Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating Computational Binding Site Predictions with Experimental Data

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals on validating computational binding site predictions.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating Computational Binding Site Predictions with Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals on validating computational binding site predictions. It covers the foundational principles of various prediction methods, from traditional geometry-based to modern AI-driven approaches, and details the experimental techniques—such as X-ray crystallography, mutagenesis, and biophysical assays—used for confirmation. A significant focus is placed on benchmarking strategies, using standardized datasets and metrics to compare tool performance, and on troubleshooting common pitfalls to optimize prediction accuracy. By synthesizing methodological insights with rigorous validation frameworks, this guide aims to enhance the reliability of computational predictions and accelerate their translation into successful drug discovery projects.

The Why and How: Core Principles of Computational Binding Site Prediction

The Critical Role of Binding Site Identification in Modern Drug Discovery

Identifying where a small molecule binds to a protein target is a critical first step in modern drug discovery. The characterization of binding sites—protein regions that interact with organic small molecules to modulate function—is essential for understanding and rationally designing therapeutic compounds [1]. Traditional experimental methods for identifying these sites, such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy,, while highly accurate, are constrained by long experimental cycles and significant costs [2] [3]. This has driven the development of computational approaches that can rapidly and accurately predict binding sites from protein structures or even primary sequences, thereby conserving substantial time and financial resources in the drug discovery pipeline [2]. These computational methods have evolved from early geometry-based techniques to sophisticated machine learning (ML) and molecular dynamics (MD) approaches that can now identify even cryptic binding sites—pockets that exist only in the ligand-bound state of a protein [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current computational binding site prediction methods, examines their performance against standardized benchmarks, and details the crucial experimental protocols for validating computational predictions.

Computational methods for druggable site identification can be broadly categorized into several classes based on their underlying principles and the data they utilize. The following table summarizes the fundamental principles, advantages, and disadvantages of the main methodological categories.

Table 1: Categories of Computational Methods for Binding Site Identification

| Method Category | Fundamental Principle | Representative Tools | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Geometry Methods | Identifies cavities by analyzing the geometry of the protein's molecular surface [5]. | fpocket [5], Ligsite [5], Surfnet [5] | Fast; no requirement for prior knowledge of ligands or homologous templates. | May miss cryptic or transient pockets; limited by static structure input. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Methods | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, allowing observation of binding events and pocket dynamics [4] [6]. | Custom MD simulations (e.g., for PTP1b [6]) | Can prospectively discover novel allosteric sites and cryptic pockets [4] [6]; models flexible protein dynamics. | Computationally expensive, limiting high-throughput application. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Methods | Uses trained classifiers to predict binding residues or pockets based on learned features from protein structure and/or sequence data [4] [5]. | P2Rank [5], DeepPocket [5], LABind [3], PUResNet [5] | Favorable balance of speed and accuracy; can learn complex patterns from large datasets [4]. | Performance can be limited by the availability and quality of training data. |

| Ligand-Aware Prediction | Explicitly incorporates ligand information during training and prediction to learn distinct binding characteristics for different ligands [3]. | LABind [3] | Can predict sites for unseen ligands; integrates key interaction context. | Relatively new approach; requires ligand structural information (e.g., SMILES). |

| Template- & Conservation-Based | Leverages evolutionary conservation or structural homology to infer binding sites based on known sites in related proteins [3] [7]. | IonCom [3], sequence-homology predictors [7] | Can provide functional insights through evolutionary conservation. | Limited by the availability of homologous templates or conserved residues. |

A significant advancement in the field is the emergence of ligand-aware methods like LABind, which utilize graph transformers and cross-attention mechanisms to learn the distinct binding characteristics between a protein and a specific ligand by explicitly modeling ions and small molecules alongside the protein structure [3]. This represents an evolution from earlier single-ligand-oriented or multi-ligand-oriented methods that were either tailored to one ligand type or did not explicitly consider ligand properties during prediction [3].

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparative Analysis

Independent benchmarking studies are crucial for objectively evaluating the real-world performance of these tools. A comprehensive 2024 study compared 13 ligand binding site predictors, spanning three decades of research, against the LIGYSIS dataset—a curated reference dataset of human protein-ligand complexes that aggregates biologically relevant interfaces [5]. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from this large-scale benchmark.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Binding Site Predictors on the LIGYSIS Benchmark

| Prediction Method | Type | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | Key Finding from Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fpocket (re-scored by PRANK) | Geometry-based + ML re-scoring | 60 | Not Specified | Demonstrates the benefit of combining methods; achieved highest recall. |

| DeepPocket (re-scoring) | Machine Learning | 60 | Not Specified | Tied for highest recall; effective at re-scoring potential pockets. |

| P2Rank | Machine Learning | 49 | Not Specified | Established ML method with strong performance. |

| PUResNet | Machine Learning | 46 | Not Specified | Deep learning-based approach. |

| GrASP | Machine Learning | 45 | Not Specified | Uses graph attention networks on surface atoms. |

| IF-SitePred | Machine Learning | 39 | Not Specified | Achieved lowest recall among the ML methods tested. |

| Surfnet | Geometry-based | Not Specified | +30 (improvement) | Demonstrated that re-scoring can improve precision by 30%. |

| IF-SitePred | Machine Learning | +14 (improvement) | Not Specified | Showed that a stronger scoring scheme could improve recall by 14%. |

The study proposed top-N+2 recall as a universal benchmark metric, where N is the true number of binding sites in a protein, to account for the redundancy in predicted sites [5]. A critical finding was that redundant prediction of binding sites detrimentally impacts performance, and implementing stronger pocket scoring schemes can lead to substantial improvements—up to 14% in recall and 30% in precision for some methods [5].

For ligand-aware prediction, LABind has demonstrated superior performance on independent benchmarks (DS1, DS2, DS3), outperforming other advanced methods in predicting binding sites for small molecules, ions, and—crucially—unseen ligands [3]. Its performance is often measured by metrics like Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR), which are more reliable for imbalanced classification tasks where binding residues are far outnumbered by non-binding residues [3].

Experimental Validation: Bridging Computation and Experiment

Computational predictions gain credibility when validated by experimental evidence. This synergy is powerfully illustrated by a prospective study on the difficult pharmaceutical target Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1b) [6].

Experimental Protocol: MD-Driven Fragment Binding Validation

The following workflow details the key steps for experimentally validating computationally predicted binding poses, as demonstrated in the PTP1b study [6].

Key Experimental Steps

- Fragment Screening: Identify weak-binding fragment hits against the target protein using a biophysical method like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). In the PTP1b study, this identified fragments DES-4799 and DES-4884 [6].

- Long-Timescale MD Simulations: Perform unbiased, all-atom MD simulations of the protein in solution with the fragments, allowing them to freely diffuse and associate/dissociate from the protein. Simulations should be long enough to observe multiple binding and unbinding events (e.g., 100 μs) [6].

- Pose and Conformation Analysis: Identify dominant binding poses and any protein conformational changes (e.g., side-chain rearrangements like Phe196 in PTP1b) that occur upon fragment binding [6].

- Crystallographic Validation: Solve high-resolution crystal structures of the protein bound to the fragment hits. This serves as the ground truth for validation [6].

- Pose Comparison: Quantitatively compare the computationally predicted poses with the experimentally observed crystal structure poses by calculating metrics like heavy-atom root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). In the PTP1b case, the MD-predicted poses closely matched the crystal structures, with fragment heavy-atom RMSDs as low as 0.57 Å [6].

- Further Validation with Analogues: Synthesize chemically related fragments and obtain their co-crystal structures to further validate the predicted binding mode and explore structure-activity relationships [6].

