Virtual Screening for Protein-Ligand Binding Sites: Principles, Methods, and Best Practices in Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of virtual screening (VS) for identifying protein-ligand binding sites, a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery.

Virtual Screening for Protein-Ligand Binding Sites: Principles, Methods, and Best Practices in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of virtual screening (VS) for identifying protein-ligand binding sites, a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, exploring the core concepts of ligand-based and structure-based approaches. The scope extends to detailed methodological applications, including docking, pharmacophore modeling, and emerging machine learning techniques. It critically addresses common challenges and troubleshooting strategies, emphasizing protocol validation to avoid false positives. Finally, the article examines rigorous validation standards and comparative performance of different methods, including insights from blinded community challenges. The synthesis of these four intents provides a holistic guide for designing effective and reliable virtual screening workflows to accelerate lead identification and optimization.

The Foundations of Virtual Screening: Core Concepts and Strategic Goals

Virtual screening (VS) represents a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. It encompasses a set of in silico techniques used to evaluate massive libraries of chemical compounds and identify those with the highest potential to bind to a therapeutic protein target and modulate its biological function [1]. By leveraging computational power, VS addresses a fundamental challenge in drug discovery: efficiently navigating the vastness of chemical space to find promising starting points for drug development, thereby reducing the costs and time associated with experimental high-throughput screening (HTS) alone [2] [1].

The primary purpose of virtual screening is library enrichment—sifting through thousands to billions of compounds to select a much smaller subset enriched with putative active molecules [3]. This process enables researchers to focus their experimental efforts on the most promising candidates, dramatically improving research efficiency. A more focused application involves compound design, where detailed analysis of smaller compound series guides the optimization of lead molecules, ideally with quantitative predictions of binding affinity [3].

The Virtual Screening Paradigm: Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Approaches

Virtual screening methodologies are broadly classified into two complementary categories: ligand-based and structure-based methods. The choice between them often depends on the availability of prior knowledge about either known active compounds or the three-dimensional structure of the target protein.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

LBVS methods do not require a 3D structure of the target protein. Instead, they leverage the chemical information from known active ligands to identify new hits with similar structural or pharmacophoric features [3]. The core assumption is that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities.

- Molecular Similarity and Fingerprints: This approach involves computing molecular fingerprints, such as MACCS keys or ECFP4, for known active compounds and then screening large databases to find compounds with high similarity, typically measured by the Tanimoto coefficient [4]. This method is computationally fast and excellent for pattern recognition across diverse chemistries [3].

- Pharmacophore Modeling: A pharmacophore represents the essential spatial and electronic functional arrangements necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target. Pharmacophore models can be generated from a set of active ligands or from a protein binding site if known. These models are then used as 3D queries to screen compound libraries [4].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): Advanced methods like Quantitative Surface-field Analysis (QuanSA) construct physically interpretable binding-site models based on ligand structure and affinity data using multiple-instance machine learning. These can predict both ligand binding pose and quantitative affinity, providing valuable resolution for compound design [3].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

SBVS relies on the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, obtained through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy, or via computational predictions [3]. The most common SBVS technique is molecular docking.

- Molecular Docking: This process involves computationally predicting the preferred orientation (pose) of a small molecule when bound to a protein target. The workflow typically consists of two components: pose generation, which explores different conformations and orientations of the ligand within the binding site, and scoring, which ranks these poses based on an estimated binding affinity using a scoring function [5] [4].

- Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculations: Protocols like Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) represent the state-of-the-art for affinity prediction. They provide highly accurate calculations of binding free energies but are computationally very demanding, typically limiting their application to smaller sets of compounds [2].

- Handling Protein Flexibility: Advanced docking protocols, such as RosettaVS, incorporate receptor flexibility by allowing side-chain and limited backbone movement, which is critical for accurately modeling induced conformational changes upon ligand binding [5].

The Hybrid Approach: Combining LBVS and SBVS

Integrating ligand-based and structure-based methods often yields more reliable results than either approach alone [3]. Two common integration strategies are:

- Sequential Workflows: A rapid ligand-based filter (e.g., molecular similarity) is first applied to a large compound library to identify a promising subset. This subset then undergoes more computationally expensive structure-based refinement through docking [1] [3]. This conserves resources while improving precision.

- Parallel Screening and Consensus Scoring: Ligand- and structure-based screenings are run independently on the same library. Results are then combined through consensus scoring frameworks, which can either select top candidates from both lists or create a unified ranking by averaging scores. This strategy mitigates the limitations inherent in each method and increases confidence in selecting true positives [4] [3].

A Detailed Protocol for a Modern Virtual Screening Workflow

The following section outlines a robust, modern VS workflow that integrates both ligand- and structure-based methods, suitable for screening ultra-large chemical libraries.

Stage 1: Target Preparation and Binding Site Identification

Objective: To define a high-quality protein structure and its relevant ligand-binding pocket.

- Target Protein Selection and Structure Sourcing: The target protein is selected based on its therapeutic relevance. A 3D structural model is then acquired.

- Sources: The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the primary source for experimental structures [1]. For targets with no solved structure, computationally predicted models from AlphaFold2 can be used [6] [1]. Users should evaluate per-residue confidence scores (pLDDT) to assess local model quality, especially in the binding region [1].

- Structure Preparation: Using software like Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) or ChimeraX, the protein structure is prepared by:

- Removing water molecules and extraneous ligands.

- Adding hydrogen atoms and assigning appropriate atom charges (e.g., using the AMBER10_EHT forcefield) [4].

- Minimizing the structure to relieve steric clashes.

- Binding Site Identification: The ligand-binding site must be defined for docking.

- Preferred Method: If the site is known from literature or mutation studies, coordinates can be defined based on a co-crystallized ligand or conserved residues [1].

- Computational Prediction: If the site is unknown, use pocket detection algorithms like Fpocket [1], ConCavity, or 3DLigandSite [7]. Using multiple algorithms is encouraged for consensus [1].

Stage 2: Library Preparation and Initial Triage

Objective: To prepare a library of synthesizable small molecules and apply rapid filters to reduce its size.

- Library Curation: Compile a library of compounds for screening. These can be commercial vendor libraries, in-house collections, or enormous synthetically accessible spaces like Enamine REAL containing billions of molecules [2]. Canonical SMILES codes are typically used as the standard molecular representation.

- Prefiltering: The library is filtered based on physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, lipophilicity) to remove compounds with undesirable drug-like or lead-like properties [2]. Additionally, tools like SwissADME can be used to flag pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) and predict ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiles [4].

Stage 3: Active Learning-Guided Docking

Objective: To efficiently screen billions of compounds by docking only the most promising candidates.

- Machine Learning-Guided Docking: For ultra-large libraries, brute-force docking is computationally prohibitive. Instead, active learning protocols like AL-Glide are employed [2]. This method iteratively trains a machine learning model on a small subset of docked compounds. The model learns to predict docking scores and prioritizes the next batch of compounds for docking, dramatically reducing the number of full docking calculations required.

- High-Throughput Docking: The top-ranked compounds from the active learning step (e.g., 10-100 million) are subjected to a full docking calculation using programs like Glide [2], AutoDock Vina, or RosettaVS [5] [1]. At this stage, a standard docking protocol with a rigid receptor is often sufficient.

Stage 4: Rescoring and Hit Prioritization

Objective: To refine the ranking of top hits from the initial docking screen using more accurate, computationally intensive methods.

- Pose Refinement and Rescoring: The best-scoring compounds from initial docking are redocked and scored using more sophisticated methods. Glide WS (WaterScore), for example, uses explicit water information for more accurate pose prediction and scoring [2]. The RosettaVS protocol uses a high-precision (VSH) mode that includes full receptor flexibility [5].

- Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculations: The most promising few hundred to thousand compounds can be subjected to rigorous Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) calculations [2]. This physics-based method provides highly accurate binding affinity predictions and is a linchpin for selecting the most potent compounds.

- Consensus Scoring and MPO: Finally, a consensus approach is used to prioritize hits. This can combine scores from different methods (e.g., docking scores, FEP+ predictions, ligand-based similarity scores) [3]. The final list is then evaluated through Multi-Parameter Optimization (MPO), which balances predicted affinity with other critical properties like selectivity, ADME, and safety to identify the overall best candidates for experimental testing [3].

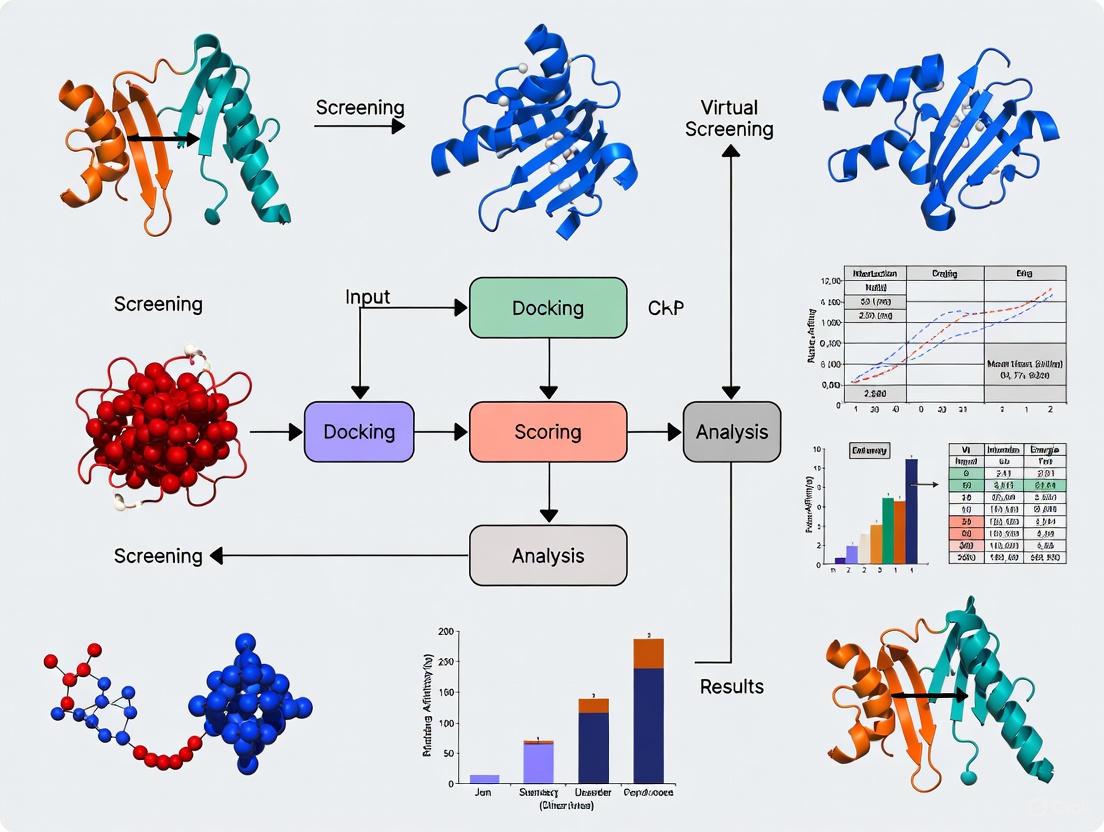

The following workflow diagram synthesizes this multi-stage protocol into a coherent, actionable pathway.

Virtual Screening Workflow

Performance Benchmarks and Impact

Modern VS workflows have demonstrated a dramatic improvement in hit rates compared to traditional methods. Schrödinger's Therapeutics Group reported that their modern VS workflow, leveraging ultra-large scale docking and ABFEP+ calculations, consistently achieved double-digit hit rates across multiple projects and diverse protein targets [2]. This is a significant increase from the typical 1-2% hit rates observed with traditional VS approaches.

Performance on standard benchmarks further validates these advanced methods. On the CASF2016 benchmark, the RosettaGenFF-VS scoring function achieved a top 1% enrichment factor (EF1%) of 16.72, significantly outperforming the second-best method (EF1% = 11.9) [5]. This indicates a superior ability to identify true binders early in the ranked list. Furthermore, Ligand-Transformer, a deep learning method, demonstrated strong correlation with experimentally measured binding affinities (Pearson’s R value of 0.57), which increased to 0.88 after fine-tuning on a specific target dataset [6].

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Modern Virtual Screening Methods

| Method / Platform | Key Metric | Result / Performance | Context / Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger VS Workflow [2] | Experimental Hit Rate | Double-digit hit rates (e.g., >10%) | Multiple diverse protein targets |

| RosettaGenFF-VS [5] | Enrichment Factor (Top 1%) | 16.72 | CASF-2016 Benchmarking Dataset |

| Ligand-Transformer [6] | Affinity Prediction Correlation (R) | 0.57 (0.88 after fine-tuning) | PDBbind2020 and EGFRLTC-290 datasets |

| Drugsniffer Pipeline [1] | Screening Throughput | ~40,000 compute hours for 3.7B molecules | Three SARS-CoV-2 protein targets |

A successful virtual screening campaign relies on a suite of software tools and databases. The table below catalogs key resources, categorizing them by their primary function in the workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Tool / Resource | Primary Function & Description |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [1] | Database of protein structure predictions generated by the AlphaFold2 AI system. | |

| Binding Site Detection | Fpocket [7] [1] | An open source protein pocket detection algorithm based on Voronoi tessellation and alpha spheres. |

| ConCavity [7] | Predicts binding sites by integrating evolutionary sequence conservation and 3D structural information. | |

| Compound Libraries | Enamine REAL [2] | An ultra-large library of billions of readily synthesizable compounds. |

| BIOFACQUIM [4] | A publicly available database of natural products and semi-synthetic compounds isolated and/or designed in Mexico. | |

| Ligand-Based Screening | RDKit [4] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for fingerprint generation, similarity calculations, and molecular operations. |

| ROCS [3] | A tool for rapid 3D shape-based superposition and screening to find molecules with similar shape and chemistry. | |

| Structure-Based Docking | Glide [2] [5] | A high-performance docking tool for predicting protein-ligand binding modes and scoring. |

| AutoDock Vina [5] [1] | A widely used, open-source docking program known for its speed and accuracy. | |

| RosettaVS [5] | An open-source docking and VS protocol that allows for receptor flexibility and uses the RosettaGenFF-VS force field. | |

| Advanced Scoring & FEP | Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) [2] | A state-of-the-art protocol for calculating absolute binding free energies with high accuracy. |

| Workflow & Automation | Drugsniffer [1] | An open-source, massively-scalable pipeline that integrates LBVS and SBVS for screening billions of molecules. |

| VirtualFlow [1] | An open-source platform designed for ultra-large virtual screening campaigns on high-performance computing clusters. |

Virtual screening has evolved from a supplementary tool to a critical driver in drug discovery. The integration of ligand-based and structure-based methods, coupled with machine learning acceleration and rigorous physics-based scoring, now enables researchers to reliably identify high-quality, potent hits from libraries of billions of compounds. The standardized workflows and robust benchmarks outlined in this document provide a framework for researchers to conduct effective virtual screening campaigns. As computational power and methodologies continue to advance, VS will play an increasingly pivotal role in accelerating the delivery of new therapeutics.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) is a foundational computational technique in modern drug discovery, employed when the three-dimensional structure of a biological target is unknown or unavailable. Operating on the principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical properties are likely to exhibit similar biological activities, LBVS uses known active compounds as templates to identify new hit molecules from vast chemical libraries [8] [9]. This approach stands in contrast to structure-based methods, which rely on the target's 3D structure, and is particularly valuable for targets like G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) or proteins where obtaining a high-resolution structure is challenging [8] [10]. The core of LBVS involves two essential components: a robust method for quantifying molecular similarity and a reliable scoring function to rank database compounds, enabling the effective discrimination of active from inactive molecules [8]. This Application Note provides a detailed overview of LBVS methodologies, supported by quantitative performance data, step-by-step experimental protocols, and practical toolkits for implementation, framed within the broader context of virtual screening for protein-ligand binding site research.

