ABFE vs RBFE: A Strategic Guide to Binding Free Energy Methods in Drug Discovery

Accurate calculation of protein-ligand binding affinity is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery.

ABFE vs RBFE: A Strategic Guide to Binding Free Energy Methods in Drug Discovery

Abstract

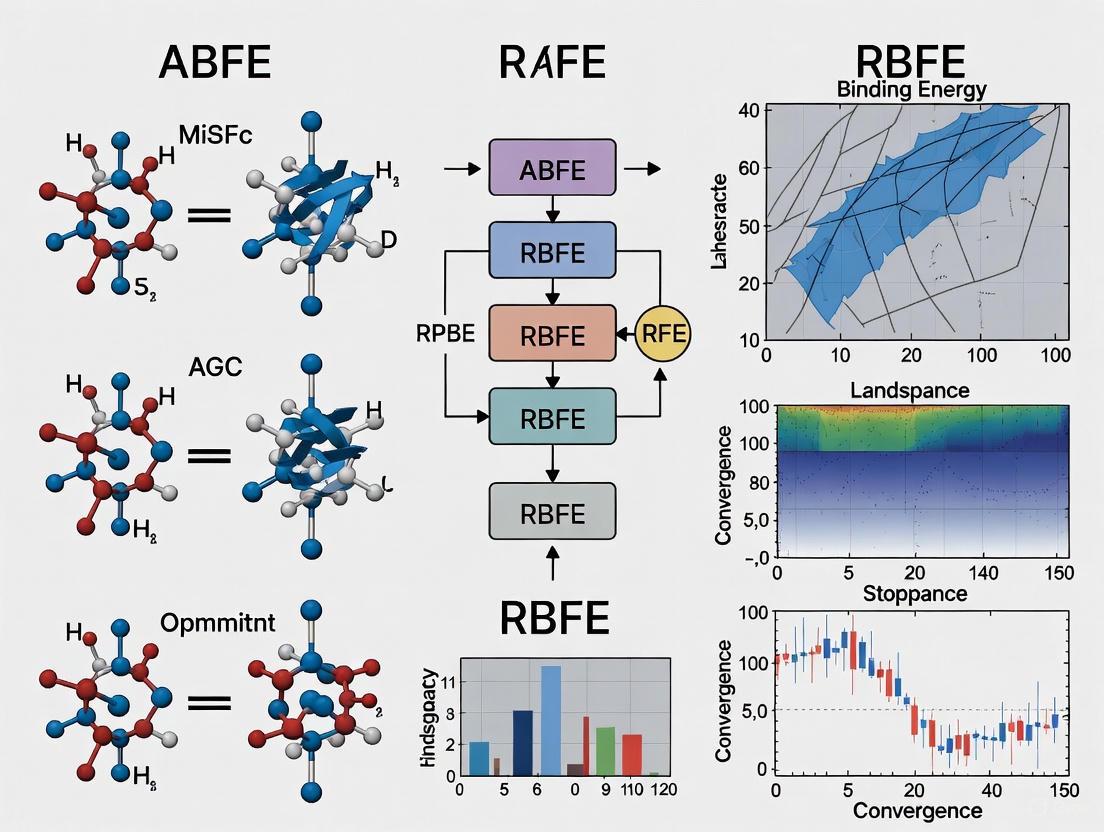

Accurate calculation of protein-ligand binding affinity is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two predominant physics-based methods: Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations. We explore their foundational principles, distinct application domains—from virtual screening of diverse compounds (ABFE) to lead optimization in congeneric series (RBFE)—and address key technical challenges such as sampling, force field accuracy, and handling charged molecules. By examining validation benchmarks, prospective applications, and emerging trends like automated workflows and active learning, this guide equips researchers and drug developers with the knowledge to strategically select and implement these powerful tools to accelerate their pipelines.

Understanding the Core Principles: What Are ABFE and RBFE?

The accurate prediction of the standard binding free energy (ΔG°) is a fundamental challenge in computational biophysics and computer-aided drug design. Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations provide a first-principles approach to estimating this crucial parameter, which defines the binding affinity between a biomolecule and a ligand under standard state conditions (1 M concentration) [1]. Unlike Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) methods that compute affinity differences between similar compounds, ABFE can be applied to structurally diverse molecules, making it particularly valuable for virtual screening and hit identification in early drug discovery stages [2] [3]. The accuracy of ABFE calculations has improved significantly in recent years due to advances in force fields, sampling algorithms, and computational hardware, particularly GPUs [4]. This guide examines the theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, and practical applications of ABFE calculations, providing a comparative analysis with RBFE approaches for binding affinity research.

Theoretical Foundations: Defining the Standard State

What is Standard Binding Free Energy?

The standard binding free energy (ΔG°b) represents the free energy change when a ligand and receptor bind to form a complex in an ideal solution at standard concentration (C° = 1 M) [1]. This standard state definition is essential because binding free energy depends on the concentrations of receptor and ligand; reporting a "standard" value specifies it corresponds to 1 M concentrations, enabling meaningful comparisons across different systems and experimental conditions.

The relationship between the standard binding free energy and experimentally measurable quantities is given by:

ΔG°b = -RT ln Kb

where Kb is the equilibrium binding constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature [1]. In practice, the dissociation constant Kd (Kd = 1/Kb) is often measured experimentally and reported with concentration units (e.g., nM, μM), though the equilibrium constant itself is technically dimensionless [1].

The Critical Role of Restraints and Binding Site Volume

A fundamental challenge in ABFE calculations involves properly defining the bound state. The binding site volume (Vsite) must be explicitly defined through restraints to avoid the "wandering ligand" problem and ensure thermodynamic convergence [1]. When a ligand is partially decoupled from its environment during alchemical transformations, it may drift away from the binding site without proper restraints, leading to ill-defined states and convergence issues [5] [1].

The complete standard binding free energy includes both excess and ideal components:

ΔG°b = ΔG°excess + ΔG°ideal

where ΔG°ideal = -kBT ln(C°Vsite) accounts for the standard state correction [1]. For restraints involving orientation, an additional angular term -kBT ln(Ωsite/8π²) must be included [1]. These restraining potentials must remain active throughout the alchemical transformation to maintain a consistent definition of the complexed state [1].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Standard State Binding Free Energy

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Standard State | C° = 1 M | Reference concentration for reporting binding free energies |

| Binding Constant | Kb = [RL]/[R][L] (dimensionless) | Equilibrium constant for binding reaction |

| Standard Binding Free Energy | ΔG°b = -RT ln Kb | Free energy change at standard state |

| Ideal Term | ΔG°ideal = -kBT ln(C°Vsite) | Entropic cost of confining ligand to binding site volume |

Methodological Approaches to ABFE Calculation

Alchemical Transformation Methods

The alchemical pathway approach uses non-physical pathways to compute binding free energies through a double-decoupling process [5] [4]. In this method, the ligand is reversibly decoupled from its environment in two separate simulations: first in the binding site, then in bulk solution [5]. The binding free energy is calculated as the difference between these two transformation energies [6]. This decoupling process typically employs a coupling parameter (λ) that gradually scales the ligand's interactions with its environment from fully interacting (λ=0) to completely non-interacting (λ=1) [5]. To manage sampling challenges, sophisticated restraint schemes are applied to maintain the ligand in the binding site during decoupling [5] [1].

Physical Pathway Methods

Physical pathway approaches compute the binding free energy along a coordinate representing the physical association process [4]. These methods typically employ a potential of mean force (PMF) calculation where the ligand is physically pulled away from the binding site along a chosen reaction coordinate [5] [4]. While this approach more directly represents the actual binding process, it requires careful selection of the reaction coordinate and may suffer from sampling limitations in complex systems with high-dimensional energy landscapes [5]. To address these challenges, advanced sampling techniques like Adaptive Biasing Forces (ABF) and Replica Exchange Umbrella Sampling (REMD-US) are often employed to enhance convergence [5]. Both alchemical and physical pathway methods can achieve comparable accuracy when properly implemented, as demonstrated in studies of peptide binding to SH3 domains where both approaches reproduced experimental binding free energies within 0.2-0.3 kcal/mol [5].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing ABFE Calculations

Structure Preparation and System Setup

Successful ABFE calculations require meticulous preparation of protein-ligand systems. For protein targets, high-quality structures from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling are essential [2]. The protein preparation process involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states of ionizable residues appropriate for the experimental pH, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks [2]. For example, in a study of BACE1 inhibitors, the protein was protonated for pH 4.5 to match experimental conditions, while accounting for possible upward pKa shifts of ligand groups due to charged aspartates in the catalytic site [2].