This protocol successfully provided the first demonstration of MD simulations being used prospectively to determine fragment binding poses for previously unidentified allosteric pockets on a pharmaceutically relevant target [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table lists key reagents, software, and datasets essential for conducting research in computational binding site identification and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Binding Site Identification

| Resource Name | Type | Brief Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| LIGYSIS Dataset [5] | Benchmark Dataset | A curated dataset of 30,000 protein-ligand complexes used for standardized benchmarking of prediction methods. It improves on earlier sets by considering biological units. |

| ProSPECCTs [1] | Benchmark Dataset | A collection of 10 datasets for evaluating pocket comparison approaches under various scenarios, including pairs of similar and dissimilar binding sites. |

| rDock [1] | Software | An open-source platform for rigid molecular docking calculations, used in workflows like PocketVec descriptor generation. |

| SMINA [3] [1] | Software | A fork of AutoDock VINA optimized for scoring and customizable for specific tasks like protein-ligand docking. |

| P2Rank [5] | Software | A robust, machine learning-based binding site predictor that is open source and relatively easy to install and use. |

| ESM-2 & Ankh [3] [7] | Software/Model | Protein language models used to generate powerful sequence and evolutionary representations of protein residues from primary sequence. |

| MolFormer [3] | Software/Model | A molecular language model used to represent molecular properties based on ligand SMILES sequences in ligand-aware prediction. |

| Glide Chemically Diverse Fragment Collection [1] | Compound Library | A set of 667 lead-like fragments used for inverse virtual screening in approaches like PocketVec. |

| MOE Lead-like Molecule Dataset [1] | Compound Library | A set of 1000 lead-like molecules used for generating pocket descriptors via docking. |

The field of binding site identification has matured significantly, with machine learning methods now offering a favorable balance of accuracy and speed for high-throughput applications, while molecular dynamics simulations provide unique insights into dynamic and cryptic pockets [4]. The critical trend for the future is the integration of multiple methods, such as combining MD with ML to expand our ability to predict and validate novel cryptic sites, or using ML to re-score geometry-based predictions, which has been shown to boost performance metrics like recall by significant margins [4] [5]. Furthermore, the rise of ligand-aware prediction and the availability of accurate predicted structures from AI like AlphaFold2 are opening new doors for proteome-wide characterization of the "druggable pocketome" [3] [1]. However, the gold standard remains the validation of computational predictions with high-resolution experimental data, a synergy that powerfully de-risks the early stages of drug discovery and accelerates the development of new therapeutics.

The accurate prediction of binding sites on protein targets represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling the rational design of therapeutic molecules. This field has evolved from traditional structure-based computational analyses to sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI)-driven models, creating a diverse toolkit for researchers. These methods aim to bridge the critical gap between in silico prediction and experimental validation, a process essential for confirming the biological relevance and druggability of identified sites. The integration of computational predictions with experimental binding data, such as affinity measurements from competitive inhibition assays, forms the foundation for validating these approaches [8]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of contemporary computational methods, evaluates their performance against experimental benchmarks, and details the protocols for their validation, offering a practical resource for scientists navigating this rapidly advancing landscape.

Computational approaches for binding site prediction can be broadly categorized into several distinct classes, each with underlying principles, advantages, and limitations. The following table summarizes these key methodologies:

Table 1: Classification of Computational Binding Site Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Methods [2] | Analyzes 3D protein structure (experimental or predicted) to identify pockets based on geometry, energy scoring, or molecular docking. | Directly models physical interactions; intuitive rationale; can identify allosteric/cryptic sites. | Highly dependent on accurate protein structures; struggles with conformational flexibility. |

| Sequence-Based Methods [7] | Uses evolutionary conservation (e.g., from PSSM) and machine learning on primary amino acid sequences to predict interaction residues. | Does not require 3D structure; applicable to a vast number of proteins with known sequences. | Cannot model conformational epitopes or steric constraints of binding. |

| AI/Deep Learning Methods [7] [9] | Employs deep neural networks (CNNs, RNNs, Transformers) on sequences, structures, or hybrid data to learn complex patterns for prediction. | High accuracy; ability to integrate diverse input features (sequence, structure, evolution); superior generalizability. | "Black box" nature reduces interpretability; requires large, high-quality training datasets. |

| Physics-Based Simulation Methods [8] | Uses Molecular Dynamics (MD) and alchemical free energy calculations (e.g., BAR, FEP) to model binding interactions and affinities. | Provides rigorous thermodynamic understanding; can model flexibility and solvent effects; highly accurate for affinity prediction. | Extremely high computational cost; requires significant expertise; time-consuming. |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Validation

The true value of any computational prediction is determined by its correlation with experimental results. The following table compares the performance of various methods based on key metrics and their subsequent experimental validation.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation of Prediction Methods

| Method / Tool | Reported Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation & Correlation | Key Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-SECP (Protein-DNA sites) [7] | Outperformed traditional methods on TE46/TE129 benchmarks (specific metrics not fully detailed in excerpt). | Framework integrates sequence-feature and sequence-homology predictors; performance validated on standardized, non-redundant datasets. | Uses benchmark datasets (TE46, TR646, TE129, TR573) clustered at <30% identity to ensure rigorous assessment. |

| AI-driven Epitope Predictors (e.g., MUNIS, GraphBepi) [9] | MUNIS: 26% higher performance than prior algorithms; Other DL models: ~87.8% accuracy (AUC=0.945) for B-cell epitopes. | MUNIS: Identified novel CD8+ T-cell epitopes in viral proteomes, validated via HLA binding and T-cell activation assays. GraphBepi: Predictions matched experimental assay accuracy. | GearBind GNN: Generated SARS-CoV-2 spike variants with 17x higher antibody binding affinity, confirmed by ELISA. |

| BAR Binding Free Energy Calculation [8] | Significant correlation (R² = 0.7893) with experimental pKD for β1AR agonists in active/inactive states. | Calculated binding free energies for 8 β1AR-ligand complexes showed strong correlation with experimentally measured binding affinities (pKD). | Case study on β1AR with full/partial agonists (isoprenaline, salbutamol, dobutamine, cyanopindolol) in active/inactive states. |

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) for GPCRs [10] | TM domain Cα RMSD accuracy of ~1 Å vs. experimental structures. | Models show high confidence (pLDDT >90) for orthosteric pockets, but ligand docking can fail due to sidechain/conformation issues in the binding site. | Systematic studies on 29 GPCRs with post-2021 structures reveal limitations in ECL-TM assembly and transducer interfaces. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: BAR Binding Free Energy Validation

The BAR method's validation provides a robust example of integrating computation with experiment [8].

- 1. System Preparation: The process begins with a 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex, typically from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM. For membrane proteins like GPCRs, the structure is embedded within an explicit lipid bilayer and solvated in water. Ions are added to neutralize the system.

- 2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Equilibration: The prepared system undergoes extensive MD simulation to equilibrate the solvent, lipids, and protein, ensuring stability before free energy calculation. This step is critical for relaxing the system and overcoming initial steric clashes.

- 3. Alchemical Transformation (λ steps): The binding free energy calculation is set up as an alchemical process where the ligand is gradually "decoupled" from its environment. This range is finely divided into numerous intermediate states, defined by a scaling parameter λ (ranging from 0, fully coupled, to 1, fully decoupled). Multiple independent simulations are run at each λ window.

- 4. BAR Analysis: The Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) algorithm analyzes the energy differences between adjacent λ states from the simulations. This analysis provides a highly accurate estimate of the binding free energy (ΔG).

- 5. Correlation with Experimental Data: The computed ΔG values for a series of ligand complexes are converted to predicted inhibition constants (pKD or pKi) and plotted against the experimentally measured values. A high coefficient of determination (R²) validates the computational protocol.

