Beyond Situs Inversus: Advanced Strategies for Detecting Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in Patients Without Laterality Defects

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) remains significantly underdiagnosed in patients who do not present with the classic hallmark of organ laterality defects.

Beyond Situs Inversus: Advanced Strategies for Detecting Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in Patients Without Laterality Defects

Abstract

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) remains significantly underdiagnosed in patients who do not present with the classic hallmark of organ laterality defects. This creates a diagnostic blind spot, particularly for the estimated 50% of PCD patients with situs solitus. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to bridge this diagnostic gap. We explore the foundational clinical phenotypes that should trigger suspicion, detail the evolving landscape of diagnostic methodologies—from nasal nitric oxide (nNO) to genetic panels and advanced imaging. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting in complex cases, optimizes referral pathways, and validates new technologies against established standards. By synthesizing current evidence and emerging innovations, this review aims to equip the biomedical community with the tools to enhance early detection, accelerate clinical trial enrollment, and pave the way for targeted therapeutic development for all PCD patients.

The Clinical Conundrum: Unmasking the PCD Phenotype Without Laterality Defects

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder of motile ciliary dysfunction that results in insufficient mucociliary clearance. The clinical presentation typically includes unexplained neonatal respiratory distress, chronic sino-oto-pulmonary congestion, and recurrent infections [1]. Nearly half of all patients with PCD have a laterality defect, such as situs inversus totalis (a complete mirror-image reversal of the thoracic and abdominal organs) or heterotaxy [2] [1]. This visible anatomical clue has historically served as a key indicator for clinicians to initiate a PCD diagnostic workup.

However, this reliance on laterality defects has created a significant epidemiological blind spot: patients who have PCD with situs solitus (normal organ arrangement) frequently remain undiagnosed or experience substantial diagnostic delays. This article examines the scale of this underdiagnosis, explores the underlying causes, and provides the scientific community with targeted troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols to enhance detection of PCD across all patient populations, particularly those without laterality defects.

Quantitative Analysis of the Diagnostic Gap

Epidemiological Data on Laterality Defects and PCD

Table 1: Epidemiology of Laterality Defects and Association with PCD

| Condition | Prevalence in Population | Prevalence of PCD within Condition | Key Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Situs Inversus Totalis | 1 in 6,500 - 1 in 25,000 births [2] [3] | 25% have Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) [3] [4] | Kartagener Syndrome triad: situs inversus, chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis [3] [5] |

| Heterotaxy (Situs Ambiguus) | ~1 in 10,000 births [2] [6] | Data insufficient but significantly increased risk [1] [6] | High prevalence (up to 100%) of complex congenital heart disease [6]. |

| Situs Solitus (Normal Anatomy) | >99.9% of population | Underdiagnosed; estimated PCD prevalence 1:10,000 - 1:25,000 [1] | Lacks the obvious anatomical red flag, leading to diagnostic oversight. |

Referral and Evaluation Rates: Revealing the Systemic Gap

A pivotal 2025 retrospective study provides the most compelling quantitative evidence of underdiagnosis. The research analyzed 369 patients with confirmed laterality defects, focusing on those who met the American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria for PCD evaluation [1].

Table 2: PCD Evaluation Rates in Patients with Laterality Defects (2025 Study Data)

| Patient Cohort | Met ≥2 ATS PCD Criteria | Referred to Pulmonary Medicine | Actually Evaluated for PCD |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients with laterality defects | 49% (n=180) | 41% | 16% |

| Patients meeting 2 criteria | 79 patients | 41% | 16% |

| Patients meeting all 4 criteria | 27 patients | 96% | 93% |

This data reveals a critical failure in the diagnostic pipeline: even when patients present with a known risk factor (a laterality defect) plus a second clinical symptom of PCD, the majority (84%) are not advanced to a definitive evaluation [1]. The study concluded that a "substantial number of pediatric patients meeting two PCD referral criteria are not referred to pediatric pulmonologists, and a larger number are not being evaluated for PCD" [1]. This demonstrates a systemic underestimation of PCD prevalence, particularly in the situs solitus population where the initial red flag of a laterality defect is absent.

FAQs: Troubleshooting PCD Diagnosis in Situs Solitus

Q1: What is the core clinical challenge in identifying PCD patients with situs solitus? A1: The primary challenge is the lack of a specific pathognomonic symptom. Clinical features like chronic cough and nasal congestion are highly common in childhood and overlap with more frequent conditions like recurrent viral infections, asthma, and allergic rhinitis [1]. Without the striking clue of situs inversus, clinicians often reasonably attribute symptoms to these more common ailments, leading to a low index of suspicion for PCD.

Q2: What are the key clinical criteria that should trigger a PCD evaluation in a patient with normal organ arrangement (situs solitus)? A2: Per the American Thoracic Society guidelines, the presence of any two of the following four criteria warrants a PCD evaluation [1]:

- Unexplained Neonatal Respiratory Distress: In a term infant, requiring oxygen or positive pressure for ≥24 hours.

- Persistent Daily Cough: Year-round, beginning before 6 months of age.

- Persistent Daily Nasal Congestion: Year-round, beginning before 6 months of age.

- An Organ Laterality Defect: Such as situs inversus or heterotaxy. (In situs solitus patients, this criterion is by definition absent, so two of the first three are required).

Q3: In a research setting, what is the recommended diagnostic workflow for confirming PCD? A3: A combination of diagnostic modalities is required for a definitive confirmation.

- Initial Screening: Measure Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO). Chronically low nNO is a strong indicator of PCD [5].

- Genetic Analysis: Perform genetic testing for pathogenic variants in known PCD-associated genes. Given genetic heterogeneity, extended or whole-genome sequencing may be necessary.

- Ciliary Ultrastructure Analysis: If genetic results are inconclusive, proceed with Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of a ciliary biopsy to assess dynein arm defects and other ultrastructural abnormalities [1] [5].

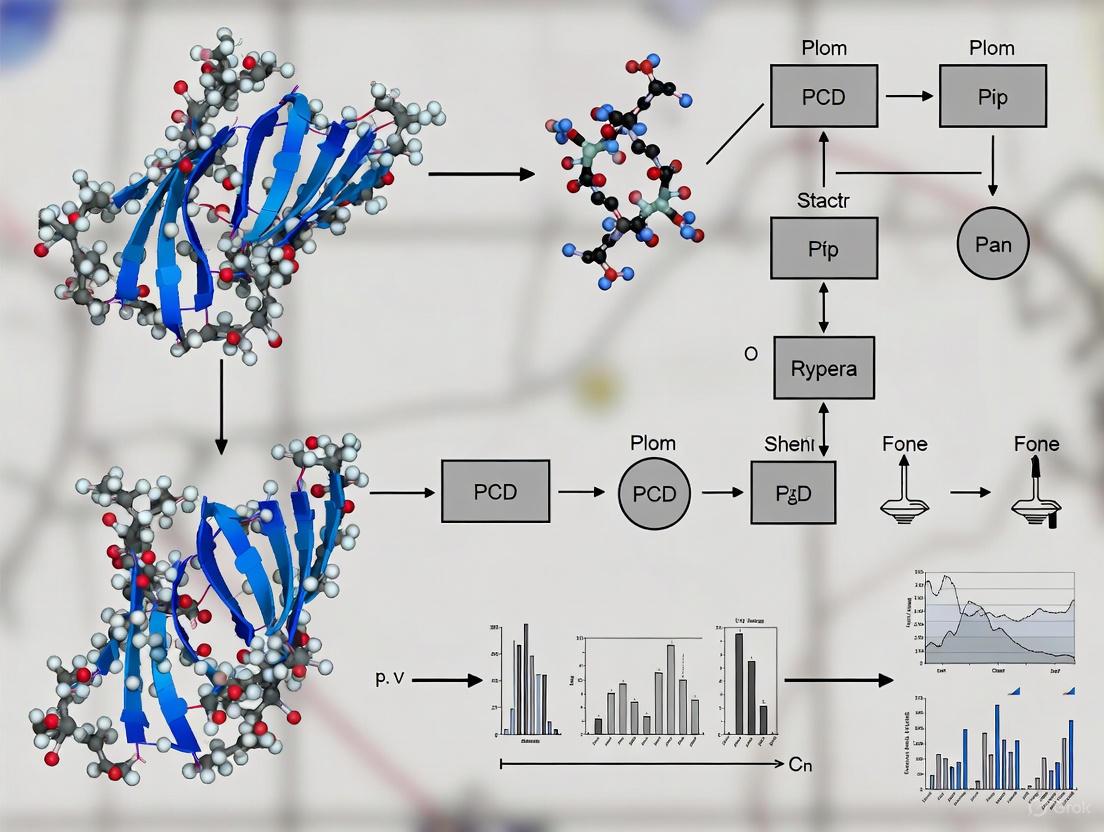

Diagram 1: Confirmatory PCD Diagnostic Workflow. This flowchart outlines the multi-modal approach required for a definitive PCD diagnosis, as per current guidelines.

