Biomolecular Condensates and Protein Aggregates in Human Disease: From Basic Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of biomolecular condensates and protein aggregates, highlighting their dual roles in physiological processes and disease pathogenesis.

Biomolecular Condensates and Protein Aggregates in Human Disease: From Basic Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of biomolecular condensates and protein aggregates, highlighting their dual roles in physiological processes and disease pathogenesis. It covers the fundamental biophysical principles of phase separation and aggregation, current methodological approaches for detection and analysis, strategies for troubleshooting dysregulated condensates, and comparative validation of disease models. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes recent advances in understanding how condensate dysfunction contributes to neurodegeneration, cancer, and other proteinopathies, while examining emerging therapeutic opportunities targeting these assemblies.

The Biophysical Principles: From Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation to Pathological Aggregation

The classical view of cellular organization, centered on membrane-bound organelles, has been fundamentally reshaped by the discovery and characterization of biomolecular condensates. These membraneless compartments concentrate specific proteins and nucleic acids without the physical barrier of a lipid bilayer, forming through a process of phase separation [1]. Biomolecular condensates represent a universal mechanism of intracellular organization, with approximately 30 distinct types identified as of 2022, outnumbering the dozen or so known traditional membrane-bound organelles [1]. This technical guide examines the core principles defining biomolecular condensates, their physical mechanisms, research methodologies, and their profound implications in protein aggregation diseases, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding this rapidly advancing field.

The discovery of condensates has challenged long-held beliefs in biochemistry, particularly the dogma that protein structure strictly determines function. Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or regions (IDRs), which lack a defined three-dimensional structure, play crucial roles in condensate formation [1]. Furthermore, the presence of biomolecular condensates in bacterial cells contradicts the traditional definition of prokaryotes as lacking organelles, revealing unexpected complexity in these organisms [1].

Historical Context and Defining Characteristics

Historical Evolution of Condensate Biology

The conceptual foundations for biomolecular condensates emerged over centuries, though the terminology has evolved significantly:

- 1858: Carl Nägeli's micellar theory described starch granules as molecular aggregates [2].

- Late 19th Century: William Bate Hardy and Edmund Beecher Wilson described cytoplasm as a colloid, while Thomas Harrison Montgomery Jr. documented nucleolus morphology [2].

- 1924/1929: Alexander Oparin and J.B.S. Haldane proposed their "primordial soup" theory, suggesting life originated from colloidal organic substances [2].

- Mid-2000s: Researchers established that some organelles function without membranes [1].

- Since 2009: Extensive evidence has demonstrated intracellular phase transitions across numerous biological contexts [2].

The term "biomolecular condensate" was deliberately introduced to encompass the breadth of membrane-less assemblies in cells, emphasizing their ability to concentrate biomolecules and connecting to concepts in condensed matter physics [2] [3].

Key Characteristics and Classification

Biomolecular condensates are defined by several key characteristics that distinguish them from traditional organelles and stoichiometric complexes:

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Biomolecular Condensates

| Feature | Description | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane-less | No lipid bilayer boundary | Permeable interface allowing selective molecular exchange |

| Liquid-like Properties | Fusion, fission, rapid component exchange [3] | Dynamic responsiveness to cellular conditions |

| Formation Mechanism | Phase separation coupled with percolation [4] | Concentration-dependent assembly above saturation threshold |

| Molecular Composition | Multivalent proteins and/or nucleic acids [3] | Scaffold-client organization with selective partitioning |

| Material States | Spectrum from liquid-like to gel-like to solid-like [5] | Functional adaptability with pathological potential |

Biomolecular condensates can be categorized by their cellular localization and composition:

- Cytoplasmic Condensates: Stress granules, P-bodies, germline P-granules [2]

- Nuclear Condensates: Nucleoli, Cajal bodies, nuclear speckles, heterochromatin [2] [3]

- Membrane-Associated Condensates: Signaling clusters at synapses [2]

- Extracellular Condensates: Milk casein micelles [2]

Physical Principles and Formation Mechanisms

Thermodynamic Framework of Phase Separation

Biomolecular condensates form through phase separation when biomolecules reach their solubility limit, creating a system that minimizes free energy by separating into dilute and dense phases [3]. This process is governed by classical thermodynamics where the free energy of the solution becomes multimodal when solute molecules interact favorably, leading to phase separation at the concentration where macromolecule-macromolecule interactions overcome the entropic tendency toward homogeneous distribution [3].

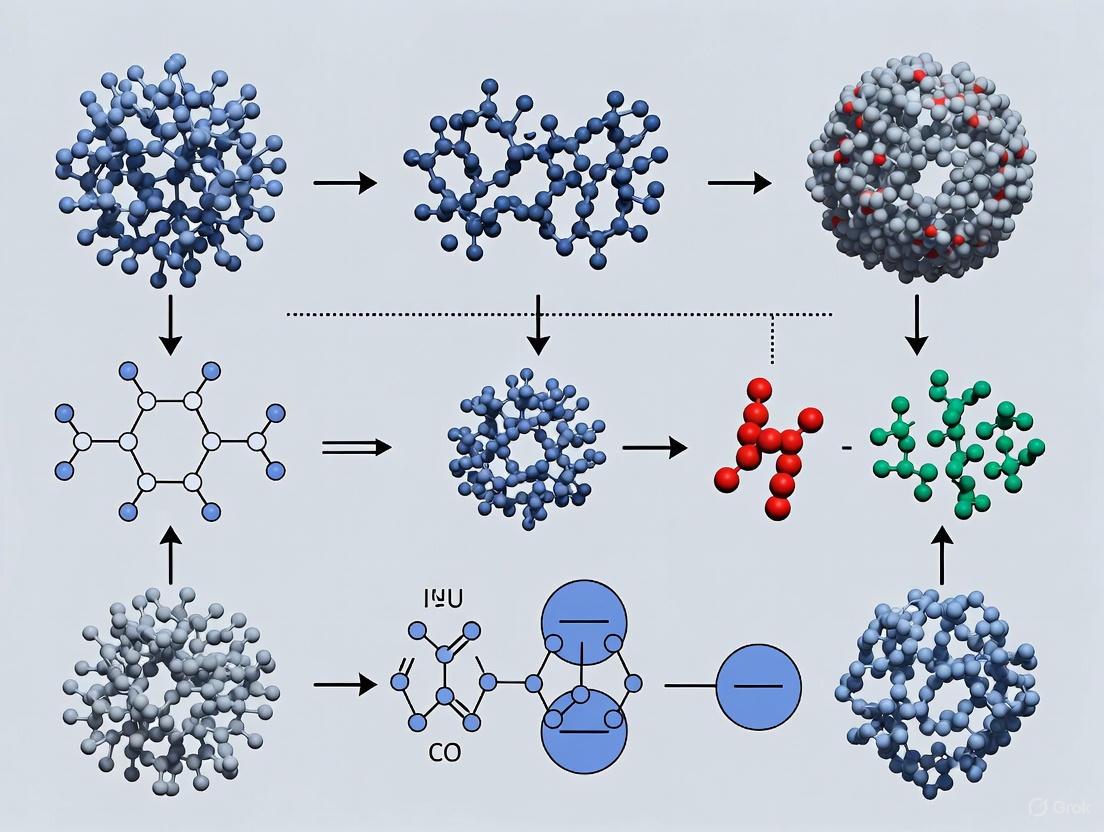

The following diagram illustrates the organizational role of biomolecular condensates and their relationship with disease processes:

Diagram: Cellular functionality and disease implications of biomolecular condensates are determined by their proper regulation. Dysregulation is implicated in serious conditions including neurodegeneration and cancer [6].

Molecular Drivers of Condensate Formation

Multivalency—the presence of multiple interacting elements within biomolecules—serves as the primary molecular driver of condensate formation [3]. Key mechanisms include:

- Stickers and Spacers Model: Proteins contain motifs with strong interaction potentials (stickers) separated by motifs with weak interaction potentials (spacers) that dictate saturation concentration [7].

- Intrinsically Disordered Regions: IDPs and IDRs enable dynamic, multivalent interactions through domains lacking stable structure [7].

