Advanced Data Collection Strategies for Protein Crystallography: A 2025 Guide from Foundations to AI Integration

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern data collection strategies in protein crystallography, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Advanced Data Collection Strategies for Protein Crystallography: A 2025 Guide from Foundations to AI Integration

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern data collection strategies in protein crystallography, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles and the evolution towards serial methods at synchrotron and XFEL sources. The guide details current sample delivery technologies focused on reducing sample consumption, offers practical troubleshooting for common issues like radiation damage and crystal quality, and explores validation through integrative approaches and AI-powered tools. The content synthesizes the latest advancements to equip scientists with the knowledge to design efficient, successful crystallography campaigns for complex biological targets.

Protein Crystallography Foundations: From Classic Techniques to the Serial Revolution

X-ray crystallography is a foundational technique in structural biology, providing atomic-level insights into the three-dimensional structures of proteins and other biological macromolecules. This knowledge is crucial for elucidating functional mechanisms, understanding disease pathologies, and guiding rational drug design [1]. The technique relies on the principle that a crystal, composed of a repeating, ordered array of molecules, can scatter X-rays to produce a diffraction pattern. The core process involves transforming this pattern into an electron density map and, subsequently, a molecular model [1].

A fundamental challenge in this process is the phase problem. In an X-ray diffraction experiment, detectors can measure the amplitude of each diffracted wave (derived from the intensity of the diffraction spot) but cannot directly record its phase—the positional shift of the wave relative to the origin. Phases contain critical information about the positions of atoms within the crystal lattice. Without them, it is impossible to calculate an accurate electron density map and solve the structure [2]. This application note details the core principles of X-ray diffraction and the experimental strategies, including solutions to the phase problem, employed in modern protein crystallography research.

Core Principles of X-Ray Diffraction

The Physical Basis of Diffraction

When a crystal is exposed to an X-ray beam, the electrons of the atoms within the crystal scatter the X-rays. In a perfectly ordered crystal, this scattering results in constructive and destructive interference, producing a distinct pattern of discrete diffraction spots. This phenomenon is described by Bragg's Law:

λ = 2d sinθ

Where λ is the wavelength of the X-rays, d is the distance between parallel crystal planes, and θ is the angle of incidence at which diffraction occurs [1] [3]. This relationship is elegantly visualized using the Ewald sphere construction [3]. In this model, the incident X-ray beam is represented by a sphere of radius 1/λ. The crystal is represented by its reciprocal lattice. A reciprocal lattice point intersects the sphere's surface when the Bragg condition is satisfied for the corresponding set of crystal planes, generating a diffracted beam [3].

The Rotation Method and Data Collection

The most common method for collecting X-ray diffraction data from macromolecular crystals is the rotation method [3] [4]. In this approach, the crystal is rotated through a small angular range (e.g., 0.1–1.0°) during a single exposure, bringing successive sets of reciprocal lattice points into diffraction condition as they sweep through the surface of the Ewald sphere [3]. A complete data set is collected by integrating diffraction images over a total rotation range sufficient to measure all unique reflections (see Table 1) [4].

Table 1: Minimal rotation range required for complete data collection for different crystal symmetries, assuming a symmetric crystal orientation. [4]

| Crystal System | Point Group | Minimal Rotation Range |

|---|---|---|

| Triclinic | 1 | 180° |

| Monoclinic | 2 | 90° |

| Orthorhombic | 222 | 90° |

| Tetragonal | 4, 422 | 45°–90° |

| Trigonal | 3, 312, 321 | 60°–120° |

| Hexagonal | 6, 622 | 30°–60° |

| Cubic | 23, 432 | 45°–90° |

The quality of a diffraction data set is judged by its resolution, completeness, and accuracy [4]. Resolution, measured in Ångströms (Å), determines the level of detail visible in the final electron density map; a resolution of 3 Å can reveal the protein chain trace, while 1.5 Å can resolve individual atoms [1] [5]. Completeness refers to the percentage of all possible unique reflections that have been measured within the resolution limit [3] [4]. Accuracy is vital for all subsequent steps, especially for detecting the small intensity differences used in experimental phasing [4].

The Phase Problem and Experimental Solutions

The inability to measure phases directly is the central bottleneck in X-ray structure determination. The relationship between the crystal structure and the diffraction pattern is governed by the Fourier transform. The structure is defined by the electron density ρ(x,y,z), which is calculated by summing the contributions of all scattered waves (reflections):

ρ(x,y,z) = 1/V ΣₕΣₖΣₗ |Fₕₖₗ| exp[-2πi(hx + ky + lz) + iϕₕₖₗ]

Here, |Fₕₖₗ| is the structure factor amplitude (measured from the reflection intensity), and ϕₕₖₗ is the missing phase [1]. The following experimental protocols are primary methods for solving the phase problem.

Protocol: Experimental Phasing via Molecular Replacement (MR)

Principle: Molecular Replacement is the most common phasing method when a structurally similar model is available. It involves orienting and positioning this known model within the unit cell of the unknown crystal, then using its calculated phases as an initial approximation for the new structure [4].

Detailed Methodology:

Preparation of a Search Model:

- Identify a homologous protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with a high sequence identity (>30% is generally favorable).

- Prepare the search model by modifying it to match the target sequence (e.g., pruning side chains, removing flexible loops) using molecular graphics software.

Data Collection and Preparation:

- Collect a native X-ray diffraction data set from the target crystal to a resolution of typically 2.5–3.5 Å, as high resolution is not critical for MR [4].

- Process the data to obtain a unique set of structure factor amplitudes (|Fₒ|). Ensure the data is highly complete, especially in the low-resolution shells (<10 Å), as this is crucial for the success of MR [4].

Rotation and Translation Search:

- Perform a rotation function to determine the correct orientation of the search model within the target unit cell. This is typically a cross-rotation function that maximizes the correlation between the observed diffraction data and the model-predicted data over all possible orientations.

- Using the correct orientation, perform a translation function to find the precise position of the model within the unit cell's asymmetric unit. This involves systematically moving the model and calculating the correlation between observed and calculated structure factors.

Rigid-Body Refinement and Phase Calculation:

- Once correctly placed, subject the model to rigid-body refinement to optimize its position and orientation.

- Calculate initial phases from the refined model and use them to generate an initial electron density map.

Model Building and Refinement:

- The initial map is used to build and refine the atomic model of the target protein, iteratively improving the model to fit the electron density and the measured diffraction data.

Protocol: Experimental Phasing via Anomalous Dispersion

Principle: This method involves introducing heavy atoms (e.g., Se, Hg, Au) into the protein crystal, either via derivatization or by using selenomethionine. These atoms scatter X-rays anomalously—meaning their scattering factor changes—when the X-ray wavelength is tuned near their absorption edge. This creates small measurable differences in diffraction intensities that are used to determine phases [1] [4].

Detailed Methodology:

Preparation of Derivative Crystals:

- Selenomethionine Incorporation: The most common method. Express the protein in a methionine auxotroph bacterial strain in media containing selenomethionine, which is incorporated in place of methionine.

- Soaking: Co-crystallize or soak native crystals in a solution containing a heavy-atom compound (e.g., mercury chloride, platinum derivatives).

Data Collection for Anomalous Phasing:

- Collect X-ray data from a single crystal at a specific wavelength near the absorption edge of the anomalous scatterer (e.g., the selenium K-edge at ~0.979 Å). To maximize the anomalous signal, data must be of the highest possible accuracy [4].

- Collect a highly redundant data set (often >360° of rotation) to improve the measurement of the small anomalous differences.

Location of Anomalous Scatterers:

- Analyze the diffraction data to find the positions of the heavy atoms within the unit cell. This is typically done using Patterson-based methods (e.g., analysis of the anomalous difference Patterson map) or direct methods.

Phase Calculation:

- Refine the heavy-atom parameters (coordinates, occupancy, thermal factors).

- Use these parameters to calculate initial experimental phases (e.g., via Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction, SAD or Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion, MAD).

- Perform phase improvement through density modification (e.g., solvent flattening, histogram matching) to generate an interpretable electron density map.

Model Building:

- Proceed with automated or manual model building into the experimental electron density map.