Ligand preparation requires special attention to protonation states, tautomers, and stereochemistry [2]. Using tools like LigPrep, researchers generate candidate alternate protonation and tautomer states along with Epik penalty terms that estimate the relative stability of each form [2]. For compounds with undefined stereocenters, all stereoisomers should be considered, with the assumption that the affinity of the best-binding stereoisomer approximates the binding affinity of the mixture [2].

Binding Pose Generation and Equilibration

Accurate initial ligand poses are critical for ABFE calculations [2]. When experimental complex structures are unavailable, docking calculations can generate initial poses, though the limitations of docking algorithms necessitate careful validation [2]. Recent advances in protein-ligand structure prediction, such as Boltz-2, offer promising alternatives to docking for generating initial structures [7]. Following pose generation, molecular dynamics (MD) equilibration is essential to relax the complex and identify stable binding modes. In virtual screening applications, multiple docked poses (e.g., 10 poses per compound) are typically equilibrated by MD, with poses that move away from the binding site discarded before proceeding to full ABFE calculations [2].

Free Energy Calculation Workflow

The core ABFE calculation involves a carefully staged process using molecular dynamics simulations. A typical protocol includes:

- Restraint application to define the binding site volume and maintain ligand orientation [1]

- Alchemical transformation using stratified λ windows with sufficient overlap [5]

- Enhanced sampling through replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) to improve convergence [6]

- Error assessment through multiple independent calculations with different random seeds [2]

For example, in a study of kinase inhibitors, FEP/REMD calculations used 32 replicas for each transformation, with simulations totaling 2 ns per λ value, requiring 10-15k core hours per calculation on supercomputing infrastructure [6].

Table 2: Representative ABFE Protocol for Virtual Screening

| Step | Key Parameters | Validation Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| System Preparation | Protonation at experimental pH, Epik penalty terms | Comparison with known crystal structures |

| Pose Generation | Glide SP docking, 10 poses per compound | Pose stability during MD equilibration |

| Equilibration | MD simulation (ns timescale) | Root mean square deviation (RMSD) stability |

| ABFE Calculation | 20-32 λ windows, REMD sampling | Convergence of free energy estimate, hysteresis |

| Error Analysis | Independent repeats with different random seeds | Standard deviation across replicates |

ABFE vs. RBFE: A Comparative Analysis

Methodological Differences and Applications

ABFE and RBFE represent complementary approaches with distinct strengths and limitations. While ABFE calculates the binding free energy of a single ligand directly, RBFE computes the binding free energy difference between two similar ligands through alchemical transformation from one compound to another in both bound and unbound states [4] [3]. This fundamental difference dictates their respective applications in drug discovery.

RBFE calculations are most reliable for comparing congeneric series where compounds share a common scaffold with modest modifications [2] [3]. The chemical similarity enables efficient alchemical pathways with good numerical convergence [2]. In contrast, ABFE can be applied to structurally diverse compounds without requiring a common scaffold, making it suitable for virtual screening of diverse compound libraries [2] [3]. However, RBFE typically achieves higher accuracy (errors approaching 1 kcal/mol) for congeneric series, while ABFE generally has larger errors due to the more extensive transformations involved [6].

Computational Requirements and Performance

The computational demands of ABFE and RBFE differ significantly. A typical RBFE calculation for a series of 10 ligands requires approximately 100 GPU hours, while the equivalent ABFE experiment would require around 1000 GPU hours [3]. This order-of-magnitude difference stems from the more extensive sampling needed in ABFE to account for full ligand desolvation and binding site reorganization.

However, this direct comparison doesn't capture the full workflow efficiency picture. RBFE requires significant "tinkering and testing by scientists" to design optimal transformation networks, particularly for complex chemical series [3]. ABFE calculations for different ligands are independent, potentially enabling greater parallelization and more straightforward application to diverse compound sets [3].

Table 3: ABFE vs. RBFE Comparison for Binding Affinity Prediction

| Parameter | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Target | Standard binding free energy (ΔG°b) for individual ligands | Binding free energy difference (ΔΔG) between similar ligands |

| Chemical Scope | Structurally diverse compounds | Congeneric series (typically <10 heavy atom changes) |

| Typical Accuracy | Moderate (often >1 kcal/mol error) | High (~1 kcal/mol error for similar ligands) |

| Throughput | Suitable for virtual screening prioritization | Optimal for lead optimization series |

| Key Challenges | Standard state definition, pose generation, binding site volume | Transformation pathway design, core identification |

| Computational Cost | ~1000 GPU hours for 10 ligands | ~100 GPU hours for 10 ligands |

Successful implementation of ABFE calculations requires both software tools and theoretical frameworks. The following table summarizes key resources mentioned in recent literature:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for ABFE Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Packages (NAMD, GROMACS, OpenMM) | Simulation engine for sampling configurations | Core MD simulations and free energy calculations [5] [6] |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms (REMD, ABF, US) | Accelerate convergence of thermodynamic properties | Improve sampling efficiency in ABFE calculations [5] [6] |

| Structure Prediction Tools (Boltz-2) | Generate protein-ligand complex structures | ABFE when experimental structures unavailable [7] |

| Force Fields (CHARMM, AMBER, OpenFF) | Molecular mechanical potential functions | Describe intermolecular interactions and energies [5] [3] |

| System Preparation Tools (CHARMM-GUI, Protein Preparation Wizard) | Generate simulation-ready molecular systems | Structure preparation, solvation, ionization [2] [6] |

| Binding Restraint Methods (Boresch-style, flat-bottom) | Define binding site volume and orientation | Standard state definition and convergence [1] |

The field of absolute binding free energy calculations is rapidly evolving, with several promising directions emerging. Integration with machine learning approaches shows potential for accelerating ABFE calculations while maintaining accuracy [3]. Methods like Boltz-ABFE demonstrate the feasibility of performing ABFE calculations without experimental crystal structures by combining structure prediction with free energy calculations [7]. Additionally, active learning frameworks that strategically combine accurate but expensive FEP calculations with faster but less accurate methods like QSAR enable more efficient exploration of chemical space [3].

For drug discovery professionals, ABFE calculations offer particular promise for virtual screening applications where structurally diverse compounds must be prioritized [2] [3]. The ability to compute absolute affinities independently for each compound makes ABFE suitable for this early discovery phase, while RBFE remains the method of choice for lead optimization within congeneric series. As force fields continue to improve and sampling algorithms become more efficient, the domain of applicability for ABFE calculations will expand, potentially making them a standard tool for accelerating early-stage drug discovery [3] [7].

In the field of structure-based drug design, accurately predicting how tightly a small molecule binds to its protein target is a fundamental challenge. Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations have emerged as a powerful computational tool that addresses this challenge by precisely estimating the difference in binding affinity (ΔΔG) between similar ligands [8]. Unlike methods that predict the absolute binding strength of a single compound, RBFE focuses on comparative affinity differences within a series of related molecules. This approach is particularly valuable during hit-to-lead and lead optimization stages of drug discovery, where medicinal chemists make systematic chemical modifications to improve potency [8] [9]. By providing accurate predictions of how structural changes affect binding, RBFE calculations help prioritize which synthetic analogs are most likely to succeed, thereby reducing costly experimental trial-and-error [8].

