Validating lncRNA Prognostic Signatures in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From Bench to Bedside

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, with a 5-year survival rate below 20% for advanced-stage patients.

Validating lncRNA Prognostic Signatures in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From Bench to Bedside

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide, with a 5-year survival rate below 20% for advanced-stage patients. This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) prognostic signatures for HCC, synthesizing evidence from multiple validation cohorts including TCGA and GEO databases. We examine the foundational biology establishing lncRNAs as key regulators in HCC pathogenesis, methodological frameworks for signature development using machine learning approaches like LASSO-Cox regression, optimization strategies addressing technical and biological challenges, and rigorous validation paradigms incorporating multi-omics data and functional studies. The analysis demonstrates that validated multi-lncRNA signatures—including models based on m6A modification, amino acid metabolism, and immune-related pathways—consistently outperform traditional clinical staging systems, with area under curve (AUC) values reaching 0.846 in some cohorts. These signatures not only predict survival but also inform immunotherapy response and potential therapeutic targeting, representing a paradigm shift in HCC prognostication and personalized treatment approaches.

The Biological Foundation: Understanding lncRNA Roles in HCC Pathogenesis

Clinical Context of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a major global health challenge, ranking as the sixth most common malignant tumor worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. With over 900,000 new cases annually, HCC accounts for 75-90% of all primary liver cancers [2] [3] [4]. Despite advances in therapeutic options, the five-year survival rate for advanced HCC patients remains below 20%, largely due to late diagnosis and heterogeneous treatment responses [5]. Most concerning are the exceptionally high recurrence rates of 60-70% within five years post-resection, creating a critical management challenge [2].

The disease typically arises in the context of chronic liver diseases including hepatitis B or C infection, alcoholic liver disease, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease [1] [3]. This complex etiology contributes to significant molecular heterogeneity, which profoundly impacts treatment efficacy and patient prognosis [6]. The insidious onset of HCC means a majority of patients present with advanced disease stages, precluding curative surgical intervention and substantially diminishing survival prospects [2] [1].

Table 1: Current Challenges in HCC Clinical Management

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Limited sensitivity of AFP for early-stage detection; inability of conventional imaging to identify micrometastatic disease [5] | Late-stage diagnosis in majority of patients |

| Prognostic Stratification | Inadequate accounting for molecular heterogeneity in current staging systems [6] | Inaccurate survival prediction and suboptimal treatment selection |

| Treatment Response | Low overall response rates (~20%) to immunotherapy; heterogeneous immune microenvironments [3] | Limited efficacy of systemic therapies |

| Recurrence Monitoring | High 5-year recurrence rates (60-70%) post-resection [2] | Poor long-term survival despite initial treatment success |

Limitations of Current Prognostic Systems

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification system remains the global reference for HCC prognostication and treatment allocation, with the 2025 update preserving its direct linkage between stages and evidence-based first-option treatments [7]. However, this system faces significant limitations in addressing the profound molecular heterogeneity of HCC. The BCLC staging incorporates performance status, tumor burden, and liver function, but does not adequately account for biological variables that significantly influence outcomes [8].

Recognizing these limitations, the 2025 BCLC update has integrated the CUSE framework (Complexity, Uncertainty, Subjectivity, Emotion) to help multidisciplinary teams navigate evidence gaps and explicitly address uncertainty [7]. This framework turns "unavoidable doubt into a shared, iterative process" by defining therapeutic goals, grading options with evidence strength and gaps, aligning choices with comorbidities and patient values, and selecting plans with regular check-ins as new information emerges [7]. While this represents progress, it highlights the fundamental deficiency in objective molecular biomarkers to guide precision medicine approaches.

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and ESMO guidelines emphasize standardized imaging using LI-RADS criteria and multiparametric CT or MRI for diagnosis and staging [8] [4]. However, the guidelines note that routine molecular analysis is not currently recommended for clinical decision-making, reflecting the translational gap between biomarker research and clinical application [8]. This gap is particularly problematic given that current biomarkers like alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) exhibit limited sensitivity for early-stage detection and response prediction [5].

The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) introduces additional complexity, with immunosuppressive elements such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and inactivated M0 macrophages contributing to treatment resistance [2]. Hypoxia and anoikis resistance further shape aggressive tumor phenotypes, yet these factors are not incorporated into conventional staging systems [2]. The evolving landscape of immunotherapy, while promising, has highlighted the critical need for biomarkers that can predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and combination regimens [3].

Emerging Prognostic Biomarkers and Signatures

LncRNA-Based Signatures

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as powerful prognostic biomarkers in HCC due to their crucial roles in regulating tumor biology, including proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic response [9]. These transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides function through diverse mechanisms: serving as signaling molecules that recruit transcription factors, guiding chromatin-modifying enzymes to specific genomic locations, sequestering transcription factors or microRNAs, and mediating the formation of multi-component complexes [9].

Table 2: Validated Single LncRNA Prognostic Biomarkers in HCC

| LncRNA | Expression in HCC | Hazard Ratio (HR) | 95% CI | P-value | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINC00152 | High | 2.524 | 1.661-4.015 | 0.001 | qRT-PCR [9] |

| LINC01554 | Low | 2.507 | 1.153-2.832 | 0.017 | qRT-PCR [9] |

| LINC01139 | High | 2.721 | 1.289-4.183 | 0.019 | qRT-PCR [9] |

| HOXC13-AS | High | 2.894 (OS), 3.201 (RFS) | 1.183-4.223 (OS), 1.372-4.653 (RFS) | 0.015 (OS), 0.004 (RFS) | qRT-PCR [9] |

| LASP1-AS | Low | 1.884 (training), 3.539 (validation) | 1.427-2.841 (training), 2.698-6.030 (validation) | <0.0001 | qRT-PCR [9] |

Multigene lncRNA signatures offer enhanced prognostic capability by capturing broader biological processes. A hypoxia- and anoikis-related nine-lncRNA signature effectively stratified HCC patients into distinct risk groups, with the high-risk group showing increased immunosuppressive elements (Tregs and inactivated M0 macrophages) and limited immunotherapy efficacy [2]. The signature included specifically downregulated lncRNAs (LINC01554, FIRRE, LINC01139, LINC01134, and NBAT1) that may influence apoptosis under hypoxia and anoikis conditions [2].

Plasma exosomal lncRNAs provide a promising liquid biopsy approach for non-invasive molecular stratification. A recent study integrating transcriptomic data from 230 plasma exosomes identified a 6-gene risk score (G6PD, KIF20A, NDRG1, ADH1C, RECQL4, MCM4) that demonstrated high prognostic accuracy [5]. This exosomal lncRNA-based framework classified HCC into three molecular subtypes (C1-C3), with the C3 subtype exhibiting the poorest overall survival, advanced grade and stage, and an immunosuppressive microenvironment characterized by increased Treg infiltration and elevated PD-L1/CTLA4 expression [5].

Other Molecular Signatures

Beyond lncRNAs, various molecular signatures have shown prognostic potential in HCC. A robust 8-gene signature (MCM10, CEP55, KIF18A, ORC6, KIF23, CDC45, CDT1, and PLK4) was identified through comprehensive transcriptomic analysis, with experimental validation confirming significant upregulation of MCM10, KIF18A, CDC45, and PLK4 in HCC tissues (p<0.05) [1]. These genes are primarily involved in cell cycle regulation and DNA replication, reflecting fundamental processes in hepatocarcinogenesis.

Integrating neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and immune-related genes has yielded another promising prognostic approach. A five-gene signature (HMOX1, MMP9, TNFRSF4, MMP12, and FLT3) demonstrated strong predictive ability, with enrichment analyses revealing pathways related to retinol metabolism and cytochrome P450 drug metabolism in different risk groups [6]. Immune infiltration analysis showed regulatory T cells positively correlated with MDSCs, both directly associated with the five prognostic genes [6].

