Beyond the Coordinates: A Practical Guide to Interpreting, Validating, and Applying PDB Crystallography Data

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for interpreting Protein Data Bank (PDB) files from crystallography.

Beyond the Coordinates: A Practical Guide to Interpreting, Validating, and Applying PDB Crystallography Data

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for interpreting Protein Data Bank (PDB) files from crystallography. It moves beyond basic structure visualization to cover the foundational principles of PDB format, methodological approaches for systematic analysis using modern tools, strategies for troubleshooting common errors and data artifacts, and rigorous techniques for model validation and quality assessment. By integrating these skills, professionals can critically evaluate structural data to confidently inform drug design, functional analysis, and meta-studies, turning raw coordinates into reliable scientific insight.

Decoding the PDB File: A Primer on Format, Records, and Structural Metadata

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) format is a standard text file format for representing 3D structural data of biological macromolecules. It serves as the primary archive for experimentally determined structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex assemblies, with additional files available for computed structure models. For researchers in structural biology and drug development, understanding this format is crucial for interpreting, validating, and analyzing molecular structures. The format consists of lines of information called records, each designed to convey specific aspects of the structure, from atomic coordinates and connectivity to experimental metadata and secondary structure elements [1].

This guide focuses on the core record types essential for interpreting structural data from crystallography research, with particular emphasis on the distinction between standard and non-standard residues and the interpretation of key structural annotations.

Core Coordinate Records

ATOM and HETATM Records

The ATOM and HETATM records form the foundation of the 3D structural model in a PDB file, providing the Cartesian coordinates for each atom.

- ATOM records specify the 3D coordinates for atoms belonging to standard amino acids and nucleotides (i.e., the standard residues of the polymer chains) [2] [1].

- HETATM records specify the 3D coordinates for atoms that do not belong to standard polymers. This includes atoms of nonstandard residues, such as inhibitors, cofactors, ions, and solvent molecules (e.g., water) [1]. The key functional difference is that residues defined by HETATM records are, by default, not connected to other residues in the polymer chain [1].

The formal record format for ATOM and HETATM records, as defined by the wwPDB, is detailed in the table below [2] [1].

Table 1: Format of ATOM and HETATM Records

| Columns | Data Type | Field | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - 6 | Record name | "ATOM " or "HETATM" |

Identifies the record type. |

| 7 - 11* | Integer | serial |

Atom serial number. |

| 13 - 16 | Atom name | name |

Atom name. |

| 17 | Character | altLoc |

Alternate location indicator for disordered atoms. |

| 18 - 20 | Residue name | resName |

Residue name (3-letter code). |

| 22 | Character | chainID |

Chain identifier. |

| 23 - 26 | Integer | resSeq |

Residue sequence number. |

| 27 | Character | iCode |

Code for insertions of residues. |

| 31 - 38 | Real (8.3) | x |

Orthogonal coordinates for X in Angstroms. |

| 39 - 46 | Real (8.3) | y |

Orthogonal coordinates for Y in Angstroms. |

| 47 - 54 | Real (8.3) | z |

Orthogonal coordinates for Z in Angstroms. |

| 55 - 60 | Real (6.2) | occupancy |

Occupancy (default is 1.00). |

| 61 - 66 | Real (6.2) | tempFactor |

Temperature factor (B-factor). |

| 77 - 78 | LString(2) | element |

Element symbol, right-justified. |

| 79 - 80 | LString(2) | charge |

Charge on the atom. |

* Some non-standard files may use columns 6-11 for the atom serial number [1].

Example of Coordinate Records:

In this example, the first two lines are atoms of a Histidine residue, which is the first residue in chain A. The third line is a water molecule (HOH), which is a heteroatom and is numbered as residue 401 in the same chain [1].

TER Record

The TER record indicates the end of a polymer chain [1]. It is crucial for preventing visualization and modeling software from incorrectly connecting separate molecules that happen to be adjacent in the coordinate list. For example, a hemoglobin molecule with four separate subunit chains would require a TER record after the last atom of each chain [1].

Key Supporting Record Types

Beyond atomic coordinates, PDB files contain records that describe structural features and connectivity.

Table 2: Key Supporting Record Types in PDB Files

| Record Type | Data Provided by Record | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| HELIX | Location and type of helices. | One record per helix. Specifies start/end residues and helix type (e.g., right-handed alpha, 3/10) [1]. |

| SHEET | Location and organization of beta-sheets. | One record per strand. Defines sense (parallel/antiparallel) and hydrogen-bonding registration [1]. |

| SSBOND | Defines disulfide bond linkages. | Specifies the pairs of cysteine residues involved in covalent disulfide bonds [1]. |

| MODEL / ENDMDL | Delineates multiple models in a single entry. | Used primarily for NMR ensembles, where multiple structurally similar models represent the solution structure [2]. |

Interpreting Key Data Fields

Occupancy and Alternate Locations (altLoc)

The occupancy value (columns 55-60) indicates the fraction of molecules in the crystal in which a given atom occupies the specified position. The default value is 1.00, meaning the position is fully occupied [3].

The alternate location indicator (altLoc, column 17) is used when an atom or group of atoms exists in more than one distinct conformation. A non-blank character (e.g., 'A', 'B') indicates an alternate conformation for that atom [2]. Within a residue, all atoms that are associated with each other in a given conformation are assigned the same alternate location indicator [2]. The occupancies of alternate conformations for the same atom should sum to 1.0 [3].

The Temperature Factor (B-factor)

The temperature factor, or B-factor (columns 61-66), is a measure of the vibrational or dynamic displacement of an atom from its average position. It is defined as B = 8π²〈x²〉, where 〈x²〉 is the mean square displacement of the atom [3].

- Interpretation: Higher B-factors indicate greater flexibility, disorder, or mobility of an atom or region. Lower B-factors indicate well-ordered, rigid parts of the structure.

- Typical Range: For well-refined protein structures, B-factors typically range from 15-30 Ų. The core of a molecule often has low B-factors, while flexible surface loops may have values exceeding 60-70 Ų [3].

- Visualization: Molecular graphics software often uses a color spectrum (e.g., blue for low B-factor, red for high B-factor) to allow rapid identification of flexible regions [3].

Experimental Data and Structure Quality

Interpreting a structure requires assessing its quality, which is closely tied to the experimental data. For crystallographic structures, key metrics include:

Table 3: Key Crystallographic Quality Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | A measure of the detail present in the experimental diffraction data [4] [5]. | Lower values indicate higher resolution and better quality. 1.8 Å (high) vs. 3.0 Å (low). At low resolution, only the basic chain contour is visible [4]. |

| R-factor (R-work) | Agreement between the experimental diffraction data and data simulated from the atomic model [4] [5]. | Lower is better. A value of ~0.20 (or 20%) is typical. A perfect (but unrealistic) fit would be 0.00 [4]. |

| R-free | An unbiased version of the R-factor calculated using a subset of experimental data not used in model refinement [4] [5]. | Prevents over-interpretation of data. Typically ~0.05 higher than the R-factor. A large discrepancy may indicate model errors [4]. |

Electron density maps are calculated using the experimental diffraction data (structure factors) and are the primary evidence used to build the atomic model [4]. A well-built atomic model will fit neatly within its electron density. Regions with poor or missing electron density often result in missing coordinates in the final PDB file, such as disordered loops or terminal regions [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Concepts in Macromolecular Crystallography

| Reagent / Concept | Function in Structure Determination |

|---|---|

| Heavy Atoms (e.g., Metal Ions) | Used in experimental phasing methods like MIR (Multiple Isomorphous Replacement). Their strong scattering power helps estimate the phases of X-ray reflections [4]. |

| Selenomethionine | A methionine analog where sulfur is replaced with selenium. Routinely incorporated into proteins for phasing via MAD (Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion) [4]. |

| Cryo-protectants | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, polyethylene glycol) used to protect flash-cooled crystals from forming ice, which can damage the crystal lattice during data collection. |

| Structure Factors | The primary experimental data from a crystallography experiment, containing the amplitudes and (estimated) phases needed to calculate an electron density map [4]. |

| Biological Assembly | The functional, native form of the molecule(s). The crystal's "Asymmetric Unit" may contain only a portion of the biological assembly, which is generated by applying crystallographic symmetry [6]. |

