AlphaFold 3 vs. Molecular Docking: A Critical Evaluation for Pose Prediction in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of AlphaFold 3's capabilities for protein-ligand pose prediction against established molecular docking methods.

AlphaFold 3 vs. Molecular Docking: A Critical Evaluation for Pose Prediction in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of AlphaFold 3's capabilities for protein-ligand pose prediction against established molecular docking methods. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of co-folding and docking, analyzes performance benchmarks across diverse biological targets, and addresses critical limitations such as physical realism and generalization. The review offers practical guidance for troubleshooting predictions, leveraging confidence metrics, and integrating these tools into robust research workflows. By synthesizing recent validation studies and comparative analyses, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively and critically apply these powerful technologies in structural biology and drug design.

The New Paradigm: Understanding Co-Folding and Traditional Docking

The accurate prediction of how small molecules interact with protein targets is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. For decades, the dominant computational approach has been search-and-score molecular docking, a method that relies on physics-inspired scoring functions to evaluate millions of potential ligand poses. However, the recent advent of deep learning co-folding models, exemplified by AlphaFold 3 (AF3), promises a paradigm shift. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methodologies for pose prediction research, framing them within a broader thesis on their respective capabilities, limitations, and optimal applications. By synthesizing findings from recent independent benchmarks and original research, we aim to equip researchers with the data needed to select the appropriate tool for their specific scientific question.

Core Methodological Principles

Search-and-Score Molecular Docking

Traditional molecular docking operates on a search-and-score framework [1]. It involves computationally sampling a vast space of possible ligand conformations and orientations (the "search") within a defined protein binding pocket. Each candidate pose is then evaluated using a scoring function—an algorithmic approximation of the binding affinity—to identify the most probable binding mode [1] [2]. These scoring functions can be physics-based (considering van der Waals forces, electrostatics, etc.), empirical (parameterized against experimental binding data), or knowledge-based [2]. A significant limitation of most traditional methods is their treatment of the protein receptor as a rigid body, which fails to capture the induced fit conformational changes that often occur upon ligand binding [1].

Co-Folding with AlphaFold 3

AlphaFold 3 represents a fundamentally different approach. It is a deep learning model that uses a diffusion-based architecture to predict the joint 3D structure of a biomolecular complex from scratch, using only the protein sequence and the ligand's SMILES string as input [3]. Instead of searching and scoring, AF3 "co-folds" the molecules into their bound configuration. Its key innovation is the replacement of AlphaFold 2's structure module with a diffusion module that predicts raw atom coordinates directly, eliminating the need for complex, molecule-specific representations and losses [3]. This allows AF3 to model complexes of proteins, nucleic acids, ions, and small molecules within a single, unified framework.

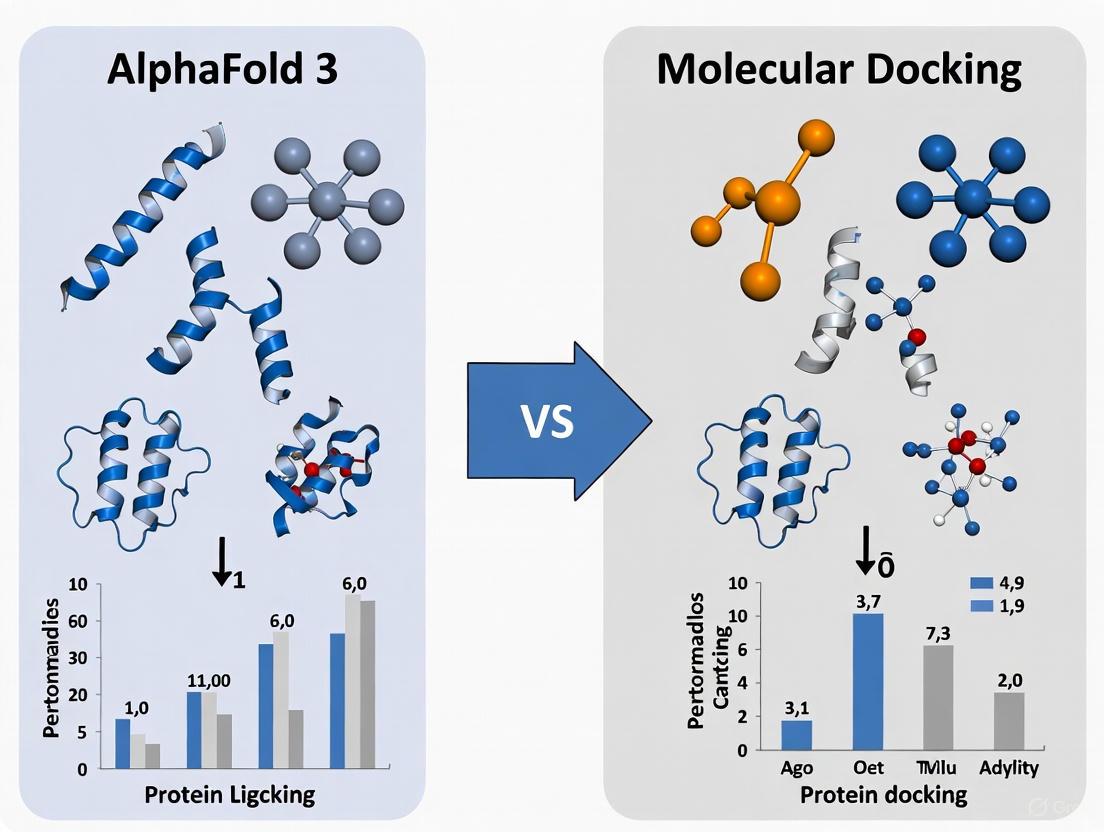

Visual Comparison of Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences in the operational workflows between a traditional docking pipeline and the AlphaFold 3 co-folding process.

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Independent studies have rigorously evaluated the performance of AF3 against established docking tools. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from these benchmarks.

Table 1: Overall Protein-Ligand Docking Accuracy on the PoseBusters Benchmark [3] [4] [5]

| Method | Input Requirements | Success Rate (PB-Valid & <2Å RMSD) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 (Blind) | Protein Sequence, Ligand SMILES | ~76% | No structural input; true blind docking |

| AlphaFold 3 (Pocket-Specified) | Protein Sequence, Ligand SMILES, Pocket Residues | ~93% | Informed of binding site location [3] |

| Strong Baseline (Vina + Gnina) | Protein Structure, Ligand SMILES | ~80% | Uses experimental receptor structure [4] |

| Original Vina Baseline | Protein Structure, Ligand SMILES | ~61% | As reported in AF3 paper [3] [4] |

| DiffDock | Protein Structure, Ligand SMILES | ~38% | Previous leading deep learning docking method [6] |

Table 2: Performance on Specific Docking Challenges and Complex Types [6] [7] [5]

| Task / Complex Type | Representative Method | Performance Metric | Result / Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Antigen Docking | AlphaFold 3 (single seed) | High-Accuracy Success Rate (DockQ ≥0.8) | 10.2% (Antibody), 13.3% (Nanobody) [7] |

| AlphaFold 3 (1,000 seeds) | Overall Docking Success Rate | ~60% [7] | |

| Binding Site Mutagenesis | Co-folding models (AF3, RFAA, etc.) | Robustness to non-physical binding site mutations | Poor; models place ligands in mutated sites despite loss of interactions [6] |

| Covalent Ligand Prediction | AlphaFold 3 | AUC for classifying binders vs. decoys | 98.3% [5] |

| Unseen vs. Common Ligands | AlphaFold 3 (Blind) | Success Rate on common natural ligands | Excels (e.g., nucleotides) [4] |

| Strong Baseline | Success Rate on drug-like molecules (excl. common naturals) | Outperforms blind AF3 by 8.5% [4] |

Key Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking

To critically assess the results, it is essential to understand the methodologies behind these benchmarks:

- PoseBusters Benchmark [3] [4]: This test set comprises 428 protein-ligand crystal structures released after AF3's training data cutoff. The primary success metric is the percentage of predictions where the ligand's pocket-aligned Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is less than 2.0 Å and the pose is free of stereochemical violations and severe clashes (deemed "PB-valid").

