Advancing Binding Pose Prediction: Current Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions in Computational Drug Discovery

Accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding poses is crucial for structure-based drug design but remains challenging due to limitations in sampling algorithms, scoring functions, and data biases.

Advancing Binding Pose Prediction: Current Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions in Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

Accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding poses is crucial for structure-based drug design but remains challenging due to limitations in sampling algorithms, scoring functions, and data biases. This article provides a comprehensive overview of current computational methods for improving binding pose prediction, covering foundational concepts, advanced methodologies including hybrid docking-machine learning approaches, strategies for troubleshooting common issues, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing recent advances from foundational research to practical applications, we offer researchers and drug development professionals actionable insights to enhance prediction accuracy, address generalization challenges, and ultimately accelerate therapeutic development across diverse target classes including metalloenzymes and RNA.

The Fundamental Challenges in Binding Pose Prediction: Why Accuracy Matters in Drug Discovery

The Critical Role of Binding Pose Prediction in Structure-Based Drug Design

FAQs: Understanding Binding Pose Prediction

What is binding pose prediction and why is it critical in drug discovery?

Binding pose prediction is a computational method that predicts how a small molecule (ligand) will orient itself and fit into the three-dimensional structure of a target protein [1]. It is critical because the correct binding geometry determines the strength and specificity of the drug-target interaction. An accurate pose is the foundation for reliable binding affinity prediction and rational drug optimization [2]. Inaccurate predictions can mislead entire drug discovery projects, wasting significant time and resources.

What are the most common reasons for inaccurate binding pose predictions?

Inaccurate predictions often result from a combination of factors:

- Protein Flexibility: Many models treat proteins as rigid bodies, but in reality, side chains and even backbone segments can move upon ligand binding, a phenomenon known as "induced fit" [1].

- Inadequate Scoring Functions: The mathematical functions used to rank poses may not accurately capture all the complex physics of molecular interactions, such as solvent effects and specific halogen bonds [3].

- Limited and Biased Data: Many benchmarking datasets lack the diversity and size needed to train robust models, and methods are often validated on targets similar to those they were trained on, leading to over-optimistic performance [3] [1].

How can I validate the accuracy of a predicted binding pose?

Without an experimental structure, pose validation is inferential. A multi-pronged strategy is recommended:

- Consistency Across Methods: Check if multiple, independent docking algorithms or scoring functions produce a similar pose.

- Structural Rationality: Manually inspect the pose for expected interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds with key residues, filling of hydrophobic pockets) and the absence of steric clashes [2].

- Experimental Correlation: If available, use structure-activity relationship (SAR) data from related compounds. A good pose should explain why active compounds bind and inactive ones do not.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Run short MD simulations to assess the stability of the predicted pose over time. An unstable pose that quickly drifts is likely incorrect [4].

What is the difference between pose prediction and binding affinity prediction?

These are two distinct but related tasks. Pose Prediction is a geometric problem focused on finding the correct orientation and conformation of the ligand in the binding pocket. Binding Affinity Prediction (or scoring) is an energetic problem that estimates the strength of the interaction once the pose is known [1]. A method can correctly identify the pose but poorly estimate its affinity, and vice versa. Both are essential for successful Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD).

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Consistently Inaccurate Poses for a Flexible Target

Problem: Your target protein has a known flexible loop in the binding site, and your docking runs produce poses that clash with this loop or are sterically impossible.

Solution: Implement a protocol that accounts for protein flexibility.

Methodology:

- Generate an Ensemble of Protein Structures:

- Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to generate multiple "snapshots" of the protein structure, capturing the movement of the flexible loop [4].

- Alternatively, if crystal structures are available, create an ensemble from structures bound to different ligands.

- Perform Ensemble Docking:

- Dock your ligand library against each structure in the protein ensemble.

- Software: AutoDock Vina, Schrödinger Glide [5].

- Consensus Analysis:

- Analyze the results to find poses that are favorable across multiple protein conformations.

- A pose that scores well against several structures is more likely to be correct and represent a viable binding mode.

Issue: Poor Correlation Between Predicted Affinity and Experimental Activity

Problem: The compounds your model predicts to have the best binding affinity show weak or no activity in laboratory assays.

Solution: Augment traditional docking scores with machine learning and simulation-based refinement.

Methodology:

- Initial Pose Generation:

- Use a standard docking tool (e.g., AutoDock Vina) to generate multiple candidate poses for each compound [4].

- Machine Learning Re-scoring:

- Energetic Refinement with MD:

- Take the top-ranked poses and run short molecular dynamics simulations to relax the structure and account for full flexibility and solvent effects.

- Calculate binding free energies using more rigorous methods (e.g., MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA) on the stabilized simulations [4].

- Validation:

- Prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing based on this multi-stage scoring process, which should show improved correlation with experimental results.

Quantitative Data on Performance and Methods

Table 1: Key Metrics for Evaluating Pose Prediction Accuracy

| Metric | Formula / Definition | Interpretation | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | $$RMSD = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} (r{i,pred} - r_{i,ref})^2}$$ | Measures the average distance between atoms in a predicted pose and a reference (experimental) pose. | < 2.0 Å is typically considered a correct prediction. |

| Success Rate (within 2Å) | $$\frac{\text{Number of ligands with RMSD < 2Å}}{\text{Total number of ligands}} \times 100\%$$ | The percentage of ligands in a test set for which a method successfully predicts a pose. | Higher is better. Top methods may achieve >70-80% on standard benchmarks [3]. |

| Heavy Atom RMSD | Same as RMSD, but calculated only using non-hydrogen atoms. | Provides a more stringent measure of pose accuracy by focusing on the molecular scaffold. | Similar threshold to overall RMSD. |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Pose Prediction Methodologies

| Method Type | Description | Representative Tools | Key Parameters to Optimize |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Docking & Scoring | Uses a pre-defined scoring function and search algorithm to rapidly generate and rank poses. | AutoDock Vina [5], Glide [5], MOE [5] | Search space (grid box size), exhaustiveness, number of output poses. |

| Machine Learning-Augmented | Employs ML models trained on structural data to improve pose selection and affinity estimation. | DiffDock [2], AlphaFold3 [2] | Training dataset quality, feature selection, model type (e.g., classifier vs. regressor). |

| Molecular Dynamics-Based | Uses physics-based simulations to refine poses and calculate binding energies, accounting for flexibility. | GROMACS [5], AMBER [5], NAMD | Simulation time (ns), force field choice, water model, thermostat/barostat settings. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: A Robust Workflow for Validating Novel Inhibitors

This protocol integrates multiple computational techniques to identify and validate binding poses for novel inhibitors, as demonstrated in a recent study targeting the αβIII tubulin isotype [4].

Objective: To identify natural compounds that bind to the 'Taxol site' of a drug-resistant protein target.

Workflow:

- Target Preparation:

- Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein from experiments (PDB) or generate it via homology modeling if not available (e.g., using Modeller) [4].

- Prepare the protein structure: add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and remove crystallographic water molecules.

- Ligand Library Preparation:

- Obtain a library of candidate compounds (e.g., 89,399 natural compounds from the ZINC database) [4].

- Prepare ligands: generate 3D conformations, minimize energy, and convert to appropriate format (e.g., PDBQT).

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening:

- Use a docking tool (e.g., AutoDock Vina) to screen the entire library against the binding site of interest [4].

- Parameters: Define a grid box encompassing the binding pocket. Set exhaustiveness to ensure adequate sampling.

- Retain the top 1,000 hits based on binding energy for further analysis.

- Machine Learning Classification:

- Generate molecular descriptors for the top hits and a training set of known active/inactive compounds (using PaDEL-Descriptor) [4].

- Train a supervised ML classifier (e.g., using 5-fold cross-validation) to distinguish active from inactive molecules.

- Apply the classifier to the top hits to identify a shortlist of ~20 predicted active compounds.

- Pose Validation and Stability with MD:

- Subject the shortlisted ligand-protein complexes to molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns) using a package like GROMACS [4].

- Analysis:

- Calculate RMSD of the protein and ligand to assess complex stability.

- Calculate RMSF to understand residual flexibility.

- Calculate Radius of Gyration (Rg) and SASA to monitor compactness and solvent exposure.