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Phasing Methods

| Method | Principle | Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Replacement | Uses phases from a known homologous structure | A structurally similar model (>25-30% sequence identity) | Fast, does not require additional experiments | Can fail if no good model exists; model bias is a risk |

| Anomalous Dispersion | Measures signal from incorporated heavy atoms | Tunable X-ray source (synchrotron); derivative crystals | Provides de novo phases; widely applicable with SeMet | Requires preparation of derivative crystals; signal is weak |

Advanced Techniques and Workflow

Emerging Techniques: XFEL and Single-Particle Imaging

X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) enable serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX), where microcrystals are delivered in a stream and probed with ultrashort, extremely intense X-ray pulses. The "diffraction before destruction" principle allows data collection before radiation damage occurs [6]. This has been extended to imaging single particles, such as the GroEL protein complex, opening the door to time-resolved studies of non-crystalline macromolecules on femtosecond timescales [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for protein crystallography experiments.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Crystallization Screens | Pre-formulated sparse matrix solutions (e.g., from Hampton Research) that systematically vary precipitant, buffer, and pH to identify initial crystallization conditions [1]. |

| Selenomethionine | An analog of methionine containing selenium, used for biosynthetic incorporation to provide intrinsic anomalous scatterers for experimental phasing [1]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) added to the mother liquor to prevent ice crystal formation during flash-cooling of crystals in liquid nitrogen [7]. |

| Heavy Atom Compounds | Salts or organometallics (e.g., K₂PtCl₄, HgAc₂) used for soaking crystals to create isomorphous derivatives for experimental phasing [1]. |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | Access to high-brilliance X-ray radiation sources is often essential for challenging experiments, especially for anomalous phasing and low-diffracting crystals [1]. |

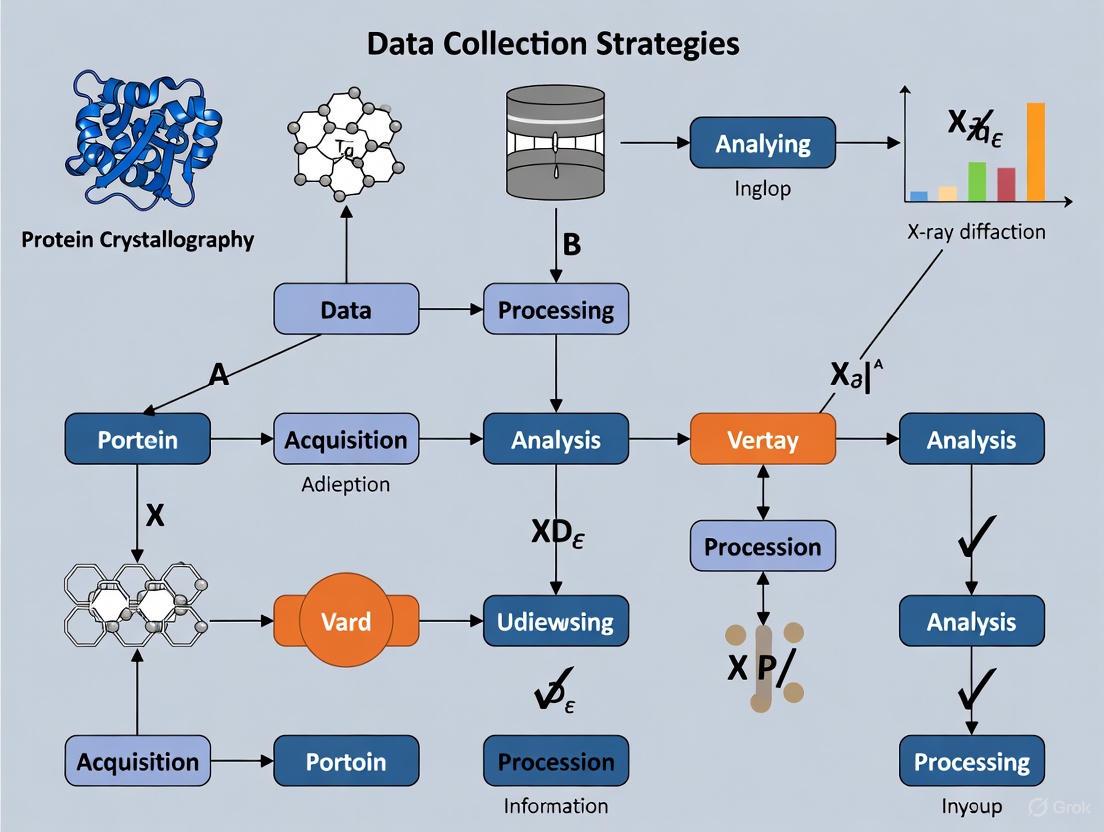

Workflow and Data Flow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a protein crystallography project, from crystal to model, highlighting the central role of the phase problem.

Diagram 1: The protein crystallography workflow, highlighting the phase problem.

A deep understanding of X-ray diffraction principles and the phase problem is fundamental to successful protein structure determination. While the core challenge remains obtaining phase information, robust experimental methods like Molecular Replacement and Anomalous Dispersion provide powerful solutions. The field continues to advance with techniques like XFELs pushing the boundaries towards imaging single molecules and capturing ultrafast dynamics. Careful planning of data collection strategy, with a clear focus on the requirements of the chosen phasing method, is the critical experimental step that underpins all subsequent computational analysis and biological insight.

For decades, the field of structural biology relied heavily on single-crystal X-ray crystallography, a method that required the growth of large, well-ordered protein crystals often exceeding 100 micrometers in size [8]. These macrocrystals were necessary to withstand radiation damage during prolonged exposure to X-ray beams at synchrotron sources and to generate measurable diffraction signals. The requirement for large crystals presented a significant bottleneck, particularly for challenging biological targets such as membrane proteins, large complexes, and radiation-sensitive samples, many of which either could not be grown to sufficient size or would suffer from substantial radiation damage before a complete dataset could be collected [9]. Furthermore, traditional methods typically required cryo-cooling of crystals to mitigate radiation damage, potentially trapping proteins in non-physiological conformational states that do not represent their true functional forms [10]. The advent of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and the development of serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) has fundamentally transformed this paradigm, enabling high-resolution structure determination from microcrystals at room temperature and opening new frontiers in time-resolved structural biology [11] [12].

The Technological Drivers of the Paradigm Shift

The Core Innovation: Diffraction-Before-Destruction

The foundational principle enabling SFX is the "diffraction-before-destruction" concept [8] [12]. XFELs produce X-ray pulses of extraordinary brightness and ultrashort duration, typically on the femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) timescale [9]. These pulses are so intense that they destroy the sample upon interaction, but their brevity allows a usable diffraction pattern to be recorded before the onset of structural disintegration [13]. This phenomenon effectively eliminates the problem of radiation damage that has long plagued conventional crystallography, enabling effectively damage-free data collection at room temperature [12].

Synchrotron Adaptations: SSX and SµX

The success of SFX at XFELs inspired the development of analogous methods at synchrotron facilities, leading to serial synchrotron crystallography (SSX) and its advanced form, serial microsecond crystallography (SµX) [14] [10]. While synchrotrons cannot match the peak brightness of XFELs, modern fourth-generation synchrotrons like the ESRF-EBS can deliver photon flux densities orders of magnitude higher than third-generation sources [10]. The ID29 beamline at the ESRF, for example, utilizes mechanically pulsed beams with microsecond exposure times (down to 90 µs) to collect data from microcrystals, bridging the gap between traditional SMX and XFEL-based SFX [10]. Systematic comparisons have demonstrated that for many systems, the data quality from SFX and SSX is equivalent, indicating that crystal properties rather than the radiation source often dictate the ultimate data quality [14] [15].

