UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomic Profiling in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia: Biomarker Discovery, Pathways, and Clinical Translation

The co-occurrence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) presents a significant clinical challenge, with growing evidence pointing to shared underlying disturbances in lipid metabolism.

UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomic Profiling in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia: Biomarker Discovery, Pathways, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

The co-occurrence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) presents a significant clinical challenge, with growing evidence pointing to shared underlying disturbances in lipid metabolism. This article explores the application of Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) for comprehensive lipidomic profiling to unravel the complex metabolic interplay in this comorbidity. We detail the foundational discoveries of specific lipid biomarkers and perturbed pathways, such as glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism. The discussion covers methodological best practices for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis, common troubleshooting scenarios, and the critical process of analytical and clinical validation. By integrating findings from recent studies, this review highlights the translational potential of lipidomics in developing diagnostic tools and personalized therapeutic strategies for patients with concurrent diabetes and hyperuricemia, ultimately aiming to improve risk prediction and clinical outcomes.

Unraveling the Lipid Landscape: Core Discoveries in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Clinical and Epidemiological Intersection

The comorbidity of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and Hyperuricemia (HUA) represents a significant and growing challenge in metabolic medicine. Epidemiologically, these conditions are deeply intertwined. Hyperuricemia, defined as a serum uric acid (SUA) level exceeding 7.0 mg/dL in men or 6.0 mg/dL in women, ranks as the second most prevalent metabolic disorder after diabetes itself [1]. In China, the prevalence of HUA in the general population has been reported at 17.7% and can be as high as 21.24% among diabetic patients [2] [1]. This association is not merely coincidental but reflects shared pathophysiological underpinnings, as research indicates that for every 1 mg/dL increase in serum uric acid, the risk of developing diabetes increases by 17% [2].

The relationship between these conditions exhibits complex, sometimes paradoxical characteristics. A large-scale study from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that hyperuricemia was associated with a decreased prevalence of diabetes mellitus in men (OR: 0.44) while simultaneously correlating with an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in both sexes [3]. This dual nature of uric acid—acting as both an antioxidant and a pro-oxidant depending on context—complicates the clinical picture and necessitates deeper investigation into the underlying mechanisms [4].

Table 1: Global Prevalence of Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Condition | Overall Prevalence | Prevalence in Diabetic Populations | Key Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Mellitus (DM) | 10.5% globally (536.6 million) [2] | - | Fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or random blood glucose >11.0 mmol/L [2] |

| Hyperuricemia (HUA) | 13.3%-17.7% in China [2] [5] | 21.24% in China [1] | SUA >420 μmol/L in men, >360 μmol/L in women [2] |

| DM-HUA Comorbidity | - | 20.70% in North America [1] | Co-occurrence of both conditions |

Lipidomic Alterations in Comorbid Diabetes-Hyperuricemia

Advanced lipidomic technologies, particularly UHPLC-MS/MS, have revealed profound disruptions in lipid metabolism in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia. A 2025 study employing untargeted lipidomic analysis identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses in patient plasma, with 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in the diabetes-hyperuricemia (DH) group compared to healthy controls [2]. The most prominent changes included significant upregulation of 13 triglycerides (TGs), 10 phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and 7 phosphatidylcholines (PCs), while one phosphatidylinositol (PI) was notably downregulated [2].

These alterations are not merely quantitative but represent fundamental shifts in lipid homeostasis. A separate multi-omics study on hyperuricemia patients confirmed 33 significantly upregulated lipid metabolites involved in five key metabolic pathways: arachidonic acid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis, and alpha-linolenic acid metabolism [6]. The convergence of findings across studies highlights the centrality of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism in this comorbidity.

Table 2: Key Altered Lipid Classes in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Comorbidity

| Lipid Class | Change in DH Patients | Specific Examples | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | Significant upregulation (13 TGs) [2] | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) [2] | Energy storage, cardiovascular risk indicators |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | Significant upregulation (10 PEs) [2] | PE(18:0/20:4) [2] | Membrane structure, cell signaling |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | Significant upregulation (7 PCs) [2] | PC(36:1) [2] | Membrane integrity, lipoprotein assembly |

| Sphingomyelins (SMs) | Altered in T2DM with dyslipidemia [7] | SM(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/16:1) [7] | Membrane microdomains, signaling pathways |

| Ceramides (Cer) | Altered in T2DM with dyslipidemia [7] | Cer(d18:1/24:0) [7] | Insulin resistance, apoptosis induction |

UHPLC-MS/MS Methodologies for Lipidomic Profiling

Sample Preparation and Extraction

The integrity of lipidomic analysis begins with meticulous sample preparation. In standard protocols, 100 μL of plasma is mixed with 200 μL of 4°C water and 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol before adding 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) for lipid extraction [2]. The mixture undergoes 20 minutes of sonication in a low-temperature water bath and 30 minutes of standing at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C [2]. The upper organic phase is collected and dried under nitrogen before being reconstituted for analysis. Quality control samples should be prepared by mixing equal volumes of all sample extracts and randomly inserted into the analysis sequence to ensure analytical consistency [2].

Chromatographic Separation

For chromatographic separation, the methodology typically employs a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) maintained at 45°C [2] [6]. The mobile phase consists of: Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-water solution, and Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-isopropanol solution [2]. The gradient elution program generally starts at 30% mobile phase B (0-2 minutes), increases to 100% B (2-25 minutes), and is maintained before re-equilibration [6]. A constant flow rate of 300 μL/min with a 3 μL injection volume provides optimal separation conditions [6].

Mass Spectrometric Detection

The mass spectrometric analysis employs Q-Exactive series Orbitrap mass spectrometers or similar high-resolution instruments capable of accurate mass measurement [6] [8]. Typical source conditions include: heater temperature: 300°C, sheath gas flow rate: 45 arb, auxiliary gas flow rate: 15 arb, spray voltage: 3.0 kV (positive) or 2.5 kV (negative), and capillary temperature: 350°C [6]. Data acquisition involves full scans at a resolution of 70,000 at m/z 200 for MS1, with data-dependent MS2 scans at a resolution of 17,500 for top N precursors [6]. This configuration enables simultaneous identification and quantification of hundreds of lipid species across multiple classes.

Disrupted Metabolic Pathways and Signaling Mechanisms

The intersection of diabetes and hyperuricemia manifests in distinct metabolic pathway disruptions. Multivariate analyses reveal that glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) represent the most significantly perturbed pathways in diabetes-hyperuricemia patients [2]. These pathways are central to membrane integrity, signaling transduction, and energy homeostasis. The comparison of diabetes-hyperuricemia versus diabetes-alone groups identified 12 differential lipids also predominantly enriched in these same core pathways, underscoring their fundamental role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [2].

Beyond glycerophospholipid disruptions, research has highlighted the importance of sphingolipid metabolism, particularly in diabetes with dyslipidemia [7]. Specific ceramides and sphingomyelins—including Cer(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/24:0), SM(d18:1/16:1), SM(d18:1/24:1), and SM(d18:2/24:1)—have been identified as crucial biomarkers strongly correlated with clinical parameters of glucose and lipid metabolism [7]. These sphingolipids participate in insulin resistance mechanisms through protein phosphatase inhibition and inflammatory pathway activation.