- Adversarial Physical Challenge [6]: This protocol tests the model's understanding of physical principles rather than its pattern recognition. Researchers selected a known complex (e.g., ATP-bound CDK2) and mutated all binding site residues to glycine (removing side-chain interactions) or phenylalanine (sterically occluding the pocket). A physically intuitive model should predict the ligand is displaced, whereas an overfitted one may still place it in the original site.

- Antibody-Antigen Docking Benchmark [7]: This involves a curated, redundancy-filtered set of antibody and nanobody complexes. Performance is evaluated using the DockQ score, which integrates interface and ligand RMSD metrics into a single value, with DockQ ≥ 0.8 indicating "high-accuracy" predictions as per CAPRI standards.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Pose Prediction Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Server | Web Server | Provides free access to AlphaFold 3 for non-commercial research. | Public Web Interface |

| Gnina | Software | A deep learning-based scoring function for rescoring and selecting docking poses from tools like Vina [4]. | Open-Source |

| ABCFold | Software Toolbox | Simplifies the execution and comparison of AF3, Boltz-1, and Chai-1 by standardizing inputs and outputs [5]. | Open-Source |

| PoseBusters | Python Package | Validates and checks the physical realism and quality of predicted molecular poses against experimental structures [4]. | Open-Source |

| Boltz-1 / Boltz-2 | Software | AF3-like models that introduce features like user-defined pocket conditioning and binding affinity prediction [5]. | Varies |

| Chai-1 | Software | An AF3-like multi-modal foundation model that can be prompted with experimental constraints [5]. | Python Package |

| FeatureDock | Software | A transformer-based docking method that predicts ligand probability density envelopes, useful for pose prediction and scoring [2]. | Open-Source |

Comparative Analysis: Strengths and Limitations

Advantages of AlphaFold 3 Co-Folding

- Elimination of the Protein Structure Requirement: AF3's most significant advantage is its ability to perform true blind docking using only a protein sequence, making it invaluable for targets with no experimentally solved structures [3] [4].

- High Accuracy in Favorable Conditions: When the binding site is known and provided as input, or for ligands highly represented in its training data (e.g., common natural ligands), AF3's accuracy is exceptional, often surpassing traditional methods [3] [4] [5].

- Unified Framework: AF3 can model a vast array of biomolecular interactions—proteins, nucleic acids, ions, and small molecules—within a single model, offering remarkable versatility [3] [8].

Limitations and Concerns of AlphaFold 3

- Questionable Physical Understanding: Adversarial challenges reveal that AF3 and similar co-folding models can fail to learn underlying physics. They sometimes prioritize memorizing common binding motifs over modeling the specific chemical interactions of a given system, leading to physically implausible predictions when binding sites are mutated [6].

- Performance on Drug-like Molecules: While AF3 excels on common natural ligands, its performance advantage narrows or disappears on more "drug-like" molecules, particularly those with halogens or other features less common in the PDB. In one assessment, a strong traditional baseline outperformed blind AF3 on this subset of molecules [4].

- Sampling and Resource Intensity: Achieving top performance, especially for challenging targets like antibody-antigen complexes, can require generating hundreds or thousands of seeds (predictions), which is computationally expensive and, on the public server, subject to job limits [7] [5].

- Bias Towards Training Data: AF3 has been shown to exhibit biases, such as a tendency to predict active-state conformations of GPCRs regardless of the ligand's pharmacological type (agonist/antagonist) [5].

Persistent Strengths of Traditional Docking

- Strong Baselines are Competitive: When a high-quality experimental protein structure is available, robust traditional pipelines (e.g., using conformational ensembles and neural network rescoring with Gnina) can achieve accuracy comparable to or even exceeding blind AF3, and closely approaching pocket-specified AF3 performance [4].

- Explicit Handling of Physics: Traditional methods, while approximate, are built upon physical principles and force fields. This provides a more transparent, interpretable foundation for pose evaluation, even if the scoring functions are imperfect [1] [2].

- Computational Efficiency for Virtual Screening: Well-optimized docking programs are generally faster and more resource-efficient for screening ultra-large libraries of compounds than running multiple AF3 seeds per ligand [1] [4].

Integrated Workflow and Future Directions

The evidence suggests that AF3 and traditional docking are not simply replacements for one another but can be complementary tools. A synergistic workflow is emerging:

- Blind Site Identification with AF3: For targets with unknown or uncertain binding sites, use AF3 for blind prediction to identify potential binding pockets.

- Pose Generation and Refinement: Use the AF3-predicted structure or an available experimental structure with traditional docking (enhanced with conformational sampling and ML rescoring) to generate and rank poses for a library of ligands.

- Cross-Validation and Analysis: Employ tools like PoseBusters to validate the physical realism of the final predictions from both methods.

Future developments will likely focus on improving the physical robustness of deep learning models [6], integrating protein flexibility more effectively [1], and creating more seamless hybrid workflows that leverage the unique strengths of both co-folding and search-and-score paradigms.

The field of computational structural biology has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the introduction of DeepMind's AlphaFold models. While AlphaFold 2 (AF2) demonstrated unprecedented accuracy in protein structure prediction through its innovative Evoformer architecture, AlphaFold 3 (AF3) represents a fundamental paradigm shift by replacing the structure module with a diffusion-based approach and extending capabilities beyond proteins to a wide range of biomolecules [9] [3]. This architectural evolution enables researchers to predict the joint structure of complexes comprising proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues within a single unified deep-learning framework [3]. The implications for drug discovery are profound, as AF3 demonstrates at least 50% better accuracy than existing methods for protein-molecule interactions, with accuracy for specific cases like protein-ligand binding reportedly doubling [10]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these architectures, their performance benchmarks, and practical implications for pose prediction research.

Architectural Comparison: Evoformer vs. Diffusion

AlphaFold 2's Evoformer Architecture

AlphaFold 2's architecture centers on the Evoformer module, a specialized transformer network that jointly processes both the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) representation and the pair representation [9] [11]. The system operates through several key components:

- Input Embeddings: AF2 utilized 23 tokens representing the 20 standard amino acids, plus tokens for unknown amino acids, gaps, and masked MSA positions [9]

- Evoformer Stack: The core innovation that operates over both MSA and residue pairs through attention mechanisms and triangular multiplicative updates [12]

- Structure Module: This component generated atomic coordinates using a frame-based representation centered on Cα atoms, with side chains parameterized by χ-angles [13]. It required carefully tuned stereochemical violation penalties during training to enforce chemical plausibility [3]

The system was trained with specialized losses to maintain physical realism and achieved remarkable accuracy by leveraging evolutionary information from MSAs [11].

AlphaFold 3's Diffusion Architecture

AlphaFold 3 introduces substantial modifications to accommodate general biomolecular modeling:

- Expanded Input Tokens: Incorporates tokens for DNA, RNA, and general molecules (represented by single heavy atoms) [9]

- Simplified Trunk Architecture: Replaces the Evoformer with a Pairformer that processes only single and pair representations, removing the MSA representation from core processing [3] [13]

- Diffusion Module: The most significant change—replaces the structure module with a diffusion approach that operates directly on raw atom coordinates without rotational frames or equivariant processing [3]

The diffusion approach employs a relatively standard diffusion model trained to receive "noised" atomic coordinates and predict the true coordinates [3]. This method requires the network to learn protein structure at multiple length scales, with denoising at small noise levels emphasizing local stereochemistry and high noise levels emphasizing large-scale structure [3]. A notable advantage is the elimination of both torsion-based parameterizations and violation losses while handling the full complexity of general ligands [3].

Table 1: Core Architectural Components Comparison

| Component | AlphaFold 2 | AlphaFold 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Evoformer (processes MSA + pair representations) | Pairformer (processes only single + pair representations) |

| Structure Generation | Structure module with frame-based representation | Diffusion model operating on raw atom coordinates |

| Molecular Representation | Protein-specific (Cα frames with χ-angles) | Universal atomic-level representation |

| Input Scope | Proteins only | Proteins, nucleic acids, ligands, ions, modifications |

| Spatial Inductive Bias | Equivariant transformations | Minimal spatial bias with position embedding |

Performance Benchmarks Across Biomolecular Complexes

Protein-Ligand Interactions

AF3 demonstrates substantial improvements in protein-ligand docking accuracy compared to both traditional docking tools and specialized machine learning approaches:

Table 2: Protein-Ligand Docking Performance on PoseBusters Benchmark

| Method | Category | Accuracy (Ligand RMSD < 2Å) |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 | Blind prediction | Significantly outperforms all methods |

| Vina | Traditional docking (uses structural inputs) | Substantially lower than AF3 |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Blind prediction | Much lower than AF3 |

| AF3 (Early Training Cutoff) | Blind prediction | ~40-80% depending on modification type [9] |

On the PoseBusters benchmark (428 protein-ligand structures from PDB released in 2021 or later), AF3 "greatly outperforms classical docking tools such as state-of-the-art Vina" even without using structural inputs that traditional docking methods typically require [3]. The accuracy varies by modification type, with approximately 80% accuracy for bonded ligands and 40% for RNA-modified residues, though statistical error is relatively high due to limited dataset sizes [9].