- Sequence-Encoded Features: The distribution of charged residues and aromatic residues significantly influences phase behavior [4].

- Multicomponent Interactions: Condensates often contain dozens of components that determine functional identity through specific stoichiometries [8].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Characterization Techniques

Research in biomolecular condensates employs multidisciplinary approaches spanning cell biology, biophysics, and biochemistry. The table below summarizes key experimental methods:

Table 2: Essential Methodologies for Condensate Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications and Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging & Microscopy | Confocal, FRAP, QPI [8], Super-resolution [5], DIC [4] | Morphology, dynamics, fusion/fission events, molecular mobility, concentration measurements |

| Biophysical Analysis | FCS, Single-particle tracking, Optical tweezers, AFM [7] | Diffusion coefficients, material properties, viscoelasticity, molecular interactions |

| Biochemical Assays | Sedimentation assays, Turbidity, Filter trap assay [7] | Phase boundaries, saturation concentrations, solubility limits |

| Genetic Manipulation | Knockdown/knockout, Endogenous tagging, Mutational analysis [5] | Functional assessment, concentration dependence, domain requirements |

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Condensate Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| 1,6-Hexanediol | Disrupts weak hydrophobic interactions [7] | Differentiating liquid-like (sensitive) from gel-like (resistant) condensates |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Macromolecular crowding agent [7] [4] | Mimicking cellular crowding to study phase behavior in vitro |

| Fluorescent Tags | Protein localization and dynamics [5] | Live-cell imaging, FRAP, single-particle tracking (e.g., mEGFP [4]) |

| SynIDPs | Programmable condensate engineering [4] | Designing synthetic condensates with tailored properties for cellular control |

| Chemical Chaperones | Modifying condensate properties [6] | Regulating phase separation (e.g., DNAJB6b, Hsp104 [7]) |

Experimental Workflow for Condensate Characterization

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for characterizing biomolecular condensates:

Diagram: A multi-stage experimental workflow progresses from initial observation to functional assessment, integrating in vitro and cellular validation [7] [5] [8].

Biomolecular Condensates in Disease and Therapeutic Development

Condensates in Protein Aggregation Diseases

Biomolecular condensates provide a crucial framework for understanding the pathogenesis of protein aggregation diseases. The transition from functional condensates to pathological aggregates represents a continuum where dysregulation of phase separation can drive disease [6]. Key mechanisms include:

- Aging and Solidification: Liquid-like condensates can progressively mature into gel-like or solid-like states, as observed in FUS and hnRNPA1 in ALS [6].

- Loss of Homeostasis: Age-related decline in protein quality control allows accumulation of aberrant condensates [6].

- Cellular Stress: Various stressors promote formation of stress granules that can undergo pathogenic transformation [6].

The material properties of condensates exist on a spectrum with significant implications for cellular function and disease:

Table 4: Material Properties Spectrum of Biomolecular Condensates

| Property | Liquid-like | Gel-like | Solid-like/Aggregates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mobility | High (rapid exchange) [7] | Reduced mobility [7] | Immobile [7] |

| Fusion/Fission | Observed [7] | Not observed [7] | Not observed [7] |

| 1,6-HD Sensitivity | Sensitive [7] | Resistant [7] | Resistant [7] |

| SDS Solubility | Soluble [7] | Soluble [7] | Insoluble [7] |

| Visual Appearance | Spherical, high circularity [7] | Irregular shape, lower circularity [7] | Fibrous, highly irregular [7] |

Therapeutic Implications and Intervention Strategies

Understanding condensate pathology opens promising avenues for therapeutic intervention:

- Small Molecule Modulators: Compounds that promote or dissolve pathological condensates [1] [6].

- Chaperone-Based Therapies: Enhancing cellular quality control mechanisms to prevent aberrant phase transitions [7] [6].

- Regulation of Post-Translational Modifications: Targeting modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, arginine methylation) that influence phase behavior [6].

- Synthetic Condensate Engineering: Designing programmable condensates for synthetic biology applications [4].

Biomolecular condensates represent a fundamental principle of cellular organization that transcends traditional boundaries of cell biology, biophysics, and biochemistry. Their discovery has provided transformative insights into cellular compartmentalization and unveiled new pathomechanisms in human disease. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the principles defining biomolecular condensates is essential for advancing both basic science and therapeutic innovation.

Future research directions include establishing standardized criteria for identifying phase-separated compartments in cells, developing more sophisticated tools for quantifying condensate composition and material properties, and creating targeted therapeutic strategies that specifically modulate pathological phase transitions without disrupting physiological condensate functions. As our knowledge of biomolecular condensates continues to evolve, it will undoubtedly reveal new opportunities for understanding and treating some of the most challenging protein aggregation diseases.

Biomolecular condensates are membraneless intracellular assemblies that form via liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) and organize cellular biochemistry by concentrating specific proteins and nucleic acids [6]. These condensates play fundamental roles in diverse cellular processes, including gene expression, stress response, metabolic homeostasis, and chromosome organization [6] [9]. The material properties of biomolecular condensates range from liquid-like to gel-like or solid-like states, with transitions between these states implicated in both physiological function and disease pathology [6].

The formation and dissolution of biomolecular condensates are tightly regulated in healthy cells. However, aging-related loss of proteostasis and environmental stressors can disrupt this regulation, leading to the formation of aberrant, disease-causing condensates [6] [10]. In neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia, mutations in RNA-binding proteins can cause liquid condensates to undergo pathogenic liquid-to-solid transitions, resulting in persistent, toxic aggregates [6] [11]. Understanding the molecular drivers of phase separation—particularly multivalent interactions and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs)—provides crucial insights for developing therapeutic strategies targeting protein aggregation diseases.

Molecular Principles of Phase Separation

The Stickers-and-Spacers Framework

The formation of biomolecular condensates is governed by the stickers-and-spacers framework, which describes how specific residues, termed "stickers," drive strong, specific interactions, while "spacer" regions act as flexible linkers with minimal nonspecific interactions [12]. Stickers typically include aromatic residues like tyrosine (Y), tryptophan (W), and phenylalanine (F) that mediate π-π stacking, cation-π, and electrostatic interactions [12]. Spacers, often composed of alanine (A), glycine (G), and proline (P), provide flexibility and control the spatial organization of stickers [12].

Evolutionary analysis reveals that both stickers and spacers in IDRs can be conserved, suggesting that entire motifs rather than isolated residues function as units under evolutionary selection to support stable membraneless organelle formation [12]. This conservation indicates the functional importance of maintaining precise phase separation behavior for cellular fitness.

Table 1: Key Sticker and Spacer Residues in Phase Separation

| Category | Amino Acids | Interaction Types | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stickers | Y, W, F (Tyrosine, Tryptophan, Phenylalanine) | π-π stacking, cation-π, electrostatic | Drive specific, strong interactions leading to network formation |

| Spacers | A, G, P (Alanine, Glycine, Proline) | Provide flexibility, control distance | Modulate connectivity between stickers, control material properties |

| Other Conserved Residues | Various polar and charged residues | Electrostatic, hydrogen bonding | Fine-tune phase behavior, respond to environmental cues |

Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

IDRs are protein segments that lack well-defined tertiary structures yet play essential roles as scaffolds in biomolecular condensates [12] [11]. Unlike folded domains with fixed three-dimensional structures, IDRs remain flexible, enabling them to facilitate multivalent interactions through their stickers [9]. The flexibility of IDRs allows for dynamic assembly and disassembly of condensates in response to cellular signals.

Mutations in IDRs can disrupt multivalent interaction networks, altering phase behavior and contributing to various diseases [12]. For example, in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), mutations in the IDRs of RNA-binding proteins like FUS and hnRNPA1 cause liquid droplets to age into solid-like states with pathological fibrillization [6] [11]. St. Jude researchers discovered that the IDR of hnRNPA1 contains small but frequent amino acid sequences that repeat, causing the IDRs to stick together in fleeting interactions [11]. At high enough concentrations, these interactions drive phase separation, but disease-associated mutations make these interactions unrelentingly interwoven, leading to persistent condensates [11].

