Advanced Seeding Techniques for Optimizing Crystal Size Distribution in Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to seeding techniques for controlling crystal size distribution (CSD) in pharmaceutical crystallization.

Advanced Seeding Techniques for Optimizing Crystal Size Distribution in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to seeding techniques for controlling crystal size distribution (CSD) in pharmaceutical crystallization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental role of seeding in suppressing nucleation and directing crystal growth. The scope spans from foundational principles and practical methodologies to advanced troubleshooting and validation strategies. It details the impact of critical seed parameters—including form, distribution, loading ratio, and policy—on final API quality, process robustness, and scalability, offering a science-based framework for achieving desired particulate products.

The Science of Seeding: Core Principles for Controlling Crystal Size

Theoretical Foundations of Seeding

Seeding is a critical technique in crystallization processes, used to suppress spontaneous nucleation and direct crystal growth towards a desired Crystal Size Distribution (CSD). The primary objective of seeding is to control the crystallization phase diagram by providing controlled initiation sites for crystal growth, thereby avoiding the unpredictable nature of primary nucleation [1].

Theoretical models indicate that the initial CSD is largely determined by the timing of crystal nucleation; crystals that nucleate first have the longest time to grow and attain the largest size [2]. Seeding addresses this by introducing a known quantity of seed crystals at a predetermined time, creating a more uniform starting point for crystal growth. This approach is particularly valuable for achieving narrow and uniform CSDs, which are essential in pharmaceutical applications where drug bioavailability depends on crystal size [2].

The growth rates of seeded crystals follow classical equations for diffusion-controlled and kinetically controlled growth mechanisms. Research demonstrates that closely spaced crystals grow at different rates depending on their spatial distribution. Crystals clustered together in "nests" experience localized depletion of solute concentration, resulting in smaller final sizes compared to separately growing crystals [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Seeding Efficacy

The effectiveness of seeding strategies can be evaluated through specific experimental parameters and their outcomes. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on irreversible growth inhibition in β-hematin crystals, a model system for investigating seeded crystallization.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Irreversible Growth Inhibition in β-Hematin Crystals

| Inhibitor/Treatment | Crystal Face | Inhibition Type | Key Experimental Parameters | Reference Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-ARS (Artemisinin metabolite) | {011} & {010} | Irreversible | 3-day exposure, 10-day drug-free growth | Length increments in pure solution after exposure (4 ± 1 μm) were shorter than control growth (8 ± 2 μm) [3]. |

| Pyronaridine (PY) | Length & Width | Irreversible | 10 μM inhibitor, 0.5 mM hematin | Inhibitor concentration at least 50-fold lower than solute concentration; permanent growth impediment via dislocation generation [3]. |

| Chloroquine (CQ) | Width | Irreversible | Bulk crystallization assay | Met both criteria for irreversible inhibition established in the study [3]. |

| Mefloquine (MQ) | Width | Partially Irreversible | Comparative growth increments | Met only one criterion for irreversibility, suggesting a lower degree of permanent inhibition [3]. |

| H-ART | {011} & {010} | Reversible | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Adsorbs at kinks but does not induce permanent growth suppression [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Seeding

Protocol for Assessing Irreversible Growth Inhibition

This protocol is adapted from studies on β-hematin crystals and can be generalized for evaluating seeding efficacy in other crystal systems [3].

Objective: To determine whether a seed crystal or growth inhibitor induces irreversible suppression of crystal growth.

Materials:

- Test Solutions: Saturated solutions of the target solute.

- Seed Crystals/Inhibitors: The seeding material or chemical inhibitor of interest.

- Growth Vessels: Suitable containers for crystal growth (e.g., multi-well plates).

- Analytical Instrument: Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) or optical microscope with image analysis capability.

Procedure:

- Initial Growth Phase: Place seed crystals into a solution containing the growth inhibitor. Maintain controlled conditions (e.g., temperature, agitation) for a set period (e.g., 3 days).

- Reference Preparation: Simultaneously, prepare two control groups:

- Control A (Pure Solution): Seeds grown in pure solute solution for the entire experiment.

- Control B (Continuous Inhibitor): Seeds grown in the presence of the inhibitor for the entire experiment.

- Transfer and Final Growth: After the initial growth phase, carefully transfer the test seeds and Control A seeds into fresh, inhibitor-free solutions. Transfer the Control B seeds into a fresh solution containing the inhibitor.

- Continued Incubation: Allow all crystals to grow for an additional, extended period (e.g., 10 days).

- Measurement and Analysis:

- Image the crystals (e.g., using SEM) at the end of the initial and final growth phases.

- Measure the incremental growth in dimensions (e.g., length, width) during the final growth period.

- Criterion for Irreversibility: Inhibition is deemed irreversible if the growth increment of the test seeds in inhibitor-free solution is (a) significantly shorter than that of Control A and (b) comparable to that of Control B [3].

General Workflow for Seeding Experiments

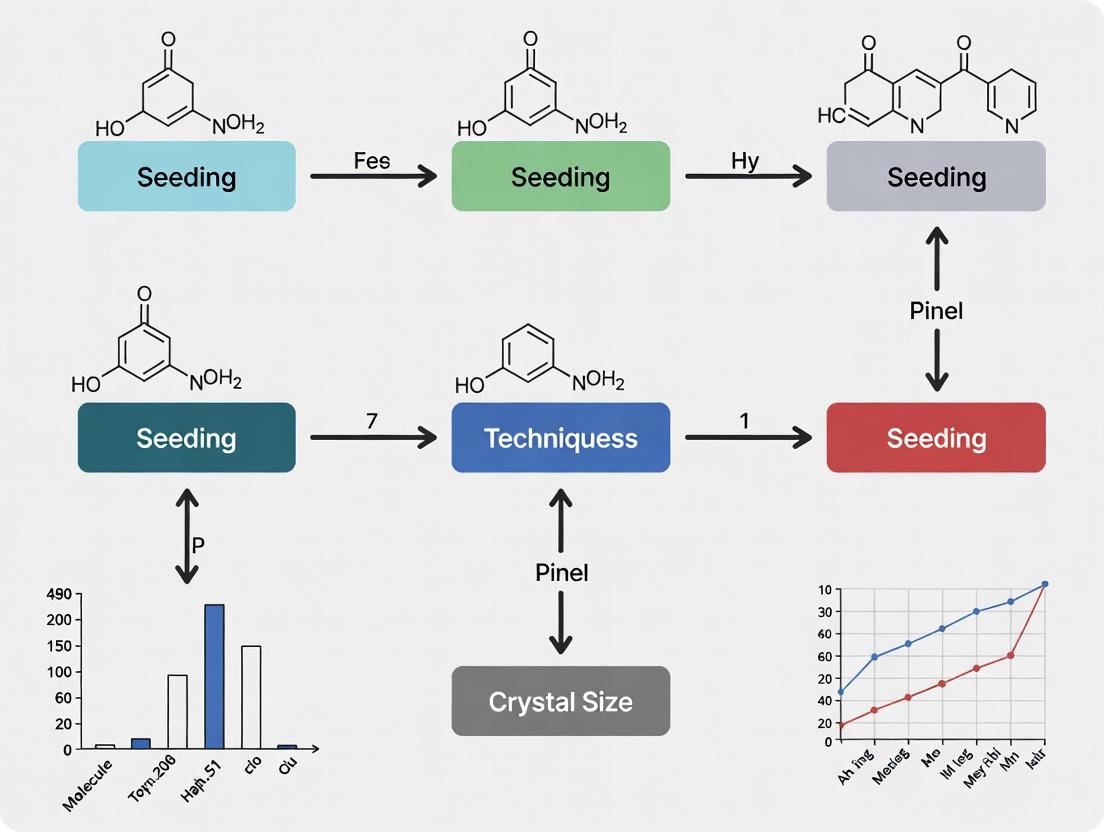

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing and executing a seeding experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in seeding experiments, as identified in the research.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Seeding Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Tools like ATR-FTIR and FBRM for monitoring solution concentration and CSD in real-time [2]. | Robust control of crystallization processes. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Resolves molecular-level mechanisms of inhibitor action on crystal surfaces [3]. | Studying irreversible inhibition and growth mechanisms. |

| β-Hematin Crystals | Synthetic analog of hemozoin; a model system for studying crystal growth inhibition [3]. | Investigating antimalarial drug mechanisms. |

| Citric Buffer-Saturated Octanol | Biomimetic solvent analog to the lipid sub-phase in parasite digestive vacuoles [3]. | Providing physiological relevance in model studies. |

| Quinoline-Class Antimalarials | e.g., Pyronaridine, Chloroquine; inhibit crystallization by step pinning or kink blocking [3]. | Model inhibitors for studying crystal growth suppression. |

In the development of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), crystallization is not merely a isolation step but a critical process that defines key product characteristics. Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) exerts a direct and profound influence on the efficiency of downstream purification, the success of formulation, and the ultimate therapeutic performance of the drug product [4] [5]. Particularly within the context of seeding techniques, a profound understanding of how CSD impacts these attributes is indispensable for robust process design and control. This Application Note delineates the multifaceted role of crystal size, supported by quantitative data, and provides detailed protocols for its characterization and control to aid researchers and drug development professionals.