Logical Workflow for Interpreting a PDB Structure from Crystallography

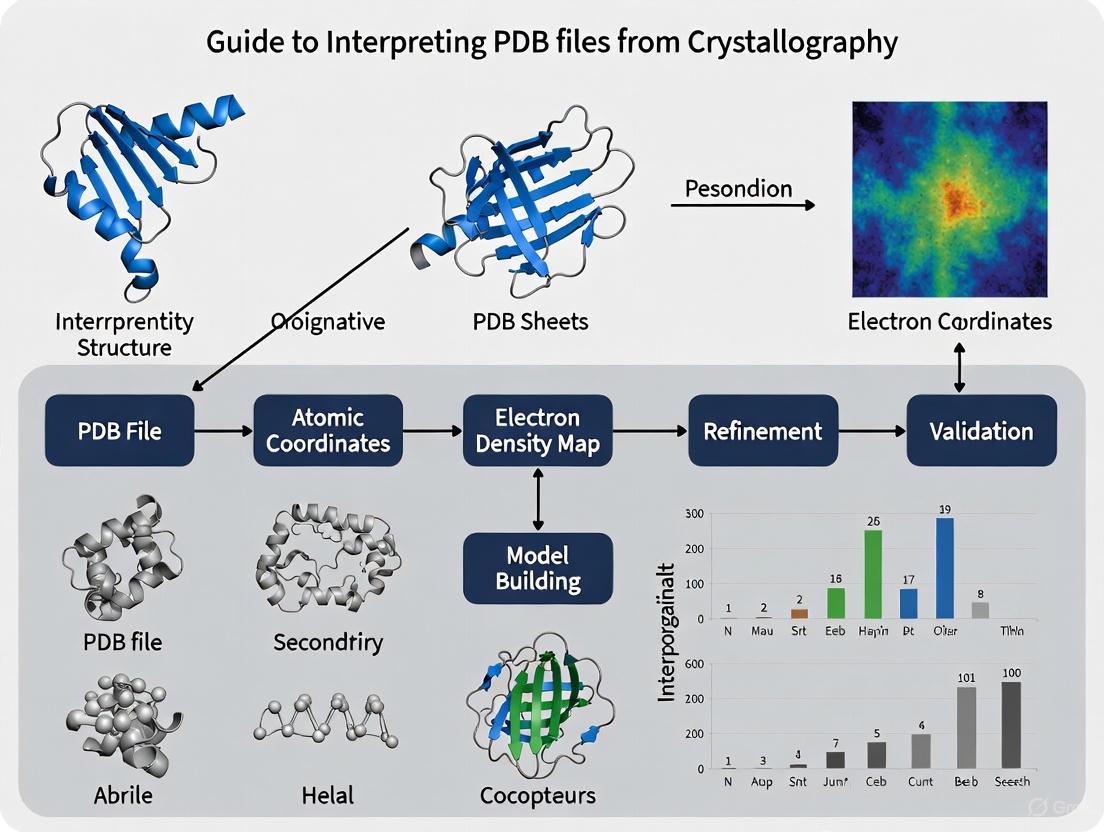

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between key PDB record types and the process of building and interpreting a structural model from experimental data.

Figure 1: Logical workflow from experimental data to a full structural model, showing the roles of key PDB record types. The process begins with experimental data, which is used to calculate an electron density map. The model is built and refined into this map, resulting in ATOM and HETATM coordinate records. These primary records are annotated by secondary structure (HELIX, SHEET) and connectivity (SSBOND) records. The entire dataset undergoes quality validation before the functional biological assembly is generated.

The Structure Summary page on the RCSB PDB website serves as the primary entry point for accessing information about a experimentally determined biological macromolecular structure. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, efficiently extracting and interpreting the essential metadata from this page is a critical skill. This metadata provides the necessary context about the experiment, allowing for an assessment of the model's quality and reliability, which is foundational for any subsequent analysis, from structure-based drug design to understanding mechanistic biology. This guide details the core metadata categories presented on the Structure Summary page, framed within the broader context of interpreting PDB files from crystallographic research [7] [8].

Core Crystallographic Metadata and Quality Indicators

The quality and interpretation of a structural model are underpinned by specific crystallographic metrics. These quantitative indicators, typically found under the Experiment tab, are essential for evaluating the reliability of the atomic coordinates [7].

Resolution

Resolution is a measure of the detail present in the diffraction data and the resulting electron density map. It is arguably the single most important indicator of structure quality [4].

- Definition: Resolution reflects how well the crystal diffracts X-rays. Highly ordered, perfect crystals yield high-resolution data with fine detail, while crystals with internal flexibility or disorder yield lower-resolution data showing only basic molecular contours [4].

- Interpretation: The numerical value (in Ångströms) represents the minimum distance between two distinguishable features in the electron density. Smaller values indicate higher resolution. The table below provides a practical guide for interpreting resolution values in protein crystallography:

Table 1: Interpretation of Resolution Ranges in Protein Crystallography

| Resolution Range (Å) | Quality Designation | Typical Level of Detail Visible | Confidence in Atomic Positions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 1.0 Å | Ultra-high resolution | Individual atoms; alternate side-chain conformations | Very High |

| 1.0 - 1.5 Å | High resolution | Most individual atoms; well-defined bond lengths and angles | High |

| 1.5 - 2.0 Å | Medium resolution | Clear backbone and side-chain density; ordered water molecules | Moderate to High |

| 2.0 - 2.5 Å | Medium-low resolution | General chain trace; bulky side-chain density | Moderate |

| 2.5 - 3.0 Å | Low resolution | Basic protein fold and secondary structure | Low |

| ≥ 3.0 Å | Very low resolution | Coarse molecular contours; atomic model is inferred | Low |

R-Value and R-Free

The R-value (also called R-work) and R-free are statistical measures that report on the agreement between the atomic model and the experimental diffraction data [4].

- R-value: This measures how well the simulated diffraction pattern, calculated from the atomic model, matches the experimentally observed diffraction pattern. A perfect fit would have an R-value of 0, while a random set of atoms has an R-value of about 0.63. For a well-refined structure, typical R-values are around 0.20 (or 20%) [4].

- R-free: This is a cross-validation metric designed to prevent overfitting or over-interpretation of the data during the refinement process. Before refinement begins, approximately 10% of the experimental diffraction data is set aside and not used. The R-free is then calculated by comparing this unused data to the model. An ideal, unbiased model will have an R-free value similar to, though typically slightly higher than, the R-value (often around 0.26). A large discrepancy between R-value and R-free can indicate that the model has been over-refined to fit the noise in the experimental data [4].

Structure Factors and Electron Density

The primary experimental data from a crystallographic experiment are the structure factors, which are used to calculate an electron density map [4].

- The Experiment: When a crystal is exposed to an X-ray beam, it produces a diffraction pattern consisting of a characteristic array of spots (reflections). Each reflection has an intensity (amplitude) and a phase angle [4].

- From Data to Map: The intensities are measured directly, but the phases must be estimated indirectly using methods such as molecular replacement (using a known similar structure), isomorphous replacement (adding heavy atoms), or anomalous scattering (using atoms like selenium). The combination of amplitudes and phases allows for the calculation of the electron density map, which is interpreted to build the atomic model [4].

- Data Availability: For many structures, the authors deposit the primary structure factor data. These files can be downloaded from the Structure Summary page and contain the h, k, l indices, amplitudes/intensities, and standard uncertainties for each reflection, enabling researchers to recalculate electron density maps [4].

Experimental Methodology and Workflow

Understanding the experimental pipeline is crucial for contextualizing the metadata. The following diagram and protocol outline the key steps from crystal to deposited structure.

Figure 1: The macromolecular crystallography structure determination workflow.

Detailed Crystallographic Protocol

- Crystallization and Data Collection: The purified macromolecule is crystallized. A single crystal is mounted and exposed to a narrow, intense beam of X-rays, and the resulting diffraction pattern is captured by a detector [4].