The immune-metabolic cross-talk in this comorbidity involves significant alterations in inflammatory mediators. Studies measuring immune factors in hyperuricemia patients found that IL-10, CPT1, IL-6, SEP1, TGF-β1, Glu, TNF-α, and LD were associated with glycerophospholipid metabolism disruptions [6]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) confirmed significant differences in CPT1, TGF-β1, Glu, and LD between hyperuricemia patients and healthy controls across different ethnicities [6], highlighting the intricate connection between lipid metabolism and immune responses in this condition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) [2] | Lipid separation by hydrophobicity |

| Extraction Solvent | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [2] [6] | Lipid extraction from biological matrices |

| Mass Spectrometry Reference | Leucine-enkephalin [7] | Mass calibration and accuracy maintenance |

| Lipid Standards | LysoPC(18:0/0:0) and LysoPC(18:1/0:0) from Avanti Polar Lipids [7] | Quantification standardization and quality control |

| Mobile Phase Additive | 10 mM ammonium formate [2] [7] | Enhanced ionization efficiency in MS |

| Chromatography Solvents | MS-grade acetonitrile, methanol, isopropanol [7] | Mobile phase preparation for UHPLC separation |

| Data Processing Software | Compound Discoverer, LipidSearch, MS-DIAL [9] [8] | Lipid identification, quantification, and statistical analysis |

| Lipid Database | LIPID MAPS, LipidBlast [8] | Structural identification and annotation of lipid species |

| Phenethyl acetate | Phenethyl Acetate CAS 103-45-7 - Research Chemical | High-purity Phenethyl acetate for research. Study its role as an insect odorant receptor agonist and its applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Dimethylamine-SPDB | Dimethylamine-SPDB, CAS:1193111-73-7, MF:C15H19N3O4S2, MW:369.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Perspectives and Future Directions

The investigation of lipid metabolism in diabetes-hyperuricemia comorbidity through UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomics has revealed profound alterations in glycerophospholipid, glycerolipid, and sphingolipid pathways. These discoveries provide not only mechanistic insights but also potential biomarkers for early detection and risk stratification. The identified lipid species—particularly ceramides, sphingomyelins, and specific phospholipids—offer promising targets for therapeutic intervention and personalized treatment approaches.

Future research directions should prioritize the validation of these lipid biomarkers in independent, multi-center cohorts to establish standardized clinical applications. Additionally, the integration of lipidomics with other omics technologies—including genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the systemic metabolic disruptions in this comorbidity. As lipidomic methodologies continue to advance, particularly with the incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data analysis, the translation of these findings from research laboratories to clinical practice represents the next frontier in managing this complex metabolic comorbidity.

The comorbidity of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) represents a significant clinical challenge, driven by intertwined pathophysiological mechanisms including insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and systemic metabolic dysregulation [10]. Lipidomics, a branch of metabolomics, has emerged as a powerful tool to characterize the specific lipid disturbances underlying this complex relationship. Advanced analytical techniques, particularly UHPLC-MS/MS, have enabled researchers to identify distinct lipidomic signatures associated with the progression from diabetes to diabetes with hyperuricemia (DH) [2]. This technical review synthesizes current evidence on the key lipid classes—triglycerides, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids—that are significantly altered in this comorbidity, providing a foundation for biomarker discovery and novel therapeutic strategies.

Key Lipid Classes and Their Alterations

Comprehensive lipidomic profiling reveals consistent and significant disturbances in three major lipid classes in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia. The tables below summarize the specific lipid species and their directional changes.

Table 1: Triglyceride and Glycerophospholipid Species Altered in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

| Lipid Class | Specific Species | Change in DH vs. Control | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significantly Upregulated [2] | Marker of insulin resistance and central component of dyslipidemia. |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significantly Upregulated [2] | Altered membrane permeability and fluidity. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significantly Upregulated [2] | Disruption of cell membrane integrity and signaling. |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not Specified | Significantly Downregulated [2] | Perturbation of intracellular signal transduction. |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine Plasmanyls | Multiple | Downregulated in HUA/Gout [11] | Potential anti-inflammatory role; reduction may promote inflammation. |

Table 2: Sphingolipid Species and Associated Enzymes in Metabolic Disease

| Sphingolipid Component | Specific Species / Enzyme | Change / Role in Diabetes/HUA | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramide | C24:0 Ceramide | Most abundant circulating species [12] | Promotes insulin resistance and apoptotic signaling. |

| Sphingomyelin | C16:0 Sphingomyelin | Most abundant sphingolipid in lipoproteins [12] | Alters membrane properties and lipoprotein function. |

| Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) | Various | Carried by HDL and albumin [12] | Generally promotes cell proliferation; balance with ceramide is crucial. |

| Serine Palmitoyltransferase (SPT) | SPTLC1, SPTLC2, SPTLC3 | Upregulated by inflammatory cytokines and fatty acids [13] | Rate-limiting enzyme in de novo synthesis; increased flux into sphingolipid pathway. |

Impacted Metabolic Pathways

Multivariate and enrichment analyses of lipidomic data consistently pinpoint specific metabolic pathways that are most significantly perturbed in the DH state.

Table 3: Significantly Perturbed Metabolic Pathways in Combined Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

| Metabolic Pathway | Impact Value (from MetaboAnalyst) | Key Lipid Classes Involved | Pathophysiological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipid Metabolism | 0.199 (Most significant) [2] | PCs, PEs, PIs, LPCs | Central to membrane biology, cell signaling, and inflammation. |

| Glycerolipid Metabolism | 0.014 [2] | Triglycerides, Diglycerides | Core pathway in energy storage and insulin resistance. |

| Arachidonic Acid Metabolism | Not Specified | PE(18:0/20:4) and other esters [14] | Generation of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids. |

| Sphingolipid Metabolism | Not Specified | Ceramide, Sphingomyelin, S1P [12] [13] | Regulation of insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and cell fate. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

UHPLC-MS/MS Based Plasma Untargeted Lipidomics

The following protocol is adapted from the comprehensive methodology used in recent studies to identify lipid alterations in patient cohorts [2] [11].

Sample Collection and Pre-processing

- Blood Collection: Collect ~5 mL of fasting venous blood into sodium heparin or EDTA tubes.

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge at 3,000 rpm (approximately 1,500-2,000 g) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Aliquot 0.2 mL of the upper plasma layer into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes.

- Pooled QC: Create quality control (QC) samples by combining equal volumes of plasma from all experimental groups. Store all samples at -80°C.

- Lipid Extraction (Monophasic):

- Thaw plasma samples on ice.

- Pipette 100 μL of plasma into a 1.5 mL tube.

- Add 200 μL of ice-cold water and vortex.

- Add 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol and vortex.

- Add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and vortex vigorously.

- Sonicate for 20 minutes in a low-temperature water bath.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C.

- Transfer the upper organic phase to a new tube.

- Dry under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in 200 μL of 90% isopropanol/acetonitrile.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C prior to MS analysis.

UHPLC-MS/MS Instrumentation and Conditions

- Chromatography:

- System: Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (e.g., ExionLC, SCIEX or equivalent).

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) or a BEH C8 column for broader lipid coverage.

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water (e.g., 60:40, v/v).

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol (e.g., 10:90, v/v).

- Gradient: Typically from 30% B to 100% B over 20-25 minutes, followed by re-equilibration.

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min.

- Column Temperature: 45°C.

- Injection Volume: 3 μL.

- Mass Spectrometry:

- System: Tandem Mass Spectrometer (e.g., QTRAP 6500+ or Q-Exactive Plus).

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), positive and negative ion modes.

- Source Parameters (Positive Mode): Sheath Gas Flow: 45 arb, Aux Gas Flow: 15 arb, Spray Voltage: 3.0 kV, Capillary Temperature: 350°C.

- Source Parameters (Negative Mode): Sheath Gas Flow: 45 arb, Aux Gas Flow: 15 arb, Spray Voltage: 2.5 kV, Capillary Temperature: 350°C.

- Scan Modes: Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) or Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH) for untargeted analysis. MS1 full scan (e.g., m/z 200-1800) followed by MS2 scans of the top 10 most intense ions.

ELISA for Immune and Metabolic Biomarkers

To correlate lipidomic findings with inflammatory and metabolic status, key biomarkers can be quantified [14].

- Analytes: Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-10 (IL-10), Transforming Growth Factor-β1 (TGF-β1), Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT1), Selenoprotein 1 (SEP1), Glucose (Glu), Lactic Acid (LD).

- Protocol:

- Coat ELISA plate with capture antibody.

- Block plates with a protein-based buffer (e.g., 1% BSA in PBS).

- Add standards and prediluted serum/plasma samples.

- Incubate, then wash to remove unbound material.

- Add detection antibody conjugated to an enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase, HRP).

- Incubate and wash.

