Advanced Strategies for Improving Lipid Identification Accuracy in UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance lipid identification accuracy using UHPLC-MS/MS technologies.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Lipid Identification Accuracy in UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance lipid identification accuracy using UHPLC-MS/MS technologies. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we explore the critical challenges in lipidomics including structural diversity, isobaric interferences, and matrix effects. The content details optimized methodologies from sample preparation to data processing, presents practical troubleshooting strategies for common analytical issues, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks for clinical and biomedical research. With evidence from recent studies, this resource aims to bridge the gap between analytical innovation and robust biological interpretation in lipidomics research.

Understanding Lipid Complexity: Fundamental Challenges in UHPLC-MS/MS Identification

Lipids are far more than simple energy storage molecules; they are a structurally diverse group of hydrophobic or amphipathic molecules that play pivotal roles in cellular structure, signaling, and regulation [1]. The term "lipidome" refers to the complete profile of lipid species present in a biological system, which is estimated to contain hundreds of thousands of distinct molecular species [2]. This immense diversity presents significant challenges for comprehensive analysis, driving the development of specialized lipidomics approaches to decipher lipid functions and mechanisms in health and disease.

The LIPID Metabolites and Pathways Strategy (LIPID MAPS) consortium has established a comprehensive classification system that organizes lipids into eight main categories based on their chemical structures and biosynthetic pathways: fatty acyls (FA), glycerolipids (GL), glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP), sterol lipids (ST), prenol lipids (PR), saccharolipids (SL), and polyketides (PK) [1]. This systematic classification provides a crucial framework for organizing the vast array of lipid species encountered in lipidomics research.

Analytical Challenges in Lipidomics: The structural complexity of lipids creates substantial hurdles for accurate identification and quantification. Complete structural elucidation of a single glycerophospholipid, for example, requires characterization at multiple levels: (1) identity of the head group, (2) composition of acyl chains, (3) location of carbon-carbon double bonds, (4) sn-position of acyl/ether chains on the glycerol backbone, (5) identity and location of functional group substitutions, and (6) stereochemistry of double bonds and chiral centers [3]. These challenges are compounded by the wide concentration range of lipids in biological samples and their susceptibility to oxidation and hydrolysis during sample preparation and analysis [3].

Key Lipid Categories and Their Biological Functions

Understanding the major lipid categories and their biological significance provides essential context for interpreting lipidomics data. The table below summarizes the eight main lipid classes, their representative examples, and primary biological functions.

Table 1: Lipid Classification, Examples, and Biological Functions

| Category | Abbreviation | Example | Key Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acyls [1] | FA | Dodecanoic acid | Building blocks for complex lipids, energy sources, inflammatory mediators [1] |

| Glycerolipids [1] | GL | Triacylglycerol (Triglyceride) | Main storage fats, energy reservoir [1] |

| Glycerophospholipids [1] | GP | Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | Cell membrane components, signaling, metabolism [1] |

| Sphingolipids [1] | SP | Ceramide | Cell membrane structure, signaling, apoptosis [1] |

| Sterol Lipids [1] | ST | Cholesterol | Membrane fluidity regulation, hormone precursors [1] |

| Prenol Lipids [1] | PR | Farnesol | Antioxidants, vitamin precursors [1] |

| Saccharolipids [1] | SL | UDP-3-O-(3R-hydroxy-tetradecanoyl)-α-D-N-acetylglucosamine | Membrane components [1] |

| Polyketides [1] | PK | Aflatoxin B₁ | Secondary metabolites with antimicrobial and anticancer properties [1] |

Beyond their structural roles, lipids function as dynamic signaling molecules that influence various cellular processes. Phosphoinositides regulate intracellular signaling cascades controlling cell proliferation and apoptosis, while eicosanoids derived from arachidonic acid are involved in inflammation and immune responses [1]. Steroid hormones, derived from cholesterol, act as long-range chemical messengers coordinating processes like reproduction and stress response [1].

Analytical Challenges in Lipid Identification

The Reproducibility Gap in Software Platforms

A significant and underappreciated challenge in lipidomics is the lack of consistency in outputs from different lipidomics software platforms, even when processing identical spectral data [4]. A recent 2024 study highlighted this "reproducibility gap" by processing the same liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) data with two popular open-access platforms, MS DIAL and Lipostar [4]. The findings revealed alarmingly low agreement between identifications:

Table 2: Software Disagreement in Lipid Identification

| Data Type | Identification Agreement | Factors Contributing to Discrepancies |

|---|---|---|

| Default Settings (MS1) | 14.0% | Different algorithms, peak alignment methods, and default libraries [4] |

| Fragmentation Data (MS2) | 36.1% | Co-elution of lipids, co-fragmentation, different spectral interpretation [4] |

This low agreement underscores that lipid identifications from a single software platform cannot be considered definitive and highlights the critical importance of manual curation and cross-platform validation for confident biomarker identification [4].

Structural Isomer Differentiation

A paramount challenge in structural lipidomics is differentiating between lipid isomers—distinct lipids sharing the same molecular formula. Conventional tandem MS often fails to distinguish these subtle structural differences [3]. Key isomeric challenges include:

- Double Bond Position: The location of carbon-carbon double bonds (e.g., ω-3 vs. ω-6 fatty acids) has significant biological implications but is difficult to determine with standard collision-induced dissociation (CID) [3].

- sn-Positional Isomers: For glycerophospholipids, determining whether a specific fatty acyl chain is attached to the sn-1 or sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone is crucial for understanding biological function and enzyme specificity [5] [3].

- Ether vs. Ester Lipids: Plasmalogens (ether lipids with a vinyl-ether bond) are structurally similar to diacyl phospholipids but have distinct biological roles, including antioxidant properties [2]. Their identification requires careful attention to fragmentation patterns.

Advanced techniques such as ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) and ozone-induced dissociation (OzID) are emerging to address these challenges, but they are not yet widely implemented in routine lipidomics workflows [3].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do I get different lipid identification results when using different software platforms on the same dataset?

This is a common issue stemming from the "reproducibility gap" in lipidomics software [4].

- Root Cause: Different software platforms use distinct algorithms for peak picking, alignment, and database matching. They may also access different lipid libraries (e.g., LipidBlast, LipidMAPS), each with unique entries and fragmentation spectra [4].

- Solution:

- Do not rely on a single software's output. Process your data with multiple platforms if possible.

- Implement manual curation of putative identifications. Visually inspect MS/MS spectra to confirm fragment ions match the proposed structure [4].

- Utilize orthogonal data. Incorporate retention time (tR) prediction to support identifications, as isobaric lipids often have different elution times [5].

- Validate across ionization modes. Confirm identifications in both positive and negative LC-MS modes where applicable [4].

FAQ 2: How can I improve confidence in annotating lipid isomers with similar MS/MS spectra?

Distinguishing isomers requires moving beyond standard workflows.

- Root Cause: Conventional CID often produces nearly identical fragmentation patterns for isomers like sn-positional isomers or double bond position isomers [3].

- Solution:

- Leverage Chromatographic Separation: Optimize your UHPLC method to maximize separation of isomeric species before they enter the mass spectrometer [5].

- Incorporate Retention Time Prediction: Use a set of standard compounds to establish a relationship between lipid structure and tR. Compare the experimental tR of your unknown to the predicted tR for candidate isomers [5].

- Utilize Advanced Dissociation Techniques: If available, employ techniques like UVPD or OzID that can generate fragment ions specific to double bond location or sn-position [3].

- Consult Specialized Libraries: Use libraries that contain reference spectra for specific isomers, if they exist for your lipid class.

FAQ 3: My method sensitivity has dropped, and ion suppression seems high. What steps should I take?

This often points to issues with sample cleanliness or instrument maintenance.

- Root Cause: Contamination from sample matrices or non-volatile mobile phase additives accumulating in the ion source, causing ion suppression and reduced sensitivity [6].

- Solution:

- Review Sample Preparation: Implement or enhance sample clean-up. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) can be more effective than simple protein precipitation for removing interfering contaminants [6].

- Use Volatile Mobile Phases: Ensure you are using only volatile additives (e.g., ammonium formate, ammonium acetate, formic acid) and avoid non-volatile salts like phosphates [6].

- Employ a Divert Valve: Use the divert valve to direct the initial solvent front and late-eluting, highly non-polar compounds away from the mass spectrometer. This prevents unnecessary contamination of the ion source [6].

- Perform Regular Source Maintenance: Clean the ion source and cone according to the manufacturer's schedule. A contaminated source is a primary cause of sensitivity loss.