- A stable pose will show low, stable RMSD values for the ligand after an initial equilibration period.

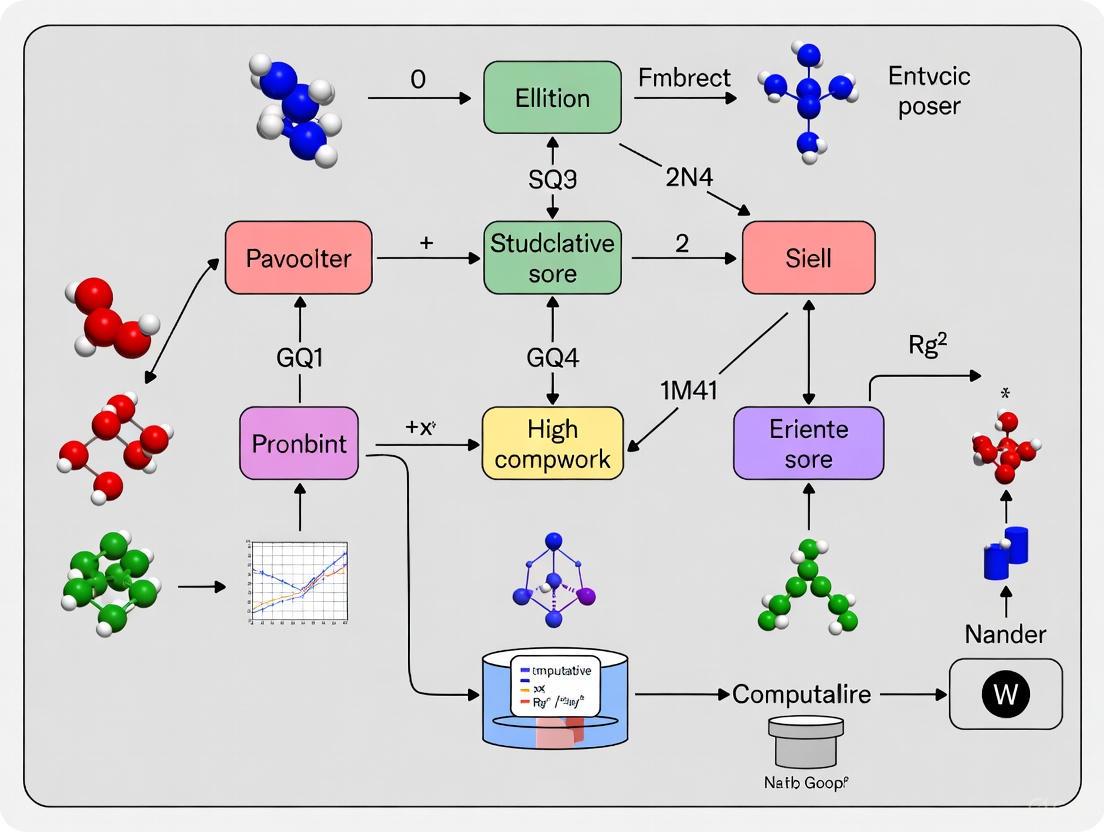

Signaling Pathways, Workflows & Logical Diagrams

Diagram 1: Binding Pose Prediction and Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Inaccurate Predictions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Databases for Pose Prediction

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Software | Performs molecular docking to predict binding poses and affinities [2] [5]. | Initial high-throughput virtual screening of large compound libraries. |

| GROMACS/AMBER | Software | Molecular dynamics simulation packages used for refining poses and assessing stability [5] [4]. | Running 100ns simulations to see if a docked pose remains stable. |

| AlphaFold3 / DiffDock | Software | Next-generation ML models for predicting protein-ligand structures and binding poses [2] [1]. | Generating a putative pose for a novel ligand where no template exists. |

| RDKit | Software | Cheminformatics toolkit for analyzing molecules, calculating descriptors, and building ML models [5] [4]. | Converting SMILE strings to 3D structures and generating molecular features for a classifier. |

| ZINC Database | Database | A public resource containing commercially available compounds for virtual screening [4]. | Sourcing a diverse library of natural products for a screening campaign. |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | The single worldwide repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of experimental protein structures for docking and method benchmarking. |

| DUD-E Server | Database | Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced; generates decoy molecules for benchmarking virtual screening methods [4]. | Creating a non-biased training/test set for a machine learning model. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do my standard molecular docking programs produce inaccurate results for metalloenzyme inhibitors?

Standard docking programs often fail to accurately predict binding poses for metalloenzyme inhibitors because their general scoring functions do not properly handle the quantum mechanical effects and specific coordination geometries of metal ions [6]. A study comparing common docking programs found that while some could predict correct binding geometries, none were successful at ranking docking poses for metalloenzymes [6]. For reliable results, use specialized protocols that integrate quantum mechanical calculations or explicitly define metal coordination geometry constraints.

Q2: How does the coordination geometry of different metal ions affect catalytic activity in metalloenzymes?

Metal ion coordination geometry directly modulates catalytic efficacy by influencing substrate binding, conversion to product, and product binding [7]. Research on human carbonic anhydrase II demonstrates that non-native metal substitutions cause dramatic activity changes: Zn²⁺ (tetrahedral, 100% activity), Co²⁺ (tetrahedral/octahedral, ~50%), Ni²⁺ (octahedral, ~2%), and Cu²⁺ (trigonal bipyramidal, 0%) [7]. The geometry affects steric hindrance, binding modes, and the ability to properly position substrates for nucleophilic attack.

Q3: What percentage of enzymes are metalloenzymes, and what does this mean for drug discovery?

Approximately 40-50% of all enzymes require metal ions for proper function, yet only about 7% of FDA-approved drugs target metalloenzymes [6] [8]. This significant gap between the prevalence of metalloenzymes in biology and their representation as drug targets highlights both a challenge and a substantial opportunity for therapeutic development [8].

Q4: Can AlphaFold2 models reliably predict binding pockets for metalloenzyme drug discovery?

While AlphaFold2 (AF2) models capture binding pocket structures more accurately than traditional homology models, ligand binding poses predicted by docking to AF2 models are not significantly more accurate than traditional models [9]. The typical difference between AF2-predicted binding pockets and experimental structures is nearly as small as differences between experimental structures of the same protein with different ligands bound [9]. However, for precise metalloenzyme targeting, experimental structures remain superior for docking accuracy.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Accuracy in Predicting Metal-Binding Pharmacophore (MBP) Poses

Table: Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) Values for Computationally Predicted vs. Experimental MBP Poses [6]

| Metalloenzyme Target | PDB Entry | Predicted RMSD (Å) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Carbonic Anhydrase II (hCAII) | 2WEJ | 0.49 | Accurate tetrahedral Zn²⁺ coordination |

| Human Carbonic Anhydrase II (hCAII) | 6RMP | 3.75 | Reversed orientation of keto hydrazide moiety |

| Jumonji-domain Histone Lysine Demethylase (KDM) | 2VD7 | 0.22 | Distal docking without active-site constraint |

| Influenza Virus PAN Endonuclease | 4MK1 | 1.67 | Dinuclear Mn²⁺/Mg²⁺ coordination |

Solutions:

- Implement Hybrid QM/MM Methods: Combine density functional theory (DFT) calculations for the metal-binding region with molecular mechanics for the protein environment to better model coordination chemistry [6].

- Apply Active Site Constraints: Define the metal coordination geometry as a constraint during docking. For example, set tetrahedral geometry for Zn²⁺ in hCAII or octahedral for Fe²⁺ in KDMs [6].

- Use Multiple Scoring Functions: Rescore docking poses with different scoring functions (e.g., ChemPLP followed by GoldScore) to improve pose selection [6].

Problem: Accounting for Metal-Dependent Conformational Changes in Active Sites

Solutions:

- Consider Metal Ion Electrostatic Effects: Metal ions can exert long-range (~10 Å) electrostatic effects that restructure water networks in active sites [7]. Incorporate explicit water molecules in docking simulations.

- Model Multiple Coordination States: For metal ions like Co²⁺ that transition between tetrahedral and octahedral geometries during catalysis, model both coordination states [7].