- Add enzyme substrate to develop color.

- Measure absorbance using a microplate reader (e.g., VersaMax).

- Calculate concentrations using a standard curve generated from known standards.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

Sphingolipid Metabolism in Insulin Resistance

The following diagram illustrates the key pathways of sphingolipid metabolism and their involvement in promoting insulin resistance, a core defect in the diabetes-hyperuricemia comorbidity.

Diagram Title: Sphingolipid Metabolism in Insulin Resistance

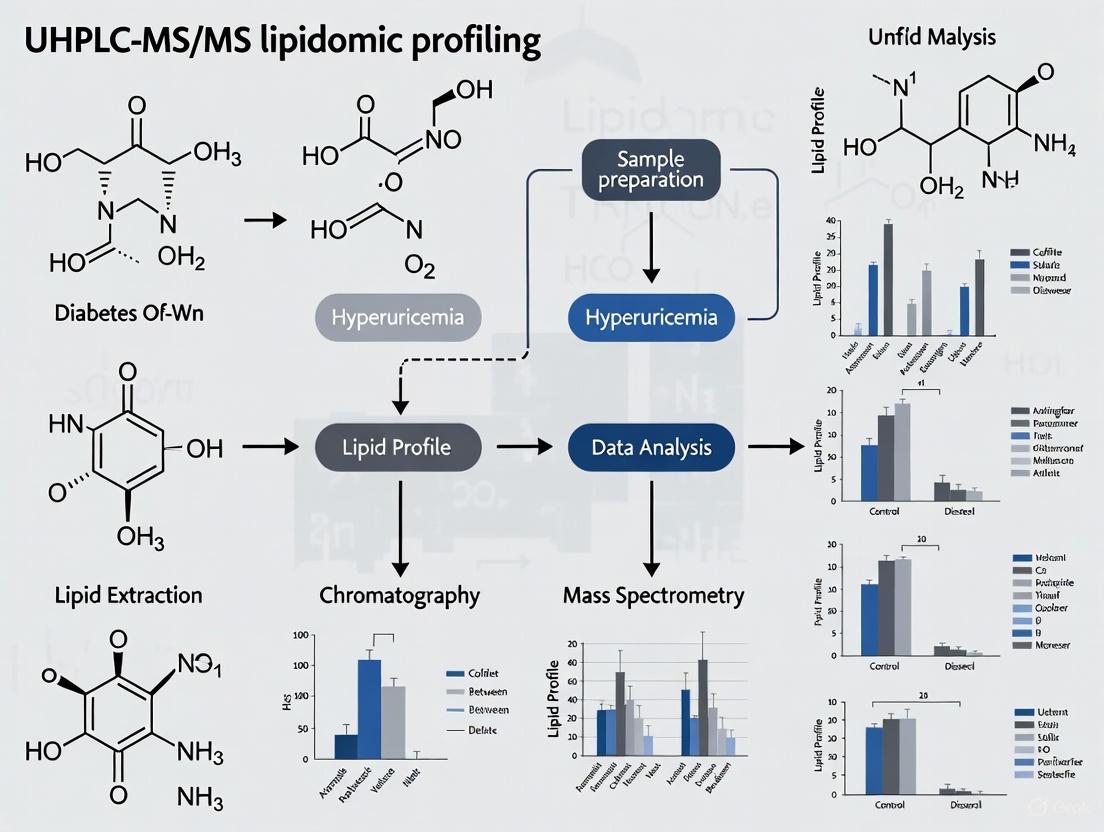

UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics Workflow

This diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow for a plasma untargeted lipidomics study, from sample collection to data analysis.

Diagram Title: UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the described protocols requires the following key reagents and instruments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipidomics Studies

| Category / Item | Specific Example / Specification | Critical Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Column | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1x100mm, 1.7µm) | High-resolution separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to MS detection. |

| Internal Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard; Deuterated Ceramide (d18:1-d7/15:0) | Correction for extraction efficiency and instrument variability; enables semi-quantitation. |

| Mass Spectrometer | QTRAP 6500+; Q-Exactive Plus | High-sensitivity detection and structural characterization of lipids via MS/MS. |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), LC-MS Grade Isopropanol | Efficient, reproducible liquid-liquid extraction of a broad range of lipid classes from plasma. |

| Mobile Phase Additives | 10 mM Ammonium Formate, LC-MS Grade | Enhances ionization efficiency in ESI and helps control analyte adduct formation. |

| ELISA Kits | Commercial Kits for TNF-α, IL-6, CPT1, etc. | Multiplexed, specific quantification of protein biomarkers linked to lipid metabolic dysregulation. |

| Clocortolone | Clocortolone, CAS:4828-27-7, MF:C22H28ClFO4, MW:410.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Thiol-PEG12-acid | Thiol-PEG12-acid, CAS:1032347-93-5; 2211174-73-9, MF:C27H54O14S, MW:634.78 | Chemical Reagent |

The application of advanced UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomics has definitively identified triglycerides, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids as the key lipid classes dysregulated in the complex interplay between diabetes and hyperuricemia. The consistent upregulation of specific TGs, PEs, and PCs, coupled with disturbances in glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism, provides a molecular rationale for the exacerbated insulin resistance and inflammatory state observed in comorbid patients. These findings not only illuminate the pathophysiological mechanisms but also establish a foundation for targeting these lipid pathways for future diagnostic and therapeutic innovations. The standardized protocols and tools outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to further validate and build upon these critical findings.

In the landscape of metabolic disease research, lipidomics has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying disease pathophysiology. The dysregulation of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism represents a critical metabolic axis in diabetes and its related complications, including hyperuricemia. These lipid classes are not only fundamental structural components of cellular membranes but also play dynamic roles in cellular signaling, energy storage, and metabolic homeostasis. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has enabled researchers to characterize these alterations with unprecedented specificity and sensitivity, revealing complex lipid metabolic networks that are perturbed in disease states. This technical guide examines the core aspects of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid dysregulation within the context of diabetes and hyperuricemia, providing researchers with comprehensive methodological frameworks, analytical approaches, and pathophysiological insights to advance investigation in this evolving field.

Lipidomic Alterations in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Clinical Lipidomic Profiling

Clinical studies utilizing UHPLC-MS/MS platforms have revealed consistent patterns of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid dysregulation in patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH). A recent investigation comparing DH patients, those with diabetes alone (DM), and healthy controls identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with multivariate analyses demonstrating significant separation among these groups [2].

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Species in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

| Lipid Category | Lipid Subclass | Specific Lipid Species | Regulation Trend | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) | PE(18:0/20:4) | Upregulated | Membrane fluidity, signaling precursors |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PC) | PC(36:1) | Upregulated | Membrane integrity, choline metabolism | |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LysoPC) | Multiple species | Altered | Inflammatory modulation | |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not specified | Downregulated | Insulin signaling, cellular trafficking | |

| Glycerolipids | Triglycerides (TG) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) | Upregulated | Energy storage, lipid accumulation |

| Diacylglycerols (DG) | Multiple species | Upregulated | Insulin resistance, signaling molecule |

The pathway analysis of these altered lipids revealed enrichment in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed in DH patients [2]. Notably, the comparison between DH and DM groups identified 12 differential lipids that were similarly enriched in these core pathways, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes.

Systemic Metabolic Implications

The dysregulation of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism extends beyond diabetes with hyperuricemia to encompass various diabetic complications. In diabetic cardiomyopathy, increased fatty acid uptake and altered glycerophospholipid composition contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and impaired cardiac function [15]. Similarly, lipidomic profiling of serum from patients with diabetic retinopathy has revealed distinctive glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid signatures that can distinguish between patients without retinopathy and those with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, offering potential diagnostic biomarkers [16].

The systemic nature of these lipid metabolic alterations is further evidenced by lipid traffic analysis studies in diabetic mouse models, which have shown that the spatial distribution of triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and phosphatidylinositols (PIs) is altered throughout the biological network, indicating fundamental changes in the systemic control of lipid metabolism [17].

