Combinatorial Optimization in Protein Folding: A Comparative Analysis of Algorithms for Structure Prediction and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of combinatorial optimization approaches for solving the complex challenge of protein structure prediction.

Combinatorial Optimization in Protein Folding: A Comparative Analysis of Algorithms for Structure Prediction and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of combinatorial optimization approaches for solving the complex challenge of protein structure prediction. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, from the thermodynamic hypothesis of folding to the computational hurdles of navigating vast conformational spaces. The analysis delves into specific methodologies, including genetic algorithms, fragment assembly, and innovative hierarchical assembly techniques like CombFold, while contrasting them with emerging deep learning models such as AlphaFold2. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for managing resource constraints and sampling limitations, and validates approaches through performance benchmarking and adversarial testing. By synthesizing insights across these domains, this review aims to guide the selection and refinement of computational strategies to accelerate biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Protein Folding Problem and the Combinatorial Challenge

Protein folding, the process by which a polypeptide chain attains its functional three-dimensional structure, is a fundamental biological phenomenon with direct implications for cellular viability and disease pathogenesis. The precise native structure of a protein dictates its specific functions, including catalysis, signal transduction, and molecular recognition. Conversely, protein misfolding can lead to loss of function or gain of toxic function, contributing to severe pathological conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Understanding and predicting protein folding has therefore emerged as a critical frontier in molecular biology and drug development. This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary computational approaches for protein folding research, with a specific focus on combinatorial optimization strategies that are reshaping our ability to predict and design protein structures.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and data resources critical for protein folding research.

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application in Protein Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [1] | Deep Learning Model | High-accuracy protein structure prediction from sequence | Predicts single-chain and multichain protein structures; serves as a core engine for complex assembly |

| CombFold [1] | Combinatorial Assembly Algorithm | Predicts structures of large protein complexes | Hierarchically assembles large complexes using pairwise subunit interactions from AlphaFold2 |

| ACPro Database [2] | Curated Experimental Database | Repository of verified experimental protein folding kinetics data | Provides high-quality data for training and testing predictive computational models |

| Bayesian Optimization [3] | Optimization Framework | Efficiently searches protein sequence space for inverse folding | Identifies amino acid sequences that fold into a desired structure with high accuracy |

| Color-Coding Methods [4] | Graph Theory Algorithm | Identifies linear pathways in protein interaction networks | Detects biologically significant signaling pathways by analyzing network topology |

Performance Comparison of Computational Approaches

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of different computational strategies, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations in addressing the protein folding problem.

| Method / Approach | Core Principle | Key Performance Metric | Reported Performance / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CombFold [1] | Combinatorial & hierarchical assembly of pairwise AF2 predictions | Top-10 success rate (TM-score >0.7) on large heteromeric assemblies | 72% on datasets of 60 large, asymmetric assemblies |

| AlphaFold-Multimer (AFM) [1] | Deep learning for multimeric complexes | Success rate for complexes of 2-9 chains | 40-70%; challenged by large assemblies (>1,800-3,000 aa) due to GPU memory limits |

| Generative Models (Inverse Folding) [3] | Conditional generation of sequences from a backbone | Sequence recovery and structural fidelity | Rapid generation but may produce sequences that fail to fold reliably |

| Optimization (Inverse Folding) [3] | Iterative refinement of sequences against a target | Structural error (TM-score, RMSD) | Reduced structural error vs. generative models; handles constraints |

| Machine Learning (Folding Rate) [5] | Prediction of protein folding rates from sequence | Correlation between predicted and actual log folding rates | Claims of >90% correlation, but overfitting leads to lower power (~0.63) on new data |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CombFold Protocol for Large Complex Assembly

CombFold utilizes a combinatorial assembly algorithm to predict the structures of large protein complexes that are challenging for deep learning models like AlphaFold2 alone. The experimental workflow consists of three major stages [1]:

Stage 1: Generation of Pairwise Subunit Interactions

- Input: Subunit sequences (single chains or domains).

- Procedure: AlphaFold2 (or AlphaFold-Multimer) is run on all possible pairs of subunit sequences. Additionally, for each subunit, small subcomplexes (3-5 subunits) are predicted by including its highest-confidence interaction partners.

- Output: Multiple structural models for each subunit pair and small subcomplex.

Stage 2: Unified Representation

- Procedure: A single representative structure is selected for each subunit, typically the one with the highest average predicted local Distance Difference Test (plDDT) score. For every interacting pair of subunits found in the AlphaFold2 models, the spatial transformation (rotation and translation) between their representative structures is calculated.

- Output: A set of N representative subunit structures and a list of scored pairwise transformations between them.

Stage 3: Combinatorial Assembly

- Procedure: The complex is built hierarchically over N iterations. In each iteration, larger subcomplexes are constructed by merging smaller ones using the pre-computed transformations. The algorithm explores different assembly pathways combinatorially. Optionally, distance restraints from experiments like crosslinking mass spectrometry can be integrated to guide the assembly.