- Data Processing: Software (e.g., HKL-2000, XDS) indexes the diffraction spots and integrates their intensities. This step produces a list of structure factor amplitudes and their uncertainties. Key metrics like resolution and data completeness are determined here [4] [9].

- Phase Estimation (The "Phase Problem"): Since the phase information is lost in the diffraction experiment, it must be determined indirectly [4].

- Molecular Replacement (MR): Used when a similar structure is already known. The known model is placed and oriented within the unit cell of the unknown crystal to provide initial phase estimates [4].

- Isomorphous Replacement (MIR/SIR): Heavy atoms (e.g., Hg, Pt) are introduced into the crystal. Differences in diffraction intensities between native and heavy-atom derivative crystals are used to solve the phase problem [4].

- Anomalous Scattering (MAD/SAD): Atoms with anomalous scattering properties (e.g., Selenium in selenomethionine) are incorporated. Data collected at specific X-ray wavelengths allows for direct phasing [4].

- Electron Density Map Calculation and Model Building: The initial phases and measured amplitudes are used to compute an electron density map. Researchers then build an atomic model into this map using software like Coot, tracing the protein chain and placing side chains [4].

- Refinement and Validation: The initial model is refined against the diffraction data using programs like REFMAC or PHENIX. This iterative process adjusts atomic coordinates and temperature factors (B-factors) to improve the fit (lowering the R-value). The R-free value is monitored to guard against overfitting. The final model is validated using geometric and stereochemical checks before deposition [4].

The following tools and resources are essential for working with PDB data, both for extracting information and for preparing new depositions.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools and Resources for PDB Data

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Metadata Extraction/Deposition |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB Structure Summary Page | Centralized web interface for accessing PDB entries. | The primary source for viewing and extracting core metadata, experimental details, and links to download data files [7]. |

| pdb_extract | A pre-deposition software tool. | Extracts and compiles metadata from the output files of various structure determination programs (e.g., data from Aimless, REFMAC) and generates a complete PDBx/mmCIF file ready for deposition [10] [9]. |

| PDBj CIF Editor | An online editor for PDBx/mmCIF files. | Allows depositors to create and edit a reusable metadata template file, ensuring all mandatory information is provided for efficient deposition via the OneDep system [10] [9]. |

| OneDep Deposition System | The unified wwPDB system for depositing structures. | Accepts the mmCIF files prepared by pdb_extract and the metadata templates from the CIF editor, and guides depositors through validation and submission [10]. |

| Structure Factor Files (e.g., MTZ format) | Files containing the primary diffraction data. | Can be downloaded for many entries, allowing researchers to recalculate electron density maps and perform their own analyses. OneDep accepts MTZ format for deposition [4] [9]. |

Advanced Metadata and the pdb_extract Tool

For depositors and advanced users, the pdb_extract tool is indispensable for handling the extensive metadata generated during structure determination. It automates the extraction of key details from the log files of data processing and refinement software, minimizing errors and saving time during deposition [10] [9]. The tool supports a wide array of software packages, ensuring that critical processing and refinement metadata is accurately captured. The following diagram illustrates the data flow during file preparation using pdb_extract.

Figure 2: Data flow for preparing a deposition using the pdb_extract tool.

The PDB Structure Summary page is a gateway to a rich array of metadata that is vital for interpreting, validating, and utilizing structural models. By systematically extracting and understanding key indicators like resolution, R-value, and R-free, and by appreciating the experimental workflow that generated them, researchers can make informed judgments about the suitability of a structure for their specific research needs. Furthermore, tools like pdb_extract and resources like the PDBj CIF Editor streamline the process of preparing and depositing new structures, ensuring the continued growth and quality of the structural archive. Mastery of this metadata is, therefore, not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental component of rigorous structural biology and drug development.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) archive organizes three-dimensional structural data using a hierarchical framework that reflects the natural organization of biological macromolecules. This structure simplifies the complex process of searching, visualizing, and analyzing molecular structures. Understanding this hierarchy is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to correctly interpret PDB files from crystallography research and other structural biology methods. Biomolecules exhibit inherent hierarchical organization; for instance, proteins are composed of linear amino acid chains that fold into subunits, which then may associate into higher-order functional complexes with other proteins, nucleic acids, small molecule ligands, and solvent molecules [11]. The PDB archive represents this biological reality through four primary levels of structural organization: Entry, Entity, Instance, and Assembly. This systematic organization enables precise querying and meaningful visualization of structural data, ensuring that researchers can access both the detailed atomic coordinates and the biologically functional forms of macromolecules.

Core Hierarchical Levels: Definitions and Relationships

The PDB data model is built upon four fundamental levels, each serving a distinct purpose in the structural description.

ENTRY: An ENTRY encompasses all data pertaining to a single structure deposited in the PDB. It is the top-level container identified by a unique PDB ID, which is currently a 4-character alphanumeric code (e.g., 2hbs for sickle cell hemoglobin) [11]. Future extensions will use eight-character codes prefixed by 'pdb' [12]. Every entry contains at least one polymer or branched entity.

ENTITY: An ENTITY defines a chemically unique molecule type within an entry. It distinguishes different molecular species, which can be polymeric (e.g., a specific protein chain or DNA strand), non-polymeric (e.g., a soluble ligand, ion, or drug molecule), or branched (e.g., oligosaccharides) [11] [12]. A single entry can contain multiple entities, such as different protein chains or ligand types. Entities are often linked to external database identifiers; for example, a protein entity might be mapped to a UniProt Accession Code [12].

INSTANCE: An INSTANCE represents a specific occurrence or copy of an entity within the crystallographic asymmetric unit or deposited model. An entry may contain multiple instances of a single entity. For example, a homodimeric protein would have one protein entity but two instances of that entity in the entry [11]. Each instance of a polymer is assigned a unique Chain ID (e.g., A, B, AA) for easy reference, selection, and display [11] [12].

ASSEMBLY: An ASSEMBLY describes a biologically relevant group of instances that form a stable functional complex. The assembly represents the functional form of the molecule, such as a hemoglobin tetramer that binds oxygen in the blood. Assemblies are generated by applying symmetry operations to the instances in the asymmetric unit or by selecting specific subsets of polymers and ligands [11] [13]. A structure may have multiple biological assemblies, each assigned a numerical Assembly ID [11].

Table 1: Core Hierarchical Levels in the PDB

| Level | Description | Identifier | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | All data for a deposited structure | PDB ID (4-character) | 2hbs [11] |

| Entity | Chemically unique molecule | Entity ID | Protein alpha chain [11] |

| Instance | Specific occurrence of an entity | Chain ID | Chain A, Chain B [11] [12] |

| Assembly | Biologically functional complex | Assembly ID | Hemoglobin tetramer [11] |

The relationships between these levels are crucial for accurate data interpretation. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow from the deposited entry to the biologically relevant assembly:

Practical Application: The Case of Hemoglobin

The structure of hemoglobin (PDB ID: 2hbs) provides an excellent case study for understanding the practical application of the PDB hierarchy. This entry contains two complete sickle cell hemoglobin tetramers, which include heme cofactors and numerous water molecules [11].

- Entry Level: The PDB ID 2hbs represents the entire deposited dataset, including coordinates, experimental metadata, and annotations [11].

- Entity Level: The entry contains distinct chemical molecules. These include two polymeric entities (the alpha globin chain and the beta globin chain) and two non-polymeric entities (heme and water) [11].

- Instance Level: The entry contains multiple copies of these entities. Specifically, there are several instances of the alpha chain and beta chain entities, each assigned unique chain IDs. There are also eight instances of the heme entity (each bound to a protein chain) and several hundred instances of water [11].

- Assembly Level: Each hemoglobin tetramer is designated as a biological assembly. This assembly consists of a specific grouping of two instances of the alpha chain entity and two instances of the beta chain entity, along with their associated hemes and waters. This tetrameric form is the functional unit responsible for oxygen binding and delivery in the blood [11].