Q4: Which genetic pathways and reagents are most critical for PCD research and diagnostics? A4: Over 100 genes have been linked to laterality defects, with a significant subset directly involved in PCD pathogenesis [2] [4]. Research focuses on genes affecting ciliary structure and function.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Investigation

| Reagent / Assay Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in PCD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Targeted NGS Panels (PCD-specific), Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Identification of pathogenic variants in genes like DNAH5, DNAI1, CCDC39, CCDC40, and other PCD-associated loci. |

| Antibodies for Protein Localization | Anti-DNAH5, Anti-DNALI1, Anti-GAS8 | Immunofluorescence staining to confirm protein expression and localization within ciliary axonemes. |

| Ciliary Functional Assays | High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis Systems | Quantitative and qualitative assessment of ciliary beat frequency and pattern. |

| Ultrastructural Analysis | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Reagents | Visualization of ciliary cross-sections to identify defects in outer/inner dynein arms, nexin links, etc. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Prospective Study on Situs Solitus PCD Detection

Objective: To determine the prevalence of PCD in a cohort of children with situs solitus and persistent, otherwise unexplained respiratory symptoms.

Methodology:

- Recruitment: Enroll children aged 0-18 years with situs solitus and at least two of the three clinical ATS criteria (excluding laterality defect): unexplained neonatal respiratory distress, persistent daily cough, or persistent daily nasal congestion.

- Screening Phase:

- Perform nNO measurement on all participants.

- Exclude cystic fibrosis via sweat chloride test or genetic analysis.

- Confirmatory Phase:

- All participants with low nNO proceed to the confirmatory phase.

- Perform next-generation sequencing using a comprehensive PCD gene panel.

- For participants with inconclusive genetic results, obtain a nasal brush biopsy for TEM analysis of ciliary ultrastructure.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the point prevalence of confirmed PCD within the recruited cohort.

- Analyze the sensitivity and specificity of the ATS clinical criteria in the situs solitus population.

- Characterize the genetic and ultrastructural spectrum of PCD variants identified.

Diagram 2: Situs Solitus PCD Detection Study. This workflow details a proposed research protocol to actively identify and confirm PCD in the under-diagnosed situs solitus population.

The underdiagnosis of PCD in individuals with situs solitus represents a significant epidemiological gap and a failure in clinical translation. The quantitative evidence shows that even when clear clinical criteria are met, referral and evaluation rates remain unacceptably low. Overcoming this requires a paradigm shift from a suspicion based on rare anatomical clues to one driven by systematic screening for a constellation of common, persistent respiratory symptoms beginning in infancy. By employing the detailed troubleshooting guides, standardized diagnostic workflows, and targeted research protocols outlined herein, researchers and clinicians can collaborate to close this diagnostic gap, ensure timely interventions, and ultimately generate a more accurate understanding of the true prevalence and natural history of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is "unexplained neonatal respiratory distress" in a term infant a red flag for PCD? Neonatal respiratory distress occurs in more than 80% of patients with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) and typically presents within the first 1-2 days of life [7]. In PCD, this distress is caused by impaired mucociliary clearance, leading to mucus impaction, atelectasis, and lobar collapse [7]. It is a significant indicator, especially in term infants without other risk factors (like surfactant deficiency common in prematurity) and when symptoms have a somewhat later onset, beginning 12-24 hours after birth [7]. Distinguishing it from other causes like transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN) is crucial, as PCD is a chronic condition requiring long-term management.

2. What constitutes "chronic daily symptoms" in the context of PCD? The ATS clinical criteria emphasize early-onset, year-round symptoms that are present on a daily basis [7]. The core chronic daily symptoms of PCD are:

- A daily wet cough that is productive [7].

- Daily nasal congestion that begins early in life and persists year-round [7]. These symptoms are a direct result of stagnant purulent mucus in the respiratory system due to dysfunctional motile cilia [7].

3. How can we improve PCD detection in infants without laterality defects like situs inversus? Approximately half of PCD patients have situs inversus totalis, but a significant proportion do not [7]. Relying solely on the presence of situs inversus for suspicion of PCD leads to underdiagnosis. Key strategies include:

- Proactive Investigation: A PCD work-up should be initiated in any neonate with unexplained respiratory distress, persistent oxygen requirement, or consistent radiographic findings (like lobar atelectasis), even in the absence of laterality defects [7].

- Targeted Laterality Screening: Chest radiography (CXR) alone can miss situs ambiguus (SA). One study showed that using CXR with add-on targeted investigations (e.g., echocardiogram, abdominal ultrasound) significantly increased the detection of SA from 8% to 24% in a PCD cohort [8]. These defects can involve the cardiovascular system, intestines, or spleen [8].

- Genetic Testing: As over 45 genes are associated with PCD, genetic testing can confirm a diagnosis, especially in cases with normal ciliary ultrastructure on electron microscopy [7].

4. What is the typical diagnostic delay for PCD, and why does it happen? The diagnosis of PCD is often delayed to a mean age of 4.4–6 years [7]. This delay is attributed to:

- The transient nature of initial neonatal respiratory distress symptoms [7].

- Overlapping symptoms with more common respiratory diseases like cystic fibrosis, asthma, and protracted bacterial bronchitis [7].

- A low index of suspicion among clinicians, particularly if the classic sign of situs inversus is absent [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Enhancing PCD Detection Without Overt Laterality Defects

| Challenge | Solution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Atypical or Subtle Laterality | Employ targeted investigations beyond CXR [8]. | Order echocardiogram for heart defects, abdominal ultrasound for spleen/liver position, and consider splenic function tests [8]. |

| Overlap with Common Illnesses | Strictly apply ATS clinical criteria for chronic daily symptoms [7]. | Differentiate via the year-round, daily nature of wet cough and nasal congestion from infancy, unrelated to seasonal allergies or discrete infections [7]. |

| Non-Diagnostic Initial Tests | Utilize a multi-test diagnostic panel [7]. | Combine nasal nitric oxide (nNO) testing, genetic testing, high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), as no single test is 100% sensitive [7]. |

| Normal Ciliary Ultrastructure | Proceed with genetic testing for PCD [7]. | Approximately one-third of PCD-causing gene mutations do not result in obvious ultrastructural defects visible on TEM [7]. |

Quantitative Data on PCD Clinical Presentation

Table 1: Frequency of Key Clinical Features in PCD This table summarizes the prevalence of major symptoms to aid in clinical recognition and differential diagnosis [7].

| Clinical Feature | Prevalence in PCD |

|---|---|

| Neonatal Respiratory Distress | >80% |

| Year-Round Daily Wet Cough | Nearly 100% |

| Year-Round Daily Nasal Congestion | ~80% |

| Situs Inversus Totalis | ~50% |

| Situs Ambiguus (Heterotaxy) | ~12% |

| Chronic Otitis Media | Very Common |

| Male Infertility | Nearly 100% |

Table 2: Spectrum of Laterality Defects Identified with Targeted Imaging This data illustrates the improved detection of situs ambiguus (SA) when CXR is supplemented with other imaging modalities in 159 PCD patients [8].

| Situs Classification | CXR Alone | CXR + Targeted Investigations |

|---|---|---|

| Situs Solitus (SS) | 55% | 47% |

| Situs Inversus Totalis (SIT) | 37% | 29% |

| Situs Ambiguus (SA) | 8% | 24% |

Experimental Protocols for PCD Research

Protocol 1: Validating a Multi-Modal Diagnostic Workflow for Infants with Unexplained Respiratory Distress

- Patient Cohort: Recruit term neonates (>37 weeks gestation) presenting with respiratory distress of unknown etiology, particularly with onset after 12 hours of life and/or lobar atelectasis on chest imaging [7].

- Initial Screening:

- First-Line PCD Testing: Measure nasal nitric oxide (nNO); low nNO is a strong indicator of PCD [7].

- Confirmatory Testing:

- Genetic Analysis: Conduct next-generation sequencing using a targeted PCD gene panel (over 45 known genes) [7].

- Ciliary Functional and Structural Studies: Arrange for nasal brush biopsy to be analyzed by high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at a specialist center [7].