Theoretical Foundation: The Principles of RBFE Calculations

The Alchemical Transformation Framework

RBFE calculations operate on the principle of "alchemical transformation," a computational process that gradually morphs one ligand into another within the binding site of the protein and in solution [8]. This transformation uses a coupling parameter, often denoted as lambda (λ), which smoothly interpolates between the molecular mechanics parameters of the initial and final ligands across multiple intermediate states [10]. The theoretical foundation relies on constructing a thermodynamic cycle that enables the calculation of ΔΔG without needing to directly simulate the physical binding and unbinding processes, which would be computationally prohibitive [11].

The fundamental thermodynamic cycle for RBFE calculations and the corresponding free energy relationship can be represented as follows:

Figure 1: Thermodynamic cycle for Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations. The difference in binding free energy, ΔΔG, is calculated as ΔG_bind(B) - ΔG_bind(A) = ΔG_protein - ΔG_water, avoiding direct simulation of physical binding processes.

The binding free energy difference is calculated as ΔΔGA→B = ΔGbind(B) - ΔGbind(A) = ΔGA→Bprotein - ΔGA→Bwater, where ΔGA→Bprotein and ΔGA→Bwater represent the free energy change for alchemically transforming ligand A to B in the protein binding site and in water, respectively [11]. This approach effectively bypasses the need to simulate the actual binding process.

Key Methodological Implementations

Several computational methodologies have been developed to implement RBFE calculations, each with distinct approaches to managing the alchemical transformations:

- Thermodynamic Integration (TI): A method that calculates free energy differences by numerically integrating the ensemble average of ∂H/∂λ along the alchemical pathway [12].

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): Utilizes a series of discrete λ windows to gradually transform one ligand into another, with the free energy change computed between adjacent windows [11].

- Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR): An optimized method for analyzing data between intermediate states to produce free energy estimates with minimal variance [10].

- Non-Equilibrium Switching (NES): An alternative approach that runs many short, independent simulations where λ is continuously driven from one end state to the other, offering high parallelization efficiency [9].

RBFE vs. ABFE: A Comparative Analysis

While RBFE calculations focus on relative differences between ligands, Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) methods aim to predict the binding affinity of a single ligand without a reference compound [2]. The distinction between these approaches has significant implications for their application in drug discovery pipelines.

Table 1: Comparison of RBFE and ABFE Calculation Methods

| Feature | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Target | Difference in binding free energy (ΔΔG) between related ligands | Standard binding free energy (ΔG) of a single ligand |

| Typical Application | Lead optimization within congeneric series | Virtual screening of diverse compounds |

| Chemical Space | Requires structural similarity between ligands | Applicable to structurally diverse compounds |

| Sampling Challenges | Limited by need for consistent binding mode | Requires sampling of full ligand (un)binding process |

| Common Implementations | FEP, TI, BAR, NES [8] [9] | Double-decoupling, Binding energy distribution [2] |

| Throughput | Higher for series of similar compounds | Lower, computationally intensive per compound |

| Pose Dependency | Requires consistent binding pose assumption | Needs accurate prediction of binding pose [2] |

ABFE calculations compute the standard binding free energy through processes that decouple the ligand from its environment [13]. These methods can be applied to structurally diverse compounds without requiring a reference molecule, making them potentially valuable for virtual screening applications [2]. However, they typically require more computational resources per compound and face challenges in sampling the full binding and unbinding processes [2]. Recent research demonstrates that ABFE calculations can successfully improve the enrichment of active compounds in virtual screening after initial docking, providing a valuable refinement step [2].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing RBFE Calculations

Standard RBFE Workflow

Implementing RBFE calculations requires a structured workflow to ensure reliable results. The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a typical RBFE protocol:

Figure 2: Standard workflow for Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations, showing the sequential steps from input preparation to final prediction.

Case Study: RBFE for GPCR Targets

A recent study applied RBFE calculations to G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs), challenging membrane protein targets that represent a significant proportion of modern drug targets [12]. The protocol employed two different RBFE methods: thermodynamic integration (TI) with AMBER and the alchemical transfer method (AToM) with OpenMM. Researchers calculated ΔΔG values for 53 transformations involving four class A GPCRs, systematically testing different numbers of simulation windows and varying simulation times to optimize the balance between reliability and computational cost [12]. The results demonstrated good agreement with experimental data, validating the applicability of RBFE methods for membrane protein targets [12].

Another study focusing on GPCRs utilized the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) method to predict binding affinities for agonists bound to β1 adrenergic receptor (β1AR) in both active and inactive states [10]. The calculations successfully captured the experimental trend where full agonists like isoprenaline showed significantly higher affinity for the active state, while weak partial agonists like cyanopindolol showed comparable affinity for both states [10]. The correlation between computational results and experimental pKD values was notably high (R² = 0.7893), demonstrating the predictive power of carefully implemented RBFE calculations [10].

Critical Implementation Considerations

Successful application of RBFE calculations requires attention to several critical factors:

- Ligand Pose Quality: The accuracy of RBFE predictions is highly dependent on the quality of initial ligand poses. A study testing automated pose generation found that maximum common substructure (MCS) constraints significantly improved reliability compared to unconstrained docking [9].

- Consistent Binding Mode: RBFE calculations typically assume a consistent binding mode across the congeneric series. Significant changes in binding orientation or conformation can challenge this assumption and reduce predictive accuracy [9].

- Sampling Adequacy: sufficient sampling of relevant conformational states is essential for convergence. Enhanced sampling techniques, such as replica exchange, can improve sampling but may not always dramatically increase accuracy compared to sufficient conventional sampling [11].

- Force Field Quality: As sampling methods improve, force field accuracy becomes increasingly important for predictive accuracy [11].

Performance Assessment: Quantitative Validation of RBFE Methods

RBFE calculations have been rigorously validated across multiple target classes and chemical series. The table below summarizes performance metrics from recent studies:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of RBFE Calculations from Recent Studies

| Target System | Method | Number of Transformations | Correlation with Experiment | Average Unsigned Error (AUE) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A GPCRs [12] | AMBER-TI & AToM-OpenMM | 53 | Good agreement with data | Not specified | Not specified |

| β1AR Agonists [10] | BAR | 8 transformations (4 agonists × 2 states) | R² = 0.7893 | Not specified | Not specified |

| P38α Kinase [9] | NES with MCS docking | 201 perturbations across systems | Correct trend recovered | 0.9 kcal/mol | 1.1 kcal/mol |

| PTP1B [9] | NES with MCS Vina | 201 perturbations across systems | Trend recovered (Kendal's τ = 0.1-0.47) | 0.8-1.1 kcal/mol | 1.1-1.5 kcal/mol |

| Thrombin [11] | FEP/MD | Series of 10 inhibitors | Within 1 kcal/mol | ~1 kcal/mol | Not specified |

These results demonstrate that modern RBFE calculations typically achieve accuracy levels of 1 kcal/mol or better, which is sufficient to inform medicinal chemistry decisions during lead optimization [8] [11]. The performance varies depending on the target, chemical series, and implementation details, but consistently provides significant enrichment over simpler docking methods.

Implementing RBFE calculations requires specialized software tools and computational resources. The following table outlines key components of the RBFE research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for RBFE Calculations

| Tool Category | Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | OpenMM, AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM [12] [10] | Core simulation engine for sampling | GPU acceleration critical for throughput |

| Free Energy Methods | Thermodynamic Integration, FEP, BAR, NES [12] [9] | Algorithms for ΔΔG calculation | Method choice affects precision/throughput balance |

| Automation Workflows | Icolos, Schrodinger FEP+ [9] | End-to-end automation from SMILES to ΔΔG | Reduces expert intervention needed |

| Docking & Pose Generation | Glide, AutoDock Vina [9] | Initial ligand pose generation | Core-constraint methods improve pose quality |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GAFF [12] [9] | Molecular mechanics parameters | Accuracy limits ultimate prediction quality |

| Enhanced Sampling | Replica Exchange, REST [9] | Improved conformational sampling | Can aid convergence for challenging transformations |

Relative Binding Free Energy calculations have matured into a valuable tool for drug discovery, providing reliable predictions of how structural modifications affect ligand binding affinity. When applied to congeneric series with consistent binding modes, RBFE methods achieve the accuracy needed to guide lead optimization decisions. The 1 kcal/mol accuracy threshold demonstrated in multiple studies translates to meaningful impact on experimental planning, helping researchers prioritize the most promising synthetic targets. While challenges remain in handling significant binding mode changes and achieving full automation, continued advancements in sampling algorithms, force fields, and workflow integration are further solidifying RBFE's role as a cornerstone of computational drug discovery.