The Rise of Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED)

Parallel developments in electron crystallography have further expanded the toolbox for microcrystal analysis. Microcrystal electron diffraction (MicroED) uses a transmission electron microscope to collect data from crystals with depths restricted to 100-300 nm [16]. Electrons interact more strongly with matter than X-rays, allowing higher-resolution structural information to be collected from even smaller crystals [16]. MicroED has proven particularly valuable for membrane proteins and radiation-sensitive samples that are recalcitrant to other methods [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Crystallography Modalities

| Method | X-ray Source | Typical Crystal Size | Exposure Time | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFX | XFEL | 1 µm - 10 µm | Femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) | Outruns radiation damage; enables ultrafast time-resolved studies |

| SµX | 4th Gen Synchrotron | 5 µm - 50 µm | Microseconds (10⁻⁶ s) | High data quality with minimal sample consumption; access to millisecond dynamics |

| SSX/SMX | 3rd Gen Synchrotron | 5 µm - 50 µm | Milliseconds (10⁻³ s) | More accessible than XFEL; suitable for slower dynamics |

| MicroED | TEM | 100 nm - 300 nm | Seconds | Highest resolution from smallest crystals; sensitive to charge states |

Quantitative Comparison: Resolving Power and Data Quality

The transition to serial methods has not compromised data quality. Systematic comparisons between SFX and SSX using identical crystal batches, sample delivery devices, and analysis software have shown that both methods can produce data of equivalent quality [14]. For both the radiation-tolerant enzyme fluoroacetate dehalogenase and the highly radiation-sensitive myoglobin, complete datasets with reasonable statistics were obtained with approximately 5,000 room-temperature diffraction images, regardless of the radiation source [14]. The global data quality parameters, including signal-to-noise ratio, multiplicity, R-split, and completeness, were nearly identical between SFX and SSX data [14]. This equivalence empowers researchers to select the radiation source that best matches their desired time resolution and experimental requirements without sacrificing data quality.

Table 2: Data Collection and Refinement Statistics from a Systematic SFX/SSX Comparison [14]

| Parameter | FAcD-SSX | FAcD-SFX | MB-SSX | MB-SFX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution Range (Å) | 33.08-1.75 | 33.08-1.75 | 31.47-1.75 | 31.47-1.75 |

| Space Group | P21 | P21 | P21₂1₂1 | P21₂1₂1 |

| Refinement R-free | 0.203 | 0.204 | 0.216 | 0.213 |

| Refinement R-work | 0.169 | 0.171 | 0.184 | 0.183 |

Practical Application Notes and Protocols

Lysozyme serves as an excellent standard protein for initial SFX trials to optimize detector geometry and experimental setup.

Materials:

- Sodium acetate trihydrate

- Acetic acid

- Sodium chloride

- PEG 6000, 50% (w/v)

- Lysozyme (egg white)

- pH meter, graduated beakers, 0.22 µm filters, 50 ml centrifuge tubes

- Thermonixer C with SmartBlock

- High-performance microscope (≥1500x magnification)

- CellTrics filter (30 µm)

- Cell counting plate

Procedure:

- Prepare Buffer A (1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 3.0): Add approximately 2.5 ml of 1 M sodium acetate to 100 ml of 1 M acetic acid and adjust to pH 3.0 using a calibrated pH meter.

- Prepare Crystallization Solution: To a graduated beaker, add 10 ml of Buffer A, 28 g of sodium chloride, and 16 ml of 50% (w/v) PEG 6000. Add ultrapure water to bring the final volume to 100 ml. Mix for several hours to overnight until all components are fully dissolved. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter. Store at room temperature for no more than one week.

- Prepare Lysozyme Solution: Dissolve lysozyme in ultrapure water to a final concentration of 100 mg/ml.

- Crystallization: Mix equal volumes (typically 50-100 µl each) of the lysozyme solution and crystallization solution in a 1.5 ml tube. Incubate the mixture at 17°C for microcrystal formation. Crystal size can be controlled by varying temperature, with lower temperatures favoring smaller crystals.

- Harvesting and Characterization: Harvest crystals by centrifugation and resuspend in an appropriate harvest solution. Determine crystal density using a cell counting plate under a microscope. Filter crystals through a 30 µm CellTrics filter if necessary to obtain a homogeneous size distribution.

Time-resolved SFX (TR-SFX) enables visualization of protein dynamics at near-atomic resolution under ambient temperature conditions.

Materials:

- Microcrystals of target protein (e.g., fungal nitric oxide reductase, P450nor)

- Photo-caged substrate compounds

- UV laser system for photo-triggering

- Liquid injection system compatible with XFEL facility

- Data collection setup at XFEL beamline

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Co-incubate protein microcrystals with photo-caged substrate molecules. The caging group renders the substrate inert until UV irradiation.

- Experimental Setup: Load the crystal suspension into an appropriate injection system (typically a liquid jet for high repetition rate experiments). Synchronize the timing between the UV laser (pump) and XFEL pulses (probe) with precise delay stages.

- Data Collection: As crystals flow across the XFEL beam, trigger the reaction using a synchronized UV laser pulse to cleave the caging group and release the active substrate. Collect diffraction patterns at various time delays following photo-excitation to capture structural intermediates.

- Data Processing: Process the serial diffraction data using specialized software suites like CrystFEL. Merge data from thousands of crystal patterns to reconstruct complete reciprocal space and calculate electron density maps for each time point.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for SFX Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Liquid injection of crystal suspensions in vacuum; standard at high repetition rate XFELs | 3D-printed nozzles for high reproducibility [12] |

| Fixed Target Chips | Silicon-based supports for crystal deposition; reduces sample consumption | Compatible with various beamline setups [8] |

| High-Viscosity Extruders (HVE) | Delivery of crystal-laden viscous media; minimizes background scattering | Grease or lipidic cubic phase matrices [10] |

| Photo-caged Compounds | Triggering reactions for time-resolved studies with UV laser | Enables studies of non-light-responsive proteins [11] |

| JUNGFRAU Detector | Advanced X-ray detector for serial crystallography | Charge-integrating detector with 4M pixels used at ID29 [10] |

Workflow and Data Collection Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for a serial femtosecond crystallography experiment, highlighting the key steps from sample preparation to structure solution:

Implications for Drug Discovery and Future Outlook

The paradigm shift from macrocrystals to SFX has profound implications for structure-based drug discovery (SBDD), particularly for challenging target classes. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which represent targets for approximately 40% of marketed drugs, have been historically difficult to study using traditional crystallography [9]. SFX enables structure determination of these targets from microcrystals at room temperature, potentially revealing conformational states that are more physiologically relevant than those trapped by cryo-cooling [10]. The application of time-resolved methods further allows researchers to visualize drug-target interactions and enzymatic reactions in real-time, creating "molecular movies" that can inform the drug optimization process [11] [12].

Future developments in SFX will focus on increasing accessibility and throughput while further reducing sample requirements. The ideal sample consumption for a complete SFX dataset is estimated to be as low as 450 nanograms of protein, calculated based on 10,000 indexed patterns from 4×4×4 µm crystals with a protein concentration of ~700 mg/mL [8]. Ongoing advancements in high-repetition-rate XFELs (e.g., European XFEL, LCLS-II) will dramatically accelerate data collection, while innovations in sample delivery methods such as double-flow focusing nozzles (DFFN) and fixed-target systems aim to minimize sample waste [12]. The integration of artificial intelligence for data analysis and the continued development of synchrotron-based serial methods will make these powerful techniques available to a broader community of researchers, ultimately accelerating our understanding of biological function and therapeutic development [17].

Serial crystallography (SX) has revolutionized structural biology by enabling high-resolution structure determination from microcrystals at room temperature, providing insights into biomolecular reaction mechanisms and dynamics that were previously inaccessible. The core challenge driving this evolution is the sample consumption of precious macromolecular samples, whose availability is often limited [8]. Two primary X-ray sources have enabled these advances: Synchrotrons for Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) and X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) for Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX). This application note provides a structured comparison of these technologies, framed within data collection strategies for protein crystallography research, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate source for their experimental needs.

Source Fundamentals and Experimental Modes

Synchrotrons (SMX)

Synchrotron facilities generate intense, continuous X-rays by accelerating electrons through storage rings. Third and fourth-generation synchrotrons, like the Swiss Light Source, feature micro-focused beams (below 10 µm in diameter) and enable Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) [8] [18]. In SMX, data collection occurs on the millisecond timescale, requiring crystals to be rapidly scanned or delivered across the beam. These facilities often support high-throughput in situ screening within 96-well crystallization plates, allowing for efficient sample characterization with minimal consumption (e.g., <200 nL per drop) [19].

