Advanced Optimization Techniques for Protein Structure Determination from X-ray Crystallography Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing protein structure determination using X-ray crystallography.

Advanced Optimization Techniques for Protein Structure Determination from X-ray Crystallography Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing protein structure determination using X-ray crystallography. It covers foundational principles of serial crystallography and sample delivery, explores advanced methodological applications for challenging targets like membrane proteins, details practical troubleshooting for common experimental hurdles, and discusses modern validation frameworks. By integrating the latest advancements in reduced sample consumption, AI-driven phasing, and data processing from 2025 research, this resource aims to enhance structural biology efficiency and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

Understanding Modern X-ray Crystallography: From Basic Principles to Serial Data Collection

Core Principles of Protein X-ray Crystallography and Structure Determination

Protein X-ray crystallography is a foundational technique in structural biology that enables the determination of atomic-resolution three-dimensional structures of proteins by analyzing the diffraction patterns produced when X-rays interact with a protein crystal [1] [2]. Since its inception, this powerful method has enabled high-resolution structural determination of a plethora of biomolecules, with over 200,000 protein structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1]. The knowledge gained from these structures has revolutionized our understanding of biological function, molecular mechanisms, and has played a key role in rational drug design, including providing structural insights to combat recent global health challenges [1].

The technique relies on the principle that the regular, repeating arrangement of protein molecules in a crystal lattice acts as a diffraction grating for X-rays, scattering them in specific directions to produce a characteristic pattern of spots [2]. The core challenge of the "phase problem" - the loss of phase information during diffraction measurement - must be overcome to calculate an electron density map into which an atomic model of the protein can be built [3] [2]. Recent advances in serial crystallography, computational methods, and integration with predictive algorithms like AlphaFold are continuously expanding the capabilities and applications of this transformative technology [1] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

Bragg's Law and the Physical Basis of Diffraction

X-ray diffraction occurs due to the scattering of electromagnetic waves by the electrons within the crystal lattice. Each electron, when struck by the X-ray beam, acts as a miniature X-ray source [2]. The scattered waves from all electrons in each atom combine in a process known as interference - in certain directions the waves cancel each other out (destructive interference), while in others they reinforce and increase in amplitude (constructive interference) [2].

In Bragg's model of diffraction, the crystal lattice is viewed as a series of atomic layers that reflect the X-rays striking the crystal [2]. Constructive interference occurs when the path difference between waves reflected from successive layers is an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength. This relationship is mathematically expressed by Bragg's Law:

nλ = 2d sinθ

Where:

- n is an integer (order of reflection)

- λ is the wavelength of the incident X-rays

- d is the interplanar distance in the crystal

- θ is the incident angle of the X-rays [2]

By varying the θ angle, different planes of the crystal are brought into positions of constructive interference, enabling comprehensive data collection [2].

Resolution and Data Quality

The resolution of X-ray data is the primary experimental parameter determining the final quality of a protein crystallographic structure model [2]. It depends on the number of diffraction spots collected, with more spots providing information from Bragg planes with shorter interplanar distances, yielding finer details in the calculated electron density map [2].

Table 1: Interpretation of Resolution Ranges in Protein Crystallography

| Resolution Range | Structural Details Observable | Model Building Capability |

|---|---|---|

| Low (5.0 Å and below) | Overall protein shape distinguishable; α-helices visible as rods | No detailed amino acid building possible |

| Medium (3.5-2.5 Å) | Side chains begin to be distinguishable | Model can be built; water molecules may be visible |

| High (2.4 Å and better) | Atomic details become clear | Many solvent molecules identifiable; model building becomes precise |

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

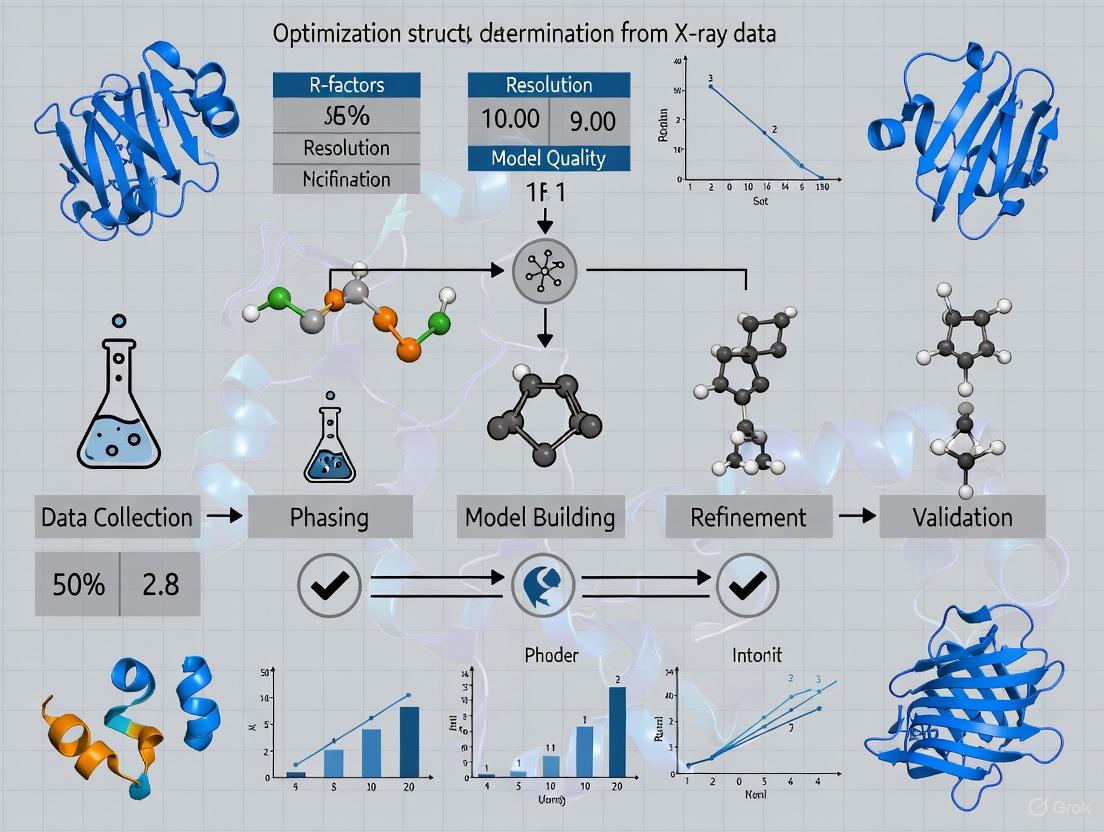

The complete process of determining a protein structure via X-ray crystallography follows a multi-stage workflow, from protein production to final model validation and deposition.

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for protein structure determination by X-ray crystallography. Key optimization points (yellow) include crystallization, phase determination, and model building.

Protein Crystallization Protocols

Initial Crystal Screening

Purpose: To identify initial conditions that promote protein crystallization using sparse matrix screens.

Materials:

- Purified, concentrated protein (>10 mg/mL in low-salt buffer)

- 96-well crystallization screening kits (commercial or custom)

- Crystallization plates (sitting-drop or hanging-drop vapor diffusion)

- Sealing tapes or oils

- Automated liquid handling system (e.g., mosquito Xtal3) [5]

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Label crystallization plates and add reservoir solutions (50-100 μL) to each well using an automated dispenser or multichannel pipette.

- Drop Setup: For each condition, mix:

- 100-200 nL protein solution

- 100-200 nL reservoir solution Use crystallization robots like the mosquito Xtal3 for precise nanoliter-scale dispensing [5].

- Sealing: Seal plates with transparent tape to prevent evaporation.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at constant temperature (4°C, 20°C, or 37°C) without disturbance.

- Monitoring: Check plates regularly under a microscope for crystal formation (days to weeks).

Crystal Optimization

Purpose: To refine initial crystallization hits to produce larger, well-ordered crystals.

Materials:

- Optimized crystallization screens (customized using systems like dragonfly with MXone mixer) [5]

- Additive screens

- Microseeding tools

Procedure:

- Grid Screening: Set up fine-scale screens around initial hit conditions, varying:

- Precipitant concentration (±10-40% of original)

- pH (±0.2-0.5 units)

- Temperature (4°C, 20°C, 37°C)

- Additive Screening: Include additives (0.1-5% concentration) such as salts, detergents, or small molecules.

- Seeding: Transfer microcrystals from initial hits to new drops to promote growth.