In modern computer-aided drug design, alchemical binding free energy calculations have emerged as powerful tools for predicting protein-ligand affinities. These methods leverage thermodynamic cycles and molecular dynamics simulations to provide quantitative estimates of binding strengths, guiding decision-making in hit identification, lead optimization, and scaffold-hopping campaigns. The two primary computational approaches—Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations—differ fundamentally in their underlying thermodynamic pathways and domain of applicability. While RBFE calculations have become relatively established in lead optimization for comparing similar compounds, ABFE methods are gaining traction for their ability to evaluate diverse compounds independently. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, examining their respective thermodynamic foundations, performance characteristics, and optimal applications in drug discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations: Thermodynamic Cycles

Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Cycle

RBFE calculations exploit a thermodynamic cycle that enables the calculation of the binding free energy difference between two ligands (ΔΔGbind) by comparing the cost of alchemically transforming one ligand into another in both the bound and unbound states [14]. This approach avoids simulating the physically complex process of binding and unbinding directly.

The RBFE thermodynamic cycle operates on the principle that the difference in binding free energies between two ligands (ΔGbind,B - ΔGbind,A) equals the difference between the free energy cost of transforming ligand A to B in the bound state (ΔGbound) and in bulk solvent (ΔGunbound), forming a closed cycle where the net energy change is zero [14]. This relationship is expressed as ΔΔGbind = ΔGbound - ΔGunbound.

The alchemical transformation typically employs a coupling parameter λ that gradually interpolates between the Hamiltonians of the two endpoints, with λ=0 representing ligand A and λ=1 representing ligand B [15]. Intermediate λ values create hybrid molecules that possess characteristics of both ligands, enabling a numerically tractable pathway for the transformation.

Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) Cycle

ABFE calculations determine the standard binding free energy for a single ligand without requiring a reference compound. The most common approach, the Double Decoupling Method (DDM), uses an alchemical pathway to compute the work of decoupling the ligand from the binding site and the work of decoupling the ligand from pure solvent [16] [17].

The ABFE thermodynamic cycle involves annihilating the ligand in the bound state and then re-creating it in the unbound state, or vice versa [3]. In the bound state, the ligand is typically decoupled from its environment by first turning off electrostatic interactions followed by van der Waals parameters, while maintaining restraints to keep the ligand positioned in the binding site [3]. A corresponding process is performed in solution to compute the solvation free energy, with the difference providing the absolute binding free energy.

The Simultaneous Decoupling and Recoupling (SDR) method, a variant of DDM, avoids numerical artifacts with charged ligands by recoupling the ligand with bulk solvent at a distance while decoupling it from the binding site, maintaining constant net charge throughout the process [17].

Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison between ABFE and RBFE methods across various benchmark systems

| Performance Metric | ABFE Methods | RBFE Methods | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Accuracy | RMSE: 1.14-3.82 kcal/mol [18] | MUE: ~1.24 kcal/mol [14] | Performance is system-dependent |

| Correlation with Experiment | Spearman's r: 0.67±0.05 [18] | Good for congeneric series [14] | ABFE values from fragment optimization |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Diverse scaffolds [2] [17] | Congeneric series (≤10-atom change) [3] [14] | ABFE suitable for virtual screening |

| Computational Cost | ~1000 GPU hours for 10 ligands [3] | ~100 GPU hours for 10 ligands [3] | ABFE is typically 5-10x more expensive |

| Charge Change Handling | Challenging, but methods exist [3] [17] | Problematic, recommended to avoid [3] [14] | SDR method helps for ABFE [17] |

Optimal Applications in Drug Discovery

RBFE calculations are particularly well-suited for lead optimization stages where small, systematic chemical modifications are explored within a congeneric series [14]. Their high accuracy for predicting relative affinities of similar compounds makes them invaluable for deciding which synthetic analogs to prioritize. Successful applications include late-stage functionalization [14], where FEP calculations guided the synthetic prioritization of previously unexplored regions of PRC2 methyltransferase inhibitors, correctly predicting the potency of analogues with F, Cl, and NH₂ substitutions while avoiding synthesis of compounds with predicted activity loss.

ABFE calculations excel in scenarios requiring evaluation of structurally diverse compounds, making them suitable for hit identification and validation [2] [17]. They can reliably rank fragment-sized binders (Spearman's r = 0.89) [18] and improve enrichment of active compounds in virtual screening following docking [2]. ABFE methods also show promise in scaffold hopping applications, where RBFE approaches struggle due to large structural differences between compounds [14].

Limitations and Challenges

RBFE limitations primarily stem from the requirement for structural similarity between compounds. The technique becomes difficult or intractable for chemically distinct ligands due to challenges in designing alchemical pathways with good numerical convergence and the inability to sample pose interconversions during standard molecular dynamics simulations [2]. Additionally, changes in formal charge states during transformations remain problematic despite methodological advances [3] [14].

ABFE challenges include higher computational costs (typically 5-10 times more expensive than RBFE) [3] and sensitivity to starting poses [2] [17]. Achieving sufficient sampling of protein conformational changes and binding site water molecules can be difficult within practical computational budgets [3]. The accuracy of ABFE calculations also depends critically on force field quality, particularly for charged groups and complex molecular geometries [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard RBFE Protocol

A typical RBFE calculation involves these key steps:

System Preparation: Protein structures are prepared from crystallographic data or homology models, with careful attention to protonation states of binding site residues at the appropriate pH. Ligands are parameterized using force fields compatible with the protein force field [14] [2].

Perturbation Map Generation: A network of molecular transformations is created connecting all ligands in the series, with attention to minimizing the size of perturbations between neighboring nodes [3]. The number of λ windows is optimized automatically to balance accuracy and computational cost [3] [15].

Equilibration and Sampling: For each transformation, molecular dynamics simulations are run at multiple λ windows, with sampling times typically ranging from 10-50 ns per window depending on system complexity [19] [15]. Convergence monitoring is critical, with advanced workflows implementing on-the-fly optimization of resource allocation based on convergence metrics [15].

Analysis and Validation: Free energy differences are computed using estimators such as MBAR or TI, with cycle closure errors and hysteresis between forward and reverse transformations serving as quality controls [14]. Validation against known experimental data for a subset of compounds is recommended before prospective application [14].

Standard ABFE Protocol

A typical ABFE calculation follows this workflow:

Pose Generation and Preparation: Multiple plausible binding poses are generated through docking or from experimental structures when available [2] [17]. Ligand protonation states and tautomers are sampled appropriately for the experimental conditions.

Restraint Setup: Orientational and conformational restraints are applied to maintain the ligand in the binding site during decoupling [16] [17]. Boresch-style restraints are commonly used, with their free energy contribution accounted for in the final calculation.

Decoupling Pathway Simulation: The ligand is decoupled from its environment through a series of λ windows, typically involving: (a) turning off electrostatic interactions, (b) turning off van der Waals interactions, and (c) applying/removing restraints [3] [17]. The same process is simulated in solution.

Free Energy Estimation: The binding free energy is calculated as ΔGbind = ΔGcomplex - ΔGsolvent + ΔGcorrections, where ΔGcomplex and ΔGsolvent represent the decoupling free energies in the complex and solution states, respectively, and ΔGcorrections accounts for restraint contributions and standard state corrections [17].