UHPLC-MS/MS Methodologies for Lipidomic Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for reliable lipidomic profiling. For plasma/serum analysis, the following protocol has been successfully employed in diabetes hyperuricemia research:

- Sample Collection: Collect fasting blood samples (5 mL) in appropriate vacuum tubes and centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma [2].

- Plasma Storage: Aliquot 0.2 mL of the upper plasma layer into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes and store at -80°C until analysis [2].

- Lipid Extraction: Thaw samples on ice and vortex. For 100 μL of plasma, add 200 μL of 4°C water followed by 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol. After mixing, add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) and sonicate in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes [2].

- Phase Separation: Allow the mixture to stand at room temperature for 30 minutes, then centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C. Collect the upper organic phase and dry under a stream of nitrogen gas [2].

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in 100 μL of isopropanol for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis [2].

For tissue-specific lipidomics, additional homogenization steps are required prior to lipid extraction. The MTBE extraction method has demonstrated excellent recovery across multiple lipid classes and is widely adopted in lipidomics research.

UHPLC-MS/MS Instrumental Configuration

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm length, 1.7 μm particle size) [2] or Kinetex C18 (2.6 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) [16]

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water [2]

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/isopropanol [2]

- Gradient: Optimized linear gradients typically ranging from 60-90% mobile phase B over 15-25 minutes

- Temperature: Column compartment maintained at 45-55°C

- Injection Volume: 1-5 μL depending on sample concentration

Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative modes

- Ion Spray Voltage: +5,200 V (positive), -4,500 V (negative) [16]

- Ion Source Temperature: 350°C [16]

- Detection Mode: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for targeted analysis; full scan for untargeted approaches

- Collision Energies: Optimized for specific lipid classes based on precursor and product ions

The experimental workflow for UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic profiling in diabetes-hyperuricemia research encompasses sample collection, preparation, chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric detection, and data analysis, with specific methodology tailored to the biological question.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Raw mass spectrometry data processing typically involves:

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Using platforms like SCIEX OS or open-source tools such as XCMS

- Lipid Identification: Based on retention time, precursor mass, and fragmentation patterns compared to standards

- Quantification: Using internal standards for semi-quantitative or absolute quantification

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify group separations

- Differential Analysis: Student's t-test and fold-change calculations to determine significantly altered lipids

- Pathway Analysis: Using platforms like MetaboAnalyst 5.0 to identify enriched metabolic pathways

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Glycerophospholipid Metabolism in Insulin Signaling

Glycerophospholipids, particularly phosphatidylinositols (PIs) and their phosphorylated derivatives, play fundamental roles in insulin signal transduction. In diabetic states, alterations in glycerophospholipid metabolism disrupt membrane fluidity, receptor function, and downstream signaling cascades. Research has demonstrated that specific PI species are significantly altered in diabetic models, with structural PIs (e.g., PI(36:1), PI(38:6)) showing distinct distribution patterns that may affect membrane physical properties and signaling functionality [17].

The interconnection between glycerophospholipid metabolism and insulin signaling involves multiple enzymes and lipid species that are dysregulated in diabetes, creating a pathological feedback loop that exacerbates insulin resistance.

Glycerolipid Dynamics and Lipid Droplet Pathology

Glycerolipids, particularly diacylglycerols (DGs) and triglycerides (TGs), are centrally implicated in the lipotoxicity that characterizes diabetes and its complications. DG accumulation has been identified as an early event in diabetic progression, with studies demonstrating its upregulation even during pre-symptomatic phases [18]. DGs activate protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, which in turn phosphorylate insulin receptor substrates on inhibitory sites, blunting insulin signaling and promoting resistance [15].

In the context of hyperuricemia, uric acid has been shown to exacerbate glycerolipid dysregulation, promoting increased synthesis of TGs and altering the composition of lipid droplets (LDs) [19]. LDs are dynamic organelles that store neutral lipids, and their proper turnover is essential for maintaining lipid homeostasis. In diabetic states, LD dynamics become dysregulated, leading to ectopic lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissues such as the pancreas, liver, heart, and kidneys, contributing to cellular dysfunction and apoptosis [19].

Table 2: Lipid Droplet Dynamics in Diabetic Complications

| Tissue/Organ | LD Alteration | Functional Consequence | Molecular Mediators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic β-cells | Increased LD accumulation | Impaired insulin secretion | PLIN2, PLIN5, ATGL |

| Liver | Excessive LD storage | Hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance | PNPLA3, CGI-58 |

| Heart | Cardiac lipid accumulation | Diabetic cardiomyopathy | CD36, PPARα |

| Kidney | Glomerular LD deposition | Diabetic nephropathy | ROS, ER stress |

| Retina | Altered retinal lipid metabolism | Diabetic retinopathy | DAG, PKC |

The interplay between glycerolipid metabolism and LD dynamics is regulated by numerous factors, including perilipin proteins (PLIN1-5), lipases (ATGL, HSL, MGL), and autophagy pathways. Therapeutic strategies that target LD dynamics are emerging as promising approaches for managing diabetes and its complications [19].

Advanced Research Applications

Spatial Lipidomics in Metabolic Research

Recent advances in mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) have enabled spatial resolution of lipid distributions within tissues, providing novel insights into region-specific lipid metabolic alterations in diabetes. Spatial-temporal lipidomics in mouse models of disease has revealed distinct lipidomic differences between various brain regions, with the thalamus exhibiting more significant lipid changes than the hippocampus in Alzheimer's disease models, highlighting the potential for similar approaches in diabetes research [18]. These techniques can be adapted to investigate pancreatic islets, liver lobules, and renal compartments in diabetes models, offering unprecedented resolution of metabolic zonation.

Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Lipidomic profiling has identified numerous potential biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of diabetes progression and complications. For diabetic retinopathy, a four-lipid combination diagnostic model (including TAG58:2-FA18:1) has demonstrated excellent predictive ability for distinguishing between patients without retinopathy and those with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy [16]. Similarly, in newly diagnosed T2DM patients with dyslipidemia, ceramide (Cer(d18:1/24:0)) and sphingomyelin (SM(d18:1/24:0)) have emerged as promising biomarkers strongly correlated with clinical parameters [20].

The biomarker discovery and validation pipeline involves multiple stages from initial discovery to clinical implementation, with rigorous statistical evaluation at each step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Lipidomic Studies in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column | Lipid separation |

| Kinetex C18 column | Alternative separation column | |

| Ammonium formate | Mobile phase additive | |

| Acetonitrile, isopropanol, methanol | HPLC-grade solvents | |

| Sample Preparation | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction solvent |

| Internal standards: deuterated lipids | Quantification standardization | |

| Solid-phase extraction cartridges | Lipid cleanup and fractionation | |

| Mass Spectrometry | Reference standard lipid mixtures | Method development and calibration |

| Instrument calibration solutions | Mass accuracy maintenance | |

| Biological Reagents | CD36 antibodies | Fatty acid transporter studies |

| PPARα/γ agonists and antagonists | Pathway modulation | |

| Lipoprotein lipase inhibitors | Glycerolipid metabolism studies | |

| Data Analysis | LipidSearch Software | Lipid identification and quantification |

| MetaboAnalyst | Pathway analysis and visualization | |

| SIMCA-P | Multivariate statistical analysis | |

| Galanganone B | Galanganone B, MF:C34H40O6, MW:544.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anticancer agent 189 | Anticancer agent 189, MF:C42H56N4O10, MW:776.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comprehensive characterization of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism through UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic profiling has fundamentally advanced our understanding of diabetes pathophysiology and its intersection with hyperuricemia. The intricate interplay between these lipid classes contributes significantly to insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, and the development of microvascular complications. The methodological frameworks outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with robust tools for investigating these metabolic pathways, while the identified lipid signatures and biomarkers offer potential targets for therapeutic intervention and early diagnosis. As lipidomic technologies continue to evolve, particularly with advancements in spatial resolution and single-cell analysis, our ability to decipher the complex metabolic networks underlying diabetes and hyperuricemia will undoubtedly expand, paving the way for more personalized and effective treatment strategies.

