A Comprehensive Guide to RFE Feature Selection for High-Dimensional Biological Data

This article provides a complete protocol for applying Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to high-dimensional biological datasets, a common challenge in genomics, transcriptomics, and drug discovery.

A Comprehensive Guide to RFE Feature Selection for High-Dimensional Biological Data

Abstract

This article provides a complete protocol for applying Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to high-dimensional biological datasets, a common challenge in genomics, transcriptomics, and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational theory of RFE, details step-by-step methodologies for implementation, and addresses common pitfalls with advanced optimization strategies. Furthermore, it offers a rigorous framework for validating and benchmarking RFE performance against other feature selection techniques, empowering scientists to build more robust, interpretable, and accurate predictive models for biomedical applications.

Understanding RFE: The Essential Primer for Biomedical Data Analysis

What is RFE? Core Principles and the Greedy Backward Elimination Process

Core Principles of Recursive Feature Elimination

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper-style feature selection algorithm designed to identify the most relevant features in a dataset by recursively pruning less important attributes [1] [2]. The core principle operates on a simple yet powerful iterative mechanism: it constructs a model using all available features, ranks the features by their importance, eliminates the least significant ones, and repeats this process on the remaining features until only the desired number of features remains [3] [4].

This method is model-agnostic, meaning it can work with any supervised learning estimator that provides feature importance scores, such as coefficients from linear models or feature importance attributes from tree-based models [3] [2]. A key advantage of RFE over univariate filter methods is its ability to account for feature interactions because the importance ranking is derived from a multivariate model that considers all features simultaneously during each iteration [1] [4].

The Greedy Backward Elimination Algorithm Explained

The term "greedy" in the backward elimination process refers to the algorithm's local optimization approach at each step—it makes the optimal choice at each iteration by removing the feature with the lowest importance, without considering whether this choice will be optimal for the entire process [5].

The RFE algorithm follows these specific steps with mathematical precision:

- Initialization: Begin with the full set of features, ( F = f1, f2, ..., f_n ), and specify the number of features to select, ( k ), or a stopping criterion [3].

- Model Training & Importance Ranking: Train the chosen estimator on the current feature set ( F ). Compute the importance scores for each feature, creating a ranking vector ( R = r1, r2, ..., r_m ), where ( m ) is the current number of features [3] [6].

- Feature Pruning: Remove the bottom ( s ) features, where ( s ) is the "step" parameter (( s \geq 1 ) for absolute count, ( 0.0 < s < 1.0 ) for percentage) [3].

- Recursion: Repeat steps 2 and 3 on the pruned feature set ( F' ) until the number of remaining features equals ( k ) [3] [6].

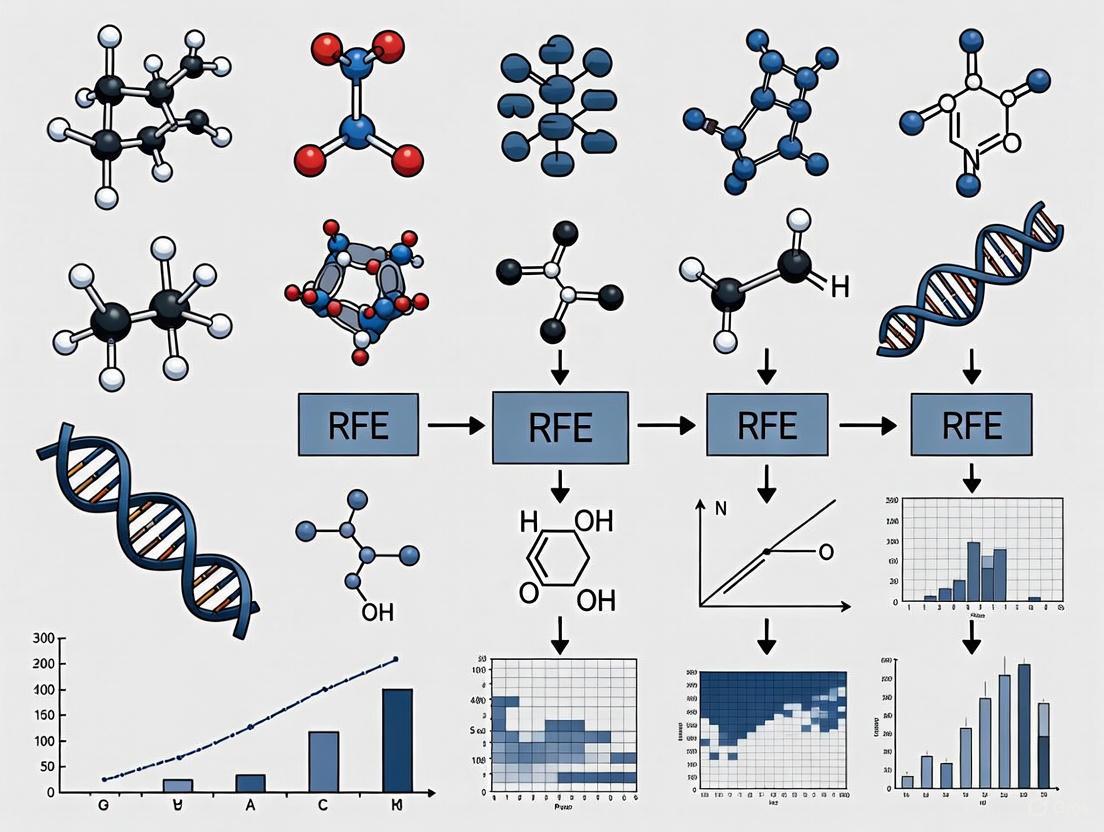

This process is visualized in the following workflow:

Table 1: Key Hyperparameters for Tuning RFE

| Hyperparameter | Description | Default Value | Impact on Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

n_features_to_select |

Absolute number (int) or fraction (float) of features to select. | None (selects half) |

Determines the stopping point for the elimination process [3]. |

step |

Number/percentage of features to remove per iteration. | 1 |

Higher values speed up computation but risk premature removal of important features [3]. |

estimator |

The core model used for importance calculation. | N/A (Required parameter) | The choice of model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) directly influences the feature ranking [3] [4]. |

RFE Protocol for High-Dimensional Biological Data

High-dimensional biological datasets (e.g., genomics, proteomics) present unique challenges, including small sample sizes relative to the number of features, multicollinearity, and noisy variables [7]. The following protocol is adapted for such data, incorporating cross-validation to enhance robustness.

Protocol: RFE with Cross-Validation for Robust Feature Selection

Objective: To identify a stable subset of predictive features from high-dimensional biological data while mitigating overfitting.

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RFE Implementation

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Base Estimator | A model that provides feature importance scores. | LinearSVC (for linear data), RandomForestClassifier (for non-linear data) [4]. |

| Computing Environment | Software for algorithm execution and data handling. | Python with scikit-learn library [3] [2]. |

| Data Normalization Tool | Standardizes features to have zero mean and unit variance. | sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScaler [4]. |

| Cross-Validation Schema | Framework for robust performance estimation and parameter tuning. | RepeatedStratifiedKFold [2]. |

Methodology:

Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize the data (e.g., using

StandardScaler) to ensure features are on a comparable scale, which is critical for the importance calculations of many estimators [4]. - Split the data into training and hold-out test sets.

- Standardize the data (e.g., using

Parameter Initialization:

- Choose a Base Estimator: Select an algorithm appropriate for your data. For genomic data with correlated predictors, tree-based models like Random Forest are often suitable [7].

- Define RFE Parameters: Set

stepto 1 for fine-grained elimination. Then_features_to_selectcan be initially set toNoneto let RFECV determine the optimum.

Execution with Cross-Validation (RFECV):

- Use

RFECV(RFE with built-in cross-validation) to automatically find the optimal number of features [4]. - Fit the

RFECVobject on the training data. The internal cross-validation ensures that the selected feature subset generalizes well.