- Evaluation: Assess crystal quality by size, morphology, and ultimately by X-ray diffraction.

Data Collection Strategies

Crystal Cryoprotection and Mounting

Purpose: To preserve crystal structure during data collection by preventing ice formation and radiation damage.

Materials:

- Cryoprotectant solutions (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol, sucrose)

- Cryo-loops of appropriate sizes

- Liquid nitrogen storage Dewars

- Synchrotron beamline or in-house X-ray source

Procedure:

- Cryoprotectant Testing: Test cryoprotectant solutions by adding them to reservoir solution at increasing concentrations (5-25%).

- Soaking: Soak crystals in final cryoprotectant solution for 5-30 seconds.

- Mounting: Mount crystal in cryo-loop and flash-cool in liquid nitrogen stream.

- Storage: Transfer to liquid nitrogen Dewar for storage or shipping to synchrotron.

X-ray Data Collection

Purpose: To collect complete, high-quality diffraction data.

Materials:

- Synchrotron beamline with robotic sample changer

- X-ray detector

- Goniometer for crystal positioning

Procedure:

- Screening: Collect preliminary diffraction images to assess crystal quality.

- Strategy Calculation: Use beamline software to determine optimal data collection strategy.

- Data Collection: Collect complete dataset by rotating crystal through appropriate angular range with optimal exposure time.

- Assessment: Monitor data quality metrics (resolution, completeness, signal-to-noise) during collection.

Modern Serial Crystallography Methods

Serial crystallography (SX) has revolutionized structural biology by enabling high-resolution structure determination from microcrystals, studying reaction mechanisms, and expanding the range of biomolecules amenable to structural analysis [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for proteins that only form small crystals or for time-resolved studies.

Table 2: Sample Delivery Methods in Serial Crystallography

| Method | Principle | Sample Consumption | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Target | Crystals are arrayed on a solid support and scanned through X-ray beam | Very low (nanograms) | Precious samples, high-throughput screening |

| Liquid Injection | Crystal slurry is continuously injected as a liquid jet | High (milligrams) | Abundant samples, time-resolved studies |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion | Crystals are embedded in viscous matrix and extruded | Medium (micrograms) | Reduced flow rate, lower sample consumption |

| Hybrid Methods | Combination of fixed support with flow capabilities | Variable | Flexible experimental designs |

The theoretical minimum sample requirement for a complete SX dataset is approximately 450 ng of protein, assuming microcrystal dimensions of 4×4×4 μm, protein concentration of 700 mg/mL in the crystal, and 10,000 indexed patterns [1]. Recent advances have dramatically reduced sample consumption from gram quantities in early experiments to microgram amounts today [1].

Structure Solution and Refinement

Phase Determination Protocols

Molecular Replacement

Purpose: To determine initial phases using a known homologous structure.

Materials:

- Homologous search model (from PDB or AlphaFold prediction)

- Molecular replacement software (PHASER, MOLREP)

- Processed diffraction data (amplitudes |F|)

Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Edit search model to match target sequence and remove non-conserved regions.

- Rotation Function: Search for correct orientation of model in unit cell.

- Translation Function: Determine position of correctly oriented model.

- Phase Calculation: Generate initial phases from positioned model.

- Model Building: Use experimental density to correct and rebuild model.

Experimental Phasing (SAD/MAD)

Purpose: To determine phases experimentally using anomalous scatterers.

Materials:

- Derivative crystals with incorporated heavy atoms

- Single- or multi-wavelength diffraction data

- Experimental phasing software (AutoSol, SHARP)

Procedure:

- Heavy Atom Derivatization: Soak crystals in heavy atom solutions or incorporate selenomethionine.

- Data Collection: Collect single-wavelength (SAD) or multi-wavelength (MAD) data.

- Substructure Solution: Locate heavy atom positions in unit cell.

- Phase Calculation: Calculate experimental phases from anomalous differences.

- Density Modification: Improve phases through solvent flattening and histogram matching.

Advanced Computational Integration

Recent advances in machine learning have transformed structural biology, enabling new approaches to structure determination. The ROCKET method augments AlphaFold2 by refining its predictions using experimental data from cryo-EM, cryo-ET, and X-ray crystallography [4]. This approach captures biologically important structural variation that AlphaFold2 alone does not, automating difficult modeling tasks such as flips of functional loops and domain rearrangements [4].

For low-resolution data, the XDXD framework represents a breakthrough as the first end-to-end deep learning approach to determine a complete atomic model directly from low-resolution single-crystal X-ray diffraction data [3]. This diffusion-based generative model bypasses the need for manual map interpretation, producing chemically plausible crystal structures conditioned on the diffraction pattern [3]. On a benchmark of 24,000 experimental structures, XDXD achieved a 70.4% match rate for structures with data limited to 2.0 Å resolution, with a root-mean-square error (RMSE) below 0.05 [3].

Optimization Techniques and Advanced Applications

Temperature Considerations in Data Collection

While more than 90% of protein crystal structures in the PDB were determined at cryogenic temperatures (100 K), growing awareness of potential artifacts and loss of physiologically relevant information has driven increased interest in data collection at room temperature or body temperature (37°C) [6]. Temperature significantly influences atomic motions and protein flexibility, which play crucial roles in enzymatic catalysis and allosteric communications [6].

Protocol for Temperature-Dependent Studies:

Purpose: To investigate temperature effects on protein structure and metal binding.

Materials:

- Temperature-controlled crystallography systems

- Dehydration prevention devices

- Reduced exposure data collection strategies

Procedure:

- Crystal Stability: Test crystal stability at target temperature prior to data collection.

- Radiation Damage Mitigation: Collect data with attenuated beam and multiple crystal positions.

- Hydration Maintenance: Ensure crystal remains hydrated throughout data collection.

- Rapid Data Collection: Use modern fast detectors to complete data collection before significant radiation damage occurs.

Studies of metal-protein adducts at body temperature have revealed that temperature can affect both protein conformation and metal coordination geometry, providing more physiologically relevant structural information [6]. For example, research on hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL) adducts with rhenium compounds showed that while Re binding sites were retained at 37°C with minor modifications, lower occupancy or absence of Re-containing fragments was observed in non-covalent binding sites compared to cryogenic structures [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Identify initial crystallization conditions | Commercial sparse matrix screens cover diverse chemical space |

| Cryoprotectants (glycerol, PEG) | Prevent ice formation during cryocooling | Must be optimized for each crystal type to avoid damage |

| Heavy Atom Compounds | Experimental phasing via anomalous scattering | Soaking concentrations and times require optimization |

| Ligands/Substrates | Study protein-ligand interactions | Co-crystallization or soaking approaches possible |

| Crystallization Robots | Automated nanoliter-scale setup | mosquito Xtal3 enables 30-50 nL drops for screening [5] |

| Liquid Handling Systems | Custom screen preparation | dragonfly with MXone mixer enables rapid optimization [5] |

| Synchrotron Beam Access | High-intensity X-ray source | Essential for weakly diffracting crystals and time-resolved studies |

| Cryo-EM for Small Proteins | Structure determination when crystallization fails | Coiled-coil fusion strategy enables study of small proteins like kRasG12C [7] |

Data Validation and Quality Assessment

The final step in any crystallographic structure determination is rigorous validation of the structural model. Key quality metrics include the R-factor and R-free, which assess how well the model explains the experimental data, with lower values indicating better agreement [2]. Additionally, validation tools assess stereochemical parameters (bond lengths, angles, torsion angles) and compare them to expected values from high-quality structures [2].

The resulting structural model, along with the experimental data and metadata, is typically deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), which runs its own validation before releasing the structure to the public [2]. When selecting structures from the PDB for research applications, it is essential to assess validation reports and consider resolution, R-factors, and geometric quality to ensure the structural model is appropriate for the intended use [2].

Serial crystallography (SX) represents a paradigm shift in macromolecular structure determination, emerging initially at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and later adapted to synchrotron sources. This approach distributes radiation damage across thousands of microcrystals, enabling room-temperature data collection that captures protein structures in near-physiological states with minimal radiation damage. Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) utilizes ultrafast XFEL pulses that outrun most radiation damage processes through the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle, making it ideal for studying irreversible reactions and radiation-sensitive systems. Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) adapts this methodology to synchrotron radiation sources, where exposure times are necessarily longer but beam access is more readily available. The development of high-viscosity injectors, particularly those using lipidic cubic phase (LCP), has dramatically reduced sample consumption from gram quantities to milligram or even microgram levels, opening these techniques to a broader range of biological targets, including challenging membrane proteins [8] [1] [9].