Figure 1: Molecular Grammar of IDRs. Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) contain specific "sticker" residues that drive interactions and "spacer" residues that provide flexibility. Through weak, multivalent interactions between stickers, IDRs drive the formation of biomolecular condensates.

Multivalent Interactions

Multivalency refers to the presence of multiple interaction sites within a single molecule or complex, enabling the formation of extensive networks through cumulative weak interactions [13]. In biomolecular condensates, multivalency arises through several mechanisms:

Multi-domain proteins with well-defined folded domains connected by disordered linkers can undergo phase separation through modular domain interactions [9] [13].

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) lacking well-defined three-dimensional structures utilize multiple interaction motifs within their sequences to form multivalent networks [9].

Oligomerization of proteins amplifies their valency. For example, endophilin exists as a homodimer in solution, and this bivalency can be further amplified through oligomerization after membrane binding [13].

A classic example of multivalency-driven phase separation occurs in fast endophilin-mediated endocytosis (FEME), where endophilin's SH3 domains interact with multiple proline-rich motifs (PRMs) in the third intracellular loop (TIL) of β1-adrenergic receptors and the C-terminal domain of lamellipodin (LPD) [13]. These multivalent interactions drive the formation of liquid-like condensates that facilitate the assembly of endocytic machinery.

Phase Separation in Disease Pathology

Neurodegenerative Diseases

In neurological diseases, mutations in IDRs of RNA-binding proteins disrupt the dynamics of biomolecular condensates such as stress granules [11]. Normally, stress granules reversibly assemble in response to cellular stress and dissolve once the stress subsides. However, disease-associated mutations in proteins like hnRNPA1 cause persistent stress granules that undergo liquid-to-solid transitions, leading to pathological protein aggregates [11].

J. Paul Taylor's research at St. Jude revealed that the hnRNPA1 protein contains repeating amino acid sequences in its IDR that facilitate transient interactions [11]. At high concentrations, these interactions drive phase separation, but disease mutations cause the proteins to become "unrelentingly interwoven," preventing normal dissolution [11]. This mechanism illustrates how disrupted phase dynamics contribute to neurodegenerative pathology.

Table 2: Phase Separation in Disease Pathology

| Disease Context | Key Proteins | Phase Transition | Pathological Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALS/FTD | FUS, hnRNPA1, TDP-43 | Liquid-to-solid transition | Persistent stress granules, toxic aggregates |

| Alzheimer's Disease | Aβ, tau | Aggregation via LLPS | Amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles |

| Cancer | Multiple regulatory proteins | Aberrant condensate formation | Dysregulated transcription, signaling |

| Hypoxia-related Diseases | Multiple proteins with disrupted folding | Condensate aging to aggregates | Cellular dysfunction in CVD, stroke, cancer |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | hnRNPH2, other RBPs | Disrupted biomolecular organization | Altered neural development, epilepsy |

Cellular Stress and Aging

Aging-associated decline in protein quality control and chronic cellular stress promote the transition from functional condensates to pathological aggregates [6] [10]. Hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) represents a particularly important environmental stressor that disrupts protein homeostasis through multiple mechanisms:

ATP depletion inactivates ATP-dependent molecular chaperones like Hsp70 and Hsp90, reducing protein-folding capacity [10].

Impaired disulfide bond formation due to oxygen limitation disrupts oxidative protein folding, leading to protein misfolding [10].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) elevation under hypoxic conditions promotes protein damage and aggregation [10].

Hypoxia-induced disruption of protein homeostasis contributes to various pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disease, hypoxic brain injury, and cancer [10]. In these conditions, hypoxia induces a shift in macromolecular assemblage from a liquid to a solid phase, with ATP depletion and inactivation of multiple protein chaperones playing central roles [10].

Experimental Methods for Studying Phase Separation

Quantitative Imaging Techniques

Dual-Color Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy (dcFCCS)

dcFCCS detects and quantifies condensates at the nanoscale, beyond the diffraction limit of conventional light microscopy (~200 nm) [14]. This method enables researchers to measure condensate size, growth rate, molecular stoichiometry, and the binding affinity of client molecules within condensates [14].

Protocol Overview:

- Label two different protein components with spectrally distinct fluorophores.

- Measure fluorescence fluctuations as molecules diffuse through a confocal volume.

- Analyze cross-correlation between the two channels to determine co-diffusing complexes.

- Quantify molecular interactions and cluster sizes through correlation analysis.

Color-Multiplexed Differential Phase Contrast (cDPC) Microscopy

cDPC is a single-shot quantitative phase imaging technique that recovers both amplitude and phase information from biological samples without requiring labels or stains [15]. The method uses a standard brightfield microscope with a modified condenser containing a static multi-color filter to create asymmetric illumination patterns encoded in different color channels [15].

Protocol Overview:

- Install a custom 3D-printed color filter insert in the condenser turret.

- Capture a single color image with multiplexed illumination patterns.

- Separate the image into RGB components and calibrate for cross-talk.

- Reconstruct quantitative phase through deconvolution algorithms.

- Synthesize DIC and phase contrast images digitally from quantitative phase data.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflows for Phase Separation Studies. Two complementary approaches for studying biomolecular condensates: dcFCCS (left) uses dual-color labeling to quantify nanoscale properties, while cDPC microscopy (right) uses computational imaging to achieve label-free quantitative phase imaging.

In Vitro Reconstitution Assays

In vitro reconstitution allows controlled investigation of specific molecular interactions driving phase separation. The FEME pathway study provides an excellent example of a comprehensive in vitro approach [13]:

Protocol for Studying Endophilin Phase Separation:

Protein Purification: Express and purify endophilin A1 and its binding partners (LPD C-terminal domain, β1-AR TIL peptide).

Droplet Formation Assay:

- Mix proteins in physiological buffer (25-50 mM HEPES, 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4).

- Add molecular crowding agent (PEG 8000) at 2.5-10% (w/v) to mimic cellular environment.

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-30 minutes.

Characterization:

- Image droplets using transmitted light and fluorescence microscopy.

- Assess liquid properties via fusion events and wetting behavior.

- Measure internal dynamics using FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching).

- Determine phase boundaries by varying protein and PEG concentrations.

Membrane Assays:

- Reconstitute supported lipid bilayers with incorporated TIL or LPD.

- Monitor 2D phase separation and cluster formation by endophilin.

- Analyze membrane curvature generation using electron microscopy.

Computational Approaches

Protein Language Models

The Evolutionary Scale Model (ESM2) analyzes evolutionary constraints on IDRs by predicting residue-level mutational tolerance [12]. This method is particularly valuable for disordered regions where traditional sequence alignment is challenging.

Workflow:

- Curate dataset of human proteins with disordered regions (e.g., 939 MLO-associated proteins).

- Process sequences through ESM2 to generate mutational landscapes.

- Identify conserved residues with high mutation resistance.

- Validate conservation through multi-sequence alignment when possible.

- Correlate conserved motifs with phase separation propensity and disease mutations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Phase Separation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Agents | PEG 8000, Ficoll, dextran | Mimic intracellular crowded environment, lower phase separation threshold |

| Fluorescent Labels | Alexa Fluor 488, 594; GFP/RFP variants | Label proteins for visualization, FRAP, and interaction studies |

| Molecular Chaperones | Hsp70, Hsp90, Hsp40, Hsp27 | Investigate proteostasis network regulation of condensate dynamics |

| Lipid Systems | Supported lipid bilayers, liposomes | Study membrane-associated phase separation and curvature generation |

| Phase Separation Inducers | Specific peptides (e.g., β1-AR TIL), RNA molecules | Trigger condensate formation in reconstitution assays |

| Inhibitors | 1,6-hexanediol, targeted compounds | Dissolve condensates, probe material properties, therapeutic exploration |

| Protein Expression Systems | E. coli, insect cells, mammalian cells | Produce recombinant proteins for in vitro studies |

| Microscopy Tools | cDPC filters, confocal systems, TIRF | Visualize and quantify condensates across spatial scales |

Therapeutic Targeting of Aberrant Phase Separation

The understanding of molecular drivers of phase separation opens new therapeutic avenues for protein aggregation diseases. Several targeting strategies are emerging:

Small molecule modulators that specifically disrupt pathological condensates without affecting physiological phase separation [11]. St. Jude researchers have demonstrated proof-of-concept by targeting central nodes of stress granules, showing that dissolving pathological condensates can affect disease pathology [11].