- Output: A set of top-ranked, fully assembled complex structures.

Bayesian Optimization for Inverse Protein Folding

This protocol reframes the inverse protein folding problem—finding a sequence that folds into a given structure—as an optimization challenge [3].

- Objective: To identify an amino acid sequence (X) that minimizes the structural deviation between its predicted folded structure and a target backbone structure (Y).

- Algorithm: Deep Bayesian Optimization.

- Workflow:

- Initialization: Start with a set of candidate sequences, which can be generated randomly or from a generative model.

- Evaluation: For each candidate sequence, a computational folding model (like AlphaFold2) is used to predict its 3D structure. The deviation from the target structure (e.g., measured by RMSD or TM-score) is calculated.

- Optimization Loop:

- A statistical surrogate model (a Bayesian probabilistic model) is updated with the sequence-structure deviation data.

- The Bayesian optimizer uses this model to select the most promising sequences to evaluate next, balancing exploration of uncertain regions and exploitation of known promising areas.

- The selected sequences are evaluated (folded and scored), and the data is used to update the surrogate model.

- Termination: The loop continues for a fixed number of iterations or until a sequence with satisfactory structural accuracy is found.

- Output: A refined amino acid sequence predicted to fold into the target backbone with high fidelity.

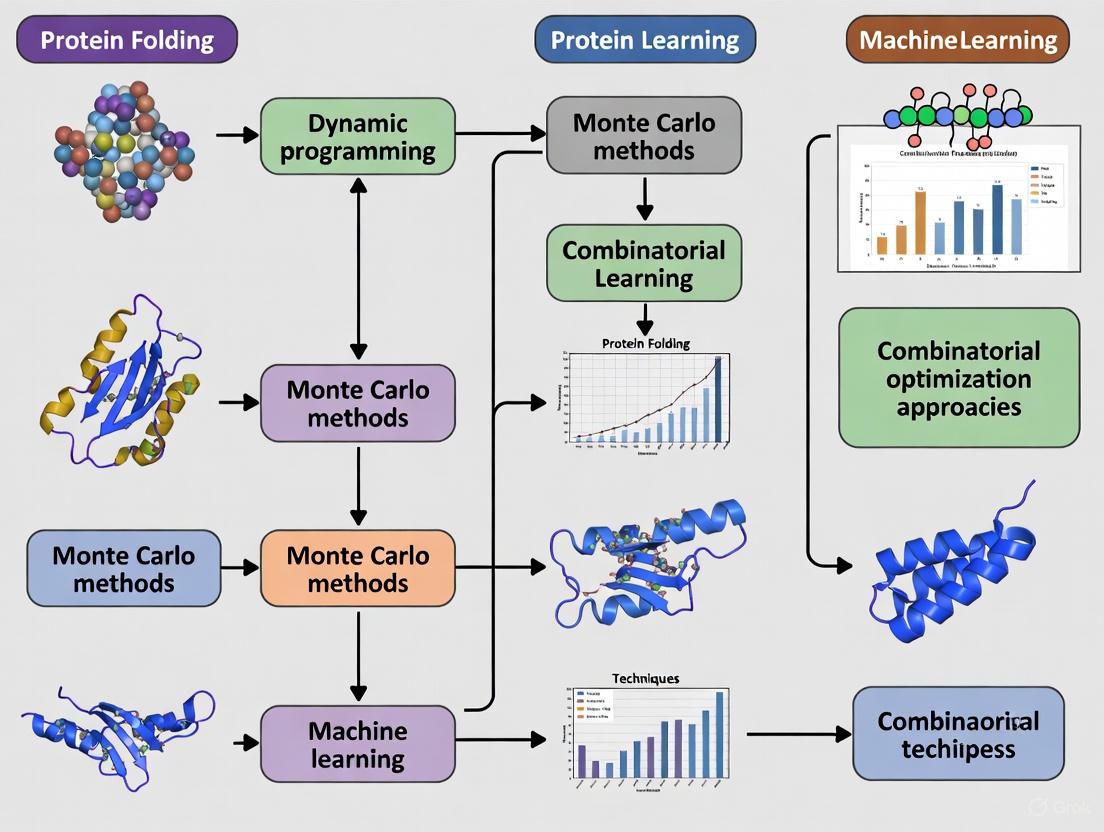

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: CombFold Assembly Workflow

Diagram 2: Inverse Folding as Optimization

The comparative analysis reveals that no single computational approach holds a monopoly on solving the diverse challenges within protein folding research. Instead, a synergistic strategy that leverages the strengths of each method is emerging as the most powerful path forward.

Deep learning models like AlphaFold2 provide unprecedented accuracy in predicting static structures of single chains and small complexes, serving as a foundational tool [1]. However, their limitations in handling very large assemblies and generating diverse solutions create opportunities for combinatorial algorithms like CombFold, which can piece together these smaller predictions into accurate models of massive cellular machines [1]. Similarly, for the inverse problem of protein design, purely generative models offer speed and a broad exploration of sequence space, but they can be complemented by optimization-based approaches like Bayesian optimization, which deliver higher precision and the ability to incorporate specific design constraints [3].