Advanced Workflows for Improved Lipid Identification

Molecular Networking Combined with Retention Time Prediction

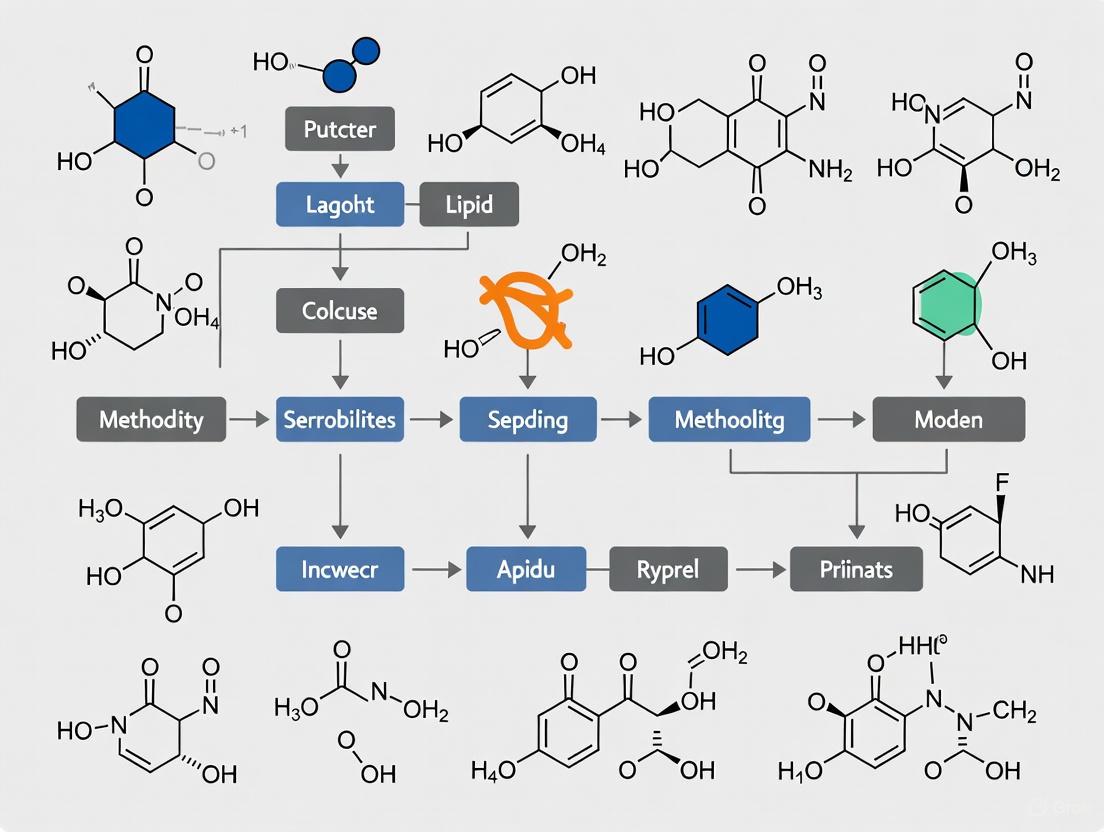

A powerful strategy for improving annotation confidence combines molecular networking (MN) with retention time prediction [5]. The workflow below illustrates this integrated approach:

This workflow was successfully applied to annotate over 150 unique phospholipid and sphingolipid species in human corneal epithelial cells, demonstrating its utility in discovering lipids involved in relevant biological processes like inflammation [5].

Data-Driven Quality Control with Machine Learning

To address the problem of false positive identifications, a post-software quality control step using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) regression algorithm with leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) can be implemented [4]. This method uses the relationship between lipid structure and retention time to flag potential outlier identifications for manual re-inspection. The model is trained on a set of confident identifications, and then predicts the expected tR for other lipids. Putative identifications with large deviations from their predicted tR are flagged as potentially erroneous [4]. This approach provides a platform-agnostic method to improve the overall reliability of the dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Item | Function/Application | Example / Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standard Mixture [2] | Corrects for variability in sample prep, extraction, and ionization efficiency. Essential for quantification. | Avanti EquiSPLASH [4] or labeled analogs (e.g., PC(16:1/0:0-D3) [2]. Should cover multiple lipid classes. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents [6] | Mobile phase preparation. Reduces chemical noise and prevents instrument contamination. | Highest purity acetonitrile, methanol, isopropanol, and water. |

| Volatile Buffers/Additives [6] | Modifies mobile phase pH and ionic strength to control separation and ionization. | Ammonium formate, ammonium acetate, formic acid. Avoid non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphates). |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards [7] | Absolute quantification for targeted methods. | Deuterated (D) or 13C-labeled versions of target analytes (e.g., for signaling lipids [7]). |

| Quality Control (QC) Pooled Sample | Monitors instrument stability and data quality throughout the batch. | A pool of all experimental samples, injected repeatedly. |

| Reference Material [8] [7] | Benchmarking method performance and inter-laboratory comparison. | NIST SRM 1950 - Metabolites in Human Plasma [8] [7]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Representative UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from methods used in recent literature to analyze a lipid extract from a human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line (PANC-1) [4] and signaling lipids in NIST SRM 1950 plasma [7].

Step 1: Lipid Extraction

- Method: Modified Folch extraction [4].

- Procedure:

- Add a chilled solution of methanol/chloroform (1:2 v/v) supplemented with 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) to your sample to prevent oxidation [4].

- Spike in a mixture of quantitative internal standards (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH) to account for procedural losses and ion suppression [4] [2].

- Vortex thoroughly and centrifuge to separate phases.

- Collect the lower organic phase containing the lipids.

Step 2: UHPLC Separation

- Column: Reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 50 × 0.3 mm, 1.7 μm) [4] or similar.

- Mobile Phase:

- Gradient:

- Flow Rate: 8 μL/min for microflow [4] or 0.400 mL/min for conventional flow [2].

- Temperature: 50°C [2].

Step 3: Mass Spectrometry Analysis

- Instrument: Q-TOF or orbital trap mass spectrometer capable of high-resolution and MS/MS fragmentation [4] [2].

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), in both positive and negative mode switching for comprehensive coverage [5] [2].

- Data Acquisition:

Step 4: Data Processing & Identification

- Process raw data with software (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar, MZmine 2) for peak picking, alignment, and deisotoping [4] [5].

- Annotate lipids by matching accurate mass and MS/MS spectra against databases (e.g., LipidBlast, LipidMAPS) [4].

- Perform manual curation of spectra to verify head group and fatty acyl fragment ions [4] [5].

- Apply quality control checks, such as SVM-based outlier detection for retention time consistency, to flag potential false positives [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

How to resolve conflicting lipid identifications from different software platforms?

Problem: When processing identical LC-MS/MS data, different lipidomics software platforms (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar) yield conflicting lipid identifications, compromising reproducibility.

Solution: Implement a multi-platform verification and manual curation workflow [4].

Investigation Steps:

- Process your raw data through at least two established lipidomics software platforms using similar parameter settings and lipid libraries where possible.

- Cross-reference the outputs. A study found that default software settings can yield as low as 14% identification agreement, improving only to 36.1% when using MS2 spectra [4].

- Manually inspect the MS/MS spectra and chromatographic peaks for conflicting identifications. Check for co-elution and potential ion suppression.

Resolution Steps:

- Require orthogonal evidence: Do not rely on MS2 data alone. Use retention time (tR) prediction models or compare with standard compounds if available [5].

- Leverage all available data: Acquire data in both positive and negative ionization modes to gather complementary fragmentation evidence [4].

- Apply a scoring system: Use a data quality scoring system that awards points for different layers of analytical evidence (e.g., accurate mass, MS/MS spectrum, validated tR, ion mobility data) to prioritize high-confidence identifications [9].

How to differentiate lipid isomers that are not separated chromatographically?

Problem: Isomeric lipids (e.g., sn-positional isomers, double bond isomers, plasmenyl vs. plasmanyl ether lipids) co-elute and generate nearly identical MS/MS spectra, making definitive annotation impossible with standard LC-MS/MS.

Solution: Enhance separation or use advanced fragmentation techniques [10].

Investigation Steps:

- Check your MS/MS spectra for characteristic fragment patterns. For glycerophospholipids, the relative intensity of sn1 and sn2 carboxylate fragments can indicate acyl chain position, though this is not always definitive [5].

- For ether lipids, look for specific fragments in negative ion mode. The formate adduct of ether-linked PC can yield an abundant sn2 fatty acyl fragment [10].