- Utilize Molecular Dynamics with Metal Parameters: Perform molecular dynamics simulations with specialized parameters for metal ions to capture dynamic coordination changes [10].

Experimental Protocols for Improved Binding Pose Prediction

Protocol 1: Hybrid DFT/Docking Approach for Metal-Binding Pharmacophores

This protocol combines quantum mechanical calculations with genetic algorithm docking for accurate MBP pose prediction [6].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Metalloenzyme Docking

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol | Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Software | DFT optimization of MBP fragments | Generates accurate 3D structures and charge distributions for metal-chelating groups |

| GOLD (Genetic Optimization for Ligand Docking) | Genetic algorithm docking with metal constraints | Handles metal coordination geometry constraints during pose sampling |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Structure preparation and ligand elaboration | Removes crystallographic waters, adds hydrogens, elaborates MBP fragments into full inhibitors |

| PDB Protein Structures | Experimental reference structures | Source of metalloenzyme structures with different metal ions and coordination geometries |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- MBP Fragment Preparation: Generate three-dimensional structure of the metal-binding pharmacophore fragment and optimize its geometry using DFT calculations with Gaussian [6].

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain the metalloenzyme structure from the PDB. Remove water molecules and other small molecules, add hydrogen atoms, and protonate side chains at physiological pH using MOE [6].

- Define Metal Coordination Geometry: Set the metal ion coordination geometry based on experimental data (e.g., tetrahedral for Zn²⁺, octahedral for Fe²⁺) [6].

- MBP Docking: Dock the optimized MBP fragment using GOLD with a genetic algorithm, keeping the protein structure rigid while allowing ligand flexibility [6].

- Pose Evaluation and Rescoring: Evaluate binding poses during docking using ChemPLP scoring function, then rescore top poses with GoldScore function [6].

- Ligand Elaboration: Manually elaborate the docked MBP fragment into the complete inhibitor structure using MOE, while keeping the MBP pose fixed [6].

- Energy Minimization: Perform final energy minimization of the complete inhibitor while maintaining the metal-coordinating atoms in their docked positions [6].

Protocol 2: Markov State Model Approach for Binding Pathway Prediction

This protocol uses distributed molecular dynamics simulations and Markov State Models to predict ligand binding pathways and poses, particularly useful when experimental structures are unavailable [10].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Generate Initial Ensembles: Create diverse starting structures including unbound states, near-bound states, and docking-predicted bound states [10].

- Distributed MD Simulations: Run multiple independent molecular dynamics simulations on cloud computing architectures to sample binding events [10].

- Build Markov State Models: Cluster simulation data by protein-aligned ligand RMSD and build transition matrices between states [10].

- Adaptive Sampling: Seed new simulations from under-sampled MSM states to improve binding event sampling [10].

- Equilibrium Population Analysis: Rank metastable ligand states by equilibrium population derived from MSM transition matrices [10].

- Convergence Evaluation: Monitor convergence of top populated poses over simulation time using RMSD to reference structures [10].

- Pathway Analysis: Use transition path theory to identify high-probability binding pathways and intermediate states [10].

Key Technical Considerations for Metalloenzyme Targeting

Understanding Metal Coordination Geometry Effects

Table: Impact of Metal Ion Substitution on Carbonic Anhydrase II Catalysis [7]

| Metal Ion | Coordination Geometry | Relative Activity | Key Structural Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn²⁺ | Tetrahedral | 100% (Native) | Optimal geometry for CO₂ binding and nucleophilic attack |

| Co²⁺ | Tetrahedral/Octahedral | ~50% | Transition between geometries; strong bidentate HCO₃⁻ binding |

| Ni²⁺ | Octahedral | ~2% | Stable octahedral geometry; inefficient HCO₃⁻ dissociation |

| Cu²⁺ | Trigonal Bipyramidal | 0% | Severe steric hindrance; distorted geometry prevents catalysis |

Best Practices for Computational Methods

- Select Appropriate Metal Parameters: Use force field parameters specifically developed for metalloenzymes that accurately represent metal coordination chemistry.

- Validate with Experimental Data: Compare computational predictions with available crystal structures and kinetic data to assess method accuracy [6] [7].

- Account for Metal Ion Identity: Recognize that different metal ions (even with similar properties) can yield dramatically different activities due to coordination geometry preferences [7].

- Consider Long-Range Electrostatic Effects: Incorporate the influence of metal ions on water networks and proton transfer pathways beyond the immediate coordination sphere [7].

- Utilize Multiple Approach Validation: Combine different computational methods (DFT, docking, MD) to cross-validate predictions and improve reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the most common reasons for poor model performance on apo-form RNA structures? Poor performance on apo-form RNA structures, which lack bound ligands, often stems from a model's over-reliance on features specific to holo-structures (those with bound ligands). The model may learn to recognize pre-formed binding pockets that are absent or significantly different in the apo form. To improve performance, ensure your training dataset includes representative apo-form RNA structures or use models specifically designed to handle RNA's structural flexibility, such as those employing multi-view learning to integrate features from different structural levels [11].

FAQ 2: How can I handle RNA's structural flexibility and multiple conformations in my predictions? RNA molecules are inherently flexible and can adopt multiple conformations. To address this:

- Use Multi-Conformational Data: Train or validate your models using dedicated datasets that include multiple conformations for the same RNA, such as the Conformational test set used in MVRBind development [11].

- Leverage Multi-View Learning: Implement frameworks that generate feature representations of RNA nucleotides across different structural levels (primary, secondary, and tertiary) and fuse these features to obtain a comprehensive representation that is more robust to conformational changes [11].

FAQ 3: My model performs well on single-chain RNA but fails on multi-chain complexes. What steps should I take? This failure often occurs because models trained only on single-chain data miss critical inter-chain interactions that can define binding sites in complexes.

- Graph-Based Representations: Adopt geometric deep learning frameworks like RNABind that encode the entire RNA complex structure as a graph. This allows the model to consider interactions between all chains [12].

- Rigorous Data Splitting: Use structure-based dataset splits during training and testing. This ensures that structurally similar RNAs do not appear across training and test sets, providing a more realistic assessment of your model's ability to generalize to new multi-chain complexes [12].

FAQ 4: What data preparation strategies can I use to overcome limited RNA-ligand interaction data? The scarcity of validated RNA–small molecule interaction data is a major challenge.

- Data Augmentation and Perturbation: Employ frameworks like RNAsmol that incorporate data perturbation and augmentation modeling. This can help balance the bias between known true negatives and the vast unknown interaction space, elucidating intrinsic binding patterns [13].

- Leverage Pre-trained Language Models: Utilize embeddings from RNA-specific large language models (LLMs) like ERNIE-RNA or RiNALMo. These models are pre-trained on vast corpora of RNA sequences and can capture contextual, structural, and functional information, enhancing generalization even with limited task-specific data [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Identification of Binding Sites on Flexible RNA Targets

Problem: Your computational model consistently fails to identify the correct binding nucleotides for RNA structures known to be highly flexible or for which only the apo structure is available.

Diagnosis and Solution: This issue typically arises from an inability to account for RNA's dynamic nature. A model trained only on static, holo-structures may not generalize well.

- Step 1: Verify the structural state of your RNA. Check if the RNA structure you are working with is a holo (ligand-bound) or apo (unbound) form. This information can often be found in the PDB file header or associated publication.

- Step 2: Apply a multi-view prediction model. Use a tool like MVRBind, which is explicitly designed to handle this by integrating information from primary, secondary, and tertiary structural views. The multi-view feature fusion module constructs graphs based on these different views, enabling the model to capture diverse aspects of RNA structure that remain conserved despite flexibility [11].

- Step 3: Consult the model's performance metrics on dedicated benchmark sets. Refer to the Apo test and Conformational test results from the MVRBind study to set realistic expectations for performance on such challenging targets [11].

Issue 2: Low Generalization Performance on Novel RNA Complexes

Problem: Your model achieves high accuracy during cross-validation on your training dataset but performs poorly when predicting binding sites for novel RNA complexes, especially those with low sequence or structural similarity to the training examples.

Diagnosis and Solution: The model has likely overfitted to specific patterns in your training data and lacks generalizable features.