The field must also contend with the challenge of data quality and model overfitting. The development of curated, high-confidence databases like ACPro is crucial for robust model training and validation [2]. Furthermore, as evidenced by performance drops in folding rate predictors, claims of extreme accuracy must be rigorously validated against independent datasets to avoid the pitfalls of overfitting, ensuring models generalize well to new biological problems [5].

In conclusion, the biological imperative of protein folding for health and disease is now matched by a computational imperative to intelligently integrate diverse strategies. The future of protein folding research and its application in drug development lies not in choosing a single winner among algorithms, but in building integrated pipelines that combine the scale of deep learning, the logical assembly of combinatorial optimization, and the precision of Bayesian search to fully unravel the relationship between sequence, structure, function, and dysfunction.

The protein folding problem represents one of the most significant challenges in modern computational biology. Given a linear sequence of amino acids, a protein can theoretically fold into an astronomically large number of possible three-dimensional structures [6]. This vast conformational space arises from the enormous degrees of freedom available to even a small polypeptide chain, creating a combinatorial explosion that makes exhaustive search for the native state—the biologically active conformation—computationally infeasible [6]. This dichotomy between the rapid folding of natural proteins and the computational intractability of searching all possible configurations is known as the Levinthal paradox [6], which has inspired the development of sophisticated combinatorial optimization approaches to navigate this complex landscape efficiently. Within the broader thesis on combinatorial optimization for protein folding research, this guide objectively compares the performance of leading computational strategies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

The fundamental challenge stems from the fact that the native structure of a protein is postulated to be the configuration with the minimum free energy, according to Christian B. Anfinsen's thermodynamic hypothesis [6]. However, the energy landscape provided by elaborated energy functions is typically rugged rather than perfectly funnel-shaped, causing search algorithms to frequently become trapped in local minima [6]. This review systematically compares the dominant optimization frameworks—from genetic algorithms and constraint programming to distributed computing and hybrid approaches—evaluating their performance against experimental benchmarks and highlighting their respective strengths in confronting the combinatorial explosion inherent to protein structure prediction.

Comparative Analysis of Combinatorial Optimization Approaches

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Protein Folding Optimization Algorithms

| Optimization Approach | Typical Search Space Reduction | Reported Speed Advantage | Accuracy vs. Native Structure | Experimental Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm with Non-Uniform Scaling [6] | Significant conformational space exploration | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods | Qualitative differences/similarities to native structures | Standard benchmark protein sequences |

| Distributed Computing Molecular Dynamics [7] | N/A (explicit dynamics) | Convergence in ~700 μs simulation | Excellent agreement with experimental folding times & equilibrium constants | Laser temperature-jump experiments |

| Constraint Programming with Local Search [6] | Compact structures via CSP | Effective for small/medium proteins | Acceptable quality for larger proteins | HP model with BM energy model |

| Hybrid Methods (Constraint Programming + SA) [6] | Two-stage optimization | State-of-the-art for small proteins | High-quality structures | Benchmark against known structures |

Evaluating the effectiveness of protein folding optimization approaches requires multiple performance metrics. The number of objective function evaluations serves as a key comparison metric for algorithmic efficiency [6], while quantitative agreement with experimental folding parameters provides validation against empirical data [7]. For instance, distributed computing implementations have achieved remarkable accuracy, with computational predictions showing excellent agreement with experimentally determined mean folding times and equilibrium constants [7]. Meanwhile, genetic algorithms employing non-uniform scaled energy functions have demonstrated superior exploration of conformational space regions that previous methods failed to sample [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Optimization Methods

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Combinatorial Optimization Techniques

| Method Category | Representative Techniques | Computational Complexity | Scalability to Large Proteins | Information Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio with Knowledge-Based Functions [6] | Non-uniform scaled 20×20 pairwise function | High but tractable | Limited for large proteins | 20×20 pairwise information overcomes HP limitations |

| Discrete Lattice Models [6] | Genetic algorithms on lattices | Reduced complexity | Better scalability | Integrates real energy information in simplified model |

| Distributed Dynamics [7] | Thousands of molecular trajectories | Extremely high (700 μs total) | Limited to small proteins | Direct physical simulation without knowledge-based potentials |

| Cross-Linking with Optimization [8] | Disulfide cross-link planning | Focused experimental validation | Depends on model discrimination | Probabilistic model with information-theoretic planning |

The quantitative comparison reveals distinct trade-offs between computational expense and resolution. Methods employing non-uniform scaling of energy functions tackle the difficulty faced by real energy functions while overcoming limitations of simplified models [6]. The integration of 20×20 pairwise information provides more guidance than hydrophobic-polar models alone, creating a more informed energy function that helps search algorithms avoid local minima [6]. In contrast, distributed molecular dynamics approaches achieve remarkable accuracy by brute-force sampling—producing tens of thousands of trajectories representing 700 microseconds of cumulative simulation—but remain constrained to small designed proteins [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Throughput Stability Measurement Protocol

Recent advances have enabled mega-scale experimental analysis of protein folding stability, with cDNA display proteolysis emerging as a powerful method for measuring thermodynamic folding stability for up to 900,000 protein domains in a single experiment [9]. The protocol involves several critical steps:

- Library Preparation: Synthetic DNA oligonucleotide pools are created where each oligonucleotide encodes one test protein [9].