Table 2: Hierarchical Components in PDB Entry 2hbs (Hemoglobin)

| Hierarchy Level | Components in 2hbs | Count | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Entire dataset for 2hbs | 1 Entry | Complete structural deposit |

| Polymer Entities | Alpha globin chain, Beta globin chain | 2 Entities | Genetically distinct polypeptides |

| Non-Polymer Entities | Heme (HEM), Water (HOH) | 2 Entities | Cofactor and solvent |

| Chain Instances | Alpha chain copies, Beta chain copies | Multiple Instances | Individual molecules in crystal |

| Heme Instances | Heme groups bound to chains | 8 Instances | Oxygen-binding sites |

| Biological Assemblies | Hemoglobin tetramers | 2 Assemblies | Functional oxygen carriers |

The Asymmetric Unit vs. The Biological Assembly

A critical distinction in crystallography is between the asymmetric unit and the biological assembly, which directly impacts the interpretation of PDB files.

Asymmetric Unit: The asymmetric unit is the smallest portion of the crystal structure to which symmetry operations can be applied to generate the complete unit cell, which is the repeating unit of the crystal [14]. The primary coordinate file deposited by researchers typically contains only the asymmetric unit, which may or may not correspond to the biological assembly. The content depends on the molecule's position and conformation within the crystal lattice [14]. The asymmetric unit may contain one biological assembly, a portion of an assembly, or multiple assemblies [14].

Biological Assembly: The biological assembly is the macromolecular structure believed to be the functional form of the molecule in vivo [14]. For example, the functional form of hemoglobin is a tetramer with four chains, even if the asymmetric unit contains only a portion of this complex. Generating the biological assembly requires applying crystallographic symmetry operations (rotations, translations, or screw axes) to the coordinates in the asymmetric unit, or selecting a specific subset of these coordinates [14].

The relationship between these units varies across structures, as demonstrated by different hemoglobin entries:

- In PDB 2hhb, the biological assembly is identical to the asymmetric unit, containing one complete hemoglobin tetramer [14].

- In PDB 1out, the asymmetric unit contains only half of the hemoglobin tetramer (two chains). The complete biological assembly is generated by applying a crystallographic two-fold symmetry operation to produce the other two chains [14].

- In PDB 1hv4, the asymmetric unit contains two complete hemoglobin molecules (eight chains). The biological assembly in this case is defined as one hemoglobin tetramer, which constitutes half of the asymmetric unit [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process of determining the biological assembly from the deposited coordinates:

Experimental Protocols for Assembly Determination

Determining the correct biological assembly is a critical step in structural analysis. The process involves both experimental evidence and computational analysis, with protocols varying by structure determination method.

For X-ray Crystallography Structures

The biological assembly for crystal structures is determined through a multi-step process that combines author input with computational validation. The experimental protocol involves:

- Author Specification: During deposition, authors provide their hypothesized biological assembly based on biochemical, biophysical, or functional data. This constitutes the "author-provided" assembly [14].

- Computational Analysis: Software tools, most commonly PISA (Protein Interfaces, Surfaces, and Assemblies), automatically analyze the crystal structure [14]. The software calculates:

- Buried Surface Area: The surface area removed from contact with solvent when two molecular surfaces meet.

- Interaction Energies: The thermodynamic stability of interfaces between chains.

- Solvation Free Energy: The energy gain upon complex formation.

- Assembly Prediction: Based on these calculations, the software predicts probable quaternary structures and assigns a likelihood to each potential assembly [14].

- Consensus Determination: The final biological assemblies reported in the entry include a remark indicating their origin—"author provided," "software determined," or both. In cases of discrepancy, multiple assemblies may be presented. For example, in PDB entry 3fad (T4 lysozyme), both a monomeric (author- and software-determined) and a dimeric (software-determined only) assembly are provided [14].

For NMR and Computed Structure Models

The protocols differ for structures determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and computed structure models (CSMs):

- NMR Structures: NMR commonly deposits an ensemble of structures. The best representative model is made available as the "Assembly" coordinates. In practice, the assembly for NMR structures is typically identical to its corresponding representative model [13].

- Computed Structure Models (CSMs): For predicted structures from resources like AlphaFold DB, the assembly coordinates are the same as the model (predicted structure) coordinates. The assembly is included primarily to enable structure-based query and analysis alongside experimental structures [13].

Successful navigation and interpretation of PDB hierarchies require familiarity with specific data resources, visualization tools, and analytical software.

Table 3: Essential Resources for PDB Data Interpretation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Hierarchy |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB Website | Database Portal | Main access point to PDB data [6] | Exploring entries, entities, instances, and assemblies via Structure Summary pages. |

| Mol* Viewer | Visualization Software | Interactive 3D structure visualization [13] | Visualizing different hierarchy levels; switching between Model and Assembly views. |

| PISA (Software) | Analytical Tool | Predicts biological assemblies from crystal data [14] | Determining probable quaternary structures based on interface properties. |

| Chemical Component Dictionary | Reference Database | Standardized chemical descriptions of small molecules [12] | Defining non-polymer entities and their atom names. |

| UniProt | Protein Sequence Database | Central repository of protein sequence/functional data [12] | Mapping polymer entities to external sequence and functional data. |

| EMDB (Electron Microscopy Data Bank) | Structural Database | Archive of 3DEM maps [12] | Connecting EM structures (entries) to their underlying density maps. |

Accessing and Visualizing Hierarchical Data

The RCSB PDB website and its integrated Mol* viewer provide powerful interfaces for accessing and visualizing the different levels of the structural hierarchy.

The Structure Summary page on the RCSB PDB website serves as the central hub for information about a specific entry. Key sections relevant to the hierarchy include:

- Snapshot of the Structure: Located at the top left, this box displays the biological assembly by default for X-ray and 3DEM structures, or the NMR ensemble for NMR structures [6]. The heading bar allows users to toggle between views of the asymmetric unit and different biological assemblies [6].

- Header Section: This area displays the PDB ID, structure title, classification, source organisms, and deposition information [6]. It also provides critical quality assessment tools, such as the wwPDB Validation slider for experimental structures and the Model Confidence metrics (pLDDT scores) for CSMs [6].

- Interactive Viewing Options: Hyperlinks below the snapshot offer specialized visualization pathways in Mol*, including "Structure" (general view), "Ligand Interaction" (zoomed on a specific ligand), and "Electron Density" (for X-ray structures) [6].

Visualization and Analysis in Mol*

The Mol* viewer offers precise control over the display of hierarchical components through its Components and Structure panels:

- Structure Panel: This panel allows users to select and display different forms of the structure. Options include "Model" (the deposited coordinates), "Assembly" (the biologically relevant form), "Unit Cell" (for X-ray entries), and "Super Cell" [13]. Preset views facilitate quick toggling between these representations [13].

- Components Panel: This panel enables manipulation and display of specific parts of the structure. Users can add representations for different components (polymers, ligands, waters) and apply various visual styles (cartoon, ball-and-stick, surface) [13]. Preset display options, such as "Polymer & Ligand" or "Atomic Detail," automatically configure appropriate representations for different hierarchy levels [13].

- Measurement Tools: The Measurements Panel allows users to make quantitative geometric analyses (distances, angles, dihedral angles) by selecting specific atoms from different instances and entities [13]. This is essential for validating molecular interactions within an assembly.

Correct interpretation of PDB data requires careful navigation of its intrinsic hierarchy. By understanding the distinctions between entries, entities, instances, and assemblies—and particularly the critical difference between the crystallographic asymmetric unit and the biological assembly—researchers can ensure they are analyzing the functionally relevant form of a macromolecule. The tools and resources outlined in this guide provide a robust framework for exploring this hierarchical data, ultimately supporting accurate structural analysis in basic research and drug development.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) serves as a global archive for the three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules, with the majority determined by X-ray crystallography [15]. As of 2024, the archive contains over 190,000 crystal structures, representing a foundational resource for millions of researchers worldwide [16] [15]. This technical guide examines how the crystallographic method fundamentally shapes the structural data contained within PDB files, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the critical framework needed to accurately interpret these essential resources. Understanding the intrinsic connection between experimental methodology and data representation is paramount, as the PDB's importance extends to training advanced structural prediction algorithms like AlphaFold, making the highest data quality essential for future scientific breakthroughs [16].