1. Introduction Lipidomic profiling via UHPLC-MS/MS is a cornerstone of modern metabolic disease research, providing a high-resolution snapshot of lipid dysregulation. In the context of diabetes and hyperuricemia, specific lipid species have emerged as critical biomarkers and potential mechanistic players. This guide details the analytical and biological significance of three key lipids: Triacylglycerol TG(16:0/18:1/18:2), Ceramide Cer(d18:1/24:0), and Sphingomyelin SM(d18:1/24:0), within this comorbid pathological framework.

2. Quantitative Lipid Biomarker Data in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Dysregulated lipid levels are a hallmark of insulin resistance and hyperuricemia. The following table summarizes typical quantitative changes observed in patient serum/plasma studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Changes of Specific Lipid Biomarkers in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Cohorts

| Lipid Biomarker | Full Name | Typical Change vs. Control | Approximate Fold-Change (Range) | Proposed Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) | Triacylglycerol (Palmitic acid/Oleic acid/Linoleic acid) | ↑ Increased | 1.5 - 2.8 | Indicator of hepatic steatosis, impaired β-oxidation, and general lipotoxicity. |

| Cer(d18:1/24:0) | Ceramide (Sphingosine d18:1/Lignoceric acid) | ↓ Decreased | 0.4 - 0.7 | Loss of this longer-chain, less toxic ceramide may disrupt ceramide saturation balance, promoting insulin resistance. |

| SM(d18:1/24:0) | Sphingomyelin (Sphingosine d18:1/Lignoceric acid) | ↑ Increased | 1.3 - 2.0 | May reflect compensatory sphingomyelin synthesis or altered membrane microdomain composition in response to metabolic stress. |

3. Experimental Protocol: UHPLC-MS/MS Lipid Extraction and Profiling The following is a standardized protocol for lipidomic analysis from plasma/serum samples.

Materials:

- Biological Sample: Human plasma or serum (e.g., 10 µL aliquot).

- Extraction Solvent: Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE).

- Internal Standards: A mixture of stable isotope-labeled lipids (e.g., TG(16:0/18:1/18:2)-d5, Cer(d18:1/17:0), SM(d18:1/12:0)-d3).

- LC-MS Grade Solvents: Methanol, Water, Isopropanol, Acetonitrile, Ammonium Formate.

Procedure:

- Protein Precipitation & Lipid Extraction:

- To 10 µL of plasma in a glass vial, add 20 µL of internal standard mixture in methanol.

- Vortex for 10 seconds and incubate on ice for 10 minutes.

- Add 300 µL of MTBE and 100 µL of methanol.

- Sonicate for 15 minutes in an ice-cold water bath.

- Add 100 µL of LC-MS grade water to induce phase separation.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 10°C.

- Collect the upper organic (MTBE) layer into a new vial.

- Evaporate the solvent to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen.

- Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in 100 µL of a 9:1 (v/v) isopropanol:acetonitrile mixture.

- UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography:

- Column: C8 or C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm).

- Mobile Phase A: Acetonitrile/Water (60:40) with 10 mM Ammonium Formate.

- Mobile Phase B: Isopropanol/Acetonitrile (90:10) with 10 mM Ammonium Formate.

- Gradient: 30% B to 100% B over 15-20 minutes, hold at 100% B for 5 minutes.

- Flow Rate: 0.4 mL/min, Column Temp: 55°C.

- Mass Spectrometry:

- Ionization: Heated Electrospray Ionization (H-ESI) in positive and negative mode.

- Scan Mode: Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) or Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM).

- Source Parameters: Spray Voltage: 3.5 kV (pos), 2.8 kV (neg); Vaporizer Temp: 300°C; Sheath Gas: 40 arb; Aux Gas: 15 arb.

- Targeted MS/MS Transitions (for quantification):

- TG(16:0/18:1/18:2): [M+NH4]+ → 577.5 (18:2 fragment)

- Cer(d18:1/24:0): [M+H]+ → 264.3 (d18:1 sphingoid base)

- SM(d18:1/24:0): [M+H]+ → 184.1 (phosphocholine headgroup)

- Chromatography:

4. Visualizing Metabolic Pathways and Workflows

Sphingolipid Pathway in Metabolic Disease

UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics Workflow

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Lipid Biomarker Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., TG-d5, Cer-d7, SM-d9) | Critical for accurate quantification; corrects for matrix effects and recovery losses during sample preparation. |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Primary solvent for robust liquid-liquid extraction of a broad range of lipid classes. |

| C8 or C18 UHPLC Column (1.7-1.8 µm particle size) | Provides high-resolution separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to MS detection. |

| Ammonium Formate / Acetate | LC-MS compatible additive to mobile phases that promotes stable adduct formation (e.g., [M+NH4]+ for TGs). |

| Sphingolipid Pathway Inhibitors (e.g., Myriocin, Fumonisin B1) | Pharmacological tools to inhibit de novo ceramide synthesis (Myriocin) or ceramide synthase (Fumonisin B1) for functional studies. |

| Commercial Quality Control (QC) Plasma Pools | Used to monitor instrument performance and batch-to-batch reproducibility throughout a large analytical sequence. |

Linking Lipidomic Signatures to Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Disease Progression

Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, has emerged as a powerful analytical approach for comprehensively profiling lipid species in biological systems. The lipidome encompasses a vast array of molecules that serve not only as structural components of cellular membranes but also as signaling mediators and energy reservoirs [21] [22]. Technological advances in ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) have enabled researchers to precisely characterize lipidomic signatures associated with various disease states, providing unprecedented insights into pathophysiological mechanisms [22] [23]. Within the context of diabetes mellitus and hyperuricemia research, lipidomic profiling offers exceptional potential for identifying novel biomarkers, elucidating metabolic disruptions, and monitoring disease progression [2] [24].

The integration of lipidomic data with clinical parameters facilitates a deeper understanding of how specific lipid classes contribute to disease pathogenesis. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, methodologies, and applications of UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomics in characterizing lipid signatures in metabolic diseases, with particular emphasis on diabetes and hyperuricemia. By providing detailed experimental protocols, data interpretation frameworks, and visualization approaches, this resource aims to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in advancing this rapidly evolving field.

Lipidomic Alterations in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetes Mellitus and Hyperuricemia

Comparative lipidomic analyses reveal distinct alterations in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and those with concomitant hyperuricemia (DH). A study investigating plasma untargeted lipidomics identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with multivariate analyses demonstrating significant separation trends among DH, DM, and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) groups [2]. This finding confirms distinct lipidomic profiles associated with these metabolic conditions.

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Metabolites in Diabetes Mellitus with Hyperuricemia

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Molecules | Regulation Trend | Metabolic Pathway Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significantly upregulated | Glycerolipid metabolism |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significantly upregulated | Glycerophospholipid metabolism |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significantly upregulated | Glycerophospholipid metabolism |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not specified | Downregulated | Glycerophospholipid metabolism |

The DH group exhibited 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites compared to NGT controls, with pronounced upregulation of 13 triglycerides (TGs), 10 phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and 7 phosphatidylcholines (PCs), while one phosphatidylinositol (PI) was downregulated [2]. Pathway enrichment analysis indicated these differential lipids predominantly affected glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014), highlighting these as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [2].

When comparing DH versus DM groups, researchers identified 12 differential lipids that were also predominantly enriched in these same core pathways, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [2]. These findings suggest that hyperuricemia exacerbates lipid metabolic disturbances in diabetic patients, potentially accelerating disease progression and complication development.

Phenotype-Specific Lipidomic Patterns

Lipid metabolism displays phenotype-specific regulatory patterns across distinct clinical presentations. Research in pediatric populations has revealed that obesity is characterized by marked upregulation of triacylglycerols (TG), while hyperuricemia exhibits predominant downregulation of membrane lipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), with phosphatidylinositol (PI) showing heterogeneous alterations [24]. The combined phenotype of obesity and hyperuricemia demonstrates more extensive disruptions across multiple metabolic pathways [24].