- Cell-Free Translation: The DNA library is transcribed and translated using cell-free cDNA display, resulting in proteins covalently attached to their cDNA at the C terminus [9].

- Proteolysis: Protein-cDNA complexes are incubated with different concentrations of protease (trypsin or chymotrypsin), then reactions are quenched [9].

- Pull-Down and Sequencing: Intact (protease-resistant) proteins remain attached to their C-terminal cDNA and are pulled down using an N-terminal PA tag. Relative amounts of surviving proteins are determined by deep sequencing at each protease concentration [9].

- Stability Calculation: A Bayesian model infers protease stability from sequencing counts using single turnover kinetics, ultimately determining thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) for each sequence [9].

This method achieves remarkable scale and cost-efficiency, requiring approximately one week and reagents costing about $2,000 per library (excluding DNA synthesis and sequencing costs) [9]. The accuracy has been validated against traditional purified protein experiments, with Pearson correlations above 0.75 for 1,188 variants of 10 proteins [9].

Disulfide Cross-Linking for Fold Determination

For fold determination rather than full ab initio prediction, planned disulfide cross-linking provides an experimental-computational hybrid approach [8]. The methodology involves:

- Model Generation: Obtain predicted structural models using standard fold recognition techniques [8].

- Topological Fingerprint Selection: Characterize fold-level differences between models in terms of topological contact patterns of secondary structure elements (SSEs) [8].

- SSE Pair Selection: Identify a small set of SSE pairs that differentiate the folds using an information-theoretic planning algorithm to maximize information gain while minimizing experimental complexity [8].

- Cross-Link Planning: Determine residue-level cross-links to probe selected SSE pairs, employing a minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) approach [8].

- Experimental Validation: Create dicysteine mutants and evaluate disulfide bond formation after oxidation, typically detected by altered electrophoretic mobility [8].

This approach requires only tens to around a hundred cross-links rather than testing all possible residue pairs, significantly reducing experimental complexity while maintaining high information content for model discrimination [8].

Standardized Folding Kinetics Protocol

To enable meaningful comparisons across studies, the field has established consensus experimental conditions for measuring folding kinetics [10]:

- Temperature: 25°C recommended to balance experimental practicality and backward compatibility with literature [10].

- Denaturant: Urea preferred over guanidinium salts due to fewer confounding ionic strength effects [10].

- Solvent Conditions: pH 7.0 buffers (50 mM phosphate or HEPES) with no added salt beyond that provided by the buffer [10].

- Data Reporting: Linear chevron plots should report folding and unfolding m-values (in kJ/mol/M), while nonlinear chevrons require both polynomial extrapolations and linear fits of linear regions [10].

Standardization is crucial because folding rates display strong temperature dependence (1.5%-3% per °C) and sensitivity to solvent conditions [10].

Computational Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Ab Initio Folding Optimization with Genetic Algorithm

Experimental-Computational Hybrid Fold Determination

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Experimental Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA Display System [9] | Cell-free transcription/translation | Links protein to encoding cDNA | High-throughput stability profiling |

| Proteases [9] | Trypsin and chymotrypsin | Probe folded vs. unfolded states | cDNA display proteolysis |

| Chemical Denaturants [10] | Urea (preferred) or guanidinium salts | Destabilize native state for folding studies | Kinetic chevron plots |

| Standardized Buffers [10] | 50 mM phosphate or HEPES, pH 7.0 | Maintain consistent solvent conditions | Comparative folding kinetics |

| Disulfide Cross-linking Components [8] | Cysteine substitution, oxidation conditions | Introduce structural constraints | Fold determination experiments |

| DNA Oligonucleotide Pools [9] | Synthetic libraries with variant sequences | Source of protein sequence diversity | Mega-scale stability studies |

The selection of appropriate research reagents critically influences the success and reproducibility of protein folding studies. For high-throughput stability measurements, the cDNA display system enables the crucial linkage between protein phenotype and genetic information [9]. Orthogonal proteases with different cleavage specificities (trypsin for basic residues, chymotrypsin for aromatic residues) help control for protease-specific effects and improve the reliability of inferred stabilities [9]. For kinetic studies, urea is preferred over guanidinium salts as a denaturant due to fewer confounding ionic strength effects, though guanidinium salts may be necessary for proteins that don't fully unfold in urea [10]. The emergence of robotic genetic manipulation methods enables the construction of combinatorial sets of dicysteine mutants for efficient disulfide cross-linking studies [8].