The process of crystallography involves several transformative steps—from growing a crystal to calculating an electron density map and building an atomic model. Each stage introduces specific constraints and potential artifacts that become permanently embedded in the final coordinates deposited to the PDB. This article provides an in-depth analysis of these methodological influences, offering detailed protocols for evaluating structural quality and practical frameworks for interpreting crystallographic data within the context of drug discovery and basic research.

Foundational Concepts: From Crystal to Electron Density

The Crystallographic Phase Problem

X-ray crystallography does not directly produce an atomic model. When X-rays strike a crystal, they diffract, producing a pattern of spots whose intensities can be measured. These intensities provide the amplitude information for the structure factors but crucially lack phase information—a limitation known as the "phase problem" that must be solved to calculate an interpretable electron density map. The experimental process involves multiple transformations of the data, each with specific implications for the final model:

- Crystal Growth: Macromolecular crystals are typically grown from aqueous solutions containing precipitants, resulting in crystals that are approximately 50% solvent by volume. This high solvent content often leads to dynamic disorder that impacts overall data quality and resolution.

- Data Collection: Diffraction patterns are collected, and intensities are integrated to produce structure factor amplitudes. Radiation damage during data collection can introduce decay in diffraction power, particularly in sensitive side chains.

- Phase Determination: Experimental methods (MAD, SAD, MIR) or molecular replacement (MR) are used to obtain initial phase estimates. MR, which uses a known homologous structure as a search model, can potentially bias the resulting model toward the template.

- Electron Density Calculation: The initial experimentally-determined phases are combined with the measured amplitudes to calculate the first electron density maps, which are then iteratively improved through refinement.

Resolution as a Quality Determinant

The resolution limit of a crystallographic experiment represents the smallest distance between two points that can be distinguished as separate features in the electron density map. This parameter fundamentally constrains what can be observed and modeled in a structure, with profound implications for biological interpretation, particularly in drug design where precise atomic interactions are critical.

Table 1: Interpretation of Crystallographic Resolution Ranges

| Resolution Range (Å) | Structural Features Discernible | Typical Applications & Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| <1.5 Š(Atomic/Ultra-high) | Individual atoms clearly resolved; alternative conformations visible; hydrogen atoms often detectable | Detailed mechanistic studies; accurate ligand geometry; reliable water networks; low B-factors typically <20 Ų |

| 1.5-2.2 Å (High) | Main-chain and side-chain features clear; some alternative conformations detectable; water molecules placed | Standard for publication; reliable protein-ligand interactions; backbone carbonyl oxygens visible |

| 2.2-3.0 Å (Medium) | Chain tracing reliable; bulky side chains distinguishable; small side chains may be ambiguous | Fold determination; identifying binding sites; caution needed for specific interactions; higher B-factors common |

| >3.0 Å (Low) | Polypeptide chain trace visible as continuous tube; side chains as undifferentiated bulk | Domain organization; large conformational changes; severe caution in interpreting atomic interactions |

Interpreting the PDB Format: A Crystallographic Perspective

Critical Data Fields and Their Structural Significance

The PDB file format encapsulates both the atomic model and essential metadata from the crystallographic experiment [1] [17]. Proper interpretation requires understanding how specific records reflect the experimental process and its limitations:

- ATOM/HETATM Records: Contain the orthogonal Ångström coordinates (X,Y,Z) for all modeled atoms [1]. The precision (3 decimal places) often exceeds the actual accuracy, which is determined by the resolution limit.

- Occupancy and Alternate Conformations: Due to local flexibility or static disorder, amino acid side chains may adopt multiple conformations [3]. These are represented with partial occupancy values (summing to 1.0 for all conformations at a given position) and distinguished by alternate location indicators [3].

- Temperature Factors (B-factors): Quantify atomic displacement or disorder, calculated as B=8π²⟨x²⟩, where ⟨x²⟩ represents the mean-square displacement from the average position [3]. Higher values indicate greater flexibility or uncertainty in atomic position.

Table 2: Key Crystallographic Parameters in PDB Files and Their Interpretation

| Parameter | Location in PDB File | Technical Significance | Interpretation Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | HEADER or REMARK records | Minimum interplanar spacing measured during data collection | Lower values indicate higher detail; impacts model accuracy |

| R-factor/R-free | REMARK 3 | Measures agreement between model and experimental data | R-free >0.40 indicates serious problems; difference >0.05 between R-factor and R-free suggests overfitting |

| B-factors (Temperature Factors) | Columns 61-66 of ATOM/HETATM records [3] | Quantify atomic displacement or positional uncertainty | Core regions typically 15-30 Ų; values >60-70 Ų indicate high flexibility or potential errors |

| Occupancy | Columns 55-60 of ATOM/HETATM records | Fraction of molecules in crystal where atom occupies specified position | Values <1.0 indicate partial occupancy or multiple conformations; should sum to 1.0 for all conformations of an atom |

| Missing Residues/Atoms | Not present in coordinate section | Regions with poor or uninterpretable electron density | Common in flexible loops or surface regions; check REMARK 465 for specifically missing residues |

Validation Metrics and Error Detection

The PDB deposition process now includes extensive validation reports that provide crucial metrics for assessing model quality. The clashscore identifies steric overlaps between atoms, with values >20 potentially indicating packing problems. Ramachandran outliers identify energetically unfavorable backbone conformations, with >5% outliers suggesting possible model errors. Rotamer outliers flag unusual side-chain conformations, which may indicate incorrect modeling or genuine functional states. Real-space correlation coefficients (RSCC) measure how well the atomic model agrees with the experimental electron density locally, with values <0.8 indicating poor fit that warrants careful inspection.

Diagram 1: Crystallographic Structure Determination Workflow. The iterative process of model building and refinement (green and red nodes) demonstrates how initial phases are progressively improved to produce the final validated structure.

Advanced Considerations in Structure Interpretation

Biological Assemblies vs. Asymmetric Units

A critical distinction in PDB interpretation lies between the asymmetric unit (the minimal repeating unit of the crystal) and the biological assembly (the functional form of the molecule in vivo) [13]. Crystallographic symmetry operations (detailed in MTRIX and SMTRY records) must be applied to generate the biologically relevant oligomer. Visualization tools like Mol* provide toggles between these representations, allowing researchers to examine different biological assembly hypotheses [13]. For structures determined by X-ray crystallography, the assembly coordinates are generated by applying specific symmetry operations to the deposited coordinates, which may represent only a portion of the functional complex [13].

Detecting and Managing Duplicate Structures

Recent research has revealed that the PDB contains numerous pairs of protein structures with nearly identical main-chain coordinates [16]. These duplicates arise because the PDB lacks mechanisms to detect potentially duplicate submissions during deposition [16]. Some represent independent determinations of the same structure, while others may be modeling efforts of ligand binding that "masquerade as experimentally determined structures" [16]. Researchers should utilize tools like the Backbone Rigid Invariant (BRI) algorithm to identify such duplicates, particularly when conducting data mining or machine learning applications where duplicates can skew results [16]. Proposed solutions include obsoleting duplicate entries or marking them with clear 'CAVEAT' records to alert users [16].

Ligand Binding and Electron Density Interpretation

Small molecules (ligands, inhibitors, cofactors) are represented as HETATM records in PDB files [1]. Assessment of ligand geometry should include examination of the real-space correlation coefficient (RSCC) to evaluate how well the atomic model agrees with the experimental electron density. Additionally, omit maps (calculated after removing the ligand from the model) provide unbiased evidence for ligand binding. Drug development professionals should be particularly cautious of ligands with poor density, high B-factors, or unusual geometries that may indicate incorrect modeling or partial occupancy issues.

Diagram 2: Data Quality Relationships in Crystallography. The resolution limit (red) fundamentally constrains map quality, which directly determines atomic model precision and ultimately biological confidence.

Practical Protocols for Structure Evaluation

Step-by-Step Structure Validation Protocol

- Initial Quality Assessment: Check resolution, R-work, and R-free values from the PDB header. Verify that the R-free value is within 0.05 of the R-work value.