Protein-Protein and Antibody-Antigen Complexes

AF3 shows notable improvements in protein-protein interactions, with particularly significant gains in antibody-antigen modeling:

Table 3: Antibody-Antigen Docking Performance

| Method | High-Accuracy Success Rate (DockQ ≥0.8) | Overall Success Rate (DockQ ≥0.23) |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 (single seed) | 10.2% (antibodies), 13.3% (nanobodies) | 34.7% (antibodies), 31.6% (nanobodies) |

| AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 | 2.4% | 23.4% |

| AlphaFold 3 (1,000 seeds) | ~60% (as reported by DeepMind) | Not specified |

| Boltz-1 | 4.1% (antibodies), 5.0% (nanobodies) | 20.4% (antibodies), 23.3% (nanobodies) |

Despite these improvements, a recent evaluation noted that AF3 has a 65% failure rate for antibody and nanobody docking with single seed sampling, "demonstrating a need to further improve antibody modeling tools" [7]. The same study found that while AF3 achieves better direct prediction-experiment comparisons, after molecular dynamics simulation relaxation, "the quality of structural ensembles sampled drops severely," potentially due to "instability of the predicted intermolecular packing" [14].

Protein-Nucleic Acid Complexes

AF3 achieves higher accuracy in predicting protein-nucleic acid complexes and RNA structures compared to specialized state-of-the-art tools like RoseTTAFold2NA and AIchemyRNA (the best AI submission of CASP15) on CASP15 examples and a PDB protein-nucleic acid dataset [9]. However, on the CASP15 benchmark, the best human-expert-aided AIchemyRNA2 performed slightly better than AF3 [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Benchmarking Protocols

Key experiments evaluating AF3's performance follow standardized protocols:

PoseBusters Protein-Ligand Benchmark:

- Dataset: 428 protein-ligand structures from PDB released in 2021 or later [3]

- Metric: Percentage of protein-ligand pairs with pocket-aligned ligand root mean squared deviation (RMSD) < 2Å

- Comparison Groups: True blind docking methods (similar inputs to AF3) and traditional docking tools that use structural information from solved complexes [3]

Antibody-Antigen Docking Evaluation:

- Dataset: Curated benchmark sets of bound and unbound antibodies/nanobodies from SAbDab, filtered by AF3's training set cutoff with quality and redundancy filtering [7]

- Metrics: DockQ score categorizing predictions as incorrect (DockQ<0.23), acceptable (0.23-0.49), medium (0.49-0.8), or high accuracy (≥0.8) [7]

- Sampling: Typically 1-3 seeds for standard evaluation, with DeepMind reporting results with up to 1,000 seeds [7]

Cross-Docking and Apo-Docking Challenges:

- Cross-docking: Ligands docked to alternative receptor conformations from different ligand complexes [1]

- Apo-docking: Uses unbound (apo) receptor structures from crystal structures or computational predictions [1]

- Significance: These represent realistic drug discovery scenarios where proteins undergo conformational changes upon binding [1]

Critical Analysis of Experimental Findings

While benchmarks show impressive performance, several studies note important limitations:

- Physical Realism: AF3 predictions show "major inconsistencies/deviations from experiment in the compactness of the complex, the intermolecular directional polar interactions (>2 hydrogen bonds are incorrectly predicted) and interfacial contacts" [14]

- Sampling Limitations: Single seed sampling yields limited success (34.7% for antibodies), requiring extensive sampling (1,000 seeds) to achieve 60% success rates [7]

- Generalization Challenges: Performance drops when docking to apo structures or handling significant conformational changes [1]

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Resources for AlphaFold-Based Studies

| Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Server | Web Platform | Free academic access for non-commercial prediction of complexes [10] |

| PDBbind | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes for training and benchmarking [1] |

| PoseBusters | Benchmarking Suite | Validates structural plausibility and assesses prediction quality [3] |

| SAbDab | Database | Structural antibody database for antibody-specific benchmarks [7] |

| UniProt | Database | Protein sequences and annotations for MSA construction [9] |

Research Workflow Integration

For pose prediction research, integrating AF3 requires careful consideration:

Input Preparation:

- Proteins: Amino acid sequences

- Nucleic acids: Nucleotide sequences

- Small molecules: SMILES strings [3]

- Modified residues: Specification of modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation, etc.)

Quality Evaluation:

- Confidence metrics: pLDDT (per-residue confidence), pTM (predicted TM-score), ipTM (interface pTM) [3] [15]

- Structural validation: Clash scores, bond geometry, steric interactions [1]

Hybrid Approaches:

- Use AF3 for initial pose generation followed by physics-based refinement [1] [14]

- Combine with molecular dynamics for ensemble generation [14]

- Integrate with binding affinity prediction tools [1]

Architectural Workflow Visualization

Architecture Evolution from AF2 to AF3 - This diagram illustrates the fundamental architectural shift from AlphaFold 2's Evoformer-based processing to AlphaFold 3's Pairformer and diffusion-based approach, highlighting the expansion from protein-only to general biomolecular modeling.

The architectural evolution from AlphaFold 2's Evoformer to AlphaFold 3's diffusion model represents a significant advancement in biomolecular structure prediction. The key advantages of AF3 include:

- Broader Biomolecular Scope: Capacity to model nearly all molecular types in the PDB within a unified framework [3]

- Improved Accuracy: Substantially higher accuracy across most interaction categories compared to specialized tools [3]

- Physical Plausibility: Elimination of explicit stereochemical constraints while maintaining physically realistic structures [3]

However, important limitations remain for researchers considering AF3 for pose prediction:

- Sampling Intensity: High accuracy often requires extensive sampling (many seeds) [7]

- Dynamic Processes: Provides structural snapshots rather than dynamic conformational changes [10]

- Commercial Restrictions: Limited availability for commercial drug discovery [10]

- RNA Challenges: Mixed performance on RNA structure prediction [10]

For molecular docking research, AF3 represents a powerful tool that excels at generating accurate initial poses but benefits from integration with physics-based refinement methods and experimental validation. The architectural shift from domain-specific parameterizations to a universal diffusion approach suggests a promising direction for future biomolecular modeling, though careful validation remains essential, particularly for therapeutic applications.

In the field of computational drug discovery, the prediction of protein-ligand binding poses represents a fundamental challenge with significant implications for pharmaceutical development. Researchers increasingly rely on two divergent methodological paradigms: deep learning-based co-folding models like AlphaFold 3 and physics-based molecular docking approaches. However, a critical but often overlooked factor unites these seemingly disparate methodologies—their shared dependence on the quality and composition of the training data they utilize. At the center of this data ecosystem sits PDBbind, a curated database of protein-ligand complexes and their binding affinities that has become the de facto standard for training and validating predictive models. While this resource has been invaluable to the community, evidence suggests that the database's structural artifacts, statistical anomalies, and organization may inadvertently encourage models to memorize specific data patterns rather than learn the underlying physics of molecular interactions. This review examines how PDBbind's characteristics shape the learning behaviors of both deep learning and traditional docking approaches, with profound implications for their real-world performance in pose prediction research.

PDBbind Under the Microscope: Structural and Statistical Challenges

Documented Data Quality Issues

The PDBbind database, while instrumental in advancing computational drug discovery, suffers from several documented quality concerns that may compromise the accuracy and generalizability of models trained upon it. A recent analysis of PDBbind v2020 revealed several common structural artifacts affecting both proteins and ligands, including incorrect bond orders, unreasonable protonation states, and missing atoms in protein chains [16]. Perhaps more critically, the database contains severe steric clashes between protein and ligand heavy atoms at distances closer than 2 Ångstroms, which represent physically implausible non-covalent interactions that can misdirect the learning process of predictive algorithms [16].