The combinatorial explosion of possible structures in protein folding presents both a fundamental challenge and an opportunity for innovative optimization approaches. Current strategies demonstrate diverse ways to navigate this vast conformational space: genetic algorithms with informed energy functions efficiently explore discrete lattices [6]; distributed computing enables unprecedented sampling of folding dynamics [7]; and hybrid experimental-computational methods leverage targeted data to guide structure determination [8]. The ongoing development of mega-scale experimental techniques [9] promises to provide the quantitative data needed to refine these approaches further.

The future of combinatorial optimization in protein folding will likely involve tighter integration between machine learning, experimental validation, and multiscale modeling. As deep learning transforms structure prediction, the incorporation of thermodynamic stability data from high-throughput experiments will be crucial for advancing beyond structural accuracy to functional understanding. The establishment of standardized experimental conditions [10] and benchmark datasets will enable more meaningful comparisons across methods and accelerate progress in confronting the combinatorial challenge of protein folding.

For decades, the thermodynamic hypothesis has served as the foundational paradigm for understanding protein folding. Introduced by Anfinsen, this principle posits that the native folded structure of a protein corresponds to the global minimum of its Gibbs free energy [11]. This elegant concept implies that a protein's amino acid sequence inherently contains all the necessary information to dictate its three-dimensional structure, as the chain spontaneously folds to reach its most thermodynamically stable state. The hypothesis drastically simplifies the theoretical modeling of folding by providing a clear destination: the unique global free energy minimum [11].

However, this classical view is increasingly challenged by the complexities of the free energy landscape and the practical demands of predicting protein structures. The original hypothesis was largely based on in vitro refolding studies of small, single-domain proteins like RNase A [11]. In the cellular environment, folding is not an isolated event but an active process often assisted by molecular machinery like chaperones, suggesting that the native state may often occupy a local, kinetically accessible minimum rather than the global minimum on a complex, rugged energy landscape [11]. This review will compare the thermodynamic hypothesis with emerging combinatorial optimization approaches that are reshaping protein folding research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear analysis of their methodologies, performance, and applicability.

Theoretical Foundations: From Thermodynamic Hypothesis to Landscape Theory

The Thermodynamic Hypothesis and its Experimental Basis

The thermodynamic hypothesis stems from Anfinsen's classic experiments demonstrating that denatured RNase A could refold spontaneously into its bioactive native conformation [11]. This led to the conclusion that the native structure is, under physiological conditions, the most stable configuration thermodynamically. The stability of this folded state is quantified by the folding free energy change (ΔG), typically a small negative value ranging from -5 to -15 kcal/mol, indicating that proteins are only marginally stable [11]. This marginal stability is crucial for protein function, as it allows for necessary flexibility and dynamics.

Experimental support for this hypothesis primarily comes from denaturation-renaturation studies using chemical denaturants like urea or guanidinium chloride, or thermal denaturation monitored by techniques such as circular dichroism (CD) or fluorescence spectroscopy [11] [10]. However, a critical examination reveals limitations in this evidence. For many proteins, complete denaturation is often assumed rather than rigorously verified with advanced structural methods. Techniques like NMR have shown that proteins considered fully denatured by conventional assays can retain significant residual native-like structure [11]. Furthermore, the available quantitative ΔG data is dominated by a small set of small, stable, single-domain proteins that may not represent the broader proteome [11].

The Free Energy Landscape Concept

The free energy landscape theory provides a more nuanced framework for understanding protein folding. This concept visualizes the folding process as a progressive navigation of a funnel-shaped landscape toward the native state [12]. The steepness and topography of this funnel determine the folding kinetics and mechanism.

Quantitative studies comparing ordered proteins with intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) reveal striking differences in their landscapes. For example, the α-helical protein HP-35 and the β-sheet WW domain exhibit steep folding funnels with slopes of approximately -50 kcal/mol, meaning the free energy decreases by about 5 kcal/mol for every 10% of native contacts formed [12]. In contrast, the intrinsically disordered protein pKID has a much shallower landscape (slope of -24 kcal/mol), explaining its disordered nature in isolation. Upon binding to its partner KIX, pKID's landscape becomes significantly steeper (slope of -54 kcal/mol), enabling folding [12].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Free Energy Landscapes

| Protein Type | Representative Example | Landscape Slope (kcal/mol) | Folding Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-helical | HP-35 | ~ -50 | Steep funnel, rapid folding |

| β-sheet | WW Domain | ~ -50 | Steep funnel, rapid folding |

| Intrinsically Disordered Protein (free) | pKID | ~ -24 | Shallow funnel, remains disordered |

| Intrinsically Disordered Protein (bound) | pKID-KIX complex | ~ -54 | Steep funnel, folds upon binding |

It is crucial to distinguish between two related but distinct free energy definitions: the free energy landscape ( f(Q) ), which represents the effective energy bias toward the native state as a function of an order parameter Q (e.g., fraction of native contacts), and the free energy profile ( F(Q) ), which includes configurational entropy and typically shows a barrier between folded and unfolded states [12]. The landscape ( f(Q) ) is globally funneled, while the profile ( F(Q) ) for a two-state folder displays the characteristic unfolded and folded minima separated by a transition state.