Key Methodologies and Performance Metrics

Ligand-based virtual screening encompasses a range of techniques, from simple 2D similarity searches to complex 3D shape and field comparisons. The choice of method often depends on the available ligand information and the desired balance between computational speed and accuracy.

Table 1: Core LBVS Methodologies and Their Characteristics

| Methodology | Molecular Representation | Similarity Measure | Key Advantages | Common Tools/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Fingerprint | Bit vectors encoding structural fragments | Tanimoto, Dice, Cosine | High speed, suitable for ultra-large libraries [11] | ECFP, FCFP, RDKit [11] |

| Pharmacophore | 3D arrangement of chemical features | Pattern matching | Incorporates chemical functionality logic [9] | Catalyst, Phase [9] |

| Shape-Based | Molecular volume/van der Waals surface | Volume overlap (e.g., Tanimoto) | Identifies scaffolds with similar shape but different chemistry [8] [9] | ROCS, VSFlow [8] [11] |

| Field-Based | Electrostatic, hydrophobic properties | Field similarity | Accounts for key interaction forces [9] | FieldScreen [9] |

| Graph-Based | Attributed graphs (nodes/edges as features) | Graph Edit Distance (GED) | Directly uses molecular topology, high interpretability [12] | Custom algorithms [12] |

The performance of LBVS approaches is quantitatively evaluated using several standard metrics derived from enrichment studies. These metrics assess a method's ability to prioritize active compounds early in the ranked list.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of LBVS Methods on Benchmark Datasets

| Method / Score | Dataset / Context | Performance Metric | Result / Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| HWZ Score [8] | 40 targets from DUD | Average AUC | 0.84 ± 0.02 |

| HWZ Score [8] | 40 targets from DUD | Hit Rate at top 1% | 46.3% ± 6.7% |

| HWZ Score [8] | 40 targets from DUD | Hit Rate at top 10% | 59.2% ± 4.7% |

| BINRF Model [13] | Structurally heterogeneous MDDR classes | Retrieval effectiveness | Significant improvement vs. baseline |

| Graph Edit Distance [12] | Multiple public datasets (e.g., DUD-E, MUV) | Classification accuracy | Highest ratios in bioactivity similarity |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: LBVS Workflow Using the VSFlow Toolkit

VSFlow is an open-source, command-line tool that integrates multiple LBVS methods, making it an excellent platform for standardized screening campaigns [11].

1. Database Preparation:

- Input: A compound library in SDF, SMILES, or other common formats.

- Standardization: Run

preparedbwith the-standardizeflag to apply MolVS rules, which include charge neutralization, salt removal, and optional tautomer canonicalization [11]. - Conformer Generation: For 3D screenings, use the

-conformersflag to generate multiple conformers for each database molecule using the RDKit ETKDGv3 method. Optimize conformers with the MMFF94 force field. - Fingerprint Calculation: Use the

-fingerprintflag to generate and store molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) within the database for fast 2D searches. - Output: A dedicated, high-speed

.vsdbdatabase file for subsequent screening.

2. Screening Execution:

- Substructure Search: Use the

substructuretool with a SMARTS pattern query. The tool uses RDKit'sGetSubstructMatches()to find all molecules containing the specified substructure. - Fingerprint Similarity Search: Use the

fpsimtool with a query molecule (SMILES) and a chosen fingerprint (e.g., Morgan fingerprint with 2048 bits and radius 2). The Tanimoto coefficient is a default similarity measure. The-simmapparameter can be added to generate a similarity map visualizing contributing atoms. - Shape-Based Screening: Use the

shapetool. The query molecule's conformers are aligned against all conformers of each database molecule using RDKit's Open3DAlign. Shape similarity (e.g., TanimotoDist) and 3D pharmacophore fingerprint similarity are calculated. A combined score (average of shape and pharmacophore similarity) is used to rank the results [11].

3. Results Analysis and Visualization:

- VSFlow can output results in various formats (SDF, Excel, CSV, PDF). The PDF output provides a convenient table of hits with 2D structures and highlighted substructure matches.

Protocol 2: Bayesian Inference Network with Reweighting

This protocol is designed for multi-reference similarity searching, especially effective for structurally heterogeneous active sets [13].

1. System Setup and Fingerprint Generation:

- Convert the molecular database (e.g., MDL Drug Data Report (MDDR)) and the set of known active reference structures into folded fingerprint vectors (e.g., 1024-element ECFC_4 fingerprints).

2. Fragment Reweighting:

- For each fragment

iin the fingerprint, calculate a reweighting factorrwf_ibased on its frequency in the set of active references [13]:rwf_i = F_fi / maxFwhereF_fiis the frequency of the fragment in the reference set andmaxFis the maximum fragment frequency in that set. - Calculate a new weight

nw_ifor each fragment:nw_i = w_i + rwf_iwherew_iis the original frequency of the fragment in a single reference structure. This process amplifies the importance of fragments common across many active molecules.

3. Network Execution and Ranking:

- Implement a Bayesian inference network with three node types: compound nodes (root), fragment nodes, and a reference structure node (leaf).

- Calculate the belief in each fragment node using a function like the Okapi belief function, incorporating the new fragment weights

nw_i. - The belief in the reference node is computed by aggregating the beliefs from its parent fragment nodes. The final belief score reflects the probability of a database compound having similar bioactivity to the reference set.

- Rank all database compounds in decreasing order of this probability score for experimental validation.

Workflow Visualization

LBVS Decision and Execution Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for LBVS

| Tool / Resource | Type / Availability | Primary Function in LBVS | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSFlow [11] | Open-source command-line tool | Integrated 2D/3D ligand-based screening | Allows customizable substructure, fingerprint, and shape-based screening from a unified interface. |

| RDKit [11] | Open-source cheminformatics library | Core chemistry engine | Provides foundational functions for molecule handling, fingerprint generation, and conformer generation used by many tools. |

| ROCS [8] [9] | Commercial software | Rapid 3D shape-based screening | Industry standard for shape and chemical overlay; uses Gaussian functions for molecular volume. |

| Database of Useful Decoys (DUD/DUD-E) [8] [12] | Public benchmark dataset | Method validation and benchmarking | Provides target-specific sets of known actives and property-matched decoys for retrospective VS performance tests. |

| MDDR Database [13] | Commercial activity database | Source of known active compounds | Used for building and testing similarity search models against pharmaceutically relevant targets. |

| SwissSimilarity [11] | Free web server | 2D/3D screening of public & vendor libraries | Provides easy access to similarity searching without local installation, useful for initial explorations. |

| Tenuifoliside B | Tenuifoliside B, CAS:139726-36-6, MF:C30H36O17, MW:668.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Deltatsine | Deltatsine, CAS:92631-66-8, MF:C25H41NO7, MW:467.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Ligand-based virtual screening remains a powerful and efficient strategy for hit identification in the absence of a protein structure. Its success is anchored in the careful selection of molecular representation and similarity metrics, as evidenced by the strong performance of modern shape-based and graph-based methods on standardized benchmarks. The availability of robust, open-source toolkits like VSFlow lowers the barrier to entry for implementing these protocols. When integrated into a broader drug discovery workflow—either as a primary screening method or in a hybrid approach combining ligand- and structure-based insights—LBVS significantly accelerates the identification of novel, promising scaffolds for further optimization.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) is a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug design (CADD), functioning as a computational technique to identify novel drug candidates by predicting how small molecules interact with a three-dimensional protein target [14]. The core principle involves molecular docking, which computationally simulates the binding of a ligand to a protein receptor, predicting the stable conformation of the complex and its binding affinity [15]. This process is fundamental to understanding protein-ligand interactions, which are driven by non-covalent forces such as hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects [14]. By leveraging the known 3D structure of a protein, SBVS allows researchers to rapidly prioritize compounds with a high likelihood of binding from immense chemical libraries, significantly accelerating the pace of early-stage drug discovery and providing crucial mechanistic insights for rational drug design [14] [16].