# Create a pipeline with scaling and RFECV pipeline = Pipeline([ ('scaler', StandardScaler()), ('rfecv', RFECV( estimator=RandomForestClassifier(nestimators=100, randomstate=42), step=1, cv=5, # 5-fold cross-validation scoring='accuracy' )) ])

# Fit the pipeline pipeline.fit(Xtrain, ytrain) # The optimal features are now selected Xtrainselected = pipeline.transform(Xtrain) Xtestselected = pipeline.transform(Xtest)- Use

Validation and Analysis:

- Train a final model on the training data with the selected features and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set.

- Analyze the selected features for biological relevance (e.g., pathway analysis for selected genes).

Performance Analysis and Comparative Evaluation

The effectiveness of RFE is highly dependent on the choice of the underlying estimator and the data structure. Research on high-dimensional omics data (integrating 202,919 genotypes and 153,422 methylation sites) highlights that while standard RFE can identify strong causal variables, its performance can be impacted by the presence of many correlated variables [7].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of RFE Performance with Different Estimators

| Criterion | Linear Models (e.g., SVM, Logistic Regression) | Tree-Based Models (e.g., Random Forest) |

|---|---|---|

| Importance Metric | Model coefficients (coef_) [3]. |

Gini impurity or mean decrease in impurity (feature_importances_) [7]. |

| Handling Correlated Features | May arbitrarily assign importance to one feature from a correlated group. | More robust; can distribute importance among correlated features [7]. |

| Advantages | Computationally efficient for very high-dimensional data. | Effective at capturing non-linear relationships and interactions [7]. |

| Limitations | Assumes linear relationships between features and target. | Computationally more intensive; importance can be biased towards high-cardinality features [7]. |

Advanced Applications in Biological Research

RFE has been successfully applied across various biological domains:

- Bioinformatics: Selecting informative genes for cancer classification and prognosis from microarray or RNA-seq data, helping to improve diagnostic accuracy and personalize treatment plans [1].

- Integrated Omics Analysis: RFE can be used to select key features from multiple integrated data types (e.g., genomics, epigenomics) to model complex traits, though careful interpretation is needed in the presence of widespread correlation [7].

- Biomarker Discovery: Identifying a minimal set of proteins or metabolites from high-throughput proteomic or metabolomic data that robustly predict disease status or treatment response.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has established itself as a premier feature selection methodology within the realm of biological data science, particularly for tackling the acute challenges posed by high-dimensional omics data. The foundational RFE algorithm operates on a simple yet powerful greedy search strategy: it starts by building a predictive model with the complete set of features, ranks the features based on their importance, eliminates the least important features, and then recursively repeats this process on the reduced feature set until a predefined stopping criterion is met [8]. This backward elimination process provides a more thorough assessment of feature importance compared to single-pass approaches because feature relevance is continuously reassessed after removing the influence of less critical attributes [8].

Biological datasets, especially those from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics studies, frequently present a "small n, large p" problem, where the number of features (p) drastically exceeds the number of samples (n) [9] [10]. This high-dimensional environment, often referred to as the "curse of dimensionality," challenges many conventional machine learning algorithms by increasing the risk of overfitting, extending computation times, and complicating model interpretation [9]. RFE directly addresses these challenges by systematically reducing dimensionality while preserving the most biologically relevant features. Furthermore, unlike feature extraction methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) that transform original features into new composite variables, RFE maintains the original biological features, thereby preserving interpretability—a crucial consideration for biomedical researchers seeking to identify actionable biomarkers or therapeutic targets [8] [10].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of RFE Variants

The efficacy of RFE and its variants has been extensively validated across diverse biological applications and datasets. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies, providing empirical evidence for the utility of RFE in biological research.

Table 1: Performance of RFE-Based Frameworks in Classification Tasks

| Application Domain | RFE Variant | Key Classification Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer Mortality Classification | U-RFE (Union with RFE) | F1_weighted: 0.851, Accuracy: 0.864, MCC: 0.717 | [11] |

| Motor Imagery Recognition in BCI | H-RFE (Hybrid-RFE) | Accuracy: 90.03% (SHU), 93.99% (PhysioNet) | [12] |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Subtyping | Workflow with Univariate Filter + RFE | Effective dimensionality reduction with maintained performance | [9] |

| Cancer Classification from Gene Expression | DBO-SVM (Nature-inspired + RFE) | Accuracy: 97.4-98.0% (binary), 84-88% (multiclass) | [13] |

Table 2: Benchmarking RFE Variants Across Domains (Adapted from [8])

| RFE Variant | Predictive Accuracy | Feature Set Size | Computational Cost | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE with Random Forest | Strong | Large | High | General-purpose biological data |

| RFE with XGBoost | Strong | Large | High | Large-scale omics data |

| Enhanced RFE | Moderate (minimal loss) | Substantially reduced | Moderate | Interpretability-focused studies |

| RFE with Linear SVM | Variable | Small to moderate | Low | Linearly separable biological features |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that RFE-based approaches consistently achieve high classification performance while significantly reducing dimensionality. The U-RFE framework, which combines feature subsets from multiple base estimators, achieved an impressive F1-weighted score of 0.851 and accuracy of 0.864 in classifying multicategory causes of death in colorectal cancer, with the Stacking model outperforming individual classifiers [11]. Similarly, in brain-computer interface applications, the H-RFE method combining random forest, gradient boosting, and logistic regression achieved approximately 90-94% classification accuracy while using only about 73% of the total channels, substantially reducing computational burden without sacrificing performance [12].

Detailed RFE Experimental Protocols

Core RFE Protocol for Biological Data

The standard RFE protocol follows a systematic workflow that can be adapted to various biological data types. The following diagram illustrates this core process:

Protocol Steps:

Initialization: Begin with the complete dataset containing all molecular features (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) and corresponding phenotypic labels (e.g., disease state, treatment response).

Model Training: Train an initial predictive model using the entire feature set. Common choices include:

Feature Ranking: Calculate feature importance scores specific to the chosen model:

Feature Elimination: Remove the bottom k features (typically 5-20% of remaining features per iteration) based on the importance ranking [7].

Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 using the reduced feature set until reaching a predefined stopping criterion:

- Target number of features reached

- Model performance falls below a threshold

- All features have been ranked and eliminated sequentially [8]

Output: Return the final optimal feature subset that maintains or improves predictive performance with minimal features.

Advanced Hybrid RFE Protocol (H-RFE)

For complex biological datasets with correlated features, a hybrid approach often yields superior results. The H-RFE protocol integrates multiple estimators to generate a more robust feature ranking:

Protocol Steps:

Parallel RFE Execution:

- Run RFE independently with three different estimators: Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and Logistic Regression (LR) [12].

- For each estimator, obtain feature importance scores and rankings.

Weight Normalization:

- Normalize the importance scores from each estimator to a common scale (e.g., 0-1) to ensure comparability.

- Calculate accuracy-based weighting factors for each estimator based on cross-validation performance [12].

Feature Ranking Aggregation:

- Compute weighted composite scores for each feature:

Composite_score = w_R * Score_RF + w_G * Score_GBM + w_L * Score_LRwhere wR, wG, w_L are accuracy-derived weights [12]. - Generate a final feature ranking based on composite scores.

- Compute weighted composite scores for each feature:

Iterative Elimination:

- Perform backward elimination using the aggregated feature rankings.

- At each iteration, evaluate model performance with the current feature subset using cross-validation.

Optimal Subset Selection:

- Select the feature subset that maximizes performance while minimizing size.

- Validate the selected features on held-out test data.

Visualization of RFE Workflows and Biological Integration

Hybrid-RFE Methodology for Biological Data

The H-RFE approach integrates multiple machine learning perspectives to overcome limitations of single-estimator RFE, particularly valuable for biological data with complex correlation structures:

Biological Domain Knowledge Integration

Integrating biological domain knowledge with RFE represents a cutting-edge approach that moves beyond purely statistical feature selection:

Integration Protocol:

Statistical Pre-filtering:

- Apply univariate correlation filters to remove features non-correlated with outcome variables [9].