X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs)

XFELs produce ultra-bright, femtosecond-duration X-ray pulses through linear acceleration of electrons in undulator fields. These pulses are about 10 billion times brighter in peak brilliance than third-generation synchrotrons [20]. This enables the "diffraction-before-destruction" technique, where a diffraction pattern is recorded from a single crystal in femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) before the onset of radiation damage [8] [20]. This method, known as Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX), liberates experiments from the requirement of large, single crystals and enables time-resolved studies at near-physiological temperatures on femtosecond to millisecond timescales [8] [21].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of X-ray Sources

| Characteristic | Synchrotron (SMX) | X-ray Free-Electron Laser (XFEL) |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Pulse Duration | Millisecond to second | Femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) |

| Peak Brilliance | High (3rd generation sources) | ~10 billion × higher than synchrotrons |

| Primary Operating Mode | Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) | Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) |

| Radiation Damage Mitigation | Rapid crystal scanning, low doses | "Diffraction-before-destruction" |

| Typical Crystal Size | Microcrystals (compatible with beam size) | Nano- to micro-crystals |

| Sample Temperature | Room temperature or cryogenic | Typically room temperature |

Comparative Analysis: SMX vs. SFX Performance

The choice between SMX and SFX involves critical trade-offs between sample consumption, temporal resolution, access, and data processing requirements. Sample consumption has been a historical challenge for SX, particularly at XFELs where early experiments required grams of protein [8]. However, advances in sample delivery have reduced this to microgram amounts [8]. The theoretical minimum sample consumption for a complete SX dataset (requiring ~10,000 indexed patterns) is estimated at ~450 ng of protein, assuming 4 µm cubic crystals and a protein concentration of ~700 mg/mL [8].

Temporal resolution differs significantly: SMX is suitable for slower processes, while SFX enables ultra-fast, time-resolved studies (TR-SFX) on femtosecond timescales, enabling the creation of "molecular movies" of reaction mechanisms [8] [20]. Accessibility also varies; synchrotron beamtime is generally more accessible than the limited availability of XFEL facilities [8].

Table 2: Practical Experimental Comparison

| Experimental Factor | Synchrotron (SMX) | XFEL (SFX) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Consumption (Modern Methods) | Micrograms [8] | Micrograms to grams (application-dependent) [8] |

| Ideal Sample Consumption (Theoretical Minimum) | ~450 ng for a full dataset [8] | ~450 ng for a full dataset [8] |

| Time-Resolved Studies | Millisecond to second timescales | Femtosecond to millisecond timescales [8] [20] |

| Data Collection Rate | High-throughput at specialized beamlines [19] [18] | Ultra-high-speed (e.g., MHz repetition rates at EuXFEL) [22] |

| Accessibility | More readily available | Limited experimental time |

| Primary Applications | High-throughput screening, static structure determination, slower dynamics | Membrane proteins, radiation-sensitive samples, ultra-fast dynamics [20] [21] |

Decision Framework for Source Selection

The following decision diagram outlines the key considerations for choosing between SMX and SFX based on experimental goals and sample properties:

Diagram 1: Source Selection Decision Framework. This flowchart guides researchers in selecting between SMX and SFX based on their experimental goals, sample properties, and practical constraints.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SMX Data Collection from Batch-Grown Microcrystals

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 study, describes a highly sample-efficient method for collecting SMX data directly from batch-grown microcrystals dispensed into 96-well plates [19].

5.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SMX in 96-Well Plates

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| In Situ 96-Well Crystallization Plate | Sample holder compatible with X-ray transmission | MiTeGen In Situ-1 plates [19] |

| Liquid Dispenser | Precise transfer of crystal suspension | Mosquito liquid dispenser [19] |

| Batch-Grown Microcrystals | Analyte for structure determination | Homogeneous, well-diffracting crystals |

| Storage Solution | Crystal stabilization during data collection | Condition-specific (e.g., 10% NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 4.0 for lysozyme) [22] |

| Synchrotron Beamline | X-ray source with microfocus and high flux | VMXi beamline at Diamond Light Source or equivalent [19] |

5.1.2 Step-by-Step Workflow

The experimental workflow for SMX data collection in 96-well plates involves sample preparation, mounting, raster scanning, and data processing as detailed below:

Diagram 2: SMX Experimental Workflow. Step-by-step procedure for efficient SMX data collection from batch-grown microcrystals in 96-well plates.

- Sample Preparation: Grow microcrystals using batch crystallization methods. Concentrate if necessary. Use a liquid dispenser (e.g., Mosquito) to transfer 100-200 nL aliquots of crystal suspension into 96-well crystallization plates (e.g., MiTeGen In Situ-1). Perform multiple aspiration steps before dispensing to ensure homogeneous crystal distribution [19].

- Plate Mounting: Load the prepared crystallization plate into the beamline sample holder (e.g., at the VMXi beamline at Diamond Light Source). Maintain temperature at 20°C throughout data collection [19].

- Raster Scanning: Define scan areas covering the crystallization drops. Perform 2D raster scanning with a 10 µm step size using a micro-focused beam (e.g., 10 × 10 µm) at high X-ray energy (e.g., 16.0 keV) to maximize resolution and reduce radiation damage [19].

- Data Collection: At each raster point, collect a still diffraction image with a short exposure time (e.g., 2 ms per image). Use a high-frame-rate detector (e.g., Dectris EIGER 2X 4M) positioned at an appropriate distance (e.g., 175 mm) [19].

- Data Processing: Process all still diffraction images using an automated serial crystallography pipeline (e.g., xia2.ssx with DIALS). The software handles multiple lattices and repeated exposures to the same crystal automatically [19].

- Structure Analysis: Use the processed data to determine crystal quality, unit-cell distribution, identify any polymorphism, and solve the final structure. This information can guide further optimization of crystallization conditions for scaling up [19].

Protocol 2: SFX Data Collection at XFELs

This protocol outlines the key steps for conducting an SFX experiment at an XFEL facility, such as the SPB/SFX instrument at the European XFEL, using a liquid jet for sample delivery [22].

5.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for SFX at XFELs

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Microcrystal Suspension | Analyte for structure determination | Homogeneous microcrystals (e.g., ~2 µm lysozyme) [22] |

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Liquid jet-based sample delivery | 3D printed nozzle with specific orifice diameters [22] |

| High-Speed Detector | Records diffraction patterns from single pulses | Adaptive Gain Integrating Pixel Detector (AGIPD) [22] |

| Filter Assembly | Removes crystal aggregates and large particles | Stainless steel frits (e.g., 20 µm and 10 µm pore sizes) [22] |

| High-Repetition Rate XFEL | X-ray source for femtosecond pulses | European XFEL, LCLS, or similar [22] |

5.2.2 Step-by-Step Workflow

- Sample Preparation: Grow homogeneous microcrystals (e.g., approximately 2 × 2 × 2 µm for lysozyme). Transfer crystals to an appropriate storage solution (e.g., 10% NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer pH 4.0). Prepare a concentrated suspension (e.g., 25% v/v) and filter sequentially through stainless steel frits (e.g., 20 µm and 10 µm pore sizes) to remove aggregates and ensure smooth jet operation [22].

- Sample Delivery: Connect the filtered crystal suspension to a Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN). Use focusing gas (e.g., helium) to create a stable liquid jet containing microcrystals. Adjust liquid and gas pressures to achieve the desired jet velocity and diameter. The jet must continuously present new crystals to the X-ray beam at a rate matching or exceeding the XFEL pulse repetition rate [22].

- Beam Alignment: Align the liquid jet precisely to the X-ray interaction point. Use an off-axis microscope to visualize the jet and ensure stable operation. The X-ray beam is typically focused to a small spot (e.g., 3.2 µm × 6.2 µm FWHM) at the interaction point [22].

- Data Collection: Set the detector (e.g., AGIPD) to record diffraction patterns from individual XFEL pulses. For facilities like the European XFEL, configure data acquisition to account for the unique pulse train structure (e.g., 300 pulses per train at 1.1 MHz). Monitor jet stability and data quality throughout the experiment [22].

- Detector Calibration and Data Processing: Apply calibration constants to convert raw detector signals into photon counts. Use specialized software (e.g., CrystFEL) for peak finding, indexing, and merging diffraction patterns from thousands to millions of crystals. Implement Monte Carlo integration to account for partial reflections in still patterns [22].