- Data Correlation: Correlate genetic findings with clinical phenotype and ciliary function/structure results to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Protocol 2: Systematic Characterization of Laterality Defects in a PCD Population

- Study Population: Enroll patients with a confirmed or clinical diagnosis of PCD [8].

- Standardized Imaging:

- Chest Radiograph (CXR): Overread by a pediatric radiologist to assign initial situs (Solitus, Inversus, Ambiguus) [8].

- Echocardiogram: To identify congenital heart disease and vascular arrangement anomalies [8].

- Abdominal Ultrasound: To determine the position and morphology of the liver, spleen (e.g., polysplenia, asplenia), and stomach [8].

- Supplementary Investigations (as clinically indicated):

- Final Situs Classification: Compare the initial CXR classification with the final classification derived from the full suite of targeted investigations [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for PCD Diagnostic Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| PCD Gene Panel (NGS) | Identifies pathogenic variants in over 45 known PCD-associated genes. Crucial for diagnosing patients with normal TEM or atypical presentations [7]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) | Visualizes and quantifies ciliary beat frequency and pattern. Can detect functional abnormalities even when ultrastructure appears normal [7]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Assesses ciliary ultrastructure for classic defects (e.g., absent outer/inner dynein arms, microtubular disorganization) [7]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Device | Measures nNO levels, which are characteristically very low in most PCD patients, serving as a useful screening tool [7]. |

| Light Dosimeter | While used in EPP research in the search results, a analogous tool for quantifying ambient environmental exposures relevant to PCD symptoms is not standard but represents an area for methodological development. |

Visualizing the Diagnostic Pathway and Research Framework

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing PCD, with a specific focus on identifying cases without classic laterality defects.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic pathway for PCD, emphasizing key decision points.

This diagram illustrates the core research paradigm for improving PCD diagnosis, focusing on the critical role of neonatal respiratory distress and the challenge of cases without laterality defects.

Diagram 2: Research framework for enhancing PCD detection.

Diagnostic Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: A patient presents with a chronic wet cough and bronchiectasis. How can I differentiate between Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), Cystic Fibrosis (CF), and Asthma in the absence of laterality defects?

A1: The absence of laterality defects, such as situs inversus, is a common diagnostic challenge, as this presentation occurs in approximately 50% of PCD cases [9]. Focus on the nature of symptoms, underlying pathophysiology, and specific diagnostic testing.

- Symptom Quality: A daily, year-round wet/productive cough that begins in the neonatal period is a hallmark of PCD and CF, whereas asthma typically features a dry, episodic cough that may be triggered by allergens, exercise, or viruses [9].

- Neonatal History: Unexplained respiratory distress in a full-term neonate is a key indicator for PCD, present in 80-90% of cases [9]. CF may also present in infancy, but often with meconium ileus or failure to thrive.

- Inflammatory Drivers: PCD and CF are primarily associated with neutrophilic inflammation due to impaired mucociliary clearance and chronic bacterial infection [10] [9]. Asthma, particularly the allergic (Th2-high) endotype, is characterized by eosinophilic inflammation [9] [11].

- Diagnostic Gold Standards:

- PCD: Genetic testing identifying biallelic pathogenic variants in a PCD-associated gene (e.g., DNAH5, DNAI1) or transmission electron microscopy revealing specific ciliary ultrastructural defects (e.g., absent outer dynein arms) [9].

- CF: An abnormal quantitative pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat chloride test (≥60 mmol/L) and/or genetic testing confirming biallelic pathogenic CFTR variants [12] [13].

- Asthma: Demonstration of variable expiratory airflow limitation via spirometry (e.g., significant bronchodilator reversibility or positive bronchoprovocation test) [9].

Q2: What are the key pathophysiological differences in mucociliary function between PCD and CF?

A2: While both diseases result in impaired mucociliary clearance, the fundamental mechanisms differ, as summarized below [9] [13].

Table 1: Pathophysiological Comparison of PCD and CF

| Feature | Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Defect | Dysfunctional motile cilia structure/function | Defective ion transport due to CFTR protein malfunction |

| Ciliary Ultrastructure | Often abnormal (e.g., absent dynein arms, disrupted microtubules) | Typically normal |

| Mucus Composition | Primarily normal | Abnormally thick, dehydrated mucus due to defective chloride secretion and excess sodium absorption |

| Main Airway Consequence | Stagnant mucus due to ineffective ciliary beating | Physical obstruction by thick, adherent mucus plaques |

The following diagram illustrates the core pathophysiological pathways in PCD, CF, and Asthma.

Q3: What specific inflammatory biomarkers can help distinguish between these conditions?

A3: Biomarker profiles can provide critical evidence for differentiation, especially when clinical features overlap.

Table 2: Key Biomarkers for Differentiating PCD, CF, and Asthma

| Condition | Primary Inflammatory Biomarker | Other Relevant Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| PCD | Persistent Neutrophilia in sputum [9] | Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) is characteristically very low [9] |

| CF | Persistent Neutrophilia in sputum, often with chronic bacterial infection (e.g., P. aeruginosa, S. aureus) [10] | Elevated CRP during exacerbations; potential for allergic biomarkers if ABPA is present [12] |

| Asthma (Th2-high) | Elevated blood/sputum eosinophils [11] | Elevated Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO); serum IgE (especially in allergic asthma) [11] |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Genomic Characterization of Respiratory Pathogens

This protocol is adapted from a study characterizing bacterial isolates from pediatric CF patients, a methodology applicable to PCD research for understanding chronic infection profiles [10].

Objective: To identify and characterize bacterial sequence types (STs) and phenotypic adaptations, such as Small Colony Variants (SCVs), from respiratory specimens.

Materials & Reagents:

- Selective Culture Media: Mannitol-salt agar (Staphylococcus), Cetrimide agar (Pseudomonas), Endo medium (Gram-negative enterics), Columbia blood agar (non-selective growth and hemolysis).

- API 20E System (bioMérieux) or similar for biochemical identification.

- DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit (Qiagen) for genomic DNA extraction.

- KAPA Hyperplus Library Prep Kit (Roche) for WGS library construction.

- MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (Illumina) for sequencing.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection & Culture: Inoculate respiratory specimens (sputum/BAL) onto selective and non-selective agars. Incubate for 24-72 hours at 37°C, with extended incubation at room temperature for up to 5 days to isolate slow-growing SCVs [10].

- Phenotypic Characterization: Identify SCVs by their characteristic small colony size (<1 mm), lack of pigment, absence of hemolysis, and "fried-egg" morphology. Perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) following EUCAST guidelines [10].

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS):

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA.

- Prepare sequencing libraries using the KAPA Hyperplus kit.

- Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2x300 bp chemistry).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Use tools like

bbdukfor quality trimming and adapter removal. - Perform de novo assembly with

shovill. - Determine Sequence Types (STs) using

mlstfor Multi-Locus Sequence Typing. - Identify antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes with

AMRFinderPlusandARIBA[10].

- Use tools like

Protocol for Symptom Phenotyping Using Machine Learning

This protocol uses k-means clustering to identify clinically meaningful symptom phenotypes, a technique demonstrated in CF and applicable to PCD for stratifying patient populations [14] [15].

Objective: To discover distinct symptom clustering patterns in patients at the onset of a pulmonary exacerbation.

Materials & Reagents:

- Clinical Data: Prospectively collected patient symptom data using a validated instrument (e.g., the CF Respiratory Symptom Diary - Chronic Respiratory Infection Symptom Score, CFRSD-CRISS).

- Software: R Studio with packages

NbClustand standard statistical libraries.

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Collect daily symptom scores (e.g., difficulty breathing, cough, sputum, wheezing) on a 0-4 scale for the first 21 days of an exacerbation.

- Clusterability Assessment:

- K-means Clustering: Apply the k-means algorithm to the Day 1 symptom data to assign patients to distinct clusters (e.g., Low-Symptom vs. High-Symptom phenotypes) [14] [15].

- Validation & Association: Use linear regression and multi-level growth models to test associations between cluster membership and clinical outcomes like hospitalization length and symptom resolution trajectory [14].