Table: Fundamental Characteristics of SFX and SMX

| Feature | SFX (X-FEL) | SMX (Synchrotron) |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Source | X-ray Free-Electron Laser (XFEL) | Synchrotron storage ring |

| Pulse Duration | Femtoseconds (∼40-75 fs) [9] | Milliseconds (10-50 ms) [10] |

| Key Principle | "Diffraction-before-destruction" [9] | Dose distribution across many crystals [8] |

| Primary Advantage | Outrunning radiation damage; ultrafast time-resolved studies [9] | Wider accessibility; high room-temperature data quality comparable to cryo-data [8] |

| Typical Sample Consumption | ~100 μg - 1 mg per dataset [9] | <1 mg per dataset [8] |

| Data Collection Rate | 30 - 120 Hz [9] | 10 - 50 Hz [8] |

Comparative Performance and Applications

The implementation of SFX and SMX has enabled new scientific inquiries across structural biology. SFX provides unique capabilities for time-resolved studies on femtosecond to millisecond timescales, allowing researchers to capture molecular movies of reaction intermediates. SMX, while not as fast, offers a more accessible route for determining high-quality room-temperature structures of radiation-sensitive proteins and complexes. Room-temperature structures often reveal enhanced conformational flexibility and more biologically realistic ligand-binding states compared to traditional cryo-cooled structures, as freezing can trap non-equilibrium conformations [8] [9].

Table: Representative Experimental Outcomes from SFX and SMX

| Protein Target | Technique | Resolution (Å) | Key Experimental Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriorhodopsin (bR) | SFX (LCP injector) | 2.3 | Time-resolved study with 1 ms delay; sample consumption ~1 mg/time point [9] | Weierstall et al., 2014 |

| Bacteriorhodopsin (bR) | SMX (LCP injector) | 2.4 | Room-temperature structure; similar to SFX but with distinct retinal pathway details [10] | Nogly et al., 2015 |

| Mo Storage Protein (MOSTO) | SMX | ~1.8 | High-resolution structure of radiation-sensitive protein [8] | Botha et al., 2017 |

| A2A Adenosine Receptor | SMX | ~2.2 | Native sulfur-SAD phasing demonstrated [8] | Botha et al., 2017 |

| Tubulin-Darpin Complex | SMX | ~2.1 | Successful soaking of drug colchicine demonstrated [8] | Botha et al., 2017 |

SMX Experimental Protocol: LCP-Based Sample Delivery

Materials and Equipment

- Purified Protein: 9-15 mg/mL in appropriate detergent (e.g., 1.2% β-OG for bacteriorhodopsin) [10]

- Monoolein: Lipid for forming lipidic cubic phase [10]

- Precipitant Solution: e.g., 29-38% PEG 2000, 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 5.6 [10]

- Syringe Coupler: For mixing protein and lipid [10]

- High-Viscosity Injector: LCP injector with 20-75 μm diameter nozzles [8] [9]

- Synchrotron Microfocus Beamline: Equipped with high-frame-rate detector (e.g., EIGER 16M) [8]

Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Crystallization in LCP:

- Mix purified protein with monoolein in a 40:60 (v/v) ratio using syringe coupler [10].

- Extrude mixture repeatedly (20-30 passes) to form homogeneous LCP.

- Load LCP into 100 μL syringe and overlay with precipitant solution.

- Incubate at 20°C in the dark until microcrystals form (typically several days) [10].

2. Sample Preparation for Injection:

- Remove excess precipitant solution from crystallization syringe.

- Add pure monoolein to adjust crystal density.

- Homogenize crystal-LCP mixture using syringe coupler to break larger crystals into fragments <50 μm [10].

- Load homogenized sample into LCP injector.

3. Data Collection:

- Align LCP stream (extruded at 50-250 nL/min) with microfocus X-ray beam (e.g., 20 × 5 μm) [8].

- Collect diffraction patterns with 10-50 ms exposure per pattern at 50 Hz frame rate.

- Continue data collection until ~10,000-100,000 patterns are acquired (typically 1-20 hours) [8].

4. Data Processing:

- Index and integrate diffraction patterns using software such as CrystFEL.

- Merge data from all crystals to create complete dataset.

- Solve structure by molecular replacement or de novo phasing.

- Refine structure using standard crystallographic software [8] [10].

SFX Experimental Protocol: Time-Resolved Studies

Materials and Equipment

- Microcrystals: 10-15 μm size for uniform light penetration [9]

- High-Viscosity Injector: LCP injector with 20-50 μm diameter nozzles [9]

- Optical Pump Laser: Femtosecond laser synchronized with XFEL pulses [9]

- XFEL Source: e.g., Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) [9]

Step-by-Step Procedure

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare concentrated microcrystals in LCP as described in SMX protocol.

- Optimize crystal density for hit rates of 5-10% at XFEL repetition rate.

- Load sample into LCP injector.

2. Experimental Setup:

- Align LCP stream with XFEL beam (typically 1.5 × 1.5 μm focus).

- Synchronize optical pump laser with XFEL pulses at desired repetition rate (e.g., 30 Hz pumping with 120 Hz XFEL) [9].

- Set desired time delay between pump and probe pulses.

3. Data Collection:

- Collect single diffraction pattern from each crystal intercepted by XFEL pulse.

- Attenuate X-ray pulses to prevent detector damage while maintaining sufficient signal.

- Acquire 10,000-100,000 indexed patterns per time delay.

4. Data Processing:

- Process data similarly to SMX but account for specific XFEL properties.

- Calculate difference Fourier maps between light-activated and dark states.

- Refine structures for each time delay to reconstruct reaction trajectory [9].

Workflow Visualization

Serial Crystallography Workflow Selection

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Serial Crystallography

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Viscous delivery medium for membrane proteins and microcrystals [9] [10] | Monoolein lipid; protein:lipid ratio ~40:60 (v/v); low extrusion rate (50-250 nL/min) |

| High-Viscosity Injector | Extrudes crystal-laden medium into X-ray beam [8] [9] | Nozzle diameter: 20-75 μm; flow rate: 0.05-2 μL/min; compatible with viscous media |

| High-Frame-Rate Detector | Records diffraction patterns at high repetition rates [8] | EIGER 16M; frame rates: 50-120 Hz; high dynamic range |

| Microfocus Beamline | Provides intense, focused X-ray beam for SMX [8] [10] | Beam size: 5×5 to 20×5 μm²; flux: 10¹¹-10¹² ph/s; compatible with injector setups |

| XFEL Source | Provides ultrafast, high-intensity pulses for SFX [9] | Pulse duration: ~75 fs; repetition rate: 30-120 Hz; high peak brightness |

Serial crystallography (SX), conducted at both synchrotrons and X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), has revolutionized structural biology by enabling high-resolution structure determination at room temperature with minimal radiation damage [1]. This technique relies on collecting diffraction patterns from thousands of microcrystals, each exposed to an X-ray pulse only once, following the "diffraction before destruction" principle [11]. The efficiency of these experiments is fundamentally constrained by the effective delivery of precious crystal samples to the X-ray interaction point. Sample consumption remains a critical challenge, as the limited availability of many biologically significant macromolecules makes efficient use of purified protein essential [1] [12]. Innovations in sample delivery methodologies—primarily categorized as fixed-target, liquid injection, and hybrid systems—are therefore pivotal for optimizing protein structure determination workflows. These systems aim to maximize the crystal hit rate while minimizing sample waste, thereby expanding the range of accessible biological targets, including complex membrane proteins and dynamic enzymatic complexes studied via time-resolved methods [13] [14].