The Impact of Crystal Size on Critical API Attributes

The size of API crystals is a critical quality attribute that impacts every stage of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) influences processability, stability, and biopharmaceutical performance, making its control a primary objective in process development.

Purification & Filterability: The efficiency of solid/liquid separation steps is highly dependent on crystal size. Small crystals can clog the pores of filters, leading to dramatically low filtration rates, potential product loss, and difficulties in subsequent washing and drying steps [2]. A uniform, larger crystal size, conversely, facilitates faster filtration, improves washing efficiency, and enhances overall process yield.

Bioavailability & Dissolution Rate: For many crystalline drugs, dissolution rate is the absorption rate-limiting step. The Noyes-Whitney theory establishes that smaller particles have a larger specific surface area, leading to a faster dissolution rate [6]. This can be crucial for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly soluble APIs. However, for Long-Acting Injectable (LAI) suspensions, larger particle sizes are employed to achieve a sustained-release profile over weeks or months [6] [7].

Product Stability & Performance: CSD affects the physical stability of the final drug product. A narrow and uniform CSD reduces the tendency of crystals to cake into solid lumps during storage and ensures consistent rheological properties in suspensions [2]. For LAI suspensions, particle size directly impacts syringeability, injectability, and sedimentation behavior [6].

Table 1: Key Impacts of Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) on API and Drug Product Attributes

| Attribute | Impact of Small Crystals | Impact of Large Crystals | Desired CSD Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filterability | Clog filter pores, slow filtration, difficult washing [2] | Faster filtration, easier washing [2] | Larger, uniform size |

| Dissolution Rate | High surface area leads to faster dissolution [6] | Lower surface area leads to slower dissolution [6] | Smaller for fast release; larger for sustained release |

| Bioavailability | Can enhance bioavailability of BCS Class II/IV drugs [6] | Can prolong release for sustained-action formulations [6] | Tailored to Target Product Profile |

| Product Stability | Increased caking, poor flowability [2] | Improved flow, reduced caking risk [2] | Narrow, uniform distribution |

| LAI Performance | Rapid release, potential stability issues [6] | Slow release, but risk of needle clogging [6] [2] | Optimized for release profile & injectability |

Quantitative Data from Case Studies

Data from industrial case studies underscore the profound impact that controlled crystallization, often achieved through seeding, has on final API quality. A model-driven crystallization process development for the API (3S,5R)-3-(aminomethyl)-5-methyl-octanoic acid (PD-299685) demonstrates the tangible outcomes of CSD control.

Table 2: Crystallization Process Optimization Case Study for PD-299685 [8]

| Process Parameter & Outcome | Initial/Mid-Process Result | Final Optimized Result |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent System | Varied solvent systems tested | 55:45 Water/1-Propanol |

| Antisolvent | Not applied | Water added |

| Crystal Size (d(v,90)) | 234 µm (small-scale) | 759 µm (production-scale) |

| Crystal Habit (Aspect Ratio) | 0.766 | 0.718 |

| Process Yield | Not specified | 99% |

The study utilized the Crystalline platform with Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring. The optimized, seeded crystallization in a water/1-propanol system followed by an antisolvent (water) addition resulted in a high yield and a significant increase in crystal size upon scale-up, producing crystals with properties ideal for pharmaceutical processing [8].

Experimental Protocols for CSD Analysis and Control

Protocol: Seeded Cooling Crystallization with PAT Monitoring

This protocol is adapted from an industrial case study on API crystallization [8].

- Objective: To produce an API with a target Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) and aspect ratio through a controlled, seeded cooling crystallization process.

Materials:

- API compound (e.g., PD-299685)

- Solvent system (e.g., 55:45 water/1-propanol)

- Antisolvent (e.g., deionized water)

- Pre-characterized seed crystals (size and polymorphic form)

- Crystallization reactor equipped with temperature control and agitation

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM) and/or Particle Vision Measurement (PVM) probes.

- Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) probe for concentration monitoring.

Procedure:

- Solubility Determination: Use the polythermal method in the Crystalline platform or similar setup to determine the API's solubility curve in the chosen solvent system [8].

- Solution Preparation: Charge the reactor with the solvent and API to create a saturated solution at a temperature 5-10°C above the saturation temperature.

- Supersaturation Generation: Cool the solution slowly to a temperature within the metastable zone to create a known level of supersaturation.

- Seeding: Introduce a predetermined amount of seed crystals (e.g., 0.5-2.0% w/w) of the target polymorph when the solution reaches the designated seeding temperature.

- Growth Phase: Execute a controlled cooling profile, typically linear or nonlinear, to maintain a constant supersaturation level, allowing for the growth of seeds. Monitor the process in real-time using FBRM (for chord length distribution) and PVM (for crystal habit).

- Antisolvent Addition (Optional): If applicable, after the growth phase, initiate a controlled addition of antisolvent to further reduce solubility and increase yield [8].

- Final Isolation: Cool the suspension to the final temperature, hold for a defined period, and then discharge for filtration and drying.

Protocol: Crystal Size and Habit Characterization

This protocol is based on standard practices for characterizing crystalline materials [9] [8].

- Objective: To quantitatively measure the Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) and aspect ratio of a final API batch.

Materials:

- Dry API powder from crystallization

- Static Image Analysis system (e.g., Morphologi series)

- Laser Diffraction Particle Size Analyzer (e.g., Malvern Mastersizer)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: For image analysis, ensure a representative sample is dispersed dry on a glass slide or in an inert solvent to minimize agglomeration.

- Image Analysis:

- Use static image analysis to capture images of thousands of particles.

- The software automatically identifies individual particles and measures multiple parameters, including particle diameter (e.g., based on equivalent circular area) and aspect ratio (width/length).

- Report the D(v,90) value (the size below which 90% of the particles reside) and the mean aspect ratio [8].

- Laser Diffraction:

- Disperse the sample in a suitable medium and circulate through the laser diffraction analyzer.

- This technique provides a volume-based size distribution and is excellent for detecting fines and tails in the distribution.

- SEM Imaging (for detailed morphology):

- Sputter-coat a small amount of powder with a conductive layer (e.g., gold).

- Image using SEM to obtain high-resolution images of crystal habit and surface features.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Crystallization Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Crystalline Platform (e.g., Crystalline) | An integrated workstation for automated, small-scale crystallization experiments with built-in PAT [8]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Tools like FBRM, PVM, and ATR-FTIR for real-time monitoring of CSD, crystal form, and solution concentration [8] [5]. |

| Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs) | Polysaccharide-based (cellulose/amylose) phases for chromatographic resolution of enantiomers during chiral analysis or purification [10]. |

| Chiral Resolving Agents | Agents like brucine or quinine used in salt-forming crystallization to separate racemic mixtures [10]. |

| Polyethylene Glycols (PEGs) | Polymers used in crystallization screens to induce macromolecular crowding and salting-out, promoting crystal formation [11]. |

Visualizing the Interplay of Crystal Size and API Properties

The following diagram illustrates the complex relationships between crystallization process parameters, the resulting crystal properties, and their ultimate impact on the API's critical quality attributes.

Diagram 1: The interrelationship between crystallization process parameters, crystal properties, and final API attributes is a complex but critical consideration for robust process design. Seeding strategy, cooling profiles, and solvent choice directly determine the Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) and habit, which in turn govern essential qualities like filterability, bioavailability, and stability [8] [4] [2].