Resolution Steps:

- Optimize chromatography: Extend chromatographic gradients or use alternative stationary phases to improve resolution of isomeric species.

- Incorporate ion mobility spectrometry (IMS): IMS provides an additional separation dimension based on the size, shape, and charge of ions, helping to separate isobaric and isomeric species [11] [12].

- Employ advanced MS techniques: Use ozone-induced dissociation (OzID) or ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) to pinpoint double-bond positions within fatty acyl chains. These techniques are not yet routine but are available on advanced instrumentation.

- Report annotations correctly: If isomers cannot be resolved, report the annotation at the sum composition level (e.g., PC(36:1)) or list all possible isomeric candidates, clearly stating the level of uncertainty [10].

How to detect and quantify low-abundance lipids masked by high-abundance species?

Problem: High-abundance lipid classes (e.g., phosphatidylcholine) cause ion suppression, preventing the detection and accurate quantification of low-abundance, yet biologically important, lipids (e.g., signaling lipids like oxylipins, lysophospholipids).

Solution: Implement targeted enrichment and sensitive acquisition methods [7].

Investigation Steps:

- Examine the total ion chromatogram and base peak chromatogram for over-saturated peaks.

- Check the extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) for low-intensity peaks corresponding to low-abundance lipids of interest. A noisy or unstable baseline in the XIC can indicate ion suppression.

Resolution Steps:

- Improve sample preparation: Use solid-phase extraction (SPE) to selectively enrich specific classes of low-abundance lipids and remove high-abundance interferents [12]. For signaling lipids, a tailored extraction protocol is essential [7].

- Shift to targeted MS methods: Develop a targeted UHPLC-MS/MS method using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) or parallel reaction monitoring (PRM). These methods dramatically increase sensitivity and specificity for pre-defined target lipids [7] [13].

- Use chemical derivatization: Derivatize low-abundance lipids to improve their ionization efficiency and introduce characteristic fragments for more sensitive and selective detection [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: We only have an untargeted method. How can we improve confidence in our lipid annotations without standards?

A1: You can adopt several strategies to enhance confidence:

- Use Molecular Networking: Platforms like GNPS can cluster lipids with similar MS/MS spectra, allowing you to propagate annotations from well-annotated nodes (e.g., from standard compounds or high-quality spectra) to unknown lipids within the same cluster [5].

- Predict Retention Time: Develop in-house retention time prediction models based on a set of standard compounds analyzed under your specific LC conditions. A close match between experimental and predicted tR provides strong orthogonal evidence for an annotation [5].

- Follow Reporting Standards: Always use the shorthand nomenclature that reflects your experimental evidence. For example, use an underscore (e.g., PC(16:0_18:1)) when fatty acyl constituents are known but their positions on the glycerol backbone are not confirmed [10].

Q2: What is the biggest mistake you see in lipid annotation, and how can we avoid it?

A2: A common critical error is annotating lipids based solely on exact mass [10]. Given the immense complexity and overlap in the lipidome, an exact mass can correspond to dozens of potential lipid species from different classes. Avoid this by:

- Mandating MS/MS data: Require MS/MS confirmation for all reported lipid identifications.

- Inspecting Fragmentation Patterns: Look for multiple diagnostic fragments (head group, fatty acyl chains) rather than a single fragment ion [5] [10].

- Being Wary of m/z 184.0733: The phosphocholine fragment is common to both phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin (SM). Co-isolation and co-fragmentation of isobaric PC and SM species can lead to misannotation. Use negative ion mode to confirm fatty acyl chains for PCs [10].

Q3: Our sample preparation is variable. How does this impact lipid annotation and quantification?

A3: Inconsistent sample preparation is a major source of error and directly impacts data quality and biological interpretation [11] [12].

- Impact on Annotation: Improper handling can generate artifactual lipids. For example, leaving samples at room temperature or incorrect pH can lead to hydrolysis (increasing lysophospholipids) or fatty acyl scrambling in lysophospholipids [11] [12].

- Impact on Quantification: Inefficient or variable lipid extraction skews the apparent abundance of lipid classes, especially for polar anionic lipids (e.g., phosphatidic acid, sphingosine-1-phosphate) [12].

- Best Practices:

- Standardize Protocols: Flash-freeze tissues immediately; process biofluids quickly and store at -80°C [11].

- Add Internal Standards: Add a cocktail of deuterated internal standards before extraction to monitor and correct for extraction efficiency, matrix effects, and instrument variability [12].

- Choose the Right Extraction: Use an acidified Bligh & Dyer for anionic lipids, but strictly control acid concentration and time to avoid hydrolysis [12].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Molecular Networking with Retention Time Prediction for Enhanced Annotation

This protocol is adapted from research that combined molecular networking with retention time prediction to annotate over 150 phospholipids and sphingolipids in a cellular model [5].

Standard Mixture Analysis:

- Acquire UHPLC-HRMS/MS data for a mixture of ~65 lipid standards covering your classes of interest.

- Use a collision energy ramp (e.g., 20-40 eV) to optimize the detection of diagnostic fragment ions (head group and fatty acyl chains) [5].

Data Pre-processing:

- Process raw data (standard and sample files) with software like MzMine 2 to perform peak detection, alignment, and gap filling [5].

- Export a feature table (m/z, tR, intensity) and MS/MS spectra in .mgf format.

Molecular Network Creation:

- Upload the .mgf file to the GNPS platform .

- Set parameters for cosine score and minimum matched fragment ions to create a network where nodes (lipids) are connected based on MS/MS spectral similarity [5].

Retention Time Model Building:

- Using the standard mixture data, establish a relationship between lipid structure (e.g., acyl chain length and degree of unsaturation) and retention time.

- Apply this model to predict the tR of unknown lipids in your sample.

Annotation and Validation:

- Annotate unknown lipids based on their placement in the molecular network (proximity to standards) and the agreement between their experimental and predicted retention times [5].

Protocol: Comprehensive Targeted Analysis of Signaling Lipids

This protocol is based on a validated method for profiling 261 signaling lipids, including oxylipins, lysophospholipids, and endocannabinoids [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Spike 50 µL of plasma/serum or a homogenized tissue extract with a cocktail of stable isotope-labeled internal standards.

- Perform a fast, optimized liquid-liquid extraction using methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)/methanol/water or a similar solvent system tailored for polar lipids [7].

- Evaporate the organic layer to dryness and reconstitute in a suitable injection solvent.

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Column: Use a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 100-150 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 µm) for separation.

- Chromatography: Employ a binary gradient with eluent A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and eluent B (acetonitrile/isopropanol with 0.1% formic acid). A typical gradient runs from 40% B to 99% B over 10-15 minutes [7].

- Mass Spectrometry: Operate a triple quadrupole (QqQ) or high-resolution mass spectrometer in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Monitor at least two specific transitions (quantifier and qualifier) for each signaling lipid.

Quantification:

- Generate a 10-point calibration curve for each analyte using the ratio of analyte to internal standard peak area.

- Validate the method for linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), precision, accuracy, and extraction recovery [7].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key challenges in lipid annotation and corresponding strategic solutions.

| Obstacle Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Annotation | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isobaric Species | Different lipid classes with the same nominal mass (e.g., PC vs. SM). | Misidentification of lipid class, leading to incorrect biological interpretation [10]. | Use orthogonal data: MS/MS in both ionization modes, retention time validation, and ion mobility separation [4] [12]. |

| Isomers | sn-positional isomers, double-bond location, plasmenyl vs. plasmanyl ether lipids. | Inability to distinguish structurally distinct lipids with unique biological functions [10]. | Advanced techniques: Ozone-induced dissociation (OzID), ion mobility, or detailed MS/MS intensity analysis. Correctly report isomeric uncertainty [10]. |

| Low-Abundance Lipids | Signaling lipids (e.g., oxylipins, S1P) suppressed by high-abundance membrane lipids. | Critical bioactive species remain undetected, biasing the biological conclusion [7]. | Targeted enrichment (SPE), chemical derivatization, and sensitive acquisition methods (MRM/PRM) [7] [12]. |

| Software & Data Reproducibility | Inconsistent results from different software platforms using identical data [4]. | Lack of reproducibility and reliability in biomarker identification [4]. | Multi-platform validation, manual curation of spectra, and application of data quality scoring systems [4] [9]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for overcoming lipid annotation challenges.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., EquiSPLASH) | Correct for extraction variability, matrix effects, and instrument response drift; enable absolute quantification [4] [12]. | Added at the very beginning of sample preparation to monitor the entire workflow [12]. |

| Commercial Lipid Standard Mixtures | Build retention time prediction models; validate fragmentation patterns; create spectral libraries [5]. | Used to establish calibration curves and confirm diagnostic fragments for a specific lipid class under local LC-MS conditions [5]. |

| Specialized Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Kits | Fractionate lipid classes or enrich specific low-abundance lipids, reducing sample complexity and ion suppression [12]. | Selective enrichment of oxylipins or phospholipids from a complex biological extract prior to LC-MS analysis [7]. |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., dimethylaminoethyl (DMAE)) | Enhance ionization efficiency of low-abundance or poorly ionizing lipids; introduce characteristic fragments for better identification [12]. | Derivatization of fatty acids to improve their detection sensitivity in negative ion mode. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Integrated Lipid Identification Workflow

Software Discrepancy Troubleshooting Logic

Core UHPLC Separation Mechanisms for Lipid Classes

In UHPLC-MS/MS based lipidomics, the separation of lipids is primarily achieved through Reversed-Phase Chromatography. This mechanism separates lipid molecules based on their hydrophobicity, which is influenced by the combined characteristics of their acyl chains [14].