Comparative Analysis of Sample Delivery Methods

The performance of different sample delivery systems can be evaluated based on key parameters such as sample consumption, hit rate, compatibility with time-resolved studies, and operational complexity. The following sections and tables provide a detailed comparison to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate method for their experimental needs.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Sample Delivery Methods

| Method | Typical Sample Consumption | Relative Hit Rate | Compatibility with Time-Resolved Studies | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection (GDVN) | ~10 mg to 1 g [1] [11] | Medium | High (Excellent for mix-and-inject) [1] | Maintains crystal hydration; continuous flow [11] | High sample waste at low repetition rates; shear forces on crystals [11] [13] |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion | ~1-10 mg [11] [13] | High | Medium (Compatible with LCP-grown crystals) [11] | Reduced flow rates; protects sensitive crystals [13] | Potential interactions between matrix and sample [13] |

| Fixed-Target Scanning | <1 mg [1] [15] | High | High (Excellent for pump-probe) [15] [14] | Minimal sample waste; precise crystal positioning [16] [14] | Risk of crystal drying; requires synchronization [15] |

| Droplet-Based Hybrid | Microgram quantities [1] | Medium to High | High [17] | Dramatically reduced sample waste [17] | Requires complex synchronization with X-ray pulses [17] |

Table 2: Theoretical Minimum Sample Requirement for a Complete Dataset

| Parameter | Theoretical Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Indexed Patterns Required | 10,000 | Typical number for a full dataset [1] |

| Assumed Crystal Size | 4 × 4 × 4 µm | Example microcrystal dimension [1] |

| Protein Concentration in Crystal | ~700 mg/mL | Based on a 31 kDa protein (e.g., NQO1) [1] |

| Theoretical Minimum Protein Mass | ~450 ng | Calculated ideal minimum consumption [1] |

Detailed Methodologies and Application Notes

Fixed-Target Systems

Fixed-target methods involve mounting microcrystals onto a solid, stationary support that is then scanned through the X-ray beam [15] [14]. This approach is renowned for its high sample efficiency.

Protocol: Data Collection Using a Cyclic Olefin Copolymer (COC) Fixed-Target Device

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- COC Fixed-Target Chip: Fabricated with up to 18,000 crystal traps, each designed to hold a single crystal up to 50 µm in size. The COC material provides low X-ray background scattering [16].

- Crystal Slurry: A concentrated suspension of microcrystals in their mother liquor or a suitable stabilizing solution.

- Humidity Chamber: To prevent dehydration of crystals during loading and data collection.

Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Apply 1-2 µL of crystal slurry directly onto the surface of the COC chip. Use a gentle air stream or a wicking tool to remove excess mother liquor, ensuring crystals are seated within the traps [16].

- Chip Mounting: Secure the loaded chip into the sample holder of the fixed-target sample chamber (e.g., the FT-SFX chamber at PAL-XFEL) [15].

- Alignment: Align the chip relative to the X-ray beam path using the chamber's translation stages and real-time microscopy monitoring.

- Data Collection Scripting: Program a raster scanning pattern. The scan parameters (step size, speed) should be optimized to match the XFEL repetition rate (e.g., 60 Hz at PAL-XFEL) and ensure no crystal is hit twice [15].

- Data Collection: Initiate the scanning sequence and X-ray exposure. For weak diffraction signals, conduct the experiment in a helium-purged environment to minimize air scattering [15].

Workflow Diagram

Fixed-Target Experimental Workflow

Liquid Injection Systems

Liquid injectors continuously deliver a stream of crystal suspension into the X-ray beam. A major innovation in this category is the Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN), which uses a co-flowing gas to focus a liquid jet down to micrometer diameters, preventing clogging [11].

Protocol: SFX using a GDVN Injector at an XFEL

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- GDVN Nozzle: Consists of a tapered liquid capillary (e.g., 50 µm inner diameter) surrounded by a coaxial gas capillary. The helium gas flow focuses the liquid jet to diameters as small as 4 µm [11] [13].

- High-Pressure HPLC Pump: Delivers the crystal suspension at a stable, pressurized flow.

- Crystal Suspension: A homogeneous slurry of microcrystals at a high concentration (e.g., 10⁹ to 10¹⁰ crystals/mL) [11].

Procedure:

- Nozzle Preparation: Assemble the GDVN nozzle ensuring the liquid and gas capillaries are clean and aligned.

- Sample Loading: Load the crystal suspension into the sample reservoir, taking care to avoid sedimentation.

- Injector Alignment: Install the nozzle into the injection chamber (e.g., the MICOSS system at PAL-XFEL) and align the jet to intersect the X-ray beam using in-line cameras [13].

- Flow Initiation: Start the liquid flow and adjust the liquid pressure (typically to achieve ~10 µL/min) and gas pressure to establish a stable, unbroken jet.

- Data Collection: Trigger the X-ray pulses and detector to record diffraction patterns from crystals randomly oriented in the jet. A full dataset often requires several hours of continuous operation and 10-100 mL of sample suspension [11].

To address the high sample waste of continuous jets, high-viscosity injectors have been developed. These extrude crystals embedded in a media like lipidic cubic phase (LCP) or other viscous matrices at flow rates as low as 300 nL/min, drastically reducing consumption [11] [13].

Hybrid Delivery Systems

Hybrid systems combine features of both injector and fixed-target methods to leverage their respective advantages. A prominent example is the droplet-on-demand system, which generates segmented crystal-laden droplets separated by an immiscible oil [17].

Protocol: Droplet-Based Sample Delivery for Reduced Waste

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- 3D-Printed Microfluidic Chip: Integrates droplet generation and nozzle injection in a single device. Contains channels for sample and immiscible oil.

- Immiscible Oil Phase: A biocompatible oil (e.g., perfluorinated oil) that acts as a spacer between aqueous sample droplets.

- Precision Syringe Pumps: To control the flow rates of both the sample and oil phases.

- Electrical Triggering System: For synchronizing droplet generation with XFEL pulses [17].

Procedure:

- Device Priming: Prime the microfluidic channels with the immiscible oil to ensure stable droplet formation.

- Droplet Generation: Initiate flow of both the crystal suspension and the oil. The device geometry generates monodisperse aqueous droplets within the oil stream.

- Synchronization: Use the electrical triggering system to synchronize the release of droplets so that a fresh droplet arrives at the X-ray interaction point for each XFEL pulse. This ensures that sample between pulses is oil, not precious crystal suspension [17].

- Injection and Data Collection: The droplet stream is injected into the chamber towards the X-ray beam. Diffraction data is collected only when a droplet is in the beam path.

Workflow Diagram

Hybrid Droplet-Based Experimental Workflow

Integrated System for Time-Resolved Studies

Fixed-target and hybrid systems are particularly advantageous for time-resolved serial crystallography (TR-SX), which aims to capture molecular movies of biochemical reactions [1] [14]. Fixed-target chips allow for precise reaction initiation on the chip itself, either by light (pump-probe) or by rapid mixing of substrates with crystals, followed by scanning at defined time delays [14]. The consistency in sample preparation and delivery between synchrotron (SSX) and XFEL (SFX) sources when using fixed targets allows for direct comparison of structures across time scales and facilities, validating observed conformational changes [14].

The ongoing innovation in sample delivery systems is a cornerstone of modern protein structure determination. Fixed-target, liquid injection, and hybrid methods each offer distinct profiles of sample efficiency, operational complexity, and applicability to dynamic studies. The choice of system must be tailored to the specific protein target, the scientific question—particularly for time-resolved experiments—and the available beamline infrastructure. As these technologies continue to mature, converging towards the theoretical minimum of sample consumption, they will unlock unprecedented opportunities for determining the structures of previously intractable biological macromolecules and visualizing their functional dynamics in real time.

The field of structural biology is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the ability to generate data at an unprecedented scale. The advent of high-throughput techniques, particularly in crystallographic fragment screening, is revolutionizing drug discovery but simultaneously precipitating a data management crisis. With specialized synchrotron facilities capable of conducting over 150 fragment-screening campaigns annually—a number poised to exceed 1,000 as global facilities reach full capacity—the research community faces the challenge of managing an estimated one million individual diffraction datasets and up to 100,000 new protein-ligand structures each year [18]. This deluge of data, often reaching terabyte scales per campaign, necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of traditional data processing, storage, and archival practices. This application note details the current landscape, quantitative challenges, and essential protocols for managing terabyte-scale crystallography datasets within the broader context of optimizing protein structure determination workflows.