Key Principles of Molecular Docking

Physicochemical Basis of Binding

Protein-ligand binding is a complex process governed by non-covalent interactions and thermodynamics. The formation of a stable protein-ligand complex is driven by a favorable change in the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔGbind), which is determined by the enthalpy (ΔH) from the formation of chemical bonds and the entropy (ΔS) related to the system's randomness [14]. The key non-covalent interactions that contribute to binding include:

- Hydrogen Bonds: Polar electrostatic interactions between a hydrogen atom donor and an acceptor, with a strength of approximately 5 kcal/mol. They are highly specific and crucial for biomolecular recognition [14].

- Ionic Interactions: Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged ionic pairs, providing highly specific binding forces within the protein's binding pocket [14].

- Van der Waals Interactions: Non-specific forces arising from transient dipoles in electron clouds when atoms are in close proximity, with weaker strength of about 1 kcal/mol [14].

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Entropy-driven associations where nonpolar molecules or regions aggregate to minimize disruptive interactions with the aqueous solvent [14].

Molecular Recognition Models

The mechanisms by which proteins and ligands recognize and bind to each other are conceptualized through three primary models:

- Lock-and-Key Model: Proposes that the binding partners are pre-complementary in shape, with rigid interfaces that fit perfectly without conformational changes. This model represents an entropy-dominated process [14].

- Induced-Fit Model: Suggests that the protein binding site undergoes conformational adjustments to accommodate the ligand, adding flexibility to the original lock-and-key hypothesis [14].

- Conformational Selection Model: Postulates that ligands selectively bind to pre-existing conformational states from an ensemble of protein substates, with the population of the selected state increasing upon binding [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Interactions in Protein-Ligand Binding

| Interaction Type | Strength (kcal/mol) | Nature | Role in Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | ~5 | Electrostatic, directional | Specificity and stability |

| Ionic Interactions | 5-10 | Electrostatic, charged | Strong, specific attraction |

| Van der Waals | ~1 | Non-specific, transient | Close-contact stabilization |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Variable | Entropy-driven | Burial of non-polar surfaces |

Current Methodologies and Tools

The SBVS landscape encompasses both traditional physics-based approaches and emerging deep learning methods, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Traditional Docking Approaches

Traditional docking tools like AutoDock Vina and Glide SP employ scoring functions based on empirical or physics-based energy terms to evaluate binding poses, combined with search algorithms to explore the conformational space [15]. These methods have proven robust and reliable, with Glide SP particularly noted for producing physically plausible poses with high validity rates (above 94% across benchmark datasets) [15].

Deep Learning-Enhanced Docking

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have introduced several paradigms that are transforming the docking field [15]:

- Generative Diffusion Models (e.g., SurfDock): Demonstrate superior pose prediction accuracy, achieving RMSD ≤ 2Å success rates exceeding 70% across diverse datasets [15].

- Regression-Based Models: Directly predict binding affinities or poses but often struggle with producing physically valid conformations [15].

- Hybrid Methods: Combine traditional conformational searches with AI-driven scoring functions, offering a balanced approach between accuracy and physical plausibility [15].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Docking Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-valid) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Docking | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina | Moderate to High | High (≥94%) | Standard docking with high physical plausibility |

| Generative Diffusion | SurfDock, DiffBindFR | High (≥70%) | Moderate (40-63%) | Maximum pose accuracy |

| Regression-Based | KarmaDock, QuickBind | Variable | Low to Moderate | Rapid screening when speed is critical |

| Hybrid Methods | Interformer | Moderate | Moderate to High | Balanced approach for diverse targets |

Integrated Screening Platforms

Modern drug discovery increasingly utilizes multi-stage platforms that combine multiple methodologies:

- HelixVS: Implements a three-stage workflow combining classical docking (AutoDock QuickVina 2) with deep learning-based affinity scoring (RTMscore) and optional binding mode filtering. This approach demonstrates a 2.6-fold higher enrichment factor than Vina alone with significantly faster screening speeds [17].

- SPRINT: A vector-based approach using protein language models for ultra-fast screening, capable of querying the entire human proteome against 6.7 billion compounds in minutes, enabling proteome-scale virtual screening [18].

Experimental Protocols for SBVS

Standard Virtual Screening Workflow

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive structure-based virtual screening procedure suitable for identifying potential ligands for a protein target with a known or modeled 3D structure.

Step 1: Target Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling. For modeled structures, validate quality using Ramachandran plots (e.g., with PROCHECK) and Discrete Optimized Protein Energy (DOPE) scores [16].

- Remove native ligands, water molecules, and ions not involved in coordination.

- Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states of residues appropriate for physiological pH using tools like AutoDockTools.

- For homology modeling, use Modeller with a high-identity template structure (>50% sequence identity recommended) [16].

Step 2: Binding Site Identification

- Define the binding site coordinates based on:

- Known co-crystallized ligand positions

- Prediction using binding site detection tools like LABind, which utilizes graph transformers and cross-attention mechanisms to predict binding sites in a ligand-aware manner [19]

- Literature and mutational data on critical residues

- Generate a grid box centered on the binding site with sufficient dimensions to accommodate ligand flexibility (typically 20-25Ã… in each direction) [20].

Step 3: Compound Library Preparation

- Retrieve compounds from databases such as ZINC, ChemDiv, or in-house collections.

- Prepare ligands by:

- Converting to appropriate format (e.g., PDBQT) using OpenBabel

- Generating 3D coordinates and optimizing geometry with force fields (e.g., MMFF94 with 2500 steps) [20]

- enumerating possible tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH

Step 4: Molecular Docking

- Perform docking with selected software (AutoDock Vina recommended for balance of speed and accuracy) [20] [15].

- Key Parameters:

- Exhaustiveness: 8-16 (higher for more accurate sampling)

- Number of poses: 10-20 per compound

- Energy range: 3-4 kcal/mol

- Execute parallel docking runs to maximize throughput.

Step 5: Post-Docking Analysis

- Analyze top-ranking compounds based on:

- Binding affinity (normalized docking scores)

- Pose stability and complementarity to binding site

- Key interactions with critical residues (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts)

- Cluster results based on structural similarity (e.g., Tanimoto similarity) to ensure chemical diversity [20].

- Visualize promising complexes to verify binding modes.

Step 6: Validation and Prioritization

- Validate docking protocol by redocking known ligands and calculating RMSD to native pose (≤2.0Å acceptable).

- Apply machine learning classifiers to distinguish active from inactive compounds using chemical descriptors [16].

- Filter compounds based on drug-like properties (Lipinski's Rule of Five) and ADMET predictions.

- Select 20-50 top-ranked diverse compounds for experimental testing or further computational analysis.

Advanced Protocol: Integrating Machine Learning

For enhanced screening efficacy, incorporate machine learning at multiple stages [16] [17]:

QSAR Pre-screening:

- Train machine learning models (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on known active and inactive compounds.

- Use molecular descriptors (e.g., from PaDEL-Descriptor) or fingerprints (MACCS keys) as features [20] [16].