Stabilizing functional condensates that may be disrupted in disease, rather than only inhibiting pathological aggregation.

Enhancing protein quality control mechanisms to prevent the aging of liquid condensates into solid aggregates, particularly in age-related diseases [6] [10].

The rapid translational approach being developed at St. Jude aims to "go from the nomination of a mutation to the delivery of a therapy in about two years," with goals to reduce this timeline further [11]. This accelerated pathway offers hope for treating previously "undruggable" neurological diseases by targeting biomolecular condensates.

Molecular drivers of phase separation—multivalent interactions and intrinsically disordered regions—represent fundamental organizational principles in cell biology with profound implications for understanding and treating protein aggregation diseases. The stickers-and-spacers framework provides a conceptual model for understanding how specific sequence features encode phase behavior, while evolutionary analysis reveals conservation patterns that reflect functional constraints. Experimental methods from quantitative microscopy to in vitro reconstitution and computational modeling enable detailed investigation of condensate formation and regulation. As research continues to elucidate the relationship between condensate pathology and human disease, targeting aberrant phase separation offers promising therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and other conditions linked to disrupted biomolecular organization.

The aggregation of proteins into higher-order assemblies represents a fundamental process in cell biology with profound implications for health and disease. Historically characterized as a purely pathological phenomenon, protein aggregation is now understood to occur along a dynamic continuum, encompassing functional, physiological processes and dysfunctional, disease-associated states. This continuum includes functional amyloids that support essential biological processes, dynamic biomolecular condensates such as stress granules that organize cellular biochemistry, and pathological fibrils that characterize neurodegenerative diseases. The precise molecular mechanisms that govern transitions between these states—particularly the conversion of dynamic condensates into persistent pathological aggregates—represent a frontier in molecular cell biology and therapeutic development. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for elucidating the pathogenesis of conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Alzheimer's disease, and for developing targeted interventions [16] [17].

Central to this understanding is the concept of liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), a physicochemical process that enables specific proteins and nucleic acids to form membrane-less organelles with liquid-like properties. These biomolecular condensates, including stress granules, serve as organizing centers that concentrate specific macromolecules to regulate cellular processes ranging from RNA metabolism to stress response. Emerging evidence indicates that the same molecular interactions that drive functional phase separation can also nucleate the formation of pathological protein aggregates, suggesting that the aggregation continuum is underpinned by shared biophysical principles [18] [16]. This whitepaper examines the key transitions along this continuum, with a focus on the structural features, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental approaches that define functional amyloids, stress granules, and pathological fibrils within the context of disease research and drug development.

The Aggregation Spectrum: From Function to Dysfunction

Functional Amyloids

Functional amyloids are protein aggregates with cross-β-sheet quaternary structures that serve essential physiological roles across diverse biological systems. Unlike their pathological counterparts, the formation and turnover of functional amyloids are tightly regulated processes. These structures exhibit remarkable stability, attributable to their core architecture of β-strands arranged perpendicularly to the fibril axis. This configuration creates a distinctive "cross-β" pattern observable in X-ray diffraction experiments, which represents a structural hallmark shared by all amyloid forms [19]. Functional amyloids participate in various biological processes, including bacterial biofilm formation, fungal reproduction, and the regulation of mammalian metabolic pathways. Their controlled assembly and disassembly demonstrate that the amyloid state can be harnessed for beneficial cellular functions without inducing toxicity [17].

The biological utility of functional amyloids stems from their unique material properties, which include high stability, resistance to proteolysis, and capacity for self-assembly. In mammalian systems, one prominent example of physiological amyloid is found in amyloid bodies (A-bodies). These are stress-inducible, nuclear structures that sequester a diverse array of cellular proteins in an amyloid-like state during conditions of proteotoxic, heat, or hypoxic stress. A-bodies share several biophysical characteristics with pathological aggregates, including detergent insolubility, proteinase K resistance, and affinity for amyloid-specific dyes such as Congo red and Thioflavin S. However, unlike pathological aggregates, A-body formation is a rapid and reversible process that does not culminate in cytotoxicity. This controlled physiological aggregation facilitates cellular survival under stressful conditions, potentially by temporarily immobilizing proteins and conserving resources [17]. The existence of such structures underscores the evolutionary conservation of amyloidogenesis as a functional principle rather than solely a pathological endpoint.

Biomolecular Condensates and Stress Granules

Biomolecular condensates are membrane-less organelles that form through LLPS, creating discrete cellular compartments with distinct compositions and functions. Among these, stress granules (SGs) have garnered significant attention in disease research due to their intimate connection with neurodegenerative pathologies. SGs are dynamic assemblies composed of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and non-translating mRNAs that nucleate in response to various cellular stresses, such as oxidative damage, heat shock, and osmotic stress. Their primary function is to regulate mRNA metabolism by transiently storing translationally arrested transcripts, thereby conserving energy and protecting the transcriptome during adverse conditions. This process can be likened to a ship lowering its sails during a storm, temporarily halting resource-intensive processes until favorable conditions resume [20] [21].

The formation and dissolution of SGs are highly regulated processes governed by multivalent interactions between specific protein domains, particularly low-complexity domains (LCDs) that facilitate phase separation. Key SG components include heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) such as hnRNPA1, TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), and fused in sarcoma (FUS) protein. Under normal conditions, these proteins exhibit dynamic shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm. During stress, their LCDs drive LLPS through transient, weak interactions that lead to the formation of liquid-like droplets. These droplets can mature over time, transitioning from liquid to gel-like states, and under certain circumstances, to solid aggregates. The dynamic nature of normal SGs is evidenced by their rapid disassembly following stress removal, a process crucial for restoring cellular homeostasis and preventing the persistence of condensed states that might nucleate pathological aggregation [18] [20].

Pathological Fibrils

Pathological fibrils represent the aberrant endpoint of the aggregation continuum, characterized by the irreversible accumulation of proteins into amyloid-like structures that disrupt cellular function and viability. These fibrils are the defining histopathological features of numerous neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS, FTD, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. While pathological fibrils share the cross-β structural motif with functional amyloids, they differ critically in their regulation, persistence, and cellular impacts. The formation of pathological fibrils typically occurs through a nucleation-dependent polymerization mechanism, wherein the rate-limiting step involves the formation of a stable oligomeric nucleus that subsequently templates the rapid addition of monomeric subunits into elongated, β-sheet-rich filaments [22] [17].

Multiple factors can drive the conversion from functional condensates to pathological aggregates. Disease-associated mutations in genes encoding SG proteins, such as hnRNPA1, TDP-43, and FUS, diminish the metastability of condensates by enhancing the propensity of their LCDs to undergo liquid-to-solid phase transitions. Environmental stressors, including hypoxia and oxidative stress, further promote this transition by disrupting protein homeostasis networks. Specifically, hypoxic conditions impair ATP-dependent chaperone function and disrupt disulfide bond formation, leading to widespread protein misfolding and aggregation [10]. The resulting pathological fibrils exhibit remarkable structural diversity (polymorphism), which may contribute to the heterogeneity in disease presentation and progression observed across patients. Critically, these fibrils accumulate in affected tissues, forming insoluble deposits that co-opt essential cellular components, disrupt membrane integrity, and ultimately trigger cytotoxic cascades responsible for neuronal degeneration [10] [19].