- Geometry Evaluation: Examine Ramachandran plot statistics, ensuring >90% of residues fall in favored regions and <1% are outliers unless justified by special structural features.

- B-factor Analysis: Visualize B-factor distribution along the protein chain using color coding (blue→red for low→high values). Identify regions with unusually high B-factors (>60-70 Ų) that may indicate flexibility or modeling errors [3].

- Ligand and Active Site Inspection: For structures with bound ligands, generate omit maps to verify ligand placement without model bias. Check ligand geometry and interactions with the protein.

- Comparison with Biological Knowledge: Evaluate whether the structural observations align with biochemical and functional data, investigating discrepancies that may indicate crystallization artifacts.

Visualization Tools and Techniques

Modern visualization software like Mol* provides powerful capabilities for examining crystallographic data [13] [18]. Key features include:

- Model vs. Assembly Toggle: Switch between asymmetric unit and biological assembly views [13].

- B-factor Coloring: Apply "temperature rainbow" coloring schemes to visualize flexibility and disorder [3].

- Validation Coloring: Color structures by validation metrics like geometry quality or density fit to identify potential problem areas [13].

- Measurement Tools: Precisely measure distances, angles, and dihedral angles for specific atomic interactions [13].

- Symmetry Display: Generate symmetry mates to examine crystal packing interfaces and potential biological interfaces [13].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Crystallography

| Reagent/Category | Function in Crystallography | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Initial identification of crystallization conditions | Commercial screens (e.g., Hampton Research) contain diverse precipitant combinations to sample chemical space |

| Cryoprotectants | Protect crystals during flash-cooling for data collection | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, or oils prevent ice formation that damages crystal order |

| Heavy Atom Compounds | Experimental phasing via MAD/SAD | Platinum, gold, mercury, or selenium compounds derivative native proteins for phase determination |

| Crystal Harvesting Tools | Manipulation of fragile crystals | Micromounts, loops, and magnetic caps enable precise crystal handling with minimal damage |

| Ligand Soaking Solutions | Introducing small molecules into pre-grown crystals | Optimization of concentration, soaking time, and solvent composition to maintain crystal integrity |

Crystallography provides an immensely powerful window into molecular structure, but the data it generates must be interpreted with a clear understanding of methodological constraints. Resolution limits, crystal packing effects, disorder, and the model-building process all leave distinct signatures in PDB files that influence biological interpretation. For drug development professionals, this critical perspective is essential when evaluating potential ligand-binding sites, assessing protein flexibility, or designing new compounds based on structural information. As structural biology continues to evolve, with new methods like the "Crystal Clear" approach enabling direct visualization of crystal interiors, our ability to connect methodological approach to structural interpretation will only grow in importance [19]. By maintaining rigorous standards for structure validation and developing increasingly sophisticated tools for detecting artifacts like duplicate entries, the structural biology community can ensure that the PDB remains a trustworthy foundation for scientific discovery and therapeutic innovation [16].

From Static Files to Dynamic Insights: Analytical Workflows for Drug Discovery

Leveraging RCSB PDB Tools for Automated Binding Site and Ligand Analysis

Within the Protein Data Bank (PDB), small molecules such as ions, cofactors, inhibitors, and drugs that interact with biological polymers (proteins and nucleic acids) are collectively termed ligands [20]. These molecules are crucial for understanding biomolecular function, as they often bind to specific pockets, cavities, or surfaces to facilitate structural stability or execute functional roles [20]. Over 70% of PDB structures contain at least one small-molecule ligand, excluding water molecules, highlighting their fundamental importance in structural biology [21]. For researchers focused on crystallography, accurately interpreting these ligand-binding site interactions is paramount, as the molecular details of these complexes provide insights into mechanisms of action, inform drug discovery efforts, and help elucidate the structural basis of diseases.

The RCSB PDB provides a sophisticated infrastructure for studying these interactions. Each unique small-molecule ligand is defined in the wwPDB Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD) with a distinct identifier (CCD ID) and a detailed chemical description [21]. Furthermore, the resource has implemented robust ligand validation tools that enable researchers to assess the quality and reliability of ligand structures, which is a critical first step before undertaking any detailed analysis [20] [21]. This guide details the methodologies for leveraging RCSB PDB tools to perform automated, rigorous analysis of binding sites and their resident ligands, with a focus on interpreting crystallographic data within the framework of a broader research thesis.

The RCSB PDB offers an integrated suite of tools and resources specifically designed for the interrogation of ligands and their binding sites. Familiarity with these core resources is a prerequisite for effective analysis.

- Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD): This is the authoritative repository for every unique small molecule and molecular subunit found in the PDB archive [22]. Each chemical component is assigned a unique three-letter code (e.g., "ATP" for adenosine triphosphate, "HEM" for heme) and is associated with detailed chemical information including stereochemistry, chemical descriptors (SMILES and InChI), systematic names, and idealized 3D coordinates [22]. The CCD is foundational for ensuring consistent chemical representation across the entire archive.

- Ligand Validation Tools: A critical step in any analysis is assessing the quality of the ligand structure itself. The RCSB PDB provides comprehensive validation reports for ligands in X-ray structures, which include metrics on the fit of the atomic model to the experimental electron density and the accuracy of its chemical geometry [20] [21]. These are presented via intuitive 1D sliders and 2D plots on the structure summary page and the dedicated "Ligands" tab, allowing researchers to quickly identify the best-instance of a ligand within a structure or across multiple structures [21].

- Programmatic Access (APIs): For automated, large-scale analysis, the RCSB PDB provides programmatic access via a GraphQL API and RESTful services [23]. This allows bioinformaticians and developers to programmatically search, retrieve, and analyze structural data, including specific ligand information and binding affinity data, integrating it into custom pipelines and workflows.

Table 1: Key RCSB PDB Resources for Ligand and Binding Site Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD) | Data Dictionary | Defines chemical identity and ideal coordinates for every unique small molecule. | Web Interface, API Download |

| Ligand Validation Report | Quality Assessment | Provides metrics on electron density fit (RSR, RSCC) and geometry (RMSZ-bonds/angles). | Structure Summary Page, "Ligands" Tab |

| BIRD (Biologically Interesting molecule Reference Dictionary) | Data Dictionary | Defines complex ligands (e.g., peptides, antibiotics) composed of several subcomponents. | Web Interface, API |

| Structure Summary Page | Web Portal | Central hub for all information related to a specific PDB entry, including ligand sliders. | Web Interface (RCSB.org) |

| GraphQL & REST APIs | Programmatic Interface | Enables automated querying and retrieval of structural and ligand data. | Programmatic Access |

Methodologies for Ligand Structure Quality Assessment

Before analyzing a ligand's interactions, it is essential to determine the reliability of its structural model. The RCSB PDB's ligand quality assessment is based on two principal composite indicators derived from validation data in the wwPDB validation report [21].

Core Validation Metrics

The validation of a ligand structure involves several key metrics that assess different aspects of model quality:

- Goodness of Fit to Experimental Data: This measures how well the atomic coordinates of the ligand agree with the experimental electron density map from X-ray crystallography. The primary metrics are the Real Space R-factor (RSR) and the Real Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) [21].

- Geometric Accuracy: This assesses the correctness of the ligand's internal chemical geometry, such as bond lengths and angles. The metrics used are the Root-Mean-Square-Deviation Z-scores for bond lengths (RMSZ-bond-length) and bond angles (RMSZ-bond-angle), which compare the ligand's geometry to high-quality small-molecule structures from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [21].

Composite Ranking Scores and 2D Plots

To simplify interpretation, RCSB PDB uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to aggregate these correlated metrics into two unidimensional composite indicators [21]:

- PC1-fitting: A composite indicator for how well the ligand model fits the electron density, explaining 84% of the variance in RSR and RSCC.

- PC1-geometry: A composite indicator for geometric accuracy, explaining 82% of the variance in RMSZ-bond-length and RMSZ-bond-angle.