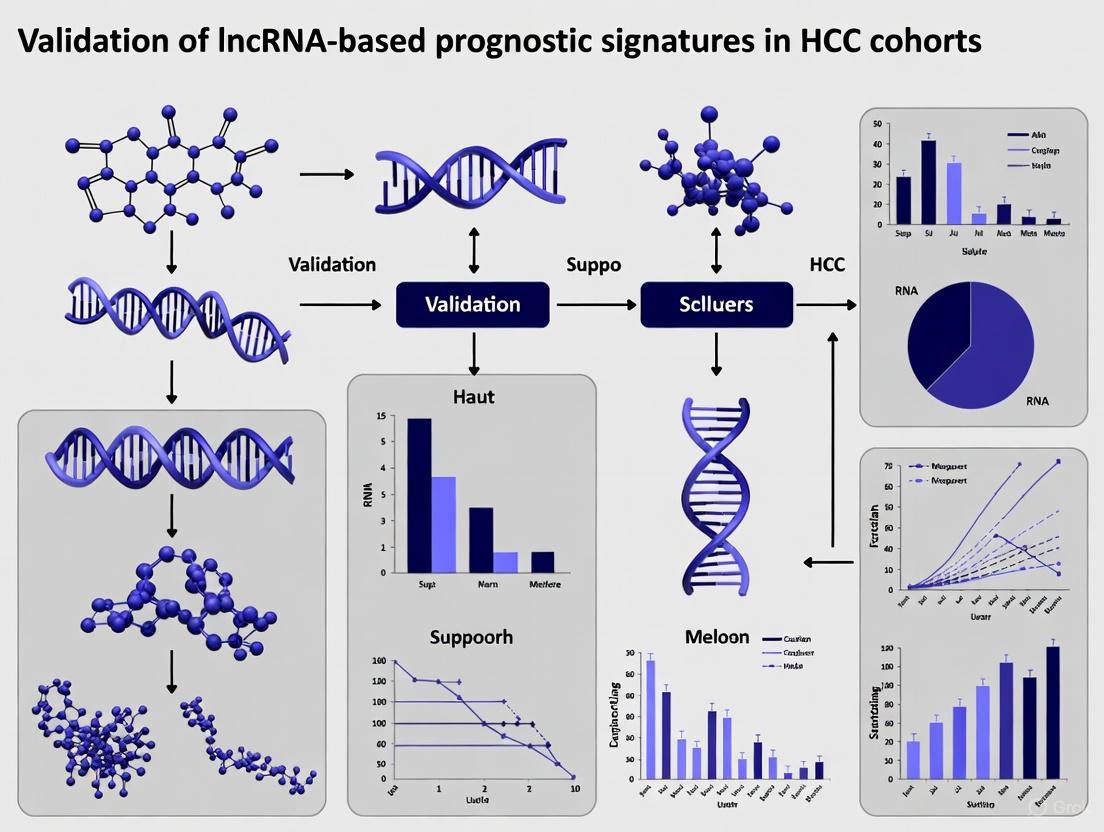

LncRNA Signature Development Workflow

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Computational Biology Methods

The development of lncRNA-based prognostic signatures relies on sophisticated computational approaches utilizing large-scale genomic datasets. Standard methodologies begin with RNA-seq data acquisition from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [2] [1]. Data preprocessing includes transformation to transcripts per million (TPM) values, log2 conversion, and normalization to ensure comparability across datasets [2] [5].

Differential expression analysis is typically performed using the DESeq2 package with thresholds of p<0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 0.5-1.0 to identify significantly dysregulated lncRNAs [1] [6]. For molecular subtyping, unsupervised consensus clustering using the ConsensusClusterPlus package applies the Pearson distance metric, PAM clustering algorithm, 80% resampling ratio, and 1000 iterations to define robust molecular subtypes [2] [5].

Competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network construction involves a multi-step process: miRNA binding sites of differentially expressed lncRNAs are predicted via the miRcode database, followed by integration of miRNA-mRNA relationships from miRTarBase, TargetScan, and miRDB databases [5]. The intersection of target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs and upregulated mRNAs in HCC tissues defines exosome-related genes, with ternary regulatory networks visualized using Cytoscape [5].

Machine learning algorithms have become indispensable for prognostic model development. Recent studies systematically compare multiple algorithms including CoxBoost, stepwise Cox, LASSO, Ridge, elastic net, survival support vector machines, generalized boosted regression models, supervised principal components, partial least squares Cox, and random survival forests [1] [5]. These approaches employ 10-fold cross-validation frameworks, using the concordance index (C-index) to optimize hyperparameters and select the most predictive gene signatures.

Experimental Validation Techniques

While computational approaches identify candidate biomarkers, experimental validation remains essential for establishing biological and clinical relevance. Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) serves as the gold standard for validating expression patterns of identified lncRNAs and genes in independent patient cohorts and HCC cell lines [2] [1] [6].

Functional studies often employ in vitro models under controlled conditions to elucidate mechanisms. For hypoxia- and anoikis-related lncRNAs, human HCC cell lines like Li-7 are cultured under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) in ultra-low adsorption plates to simulate anchorage-independent growth [2]. Total RNA extraction using commercial kits (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit) followed by cDNA synthesis and RT-qPCR with specifically designed primers enables quantification of lncRNA expression changes under these stress conditions [2].

Single-cell RNA sequencing provides unprecedented resolution for understanding cellular heterogeneity and validating cell-type-specific expression of prognostic genes. Analytical pipelines for scRNA-seq data include quality control, normalization, highly variable gene identification, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and cell type annotation [1]. This approach enables mapping of prognostic gene expression to specific cellular compartments within the tumor microenvironment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HCC Prognostic Biomarker Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Application in HCC Prognostic Research |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit [2] | High-quality RNA isolation from tissues/cells for transcriptomic studies |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | PrimeScript RT Master Mix [2] | Preparation of cDNA templates for qPCR validation |

| qPCR Reagents | TB Green Premix [2] | Quantitative measurement of lncRNA and gene expression |

| Cell Culture Media | 1640 Medium with FBS [2] | Maintenance of HCC cell lines for functional studies |

| Bioinformatics Packages | DESeq2, ConsensusClusterPlus, CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE, glmnet [2] [1] [6] | Differential expression, clustering, immune infiltration, and machine learning analyses |

| Pathway Databases | GO, KEGG, HALLMARK [2] [1] | Functional enrichment analysis of prognostic signatures |

| Public Data Repositories | TCGA, GEO, ICGC, exoRBase [2] [1] [5] | Access to large-scale genomic and clinical data |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

LncRNAs influence HCC progression through regulation of critical signaling pathways and biological processes. Hypoxia- and anoikis-related lncRNAs converge on pathways controlling tumor stemness, immune suppression, and metastasis [2]. Hypoxia activates oncogenic pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, enhancing invasion and migration while sustaining cancer stemness [2]. Simultaneously, hypoxia profoundly reshapes the tumor immune microenvironment by modulating immune cell infiltration and inducing immunosuppressive phenotypes [2].

Anoikis resistance enables epithelial-derived tumor cells to survive in suspension after detaching from the extracellular matrix, facilitating hematogenous dissemination [2]. In HCC, which arises from epithelial hepatocytes and exhibits strong vascularity, anoikis resistance significantly contributes to metastatic spread [2]. The integrated analysis of both hypoxia and anoikis mechanisms provides a more comprehensive understanding of tumor biology than either factor alone.

Plasma exosomal lncRNAs function within competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks that regulate oncogenic transcripts. These networks are significantly enriched in critical pathways including cell cycle regulation, TGF-β signaling, the p53 pathway, and ferroptosis [5]. The molecular subtypes defined by exosomal lncRNA profiles exhibit distinct pathway activations, with the poor-prognosis C3 subtype showing hyperactivation of proliferation pathways (MYC, E2F targets) and metabolic pathways (glycolysis, mTORC1) [5].

LncRNA Regulatory Mechanisms in HCC

The tumor immune microenvironment represents a critical mechanism through which prognostic signatures influence clinical outcomes. High-risk HCC subtypes consistently exhibit immunosuppressive characteristics including increased Treg infiltration, elevated expression of immune checkpoints (PD-L1, CTLA4), and higher TIDE scores predicting immunotherapy resistance [2] [5]. These features create a "cold" tumor microenvironment that limits effective anti-tumor immunity and diminishes response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [3].

Beyond the tumor microenvironment, prognostic genes identified in various signatures frequently participate in fundamental cellular processes driving hepatocarcinogenesis. The eight-gene signature (MCM10, CEP55, KIF18A, ORC6, KIF23, CDC45, CDT1, and PLK4) is enriched in cell cycle regulation and DNA replication functions [1]. Single-cell analysis reveals these prognostic genes are more highly expressed in the initial state of B cell differentiation and show the strongest interactions between B cells and macrophages in both HCC and control groups [1].

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Implications

The ultimate goal of prognostic biomarker research is clinical translation to improve patient outcomes. LncRNA-based signatures show particular promise for guiding treatment selection across different HCC stages. For early-stage HCC, prognostic signatures could identify high-risk patients who might benefit from more aggressive adjuvant therapy despite current guidelines not recommending routine adjuvant treatment post-resection or ablation [8].