Table 2: Computational tools and resources for binding free energy calculations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Compatibility/Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| BAT.py [17] | Automated ABFE calculations | AMBER, Python, GPU recommended |

| FEP+ [14] | Commercial RBFE/ABFE platform | Schrödinger Suite, GPU accelerated |

| OpenMM [15] | MD engine for custom free energy protocols | Python API, GPU support |

| CHARMM-GUI [6] | System setup for FEP/ABFE | CHARMM, NAMD, AMBER |

| Open Force Field [3] | Improved ligand force field parameters | Compatible with major MD engines |

Emerging Methodologies and Future Directions

Hybrid and Automated Approaches

Recent advances focus on automating workflows to reduce human effort and increase reproducibility. Tools like BAT.py automate the entire ABFE process from structure preparation to result analysis, supporting multiple methods including DD, APR, and SDR [17]. Similarly, on-the-fly optimization protocols for TI simulations can reduce computational expenses by more than 85% while maintaining accuracy through automatic equilibration detection and convergence testing [15].

Active learning frameworks that combine FEP with faster but less accurate methods like 3D-QSAR are demonstrating significant efficiency gains [3]. In these workflows, FEP provides accurate binding predictions for a subset of molecules, while QSAR methods rapidly predict affinities for larger compound sets. Promising candidates identified by QSAR are then added to the FEP set iteratively until no further improvements are found.

Machine Learning and Enhanced Sampling

Machine learning potentials are showing promise for achieving sub-1 kcal/mol accuracies in RBFE calculations, potentially surpassing traditional force field limitations [20]. These approaches combine the physical rigor of molecular dynamics with the accuracy of quantum mechanics through neural network potentials.

Implicit solvent models with enhanced sampling techniques are being developed to address the high computational costs of ABFE calculations [16]. While current GB models show systematic errors for certain functional groups, particularly charged moieties, they offer significantly faster sampling and avoid challenges associated with explicit water molecules.

Both ABFE and RBFE calculations provide valuable, complementary approaches for predicting protein-ligand binding affinities in drug discovery. RBFE methods offer higher accuracy and efficiency for evaluating congeneric series in lead optimization, while ABFE methods provide the flexibility to evaluate diverse compounds in early discovery stages. The choice between them should be guided by the specific drug discovery context, chemical space under investigation, and available computational resources. As automation, force fields, and sampling algorithms continue to improve, these alchemical methods are poised to play an increasingly central role in rational drug design pipelines.

Accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding affinities is a fundamental objective in computational drug discovery. Among the most rigorous approaches for achieving this are alchemical free energy methods, primarily Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI). These techniques compute free energy differences by simulating non-physical (alchemical) pathways that connect physical states of interest, allowing researchers to predict binding affinities with remarkable accuracy [21] [22]. Within this domain, a crucial distinction exists between Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations, which predict affinity differences between similar compounds, and Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations, which predict the binding affinity of a single ligand directly [3] [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of FEP and TI, examining their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications in modern drug discovery research.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Comparison

Fundamental Principles

FEP and TI are based on statistical mechanics and share a common underlying principle: the use of a coupling parameter (λ) to define a continuous pathway between two thermodynamic states. However, they differ significantly in their implementation and numerical approach.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) relies on the Zwanzig equation, which expresses the free energy difference between two states as a function of the energy difference sampled from one state [21] [22]. In practice, FEP calculates the free energy difference between states A and B using the formula: ΔA = -kB T ln⟨exp(-(EB - EA)/kB T)⟩A where kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, EA and EB are the potential energies of states A and B, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average taken from simulations of state A [22].

Thermodynamic Integration (TI) employs a different approach by integrating the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ over the alchemical pathway [21]. The fundamental TI equation is: ΔA = ∫₀¹ ⟨∂H(λ)/∂λ⟩_λ dλ where H(λ) is the system Hamiltonian as a function of the coupling parameter λ [23]. This method requires evaluation of the ensemble average of the derivative at multiple intermediate λ values between 0 and 1.

Comparative Theoretical Framework

Table 1: Fundamental Theoretical Differences Between FEP and TI

| Aspect | Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Thermodynamic Integration (TI) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Equation | Zwanzig equation [22] | Kirkwood's thermodynamic integration [22] |

| Sampling Requirement | Requires substantial overlap between successive states | Less dependent on state-to-state overlap |

| Numerical Implementation | Uses exponential averaging, which can be problematic for large perturbations | Numerical integration of ensemble averages |

| Force Evaluation | Requires only potential energy differences | Requires derivatives of the Hamiltonian with respect to λ |

| Error Estimation | Straightforward via bootstrap or block averaging | More complex due to integration process |

Performance Benchmarking and Accuracy Assessment

Predictive Accuracy in Real-World Applications

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies provide compelling evidence for the predictive capabilities of both FEP and TI in drug discovery contexts. The implementation of advanced sampling techniques has been crucial for achieving high accuracy with both methods.

The SPONGE-FEP framework, which incorporates selective integrated tempering sampling (SITS), demonstrates the current state-of-the-art for FEP, achieving accuracy comparable to commercial tools like FEP+ while requiring only approximately 4 hours of computation per ligand pair on an A100 GPU [24]. This automated workflow generates perturbation maps, performs alchemical free energy calculations, and conducts cycle closure analysis, significantly enhancing sampling efficiency for rare events during alchemical transformations [24].

For RBFE calculations, comprehensive validation studies show impressive performance. One analysis of eight benchmark test cases (including BACE, CDK2, JNK1, MCL1, P38, PTP1B, Thrombin, and TYK2) revealed that FEP implementations can achieve edgewise mean unsigned errors (MUEs) of approximately 0.90 kcal/mol with respect to experimental measurements [22]. TI validation on the same dataset showed a slightly larger overall edgewise MUE of 1.17 kcal/mol based on cycle closure ΔΔG [22].

Performance in Challenging Systems

Both methods face challenges with specific molecular systems, particularly those involving charge changes, significant conformational rearrangements, or highly flexible ligands. A large-scale benchmarking study on multimeric ATPases examined RBFE calculations across 55 interfacial binding sites in six diverse systems (F1-ATPase, MalK, MCM, Rho, FtsK, and gp16) [25]. The results demonstrated that success rates varied significantly based on system characteristics: RBFE reproduced experimentally observed binding preferences for 91% of sites in systems with low structural deviations (F1-ATPase, MalK, MCM), but agreement dropped to only 60% for systems with greater structural variability (Rho, FtsK, gp16) [25].

The highly charged and conformationally flexible nature of nucleotide ligands necessitated extensive sampling (>20 ns per alchemical window) to account for slow relaxation associated with long-range electrostatic interactions [25]. This highlights a common challenge for both FEP and TI when dealing with complex biomolecular systems.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Different Ligand and Target Types

| System Characteristic | FEP Performance | TI Performance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congeneric Ligands | Excellent (MUE ~0.9 kcal/mol) [22] | Good (MUE ~1.2 kcal/mol) [22] | Both methods suitable for lead optimization |

| Charge-Changing Perturbations | Challenging, requires careful setup [3] | Challenging, requires careful setup [3] | Longer simulations and charge correction schemes needed |

| Macromolecular Targets | Variable success (60-91% depending on flexibility) [25] | Variable success (similar to FEP) [25] | System flexibility major factor in accuracy |

| Nucleotide Ligands | Requires >20 ns/window sampling [25] | Requires >20 ns/window sampling [25] | Slow electrostatic relaxation demands extensive sampling |

Computational Protocols and Methodological Implementation

Workflow and Sampling Enhancement

Modern implementations of both FEP and TI share common workflow elements while employing distinct sampling enhancement strategies. A typical automated workflow includes system preparation, perturbation map generation, alchemical free energy calculations, and cycle closure analysis [24].

Advanced sampling techniques are critical for both FEP and TI to overcome energy barriers and ensure convergence. The SPONGE-FEP framework implements Selective Integrated Tempering Sampling (SITS) to significantly improve sampling efficiency of rare events during alchemical transformations [24]. Similarly, Hamiltonian replica exchange methods, including Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (REST) or REST2, are widely used to enhance conformational sampling by reducing energy barriers between adjacent λ states [22].

Lambda Scheduling and Window Optimization

A critical implementation detail for both FEP and TI is the selection of λ values, which define the intermediate states along the alchemical pathway. Modern approaches have moved beyond fixed λ schedules to adaptive methods that optimize the number and spacing of λ windows based on the specific chemical transformation [3].