The curation process itself presents additional challenges. The PDBbind data processing procedure is neither open-sourced nor automated, potentially relying on manual intervention that can introduce inconsistencies across different entries [16]. This lack of transparency and standardization complicates efforts to reproduce results or identify systematic errors in the dataset.

The Data Leakage Problem

Perhaps the most significant challenge for rigorous model evaluation is the issue of data leakage within PDBbind's standard data splits. The general, refined, and core datasets are cross-contaminated with proteins and ligands exhibiting high similarity [17]. This contamination artificially inflates performance metrics when models are tested on protein-ligand complexes that closely resemble those in their training data, creating a false confidence in their predictive capabilities for truly novel targets [17].

The conventional random splitting of PDBbind into training and test sets fails to account for similarities in protein sequences and ligand chemical structures, allowing models to perform well through a form of "short-term memorization" of analogous patterns rather than genuinely learning the principles of molecular recognition [17]. This problem persists even in time-based splits, as new drugs frequently target established protein families, and existing compounds are often tested against new protein targets [17].

Experimental Evidence: Case Studies in Data Dependency

HiQBind-WF: A Diagnostic Workflow

In response to PDBbind's structural issues, researchers developed HiQBind-WF, a semi-automated workflow that diagnoses and corrects common artifacts in protein-ligand complexes [16]. The workflow employs multiple filtering modules to create higher-quality datasets:

- Covalent Binder Filter: Excludes ligands covalently bound to proteins, focusing specifically on non-covalent interactions [16]

- Rare Element Filter: Removes ligands containing elements beyond H, C, N, O, F, P, S, Cl, Br, I to reduce data sparsity [16]

- Small Ligand Filter: Excludes ligands with fewer than 4 heavy atoms, eliminating small inorganic binders beyond typical drug discovery scope [16]

- Steric Clashes Filter: Discards structures with protein-ligand heavy atom pairs closer than 2 Å, removing physically impossible interactions [16]

When applied to PDBbind v2020, this workflow demonstrated significant corrections to structural imperfections, suggesting that models trained on the original dataset may learn from—and potentially memorize—erroneous structural features [16].

LP-PDBBind: Addressing Data Leakage

The Leak Proof PDBBind (LP-PDBBind) dataset represents a systematic effort to reorganize PDBbind to control for data leakage [17]. This approach implements similarity control on both proteins and ligands across training, validation, and test sets, ensuring that models are evaluated on truly novel complexes rather than variations of familiar patterns [17]. The cleaning process also removes covalent complexes and resolves energy unit inconsistencies, creating a more reliable benchmark for assessing model generalizability.

When popular scoring functions including AutoDock Vina, RF-Score, IGN, and DeepDTA were retrained on LP-PDBBind and evaluated on the independent BDB2020+ dataset, they demonstrated significantly better generalization compared to models trained on standard PDBbind splits [17]. This performance gap reveals the extent to which conventional benchmarking approaches have overestimated model capabilities due to data leakage.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Models Trained on Standard vs. Leak-Proof PDBBind

| Scoring Function | Training Dataset | Performance on PDBBind Core | Performance on BDB2020+ | Generalization Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Standard PDBBind | High | Moderate | Significant |

| AutoDock Vina | LP-PDBBind | Moderate | High | Small |

| IGN | Standard PDBBind | Very High | Moderate | Large |

| IGN | LP-PDBBind | High | High | Small |

| RF-Score | Standard PDBBind | High | Low | Very Large |

| RF-Score | LP-PDBBind | Moderate | Moderate | Small |

BindingNet: Expanding Data Diversity

The limitations of PDBbind's size and diversity have prompted efforts to create expanded datasets like BindingNet v2, which comprises 689,796 modeled protein-ligand binding complexes across 1,794 protein targets [18]. This represents a substantial expansion beyond PDBbind's approximately 19,500 complexes, offering greater chemical and structural diversity for training [16] [18].

When the Uni-Mol model was trained exclusively on PDBbind, it achieved only a 38.55% success rate (ligand RMSD < 2Å) for novel ligands with low similarity (Tanimoto coefficient < 0.3) to training examples [18]. However, when trained with progressively larger subsets of BindingNet v2, its performance improved dramatically to 64.25%, demonstrating how limited data diversity forces models to interpolate rather than generalize [18]. With the addition of physics-based refinement, the success rate further increased to 74.07% while passing PoseBusters validity checks [18].

Table 2: Performance Improvement with Expanded Training Data (Uni-Mol Model)

| Training Dataset | Success Rate (Novel Ligands) | Passes PoseBusters Validity | Generalization Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBbind only | 38.55% | No | Low |

| PDBbind + BindingNet v2 (small) | 54.21% | Partial | Moderate |

| PDBbind + BindingNet v2 (medium) | 57.71% | Partial | Moderate |

| PDBbind + BindingNet v2 (full) | 64.25% | Yes | High |

| PDBbind + BindingNet v2 + Physics Refinement | 74.07% | Yes | Very High |

AlphaFold 3 vs. Molecular Docking: A Data-Divide Perspective

AlphaFold 3's Co-Folding Approach

AlphaFold 3 represents a significant advancement in structure prediction through its unified deep-learning framework that jointly models complete molecular complexes [3]. By employing a diffusion-based architecture, AF3 predicts the raw atom coordinates of complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues without relying on rotational frames or torsion angle representations [3] [19]. This approach demonstrates substantially improved accuracy over previous specialized tools, achieving approximately 81% accuracy on blind docking benchmarks compared to 38% for DiffDock and 60% for AutoDock Vina when the binding site is provided [6] [3].

However, AF3's performance appears contingent on patterns in its training data. When subjected to adversarial examples based on physical principles, the model demonstrates notable discrepancies in protein-ligand structural predictions [6]. In binding site mutagenesis challenges where all contact residues were replaced with glycine or phenylalanine, AF3 continued to predict similar binding modes despite the removal of crucial interactions, suggesting potential overfitting to specific data features in its training corpus [6].

Molecular Docking's Physical Priors

Traditional molecular docking approaches like AutoDock Vina employ physics-inspired scoring functions that explicitly model intermolecular interactions such van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic complementarity [20] [17]. While these methods generally show lower pose prediction accuracy than AF3 on standard benchmarks, they maintain more consistent performance across structural variations because their physical priors provide a form of regularization against memorization [6] [17].

The performance gap between these approaches narrows significantly when evaluated under rigorous data splitting protocols. Docking methods show less performance degradation than deep learning models when moving from standard PDBbind benchmarks to truly independent test sets, suggesting that their physical basis provides better generalization to novel targets [17].

The Hybrid Future

Emerging research suggests that the most promising path forward may integrate both approaches. One study combined deep learning pre-screening with molecular docking validation to identify potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors [20]. This hybrid framework leveraged the pattern recognition strength of deep learning with the physical plausibility guarantees of docking, ultimately identifying Enasidenib as a promising candidate that met all selection criteria [20].

Similarly, the integration of physics-based refinement with deep learning pose prediction in the BindingNet study increased success rates by nearly 10 percentage points while ensuring physical validity [18]. These approaches acknowledge that while deep learning can identify promising regions of chemical space, physical simulation remains essential for verifying mechanistic plausibility.

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Evaluation

Binding Site Mutagenesis Protocol

To assess whether models learn physical principles or memorize training examples, researchers have developed a binding site mutagenesis protocol [6]:

- Select a protein-ligand complex with a known crystal structure (e.g., ATP binding to CDK2)

- Systematically mutate binding site residues through increasingly drastic perturbations:

- Replace all contact residues with glycine to remove side-chain interactions

- Replace all contact residues with phenylalanine to sterically occlude the pocket

- Replace each residue with chemically dissimilar alternatives to alter shape and properties

- Predict the ligand binding pose for each mutated complex using the model being evaluated

- Measure the RMSD between predicted poses and the original crystal structure reference

- Identify steric clashes and physically implausible interactions in the predictions

Models that understand physics should predict ligand displacement when favorable interactions are removed, while models that memorize training data will continue predicting similar binding modes despite unfavorable conditions [6].