These indicators are then converted into composite ranking scores—percentile ranks that indicate the quality of a specific ligand instance relative to all other ligand instances in the PDB archive. A score of 100% represents the best quality, 0% the worst, and 50% the median [21]. These scores are visually presented in a 2D ligand quality plot (found in the "Ligands" tab), where the X-axis represents the PC1-fitting ranking and the Y-axis the PC1-geometry ranking. The best instance of a ligand in a structure is marked with a green diamond, enabling its rapid identification [20] [21].

Experimental Protocol: Accessing and Interpreting Ligand Quality

- Access the Structure: Navigate to the RCSB.org website and enter a PDB ID (e.g., 7lad) in the search box [20].

- Locate Quality Indicators: On the Structure Summary page, find the 1D slider for "Ligands of Interest." This slider shows the goodness-of-fit for the best instance of each functional ligand [21].

- Open Detailed Ligand View: Click on the vertical bar for a specific ligand or select the "Ligands" tab to access the detailed ligand analysis page.

- Interpret the 2D Plot: In the "Ligands" tab, the first 2D plot shows the quality of all instances of the ligand in the current structure. Select the instance represented by the green diamond for the best combination of data fit and geometry [20].

- Visualize in 3D: Clicking on the green diamond symbol opens the 3D view in Mol*, displaying the ligand with its experimentally determined electron density map, allowing for direct visual assessment of the model's fit to the data [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Ligand-Binding Interactions

Once a high-quality ligand structure is identified, the next step is a quantitative analysis of its binding interactions. This involves examining the ligand's properties, its binding affinity, and the specific atomic contacts it forms with the binding site.

Identifying Ligands of Interest (LOI)

Not all ligands in a structure are the primary subject of the research. The RCSB PDB designates certain ligands as Ligands of Interest (LOI), which are functional ligands considered the focus of the experiment. The criteria for this designation are: (1) a molecular weight greater than 150 Da, and (2) the ligand is not on an exclusion list of likely non-functional molecules (e.g., solvents, salts) [20] [22]. On the RCSB website, LOIs are prominently featured in the ligand quality slider and tabs, helping researchers quickly identify the most relevant small molecules in a structure.

Binding Affinity and Quantitative Bioactivity Data

For many PDB structures, particularly those relevant to drug discovery, experimental measurements of binding strength, such as dissociation constants (Kd), inhibition constants (Ki), or half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50), are available. These data can be retrieved via the RCSB PDB interface or programmatically using tools like get_binding_affinity_by_pdb_id [24]. Integrating this quantitative bioactivity data with 3D structural information is powerful for establishing structure-activity relationships (SAR).

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Ligand and Binding Site Analysis

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity | Kd, Ki, IC50 | Quantitative measures of ligand binding strength or inhibitory potency. Lower Kd/Ki/IC50 indicates tighter binding. |

| Ligand Quality (Fit) | Real Space R-factor (RSR) | Measures agreement between model and electron density. Lower is better (closer to 0). |

| Real Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) | Measures correlation between model and electron density. Closer to 1.0 is ideal. | |

| Ligand Quality (Geometry) | RMSZ-Bond-Length | Z-score of deviation from ideal bond lengths. Closer to 0 is ideal, >2 may indicate problems. |

| RMSZ-Bond-Angle | Z-score of deviation from ideal bond angles. Closer to 0 is ideal, >2 may indicate problems. | |

| Composite Scores | PC1-fitting / PC1-geometry Rank | Percentile rank (0-100%) of ligand's fitting and geometry quality compared to all PDB ligands. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Binding Sites and Interactions

- Retrieve the Complex: From the Structure Summary page, open the 3D view of the macromolecular complex containing the validated ligand of interest.

- Isolate the Binding Site: Use the selection tools in the Mol* viewer to display only the ligand and the protein residues within a specific radius (e.g., 5 Å). This defines the binding pocket.

- Identify Non-Covalent Interactions: Leverage built-in analysis tools to detect and categorize specific interactions, such as:

- Hydrogen bonds: Between ligand donor/acceptors and protein side chains/backbone.

- Hydrophobic contacts: Between non-polar surfaces of the ligand and protein.

- Ionic interactions / Salt bridges: Between charged groups on the ligand and protein.

- Pi-Pi / Pi-cation stacking: Involving aromatic rings in the ligand or protein.

- Metal coordination: If the binding site contains metal ions.

- Document and Quantify: Measure distances and angles for key interactions to ensure they are within expected ranges (e.g., H-bond distances of 2.5-3.3 Å). This quantitative description forms the basis for understanding binding specificity and for structure-based drug design.

Successful analysis of PDB structures relies on a digital toolkit of defined reagents and resources. The following table details key "research reagents" available through the RCSB PDB that are essential for professional-level ligand and binding site analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PDB Analysis

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Analysis | Key Features / Components |

|---|---|---|

| wwPDB Chemical Component Dictionary (CCD) | Defines the chemical identity and ideal 3D structure of every small molecule ligand. | Chemical descriptors (SMILES, InChI), systematic names, idealized coordinates, stereochemistry. |

| BIRD (Biologically Interesting molecule Reference Dictionary) | Defines complex ligands (e.g., peptides, antibiotics) composed of multiple subcomponents. | Polymer sequence, connectivity, functional classification, natural source, external references (e.g., UniProt). |

| wwPDB Validation Report | Provides a quality "assay" for the structural model, including the ligand and its fit to experimental data. | Ligand geometry Z-scores, electron density fit metrics (RSR, RSCC), clash scores. |

| Mol* 3D Viewer | The primary visualization engine for interactive exploration of the 3D structure, binding site, and electron density. | Selection tools, measurement tools, support for displaying electron density maps, high-performance rendering. |

| RCSB PDB GraphQL API | Enables automated, programmatic querying and retrieval of structural data and metadata for high-throughput analysis. | Flexible queries, integration of PDB data with >40 external biodata resources. |

The RCSB PDB has evolved from a simple structural archive into a sophisticated platform for integrated structural bioinformatics. Its tools for automated binding site and ligand analysis—centered on robust validation, intuitive visualization, and programmatic access—empower researchers to move from static structures to dynamic, quantitative insights. The rigorous assessment of ligand structure quality ensures that analyses are built upon a reliable foundation, which is especially critical for applications in rational drug design and mechanistic biology.

Looking forward, the continued growth of the PDB archive, which contained over 245,000 structures as of 2025 [25], and the integration of new data types like Computed Structure Models (CSM) from AlphaFold DB [26], will further expand the scope of these analyses. The ongoing remediation of metalloprotein annotations [26] and the development of new validation metrics promise to make these tools even more powerful. By mastering the methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can confidently leverage the full power of the PDB to interpret crystallographic data and advance their scientific objectives.

Using Programmatic Access (Python API, GraphQL) for Bulk Data Analysis

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) represents a cornerstone resource in structural biology, containing over 199,000 experimentally determined structures as of 2025, with thousands more added annually [15]. While traditional manual access via the web interface serves casual browsing, large-scale analytical projects in crystallography research and drug development require efficient, programmatic data extraction methods. The RCSB PDB's comprehensive suite of application programming interfaces (APIs) provides researchers with direct computational access to the entire archive, enabling high-throughput analysis that would be impractical through manual approaches [27] [28].

These programmatic interfaces are particularly valuable for meta-analyses across multiple structures, such as investigating ligand-binding preferences, tracing evolutionary relationships through structural comparisons, or validating new computational methods against experimental data. By leveraging Python and GraphQL, scientists can extract precisely defined data subsets, transform them into analysis-ready formats, and integrate structural insights into automated research pipelines [28]. This technical guide explores the practical implementation of these tools for bulk data analysis within the context of crystallography research.

The RCSB PDB provides several specialized APIs that collectively enable comprehensive programmatic access to structural data and services. Understanding the distinct role of each interface is fundamental to designing efficient data acquisition strategies [27].