Correlation analyses have revealed consistent relationships between specific lipid classes and clinical parameters. TGs show an inverse relationship with glomerular filtration rate (GFR), ceramides (Cer) associate strongly with insulin metabolism, and LPC demonstrates a distinctive positive correlation with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in hyperuricemia groups [24]. Carnitines (CAR) exhibit bidirectional associations with kidney function-related parameters, suggesting their potential as biomarkers for renal complications in metabolic diseases [24].

Experimental Workflows in Lipidomics Research

Sample Collection and Preparation

Proper sample collection and preparation are critical for reliable lipidomic profiling. For plasma samples, collection of fasting venous blood is recommended, followed by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma [2]. The resulting plasma should be aliquoted and stored at -80°C until analysis to preserve lipid stability [22].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipid Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction | Used in liquid-liquid extraction; 800μL added to 100μL plasma [2] |

| Methanol | Protein precipitation and lipid extraction | Pre-cooled; 240μL added to plasma sample [2] |

| Ammonium formate | Mobile phase additive | Enhances ionization; used at 10mM concentration in acetonitrile [2] |

| Internal standards | Quantification reference | Added prior to extraction to assess recovery and quantification accuracy [25] |

| Isopropanol | Solvent for lipid resuspension | Used at 90% with acetonitrile for sample reconstitution after drying [25] |

For lipid extraction, the MTBE/methanol method has demonstrated effectiveness. The protocol involves adding 200μL of 4°C water to 100μL of plasma, followed by 240μL of pre-cooled methanol and 800μL of MTBE [2]. After mixing, samples undergo sonication in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes and stand at room temperature for 30 minutes. Centrifugation at 14,000×g for 15 minutes at 10°C separates phases, with the upper organic phase collected and dried under nitrogen [2]. The dried lipids are then reconstituted in appropriate solvents for analysis.

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography separation typically utilizes reversed-phase columns, such as Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) [2]. The mobile phase commonly consists of acetonitrile-water mixtures with ammonium formate or formic acid as additives to enhance ionization [2] [25].

Mass spectrometry analysis employs both positive and negative ionization modes to comprehensively capture the lipidome. For Q-Exactive Plus instruments, positive ion spray voltage is typically set at 3.0 kV and negative ion spray voltage at 2.5 kV, with sheath gas flow of 45 arbitrary units and auxiliary gas flow of 15 arbitrary units [25]. The MS1 scanning range is generally set between 200-1800 m/z to cover most lipid species.

Data processing involves peak alignment, peak picking, and quantification using software such as Compound Discoverer, with subsequent matching against lipid databases including LIPID MAPS and LipidBlast for accurate qualitative and relative quantitative results [8].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomic Profiling

Analytical Techniques and Instrumentation

Mass Spectrometry Platforms

Various mass spectrometry platforms are available for lipidomic analyses, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The selection of an appropriate platform depends on research objectives, whether untargeted exploration or targeted quantification.

Table 3: Mass Spectrometry Platforms for Lipidomic Analysis

| Method | Advantages | Limitations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-QTOF/MS | High mass accuracy and resolution; suitable for untargeted analysis and identification of unknown compounds | Lower sensitivity than MRM mode scans; longer run times; high cost | Structural elucidation of novel lipid metabolites [22] |

| LC-Orbitrap | Enhanced separation of isotopic peaks with similar retention times; high mass resolution | Lower sensitivity than MRM mode scans; longer run times; high cost | Untargeted lipidomics with high resolution [22] |

| LC-Triple Quadrupole | Enhanced sensitivity and selectivity via MRM; optimal for targeted quantification | Lower resolution than QTOF or Orbitrap; less effective for unstable lipids | Targeted quantification of specific lipid classes [22] |

| Nano-ESI-MS | Small sample volume requirements; steady ionization environment; high signal intensities | Longer run times; narrow needles prone to clogging | Limited sample availability studies [22] |

| MALDI-TOF | Capable of generating 2D images depicting lipid localization in tissues | Low confidence in identifying lipid species without MS/MS | Spatial distribution studies in tissues [22] |

For comprehensive lipidomic profiling in diabetes and hyperuricemia research, LC-QTOF/MS and LC-Orbitrap platforms offer the necessary resolution and mass accuracy for untargeted analysis, enabling discovery of novel lipid biomarkers [22]. Conversely, for validation studies and targeted quantification of specific lipid panels, LC-Triple Quadrupole systems operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode provide superior sensitivity and precision [22].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Lipidomic datasets are inherently high-dimensional, requiring specialized statistical approaches for meaningful interpretation. Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) are widely employed for visualizing group separations and identifying differentially abundant lipids [2]. These multivariate techniques help discern global lipidomic patterns among experimental groups while assessing data quality and outliers.

For feature selection in high-dimensional data, machine learning approaches such as least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression have demonstrated utility in identifying the most informative lipid biomarkers [25] [8]. LASSO performs both feature selection and regularization simultaneously, enhancing model interpretability and predictive performance by selecting a subset of relevant lipids while constraining less relevant ones.

Pathway analysis tools such as MetaboAnalyst 5.0 enable researchers to identify enriched metabolic pathways from lists of differentially abundant lipids, providing biological context to lipidomic findings [2]. This platform facilitates the calculation of pathway impact values based on topological considerations, highlighting pathways most significantly perturbed in specific disease states.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Clinical Applications

Metabolic Pathways in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

Lipidomic studies in diabetes and hyperuricemia have consistently identified glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism as central pathways disrupted in these conditions [2]. Glycerophospholipids, including phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), serve as crucial structural components of cellular membranes and play important roles in cellular signaling [21] [23]. Their disruption can impair membrane fluidity, receptor function, and signal transduction processes relevant to insulin resistance and inflammatory responses.

The observed upregulation of triglycerides (TGs) in diabetes with hyperuricemia reflects enhanced lipogenesis and altered energy storage patterns, potentially contributing to ectopic lipid accumulation and lipotoxicity mechanisms implicated in metabolic syndrome progression [2] [24]. These lipid alterations may promote insulin resistance through activation of inflammatory pathways and intracellular signaling cascades that interfere with insulin action.

Figure 2: Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Lipid Alterations to Disease Progression

Biomarker Discovery and Clinical Translation

Lipidomic signatures show significant promise as biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. In critical illness, phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) have been identified as prognostic markers, with elevated levels associated with worse outcomes in both trauma and severe COVID-19 patients [26]. This suggests that certain lipidomic patterns may transcend specific disease etiologies, reflecting common pathophysiological pathways in systemic metabolic stress.

In schizophrenia research, a panel of three lipid biomarkers - PC(18:2e19:0), PE(53:7), and TG(16:2e19:0_20:5) - demonstrated capability to distinguish poor and good responders to antipsychotic treatment, achieving an AUC of 0.805 [25]. This highlights the potential of lipidomic profiling for predicting treatment response and guiding therapeutic decisions.

Similar approaches in diabetes and hyperuricemia research could yield biomarker panels for identifying patients at high risk for disease progression or complications, enabling targeted interventions and personalized treatment strategies. The distinct lipidomic signatures observed in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia suggest potential for developing biomarkers that reflect the synergistic metabolic disturbances in this patient population [2] [24].

UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomic profiling provides a powerful approach for elucidating the complex relationships between lipid metabolism and disease pathophysiology in diabetes and hyperuricemia. The distinct lipid signatures associated with these conditions reflect underlying metabolic disruptions that contribute to disease progression and complications. Through standardized methodologies encompassing sample preparation, chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric analysis, and advanced data processing, researchers can obtain comprehensive lipidomic profiles that offer unique insights into disease mechanisms.

The integration of lipidomic data with clinical parameters and outcomes facilitates the discovery of novel biomarkers with diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic potential. As the field advances, standardization of analytical protocols and computational pipelines will enhance reproducibility and comparability across studies. Lipidomics holds particular promise for precision medicine approaches in metabolic diseases, potentially guiding targeted interventions based on individual lipidomic profiles to improve patient outcomes.