The decision-making process for defining an optimal Crystal Size Distribution, especially for complex dosage forms like Long-Acting Injectables, requires a multidimensional analysis of competing factors.

Diagram 2: The multidimensional analysis required to determine the optimal particle size distribution (PSD) for a Long-Acting Injectable (LAI) suspension must balance competing factors related to pharmacokinetics (PK), product performance, and manufacturing [6]. The target PSD is a compromise that satisfies the requirements of the Target Product Profile.

In industrial crystallization, seeding is a critical technique used to directly control the Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) of the final product. By introducing carefully selected seed crystals into a supersaturated solution, the stochastic process of primary nucleation is bypassed, leading to a more reproducible and controllable growth process [12]. The quality attributes of crystalline products, including purity, shape, and CSD, are vital as they directly influence the efficacy of pharmaceuticals and the efficiency of downstream unit operations such as filtration, washing, and drying [13] [2]. Effective seeding stabilizes the batch crystallization process by providing a sufficient surface area for supersaturation to be consumed, thereby suppressing unwanted secondary nucleation and ensuring that the product crystals are predominantly the result of grown seeds [12]. The core parameters governing the success of this strategy are the form of the seeds, their distribution (both in size and spatially), and the loading ratio.

Key Seeding Parameters and Their Impact on CSD

Seed Form

The physical form of the seeds refers to their crystal habit, internal structure, and preparation method. This parameter is crucial as it determines the initial surface area available for growth and can influence the growth kinetics of the resulting crystals.

- Microseeds vs. Macroseeds: Seeding techniques are broadly categorized into microseeding and macroseeding. Microseeding involves crushing existing crystals into tiny fragments to create a stock of numerous, small nucleation sites [14]. This is particularly useful for promoting the growth of a large number of crystals. In contrast, macroseeding involves transferring a single, well-formed crystal to a fresh supersaturated solution to enlarge it further, a technique requiring careful handling to avoid crystal dissolution [14].

- Generic Cross-Seeding: A novel approach involves using seed crystals from a heterogeneous set of proteins unrelated to the target protein. This method leverages the diverse surfaces of these foreign crystal fragments to promote nucleation where conventional methods fail, acting as a generic nucleation agent [15].

- Seed Preparation: The preparation method defines the seed form. For microseeding, crystals can be fragmented using high-speed oscillation mixing or by vortexing with a seed bead to create a homogenized seed stock [15] [14]. The integrity and quality of these seeds are foundational to successful crystallization.

Seed Distribution

The distribution of seeds encompasses both the Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) of the seed population and their spatial distribution within the crystallizer. A uniform seed CSD is a primary determinant of a narrow product CSD.

- Impact of Initial CSD: The CSD of the seeds directly shapes the final product's CSD. A population of seeds with a narrow size distribution is more likely to yield a final product that is similarly mono-dispersed, which is critical for consistent drug bioavailability and processing efficiency [2].

- Spatial Distribution and "Nests": The spatial arrangement of crystals is often random, leading to clusters or "nests" where multiple crystals grow in close proximity. In these nests, crystals compete for the available solute, leading to localized depletion of supersaturation and consequently reduced growth rates compared to isolated crystals [2]. This uneven growth environment can cause an undesirable spread in the final CSD, even if the seeds were initially uniform.

- Growth Rate Dispersion (GRD): An additional complicating factor is GRD, where individual crystals of identical size and under identical conditions grow at different rates. This phenomenon, potentially linked to the surface integration step or dislocation structure, can further widen the CSD independently of the initial seed distribution [2].

Seed Loading Ratio

The seed loading ratio (or seed concentration) is defined as the mass of seeds added relative to the maximum theoretical yield of the batch. It is a decisive factor in controlling secondary nucleation and the final crystal size.

- Supersaturation Management: A fundamental role of seeding is to provide sufficient surface area to consume the generated supersaturation without triggering secondary nucleation. A high seed loading effectively keeps the supersaturation at a low level throughout the batch, creating a growth-dominated environment [12].

- Critical Seed Concentration ((Cs^*)): Experimental studies on potassium alum have demonstrated the existence of a critical seed concentration, (Cs^*). When the seed loading exceeds this threshold, the product CSD is consistently unimodal, comprising purely of grown seeds, regardless of the cooling mode applied [12]. This finding challenges the traditional belief that slow cooling is a necessary condition for suppressing secondary nucleation.

- Impact on Final Crystal Size: The seed loading has an inverse relationship with the final crystal size. Higher seed loadings divide the available solute mass among a greater number of crystals, resulting in a smaller overall size increase for each individual seed. Therefore, optimizing the seed load is essential for achieving a target final crystal size [12].

Table 1: Summary of Key Seeding Parameters and Their Effects

| Parameter | Definition | Impact on Crystallization Process | Desired Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Form | Physical nature and preparation of seeds (e.g., microseeds, macroseeds, cross-seeds) | Determines initial surface area and nucleation sites; influences growth kinetics. | A form that promotes controlled, reproducible growth of the desired crystal polymorph. |

| Seed Distribution | Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) and spatial uniformity of the seed population | A narrow initial CSD leads to a narrow final CSD; uneven spatial distribution can cause growth rate variations. | A uniform population of seeds evenly dispersed in the solution to minimize CSD spread. |

| Seed Loading Ratio | Mass of seeds added relative to the theoretical product yield | Controls supersaturation; high loadings suppress secondary nucleation but reduce final crystal size. | A loading above the critical concentration ((C_s^*)) to ensure a unimodal CSD of grown seeds. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 2: Experimental Data on Seed Loading Effects in Potassium Alum Crystallization [12]

| Seed Concentration, (C_s) (Ratio of seed to max yield) | Observed Product CSD | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| < Critical Concentration ((C_s^*)) | Bimodal | Presence of secondary nuclei (fines) alongside grown seeds. |

| > Critical Concentration ((C_s^*)) | Unimodal | Product consists solely of grown seeds; secondary nucleation is suppressed. |

| High Loading | Unimodal, smaller size | Maximizes surface area to consume supersaturation, resulting in a smaller size increase per seed. |

The optimization of seeding extends beyond loading to the formulation of the objective function in model-based control strategies. Research shows that the choice of objective function significantly impacts the resulting CSD [13]. For instance:

- Objective functions based on the volume density distribution and higher-order moments of the CSD tend to produce a late growth strategy, which effectively reduces the volume of nucleated crystals (fines) [13].

- Conversely, objective functions based on the number density distribution and lower-order moments promote an early growth strategy [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Purpose: To create a standardized seed stock from existing crystals for use in extensive microseeding experiments.

Materials:

- Donor crystals

- Seed bead (e.g., from Hampton Research Seed Bead Kit)

- Mother liquor or stabilizing solution (e.g., MORPHEUS screen solution [15])

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Vortex mixer

Procedure:

- Prepare Donor Crystals: Identify and harvest well-formed donor crystals from their growth drop.

- Create Seed Stock: Transfer the crystals along with a small volume (~10-50 µL) of their mother liquor or a compatible stabilizing solution into a microcentrifuge tube containing the seed bead.

- Fragment Crystals: Securely cap the tube and vortex it vigorously for 10-30 seconds. This process physically smashes the crystals into a suspension of microseeds.

- Dilute Stock: Prepare serial dilutions of the crude seed stock (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) using additional mother liquor. The optimal dilution must be determined empirically.

- Use in Experiments: Administer the diluted seed stock to new crystallization drops. A typical ratio is 0.5 µL of seed stock mixed with 2 µL of protein sample and 1.5 µL of crystallization solution [14].

Notes: Keep the seed stock on ice to prevent dissolution of the microseeds. The dilution factor allows control over the number of seeds delivered, with higher dilutions (fewer seeds) often leading to larger final crystals.

Purpose: To crystallize a target protein by using a heterogeneous mixture of crystal fragments from unrelated proteins as seeds.

Materials:

- Library of 12 or more unrelated, commercially available host proteins (e.g., α-Amylase, Albumin, Lysozyme)

- MORPHEUS or MORPHEUS-FUSION crystallization screen solutions

- Target protein sample

- High-speed oscillator for mixing

Procedure:

- Crystallize Host Proteins: Use the crystallization screen to grow crystals for each of the host proteins in the library.