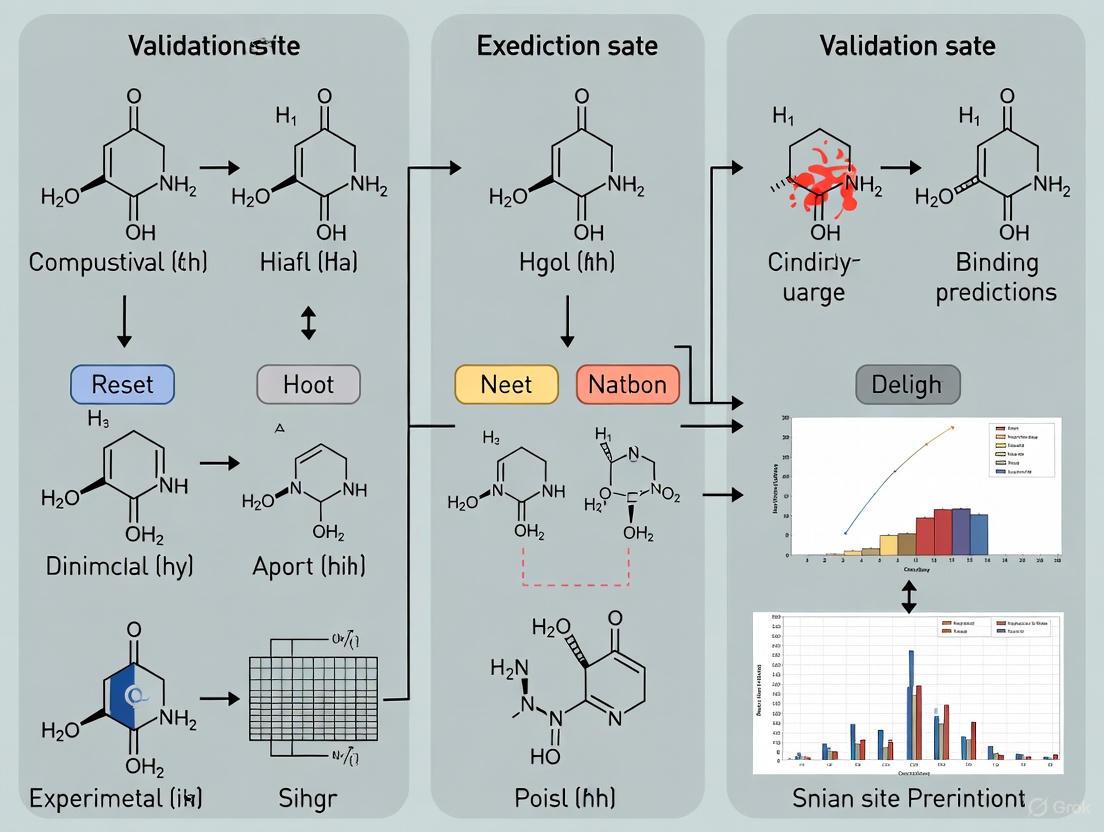

Diagram 1: Workflow for validating binding affinity predictions using the BAR method and experimental data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful binding site prediction and validation rely on a suite of computational and experimental tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Prediction and Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Category | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| PSI-BLAST [7] | Software Tool | Generates Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSMs) to extract evolutionary conservation features from protein sequences for machine learning models. |

| ESM-2 Protein Language Model [7] | AI Model | Converts protein primary sequences into high-dimensional embedding vectors that capture deep semantic and syntactic biological patterns for prediction. |

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) Model Bank [10] | Structural Resource | Provides high-accuracy predicted 3D protein structures for targets without experimental structures, enabling structure-based screening and analysis. |

| GROMACS/CHARMM/AMBER [8] | Simulation Engine | Software packages used to perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and free energy calculations, providing the physical basis for binding affinity prediction. |

| GPCR Constructs & Nanobodies [8] | Biological Reagent | Stabilize specific conformational states (e.g., active state with G-protein mimicking nanobodies) of proteins for both experimental and simulation studies. |

| Experimentally Determined pKD/IC50 Data [8] | Reference Dataset | Serves as the essential ground-truth benchmark for validating and refining the accuracy of computational binding affinity predictions. |

Integrated Workflow and Future Outlook

The most powerful applications combine multiple computational approaches into an integrated pipeline. A typical workflow may begin with sequence-based AI tools like ESM-SECP for initial, high-throughput scanning [7]. Promising targets then undergo structural analysis using AlphaFold2 models or experimental structures, followed by physics-based simulations for a select number of top candidates to obtain high-fidelity affinity predictions before committing to costly experimental validation [10] [8].

Future development is focused on overcoming current limitations. A significant challenge for AI-based structure prediction is capturing protein dynamics and the full spectrum of conformational states beyond single, static models [11] [10]. Future trends include generating state-specific ensembles (e.g., AlphaFold-MultiState for GPCRs) [10] and improving the explainability of AI models to build greater trust in their predictions. Furthermore, the community is working towards more robust and standardized benchmarking datasets to ensure fair comparisons and accelerate progress in this vital field [7].

The accurate identification of protein-ligand binding sites is fundamentally important for understanding biological processes and accelerating drug discovery [5]. Over the past three decades, significant effort has been dedicated to developing computational methods that predict binding sites from protein structures, with over 50 methods created representing a paradigm shift from geometry-based to machine learning approaches [5]. While these methods offer the promise of rapid, cost-effective screening, they inherently struggle with generalization and accuracy due to limitations in training data, algorithmic biases, and the complex nature of molecular interactions. This analysis objectively compares the performance of contemporary computational methods and demonstrates why experimental validation remains indispensable despite advancing computational capabilities.

Methodological Landscape of Binding Site Prediction

Computational methods for ligand binding site prediction employ diverse techniques, each with distinct theoretical foundations and limitations. Understanding this methodological spectrum is crucial for contextualizing performance variations and inherent constraints.

Table 1: Classification of Computational Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Representative Examples | Underlying Principle | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry-Based | fpocket, Ligsite, Surfnet [5] | Identifies cavities by analyzing molecular surface geometry using grids, spheres, or tessellation | Often fails to distinguish biologically relevant binding sites from superficial surface cavities |

| Energy-Based | PocketFinder [5] | Calculates interaction energies between protein and chemical probes | Highly dependent on force field parameters and simplified energy calculations |

| Template-Based | IonCom, MIB, GASS-Metal [3] | Matches known ligand binding sites from similar proteins using alignment algorithms | Performance deteriorates rapidly without high-quality homologous templates |

| Machine Learning-Based | P2Rank, DeepPocket, PUResNet, GrASP [5] | Uses trained models (random forest, CNN, GNN) on structural and sequence features | Limited by training data quality and diversity; struggles with novel fold types |

| Ligand-Aware Learning | LABind, LigBind [3] | Explicitly models ligand properties alongside protein features using cross-attention mechanisms | Effectiveness constrained by ligand representation and limited generalization to truly novel ligands |

The evolution from geometry-based to machine learning methods represents significant methodological advancement. Single-ligand-oriented methods are tailored to specific ligands, while multi-ligand-oriented methods attempt broader prediction capability but often overlook crucial differences in binding patterns among different ligands [3]. The recently developed LABind method utilizes graph transformers with cross-attention mechanisms to learn distinct binding characteristics between proteins and ligands, representing the current state-of-the-art in incorporating ligand information directly into prediction models [3].

Diagram 1: Methodological evolution from traditional to modern computational approaches shows increasing complexity in binding site prediction.