The workflow for this data-driven phenotyping approach is outlined below.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCD and Chronic Infection Research

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application in PCD/CF Research |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Culture Media (e.g., Cetrimide agar) | Selective isolation of specific pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa). | Profiling chronic respiratory infections and detecting polymicrobial cultures [10]. |

| API 20E System (bioMérieux) | Biochemical identification of Gram-negative bacteria. | Standardized phenotypic identification of Enterobacterales from patient samples [10]. |

| DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality genomic DNA extraction from bacterial cultures. | Preparation of DNA for Whole Genome Sequencing to determine STs and AMR genes [10]. |

| KAPA Hyperplus Library Prep Kit (Roche) | Preparation of Illumina-compatible sequencing libraries from DNA. | Essential step for WGS-based genotyping and phylogenetic analysis [10]. |

| CFRSD-CRISS Diary | Validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument. | Quantifying respiratory symptom severity for machine learning-based phenotyping studies [14] [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) particularly challenging to diagnose in patients with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)? PCD diagnosis is often delayed or missed in CHD patients because the classic clinical hallmark, situs inversus (mirror-image organ arrangement), is not always present. In patients with CHD and heterotaxy (abnormal organ arrangement), respiratory symptoms can be incorrectly attributed solely to the cardiac defect or post-surgical complications, diverting attention from underlying ciliary dysfunction [16]. Furthermore, neonatal respiratory distress, a key symptom of PCD, is also common in neonates with complex CHD, creating a diagnostic overlap [5].

Q2: What are the key clinical red flags that should trigger PCD investigation in a patient with CHD? Clinicians should suspect PCD in CHD patients presenting with [16] [5]:

- Early-onset, recurrent respiratory issues: Including neonatal respiratory distress, recurrent otitis media, rhinosinusitis, and persistent wet cough.

- Laterality defects: Especially heterotaxy (which can include complex CHD and polysplenia or asplenia), not just classic situs inversus.

- Unexplained postoperative respiratory complications: Such as recurrent atelectasis that is difficult to resolve, particularly in a patient with known laterality defects.

Q3: What definitive diagnostic tests are recommended for confirming PCD in this patient population? A combination of tests is often necessary for a definitive diagnosis [16] [5]:

- Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) measurement: Typically low in PCD, useful as an initial screening tool.

- Genetic Testing: Identifying biallelic pathogenic variants in a known PCD-associated gene provides a definitive diagnosis.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Analysis of ciliary ultrastructure from a nasal or bronchial biopsy to identify specific defects (e.g., absent outer/inner dynein arms).

Q4: How can ciliary dysfunction impact the surgical and long-term outcomes for CHD patients? Evidence suggests that ciliary abnormalities may increase the risk of postoperative mortality and respiratory complications in patients with CHD [16]. Impaired mucociliary clearance leads to recurrent infections and atelectasis, which can complicate post-surgical recovery and contribute to progressive chronic heart failure [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Navigating PCD Diagnosis in Complex CHD

This guide addresses common diagnostic challenges and offers evidence-based solutions for clinicians and researchers.

| Challenge | Symptom Overlap | Recommended Action & Experimental Protocol | Key Reagents & Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attributing respiratory symptoms solely to cardiac status | Atelectasis, wheezing, respiratory distress. | Action: Systematically investigate ciliary function in CHD patients with heterotaxy or recurrent respiratory issues, regardless of the primary cardiac diagnosis [16].Protocol: Implement a standardized screening protocol using nNO measurement followed by genetic testing or TEM confirmation [5]. | - nNO analyzer- PCD genetic testing panels (e.g., next-generation sequencing panels for >50 known PCD-related genes)- TEM fixatives (e.g., glutaraldehyde) |

| Distinguishing PCD from other ciliopathies with overlapping features | Heterotaxy, CHD, respiratory symptoms, developmental delay. | Action: Consider Joubert Syndrome and Related Disorders (JSRD), which affects primary cilia, and can co-present with motile cilia defects [16].Protocol: Perform brain MRI to identify the "molar tooth sign" characteristic of JSRD. For motile cilia, proceed with TEM and genetic testing for genes like OFD1 linked to both conditions [16]. | - MRI machine- Genetic analysis for OFD1 mutations- TEM |

| Managing poor postoperative respiratory outcomes | Recurrent atelectasis, difficult extubation, chronic pulmonary infections. | Action: In patients with confirmed or suspected ciliary dysfunction, employ aggressive perioperative pulmonary hygiene [16].Protocol: Implement rigorous chest physiotherapy, frequent suctioning, and consider early bronchoscopy to clear secretions. Maintain a high index of suspicion for PCD in this context [16]. | - Chest physiotherapy devices- Bronchoscope- Microbiological culture media for pathogen identification |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting research into the mechanisms linking PCD and CHD.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| Anti-DNAH5 / DNAI1 Antibodies | Immunofluorescence staining to detect the presence and localization of key dynein arm proteins in ciliated cell cultures. Absence indicates specific ultrastructural defects [5]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) | To capture and analyze the ciliary beat pattern and frequency from fresh patient-derived ciliated epithelial cells. Dyskinetic or absent beating is diagnostic for PCD [5]. |

| PCD-Specific Genetic Panels (NGS) | Next-generation sequencing panels targeting all known PCD-causing genes to identify pathogenic variants and establish a genetic diagnosis, especially useful when TEM is inconclusive [5]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Visualization of the internal 9+2 microtubule structure of cilia to identify hallmark defects such as absent outer/inner dynein arms, which are common in PCD [16] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Diagnostics

Protocol 1: Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for Ciliary Ultrastructure

- Sample Collection: Obtain nasal epithelial brush biopsies or bronchial samples.

- Fixation: Immediately place samples in primary fixative (e.g., 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer) for a minimum of 24 hours at 4°C.

- Processing: Post-fix in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrate through a graded ethanol series, and embed in resin.

- Sectioning & Staining: Cut ultrathin sections (60-90 nm) and stain with uranyl acetate and lead citrate.

- Imaging & Analysis: Examine sections under TEM. Score for specific defects (e.g., outer dynein arm absence) by examining multiple cross-sections [16] [5].

Protocol 2: Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement as a Screening Tool

- Patient Preparation: The patient should be free from acute respiratory infections and not have eaten recently.

- Technique: Using a chemiluminescence analyzer, measure nNO while the patient exhales against resistance at a constant flow rate from a tidal breath held for 10-15 seconds (velum closure technique).

- Interpretation: nNO values persistently below a validated cutoff (e.g., 77 nL/min in children) are highly suggestive of PCD and warrant further investigation with TEM or genetic testing [5].

Diagnostic Pathways and Research Workflows

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Pathway for PCD in Patients with CHD. This flowchart outlines the sequential steps for investigating PCD in a patient with congenital heart disease, integrating screening and confirmatory tests. nNO: nasal Nitric Oxide; TEM: Transmission Electron Microscopy; JSRD: Joubert Syndrome and Related Disorders.

The Diagnostic Arsenal: From Standardized Screening to Cutting-Edge Confirmation

Nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement has emerged as a critical, non-invasive screening tool in the diagnostic pathway for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), a rare genetic disorder characterized by dysfunctional motile cilia. In the context of enhancing PCD detection, particularly for patients without classic laterality defects, nNO screening provides a valuable first-line investigation. The consistently low nNO levels observed in most PCD patients—approximately one-tenth of normal values—offer a reliable biochemical marker that can prompt further specialized testing, even when other clinical signs like situs inversus are absent [17]. This technical support center outlines standardized methodologies, troubleshooting guides, and analytical protocols to support researchers and clinicians in implementing robust nNO screening programs within their PCD diagnostic workflows.

Quantitative nNO Data in PCD and Respiratory Diseases

nNO measurement provides a key discriminatory value between PCD patients, healthy individuals, and those with other respiratory conditions. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from meta-analyses and clinical studies.

Table 1: Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Levels Across Different Populations

| Population / Condition | Mean nNO Level (nL/min) | Standard Deviation | Sample Size (n) | Recommended Cut-off Value (nL/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls [18] | 265.0 | ± 118.9 | 338 | Not Applicable |

| PCD Patients [18] | 19.4 | ± 18.6 | 478 | < 77-100 [17] |

| Cystic Fibrosis Patients [18] | 133.5* | Not Specified | 415 | Not Applicable |

| PCD Patients (Tidal Breathing) [18] | Low (reduced discriminatory value) | Not Specified | Multiple Studies | Varies by technique |

| Symptomatic, Non-PCD (Winter) [19] | 123 (Median) | Not Specified | 434 | < 66 [19] |

| Symptomatic, Non-PCD (Summer) [19] | 167 (Median) | Not Specified | 434 | < 66 [19] |

*Calculated weighted mean difference for PCD vs. cystic fibrosis was 114.1 nL/min [18].

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accurate nNO measurement requires strict adherence to standardized protocols. The following section details key experimental procedures.

Protocol 1: nNO Measurement with Breath-Hold Maneuver

The breath-hold technique with velum closure is the gold-standard method for cooperative patients, typically those over 5 years of age [20] [17].