- Characterize and Fragment: Characterize the host protein crystals for quality. Pool and fragment them using high-speed oscillation mixing to create a heterogeneous seed mixture.

- Set Up Cross-Seeding Trials: Add the generic cross-seeding mixture directly to the sample of the target protein before setting up crystallization trials.

- Screen for Growth: Proceed with standard crystallization experiments (e.g., vapor-diffusion sitting drops) using a broad screen of conditions.

- Identify Hits: Monitor the drops for crystal growth. Successful formation of the target protein's crystals indicates effective cross-seeding.

Notes: This method is highly non-specific and relies on the diversity of seed surfaces to initiate nucleation. The use of a stabilizing screen like MORPHEUS is recommended to maintain seed integrity [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Seeding Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Bead Kits | Standardized preparation of microseed stocks via mechanical fragmentation. | Hampton Research Seed Bead Kits [14]. |

| MORPHEUS Crystallization Screens | Pre-formulated screens providing a wide range of precipitant mixes, buffers, and additives to stabilize seeds and promote growth. | MORPHEUS and MORPHEUS-FUSION screens [15]. |

| Heterologous Protein Library | A set of unrelated proteins used to create a generic cross-seeding mixture for difficult-to-crystallize targets. | May include α-Amylase, Albumin, Catalase, Lysozyme, etc. [15]. |

| Microseeding Fibers | Used for streak seeding to transfer tiny crystal fragments from donor to acceptor drops. | Horse hair, cat whiskers, or specialized commercial fibers [14]. |

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and optimizing key seeding parameters to achieve a desired crystallization outcome.

Seeding Parameter Optimization Workflow

The Role of Secondary Nucleation in Seeded Crystallization Processes

In the pursuit of consistent crystal size distribution and solid-state form in pharmaceutical development, seeding has emerged as a critical control strategy. This technique fundamentally relies on the phenomenon of secondary nucleation, a process where existing seed crystals facilitate the formation of new crystalline entities. Within the context of a broader thesis on seeding techniques for improving crystal size research, understanding and controlling secondary nucleation is paramount, as it directly influences critical quality attributes including particle size distribution, polymorphism, and downstream processability [16] [17]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this phenomenon transforms crystallization from an unpredictable art into a controllable scientific process, enabling the production of materials with tailored physical properties essential for drug product performance.

Secondary Nucleation: Mechanisms and Kinetic Principles

Fundamental Concepts

Secondary nucleation is defined as a nucleation process that occurs only in the presence of crystals of the species under consideration [18]. This distinguishes it from primary nucleation, which happens spontaneously in a crystal-free solution. In industrial crystallizers, where crystals are invariably present, secondary nucleation exerts a profound influence on virtually all crystallization processes and is a dominant mechanism for new crystal generation [18]. The presence of seed crystals provides a templating surface that lowers the energy barrier for new crystal formation, allowing nucleation to occur at lower supersaturation levels than those required for primary nucleation.

The metastable zone width represents the critical concept domain where secondary nucleation occurs. This zone defines the supersaturation region between the solubility curve and the spontaneous nucleation boundary. Seeding within the metastable zone encourages controlled growth and secondary nucleation while avoiding uncontrolled primary nucleation events that lead to inconsistent product quality [16].

Predominant Mechanisms

Several mechanistic pathways have been identified through which secondary nucleation operates:

- Contact Nucleation: This is considered the most prevalent mechanism in agitated industrial crystallizers. It involves the generation of new nuclei through mechanical contacts between existing crystals and other surfaces, most notably agitators, crystallizer walls, or other crystals. The collision energy, rather than causing macroscopic crystal damage, generates microscopic fragments that serve as new growth centers [18].

- Shear Breeding: This mechanism occurs when fluid shear forces acting on a crystal surface detach molecular clusters or tiny crystalline particles that subsequently develop into new crystals. This process is enhanced at higher supersaturation levels where the crystal surface exhibits different morphological features [18].

- Initial Breeding: This involves the dislodging of microscopic crystals that have formed on the surface of larger crystals during drying processes. This mechanism is particularly relevant in seeded batch crystallizers where dried seed crystals are introduced into a supersaturated solution [18].

Kinetic Modeling

The kinetics of secondary nucleation are most commonly correlated using semi-empirical power-law relationships that account for the key process variables. A generalized rate expression is [18]:

[ B = Kb \rhom^j N^l \Delta c^b ]

Where:

- (B) is the secondary nucleation rate (number of new nuclei/volume·time)

- (K_b) is the birthrate constant

- (\rho_m) is the magma density (mass of crystals/volume of slurry)

- (N) is the agitation intensity (e.g., impeller rotational speed)

- (\Delta c) is the supersaturation

- (j), (l), and (b) are empirically determined exponents

These models demonstrate that nucleation rate increases with increasing magma density, agitation intensity, and supersaturation. The quantitative understanding of these relationships enables researchers to design crystallization processes that either enhance or suppress secondary nucleation based on the desired outcome.

Experimental Protocols for Secondary Nucleation Study

Workflow for Determining Secondary Nucleation Threshold

The following workflow, implementable on platforms such as the Crystalline system, enables systematic study of secondary nucleation kinetics [16].

Figure 1. Experimental workflow for secondary nucleation study.

Protocol Details:

- Determine Metastable Zone Width (MSZW): Generate solubility and metastable curves using transmissivity data to define the crystallization operating window. The metastable zone represents the region between the solubility curve and the spontaneous nucleation boundary where controlled secondary nucleation can occur [16].

- Select Supersaturation Levels: Choose multiple supersaturation levels sufficiently close to the solubility curve to avoid spontaneous primary nucleation while allowing measurable secondary nucleation. This ensures that any observed nucleation events can be confidently attributed to secondary mechanisms [16].

- Calibrate Particle Detection: Calibrate the imaging system using polystyrene microspheres of known size to establish a correlation between particle count on screen and actual suspension density. This quantitative calibration is essential for accurate nucleation rate measurements [16].

- Generate and Characterize Single Crystals: Produce well-defined parent crystals and characterize their size and morphology using techniques such as laser diffraction and scanning electron microscopy. Crystal size has been demonstrated to significantly impact secondary nucleation rates, with larger crystals generating more secondary nuclei [16].

- Conduct Seeded Experiment: Introduce a single characterized seed crystal into a clear, supersaturated, and agitated solution maintained at constant temperature. The solution must be maintained within the metastable zone throughout the experiment [16].

- Monitor Suspension Density and Analyze Data: Track the increase in particle count over time following seed introduction. The delay time between seed addition and suspension density increase provides quantitative data for calculating secondary nucleation rates [16].

Quantitative Analysis of Secondary Nucleation

The experimental approach above enables researchers to determine secondary nucleation thresholds and quantify kinetics. In a cited study using Isonicotinamide in ethanol, the seeded experiment showed a suspension density increase just 6 minutes after a single seed crystal was introduced, compared to 75 minutes in an unseeded control, confirming the dominant role of secondary nucleation in seeded crystallizations [16].

Quantitative Design and Impact of Process Parameters

Effect of Seed Characteristics and Process Conditions

Experimental investigations, particularly in model systems like KNO₃–H₂O, have quantified the impact of key parameters on secondary nucleation and crystal growth kinetics. The data below summarizes findings from systematic kinetic analysis [19].

Table 1. Impact of Seed Load and Process Parameters on Crystallization Kinetics and Product Properties

| Parameter | Impact on Nucleation | Impact on Crystal Growth | Effect on Product Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Seed Load | Nucleation capacity decreases | Growth capacity increases; Linear growth rate of single crystal reduces | More uniform size distribution; Reduced mean crystal size [19] |

| Larger Seed Size | Generates more secondary nuclei due to greater contact surface area | Provides larger surface for deposition | Impacts final particle size distribution; Faster secondary nucleation [18] [16] |

| Higher Supersaturation | Increases nucleation rate | May increase growth rate but risks instability | Promotes nucleation over growth; Risk of excessive fines [18] |

| Increased Agitation | Enhances contact nucleation through crystal-impeller collisions | Improves mass transfer but may cause attrition | Can broaden size distribution through fragmentation [18] |

Quantitative Seed Load Design

Kinetic studies demonstrate that with increasing seed load, the nucleation capacity decreases while the growth capacity increases, resulting in more uniform crystal size distributions. However, this occurs at the expense of reduced linear growth rates and smaller mean product size [19]. This trade-off necessitates careful optimization based on target product specifications.