In advanced disease, risk stratification enables more personalized therapeutic approaches. Low-risk patients typically demonstrate superior responses to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, while high-risk patients show increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents such as the Wee1 inhibitor MK-1775 and sorafenib [5]. Drug sensitivity analyses based on prognostic signatures can identify 74 drugs with differential sensitivity between risk groups, with compounds like axitinib showing lower sensitivity in high-risk patients, while ABT-888 demonstrates higher sensitivity in this group [6].

Molecular imaging represents an emerging approach for non-invasive assessment of tumor biology and treatment response. Techniques like positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can visualize immune checkpoints, cell infiltration, and metabolic shifts, potentially enabling pretreatment stratification and early response monitoring [3]. These imaging modalities have demonstrated area under the curve (AUC) values >0.85 in predicting response to immunotherapy, though challenges remain including cirrhosis-induced imaging artifacts [3].

The integration of lncRNA signatures with current clinical decision-making frameworks like BCLC staging offers a path toward more personalized medicine. The CUSE framework incorporated in the 2025 BCLC update explicitly acknowledges the need to address complexity, uncertainty, subjectivity, and emotion in therapeutic decisions [7]. Molecular biomarkers could transform this process by providing objective data to define therapeutic goals, grade option strength, align choices with patient biology, and select personalized management plans with regular molecular monitoring.

Once dismissed as mere "transcriptional noise" or "junk DNA," long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have undergone a dramatic re-evaluation over the past decades, emerging as crucial regulatory molecules in both normal physiology and disease states [10] [11] [12]. These RNA molecules, defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited or no protein-coding capacity, represent a major output of complex genomes [10]. The discovery that the number of protein-coding genes is similar in organisms with widely different developmental complexity (approximately 20,000 in both nematodes and humans) while non-coding DNA and RNA transcription increases with complexity forced a fundamental reassessment of genetic information flow [10]. This article examines the transformation of lncRNAs from biological curiosities to recognized key regulators, with a specific focus on their validation as prognostic signatures in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

The early perception of lncRNAs as transcriptional artifacts stemmed from their generally low sequence conservation, low expression levels, and poor visibility in genetic screens [10]. However, foundational discoveries of specific functional lncRNAs such as H19 (first identified in mice in 1984), Xist (crucial for X-chromosome inactivation), and HOTAIR progressively challenged this dogma, revealing RNA molecules with specific regulatory roles in development, epigenetics, and cellular differentiation [10] [11] [12]. The first plant lncRNA, ENOD40, was isolated from nodule primordia in Medicago plants and found to be involved in symbiotic nodule organogenesis [11]. These pioneering examples paved the way for recognizing thousands of lncRNAs across diverse species, with current databases cataloging over 20,000 lncRNA genes in humans alone [12].

LncRNA Biogenesis, Classification, and Functional Mechanisms

Defining Characteristics and Biogenesis

LncRNAs share several similarities with messenger RNAs: they are predominantly transcribed by RNA polymerase II, can undergo 5' capping and 3' polyadenylation, and are frequently spliced [10] [11] [12]. However, they diverge from protein-coding transcripts in crucial aspects: they lack extensive open reading frames, exhibit lower sequence conservation, display more specific tissue expression patterns, and are often expressed at lower levels [12]. Some lncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase I (such as ribosomal RNAs) or III (including 7SK, 7SL, and Alu RNAs), while others derive from processed introns or repetitive elements [10].

A significant proportion of lncRNAs undergo inefficient splicing compared to mRNAs, potentially due to differences in consensus sequences for splice sites or interactions with specific splicing factors [12]. While some lncRNAs are unstable, many are stabilized through polyadenylation or through secondary structures that protect them from degradation [12]. Their cellular localization—whether nuclear or cytoplasmic—profoundly influences their function and molecular partnerships [12].

Genomic Classification and Functional Mechanisms

LncRNAs are typically classified based on their genomic context relative to protein-coding genes [13]:

Table 1: LncRNA Classification by Genomic Context

| Classification | Genomic Position | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Intergenic (lincRNAs) | Located between protein-coding genes | HOTAIR, XIST |

| Intronic | Transcribed from introns of protein-coding genes | Various HCC-associated lncRNAs |

| Antisense | Transcribed from the opposite strand of protein-coding genes | HOTAIR, HOXC13-AS |

| Sense | Overlap with exons of protein-coding genes | Not specified in results |

| Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) | Transcribed from enhancer regions | Implicated in chromatin looping |

| Promoter-associated | Transcribed from promoter regions | Involved in transcription initiation |

Functionally, lncRNAs operate through diverse molecular mechanisms that can be categorized into four primary modes of action [9]:

- Signaling molecules that respond to cellular stimuli

- Guiding molecules that direct ribonucleoprotein complexes to specific genomic locations

- Decoy molecules that sequester transcription factors or microRNAs

- Scaffolding molecules that assemble multiple-component complexes

Their functional roles are intimately linked to their subcellular localization—nuclear lncRNAs typically regulate transcription, chromatin organization, and RNA processing, while cytoplasmic lncRNAs often influence mRNA stability, translation, and post-translational modifications [13] [12].

Diagram 1: Diverse Functional Mechanisms of LncRNAs. LncRNAs exert their biological effects through distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic mechanisms depending on their subcellular localization.

LncRNAs in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From Prognostic Signatures to Therapeutic Targets

The Clinical Challenge of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma represents a significant global health burden, ranking as the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality [14] [15] [9]. The disease is particularly challenging due to its frequent diagnosis at advanced stages and limited treatment options for late-stage patients [15] [16]. Chronic hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) infections, alcohol consumption, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and aflatoxin B1 intake constitute major risk factors that promote HCC through induction of DNA damage, epigenetic alterations, and oncogenic mutations [13]. The poor 5-year survival rate of under 20% for advanced HCC patients underscores the urgent need for better early detection methods and novel therapeutic approaches [15].

In this context, lncRNAs have emerged as promising molecular tools for addressing these clinical challenges. Their high tissue specificity, detectability in bodily fluids, and critical roles in tumorigenic processes make them ideal candidates as diagnostic biomarkers, prognostic indicators, and therapeutic targets [13] [9] [16].

Validated LncRNA Prognostic Signatures in HCC

Multiple research groups have developed and validated lncRNA-based prognostic signatures for HCC using various methodological approaches. The table below summarizes key studies constructing multi-lncRNA prognostic models:

Table 2: Experimentally Validated LncRNA Prognostic Signatures in HCC

| Study Focus | LncRNAs in Signature | Validation Cohort | Performance (AUC) | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfidptosis-Related [14] | AC016717.2, AC124798.1, AL031985.3 | 369 TCGA patients (training n=185, validation n=184) | 1-year: 0.756, 3-year: 0.695, 5-year: 0.701 | Stratified patients into distinct risk groups with significant survival differences |

| Amino Acid Metabolism-Related [15] | 4-lncRNA signature (including AL590681.1) | 340 TCGA patients (170 training, 170 validation) | Not specified | High-risk patients showed lower OS; AL590681.1 functional role confirmed in HCC cell lines |

| Migrasome-Related [17] | LINC00839, MIR4435-2HG | 372 TCGA tumors + independent clinical cohort (n=100) | Consistent predictive value | MIR4435-2HG promotes malignant behaviors and immune evasion; model predicts immunotherapy response |

| Combination Biomarker [16] | LINC00152, LINC00853, UCA1, GAS5 | 52 HCC patients + 30 controls | Individual lncRNAs: 60-83% sensitivity, 53-67% specificity; ML model: 100% sensitivity, 97% specificity | Machine learning integration with conventional biomarkers enhanced diagnostic precision |

These studies consistently demonstrate that lncRNA signatures can effectively stratify HCC patients into distinct prognostic subgroups, potentially guiding personalized treatment approaches. The disulfidptosis-related model specifically highlighted that high-risk patients exhibited poorer overall survival, distinct immune function profiles, differential tumor mutational burden, and varied drug sensitivity [14]. Similarly, the amino acid metabolism-related signature revealed significant differences in immune cell infiltration and checkpoint expression between risk groups, with high-risk patients potentially benefiting more from anti-PD1 treatment [15].