Table 1: Key Characteristics Across the Aggregation Continuum

| Feature | Functional Amyloids | Stress Granules | Pathological Fibrils |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Role | Physiological functions (e.g., bacterial biofilms, A-bodies) | Dynamic stress response, mRNA regulation | Disease pathogenesis, cytotoxicity |

| Formation Trigger | Regulated developmental or environmental signals | Cellular stress (heat, oxidative, osmotic) | Mutations, chronic stress, aging |

| Reversibility | Tightly regulated assembly/disassembly | Rapid disassembly after stress relief | Irreversible without intervention |

| Molecular Structure | Cross-β-sheet core | Multivalent, liquid-like condensates | Cross-β-sheet with polymorphic variations |

| Cellular Location | Cell membrane, nucleus (A-bodies) | Cytoplasm, peri-nuclear regions | Intracellular inclusions, extracellular plaques |

| Representative Proteins | Curli, Sup35, A-body constituents | hnRNPA1, TDP-43, FUS, TIA1 | Aβ, α-synuclein, mutant SOD1 |

Molecular Drivers of the Functional-to-Pathological Transition

The transition from functional, dynamic condensates to pathological, solid aggregates represents a critical juncture in protein aggregation diseases. Understanding the molecular drivers of this transition provides insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions. Several key factors influence this pathological conversion, including mutations in protein sequences, alterations in the cellular environment, and disruptions in protein quality control systems.

Mutations in genes encoding RNA-binding proteins constitute a major driver of aberrant phase transitions. For example, mutations in the low-complexity domains of hnRNPA1, TDP-43, and FUS proteins are linked to familial forms of ALS and FTD. These mutations typically enhance the intrinsic aggregation propensity of the proteins by promoting stronger intermolecular interactions that favor β-sheet formation over dynamic, liquid-like interactions. Research demonstrates that disease-linked mutations in hnRNPA1 diminish the metastability of condensates, thereby accelerating the formation of fibrils as proteins are driven out of the condensate interior [20] [21]. Similarly, mutations in TDP-43 disrupt the α-helical structure in its low-complexity C-terminal domain, impairing normal phase separation and promoting pathological aggregation [16].

Environmental stressors significantly contribute to the functional-to-pathological transition by disrupting cellular homeostasis. Hypoxia, or oxygen deprivation, represents one such stressor that promotes protein aggregation through multiple mechanisms. Hypoxic conditions lead to ATP depletion, which in turn impairs the function of ATP-dependent molecular chaperones such as Hsp70 and Hsp90. These chaperones normally prevent aberrant protein aggregation by facilitating proper folding and disaggregation; their inactivation under hypoxic stress allows misfolded proteins to accumulate [10]. Additionally, hypoxia disrupts oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum by limiting disulfide bond formation, further contributing to proteostatic collapse. The resulting accumulation of misfolded proteins can overwhelm degradation pathways, leading to the consolidation of pathological fibrils [10].

The physical and chemical microenvironment within biomolecular condensates can also influence aggregation pathways. Concentrating specific proteins within condensates increases their local concentration, potentially accelerating nucleation events. Furthermore, the unique chemical milieu within condensates—characterized by distinct pH, viscosity, and dielectric properties—can alter the energy landscape of protein folding and aggregation reactions. Recent evidence suggests that while condensate interiors can sometimes suppress fibril formation, their surfaces can act as platforms for nucleation, particularly for amyloid fibrils that eventually incorporate proteins from the external environment [20]. This nuanced understanding reconciles the seemingly contradictory observations of condensates functioning as both protective sinks and potential nucleation sites in different contexts.

Table 2: Factors Driving Pathological Transition and Experimental Evidence

| Driver | Molecular Mechanism | Experimental Evidence | Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Mutations | Enhanced intermolecular β-sheet interactions in LCDs | Disease-linked hnRNPA1 mutations reduce condensate metastability, favor fibril formation [20] | ALS, FTD, Multisystem Proteinopathy |

| Environmental Stress (Hypoxia) | ATP depletion, chaperone inactivation, disrupted disulfide bonding | Reduced Hsp70/90 expression, increased insolubility of specific proteins in nematodes [10] | Alzheimer's disease, Cardiovascular disease |

| Oxidative Stress | ROS production, protein carbonylation, aggregation | Increased oligomeric Aβ binding to ROS in cerebral hypoperfusion [10] | Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease |

| Aging | Declining proteostasis network efficiency | Impaired autophagy, reduced chaperone expression, accumulation of damaged proteins | Most neurodegenerative diseases |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Hyperphosphorylation, acetylation, proteolytic cleavage | TDP-43 hyperphosphorylation suppresses condensation but can promote aggregation [16] | ALS/FTD, Alzheimer's disease |

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Aggregation

In Vitro Aggregation Assays

Reductionist in vitro approaches provide fundamental insights into the molecular mechanisms driving protein aggregation along the continuum. The Thioflavin T (ThT) binding assay represents one of the most widely employed techniques for monitoring amyloid formation kinetics. ThT is a fluorescent dye that exhibits enhanced emission upon binding to the cross-β-sheet structure characteristic of amyloid fibrils. The typical protocol involves incubating the protein of interest (e.g., α-synuclein, Aβ, or hnRNPA1) under conditions that promote aggregation (e.g., constant shaking at 37°C in appropriate buffers), with periodic measurement of ThT fluorescence using a spectrofluorometer (excitation ~450 nm, emission ~482 nm). This assay allows researchers to quantify the kinetics of fibril formation, characterized by an initial lag phase (nucleation), followed by a growth phase (elongation), and finally a plateau phase (saturation) [22] [17].

For α-synuclein fibrillation, a specific protocol involves incubating the protein at 1 mg/mL in 20 mM Mes buffer (pH 6.5) at 37°C with continuous shaking. During the lag phase (approximately 6 hours under these conditions), oligomeric granular intermediates can be isolated. These granules, with an average diameter of 18.9±2.6 nm and composed of approximately 11 monomers, can undergo nearly instantaneous fibrillation when subjected to shear forces, such as those generated during centrifugal filtration at 14,000×g for 12 minutes. This demonstrates the sensitivity of metastable oligomeric intermediates to physical perturbation and provides a model for studying environmental influences on aggregation kinetics [22].

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy complements ThT assays by monitoring changes in protein secondary structure during the aggregation process. Proteins in soluble, monomeric states typically display spectra characteristic of random coils, with a pronounced minimum near 200 nm. As aggregation proceeds and β-sheet content increases, the CD spectrum shifts, developing a minimum at approximately 218 nm. This technique allows researchers to track structural transitions throughout the aggregation process without requiring external dyes [22].

Analyzing Condensates and Their Properties

Characterizing the material properties of biomolecular condensates is essential for understanding their role in the aggregation continuum. Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) represents a key technique for assessing condensate dynamics. In a standard FRAP experiment, a specific region within a condensate is bleached using a high-intensity laser, and the subsequent recovery of fluorescence due to the influx of unbleached molecules is monitored over time. Liquid-like condensates typically exhibit rapid fluorescence recovery, indicating high internal mobility and dynamic exchange with the surrounding environment. In contrast, solid-like aggregates show little to no recovery, reflecting their immobile nature. This technique can be applied to both in vitro reconstituted condensates and cellular structures such as stress granules [18].

Static and dynamic light scattering (SLS/DLS) provide quantitative information about the size, molecular weight, and assembly state of proteins and condensates. SLS measures the time-averaged intensity of scattered light to determine molecular weight and identify self-associative behavior (indicated by a negative second virial coefficient, A2), while DLS analyzes fluctuations in scattering intensity to determine hydrodynamic radius and size distributions. For example, SLS analysis of α-synuclein granules revealed a molecular mass of approximately 159 kDa and a negative A2 value of -8.41×10⁻⁷, indicating their self-associative nature [22].

Advanced microscopy techniques, including atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), provide high-resolution structural information about different species along the aggregation continuum. AFM can resolve oligomeric granules and protofibrils based on their topographical features, while TEM with negative staining (e.g., using uranyl acetate) enables visualization of mature amyloid fibrils. These techniques are often employed in conjunction with biochemical assays to correlate structural features with biochemical properties [22].

Cellular Models

Cellular models provide a more physiologically relevant context for studying aggregation within the complex intracellular environment. A common approach involves transfection of cells with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutant aggregation-prone proteins (e.g., FUS, TDP-43, or SOD1) fused to fluorescent tags such as GFP. The localization, dynamics, and aggregation behavior of these proteins can then be monitored using live-cell imaging, particularly in response to various stressors that induce condensate formation, including heat shock (42-45°C), hypoxia/acidosis (1% O₂, pH 6.0), or proteotoxic stress (e.g., arsenite treatment) [17].