Based on kinetic analysis, a quantitative design scheme for seed loading can be implemented. The foundation of this approach involves determining the relationship between seed mass, available surface area, and the resulting supersaturation decay profile to achieve the desired balance between growth and nucleation [19].

Application Notes: Protocol for Seeded Crystallization

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2. Essential Materials for Seeded Crystallization Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Seed Crystals | Template for growth and source of secondary nuclei; controls solid form | Well-defined polymorphic form; specific size distribution; high purity [17] |

| Appropriate Solvent System | Medium for dissolution and crystallization | Purity; appropriate solubility profile for target compound; chemical compatibility [17] |

| Stabilized Seed Slurry | Vehicle for homogeneous seed introduction | Dispersion quality; solvent composition; seed viability during storage [17] |

| Crystallization Vessel with Agitation | Environment for controlled crystallization | Well-mixed to ensure uniform supersaturation; controlled temperature profile [19] |

Detailed Seeding Protocol

The following protocol provides a systematic approach for implementing seeded crystallization with control over secondary nucleation, based on industry best practices [17].

Figure 2. Seeded crystallization protocol workflow.

Protocol Steps:

Seed Source Selection and Characterization:

- Select appropriate seed source based on target attributes: "as-is" batch for polymorph control, or sieved/micronized fractions for particle size distribution control [17].

- Thoroughly characterize seeds using a battery of analytical techniques (e.g., XRD, DSC, laser diffraction, SEM) to confirm polymorphic purity, size distribution, and morphology [17].

- Avoid "daughter seeding" (using seeds from previous batches) when polymorphic purity is critical, due to risk of progressive contamination with undesired forms [17].

Seed Slurry Preparation:

- Prepare a well-dispersed seed slurry in a compatible solvent to ensure homogeneous introduction. The slurry vehicle should not dissolve or otherwise alter the seed crystals [17].

- Characterize the slurry after preparation to confirm that seed properties remain unchanged, particularly regarding particle size and polymorphic form [17].

Process Design and Seed Addition:

- Determine the solubility curve and metastable zone width for the system to identify the appropriate operating window [17].

- Identify the optimal seed addition point, typically in the metastable zone (a common rule of thumb is approximately one-third into the zone) where supersaturation is sufficient to drive growth but low enough to minimize primary nucleation [17].

- Introduce the seed slurry into a well-mixed region of the crystallizer to ensure uniform distribution. Computational fluid dynamics modeling may be beneficial for identifying optimal addition points at large scale [17].

Post-Seeding Process Control:

- Carefully control the cooling or antisolvent addition profile following seeding to maintain moderate supersaturation levels, maximizing seed crystal growth while minimizing both primary and excessive secondary nucleation [17] [19].

- Monitor the process using in-situ tools (e.g., FBRM, PVM, or transmissivity measurements) to track crystal growth and detect unintended nucleation events [16].

- Optimize agitation intensity to maintain suspension while minimizing crystal attrition and shear-induced secondary nucleation [18].

Secondary nucleation represents a pivotal phenomenon in seeded crystallization processes, directly determining critical particle attributes in pharmaceutical development. Through mechanistic understanding and controlled experimental protocols, researchers can harness this process to consistently produce materials with target properties. The quantitative relationships between seed characteristics, process parameters, and nucleation kinetics provide a scientific foundation for rational process design. When implemented via robust seeding protocols that include careful seed characterization, precise addition within the metastable zone, and controlled growth trajectories, management of secondary nucleation becomes a powerful strategy in the broader context of crystal size research. This approach enables the transition from empirical observations to predictive control, ultimately enhancing drug product development and manufacturing robustness.

Implementing Seeding Protocols: From Laboratory to Pilot Scale

In the pursuit of obtaining high-quality crystals for research and drug development, the characteristics of the seed material used to initiate crystallization are paramount. The modality of a distribution—that is, the number of peaks in its size or frequency profile—serves as a critical indicator of seed population characteristics. A unimodal distribution displays a single, clearly visible peak, representing one most frequent value or central tendency within the dataset [20] [21]. This single-peak pattern indicates a homogeneous population where particles cluster around a dominant size range. In contrast, a bimodal distribution features two distinct peaks separated by a valley, with each peak representing a local maximum in data frequency [20] [21]. This dual-peak signature reveals the presence of two heterogeneous subgroups or distinct populations within the seed material, a factor that profoundly influences crystallization outcomes.

Understanding these distribution patterns is fundamental for researchers aiming to control crystal size, morphology, and ultimately, the success of structural analysis and pharmaceutical development. The selection of appropriately distributed seed material enables scientists to bypass the challenging kinetic barrier of spontaneous nucleation, instead leveraging pre-formed crystalline matter to direct and control the growth process [22]. Within the broader thesis on seeding techniques for improving crystal size research, this application note establishes how deliberate selection based on distribution modality provides a powerful strategy for achieving precise crystallographic outcomes.

Comparative Analysis: Unimodal vs. Bimodal Seed Distributions

The choice between unimodal and bimodal seed distributions carries distinct implications for crystallization processes, each offering different advantages and challenges. The following table summarizes the core characteristics, mechanisms, and optimal applications for these two distribution types.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Unimodal and Bimodal Seed Distributions

| Characteristic | Unimodal Distribution | Bimodal Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Structure | Single clear central peak [20] | Two distinct high points separated by a valley [20] |

| Population Homogeneity | Single, homogeneous population [21] | Mixed or multiple sub-populations [21] |

| Statistical Central Tendency | One clear center (mean, median, mode potentially aligned) [21] | Two local centers, making central tendency measures ambiguous [21] |

| Crystallization Mechanism | Templated growth from uniform nuclei; predictable growth kinetics [17] | Complex growth from disparate nuclei sizes; potential for differentiated growth rates [23] |

| Primary Applications | Control of solid-state form; reproducible particle size distribution [17] | Studies of asymmetric competition; systems requiring multiple nucleation sites [23] |

| Key Advantages | Simpler statistical analysis; consistent growth behavior; uniform supersaturation consumption [17] [24] | Can exploit different growth behaviors simultaneously; may fill more available space [23] |

The decision framework for selecting seed distribution type involves evaluating research goals against these characteristics. Unimodal seeds are generally preferred when the objective is precise control over the solid-state form or a narrow, reproducible Particle Size Distribution (PSD) without subsequent milling [17]. The homogeneous nature of unimodal seeds promotes consistent growth kinetics and predictable supersaturation consumption across the crystal population. Conversely, bimodal seeds may be beneficial in more fundamental studies investigating asymmetric competition or in systems where multiple nucleation site sizes are advantageous, though they introduce complexity in controlling the final crystal population [23].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Outcomes

Experimental data reveals how seed loading and cooling rates interact with distribution modality to determine final crystal attributes. Research on protein crystallization demonstrates that seed loading (the mass ratio of seed crystals to the theoretical yield of crystals) significantly impacts supersaturation and final crystal morphology [24].

Table 2: Effect of Seed Loading and Cooling Rate on Crystal Properties

| Experimental Parameter | Condition | Impact on Supersaturation | Impact on Crystal Size & Shape |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Loading | Low | Higher supersaturation peak [24] | Larger crystals with lower aspect ratio [24] |

| Seed Loading | High | Lower supersaturation, reduces nucleation risk [24] | Smaller, more uniform crystals [24] |

| Cooling Rate | Large (e.g., fast linear cooling) | -- | Larger crystals with smaller aspect ratio [24] |

| Cooling Rate | Small (e.g., slow linear cooling) | -- | Smaller crystals with larger aspect ratio [24] |

Lower seed loading leads to the development of larger crystals but at the cost of higher supersaturation, which risks spontaneous nucleation [24]. This phenomenon holds true regardless of distribution modality but is more challenging to control in bimodal systems where the two sub-populations may consume supersaturation at different rates. Furthermore, the cooling rate during crystallization interacts with seed characteristics. A larger cooling rate can result in larger crystals with a smaller aspect ratio, while a slower cooling rate tends to produce smaller crystals with a larger aspect ratio [24]. These quantitative relationships provide a guideline for fine-tuning crystallization processes once the seed distribution modality has been selected.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating and Characterizing Seed Distributions

Objective: To prepare and characterize seed crystals with controlled unimodal or bimodal size distributions.