The table below summarizes the primary factors governing the reversed-phase separation of lipids:

| Separation Factor | Effect on Retention Time | Molecular Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Total Acyl Chain Length | Increases with longer chains | Increased hydrophobic surface area, leading to stronger interaction with the non-polar stationary phase [14]. |

| Number of Double Bonds | Decreases with more double bonds | Introduction of double bonds reduces overall hydrophobicity by introducing kinks in the chain, weakening hydrophobic interactions [14]. |

| sn-Position of Acyl Chains | Minor influence on retention | The specific location (sn-1 or sn-2) on the glycerol backbone can be resolved for some lipid types, such as lysophospholipids and diacyl phospholipids [14]. |

This separation mechanism is capable of resolving not only different lipid species but also structural and positional isomers, which is critical for accurate lipid identification [14]. The typical order of elution is from the most polar (short, saturated chains) to the least polar (long, polyunsaturated chains). For example, lysophospholipids, which contain only one fatty acyl chain, elute early, followed by diacyl phospholipids (like PCs and PEs), with cholesteryl esters and triacylglycerols eluting last [15].

UHPLC Troubleshooting Guide for Lipidomics

Symptom-Based Troubleshooting

Encountering issues during a UHPLC run is common. The following table outlines frequent problems, their potential causes, and solutions specific to lipidomic analyses.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing | - Interaction of basic compounds with silanol groups on the column.- Active sites on the column. | - Use high-purity silica (Type B) or polar-embedded stationary phases.- Add a competing base like triethylamine to the mobile phase.- Replace the column [16]. |

| Broad Peaks | - Excessive extra-column volume.- Detector flow cell volume too large.- Column degradation or void. | - Use short capillaries with narrow internal diameter (e.g., 0.13 mm for UHPLC).- Ensure flow cell volume is ≤1/10 of the smallest peak volume.- Replace the column [16]. |

| Retention Time Drift | - Poor temperature control.- Incorrect mobile phase composition.- Poor column equilibration. | - Use a thermostat-controlled column oven.- Prepare fresh mobile phase and ensure the mixer is functioning for gradients.- Increase column equilibration time between runs [17]. |

| Split Peaks | - Blocked frit or particles on the column head.- Channels in the column. | - Replace the pre-column frit or guard column.- If problem persists, replace the analytical column [16]. |

| Loss of Sensitivity | - Detector time constant set too high.- Contaminated guard or analytical column.- Needle or injector blockage. | - Decrease the detector time constant.- Replace the guard column; flush or replace the analytical column.- Flush or replace the injector needle [17]. |

Pressure Abnormalities

Pressure issues are often the first sign of a problem. The table below helps diagnose these abnormalities.

| Symptom | Common Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Pressure | - Blockage in the flow path, most commonly at an in-line filter or column frit.- Mobile phase precipitation. | - Isolate the blockage by sequentially loosening connections. Replace the in-line filter frit.- Back-flush the column (if permitted).- Flush the system with a strong solvent and prepare fresh mobile phase [18]. |

| Low Pressure | - Air in the pump.- Leak in the system.- Faulty check valve. | - Purge the pump to remove air bubbles.- Check and tighten all fittings; replace damaged seals.- Perform a timed collection to verify pump delivery [18]. |

| Pressure Fluctuations | - Air in the system.- Pump seal failure.- Leak. | - Degas all solvents and purge the pump.- Replace worn pump seals.- Identify and fix the source of the leak [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard UHPLC-MS/MS Method for Lipidomics

The following is a detailed methodology for global lipidomic profiling, adapted from established approaches in the literature [14] [15].

Sample Preparation

- Extraction: Use a liquid-liquid extraction protocol. A modified Folch extraction (chloroform:methanol, 2:1 v/v) is efficient for most glycero-, phospho-, and sphingolipids [15].

- Internal Standards: Add a quantitative mixture of synthetic lipid standards (e.g., from LIPID MAPS) prior to extraction to correct for variations in extraction efficiency, ionization, and instrument response [14].

UHPLC Instrumental Conditions

- Column: 100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7-μm dp Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (or equivalent) [15].

- Column Temperature: 50 °C [15].

- Mobile Phase A: Ultrapure water with 1 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% formic acid [15].

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile:Isopropanol (1:1, v/v) with 1 mM ammonium acetate and 0.1% formic acid [15].

- Gradient:

- 0 min: 35% B

- 2 min: 80% B

- 7 min: 100% B

- Hold at 100% B for 7 min (Total run time: 14 min) [15].

- Flow Rate: 0.400 mL/min [15].

- Injection Volume: 2.0 μL (maintained at 10 °C) [15].

Mass Spectrometry Parameters

- Instrumentation: High-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap).

- Ionization Mode: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), both positive and negative ion modes are recommended for comprehensive coverage [14].

- Mass Range: m/z 300–1200 [15].

- MS/MS Acquisition: Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) is used. A collision energy ramp (e.g., 20–40 eV) is optimal to generate diagnostic fragment ions for polar head groups and fatty acyl chains without completely suppressing the precursor ion [5].

Data Processing

- Use software such as MZmine 2 for peak detection, alignment, and integration [5] [15].

- Identify lipids using an internal spectral library, matching accurate mass, isotopic pattern, retention time, and MS/MS fragments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my chromatogram show double peaks for a single lipid standard? This can indicate the presence of isomers that are being resolved by the UHPLC method. For instance, the method can separate positional isomers of lysophospholipids or structural isomers of diacyl phospholipids. Verify by checking the MS/MS spectra; isomeric lipids will have identical precursor masses but may produce different fragment ion ratios [14].

Q2: My peak shapes are good initially but become broader over time. What should I do? This is a classic sign of column contamination or the formation of a void at the column inlet. Lipids from biological matrices can be very "dirty." First, replace the guard column. If the issue persists, flush the analytical column with a strong solvent. As a preventative measure, use a guard column, filter your samples, and ensure your extraction protocol is clean [16] [17].

Q3: How can I differentiate between a phosphatidylcholine (PC) and a sphingomyelin (SM) that have the same nominal mass? While they may co-elute, you can differentiate them using fragmentation patterns in negative ion mode. PC species are often detected as [M-CH₃]⁻ ions and yield fragments for demethylated lysophosphatidylcholine and fatty acyl chains. SMs will produce fragments characteristic of the sphingoid base and the N-acyl fatty acid. High-resolution MS is crucial to distinguish their exact masses [5].

Q4: What is the advantage of UHPLC over a direct infusion (shotgun) approach in lipidomics? The primary advantage is reduced ion suppression and the ability to resolve isomeric and isobaric species. Chromatographic separation ensures that lipids enter the mass spectrometer at different times, which minimizes competition for charge and results in more accurate identification and quantification, especially for low-abundance lipids [14] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents required for successful UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomic analysis.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| C18 UHPLC Column | Core stationary phase for reversed-phase separation of lipids by hydrophobicity. | 100-150 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7-1.8 μm particle size (e.g., Acquity UPLC BEH C18) [15]. |

| Lipid Internal Standards | For normalization and absolute quantification; corrects for analytical variability. | Synthetic, non-naturally occurring lipids (e.g., PC(17:0/17:0), Cer(d18:1/17:0)) [14] [15]. |

| Ammonium Acetate | A volatile buffer added to the mobile phase to enhance the formation of [M+Ac]⁻ adducts and improve ionization stability in negative mode. | LC-MS grade [15]. |

| Formic Acid | A volatile acid added to the mobile phase to promote protonation [M+H]⁺ in positive ion mode. | LC-MS grade, typically used at 0.1% [15]. |

| Chloroform & Methanol | Primary solvents for liquid-liquid extraction of a wide range of lipid classes from biological matrices. | HPLC-grade or higher (e.g., Chromasolv) [14]. |

| In-line Filter / Guard Column | Protects the expensive analytical column from particulates and contaminants in the sample. | 0.5-μm or 0.2-μm porosity frit, placed between the autosampler and column [18]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

UHPLC-MS Lipid Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying lipids using UHPLC-MS/MS, integrating chromatographic and spectrometric data.