Visualizing the Free Energy Landscape

The following diagram illustrates the key concepts of the funneled free energy landscape for a protein, contrasting the landscapes of an ordered protein and an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP).

Combinatorial Optimization Approaches to Protein Folding

The Protein Folding Problem as Optimization

The challenge of predicting a protein's native structure from its amino acid sequence can be framed as a massive combinatorial optimization problem, where the goal is to find the conformation that minimizes an appropriate energy function. The search space is astronomically large due to the numerous degrees of freedom in a polypeptide chain, and the energy landscape is notoriously rugged with many local minima [13]. This makes finding the global minimum – presumed to be the native state – exceptionally difficult. Computational approaches to this problem can be broadly categorized into classical physics-based simulations, AI-enhanced predictive models, and novel computing paradigms.

Classical and Statistical Physics Methods

Traditional computational methods often rely on statistical physics principles to navigate the conformational space.

Molecular Dynamics (MD): MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the protein and solvent, generating a trajectory of structural changes. While providing atomic-level detail, MD is computationally extremely demanding. A landmark ~400 μs simulation of HP-35 was needed to capture its folding and unfolding dynamics [12]. Such extensive simulations remain impractical for most proteins, though distributed computing projects have generated thousands of trajectories totaling hundreds of microseconds for small designed proteins like BBA5, achieving good agreement with experimental folding times [7].

Monte Carlo Methods and Simulated Annealing: These algorithms explore the energy landscape by accepting or rejecting random conformational changes based on a probability function related to the energy change. Simulated annealing employs a gradually decreasing "temperature" parameter to reduce the probability of accepting unfavorable moves, helping the search escape local minima and converge toward the global minimum [13]. It is a versatile and widely used heuristic for protein structure prediction, especially in coarse-grained models.

Emerging Computing Paradigms

Quantum Annealing: This approach is a quantum analog of simulated annealing, designed to run on specialized quantum hardware. It utilizes quantum tunneling to potentially traverse energy barriers more efficiently than classical thermal fluctuations [13]. The protein folding problem is mapped to a finding the ground state of an Ising model or a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) problem, which is then solved by the quantum annealer. Current implementations are restricted to highly coarse-grained models (e.g., lattice proteins) due to hardware limitations. While proof-of-concept studies have shown promise, current quantum annealers are not yet capable of solving problems beyond proof-of-concept size, primarily due to challenges in embedding the problem onto the physical qubits [13].

Free-Energy Machine (FEM): A recently proposed general method, FEM is based on free-energy minimization in statistical physics, combined with automatic differentiation and gradient-based optimization from machine learning [14] [15]. It flexibly addresses various combinatorial optimization problems within a unified framework and efficiently leverages parallel computational devices like GPUs. Benchmarked on problems scaled to millions of variables, FEM has been shown to outperform state-of-the-art algorithms tailored for individual combinatorial optimization problems in both efficiency and efficacy [14]. This demonstrates the potential of combining statistical physics and machine learning for complex optimization tasks like protein folding.

Table 2: Comparison of Combinatorial Optimization Approaches for Protein Folding

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Scale/Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics | Numerical integration of physical equations of motion | All-atom or coarse-grained; up to ~milliseconds for small proteins | High physical fidelity; provides dynamical information | Extremely computationally expensive; limited by timescale |

| Simulated Annealing | Thermal Monte Carlo with decreasing temperature | Coarse-grained to all-atom | Simple, versatile; good for rugged landscapes | Can be slow; may not find global minimum in complex landscapes |

| Quantum Annealing | Quantum tunneling through energy barriers | Very coarse-grained (e.g., lattice models) | Potential for faster barrier crossing; novel hardware | Limited by current hardware (noise, qubit count); difficult embedding |

| Free-Energy Machine (FEM) | Free-energy minimization + machine learning | Can scale to millions of variables | High efficiency on GPUs; general framework across problems | New method, less proven specifically for protein folding |

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Standard Experimental Conditions for Folding Studies

To enable meaningful comparisons of folding data across different laboratories and studies, the field has moved toward standardizing experimental conditions. A consensus recommends a temperature of 25°C, a pH of 7.0, and a 50 mM buffer (e.g., phosphate or HEPES) with no added salt beyond that provided by the buffer [10]. Urea is the preferred chemical denaturant over guanidinium salts due to fewer confounding ionic strength effects. Adherence to such standards is crucial for building consistent, large-scale datasets for validating computational predictions.

Key Experimental Techniques and Data Reporting

The primary experimental data for testing the thermodynamic hypothesis and computational models come from equilibrium and kinetic folding measurements.