Materials:

- Purified target molecule (e.g., protein, pharmaceutical compound)

- Precipitant solutions

- Solvents for slurry creation

- Laser diffraction particle size analyzer or similar instrument

- Ultrasonic bath for dispersion

- Analytical software for statistical modality testing (e.g., R packages

diptest,LaplacesDemon)

Method:

- Initial Crystallization: Generate initial seed crystals via standard vapor diffusion or batch crystallization methods [22].

- Seed Harvesting: Harvest crystals from the initial drop and separate them from the mother liquor.

- Seed Preparation:

- For unimodal seeds: Gently crush the crystals and either sieve to obtain a specific size fraction or use milling/micronization for size reduction [17].

- For bimodal seeds: Intentionally mix two distinct, size-controlled populations obtained from separate sieving steps or different crystallization conditions.

- Slurry Formation: Prepare a seed slurry by suspending the size-classified crystals in a solvent that prevents dissolution [17]. Use brief ultrasonic pulses to ensure a homogeneous, well-dispersed suspension.

- Characterization and Testing:

- Determine the Particle Size Distribution (PSD) using laser diffraction.

- Confirm modality statistically. In R, use

dip.test()from thediptestpackage for Hartigan's dip test (null hypothesis: unimodality). A p-value < 0.05 suggests multimodality [25]. Alternatively, useis.unimodal()oris.bimodal()from theLaplacesDemonpackage [25]. - For bimodal distributions, use the

cutoffpackage to fit a mixture model and determine the parameters (mean, standard deviation) of each underlying normal distribution, as well as the cutoff value separating the two modes [25]. - Characterize the solid-state form of the seeds using techniques like XRPD to ensure phase purity [17].

Protocol 2: Seeded Crystallization for Size Control

Objective: To utilize characterized seed materials in a controlled cooling crystallization to achieve a desired crystal size distribution.

Materials:

- Well-characterized seed slurry (unimodal or bimodal)

- Supersaturated solution of the target compound

- Controlled-temperature crystallizer with agitation

- Lasentec FBRM or similar in-situ particle monitoring tool

Method:

- Process Development: Determine the solubility curve and metastable zone width (MSZW) for the compound-solvent system [17].

- Seed Introduction:

- Bring the supersaturated solution to a temperature within the metastable zone, typically aiming for a point about one-third into the zone to provide a sufficient driving force for growth while minimizing the risk of spontaneous nucleation [17].

- Introduce the well-dispersed seed slurry into the crystallizer at a homogeneous region with good mixing to ensure even distribution [17].

- Crystal Growth:

- Implement a controlled cooling profile (e.g., linear cooling) based on prior optimization [24]. The trajectory should be designed to gradually consume supersaturation, maximizing growth on the seed crystals while avoiding secondary nucleation.

- Use in-situ monitoring to track the evolution of the crystal population.

- Harvest and Analysis:

- Harvest the final crystals at the predetermined terminal temperature.

- Wash and dry the product as needed.

- Characterize the final product's PSD, shape, and solid-state form against the target specifications.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Seed Selection and Crystallization Decision Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Controlled Seeded Crystallization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of seeding strategies requires specific materials and analytical tools. The following table details key reagent solutions and their functions in seed preparation and characterization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Seed Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Slurry Solvent | A solvent that prevents seed dissolution, often a mixture of mother liquor and antisolvent [17]. | Used to create a homogeneous, transferable suspension of seed crystals. Slurrying should be studied for potential physical changes to seeds [17]. |

| Size Classification Kit | Set of micro-sieves or equipment for milling/micronization [17]. | Critical for obtaining a unimodal seed PSD or for creating a defined bimodal distribution by mixing specific fractions. |

| Modality Analysis Software | Statistical packages (e.g., R with diptest, LaplacesDemon, cutoff) [25]. |

Used to quantitatively confirm unimodality/bimodality (Hartigan's dip test) and, for bimodal data, to determine the parameters of the underlying distributions [25]. |

| In-situ Particle Analyzer | Probe-based instrument (e.g., FBRM, PVM) for monitoring crystallization in real-time. | Tracks the evolution of crystal size and count, allowing for dynamic adjustment of the cooling profile to favor growth over nucleation. |

| Stable Seed Stock | A well-characterized batch of seeds used for multiple experiments [17]. | Ensures consistency across seeding experiments. Requires a defined shelf life supported by stability data showing the seeds remain functionally effective over time [17]. |

| Protein Crystallization Reagents | Precipitants (e.g., PEGs, salts), buffers, and additives for generating initial seeds [22]. | The quality of the final seeded crystal is contingent on the purity of the protein solution and the optimization of these reagent concentrations [22]. |

In the pursuit of consistent and desirable crystal products, the strategic use of seed crystals is a cornerstone of modern crystallization process optimization. The deliberate introduction of seeds into a supersaturated solution provides a template for crystal growth, bypassing the stochastic nature of primary nucleation and offering greater control over the final crystal size distribution (CSD). This application note details rigorous methodologies for quantifying the critical seed parameters—seed loading (the mass of seeds added) and critical seed mass (the minimum mass required to suppress excessive nucleation)—that are fundamental to achieving a growth-dominant process with a uniform CSD. Framed within a broader thesis on advancing seeding techniques for crystal size research, this guide provides drug development professionals with standardized protocols to enhance process reliability and product quality in pharmaceutical crystallization.

The Critical Role of Seed Parameters in Crystallization

The practice of seeded crystallization is employed to directly control the final CSD, a critical quality attribute for many drug substances. The underlying principle is to add a predetermined quantity of seed crystals with known characteristics to a supersaturated solution. This approach facilitates growth on existing crystals, thereby minimizing the spontaneous formation of new crystals (primary nucleation) and the generation of excessive fine particles.

- Optimal Seed Loading: Seed loading refers to the mass of seed crystals introduced relative to the mass of the final product or the solution. An optimal seed loading is a delicate balance; insufficient seed mass can lead to a high degree of secondary nucleation, resulting in a wide, bimodal CSD with many fine crystals. Conversely, excessive seed mass may lead to an overly large surface area for growth, potentially depleting the supersaturation too quickly and resulting in a final product with an excessively small and uniform, but potentially undesirable, crystal size [26].

- Critical Seed Mass: This is the threshold of seed loading required to effectively dominate the crystallization process. When the seed mass is above this critical value, crystal growth on the added seeds is the predominant mechanism, effectively suppressing significant nucleation of new crystals. Research has demonstrated that sufficient seed loading ensures a growth-dominated process with negligible fines, while insufficient loading promotes significant formation of fines, leading to an unpredictable and often undesirable CSD [26].

The quantitative relationship between seed parameters and final crystal properties is a key area of study. Investigations have shown that product CSD can change by an order of magnitude with a change in seed distribution. Furthermore, any slight changes in seed crystal size distribution, such as a wide seed CSD, can render the desired final CSD unattainable [26]. The form of the seeds, including their distribution and shape, are therefore critical input parameters for the process [26].

Table 1: Key Seed Parameters and Their Impact on Final Crystal Product

| Parameter | Definition | Impact on Crystallization Process & Final CSD |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Loading | The mass of seed crystals added to the crystallizer. | Insufficient loading promotes secondary nucleation (fines); excessive loading may result in overly small crystals. |

| Critical Seed Mass | The minimum seed mass required to suppress excessive secondary nucleation. | Ensures a growth-dominated process, leading to a more predictable and unimodal CSD. |

| Seed Distribution (CSD) | The particle size distribution of the seed crystals themselves. | A narrow seed CSD is often critical for achieving a narrow, desired final CSD. A wide or bimodal seed CSD can make the target CSD unattainable [26]. |

| Seed Shape | The morphology of the seed crystals. | Influences growth rates and can affect the final crystal habit and purity. |

Quantitative Analysis of Seed Parameter Effects

A systematic approach to seeding requires an understanding of the quantitative effects of seed parameters. Experimental and simulation studies have provided valuable insights into these relationships.