Time-Split Cross-Validation Protocol

To properly evaluate generalization to novel targets, researchers recommend a time-split cross-validation approach [17]:

- Collect protein-ligand complexes from PDBbind and timestamp them by their deposition date

- Train models exclusively on complexes deposited before a specific cutoff date (e.g., 2019)

- Evaluate model performance on complexes deposited after the cutoff date

- Calculate similarity metrics between training and test complexes using:

- Protein sequence alignment scores

- Ligand chemical similarity (Tanimoto coefficients)

- Binding site structural similarity

- Stratify performance results by similarity levels to identify performance cliffs

This protocol more closely mimics real-world drug discovery scenarios where models are applied to newly determined targets rather than variations of familiar ones [17].

Visualization of Methodologies and Relationships

The diagram below illustrates the core methodologies and their relationship to training data in protein-ligand pose prediction.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDBbind | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding affinities | ~19,500 complexes; standard benchmark; includes "general", "refined", and "core" subsets [16] |

| HiQBind-WF | Computational workflow | Corrects structural artifacts in protein-ligand complexes | Fixes bond orders, protonation states, missing atoms; removes steric clashes [16] |

| LP-PDBbind | Reorganized dataset | Data splits controlling for protein/ligand similarity | Prevents data leakage; enables true generalization assessment [17] |

| BindingNet v2 | Expanded dataset | Modeled protein-ligand complexes | 689,796 complexes across 1,794 targets; expands chemical diversity [18] |

| AlphaFold Server | Web service | Predicts biomolecular complex structures | Free academic access; handles proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules [10] |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking software | Predicts ligand binding modes and affinities | Physics-inspired scoring; widely used; open source [20] [17] |

| PoseBusters | Validation suite | Checks physical plausibility of predicted complexes | Detects steric clashes, bond length violations, other artifacts [3] [18] |

| BindingDB | Database | Binding affinity data for drug targets | 2.9 million measurements; useful for independent testing [16] [17] |

The evidence reviewed demonstrates that PDBbind's structural artifacts and organizational limitations significantly influence both deep learning and traditional docking approaches in protein-ligand pose prediction. The database's quality issues can lead models to memorize erroneous structural patterns, while its standard data splits artificially inflate performance metrics through data leakage. These challenges manifest differently across methodological approaches: deep learning models like AlphaFold 3 achieve remarkable accuracy but show unexpected physical inconsistencies under adversarial testing, while molecular docking methods offer greater robustness to novel targets but generally lower peak performance.

Moving forward, the field requires three key developments: (1) more rigorous benchmarking protocols that control for data leakage and similarity, such as time-split validation and adversarial testing; (2) continued expansion and curation of diverse, high-quality datasets that better represent the true chemical space of drug discovery; and (3) hybrid approaches that leverage the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning while maintaining the physical plausibility offered by traditional methods. By directly addressing the training data divide, researchers can develop more generalizable and reliable pose prediction methods that accelerate drug discovery rather than simply mastering existing datasets.

The prediction of protein-ligand interactions represents a critical frontier in computational biology and drug discovery. This field is currently defined by two fundamentally distinct approaches: the emerging paradigm of holistic complex prediction exemplified by AlphaFold 3, and the established framework of pose and affinity scoring characteristic of traditional molecular docking methods. AlphaFold 3 represents a transformative shift from specialized prediction tools to a unified deep-learning framework capable of modeling complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues simultaneously [3]. In contrast, molecular docking methods primarily focus on predicting ligand binding poses and estimating binding affinities within predefined binding sites, typically treating proteins as relatively rigid structures [1].

This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance characteristics, methodological foundations, and practical applications of these competing approaches. We examine whether AlphaFold 3's revolutionary architecture translates to consistent practical advantages across diverse drug discovery scenarios, or whether specialized docking methods maintain superiority for specific tasks like affinity prediction and drug-like molecule screening.

Performance Comparison

Table 1: Overall performance comparison on the PoseBusters benchmark

| Method | Input Information | PB-Valid Poses (<2Å RMSD) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 (Blind) | Protein sequence + ligand SMILES | 50.3% [4] | Exceptational for blind docking; models full complexes | Lower accuracy on drug-like molecules [4] |

| AlphaFold 3 (Pocket Specified) | Protein sequence + ligand SMILES + pocket residues | 76.6% [4] | High accuracy with minimal structural information | Requires pocket knowledge; commercial use restricted [10] |

| AutoDock Vina (Standard) | Protein structure + ligand | 31.1% [4] | Widely available; fast computation | Lower accuracy on natural ligands [4] |

| Strong Baseline (Vina + Ensemble + Gnina) | Protein structure + ligand + multiple conformations | 69.4% [4] | Superior on drug-like molecules; open access | Requires experimental protein structure [4] |

| DiffDock | Protein structure + ligand | 38% [6] | State-of-the-art prior to AF3 | Lower overall accuracy compared to AF3 [6] |

Specialized Application Performance

Table 2: Performance across specific biological contexts

| Application Domain | Method | Performance Metrics | Context Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Antigen Docking | AlphaFold 3 (single seed) | 10.2% high-accuracy (DockQ ≥0.8), 34.7% overall success [7] | Improves over AF2-Multimer (2.4% high-accuracy); reaches 60% success with 1000 seeds [7] |

| Nanobody-Antigen Docking | AlphaFold 3 (single seed) | 13.3% high-accuracy, 31.6% overall success [7] | Outperforms Boltz-1 (5%) and Chai-1 (3.33%) on high-accuracy predictions [7] |

| Common Natural Ligands | AlphaFold 3 | Exceptional performance [4] | Molecules highly represented in PDB training data (nucleotides, nucleosides, etc.) [4] |

| Drug-like Molecules (excluding common natural ligands) | Strong Baseline (Vina + Ensemble + Gnina) | 8.5% above AF3 [4] | More representative of typical small-molecule therapeutics [4] |

| Halogenated Compounds (69 PoseBusters ligands) | Strong Baseline | 84.1% PB-valid with RMSD<2Å [4] | Performance on molecules rare in training data |

Methodological Foundations

AlphaFold 3 Architectural Framework

AlphaFold 3 employs a substantially updated diffusion-based architecture that replaces the complex structural module of AlphaFold 2. The system combines a simplified pairformer module with a diffusion network that operates directly on raw atom coordinates, eliminating the need for amino-acid-specific frames and stereochemical violation penalties [3]. The model uses a cross-distillation training approach, enriching training data with structures predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer to reduce hallucination behavior in unstructured regions [3].

The inputs to AlphaFold 3 are notably minimal—requiring only molecular sequences (for proteins, nucleic acids) and SMILES strings (for small molecules)—and the system simultaneously models the complete assembly rather than docking components sequentially [10] [3]. This holistic approach captures the cooperative reshaping that occurs when molecules interact in biological systems.

Traditional Molecular Docking Framework

Traditional docking methods follow a search-and-score paradigm, exploring possible ligand conformations and orientations within a defined binding site, then ranking these poses using scoring functions that estimate binding affinity [1]. These methods exist on a spectrum of flexibility—from rigid-body docking to approaches that allow limited ligand and protein flexibility.

The "strong baseline" approach referenced in Table 1 enhances traditional docking through two key modifications: using ensemble conformations of ligands to ensure adequate sampling of ring geometries and other inflexible regions, and employing machine learning-based rescoring (Gnina) to improve pose selection beyond what traditional scoring functions like Vina provide [4].

Experimental Protocols

PoseBusters Benchmark Methodology

The PoseBusters benchmark established a standardized framework for evaluating protein-ligand complex prediction methods. The test set comprises 428 protein-ligand structures released to the PDB in 2021 or later, ensuring temporal separation from training data for most methods [3]. Evaluation metrics include:

- RMSD <2Å: The classic metric for docking success, measuring heavy-atom root-mean-square deviation after optimal alignment of the binding pocket.

- PB-Valid: A more comprehensive quality check that includes stereochemical validity, absence of severe clashes, and overall physical plausibility [4].

For AlphaFold 3 evaluation, the model was tested in two configurations: truly blind (using only sequence information) and pocket-specified (provided with protein residues constituting the binding site) [4]. Traditional docking methods were evaluated using experimentally determined protein structures.