To assess the functionality of specific pathways in aggregation processes, researchers employ pharmacological inhibitors. For instance, actinomycin D (transcription inhibition), cycloheximide (translation inhibition), and staurosporine (kinase inhibition) can be used to determine whether de novo gene expression, protein synthesis, or specific signaling pathways are required for stress-induced aggregation. Studies using these inhibitors have revealed that A-body recruitment of β-amyloid (1-42) occurs independently of new transcription or translation, suggesting that pre-existing cellular factors mediate this process [17].

The reversibility of aggregation can be tested by transferring stressed cells back to normal growth conditions and monitoring the dissolution of condensates and aggregates. Disease-linked mutations often impair this reversibility, leading to persistent aggregates that evolve into pathological inclusions. This cellular paradigm effectively models key aspects of the aggregation continuum and enables screening for genetic and pharmacological modifiers of the process [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying the Aggregation Continuum

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | α-Synuclein, hnRNPA1, Aβ(1-42) | In vitro aggregation assays (ThT, CD), condensate formation | Kinetics studies, biophysical characterization [18] [22] |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Tags | Thioflavin T (ThT), GFP-tagged constructs | Detect amyloid structures, monitor protein localization and dynamics | In vitro fibrillation, live-cell imaging, FRAP [22] [17] |

| Cell Lines | Immortalized neuron-like cells, primary neurons | Model cellular aggregation in relevant cell types | Transfection, stress induction, imaging [17] |

| Stress Inducers | Sodium arsenite, Heat shock, Hypoxia chambers (1% O₂) | Induce biomolecular condensate formation (e.g., SGs, A-bodies) | Cellular stress response studies [17] |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Actinomycin D, Cycloheximide, Diclofenac | Dissect molecular pathways; potential therapeutic compounds | Pathway analysis, small-molecule screening [17] |

| Antibodies | Anti-CDC73, Anti-TDP-43, Anti-p62 | Detect specific aggregate components, markers | Immunofluorescence, Western blot [17] |

Visualization of the Aggregation Continuum and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: The Protein Aggregation Continuum. This diagram illustrates the dynamic transitions between functional, physiological states and pathological aggregates, highlighting key decision points influenced by genetic and environmental factors.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying Protein Aggregation. This flowchart outlines integrated in vitro and cellular approaches for characterizing proteins across the aggregation continuum, from initial purification to final data analysis.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The aggregation continuum framework provides a sophisticated foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases. Rather than viewing aggregation as a monolithic process to be completely inhibited, this perspective encourages targeted interventions that maintain functional states while preventing pathological transitions. Several promising approaches have emerged from recent research, focusing on enhancing cellular mechanisms that preserve proteostasis and specifically target the liquid-to-solid transition.

Stabilizing the metastable state of biomolecular condensates represents a compelling therapeutic strategy. Recent research demonstrates that engineered protein mutants designed to enhance the metastability of hnRNPA1 condensates can suppress fibril formation and restore normal stress granule dynamics in cells bearing ALS-causing mutations [20] [21]. This suggests that small molecules or biological therapeutics that reinforce the liquid-like properties of condensates could prevent the initiation of pathological aggregation. The finding that stress granule interiors actually suppress fibril formation, while surfaces can act as nucleation sites, further refines this approach, suggesting that therapeutics should aim to enhance the internal environment of condensates rather than prevent their formation entirely [20].

Targeting the specific molecular interactions that drive aberrant phase transitions offers another strategic approach. For RNA-binding proteins like TDP-43 and FUS, this might involve developing compounds that disrupt the abnormal protein-protein interactions mediated by their low-complexity domains while preserving their functional interactions. For instance, compounds that stabilize the α-helical structure in the TDP-43 low-complexity C-terminal domain could prevent its pathological aggregation [16]. Similarly, the identification of diclofenac as a repressor of β-amyloid aggregation in cellular models, potentially through modulation of cyclooxygenases and the prostaglandin synthesis pathway, highlights the potential of repurposing existing drugs and underscores the importance of cellular model systems in identifying compounds that might be missed in traditional in vitro screens [17].

Enhancing cellular quality control mechanisms provides a complementary therapeutic avenue. Given the critical role of molecular chaperones in maintaining proteostasis, strategies to boost chaperone expression or function under stress conditions could prevent the accumulation of aggregation-prone species. This is particularly relevant in the context of age-related neurodegenerative diseases, where chaperone capacity typically declines. Similarly, enhancing autophagy pathways to clear early aggregates before they mature into pathological fibrils represents a promising approach, as evidenced by the involvement of autophagy receptors like p62 in protein aggregate clearance [10].

The aggregation continuum model also suggests that therapeutic timing is critical. Interventions early in the disease process might focus on maintaining condensate dynamics, while later interventions might prioritize disrupting mature fibrils or enhancing their clearance. Combining these approaches—stabilizing functional states, preventing pathological transitions, and enhancing clearance mechanisms—offers the most promising path forward for developing effective treatments for aggregation-related neurodegenerative diseases.

The maintenance of cellular function requires exquisite coordination of protein folding, modification, and quality control mechanisms. Within this framework, molecular chaperones, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and environmental cues serve as critical regulators of proteostasis—the delicate balance between protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation. When these regulatory systems falter, the consequences can be severe, leading to protein misfolding, aggregation, and the formation of biomolecular condensates with pathological properties. These aberrant structures are now recognized as hallmarks of numerous neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), as well as certain cancers and age-related conditions [23] [24].

Biomolecular condensates, membraneless organelles formed through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), compartmentalize cellular processes in space and time. While physiological condensates perform essential functions, their dysregulation ("condensatopathies") contributes to disease pathogenesis through multiple mechanisms: abnormal formation or clearance, improper material properties, and mislocalization of critical biomolecules [24] [25]. Understanding how chaperones, PTMs, and environmental signals regulate both normal proteostasis and disease-associated aggregation represents a frontier in biomedical research with significant therapeutic implications.

Molecular Chaperones: First Responders in Proteostasis

Chaperone Functions and Mechanisms

Molecular chaperones comprise a diverse family of proteins that facilitate proper folding, assembly, and intracellular localization of other proteins. Many chaperones, particularly heat shock proteins (HSPs), are highly expressed in response to cellular stress and play pivotal roles in preventing protein aggregation [26]. They function as essential components of the cellular quality control system, not only aiding folding but also targeting irreversibly misfolded proteins for degradation.

Recent structural biology breakthroughs have illuminated the precise mechanisms of chaperone action. The first full-length structures of Hsp40 and Hsp70 in complex have revealed key regulatory regions governing their function. These chaperones work in tandem through a carefully orchestrated handoff mechanism: Hsp40 first binds a misfolded client protein, then uses a specific phenylalanine residue in its G/F-rich region to bind Hsp70's substrate binding site, effectively transferring the client to Hsp70 for refolding [27]. This process is energy-dependent—when ATP binds to Hsp70, it induces a conformational change that releases the client protein back into the cell, allowing both chaperones to participate in additional rounds of refolding [27].

Table 1: Key Chaperone Complexes and Their Functions

| Chaperone Complex | Components | Primary Functions | Disease Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70-Hsp40 | Hsp70, Hsp40 | Binds misfolded proteins, facilitates refolding through ATP-dependent mechanism, prevents aggregation [27] | Neurodegenerative diseases, Cancer [27] [26] |

| Nascent Polypeptide-Associated Complex (NAC) | Egd1, Egd2, Btt1 subunits | Ribosome-associated chaperone, co-translational folding, aggregate organization [28] | Huntington's disease, Prion disorders [28] |

| Heat Shock Proteins | Hsp70, Hsp40, Hsp104 | Stress-responsive chaperones, prevent protein aggregation, disaggregation functionality [26] | Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, ALS [26] |

Chaperones as Therapeutic Targets

The critical role of chaperones in preventing protein aggregation makes them promising therapeutic targets for numerous diseases. Research has demonstrated that disrupting specific chaperone complexes can significantly alter aggregation patterns and cellular toxicity. For instance, partial removal of the nascent polypeptide-associated complex (NAC) in yeast models reduces polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity associated with Huntington's disease, while also changing aggregate morphology [28]. Similarly, enhanced expression of specific HSPs can halt the accumulation and aggregation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative conditions [26].