For instance, research on potash alum crystallization has analyzed the impact of different seed crystals, varying in distribution and shape, on the final CSD. The experiments utilized seed profiles with different standard deviations (σ) and modalities. The results demonstrated that seed profiles with a unimodal distribution and a lower standard deviation (e.g., σ = 0.29) yielded a more optimal final CSD with a higher mean crystal size compared to seeds with a wider distribution (σ = 0.35) or a bimodal distribution [26]. This underscores the importance of not only the mass but also the quality and consistency of the seeds used.

Table 2: Experimental Analysis of Seed Distribution Impact on Final Crystal Size (Potash Alum Case Study) [26]

| Seed Profile | Distribution Type | Standard Deviation (σ) | Impact on Final Crystal Size Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sieved Seed 1 | Unimodal | 0.35 | Wider final CSD, less control over crystal size. |

| Sieved Seed 2 | Unimodal | 0.29 | Superior final CSD with higher mean crystal size; more narrow distribution. |

| Sieved Seed 3 | Bimodal | 0.36 | Altered and less desirable final CSD; demonstrates challenge of using disperse seeds. |

The optimization of seed parameters can be a more effective process control strategy than optimizing the supersaturation profile alone. One study concluded that optimizing seed distribution was better compared to optimizing supersaturation profile for maximizing the mean crystal size of the product [26].

Experimental Protocols for Determining Seed Parameters

Protocol for Determining Critical Seed Mass and Optimal Loading

This protocol outlines a laboratory-scale procedure to empirically determine the critical seed mass and optimal seed loading for a given system.

I. Principle A series of parallel batch crystallization experiments are conducted with varying seed loadings. The resulting crystal size distributions are analyzed to identify the point at which increased seed mass no longer significantly reduces the nucleation of fines, indicating the threshold of critical seed mass and the zone of optimal loading.

II. Materials and Equipment

- Jacketed crystallizer

- Temperature control unit (e.g., programmable water bath)

- Overhead stirrer

- Laser diffraction particle size analyzer (e.g., Malvern Mastersizer) or imaging system for CSD measurement

- Vacuum filtration setup

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.1 mg)

- Seeds of known size distribution and morphology (see Protocol 4.2)

- API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) and solvent system

III. Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a saturated solution of the compound in the chosen solvent at an elevated temperature (e.g., 10-15°C above the saturation temperature at the growth temperature).

- Seed Preparation: Characterize the seed crystals for their size distribution and shape (see Protocol 4.2). Calculate the required masses for a series of seed loadings (e.g., 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5% w/w relative to the theoretical final crystal mass).

- Experimental Setup: a. Transfer a known volume of the saturated solution to the jacketed crystallizer. b. Initiate cooling to a predetermined growth temperature while applying consistent agitation. c. Once the growth temperature is stable, add the pre-weighed seed crystals to the solution.

- Crystallization Run: Follow a defined cooling profile (e.g., linear or cubic cooling). Monitor the process in situ if possible.

- Product Analysis: At the end of the cycle, isolate the crystals by filtration, dry them, and measure the final CSD.

- Data Analysis: Plot the final mean crystal size (or the proportion of fines) against the seed loading. The critical seed mass is identified as the point where the curve inflects, and further increases in seed mass yield diminishing returns in increasing crystal size. The optimal loading is selected within this plateau region based on process economics and desired product attributes.

Protocol for Seed Stock Generation and Characterization via rMMS

Random Microseed Matrix Screening (rMMS) is a high-throughput technique for generating and utilizing seed stocks, which can be directly applied to seeding optimization studies [27].

I. Principle Existing crystalline material, even microcrystals or poor-quality crystals, is harvested and systematically crushed to create a heterogeneous stock of microscopic seeds. This seed stock can then be used to inoculate a wide array of crystallization conditions.

II. Materials

- Source crystals (e.g., from initial crystallization hits)

- Seed Bead (e.g., a glass or metal bead for homogenization)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or a "neutral" precipitant like PEG 3000 for suspension

- Glass probe (made from a Pasteur pipette)

- 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes

- Liquid handling robotics (optional, for high-throughput application)

III. Procedure

- Harvest Crystals: Select wells or batches containing crystalline material. Place a microcentrifuge tube containing a Seed Bead on ice and add 50 µL of the corresponding reservoir solution.

- Crush Crystals: Using a flame-polished glass probe, thoroughly crush all crystalline material in the source well or on the coverslip. View under a microscope to ensure complete crushing.

- Suspend Seeds: Using a pipette, add 5 µL of the reservoir solution from the Seed Bead tube to the crushed material and resuspend thoroughly. Transfer the suspension back to the Seed Bead tube. Repeat this washing step 2-3 times to harvest maximum material.

- Homogenize: Vortex the Seed Bead tube for two minutes, pausing every 30 seconds to cool the tube on ice. This creates the primary seed stock.

- Dilution Series: Create a serial dilution of the seed stock (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) using reservoir solution or a neutral precipitant. The optimal dilution for generating a manageable number of crystals per drop must be determined empirically.

- Application: Use this seed stock, or its dilutions, to set up new crystallization trials by adding a small volume (e.g., 0.1-0.5 µL) to each drop in a screen.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Seeding Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral Precipitant | Liquid medium for creating seed stock suspensions. | PEG 3000 solution. Helps avoid phase separation and encourages novel crystal contacts, unlike high-salt solutions [27]. |

| Seed Bead | Homogenization aid for creating microseed stocks. | A single glass or metal bead added to a microtube to assist in crushing and dispersing crystals during vortexing [27]. |

| Glass Probe | Tool for manually crushing crystalline material. | Hand-made from a Pasteur pipette, with a rounded end of ~0.75 mm diameter, used to crush crystals directly in the crystallization plate [27]. |

| Dilution Solvents | For creating seed stock dilution series to optimize crystal number. | Reservoir solution or a neutral buffer. Used in combinatorial microseeding to find the optimal seed density [27]. |

| AgI-containing Particles | Model seeding particle for glaciogenic cloud seeding, analogous to crystal seeding studies. | Used in field experiments (e.g., CLOUDLAB project) to quantify ice-nucleated fractions, a concept analogous to measuring seeding effectiveness in crystallization [28]. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Determination of Critical Seed Mass

Seed Parameter Impact Logic

Seeding is a foundational technique in crystal engineering used to control the crystallization process, ensuring the production of crystals with desired characteristics such as specific size, habit, and phase purity. Within the broader context of advancing crystal size research, the strategic use of single crystal seeds moves beyond simple nucleation induction to enable precise command over the critical early stages of crystal growth. This protocol is designed for researchers and drug development professionals who require robust, reproducible methods to improve crystal size distribution and overall product quality in both small-molecule pharmaceuticals and advanced materials. The controlled introduction of a pre-formed seed crystal bypasses the stochastic nature of primary nucleation, promoting growth in a metastable solution and resulting in larger, more uniform single crystals ideal for subsequent analysis and application [29] [30].

Quantitative Data on Seeding Outcomes

The impact of seeding on final crystal properties is substantial and quantifiable. The table below summarizes key findings from recent research, highlighting how seeding influences critical parameters such as aspect ratio and crystal size distribution, which in turn affect downstream processing efficiency.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Seeding on Crystal Properties

| Compound/System | Crystallization Method | Key Seeding Parameter | Outcome on Crystal Size/Shape | Downstream Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Glutamic Acid [30] | Cooling Crystallization | Seeding under slow cooling & low supersaturation (α-form seeds) | Achieved an average aspect ratio of 1.25 and an average particle diameter of 416 μm. | Mother liquor content of 5.60%; complete drying in ~120 minutes. |

| L-Glutamic Acid [30] | Cooling Crystallization (Unseeded) | Spontaneous nucleation | Resulted in an average aspect ratio of 16.40 and an average particle diameter of 170 μm. | Mother liquor content of 25.21%; complete drying required ~240 minutes. |

| GTAGG:Ce [31] | Czochralski Method | Use of a <100> oriented GAGG:Ce seed crystal; Pulling rate: 0.7 mm/h; Rotation rate: 10 rpm. | Successful growth of a transparent, 1-inch diameter, high-quality single crystal. | Suitable for high-performance scintillators in sub-micron resolution X-ray imaging. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Seeded Cooling Crystallization for Improved Aspect Ratio

This protocol, optimized for compounds like L-glutamic acid, is designed to enhance crystal habit and reduce the mother liquor content, thereby improving downstream drying efficiency [30].