Equilibrium Denaturation: This method involves measuring the fraction of folded protein as a function of denaturant concentration or temperature. From these data, the free energy of folding (ΔG), the midpoint of denaturation (C~m~ or T~m~), and the cooperativity (m-value) can be extracted. The m-value reports on the change in solvent-accessible surface area upon unfolding and is a key parameter in linear extrapolation methods for determining ΔG [10].

Kinetic Folding/Unfolding: Stopped-flow and temperature-jump techniques are used to measure folding and unfolding rates across a range of denaturant concentrations. The data are typically presented as chevron plots (log(rate) vs. [denaturant]). The linear arms of these plots are extrapolated to zero denaturant to obtain the intrinsic folding (k~f~) and unfolding (k~u~) rates, from which ΔG can also be calculated (ΔG = -RT ln(k~f~/k~u~)) [10]. For phases exhibiting nonlinear chevron plots (roll-over), more complex models accounting for intermediates or transition-state movement are required, and reporting of raw kinetic data is encouraged [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Folding Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | Chemical denaturant for equilibrium and kinetic unfolding studies | Preferred over guanidinium salts for linear extrapolation; purity is critical [10] |

| Guanidinium Chloride (GdmCl) | Alternative, stronger chemical denaturant | Can be necessary for stable proteins; ionic strength effects may complicate analysis [10] |

| HEPES Buffer | pH stabilization at physiological pH (pH 7.0) | 50 mM concentration is standard; good buffering capacity without significant metal binding [10] |

| Phosphate Buffer | Alternative pH stabilization buffer | 50 mM concentration is standard; can bind some proteins, altering folding [10] |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrophotometer | Monitoring secondary structure content during folding/unfolding | Far-UV CD (190-250 nm) sensitive to α-helix and β-sheet; standard for assessing folding degree [11] [10] |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | Monitoring tertiary structure and local environment of aromatic residues | Tryptophan fluorescence is a sensitive probe for burial/exposure; often used in kinetics [11] |

| Stopped-Flow Instrument | Measuring rapid folding/unfolding kinetics (milliseconds to seconds) | Rapidly mixes protein and denaturant; essential for obtaining chevron plots [10] |

| Temperature-Jump Apparatus | Measuring very fast folding kinetics (nanoseconds to microseconds) | Uses a rapid laser-induced temperature change to initiate folding; for ultrafast folders [7] |

The following diagram outlines a typical workflow for a protein folding kinetic experiment using stopped-flow and denaturant dilution, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Performance Comparison and Discussion

Accuracy and Limitations of the Thermodynamic Hypothesis

The thermodynamic hypothesis provides a powerful conceptual framework, but its strict interpretation faces challenges. Evidence suggests that for many proteins, particularly larger multi-domain proteins or those requiring cellular factors for folding, the native state may not be the true global free energy minimum but rather a kinetically accessible local minimum [11]. Furthermore, the hypothesis is difficult to prove definitively, as experimentally measured ΔG values rely on assumptions about the completeness of unfolding and the validity of extrapolation methods [11]. The quantitative characterization of free energy landscapes shows that while the landscape is indeed funneled for ordered proteins, its precise topography varies, influencing folding mechanisms [12].

Computational Performance and Outlook

The performance of combinatorial optimization approaches varies significantly.

Classical Simulations vs. Experiments: When sufficient computational resources are applied, all-atom MD simulations can achieve remarkable agreement with experiment. For the mini-protein BBA5, thousands of simulated trajectories predicted mean folding times and equilibrium constants in excellent agreement with laser temperature-jump experiments, marking a significant milestone where computed and experimental timescales converge [7].

Emerging Paradigms vs. State-of-the-Art: While quantum annealing remains in the proof-of-concept stage for protein folding, it has demonstrated a scaling advantage over in-house simulated annealing implementations on embedded problems, hinting at its potential future utility [13]. In broader combinatorial optimization, the Free-Energy Machine (FEM) has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance, outperforming specialized algorithms on problems scaled to millions of variables [14]. Its application to protein folding, while not yet fully explored, represents a highly promising direction given its general framework and efficiency on parallel hardware.

The field is increasingly recognizing that a full understanding of protein folding requires moving beyond the in vitro thermodynamic view to an in vivo perspective where folding is a non-equilibrium, active, energy-dependent process often occurring during translation and assisted by chaperones [11]. Future computational models that can incorporate these cellular factors and leverage the power of advanced optimization algorithms like FEM, potentially integrated with AI-based structure prediction tools, will provide a more complete and physiologically relevant understanding of protein folding.

Determining the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence represents one of the most significant challenges in computational biology and bioinformatics. The widening gap between the number of known protein sequences and experimentally determined structures has intensified the need for reliable computational prediction methods. As of 2008, only about 1% of sequences in the UniProtKB database corresponded to structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), leaving a gap of approximately five million sequences without structural information [16]. This structural deficit has driven the development of three principal computational approaches: ab initio, de novo, and comparative modeling (also known as homology modeling). These methods differ fundamentally in their underlying principles, computational requirements, and applicability ranges, yet all aim to address the same critical problem: how to accurately translate one-dimensional sequence information into three-dimensional structural models that researchers can use to understand biological function and guide therapeutic development.

