGS capability |

| HDX-MS | Deuterium uptake rates | Medium | Structural dynamics and binding interfaces | MS expertise; Specialized instrumentation |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Binary interaction strength | Medium-High | Functional consequences of mutations | Compatible bait/prey systems |

Strategic Frameworks for Small Molecule Discovery

Overcoming the "Flat Interface" Challenge

The absence of deep binding pockets at PPI interfaces necessitates specialized approaches for small molecule discovery. Successful strategies have included:

Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): This approach is particularly well-suited to PPI inhibition because smaller fragments (molecular weight < 250 Da) can bind to discontinuous hot spots that larger compounds cannot access [19]. The presence of aromatic-rich regions at many PPI interfaces makes them especially amenable to fragment binding [19]. Following initial fragment identification, structure-based optimization can then link multiple fragments or elaborate individual fragments into more potent inhibitors.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD): Leveraging high-resolution structural information from X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or computational models enables the rational design of compounds that complement the topology and chemical features of hot spot regions [19]. The dramatic improvements in protein structure prediction through AlphaFold and RosettaFold have significantly expanded the potential for SBDD against PPIs with unknown experimental structures [19].

Targeted Library Design: Screening libraries specifically enriched for "PPI-privileged" scaffolds—compounds with characteristics known to favor PPI engagement—can improve hit rates. These characteristics include semi-rigid structures, specific stereochemistry, and balanced hydrophobicity [19] [29].

Advanced Modalities for Intractable PPIs

For particularly challenging PPIs that remain resistant to conventional small molecule approaches, several advanced modalities have emerged:

Stabilizers vs. Inhibitors: While most PPI drug discovery focuses on inhibitors, there is growing interest in developing small molecule stabilizers that enhance native PPIs [19]. This approach is particularly relevant for diseases caused by loss-of-function mutations or decreased complex formation. However, stabilizer development presents unique challenges, as these compounds often act allosterically and their binding sites may not be readily apparent in static structures [19].

Covalent Strategies: Targeted covalent modifiers can achieve enhanced potency against challenging PPIs by forming irreversible or slowly reversible bonds with nucleophilic residues (e.g., cysteine) within hot spot regions [29].

Targeted Protein Degradation: Technologies such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) offer an alternative strategy—rather than inhibiting the PPI interface directly, these molecules recruit the protein to E3 ubiquitin ligases, leading to its degradation [29]. This approach effectively modulates PPIs by reducing the cellular concentration of one interaction partner.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Method | Function in PPI Research | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-hotspotID [25] | Computational hot spot prediction from free protein structures | Prioritizing residues for mutagenesis or targeting | Requires protein structure; Web server available |

| AlphaFold-Multimer [25] | Prediction of protein complex structures and interface residues | Generating structural models when experimental structures are unavailable | Accuracy varies; Best for complexes with homologs |

| FTMap Server [25] | Identification of binding hot spots via computational mapping | Detecting potential small molecule binding sites | Can be used in PPI mode for interface analysis |

| Fragment Libraries [19] | Collections of low molecular weight compounds for FBDD | Initial screening against challenging PPI targets | Typically 500-1500 compounds; High quality essential |

| Alanine Scanning Kits | Experimental validation of computational hot spot predictions | Measuring energetic contributions of specific residues | Requires protein expression and purification capabilities |

| Cryo-EM Services [19] | High-resolution structure determination of protein complexes | SBDD for PPIs resistant to crystallization | Increasingly accessible; High startup costs |

| Anticancer agent 133 | Anticancer agent 133, MF:C24H19Cl3N5ORh, MW:602.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tempol-d17,15N | Tempol-d17,15N|Deuterium-Labeled SOD Mimetic | Bench Chemicals |

The perception of protein-protein interactions as "undruggable" targets has been fundamentally transformed by advances in our understanding of hot spot biology and the development of specialized technologies for their exploitation. While the challenges posed by large, flat interface surfaces remain substantial, integrated approaches combining computational prediction, experimental validation, and structure-based design have demonstrated repeated success. The continued refinement of AI-driven structure prediction, fragment-based screening, and targeted degradation approaches promises to further expand the druggable PPI landscape. By focusing therapeutic discovery efforts on the critical hot spot regions that dominate binding energy, researchers can develop effective small-molecule modulators for this important class of biological targets, opening new avenues for treating complex diseases.

From Prediction to Design: Computational and Experimental Strategies for Hot Spot Engagement

Computational Alanine Scanning (CAS) has emerged as a powerful in silico technique for mapping the energetic landscape of protein-protein interfaces, enabling rapid identification of "hot spot" residues critical for binding affinity. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of CAS methodologies, validation benchmarks, and implementation workflows, with particular emphasis on its application in small molecule targeting research. By leveraging computational efficiency that far surpasses experimental alanine scanning, CAS offers researchers the capability to perform rapid mutational analysis across entire protein interfaces, delivering critical insights for rational drug design targeting protein-protein interactions (PPIs). This review synthesizes current methodologies, accuracy assessments, and practical protocols to equip researchers with the necessary framework for implementing CAS in structural biology and drug discovery pipelines.

Historical Context and Biological Rationale