Comparative Performance Benchmarking

Independent benchmarking studies provide crucial objective performance assessments across prediction methodologies. The largest benchmark to date, evaluating 13 original methods and 15 variants against the LIGYSIS dataset (comprising biologically relevant protein-ligand interfaces), reveals significant performance variations and inherent limitations across methodological categories [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Prediction Methods

| Method | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | F1 Score | MCC | AUC | AUPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fpocket (PRANK rescored) | 60.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| IF-SitePred | 39.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| P2Rank | - | - | - | - | 0.845 | 0.412 |

| P2RankCONS | - | - | - | - | 0.859 | 0.452 |

| DeepPocket | - | - | - | - | 0.823 | 0.385 |

| LABind | - | - | 0.536 | 0.347 | 0.923 | 0.601 |

Performance metrics reveal substantial methodological limitations. Recall rates vary dramatically from 39% to 60%, indicating that even top-performing methods miss 40% of true binding sites [5]. The area under the precision-recall curve (AUPR) values are particularly telling, with most methods scoring below 0.5, highlighting the challenge of distinguishing true binding sites from false positives in this inherently imbalanced classification task [5] [3]. Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) values, which provide a balanced measure even for imbalanced datasets, remain modest for even advanced methods like LABind (0.347), demonstrating fundamental limitations in predictive accuracy [3].

Rescoring approaches demonstrate one path for improving method performance. When fpocket predictions are rescored by PRANK and DeepPocket, recall reaches 60% - the highest in the benchmark [5]. Similarly, implementing stronger scoring schemes improves recall by up to 14% (IF-SitePred) and precision by 30% (Surfnet) [5]. These improvements through post-prediction processing highlight the fundamental scoring challenges inherent to initial prediction algorithms.

Experimental Validation: Methodologies and Standards

Experimental determination of binding sites remains the irreplaceable gold standard for validating computational predictions. Several established experimental techniques provide high-resolution structural data essential for confirmation.

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Binding Site Validation

| Experimental Method | Resolution | Key Applications | Technical Requirements | Validation Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic (1-3 Å) | Precise atom-level ligand positioning | Protein crystallization, synchrotron access | Gold standard for binding site characterization [5] |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | Near-atomic (2-4 Å) | Large complexes, membrane proteins | Specialized sample preparation, detector | Growing importance for challenging targets |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance | Residue-level | Solution dynamics, weak interactions | Isotope labeling, spectrometer | Complementary dynamic information |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Functional impact | Binding site residue confirmation | Molecular biology facilities | Functional validation of predicted residues |

The LIGYSIS dataset exemplifies the rigorous standards required for proper validation benchmarks. Unlike earlier datasets that included 1:1 protein-ligand complexes or considered asymmetric units, LIGYSIS aggregates biologically relevant unique protein-ligand interfaces across biological units of multiple structures from the same protein [5]. This approach avoids artificial crystal contacts and redundant interfaces that can skew performance assessments. The critical importance of using biological units rather than asymmetric units is illustrated by structures like PDB: 1JQY, where the asymmetric unit contains three copies of a homo-pentamer while the biological unit comprises a single pentamer [5].

Diagram 2: Multi-technique experimental validation workflow essential for confirming computational predictions.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Binding Site Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | LIGYSIS, sc-PDB, PDBbind, HOLO4K [5] | Provide standardized testing frameworks | Method performance assessment and comparison |

| Prediction Servers | P2Rank, DeepPocket, fpocket, LABind [5] [3] | Computational binding site prediction | Initial screening and hypothesis generation |

| Structure Analysis | PyMOL, DBSCAN clustering [5] | Binding site visualization and analysis | Result interpretation and validation planning |

| Molecular Representation | ESM-2, ESM-IF1, MolFormer [5] [3] | Generate protein and ligand embeddings | Feature generation for machine learning methods |

| Validation Databases | PDBe, BioLiP, PISA [5] | Access experimentally determined structures | Experimental reference data and validation |

Specialized datasets like LIGYSIS represent crucial research resources that aggregate biologically relevant protein-ligand interfaces across multiple structures of the same protein, considering biological units rather than just asymmetric units [5]. These datasets enable more meaningful benchmarking by removing redundant protein-ligand interfaces present in earlier datasets like sc-PDB, PDBbind, binding MOAD, COACH420 and HOLO4K [5]. The protein-ligand interaction fingerprints used in LIGYSIS clustering allow identification of conserved binding modes across structural determinations [5].

Critical Analysis of Limitations and Research Gaps

Despite methodological advances, computational predictions face inherent limitations that necessitate experimental validation. Performance metrics reveal that even state-of-the-art methods achieve limited precision in identifying true binding sites, with most AUPR scores below 0.5 [5] [3]. This performance gap stems from several fundamental challenges:

First, the redundant prediction of binding sites significantly impacts reported performance metrics, inflating error rates and reducing practical utility [5]. Second, current evaluation metrics may not fully capture real-world performance requirements, leading the field to propose top-N+2 recall as a more meaningful universal benchmark [5]. Third, generalization to unseen ligands remains particularly challenging, as most methods are trained on limited ligand diversity and struggle with novel chemotypes [3].

The imbalance between binding and non-binding sites in proteins creates inherent classification challenges, with MCC and AUPR being more informative metrics in this context than overall accuracy [3]. This imbalance explains why even methods with respectable AUC values (0.8-0.9) show modest AUPR values (0.4-0.6) [5] [3]. The field has recognized that open-source sharing of both method code and benchmark implementations is essential for meaningful progress [5].

Computational methods for binding site prediction have evolved substantially from geometry-based approaches to modern ligand-aware machine learning models. While performance continues to improve, with methods like LABind demonstrating enhanced capability for generalizing to unseen ligands, significant limitations persist. Recall rates between 39-60% and precision challenges revealed by AUPR scores below 0.5 for many methods underscore that computational predictions remain approximate [5] [3].

The most effective research strategies integrate computational prediction with experimental validation, using computational methods for initial screening and hypothesis generation while relying on experimental techniques for confirmation. This integrated approach acknowledges both the power and limitations of computational methods while leveraging the respective strengths of both paradigms. As the field moves forward, more sophisticated benchmarks, standardized evaluation metrics, and increased emphasis on generalization to novel targets will be essential for advancing predictive capabilities while maintaining scientific rigor.

Defining Druggability, Cryptic Pockets, and Allosteric Sites

Core Concept Definitions

In the field of drug discovery, the precise identification and characterization of protein binding sites is a fundamental step. The concepts of druggability, cryptic pockets, and allosteric sites are central to this process, each representing a unique facet of how proteins interact with small molecules and how these interactions can be exploited for therapeutic benefit.

Druggability

Druggability describes the inherent potential of a biological target, typically a protein, to bind a drug-like molecule with high affinity. Crucially, this binding must induce a functional change that provides a therapeutic benefit [12]. The concept is most frequently applied to the binding of small molecules but has been extended to include biologic therapeutics. A target's druggability is often predicted by assessing whether it belongs to a protein family with known drug targets or, more precisely, by analyzing the physicochemical and geometric properties of its binding pockets (e.g., volume, depth, and hydrophobicity) from 3D structural data [12] [13]. It is estimated that only a small fraction of the human proteome is druggable, highlighting the need to expand this universe [12].

Cryptic Pockets

Cryptic pockets are binding sites that are not detectable in the ligand-free (apo) structure of a protein but become apparent upon a conformational change, often induced by ligand binding [14]. These pockets are "cryptic" because they are hidden in the ground state structure of the protein. They form through protein structural fluctuations and can provide druggable sites on proteins that otherwise appear undruggable [15]. Targeting cryptic pockets can offer advantages, including the potential for greater drug specificity, as these sites are often less evolutionarily conserved than traditional active sites, and the ability to overcome drug resistance [16].

Allosteric Sites

An allosteric site is a binding site on an enzyme or receptor that is topographically distinct from the active site (or orthosteric site) where the endogenous substrate or ligand binds [17] [18]. The binding of a molecule (an allosteric modulator) to this site induces a conformational change in the protein that alters its activity, either enhancing (positive modulation) or diminishing (negative modulation) its function [19] [18]. This provides a powerful mechanism for regulating protein activity without competing directly with the substrate. Allosteric modulators can offer finer control over protein function and greater specificity compared to orthosteric inhibitors [18].