Individual LncRNAs with Prognostic Value in HCC

Beyond multi-lncRNA signatures, numerous individual lncRNAs have demonstrated independent prognostic value in HCC through multivariate Cox regression analyses:

Table 3: Individual LncRNAs with Validated Prognostic Significance in HCC

| LncRNA | Expression in Tumor | Prognostic Impact | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| LINC00152 | Upregulated | High expression → Shorter OS (HR: 2.524; 95% CI: 1.661-4.015; p=0.001) | 63 HCC patients, qRT-PCR detection [9] |

| LINC01146 | Downregulated | High expression → Longer OS (HR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.16-0.92; p=0.033) | 85 HCC patients, qRT-PCR detection [9] |

| HOXC13-AS | Upregulated | High expression → Shorter OS (HR: 2.894) and RFS (HR: 3.201) | 197 HCC patients, qRT-PCR detection [9] |

| LASP1-AS | Downregulated | Low expression → Shorter OS and RFS (training: HR: 1.884; validation: HR: 3.539) | 423 HCC patients across two cohorts [9] |

| ELF3-AS1 | Upregulated | High expression → Shorter OS (HR: 1.667; 95% CI: 1.127-2.468; p=0.011) | 373 HCC patients, RNAseq detection [9] |

| GAS5 | Downregulated | Tumor suppressor role, activates CHOP and caspase-9 pathways | Induces apoptosis, inhibits proliferation [16] |

These individual lncRNAs contribute to HCC progression through diverse mechanisms. For instance, LINC00152 promotes cell proliferation through regulation of CCDN1 [16], while H19 stimulates the CDC42/PAK1 axis by down-regulating miRNA-15b expression [13]. The UCA1 lncRNA similarly promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis, though its exact mechanism in HCC is not completely understood [16].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for LncRNA Signature Development

The development and validation of lncRNA prognostic signatures follows a relatively standardized workflow that integrates bioinformatic analyses with experimental validation:

Diagram 2: LncRNA Signature Development Workflow. The standardized approach for developing and validating lncRNA-based prognostic models in HCC.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experimental Procedures

Signature Development and Statistical Analysis

The construction of lncRNA prognostic models typically employs sophisticated statistical approaches:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Publicly available datasets (particularly TCGA-LIHC) provide transcriptomic data and corresponding clinical information. RNA sequencing data is normalized (typically to TPM - transcripts per million) and quality-controlled [14] [15] [17].

Identification of Relevant LncRNAs: Researchers typically identify lncRNAs of interest through correlation analysis with biologically relevant genes (e.g., disulfidptosis-related genes, amino acid metabolism genes, migrasome-related genes) using Pearson correlation with strict thresholds (|R| > 0.4-0.55, p < 0.001) [14] [15] [17].

Prognostic Model Construction: Univariate Cox regression analysis identifies lncRNAs significantly associated with overall survival. To prevent overfitting, LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Cox regression with k-fold cross-validation (typically 10-fold) is employed to select the most predictive lncRNAs. Finally, multivariate Cox regression assigns weights to each lncRNA to calculate a risk score: Risk Score = Σ(Coefficienti × Expressioni) [14] [15] [17].

Model Validation: The cohort is randomly split into training and validation sets. The model's predictive performance is assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank test) and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Increasingly, studies include external validation in independent patient cohorts [14] [15] [17].

Functional Validation Experiments

To establish biological relevance beyond statistical association, researchers employ various functional assays:

In Vitro Functional Studies: Following identification of key lncRNAs from signatures, researchers perform functional validation using HCC cell lines. This typically includes:

- Gene Knockdown: Using lncRNA-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) delivered via transfection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000) [15] [17].

- Proliferation Assays: Cell viability measured by CCK-8 assay or similar methods at various time points post-transfection [15].

- Colony Formation: Assessing long-term proliferative potential by staining and counting colonies after 14-day incubation [15].

- Migration/Invasion Assays: Transwell or wound-healing assays to evaluate metastatic potential [17].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to verify knockdown efficiency and measure downstream targets [15] [16] [17].

Molecular Mechanism Elucidation:

- Pathway Analysis: Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) identifies signaling pathways enriched in high-risk versus low-risk groups [14] [15].

- Immune Infiltration Analysis: Using algorithms like ESTIMATE or CIBERSORT to evaluate differences in tumor immune microenvironment between risk groups [14] [15] [17].

- Drug Sensitivity Prediction: Computational approaches (e.g., oncoPredict) assess potential differences in therapeutic response based on GDSC database [14].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for LncRNA Studies in HCC

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA-LIHC Dataset | Primary source of transcriptomic and clinical data | 373 liver HCC tissues + 49 normal tissues; includes RNAseq data and clinical follow-up [14] |

| RNA Isolation Kits | Extraction of high-quality RNA from tissues/cells | miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) - enables simultaneous isolation of miRNA and total RNA [16] |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | Reverse transcription of RNA to cDNA | RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) [16] |

| qRT-PCR Systems | Quantification of lncRNA expression | PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix + ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems); GAPDH normalization [16] |

| siRNA/shRNA | Gene knockdown studies | LncRNA-specific sequences; Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent [15] |

| Cell Viability Assays | Assessment of proliferation | CCK-8 assay - measures metabolic activity as surrogate for cell number [15] |

| Immune Analysis Algorithms | Evaluation of tumor immune microenvironment | ESTIMATE, CIBERSORT, TIMER - computational deconvolution of immune cell populations [14] [15] |

| Drug Sensitivity Databases | Prediction of therapeutic response | GDSC (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) - correlates genomic features with drug response [14] |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in translating lncRNA research into clinical practice. The functional characterization of most lncRNAs is still lacking, with only approximately 500-1,500 of the over 20,000 human lncRNA genes having been functionally characterized [12]. Additionally, the low conservation of many lncRNAs between species complicates the use of conventional animal models for functional studies [10]. Technical challenges include the inefficient splicing of many lncRNAs and their generally lower abundance compared to mRNAs [12].

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas:

- Comprehensive Functional Characterization: Systematic efforts to assign biological functions to the thousands of uncharacterized lncRNAs.

- Therapeutic Targeting: Developing approaches to target oncogenic lncRNAs or replace tumor-suppressive lncRNAs, potentially through antisense oligonucleotides, small molecule inhibitors, or gene therapy approaches.

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining lncRNA data with genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information to build more comprehensive models of HCC pathogenesis.

- Liquid Biopsy Applications: Optimizing detection of lncRNAs in circulating blood for non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring of HCC.

- Single-Cell Analyses: Resolving lncRNA expression and function at single-cell resolution to understand tumor heterogeneity.

The transformation of lncRNAs from "transcriptional noise" to key regulatory molecules represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in molecular biology over the past decades. Their integration into prognostic signatures for HCC exemplifies how basic biological discoveries can translate into clinically relevant applications. As research methodologies continue to advance and our understanding of lncRNA biology deepens, these molecules are poised to become increasingly important in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, characterized by its aggressive nature, frequent metastasis, and limited treatment options [18] [19]. The molecular pathogenesis of HCC involves complex genetic and epigenetic alterations, with long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) emerging as pivotal regulators in recent years [18] [13]. LncRNAs, defined as RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that lack protein-coding capacity, represent a rapidly growing class of functional RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels [13] [19]. This review provides a comprehensive mechanistic comparison of how specific lncRNAs drive HCC proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, framed within the context of validating lncRNA-based prognostic signatures in HCC cohorts. We synthesize experimental data and detailed methodologies to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a structured analysis of this dynamically evolving field.