- Step 1: Audit your dataset splitting strategy. Avoid random splits based solely on sequence, as they can lead to data leakage. Implement structure-based clustering splits, such as those used in the HARIBOSS dataset, where the training and test sets contain structurally dissimilar RNAs [12].

- Step 2: Integrate RNA language model embeddings. Replace or augment hand-crafted features with embeddings from pre-trained RNA LLMs like ERNIE-RNA or RiNALMo. These embeddings encode evolutionary and contextual information that can help the model reason about novel RNA structures [12].

- Step 3: Utilize geometric deep learning. Represent the RNA as a 3D graph, as done in RNABind. This allows the model to learn from the spatial arrangement of nucleotides, which is often more conserved and informative for binding than sequence alone, leading to better generalization on unseen complexes [12].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Model Performance on Apo vs. Holo RNA Structures

Objective: To rigorously evaluate a binding site prediction model's performance across different RNA conformational states.

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation:

- Acquire the Train60 (holo-form) and Test18 (holo-form) datasets from the RNAsite study [11].

- Construct an Apo test set by collecting apo-form RNA structures from the PDB and resources like SHAMAN. Remove redundant structures by clustering against the Train60 set using a permissive TM-score threshold to maximize structural diversity [11].

- Model Training: Train your prediction model on the Train60 dataset (holo-form only).

- Model Evaluation: Systematically test the trained model on three separate test sets:

- Test18: Measures performance on standard holo-form RNAs.

- Apo test: Measures performance on apo-form RNAs, highlighting flexibility handling.

- Conformational test: A subset of the Apo test containing RNAs with multiple conformations, specifically testing robustness to structural variation [11].

- Performance Analysis: Compare performance metrics (e.g., AUC, F1-score) across the different test sets. A significant drop in performance on the Apo and Conformational test sets indicates poor handling of RNA flexibility.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Model Generalization with Structural Splits

Objective: To assess a model's ability to predict binding sites for entirely novel RNA structural families.

Methodology:

- Dataset Preparation: Use the HARIBOSS dataset, a large collection of RNA-ligand complexes [12].

- Non-Redundant Clustering: Cluster all RNA structures in HARIBOSS based on structural similarity using a tool like TM-score, applying a strict threshold (e.g., 0.5) to define cluster membership [12].

- Structure-Based Splitting: Partition the clusters into non-overlapping training, validation, and test sets (e.g., Set1, Set2, Set3, Set4). This ensures no structurally similar RNA appears in more than one set, providing a rigorous test of generalization [12].

- Model Training and Testing: Train the model on the training set clusters and evaluate its final performance exclusively on the held-out test set clusters. This protocol prevents optimistic performance estimates and is considered a gold standard in the field [12].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Recent RNA-Ligand Binding Site Prediction Tools

The following table summarizes the reported performance of state-of-the-art methods on various benchmark datasets. Always verify the dataset and splitting strategy used when comparing numbers.

| Model / Method | Core Approach | Test Set (Type) | Reported Performance (AUC) | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVRBind [11] | Multi-view Graph Convolutional Network | Test18 (Holo) | 0.92 | Robust on apo and multi-conformation RNA |

| RNABind [12] | Geometric Deep Learning + RNA LLMs | HARIBOSS (Struct. Split) | 0.89 (with ERNIE-RNA) | Superior generalization to novel complexes |

| RNAsmol [13] | Data Perturbation & Augmentation | Unseen Evaluation | >0.90 (AUROC) | High accuracy without 3D structure input |

| RLBind [12] | Convolutional Neural Networks | Benchmark Set | ~0.85 (Baseline) | Models multi-scale sequence patterns |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Experiments

This table details key datasets and computational tools necessary for research in this field.

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application | Source / Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| HARIBOSS Dataset [12] | Dataset | A large collection of RNA-ligand complexes for training and benchmarking models, supports structure-based splits. | https://github.com/jaminzzz/RNABind |

| Train60 / Test18 [11] | Dataset | Standardized, non-redundant datasets of RNA-small molecule complexes for training and testing. | Source: RNAsite study [11] |

| Apo & Conformational Test Sets [11] | Dataset | Curated datasets for specifically evaluating model performance on apo-form and multi-conformation RNAs. | Constructed from PDB and SHAMAN [11] |

| RNAsmol Framework [13] | Software | Predicts RNA-small molecule interactions from sequence, using data perturbation to overcome data scarcity. | https://github.com/hongli-ma/RNAsmol |

| MVRBind Model [11] | Software | Predicts binding sites using multi-view feature fusion, effective for flexible RNA structures. | https://github.com/cschen-y/MVRBind |

Workflow and System Diagrams

RNA-Ligand Binding Site Prediction Workflow

MVRBind's Multi-View Learning Architecture

Current Limitations in Docking Algorithms and Scoring Functions

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My deep learning docking model performs well on validation sets but fails in real-world virtual screening. What could be wrong? This is a common issue related to generalization failure. Many DL docking models are trained and validated on curated datasets like PDBBind, which may not represent real-world screening scenarios [14]. The models may learn biases in the training data rather than underlying physics. To troubleshoot:

- Test your model on challenging benchmark sets like DockGen that contain novel binding pockets [14]

- Verify that your training data includes diverse protein families and ligand chemotypes [15]

- Implement cross-docking evaluations where ligands are docked to alternative receptor conformations [15]

Q2: Why does my docking protocol produce physically impossible molecular structures despite good RMSD scores? This occurs because scoring functions often prioritize pose accuracy over physical validity [14]. RMSD alone is insufficient - it doesn't capture bond lengths, angles, or steric clashes. Solution:

- Use tools like PoseBusters to check geometric consistency, stereochemistry, and protein-ligand clashes [14]

- For DL methods, add physical constraints to loss functions or use hybrid approaches that incorporate traditional force fields [14]

- Always validate hydrogen bonding patterns and torsion angles, especially with regression-based DL models [14]

Q3: How can I improve docking accuracy for flexible proteins that undergo conformational changes upon binding? Traditional rigid docking fails here. Consider these approaches:

- Use flexible docking methods like FlexPose or DynamicBind that model protein backbone and sidechain flexibility [15]

- For known conformational states, employ cross-docking protocols using multiple receptor structures [15]

- Implement MD simulations pre-docking to sample receptor conformations or post-docking for refinement [16]

- For apo-structures, choose methods specifically designed for apo-docking tasks [15]

Q4: What causes high variation in scoring function performance across different protein targets? Scoring functions show target-dependent performance due to:

- Imbalanced training data - some protein families are overrepresented [17]

- Simplified physics - most functions cannot capture all binding thermodynamics [16]

- Limited solvation models - inadequate treatment of water-mediated interactions [17] Mitigation strategies:

- Use consensus scoring across multiple functions [18]

- For specific target classes, choose specialized functions optimized for those proteins [17]

- Incorporate explicit water molecules in critical binding site regions [19]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Pose Prediction Accuracy

Symptoms: High RMSD values (>2Å) compared to crystal structures; inability to recover key molecular interactions.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Procedure | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify input preparation | Proper protonation states, charge assignment, and bond orders |

| 2 | Test multiple search algorithms | Systematic search for simple ligands; genetic algorithms for flexible ligands [16] |

| 3 | Compare scoring functions | At least 2-3 different function types (empirical, knowledge-based, force field) [18] |

| 4 | Check for binding site flexibility | Consider sidechain rotation or backbone movement if accuracy remains poor [15] |

Table 1: Pose accuracy troubleshooting protocol

Advanced Validation:

- Calculate interaction fingerprints to ensure recovery of critical hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts [14]

- For DL methods, check physical validity metrics beyond RMSD using PoseBusters [14]

- Perform consensus docking across multiple methods when high confidence is required [14]

Problem: Inadequate Virtual Screening Performance

Symptoms: Poor enrichment factors; inability to distinguish actives from decoys; high false positive rates.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Limitation | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Scoring function bias | Overfitting to certain interaction types | Use target-tailored functions or machine learning-based scoring [17] |

| Lack of generalization | Training data not representative of screening library | Apply domain adaptation techniques or transfer learning [14] |

| Insufficient chemical diversity | Limited representation in training | Augment with diverse chemotypes or use multi-task learning [15] |

Table 2: Virtual screening performance issues and solutions

Protocol for Screening Optimization:

- Pre-screen validation: Test scoring functions on known actives/inactives for your target

- Multi-stage screening: Combine fast initial docking with more sophisticated rescoring [14]

- Ensemble methods: Use multiple protein conformations to account for flexibility [15]

- Experimental integration: Prioritize compounds using additional criteria beyond docking scores

Problem: Handling Protein Flexibility and Induced Fit

Symptoms: Docking fails for apo structures; inaccurate poses for cross-docking; poor prediction of allosteric binding.

Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 1: Workflow for handling protein flexibility in docking

Key Considerations:

- For large-scale conformational changes, use enhanced sampling MD methods [19]

- For local sidechain flexibility, rotamer sampling may be sufficient [15]

- Cryptic pockets require specialized methods like Mixed-Solvent MD or Markov State Models [19]

Performance Benchmarking Data

Quantitative Comparison of Docking Methodologies

| Method Type | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-valid) | Combined Success Rate | Virtual Screening Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (Glide SP) | 75-85% | >94% | 70-80% | Moderate to high [14] |

| Generative Diffusion (SurfDock) | 76-92% | 40-64% | 33-61% | Variable [14] |

| Regression-based DL | 30-60% | 20-50% | 15-40% | Poor generalization [14] |

| Hybrid AI-Traditional | 70-80% | 85-95% | 65-75% | Consistently high [14] |

Table 3: Performance comparison across docking methodologies on benchmark datasets (Astex, PoseBusters, DockGen) [14]

Scoring Function Performance Metrics

| Scoring Function Type | Pose Prediction | Affinity Prediction | Speed | Physical Plausibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field-based | Moderate | Low | Slow | High [18] |

| Empirical | High | Moderate | Fast | Moderate [18] |

| Knowledge-based | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | Moderate [17] |

| Machine Learning | High | High | Fast (after training) | Variable [17] |

Table 4: Characteristics of different scoring function categories

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PDBBind Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding data | Method training and benchmarking [18] |

| PoseBusters Toolkit | Validation of physical and chemical plausibility | Pose quality assessment [14] |

| CASF Benchmark | Standardized assessment framework | Scoring function evaluation [18] |

| AutoDock Vina | Traditional docking with efficient search | Baseline comparisons and initial screening [14] |

| DiffDock | Diffusion-based docking | State-of-the-art pose prediction [15] |

| MD Simulation Suites | Sampling flexibility and dynamics | Pre- and post-docking refinement [16] |

| MixMD | Cryptic pocket detection | Identifying novel binding sites [19] |

Table 5: Essential resources for docking research and troubleshooting

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive Docking Validation

Diagram 2: Comprehensive docking validation workflow

Implementation Details:

- For pose prediction: Focus on RMSD, physical validity, and interaction recovery [14]

- For virtual screening: Evaluate using enrichment factors and early recognition metrics [14]

- For affinity prediction: Calculate correlation coefficients with experimental data [18]

- Always include multiple test sets to assess generalization [14]

Future Directions and Emerging Solutions

Addressing Current Limitations

Generalization Improvement:

- Develop meta-learning approaches that adapt to novel targets [15]

- Create more diverse benchmark datasets that represent real-world challenges [14]

- Implement multi-task learning across related prediction tasks [15]

Physical Plausibility:

- Incorporate molecular mechanics directly into DL architectures [14]

- Add geometric constraints and energy-based regularization to loss functions [14]

- Use hybrid approaches that combine DL pose generation with physics-based refinement [14]

Protein Flexibility:

- Advance equivariant models that naturally handle structural changes [15]

- Develop multi-state predictors for apo/holo conformation transitions [20]

- Integrate timescale-aware models that capture binding-induced dynamics [19]

The Impact of Binding Pose Accuracy on Downstream Drug Development Success

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is binding pose accuracy so critical for successful virtual screening? An accurate binding pose reveals the true atomic-level interactions between a drug candidate and its protein target. This is foundational for structure-based drug design, as it guides the optimization of a compound's potency and selectivity. If the predicted pose is incorrect, subsequent efforts to improve binding affinity based on that pose are likely to fail, leading to wasted resources and high rates of false positives in virtual screening campaigns [14] [21].

FAQ 2: My deep learning docking model performs well on benchmark datasets but fails in real-world lead optimization. What could be wrong? This is a common issue often traced to a generalization problem. Many benchmarks use time-based splits that can leak information, so models perform poorly on novel protein pockets or structurally unique ligands [14]. To address this:

- Expand Training Data: Augment your training set with large, diverse datasets of modeled complexes (e.g., BindingNet v2) to expose the model to a wider variety of structures [21].

- Incorporate Physics: Combine deep learning with physics-based refinement and rescoring methods (e.g., MM-GB/SA) to improve the physical plausibility of predictions [21].

- Re-evaluate Metrics: Move beyond a single metric like ligand RMSD. Systematically evaluate poses for chemical validity, lack of steric clashes, and recovery of key protein-ligand interactions using tools like PoseBusters [14].

FAQ 3: What are the most common causes of physically implausible binding poses, and how can I fix them? Physically implausible poses often exhibit incorrect bond lengths/angles, steric clashes with the protein, or improper stereochemistry.

- Cause: Many deep learning models, particularly regression-based architectures, have high steric tolerance and do not explicitly enforce physical constraints during pose generation [14].

- Solution: Implement a post-prediction refinement step using molecular mechanics force fields. Furthermore, prioritize methods that incorporate physical constraints or use hybrid approaches that combine AI with traditional conformational search algorithms [14].

FAQ 4: How does the choice of computational method impact the risk of downstream failure? The choice of docking method directly influences the quality of your initial hits and the likelihood of downstream success. The table below summarizes the trade-offs.

| Method Category | Typical Pose Accuracy | Typical Physical Validity | Key Downstream Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (Glide SP, Vina) | Moderate [14] | High [14] | Lower hit rates from more conservative scoring; may miss novel chemotypes [14]. |

| Deep Learning: Generative Diffusion | High [14] | Moderate [14] | Risk of optimizing compounds based on inaccurate interactions due to lower physical validity [14]. |

| Deep Learning: Regression-based | Low [14] | Low [14] | High risk of pursuing false positives with invalid chemistries [14]. |

| Hybrid (AI scoring + traditional search) | High [14] | High [14] | Lower overall risk; balanced approach for both pose identification and validity [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Improving Poor Pose Accuracy in Novel Targets

Symptoms: Your docking protocol fails to generate poses near the native crystal structure (RMSD > 2 Å) for targets with no close homologs in the training data.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Assess Data Similarity:

- Calculate the sequence similarity between your novel target and the proteins in your model's training set.

- Check for similar binding pocket architectures, as global sequence similarity can be misleading [14].

- Evaluate Sampling vs. Scoring:

- Determine if the problem is sampling (the correct pose was never generated) or scoring (the correct pose was generated but not ranked first).

- Inspect the full set of generated poses (e.g., the top 10 or 20) to see if a near-native pose exists but is low-ranked.

- Implement Solutions:

- If sampling is the issue: Consider template-based modeling approaches if a structural template with a similar binding mode exists, even if ligand similarity is low [21]. For deep learning methods, augment training data with diverse, modeled complexes [21].

- If scoring is the issue: Replace or augment the default scoring function. Use a consensus score or a more rigorous physics-based method like MM-GB/SA for final pose selection [21].

Guide 2: Addressing Failure in Structure-Based Virtual Screening

Symptoms: Your virtual screening fails to identify true active compounds, yielding a high false positive rate.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Validate the Pose Quality of Top Hits:

- Do not rely solely on a docking score. Manually inspect the top-ranked poses for key interactions like hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts. Check their physical plausibility with PoseBusters [14].

- Check for Artificial Enrichment:

- Ensure your validation benchmark does not contain proteins or ligands that are highly similar to those in your model's training set, which can lead to over-optimistic performance [14].

- Implement a Multi-Stage Workflow:

Guide 3: Resolving Physically Invalid Pose Predictions

Symptoms: Predicted binding poses contain steric clashes, incorrect bond lengths/angles, or distorted geometries.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Identify the Invalidity: Use a validation tool like PoseBusters to generate a report on the specific chemical and geometric inconsistencies [14].