Traditional approaches relied on researcher intuition to "guess" the number of lambda windows required based on transformation complexity, often leading to recalculations due to poor convergence [3]. Contemporary implementations use short exploratory calculations to automatically determine optimal λ scheduling, reducing both computational waste and researcher frustration [3]. This automation is particularly valuable for charge-changing perturbations, which typically require more closely spaced λ windows and longer simulation times to achieve convergence [3].

Force Fields and Parameterization Requirements

Force Field Selection and Impact on Accuracy

The choice of force field parameters significantly influences the accuracy of both FEP and TI calculations. Comparative studies have systematically evaluated various protein force fields, water models, and partial charge methods to determine optimal combinations.

Table 3: Force Field and Parameter Evaluation for Free Energy Calculations

| Parameter Type | Options Tested | Performance Impact | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Force Field | AMBER ff14SB [22], AMBER ff15ipq [22], CHARMM [25], OPLS [22] | Moderate effect on accuracy | AMBER ff14SB provides reliable performance; ff15ipq may offer improvements for specific systems |

| Water Model | TIP3P [22], SPC/E [22], TIP4P-Ewald [22] | Significant for hydration free energies | TIP3P offers best balance of accuracy and computational efficiency |

| Ligand Partial Charges | AM1-BCC [22], RESP [22] | Critical for electrostatic interactions | RESP charges generally more accurate but computationally demanding; AM1-BCC good for high-throughput |

| Ligand Force Field | GAFF2.11 [22], OPLS2.1 [22], OpenFF [3] | Major impact on ligand conformational preferences | GAFF2.11 performs well with AMBER protein force fields |

A comprehensive assessment of five different parameter sets found that the combination of AMBER ff14SB protein force field with GAFF2.11 for ligands and TIP3P water model provides robust performance across multiple benchmark systems [22]. The study also revealed that the AMBER ff15ipq force field, derived using implicitly polarized charges, offered potential improvements for specific targets but did not consistently outperform ff14SB across all test cases [22].

Specialized Parameterization for Challenging Cases

Standard force fields often struggle with particular chemical functionalities, necessitating specialized parameterization approaches. Torsion parameters for specific ligand motifs can be improved through quantum mechanics (QM) calculations to achieve more accurate conformational behavior [3]. This is particularly important for FEP and TI, where incorrect torsional profiles can propagate large errors in binding affinity predictions.

The development of the Open Force Field (OpenFF) initiative represents a significant community effort to create more accurate ligand force fields that integrate seamlessly with macromolecular force fields like AMBER or CHARMM [3]. Ongoing challenges include modeling covalent inhibitors and ensuring consistent interactions between ligand and protein parameter sets [3].

Software and Computational Platforms

Multiple software platforms implement FEP and TI methodologies with varying features and accessibility. SPONGE-FEP represents an automated academic implementation that incorporates selective integrated tempering sampling for enhanced efficiency [24]. Schrödinger's FEP+ is a widely used commercial platform employing the OPLS2.1 force field and REST2 enhanced sampling [22]. OpenMM provides open-source capabilities for both FEP and TI, enabling customizable free energy workflows [22]. AMBER includes thermodynamic integration capabilities and has been validated on benchmark datasets [22].

Specialized Methodologies for Specific Scenarios

Several specialized methodological advances address particular challenges in free energy calculations. Grand Canonical Non-equilibrium Candidate Monte-Carlo (GCNCMC) techniques enable simultaneous addition/removal of water molecules during simulations, ensuring proper hydration of binding sites [3]. Active Learning FEP combines FEP with 3D-QSAR methods to efficiently explore large chemical spaces, using FEP results to train faster QSAR models for initial screening [3]. Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) methods, while computationally more demanding than RBFE (approximately 10x more GPU hours), enable direct binding affinity prediction without requiring a reference compound [3].

Free Energy Perturbation and Thermodynamic Integration provide complementary approaches for predicting binding affinities in drug discovery. FEP implementations with enhanced sampling techniques like SITS or REST2 currently demonstrate slightly superior performance for congeneric series in lead optimization [24] [22]. TI remains a robust alternative with strong theoretical foundations and competitive accuracy [22].

The choice between FEP and TI often depends on specific research requirements, available computational resources, and system characteristics. For standard lead optimization applications with congeneric compounds, FEP with advanced sampling provides excellent accuracy and efficiency. For systems requiring careful integration of free energy derivatives or specific methodological approaches, TI may be preferred. Both methods continue to evolve with improvements in force fields, sampling algorithms, and workflow automation, further solidifying their role as essential tools in modern computational drug discovery.

Strategic Deployment: When and How to Use ABFE and RBFE in Drug Discovery

The accurate prediction of how tightly a small molecule binds to its protein target is a cornerstone of computational drug discovery. Among the most rigorous physics-based methods available, Alchemical Binding Free Energy (BFE) calculations are primarily implemented through two distinct approaches: Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations. While RBFE has become a valued tool for lead optimization, its application is largely confined to comparing chemically similar molecules within a congeneric series [14] [2]. This limitation creates a significant gap in early discovery stages, where researchers need to evaluate chemically diverse compounds, such as those from virtual screens, or weak-binding fragments. ABFE methods directly calculate the standard binding free energy of a single ligand-receptor complex, without the need for a reference compound [6]. This capability positions ABFE as a powerful technique for applications beyond the scope of RBFE, namely the virtual screening of diverse compound libraries and the initiation of fragment-based drug design (FBDD) campaigns. This guide provides an objective comparison of ABFE and RBFE, detailing their performance, optimal domains of application, and the experimental protocols that underpin their use in modern drug discovery.

Methodological Comparison: Understanding the Core Techniques

Fundamental Thermodynamic Principles

The distinction between ABFE and RBFE originates from their underlying thermodynamic cycles.

- Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE): This method exploits the fact that free energy is a state function. It calculates the difference in binding free energy between two ligands by alchemically transforming one ligand into another, both within the protein's binding site and in aqueous solution [14]. Because the cycle is closed, the net free energy change for the physical binding process difference can be derived from the non-physical alchemical transformations. This approach is highly accurate for small, conservative changes but becomes intractable for large scaffold changes.

- Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE): This method directly calculates the standard binding free energy for a single ligand. One common approach, the Double Decoupling Method (DDM), involves alchemically decoupling the ligand from its environment in two steps: first from the solvated protein complex, and then from the bulk solvent [3] [16]. The difference in these free energies yields the absolute binding affinity. This process is computationally more demanding than RBFE but does not require a structural or chemical reference.

The workflow below illustrates the contrasting pathways of RBFE and ABFE calculations, from their initial setup to their final affinity prediction.

Direct Performance Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of ABFE and RBFE based on current literature and benchmark studies, highlighting their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Table 1: Performance and Characteristics of ABFE vs. RBFE

| Feature | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Domain | Virtual screening of diverse compounds [2], fragment-based design [14], scaffold hopping [14]. | Lead optimization within a congeneric series [14] [2]. |

| Typical Accuracy | Generally lower than RBFE; accuracy is system-dependent and can be <1.0 kcal/mol in ideal cases [6]. | High; average MUE of ~1.24 kcal/mol reported in prospective drug discovery projects [14]. |

| Computational Cost | High. For a series of 10 ligands, can require ~1000 GPU hours [3]. | Lower than ABFE. For a series of 10 ligands, typically requires ~100 GPU hours [3]. |

| Ligand Requirements | Can be applied to any single compound, regardless of scaffold. | Requires a closely related pair of ligands; often limited to a ~10-atom change [3] [14]. |

| Dependence on Reference Compound | No. Each ligand is calculated independently. | Yes. Accuracy depends on the choice of a high-quality reference structure and ligand. |

| Key Challenges | Adequate sampling of protein/ligand states [6], high computational cost, offset errors from unaccounted protein reorganization [3]. | Limited chemical scope, difficulty with large scaffold changes or different binding poses [2]. |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Data

Protocol for ABFE-Based Virtual Screening

A study by Scientific Reports provides a clear protocol for using ABFE to enrich active compounds in virtual screening, a task where RBFE is not readily applicable [2]. The workflow is designed to maximize efficiency by using a fast method to generate initial candidates and a rigorous ABFE method to refine the selection.