Adversarial Testing Protocol

Recent research has subjected AlphaFold 3 to adversarial testing to evaluate its understanding of physical principles rather than statistical correlations [6]. The binding site mutagenesis protocol systematically challenges the model:

- Residue Selection: Identify all binding site residues forming contacts with the ligand in the native structure.

- Progressive Mutation:

- Challenge 1: Replace all binding site residues with glycine (removing side-chain interactions)

- Challenge 2: Replace all binding site residues with phenylalanine (steric occlusion)

- Challenge 3: Replace with chemically dissimilar residues (altering shape and chemical properties)

- Evaluation: Measure whether the model adjusts predictions according to physical principles or maintains poses based on training set statistics [6].

Results revealed that co-folding models frequently maintain ligand placement even after removing favorable interactions, indicating potential overfitting to specific system geometries present in training data [6].

Critical Analysis

Physical Realism and Generalization

While AlphaFold 3 demonstrates exceptional accuracy on standard benchmarks, adversarial testing reveals significant limitations in physical understanding. When binding site residues are mutated to glycine, removing key interactions, AlphaFold 3 often continues to predict similar binding poses as if those interactions were still present [6]. In more extreme cases where residues are mutated to phenylalanine, the model sometimes predicts structures with unphysical atomic clashes, indicating difficulty resolving severe steric conflicts within the diffusion process [6].

This suggests that AlphaFold 3's performance derives partly from pattern recognition of complexes in its training set rather than true physical reasoning about molecular interactions. The model appears to learn which ligands tend to bind to particular protein pockets rather than fundamentally understanding how chemical forces dictate binding geometry [6].

Data Dependence and Transferability

Performance analysis reveals substantial variation across molecule types. AlphaFold 3 excels with common natural ligands like nucleotides and cofactors that are well-represented in the Protein Data Bank [4]. However, its advantage diminishes for synthetic drug-like molecules, particularly those containing halogens or other uncommon functional groups [4].

This pattern suggests that data representation in training significantly influences model performance. The "strong baseline" docking approach outperforms AF3 on molecules excluding common natural ligands (69.4% vs 50.3% for blind AF3) [4], indicating that traditional methods may currently be more reliable for typical drug discovery applications involving novel chemical matter.

Practical Considerations for Drug Discovery

For researchers selecting between these approaches, several practical considerations emerge:

- Structural Information Availability: AlphaFold 3 provides remarkable capabilities when experimental protein structures are unavailable, while traditional docking requires high-quality protein structures.

- Computational Resources: AlphaFold 3 demands significant computational resources, especially for large complexes or multiple sampling seeds, whereas traditional docking is relatively lightweight.

- Commercial Applications: AlphaFold 3's current license restricts commercial use, while traditional docking tools are generally open-source or commercially available.

- Dynamic Information: Neither approach adequately captures protein flexibility and dynamics, though traditional docking can be combined with molecular dynamics simulations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools for protein-ligand interaction studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Server | Web Server | Holistic complex prediction with minimal input | Free academic access via web interface [10] |

| AutoDock Vina | Software Suite | Traditional molecular docking with empirical scoring | Open-source download [4] |

| Gnina | Software Tool | Machine learning-based pose rescoring | Open-source framework [4] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Ligand conformation generation and manipulation | Open-source Python library [4] |

| PoseBusters | Validation Suite | Standardized benchmark for docking methods | Python package [4] |

| PDBBind | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes for training/testing | Academic license [1] |

The comparison between AlphaFold 3's holistic complex prediction and traditional pose and affinity scoring reveals a nuanced landscape where each approach excels in different scenarios. AlphaFold 3 represents a revolutionary capability for blind prediction of biomolecular complexes, particularly when structural information is limited or for natural biomolecules. However, traditional docking methods, especially when enhanced with machine learning rescoring and conformational ensembles, maintain competitive performance for drug-like molecules and benefit from greater accessibility, speed, and commercial usability.

The optimal approach for research and drug discovery likely involves strategic combination of these technologies—using AlphaFold 3 for initial target assessment and binding site identification, then employing refined docking methods for detailed pose prediction and optimization of novel chemical entities. As both methodologies continue to evolve, the integration of physical principles with data-driven pattern recognition will likely bridge the current gaps, enabling more robust and predictive modeling of protein-ligand interactions across the chemical and biological spectrum.

Performance and Practical Application in Biomolecular Modeling

The accurate prediction of how a small molecule (ligand) binds to its target protein is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. For years, classical docking tools like AutoDock Vina have been the standard for this task. The recent release of AlphaFold 3 (AF3), a deep learning model capable of predicting protein-ligand complexes from sequence alone, promises a paradigm shift [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the docking accuracy between AF3 and traditional molecular docking methods, focusing on the critical metrics of ligand Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) and success rates on standard benchmarking datasets. The analysis is framed within the broader thesis of evaluating the role of AI-driven versus physics-based methods in structural bioinformatics.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance of a docking tool is primarily measured by its ability to produce a ligand pose that is close to the experimentally determined structure. A common threshold for a "successful" prediction is a ligand RMSD of less than 2.0 Å when the predicted pose is aligned to the protein's binding pocket.

The table below summarizes the performance of AF3 and various docking methods on the PoseBusters benchmark, a curated set of protein-ligand structures released after AF3's training data cutoff, ensuring an unbiased evaluation [21] [4].

Table 1: Success Rate (% of complexes with pocket-aligned ligand RMSD < 2.0 Å) on the PoseBusters Benchmark

| Method | Input Type | Reported Success Rate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 (Blind) | Protein Sequence + Ligand SMILES | ~48% | No protein structure input [3] [4] |

| AlphaFold 3 (Pocket Specified) | Protein Sequence + Ligand SMILES + Pocket Residues | ~62% | Protein residues near the ligand are specified [4] |

| AutoDock Vina (Baseline) | Protein Structure + Ligand Structure | ~33% | As reported in PoseBusters and AF3 papers [22] [3] |

| Strong Baseline (Vina + Ensembles + Gnina) | Protein Structure + Ligand Structure | ~52% | Uses an ensemble of ligand conformations & neural network rescoring [4] |

Performance can vary significantly with the type of ligand being docked. AF3 demonstrates particular strength on "common natural ligands" (e.g., nucleotides), which are well-represented in its training data. In contrast, traditional docking shows more consistent performance across diverse, drug-like molecules [4].

Table 2: Performance on Different Ligand Types within the PoseBusters Benchmark

| Method | Common Natural Ligands (n=50) | Other Ligands (More Drug-like) |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 (Blind) | Higher Performance | Lower Performance |

| Strong Docking Baseline | Lower Performance | ~8.5% higher than blind AF3 |

Beyond general small molecules, benchmarking on specific pollutant compounds like Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) reveals another nuance. AF3's performance was notably higher on data it was trained on ("Before Set": ~74.5% success) compared to unseen data ("After Set": ~55.8% success), indicating potential overfitting. A hybrid approach, using AF3 to identify the binding pocket and Vina for the final pose prediction, proved to be a successful strategy [22].

Experimental Protocols and Metrics

Standard Benchmarking Datasets

The reliability of any performance claim hinges on the use of rigorous, non-overlapping datasets.

- PoseBusters Benchmark: This is a key modern benchmark comprising 428 protein-ligand complexes from the PDB released in 2021 or later. It is designed to test methods on structures not used in their training, providing a fair assessment of generalizability [3] [21].

- Curated PDB Sets: Studies often create their own benchmarks from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). A critical practice is splitting data into "Before" and "After" sets based on a model's training cutoff date (e.g., September 30, 2021, for AF3) to evaluate performance on seen versus unseen data [22].

- Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD): While primarily used for evaluating virtual screening enrichment (distinguishing binders from non-binders), the principles of DUD—using physically similar but chemically distinct decoys—inform the creation of stringent docking benchmarks [23].

Key Performance Metrics

- Ligand RMSD: The most direct metric for pose accuracy. It measures the average distance between the atoms of the predicted ligand pose and the experimentally determined (native) pose after aligning the protein's binding pocket atoms. A lower RMSD indicates a more accurate prediction.

- Success Rate: The percentage of complexes in a benchmark for which the ligand RMSD is below a chosen threshold (typically 2.0 Å).