Therapeutic strategies targeting chaperones include both inhibition and enhancement approaches. Small molecules that modulate chaperone activity, known as condensate-modifying therapeutics (c-mods), represent a novel class of investigational drugs that target disease-associated condensates [29] [25]. These compounds can dissolve aberrant condensates, restore correct composition, or sequester overactive proteins into condensates where they are sentenced to degradation [25].

Post-Translational Modifications: Precision Regulators of Protein Function

PTM Diversity and Biological Significance

Post-translational modifications represent chemical modifications that occur after protein synthesis, dramatically expanding the functional diversity of the proteome. These modifications—including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, and glycosylation—serve as precise molecular switches that regulate protein activity, stability, localization, and interactions [30]. The combinatorial nature of PTMs creates a sophisticated regulatory network that enables cells to respond dynamically to intracellular and extracellular signals.

PTMs play particularly important roles in regulating biomolecular condensates and aggregation pathways. Phosphorylation, for instance, can significantly alter the phase separation behavior of proteins, either promoting or inhibiting condensate formation depending on the specific protein and cellular context [24]. Ubiquitination serves as a critical degradation signal, targeting misfolded proteins for proteasomal clearance and thereby preventing their accumulation into toxic aggregates [23].

Table 2: Key Post-Translational Modifications in Proteostasis Regulation

| PTM Type | Functional Consequences | Analytical Methods | Disease Connections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | Alters protein charge, regulates phase separation, controls enzyme activity [24] | GoDig 2.0 phosphoproteomics, mass spectrometry [31] [30] | Alzheimer's (tau hyperphosphorylation) [31] [30] |

| Ubiquitination | Marks proteins for degradation, regulates condensate composition [23] | Diglycyl-lysine peptide quantification [31] | Parkinson's disease, Protein aggregation disorders [23] |

| Glycosylation | Affects protein stability, cell signaling, half-life of therapeutic proteins [30] | Mass spectrometry, glycoproteomics [30] | Cancer, Biotherapeutic optimization [30] |

Analytical Advances in PTM Research

Recent technological innovations have dramatically improved our ability to detect and quantify PTMs. The GoDig 2.0 platform enables sensitive, multiplexed targeted pathway proteomics without manual scheduling or synthetic standards, increasing sample multiplexing 35-fold compared to previous versions [31]. This platform can quantify >99% of 800 peptides in a single run and has been used to compile libraries of 23,989 human phosphorylation sites and 20,946 reactive cysteines from phosphoproteomic datasets [31].

These advanced proteomic capabilities are driving applications across multiple domains:

- Biomarker Discovery: PTM analysis identifies disease-specific modification patterns, such as hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer's disease [30].

- Drug Development: Monitoring phosphorylation patterns helps assess kinase inhibitor efficacy during preclinical trials [30].

- Bioprocess Optimization: Glycosylation profiling ensures consistency in monoclonal antibody production [30].

- Quality Control: PTM verification ensures therapeutic proteins meet specifications before clinical use [30].

Environmental Cues: External Regulators of Cellular Proteostasis

Stress Responses and Proteostasis Adaptation

Cells constantly encounter environmental and physiological fluctuations that challenge homeostasis, including temperature shifts, oxidative stress, nutrient availability, and osmotic pressure. In response to these cues, cells activate sophisticated stress response pathways that modulate chaperone expression, PTM patterns, and quality control systems to maintain proteostasis [24] [32].

Heat shock proteins represent a primary response mechanism to environmental stressors. Their rapid upregulation under stress conditions enhances cellular folding capacity and helps prevent aggregation of denatured proteins [26]. The interconnected nature of stress responses means that different environmental challenges often activate overlapping protective pathways, with convergence on master regulators such as HSF1 (heat shock factor 1) that coordinate chaperone expression.

Environmental stress also profoundly influences biomolecular condensate dynamics. Numerous condensates, including stress granules and P-bodies, form or remodel in response to specific environmental cues, compartmentalizing stress response components and regulating survival pathways [24]. When properly regulated, these assemblies facilitate adaptation; when dysregulated, they can evolve into pathological aggregates.

Experimental Modeling of Environmental Stress

Researchers have developed sophisticated tools to investigate how environmental cues affect proteostasis. The inducible Protein Aggregation Reporter (iPAR) system uses monomeric fluorescent protein reporters fused to a ΔssCPY* aggregation biomarker, with expression controlled by the copper-regulated CUP1 promoter [32]. This system enables quantitative study of cytoplasmic aggregate kinetics and inheritance features in response to stressors like hyperosmotic shock and elevated temperature.

Key findings from iPAR studies include:

- Cytoplasmic aggregates are mobile and contain between tens to several hundred iPAR molecules

- Mean aggregate size increases with extracellular hyperosmotic stress

- Larger iPAR aggregates associate with nuclear and vacuolar compartments

- Unlike organelles, proteotoxic accumulations are not inherited by daughter cells during asymmetric cell division [32]

Diagram 1: Environmental stress triggers protein misfolding and chaperone responses that influence biomolecular condensate formation, leading to either adaptation or disease.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Essential Research Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Cellular Regulators

| Research Tool | Composition/Type | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPAR (inducible Protein Aggregation Reporter) | Monomeric fluorescent protein + ΔssCPY* biomarker, CUP1 promoter [32] | Quantitative study of cytoplasmic aggregate kinetics in live cells | Copper-inducible, monomeric tags prevent artifacts, compatible with epifluorescence and Slimfield microscopy [32] |

| GoDig 2.0 Platform | Multiplexed targeted proteomics platform [31] | Quantifies PTMs, compound-protein interactions, disease biomarkers | 35-fold multiplexing, measures >99% of 800 peptides in single run, no synthetic standards required [31] |

| C-mods (Condensate-modifying therapeutics) | Small molecule inhibitors/activators [29] [25] | Modifies biomolecular condensate formation, composition, or material properties | Targets historically 'undruggable' proteins, novel mechanisms of action [25] |

| HSP70-HSP40 Complex | Chaperone protein complex [27] | Studies chaperone-mediated refolding, handoff mechanisms | First full-length structures available, key for understanding misfolded protein processing [27] |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Advanced methodological approaches combine multiple techniques to unravel the complexities of cellular regulation. The following workflow illustrates a typical integrated protocol for studying protein aggregation and condensate dynamics:

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for studying cellular regulation of protein aggregation, combining model systems, stress induction, multiple detection methods, and functional validation.

For the specific protocol of iPAR methodology in yeast:

- Strain Construction: Clone iPAR constructs (mEGFP, mNeonGreen, or mScarlet-I fused to ΔssCPY*) into plasmids with CUP1 promoter and appropriate selection markers (URA3 or LEU2) [32].

- Protein Induction: Grow yeast cultures to mid-log phase, induce iPAR expression with copper sulfate (50-100 μM final concentration, optimized for strain) [32].

- Stress Application: Apply defined stress conditions (e.g., 0.5-1.0 M NaCl for hyperosmotic stress, elevated temperature 37-42°C) for specified durations.

- Microscopy and Imaging: Image live cells using epifluorescence, confocal, or Slimfield microscopy. For Slimfield, use millisecond sampling to track single molecules [32].

- Image Analysis: Quantify aggregate number, size, distribution, and mobility using appropriate software. Analyze inheritance patterns during cell division via time-lapse imaging.

- Data Interpretation: Correlate aggregate properties with stress parameters and cellular viability.

Similar integrated approaches combining cryo-EM, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and X-ray crystallography have enabled determination of full-length chaperone structures, revealing previously unknown mechanisms of Hsp40-Hsp70 complex function [27].

Integration and Therapeutic Perspectives

Convergent Regulatory Networks

Chaperones, PTMs, and environmental cues do not function in isolation but rather form interconnected networks that collectively maintain proteostasis. Environmental stressors induce both chaperone expression and specific PTM patterns that collaboratively combat protein misfolding. Conversely, chronic stress can overwhelm these systems, leading to aberrant PTM signatures and chaperone dysfunction that accelerate aggregation.