The Quantitative Scale of the Data Challenge

The transition to high-throughput methods has fundamentally altered the data volume in crystallography. The table below quantifies key aspects of this data revolution, highlighting the immense scale and its implications for data management.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of High-Throughput Crystallography Data Generation

| Aspect | Traditional Crystallography | High-Throughput Fragment Screening | Data Management Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campaigns/Year | Dozens | >150 (currently), ~1,000 (projected at capacity) [18] | Linear scaling of raw data and results requiring storage |

| Datasets/Campaign | 1 - 10 | ~1,000 compounds [18] | Millions of datasets annually across all facilities |

| Structures/Year | ~10,000 new crystal structures in PDB [18] | ~100,000 additional protein-ligand structures [18] | Overwhelms traditional deposition and curation pipelines |

| Data Arrival Rate | Hours to days | Seconds after collection at detector [19] | Requires real-time streaming and processing infrastructure |

| Representative Data Volume | Gigabytes (GB) | Terabytes (TB) to hundreds of TB [19] | Demands scalable, high-performance storage architectures |

This exponential growth is not limited to fragment screening. Other applications, such as the masked autoencoder for X-ray image encoding (MAXIE), are trained on datasets as large as 286 terabytes of X-ray diffraction images [19]. Furthermore, at facilities like the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS-II), X-ray laser shot repetition rates have increased to 1 MHz, generating electron time-of-flight data with sub-femtosecond resolution and creating immense data streams that require online analysis for experimental steering [19].

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Data Management

Protocol: Implementing an End-to-End Data Streaming Framework

Coupling high-performance computing (HPC) resources with external, online data sources is critical for real-time analysis. The LCLStream ecosystem provides a proven framework for this purpose [19].

- Objective: To enable real-time streaming of experimental data from detectors to remote HPC resources for immediate processing and analysis.

- Materials:

- LCLStream API Server or equivalent middleware.

- High-rate data buffer (e.g., NNG-Stream).

- Mutual authentication framework (certificate-driven).

- HPC cluster with access to data processing libraries (e.g., psana2).

- Procedure:

- Data Request: An external user or beamline system requests a specific dataset from an active experiment using a REST API with a JSON-formatted query [19].

- Mutual Authentication: The user and server authenticate each other using digital certificates to ensure security [19].

- Job Launch: The API server creates a unique JobID and launches the

LCLStreamerandNNG-Streamcomponents on the local computing cluster (e.g., SLAC's S3DF cluster) [19]. - Data Reduction & Streaming: The

LCLStreamerapplication reads event data using facility-specific libraries (e.g., psana2), performs user-defined partial data reduction, and formats the output. - Buffered Transfer: The

NNG-Streamcomponent buffers data between parallel producers and consumers, smoothing network bursts and enabling traversal of complex network topologies [19]. - Data Consumption: Processed data is delivered to external applications, which can include supercomputer centers for AI training, network appliances, or automated control systems for experimental feedback [19].

- Outcome: Preliminary results show data can arrive at a remote HPC job, such as one at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, just seconds after collection at detectors in Menlo Park, enabling near-real-time analysis [19].

Protocol: Architectural Design for Scalable Data Management

Proper data management must be considered from the first day of setting up an imaging or crystallography lab to avoid costly data recovery and organizational problems later [20].

- Objective: To establish a scalable and accessible data management architecture for large, heterogeneous crystallography datasets.

- Materials:

- Managed web-browser interface (e.g., DigiM I2S or similar).

- Relational database for metadata indexing.

- Scalable storage solution (cloud, NAS, or server).

- Computational resources for automated processing.

- Procedure:

- Automated Cataloguing: Implement a system that automatically generates visual thumbnails of datasets upon ingestion, creating a searchable visual catalogue [20].

- Metadata Capture: Record all experimental metadata (e.g., date stamps, user, sample information, beamline parameters) concurrently with data acquisition into a relational database [20].

- Workflow Integration: Conduct data analysis within the managed environment so that all processing steps, parameters used, and derived data are automatically recorded and annotated [20].

- Queue Management: Utilize a job queuing system that allows users to submit long computational tasks and receive email notifications with hyperlinks to results upon completion [20].

- Universal Indexing and Search: Ensure that every piece of data, metadata, and analysis result is indexed and made searchable through the browser interface, moving beyond simple file explorer capabilities [20].

- Plan for Scaling: Adopt a nested client-server architecture that abstracts user access, computing, and storage needs through API layers, allowing the system to scale from dozens to thousands of datasets and users [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and components of this managed architecture.

Data Management Architecture: Logical workflow for a scalable system that integrates data storage, metadata indexing, and computational processing.

Computational Workflows for Automated Structure Determination

The volume of data generated by high-throughput crystallography makes manual processing impossible. Automated software pipelines are essential.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for High-Throughput Data Processing

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Key Feature | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoPD [21] | Automated meta-pipeline | Integrates AlphaFold-assisted molecular replacement and adaptive decision-making | High-throughput structure determination from raw data to model |

| APEX Suite [22] | Instrument control to publication | AI-based crystal centering and STRUCTURE NOW plugin for automated solution | Laboratory (in-house) single-crystal X-ray diffraction |

| PanDDA [18] | Hit-finding from fragment screens | Pan-Dataset Density Analysis to identify low-occupancy binders | High-throughput crystallographic fragment screening |

| DIALS [23] | Data integration | Modern package designed for data from synchrotrons and XFELs | Processing challenging datasets from modern sources |

| LCLStreamer [19] | Data streaming & reduction | Flexible API-driven data requests and real-time streaming to HPC | On-line data analysis and experimental steering at large facilities |

Protocol: Automated Structure Determination with AutoPD

AutoPD is an open-source meta-pipeline designed to address the automation challenge from raw data to high-precision structural models [21].

- Objective: To automatically determine a protein structure from raw diffraction data and an amino acid sequence file.

- Materials:

- Raw diffraction images (e.g., in HDF5 or SMV format).

- Protein amino acid sequence file (FASTA format).

- Access to a high-performance computing cluster.

- AutoPD software installation.

- Procedure:

- Data Ingestion and Integration: AutoPD ingests the raw diffraction images and performs initial data reduction (indexing, integration, and scaling) using integrated processing engines [21].

- Adaptive Decision-Making: The pipeline dynamically selects the optimal structure modeling pathway based on data quality and intermediate results [21].

- Structure Solution:

- Model Building and Refinement: The pipeline performs iterative cycles of automated model building and refinement.

- Validation and Output: The final model and electron density maps are generated and validated. The pipeline achieves a success rate of 92% on benchmark datasets, with map-model correlation values of at least 0.5 [21].

The workflow of this automated pipeline, highlighting its adaptive decision points, is shown below.

AutoPD Workflow: Automated pipeline for protein structure determination that adaptively chooses the best solution path.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful navigation of the data revolution requires both cutting-edge software and robust physical materials. The following table details essential reagents and materials for high-throughput crystallography workflows, with a focus on membrane proteins as a challenging and biologically relevant case study [24].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Throughput Crystallography

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Types / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Cloning and expressing the target protein; tags aid purification. | pET20b, pET-DUET, pRSF-1b; often modified with N-terminal pelB signal sequence and His-tags [24]. |

| Host Cell Lines | Protein expression system; different lines address toxicity and codon usage. | BL21(DE3) for standard expression; C41/C43 for toxic genes; Rosetta for rare codons [24]. |

| Detergents | Solubilizing and stabilizing membrane proteins post-cell lysis. | DDM, LDAO, OG, C8E4, LMNG; must be kept above critical micelle concentration (CMC) [24]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Primary purification step to isolate the target protein from cell lysate. | Ni-NTA resin for His-tagged proteins; Strep-Tactin resin for Strep-tagged proteins [24]. |

| Crystallization Screens | Initial screening of conditions to nucleate protein crystals. | Commercial screens specifically marketed for membrane proteins (e.g., MemGold, MemSys) [24]. |

| Lipid/Additive Supplements | Enhancing protein stability and promoting crystallization. | Cholesterol, specific lipids; used as additives in purification or crystallization buffers [24]. |

| Rare-Earth Doped Crystals | Potential future medium for high-density data storage. | Praseodymium-doped Yttrium oxide; uses crystal defects for atomic-scale memory cells [25] [26]. |

The data revolution in crystallography is an undeniable reality. The paradigms of manual data handling and processing are no longer viable in an era of terabyte-scale campaigns. The future of efficient protein structure determination hinges on the widespread adoption of the integrated strategies outlined in this note: real-time data streaming frameworks, scalable and managed data architectures, and highly automated computational pipelines. Furthermore, the community must collectively address the impending challenge of data archival, as current procedures for deposition into the Protein Data Bank are not designed for the influx of hundreds of thousands of structures annually from fragment screens alone [18]. Embracing this revolution by implementing robust data management protocols is no longer optional but a fundamental requirement for continued success in structural biology and structure-based drug discovery.