- Use biological context to inform statistical thresholds rather than arbitrary cutoffs.

Biological Knowledge Incorporation:

- Integrate external biological data from sources such as:

- Use biological knowledge to:

- Group functionally related features

- Prioritize features with established biological relevance

- Validate statistical findings with mechanistic plausibility

Integrated Ranking:

- Combine statistical importance scores with biological relevance scores.

- Use weighted scoring that reflects both statistical power and biological significance.

Biological Validation:

- Assess whether selected feature subsets correspond to coherent biological pathways or processes.

- Compare with known disease mechanisms or established biomarkers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RFE Implementation

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in RFE Protocol | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | R Statistical Software, Python | Primary computational environment for implementing RFE algorithms | General bioinformatics analysis [9] [8] |

| RFE-Specific Packages | caret (R), scikit-learn (Python), feseR (R) | Provide pre-built implementations of RFE and related feature selection methods | Streamlining RFE workflow development [9] |

| Biological Databases | Gene Ontology, KEGG, Reactome, TCGA, GEO | Source of biological domain knowledge for integrative feature selection | Biological interpretation and validation [10] |

| Machine Learning Libraries | randomForest (R), kernlab (R/SVM), XGBoost | Provide estimator algorithms for the RFE core process | Model training and feature importance calculation [9] [14] [8] |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2 (R), matplotlib (Python), LocusZoom | Visualization of feature importance rankings and selection process | Results communication and interpretation [7] |

| High-Performance Computing | Linux servers, parallel processing frameworks | Handling computational demands of RFE on high-dimensional biological data | Large-scale omics data analysis [7] |

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Successful implementation of RFE for biological data requires careful consideration of several technical aspects:

Handling Correlated Features in Biological Data

Biological datasets frequently contain highly correlated features (e.g., genes in the same pathway, linkage disequilibrium in SNPs). Traditional RFE can struggle with correlated features, as it may arbitrarily select one feature from a correlated group while discarding others that might be biologically relevant [7]. mitigation strategies include:

- Ensemble RFE Approaches: Combine feature rankings from multiple algorithms with different sensitivities to correlation [12].

- Pre-filtering: Use correlation filters before applying RFE to reduce redundancy [9].

- Block Elimination: Eliminate groups of correlated features together based on biological knowledge [10].

Parameter Optimization

Key parameters that require optimization in RFE protocols:

- Elimination Step Size: The number/percentage of features to remove at each iteration. Smaller step sizes (e.g., 1-5% of features) are more computationally intensive but can yield better results [7].

- Stopping Criterion: Determining the optimal number of features to retain. Common approaches include:

- Performance plateau detection (stop when performance improvement falls below threshold)

- Predefined feature count based on biological constraints

- Elbow method using performance vs. feature count plots [8]

- Model-Specific Tuning: Optimizing hyperparameters of the underlying estimator (e.g., mtry in Random Forest, C in SVM) at each iteration [7].

Computational Efficiency Strategies

RFE can be computationally demanding, especially with large biological datasets. Efficiency improvements include:

- Parallelization: Run iterations in parallel when possible [7].

- Approximate Methods: Use feature importance approximations that don't require full model retraining [14].

- Staged Implementation: Apply faster filter methods first to reduce feature space before applying RFE [9].

Recursive Feature Elimination represents a powerful and flexible framework for addressing the dimensionality challenges inherent in modern biological datasets. Its strength lies in combining robust feature selection with maintained interpretability—a crucial advantage for biological discovery. The continuous evolution of RFE through hybrid approaches, biological knowledge integration, and specialized implementations for specific data types ensures its ongoing relevance in computational biology and biomedical research. As biological datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, RFE-based methodologies will remain essential tools for extracting biologically meaningful insights from high-dimensional data.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), introduced by Guyon et al., is a powerful wrapper feature selection technique designed to identify optimal feature subsets by recursively considering smaller and smaller sets of features [15] [16]. The algorithm was originally developed in the context of gene selection for cancer classification and has since become a cornerstone method in the analysis of high-dimensional biological data [16]. Its backward elimination approach, which builds models and removes the least important features iteratively, makes it particularly valuable for bioinformatics research where the number of predictors (e.g., genes, proteins, SNPs) often far exceeds the number of samples [15] [16]. The RFE framework is especially effective because it accommodates changes in feature importance induced by changing feature subsets, which is crucial when handling correlated biomarkers in complex biological systems [15] [17].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

Algorithm Definition and Workflow

RFE operates as a backward selection procedure that begins by building a model on the entire set of predictors and computing an importance score for each one [15]. The least important predictor(s) are then removed, the model is re-built, and importance scores are computed again [15]. This recursive process continues until a predefined number of features remains or until a performance threshold is met [17]. The subset size that optimizes the performance criteria is used to select the predictors based on the importance rankings, and this optimal subset then trains the final model [15].

Key Characteristics

- Greedy Approach: RFE employs a greedy search strategy, making locally optimal choices at each iteration by removing the least important features [15].

- Model-Based Ranking: Features are ranked based on importance scores derived from a machine learning model, making the selection process tailored to the specific algorithm [15] [17].

- Resampling Compatibility: The selection process should be resampled similarly to fundamental tuning parameters from a model, with external resamples used to estimate the appropriate subset size [15].

Original RFE Protocol: Step-by-Step Breakdown

Detailed Procedural Steps

The original RFE algorithm follows these sequential steps:

- Train Initial Model: Build a model using all available features in the dataset [15] [17].

- Compute Feature Importance: Calculate importance scores for all features using model-specific metrics (e.g., coefficients for linear models, permutation importance for tree-based models) [15] [17].

- Rank Features: Sort features based on their importance scores in descending order [15].

- Eliminate Least Important Features: Remove the bottom-ranked feature or features (e.g., bottom 10%) [15] [16].

- Retrain Model: Rebuild the model using the remaining feature subset [15] [17].

- Iterate Process: Repeat steps 2-5 until the desired number of features is reached or a stopping criterion is met [15] [17].

RFE Process Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for Implementing RFE in Biological Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SVM with Linear Kernel | Original algorithm by Guyon et al.; provides feature coefficients for ranking [16] [14] | Scikit-learn (Python), e1071 (R) |

| Random Forest | Alternative model; handles non-linear relationships; provides feature importance scores [15] [18] | RandomForest (R), scikit-learn (Python) |

| RFE-Specific Packages | Pre-implemented RFE algorithms with cross-validation and performance tracking [17] | Scikit-learn RFE/RFECV, Feature-engine |

| High-Performance Computing | Manages computational demands of multiple model training iterations [9] | Cluster computing, parallel processing |

Implementation Considerations for Biological Data

Model Selection and Compatibility

Not all models can be paired with the RFE method, and some benefit more from RFE than others [15]. The original implementation used Support Vector Machines (SVMs) with linear kernels, which provide natural feature coefficients for ranking [16] [14]. However, RFE has been successfully adapted to various algorithms:

- Random Forest: Particularly benefits from RFE because tree ensembles tend not to exclude variables from prediction equations, making post hoc pruning valuable [15].

- Linear Models: Multiple linear regression, logistic regression, and linear discriminant analysis cannot be used when predictors exceed samples unless predictors are first filtered [15].

- Non-linear SVMs: Require modified RFE approaches since direct feature coefficients are not available [14].

Handling Biological Data Complexities

High-dimensional biological data presents unique challenges that RFE must address:

- Multicollinearity: In tree-based models, importance scores can be diluted when highly correlated predictors are present, as the importance gets distributed across correlated features [15]. Pre-filtering correlated features (e.g., absolute pairwise correlations < 0.50) is recommended [15].