- Select a More Robust Method:

- Apply Post-Prediction Refinement:

- For any generated pose, run a short energy minimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., in GROMACS or Schrodinger) to relax the structure and resolve clashes while keeping it near the original coordinates [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Docking Pose Accuracy and Generalization

Objective: To rigorously evaluate the performance of a docking method on known complexes, unseen complexes, and novel binding pockets.

Materials:

- Software: Docking software of choice; PoseBusters validation toolkit [14].

- Datasets:

Methodology:

- Pose Prediction: Run the docking method against all complexes in the three benchmark datasets.

- Pose Accuracy Calculation: For each complex, calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between the predicted ligand pose and the experimental crystal structure pose. A successful prediction is typically defined as RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å [14].

- Physical Validity Check: Process all top-ranked poses through PoseBusters to determine the PB-valid rate [14].

- Combined Success Rate: Calculate the percentage of cases that are both successful in RMSD and PB-valid [14].

- Analysis: Compare results across the three datasets. A significant drop in performance on the DockGen set indicates poor generalization to novel pockets [14].

Protocol 2: Enhancing Generalization with Data Augmentation and Refinement

Objective: To improve a deep learning model's performance on novel ligands by augmenting its training data and applying physics-based refinement.

Materials:

- Software: Deep learning model for docking (e.g., Uni-Mol); Molecular mechanics software (e.g., GROMACS, Schrodinger) [21].

- Datasets: PDBbind dataset (core set); Augmented dataset (e.g., BindingNet v2) [21].

Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Train the deep learning model (e.g., Uni-Mol) on the PDBbind dataset. Evaluate its success rate (RMSD < 2 Å) on a test set containing novel ligands (Tanimoto coefficient < 0.3) [21].

- Data Augmentation: Retrain the model on progressively larger subsets of the BindingNet v2 dataset, which contains hundreds of thousands of modeled protein-ligand complexes [21].

- Re-evaluate: After each training round with augmented data, re-evaluate the model's success rate on the same novel ligand test set. Expect to see a significant improvement (e.g., from 38.55% to over 60%) [21].

- Physics-Based Refinement: For the final poses generated by the augmented model, perform a physics-based refinement using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MM-GB/SA). This step can further increase the success rate and ensure physical validity, potentially achieving success rates over 70% while passing PoseBusters checks [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in Binding Pose Prediction |

|---|---|

| PoseBusters Toolkit | A validation tool to check predicted protein-ligand complexes for chemical and geometric correctness, identifying steric clashes and incorrect bond lengths [14]. |

| BindingNet v2 Dataset | A large-scale dataset of computationally modeled protein-ligand complexes used to augment training data and improve model generalization to novel ligands [21]. |

| MM-GB/SA | A physics-based scoring method used for post-docking pose refinement and rescoring to improve pose selection accuracy and physical plausibility [21]. |

| Astex Diverse Set | A curated benchmark dataset of high-quality protein-ligand complexes used for initial validation of docking pose accuracy [14]. |

| DockGen Dataset | A benchmark dataset specifically designed to test docking method performance on novel protein binding pockets, assessing generalization [14]. |

Advanced Computational Approaches: Integrating Docking, Machine Learning, and Multi-Method Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of combining genetic algorithms with machine learning for docking?

Integrating genetic algorithms (GAs) with machine learning (ML) creates a powerful synergy. The GA component, such as the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) in AutoDock, excels at sampling the vast conformational space of a ligand by mimicking evolutionary processes like mutation and selection [23]. However, no single algorithm or scoring function is universally best for all docking tasks [23] [24]. This is where ML comes in. ML models can be trained to rescore and rerank the poses generated by the GA, significantly improving the identification of true binding modes. For challenging targets like Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs), ML models like neural networks and random forests have achieved up to a seven-fold increase in enrichment factors at the top 1% of screened compounds compared to traditional scoring functions [25].

Q2: My docking results are inconsistent across different protein conformations. How can a hybrid pipeline address this?

This is a classic challenge related to protein flexibility [24]. A robust hybrid pipeline can address this by using an ensemble of protein structures. Instead of docking into a single static protein structure, you can use multiple structures representing different conformational states. ML models can then be trained on docking results from this entire ensemble. Furthermore, algorithm selection systems like ALORS can automatically choose the best-performing docking algorithm (e.g., a specific LGA variant) for each individual protein-ligand pair based on its molecular features, leading to more consistent and robust performance across diverse targets [23].

Q3: How do I handle metal-binding sites in my target protein during docking?

Metal ions in active sites pose a significant challenge for standard docking programs, which often struggle to correctly model the coordination geometry and interactions of Metal-Binding Pharmacophores (MBPs) [6]. A specialized workflow has been developed for this:

- Fragment Docking with DFT: The MBP fragment of your inhibitor is first optimized using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. This optimized fragment is then docked into the metalloenzyme's active site using a GA in GOLD, with the metal ion's coordination geometry pre-defined [6].

- Fragment Elaboration: The docked pose of the MBP is kept fixed, and the rest of the inhibitor molecule is built onto it using a molecule builder like MOE, followed by energy minimization [6]. This method has demonstrated high accuracy, with predicted binding poses deviating from crystallographically determined structures by an average RMSD of only 0.87 Å [6].

Q4: What types of descriptors are most informative for ML models in docking pipelines?

While traditional chemical fingerprints are useful, 3D structural descriptors derived directly from the docking poses are highly valuable. A key category is Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) descriptors [25]. These include:

- Changes in the protein's SASA upon ligand binding.

- Changes in the ligand's SASA.

- The buried surface area of the complex. These descriptors capture the topological and solvation effects of the binding event and have been shown to outperform several classical scoring functions in virtual screening tasks [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Early Enrichment in Virtual Screening

You are running a virtual screen, but the truly active compounds are not ranked near the top of your list.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inadequate scoring function | Implement an ML-based rescoring strategy. Train a classifier (e.g., Neural Network, Random Forest) on known active and inactive compounds using pose-derived descriptors like SASA. This can dramatically improve early enrichment [25]. |

| Suboptimal algorithm parameters | Use an algorithm selection approach. Instead of relying on a single set of GA parameters, create a suite of algorithm variants (e.g., 28 different LGA configurations) and use a recommender system like ALORS to select the best one for your specific target [23]. |

Problem: Inaccurate Poses for Metalloenzyme Inhibitors

The predicted binding poses for your metalloenzyme inhibitors do not match the expected metal-coordination geometry.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Standard scoring functions cannot handle metal coordination | Adopt a specialized metalloenzyme docking protocol. Use a combination of DFT for MBP optimization and GA-based docking (e.g., with GOLD) specifically for the metal-binding fragment, followed by fragment growth [6]. |

| Incorrect treatment of metal ions | Ensure the metal ion coordination geometry (e.g., tetrahedral, octahedral) is correctly predefined in the docking software settings. Treating the metal as a simple charged atom will lead to failures [6]. |

Problem: High Computational Cost of The Pipeline

The process of generating poses with a GA and then refining/scoring with ML is becoming computationally prohibitive.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Docking large, flexible ligands | Implement a hierarchical workflow. Use a fast shape-matching or systematic search method for initial pose generation for the entire library, then apply the more computationally intensive GA and ML rescoring only to a pre-filtered subset of promising candidates [24]. |

| Inefficient resource allocation | Choose the right docking "quality" setting. For initial rapid screening, use a faster, "Classic" docking option. Reserve more computationally expensive "Refined" or "STMD" options, which include pose optimization and more advanced scoring, for the final shortlist of hits [26]. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Performance of ML Models for Rescoring Docking Poses on PPI Targets

Data from a study evaluating different ML classifiers trained on SASA descriptors for virtual screening enrichment [25].

| Machine Learning Model | Key Performance Metric (Enrichment Factor at 1%) | Notes / Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Network | Up to 7-fold increase | Consistently top performer for early enrichment; handles complex non-linear relationships. |

| Random Forest | Up to 7-fold increase | Robust, less prone to overfitting; provides feature importance. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Performance robust but slightly lower than NN/RF | Effective in high-dimensional descriptor spaces. |

| Logistic Regression | Lower than NN/RF | Provides a simple, interpretable baseline model. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Essential software tools and their functions in a hybrid docking-ML pipeline.

| Tool Name | Function in Pipeline | Key Feature / Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock4.2 / GOLD | Genetic Algorithm-based Docking | Generates initial ligand poses. LGA in AutoDock and the GA in GOLD are widely used for conformational sampling [23] [6]. |

| AlphaFold | Protein Structure Prediction | Provides highly accurate 3D protein models when experimental structures are unavailable, expanding the range of druggable targets [27]. |

| Gaussian | Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations | Optimizes the 3D geometry of metal-binding pharmacophores (MBPs) prior to docking [6]. |

| MOE | Molecular Modeling & Fragment Elaboration | Used to build the full inhibitor from a docked MBP fragment and for energy minimization [6]. |

| ALORS | Algorithm Selection System | Recommends the best docking algorithm variant for a given protein-ligand pair based on its molecular features [23]. |

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for a Hybrid Docking-ML Pipeline

This protocol outlines the general steps for integrating genetic algorithm docking with machine learning to improve virtual screening outcomes [25] [23].