Current Market and Technology Landscape for Protein Crystallography

The global protein crystallography market is experiencing robust growth, propelled by its indispensable role in structural biology and rational drug design. By creating ordered, structured lattices for complex macromolecules, this technique enables high-resolution structure determination that is crucial for understanding biological function and developing targeted therapeutics [27]. The market's expansion is fundamentally driven by increasing demand for protein-based therapeutics, rising investments in biopharmaceutical research and development (R&D), and continuous technological advancements that enhance experimental throughput and success rates [27] [28].

Table 1: Global Protein Crystallography Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Size Year | Market Value (USD Billion) | Projected Year | Projected Value (USD Billion) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 1.62 | 2029 | 2.8 | 11.5% | [28] |

| 2024 | 6.80 | 2032 | 19.41 | 14.00% | [29] |

| 2025 | 1.82 | 2029 | 2.8 | 11.5% | [28] |

The growing adoption of biologics, including monoclonal antibodies and engineered enzymes, has created a sustained need for atomic-level structural data to support regulatory filings. Notably, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) has informed over 80% of antineoplastic approvals from 2019-2023, cementing structural evidence as a central component of drug dossiers [27]. Concurrently, substantial R&D investments from both public and private sectors are legitimizing capital expenditures on advanced crystallography platforms. Examples include the U.S. National Science Foundation's $40 million Use-Inspired Protein Design initiative and Thermo Fisher Scientific's $1.3 billion R&D expenditure in 2023, a substantive share of which was devoted to protein-analysis platforms [27].

Market Segmentation and Technological Trends

Analysis by Product, Technology, and End-User

The protein crystallography market can be segmented by product, technology, and end-user, each revealing distinct trends and growth trajectories.

Table 2: Market Segmentation and Key Characteristics (2024-2025)

| Segment | Category | Market Share or CAGR | Key Characteristics and Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Product | Instruments | 44.23% of market size (2024) [27] | Includes X-ray diffractometers, liquid handlers, imaging systems. Purchasers prioritize photon-counting detectors and robotic samplers. |

| Software & Services | 12.19% CAGR [27] | Fastest-growing segment. Cloud-native suites enable remote collaboration and automated data processing. | |

| Reagents & Consumables | Mid-single-digit growth [27] | Steady demand for screens, kits, and cryoprotectants. Innovation in formulations, e.g., sodium-malonate. | |

| By Technology | X-ray Crystallography | 56.15% market share (2024) [27] | Dominant, well-established method. Ongoing detector upgrades tighten experimental cycle times. |

| Microfluidic Screening | 11.73% CAGR [27] | Offers dramatic sample volume reduction; crystal hits emerge in minutes, not days. | |

| Cryo-electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Complementary growth [27] | Gaining traction for challenging samples but does not displace diffraction in regulatory settings. | |

| By End-User | Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies | 54.22% market share (2024) [27] | Rely on internal beamlines for IP-sensitive targets; anchor commercial demand. |

| Contract Research Organizations (CROs) | 10.24% CAGR [27] | Highest growth due to outsourcing by smaller, cost-conscious firms. | |

| Academic & Research Institutes | Significant share [27] | Anchor basic methodological innovation; benefit from sustained government grants. |

Key Technological Trends Shaping the Field

Several transformative technological shifts are redefining protein crystallography workflows, making them more efficient, accessible, and powerful.

Automation and AI Integration: Crystallization robots with AI-powered screening capabilities are transforming the traditional trial-and-error paradigm into a data-driven process [29]. These systems can design, execute, and analyze hundreds of crystallization conditions in parallel, learning from previous outcomes to refine subsequent experiments. In data processing, cloud-native software suites offer automated phasing, model validation, and AI-assisted refinement, significantly accelerating the path from raw data to refined structure [27]. Tools like the AutoPD meta-pipeline demonstrate this trend, integrating AlphaFold-assisted molecular replacement and adaptive decision-making to automate structure determination from raw diffraction data [21].

Miniaturization and Microfluidics: High material cost and scarce protein samples have long throttled crystal growth, particularly for membrane proteins. Microfluidic chips address this challenge by reducing sample needs by an order of magnitude and screening thousands of conditions within minutes [27]. This miniaturization enables affordable fabrication, allowing mid-tier universities to adopt advanced workflows and broadening the technology's user base [27].

Advancements in Serial Crystallography (SX): Serial crystallography, conducted at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and synchrotrons, has revolutionized the field by enabling structure determination from micro- and nano-sized crystals at room temperature [1]. A primary focus of recent SX development has been on reducing sample consumption. While early SX experiments required grams of purified protein, advancements in sample delivery systems have shrunk this requirement to microgram amounts [1]. Efficient sample delivery methods, such as fixed-target systems and liquid injection, are critical for maximizing the potential of SX and expanding its application to a broader range of biologically significant samples [1].

Shift Towards Physiological Temperature Data Collection: There is a growing awareness that routine data collection at cryogenic temperatures (100 K) can introduce artifacts and obscure physiologically relevant conformational dynamics [6]. Consequently, more researchers are exploring data collection at room temperature or even body temperature (37°C) to capture functionally important protein flexibility and more accurate metal coordination geometries, which is particularly relevant for studying metallodrug interactions [6].

Regional Market Dynamics

The adoption and development of protein crystallography technologies vary significantly across geographic regions, influenced by local infrastructure, funding landscapes, and research priorities.

Table 3: Regional Market Analysis (2024)

| Region | Market Share / CAGR | Key Drivers and Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|

| North America | 36.13% of global revenue [27] | Supported by NIH and NSF programs; mature pharma clusters in Massachusetts and California; synchrotrons like APS and SSRL. |

| Asia-Pacific (APAC) | Fastest-growing region (10.05% CAGR through 2030) [27] | Rapidly growing investments in life sciences; China's next-generation synchrotron in Shanghai; government-incentivized public-private partnerships. |

| Europe | Significant share [27] | Coordinated EU investment (e.g., Diamond-II upgrade, European Spallation Source); regulatory harmonization facilitates cross-border research. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microcrystallization of Lysozyme for SFX

Lysozyme is a standard reference protein commonly utilized in initial Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) trials to optimize detector geometry and experimental setup [30]. This protocol details the production of ~5 µm microcrystals at 17°C.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Sodium Acetate Trihydrate | Component of the buffering system to maintain pH. |

| Acetic Acid | Component of the buffering system to maintain pH. |

| Sodium Chloride | Precipitant in the crystallization solution. |

| PEG 6000 (50% w/v) | Precipitant in the crystallization solution. |

| Lysozyme (Egg White) | The target protein for microcrystallization. |

| CellTrics Filter (30 µm) | To isolate microcrystals of the desired size. |

Materials and Equipment

- Sodium acetate trihydrate, Acetic acid, Sodium chloride, PEG 6000 (50% w/v), Lysozyme (egg white) [30]

- pH meter, Graduated beakers, 0.22 µm filters, 50 ml centrifuge tubes (e.g., Falcon) [30]

- Thermonixer C (Eppendorf) with SmartBlock for 50 ml tubes [30]

- High-performance microscope (≥1500 magnification), Refrigerated centrifuge [30]

- CellTrics filter (30 µm), Slide glass and cover glass, Cell counting plate (e.g., OneCell counter) [30]

Procedure

- Preparation of Buffer A (1 M Sodium Acetate Buffer, pH 3.0): Add ~2.5 ml of 1 M sodium acetate to 100 ml of 1 M acetic acid and adjust the solution to pH 3.0 using a calibrated pH meter. Use ultrapure water for all preparations [30].

- Preparation of Crystallization Solution: Combine 10 ml of Buffer A, 28 g of sodium chloride, and 16 ml of 50% (w/v) PEG 6000 in a graduated beaker. Add ultrapure water to bring the mixture close to a final volume of 100 ml. Mix thoroughly for several hours until the sodium chloride is fully dissolved. Adjust the final volume to 100 ml with ultrapure water and pass the solution through a 0.22 µm filter. Store at room temperature for no more than one week to avoid salt precipitation and pH changes [30].

- Crystallization: Transfer 30 ml of the crystallization solution to a 50 ml Falcon tube. While vigorously mixing the solution on a vortex mixer, rapidly add 10 ml of a 100 mg/ml lysozyme solution (in ultrapure water). Immediately place the mixture in a thermomixer and incubate at 17°C for 2 hours without shaking [30].