Primary Workflow Diagram

Materials and Equipment:

- Chemiluminescence or electrochemical NO analyzer [20]

- Nasal catheter or olive with airtight foam sleeve

- Calibration gases (NO standard, zero air)

- Disposable mouthpieces (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Patient Preparation: Ensure the patient is seated comfortably. Exclude individuals with acute upper respiratory infections (within 2-4 weeks) or active nosebleeds, as these can cause falsely low nNO [20].

- Equipment Calibration: Calibrate the NO analyzer according to the manufacturer's instructions using certified calibration gases before the first test of the day.

- Maneuver Execution: Insert the nasal olive into one nostril, ensuring an airtight seal. Instruct the patient to exhale fully, then inhale deeply to total lung capacity through the mouth. The patient must then hold their breath while keeping the velum (soft palate) closed to prevent contamination from lung air, which has lower NO concentrations [18] [17].

- Sampling: Aspirate air from the nasal cavity at a constant flow rate. Common flow rates are between 0.3 to 5 mL/s, though 3 mL/s is frequently used. The nNO output (nL/min) should be recorded once a stable plateau is observed [18] [20].

- Repeat: Perform at least two technically acceptable measurements per nostril. The results are typically reported as the mean value.

Protocol 2: nNO Measurement During Tidal Breathing

For young children (<5 years) or individuals unable to perform the breath-hold maneuver, tidal breathing is an acceptable alternative, though with reduced discriminatory power [18] [20].

Procedure:

- Setup: Position the patient and insert the nasal olive as described in Protocol 1.

- Sampling: During quiet, tidal breathing through the mouth, aspirate nasal air at a controlled flow rate. The patient should breathe normally with the mouth slightly open, which helps close the velum passively.

- Recording: Record the nNO output once a stable reading is achieved. Note that values obtained via tidal breathing are generally lower than those from breath-hold and have a different, typically lower, diagnostic cut-off point [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for nNO Measurement

| Item | Function/Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence Analyzer | Gold-standard device; measures NO via reaction with ozone producing light [20] [21]. | Highly accurate and reliable for real-time measurement; less portable and more expensive [20]. |

| Electrochemical Analyzer | Portable device; measures NO via electrical current produced in a chemical reaction [20]. | Increasingly used; more portable and cost-effective; performance validation is crucial [20]. |

| Nasal Olives/Probes | Creates an airtight seal in the nostril to prevent ambient air dilution. | Disposable or reusable olives with different sizes are needed for various patient ages. |

| Calibration Gases | Essential for daily calibration to ensure measurement accuracy. | Requires a known concentration of NO in an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) and a zero gas [21]. |

| Nose Clip | May be used during tidal breathing to ensure nasal-only breathing. | Simple physical barrier. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common technical and interpretative challenges encountered during nNO testing.

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of falsely low nNO readings, and how can they be mitigated?

Falsely low nNO is a significant concern as it can lead to unnecessary further testing. The main causes and solutions are:

- Acute Viral Infections: Upper respiratory infections can transiently lower nNO. Solution: Postpone testing until at least 2-4 weeks after full symptom resolution [20].

- Seasonal Variability: nNO levels are statistically significantly lower in winter compared to summer in subjects without PCD. Solution: If an unexpectedly low nNO is found in winter in a symptomatic patient, consider repeating the test in the summer before proceeding to invasive diagnostics [19].

- Technical Errors: Inadequate velum closure during breath-hold contaminates the sample with low-NO lung air. Solution: Properly train the patient on the maneuver. Use visual or verbal cues to ensure breath-holding with a closed glottis.

- Nasal Polyps or Obstruction: Significant blockage can impede airflow. Solution: Perform a brief visual inspection of the nares before testing.

FAQ 2: How do we account for nNO variability in children versus adults?

Cooperation is the primary differentiator.

- Children >5 years: Can often perform the breath-hold maneuver. Use the same protocol as for adults for the most discriminatory result [17].

- Young Children (<5 years) / Uncooperative: The tidal breathing method must be employed. Critical Note: The reference ranges and diagnostic cut-offs for tidal breathing are distinct from and lower than those for the breath-hold technique. Laboratories must establish or use validated reference values for their specific tidal breathing protocol [18] [20].

FAQ 3: Our research involves PCD patients without laterality defects. Is nNO still a reliable marker?

Yes. Low nNO is a consequence of the underlying ciliary dysfunction in the nasal epithelium, which is independent of organ placement. The genetic defects causing PCD affect motile cilia throughout the body. Therefore, nNO is consistently low in most forms of PCD, regardless of whether the patient has situs solitus (normal arrangement), situs inversus, or situs ambiguus [8] [17]. This makes it a powerful tool for identifying PCD in the entire patient spectrum.

FAQ 4: When should we use a portable electrochemical analyzer versus a stationary chemiluminescence analyzer?

- Chemiluminescence Analyzers: are ideal for a central lab or clinic setting. They are considered the most accurate and reliable for real-time measurement and have been validated in multicentre studies. Use these for definitive diagnostic testing [20].

- Electrochemical Analyzers: are best for field studies, satellite clinics, or situations where portability is paramount. They are more affordable but require rigorous validation against chemiluminescence standards to ensure data reliability [18] [20].

Advanced Analytical Considerations

Impact of Seasonal Variability on Research Protocols

The observed seasonal fluctuation in nNO has direct implications for study design and data interpretation.

Seasonal Impact Diagram

Research Recommendation: For longitudinal studies or when screening symptomatic cohorts, the season of testing should be recorded as a key variable. A low nNO measurement obtained in winter should be interpreted with caution and, where possible, confirmed with a repeat test in the summer to minimize false positives [19].

Integration with the Broader PCD Diagnostic Pathway

nNO is a screening tool, not a standalone diagnostic. The following workflow integrates nNO into a comprehensive diagnostic strategy for PCD, particularly in cases without laterality defects.

Comprehensive Diagnostic Pathway

This integrated approach ensures that nNO's high sensitivity is leveraged to identify at-risk individuals, who then undergo definitive testing, thus streamlining the diagnostic journey and reducing delays.

### Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: Our genetic testing results show a high number of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS). Is this common, and what factors contribute to it?

A: Yes, a high VUS rate is a well-documented challenge in modern genetic testing. The frequency of VUS findings is not uniform and can vary significantly based on the clinical context and the patient population being tested [22].

Key factors influencing VUS rates include:

- Patient Ancestry: Individuals from populations underrepresented in genomic databases (e.g., Middle Eastern, Asian, Hispanic) have a higher probability of receiving a VUS result [23] [22]. One study found a 3-fold variation in VUS rates based on self-reported race [22].

- Test Indication: The primary reason for genetic testing can lead to over a 14-fold difference in the number of VUS reported relative to pathogenic variants [22].

- Gene Panels: The evolution from single-gene testing (e.g., BRCA1/2 only) to large multigene panels has broadened the scope of testing, inevitably increasing the detection of rare variants with limited available evidence [23].

Q2: What are the practical steps for reclassifying a VUS?

A: Reclassification is a systematic process that relies on gathering additional evidence. The following methodology, adapted from published studies, provides a robust framework [23]:

- Evidence Review: Compile population frequency data from databases like gnomAD. A very high allele frequency is inconsistent with a highly penetrant disease.

- Computational Prediction: Utilize in-silico predictors (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2) to assess the variant's potential impact on protein function.

- Segregation Analysis: Test family members to see if the variant co-segregates with the disease phenotype.

- Functional Studies: Generate experimental data on the variant's effect, though this is often not feasible in a clinical setting.

- Literature and Database Mining: Search for new peer-reviewed evidence or updated classifications in ClinVar.

- Expert Consensus: Apply established guidelines, such as the ACMG/AMP 2015 criteria or the ClinGen ENIGMA methodology for specific genes, to assign a new pathogenicity class [23].

Q3: We are experiencing issues with SNP genotyping assays, such as failed amplification or multiple clusters in the data. What could be the cause?

A: Several technical issues can lead to these problems [24]:

- Failed Amplification: This can result from inaccurately quantitated DNA, degraded DNA, inhibitors in the sample, or an error in the reaction setup. If you are designing a custom assay, an incorrect input sequence can also cause failure.

- Multiple or Trailing Clusters: This is often due to a hidden SNP under the probe or primer binding site. You can search dbSNP for other polymorphisms in the region. Alternatively, the region might be within a copy number variation. Trailing clusters can also be caused by significant variation in the quality or concentration of the gDNA samples across your study [24].