SMX and SFX are complementary techniques within the serial crystallography toolkit. SMX at synchrotrons offers an excellent balance of accessibility, high-throughput capability, and efficiency for static structure determination and slower time-resolved studies. SFX at XFELs provides unique capabilities for ultra-fast time-resolved experiments, studying highly radiation-sensitive systems, and achieving effectively damage-free data collection at room temperature. The choice between them should be guided by specific experimental needs—particularly the required temporal resolution, sample characteristics, and beamtime availability. As both technologies continue to advance, with ongoing developments in sample delivery, beamline instrumentation, and data processing, serial crystallography will undoubtedly expand to enable the study of an ever-broader range of biologically significant samples.

In protein crystallography, the efficient use of precious macromolecular samples is a pivotal concern that directly impacts the scope and success of structural biology research. Serial crystallography (SX), which involves collecting partial datasets from numerous microcrystals, has revolutionized the field by enabling high-resolution structure determination for challenging proteins, including membrane proteins and those involved in transient biological reaction mechanisms [8]. However, a significant challenge remains: the high consumption of sample, often requiring milligrams of purified protein, which can be prohibitive for biologically relevant but difficult-to-crystallize proteins [8]. This application note examines the critical importance of efficient data collection strategies within protein crystallography, framing them within the broader context of a research thesis on data collection. It provides a comparative quantitative analysis of sample delivery methods and detailed protocols designed to minimize sample consumption while maximizing the quality of structural information obtained.

The Critical Role of Data Collection Efficiency

Efficient data collection is the cornerstone of modern protein crystallography, directly determining the feasibility of studying a wide array of biological samples. The advent of brilliant X-ray sources, such as synchrotrons and X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), has introduced a "diffraction before destruction" paradigm, necessitating the continuous replenishment of crystals for a complete dataset [8]. This serial approach consumes substantial quantities of protein, a concern magnified in time-resolved serial crystallography (TR-SX), where sample consumption is multiplied for each time point probed [8].

The theoretical minimum sample requirement for a complete SX dataset provides a benchmark for efficiency. Assuming a dataset comprising 10,000 indexed patterns from microcrystals of 4 × 4 × 4 µm in size and a protein concentration in the crystal of approximately 700 mg/mL, the ideal protein mass required is about 450 ng [8]. Early SX experiments, in contrast, consumed grams of protein, highlighting a vast gap between historical practice and theoretical efficiency [8]. Bridging this gap through optimized sample delivery and data collection protocols is essential for expanding the frontiers of structural biology.

Quantitative Analysis of Sample Delivery Methods

Sample delivery methods are primarily categorized by their mechanism of presenting crystals to the X-ray beam. The choice of method profoundly influences sample consumption, data quality, and applicability to different experimental setups, such as static or time-resolved studies. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary sample delivery systems.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sample Delivery Methods in Serial Crystallography

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Sample Consumption | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection | A liquid stream or jet of crystal slurry is continuously injected into the X-ray beam [8]. | High (Early experiments used >10 µL/min for hours/days [8]) | Compatible with mix-and-inject (MISC) time-resolved studies; suitable for a wide range of crystal sizes [8]. | High waste of sample that flows between X-ray pulses; requires high crystal density; can be challenging with viscous media [8]. |

| Fixed-Target | Crystals are deposited and immobilized on a solid support (e.g., a silicon chip with microwells), which is raster-scanned through the beam [23]. | Low (Economical use by maximizing data per crystal [23]) | Minimal sample waste; allows for pre-characterization and precise positioning of crystals; ideal for room-temperature data collection [23]. | May require specialized chips and stages; potential for high background scatter from the support material [8]. |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion | Crystal slurry is mixed with a viscous matrix (e.g., grease or lipidic cubic phase) and extruded as a slow-moving stream [8]. | Medium | Significantly reduces flow rate and sample consumption compared to liquid jets; ideal for membrane proteins often crystallized in lipidic cubic phase [8]. | Can be technically challenging to handle and maintain a stable stream; may require optimization of matrix composition [8]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate sample delivery method based on key experimental parameters, including the primary goal, crystal availability, and the need for time-resolution.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Low-Consumption Data Collection

Protocol: Fixed-Target Serial Crystallography on a Silicon Chip

This protocol outlines the procedure for efficient, low-consumption data collection using a fixed-target silicon chip approach, which is ideal for microcrystals and room-temperature studies [23].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Fixed-Target SX

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Silicon Chip | A micro-fabricated chip containing thousands of microwells to hold and locate individual crystals [23]. |

| Piezoelectric Translation Stage | Provides fast and highly precise positioning of each crystal-containing microwell into the X-ray beam [23]. |

| Compound Refractive Lens (CRL) | A series of beryllium lenses that focus the X-ray beam to an intense microbeam (e.g., <20 µm diameter) suitable for microcrystals [23]. |

| Fast-readout Detector (e.g., EIGER) | Enables rapid data collection at hundreds of frames per second to minimize radiation damage [23]. |

| Crystal Suspension Buffer | A compatible buffer to prepare a slurry of microcrystals for loading onto the chip. |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Gently homogenize the crystal harvest to create a slurry of microcrystals. Ensure the crystal size is appropriate for the microwells on the silicon chip.

- Chip Loading: Apply a small volume (e.g., 0.5-2 µL) of the crystal slurry onto the surface of the silicon chip. Use a wicking step or gentle centrifugation to settle crystals into the microwells and remove excess mother liquor.

- Mounting and Cryo-Cooling (Optional): If data collection is to be performed at cryogenic temperatures, transfer the loaded chip to a goniometer and cryo-cool it with a stream of nitrogen gas. For room-temperature data collection, the chip can be mounted in a humidified chamber to prevent dehydration.

- Data Collection Strategy:

- Raster Scanning: Use the piezoelectric stage to rapidly and systematically move the chip so that each crystal-containing microwell is positioned in the X-ray beam path.

- Oscillation: For each crystal, collect a small oscillation range (e.g., 1-10°). This "serial oscillation crystallography" improves the amount of useful data obtained from each crystal, reducing the total number of crystals required for a complete dataset [23].

- Beamline Integration: This method is effectively deployed at beamlines like FlexX at MacCHESS, which are tailored for fixed-target SX, integrating a micro-focused beam, fast detector, and precise stages [23].

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Protocol: Optimized Data Collection Strategy for Anomalous Phasing

For experiments relying on anomalous diffraction signals (e.g., SAD/MAD), the accuracy of intensity measurement is paramount. This protocol details a strategy to collect high-quality data for experimental phasing while managing radiation damage [24] [25].

Procedure:

- Wavelength Selection: Use a fluorescence scan (e.g., with CHOOCH) at the absorption edge of the relevant anomalous scatterer (e.g., Se, Zn, or native S) to determine the optimal wavelength for maximizing the anomalous signal [25].

- Crystal Screening: Collect a few test images from several crystals. Use automated software to index and integrate these initial images to prioritize the best-diffracting crystal for the full data collection [24].

- Multi-Pass Data Collection: To avoid the saturation of strong, low-resolution reflections and secure accurate measurements of the weak anomalous signal:

- Pass 1 (Low Resolution): Collect a low-resolution pass (e.g., 3.5-4.0 Å) with a lower X-ray dose to accurately measure the strong low-resolution reflections, which are critical for phasing [24].

- Pass 2 (High Resolution): Collect a high-resolution pass with a higher dose to record the weak, high-resolution reflections. Limit the total rotation range to the minimum required for completeness to mitigate radiation damage [24] [25].

- Fine φ-Slicing: Set the rotation range per image (Δφ) to be smaller than the crystal mosaicity to ensure complete sampling of reflections, which is crucial for accurate intensity estimation in single-photon-counting pixel detectors [25].

- On-the-Fly Processing: Process data in near real-time during collection to monitor key statistics like signal-to-noise, completeness, and the presence of a significant anomalous signal, allowing for strategy adjustments if needed [25].

The challenge of sample consumption in protein crystallography is a significant but surmountable barrier. As detailed in this note, the strategic selection and implementation of efficient data collection methods—particularly fixed-target and high-viscosity extrusion approaches—can reduce sample requirements from gram to microgram quantities, closely approaching the theoretical minimum [8] [23]. These protocols, when integrated into a coherent data collection strategy, empower researchers to pursue structural studies on a broader range of biologically significant targets, including those that are rare, difficult to crystallize, or subject to time-resolved investigation. The continued evolution of these methods, coupled with automation and microfocus beamlines, promises to further democratize access to high-resolution structural biology.