Comparative Mechanisms of Key lncRNAs in HCC Progression

The table below summarizes the mechanisms and experimental evidence for critically important lncRNAs in HCC pathogenesis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key lncRNAs in HCC Progression

| LncRNA | Expression in HCC | Molecular Mechanism | Functional Outcome | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR594175 | Upregulated from normal to primary HCC to metastasis [20] [21] | Acts as a molecular sponge for hsa-miR-142-3p, derepressing CTNNB1 (β-catenin) and activating Wnt signaling [20] [21] | Promotes cell proliferation, invasion in vitro and subcutaneous tumor growth in vivo [20] [21] | In vitro (HepG2 cells) and in vivo mouse models; lentiviral silencing; RT-qPCR, western blot [20] [21] |

| SOX2OT | Upregulated in metastatic HCC tissues and cell lines [22] | Sponges miR-122-5p to upregulate PKM2, enhancing aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) [22] | Increases metastatic potential, cell migration, and invasion [22] | Microarray, RT-qPCR in 105 HCC patient tissues; wound healing, Transwell assays in multiple cell lines (Huh-7, HCCLM3) [22] |

| MALAT1 | Upregulated in HCC cell lines and tissues [23] | Functions as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) for miRNAs including miR-146b-5p and miR-195, activating TRAF6/Akt and EGFR pathways, respectively [23] | Enhances cell proliferation, migration, and invasion; associated with HCC recurrence [23] | siRNA silencing in vitro; correlation with patient recurrence post-liver transplantation [23] |

| HULC | Highly upregulated in liver cancer [23] | Acts as an endogenous sponge, sequestering miRNAs; epigenetic regulation [23] [19] | Promotes angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and metastasis [23] [19] | Identified via differential screening; extensive validation in clinical tissues [23] |

| H19 | Upregulated in HCC [13] | Downregulates miRNA-15b to activate the CDC42/PAK1 axis; interacts with HIF-1α to drive glycolysis [13] | Stimulates HCC cell proliferation and tumor growth [13] | Multiple mechanistic studies in cell lines and animal models [13] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Mechanistic Studies

Protocol for lncRNA-CR594175 Functional Validation

1. Lentivirus-Mediated Silencing:

- Vector Construction: A siRNA sequence (5′-GAATCCTCGGAGACAGCAG-3′) homologous to lncRNA-CR594175 was cloned into the pSIH1-H1-copGFP shRNA Vector using BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. An invalid siRNA sequence served as a negative control (NC) [20] [21].

- Lentivirus Packaging: 293TN cells were co-transfected with the constructed pSIH1-shRNA-CR594175 vector or pSIH1-NC along with pPACK Packaging Plasmid Mix using Lipofectamine 2000. The viral supernatant was harvested 48 hours post-transfection, cleared by centrifugation, and filtered through a 0.45μm PVDF membrane [20] [21].

- Cell Infection: HepG2 cells in logarithmic growth phase were seeded into 6-well plates and infected with the viral solution at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Infection efficiency was evaluated 72 hours post-infection via fluorescent marker analysis [20] [21].

2. In Vitro and In Vivo Functional Assays:

- Proliferation and Invasion Assays: Following lentiviral infection, HepG2 cell proliferation was assessed using MTT or CCK-8 assays. Cell invasion capability was measured via Transwell invasion chambers coated with Matrigel [20] [21].

- Subcutaneous Tumor Model: HepG2 cells stably expressing shRNA-CR594175 or control were subcutaneously injected into immunodeficient mice. Tumor volume was measured regularly, and tumors were harvested for further analysis after a set period, confirming that silencing inhibited subcutaneous tumor growth [20] [21].

3. Molecular Mechanism Elucidation:

- RT-qPCR and Western Blot: Total RNA and protein were extracted from tissues or cells. RT-qPCR measured lncRNA-CR594175 and hsa-miR142-3p levels. Western blot analyzed CTNNB1 and Wnt pathway-related proteins (E-cadherin, C-myc, CyclinD1, MMP-9) [20] [21].

- Luciferase Reporter Assay: A 127bp fragment of the CTNNB1 3'-UTR containing the hsa-miR-142-3p target site was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector. HepG2 cells were co-transfected with the reporter construct and miR-142-3p mimic or control, and luciferase activity was measured to confirm direct targeting [21].

Protocol for lncRNA-SOX2OT and Glycolysis Linkage

1. Correlation with Clinical Metastasis:

- Patient Imaging: 121 HCC patients underwent 18F-FDG PET scans. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was calculated to evaluate glucose metabolism levels in tumors, with significantly higher SUVmax found in metastatic tissues [22].

- Microarray and RT-qPCR Validation: LncRNA expression profiles were analyzed in ten pairs of HCC samples with different metastatic outcomes using microarray. Differentially expressed lncRNAs were validated by RT-qPCR in a larger cohort of 105 paired HCC/non-tumor specimens [22].

2. In Vitro Metabolic and Metastatic Assays:

- Glycolytic Function Measurement: Five HCC cell lines (Hep3B, Huh-7, MHCC97-L, MHCC97-H, HCCLM3) and one normal liver cell line (WRL68) were assessed for glucose uptake, glycolysis rate, and lactate production to correlate with metastatic potential [22].

- Gain-and-Loss of Function: LncRNA-SOX2OT was stably overexpressed in low-metastatic potential cells (Huh-7) and knocked down in high-metastatic potential cells (HCCLM3). Wound-healing and Transwell migration/invasion assays were performed to assess metastatic capabilities [22].

- PKM2 Interaction: miR-122-5p was identified as a direct target of lncRNA-SOX2OT. Rescue experiments involving PKM2 inhibition or miR-122-5p restoration were conducted to confirm the lncRNA-SOX2OT/miR-122-5p/PKM2 axis in regulating Warburg effect and metastasis [22].

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways

ceRNA Mechanism of lncRNA-CR594175 in Wnt Pathway Activation

Diagram 1: ceRNA Mechanism of lncRNA-CR594175. This diagram illustrates how highly expressed lncRNA-CR594175 acts as a molecular sponge for hsa-miR-142-3p, preventing it from negatively regulating CTNNB1. This derepression leads to Wnt pathway activation, promoting HCC proliferation and invasion [20] [21].

lncRNA-SOX2OT-Mediated Metabolic Reprogramming

Diagram 2: lncRNA-SOX2OT in Metabolic Reprogramming. This diagram shows how upregulated lncRNA-SOX2OT sequesters miR-122-5p, leading to increased PKM2 expression. This enhances aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), which in turn increases the metastatic potential of HCC cells [22].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for lncRNA Mechanistic Studies in HCC

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of shRNA for lncRNA silencing or cDNA for overexpression in vitro and in vivo | pSIH1-H1-copGFP shRNA Vector for CR594175 silencing [20] [21] |

| siRNA/shRNA Sequences | Sequence-specific knockdown of target lncRNAs | siRNA target sequence: 5′-GAATCCTCGGAGACAGCAG-3′ for lncRNA-CR594175 [20] [21] |

| Cell Lines | In vitro models for functional and mechanistic studies | HepG2, Huh-7, MHCC97-L, MHCC97-H, HCCLM3 with varying metastatic potential [20] [21] [22] |

| qRT-PCR Assays | Quantification of lncRNA, miRNA, and mRNA expression levels | Measurement of lncRNA-CR594175, hsa-miR-142-3p, and Wnt target genes [20] [21] [22] |

| Western Blot Reagents | Detection of protein expression and pathway activation | Analysis of CTNNB1, E-cadherin, C-myc, CyclinD1, MMP-9, PKM2 [20] [21] [22] |

| Luciferase Reporter Vectors | Validation of direct miRNA-mRNA or miRNA-lncRNA interactions | Cloning of CTNNB1 3'-UTR to verify miR-142-3p binding [21] |

| Transwell Assays | Measurement of cell invasion and migration capabilities | Matrigel-coated chambers to assess invasive potential after lncRNA modulation [20] [22] |

| Animal Models | In vivo validation of tumor growth and metastasis | Subcutaneous xenograft models in immunodeficient mice [20] [21] [22] |

The mechanistic insights into how lncRNAs drive HCC proliferation, invasion, and metastasis reveal a complex regulatory network centered on competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) activities, metabolic reprogramming, and signaling pathway activation. The consistent experimental approaches across studies—employing lentiviral modulation, in vitro functional assays, and in vivo validation—provide a robust framework for future investigations. The growing body of evidence positions lncRNAs not only as promising prognostic biomarkers but also as potential therapeutic targets. As research progresses, integrating these molecular mechanisms with clinical validation in HCC cohorts will be essential for translating these findings into meaningful prognostic tools and targeted therapies for HCC patients.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains one of the most lethal malignancies worldwide, with its pathogenesis involving complex biological processes such as DNA damage, epigenetic modification, and oncogene mutation [13]. Over the past two decades, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have received increasing attention for their roles in the occurrence, metastasis, and progression of HCC [13]. These transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides lack protein-coding capacity but play critical roles as regulators of gene expression, affecting RNA transcription and mRNA stability [13]. The validation of lncRNA-based prognostic signatures in HCC cohorts represents a promising frontier for improving diagnosis, treatment stratification, and clinical outcomes. This review comprehensively compares four key oncogenic lncRNAs—H19, HOTAIR, HULC, and NEAT1—by examining their molecular mechanisms, clinical correlations, and experimental evidence, thereby providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured analysis of their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Comparative Analysis of Key Oncogenic lncRNAs