- Screen large compound libraries with the trained model before docking to enrich for potentially active compounds.

Multi-Stage Screening with Deep Learning:

- Stage 1: Rapid pre-screening with fast docking tools (e.g., QuickVina 2) to reduce library size [17].

- Stage 2: Re-score top poses (1000-5000 compounds) with more accurate deep learning-based affinity predictors (e.g., RTMscore in HelixVS) [17].

- Stage 3: Apply interaction pattern filters to select compounds with specific binding features (e.g., key hydrogen bonds).

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: SBVS workflow showing the sequential steps from target preparation to hit identification.

Diagram 2: Multi-stage screening platform integrating traditional docking with deep learning.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Traditional Docking | Protein-ligand docking and scoring | Good balance of speed and accuracy; widely used [20] |

| Glide SP | Traditional Docking | High-accuracy docking | Excellent physical validity; commercial software [15] |

| SurfDock | Deep Learning (Generative) | Pose prediction via diffusion models | High pose accuracy but moderate physical validity [15] |

| LABind | Binding Site Prediction | Predicts binding sites for small molecules and ions | Ligand-aware; generalizes to unseen ligands [19] |

| HelixVS | Integrated Platform | Multi-stage screening with DL scoring | 2.6x higher EF than Vina; high throughput [17] |

| SPRINT | Ultra-Fast Screening | Proteome-scale screening using PLMs | Screens billions of compounds in minutes [18] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Molecular descriptor calculation and manipulation | Essential for compound preprocessing and analysis [20] |

| PDBBind | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding data | Benchmarking and training data source [21] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Publicly accessible database of commercially available compounds | Source of compounds for screening [16] |

| ESMFold | Structure Prediction | Protein structure prediction from sequence | Generates structures when experimental ones unavailable [19] |

Structure-Based Virtual Screening represents a powerful methodology that continues to evolve with advancements in computational power and algorithmic innovation. The integration of deep learning approaches with traditional physics-based docking has created a new generation of tools that offer enhanced accuracy and efficiency in identifying potential drug candidates. As these methods improve in their ability to generalize across diverse protein targets and novel binding pockets, SBVS will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating drug discovery pipelines and addressing challenging therapeutic targets. The protocols and resources outlined herein provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing SBVS in their drug discovery efforts, from initial target selection to the identification of promising hit compounds for experimental validation.

Library Enrichment versus Quantitative Compound Design

Within virtual screening (VS) for drug discovery, two distinct computational objectives guide research: library enrichment and quantitative compound design [3]. Library enrichment focuses on the rapid filtering of ultra-large chemical libraries to identify a subset of compounds with a higher probability of containing active molecules, thereby improving the efficiency of subsequent experimental testing [3] [22]. In contrast, quantitative compound design involves the detailed analysis of smaller compound series to predict binding affinity with high precision, directly guiding the optimization of lead compounds [3]. This application note delineates the key differences, methodologies, and protocols for these two objectives, providing a structured framework for their application in protein-ligand binding site research.

Table 1: Core Comparison of Key Objectives in Virtual Screening.

| Feature | Library Enrichment | Quantitative Compound Design |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify a subset of compounds enriched with potential actives from a very large library [3] | Guide the optimization of compounds by quantitatively predicting binding affinity and properties [3] |

| Chemical Space | Very large (billions of compounds) [23] [5] | Focused series of compounds [3] |

| Typical Output | Ranking or score for prioritizing compounds [3] | Quantitative prediction of affinity (e.g., pKi, IC50) [3] |

| Key Methodologies | Ligand-based similarity search, structure-based docking, pharmacophore screening [9] [3] [22] | Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), 3D-QSAR, advanced scoring functions [3] [2] |

Library Enrichment: Protocols and Applications

The goal of library enrichment is to efficiently navigate vast chemical spaces, often containing billions of molecules, to increase the concentration of potential hits in the final set selected for experimental testing [3] [22]. This is particularly valuable for novel targets with few known ligands.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening for Library Enrichment

This protocol is used when the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable but known active ligands exist [3] [22].

- Ligand Preparation: Collect structures of known active ligands from databases like ChEMBL or BindingDB [22]. Generate representative 3D conformations for each ligand using conformer ensemble generators like OMEGA or RDKit's ETKDG method, ensuring coverage of their conformational space [22].

- Query Model Creation:

- For Similarity Search: Calculate molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) for the active ligands [23] [9].

- For Pharmacophore Screening: Generate a pharmacophore model that defines the spatial arrangement of steric and electronic features necessary for biological activity. This can be done manually from a single active ligand or automatically from a set of aligned actives using tools like ROCS or Phase [9] [3] [22].

- For Shape-Based Screening: Use the 3D shape and electrostatic properties of a known active ligand as a query using tools like ROCS [9] [3].

- Database Screening: Screen the virtual library (e.g., ZINC, Enamine REAL) against the query model. This involves calculating similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient for fingerprints) or aligning library compounds to the pharmacophore/shape query [9] [3].

- Hit Prioritization: Rank library compounds based on their similarity or fit to the query model. Select the top-ranking compounds for experimental testing or further refinement with structure-based methods [3] [22].

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Docking for Ultra-Large Library Enrichment

This protocol employs the protein's 3D structure to screen libraries of up to billions of compounds [5] [2].

- Protein and Library Preparation:

- Obtain a high-quality protein structure (experimental or predicted). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and defining the binding site [22].

- Prepare the virtual screening library by generating 3D conformers, tautomers, and protonation states at a physiological pH (e.g., 7.4) using tools like LigPrep or MolVS [22].

- Machine Learning-Guided Docking: Due to the computational cost of docking billions of compounds, use an active learning approach [2].

- Dock a small, diverse subset of the library (e.g., a few million compounds) using a docking program like Glide or RosettaVS [5] [2].

- Use the docking scores from this subset to train a machine learning (ML) model that acts as a fast proxy for the docking scoring function [2].

- The ML model rapidly scores the entire ultra-large library, identifying the most promising compounds for full docking calculations [2].

- Pose Prediction and Scoring: Perform a full, more precise docking calculation on the top several million compounds identified by the ML model. Rank the final compounds based on their docking scores [5] [2].

Quantitative Data and Performance

The success of library enrichment is often measured by the hit rate—the percentage of tested compounds that show experimental activity. Modern workflows using ultra-large libraries and advanced docking have demonstrated a significant increase in hit rates.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Modern vs. Traditional Virtual Screening Workflows.

| Metric | Traditional VS Workflow | Modern VS Workflow (with Ultra-Large Libraries) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Library Size | Hundreds of thousands to a few million compounds [2] | Several billion compounds [5] [2] |

| Typical Hit Rate | 1-2% [2] | Double-digit percentages (e.g., 14%, 44%) reported [5] [2] |

| Key Enabling Technologies | Standard molecular docking (e.g., Glide, AutoDock Vina) [5] [2] | Active learning-guided docking, scalable screening platforms (e.g., OpenVS, RosettaVS) [5] [2] |

Diagram 1: A modern workflow for library enrichment, leveraging active learning to efficiently screen ultra-large chemical spaces.

Quantitative Compound Design: Protocols and Applications

Once lead compounds are identified, the focus shifts to quantitative compound design. This objective aims to accurately predict the binding affinity of smaller, more focused compound series to guide chemical modification and optimization [3].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3: Absolute Binding Free Energy Perturbation (ABFEP+) Calculations

This state-of-the-art, physics-based protocol provides highly accurate predictions of absolute binding free energies, enabling the ranking of diverse chemotypes without a reference compound [2].

- System Preparation: Build simulation-ready systems for the protein-ligand complexes of interest. This includes placing the complex in a water box, adding ions to neutralize the system, and defining appropriate force field parameters for the ligand [2].