Modern Methodologies: Sample Delivery, Time-Resolved Studies, and Data Processing Pipelines

Serial crystallography (SX) has revolutionized structural biology by enabling high-resolution structure determination from microcrystals at room temperature, overcoming the radiation damage limitations of traditional crystallography [8]. This technique, employed at both synchrotrons and X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), relies on the efficient delivery of thousands to millions of microcrystals into the X-ray beam [26]. The choice of sample delivery method is paramount, as it directly impacts data quality, sample consumption efficiency, and feasibility for time-resolved studies [8] [27]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of the three primary sample delivery systems—fixed-target, liquid injection, and hybrid methods—within the context of developing robust data collection strategies for protein crystallography research. We summarize quantitative performance data, outline step-by-step protocols, and provide essential guidance for researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the optimal delivery system for their experimental goals.

Comparative Analysis of Sample Delivery Methods

The efficient delivery of microcrystals is a critical component of any serial crystallography experiment. The principal methods have distinct operational paradigms, advantages, and limitations, which are quantitatively summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Sample Delivery Methods for Serial Crystallography

| Method | Typical Sample Consumption (per dataset) | Best Suited For | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Target [8] [28] | < 1 mg | Low repetition-rate sources (e.g., synchrotrons), time-resolved studies, minimal sample waste. | Minimal sample waste; precise control over timing for time-resolved studies; compatible with multi-shot data collection. | Potential for crystal settling during loading; risk of crystal damage from shear forces during loading. |

| Liquid Injection | ||||

| • Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) [8] [29] | ~10 mg | High repetition-rate XFELs (>1 MHz). | Stable stream in vacuum; maintains native crystal environment. | High sample waste at low repetition-rate sources; high flow rates (~10-30 µL/min). |

| • High-Viscosity Extrusion [29] [27] | ~1 mg | Low repetition-rate sources, membrane proteins crystallized in LCP. | Very low flow rates (nL/min to µL/min); reduced sample waste. | Potential chemical/physical reactions between crystals and viscous medium. |

| Hybrid Methods [27] | Varies | Experiments requiring low waste and high temporal control. | Combines advantages of low waste and precise delivery. | Higher system complexity; requires specialized equipment. |

The theoretical minimum sample requirement for a complete SX dataset is remarkably low, estimated to be approximately 450 ng of protein, assuming ideal conditions including 10,000 indexed patterns, microcrystals of 4 µm³, and a protein concentration of ~700 mg/mL in the crystal [8]. While current methods have not yet universally achieved this ideal, it serves as a benchmark for development and highlights the potential for further efficiency gains.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fixed-Target Sample Loading and Data Collection

Fixed-target methods involve loading a crystal slurry onto a solid support, which is then rastered through the X-ray beam [28]. This protocol minimizes sample waste, as every loaded crystal can potentially be interrogated.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Crystal Slurry: Microcrystals in their mother liquor.

- Carrier Matrix: A viscous agent like LCP or a hydrophilic polymer (e.g., hydroxyethyl cellulose) may be used to suspend crystals and prevent settling.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Concentrate the microcrystal slurry to approximately 5–10 × 10⁵ crystals mL⁻¹ [26]. For some targets, mixing with a compatible viscous medium is necessary to prevent sedimentation and facilitate even loading.

- Target Loading: Pipette 100–150 µL of the crystal slurry onto the surface of the fixed-target device [26]. Use a gentle sweeping motion with a pipette tip or a specialized wiper to spread the slurry evenly across the surface, ensuring a monolayer of crystals.

- Mounting and Environment Control: Securely mount the loaded target into the sample chamber. For room-temperature data collection, maintain a humidified environment (e.g., >90% relative humidity) to prevent sample dehydration throughout the experiment.

- Data Collection: Raster the target through the X-ray beam using a high-precision translation stage. The X-ray beam is fired when a crystal is predicted to be in the interaction point, based on the target's known geometry and position.

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

Protocol 2: Viscous Sample Delivery via Syringe Injector

This protocol details the use of a Microliter Volume (MLV) syringe injector for delivering crystals embedded in a viscous medium, a method favored for its low sample consumption and operational simplicity at facilities like the PAL-XFEL [27].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Viscous Delivery Medium: Lipid cubic phase (LCP) for membrane proteins or other hydrophobic/hydrophilic polymers (e.g., agarose) for soluble proteins.

- Crystal Slurry: Concentrated microcrystals.

Procedure:

- Sample Mixing:

- In a dual-syringe setup connected by a syringe coupler, combine equal volumes of the crystal slurry and the chosen viscous medium.

- Cycle the mixture between the two syringes vigorously for 2–5 minutes until a homogeneous, opalescent mixture is achieved.

- Injector Assembly:

- Transfer the final homogeneous mixture into one syringe of the MLV syringe injector.

- Assemble the injector and connect it to a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) pump that will provide precise pressure control.

- Stream Alignment:

- Install the injector into the experimental chamber (e.g., the MICOSS system at PAL-XFEL).

- Use the chamber's in-line cameras to align the extruded viscous stream with the path of the X-ray beam.

- Data Collection:

- Initiate the HPLC pump to extrude the sample at a typical flow rate of 100 nL/min to 1 µL/min [27].

- Trigger the X-ray pulses to coincide with the arrival of new sample in the interaction point.

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate materials is critical for successful sample delivery. The table below lists key reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sample Delivery in Serial Crystallography

| Item | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) [29] [27] | A highly viscous membrane-like matrix used for growing and delivering membrane protein crystals. | Excellent for low-flow-rate injection; requires high-pressure extruders. |

| Hydrophilic Polymers [27] | Polymers (e.g., agarose, hydroxyethyl cellulose) that increase the viscosity of aqueous crystal slurries. | Prevents crystal settling; reduces sample consumption in injectors. |

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) [29] [30] | A concentric nozzle using co-flowing gas to focus a liquid stream to a diameter smaller than the orifice. | Creates a stable jet in vacuum; standard for liquid injection at XFELs. |

| MLV Syringe Injector [27] | A microliter-volume syringe system that acts as both a sample reservoir and an injector. | Simplifies sample preparation; directly uses sample mixed in a syringe. |

| High-Pressure HPLC Pump [27] [30] | Provides precise pressure to drive sample flow, especially for viscous media. | Essential for operating LCP and high-viscosity injectors. |

The landscape of sample delivery in serial crystallography offers a suite of specialized tools, each with its own strengths. Fixed-target methods provide the highest efficiency for precious samples and unparalleled control for time-resolved studies. Liquid injection methods, particularly when coupled with high-viscosity media, offer a robust and widely adopted solution that maintains the crystal's native environment. Hybrid methods continue to emerge, aiming to combine the best features of both approaches. The choice of system is not one-size-fits-all; it must be strategically aligned with the specific protein target, the available sample quantity, the X-ray source characteristics, and the overarching scientific question. As these technologies continue to mature, the driving goals of reducing sample consumption, improving ease of use, and expanding experimental capabilities, such as in time-resolved structural biology, will remain paramount for researchers and drug developers alike.

The implementation of serial crystallography (SX) at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and synchrotrons has revolutionized structural biology by enabling the study of microcrystals and time-resolved mechanisms. However, the substantial sample consumption required for these experiments has presented a significant bottleneck, particularly for precious macromolecular samples where availability is often limited. This application note details the current strategies and technological innovations that dramatically reduce protein consumption in crystallography experiments. We provide a comprehensive comparison of sample delivery methods, a detailed protocol for low-volume fixed-target loading using acoustic dispensing, and a framework for selecting optimal data collection strategies based on sample characteristics. These methodologies are essential for expanding the application of SX to a broader range of biologically significant targets, including membrane proteins and protein complexes relevant to drug development.

Serial crystallography (SX) emerged from the development of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), which utilize the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle to obtain high-resolution structures from microcrystals [8]. This technique has since been adapted to synchrotron sources as serial millisecond crystallography (SMX). A fundamental challenge inherent to SX is the massive consumption of crystal sample, as each crystal is typically exposed to a single X-ray pulse before being destroyed, requiring continuous replenishment of the crystal stream to collect a complete dataset comprising tens of thousands of diffraction patterns [8].