- Feature Ranking Consistency: In bioinformatics applications, rankings should be reasonably consistent across resamples, though some variability is expected, particularly for lower-ranked features [15].

- Performance Metrics: For biological classification tasks, area under the ROC curve (AUC) is commonly used to evaluate subset performance during the elimination process [15] [16].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Benchmarking RFE Performance

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of RFE on Biological Datasets

| Dataset | Original Features | Optimal Subset Size | Performance Metric | Result with Full Set | Result with RFE Subset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease Data [15] | ~500 predictors | 377 (unfiltered), ~30 (filtered) | ROC AUC | Baseline | Comparable (0.064 AUC increase) |

| Breast Cancer Genomics [16] | 1M+ SNPs | Varies | Classification Accuracy | Varies with linear models | Improved with non-linear interactions |

| Gene Expression (GSE5325) [9] | 27,648 genes | 1,697 (after filtering) | ER Status Classification | Not specified | Maintained with 80% feature reduction |

| Synthetic Data with Parity [16] | Varies with irrelevant features | Relevant features only | Learning Efficiency | Poor with irrelevant features | Restored classification performance |

Correlation Filtering Protocol

Based on findings from Parkinson's disease data analysis [15]:

- Calculate Correlation Matrix: Compute pairwise correlations between all features.

- Set Threshold: Define maximum allowable correlation (e.g., |r| < 0.50).

- Iterative Removal:

- Identify feature pairs exceeding threshold

- Remove one feature from each highly correlated pair

- Prioritize removal of features with lower importance scores

- Verify Filtering: Ensure all remaining features have absolute correlations below threshold.

- Proceed with RFE: Apply standard RFE to filtered feature set.

Enhanced RFE with Pseudo-Samples for Non-linear Kernels

For non-linear SVM implementations, the RFE-pseudo-samples approach provides superior performance [14]:

- Model Optimization: Tune SVM parameters using cross-validation.

- Pseudo-Sample Generation: For each variable of interest, create a matrix with equally distanced values while maintaining other variables at their mean or median.

- Prediction: Obtain decision values from SVM for each pseudo-sample.

- Variability Measurement: Calculate Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) for each variable's predictions.

- Feature Ranking: Rank features based on MAD scores, with higher variability indicating greater importance.

- Iterative Elimination: Proceed with standard RFE elimination based on established ranks.

Advanced Applications in Biological Research

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Traditional GWAS consider SNPs independently and miss non-linear interactions [16]. RFE with non-linear SVMs enables:

- Identification of genetic features interacting in highly non-linear ways to influence disease [16]

- Discovery of features that individually show no correlation with disease but contribute to prediction in combination [16]

- Enhanced insight into genetic susceptibility to complex diseases like breast cancer [16]

Multi-Omics Data Integration

The ensemble feature selection approach integrates multiple selection strategies [19]:

- Tree-Based Ranking: Initial feature ranking using random forest or gradient boosting

- Greedy Backward Elimination: Application of RFE to progressively reduce feature sets

- Subset Merging: Combination of selected subsets from different methods to produce a final feature set

This approach has demonstrated effective dimensionality reduction (over 50% decrease in certain subsets) while maintaining or improving classification metrics across heterogeneous healthcare datasets [19].

Two-Stage Selection Framework

Recent advancements combine RFE with other selection methods [18]:

- Initial Filtering: Use random forest variable importance measures to remove low-contribution features

- Optimal Subset Search: Apply improved genetic algorithm to search for global optimal feature subset

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Minimize feature subset size while maximizing classification accuracy

This framework addresses limitations of single-method approaches and has shown significant improvements in classification performance on biological datasets [18].

Feature selection is a critical preprocessing step in machine learning, aimed at identifying the most relevant features from the original set to improve model interpretability, enhance generalization, and reduce computational cost [20]. This process is particularly vital for high-dimensional biological data, where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins) vastly exceeds the number of samples, leading to the "curse of dimensionality" and increased risk of overfitting [18] [21]. Based on their underlying mechanisms, feature selection methodologies are broadly classified into three categories: filter methods, wrapper methods, and embedded methods [22] [20] [23].

Filter methods operate independently of any machine learning model, selecting features based on intrinsic data properties and statistical measures of feature relevance [22] [23]. Wrapper methods utilize the performance of a specific predictive model as the objective function to evaluate and select feature subsets, often resulting in superior performance but at a higher computational cost [20] [24]. Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training phase, offering a compromise between the computational efficiency of filters and the performance-oriented approach of wrappers [22] [25] [23]. Understanding the distinctions, advantages, and limitations of these paradigms is essential for constructing effective analytical workflows for high-dimensional biological data.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Paradigms

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Method Categories

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Selects features based on statistical scores and intrinsic data properties, independent of a model [20] [23]. | Uses a model's performance as the objective function to evaluate feature subsets [20] [24]. | Incorporates feature selection as part of the model's own training process [22] [25]. |

| Computational Cost | Low and efficient, suitable for high-dimensional data [20] [26]. | High, due to repeated model training and validation for different feature subsets [22] [20]. | Moderate, comparable to the cost of training the model itself [22]. |

| Model Interaction | None; model-agnostic [22] [20]. | High; tightly coupled with a specific model [20]. | Integrated; specific to the learning algorithm [22] [25]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low [20]. | High, especially with small datasets [20]. | Moderate, controlled by the model's regularization [22]. |

| Primary Advantages | Fast, scalable, and computationally inexpensive [20] [26]. | Model-specific, can capture feature interactions, often high-performing [20]. | Efficient, combines selection and training, less prone to overfitting than wrappers [22] [25]. |

| Key Limitations | Ignores feature dependencies and interaction with the model [20] [18]. | Computationally intensive and less generalizable [20] [18]. | Model-dependent; the selected features are specific to the algorithm used [18]. |

| Common Examples | Chi-square test, Pearson's correlation, Fisher Score, Mutual Information [22] [26] [23]. | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Forward/Backward Selection, Genetic Algorithms [22] [20] [24]. | Lasso (L1) Regularization, Decision Tree importance, Random Forest importance [22] [24] [23]. |

The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Algorithm: A Greedy Wrapper Approach

Core Principle and Workflow

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a quintessential wrapper method that operates by recursively constructing a model, identifying the least important features, and removing them from the current subset [24]. This iterative process continues until the desired number of features is reached. RFE is considered a greedy search algorithm because it follows a pre-defined ranking path (based on feature importance) and does not re-evaluate previous decisions, which can make it susceptible to settling on a locally optimal feature subset rather than the global optimum [24]. Despite this, its effectiveness, particularly in biomedical research, has been well-documented [27] [11].

RFE Workflow Diagram

Advanced RFE Frameworks for High-Dimensional Biological Data

Synergistic Kruskal-RFE Selector (SKR)

To address challenges with medical datasets, a Synergistic Kruskal-RFE Selector (SKR) has been proposed, which combines non-parametric statistical ranking with the recursive elimination process [27]. This hybrid approach enhances the stability of feature ranking in the presence of non-normal data distributions and outliers, which are common in biological measurements. The SKR selector has demonstrated a remarkable 89% feature reduction ratio while improving classification performance, achieving an average accuracy of 85.3%, precision of 81.5%, and recall of 84.7% on medical datasets [27].

Union with RFE (U-RFE) for Multicategory Classification

The Union with RFE (U-RFE) framework represents a significant advancement for complex classification tasks, such as determining multicategory causes of death in colorectal cancer patients [11]. This meta-approach leverages multiple base estimators (e.g., Logistic Regression, SVM, Random Forest) within the RFE process. Instead of relying on a single model's feature ranking, U-RFE performs a union analysis of the subsets obtained from different algorithms, creating a final union feature set that combines the strengths of diverse models [11]. This ensemble strategy has been shown to significantly improve the performance of various classifiers, including Stacking models, which achieved an accuracy of 86.4% and an Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.717 in classifying four-category deaths [11].