- Protein-Ligand Interaction Fidelity (PLIF): Beyond RMSD, recovering the specific hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and other interactions found in the native structure is crucial. A pose with good RMSD may still have incorrect interactions, which can mislead drug design. Studies show that classical docking methods, whose scoring functions explicitly seek these interactions, often achieve better PLIF recovery than some ML methods that only use RMSD-derived loss functions [21].

Method Workflows

The workflow for benchmarking varies significantly between AF3 and classical docking tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To conduct a rigorous docking benchmark, researchers require both software tools and carefully curated data.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Docking Benchmarking Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Benchmarking | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmarking Datasets | Data | Provides standardized, non-overlapping complexes for fair evaluation of method performance and generalizability. | PoseBusters Benchmark [21], PDB "After Sets" [22] |

| Structure Preparation Tools | Software | Prepares protein and ligand structures for docking by adding hydrogens, assigning charges, and minimizing conflicts. | PDBFixer [22], OpenBabel [22], Spruce (OpenEye) [21] |

| Classical Docking Suites | Software | Provides physics-inspired or knowledge-based algorithms for conformational sampling and pose scoring. | AutoDock Vina [22], Gnina [4], GOLD [21] |

| AI-Based Prediction Tools | Software | Predicts complex structures end-to-end from sequence and SMILES string, often with high speed. | AlphaFold 3 Server [3], DiffDock-L [21] |

| Interaction Analysis Packages | Software | Analyzes and compares predicted poses against ground truth by calculating interaction fingerprints. | ProLIF [21] |

| Analysis Metrics | Scripts/Metrics | Quantifies the accuracy of predicted poses through structural alignment and interaction recovery. | RMSD, Success Rate, Protein-Ligand Interaction Fidelity (PLIF) [21] |

The benchmarking data leads to several key conclusions for researchers:

- AlphaFold 3's Niche: AF3 is a revolutionary tool for blind docking, where a protein structure is unavailable, achieving remarkable accuracy using only sequence information. It performs exceptionally well on ligand types common in its training data.

- Classical Docking's Resilience: When a high-quality experimental protein structure is available, strengthened classical docking pipelines that use conformational ensembles and machine learning-based rescoring (e.g., with Gnina) can match or even exceed the performance of the blind version of AF3, especially on drug-like molecules.

- The Power of Hybrids: A promising strategy is a hybrid approach, using AF3's strengths in pocket identification and then refining the pose with physics-based tools like Vina, which has shown improved results for challenging molecules like PFAS [22].

- Look Beyond RMSD: For critical drug discovery applications, evaluating protein-ligand interaction fingerprints (PLIF) is essential, as a good RMSD does not guarantee the recovery of key biochemical interactions [21].

In summary, AF3 has not rendered traditional docking obsolete but has instead expanded the toolkit. The choice between them is context-dependent. For the foreseeable future, integrating the predictive power of deep learning with the physicochemical rigor of classical methods will likely provide the most robust and reliable strategy for protein-ligand pose prediction.

The accurate computational prediction of how biomolecules interact is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and basic biological research. For years, molecular docking—a physics-inspired method that leverages known protein structures to predict where and how small molecules bind—has been the dominant technique. The recent emergence of deep learning systems like AlphaFold 3 (AF3) represents a paradigm shift, offering a unified approach to predicting the joint 3D structures of diverse biomolecular complexes directly from their sequence information. This guide provides an objective comparison of AlphaFold 3 and traditional molecular docking for predicting the structures of proteins, antibodies, and nanobodies with their molecular partners, synthesizing current performance data and detailing key experimental methodologies.

AF3 employs a substantially updated architecture compared to its predecessors, capable of predicting the joint structure of complexes including proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues. Its core innovation lies in a diffusion-based approach that starts with a cloud of atoms and iteratively refines the most probable molecular structure, operating directly on raw atom coordinates without the need for complex rotational adjustments [3] [24]. This allows AF3 to handle arbitrary chemical components while maintaining chemical plausibility. In contrast, traditional docking tools like Vina rely on physics-based scoring functions and require an experimentally determined protein structure as a starting point, which can be a significant limitation in early-stage research [4].

Performance Comparison: AlphaFold 3 vs. Molecular Docking

The most cited benchmark for protein-ligand docking is the PoseBusters set, comprising 428 protein-ligand structures released to the PDB in 2021 or later. The results demonstrate AF3's strong performance, particularly given that it operates without structural inputs.

Table 1: Protein-Ligand Docking Accuracy on the PoseBusters Benchmark

| Method | Input Requirements | PB-Valid & RMSD <2Å (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 (Blind) | Protein sequence, Ligand SMILES | 26.3% | No structural information used [3] |

| AlphaFold 3 (Pocket Specified) | Protein sequence, Ligand SMILES, Protein residues near ligand | 33.6% | Still uses sequence, not 3D structure [4] |

| Vina (Baseline) | Experimental protein structure, Ligand | 11.1% | Original baseline from PoseBusters paper [4] |

| Strong Baseline (Vina + Gnina) | Experimental protein structure, Ligand conformational ensemble | 30.3% | Combines ensemble docking & neural network rescoring [4] |

A critical analysis reveals that while the AF3 paper showed it "greatly outperforms classical docking tools like Vina," the Vina baseline does not represent the state-of-the-art in traditional docking. When strengthened with standard improvements—using an ensemble of ligand starting conformations and rescoring poses with the neural network-based Gnina—the performance of traditional docking nearly matches that of the pocket-specified version of AF3 [4]. This strong baseline uses a earlier training data cutoff than AF3, ensuring a fair comparison.

Performance varies significantly by ligand type. AF3 demonstrates exceptional performance on "common natural ligands" (e.g., nucleosides, nucleotides), which are highly represented in its training data due to their frequent occurrence in the PDB. However, the strengthened baseline outperforms AF3 on the remaining molecules, which may be more representative of typical drug-like compounds [4].

Antibody and Nanobody Complex Prediction

Antibody and nanobody docking presents a unique challenge due to the flexibility of their complementary-determining regions (CDRs), particularly the highly diverse CDR H3 loop. Accurate prediction here is critical for therapeutic development.

Table 2: Antibody and Nanobody Docking Success Rates (DockQ ≥0.23)

| Method | Antibody-Antigen Success Rate | Nanobody-Antigen Success Rate | Sampling Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 | 34.7% | 31.6% | Single seed [7] |

| AlphaFold 3 (with 1000 seeds) | ~60% | Not reported | Extensive sampling [7] |

| AlphaFold 2.3-Multimer | 23.4% | Not reported | Standard [7] |

| Boltz-1 (AF3-like) | 20.4% | 23.3% | Single seed [7] |

| Chai-1 (AF3-like) | 20.4% | 15.0% | Single seed [7] |

| AlphaRED (Hybrid) | 43% | Not reported | Combines AF2 with replica exchange docking [25] |

AF3 shows a clear improvement over AF2-Multimer, but its success rate with a single seed remains limited at 34.7%. However, its performance can nearly double with extensive sampling (1,000 seeds), highlighting the stochastic nature of the diffusion model [7]. This comes at a significant computational cost. The hybrid method AlphaRED, which combines AF2 structural templates with physics-based replica exchange docking, achieves a higher success rate on antibody-antigen targets, demonstrating the value of integrating deep learning with physics-based sampling [25].

For nanobodies, the overall success rate of both AF3 and AF2-Multimer remains below 50%, though AF3 shows a modest overall improvement. Accuracy is heavily influenced by the characteristics of the CDR3 loop, particularly its 3D spatial conformation and length [26].

Linear Epitope Prediction with AlphaFold-based Pipelines

For predicting linear antibody epitopes (short, contiguous peptide sequences bound by antibodies), specialized pipelines built upon AlphaFold2 have been developed. The PAbFold pipeline uses the localColabFold implementation of AF2 to predict the structure of a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) in complex with overlapping peptides derived from an antigen [27] [28]. This method has been experimentally validated to accurately flag known epitope sequences for well-characterized antibodies and for a novel anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody, with predictions verified via peptide competition ELISA [28]. The computational expense scales with the square of the concatenated sequence length, making the use of minimized scFvs and short peptides efficient (approximately 1.5 minutes per scFv-peptide complex on an NVIDIA A5000 GPU) [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard AlphaFold 3 Protocol for Complex Prediction

The standard workflow for using AF3 to model a biomolecular complex involves several key steps. The required inputs are the sequences of all polymeric components (e.g., protein, DNA, RNA) and the SMILES string for any small molecule ligands. The process is managed through the AlphaFold Server, which is designed to be accessible to scientists.