The theoretical minimum sample requirement for a complete SX dataset can be calculated based on the number of indexed patterns needed (typically ~10,000), the crystal volume, and the protein concentration within the crystal. For a 4 µm³ crystal with a protein concentration of ~700 mg/mL, this ideal minimum is approximately 450 ng of protein [8]. However, early SX experiments often required grams of protein, as much of the injected sample was wasted between X-ray pulses [8]. This high consumption has been a major barrier to studying biologically and medically relevant proteins, which are often difficult to produce in large quantities. The following sections outline strategies and technologies that bridge this gap, bringing practical SX within reach for a wider scientific community.

Comparative Analysis of Sample Delivery Methods

Sample delivery is a primary factor determining efficiency in serial crystallography. The three main systems are liquid injection, fixed-target methods, and drop-on-demand techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations concerning sample consumption, ease of use, and applicability to time-resolved studies [8] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Sample Delivery Methods for Serial Crystallography

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Sample Consumption | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection | Continuous jet of crystal slurry across X-ray beam [8]. | High (µL to mL/min) [8] | Fast data collection; suitable for time-resolved studies [31]. | High sample waste; jet clogging; requires high crystal density [31]. |

| Fixed-Target | Crystals are loaded onto a solid chip and rastered through the beam [8] [32]. | Low (nL to µL) [32] | Minimal sample waste; compatible with standard synchrotron equipment; no jet clogging [32]. | Potential background scattering from chip; risk of crystal dehydration [8]. |

| Drop-on-Demand | Piezo-electric or acoustic ejection of crystal-containing droplets on demand [31]. | Medium to Low | Reduced waste compared to continuous jets; precise control over droplet placement [31]. | Technical complexity; potential for nozzle clogging [31]. |

Among these, fixed-target approaches have demonstrated remarkable efficiency. For instance, loading fixed targets using traditional pipetting requires ~100–200 µL of crystal slurry, whereas acoustic drop ejection (ADE) can reduce this volume to less than 4 µL for a single chip, representing an improvement of more than an order of magnitude [32].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Fixed-Target Loading Techniques

| Loading Parameter | Pipette Loading | Acoustic Drop Ejection (ADE) |

|---|---|---|

| Slurry Volume Required | ~100–200 µL [32] | < 4 µL [32] |

| Loading Time (for 14,400 apertures) | Not Specified | ~2 minutes 15 seconds [32] |

| Typical Droplet Volume | Not Applicable | 80–100 picoliters (pL) [32] |

| Hit Rate (Indexed Patterns/Image) | 81% (HEWL), 66% (AcNiR) [32] | 77% (HEWL), 85% (AcNiR) [32] |

Detailed Protocol: Acoustic Loading of Fixed Targets

This protocol describes the use of acoustic dispensing to efficiently load fixed targets for serial crystallography, minimizing sample consumption while maintaining high data quality [32].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Acoustic Fixed-Target Loading

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| PolyPico Dispenser or equivalent | Acoustic dispenser that uses high-frequency waves to eject picoliter-volume droplets from a cartridge [32]. |

| Silicon Nitride "Chip" Fixed Target | Chip containing thousands of micro-apertures (e.g., funnel-shaped, ~7 µm diameter) to hold individual crystals [32]. |

| Dispensing Cartridges | Disposable cartridges with an aperture (30-150 µm diameter) that holds the crystal slurry [32]. |

| High-Precision XYZ Stages | Precisely positions the fixed target chip relative to the dispensing head [32]. |

| High-Resolution Camera & Stroboscopic LED | Visualizes ejected droplets for volume calibration and ensures accurate alignment during chip loading [32]. |

| Humidity Chamber (>90% RH) | Encloses the chip and dispensing head to prevent sample dehydration during the loading process [32]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: System Setup and Calibration

- Mount the acoustic dispensing head on a kinematic mount.

- Load 10–20 µL of crystal slurry into a dispensing cartridge using a pipette with a tip-like adapter. Note that unused slurry can be recovered after the experiment.

- Select a cartridge aperture diameter approximately twice the typical crystal size to ensure stable ejection and avoid clogging.

- Initiate the calibration routine. Use the camera and stroboscopic LED to visualize ejected droplets. Adjust the width, amplitude, and frequency of the acoustic wave until stable droplet ejection is achieved. Image recognition software provides real-time feedback on the average droplet volume, which is typically 80–100 pL when using a 1 kHz acoustic wave and a 100 µm cartridge aperture [32].

Step 2: Chip Alignment and Loading

- Mount a clean, dry fixed-target chip onto the high-precision XYZ stage.

- Enclose the chip and dispensing head within the high-humidity chamber (>90% relative humidity) to prevent dehydration.

- Align the chip fiducials using the high-resolution camera. The tip of the dispensing head should be within 0.5 mm of the chip surface.

- Initiate the automated loading sequence. The stage moves the chip so that each aperture is positioned under the dispenser. A TTL pulse from the stage triggers the dispensing head to eject a user-defined number of droplets (optimally two droplets per aperture) at each position at a frequency of 1 kHz.

- A chip with 14,400 positions can be loaded in approximately 2 minutes and 15 seconds, consuming less than 4 µL of total slurry volume [32].

Step 3: Sealing and Data Collection

- After loading, immediately seal the chip with a thin film (e.g., 6 µm Mylar) to maintain hydration.

- Transfer the sealed chip to the synchrotron or XFEL beamline for data collection. The chip is rastered through the X-ray beam to collect a diffraction pattern from each crystal-loaded aperture.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for implementing a low-sample-consumption strategy, from initial sample preparation to data collection.

Foundational Strategies for Sample Preparation and Optimization

The success of any low-consumption serial crystallography experiment is fundamentally dependent on the quality and properties of the crystal sample itself. Prior to data collection, meticulous optimization of the biochemical and physical sample parameters is crucial.

- Achieve High Sample Purity and Homogeneity: A purity of >95% is typically required for successful crystallization, as impurities or heterogeneous populations can disrupt ordered crystal lattice formation [33] [34]. Employ multi-step chromatography and carefully designed affinity tags. Monitor monodispersity and prevent aggregation using techniques like dynamic light scattering (DLS) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) [33] [34].

- Enhance Conformational Stability: Proteins with flexible regions often fail to form stable crystals. Implement strategies like surface entropy reduction (SER), where high-entropy residues (e.g., Lys, Glu) are replaced with Ala or Thr to promote crystal contacts [34]. For challenging proteins, especially membrane proteins, use fusion protein strategies or introduce stabilizing ligands to lock the protein into a single conformation [33] [34].

- Optimize Crystallization Conditions: Utilize high-throughput sparse-matrix screening to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space of crystallization cocktails [33]. For samples that only form microcrystals, employ Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS), which uses pre-formed microcrystals as nucleation templates to expand the range of conditions yielding usable crystals [34].

The field of serial crystallography is rapidly evolving, with sample delivery methods now enabling structural determination from microgram, rather than milligram, quantities of protein. Fixed-target methods, particularly when coupled with advanced loading technologies like acoustic dispensing, stand out for their dramatic reduction in sample consumption and high data collection efficiency. As these protocols become more standardized and accessible, they will empower researchers to apply high-resolution structural biology to a wider array of biologically critical but sample-limited targets. Future developments will likely focus on further integrating these methods with advanced data processing and leveraging predictive algorithms from tools like AlphaFold to streamline the entire pipeline from protein production to structure solution, solidifying the role of SX in modern drug discovery and biochemical research.

Time-Resolved Serial Crystallography (TR-SX) has emerged as a powerful methodology for capturing structural dynamics of biomolecules at atomic resolution across various timescales. This technique enables researchers to visualize reaction intermediates and conformational changes in proteins as they perform their functions, providing direct insight into biochemical mechanisms crucial for life. By combining the principles of serial data collection with pump-probe experimental setups, TR-SX allows the determination of structural movies rather than static snapshots, revealing the intricate details of molecular mechanisms that were previously inaccessible [35]. The technique has undergone significant development in recent years, becoming increasingly accessible at both X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and synchrotron facilities, thus opening new possibilities for studying enzymatic reactions, signal transduction, and other dynamic biological processes [36].