Hybrid RFE and Improved Genetic Algorithm

A novel two-stage feature selection method combines Random Forest (an embedded method) with an Improved Genetic Algorithm (a wrapper method) [18]. In this architecture, RFE can be conceptually integrated into the second stage's search mechanism. The first stage uses Random Forest's Variable Importance Measure (VIM) to perform an initial, rapid filtering of low-contribution features. The second stage employs a non-greedy global search algorithm (the Improved Genetic Algorithm) to find the optimal feature subset from the candidates retained from the first stage [18]. This hybrid design mitigates RFE's greedy limitation by following the embedded pre-filtering with a more explorative wrapper search, demonstrating enhanced classification performance on UCI datasets [18].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Advanced RFE Frameworks on Biological Data

| Framework | Dataset / Application | Key Metric | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synergistic Kruskal-RFE (SKR) [27] | General Medical Datasets | Feature Reduction Ratio | 89% |

| Average Accuracy | 85.3% | ||

| Average Precision | 81.5% | ||

| Average Recall | 84.7% | ||

| Union with RFE (U-RFE) [11] | Colorectal Cancer Mortality | Accuracy | 86.4% |

| F1_weighted | 0.851 | ||

| Matthews CC | 0.717 | ||

| RF + Improved GA [18] | Eight UCI Datasets | Classification Performance | Significant Improvement |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing RFE for Gene Expression Data

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for RFE Implementation

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Python/R | Primary programming languages for implementing custom RFE workflows. | Python's scikit-learn offers built-in RFE support. |

| scikit-learn | Machine learning library providing the RFECV class for recursive feature elimination with cross-validation. |

Essential for model training, ranking, and iterative elimination. |

| Base Estimator | The core machine learning model used by RFE to rank features. | SVM, Random Forest, or Logistic Regression are common choices [11]. |

| Feature Importance Metric | The criterion used to rank features for elimination at each iteration. | Model-specific: coefficients for SVM/LR, Gini for RF. |

| Cross-Validation Scheme | Method for evaluating model performance on different data splits to guide the feature selection and prevent overfitting. | 5-fold or 10-fold stratified cross-validation is typical. |

| Performance Metrics | Measures to assess the quality of the selected feature subset. | Accuracy, F1-score, AUC-ROC for classification. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Partitioning

- Load the high-dimensional gene expression dataset (e.g., from TCGA or other public repositories) [11].

- Perform standard preprocessing: log-transformation, normalization, and handling of missing values.

- Partition the data into training and hold-out test sets (e.g., 70/30 or 80/20 split). The test set must be set aside and not used in any part of the feature selection process to ensure an unbiased evaluation.

Step 2: Base Estimator and RFE Framework Configuration

- Select one or more base estimators. For a U-RFE framework, use multiple diverse models such as Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF) [11].

- Initialize the RFE object for each base estimator. Specify the

n_features_to_selectparameter, which can be a fixed number or determined via cross-validation (RFECV). - For a hybrid embedded-wrapper approach, first compute feature importance scores using an embedded method like Random Forest. Use these scores to pre-filter features, reducing the input dimensionality for the subsequent RFE stage [18].

Step 3: Model Training and Recursive Elimination

- Fit the RFE object(s) on the training data. The internal workflow, as depicted in the diagram, will execute iteratively:

- Train Model: The base estimator is trained on the current feature subset.

- Rank Features: Features are ranked based on the model's importance metric.

- Eliminate Feature(s): The least important feature(s) are pruned.

- Check Stopping Criterion: The loop continues until the target number of features is reached.

- Use k-fold cross-validation at each step (or use

RFECV) to evaluate the performance of the current feature subset and ensure robustness.

Step 4: Feature Subset Selection and Final Model Evaluation

- Once the recursion completes, obtain the final optimal feature subset from the RFE object.

- If using a U-RFE approach, take the union of the top-ranked features from the different base estimators to form the final feature set [11].

- Train a final predictive model (e.g., a Stacking classifier [11]) using only the selected features on the entire training set.

- Evaluate the final model's performance on the held-out test set using pre-defined metrics (e.g., Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score).

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) firmly resides in the wrapper method category of feature selection algorithms, distinguished by its use of a machine learning model's performance to guide the greedy, iterative search for an optimal feature subset [24]. While powerful, its standalone application can be limited by computational demands and the risk of converging on local optima [18] [24].

The most effective modern applications of RFE for high-dimensional biological data involve its use within hybrid or multi-stage frameworks [18] [27] [11]. By pairing RFE with fast filter or embedded methods for initial dimensionality reduction, or by leveraging an ensemble of models (as in U-RFE), researchers can mitigate its limitations and enhance the robustness of the selected features. RFE remains a cornerstone technique in the data scientist's toolkit, and its continued evolution through strategic hybridization ensures its relevance in tackling the complexities of omics data and advancing biomedical research.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has emerged as a powerful feature selection algorithm in biomedical research, particularly for analyzing high-dimensional biological data. In contexts where the number of variables (p) far exceeds the number of samples (n)—a common scenario in omics research—RFE provides a systematic approach to identify the most informative features. RFE operates as a wrapper-style feature selection algorithm that works by recursively removing the least important features and rebuilding the model until the desired number of features remains [2]. This method is especially valuable in biomarker discovery, where it helps overcome the "curse of dimensionality" by eliminating redundant and irrelevant features, thus improving model performance and interpretability [9].

The fundamental strength of RFE lies in its model-agnostic nature and its recursive elimination strategy. By iteratively training a model, ranking features by importance, and pruning the least significant ones, RFE efficiently navigates the complex feature space characteristic of biomedical data [28]. This process is particularly crucial in drug discovery and development pipelines, where machine learning approaches like RFE can enhance decision-making, speed up processes, and reduce failure rates by identifying plausible therapeutic hypotheses from high-dimensional data [29].

Core Principles of Recursive Feature Elimination

The RFE Algorithmic Framework

The RFE algorithm follows a structured, iterative process to identify optimal feature subsets. The core procedure involves these key stages [28] [2]:

- Initial Model Training: A machine learning model is trained using all available features in the dataset.

- Feature Importance Ranking: Features are ranked based on importance metrics derived from the trained model (e.g., coefficients, feature importances).

- Feature Elimination: The least important feature(s) are removed from the current feature set.

- Iterative Refinement: Steps 1-3 are repeated on the reduced feature set until a predefined number of features remains.

This recursive process generates a feature ranking, with the final selected features assigned a rank of 1 [3]. The algorithm can be customized through several parameters, including the choice of estimator, number of features to select, and step size (number/percentage of features to remove per iteration) [3].

RFE Variants and Enhancements

Several enhanced RFE implementations have been developed to address specific challenges in biomedical data analysis:

- WERFE (Wrapper Ensemble RFE): Employs an ensemble strategy that integrates multiple gene selection methods and assembles top-selected genes from each approach as the final subset. This method prioritizes more important genes selected by each constituent method, resulting in more discriminative and compact gene subsets [30].

- MCC-REFS (Matthews Correlation Coefficient-based REFS): Uses MCC as a selection criterion instead of traditional accuracy metrics, providing better performance for imbalanced datasets. This method automatically selects informative feature sets without requiring predefined feature counts [31].

- RFECV (RFE with Cross-Validation): Incorporates cross-validation to automatically determine the optimal number of features, reducing the risk of overfitting during the feature selection process [3].

The following diagram illustrates the core RFE workflow and its ensemble variant:

Key Applications in Biomedical Research

Gene Selection and Biomarker Discovery

RFE has demonstrated significant utility in gene selection from microarray and RNA-seq data, where it helps identify compact yet discriminative gene signatures. In one application to breast cancer classification, the WERFE method successfully selected minimal gene sets while maintaining high classification performance [30]. Similarly, RFE-based approaches have been applied to transcriptomic data from mouse heart ventricles to identify genes associated with response to isoproterenol challenge, revealing potential biomarkers for heart failure [9].

For triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtyping, RFE workflows have enabled identification of protein signatures that accurately classify mesenchymal-, luminal-, and basal-like subtypes from proteomic quantification data [9]. These applications demonstrate RFE's capability to handle the "large p, small n" paradigm common in omics studies, where the number of features (genes/proteins) vastly exceeds sample sizes [32].

Clinical Outcome Prediction and Prognostic Modeling

RFE has been widely employed in developing prognostic models across various disease domains. In cardiovascular research, the Regicor dataset application used RFE to identify 22 genes predictive of cardiovascular mortality risk [30]. Similar approaches have been applied to prostate cancer data, selecting 100-gene panels for cancer classification based on gene expression profiles [30].

The methodology for clinical outcome-relevant gene identification typically involves a two-step process: initial identification of genes strongly associated with clinical outcomes, followed by refinement through statistical simulations to optimize classification accuracy [33]. This approach ensures selected gene sets are not only statistically significant but also clinically relevant and less variable when applied to new datasets.

Drug Discovery and Development Applications

In pharmaceutical research, RFE supports multiple stages of drug discovery and development. Key applications include:

- Target Validation: RFE helps identify and prioritize plausible therapeutic targets by selecting genomic features most strongly associated with disease phenotypes [29] [34].

- Toxicogenomics: Applications like the RatinvitroH dataset analysis used RFE to identify hepatotoxicity-related genes from toxicogenomics data, supporting drug safety assessment [30].

- Biomarker Development for Clinical Trials: RFE assists in identifying prognostic and predictive biomarkers that can stratify patients or predict drug efficacy in clinical trials [29].

- Drug Repurposing: By analyzing gene expression patterns, RFE can identify new therapeutic indications for existing compounds [34].

Table 1: Summary of RFE Applications in Biomedical Domains

| Application Domain | Data Type | Typical Feature Size | Representative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Subtype Classification | Gene Expression Microarray | 70-100 genes | Accurate discrimination of breast cancer subtypes [30] |

| Toxicogenomics | Transcriptomics | 31,042 genes | Identification of hepatotoxicity biomarkers [30] |

| Cardiovascular Risk Prediction | Gene Expression | 22 genes | Mortality risk stratification [30] |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides | Peptide Sequences | 188 features | Classification of peptide properties [30] |

| Proteomics Classification | Protein Quantification | 7,391 peptides | TNBC subtype classification [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard RFE Protocol for Gene Expression Data

This protocol describes the application of RFE for gene selection from high-dimensional gene expression data, adapted from established workflows [30] [9].

Materials and Reagents

- High-quality gene expression data (microarray or RNA-seq)

- Normalized and batch-corrected expression matrix

- Associated clinical or phenotypic metadata

- Computational environment with necessary software libraries

Procedure

Data Preprocessing

- Perform quality control on raw expression data

- Apply normalization appropriate for platform (e.g., RMA for microarray, TPM for RNA-seq)

- Address batch effects using ComBat or similar methods

- Annotate genes with current genomic coordinates

Initial Feature Filtering

- Remove low-expression genes (less than 1 count per million in >90% samples)

- Apply variance filter to eliminate non-informative genes

- Retain top 10,000-15,000 most variable genes for downstream analysis

RFE Implementation

- Partition data into training (70-80%) and validation (20-30%) sets

- Select appropriate estimator (SVM or Random Forest recommended)

- Configure RFE parameters: nfeaturesto_select=50, step=5% of features

- Train RFE model on training data with 10-fold cross-validation

- Record feature rankings and selection metrics

Model Validation

- Apply selected features to independent validation set

- Assess classification performance (accuracy, AUC, MCC)

- Compare with alternative feature selection methods

- Perform permutation testing to evaluate significance

Biological Interpretation

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis on selected genes

- Validate findings in external datasets when available

- Relate gene signatures to known biological processes

Troubleshooting

- Poor classification performance may indicate insufficient sample size or weak biological signal

- High variance in feature selection suggests dataset instability; consider ensemble approaches

- If computational time is excessive, increase step size or apply preliminary filtering

Ensemble RFE Protocol for Robust Biomarker Discovery

The WERFE protocol integrates multiple feature selection methods to improve robustness, particularly for low-sample size datasets [30] [31].

Procedure

Multiple Method Implementation

- Execute three to five diverse feature selection methods in parallel

- Include both filter-based (e.g., relief, chi-square) and wrapper methods

- Ensure methods have different theoretical foundations

Feature Ranking Integration

- Extract top-ranked features from each method (e.g., top 50)

- Apply union operation to combine feature sets

- Remove duplicates to create candidate feature pool

Consensus Feature Selection

- Apply RFE to the candidate feature pool

- Use ensemble classifier (e.g., Random Forest) as estimator

- Employ MCC-based criterion for improved imbalance handling [31]

Stability Assessment

- Perform bootstrap resampling (100+ iterations)

- Calculate feature selection frequency across iterations

- Retain features with selection frequency >80%

Final Model Construction

- Train final predictive model using stable features

- Optimize hyperparameters via grid search

- Evaluate on completely independent test set

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RFE Implementation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | Python, R | Primary computational environments for implementation |

| ML Frameworks | scikit-learn, Caret | Provide RFE implementation and supporting utilities |

| Specialized Packages | FSelector, Kernlab | Offer additional feature selection algorithms and kernels |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2, Matplotlib | Generate publication-quality figures and charts |

| Bioconductor Tools | limma, DESeq2 | Handle specialized omics data preprocessing and analysis |

| High-Performance Computing | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Enable acceleration through GPUs for deep learning variants |

Implementation Considerations for Biomedical Data

Handling High-Dimensional Low-Sample Size Data

The analysis of high-dimensional biomedical data presents unique challenges that require specialized approaches [32]:

- Sample Size Considerations: Traditional rules of thumb (e.g., 10 events per variable) break down in HDD settings. While adequate sample size remains crucial, HDD studies often proceed with limited samples, emphasizing the need for robust validation [32].

- Biological vs. Technical Replicates: Distinguish between biological replicates (different subjects) and technical replicates (repeated measurements on same subject). Only biological replicates contribute to sample size for inference about populations [32].

- Multi-level Validation: Implement validation at multiple levels including statistical (cross-validation), biological (pathway coherence), and clinical (association with outcomes).

Addressing Class Imbalance

Class imbalance is common in biomedical datasets, particularly in case-control studies with rare diseases. The MCC-REFS approach specifically addresses this challenge by using Matthews Correlation Coefficient instead of accuracy for feature evaluation [31]. Additional strategies include:

- Synthetic minority oversampling (SMOTE) during training

- Stratified sampling in cross-validation

- Algorithm-specific class weighting

- Balanced bootstrap sampling

Computational Optimization

RFE can be computationally intensive for very high-dimensional data. Optimization strategies include:

- Parallel processing for independent iterations

- Incremental feature elimination with larger step sizes

- Preliminary filtering to reduce feature space

- Cloud computing and high-performance computing resources

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

As biomedical data continue to grow in complexity and volume, RFE methodologies are evolving to address new challenges. Promising directions include:

- Integration with Deep Learning: Combining RFE with deep neural architectures for enhanced feature selection from complex data patterns [29].

- Multi-Omics Applications: Extending RFE to integrated analyses of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data.

- Longitudinal Data Analysis: Adapting RFE for time-series omics data to identify dynamic biomarkers.

- Automated Machine Learning: Incorporating RFE into automated ML pipelines for streamlined biomarker discovery.

- Clinical Implementation: Developing standardized protocols for translating RFE-derived signatures into clinical diagnostics.

The continued refinement of RFE approaches, particularly ensemble and deep learning-integrated methods, promises to enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from high-dimensional biomedical data, ultimately supporting advances in personalized medicine and therapeutic development.