- Harvesting and Density Measurement: After incubation, concentrate the microcrystals by centrifugation. Resuspend the crystal pellet in 1-2 ml of a suitable harvest solution (e.g., 10% (w/v) sodium chloride, 1 M acetate buffer, pH 3.0). Filter the crystal slurry through a 30 µm CellTrics filter to remove larger aggregates. Determine the crystal density using a cell counting plate under a microscope [30]. The resulting microcrystals are now ready for SFX experiments.

Protocol 2: Sample Delivery in Serial Crystallography

A critical challenge in SX is the efficient use of precious macromolecular samples. This protocol focuses on the overarching workflow for sample delivery in SX experiments.

Workflow Diagram Description: The logical workflow for a serial crystallography experiment begins with the prerequisite of having a purified protein and established conditions to generate microcrystals (1-20 µm) [1]. The crystals are harvested and concentrated into a slurry, which is then loaded into a sample delivery device. The choice of delivery method is critical for efficient sample consumption. Liquid Injection (e.g., jet-based) continuously streams the slurry across the X-ray beam [1]. Fixed-Target methods deposit crystals on a chip that is raster-scanned through the beam, often reducing sample waste [1]. High-Viscosity Extrusion uses media like LCP to slower the flow and reduce consumption [1]. The device is used at an XFEL or synchrotron for data collection, followed by computational processing to generate the final atomic model.

Instrumentation and Data Processing

The hardware and software ecosystem for protein crystallography is evolving rapidly to enhance resolution, speed, and reliability [31]. Core instrumentation includes high-precision X-ray generators (from in-house sources to synchrotrons and XFELs), detectors, goniometers for crystal manipulation, and cryo-cooling systems to preserve crystal integrity by reducing radiation damage [31].

A significant challenge posed by modern, automated data acquisition is the need for equally efficient data processing pipelines. The AutoPD meta-pipeline addresses this need by integrating several advanced computational strategies for automated structure determination [21]:

- Parallel Computing Strategies: Enables high-throughput processing of multiple datasets.

- AlphaFold-Assisted Molecular Replacement: Leverages accurate predicted structures from AlphaFold to solve the phasing problem, a critical step in structure determination.

- Direct-Method-Based Model Building: Provides an alternative approach for model construction, independent of experimental phasing.

- Adaptive Decision-Making: Dynamically selects the optimal modeling pathway (e.g., molecular replacement vs. direct methods) based on data quality and intermediate results, ensuring robustness.

When benchmarked against 186 recently deposited X-ray diffraction datasets, AutoPD successfully determined structures for 92% of cases, demonstrating its utility in addressing the challenges of modern structural biology [21].

Future Outlook

The protein crystallography landscape is poised for continued evolution driven by technological convergence. The integration of AI and machine learning will further permeate all stages, from crystallization condition prediction to automated model building and validation [27] [29]. The ongoing development of more compact and accessible X-ray sources, including potential sub-USD 1 million cryo-EM prototypes, may democratize advanced structural biology capabilities for a broader range of institutions [27].

Furthermore, the focus on studying biological mechanisms under physiologically relevant conditions will intensify. Techniques like time-resolved SFX (TR-SFX) for capturing "molecular movies" of reaction intermediates [1] [30], and the shift towards room-temperature and body-temperature data collection to reveal functional dynamics [6], will move the field from static snapshots to dynamic mechanistic insights. These advancements, combined with streamlined, automated workflows and reduced sample requirements, will solidify protein crystallography's critical role in accelerating drug discovery and deepening our understanding of fundamental biology.

Advanced Applications and Techniques for Challenging Protein Targets

Membrane proteins (MPs) are fundamental to cellular processes such as signal transduction, immune response, and material transport, and they represent over 50% of major drug targets [32] [33]. However, their structural characterization lags significantly behind that of soluble proteins, with MPs constituting less than 3% of the structures in the Protein Data Bank [33]. A primary bottleneck in this process is obtaining well-diffracting crystals, a challenge directly linked to the inherent hydrophobicity of MPs and their complex relationship with the native lipid membrane [32] [34]. Successful crystallization is contingent upon extracting the protein from the membrane and maintaining its stability and monodispersity in a solution environment, which traditionally relies on detergents and specialized membrane mimetics [32] [33]. This application note details optimized protocols for detergent screening and membrane protein crystallization, framed within the broader objective of determining high-resolution structures via X-ray crystallography.

The Membrane Protein Crystallization Challenge

The journey from gene to high-resolution structure of a membrane protein is fraught with technical hurdles. A major initial challenge is obtaining sufficient quantities of the target protein. Because MPs are embedded in the lipid bilayer and can be toxic when overexpressed, their natural abundance is low, necessitating heterologous overexpression [32] [33]. Selecting an appropriate expression system is critical, as each system offers a different balance of cost, throughput, and ability to perform necessary post-translational modifications.

Once expressed, MPs must be extracted from the membrane and stabilized in solution. This is most commonly achieved using detergents, which solubilize the protein by shielding its hydrophobic transmembrane domains [32]. However, detergents are a double-edged sword; while essential for solubilization, they can destabilize proteins, strip away essential lipids, and impede the crystal contacts necessary for forming a well-ordered lattice [32] [35]. The fragile nature of membrane proteins outside their native environment has driven major technical innovations in membrane-mimicking systems beyond conventional detergents, including liposomes, bicelles, and nanodiscs [32] [33]. More recently, detergent-free alternatives like styrene-maleic acid (SMA) and diisobutylene-maleic acid (DIBMA) copolymers have emerged. These polymers can directly solubilize membrane proteins along with a patch of their native lipid environment, forming so-called "native nanodiscs" that can enhance protein stability and preserve functionally relevant lipid interactions [32] [35].

Finally, the crystallization process itself is more complex for MPs. It requires the protein to be monodisperse and stable, and the process must be optimized to account for the presence of detergents or other membrane mimetics [33] [34]. Understanding the kinetic and thermodynamic pathways of crystallization, for instance by constructing experimental phase diagrams, can provide a more rational approach to optimization [34].

Detergent and Membrane-Mimetic Screening

The selection of an appropriate solubilizing agent is arguably the most critical step in stabilizing a membrane protein for crystallography.

Conventional Detergents and Advanced Alternatives

Detergents function by forming micelles around the hydrophobic regions of the protein. The choice of detergent can make the difference between a well-diffracting crystal and a failed experiment. A summary of key agents is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Membrane-Mimetic Agents for Solubilization and Stabilization

| Agent Class | Examples | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Detergents | DDM, OG, LDAO [32] [33] | Well-established protocols; wide commercial availability. | Can destabilize proteins; may strip essential lipids. |

| Polymer-Based Native Nanodiscs | SMA, DIBMA [32] | Detergent-free extraction; preserves native lipid environment. | Sensitivity to divalent cations; polymer optimization may be needed. |

| Peptide-Based Native Nanodiscs | DeFrMSPs (e.g., 18A) [35] | Detergent-free reconstitution; high stability; suitable for cryo-EM. | Requires peptide engineering and screening for optimal performance. |

| Proteoliposomes | Lipid vesicles [32] | Provides a native-like lipid bilayer environment. | Low solubility, not ideal for most crystallization screens. |

| Bicelles | Lipid/detergent mixtures [32] | Planar bilayers can facilitate crystal contact formation. | Complex preparation and size optimization. |

High-Throughput Detergent Screening Protocol

Objective: To rapidly identify the optimal detergent and buffer condition for stabilizing a monodisperse membrane protein.

Materials:

- Purified membrane protein in starting detergent (e.g., DDM).

- Panel of detergents (e.g., DDM, LMNG, OG, LDAO, Cymal-6).

- GFP-fused protein construct (if applicable).

- Fluorescence Size-Exclusion Chromatography (FSEC) system.

- 96-well plate.

Method:

- Small-Scale Solubilization: If starting from membranes, aliquot membrane preparations into a 96-well plate. Add different detergents from the screening panel to each well at a concentration typically 1-2% (w/v). Incubate with gentle agitation for 1-2 hours at 4°C.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the plate at high speed (e.g., 100,000 x g) for 30 minutes to pellet insoluble material.

- FSEC Analysis: Load the supernatant from each well onto an SEC column coupled with a fluorescence detector (utilizing the intrinsic protein fluorescence or fluorescence from a GFP tag). The GFP fusion strategy allows for rapid, small-scale assessment of solubilization efficiency and monodispersity directly from the crude membrane extract [33].

- Data Interpretation: Analyze the resulting chromatograms. A single, sharp peak indicates a monodisperse protein sample, which is a positive sign for crystallization. Multiple peaks or significant aggregation (void volume peak) suggest poor stability in that detergent condition.