Methodologies for Binding Site Prediction and Validation

A variety of computational and experimental methods are employed to predict and validate binding sites, each with its own strengths, limitations, and resource requirements.

Computational Prediction Methods

Computational tools are essential for the initial identification and assessment of potential binding sites.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Binding Site Prediction

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Workflow | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Druggability Assessment [12] [13] | Analyzes 3D protein structures to identify pockets and calculate physicochemical properties (e.g., hydrophobicity, volume). | 1. Identify cavities on the protein surface.2. Calculate geometric/physicochemical properties.3. Compare against training sets of known druggable sites (often using machine learning). | - Based on structural reality.- Can be applied to any protein with a 3D structure. | - Relies on the availability of high-quality structures.- May miss cryptic sites not present in the static structure. |

| Cryptic Pocket Prediction (PocketMiner) [15] | A graph neural network trained to predict where pockets are likely to open in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using a single static structure as input. | 1. Input a single protein structure.2. The model predicts residues likely to participate in cryptic pocket formation.3. Predictions are validated through MD simulations. | - Extremely fast (>1000x faster than simulation-based methods).- High accuracy (ROC-AUC: 0.87).- Scalable for proteome-wide screening. | - A predictive model; ultimate confirmation requires experimental validation. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations [14] [15] | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, allowing observation of transient pocket formation. | 1. Run unbiased or enhanced-sampling MD simulations (e.g., SWISH, SWISH-X) from the apo structure.2. Analyze simulation trajectories for pocket opening events.3. Identify and characterize cryptic pockets. | - Provides atomistic detail and dynamics.- Can discover novel cryptic pockets without prior knowledge. | - Computationally expensive and time-consuming.- Not feasible for high-throughput screening. |

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for identifying and validating cryptic pockets using these computational methods, leading to experimental confirmation.

Figure 1: Workflow for computational identification and experimental validation of cryptic binding sites.

Key Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions must be rigorously validated through experimental methods. The table below details common protocols used for this purpose.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Binding Site Validation

| Experimental Method | Detailed Protocol Summary | Key Data Output | Utility in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography [14] | 1. Co-crystallize the target protein with a bound small-molecule ligand (e.g., a hit from a screen).2. Solve the structure of the protein-ligand complex.3. Compare the holo (ligand-bound) structure with the apo (unbound) structure. | High-resolution 3D structure of the protein with the ligand bound in the cryptic or allosteric pocket. | - Gold standard for confirmation.- Directly shows the ligand bound in a pocket that is absent or different in the apo structure. |

| Fragment Screening [12] | 1. Screen a library of small, low-molecular-weight fragments against the protein target using biophysical techniques (e.g., NMR, Surface Plasmon Resonance).2. Identify fragments that bind, even with weak affinity.3. Solve structures of protein-fragment complexes. | Identification of fragment hits and their binding sites, often in previously unidentified pockets. | - Probes the protein's "ligandability".- Can reveal cryptic sites that open upon binding of small fragments. |

| Thiol Labeling Experiments [15] | 1. Introduce cysteine mutations at predicted cryptic site residues.2. Expose the protein to a thiol-reactive probe.3. Measure the rate of labeling; increased labeling indicates pocket opening and residue accessibility. | Quantified rate of covalent labeling for specific residues. | - Provides biochemical evidence of pocket opening in solution.- Can be used to monitor dynamics and the effects of mutations or other ligands. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents, tools, and resources used in the computational prediction and experimental validation of binding sites.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Binding Site Studies

| Item Name | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) [14] [15] | Computational Tool | Simulates protein dynamics to sample conformational states and observe transient cryptic pocket openings. |

| Pocket Detection Algorithms (e.g., Fpocket, ConCavity) [14] | Computational Tool | Automatically identifies and scores potential binding pockets on static protein structures based on geometry and chemical properties. |

| Fragment Libraries [12] [14] | Chemical Reagent | Collections of small, simple molecules used in screening to experimentally probe a protein's surface for bindable sites, including cryptic ones. |

| CryptoSite Dataset [14] | Data Resource | A curated benchmark set of proteins with known cryptic sites, used for training and testing new prediction algorithms. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [12] [14] | Data Resource | A global repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, providing essential apo and holo structures for analysis. |

| Allosteric Modulators (e.g., Cinacalcet, Maraviroc) [19] | Pharmacological Tool | Small molecules that bind to allosteric sites; used to experimentally probe and validate allosteric site function and therapeutic potential. |

The relationship between different binding site types and their modulation strategies can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Functional relationships between orthosteric sites, allosteric sites, and cryptic pockets, and their respective ligands. Cryptic pockets are shown as transient (dashed) and can sometimes act as allosteric sites.

From In Silico to In Vitro: Methodologies and Integrated Workflows

The accurate prediction of ligand-binding sites on proteins is a critical frontier in modern drug discovery. Validating these computational predictions against experimental data forms the core thesis of ongoing research, aiming to bridge the gap between in silico models and biological reality. Computational methods have evolved into three principal categories: geometry-based approaches that identify pockets based on protein structure, machine learning (ML) methods that learn patterns from vast biological datasets, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that capture the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions at atomic resolution [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these tools, focusing on their performance, underlying methodologies, and, crucially, their validation against experimental data to guide researchers in selecting and applying the most appropriate strategies for drug development.

Method Categories and Core Principles

Understanding the fundamental principles of each method category is essential for selecting the right tool and interpreting its predictions correctly. The following table summarizes the core principles, strengths, and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Core Principles of Prediction Method Categories

| Method Category | Fundamental Principle | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry-Based | Identifies surface cavities and pockets based on the 3D protein structure's shape and topography. | Fast computation; intuitive results; no training data required. | Static view; cannot confirm functional relevance or druggability. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Learns complex relationships between protein sequence/structure features and binding sites from large datasets. | High accuracy for known protein folds; can integrate diverse feature sets. | Performance depends on training data quality and representativeness. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, capturing dynamic binding processes. | Models protein flexibility and solvent effects; provides energetic insights. | Extremely high computational cost; limited timescale accessibility. |

A significant epistemological challenge across all methods is their reliance on experimentally determined protein structures, which may not fully represent the thermodynamic environment controlling protein conformation at functional sites [11]. Furthermore, proteins are not static; the "dynamic reality of proteins in their native biological environments" means that the millions of conformations flexible proteins can adopt are poorly represented by single, static models [11]. This is particularly true for short peptides, which are highly unstable, where studies show that different algorithms (e.g., AlphaFold, PEP-FOLD) have complementary strengths depending on the peptide's properties [20].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Prediction Tools

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Tool performance is typically measured by accuracy, precision, recall, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC). The most critical validation, however, comes from benchmarking against experimentally determined structures from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and through experimental confirmation of novel predictions.

For instance, in epitope prediction, a deep learning model for B-cell epitopes achieved an ROC AUC of 0.945, significantly outperforming traditional tools [9]. Similarly, the MUNIS model for T-cell epitope prediction demonstrated a 26% higher performance than the best prior algorithm, with its predictions successfully validated through in vitro HLA binding and T-cell assays [9].

In binding affinity predictions, a re-engineered Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) method applied to G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) showed a strong correlation with experimental binding affinity data (pKD), with an R² value of 0.7893 for agonists bound to the β1 adrenergic receptor [8].