Implementing RFE: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Data to Deployment

This document provides a standardized protocol for employing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) in high-dimensional biological data analysis, with a specific focus on evaluating the performance of Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) as core feature ranking engines. The "curse of dimensionality" is a significant challenge in bioinformatics, where datasets often contain thousands to millions of features (e.g., genes, proteins) but only a limited number of samples [9]. Effective feature selection is a non-trivial task that is crucial for improving model performance, reducing overfitting, enhancing computational efficiency, and identifying biologically relevant biomarkers [13] [9]. This protocol outlines a rigorous, comparative framework to help researchers and drug development professionals select the most appropriate model for their specific feature ranking objectives, thereby streamlining the analysis pipeline and bolstering the reliability of research outcomes in genomics, transcriptomics, and related fields.

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

A review of recent applications in biological data analysis reveals the comparative performance of SVM, RF, and XGBoost when integrated with RFE. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from peer-reviewed studies.

Table 1: Comparative Model Performance in Biological Classification Tasks with Feature Selection

| Application Domain | Best Model | Key Performance Metrics | Feature Selection Method | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer Subtype Classification | Random Forest | Overall F1-score: 0.93 | RFE | [35] |

| Colorectal Cancer Subtype Classification | XGBoost | Overall F1-score: 0.92 | RFE | [35] |

| Prediction of Calculous Pyonephrosis | XGBoost | AUC: 0.981, Sensitivity: 0.962, Specificity: 1.000 | RFE (for SVM), Lasso (for LR) | [36] |

| Prediction of Calculous Pyonephrosis | SVM | AUC: 0.977 (Testing set) | RFE | [36] |

| Thyroid Nodule Malignancy Diagnosis | XGBoost | AUC: 0.928, Accuracy: 0.851 | RF & Lasso for pre-filtering | [37] |

| Cancer Detection (Breast/Lung) | Stacked Model (LR, NB, DT) | Accuracy: 100% (with selected features) | Hybrid Filter-Wrapper | [38] |

Key Insights:

- Random Forest and XGBoost consistently demonstrate high performance in classification tasks, with RF showing a marginal advantage in the specific context of colorectal cancer exome data [35].

- SVM paired with RFE remains a powerful and highly competitive model, particularly in clinical diagnostic settings, as evidenced by its superior performance in testing for pyonephrosis prediction [36].

- The integration of feature selection, particularly RFE, is a common factor among top-performing models across diverse applications, underscoring its critical role in model optimization [35] [36] [37].

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for High-Dimensional Biological Data

This protocol describes the standard RFE procedure adaptable for use with SVM, RF, or XGBoost.

3.1.1 Workflow Overview

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preprocessing:

- Perform standard preprocessing on your high-dimensional dataset (e.g., gene expression, SNP data). This includes handling missing values via imputation [36], normalizing or standardizing features, and addressing class imbalance with techniques like SMOTE if necessary [39] [40].

- Split the dataset into training, validation, and testing sets (e.g., 70/30 ratio) to ensure unbiased performance evaluation [36].

Model Initialization and Configuration:

- Initialize your chosen core model with sensible default or optimized hyperparameters.

- SVM: Use a linear kernel (

kernel='linear') to ensure the generation of feature weights (coef_) suitable for ranking [1] [36]. - Random Forest/XGBoost: These models provide native feature importance scores (e.g., Gini importance or gain) and do not require a specific kernel [35] [37].

Iterative Feature Ranking and Elimination:

- Train the model on the current set of features.

- Rank all features using the model's intrinsic ranking method:

- Eliminate the least important feature(s). The

stepparameter in Scikit-learn'sRFEcontrols how many features are removed per iteration [1]. - Repeat the training, ranking, and elimination cycle until the predefined number of features is reached.

Determination of Optimal Feature Subset:

- The optimal number of features can be determined through cross-validation (e.g., using

RFECV). The point at which model performance (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) peaks or stabilizes on the validation set indicates the optimal feature subset size [1].

- The optimal number of features can be determined through cross-validation (e.g., using

Model-Specific Implementation Notes

For SVM-RFE:

- The linear kernel is mandatory for feature ranking based on coefficient magnitude. Non-linear kernels like RBF are not suitable for this purpose [1].

- Standardization of features is critical for SVM-RFE, as the model is sensitive to the scale of the data.

For Random Forest/XGBoost-RFE:

- These ensemble methods are robust to non-linearly correlated features and can handle a mix of data types [35].

- They provide a native feature importance metric, making the ranking process straightforward. However, be aware that correlated features can affect the importance distribution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools for RFE Implementation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in Protocol | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn (Python) | Software Library | Provides implementations of SVM, RF, XGBoost, and the RFE/RFECV classes. |

from sklearn.feature_selection import RFE [1] |

| XGBoost (Python/R) | Software Library | An optimized implementation of Gradient Boosting for fast and performant model training. | Used in multiple high-performing studies [35] [36] [37] |

R (with caret, randomForest packages) |

Software Environment | An alternative environment for statistical computing and machine learning. | The caret package streamlines model training and feature selection [9] |

| Linear Kernel | Model Parameter | Enables SVM to generate feature coefficients for ranking. | SVR(kernel="linear") [1] |

| SMOTE | Data Preprocessing Method | Synthetically balances imbalanced datasets to prevent biased feature selection. | Used in breast cancer analysis to optimize feature selection [39] |

| Lasso Regression | Feature Selection Method | An embedded method that can be used prior to or in conjunction with RFE for preliminary feature filtering. | Used to select influential factors for thyroid nodule diagnosis [37] |

Workflow Visualization: From Data to Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a bioinformatics project utilizing RFE, from raw data to biological insight, as demonstrated in the reviewed literature.

This end-to-end workflow has been successfully deployed in recent studies. For instance, research in colorectal cancer utilized exome data to train RF and XGBoost models via RFE, achieving high F1-scores, and subsequently deployed the best-performing models into a web application using Shiny Python to assist clinicians and researchers [35]. This underscores the practical translational potential of a well-defined RFE protocol.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper-style feature selection algorithm that iteratively constructs a model, identifies the least important features, and removes them until a specified number of features remains [2]. In high-dimensional biological research, such as gene expression analysis and biomarker discovery, RFE provides a critical methodology for identifying the most relevant features from datasets where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins) far exceeds the number of samples [21] [9]. The performance of RFE is fundamentally dependent on the quality and structure of the input data, making proper preprocessing an essential prerequisite for obtaining biologically meaningful and robust feature subsets.

Data preprocessing transforms raw, often messy data into a structured format suitable for machine learning algorithms [41] [42]. Within the context of RFE for high-dimensional biological data, three preprocessing challenges are particularly critical: handling missing values, which are common in experimental data; normalization, to address the varying scales of biological measurements; and class imbalance, which can bias feature selection toward overrepresented classes. This protocol outlines detailed methodologies for addressing these challenges to ensure RFE identifies a robust, minimal feature set with maximal predictive power for downstream analysis and drug development.

Technical Specifications and Impact on RFE

The following table summarizes the core preprocessing challenges for RFE and their specific impacts on the feature selection process in biological data contexts.

Table 1: Preprocessing Challenges and Their Impact on RFE Performance

| Preprocessing Challenge | Direct Impact on RFE Process | Consequence for Feature Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Values | Compromises the model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) used internally by RFE to rank features, as most models cannot handle missing data directly [43]. | Introduces bias in feature importance scores, potentially leading to the erroneous elimination of biologically significant features. |

| Improper Normalization | Skews the feature importance calculations in models sensitive to feature scale (e.g., SVM, Logistic Regression), which are commonly used with RFE [2] [44]. | Features with larger scales are artificially weighted as more "important," resulting in a suboptimal and biased final feature subset. |

| Class Imbalance | Causes the internal RFE model to be biased toward the majority class, as accuracy is maximized by predicting the most frequent class [45]. | RFE selects features that are optimal for predicting the majority class but may miss critical biomarkers for the rare, often more clinically relevant, class (e.g., a rare cancer subtype). |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Handling Missing Values in Biological Data

Missing data is a pervasive issue in bioinformatics, arising from technical variations in sample processing, instrument detection limits, or data corruption [43]. The mechanism of missingness—Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Not Missing at Random (NMAR)—should guide the imputation strategy, with NMAR being the most challenging as the missingness is related to the unobserved value itself [43].