Table 1: Characteristics and Clinical Associations of Key Oncogenic lncRNAs in HCC

| lncRNA | Genomic Location | Expression in HCC | Key Functional Mechanisms | Clinical Correlations | Prognostic Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H19 | 11p15.5 | Upregulated | Epigenetic modification, drug resistance, regulates proliferation/apoptosis via miR-675/PKM2 and AKT/GSK-3β/Cdc25A pathways [13] [24] | Associated with invasion and metastasis [24] | Poor survival, early recurrence |

| HOTAIR | 12q13.13 | Upregulated | Binds PRC2 and LSD1, regulates Wnt/β-catenin pathway, promotes EMT [13] [25] | Poor differentiation (P=0.002), metastasis (P=0.002), early recurrence (P=0.001) [25] | Shorter overall survival, independent prognostic factor |

| HULC | 6p24.3 | Upregulated | ceRNA for miR-372, activates CREB, promotes Warburg effect via LDHA/PKM2 phosphorylation [13] [26] | Advanced clinical stage, metastatic potential, HCV-positive status [26] | Poor prognosis, predicts metastasis post-resection |

| NEAT1 | 11q13.1 | Upregulated | Regulates proliferation, migration, and apoptosis through multiple mechanisms [13] | Associated with tumor progression [13] | Correlated with poor patient outcomes |

Table 2: Experimental Evidence from Functional Studies

| lncRNA | In Vitro Models | In Vivo Models | Key Functional Assays | Major Pathway Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H19 | Hep3B, HepG2 | Xenograft models | Knockdown reduces proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [24] | AKT/GSK-3β/Cdc25A signaling activation [24] |

| HOTAIR | HepG2 | Xenograft | shRNA knockdown suppresses proliferation (MTT) and invasion (Transwell) [25] | Regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling; downregulation decreases Wnt and β-catenin [25] |

| HULC | Hep3B, HepG2 | Patient tissue analysis | qRT-PCR validation in clinical samples, rolling circle amplification detection [26] | Promotes glycolysis via LDHA/PKM2 phosphorylation; creates feedback loop with miR-372/CREB [26] |

| NEAT1 | Multiple HCC lines | Not specified in results | Proliferation, migration, and apoptosis assays [13] | Multiple oncogenic signaling pathways [13] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The four lncRNAs drive hepatocarcinogenesis through distinct yet interconnected molecular mechanisms, functioning as crucial regulators of key signaling pathways in HCC progression.

H19 Oncogenic Networks

H19 exerts its oncogenic effects through several mechanistic axes. It functions as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) by sponging miR-675, which leads to the upregulation of Pyruvate Kinase M2 (PKM2) and subsequent acceleration of liver cancer stem cell proliferation [24]. Additionally, H19 inhibition has been shown to promote HCC invasion and metastasis through activation of the AKT/GSK-3β/Cdc25A signaling pathway [24]. H19 also regulates the CDC42/PAK1 axis by downregulating miRNA-15b expression, thereby increasing the proliferation rate of HCC cells [13].

HOTAIR-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation

HOTAIR promotes HCC progression primarily through epigenetic regulation and signaling pathway modulation. It interacts with Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) and lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A (LSD1), enabling genome-wide retargeting of chromatin remodeling complexes that silence multiple metastasis suppressor genes [25]. Functionally, HOTAIR depletion in HepG2 cells significantly suppresses cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in xenograft models [25]. Mechanistically, HOTAIR exerts its oncogenic effects partly through regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, with studies showing that HOTAIR inhibition downregulates both Wnt and β-catenin expression [25].

HULC Metabolic Reprogramming

HULC drives hepatocellular carcinoma progression primarily through metabolic reprogramming and the establishment of autoregulatory loops. It promotes the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) by directly binding to and increasing the phosphorylation of two key glycolytic enzymes—lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2)—thereby enhancing glycolysis in HCC cell lines [26]. Furthermore, HULC participates in a positive feedback loop where it directly binds to and sequesters miR-372, leading to decreased miR-372 activity. This reduction in miR-372 activity alleviates its inhibitory effect on cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation, consequently enhancing CREB-mediated transcription of HULC itself [26]. HULC also promotes autophagy through the miR-675/PKM2 axis, resulting in upregulation of Cyclin D1 and accelerated proliferation of liver cancer stem cells [26].

NEAT1 Functional Roles

While the specific molecular mechanisms of NEAT1 were less extensively detailed in the available search results, it has been identified as playing significant roles in regulating proliferation, migration, and apoptosis of HCC cells through various pathways [13]. Its oncogenic functions contribute substantially to HCC progression and patient outcomes.

Diagram Title: Oncogenic lncRNA Signaling Networks in HCC Progression

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Expression Analysis Protocols

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR: Total RNA from frozen HCC and paired non-cancerous tissues or cell lines is extracted using commercial kits (e.g., Ultrapure RNA Kit) [25]. cDNA is synthesized by reverse transcribing total RNA using a HiFi-MMLV cDNA Kit [25]. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) is performed using systems like the ABI7500 with SYBR Green chemistry [25]. The expression of lncRNAs (H19, HOTAIR, HULC, NEAT1) is detected using specific primers, with β-actin serving as an internal control [25]. Expression levels are calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to the housekeeping gene [25].

Clinical Validation: Studies typically analyze dozens to hundreds of paired HCC and adjacent normal liver tissues obtained from patients who underwent partial liver resection [25] [27]. Tissue samples are immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use [25]. All samples are independently confirmed by pathologists, with comprehensive documentation of clinicopathological characteristics [25].

Functional Characterization Methods

Gene Knockdown Approaches: Lentivirus-mediated small hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors are used for efficient and stable knockdown of target lncRNAs [25] [27]. For HOTAIR, specific sequences (e.g., 5′-UAACAAGACCAGAGAGCUGUU-3′) are designed and cloned into lentiviral vectors [25]. Transfection is performed using reagents such as HiPerFect [27]. Knockdown efficiency is validated via qRT-PCR [25] [27].

Phenotypic Assays:

- Cell Proliferation: MTT assays measure cell viability and proliferation rates after lncRNA knockdown [25] [27].

- Invasion and Migration: Transwell assays with Matrigel-coated chambers evaluate invasive capabilities [25].

- Colony Formation: Colony formation assays assess long-term proliferative capacity and clonogenic survival after lncRNA modulation [27].

- In Vivo Tumorigenesis: Xenograft models using immunodeficient mice subcutaneously injected with lncRNA-manipulated liver cancer cells monitor tumor growth rates and metastasis [25].

Mechanism Investigation Techniques

Pathway Analysis: Semi-quantitative RT-PCR detects expression level changes in signaling pathway molecules (e.g., Wnt/β-catenin) under conditions of lncRNA inhibition [25].

ceRNA Network Validation: Luciferase reporter assays, RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP), and pull-down assays validate direct interactions between lncRNAs and miRNAs or proteins [26].

Metabolic Studies: Seahorse extracellular flux analyzers and metabolic flux assays measure glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration changes following lncRNA manipulation [26].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Examples | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | HepG2, Hep3B, Huh-7 | In vitro functional studies | Verify authenticity, mycoplasma-free status |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Ultrapure RNA Kit, HiFi-MMLV cDNA Kit, SYBR Green Master Mix | Expression validation | Include proper controls, optimize primer efficiency |

| Lentiviral Vectors | shRNA constructs (e.g., HOTAIR: 5′-UAACAAGACCAGAGAGCUGUU-3′) | Stable gene knockdown | Monitor titer, include scramble controls |

| Functional Assay Kits | MTT assay, Transwell chambers with Matrigel, colony formation reagents | Phenotypic characterization | Standardize cell numbers, incubation times |

| Animal Models | Immunodeficient mice (e.g., BALB/c nude) | In vivo tumorigenesis | Follow IACUC protocols, adequate sample size |

The comprehensive analysis of H19, HOTAIR, HULC, and NEAT1 underscores their significant roles as oncogenic drivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Each lncRNA contributes to HCC pathogenesis through distinct molecular mechanisms, ranging from epigenetic regulation (HOTAIR) and metabolic reprogramming (HULC) to complex ceRNA networks (H19, HULC) and proliferation control (NEAT1). Their consistent upregulation in HCC tissues and strong associations with clinicopathological features—particularly tumor differentiation, metastasis, and early recurrence—highlight their potential as robust prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The validation of lncRNA-based prognostic signatures in HCC cohorts represents a critical step toward precision oncology applications. Future research should focus on standardizing detection methodologies, developing targeted delivery systems for lncRNA modulation, and validating multi-lncRNA signatures in prospective clinical trials. With continued investigation, these four oncogenic lncRNAs may form the foundation for novel diagnostic strategies and targeted therapies that ultimately improve outcomes for HCC patients.