The fundamental advantage of TR-SX lies in its ability to overcome the limitations of traditional crystallographic approaches, which typically provide static structures representing equilibrium states. These conventional methods often require substantial modification of the target protein through mutations or the use of substrate analogs to trap intermediate states, potentially introducing artifacts that don't exist in the wild-type protein or native reaction pathway [35]. In contrast, TR-SX enables direct observation of reaction intermediates without the need for reversible systems or trapping, providing a more authentic view of biomolecular dynamics [35]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying metastable intermediates that are difficult or impossible to trap using traditional methods, revealing hitherto invisible features of protein function including catalysis, allostery, oxidation states, side-chain motions, and molecular breathing [35].

Key Methodological Approaches in TR-SX

Technical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

TR-SX encompasses several specialized techniques tailored to different biological questions, sample types, and temporal resolutions. The main methodological approaches include time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography (TR-SFX) at XFELs, time-resolved serial synchrotron crystallography (TR-SSX) at synchrotron sources, and cryo-trapping time-resolved crystallography. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different experimental needs and scientific questions.

Table 1: Comparison of Major TR-SX Methodologies

| Method | Time Resolution | X-ray Source | Sample Delivery | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR-SFX | Femtoseconds to seconds | XFEL | Liquid injection, LCP | Ultra-fast light-induced reactions, irreversible processes | Ultra-short pulses avoid radiation damage, highest time resolution | Limited access, high sample consumption, complex operation |

| TR-SSX | Milliseconds to seconds | Synchrotron | Fixed-target, viscous injection | Enzyme mechanisms, ligand binding, conformational changes | More accessible, lower sample consumption, easier operation | Lower time resolution compared to XFELs |

| Mix-and-Inject (MISC) | Seconds to milliseconds | Both | Liquid injection | Enzymatic reactions, ligand binding | Studies non-photoactivated proteins, physiological timescales | Mixing efficiency challenges, dead time limitations |

| Cryo-Trapping | Milliseconds upward | Both | Spitrobot-2, manual | Slow enzymatic turnover, metastable intermediates | Compatible with standard MX infrastructure, lower sample needs | Potential vitrification artifacts, not true room-temperature dynamics |

The choice between these methodologies depends on multiple factors, including the scientific question, protein system characteristics, available resources, and desired temporal resolution. TR-SFX at XFELs is unparalleled for studying ultra-fast processes down to the femtosecond regime, utilizing the "diffraction before destruction" principle where ultra-bright femtosecond X-ray pulses capture diffraction patterns before the sample is destroyed by radiation damage [8]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying light-sensitive proteins and irreversible reactions with ultra-fast kinetics. In contrast, TR-SSX at synchrotron facilities, while offering lower time resolution (typically milliseconds to seconds), provides more accessible and democratic access due to wider distribution of synchrotron facilities and lower competition for beamtime [37]. This has enabled the study of a broader range of biological systems and facilitated method development that benefits the entire field.

Sample Delivery Methods and Sample Consumption

A critical aspect of TR-SX is the efficient delivery of fresh crystals to the X-ray beam, as each crystal is typically exposed only once before being destroyed or damaged by radiation. The choice of delivery method significantly impacts sample consumption, which remains a major consideration in experimental design, particularly for precious biological samples that are difficult to produce in large quantities.

Table 2: Sample Delivery Methods in TR-SX

| Delivery Method | Principle | Sample Consumption | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection | Continuous stream of crystal slurry | High (~mg range) | High hit rates, compatible with mixing studies | High sample waste, requires large crystal volumes |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Injection | Viscous matrix for membrane protein crystals | Moderate | Ideal for membrane proteins, reduced flow rate | Specialized setup, not suitable for all proteins |

| Fixed-Target | Crystals deposited on solid support | Low (μg range) | Minimal sample waste, precise positioning | Lower hit rates, potential crystal harvesting issues |

| Hybrid Methods | Combination of approaches | Variable | Customizable for specific needs | Increased complexity |

Recent advancements have substantially reduced sample requirements compared to early TR-SX experiments. Theoretical calculations suggest that, under ideal conditions, a complete dataset could be obtained from as little as 450 ng of protein, assuming microcrystal dimensions of 4×4×4 μm, a protein concentration in the crystal of ~700 mg/mL, and that 10,000 indexed patterns are sufficient for a full dataset [8]. However, practical considerations such as injection efficiency, crystal size distribution, and data quality requirements typically increase the actual sample needs. Fixed-target approaches have emerged as particularly efficient for sample-limited studies, as they minimize the amount of sample that is wasted between X-ray pulses [8]. These systems utilize micro-patterned chips or other solid supports that are raster-scanned through the X-ray beam, dramatically reducing sample consumption compared to continuous injection methods.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Comprehensive Workflow for TR-SSX Experiments

Successful TR-SX experiments require meticulous planning and execution beyond standard crystallographic data collections. The following workflow outlines the key stages for conducting time-resolved serial synchrotron crystallography experiments, based on established best practices [35].

Figure 1: TR-SSX Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages in planning and executing a successful time-resolved serial synchrotron crystallography experiment.

Planning and Feasibility Assessment

The initial planning phase is critical for experimental success. Researchers must first clearly define the scientific question and determine whether TR-SX is the most appropriate technique to address it. Alternative approaches such as classical kinetics, spectroscopy, or trapping methods should be considered, as they may provide sufficient insight with less experimental complexity [35]. Key feasibility considerations include:

Sample Availability: TR-SSX experiments are sample-demanding, typically requiring at least ~5,000 diffraction patterns per structure, with multiple time points needed for a complete time series [35]. Sufficient protein must be available for extensive crystallization trials and data collection.

Crystallization Reproducibility: The protein should crystallize readily to yield a sufficient supply of reproducible microcrystals with consistent size and diffraction quality. Crystal size typically ranges from 1-20 μm for most delivery methods [8].

Diffraction Quality: Crystals must diffract to sufficient resolution to answer the scientific question. While lower resolutions (~3 Å) can reveal gross protein motions, near-atomic resolution (<2 Å) is required to observe bond formation/breakage, water network alterations, and subtle conformational changes [35].

Reference Structures: Prior to any time-resolved study, reference structures of the ground state should be determined, ideally by SSX at room temperature, to assess whether crystal packing will permit the reaction to proceed and accommodate expected conformational changes [35].

Sample Preparation and Characterization

Robust sample preparation is foundational to successful TR-SX experiments. This stage involves optimizing crystal growth conditions to produce large quantities of high-quality microcrystals with uniform size distribution. Key steps include:

Microcrystal Optimization: Standard crystallization conditions may need to be modified to yield microcrystals instead of large single crystals. Techniques such as batch crystallization, vapor diffusion with altered precipitant concentrations, or seeding approaches can be employed.

Crystal Homogeneity: Size uniformity is critical for consistent reaction initiation and data quality. Filtration or size-separation techniques may be necessary to achieve monodisperse crystal suspensions.

Sample Characterization: Dynamic light scattering (DLS) or UV-visible spectroscopy should be used to assess crystal size distribution and concentration. The crystal slurry should be characterized for stability over time to ensure consistency during data collection.

Ligand and Substrate Preparation: For mix-and-inject experiments, ligands must be prepared at appropriate concentrations in compatible buffers, considering potential effects on crystal stability upon mixing.

Reaction Initiation and Data Collection

The core of TR-SX involves precisely initiating reactions and collecting diffraction data at defined time points. The specific approach depends on the reaction type and timescale:

Light-Based Activation: For photosensitive proteins, reactions are typically initiated by short laser pulses synchronized with X-ray exposures. Laser parameters (wavelength, pulse duration, energy) must be optimized for complete and uniform photoactivation [38]. BioCARS, for example, offers laser systems with ps-ns pulse durations, tunable wavelengths from UV to IR, and repetition rates up to 1 kHz [38].

Mix-and-Inject Serial Crystallography (MISC): For enzymatic reactions, substrates are rapidly mixed with protein crystals immediately before X-ray exposure. This requires specialized mixing devices such as the Spitrobot-2, which enables mixing and cryo-trapping with delay times as short as 23 ms [37], or continuous-flow mixers for liquid injection.

Delay Time Series: A series of time points must be collected to reconstruct the reaction trajectory. Time points should be spaced appropriately for the reaction kinetics, typically determined by prior spectroscopic studies.