- Alchemical Transformation Setup: Define the "alchemical" pathway that computationally decouples the ligand from its environment in the bound (protein-ligand complex) and unbound (ligand in solution) states [2].

- Molecular Dynamics Sampling: Perform extensive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to sample the configurations along the alchemical pathway. This requires significant computational resources, often utilizing multiple GPUs per ligand [2].

- Free Energy Analysis: Use methods like thermodynamic integration (TI) or Bennett's acceptance ratio (MBAR) to calculate the absolute binding free energy (ΔG) from the simulation data. The predicted ΔG values can be directly compared to experimental affinities (e.g., Ki, IC50) [2].

Protocol 4: 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QuanSA) Modeling

This ligand-based method constructs an interpretable model of the binding site based on the 3D structures and affinity data of known ligands [3].

- Data Set Curation: Compile a set of ligands with known binding affinities (e.g., pKi) for the target. Ensure chemical diversity but within a definable series [3].

- Ligand Alignment: Align the 3D structures of the ligands into a hypothesized bioactive conformation within the same binding mode. This can be done using field-based or shape-based alignment tools [3].

- Field Calculation and Model Building: Calculate molecular interaction fields (e.g., electrostatic, hydrophobic, shape) around the aligned ligands. Use multiple-instance machine learning to correlate these field points with the experimental affinity data and build a predictive model [3].

- Prediction and Design: Use the resulting QuanSA model to predict the affinity of new, untested compounds. The model can also provide visual guidance on where to add specific functional groups to enhance potency [3].

Quantitative Data and Performance

Quantitative design methods are validated by their high correlation with experimental results and their ability to guide the discovery of potent compounds.

Table 3: Performance of Quantitative Design Methods.

| Method | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Binding FEP+ (ABFEP+) | Accurately predicted double-digit nanomolar and micromolar binders from virtual screening; enabled double-digit hit rates in fragment screening [2] | Identifying and optimizing hits from ultra-large screens; ranking diverse chemotypes [2] |

| Hybrid Model (QuanSA + FEP+) | Lower Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) for pKi prediction than either method alone in a study on LFA-1 inhibitors [3] | Lead optimization for an orally available small molecule program [3] |

| RosettaGenFF-VS | Top 1% Enrichment Factor (EF1%) of 16.72 on the CASF-2016 benchmark, outperforming other scoring functions [5] | Structure-based virtual screening and pose prediction [5] |

Diagram 2: A workflow for quantitative compound design, employing high-accuracy methods like FEP+ and 3D-QSAR to optimize lead series.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for implementing the protocols described in this application note.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Large Chemical Libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL) | Provides access to billions of readily synthesizable compounds for virtual screening [23] [2]. | Protocol 1, Protocol 2 |

| Conformer Generator (e.g., OMEGA, RDKit ETKDG) | Generates representative 3D conformations for small molecules, crucial for most VS methods [22]. | Protocol 1, Protocol 2 |

| Docking Software (e.g., Glide, RosettaVS, AutoDock Vina) | Predicts the binding pose and scores the interaction of a ligand within a protein's binding site [5] [9] [2]. | Protocol 2 |

| Active Learning Platform (e.g., Active Learning Glide) | Uses machine learning to efficiently screen ultra-large libraries by approximating docking scores [2]. | Protocol 2 |

| Free Energy Perturbation Software (e.g., FEP+) | Calculates relative or absolute binding free energies with high accuracy for lead optimization [3] [2]. | Protocol 3 |

| 3D-QSAR Software (e.g., QuanSA) | Builds predictive models based on ligand 3D structure and affinity data to guide compound design [3]. | Protocol 4 |

| Protein Structure Prediction (e.g., AlphaFold3) | Generates 3D protein models for targets with no experimentally solved structure, enabling structure-based methods [3] [24]. | Protocol 2 |

| Spartioidine | Spartioidine, CAS:520-59-2, MF:C18H23NO5, MW:333.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Disialyllactose | Disialyllactose, CAS:18409-15-9, MF:C34H56N2O27, MW:924.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the structured pipeline of virtual screening (VS) for protein-ligand research, the preliminary phases of bibliographic investigation and systematic data collection are critical determinants of success. These pre-screening steps establish the biological and computational context necessary for robust virtual screening campaigns, directly influencing the reliability of binding site prediction, ligand docking, and hit identification [25] [14]. Proper execution of these foundational activities enables researchers to contextualize their target within existing literature, select appropriate computational methods based on known structural and bioactivity data, and assemble high-quality datasets for method validation [26]. This protocol details the essential methodologies for conducting comprehensive bibliographic research and curating specialized data collections framed within protein-ligand binding site research, providing researchers with a standardized framework for enhancing virtual screening outcomes through rigorous preparatory work.

Bibliographic Research Methodology

Establishing Biological Context and Identifying Knowledge Gaps

The initial phase of bibliographic research focuses on comprehensively understanding the target protein's biological role and current research landscape. Begin by querying major biological databases using standardized search terms related to your target protein, associated biological pathways, and known or putative ligands. systematically extract and document key information including the protein's natural substrates, physiological function, involvement in disease pathways, and any existing structural data [25] [14]. This process should specifically identify whether the target represents a novel binding site with limited characterization or a well-studied site with extensive structural and ligand information available, as this distinction will directly influence subsequent virtual screening strategies [19].

Critical objectives during this phase include identifying known active compounds for the target, cataloging available experimental structures (both apo and holo forms), and recognizing characterized binding pockets versus potential allosteric sites [3]. For proteins of unknown function, leverage homology modeling approaches by identifying structurally similar proteins with characterized binding sites, though remain cognizant that binding function does not always correlate with structural similarity [25]. Document all findings systematically, noting confidence levels based on experimental evidence and highlighting specific knowledge gaps that virtual screening aims to address.

Methodological Selection Through Literature Analysis

Bibliographic research must extend beyond biological context to inform computational methodology selection. Analyze recent literature to identify successful virtual screening approaches applied to similar target classes, noting whether structure-based, ligand-based, or hybrid methods demonstrated superior performance [3] [17]. Specific attention should be paid to the performance of different docking programs and scoring functions for your target family, as method efficacy varies significantly across protein classes [5] [26]. For instance, some targets may benefit from methods that incorporate explicit side-chain flexibility, while others perform adequately with rigid receptor docking.

When evaluating methodological literature, prioritize studies that provide validation metrics on standardized benchmark datasets to facilitate direct comparison between approaches. Document the specific benchmarking results, including enrichment factors, pose prediction accuracy, and computational requirements, as these metrics will inform your own method selection and expected performance [5] [17]. This analysis should culminate in a preliminary virtual screening strategy that specifies the planned computational approaches, justified by their demonstrated efficacy with similar target proteins and data availability.

Data Collection and Curation Protocols

Structural Data Acquisition and Preparation

High-quality structural data forms the foundation of structure-based virtual screening campaigns. Initiate structural data collection by querying the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for experimental structures of your target protein, prioritizing structures based on resolution (preferably <2.5Ã…), completeness of the binding site region, and the presence of relevant bound ligands [14] [26]. When multiple structures are available, create a structural ensemble that represents conformational diversity, particularly if the protein exhibits flexibility in binding site residues [5]. For targets lacking experimental structures, utilize high-accuracy computational models from AlphaFold or ESMFold, but apply strict quality metrics focusing on the predicted confidence scores (pLDDT) specifically within the binding site region [3].