Data Curation & Preparation:

- Collect a dataset of known active and inactive molecules for your target from databases like ChEMBL and PubChem.

- Prepare the protein structure(s), which could include an ensemble of conformations to account for flexibility.

Pose Generation with Genetic Algorithm:

- Dock all compounds into the target's binding site using a GA-based docking program (e.g., AutoDock4.2 LGA or GOLD).

- Generate and save multiple poses per ligand.

Descriptor Calculation:

- Post-process the top-ranked docking poses to calculate relevant descriptors.

- Key Descriptors: Derive Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) descriptors for the protein, ligand, and complex in both bound and unbound states [25].

Machine Learning Model Training & Validation:

- Split the data into training and test sets.

- Train multiple ML classifiers (e.g., Neural Network, Random Forest, SVM) using the calculated descriptors to distinguish actives from inactives.

- Validate model performance on the test set using metrics like AUC, enrichment factors (EF1%, EF5%), and early recognition metrics (BEDROC).

Virtual Screening & Hit Selection:

- Apply the trained and validated ML model to score and rank new, unseen compounds from a virtual library.

- Select the top-ranked compounds for further experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Specialized Protocol for Metalloenzyme Targets

This protocol details a method for accurately predicting the binding pose of inhibitors that feature a metal-binding pharmacophore (MBP) [6].

MBP Fragment Preparation:

- Isolate the MBP (e.g., a hydroxamic acid, carboxylic acid) from the full inhibitor.

- Generate and energetically optimize the 3D structure of the MBP fragment using DFT calculations with software like Gaussian.

Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the metalloenzyme structure from the PDB.

- Remove water molecules and other small molecules. Add hydrogen atoms and protonate side chains at physiological pH using a molecular modeling suite like MOE.

Fragment Docking with Predefined Geometry:

- Dock the DFT-optimized MBP fragment into the active site using a genetic algorithm in GOLD.

- Critical Step: Set the metal ions in the active site with a predefined coordination geometry (e.g., tetrahedral for Zn²⁺ in hCAII).

- Rescore the generated poses using the GoldScore function.

Inhibitor Elaboration and Minimization:

- Import the best-scoring MBP pose into MOE.

- Manually elaborate the MBP fragment to rebuild the complete inhibitor structure.

- Perform energy minimization of the full inhibitor, keeping the pose of the MBP fragment fixed to maintain the correct metal coordination.

General Hybrid Docking-ML Workflow

Metalloenzyme Docking Workflow

A Technical Support Center for Computational Researchers

This guide provides targeted support for researchers integrating Density Functional Theory (DFT) with molecular docking to study metalloenzymes. These protocols address the specific challenge of accurately modeling metal-containing active sites, a known hurdle in computational drug design [6].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why do standard docking programs often fail to predict correct binding poses for metalloenzyme inhibitors?

Answer: Standard docking programs face two primary challenges with metalloenzymes:

- Inadequate Scoring Functions: Conventional scoring functions are not well-parameterized for the unique coordination chemistry of metal ions. They often fail to properly describe the energy of coordination bonds between the metal and the inhibitor's Metal-Binding Pharmacophore (MBP) [6].

- Incorrect Metal Coordination Geometry: The programs may not enforce the correct geometry (e.g., tetrahedral, octahedral) around the metal ion in the active site, leading to physically unrealistic binding poses [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: If your docking results show the inhibitor failing to coordinate the metal or adopting an unnatural geometry: Action: Employ a specialized protocol that pre-defines the metal's coordination geometry before docking. Action: Use a combination of docking programs, leveraging their individual strengths. For instance, use a genetic algorithm-based docker for the MBP placement and another program for lead elaboration [6].

FAQ 2: How can I use DFT to improve the initial structure of my metal-binding ligand before docking?

Answer: DFT calculations are crucial for generating an energetically optimized and realistic three-dimensional structure of your MBP or metal complex prior to docking [6] [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: If your ligand structure is not chemically realistic or lacks stability in simulations: Action: Perform a full geometry optimization of the isolated ligand or metal complex using DFT. Common functionals like B3LYP are widely used [29] [30]. Action: Use basis sets such as 6-311G(d,p) for organic ligands and LANL2DZ for transition metals to account for relativistic effects [31] [29]. Action: Calculate molecular descriptors like Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) energies and Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps to predict reactivity and potential binding sites [28] [29].

FAQ 3: What is a robust workflow for integrating DFT and docking for metalloenzymes?

Answer: A successful strategy involves a stepwise, multi-software approach that separates the problem into manageable tasks. The following workflow has been validated against crystallographic data with good agreement (average RMSD of 0.87 Å) [6].

Diagram 1: Integrated DFT-Docking Workflow for Metalloenzymes.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Ligand Preparation & DFT Optimization: Build the 3D structure of your MBP fragment (e.g., a hydroxamic acid or sulfonamide). Perform a DFT calculation (e.g., using Gaussian) to optimize its geometry at an appropriate level of theory (e.g., B3LYP/6-311G(d,p)) [6] [31].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the metalloenzyme structure from the PDB. Remove extraneous water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms and protonate side chains at physiological pH using a program like MOE [6].

- Fragment Docking: Dock the DFT-optimized MBP fragment into the rigid protein active site using a genetic algorithm-based docking program (e.g., GOLD). Critically, pre-define the coordination geometry of the metal ion(s) (e.g., tetrahedral for Zn²⁺ in hCAII) [6].

- Fragment Growth & Minimization: Using the best pose from fragment docking as a fixed anchor, manually elaborate the MBP into the full inhibitor structure. Finally, perform an energetic minimization of the entire inhibitor while keeping the MBP pose fixed [6].

- Validation: Always validate your computational protocol by comparing predicted binding poses against known crystal structures (if available) and calculating the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) [6].

FAQ 4: How do I validate the accuracy of my integrated DFT-Docking protocol?

Answer: The most direct method is to compare your computational results with experimental data.

Troubleshooting Guide: If you are unsure about the reliability of your predictions: Action: Use the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) metric. An average RMSD of less than 1.0-2.0 Å between the computationally predicted pose and the experimental crystal structure is generally considered a successful prediction [6]. The table below shows sample validation data from a published study.

Table 1: Sample Validation Data Comparing Computed vs. Crystallographic Poses [6]

| Enzyme Target | PDB Entry | Calculated RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| Human Carbonic Anhydrase II (hCAII) | 2WEJ | 0.49 |

| Histone Lysine Demethylase (KDM) | 2VD7 | 0.22 |

| Influenza Polymerase (PAN) | 4MK1 | 1.67 |

| Human Carbonic Anhydrase II (hCAII) | 6RMP | 3.75 |

Action: Be aware of outliers. As seen in Table 1, some complexes (e.g., 6RMP) may show higher RMSD due to unexpected binding modes. Investigate these cases further, as they may reveal specific protein-flexibility or solvent effects not captured by the standard protocol [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Key Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian [6] | Quantum Chemistry Software | Performing DFT calculations for geometry optimization and electronic structure analysis of ligands and metal complexes. |

| GOLD (Genetic Optimization for Ligand Docking) [6] | Docking Software | Docking MBP fragments with a genetic algorithm, allowing control over metal coordination geometry. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [6] | Molecular Modeling Suite | Protein preparation, fragment growth, and energy minimization of the final protein-inhibitor complex. |

| Glide [32] | Docking Software | High-throughput and high-accuracy docking; useful for evaluating binding affinity of designed anchors. |

| AutoDock/ AutoDock Vina [6] [29] | Docking Software | Commonly used docking programs; performance for metalloenzymes can be variable and may require careful parameterization [6]. |

| Rosetta Suite [32] [33] | Protein Design Software | For advanced applications like de novo design of metal-binding sites and optimizing protein-scaffold interactions. |

What to Do Next

- Refine with Advanced Calculations: For critical complexes, follow up docking with more accurate but computationally expensive Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) or molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to refine poses and calculate binding affinities [6] [32].