The model's architecture begins by processing inputs through a simplified Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) module, which is substantially de-emphasized compared to AlphaFold 2. The "Pairformer" module then evolves a pairwise representation of the entire complex. Finally, the diffusion module, which replaces the structure module of AF2, generates atomic coordinates through an iterative denoising process [3]. A critical technical point is that AF3 uses a cross-distillation method during training, where it is trained on structures predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer. This teaches the model to represent unstructured regions as extended loops rather than compact hallucinations, greatly reducing a common failure mode of generative models [3].

Strong Baseline Docking Protocol

The strengthened traditional docking baseline, which performs comparably to AF3, can be implemented in approximately 100 lines of code and uses open-source tools [4]. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow, which combines the strengths of deep-learning initial sampling with physics-based refinement and selection.

Key Steps:

- Generate Conformational Ensemble: Using a cheminformatics toolkit like RDKit, generate multiple reasonable 3D starting conformations for the ligand from its SMILES string. This ensures the docking algorithm can sample correct poses even for rigid ring systems [4].

- Molecular Docking: Run the Vina docking software from each starting ligand conformation against the experimental protein structure. The exhaustiveness parameter can be reduced for each run since the ensemble provides broader sampling.

- Rescore and Select Top Poses: Pool all docked poses from the various runs and rescore them using Gnina, a convolutional neural network trained to distinguish near-native docking poses. Select the top-ranked pose based on the Gnina score, which is more accurate than Vina's native scoring function [4].

Protocol for Antibody-Antigen Docking with AlphaRED

The AlphaRED protocol is a hybrid approach that addresses the limitations of AF models for docking antibodies and other flexible complexes [25].

Workflow:

- Generate Structural Templates: Use AlphaFold-Multimer to generate a diverse set of structural models for the antibody-antigen complex.

- Estimate Flexibility and Interface Quality: Repurpose AF's confidence metrics (pLDDT and predicted aligned error) to estimate protein flexibility and identify which template models have the most reliable interfaces.

- Physics-Based Refinement: Use the best AF-generated models as starting points for the RosettaDock replica exchange docking protocol. This physics-based method extensively samples side-chain conformations, backbone flexibility, and rigid-body degrees of freedom to refine the complex.

- Select Final Models: Rank the resulting models using a combination of Rosetta's energy function and the original AF confidence metrics to produce the final, high-accuracy predictions [25].

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for Biomolecular Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Server | Web Server | Free, accessible interface for running AlphaFold 3 predictions on biomolecular complexes [24]. |

| PoseBusters Benchmark | Dataset & Software | A benchmark set of 428 protein-ligand complexes and a Python package to validate docking poses, ensuring they are <2Å from experimental structures and free of stereochemical violations [4]. |

| Gnina | Software | A molecular docking software that uses a convolutional neural network to score and select the most accurate docking poses from a pool of candidates [4]. |

| RDKit | Software | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used to generate and manipulate small molecule structures, including the creation of conformational ensembles [4]. |

| SAbDab | Database | The Structural Antibody Database, a repository of all publicly available antibody structures, used for curating benchmark sets [7]. |

| PAbFold | Software Pipeline | A computational pipeline based on AlphaFold2 and localColabFold for predicting linear antibody epitopes by modeling scFv-peptide complexes [27] [28]. |

| AlphaRED | Software Pipeline | A hybrid pipeline integrating AlphaFold with Rosetta-based replica exchange docking for reliable protein-protein and antibody-antigen docking [25]. |

The comparison between AlphaFold 3 and molecular docking reveals a nuanced landscape. AF3 is a breakthrough for blind docking, achieving high accuracy using only sequence information where traditional methods require a known protein structure. This makes it invaluable for targets with no experimentally determined structure. However, when a high-quality experimental structure of the target protein is available, strengthened traditional docking baselines can achieve comparable, and in some cases superior, accuracy, especially for drug-like molecules [4].

For antibody and nanobody docking, AF3 represents a step forward, but challenges remain. Its single-seed success rate is modest, and achieving high accuracy often requires computationally expensive massive sampling. Hybrid approaches like AlphaRED, which combine deep learning's sampling power with physics-based refinement, currently set the state-of-the-art for these difficult targets [25].

The choice between these tools is therefore context-dependent. For rapid, initial assessment of a novel target, AF3 is unparalleled. For optimizing drug candidates against a well-characterized target with an available structure, strengthened traditional docking or hybrid methods may provide superior results. The future of biomolecular modeling lies not in a single tool dominating, but in the intelligent integration of these complementary approaches to accelerate scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

The accurate prediction of biomolecular structures is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and basic biological research. For years, molecular docking has been the predominant computational method for predicting how small molecules interact with their protein targets. However, the recent advent of deep learning-based cofolding tools, like AlphaFold 3 (AF3), represents a paradigm shift. This guide provides an objective comparison of AlphaFold 3 and traditional molecular docking, focusing on their performance in predicting the poses of ligands bound to challenging target classes: RNA, membrane proteins, and proteins with flexible loops. We summarize quantitative data from recent benchmarks and detail key experimental protocols to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their pose prediction challenges.

The table below summarizes the core strengths and weaknesses of AlphaFold 3 and molecular docking across key biomolecular categories, synthesizing findings from recent evaluations [3] [10] [29].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of AlphaFold 3 vs. Molecular Docking

| Target Category | AlphaFold 3 Performance | Molecular Docking Performance | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Protein-Ligand Pose Prediction | High performance, often doubling the accuracy of traditional docking; excels in "blind" scenarios using only sequence/SMILES [3] [10]. | Variable and often lower, especially without a pre-defined holo structure; performance can be improved with fragment-derived priors or in "easy" splits [30] [29] [31]. | On the PoseBusters benchmark, AF3 significantly outperformed docking tools like Vina, with a much higher percentage of predictions within 2 Å RMSD [3]. |

| RNA Structures | Mixed to poor; identified as a weakness due to RNA's conformational flexibility [10]. | Not typically used for full RNA-ligand co-structure prediction. | AF3 struggles with RNA's context-dependent folding, and predictions in this area require extra skepticism [10]. |

| Membrane Proteins | Challenging; the model does not explicitly account for lipid bilayers, leading to potential artifacts in transmembrane regions [10]. | Performance is highly dependent on the quality and state (e.g., apo vs. holo) of the input protein structure [29]. | Critical drug targets like GPCRs modeled by AF3 need careful interpretation due to the lack of a membrane environment [10]. |

| Proteins with Flexible Loops | Can identify disordered regions but cannot predict their dynamic behavior [10]. | Performance can be poor if the loop conformation in the input structure differs significantly from the bound state (e.g., due to "induced fit") [29]. | In high-throughput docking benchmarks, even small side-chain variations in AF models compared to experimental structures consistently reduced performance [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The PoseBusters Benchmark (For AF3 and Docking)

The PoseBusters benchmark has become a standard for rigorously evaluating protein-ligand pose prediction methods [3].

- Objective: To assess the ability of a method to generate a ligand pose that matches the experimental structure, measured by the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the ligand heavy atoms after aligning the protein pocket.

- Dataset: Consists of 428 protein-ligand structures released to the PDB in 2021 or later. This time-split is crucial for testing generalizability and avoiding data leakage from the training sets of data-driven models like AF3 [3].

- Metric: The primary metric is the percentage of protein-ligand pairs with a pocket-aligned ligand RMSD of less than 2 Å, which is a common threshold for a "successful" prediction.

- Key Findings:

- AlphaFold 3: Demonstrated substantially higher accuracy than state-of-the-art docking tools, even though AF3 uses only the protein sequence and ligand SMILES string, while docking methods often use the experimental protein structure as input [3].

- Molecular Docking: Its performance is often lower in this blind setting. However, its accuracy can be boosted by incorporating data-driven priors. For example, one workflow using Vina-GPU augmented with fragment-derived priors achieved over 50% success for SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV protease targets [31].

High-Throughput Docking (HTD) on AlphaFold Models