Lipid Fragmentation for Structural Elucidation

This diagram outlines the key fragments used to determine the structure of a phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipid from its MS/MS spectrum in negative ion mode.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts

Q1: What are the main MS-based strategies in lipidomics and when should I use each one?

Lipidomics employs three primary MS strategies, each suited for different research objectives [19] [20]:

Untargeted Lipidomics: This is a discovery-based approach aimed at comprehensively profiling all detectable lipids in a sample without prior bias. It is ideal for hypothesis generation and discovering novel lipid biomarkers. High-resolution mass spectrometers (such as Q-TOF, Orbitrap) are typically used, often in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) modes [19].

Targeted Lipidomics: This method focuses on the precise identification and accurate quantification of a predefined set of lipid molecules. It is used for validating potential biomarkers identified in untargeted screens. It employs techniques like Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) on triple quadrupole instruments, offering high sensitivity and specificity for the target analytes [19] [21].

Focused Lipidomics: This strategy uses class-specific fragmentation patterns to comprehensively analyze lipids within certain categories. Techniques like precursor ion scanning and neutral loss scanning on tandem MS systems are used to detect all lipids that share a common structural feature, such as a specific polar head group [20].

Q2: How does electrospray ionization (ESI) facilitate lipid analysis, and what are its main advantages?

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a "soft" ionization technique that gently transfers lipids from a liquid solution into the gas phase as ions without significant fragmentation [20] [21]. Its key advantages for lipidomics include:

- Applicability to Polar Lipids: It is exceptionally well-suited for analyzing polar lipids like phospholipids [20].

- Versatile Adduct Formation: Lipids can form various adducts (e.g., [M+H]⁺, [M+NH₄]⁺, [M+Na]⁺ in positive mode; [M-H]⁻, [M+acetate]⁻ in negative mode), which can be leveraged for different analyses [21].

- Compatibility with LC-MS: It seamlessly interfaces with liquid chromatography, reducing ion suppression and enabling the analysis of complex mixtures [5] [20].

- High Sensitivity and Reproducibility: It provides low detection limits and good reproducibility for quantitative analyses [20].

Q3: Why is fragmentation pattern analysis critical for lipid identification, especially in MS/MS?

Fragmentation patterns provide the structural fingerprints of lipid molecules. During tandem MS (MS/MS), selected precursor ions are fragmented, and the resulting product ion spectrum reveals information about [5] [22]:

- Polar Head Group: Diagnostic ions identify the lipid class (e.g., m/z 184.0733 for phosphocholine in positive mode; m/z 168.0423 for demethylated phosphocholine in negative mode) [5].

- Fatty Acyl Chains: Carboxylate anions ([RCOO]⁻) indicate the composition and chain length of the fatty acids attached to the glycerol backbone [5] [22].

- Regioisomer Differentiation: The relative intensity of sn-1 and sn-2 carboxylate fragment ions can help determine the position of the fatty acyl chains on the glycerol moiety. For instance, in PC and PE, the sn-2 carboxylate is typically more intense than the sn-1 [5] [22].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Ionization and Fragmentation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal Intensity | - Ion suppression from complex matrix- Suboptimal ESI parameters (e.g., nebulizing gas, voltages)- Poor lipid extraction efficiency | - Improve chromatographic separation to reduce co-elution [5]- Optimize ion source parameters for your specific instrument and solvent system- Use a validated extraction method (e.g., Bligh & Dyer, MTBE) and include internal standards [23] |

| In-source Fragmentation | - Excessively high source collision energy or declustering potential | - Systematically lower the source-induced dissociation voltage or energy to preserve the molecular ion [5] |

| Poor Fragmentation Efficiency | - Incorrect collision energy (CE) setting | - Perform CE ramping experiments to find the optimal energy that generates abundant diagnostic fragments without completely destroying the precursor ion [5] [22]. For example, a 20-40 eV ramp is often suitable for phospholipids [5]. |

| Inability to Distinguish sn-1/sn-2 Isomers | - Insufficient energy resolution of fragments- Lack of reference standards | - Utilize the consistent intensity ratio of sn-1 vs. sn-2 carboxylate anions in negative ion mode. For PCs, PEs, and PGs, the sn-2 chain produces a more intense fragment [5] [22]. |

| Complex Spectra with Isobaric Interferences | - Co-eluting lipids of the same nominal mass but different structures | - Employ high-resolution mass analyzers (Orbitrap, FT-ICR, Q-TOF) to separate ions by accurate mass [19] [20]- Use ion mobility separation if available as an additional dimension of resolution [5] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Lipid Separation and Identification

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Separation of Lipid Classes | - Inappropriate chromatographic method (e.g., using reversed-phase for class separation) | - For lipid class separation, use normal-phase (NP)LC or hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) [21]. |

| Poor Peak Shape | - Secondary interactions with the column- Mobile phase pH or buffer issues | - Use mobile phase additives (e.g., ammonium formate/acetate) to improve peak shape- Condition the column thoroughly and ensure it is suitable for lipids |

| Unreliable Lipid Identification | - Over-reliance on m/z alone without MS/MS confirmation- Lack of authentic standards for validation | - Always use MS/MS spectral matching for identification. When standards are unavailable, use molecular networking platforms (e.g., GNPS) that compare your unknown's spectrum to library spectra [5].- Incorporate retention time prediction models to support identification [5]. |

| Quantification Inaccuracy | - Ion suppression effects- No appropriate internal standard correction | - Use stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) for each lipid class being quantified to correct for recovery and matrix effects [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Optimizing Collision Energy for Phospholipid Fragmentation

This protocol is designed to systematically determine the optimal collision energy for obtaining high-quality MS/MS spectra of phospholipids, based on methodologies detailed in the literature [5] [22].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Lipid standard mixture containing representatives of major phospholipid classes (e.g., PC(16:0/18:1), PE(16:0/18:1), PI(16:0/18:1), PS(16:0/18:1), PG(16:0/18:1))

- UHPLC system with C18 reversed-phase column

- High-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Orbitrap) equipped with an ESI source

- Mobile phases: (A) water:acetonitrile (40:60, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate; (B) isopropanol:acetonitrile (90:10, v/v) with 10 mM ammonium formate

2. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Reconstitute the lipid standard mixture in a suitable solvent (e.g., chloroform:methanol, 1:1, v/v) and inject onto the UHPLC-MS/MS system.

- Step 2: For each phospholipid standard, select the precursor ion ([M+H]⁺ for PE, PS, PI, PG; [M+CH₃COO]⁻ or [M-H]⁻ for PC in negative mode) for MS/MS analysis.

- Step 3: Acquire MS/MS spectra across a collision energy ramp (e.g., 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 50 eV).

- Step 4: Analyze the resulting spectra for each energy level. The optimal collision energy is the one that produces a balanced spectrum with a clear precursor ion and abundant, structurally informative fragment ions (e.g., head group fragments and carboxylate anions from fatty acyl chains).

3. Data Interpretation:

- For PC in Negative Ion Mode [5]: Monitor for the appearance of the demethylated phosphocholine ion (m/z ~168), carboxylate anions from the fatty acyl chains (e.g., m/z 255.2 for 16:0, 281.2 for 18:1), and lysophospholipid-type ions. A collision energy ramp of 20-40 eV is often ideal.

- For Other Phospholipids: Identify the energy that maximizes the intensity of the head group-specific fragment (e.g., m/z 196 for PI [M-H-C₆H₁₀O₅]⁻) and the carboxylate anions.

Protocol 2: Determining sn-1/sn-2 Fatty Acyl Positional Isomers

This protocol uses the characteristic fragmentation rules of phospholipids in negative ion mode to assign the positions of the fatty acyl chains [5] [22].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Purified phospholipid sample of unknown regiochemistry

- UHPLC-MS/MS system as in Protocol 1

2. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Analyze the phospholipid using UHPLC-MS/MS in negative ion mode. Ensure the MS/MS spectrum shows clear carboxylate anion fragments.