Comparative Tool Analysis

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of representative tools and methodologies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Prediction Tools and Methods

| Tool / Method | Category | Reported Performance | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MUNIS [9] | ML (T-cell epitope) | 26% higher performance than prior best algorithm | Identification of known/novel epitopes via HLA binding & T-cell assays |

| NetBCE [9] | ML (B-cell epitope) | ROC AUC ~0.85 | Cross-validation benchmarks against established datasets |

| BAR-MD [8] | MD (Binding Affinity) | R² = 0.79 vs. exp. pKD | Correlation with measured orthosteric binding affinities for GPCRs |

| AlphaFold [20] | ML (Structure) | High accuracy for compact structures | Comparative MD simulation stability studies [20] |

| PEP-FOLD [20] | De novo (Peptide) | Compact, stable dynamics for short peptides | MD simulation analysis over 100 ns [20] |

| GraphBepi [9] | ML (B-cell epitope) | Reveals previously overlooked epitopes | Experimentally confirmed identification of functional epitopes |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Rigorous experimental validation is the cornerstone of establishing the reliability of any computational prediction. The following workflows outline standard protocols for validating binding site and binding affinity predictions.

Protocol 1: Binding Site and Epitope Validation

This workflow is common for validating predicted protein-ligand binding sites or B-cell epitopes.

Protocol 2: Binding Affinity Validation via MD

This protocol details the process of using MD simulations and free energy calculations to predict binding affinity, followed by experimental correlation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful prediction and validation require a suite of computational and wet-lab reagents. The following table details key solutions for the featured field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Prediction and Validation

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [8] | A molecular dynamics package for simulating Newtonian equations of motion for systems with hundreds to millions of particles. | Used as the simulation engine for MD-based binding free energy calculations and trajectory analysis. |

| CHARMM/AMBER [8] | Biomolecular force fields defining parameters for potential energy functions in MD simulations. | Provide the physical rules governing atomic interactions in MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes. |

| BAR (Bennett Acceptance Ratio) Module [8] | An algorithm for calculating free energy differences between two states using data from MD simulations. | The core computational method for calculating binding free energies from simulation trajectories. |

| GPCR-Containing Lipid Bilayer | A pre-assembled membrane system mimicking the native environment of membrane proteins like GPCRs. | Essential for running physiologically relevant MD simulations of membrane protein targets [8]. |

| Competitive Binding Assay Kit | A biochemical kit to measure the inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) or equilibrium constant (Kᵢ) of a ligand. | Provides the critical experimental data for validating computational binding affinity predictions [8]. |

Integrated Workflows and Future Directions

The future of computational binding site prediction lies not in relying on a single method, but in developing integrated workflows that combine the strengths of different approaches. For example, a common strategy uses a coarse-grained but fast geometry-based or ML method to identify potential binding pockets, which are then refined and evaluated with more computationally intensive, high-fidelity methods like MD simulations [2].

Key future trends include:

- AI and Deep Learning Integration: The use of advanced neural networks like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) is becoming pervasive. These models can handle both sequence and 3D structural data, with tools like GraphBepi using GNNs to achieve state-of-the-art performance by modeling proteins as interaction graphs [9].

- Handling of Dynamic and Allosteric Sites: Increasing focus is being placed on predicting cryptic and allosteric sites, which are not apparent in static crystal structures but can be revealed through MD simulations, offering novel therapeutic opportunities [2].

- Multiscale Simulation Methodologies: To overcome the computational cost of MD, future research is focusing on coupling MD with coarse-grained simulations and integrating machine learning as surrogate models to rapidly predict physical fields, a concept gaining traction in other fields like CFD [21] [22].

In conclusion, while geometry-based and ML tools offer speed and scalability for initial screening, MD simulations provide the most physiologically realistic and thermodynamically rigorous predictions, as evidenced by their strong correlation with experimental binding data [8]. The choice of tool must be aligned with the research question, stage of the project, and available resources, with experimental validation remaining the non-negotiable standard for confirming any computational insight.

In the rapidly advancing field of computational structural biology, the development of accurate predictive models for protein-ligand interactions and binding sites represents a central focus. Powerful AI-driven tools like AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold have revolutionized our ability to predict protein structures with remarkable accuracy [23] [24]. However, these computational predictions, particularly for complex phenomena like binding sites and protein-protein interactions, require rigorous experimental validation to confirm their biological relevance and accuracy. This validation process relies on a suite of established biophysical techniques that provide complementary information about protein structure, dynamics, and interactions. Among these, X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) have emerged as foundational methods in the structural biologist's toolkit. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three techniques, focusing on their respective strengths, limitations, and applications in validating computational predictions, with particular emphasis on their use in drug discovery and biomedical research.

Comparative Analysis of Key Techniques

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three primary techniques used for experimental validation of computational predictions.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Experimental Validation Techniques

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange MS (HDX-MS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Atomic-resolution static 3D structure | 3D shape, architecture of large complexes | Protein dynamics, solvent accessibility, conformational changes |

| Typical Resolution | Atomic (~1-3 Å) | Near-atomic to low-resolution (~3-20 Å) | Peptide-level (5-20 amino acids) |

| Sample Requirements | High-purity, crystallizable protein | High-purity, particle-oriented complexes | Moderate purity, solution conditions |

| Throughput | Low (days to months) | Medium (days to weeks) | High (hours to days) [25] [26] |

| Sample Consumption | Low (µg per crystal) | Low (µg for grid preparation) | Very low (µL of µM sample) [25] [26] |

| Key Advantage | Highest resolution structural data | Handles large, heterogeneous complexes; no crystallization needed | Probes solution-phase dynamics under physiological conditions [24] [27] |

| Main Limitation | Requires crystallization; static snapshot | Resolution can be variable; complex data processing | No 3D structural models; indirect structural probe |

| Ideal for Validating | Precise atomic-level ligand interactions, side-chain conformations | Overall architecture of large complexes, conformational states | Binding interfaces, allosteric effects, conformational dynamics [25] |

Detailed Methodologies and Workflows

X-Ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography remains the gold standard for determining high-resolution protein structures. The workflow begins with protein purification and crystallization, where the protein is precipitated into a highly ordered crystal lattice. This crystal is then exposed to a high-energy X-ray beam, producing a diffraction pattern. The intensities of the diffracted spots are measured and used to calculate an electron density map through Fourier transformation. Researchers then build and refine an atomic model into this electron density, optimizing its fit and validating the final structure against geometric constraints [23].

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Single-particle cryo-EM has emerged as a powerful technique for determining the structures of large macromolecular complexes that are difficult to crystallize. The sample, in solution, is applied to a grid and rapidly vitrified in liquid ethane, preserving its native state in a thin layer of amorphous ice. An electron microscope then collects thousands of two-dimensional projection images of individual particles trapped in random orientations. Computational algorithms perform class averaging, alignment, and 3D reconstruction to generate a three-dimensional density map [23] [27]. Recent advances in direct electron-detection cameras and processing software have dramatically improved the resolution and accessibility of this technique [27].

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS)

HDX-MS probes protein structure and dynamics by measuring the exchange of backbone amide hydrogens with deuterium atoms from the solvent. The typical workflow involves diluting the protein of interest into a deuterated buffer (D₂O) and allowing labeling to proceed for various time points (seconds to hours). The reaction is then quenched by lowering the pH and temperature, which minimizes back-exchange. The protein is subsequently digested using an immobilized protease (like pepsin), and the resulting peptides are separated by liquid chromatography and analyzed by mass spectrometry to determine the location and extent of deuterium incorporation [25] [28]. A critical application is epitope mapping, where the deuterium uptake of an antigen alone is compared to its uptake when bound to an antibody; a reduction in uptake in the complex state identifies the binding interface [25] [26].

Figure 1: HDX-MS Experimental Workflow. The workflow shows the key steps from deuterium labeling to data processing, highlighting the solution-phase nature of the experiment.

Integrated Approaches for Robust Validation

The most powerful validation strategies combine multiple experimental techniques, leveraging their complementary strengths.