Protocol 1: Model-Based Multiple Imputation using mice in R

Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) is a state-of-the-art technique that accounts for the uncertainty in imputation by creating multiple complete datasets [43].

Load Required Packages and Data:

Diagnose Missingness Pattern:

Perform Multiple Imputation: Use Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) for numeric data, as it preserves the data distribution.

Validate Imputation Quality:

Proceed with RFE: RFE can be run on each of the

mimputed datasets, and the final selected features can be pooled, or a single high-quality imputed dataset can be used.

Protocol 2: Random Forest Imputation using missForest in R

For complex, non-linear biological data, missForest is a robust, non-parametric imputation method [43].

Install and Load Package:

Run Imputation:

Retrieve Completed Data and Assess Error:

Data Normalization and Standardization

Normalization ensures that all features contribute equally to the model's distance-based calculations within RFE, rather than being dominated by a few high-magnitude features [41] [44]. Z-score standardization is highly recommended for RFE.

Protocol 3: Z-Score Standardization

This technique centers the data around a mean of zero and scales it to a standard deviation of one [46].

Manual Calculation in R/Python:

R:

Python (using scikit-learn):

Integration with RFE Pipeline: To prevent data leakage, the scaling parameters (mean, standard deviation) must be learned from the training set and applied to the test set.

Python scikit-learn example:

Addressing Class Imbalance

In datasets like cancer vs. control studies, class imbalance can severely bias RFE. Resampling techniques adjust the class distribution to create a balanced dataset [45].

Protocol 4: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE)

SMOTE generates synthetic examples for the minority class rather than simply duplicating them [45].

Load Required Libraries in R:

Apply SMOTE: Specify the outcome variable (

Class) and the desired perc.over/perc.under parameters to control synthesis.

Protocol 5: Combining SMOTE with RFE

For optimal results, resampling should be performed within each cross-validation fold during the RFE process to avoid over-optimism.

- Use Custom Resampling with

caretin R: Thecaretpackage allows for defining custom resampling schemes that integrate SMOTE with RFE and cross-validation, ensuring that the synthetic data is created only from the training fold in each iteration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Packages for Preprocessing and RFE

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Primary Use in Preprocessing for RFE |

|---|---|---|

mice (R) [43] |

Statistical Package / Multiple Imputation | Gold-standard for handling MAR data by creating multiple imputed datasets. |

missForest (R) [43] |

ML Package / Non-parametric Imputation | Handles complex, non-linear relationships in data for accurate imputation. |

scikit-learn (Python) [2] [42] |

ML Library / Preprocessing & Pipelines | Provides StandardScaler, SimpleImputer, and Pipeline for building leakage-proof preprocessing and RFE workflows. |

DMwR2 / smote (R) [45] |

Data Mining Package / Resampling | Implements SMOTE to address class imbalance before feature selection. |

caret (R) [9] |

ML Framework / Unified Workflow | Provides a unified interface for RFE, model training, and cross-validation with integrated preprocessing. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated preprocessing and RFE workflow for high-dimensional biological data.

Integrated Preprocessing and RFE Workflow for Robust Feature Selection.

Effective data preprocessing is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational component of a successful RFE protocol for high-dimensional biological data. As demonstrated, the handling of missing values, data normalization, and class imbalance directly and profoundly influences the features selected by the RFE algorithm. By adhering to the detailed application notes and protocols outlined herein—utilizing robust, model-based imputation, consistent scaling, and strategic resampling—researchers and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the reliability, interpretability, and biological relevance of their feature selection outcomes. This rigorous approach ensures that subsequent models and conclusions are built upon a solid and reproducible data foundation.

In the age of 'Big Data' in biomedical research, high-throughput omics technologies (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) generate datasets with a massive number of features (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) but often with relatively few samples [9]. This high-dimensional environment presents significant challenges for analysis, including long computation times, decreased model performance, and increased risk of overfitting [9]. Feature selection becomes a crucial and non-trivial task in this context, as it provides deeper insight into underlying biological processes, improves computational performance, and produces more robust models [9].

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has emerged as a powerful wrapper feature selection method that is particularly well-suited to high-dimensional biological data. RFE is a feature selection algorithm that iteratively removes the least important features from a dataset until a specified number of features remains [3]. Introduced as part of the scikit-learn library, RFE leverages a machine learning model's feature importance rankings to systematically prune features [3] [47]. The core strength of RFE lies in its ability to consider interactions between features, making it suitable for complex biological datasets where genes, proteins, or metabolites often function in interconnected pathways rather than in isolation [1].

The application of RFE in bioinformatics has grown substantially, with demonstrated success in areas such as cancer classification using gene expression data [9] [48], biomarker discovery in microbiome studies [48], and analysis of high-dimensional metabolomics data [49]. Its recursive nature allows researchers to distill thousands of potential features down to a manageable subset of the most biologically relevant candidates for further experimental validation.

Theoretical Foundations of the RFE Algorithm

Core Mechanics and Workflow

The Recursive Feature Elimination algorithm operates through a systematic, iterative process that combines feature ranking with backward elimination. The algorithm works in the following steps [3] [1]:

- Rank Features: Train the chosen machine learning model on the entire set of features and rank all features by their importance.

- Eliminate Least Important Feature: Remove the feature(s) with the lowest importance score.

- Rebuild Model: Construct a new model with the remaining features.

- Repeat: Iterate steps 1-3 until the desired number of features is reached.

This greedy algorithm starts its search from the entire feature set and selects subsets through a feature ranking method [12]. By repeatedly constructing machine learning models to rank feature importance, it eliminates one or more features with the lowest weights at each iteration [12]. The process generates a final feature subset ranking based on evaluation criteria, typically the predictive accuracy of classifiers [12].

Comparison with Other Feature Selection Methods

Understanding how RFE compares to other feature selection approaches helps researchers select the appropriate method for their specific biological question.

Table 1: Comparison of RFE with Other Feature Selection Methods

| Method Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitability for Biological Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Uses statistical measures (correlation, mutual information) to evaluate features individually [1]. | Fast execution; simple implementation [1]. | Ignores feature interactions; less effective with high-dimensional data [1]. | Limited for complex omics data with interdependent features. |

| Wrapper Methods (RFE) | Uses a learning algorithm to evaluate feature subsets; considers feature interactions [1]. | Captures feature dependencies; suitable for complex datasets [1]. | Computationally intensive; prone to overfitting [1]. | Excellent for omics data where biological pathways involve feature interactions. |

| Embedded Methods | Feature selection built into model training (e.g., Lasso, Random Forest) [9]. | Balances performance and computation; considers feature interactions [9]. | Model-specific; may not find globally optimal subset [9]. | Good for many omics applications; efficient for high-dimensional data. |

| Dimensionality Reduction (PCA) | Transforms features into lower-dimensional space [9]. | Effective dimensionality reduction; removes redundancy [9]. | Loss of interpretability; not suitable for non-linear relationships [1]. | Poor when biological interpretation of original features is required. |

RFE Protocols for Biological Data Analysis

Standard RFE Implementation Protocol

The following protocol describes a standard implementation of RFE for high-dimensional biological data using Python and scikit-learn, suitable for datasets such as gene expression, proteomics, or metabolomics.

Materials and Reagents

- Computing Environment: Python 3.7+ with Jupyter Notebook or similar IDE.

- Required Python Libraries: scikit-learn 1.0+, pandas 1.3+, NumPy 1.20+, matplotlib 3.4+ or seaborn 0.11+.