System Preparation:

- Protein Preparation: A high-quality co-crystal structure of the target protein is prepared using a tool like the Protein Preparation Wizard. This includes assigning protonation states appropriate for the experimental pH of the binding assay.

- Ligand Library Preparation: A diverse library of active and decoy compounds (e.g., from DUD-E) is processed. Tools like LigPrep are used to generate likely protonation states, tautomers, and stereoisomers for each compound, incorporating a penalty term for less stable forms.

Baseline Docking:

- All candidate forms of each ligand are docked into the prepared protein structure using a standard docking program (e.g., Glide SP).

- The best docking score across all forms for a compound is taken as its final score. The top-ranking compounds are selected for further analysis.

Pose Equilibration and Selection:

- For the top-scoring compounds, multiple (e.g., ten) docked poses are subjected to a short molecular dynamics (MD) simulation for equilibration.

- Poses that move away from the binding site during equilibration are discarded, ensuring only stable poses proceed to the costly ABFE stage.

Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculation:

- Full ABFE calculations are performed on the best remaining poses. To ensure robustness, each calculation is run in duplicate with different random number seeds.

- The calculated ABFE values are used to re-rank the compounds.

Validation:

- Enrichment of known active compounds over decoys is calculated. The study demonstrated that ABFE calculations consistently improved enrichment over the baseline docking results for targets like BACE1, CDK2, and thrombin [2].

Protocol for ABFE in Fragment-Based Drug Design

Fragments are very weak binders, making their affinity prediction challenging. ABFE can be used to rank fragments and guide their optimization.

Fragment Identification: A library of small, diverse fragments is screened against the target. This can be done experimentally or computationally using methods like Grand Canonical Nonequilibrium Candidate Monte Carlo (GCNCMC), which efficiently finds fragment binding sites and modes by allowing fragments to be inserted and deleted from the protein environment during a simulation [26].

Binding Mode Determination: The binding poses of fragment hits are elucidated, typically via X-ray crystallography or from the output of computational screening methods like GCNCMC [26].

Affinity Prediction with ABFE: Standard alchemical ABFE calculations are run on the fragment-protein complexes. A key challenge is that weakly bound fragments are mobile, making it difficult to apply the restraints required in many ABFE protocols. GCNCMC can also be adapted to calculate binding affinities directly without the need for such restraints [26].

Validation and Growth: The predicted affinities are used to rank fragments. Promising fragments are then grown or linked, with ABFE potentially used to predict the affinity of the resulting larger molecules, as demonstrated in studies of fragment linking [14].

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below compiles key performance metrics for ABFE calculations from recent studies, providing a snapshot of its current capabilities in various applications.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of ABFE in Various Applications

| Study Context | System / Target | Reported Performance Metric | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening Refinement [2] | BACE1, CDK2, Thrombin (DUD-E) | Improved enrichment of active compounds over docking alone. | ABFE successfully differentiated true actives from decoys after an initial docking screen. |

| Fragment Affinity Prediction [14] | 8 protein systems, 90 fragments | RMSE of 1.1 kcal/mol vs. experiment. | ABFE can predict fragment binding affinities with accuracy close to the generally accepted limit of ~1 kcal/mol. |

| Multi-Target Selectivity Profiling [6] | Dasatinib/Imatinib bound to 11 kinase structures | Case study on calculating selectivity profiles. | Highlighted the potential of ABFE for off-target prediction, though also noted challenges with convergence in some systems. |

| Carbohydrate-Lectin Binding [27] | Carbohydrate ligands to Concanavalin A | Binding affinities estimated with "good accuracy and acceptable precision". | Demonstrated the applicability of ABFE to complex, understudied systems like carbohydrate-protein interactions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of ABFE calculations requires a suite of software tools and methods. The following table details key solutions used in the research cited throughout this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ABFE Calculations

| Tool / Method Name | Type | Primary Function in ABFE | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCNCMC [26] | Sampling Method | Enhances sampling of fragment binding and water placement by allowing molecule insertion/deletion. | Accelerating fragment-based drug discovery by efficiently finding occluded binding sites and multiple binding modes [26]. |

| Boltz-ABFE Pipeline [28] | Structure Prediction & Workflow | Predicts protein-ligand complex structures from sequence and SMILES, then runs ABFE. | Enabling ABFE for targets without experimental crystal structures, expanding its domain of applicability [28]. |

| Implicit Solvent DDM Workflow [16] | Automated Workflow | Performs ABFE using the Double Decoupling Method with implicit solvent to reduce cost and complexity. | Fast, automated binding affinity calculations for host-guest systems; a step towards more efficient screening [16]. |

| FEP/REMD [6] | Simulation Protocol | Combines Free Energy Perturbation with Replica Exchange MD to improve sampling and avoid local minima. | Calculating absolute binding free energies for drugs like dasatinib across multiple protein targets [6]. |

| Open Force Field Initiative [3] | Force Field Development | Develops accurate, open-source force fields for small molecules to improve simulation accuracy. | Providing improved molecular descriptions for FEP simulations, leading to more reliable results [3]. |

Integrated Workflow for Early-Stage Drug Discovery

The following diagram synthesizes the methodologies discussed into a coherent strategy for employing ABFE in the early stages of drug discovery, from hit identification to lead optimization.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide clearly delineates the domains of ABFE and RBFE. RBFE remains the gold-standard for optimizing potency within a congeneric series during lead optimization, offering high accuracy and computational efficiency for this specific task. In contrast, ABFE has emerged as a uniquely powerful tool for the earlier stages of drug discovery. Its ability to predict the absolute binding affinity of chemically diverse compounds makes it invaluable for refining virtual screening hits and for evaluating fragments in FBDD, where no common scaffold exists for RBFE. While challenges remain—particularly around computational cost, sampling, and the need for robust automated workflows—advancements in methods like GCNCMC, machine learning-based structure prediction, and implicit solvent models are rapidly expanding the feasibility and accuracy of ABFE. For research teams aiming to accelerate the discovery of novel chemical matter, integrating ABFE into an early-stage workflow provides a critical, physics-based capability to prioritize the most promising candidates from vast and diverse chemical spaces.

Accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity is fundamental to drug discovery, particularly during the hit-to-lead and lead optimization phases where medicinal chemists make small modifications to compound scaffolds to enhance potency and drug-like properties [29]. Among computational techniques, Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations have gained prominence for their ability to deliver reliable binding affinity estimates across congeneric series [29]. This guide objectively examines the domain of RBFE calculations, comparing performance across methodological approaches and contrasting them with Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) methods to clarify their respective roles in modern drug discovery pipelines.

RBFE methods strike a strategic balance between accuracy and throughput, typically utilizing molecular dynamics with alchemical perturbations to calculate free energy differences between similar ligands [30]. While ABFE methods offer greater freedom in ligand selection and can operate without a congeneric series, they come with significantly higher computational demands—approximately 10 times more expensive than RBFE for comparable series [3]. This efficiency advantage positions RBFE as the preferred method for lead optimization where congeneric series are available and rapid iteration is valuable.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarking Across Methods

Accuracy Metrics Across Force Fields and Protein Targets

Extensive benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the performance characteristics of RBFE methodologies. The table below summarizes key performance indicators across different computational approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RBFE Calculation Methods

| Method Category | Specific Method/Force Field | Reported Accuracy | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials | QuantumBind-RBFE (AceFF 1.0) | Improved accuracy vs. GAFF2 & ANI2-x; Comparable correlation to OPLS4 [29] | Broad chemical applicability; Supports charged molecules; 2fs timestep for speed [29] | Limited to ligand charges -1, 0, +1 [29] |

| Traditional Force Fields | GAFF2 (Molecular Mechanics) | Lower accuracy than AceFF 1.0 [29] | Computational efficiency; Established parameters [25] | Struggles with rare chemical groups; Limited polarization effects [29] |

| Traditional Force Fields | OPLS4 | Comparable correlations to AceFF 1.0 [29] | Industry standard; Well-validated [29] | Less accuracy than AceFF in some benchmarks [29] |

| Fixed-Charge Force Fields | AMBER (for nucleotide binding) | 88.9% of RBFE results within ±3 kcal/mol of experiment [25] | Feasible for large systems; Extensive sampling possible [25] | Challenged by highly charged, flexible ligands [25] |

| Machine Learning Scoring | CNN Siamese Network | Pearson's R: 0.553 (variable by protein family) [30] | High throughput; Direct from structure [30] | Performance varies by protein family [30] |

Performance Across Diverse Target Classes

RBFE performance varies significantly based on system characteristics. For multimeric ATPases—complex systems with interfacial binding sites—RBFE calculations successfully reproduced experimental binding preferences for 91% of sites in well-behaved systems (F1-ATPase, MalK, MCM) with low structural deviations [25]. However, agreement dropped to 60% for systems with greater structural variability (Rho, FtsK, gp16), highlighting the impact of protein flexibility and conformational stability on predictive accuracy [25].