HDX-MS with Cryo-EM: While cryo-EM provides an overall 3D shape, HDX-MS offers complementary information on protein dynamics and flexibility in solution. This combination is particularly valuable for analyzing conformational heterogeneity, allosteric mechanisms, and for validating that the static cryo-EM model reflects the solution-state behavior [27]. For instance, a study of a transcription initiation factor combined HDX-MS and cryo-EM to reveal an allosteric structural change that was not apparent from the cryo-EM structure alone [26].

HDX-MS with X-ray Crystallography: X-ray crystallography provides a definitive, high-resolution structural framework. HDX-MS data can validate the physiological relevance of a crystal structure by confirming that regions observed as flexible or ordered in the crystal exhibit similar behavior in solution. It can also identify dynamic regions that may be missing from the crystal structure due to disorder [26].

HDX-MS with Cross-Linking MS (XL-MS): XL-MS provides explicit distance restraints between specific residues, which can pinpoint exact interacting residues when combined with the broader binding interface information from HDX-MS. Their integration allows for the generation of more precise, high-confidence models of protein interfaces for computational docking [23] [25].

AI-Driven Predictions with Experimental Data: The emergence of deep learning models like AI-HDX, which predicts intrinsic HDX rates from protein sequence, demonstrates a new integrative paradigm [24]. Furthermore, HDX-MS data is increasingly used to guide and validate computational protein-protein docking, helping to solve the sampling and scoring problems associated with predicting complex interfaces [25] [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimental validation depends on high-quality reagents and specialized instrumentation. The following tables detail key solutions required for these techniques.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Mass Spectrometry-Based Techniques

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Labeling solvent for HDX-MS; source of deuterium atoms for exchange with protein backbone amides [28]. |

| Quench Buffer (Low pH) | Stops the HDX reaction (e.g., pH 2.5, 0 °C) and denatures the protein for digestion [25] [28]. |

| Immobilized Pepsin | Acid-stable protease used to digest the labeled protein into peptides for LC-MS analysis, minimizing back-exchange [25]. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | Reducing agent added during quenching to break disulfide bonds in antibodies, making them more susceptible to proteolysis [25] [26]. |

Table 3: Key Solutions for Structural Biology Techniques

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Crystallization Screen Solutions | Sparse matrix of chemical conditions to identify optimal parameters for protein crystal growth. |

| Cryo-Protectants | Solutions (e.g., glycerol, sugars) used to prevent ice crystal formation during vitrification for cryo-EM. |

| Affinity Purification Resins | For sample preparation (e.g., co-immunoprecipitation, affinity purification) to isolate complexes for all techniques [23]. |

| Heterobifunctional Cross-linkers | Chemicals (e.g., DSSO) used in XL-MS to covalently link proximal amino acids, providing distance constraints [23]. |

X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, and HDX-MS each provide unique and critical information for the experimental validation of computational predictions. The choice of technique is not a matter of selecting a single "best" method, but rather of understanding their complementary roles. X-ray crystallography offers unparalleled atomic detail, cryo-EM reveals the architecture of massive complexes, and HDX-MS provides unique insights into solution-phase dynamics and interactions. The most robust validation strategies adopt an integrative approach, combining data from these and other biophysical techniques to build a comprehensive and accurate picture of protein structure and function. This multi-faceted experimental validation is indispensable for advancing computational biology and accelerating drug discovery.

The accurate computational prediction of transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) and protein-ligand interfaces represents a cornerstone of modern molecular biology. However, the critical validation of these predictions requires demonstrating their functional relevance through direct experimentation. Site-directed mutagenesis serves as the crucial methodological bridge connecting in silico predictions with in vitro and in vivo biological activity, enabling researchers to move beyond mere correlation to establish causal relationships. This guide examines how functional assays, when coupled with targeted mutagenesis, provide the experimental framework for testing computational predictions across various biological contexts, from DNA-protein interactions to small molecule binding.

The fundamental premise is straightforward: if a predicted binding site is functionally important, then its deliberate disruption should produce a measurable change in biological activity. This principle finds application across diverse fields, including transcriptional regulation studies, enzyme mechanism analysis, and therapeutic development. By systematically comparing outcomes from different experimental approaches, researchers can objectively assess which computational models most accurately predict biologically relevant interactions, ultimately refining prediction algorithms and advancing our understanding of molecular recognition events.

Core Methodologies: Experimental Paradigms for Validation

Site-Directed Mutagenesis Techniques

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) encompasses several laboratory techniques for introducing specific alterations into known DNA sequences. These methods share the common principle of using artificially synthesized primers containing desired mutations to amplify the gene of interest during polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Site-Directed Mutagenesis Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Primary Application | Key Reagent Requirements | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional PCR | Single mutagenic primer with mismatch incorporated during amplification | Introducing point mutations or small insertions | Taq DNA polymerase (lacks exonuclease activity), mutagenic primers | Lower yield due to mixed DNA types; suitable for 2-3 nucleotide changes [29] |

| Primer Extension (Nested PCR) | Two rounds of PCR with nested mutagenic primers | Introducing specific mutations with higher efficiency | Two sets of primers (outer and inner), high-fidelity DNA polymerase | Higher specificity; inner primers contain desired mutations [29] |

| Inverse PCR | Primers oriented outward to amplify entire plasmid | Deletion mutagenesis or circular plasmid modification | High-fidelity DNA polymerase, phosphorylated ends for ligation | Ideal for deleting sequences from plasmids; reverses amplification orientation [29] |

Functional Assay Platforms

Following mutagenesis, functional assays quantify the biological consequences of disrupting predicted binding sites. These assays measure specific molecular outputs to determine if computational predictions correspond to functionally significant regions.

Reporter Gene Assays measure transcriptional activity by fusing putative regulatory sequences to easily quantifiable reporter genes like luciferase. These assays directly test whether predicted transcription factor binding sites actually influence gene expression. In a landmark study, researchers predicted and mutagenized 455 binding sites in human promoters and tested them in four immortalized human cell lines using transient transfections with a luciferase reporter system. Between 36% and 49% of binding sites made a functional contribution to promoter activity in each cell line, with an overall functional validation rate of 70% across all lines [30].

Transcription Activation Assays in specialized systems like yeast provide controlled environments for assessing the functional impact of mutations. For example, a functional assay for BRCA1 combined site-directed and random mutagenesis with a transcription assay in yeast to identify critical residues in the COOH-terminal region. This approach revealed that hydrophobic residues conserved across species were essential for transcription activation function, and that the integrity of BRCT domains was crucial for this activity [31].

Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiling utilizes techniques like Peptide-centric Local Stability Assay (PELSA) to detect interactions between proteins and small molecules. The high-throughput adaptation HT-PELSA identifies protein regions stabilized by ligand binding through limited proteolysis, enabling the characterization of binding affinities for hundreds of proteins simultaneously. This method can precisely determine binding affinities (EC₅₀ values) and identify both stabilized and destabilized regions upon ligand binding [32].