The Rationale for Multi-lncRNA Signatures Over Single-Marker Approaches

In the pursuit of precision oncology, the discovery of reliable prognostic biomarkers has become a central focus of cancer research. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), once considered transcriptional "noise," have emerged as crucial regulators of gene expression and cellular functions, with growing evidence supporting their roles in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and treatment response [28]. Historically, cancer prognosis relied on single-marker approaches, but the complexity of cancer biology has driven a paradigm shift toward multi-gene signatures that better capture tumor heterogeneity. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)—a cancer with high mortality and limited treatment options—this evolution is particularly relevant for improving patient stratification and therapeutic decision-making [29] [30].

The transition from single-marker to multi-marker approaches represents more than just quantitative increase in biomarkers; it reflects a fundamental recognition that cancer is driven by complex, interconnected molecular networks rather than isolated molecular alterations. This review comprehensively examines the theoretical foundations, empirical evidence, and practical advantages supporting multi-lncRNA signatures over single-marker approaches, with specific application to HCC prognosis validation.

Theoretical Foundations: Why Multi-lncRNA Signatures Outperform Single Markers

Biological Plausibility: Capturing Cancer Complexity

The superior performance of multi-lncRNA signatures is rooted in their ability to mirror the complex biological reality of cancer pathogenesis. Individual lncRNAs typically regulate specific aspects of cancer biology through discrete molecular mechanisms. For instance, the lncRNA HULC promotes tumor growth in HCC through multiple pathways, while LINC00152 is associated with shorter overall survival [28]. Similarly, LINC01146 and LINC01554 have been identified as protective markers associated with longer survival [28]. However, when used individually, each lncRNA captures only a fragment of the complex pathological process.

Multi-lncRNA signatures integrate complementary biological information by simultaneously accounting for multiple cancer hallmarks. A well-constructed signature can capture processes as diverse as immune evasion (through immune-related lncRNAs), sustained proliferation (via cell cycle-regulating lncRNAs), therapy resistance (through lncRNAs modulating drug efflux or DNA repair), and metastatic potential (via lncRNAs regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition) [31] [28]. This comprehensive coverage of multiple cancer hallmarks provides a more holistic view of tumor behavior than any single marker can achieve.

Technical Advantages: Overcoming Analytical Limitations

Beyond biological considerations, multi-lncRNA signatures offer significant technical advantages. A critical innovation in this field is the development of relative expression ordering approaches that transform absolute expression values into relative rank relationships between lncRNA pairs. This method assigns a value of 1 when lncRNA A expression exceeds lncRNA B expression, and 0 for the opposite relationship [31]. This strategic approach effectively eliminates platform-specific technical variations and batch effects that often compromise single-marker analyses, as the relative ranking of genes within the same sample remains stable across different measurement platforms and normalization methods [31].

The robustness of multi-lncRNA signatures is further enhanced through statistical compensation mechanisms. When multiple markers are combined, measurement errors or biological variability in individual lncRNAs tend to average out, resulting in more stable prognostic estimates. This statistical resilience is particularly valuable in clinical settings where pre-analytical conditions and measurement techniques may vary.

Empirical Evidence: Performance Comparison in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Direct Performance Comparisons in HCC Studies

Multiple studies have directly compared the prognostic performance of multi-lncRNA signatures against single lncRNA markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. The results consistently demonstrate the superiority of multi-marker approaches across various performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Single vs. Multi-lncRNA Signatures in HCC

| Signature Type | Representative Markers | HR for Overall Survival | AUC (1-5 years) | Statistical Significance | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single lncRNA | LINC00152 | 2.524 (1.661-4.015) | Not reported | P = 0.001 | [28] |

| Single lncRNA | LINC00294 | 2.434 (1.143-3.185) | Not reported | P = 0.021 | [28] |

| Single lncRNA | LINC01094 | 2.091 (1.447-3.021) | Not reported | P < 0.001 | [28] |

| 2-lncRNA signature | PRRT3-AS1, AL031985.3 | Not reported | 0.73-0.79 (1-3 year ROC) | Independent prognostic factor | [29] |

| 5-lncRNA signature | BOK-AS1, AC099850.3, AL365203.2, NRAV, AL049840.4 | 2.78-2.88 (high vs low risk) | 0.677-0.778 (3-year) | P < 0.001 | [30] |

The data reveal that while single lncRNAs show significant hazard ratios (typically 2-2.5), their predictive power as standalone markers is limited. In contrast, multi-lncRNA signatures demonstrate not only significant hazard ratios but also superior predictive accuracy as measured by time-dependent AUC values. The 5-lncRNA signature developed by [30] maintained AUC values above 0.67 for 3-year survival prediction across both training and validation cohorts, indicating robust discriminative ability that single markers rarely achieve.

Validation Robustness Across Platforms and Populations

Multi-lncRNA signatures have consistently demonstrated stronger validation performance across independent datasets—a critical metric for clinical applicability. For instance, a 5-lncRNA signature for HCC was successfully validated in both training and testing cohorts with highly consistent hazard ratios (2.88 and 2.78, respectively) and maintained significant predictive power for 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival [30]. Similarly, a breast cancer study incorporating 10 machine learning algorithms to develop a 9-lncRNA signature demonstrated superior predictive performance across 17 independent validation cohorts, outperforming 95 previously published models [32].

This cross-platform robustness stems from the inherent stability of combining multiple markers. While individual lncRNA measurements may fluctuate due to technical factors, the combined signature captures a stable biological signal that persists across different patient populations and measurement platforms. This validation robustness represents a significant advantage over single markers, which often fail to replicate their initial promising results in independent cohorts.

Methodological Framework: Constructing and Validating Multi-lncRNA Signatures

Standardized Workflow for Signature Development

The development of robust multi-lncRNA signatures follows a systematic workflow that integrates bioinformatics, statistical optimization, and experimental validation. The following diagram illustrates this standardized process:

This workflow typically begins with data acquisition from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), which provide large-scale transcriptomic data with corresponding clinical information [33] [29] [30]. The subsequent differential expression analysis identifies lncRNAs significantly dysregulated in cancer tissues compared to normal controls, using thresholds such as |log2FC| > 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 [29].

For immune-related signatures, co-expression analysis with known immune genes further filters lncRNAs potentially involved in immune regulation, typically using correlation coefficients > 0.4-0.5 and p < 0.001 [29] [30]. The prognostic screening step applies univariate Cox regression to identify lncRNAs significantly associated with overall survival (p < 0.01) [29]. The most critical signature construction phase employs LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Cox regression with 10-fold cross-validation to select the optimal combination of lncRNAs while preventing overfitting [31] [33] [29].

Advanced Computational Approaches

Recent methodological advances have incorporated more sophisticated machine learning approaches to further enhance signature performance. One comprehensive study evaluated 101 combinations of 10 machine learning algorithms—including random survival forests, elastic net, CoxBoost, and survival SVMs—to identify optimal predictive models [32]. This multi-algorithm framework ensures that the final signature is robust and not dependent on the limitations of any single statistical method.

Another innovation involves the use of relative expression ordering of lncRNA pairs, which transforms continuous expression values into binary comparisons (0 or 1) based on which lncRNA in a pair is more highly expressed [31]. This approach eliminates the need for data normalization across platforms and reduces batch effects, significantly enhancing the clinical applicability of the resulting signatures.

Clinical Applications: Beyond Prognostic Prediction

Therapeutic Guidance and Treatment Selection

The true clinical value of multi-lncRNA signatures extends beyond mere prognosis to informing therapeutic decisions. Several studies have demonstrated that these signatures can predict response to specific treatments, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy. For example, a 9-lncRNA signature in breast cancer was shown to predict responses to paclitaxel chemotherapy, with low-risk patients potentially deriving greater benefit [32]. Similarly, in HCC, multi-lncRNA signatures have been correlated with immune cell infiltration patterns and expression of immune checkpoint molecules, suggesting potential utility in identifying patients most likely to respond to immunotherapy [30].

The relationship between lncRNA signatures and therapy response is biologically plausible, as lncRNAs regulate key drug resistance mechanisms. For instance, various lncRNAs have been identified to facilitate resistance to cisplatin, paclitaxel, 5FU, and other chemotherapeutic drugs through diverse mechanisms [31]. By capturing multiple resistance pathways simultaneously, multi-lncRNA signatures provide a more comprehensive assessment of therapeutic susceptibility than single markers.