- Step 2: Identify the two carboxylate anions corresponding to the two fatty acyl chains.

- Step 3: Apply the established intensity rules:

3. Data Interpretation:

- In a spectrum for a putative PC(16:0/18:1), if the intensity of the ion at m/z 281.2 (oleate, 18:1) is significantly greater than the ion at m/z 255.2 (palmitate, 16:0), this confirms that the 18:1 chain is at the sn-2 position.

Lipidomics Workflow and Fragmentation Pathway Visualization

Lipid Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a comprehensive UHPLC-MS/MS based lipidomics study, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Phospholipid Fragmentation Pathway

This diagram summarizes the key fragmentation pathways for a phosphatidylcholine (PC) molecule in negative ion mode, leading to diagnostic ions used for identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS) | Corrects for variations in extraction efficiency, ionization suppression, and instrument response, enabling accurate quantification [21]. | Add a cocktail of SIL-IS (e.g., ¹³C or ²H-labeled PCs, PEs, SMs, etc.) to the biological sample prior to lipid extraction. |

| Commercial Lipid Standard Mixtures | Provides reference retention times and characteristic MS/MS spectra for lipid identification and method development [5]. | Used in Protocol 1 to optimize collision energy and build in-house spectral libraries. |

| Methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | A solvent for efficient and clean lipid extraction, forming a top lipid-containing MTBE layer and a bottom protein pellet, simplifying recovery [23]. | Used as the primary solvent in the MTBE extraction method, an alternative to the classic Bligh & Dyer method. |

| Ammonium Formate/Acetate | A volatile buffer salt used in LC mobile phases to enhance ionization efficiency and stabilize ion adducts in the MS source [5]. | Added to UHPLC mobile phases (e.g., 10 mM) for robust and reproducible lipid separation and detection. |

| Specialized MS Matrices (e.g., DHB, THAP) | A matrix that co-crystallizes with the analyte to absorb laser energy and facilitate soft ionization in MALDI-MS [23] [20]. | Used for preparing samples for MALDI-MS or MALDI imaging mass spectrometry of lipids. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Data Processing Issues

FAQ: Why do I get different lipid identifications when processing the same data with different software platforms?

This is a widespread reproducibility challenge in lipidomics. When identical LC-MS spectra were processed using MS DIAL and Lipostar with default settings, only 14.0% identification agreement was achieved. Even when using more reliable fragmentation data (MS2 spectra), agreement only reached 36.1% [4].

Primary causes for these discrepancies include [4]:

- Different algorithmic approaches to peak picking, alignment, and identification

- Use of different lipid libraries (e.g., LipidBlast, LipidMAPS, ALEX123)

- Varied handling of co-eluting lipids and background noise

- Inconsistent use of retention time information for confirmation

Solution: Implement a multi-step validation workflow:

- Process data through at least two software platforms

- Manually curate conflicting identifications by examining raw spectra

- Cross-validate using both positive and negative LC-MS modes

- Apply machine learning quality controls like Support Vector Machine (SVM) regression with leave-one-out cross-validation to flag potential false positives [4]

FAQ: How should I handle missing values in my lipidomics dataset?

Missing values are common and require careful handling, as they can arise from different mechanisms [24]:

Table: Strategies for Handling Missing Values

| Type of Missing Value | Cause | Recommended Imputation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) | Pure random events (e.g., broken vials) | k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Random Forest |

| Missing at Random (MAR) | Technical factors (e.g., ion suppression) | k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Random Forest |

| Missing Not at Random (MNAR) | Abundance below detection limit | Half-minimum (hm) imputation, QRILC |

Best Practice: First, filter out lipids with a high percentage of missing values (e.g., >35%). Then, investigate the likely mechanism before choosing an imputation strategy. kNN-based methods often perform well for MCAR and MAR, while replacing with a percentage of the lowest concentration is recommended for MNAR [24].

Experimental Protocol for Improved Lipid Identification

This detailed methodology is adapted from a comprehensive UHPLC-MS/MS study focused on signaling lipids [7].

Sample Preparation

- Extraction: Use a fast, simultaneous extraction protocol for polar signaling lipids. The optimized method enables efficient recovery of diverse classes including oxylipins, lysophospholipids, and endocannabinoids.

- Internal Standards: Add a stable isotope-labeled internal standard mixture (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX) to correct for extraction efficiency and matrix effects. A final concentration of 16 ng/mL is typical [4].

- Prevention of Oxidation: Supplement extraction solvents with 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) [4].

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis

- Chromatography:

- Column: Luna Omega 3 µm polar C18 (50 × 0.3 mm, 100 Å)

- Flow Rate: 8 µL/min (microflow)

- Mobile Phase: Eluent A (60:40 acetonitrile/water), Eluent B (85:10:5 isopropanol/water/acetonitrile), both with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient: 40% B to 99% B over 0.5-5 min, hold for 5 min, re-equilibrate [4]

- Mass Spectrometry:

- Instrument: ZenoToF 7600 mass spectrometer

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI), positive mode

- Acquisition: Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or targeted MS/MS for enhanced sensitivity

Method Validation Characterize the method using the following parameters [7]:

- Linearity, Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

- Extraction recovery and matrix effects

- Intra-day and inter-day precision

- Validate quantification in a standardized matrix like NIST SRM 1950 human plasma

Experimental Workflow for Accurate Lipid Identification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow essential for overcoming reproducibility challenges in lipid identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Standards for Lipidomics Research

| Item | Function & Application | Example & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative MS Internal Standard | Deuterated lipid mixture for signal correction and quantification. | Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX; concentration: 16 ng/mL [4] |

| Standard Reference Material | Standardized matrix for method validation and inter-laboratory comparison. | NIST SRM 1950 - Human Plasma [24] [7] |

| Antioxidant Additive | Prevents oxidation of unsaturated lipids during extraction. | 0.01% Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) in extraction solvent [4] |

| Chromatography Column | Stationary phase for UHPLC separation of complex lipid extracts. | Polar C18 column (e.g., Luna Omega, 3µm, 50x0.3mm) [4] |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Promotes protonation and efficient ionization in positive ESI mode. | 10 mM Ammonium Formate + 0.1% Formic Acid [4] |

Data Analysis and Statistical Processing Workflow

After obtaining identified lipids, a robust statistical pipeline is crucial for biological interpretation. The following diagram outlines the key steps.

FAQ: What are the best statistical practices for identifying differentially abundant lipids?

A step-wise approach is recommended [24] [25]:

- Start with Dimensionality Reduction: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize overall data structure, identify outliers, and detect batch effects.

- Univariate Testing: Apply t-tests (for two groups) or ANOVA (for multiple groups) to find lipids with significant abundance changes.

- Critical Step: Correct for multiple testing using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to reduce false positives.

- Multivariate Analysis: Employ Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) or Orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) to find lipid combinations that best discriminate sample groups.

- Pathway Analysis: Use Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) or Pathway Topology-based Analysis (PTA) in tools like MetaboAnalyst or KEGG to interpret results biologically [25].

FAQ: How can I improve the confidence of my lipid identifications without expensive hardware?

- Leverage Retention Time: Use retention time as a reproducible identifier. Machine learning models trained on your specific LC method can predict lipid retention times, helping flag identifications with anomalous tR values [4].

- Mandatory Manual Curation: There is no substitute for manually inspecting the MS2 spectra for top-hit identifications, especially for potential biomarkers. Check for key fragment ions and ensure the isotopic pattern matches expectations [4].

- Standardized Reporting: Adhere to the Lipidomics Standards Initiative (LSI) guidelines for reporting minimum information, which helps improve reproducibility and allows others to assess the confidence of your reported identifications [4].

Optimized Workflows: From Sample Preparation to Advanced Detection Strategies

Lipid extraction is a foundational step in sample preparation for lipidomics, profoundly impacting the accuracy and reliability of subsequent UHPLC-MS/MS analysis. The structural diversity of lipids, encompassing variations in backbone length, unsaturations, and functional groups, imposes significant constraints on extraction efficiency [26]. No single extraction method is universally capable of isolating the entire lipidome, and the choice of protocol introduces a specific bias, determining which lipid classes are detectable and quantifiable in downstream analyses [26] [27]. This evaluation, framed within a thesis on improving lipid identification accuracy, compares monophasic and biphasic extraction protocols. It provides troubleshooting guidance to help researchers select and optimize methods for their specific biological matrices and research objectives, thereby enhancing data quality in drug development and clinical research.