Q4: How can we ensure our genetic tests are discoverable and transparent to the clinical and research community?

A: The NIH's Genetic Testing Registry (GTR) is a centralized, publicly available database for this purpose [25]. Test providers, including both U.S. and international clinical and research laboratories, can voluntarily submit detailed information about their tests. This includes the test's purpose, methodology, analytical validity, and evidence of clinical validity. Registering your test in the GTR provides a unique accession number, enhancing transparency and allowing for uniform referencing in publications and health records [25].

Q5: A significant number of our patients with laterality defects are not being evaluated for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), despite meeting clinical criteria. How can we improve this?

A: This is a recognized issue. A recent study found that while 96% of patients meeting all four PCD criteria were referred to a pulmonologist, only 41% of those meeting the minimum of two criteria were referred [1]. Improving detection requires:

- Education: Increase awareness among pediatricians and specialists about the PCD clinical criteria: laterality defect, chronic daily cough, year-round nasal congestion starting in infancy, and unexplained neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (NRDS) in a term infant [1] [26].

- Lower Referral Threshold: Have a heightened suspicion for PCD even when other diagnoses, like congenital heart disease (which is common in patients with laterality defects), are present and could explain respiratory symptoms [1].

- Utilize Available Diagnostics: Increase the use of screening tools like nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement and commercially available genetic panels, which have made definitive diagnosis more accessible outside of highly specialized centers [26].

Q6: How significant is the problem of outdated variant classifications in clinical care?

A: This is a critical systems-level challenge. Research using an EHR-linked database found that at least 1.6% of variant classifications used in the EHR for clinical care are outdated based on current ClinVar data [22]. The same study identified 26 specific instances where a testing lab had updated a variant's classification in ClinVar, but this reclassification was never communicated to the patient, meaning clinical decisions were being made using obsolete information [22]. This highlights a major bottleneck in the dissemination of knowledge between databases, testing labs, and providers.

### Key Quantitative Data on VUS and PCD Detection

Table 1: VUS Reclassification Outcomes in a Middle Eastern HBOC Cohort [23]

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total VUS detected before reclassification | 160 |

| VUS successfully reclassified | 52 (32.5%) |

| VUS upgraded to Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic | 4 (2.5% of total VUS) |

| Median number of total VUS per patient | 4 |

| Non-informative (VUS) result rate in cohort | 40% |

Table 2: Referral and Evaluation Patterns for PCD in Patients with Laterality Defects [1]

| Patient Group | Referral to Pulmonary | Evaluation for PCD |

|---|---|---|

| All patients meeting ≥2 PCD criteria (n=79) | 41% | 16% |

| Patients meeting all 4 PCD criteria (n=27) | 96% | 93% |

| Patients with only 1 criterion (laterality defect, n=189) | Not reported | Not reported |

### Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Variant Reclassification Workflow

This protocol is adapted from the retrospective reclassification study performed on a Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) cohort [23].

- Variant Collection: Compile all germline variants initially classified as VUS (Class 3) from clinical genetic test reports.

- Independent Review: Two independent assessors (e.g., a certified laboratory geneticist and an experienced laboratory scientist) review each variant.

- Evidence Gathering: For each variant, reviewers systematically gather and evaluate the following:

- Population Frequency: Query the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) for allele frequency.

- In-silico Analysis: Run the variant through computational predictors like SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP).

- Literature and Database Review: Search for functional, clinical, or segregation data in published literature and the ClinVar database.

- Apply Classification Guidelines: Score the assembled evidence using the latest ACMG/AMP 2015 criteria. For genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2, the more specific ClinGen ENIGMA methodology should be applied.

- Consensus Meeting: Reviewers meet to discuss their independent classifications, resolve any discrepancies, and assign a final pathogenicity class (1-5) for each variant.

Protocol 2: Assessing PCD Referral Patterns

This protocol is based on a retrospective chart review study investigating PCD detection [1].

- Cohort Identification: Use the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system to identify all pediatric patients (e.g., ≤18 years) over a defined period (e.g., 12 years) with diagnoses indicating a laterality defect (e.g., heterotaxy, dextrocardia, situs inversus).

- Apply Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria:

- Inclusion: Patients with at least one laterality defect.

- Exclusion: Patients without laterality defects, those with unavailable symptom data, and those deceased at or before 2 years of age.

- Data Abstraction: For each included patient, manually review the chart to record:

- Presence or absence of the four PCD clinical criteria (laterality defect, chronic daily cough, year-round nasal congestion starting in infancy, unexplained NRDS requiring >24h of oxygen/positive pressure).

- Documentation of referral to pediatric pulmonology or genetics.

- Documentation of any evaluation for PCD (e.g., nNO, genetic testing, TEM).

- Demographics (sex, race, ethnicity, insurance type).

- Statistical Analysis: Analyze data to determine referral and evaluation rates. Use Chi-square tests and logistic regression to examine the impact of the number of PCD criteria and patient demographics on referral rates.

### Visual Workflows

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Genetic Testing and Variant Interpretation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) | Public repository of population allele frequencies critical for assessing if a variant is too common to be causative for a rare disease [23]. |

| ClinVar | Public archive of reports on the relationships between human variants and phenotypes, with supporting evidence; essential for comparing your variant classification with the community [23] [22]. |

| ACMG/AMP Classification Guidelines | The standardized framework for interpreting sequence variants, providing criteria to classify variants as Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic, VUS, Likely Benign, or Benign [23]. |

| Genetic Testing Registry (GTR) | A centralized NIH database for test providers to voluntarily submit information about their genetic tests, improving transparency and discoverability for clinicians and researchers [25]. |

| Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | A powerful tool that determines the effect of your variants (e.g., missense, synonymous) on genes, transcripts, and protein sequence, as well as regulatory regions [23]. |

| TaqMan Genotyper Software | An example of specialized software for analyzing and automating calls in SNP genotyping experiments, which can have improved clustering algorithms over standard instrument software [24]. |

The Evolving Role of Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) in a Genetic-First Diagnostic World

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare genetic disorder affecting approximately 1 in 20,000 individuals, characterized by dysfunction of motile cilia leading to chronic respiratory infections, bronchiectasis, and laterality defects in approximately 50% of cases [27]. In the current diagnostic landscape, genetic testing has emerged as a powerful first-line tool, with approximately 50 known causative genes identified [27]. Despite this genetic-focused approach, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) maintains a crucial role in the diagnostic algorithm, particularly for confirming diagnosis in cases of variant of uncertain significance or novel genetic findings.

This technical support center addresses the practical challenges researchers face when integrating TEM with genetic testing, providing troubleshooting guidance to enhance diagnostic accuracy. The continued evolution of TEM protocols and international standardization efforts ensures its place as an indispensable component of comprehensive PCD diagnosis, enabling researchers to confirm ultrastructural defects that correlate with genetic variants and clinical presentations.

Diagnostic Frameworks: Integrating TEM with Genetic Testing

Current Diagnostic Criteria and Classifications

Modern PCD diagnosis utilizes a multifaceted approach, with TEM providing critical evidence for definitive diagnosis. According to recent guidelines, a definitive PCD diagnosis requires exclusion of cystic fibrosis and primary immunodeficiency, at least one characteristic clinical feature, and a positive result from specific confirmatory tests [27].

Table 1: Diagnostic Categories for PCD Confirmation

| Diagnostic Category | Clinical Features Required | Laboratory Evidence Required | Genetic Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite PCD | At least one of six defined clinical features | • Class 1 defect on TEM OR • Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in PCD-related gene OR • Impairment of ciliary motility repairable by gene correction in iPS cells | Genetic testing can confirm but is not always required if TEM shows definitive defect |

| Probable PCD | Clinical features suggestive of PCD | Class 2 defect on TEM OR borderline/low nNO with supportive clinical picture | May have variants of uncertain significance |

| Possible PCD | Incomplete or atypical clinical presentation | Equivocal or conflicting laboratory findings | May lack genetic confirmation |

The international BEAT PCD TEM Criteria provide standardized classification for ultrastructural defects, defining Class 1 defects as diagnostic for PCD and Class 2 defects as indicative of PCD when combined with other supporting evidence [28]. This classification system has been validated across 18 diagnostic centers in 14 countries, enabling consistent reporting and interpretation of TEM findings globally.