- Explore Multivalent Inhibition: As shown in recent studies, designing bivalent inhibitors that feature two metal-binding pharmacophores can significantly enhance efficacy and selectivity against specific metalloenzyme isoforms [29].

- Apply to Artificial Metalloenzymes (ArMs): These protocols are also highly applicable to the design of ArMs, where docking can help identify optimal supramolecular anchors for metal catalysts within protein scaffolds [32] [33].

Graph Neural Networks for Protein-Ligand Interaction Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is the core advantage of using GNNs over traditional methods for binding affinity prediction?

GNNs excel at directly modeling the inherent graph structure of protein-ligand complexes, where atoms are nodes and bonds or interactions are edges. This allows them to capture complex topological relationships and spatial patterns that are difficult for traditional force-field or empirical scoring functions to represent. GNNs learn these representations directly from data, leading to superior performance in predicting binding affinities and poses compared to classical methods [34] [35] [36].

Q2: My model performs well on the CASF benchmark but poorly in real-world virtual screening. What could be the cause?

This is a classic sign of data bias and train-test leakage. The standard CASF benchmarks and the PDBbind training set share structurally similar complexes, allowing models to "memorize" patterns rather than learn generalizable principles. To fix this, use a rigorously curated dataset like PDBbind CleanSplit, which removes complexes with high protein, ligand, and binding conformation similarity from the training set to ensure a true evaluation of generalization [37].

Q3: What is the difference between "intra-molecular" and "inter-molecular" message passing in a GNN, and why is it important?

- Intra-molecular message passing occurs within the same molecule (e.g., between atoms in the protein or within the ligand). It helps the model understand the individual chemical environments of the protein's binding pocket and the ligand.

- Inter-molecular message passing occurs between atoms of different molecules (e.g., between a protein atom and a ligand atom). It is crucial for explicitly modeling the specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) that determine binding. Models that separate these processes, like Interformer, often achieve better performance by more accurately capturing the physics of the interaction interface [34] [38].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Q4: The binding poses generated by my model are physically implausible, with steric clashes or incorrect bond angles. How can I improve pose quality?

This issue often arises when the model focuses solely on minimizing RMSD without learning physical constraints. Implement the following:

- Incorporate Specific Interaction Terms: Use an interaction-aware mixture density network (MDN) to explicitly model the distance distributions for key non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts. This guides the model to generate poses that satisfy these critical constraints [38].

- Contrastive Learning with Poor Poses: Train your model with a negative sampling strategy. Include deliberately generated poor poses (e.g., with clashes, incorrect orientations) and use a loss function that teaches the model to assign a low score to these incorrect conformations and a high score to native-like ones [38] [39].

Q5: My GNN model seems to be "memorizing" ligands from the training set instead of learning general protein-ligand interactions. How can I verify and address this?

- Verification: Perform an ablation study where you remove the protein nodes from your input graph and only use ligand information. If the prediction performance remains high, it indicates heavy reliance on ligand memorization [37].

- Solution: Curate your training data to reduce redundancy. Apply a structure-based filtering algorithm that clusters complexes with similar ligands (Tanimoto score > 0.9) and similar protein structures, retaining only a diverse subset for training. This forces the model to learn the interaction rather than recall specific molecules [37].

Q6: How can I make my affinity prediction model more robust for virtual screening when only predicted or docked poses are available?

Traditional models trained only on high-quality crystal structures often fail on docked poses. To improve robustness:

- Train on Decoy-rich Datasets: Augment your training data with a large number of conformational decoys, cross-docked decoys, and random decoys. This teaches the model to distinguish near-native poses from incorrect ones, making it less sensitive to pose inaccuracies [39].

- Hybrid Modeling: Combine your GNN's predictions with a physics-based scoring function. The GNN captures complex patterns, while the physics-based term provides a foundational, physically realistic baseline, leading to better generalization on novel complexes [39].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Building a Robust Training Set to Avoid Data Bias

Objective: To create a training dataset free of data leakage and redundancy for reliably evaluating model generalizability.

Materials: PDBbind v2020 general set, CASF-2016 benchmark set, clustering software.

Steps:

- Calculate Complex Similarity: For every complex in the training set (PDBbind) and test set (CASF-2016), compute a multi-modal similarity score.

- Identify and Remove Test Analogs: Apply filtering thresholds (e.g., TM-score > 0.7, Tanimoto > 0.9, RMSD < 2.0Å) to identify any training complexes that are highly similar to any test complex. Remove these from the training set [37].

- Reduce Internal Redundancy: Within the remaining training set, identify clusters of highly similar complexes. Iteratively remove complexes from these clusters until all significant redundancies are eliminated, resulting in a diverse training dataset [37].

- Output: The final product is a curated dataset, such as PDBbind CleanSplit, suitable for training models whose performance on the CASF benchmark will reflect true generalization [37].

Protocol: Implementing an Edge-Enhanced GNN (EIGN) for Affinity Prediction

Objective: To implement a GNN that enhances edge features to better capture protein-ligand interactions.

Materials: Protein-ligand complex structures (e.g., from PDBbind), RDKit software, deep learning framework (e.g., PyTorch).

Steps:

- Graph Construction: Represent the protein-ligand complex as a graph.

- Normalized Adaptive Encoder (NAE): Pass the initial node and edge features through an encoder to generate normalized input representations [34].

- Molecular Message Propagation:

- Perform separate intra-molecular message passing within the protein and within the ligand to update node features.

- Perform inter-molecular message passing between protein and ligand atoms to model their interactions.

- Crucially, implement an edge update mechanism. After each message-passing step, update the edge features by integrating information from the connected nodes. This creates edge-aware representations that are critical for modeling interactions [34].

- Output Module: Pool the final updated node features into a graph-level representation. Pass this through fully connected layers to predict the binding affinity (e.g., pKd/pKi) [34].

Protocol: Implementing Interaction-Aware Docking with Interformer

Objective: To generate accurate and physically plausible docking poses by explicitly modeling non-covalent interactions.

Materials: 3D structures of proteins and ligands, Interformer model architecture.

Steps:

- Input and Featurization: Take an initial ligand conformation and the protein's binding site as input. Use pharmacophore atom types as node features and Euclidean distance as edge features [38].

- Intra- and Inter-Blocks:

- Process node and edge features through Intra-Blocks to update features based on intra-molecular connections.

- Process the updated features through Inter-Blocks to capture inter-molecular interactions between protein and ligand atom pairs [38].

- Interaction-Aware Mixture Density Network (MDN):

- The output from the Inter-Blocks is fed into an MDN.

- The MDN predicts parameters for four Gaussian functions for each protein-ligand atom pair. These are constrained to model: 1) all pair interactions, 2) all pair interactions, 3) hydrophobic interactions, and 4) hydrogen bond interactions specifically [38].

- Combine these Gaussians into a Mixture Density Function (MDF) that acts as a knowledge-based energy function.

- Pose Sampling and Scoring: Use a Monte Carlo sampler to generate top-k ligand conformations by minimizing the energy function defined by the MDF. The final poses are then ranked using a pose score model [38].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GNN Models on CASF-2016 Benchmark

| Model | RMSE (kcal/mol) | Pearson Correlation (R) | Key Architectural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| EIGN [34] | 1.126 | 0.861 | Edge-update mechanism & separate inter/intra-molecular messaging |