FAQ: Core Principles and Method Selection

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between monophasic and biphasic extraction systems?

- Biphasic systems (e.g., Folch, MTBE) use immiscible aqueous and organic solvents to create two separate phases. Lipids partition into the organic phase based on their hydrophobicity, while hydrophilic impurities remain in the aqueous phase, resulting in cleaner extracts [26] [28].

- Monophasic systems (e.g., Alshehry, IPA) use a single phase or miscible solvents for protein precipitation and lipid solubilization. They are typically faster, simpler, and avoid the need for phase separation, making them more amenable to high-throughput workflows [27] [29].

Q2: Why is there no single "best" lipid extraction method?

The wide structural diversity of lipids means that any given solvent system has varying affinities for different lipid classes. A method that excels at extracting non-polar triglycerides (TGs) may perform poorly for polar lipids like acylcarnitines (AcCa) [26]. The optimal method is therefore dependent on the target lipid classes and the biological matrix (e.g., plasma, liver, brain) [27].

Q3: Are chloroform-free methods reliable?

Yes. Modern methods like the MTBE (Matyash) and BUME protocols replace toxic chloroform with safer solvents, forming an organic top layer for easier collection [27]. The Alshehry (1-butanol/methanol) monophasic method has also been shown to be as effective as Folch for most lipid classes and superior for some polar lipids, making it a safer and more environmentally friendly option [28].

Q4: How can I improve the extraction of very polar or very non-polar lipids?

Coverage across the polarity scale remains a challenge. Recent advances include optimized monophasic solvent mixtures. For instance, a protocol using MeOH/MTBE/IPA (1.3:1:1, v/v/v) demonstrated close to 100% recovery for both polar acylcarnitines and non-polar triglycerides [29]. Integrating mechanical cell disruption, such as bead homogenization, can further enhance yields, particularly for intracellular lipids [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Emulsion Formation During Liquid-Liquid Extraction

- Cause: Emulsions are common in samples rich in surfactant-like compounds, such as phospholipids, free fatty acids, triglycerides, and proteins [30].

- Solutions:

- Prevention: Gently swirl the separatory funnel instead of shaking it vigorously. This reduces agitation while maintaining sufficient surface area for extraction [30].

- Disruption:

- Salting Out: Add brine or salt water to increase the ionic strength of the aqueous layer, forcing surfactant-like molecules into one phase [30].

- Filtration: Pass the emulsion through a glass wool plug or a specialized phase separation filter paper [30].

- Centrifugation: Use centrifugation to isolate the emulsion material in the residue [30].

- Solvent Adjustment: Add a small amount of a different organic solvent to alter the solvent properties and break the emulsion [30].

- Alternative Technique: For samples prone to emulsions, consider Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE), which minimizes emulsion formation by using a solid support to create the interface for extraction [30].

Problem: Low Recovery of Specific Lipid Classes

- Cause: Inherent bias of the extraction solvent system.

- Solutions:

- Identify the Bias: Consult comparative studies. For example, the MTBE method is known to have significantly lower recoveries for lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE), and sphingomyelins (SM) compared to other methods [27].

- Use Internal Standards: Add a comprehensive set of stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-ISTDs) prior to extraction. This corrects for losses during extraction and ionization, improving quantitative accuracy [27] [29].

- Optimize the Protocol: For polar lipids, consider monophasic methods like Alshehry or the optimized MeOH/MTBE/IPA mixture, which show improved recovery for acylcarnitines and other polar species [29] [28].

Problem: Poor Method Reproducibility

- Cause: Inconsistent sample handling or suboptimal protocols.

- Solutions:

- Standardize Handling: Ensure all steps (vortexing, centrifugation, phase collection) are performed consistently and for specified durations.

- Select Robust Methods: Some methods, like IPA and EtOAc/EtOH (EE), have been reported to show poor reproducibility in certain tissues [27]. The Folch method generally shows high reproducibility across multiple tissue types [27].

- Automate Where Possible: Transitioning to high-throughput techniques like SLE or using automated pipetting robots can significantly improve reproducibility by reducing manual error [29] [30].

Quantitative Comparison of Extraction Methods

The following tables summarize experimental data from key studies to aid in method selection.

Table 1: Extraction Efficiency of Different Methods Across Mouse Tissues [27]

| Extraction Method | Solvent System | Type | Optimal Tissue(s) | Lipid Classes with Notably Low Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folch | CHCl₃/MeOH/H₂O | Biphasic | Pancreas, Spleen, Brain, Plasma | - |

| MTBE (Matyash) | MTBE/MeOH/H₂O | Biphasic | - | LPC, LPE, AcCa, SM, Sphingosines |

| BUME | BuOH/MeOH/Heptane/EtOAc | Biphasic | Liver, Intestine | - |

| MMC | MeOH/MTBE/CHCl₃ | Monophasic | Liver, Intestine | - |

| IPA | Isopropanol | Monophasic | - | Poor reproducibility in most tissues |

| EE | EtOAc/EtOH | Monophasic | - | Poor reproducibility in most tissues |

Table 2: Performance of an Advanced Monophasic Protocol for Platelet Lipidomics [29]

| Parameter | Performance | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent System | MeOH/MTBE/IPA (1.3:1:1, v/v/v) | Monophasic |

| Cell Disruption | Bead Homogenizer | Optimal for efficiency |

| Extraction Recovery | ~100% for AcCa (polar) and TGs (apolar) | Wide polarity coverage |

| Reproducibility | High | Suitable for large-scale studies |

| Key Advantages | No phase separation, no halogenated solvents, fast, easily automated | Eco-friendly and high-throughput |

Experimental Protocols for Key Extraction Methods

- Homogenization: Homogenize the sample (e.g., 10 µL plasma) in a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of CHCl₃:MeOH (e.g., 200 µL:100 µL).

- Partitioning: Add 0.2 volumes of water or saline solution (e.g., 60 µL). Vortex thoroughly and centrifuge to achieve phase separation.

- Collection: Carefully collect the lower, lipid-containing organic layer (CHCl₃ phase), avoiding the protein disc at the interface.

- Evaporation: Evaporate the solvent under a stream of nitrogen or in a vacuum concentrator.

- Reconstitution: Redissolve the lipid extract in a compatible solvent (e.g., MeOH/MTBE 1:1) for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis.

- Mixing: Add sample to MeOH (volume sample dependent).

- Extraction: Add MTBE (e.g., 3.5 times the sample volume). Vortex and incubate.

- Partitioning: Add water (e.g., 0.9 times the sample volume) to induce phase separation. Centrifuge.

- Collection: Collect the upper, lipid-containing MTBE layer.

- Evaporation and Reconstitution: Evaporate the solvent and reconstitute as in Folch method.

- Precipitation: To the sample (e.g., 10 µL plasma), add a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of 1-butanol:MeOH (e.g., 190 µL) containing internal standards.

- Vortex and Centrifuge: Vortex mix thoroughly and centrifuge. A white protein pellet will form at the bottom of the tube.

- Collection: Collect the single-phase supernatant, which contains the extracted lipids.

- Analysis: The supernatant can be directly injected or diluted for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Lipid Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-ISTDs) | Correct for extraction efficiency, ionization suppression, and matrix effects; essential for quantification [27] [28]. | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX (Avanti) |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Chloroform substitute in biphasic extractions; forms top organic layer [27] [29]. | - |

| 1-Butanol | Solvent for monophasic extractions; high boiling point requires careful evaporation [27] [28]. | - |

| Isopropanol (IPA) | Solvent for monophasic protein precipitation; can show variable reproducibility [27] [29]. | - |

| Bead Homogenizer | Mechanical cell disruption method to enhance the release of intracellular and organellar lipids [29]. | - |

| C8 or C18 UHPLC Column | Reversed-phase chromatography column for separating complex lipid mixtures prior to MS analysis [31]. | - |

Workflow and Decision Diagrams

Method Selection and Optimization Workflow

Troubleshooting Experimental Issues

How can I minimize matrix effects and ion suppression when analyzing complex lipid samples?

Matrix effects, particularly ion suppression, are major challenges in UHPLC-MS/MS analysis of complex biological samples like lipids. These effects occur when co-eluting compounds interfere with the ionization of your target analytes, leading to inaccurate quantification [32].

Primary Causes and Solutions:

- Source of Interference: Phospholipids from biological matrices are a primary cause of ion suppression, especially in electrospray ionization (ESI) [32]. Sample preparation using protein precipitation with acetonitrile, while simple, does not effectively remove these phospholipids [32].