Comparative Experimental Data: Validating Predictions Across Systems

Table 2: Functional Validation Rates of Predicted Transcription Factor Binding Sites

| Transcription Factor | Predicted Sites Tested | Functional Validation Rate | Key Functional Outcomes | Conservation Pattern of Functional Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTCF | 455 total across factors | 70% overall in any cell line | Transcriptional activation or repression | Higher evolutionary conservation [30] |

| GABP | Part of 455 site dataset | 36-49% per cell line | Primarily transcriptional activation | Closer to transcriptional start sites [30] |

| GATA2 | Part of 455 site dataset | Varies by cell type | Context-dependent regulation | Higher sequence conservation [30] |

| E2F | Part of 455 site dataset | Cell-line dependent | Cell cycle regulation | Distinct positioning patterns [30] |

| YY1 | Part of 455 site dataset | Functionally diverse | Both activation and repression | Distinct motif variations for different functions [30] |

Table 3: Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiling Performance Metrics

| Profiling Method | Targets Identified | Sensitivity/Specificity | Key Applications | Throughput Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-PELSA | 301 E. coli ATP-binding proteins | 58-61% specificity for ATP binders | Mapping binding regions, determining affinities | 100x improvement over standard PELSA [32] |

| Kinobead Competition | Kinase-focused | Benchmark for affinity measurements | Kinase inhibitor profiling | Lower throughput for broad applications [32] |

| Limited Proteolysis-Mass Spectrometry | 66-84 ATP binders | 36-41% specificity | Identifying ligand stabilization effects | Moderate throughput [32] |

Integrated Workflow: From Prediction to Functional Validation

The complete experimental pipeline for validating predicted binding sites involves sequential steps from computational prediction through functional interpretation. The diagram below illustrates this integrated workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Binding Site Validation

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Mutagenesis and Functional Assays

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Pfu, Vent, Phusion | High-fidelity amplification for mutagenesis | Require 3' to 5' exonuclease activity; must lack 5' to 3' exonuclease activity [29] |

| Specialized Primers | Mutagenic primers with specific mismatches | Introduce targeted mutations during PCR | Optimal length: 22-25 nucleotides; mutation placement at 5' end or middle with 11 complementary bases on both sides [29] |

| Template DNA | Circular plasmid DNA (0.1-1.0 ng/μl) | Carrier of gene of interest for mutagenesis | Must be highly purified; DMSO recommended for high GC content [29] |

| Nucleases | Methylation-specific endonucleases | Cleave methylated template DNA post-mutagenesis | Selectively removes original template, enriching for mutant alleles [29] |

| Reporter Systems | Luciferase, fluorescent proteins | Quantify transcriptional activity in functional assays | Provide sensitive, quantitative readouts of promoter activity [30] |

| Cell Lines | MCF-7, 22Rv1/MMTV_GR-KO, K562 | Provide biological context for functional tests | Selected based on relevance to biological question; 22Rv1 used for androgen receptor transactivation assays [33] |

Case Studies: Integrated Approaches in Practice

Large-Scale Transcription Factor Binding Site Analysis

A comprehensive functional analysis of transcription factor binding sites in human promoters exemplifies the power of combining computational predictions with experimental validation. Researchers predicted 455 binding sites using ENCODE ChIP-seq data combined with position weight matrix searches, then tested these predictions through systematic mutagenesis and luciferase reporter assays in four human cell lines. The study revealed that functional binding sites demonstrated higher evolutionary conservation and were located closer to transcriptional start sites, providing critical insights for improving prediction algorithms. Additionally, the research identified that transcription factor binding resulted in transcriptional repression in more than one-third of functional sites, challenging simplistic assumptions about activator/repressor classifications [30].

Protein-Ligand Interaction Mapping with HT-PELSA

The development of High-Throughput Peptide-centric Local Stability Assay (HT-PELSA) demonstrates advanced methodology for validating protein-ligand interactions. This approach detects protein regions stabilized by ligand binding through limited proteolysis, enabling system-wide identification of binding sites. In one application, researchers characterized ATP-binding affinities for 301 Escherichia coli proteins, identifying 1,426 stabilized peptides with 71% corresponding to UniProt-annotated ATP binders. The method showed substantially improved coverage and specificity compared to previous techniques, accurately determining binding affinities that closely aligned with gold-standard kinobead competition assays [32].

Estrogen Receptor-Flavonoid Interactions

Molecular modeling combined with functional assays elucidated the complex interactions between naturally occurring flavonoids and estrogen receptor α (ERα). Researchers employed docking studies with ERα ligand binding domains (3ERT and 1GWR) followed by molecular dynamics simulations to predict binding modes. They then experimentally validated these predictions through cell viability assays, progesterone receptor expression analysis, and ERE-driven reporter gene expression in ERα-positive MCF-7 cells. This integrated approach revealed that epicatechin, myricetin, and kaempferol exhibited estrogenic potential at 5 μM concentration, demonstrating how computational predictions guide functional experimental design [34].

The integration of computational predictions with rigorous functional assays through targeted mutagenesis represents a powerful paradigm for advancing molecular biology. The experimental approaches compared in this guide demonstrate that functional validation remains indispensable for distinguishing biologically relevant binding sites from computational artifacts. As prediction algorithms continue to improve, incorporating experimental feedback regarding functional relevance – including quantitative measures of binding affinity, transcriptional outcomes, and cellular context dependencies – will further refine our ability to accurately model biological systems.

The most effective research strategies employ complementary validation methods tailored to specific biological questions, whether investigating DNA-protein interactions, small molecule binding, or allosteric regulation. By systematically correlating predicted sites with biological activity through mutagenesis, researchers can both validate specific predictions and contribute to the broader goal of developing more accurate computational models that truly reflect biological reality.

The accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding sites is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and protein function analysis. While computational methods have advanced significantly, their true value emerges only through rigorous validation against experimental data. This guide explores the establishment of a robust validation pipeline for binding site predictions, providing a structured workflow from initial computational prediction to experimental confirmation. We frame this discussion within the broader thesis that reliable computational predictions must be grounded in and validated by empirical evidence to be truly useful in biological research and therapeutic development.

The critical importance of such validation pipelines is underscored by the proliferation of prediction methods—over 50 methods have been developed over the past three decades, with a notable paradigm shift from geometry-based to machine learning approaches [5]. With such diversity in methodologies, establishing standardized validation workflows becomes essential for comparing tool performance and assessing their real-world applicability.

Comparative Performance of Binding Site Prediction Methods

To objectively evaluate the current landscape of binding site prediction tools, we analyze performance data from recent large-scale benchmarks. The following table summarizes key metrics for prominent methods assessed against the LIGYSIS dataset, a comprehensive curated collection of protein-ligand interfaces that improves upon earlier datasets by considering biological units and aggregating multiple structures from the same protein [5].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ligand Binding Site Prediction Methods

| Method | Approach Category | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fpocketPRANK | Combined (Geometry + ML Rescoring) | 60 | - | fpocket predictions re-scored with PRANK |

| DeepPocket | Machine Learning | 60 | - | Convolutional neural networks on grid voxels |

| P2Rank | Machine Learning | - | - | Random forest on solvent accessible surface points |

| IF-SitePred | Machine Learning | 39 | - | ESM-IF1 embeddings with LightGBM classifiers |

| Surfnet | Geometry-based | - | +30 (with rescoring) | Identifies cavities via molecular surface geometry |

| VN-EGNN | Machine Learning | - | - | Virtual nodes with equivariant graph neural networks |

| PUResNet | Machine Learning | - | - | Deep residual and convolutional neural networks |

| GrASP | Machine Learning | - | - | Graph attention networks on surface protein atoms |

The data reveals substantial variation in performance across methods. Re-scoring approaches like fpocketPRANK and DeepPocket achieve the highest recall at 60%, while IF-SitePred shows considerably lower recall at 39% [5]. Importantly, the benchmark demonstrates that redundant prediction of binding sites negatively impacts performance, while stronger pocket scoring schemes can improve recall by up to 14% and precision by 30% [5].

Beyond these general methods, newer approaches like LABind show particular promise by incorporating ligand information directly into their architecture. LABind utilizes a graph transformer to capture binding patterns and a cross-attention mechanism to learn distinct binding characteristics between proteins and ligands [3]. This "ligand-aware" approach demonstrates superior performance across multiple benchmark datasets and improves generalization to unseen ligands [3].

Table 2: Advanced Metrics for Modern Binding Site Prediction Methods

| Method | MCC | AUPR | AUC | DCC (Å) | Ligand Awareness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LABind | High | High | High | Low | Yes (explicit) |