A Practical Guide to UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomic Workflows for Metabolic Profiling

Lipidomics, a specialized branch of metabolomics, provides a comprehensive approach to analyzing the complete lipid profile within a biological system [27]. In the context of diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), lipidomic profiling using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has revealed significant alterations in lipid metabolism pathways, specifically identifying 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in DH patients compared to healthy controls [2]. These perturbations are primarily enriched in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways, offering crucial insights into the intertwined pathophysiological mechanisms of these metabolic disorders [2]. This technical guide details the essential workflow from sample collection to data acquisition for UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomic profiling, specifically framed within diabetes and hyperuricemia research.

Sample Collection and Preparation

Sample Collection Protocols

Proper sample collection and immediate processing are critical first steps in lipidomics, as lipids are prone to enzymatic and chemical degradation [28].

- Biological Matrices: Plasma/serum is commonly used. For DH studies, collect fasting blood samples [2].

- Collection Protocol: Draw 5 mL of fasting morning blood into appropriate collection tubes [2].

- Initial Processing: Centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma [2].

- Aliquoting and Storage: Transfer 0.2 mL of the upper plasma layer into cryovials. Flash-freeze and store at -80°C to preserve lipid integrity [2] [28]. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

For tissue samples, homogenization is essential to ensure equal lipid accessibility from all tissue regions. Methods include shear-force-based grinding (Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer) or crushing liquid-nitrogen-frozen tissue with a pestle and mortar [28].

Lipid Extraction Methodologies

Lipid extraction serves to reduce sample complexity by removing non-lipid compounds and enriching analytes of interest for improved signal-to-noise ratios [28].

Figure 1: MTBE-based Liquid-Liquid Extraction Workflow. Based on the protocol used in a diabetes with hyperuricemia lipidomic study [2].

The MTBE (methyl tert-butyl ether) method is widely used in lipidomics research [2] [28]. This method offers comparable efficiency to traditional chloroform-based protocols but with easier handling and enhanced safety [28]. The phase separation in MTBE extraction results in an upper organic phase containing lipids and a lower aqueous phase with salts and hydrophilic compounds, simplifying lipid recovery [28].

Alternative extraction methods include:

- Folch and Bligh & Dyer: Chloroform-based methods using ternary mixtures of chloroform, methanol, and water [28] [29].

- BUME method: A fully automated protocol using butanol/methanol sequentially added with heptane/ethyl acetate and acetic acid, suitable for high-throughput screening in 96-well plates [28].

- One-step protocols: Single-phase extractions using methanol, ethanol, 2-propanol, or acetonitrile followed by protein precipitation, offering higher efficiency for polar lipids but potentially increasing instrument contamination [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 1: Essential Reagents for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Methanol, Chloroform, Butanol [2] [28] | Lipid solubilization and separation from non-lipid compounds during liquid-liquid extraction. |

| LC-MS Solvents | Acetonitrile, Isopropanol, Water (LC-MS grade) [2] [30] [31] | Mobile phase composition for UHPLC separation; minimizes background interference in MS detection. |

| Additives | Ammonium formate, Formic acid, Acetic acid [2] [32] [29] | Enhances ionization efficiency in the MS source and helps control chromatographic separation. |

| Internal Standards | Deuterated lipid standards (e.g., EquiSplash Lipidomix), 1,2,3-tripelargonoyl-glycerol [30] [33] | Normalization for extraction efficiency, instrument variability, and quantitative accuracy. |

| 8-pCPT-cGMP-AM | 8-pCPT-cGMP-AM, MF:C19H19ClN5O9PS, MW:559.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TCO-PEG12-TFP ester | TCO-PEG12-TFP ester, MF:C42H67F4NO16, MW:918.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis: Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

Chromatographic Separation

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography provides critical separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to mass spectrometry analysis, reducing ion suppression and enabling identification of isomeric lipids [30] [29].

- Column Technology: Use a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) or equivalent reversed-phase column [2] [29].

- Temperature Control: Maintain column at 50°C for enhanced elution of late-eluting lipids like triacylglycerols [29].

- Mobile Phase:

- Gradient Elution: Implement a multi-step gradient, for example: start at 65% A / 35% B, ramp to 80% B in 2 min, to 100% B in 7 min, and hold for 7 min [29].

- Flow Rate and Injection: 0.400 mL/min flow rate with 2.0 μL injection volume [29]. Total analysis time is approximately 12-16 minutes per sample.

Mass Spectrometric Detection

Mass spectrometry is the cornerstone of detection and identification in lipidomics due to its sensitivity, specificity, and dynamic range [32] [27].

- Ionization Source: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is most common, capable of ionizing polar, thermally labile lipids [27]. Both positive and negative ionization modes are typically used, sometimes with polarity switching during a single run [32].

- Mass Analyzers: Quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) and Orbitrap instruments provide high resolution and mass accuracy, enabling precise lipid identification [27] [29]. Triple quadrupole (QqQ) systems offer high sensitivity for targeted analysis [31] [27].

- Data Acquisition Modes:

- Untargeted Lipidomics: Full scan mode at high resolution (e.g., m/z 300-1200) detects a broad range of lipids [27] [29].

- Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA): Automatically selects abundant precursors for fragmentation, providing structural information [32].

- All Ion Fragmentation (AIF): Fragments all generated ions simultaneously at different collision energies, providing comprehensive structural data in a single run [32].

- Targeted Acquisition: For quantitative studies, use selected reaction monitoring (SRM) on QqQ instruments for highest sensitivity [31] [27].

Figure 2: UHPLC-MS/MS Data Acquisition Pathways. Multiple MS acquisition strategies can be employed depending on research goals [32] [27].

Data Processing, Analysis, and Application to Diabetes-Hyperuricemia

Data Processing and Lipid Identification

Processing raw UHPLC-MS/MS data requires specialized software for peak detection, alignment, and identification [29].

- Peak Processing: Use software like MZmine 2 for peak detection, alignment, integration, and normalization [29].

- Lipid Identification: Match accurate mass and retention time against internal spectral libraries [29]. Confirm identities using MS/MS fragmentation patterns compared to standards or database spectra [32].

- Quantification: Normalize using class-specific internal standards (e.g., deuterated lipids) [30] [29]. Response factors may be applied for absolute quantification.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia

In DH research, multivariate statistical analyses like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) reveal separation trends among DH, DM, and healthy control groups [2]. Differential lipid molecules are subsequently analyzed for pathway enrichment.

Table 2: Key Lipid Alterations and Perturbed Pathways in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

| Analytical Comparison | Significantly Altered Lipids | Perturbed Metabolic Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| DH vs. Healthy Controls | 13 Triglycerides (TGs) ↑10 Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) ↑7 Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) ↑1 Phosphatidylinositol (PI) ↓ [2] | Glycerophospholipid metabolism (Impact: 0.199)Glycerolipid metabolism (Impact: 0.014) [2] |

| DH vs. DM | 12 Differential Lipids identified [2] | Enriched in the same core pathways (Glycerophospholipid and Glycerolipid metabolism) [2] |

These findings underscore the central role of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism disruptions in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [2]. The identified lipid species and pathways serve as potential biomarkers for disease progression and therapeutic targets.

Method Validation and Quality Control

Rigorous validation and quality control are essential for generating reliable lipidomic data.

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: Prepare pooled QC samples from all study samples and inject regularly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument stability [2].

- Method Validation: For targeted methods, validate linearity (typically over >4 orders of magnitude), accuracy, precision, and limits of quantitation (can reach femtomole levels on-column) [30].

- Standardization: Use standardized extraction protocols and internal standards to minimize technical variability [28].

This comprehensive workflow from sample collection through data acquisition provides a robust framework for conducting UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic profiling in diabetes and hyperuricemia research, enabling the discovery of lipid biomarkers and mechanistic insights into these interconnected metabolic disorders.