- Sample Preparation: Employ liquid-liquid extraction techniques, such as a modified Folch extraction (using chloroform and methanol), for more effective cleanup and to reduce matrix components [15] [14].

- Chromatographic Resolution: Improve the separation of lipids to prevent co-elution of interferents with your analytes. This can be achieved by optimizing the mobile phase gradient and selecting appropriate stationary phases [32] [14].

- Internal Standards: Use stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) for each analyte. This is the most reliable way to account for the variability caused by matrix effects, though it may not fully restore lost sensitivity [32].

What is the optimal strategy for initial UHPLC scouting gradient development?

A well-designed scouting gradient is the most efficient way to start method development, providing rich information on the chromatographic behavior of your sample and guiding subsequent optimization [33].

Scouting Gradient Protocol:

- Column Selection: Begin with a 50-100 mm x 2.1 mm UHPLC column packed with sub-2 µm or superficially porous particles (~2.7 µm) for high efficiency [34] [14]. A C18 phase is a standard starting point for reversed-phase lipid analysis.

- Mobile Phase: For reversed-phase, use water (or a buffered aqueous solution) as mobile phase A and a strong organic solvent like acetonitrile or a 1:1 mixture of acetonitrile-isopropanol as mobile phase B [15] [14]. The addition of additives such as 1 mM ammonium acetate or 0.1% formic acid can improve ionization in MS detection [15].

- Gradient Design:

- Initial Composition (ϕi): 2-5% B to ensure initial retention without causing stationary phase "dewetting" [33].

- Final Composition (ϕf): 80-95% B, ensuring buffer salts remain soluble [33].

- Gradient Time (tg): A calculated starting point for a 50 mm column is around 4 minutes at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, targeting a retention factor (k) of ~5 for analytes [33]. The formula for this calculation is: tg = (k × Vm × Δϕ) / (0.15 × F), where Vm is the column dead volume and F is the flow rate.

Table 1: Scouting Gradient Parameters for a 50 x 2.1 mm Column

| Parameter | Recommended Starting Condition | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Column Temperature | 50°C [15] | Enhances elution of late-eluting lipids and improves peak shape. |

| Flow Rate | 0.4 - 0.5 mL/min [15] [33] | Balances analysis speed and column efficiency. |

| Injection Volume | 1-5 µL (approx. 1% of column void volume) [34] | Prevents column overload and peak distortion. |

| Gradient Time | 4-12 minutes [15] [33] | Allows for sufficient separation of a wide range of lipid classes. |

How do I interpret the results from my initial scouting run to decide on isocratic or gradient elution?

The chromatogram from your scouting gradient provides critical information for selecting the final elution mode. Apply the "25/40% rule" to make this decision [33].

Decision Workflow:

- Measure the Elution Window: Calculate the time span from the first eluting peak of interest to the last.

- Apply the Rule:

- If the span is >40% of the gradient time: Developing a gradient elution method is most appropriate. An isocratic method in this case would result in poor peak shapes for early eluters and impractically long analysis times for late eluters [33].

- If the span is <25% of the gradient time: An isocratic elution method can be developed, which often yields sharper peaks and simpler instrument setup [33].

- If the span is between 25% and 40%: Either approach may be viable, and the choice depends on other factors like required resolution and analysis time.

The following diagram illustrates this logical decision-making process based on your scouting run data.

What column characteristics most significantly impact the separation of lipid isomers?

A "C18" column is not just a C18. Several physicochemical properties of the stationary phase critically influence selectivity, especially for challenging separations like lipid isomers [34].

Key Column Properties:

- Bonded Phase Chemistry: Variations in % carbon loading and the type of end-capping can create dramatic differences in selectivity, even among columns with the same nominal chemistry (e.g., C18) [34].

- Particle Structure:

- Fully Porous Sub-2 µm Particles: Offer high efficiency and are the standard for UHPLC, but generate high backpressure [32] [35].

- Superficially Porous Particles (SPP, ~2.7 µm): Provide efficiency comparable to sub-2 µm particles but at lower pressures. They are robust and less prone to clogging, making them an excellent choice for complex biological samples [34].

- Particle Size: Smaller particles (e.g., <2 µm) provide higher efficiency and resolution, which is essential for separating lipids with subtle structural differences [32] [14].

Table 2: Stationary Phase Selection Guide for Lipid Analysis

| Stationary Phase Characteristic | Impact on Separation | Recommendation for Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | Smaller particles (<2 µm) increase efficiency and resolution [32]. | Essential for UHPLC to resolve complex lipid mixtures. |

| Particle Type | Superficially Porous Particles (SPP) offer high efficiency at lower backpressure [34]. | Excellent for method development; forgiving with complex samples. |

| Carbon Load & Endcapping | High carbon load and thorough endcapping impact retention and peak shape for polar compounds [34]. | Test different C18 columns from various manufacturers to find optimal selectivity. |

| Pore Size | Typical pore sizes of 100-130 Å are suitable for most lipids [35]. | Ensures good accessibility of lipid molecules to the stationary phase. |

How can I use advanced software and automation to accelerate UHPLC method development?

Automated tools leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) can drastically reduce the time and manual intervention required for method development [36].

Automated Workflow:

- Automated Screening: Software like ChromSword can automatically screen multiple columns and mobile phase combinations [36].

- Feedback-Controlled Optimization: An AI-based algorithm uses data from initial runs to model chromatographic behavior and automatically performs iterative injections, fine-tuning parameters like gradient slope and temperature with no analyst intervention [36].

- Broad Applicability: This approach has been successfully applied to diverse pharmaceutical modalities, including small molecules, peptides, and proteins, and can be adapted for lipid analysis [36].

The workflow for this automated, feedback-controlled method development is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for UHPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Item | Function in Lipidomics | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Internal Standards | Corrects for variability in sample prep, matrix effects, and instrument response [32] [14]. | Deuterated or 13C-labeled standards (e.g., LIPID MAPS quantitative standards). Use a standard for each lipid class analyzed. |

| Chloroform-Methanol Solvent System | For liquid-liquid extraction of a broad range of lipid classes from biological matrices (Folch or MTBE method) [15] [14]. | Classic 2:1 (v/v) ratio. MTBE-methanol is a safer alternative. |

| Ammonium Acetate/Formate | A volatile buffer salt and mobile phase additive compatible with MS. Promotes adduct formation ([M+Ac]-) in negative ion mode for better structural analysis [5] [15]. | Typically used at 1-10 mM concentration. |

| Formic Acid | A common mobile phase additive (0.1%) for positive ion mode ESI-MS to promote protonation [M+H]+ of analytes [15]. | Enhances ionization efficiency. |

| Acetonitrile-Isopropanol Mix | A strong organic mobile phase (B-solvent) for reversed-phase UHPLC, effective for eluting very non-polar lipids like triacylglycerols (TGs) [15] [14]. | A 1:1 mixture is often used to cover a wide polarity range. |

In UHPLC-MS/MS research, the selection of an appropriate mass spectrometry acquisition technique is paramount for achieving high-confidence lipid identification and accurate quantification. The choice between targeted methods (MRM, PRM) and untargeted approaches (DIA) presents a fundamental trade-off between quantification performance and analyte coverage [37] [38]. This technical resource center provides detailed methodologies and troubleshooting guidance to help researchers optimize these advanced acquisition techniques specifically for lipidomics applications, with the overarching goal of improving data quality and reliability in complex biological samples.

Core Principles of MS/MS Acquisition Techniques

Mass spectrometry acquisition modes are defined by how instruments isolate and fragment precursor ions to generate identifying spectra.

- MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring): Performed on triple quadrupole instruments, MRM monitors predefined precursor-to-product ion transitions. The first quadrupole (Q1) filters a specific precursor ion, which is fragmented in the collision cell (Q2), and the third quadrupole (Q3) selectively transmits predefined product ions [38]. This offers exceptional sensitivity and specificity for targeted quantification.

- PRM (Parallel Reaction Monitoring): A high-resolution targeted technique where Q1 isolates specific precursor ions, which are fragmented, and all product ions are detected in a high-resolution mass analyzer (e.g., Orbitrap) [38] [39]. This provides high selectivity while retaining full fragment ion spectra.

- DIA (Data-Independent Acquisition): An untargeted approach where the mass spectrometer cycles through consecutive, wide mass isolation windows (e.g., 20-25 Da), fragmenting all precursors within each window [37] [38]. This provides comprehensive MS2 data for all detectable analytes, enabling retrospective analysis.