Core API Services

Table 1: Core RCSB PDB API Services for Programmatic Access

| API Service | Primary Function | Data Format | Use Case Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data API | Retrieves detailed information when structure identifiers are known | JSON | Fetch coordinates, annotations, and experimental details for specific entries |

| Search API | Finds identifiers matching specific search criteria using a JSON-based query language | JSON | Identify structures by resolution, organism, ligand presence, or sequence similarity |

| GraphQL API | Enables flexible, hierarchical data retrieval across multiple related data types in a single query | JSON | Extract specific fields from entries, entities, and assemblies simultaneously |

| ModelServer API | Provides access to molecular coordinate data in BinaryCIF format | BinaryCIF | Retrieve structural models at different granularities (assembly, chain, ligand) |

| Sequence API | Delivers alignments between structural and sequence databases | JSON | Map protein positional features between PDB, UniProt, and RefSeq |

The Data API serves as the foundational service for retrieving detailed information about known structures, organized according to the structural hierarchy (entry, entity, instance, assembly) [27]. The accompanying Search API exposes the full query capability of the RCSB portal programmatically, supporting complex Boolean logic across all available data fields [27] [28]. For large-scale extraction projects, the GraphQL API offers particularly significant advantages by allowing researchers to specify exactly which data fields they need from any level of the structural hierarchy in a single request, minimizing both network overhead and client-side data processing [27] [28].

Accessing Crystallographic Software and Tools

While the RCSB APIs provide access to structural data, the interpretation of crystallographic information often requires specialized software tools. The structural biology community relies on applications such as COOT for model building and refinement, PHENIX for automated structure determination, and CCP4 for comprehensive crystallographic analysis [29]. Additionally, tools like MolSoft ICM provide capabilities for evaluating crystallographic symmetry, generating biological units, and analyzing electron density maps, which are essential for proper structural interpretation [30]. These resources complement programmatic data access by enabling detailed structural analysis once relevant datasets have been identified and retrieved.

Python API for Efficient Data Retrieval

The RCSB provides a dedicated Python package (rcsb-api) that greatly simplifies interaction with their web services, handling technical concerns such as rate limiting, pagination, and error management automatically [28].

Searching for Structures Programmatically

The search API, accessible through the rcsbapi.search module, enables programmatic execution of sophisticated queries against the PDB archive. The following example demonstrates a typical search scenario:

This query identifies all protein structures deposited since the beginning of 2025, returning a set of PDB entry IDs that can be used for subsequent data retrieval operations [28]. The search framework supports a wide range of criteria, including experimental method, resolution, source organism, and the presence of specific ligands or cofactors.

Accessing Structure Data via REST and GraphQL

Once relevant structures have been identified, the Data API provides two distinct interfaces for retrieving detailed information. The REST API offers a straightforward approach for accessing specific data endpoints, while the GraphQL API enables more sophisticated, hierarchical queries [27] [28].

For specialized requirements not supported by the GraphQL interface, such as accessing administrative data about withdrawn entries, the REST API provides specific endpoints:

For most analytical applications, however, the GraphQL interface provides superior efficiency and flexibility. The rcsb-api package simplifies GraphQL queries through its DataQuery class:

This approach retrieves only the specified data fields (in this case, polymer entity IDs and canonical sequences) for all identified structures, with the library automatically handling request batching and rate limiting to comply with API guidelines [28].

GraphQL for Flexible Data Extraction

GraphQL represents a powerful paradigm for API design that enables clients to request exactly the data they need in a single operation. Unlike traditional REST APIs with fixed response structures, GraphQL allows researchers to specify both the data fields and their relationships, making it particularly well-suited for extracting complex information from the hierarchically organized PDB [27] [31].

GraphQL Schema Best Practices

Effective use of the RCSB GraphQL API requires understanding general GraphQL best practices. The schema follows a strongly typed system that ensures data consistency and predictability, with a hierarchical structure that mirrors the organization of structural data [31]. When designing queries:

- Use descriptive names for fields and types that clearly indicate their content and purpose

- Implement pagination for large datasets to avoid overwhelming server resources

- Leverage fragments to reuse common field sets and reduce query complexity

- Use custom scalars and enums for domain-specific data types when appropriate [31]

These practices result in more maintainable, efficient queries that are easier for both humans and machines to interpret. The RCSB provides an interactive GraphiQL interface that includes auto-completion and syntax highlighting, enabling researchers to explore the schema and build queries interactively before implementing them in code [28].

Designing Effective GraphQL Queries

A well-designed GraphQL query can extract precisely the information needed for analysis while minimizing data transfer and processing overhead. Consider this example that retrieves key metadata for structural analysis:

This query demonstrates the power of GraphQL to retrieve related data across multiple hierarchy levels in a single request: entry-level experimental details and crystallographic information, polymer entity sequences, and non-polymer entity chemical descriptions [27]. The ability to navigate these relationships without multiple round trips to the server makes GraphQL particularly efficient for bulk data extraction.

Bulk Operations and Large-Scale Data Analysis

For large-scale analytical projects involving thousands of structures, efficient data handling becomes paramount. The RCSB PDB APIs implement several mechanisms to support bulk operations while maintaining system stability and fair access for all users.

Managing Rate Limits and Performance

The RCSB PDB APIs implement rate limiting to prevent resource exhaustion and ensure equitable access. When these limits are exceeded, the service returns a 429 HTTP status code, indicating the need to reduce request frequency [27]. Effective strategies for managing these limits include:

- Implementing exponential backoff algorithms that gradually increase wait times between retries after encountering rate limits

- Adding deliberate pauses between requests in high-volume applications

- Using the automatic batching and rate limiting features provided by the

rcsb-apiPython package [28]

Additionally, researchers should be aware that when operating from shared IP addresses (common in university networks or VPNs), rate limits may be encountered earlier due to aggregated usage [27].

Workflow for Large-Scale Analysis

A robust workflow for bulk data analysis integrates multiple API services in a coordinated pipeline. The following diagram illustrates a recommended approach for large-scale structural bioinformatics projects:

Diagram 1: Bulk Data Analysis Workflow

This workflow begins with a precisely defined research question, which informs the construction of targeted search queries. After retrieving initial candidate sets, researchers apply additional filters before using GraphQL to extract detailed information specifically relevant to the analysis. The subsequent processing, analysis, and visualization stages typically employ specialized scientific computing libraries in Python or R.

Data Processing and Integration

After retrieving structural data through the APIs, researchers typically need to process and integrate this information with other data sources for comprehensive analysis. The Python ecosystem offers powerful tools for this stage:

This approach transforms the nested JSON response from the GraphQL API into a tabular format suitable for statistical analysis, visualization, or integration with other biological datasets [28].

Practical Applications in Crystallography Research

The programmatic access methods described in this guide enable a wide range of practical applications in crystallography research and drug development.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Structural Bioinformatics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB APIs | Programmatic data access | Bulk retrieval of structural data and annotations |

| BioPython | Biological computation | PDB file parsing and molecular analysis |

| COOT | Model building and validation | Electron density interpretation and structure refinement |

| PHENIX | Automated structure determination | X-ray crystallography structure solution |

| CCP4 Suite | Comprehensive crystallographic analysis | Data processing, structure solution, and refinement |

| MolSoft ICM | Crystallographic analysis | Symmetry operations and biological unit generation |

| Pandas | Data manipulation | Transformation and analysis of retrieved structural data |

| Matplotlib/Plotly | Data visualization | Creation of publication-quality figures and interactive plots |

These tools collectively support the entire workflow from structure determination to analysis and visualization. The programmatic access provided by the RCSB PDB APIs integrates with this ecosystem, enabling researchers to move seamlessly from data retrieval to specialized analysis [29] [30].

Example Research Applications

Programmatic access to the PDB enables several powerful research applications:

- Structural Genomics: Large-scale comparison of protein folds and families across entire organisms

- Drug Discovery: Analysis of ligand-binding sites across related protein targets to inform inhibitor design

- Method Validation: Benchmarking new computational methods against experimental structural data

- Evolutionary Studies: Tracing structural adaptations through comparison of homologous proteins

For example, a researcher investigating metalloprotein function could combine search operations to identify structures containing specific metal ions with GraphQL queries to retrieve coordination geometry and surrounding residue information, enabling statistical analysis of metal-binding environments across thousands of structures.