Table 1: Essential Structural Data Resources for Virtual Screening

| Resource Name | Data Content | Key Applications | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Experimental 3D structures of proteins and complexes | Binding site characterization, Molecular docking | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| PDBbind | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data | Scoring function validation, Benchmarking | http://www.pdbbind.org.cn/ |

| AlphaFold Database | Computationally predicted protein structures | Targets without experimental structures | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

Structural preparation represents a critical step preceding virtual screening. Employ standardized preprocessing workflows that include adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states for ionizable residues consistent with physiological pH, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks [5] [17]. For binding site definition, prefer crystallographic ligand positions when available, or utilize binding site prediction tools like LABind for novel or uncharacterized sites [19]. Document all preprocessing steps meticulously to ensure reproducibility, as subtle variations in protonation states or side-chain orientations can significantly impact docking outcomes.

Bioactivity Data Compilation and Curation

Bioactivity data provides essential information for validating virtual screening methods and understanding structure-activity relationships. systematically extract bioactivity data from public repositories using structured queries for your target protein, collecting measured values (Kd, Ki, IC50) with associated experimental conditions and metadata [26] [27]. Implement rigorous data curation procedures including standardization of chemical structures, normalization of affinity units, and removal of duplicate entries or compounds with potential assay interference characteristics.

Table 2: Key Bioactivity Databases for Virtual Screening Research

| Database | Primary Content | Scale (as of 2021) | Virtual Screening Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Curated bioactivity data from literature | 17 million+ activities, 14,000+ targets | Ligand-based screening, Model training |

| BindingDB | Binding affinity data | 2.2 million+ data points, 8,000+ targets | Method validation, Benchmarking |

| PubChem BioAssay | High-throughput screening data | 280 million+ bioactivity data points | Decoy selection, Model training |

| BindingMOAD | Protein-ligand structures with affinity data | 15,964 complexes with affinity data | Structure-activity relationship analysis |

During data compilation, explicitly distinguish between binding measurements (Kd, Ki) and functional activity measurements (IC50, EC50), as these represent different biological phenomena with distinct structure-activity relationships [26]. For virtual screening validation, prioritize the creation of a high-confidence active compound set comprising molecules with unambiguous binding evidence and potency exceeding a defined threshold (typically <10μM) [27]. This curated active set will serve as crucial reference data for assessing the enrichment capability of your virtual screening protocol.

Benchmark Dataset Preparation for Method Validation

Benchmark datasets provide standardized frameworks for evaluating virtual screening performance and comparing different computational methods. Select appropriate benchmark sets based on your target characteristics and virtual screening objectives, with the Directory of Useful Decoys Enhanced (DUD-E) representing the most widely used resource for assessing screening power [26] [17]. For targets not represented in existing benchmark sets, construct customized validation datasets by pairing your curated active compounds with carefully selected decoy molecules that mimic the physicochemical properties of actives but differ in 2D topology to avoid artificial enrichment [27].

The Comparative Assessment of Scoring Functions (CASF) benchmark provides a complementary resource specifically designed for evaluating scoring power, ranking power, docking power, and screening power through a curated set of 285 high-quality protein-ligand complexes [5] [26]. Implement rigorous dataset splitting strategies including random splits, scaffold-based splits, and time-based splits to assess method performance under different validation scenarios and minimize overoptimistic performance estimates due to dataset bias [27]. Document the precise composition and splitting methodology for all benchmark datasets to ensure experimental reproducibility and facilitate meaningful comparison with literature results.

Integrated Workflow and Research Reagent Solutions

Logical Workflow for Pre-Screening Activities

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for bibliographic research and data collection, highlighting the sequential relationships between major activities and decision points:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational resources and their functions in the pre-screening workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pre-Screening Activities

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Pre-Screening | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | PDB, PDBbind, AlphaFold Database | Source of protein structures for docking and binding site analysis | Prioritize resolution <2.5Ã… for experimental structures; Assess pLDDT >80 for AF2 models |

| Bioactivity Repositories | ChEMBL, BindingDB, PubChem BioAssay | Source of ligand activity data for validation and benchmarking | Implement strict curation for standardized values and unambiguous target assignment |

| Benchmark Platforms | DUD-E, CASF-2016, MUV | Standardized datasets for method validation and comparison | Select benchmarks matching target class; Use multiple datasets for robust assessment |

| Binding Site Prediction | LABind, DeepSurf, P2Rank | Identification and characterization of binding sites | Particularly crucial for novel targets without known binding sites [19] |

| Pre-processing Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel, Schrödinger Protein Prep | Structure standardization, protonation, and optimization | Ensure consistency in preprocessing across all structures |

| Cheminformatics | SMILES, Molecular fingerprints, Descriptors | Compound representation and similarity analysis | Standardize representation for consistent data integration |

| Shizukanolide | Shizukanolide, CAS:70578-36-8, MF:C15H18O2, MW:230.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Coromandaline | Coromandaline, CAS:68473-86-9, MF:C15H27NO4, MW:285.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Concluding Remarks

The pre-screening phases of bibliographic research and data collection establish the essential foundation for successful virtual screening campaigns focused on protein-ligand binding sites. Through systematic implementation of the protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and effectiveness of subsequent computational screening efforts. The integrated workflow connecting comprehensive literature review with rigorous data curation ensures that virtual screening approaches are appropriately contextualized within existing biological knowledge and validated against relevant benchmark standards. As virtual screening methodologies continue to advance, with emerging technologies like AI-accelerated platforms [5] [17] and sequence-based predictors [28] enhancing screening efficiency, the fundamental importance of robust preliminary research and high-quality data collection remains unchanged. By adhering to these standardized pre-screening protocols, research teams can maximize the probability of identifying genuine protein-ligand interactions while efficiently allocating computational resources to the most promising screening methodologies.

Virtual Screening in Action: A Guide to Key Methods and Tools

Virtual screening is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, providing a cost-effective strategy to identify promising hit compounds from vast chemical libraries. Within this field, ligand-based techniques offer powerful solutions for when detailed target protein structures are limited, but knowledge of active ligands exists. These methods operate on the fundamental principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical characteristics are likely to exhibit similar biological activities. This application note details three core ligand-based methodologies—pharmacophore modeling, shape similarity screening, and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling—framing them within the context of virtual screening for protein-ligand binding sites. We provide detailed protocols, quantitative performance data, and practical guidance for their implementation in a research setting aimed at identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic agents.

Pharmacophore Modeling

Theoretical Foundation

A pharmacophore is an abstract description of the steric and electronic features essential for a molecule to interact with a specific biological target and trigger its pharmacological response [29] [30]. It represents the key molecular interaction capabilities, such as hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic (H) regions, charged groups (positive: PI, negative: NI), and aromatic rings (AR), rather than specific chemical structures [30]. Pharmacophore modeling is a versatile technique used for virtual screening, de novo drug design, and optimizing lead compounds by identifying critical interaction points required for binding [29].

There are two primary approaches for developing pharmacophore models:

- Ligand-Based Modeling: Built from a set of active ligands known to interact with the target. The model identifies the common chemical features and their spatial arrangement responsible for the shared biological activity, even in the absence of a protein structure [30].

- Structure-Based Modeling: Derived from the 3D structure of a protein-ligand complex. The model is generated based on the observed interactions between the ligand and the binding site, such as hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, and hydrophobic patches [30].

Recent advancements are leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance pharmacophore applications. For instance, DiffPhore, a knowledge-guided diffusion model, has been developed for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in predicting binding conformations and virtual screening [31].

Application Protocol: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation and Virtual Screening

Objective: To create a ligand-based pharmacophore model and use it for virtual screening to identify novel potential actives from a chemical database.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Software for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Dataset of Active Ligands | A curated set of 20-30 known active compounds with diverse structures but common biological activity against the target. |

| Chemical Database | Large collections of small molecules (e.g., ZINC20, PubChem) for virtual screening. |

| Conformational Ensemble | A collection of low-energy 3D conformations for each ligand, accounting for molecular flexibility. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Software like PHASE, Catalyst, or MoViES that can generate and validate pharmacophore hypotheses. |

| Computational Resources | Standard workstation or computing cluster for running conformational analysis and database searches. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Ligand Preparation and Conformational Analysis:

- Collect a structurally diverse set of known active ligands.