Step 1: Seed Crystal Preparation and Selection

- Identification: First, identify the desired polymorphic form (e.g., α-form of L-glutamic acid) through preliminary unseeded crystallization trials and characterization via techniques like Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) or Raman spectroscopy.

- Preparation: Grow a batch of the target polymorph under controlled conditions. Gently grind the crystals and sieve them to obtain a narrow size fraction (e.g., 50-100 μm). The seeds should be of high purity and stored properly to prevent contamination or phase transition.

Step 2: Solution Preparation and Saturation

- Prepare a saturated solution of the compound in an appropriate solvent at an elevated temperature (e.g., 45-50°C for L-glutamic acid).

- Confirm Saturation: Ensure all solute is dissolved and the solution is clear. Filter the hot solution through a 0.2 μm membrane filter to remove any particulate matter or unintended microscopic nuclei.

Step 3: Generating a Metastable Zone and Seeding

- Cool the clear, saturated solution slowly to a temperature within the metastable zone (typically 5-10°C above the spontaneous nucleation temperature).

- Introduce Seeds: Homogeneously disperse a precise, small amount (e.g., 0.1-0.5% by weight of solute) of the prepared seed crystals into the solution. To prevent agglomeration, the seeds can be dusted onto the surface or suspended in a small volume of the same solvent and added as a slurry.

Step 4: Controlled Crystal Growth

- Once seeds are introduced, implement a very slow, linear cooling ramp (e.g., 0.1-0.5°C per hour). This slow rate ensures that growth occurs predominantly on the existing seeds rather than generating new nuclei.

- Maintain gentle, consistent agitation to ensure uniform supersaturation throughout the solution without causing excessive crystal attrition.

Step 5: Harvesting and Analysis

- Once the final temperature is reached, hold isothermal for a period to allow for Ostwald ripening if desired.

- Filter the crystals and wash with a cold solvent to remove residual mother liquor.

- Characterize: Analyze the final crystals using microscopy for size and aspect ratio, and techniques like PXRD to confirm polymorphic purity. Compare the mother liquor content and drying kinetics against unseeded batches.

Protocol 2: Czochralski Method for Bulk Single Crystal Growth

This advanced protocol is used for growing large, high-quality single crystals for specialized applications, such as scintillators or nonlinear optical materials [32] [31].

Step 1: Charge Preparation and Melting

- Weighing: Precisely weigh high-purity (e.g., 4N or 99.99%) precursor powders (e.g., Gd₂O₃, Tb₄O₇, Ga₂O₃ for GTAGG:Ce). To compensate for the evaporation of volatile components (e.g., Ga₂O₃), add an excess (e.g., 3%) of the stoichiometric amount [31].

- Homogenization: Mix the powders thoroughly using a ball mill or V-blender to ensure a homogeneous starting composition.

- Loading and Melting: Load the mixed charge into a refractory crucible (e.g., Iridium for high-temperature oxides). Place the crucible in the Czochralski puller furnace and heat under a controlled atmosphere (e.g., N₂ + 2% O₂ for GTAGG:Ce) until the charge is completely molten.

Step 2: Seed Crystal Immersion and Necking

- Seed Selection: A high-quality, oriented single crystal seed (e.g., <100> direction for garnet crystals) is mounted on the puller shaft.

- Immersion: Lower the seed crystal until it just contacts the surface of the melt. Allow a brief period for thermal equilibration.

- Necking: Initiate pulling and rotation slowly. Pull the seed upward rapidly at first to form a thin "neck." This process helps to eliminate dislocations that propagate from the seed, promoting the growth of a perfect single crystal.

Step 3: Shoulder Growth and Body Pulling

- After necking, gradually decrease the pull rate to allow the crystal diameter to increase, forming a "shoulder" until the desired target diameter (e.g., 1 inch) is achieved.

- Stable Growth: Maintain a constant diameter by automatically adjusting the pull rate and furnace temperature in response to diameter monitoring. For GTAGG:Ce, typical parameters are a pull rate of 0.7 mm/hour and a rotation rate of 10 rpm [31].

Step 4: Crystal Cooling and Harvesting

- Once the growth cycle is complete, slowly separate the crystal from the melt by gradually lifting it out while continuing rotation to minimize thermal stress.

- Annealing: Program a very slow cooling ramp (over many hours or days) to room temperature inside the furnace to anneal the crystal and relieve internal stresses.

Step 5: Characterization

- Structural Integrity: Cut and polish sections of the crystal for characterization. Use X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm single-phase structure and high crystallinity.

- Compositional Analysis: Employ Electron Probe Micro-Analysis (EPMA) along the growth axis to check for compositional homogeneity and element segregation [31].

Visualizing the Seeding Process and Phenomena

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflow of a seeding experiment and a recently observed phenomenon relevant to crystal growth in amorphous matrices.

Diagram 1: Single Crystal Seeding Workflow.

Diagram 2: Seed Rotation in Amorphous Matrix. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that a crystal seed can rotate during early growth stages in a glass matrix, challenging the assumption of perfect isotropy in amorphous materials. This rotation is driven by non-uniform forces from the glass structure and is amplified at higher temperatures [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of a seeding protocol relies on the use of specific, high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details the essential components of a crystal growth toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Seeding Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursor Powders | Source material for crystal growth. | Gd₂O₃, Tb₄O₇, Ga₂O₃, Al₂O₃ (4N purity for oxide crystals) [31]. For pharmaceuticals, use Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) of the highest available purity. |

| Seed Crystals | To provide a templated surface for controlled growth. | Can be pre-grown crystals of the target material (e.g., α-form L-glutamic acid [30]) or a structurally compatible material, oriented along a specific crystallographic axis (e.g., <100> GAGG:Ce [31]). |

| Specialized Solvents | To dissolve the solute and create a growth environment. | Choice depends on solute solubility and stability (e.g., water, ethanol, acetonitrile, DMSO). Must be high-purity and filtered. |

| Iridium Crucible | High-temperature melt containment. | Used in Czochralski growth of oxides with high melting points (e.g., GTAGG:Ce) due to its high melting point and chemical stability [31]. |

| Controlled Atmosphere Gases | To prevent oxidation/decomposition of melt/solution. | N₂, Ar, or mixtures with O₂ (e.g., N₂ + 2% O₂ [31]). For solution growth, inert atmospheres (e.g., Ar) can prevent oxidation of sensitive compounds. |

| Microtubes | For novel seeding in melt growth techniques. | Stainless steel microtubes (e.g., 6 μm ID) used in Microtube-Czochralski technique (μT-CZ) to seed via capillary rise of the melt [32]. |

Nanosheet Seeding Growth (NSG) is an advanced materials synthesis technique that utilizes two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets as templates to direct the epitaxial growth of functional thin films and nanomaterials. This method addresses a significant challenge in modern device fabrication: the difficulty of growing high-quality, oriented crystals on amorphous or non-crystalline substrates, which are essential for flexible and lightweight electronics. Traditional single-crystal substrates, while effective, present limitations due to their high cost, undesirable size, and poor workability for modern applications [34].

The fundamental principle of NSG involves using atomically thin, well-crystalline nanosheets as a seed or buffer layer. These nanosheets mimic the surface of a perfectly matching single crystal, providing the necessary crystallographic template for epitaxial growth. This process enables the creation of nanomaterials with desired morphology, structure, and functional properties (such as magnetic, ferroelectric, or optical characteristics) on a wide variety of substrates, including glass and plastics [34]. The technique was pioneered in applications such as the fabrication of highly oriented (001) LaNiO₃ films on (001) oriented Ca₂Nb₃O₁₀ nanosheet templates, where a lattice mismatch of less than 1% was achieved [34].

Types of 2D Nanosheets for Seed Layers

The selection of an appropriate 2D nanosheet is critical for successful NSG, as it determines the crystallographic orientation, lattice matching, and ultimate properties of the grown film or nanomaterial. A variety of 2D materials can serve as seed layers, each with distinct properties and advantages.

Table 1: Comparison of Common 2D Nanosheets for Seed Layers