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) has emerged as a cornerstone technique in modern lipidomics, particularly for the analysis of complex biological samples in disease research. Its superior speed, resolution, and sensitivity compared to traditional HPLC make it indispensable for unraveling the intricate lipid landscapes associated with metabolic diseases [34] [35]. This technical guide focuses on optimizing UHPLC conditions for separating complex lipid mixtures within the specific context of a broader thesis on UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic profiling in diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) research. Lipid metabolism is profoundly disrupted in these conditions; disorders of lipid metabolism are a known risk factor for diabetes, and hyperuricemia can itself lead to lipid abnormalities [2] [14]. The intent of a quantitative bioanalytical method in this field is to provide a precise and accurate estimation of the concentration of target lipids in these complicated biological samples, which is essential for drug development, clinical analysis, and pharmacokinetic studies [34].

However, the inherent complexity of biological samples like plasma or serum presents significant challenges for UHPLC analysis. These samples are an intricate tapestry of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and other biomolecules, each with diverse physicochemical properties [34]. Two primary challenges are:

- Matrix Effects and Ion Suppression: During the ionization process in mass spectrometry, co-eluting biomolecules can interact with the analyte of interest, suppressing or enhancing its signal and leading to erroneous quantification. This is particularly problematic for low-concentration lipids and can mask their presence entirely. Phospholipids are especially known to cause significant ion suppression in electrospray ionization (ESI) [34].

- Analyte Diversity and Co-elution: Lipidomic samples harbor a vast array of molecules with diverse polarity, size, and charge. This diversity makes achieving optimal chromatographic separation a challenge, as lipids with similar properties may co-elute, resulting in overlapping peaks that hinder accurate identification and quantification [34].

Core UHPLC Optimization Parameters

Optimizing a UHPLC method for complex lipid mixtures requires meticulous attention to several key parameters to achieve efficient separation, minimize matrix effects, and improve overall sensitivity and accuracy.

Column Selection and Chemistry

The choice of chromatographic column is fundamental. UHPLC utilizes columns packed with sub-2 µm particles, which operate at very high pressures (up to 1000 bar or more) to provide dramatically reduced analysis times, enhanced resolution, and higher sensitivity compared to traditional HPLC [36] [35]. The typical peak widths generated are in the order of 1–2 seconds, which greatly improves chromatographic resolution and reduces the problem of ion suppression from co-eluting peaks [35]. For lipid separation, reversed-phase columns, particularly C18 chemistries, are most common.

Table 1: UHPLC Column and System Conditions for Lipidomics

| Parameter | Typical Specification for Lipidomics | Function and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Column Chemistry | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 [2] | Provides the stationary phase for analyte separation based on hydrophobicity. |

| Column Dimension | 2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm length [2] | Standard format for UHPLC-MS/MS applications. |

| Particle Size | 1.7 µm [2] [35] | Smaller particles enable higher efficiency, resolution, and speed. |

| System Pressure | Operates at high pressure (up to 1000 bar+) [36] | Required to drive mobile phase through a column packed with sub-2 µm particles. |

| Column Temperature | 45°C [2] | Higher temperature can reduce mobile phase viscosity, improving efficiency. |

| Injection Volume | Lower than HPLC (e.g., 3 µL) [35] | Higher efficiency and sensitivity with minimal volume. |

Mobile Phase Composition and Gradient

The mobile phase composition and gradient profile are critical for eluting the wide range of lipids present in a sample. The mobile phase typically consists of a aqueous-based solvent (A) and an organic-rich solvent (B).

Table 2: Mobile Phase Components and Elution Protocols

| Component | Common Compositions | Role in Separation |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase A | 10 mM ammonium formate in water [2] or ACN/H2O (60:40 v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate [14] | Aqueous-based solvent for initial weak elution strength. Additives like ammonium formate improve ionization. |

| Mobile Phase B | 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile:isopropanol (IPA) (e.g., 10:90) [2] or ACN:IPA (2:9 v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate [14] | Organic-rich solvent for strong elution strength. IPA is effective at eluting more non-polar lipids. |

| Gradient Example | - 0-2 min: 30% B- 2-25 min: 30% B to 100% B- 25-35 min: 100% B (wash)- 35-35.1 min: 100% B to 30% B- 35.1-40 min: 30% B (re-equilibration) [2] [14] | A shallow or complex gradient is necessary to resolve the hundreds of lipid species with subtle differences in hydrophobicity. |

Sample Preparation

Effective sample preparation is critical for successful UHPLC-MS/MS analysis of lipids, as it removes proteins and other matrix interferences that can cause ion suppression and damage the instrument.

- Lipid Extraction: A common and robust method is a liquid-liquid extraction based on methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). A standard protocol involves:

- Vortexing 100 µL of plasma with 200 µL of water.

- Adding 240 µL of pre-cooled methanol, followed by 800 µL of MTBE.

- Sonicating in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes and standing at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Centrifuging at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C.

- Collecting the upper organic phase and drying it under a stream of nitrogen.

- Reconstituting the dried lipids in 100 µL of isopropanol/acetonitrile (90:10) for analysis [2] [14].

- Protein Precipitation: While simple, protein precipitation using organic solvents like acetonitrile or methanol is often insufficient for lipidomics as it does not effectively remove phospholipids, which are a major source of matrix effects [34].

Experimental Protocols and Applications in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Research

The following workflow and protocol details are derived from recent lipidomic studies investigating diabetes and hyperuricemia.

Diagram 1: Lipidomics workflow for diabetes-hyperuricemia research

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Item | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC System | High-pressure pump, autosampler, and column oven for precise separation. | Waters ACQUITY UPLC system or equivalent [2]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | High-resolution mass analyzer for accurate mass detection and structural characterization. | Q-Exactive Plus (Orbitrap) or other Q-TOF/Triple Quadrupole instruments [2] [35]. |

| Chromatography Column | The core component for separating lipid molecules. | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (1.7 µm, 2.1x100 mm) [2]. |

| Methyl tert-Butyl Ether (MTBE) | Primary solvent for liquid-liquid lipid extraction. | Effectively extracts a broad range of lipid classes [2] [14]. |

| HPLC-grade Solvents | Used for mobile phases and sample preparation to minimize background noise. | Acetonitrile, Isopropanol, Methanol, Water [2] [14]. |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive to improve ionization efficiency and aid in adduct formation. | Typically used at 10 mM concentration [2] [14]. |

| Internal Standards | Correct for variability in sample prep, injection, and ionization. | Stable isotope-labeled lipid standards (SIL-IS) are ideal [34]. |

Key Findings and Differential Lipids

Application of the optimized UHPLC-MS/MS protocol in clinical research has revealed distinct lipid signatures associated with disease states. A study comparing patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH), diabetes mellitus (DM) alone, and healthy controls (NGT) identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses [2]. Multivariate analyses confirmed distinct lipidomic profiles between these groups.

Table 4: Significantly Altered Lipid Metabolites in Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Research

| Lipid Class | Example Molecule(s) | Trend (DH vs NGT) | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) [2] | Significantly Upregulated | Associated with insulin resistance and core components of glycerolipid metabolism pathway [2]. |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) [2] | Significantly Upregulated | Key components of cell membranes; enriched in glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway [2]. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) [2] | Significantly Upregulated | Major membrane phospholipids; central to glycerophospholipid metabolism [2] [14]. |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not Specified [2] | Downregulated | Involved in cell signaling; part of the disturbed glycerophospholipid metabolism network. |

Pathway analysis of these differential lipids using platforms like MetaboAnalyst 5.0 consistently identifies glycerophospholipid metabolism and glycerolipid metabolism as the most significantly perturbed pathways in patients with combined diabetes and hyperuricemia [2]. These findings are corroborated by other multiomics studies, which also found lipid metabolites involved in arachidonic acid metabolism and linoleic acid metabolism in hyperuricemia patients [14].

Diagram 2: Proposed lipid-immune pathway in diabetes-hyperuricemia

Furthermore, these lipid alterations are linked to changes in immune factors. Studies have shown that interleukin 6 (IL-6), carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT1), glucose (Glu), and lactic acid (LD) are associated with the dysregulated glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway, suggesting a connection between lipid disorders and immune and metabolic shifts in patients with hyperuricemia [14].