Integration with Clinical Variables for Personalized Prediction

Multi-lncRNA signatures are frequently integrated with standard clinical parameters to create powerful predictive nomograms. These integrated tools provide personalized risk assessments that combine the molecular insights from lncRNAs with established clinical prognostic factors. For example, one HCC study combined a 2-lncRNA signature with clinicopathological features to develop a nomogram that showed satisfactory discrimination and consistency in predicting patient survival [29].

The development of such integrated models typically involves multivariate Cox regression analysis to confirm that the lncRNA signature provides prognostic information independent of clinical variables such as age, tumor stage, and histological grade [29] [30]. The resulting nomograms assign weighted points to each prognostic factor, enabling clinicians to calculate individual patient risk scores and tailor surveillance strategies and treatment intensities accordingly.

Technical Implementation: Research Reagent Solutions

The successful development and validation of multi-lncRNA signatures relies on a standardized set of research reagents and methodologies. The table below outlines essential resources for implementing these analyses.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for lncRNA Signature Development

| Category | Specific Resources | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) | Primary data source for discovery | Standardized RNA-seq data, clinical annotations |

| GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) | Independent validation | Multiple platforms, diverse populations | |

| ImmPort database | Immune-related gene annotations | 2,483 immune-related genes for co-expression analysis | |

| Computational Tools | R packages: limma, edgeR, glmnet, survival | Differential expression, LASSO regression, survival analysis | Statistical rigor, reproducibility |

| WGCNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis) | Identification of co-expression modules | Systems biology approach to network construction | |

| ssGSEA (single-sample GSEA) | Immune infiltration estimation | Quantification of tumor microenvironment composition | |

| Experimental Validation | qRT-PCR (TRIzol reagent, SYBR Green) | Confirmatory expression analysis | Gold standard for RNA quantification |

| RNA pull-down, ChIRP-MS | Protein interaction partner identification | Mapping lncRNA functional mechanisms | |

| LC-MS/MS platforms | Proteomic characterization | High-resolution identification of associated proteins |

These resources enable a comprehensive workflow from computational discovery to experimental validation. The computational tools facilitate the identification of candidate lncRNA signatures, while the experimental methods allow for confirmation of expression patterns and investigation of functional mechanisms. Importantly, the use of publicly available data resources enables independent validation—a critical step in verifying signature robustness.

The theoretical advantages and empirical evidence supporting multi-lncRNA signatures over single-marker approaches are compelling. By more accurately reflecting the biological complexity of cancer, providing robust prognostic stratification, and offering insights into therapeutic susceptibility, these multi-parameter signatures represent a significant advancement in cancer biomarker research. The standardized methodological frameworks and computational tools now available have matured to the point where clinical translation is increasingly feasible.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas. The integration of multi-omics data—combining lncRNA signatures with genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information—will provide even more comprehensive molecular portraits of tumors. The application of advanced machine learning algorithms will further enhance predictive accuracy and biological interpretability. Most importantly, prospective clinical validation studies are needed to firmly establish the utility of these signatures in routine clinical practice, ultimately fulfilling their promise to guide personalized cancer therapy and improve patient outcomes.

Building Robust Prognostic Models: Methodological Frameworks and Signature Development

For researchers developing and validating lncRNA-based prognostic signatures in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), selecting appropriate genomic data repositories is a critical first step. The The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) represent two foundational resources that offer complementary data types and access methodologies. TCGA provides highly standardized, harmonized genomic data from controlled cancer studies, while GEO serves as a versatile repository for diverse functional genomics datasets submitted by researchers worldwide [34]. Understanding their distinct architectures, data acquisition protocols, and preprocessing requirements is essential for constructing robust prognostic models.

The research context for HCC biomarker discovery presents specific challenges that influence database selection. HCC exhibits substantial molecular heterogeneity influenced by etiology, making the availability of well-annotated clinical cohorts crucial for validation. Both repositories contain HCC-relevant datasets, including the TCGA-LIHC project and numerous GEO series investigating HBV/HCV-related hepatocarcinogenesis, immune microenvironment interactions, and therapeutic responses [35] [36]. This guide provides an objective comparison of TCGA and GEO functionalities to inform strategic data acquisition for lncRNA signature validation.

Database Comparison: Architecture and Data Access

Table 1: Core Architectural Differences Between TCGA and GEO Databases

| Feature | TCGA (via GDC) | GEO |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Curated cancer genomics projects | Community-submitted functional genomics |

| Data Model | Hierarchical, standardized metadata | Flexible, submitter-defined organization |

| Data Types | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, clinical | Array-based, high-throughput sequencing |

| Access Levels | Open and controlled (dbGaP authorization) | Primarily open access |

| Reference Genome | GRCh38 harmonized [34] | Submitter-dependent (often hg19/GRCh38) |

| Data Processing | Standardized pipelines (GDC Harmonization) [34] | Raw data + submitter-processed files |

| HCC Examples | TCGA-LIHC project | GSE251942, GSE269528 [35] [36] |

TCGA, accessed through the Genomic Data Commons (GDC), employs a highly structured data model with mandatory clinical annotations and consistent genomic processing. All sequencing data undergoes harmonization to GRCh38, ensuring cross-project comparability [34]. This standardization significantly reduces preprocessing burden but offers less flexibility in data types. The GDC requires dbGaP authorization for controlled access to potentially identifiable genomic data, with access decisions made by NIH Data Access Committees based on research compatibility with data use limitations [37].

GEO utilizes a more flexible submission model where individual researchers determine data organization and processing methods. Submitters must provide both raw data (e.g., FASTQ files) and processed data (e.g., count matrices), with metadata captured via spreadsheet templates [38]. This flexibility enables access to diverse experimental designs but increases variability in data quality and processing methods. GEO generally operates as an open-access resource, though submitters must comply with human subject guidelines when applicable [38].

Data Acquisition Protocols and Methodologies

TCGA Data Retrieval Workflow

The GDC provides multiple interfaces for data retrieval, each optimized for different use cases. The GDC Data Portal offers a web-based interface for querying and downloading small volumes of files, while the GDC Data Transfer Tool is recommended for large-scale downloads such as entire TCGA-LIHC datasets [34]. For programmatic access, the GDC API supports advanced queries using SQL-like syntax for precise dataset filtering.

A typical TCGA data acquisition protocol for lncRNA signature validation involves:

- Project Identification: Identify relevant cases using the TCGA-LIHC (Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma) project

- Data Type Selection: Filter for transcriptomic profiling data (RNA-Seq)

- File Specification: Select BAM files for alignment-based analysis or FPKM/UQ-normalized counts for expression analysis

- Clinical Data Integration: Download corresponding clinical XML files for survival analysis and patient stratification

- Batch Effect Assessment: Examine technical batch variables using the GDC metadata

For controlled data access, researchers must first obtain dbGaP authorization through an NIH Data Access Committee, which reviews proposed research uses for consistency with data submission parameters [37].

GEO Data Retrieval and Submission Protocols

GEO data acquisition follows distinct pathways depending on whether researchers are downloading existing datasets or submitting new data:

Table 2: GEO Data Retrieval and Submission Methods

| Process | Primary Tools | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Download | GEO Accession Browser, SRA Toolkit | Supplemental files often contain processed data; Raw FASTQ via SRA |

| Data Submission | FTP transfer, metadata spreadsheet | Separate submissions per data type; Human data compliance required |

| Sequence Data | SRA Run Selector | Fastq preferred; BAM accepted but not preferred [38] |

| Metadata Requirements | GEO template spreadsheet | Detailed protocols, sample characteristics, data processing pipelines |

For HCC researchers validating lncRNA signatures, GEO datasets like GSE251942 (HBV-related HCC) provide valuable validation cohorts [35]. The acquisition protocol typically involves:

- Accession Search: Identify relevant datasets using GEO query tools

- Metadata Examination: Review experimental design and sample characteristics

- Processed Data Download: Obtain count matrices or normalized expression values

- Raw Data Access: Retrieve FASTQ files from SRA when reprocessing is necessary

- Clinical Data Integration: Merge expression data with available patient outcomes

For data submission to GEO – essential for publishing prognostic signature studies – researchers must prepare raw data files, processed data files, and complete metadata spreadsheets. The submission protocol requires FTP transfer to a personalized upload space followed by metadata file submission [38]. GEO specifically requires that processed data for sequencing studies have quantitative components (e.g., counts, FPKM, TPM) rather than alignment files (BAM/SAM), which are considered intermediary [38].

Experimental Design and Preprocessing Workflows

TCGA Data Preprocessing Framework