- Scale-Up and Purification: Scale up the top 2-3 detergent conditions identified by FSEC for large-scale purification. Perform standard affinity and size-exclusion chromatography in the selected detergent(s) for subsequent crystallization trials.

Specialized Crystallization Strategies

Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Crystallization

The Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) method has been particularly successful for solving structures of difficult MPs, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [33]. LCP provides a membrane-like environment by creating a continuous lipid bilayer, which mimics the native state of the protein and can lead to more physiologically relevant crystal structures.

Protocol: Objective: To crystallize a membrane protein using the LCP method.

Materials:

- Purified, monodisperse membrane protein in detergent.

- Monoolein or other suitable lipid.

- Two-syringe mixing setup or commercial LCP mixer.

- Automated LCP crystallography robot.

- Glass sandwich plates or LCP crystallization plates.

Method:

- LCP Reconstitution: Mix the purified protein solution with molten lipid (e.g., monoolein) using a two-syringe system. This involves combining equal volumes of protein and lipid in two syringes connected by a coupler and pushing the plungers back and forth repeatedly until a clear, viscous cubic phase is formed. The final protein concentration in LCP is typically 20-50 mg/mL.

- Plate Setup:

- Using an LCP robot or manual syringe dispenser, deposit ~50 nL boluses of the protein-laden LCP onto a glass sandwich plate or the well of an LCP crystallization plate.

- Overlay each bolus with ~1 µL of precipitant solution from a standard crystallization screen optimized for membranes (e.g., JCSG+ suite with additives).

- Seal the plate and store at a constant temperature (e.g., 20°C).

- Imaging and Harvesting: Monitor the plates regularly for crystal growth using a microscope with cross-polarizers. LCP crystals are often small and needle-like. Once crystals of suitable size are obtained, they can be harvested directly from the LCP bolus using special micromounts (e.g., MiTeGen MicroLoops) for X-ray data collection at a synchrotron source.

Detergent-Free Crystallization Using Native Nanodiscs

Technologies that bypass detergents altogether offer a promising path for studying particularly sensitive MPs. The DeFrND (Detergent-Free reconstitution into Native Nanodiscs) protocol uses engineered membrane-scaffolding peptides (DeFrMSPs) to directly extract MPs from native cell membranes, preserving the native lipid composition [35].

Protocol: Objective: To solubilize and stabilize a membrane protein in a native nanodisc for structural studies.

Materials:

- Cell membranes containing the target MP.

- Library of engineered DeFrMSPs (e.g., fatty-acid modified 18A peptides).

- Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) system.

- reagents for Negative-stain EM or Cryo-EM grid preparation.

Method:

- Extraction: Incubate isolated cell membranes with a selected DeFrMSP (e.g., at a 1:50 protein-to-peptide mass ratio) for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Clearing: Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 20,000 x g) for 30 minutes to remove insoluble debris.

- Purification: Load the supernatant onto an SEC column equilibrated with a suitable buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Collect the elution fractions.

- Validation: Analyze the peak fractions by negative-stain EM to confirm the formation of monodisperse, discoidal particles of ~10-20 nm diameter [35].

- Structural Analysis: The resulting MP-loaded native nanodiscs are now suitable for biophysical and functional assays. For structure determination, they can be directly applied to cryo-EM grids for single-particle analysis, often yielding high-resolution structures with native lipids bound [35].

Diagram 1: Membrane protein structure determination workflow, showing multiple parallel paths toward X-ray data collection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Membrane Protein Crystallization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Mild, non-ionic detergent for solubilization and stabilization. | Initial extraction and purification of many GPCRs and transporters. |

| Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) | Maltose-based detergent with high stabilizing properties. | Stabilization of challenging targets like cytokine receptors for crystallization. |

| Monoolein | Lipid forming the Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP). | Creating a membrane-mimetic matrix for in meso crystallization. |

| Styrene-Maleic Acid (SMA) Copolymer | Amphipathic polymer for detergent-free extraction. | Formation of SMALPs for stabilizing MPs with a native lipid annulus. |

| DeFrMSP Peptides (e.g., 18A) | Engineered membrane scaffold peptides. | Forming native nanodiscs via the DeFrND protocol for cryo-EM or crystallography. |

| GFP Fusion Construct | Reporter for FSEC-based stability screening. | Rapid, small-scale evaluation of detergent efficacy and protein monodispersity. |

The field of membrane protein structural biology is being transformed by synergistic advances in both traditional and disruptive technologies. While detergent-based protocols and the LCP crystallization method continue to yield high-value structures, new detergent-free approaches using polymers and designer peptides offer a powerful alternative for preserving the native membrane environment [32] [35]. The integration of high-throughput screening methods, such as FSEC, allows researchers to navigate the complex landscape of detergents and buffer conditions more efficiently than ever before. By applying the specialized protocols outlined in this document—from systematic detergent screening to advanced in meso and native nanodisc crystallization—researchers can overcome historical bottlenecks. This structured approach significantly enhances the probability of obtaining well-diffracting crystals, thereby accelerating the determination of membrane protein structures and empowering structure-based drug discovery for critical therapeutic targets.

In the field of protein structure determination, serial crystallography (SX) conducted at advanced light sources like synchrotrons and X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) has revolutionized structural biology. However, a significant challenge persists: the efficient use of precious macromolecular samples, which are often available in limited quantities [1]. Reducing sample consumption is thus critical for maximizing the potential of SX and expanding its application to a broader range of biologically significant samples, including membrane proteins and protein complexes [1] [36]. This application note examines the theoretical lower limits of sample consumption, compares the performance of current state-of-the-art sample delivery methods against this ideal, and provides detailed protocols for implementing low-consumption techniques. The focus is on practical strategies that enable researchers to obtain high-resolution structural data while conserving often invaluable protein samples.

Theoretical Limits of Sample Consumption

The theoretical minimum sample consumption for a serial crystallography experiment can be estimated based on fundamental physical and biochemical parameters. The primary goal is to collect a sufficient number of indexed diffraction patterns—typically around 10,000—to reconstruct a complete electron density map [1].

This calculation relies on several key assumptions:

- Each crystal hit by an X-ray pulse yields an indexable diffraction pattern.

- Microcrystals have a defined size; for this estimate, 4 × 4 × 4 μm is used.

- The protein concentration within the crystal is approximately 700 mg/mL, based on exemplary values from proteins like NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [1].

Theoretical Minimum Calculation:

- Volume per crystal = 4 μm × 4 μm × 4 μm = 64 μm³

- Volume per crystal in mL = 64 × 10⁻¹² mL

- Mass of protein per crystal = (64 × 10⁻¹² mL) × (700 mg/mL) = 44.8 pg

- Total protein mass for 10,000 crystals = 44.8 pg × 10,000 = 448,000 pg = ~450 ng

Therefore, under ideal conditions, the theoretical minimum amount of protein required to obtain a full dataset is approximately 450 nanograms [1]. This ideal scenario does not account for practical inefficiencies such as sample loss during preparation, crystals that fail to hit the beam, or crystals that do not yield indexable patterns, but it provides a crucial benchmark against which real-world methods can be evaluated.

Performance Comparison of Sample Delivery Methods

In practice, sample consumption varies significantly across different delivery methods. These approaches represent different strategies for presenting microcrystals to the X-ray beam, each with distinct advantages and limitations concerning sample consumption, data acquisition rate, and practical implementation. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary sample delivery systems used in serial crystallography.

Table 1: Comparison of Sample Delivery Methods in Serial Crystallography

| Delivery Method | Key Principle | Reported Sample Consumption | Relative Data Acquisition Rate | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection (Jets) | Continuous stream of crystal suspension flowing across the X-ray beam [1]. | High (Early SX experiments required grams of protein) [1] | High [1] | High data collection rate; suitable for time-resolved studies [1]. | High sample waste; requires large crystal volumes; can be complex to operate [1]. |

| Fixed-Target | Microcrystals deposited on a solid support (e.g., silicon nitride membrane) and scanned through the beam [1] [37]. | Ultra-low (~540 μg of protein to prepare a chip, with only a fraction consumed per dataset) [37] | Moderate (Up to 10 Hz demonstrated) [37] | Dramatically reduced sample consumption; precise control over irradiation; no continuous flow waste [1] [37]. | Requires sample immobilization; potential background scattering from support [1]. |