TEM Defect Classification in the Genetic Era

Table 2: TEM Ultrastructural Defects in PCD Diagnosis

| Defect Category | Specific Defects | Diagnostic Significance | Common Genetic Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Diagnostic) | • Outer dynein arm defects • Combined outer and inner dynein arm defects • Microtubular disorganization with central pair defects • Absent inner dynein arms with microtubular disorganization | Definitive for PCD | Strong correlation with multiple known PCD genes including DNAH5, DNAI1, CCDC39, CCDC40 |

| Class 2 (Supportive) | • Isolated inner dynein arm defects • Central apparatus defects • Miscellaneous defects including radial spoke defects | Require additional supportive evidence for diagnosis | Variable genetic associations, some genes not yet identified |

| Normal Ultrastructure | Normal ciliary axonemal structure | Does not exclude PCD (up to 30% of cases) | May indicate genetic defects affecting ciliary function without structural defects |

The integration of TEM with genetic testing creates a powerful diagnostic synergy. While genetic testing can identify pathogenic variants, TEM provides functional validation of the structural impact of these variants, particularly important for novel gene discoveries or variants of uncertain significance.

Technical Support Center: TEM Troubleshooting and Methodologies

Frequently Asked Questions: TEM in PCD Diagnosis

Q1: What constitutes an adequate ciliary sample for TEM analysis, and how can I avoid common sampling errors? A: An adequate diagnostic sample requires properly oriented ciliary cross-sections from at least 60-70 different cilia. Common issues include tangential sectioning (producing longitudinal views), excessive mucus contamination, and processing artifacts. To ensure proper orientation, look for the classic "9+2" microtubule arrangement in circular profiles. Samples with predominantly oblique or longitudinal sections should be considered inadequate for diagnosis and require re-biopsy [28].

Q2: How does the BEAT PCD TEM Criteria system distinguish between Class 1 and Class 2 defects? A: The internationally validated BEAT PCD TEM Criteria defines Class 1 defects as those with definitive diagnostic value, including outer dynein arm absence, combined outer and inner dynein arm defects, and specific microtubular disorganization patterns. Class 2 defects have more variable diagnostic significance and require correlation with other tests such as genetic analysis or nasal nitric oxide measurement. Isolated inner dynein arm defects fall into this category, as they can be more challenging to identify consistently and may have partial presentations [28].

Q3: What are the most common artifacts that can mimic PCD ultrastructural defects, and how can I distinguish them? A: Common artifacts include secondary ciliary dyskinesia from infection or inflammation, processing-induced microtubule disorganization, and oblique sectioning that creates false appearance of defects. Key distinguishing factors: primary ciliary defects affect virtually all cilia consistently, while secondary defects show patchy involvement and are often reversible with clinical improvement. Always correlate TEM findings with clinical presentation and consider repeat sampling after treating active infection [28].

Q4: In a genetic-first diagnostic approach, when is TEM analysis still indicated? A: TEM remains crucial in these scenarios: (1) when genetic testing identifies variants of uncertain significance; (2) when no pathogenic variants are identified despite strong clinical suspicion (covering the 20-30% of cases where genetic testing is negative); (3) for functional validation of novel gene variants; and (4) when establishing new PCD diagnostic programs and validating genetic testing panels [27] [28].

Q5: What technical factors most significantly impact TEM image quality for ciliary analysis? A: Critical factors include: proper fixation (fresh glutaraldehyde fixation within 2 hours of biopsy), avoidance of freezing artifacts, appropriate staining protocols, correction of contrast transfer function, and precise defocus determination. Sample preparation must maintain ciliary orientation and ultrastructural integrity throughout processing [29].

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide

Issue: Inconsistent Identification of Inner Dynein Arm Defects Solution: Implement high-contrast staining protocols and ensure optimal section thickness (70-90 nm). Use standardized imaging protocols with multiple independent reviewers. Consider that some genetic forms of PCD (e.g., CCDC39-related) show complete axonemal disorganization rather than isolated inner dynein arm defects [28].

Issue: Discrepancy Between Genetic Findings and TEM Ultrastructure Solution: This may occur in 10-15% of cases. Consider these possibilities: (1) genetic variants affecting ciliary function without structural defects (e.g., GAS8-related PCD); (2) technical limitations in TEM sensitivity; or (3) secondary ciliary modifications. Utilize complementary functional tests like high-speed videomicroscopy or ciliary waveform analysis [27].

Issue: Poor Sample Preservation Affecting Diagnostic Interpretation Solution: Optimize the biopsy-to-fixation time, using immediate immersion in glutaraldehyde-based fixatives. For difficult cases, consider protocol modifications from large-sample TEM studies that have addressed preservation challenges in centimeter-scale samples, including extended osmium tetroxide incubation with temperature control and modified washing steps to prevent microbreakages [30].

Research Reagent Solutions for TEM Analysis

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCD TEM Diagnostics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Fixatives | Glutaraldehyde (2.5-3%), Paraformaldehyde | Tissue preservation and ultrastructural maintenance | Critical for biopsy-to-fixation time (<2 hours); buffer with cacodylate or phosphate |

| Secondary Fixatives | Osmium tetroxide (1-2%) | Lipid membrane stabilization and electron density | Requires careful handling; temperature control vital for large samples [30] |

| Staining Agents | Uranyl acetate, Lead citrate | Heavy metal contrast enhancement for membrane visualization | Can be applied en bloc or section staining; protocols exist for large samples [30] |

| Embedding Media | Epon, Spurr's epoxy resin | Tissue support for ultrathin sectioning | Infiltration protocols must be adjusted for sample size; viscosity critical [30] |

| Specialty Reagents | Thiocarbohydrazide (TCH), Pyrogallol (Pg) | Enhanced conductive staining for large samples | Pyrogallol can replace TCH to reduce sample breakage in large specimens [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Integrated PCD Diagnostic Protocol

Figure 1: Contemporary PCD Diagnostic Workflow Integrating Genetic and TEM Approaches

Detailed TEM Sample Preparation Protocol

For optimal ciliary ultrastructure preservation, follow this standardized protocol derived from current best practices:

Sample Collection and Primary Fixation

- Obtain nasal brush biopsy or bronchial biopsy using appropriate clinical techniques

- Immediately immerse sample in cold (4°C) 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4)

- Fix for minimum 2 hours at 4°C, with gentle agitation if possible

- Wash 3× in cacodylate buffer (10 minutes each)

Secondary Fixation and Staining

- Post-fix in 1% osmium tetroxide in cacodylate buffer for 90 minutes at 4°C

- For larger tissue samples, extend osmium incubation to 3-6 days with temperature control to prevent peripheral ultrastructural disintegration [30]

- Rinse thoroughly with buffer (3×10 minutes)

- For en bloc staining, incubate with 1% uranyl acetate for 60 minutes

Dehydration and Embedding

- Dehydrate through graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 90%, 100% ×3), 10 minutes each step

- Transition through propylene oxide (2×10 minutes)

- Infiltrate with epoxy resin mixtures (1:2, 1:1, 2:1 resin:propylene oxide) for 2 hours each step

- For samples >2mm, add 95% resin in 5% acetone step to decrease viscosity and extend incubation times [30]

- Transfer to pure resin for overnight infiltration

- Embed in fresh resin and polymerize at 60°C for 48 hours

Sectioning and Imaging

- Prepare semi-thin sections (0.5-1μm) and stain with toluidine blue for orientation

- Cut ultrathin sections (70-90nm) using diamond knife

- Collect sections on coated grids

- Stain with uranyl acetate and lead citrate

- Image at 80-100kV using calibrated TEM

Advanced Large-Sample TEM Protocol for Research Applications

For connectomics research or large tissue samples, modified protocols enable homogeneous staining of samples up to centimeter scale:

Figure 2: Advanced Large-Sample TEM Staining Workflow

Key modifications for large samples include:

- Extended initial osmium tetroxide incubation (3-6 days) with temperature control at 4°C to prevent peripheral ultrastructural disintegration while ensuring central penetration [30]

- Replacement of thiocarbohydrazide with pyrogallol to reduce sample breakage

- Additional osmium tetroxide step after ferrocyanide reduction to enhance sample stability during aqueous incubations

- Cold resin infiltration (4°C) with extended times and inclusion of 95% resin in 5% acetone to maintain low viscosity and ensure complete infiltration [30]

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Machine Learning in PCD Diagnosis

Recent research demonstrates the feasibility of machine learning (ML) approaches to identify patients with possible PCD, even in the absence of specific ICD codes. One study utilized random forest models trained on claims data, showing promising performance with sensitivity of 0.75-0.94 and positive predictive value of 0.45-0.73 [31]. This approach classified 7,705 patients as PCD-positive from a cohort of 1.32 million pediatric patients, consistent with estimated PCD prevalence of 1:7,554 [31].