- Prepare their 3D structures using a molecular builder, ensuring correct protonation states at physiological pH.

- For each ligand, generate a conformational ensemble that adequately represents its accessible 3D space. This is typically done using algorithms like Monte Carlo or molecular dynamics within software such as MacroModel or ConfGen [32].

Common Pharmacophore Identification:

- Superimpose the multiple conformational ensembles of the active ligands.

- The software algorithm will identify common chemical features (e.g., HBA, HBD, hydrophobic centers) and their spatial relationships shared across the active compounds.

- A set of pharmacophore hypotheses will be generated, each consisting of a specific arrangement of these features.

Hypothesis Validation and Selection:

- Validate the generated pharmacophore models using a dataset of known active and inactive compounds.

- The best hypothesis is selected based on its ability to correctly discriminate between active and inactive molecules (high sensitivity and specificity) [30]. Statistical metrics like the Güner-Henry score or enrichment factors are used for this purpose.

Database Screening and Hit Identification:

- Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen a large chemical database.

- The screening process involves searching for molecules in the database that can adopt a conformation matching all or the most critical features of the pharmacophore model.

- Compounds that successfully map to the pharmacophore are retrieved as potential hits for further experimental testing.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol:

Figure 1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Screening Workflow.

Shape Similarity Screening

Theoretical Foundation

Shape similarity screening is based on the concept that the biological activity of a ligand is strongly influenced by its three-dimensional shape and volume, which must complement the geometry of the target's binding pocket [32]. This method uses a known active ligand as a query to identify molecules with similar shapes from large chemical libraries, under the assumption that similar shapes are likely to lead to similar biological effects.

The similarity between two molecules, A and B, is typically quantified using a volume overlap metric. A fundamental equation is:

Shape Similarity (Sim~AB~) = V~A∩B~ / V~A∪B~

where V~A∩B~ is the shared volume between the two molecules and V~A∪B~ is their total combined volume [32]. This yields a score between 0 (no overlap) and 1 (perfect overlap). In practice, approximations are used for speed, such as summing pairwise atomic overlaps normalized by the largest self-overlap [32].

Modern implementations go beyond "pure shape" and incorporate chemical feature encoding (e.g., atom types, pharmacophore features), which consistently produces better results in virtual screening by ensuring that the aligned volumes also share similar chemical functionalities [32].

Application Protocol: Shape-Based Virtual Screening

Objective: To use a known active compound as a shape-based query to screen a compound database and rank hits based on shape and feature similarity.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Software for Shape Similarity Screening

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Query Ligand | A known active compound, ideally from a high-resolution complex structure, used as the shape template. |

| Multi-Conformer Database | A screening library where each compound is represented by an ensemble of low-energy 3D conformations. |

| Shape Screening Software | Tools like Schrödinger's Shape Screening, OpenEye ROCS, or Cresset FieldAlign that perform rapid 3D alignment and scoring. |

| High-Performance Computing | Cluster or multi-core workstation, as shape screening is computationally intensive. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Query Preparation:

- Select a known high-affinity ligand as the query. An experimental structure from a protein-ligand complex is ideal.

- If the bound conformation is unknown, generate a single, representative low-energy conformation or a small conformational ensemble for the query.

Database Preparation:

- Prepare the virtual screening database by generating multiple low-energy 3D conformations for each compound in the library. This step is crucial to account for the flexibility of database molecules and ensure a fair shape comparison.

Shape-Based Alignment and Scoring:

- For each conformer in the database, the algorithm generates numerous trial alignments to the query by matching triplets of atoms or pharmacophore features [32].

- The top alignments are refined to maximize the volume overlap.

- Each database molecule is assigned a similarity score based on the best alignment found. This score can be based on pure shape, atom-type-based shape, or pharmacophore-feature-based shape.

Hit Analysis and Prioritization:

- Rank the database compounds based on their shape similarity scores.

- Visually inspect the top-ranking hits to verify the quality of the alignments and the chemical reasonableness of the proposed binding mode.

- Select a diverse subset of high-scoring compounds for further computational analysis or experimental validation.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Shape Screening Approaches (Enrichment Factor at 1%) [32]

| Target | Pure Shape | Element-Based | Pharmacophore-Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 10.0 | 27.5 | 32.5 |

| CDK2 | 16.9 | 20.8 | 19.5 |

| DHFR | 7.7 | 11.5 | 80.8 |

| ER | 9.5 | 17.6 | 28.4 |

| Thrombin | 1.5 | 4.5 | 28.0 |

| Average | 11.9 | 17.0 | 33.2 |

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below:

Figure 2: Shape-Based Virtual Screening Workflow.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

Theoretical Foundation

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a computational approach that constructs mathematical models to correlate the biological activity of a set of compounds with quantitative descriptors representing their structural and physicochemical properties [33] [34]. The fundamental assumption is that the biological activity of a compound can be expressed as a function of its molecular structure:

Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [33]

QSAR models are critical for predicting the activity of new compounds, optimizing lead series, and understanding the structural features governing potency. Several types of QSAR exist:

- 2D-QSAR: Uses descriptors derived from the 2D molecular graph (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices).

- 3D-QSAR (e.g., CoMFA, CoMSIA): Correlates biological activity with 3D molecular fields (steric, electrostatic) calculated from aligned ligand structures [33].

- GQSAR: Considers contributions of molecular fragments or substituents at specific positions [33].

Application Protocol: Developing and Validating a QSAR Model

Objective: To build a statistically robust and predictive QSAR model for a series of compounds with known biological activity and use it to predict the activity of new analogs.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Software for QSAR Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Curated Dataset | A set of compounds (typically >20) with consistently measured biological activity (e.g., IC~50~, K~i~). |

| Molecular Descriptor Software | Tools like DataWarrior, PaDEL-Descriptor, or Dragon to calculate thousands of molecular descriptors. |

| Chemoinformatics Software | Platforms like R (with caret, pls packages), KNIME, or WEKA for data preprocessing, model building, and validation. |

| Applicability Domain Definition | A method to define the chemical space of the model to ensure reliable predictions only for structurally similar compounds. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Data Collection and Curation:

- Assemble a dataset of compounds with reliable and quantitative biological activity data.

- Curate the structures: remove duplicates, standardize tautomers, and check for errors.

Descriptor Calculation and Dataset Division:

- Calculate a wide range of molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, geometrical) for all compounds in the dataset.

- Split the dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) for model development and a test set (20-30%) for external validation. This split should be representative of the structural and activity space.

Variable Selection and Model Construction:

- Perform variable selection on the training set to identify the most relevant descriptors and avoid overfitting. Methods include stepwise selection, genetic algorithms, or LASSO.

- Construct the model using statistical or machine learning methods. Common techniques include:

Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Assess the model's robustness on the training set using techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation. Key metrics include Q² (cross-validated R²) and Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation (RMSE~CV~).

- External Validation: Use the untouched test set to evaluate the model's predictive power. Key metrics include R²~pred~ and RMSE~pred~ [33].

- Y-Scrambling: Perform permutation tests to rule out chance correlation.

Model Application and Prediction:

- Use the validated model to predict the activity of new, untested compounds.

- Ensure that the new compounds fall within the applicability domain of the model to trust the predictions.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below:

Figure 3: QSAR Model Development and Application Workflow.

While each technique is powerful individually, integrating them can yield superior results. A common strategy is to use faster ligand-based methods (pharmacophore or shape) for the initial screening of large libraries, followed by more precise structure-based methods (like molecular docking) or predictive QSAR models for refining and prioritizing hits [3]. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of each method, increasing confidence in the final selection of compounds for synthesis and experimental testing [3].