This integration is particularly evident in biomolecular condensates, where chaperones, PTM enzymes, and stress-responsive proteins coalesce to regulate condensate composition, dynamics, and material properties [24] [23]. The emerging understanding of these networks provides multiple intervention points for therapeutic development, from enhancing chaperone function to correcting pathological PTMs.

Emerging Therapeutic Approaches

Several promising therapeutic strategies targeting cellular regulators are currently under investigation:

Chaperone-Targeted Therapies: Approaches include small molecule enhancers of chaperone function, gene therapy to increase expression of protective chaperones, and compounds that modulate specific chaperone-client interactions [26]. The discovery that disrupting the NAC reduces polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity suggests new targeting strategies for Huntington's disease and related disorders [28].

PTM-Targeted Interventions: Kinase inhibitors that correct aberrant phosphorylation patterns, deubiquitinase inhibitors that enhance clearance of misfolded proteins, and glycosylation-modifying compounds represent active areas of development [30]. The ability to comprehensively profile PTMs using platforms like GoDig 2.0 enables personalized approaches based on individual PTM signatures [31].

Condensate-Modifying Therapeutics (C-mods): Companies like Dewpoint Therapeutics are pioneering drugs that specifically target disease-associated condensates ("condensatopathies") [25]. These c-mods can dissolve aberrant condensates, restore correct composition, or sequester pathogenic proteins. High-content imaging and AI-driven analysis of condensate phenotypes enable screening and optimization of c-mods with desired mechanisms of action [25].

The integration of condensate science throughout the drug discovery pipeline shows promise for revolutionizing therapeutic development for complex diseases. Condensate biomarkers that translate from in vitro models to patients could enhance predictive accuracy and reduce reliance on animal testing [25]. As our understanding of cellular regulators continues to advance, so too will opportunities for innovative interventions targeting protein aggregation diseases at their root causes.

The study of neurodegenerative diseases has undergone a paradigm shift with the recognition that biomolecular condensates and their pathologic phase transitions play fundamental roles in disease initiation and progression. Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) represent three clinically distinct neurodegenerative disorders that share underlying mechanisms involving the transition of specific proteins from soluble states to solid pathological aggregates [33]. Despite involving different proteins and brain regions, each disease follows a similar pattern of protein misfolding, aggregation, and propagation throughout the brain [33].

Biomolecular condensates are membrane-less organelles assembled through liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) that organize functionally related biomolecules within cells [34]. In healthy neurons, condensates serve crucial regulatory functions, but under pathological conditions, they can undergo aberrant phase transitions from dynamic liquid-like states to solid-like aggregates that characterize neurodegenerative diseases [35]. This transition represents a critical juncture where normal cellular physiology shifts to pathology, with the solid aggregates exhibiting properties that include cytotoxicity, seeding capability, and propagation between cells [33].

The core proteins implicated in these disorders—tau and amyloid-β in AD, α-synuclein in PD, and TDP-43 in ALS—all share the ability to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation and subsequent liquid-to-solid transitions [34]. This review examines the shared and distinct mechanisms of pathologic phase transitions across these neurodegenerative conditions, with particular emphasis on their implications for therapeutic development.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Pathologic Phase Transitions

The Biophysics of Protein Misfolding and Aggregation

The process of protein misfolding and aggregation follows a predictable pathway best described by the seeding-nucleation model [33]. During this process, a slow and thermodynamically unfavorable nucleation phase is followed by a rapid elongation stage. The nucleation phase involves the formation of a stable seed or nucleus of polymerized protein, which then rapidly grows by incorporating monomeric protein into the polymer [33]. Large polymers can subsequently fragment, generating more seeds to propagate the reaction throughout the brain.

From a biophysical perspective, the process of protein misfolding and aggregation involves rearranging the native protein structure into a series of β-strands stabilized by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. These structural rearrangements create 'sticky' ends that attract molecules of the folded or partially unfolded protein, forcing their misfolding to fit into the cross-β polymeric structure characteristic of amyloid fibrils [33]. Although the primary scaffold of the misfolded aggregates is similar across different proteins, individual molecules can adopt varied structures, giving rise to conformational strains with distinct pathological properties.

Table 1: Key Proteins and Their Pathologic Transitions in Neurodegeneration

| Disease | Primary Protein(s) | Cellular Location of Aggregates | Characteristic Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Amyloid-β, Tau | Extracellular (Aβ), Intracellular (tau) | Amyloid plaques, Neurofibrillary tangles |

| Parkinson's Disease | α-synuclein | Intracellular | Lewy bodies |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | TDP-43 | Intracellular | Cytoplasmic inclusions |

| Multiple System Atrophy | α-synuclein | Intracellular | Glial cytoplasmic inclusions |

From Liquid Condensates to Solid Aggregates

Biomolecular condensates transition from functional liquid states to pathogenic solid states through several interconnected mechanisms influenced by both intrinsic protein properties and external cellular factors [35]. Five key factors determine how the condensate environment influences protein aggregation:

- Local concentration enhancement: Condensates concentrate specific proteins, increasing interaction probabilities

- Distinct chemical microenvironment: The interior of condensates creates unique conditions that can accelerate aggregation

- Interface localization: Proteins can localize at condensate interfaces, promoting specific interactions

- Altered energy landscape: The condensate environment changes the energetic barriers of aggregation pathways

- Chaperone presence: Molecular chaperones within condensates can either prevent or facilitate aggregation [35]

This liquid-to-solid transition is particularly significant in the context of cellular aging and proteostatic decline. As organisms age, the efficiency of protein quality control mechanisms deteriorates, leading to increased accumulation of damaged proteins and compromised cellular ability to maintain folding homeostasis [36]. The resulting flux of metastable proteins creates a cellular environment where pathologic phase transitions are more likely to occur.

Prion-like Propagation of Protein Aggregates

A groundbreaking discovery in neurodegeneration research is that misfolded protein aggregates in AD, PD, and ALS can self-propagate through seeding and spread pathological abnormalities between cells and tissues in a manner akin to the behavior of infectious prions [33]. This prion-like property allows pathological protein species to template their conformation onto native proteins, thereby propagating the disease pathology throughout connected neural networks.

The molecular basis for this propagation lies in the ability of protein aggregates to act as seeds that initiate the misfolding and aggregation of native, monomeric proteins in host cells [33]. This seeding capability is a common feature of all misfolded proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, suggesting they have the potential to behave as prions [33]. Supporting this concept, studies with Aβ, tau, and α-Syn have demonstrated that inoculation with tissue homogenates from patients affected by neurodegenerative diseases or transgenic mouse models rich in protein aggregates can induce disease pathology in recipient cellular or animal models [33].

Disease-Specific Mechanisms and Cross-Talk

Alzheimer's Disease: Aβ and Tau Phase Transitions

In Alzheimer's disease, two primary proteins undergo pathologic phase transitions: amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau. Aβ peptides derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing can undergo liquid-liquid phase separation and form amyloid plaques, while tau protein undergoes phase separation and forms neurofibrillary tangles [33] [34]. The process begins with the misfolding of these proteins from their native states to form intermolecular β-sheet-rich structures, ranging from small oligomers to large fibrillar aggregates [33].

While historically the large protein deposits were considered the neurotoxic species, emerging evidence indicates that smaller, soluble misfolded oligomers—precursors of the fibrillar aggregates—appear to be the primary culprits of neurodegeneration [33]. These oligomeric species are highly dynamic and exist in equilibrium with monomers and fibrils, with some serving as on-pathway intermediates for amyloid fibril formation, while others represent terminal off-pathway products with particularly high toxicity [33].

Recent evidence indicates that both Aβ and tau assemble into liquid-like protein phases through the highly coordinated process of liquid-liquid phase separation [34]. The transition of these proteins from liquid-like condensates to solid aggregates follows a trajectory influenced by numerous factors, including post-translational modifications, RNA interactions, and cellular stress conditions.

Parkinson's Disease: α-Synuclein Misfolding

In Parkinson's disease, the primary protein responsible for pathologic aggregation is α-synuclein, which forms intracellular inclusions known as Lewy bodies [33]. The process of α-synuclein misfolding follows the seeding-nucleation model, where initially slow nucleation is followed by rapid elongation and spread throughout vulnerable brain regions [33].