The highly charged and flexible nature of certain ligands, particularly nucleotides with charged phosphate groups, necessitates extensive sampling (>20 ns per alchemical window) to account for slow relaxation associated with long-range electrostatic interactions [25]. This presents both a computational challenge and an important consideration for method selection.

Methodological Protocols: Implementing RBFE Calculations

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for RBFE calculations, highlighting key stages from system preparation through free energy analysis:

Key Experimental Protocols

NNP/MM Hybrid Approach (QuantumBind-RBFE)

The NNP/MM (neural network potential/molecular mechanics) scheme combines high-accuracy neural network potentials for ligand interactions with classical molecular mechanics for the protein environment [29]. The total potential energy (V) is calculated as:

V(r→) = VNNP(r→NNP) + VMM(r→MM) + VNNP-MM(r→)

where VNNP describes the ligand's intramolecular interactions using the NNP, VMM accounts for classical MM contributions of the protein and solvent, and VNNP-MM represents nonbonded interactions between ligand and environment computed using MM [29]. This mechanical embedding approach captures ligand internal strain at a higher level of theory while maintaining computational efficiency for the protein environment.

λ-Dynamics for Pose Ranking

For challenging scenarios involving core flipping or alternative binding poses, λ-dynamics methodologies enable rank ordering of different poses [31]. This approach employs a dual-topology model where each pose represents an end-state in a multisite λ dynamics (MSλD) calculation [31]. Distance restraints maintain poses in the binding site, with restraint contributions accounted for via one-step perturbation (OSP) methods [31]. This allows direct comparison of binding affinities between alternative poses when experimental structural data is limited.

Handling Charged Ligands

Transformations involving formal charge changes present particular challenges in RBFE calculations. Recommended approaches include introducing a counterion to neutralize charged ligands to maintain consistent formal charge across perturbations [3]. Additionally, running longer simulations for charge-changing transformations improves reliability, compensating for slower electrostatic relaxation [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RBFE Calculations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials | AceFF 1.0 [29], ANI-2x [29], MACE [29] | Machine-learned force fields for accurate ligand energetics |

| Traditional Force Fields | GAFF2 [29], OPLS4 [29], AMBER [25], CHARMM [25] | Classical molecular mechanics parameters |

| Sampling Algorithms | Alchemical Transfer Method (ATM) [29], λ-dynamics [31], GCNCMC [3] | Enhanced sampling for free energy calculations |

| Benchmark Datasets | JACS/Schrödinger dataset [29], BindingDB 3D [30] | Experimental reference data for validation |

| Specialized Software | TorchMD-Net [29], CHARMM [31], Custom in-house pipelines | Execution of complex RBFE simulations |

Comparative Analysis: RBFE vs. ABFE in Practical Applications

Strategic Considerations for Method Selection

The choice between RBFE and ABFE methods involves important trade-offs. The following diagram illustrates the key decision factors and appropriate application domains for each approach:

Domain Limitations and Practical Constraints

RBFE calculations maintain practical limitations that guide their appropriate application. The technique is generally limited to a maximum of 10 heavy atom changes between ligand pairs, though careful planning can sometimes extend this boundary [30]. Success depends heavily on structural fidelity and pose stability, with performance degradation occurring in systems with high protein flexibility or significant conformational variability [25].

Proper hydration environment consistency is critical, as discrepancies can lead to hysteresis between forward and reverse transformations [3]. Techniques such as 3D-RISM analysis and Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCNCMC) help ensure appropriate hydration [3]. Additionally, lambda window selection has evolved from empirical guessing to automated scheduling algorithms that optimize sampling efficiency [3].

RBFE calculations have established a definitive domain within the hit-to-lead and lead optimization landscape, offering an optimal balance of accuracy and efficiency for congeneric series. The ongoing evolution of force fields, particularly through neural network potentials, continues to address historical limitations in chemical space coverage and accuracy [29]. Emerging methodologies that combine RBFE with machine learning approaches like active learning frameworks promise to further expand the utility of these methods in drug discovery pipelines [3] [30].

While ABFE methods maintain distinct advantages for diverse chemical space exploration and hit identification [3], RBFE remains the workhorse for lead optimization where congeneric series enable precise relative affinity predictions. The continuing benchmarking across diverse target classes [25] and the development of specialized approaches for challenging scenarios like pose ranking [31] ensure that RBFE methodologies will remain essential components of the computational drug discovery toolkit.

Calculating protein-ligand binding free energies is a critical component of structure-based drug design. Among rigorous physics-based methods, two predominant approaches have emerged: Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations [14]. While both are alchemical methods rooted in statistical mechanics, they answer different questions and are suited to distinct stages of the drug discovery pipeline. ABFE calculations directly yield the standard binding free energy of a single ligand for a protein receptor, effectively measuring the reversible work of moving the ligand from bulk solvent to the binding site [2] [14]. In contrast, RBFE calculations yield the difference in binding free energies between two related compounds by computing the free energy change of alchemically transforming one ligand into another, both in the binding site and in solution [2] [14]. This fundamental difference dictates their practical applications: ABFE can evaluate diverse, non-congeneric compounds independently, while RBFE is ideally suited for optimizing series of chemically similar molecules. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these methods, focusing on practical workflows from initial virtual screening refinement with ABFE to automated congeneric series optimization with RBFE, supported by experimental data and implementation protocols.

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Workflows

Thermodynamic Cycles and Alchemical Pathways

The methodological distinction between ABFE and RBFE is most clearly understood through their respective thermodynamic cycles [14].

Figure 1: Thermodynamic cycles for Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE, left) and Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE, right) calculations. The RBFE cycle computes binding free energy differences between related compounds, while the ABFE cycle directly calculates the absolute binding affinity for a single compound.

The RBFE approach (left cycle) exploits the fact that free energy is a state function. The difference in binding free energies (ΔΔG_bind) between two ligands is calculated as the difference between the alchemical transformation free energies in the binding site (ΔG1) and in solution (ΔG2) [14]. This method is computationally efficient for comparing similar compounds but requires a reference compound with known affinity. The ABFE approach (right cycle) involves calculating the reversible work of completely decoupling the ligand from its environment—first from the binding site, then from solution [14]. Although computationally more demanding, ABFE provides a direct absolute measurement without requiring a reference compound.

Practical Implementation Workflows

Practical implementation of these methods follows structured workflows that integrate molecular dynamics simulations with free energy calculations.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow from initial virtual screening using ABFE to lead optimization using RBFE. The process begins with diverse compound screening and progresses to focused optimization of congeneric series.

The ABFE refinement workflow (left path) begins with docking a diverse compound library, followed by pose equilibration and validation through molecular dynamics, before running full ABFE calculations to identify true actives [2]. The RBFE mapping workflow (right path) takes these identified actives, groups them into congeneric series, and performs automated RBFE calculations to precisely rank affinity changes resulting from chemical modifications [14].

Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of ABFE and RBFE methods across various drug discovery applications.

| Application Context | Method | Correlation with Experiment | RMSE (kcal/mol) | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|