These ML models utilize diagnostic, procedural, and pharmaceutical codes associated with PCD clinical features, creating scalable screening methods that could reduce diagnostic delays. Future integration of TEM findings with ML algorithms may further enhance predictive accuracy, creating decision support tools that prioritize patients for specialized testing.

Technical Innovations in TEM Methodology

Advanced staining protocols now enable high-contrast en bloc staining of large tissue samples, overcoming previous limitations in sample size. These developments address critical challenges including staining inhomogeneity, sample instability, and incomplete resin infiltration that previously limited large-volume connectomic analyses [30].

Innovations such as the incorporation of contrast transfer function (CTF) correction have revolutionized TEM image quality, ensuring accurate representation of biological structures at high resolution. Precise defocus determination and CTF correction are now recognized as essential for valid structural interpretation, preventing distortion of morphological details [29].

In the evolving genetic-first diagnostic landscape, TEM maintains its essential role in the PCD diagnostic algorithm. The synergy between genetic testing and TEM ultrastructural analysis creates a powerful diagnostic combination, particularly for cases with variants of uncertain significance or novel genetic findings. By implementing the standardized protocols, troubleshooting guides, and reagent solutions outlined in this technical support center, researchers can enhance diagnostic accuracy and continue to advance our understanding of PCD pathogenesis and phenotypic expression.

The future of PCD diagnosis lies not in choosing between genetic or TEM approaches, but in their intelligent integration, supported by emerging technologies including machine learning and advanced imaging modalities. This comprehensive approach will ultimately reduce diagnostic delays and improve outcomes for patients with this complex genetic disorder.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Laterality Classifications

Problem: Initial chest X-ray (CXR) suggests situs solitus (normal organ arrangement) or situs inversus totalis (mirror-image arrangement), but you suspect a more complex situs ambiguus (heterotaxy) is present [8].

- 1. Identify the Problem: Standard CXR is insufficient to rule out subtle laterality defects. A study found that using CXR alone classified only 8% of a PCD cohort as having situs ambiguus (SA). When add-on targeted investigations were used, the prevalence of SA increased threefold to 24% [8].

- 2. List Possible Explanations:

- Cardiovascular Defects: Simple or complex congenital heart defects not visible on CXR [32] [8].

- Abdominal Situs Defects: Midline liver, intestinal malrotation, or abnormal spleen location/function [32] [6].

- Vascular Defects: Interrupted inferior vena cava, anomalous pulmonary venous return, or a right-sided aortic arch [32].

- 3. Collect the Data: Implement a standardized imaging protocol beyond CXR.

- Echocardiogram (ECHO): Essential for identifying atrial isomerism, septal defects, and transposition of the great arteries [8] [6].

- Abdominal Ultrasound (AUS): Screens for midline liver, polysplenia, asplenia, and abdominal vessel arrangement [8] [6].

- Chest CT Scan: Provides detailed bronchial anatomy (e.g., bronchial isomerism) and vascular anatomy. It is the preferred examination for definitive diagnosis [8] [6].

- 4. Eliminate Explanations: Correlate findings from all imaging modalities. A patient with a normal heart on ECHO but with a midline liver on AUS and bilateral bilobed lungs on CT would be classified as SA with left isomerism [6].

- 5. Check with Experimentation: For confirmed SA cases with respiratory symptoms, proceed with PCD-specific diagnostics (nasal nitric oxide testing, genetic sequencing) to investigate the underlying ciliopathy [32].

- 6. Identify the Cause: The inconsistent classification is resolved by using a multi-modality imaging approach, leading to an accurate situs ambiguus diagnosis and guiding further management [8].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Missed Cardiovascular Defects in PCD Research

Problem: A research subject with confirmed PCD and situs solitus has no documented cardiac workup, potentially missing critical phenotype data.

- 1. Identify the Problem: Laterality defects exist on a spectrum. Isolated cardiovascular defects can be the only manifestation of heterotaxy in a PCD population, occurring in approximately 2.3% of patients [32]. Relying solely on the absence of situs inversus can miss these defects.

- 2. List Possible Explanations:

- 3. Collect the Data:

- 4. Eliminate Explanations: A normal ECHO rules out the most common simple cardiac malformations. In a research context, this subject could then be confidently classified as PCD with situs solitus and no cardiac involvement.

- 5. Check with Experimentation: Integrate ECHO into the standard baseline assessment for all PCD research subjects, regardless of their initial situs classification.

- 6. Identify the Cause: The protocol for phenotyping in PCD research was inadequate. Implementing routine echocardiography ensures comprehensive detection of laterality defects, enriching the research data [32] [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it critical to look for laterality defects beyond situs inversus totalis in PCD research?

The presence of any laterality defect is a major diagnostic criterion for PCD. Focusing only on the classic situs inversus totalis (which occurs in about 41% of PCD cases) misses the 12% or more of patients who have situs ambiguus [32] [8]. These patients have a 200-fold increased risk of congenital heart disease compared to the general population, which significantly impacts their clinical management and is a crucial variable in research studies aiming to fully characterize the PCD phenotype [6].

Q2: What is the minimum set of imaging investigations recommended to comprehensively assess organ laterality in a PCD cohort?

While CXR is a common first step, evidence shows it is inadequate alone [8]. A robust imaging protocol should include:

- Echocardiogram (ECHO): To rule out complex and simple congenital heart disease [32] [8].

- Abdominal Ultrasound (AUS): To determine spleen status (asplenia/polysplenia) and liver position [8] [6].

- Chest CT Scan: To evaluate bronchial anatomy (e.g., bilateral eparterial bronchi in right isomerism) and vascular structures [6].

Q3: How do we classify a patient with isolated intestinal malrotation or an isolated right aortic arch?

In the context of PCD research, these isolated defects are considered part of the situs ambiguus spectrum. Studies classify such findings as "SA without cardiac malformation" or an "isolated possible laterality defect" [32]. For consistency, adopt a predefined classification system, such as one based on Botto et al., which accounts for these solitary lesions [32].

Q4: What are the common pitfalls in image interpretation for laterality defects?

The primary pitfall is a lack of systematic review. Key structures must be actively assessed [6]:

- Atrial morphology: Determine if there is right or left isomerism.

- Bronchial anatomy: The length and branching pattern of the main bronchi are key indicators of atrial situs.

- Abdominal great vessels: Note the position of the aorta and inferior vena cava relative to the spine.

- Spleen status: Confirm the presence, number, and location of the spleen.

Table 1: Prevalence of Laterality Defects in Classic PCD (Prospective Study, n=305) [32]

| Situs Classification | Prevalence in PCD (%) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Situs Solitus (SS) | 46.9% | Normal organ arrangement. |

| Situs Inversus Totalis (SI) | 41.0% | Complete mirror-image organ arrangement. |

| Situs Ambiguus (SA) | 12.1% | Spectrum of organ laterality defects. |

| SA Subgroup: Complex Cardiac Defects | 2.6% | Heterotaxy with severe cardiac malformations. |

| SA Subgroup: Simple Cardiac Defects | 2.3% | e.g., ASD, VSD, dextrocardia. |

| SA Subgroup: No Cardiac Defects | 4.6% | Vascular, abdominal, or pulmonary defects only. |

| SA Subgroup: Isolated Laterality Defect | 2.6% | A single defect, e.g., intestinal malrotation. |

Table 2: Detection of Situs Ambiguus: CXR Alone vs. Targeted Imaging (Retrospective Study, n=159) [8]

| Imaging Method | Situs Solitus (%) | Situs Inversus Totalis (%) | Situs Ambiguus (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chest X-Ray (CXR) Alone | 88 (55%) | 59 (37%) | 12 (8%) |

| CXR + Targeted Investigations | 75 (47%) | 46 (29%) | 38 (24%) |

| Common SA Defects Found | --- | --- | Cardiovascular (13%), Splenic (10%), Intestinal (6%) |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized Laterality Assessment Workflow

Diagnostic Troubleshooting Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Laterality Defect Research in PCD

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | Diagnostic screening for PCD. Low nNO is a hallmark feature. | CLD 88 series, NIOX Flex. nNO <77 nL/min (velum closure) is indicative of PCD [32]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Identifies hallmark ciliary ultrastructural defects (ODA, IDA, CA). | e.g., Zeiss EM900. Used for definitive PCD diagnosis in a research context [32]. |

| Genetic Sequencing Panels | Identifies biallelic mutations in known PCD-causing genes. | Genes include DNAH5, DNAI1 (ODA defects); CCDC39, CCDC40 (IDA/CA defects); DNAH11 (normal ultrastructure) [32]. |