The protein structure prediction problem is computationally vast because the number of possible conformations available to a polypeptide chain is astronomically large. If each of the 100 amino acid residues in a small polypeptide could adopt just 10 different conformations, the chain could theoretically sample 10^100 different conformations. If one conformation was tested every 10^-13 second, it would take approximately 10^77 years to sample all possibilities [16]. Yet, proteins in biological systems fold reliably on timescales ranging from microseconds to minutes, indicating that the folding process is not random but follows specific structural principles that computational methods attempt to capture. The existence of these guiding principles makes computational structure prediction feasible, though still enormously challenging.

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

Comparative Modeling (Homology Modeling)

Comparative modeling operates on the well-established principle that protein structure is more evolutionarily conserved than amino acid sequence. When two proteins share sufficient sequence similarity, they likely share the same overall three-dimensional fold, even if their sequences have diverged significantly over evolutionary time [17]. This approach uses experimentally determined structures of related proteins (templates) to build models for target sequences with unknown structures. The core assumption is that if the target and template are evolutionarily related, the target's structure can be approximated by the template's structure, with modifications to account for sequence differences.

The effectiveness of comparative modeling depends critically on the degree of sequence identity between the target and available templates. The relationship between sequence identity and expected model accuracy falls into distinct zones. Above 40% sequence identity, models are typically reliable at both the backbone and side-chain levels. Between 20% and 35% sequence identity lies the "twilight zone," where alignment errors become more frequent and models require careful validation. Below 20% sequence identity is the "midnight zone," where detecting homology becomes challenging and fold recognition methods may be necessary [17]. Despite these challenges, comparative modeling can sometimes detect structural similarities even when sequence similarity is negligible, thanks to the limited number of protein folds in nature—estimated to be only around 2000 distinct types [18].

Ab Initio and De Novo Protein Structure Prediction

The terms "ab initio" and "de novo" are often used interchangeably in protein structure prediction literature to describe methods that predict protein structure from physical principles rather than by relying on explicit structural templates [16] [18]. These methods attempt to simulate the protein folding process using fundamental physics and chemistry principles, typically by searching the conformational space for structures that minimize an energy function derived from molecular mechanics.

Ab initio methods specifically emphasize their basis in first principles ("from the beginning") without incorporating knowledge from known protein structures beyond fundamental physical parameters. These methods use force fields that describe atomic interactions, hydrogen bonding, solvation effects, and other physicochemical properties to guide the folding simulation. The all-atom discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) approach exemplifies this category, employing an all-atom protein model with a transferable force field featuring packing, solvation, and environment-dependent hydrogen bond interactions [19].

De novo methods, a term first coined by William DeGrado, similarly build three-dimensional protein models "from scratch" but may incorporate statistical information from known structures in their energy functions or fragment assembly procedures [16]. For example, the QUARK algorithm constructs protein structures by assembling continuously sized fragments (1-20 residues) excised from unrelated protein structures through replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulations [20]. While these fragments come from the PDB, the assembly process does not use global template structures, maintaining the "from scratch" nature of the prediction.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Structure Prediction Approaches

| Feature | Comparative Modeling | Ab Initio/De Novo |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Evolutionary conservation & template structures | Physical principles & statistical preferences |

| Template Requirement | Requires identified homologous template | No homologous template required |

| Computational Demand | Moderate | Very high |

| Typical Application Range | Sequences with detectable homologs in PDB | Proteins without homologous templates |

| Accuracy | High when sequence identity >30% | Variable; typically lower than comparative modeling |

| Key Limitation | Template availability & alignment accuracy | Computational complexity & energy function accuracy |

Methodological Frameworks and Workflows

Comparative Modeling Pipeline

The comparative modeling process follows a well-defined, sequential workflow consisting of four key steps that are often iterated until a satisfactory model is obtained [17]. First, template selection involves identifying protein structures in the PDB that are likely to share the same fold as the target sequence. This step typically employs sequence comparison methods like PSI-BLAST or more sensitive profile-based methods like HMMER for detecting distant homologs. For particularly challenging cases with very low sequence similarity, threading methods such as FUGUE, Threader, or 3D-PSSM may be used to identify potential templates by assessing sequence-structure compatibility [17].

The second step involves creating a target-template alignment to map the target sequence onto the three-dimensional coordinates of the template structure. Programs like CLUSTALW, STAMP, or CE are commonly used for this purpose, with the alignment accuracy being perhaps the most critical factor determining the final model quality. Even with perfect template selection, errors in this alignment step will propagate through to the final model, particularly in the "twilight zone" of sequence identity where alignment becomes non-trivial [17].

The third step, model building, generates the actual three-dimensional coordinates for the target protein. Several approaches exist for this step, including rigid-body assembly of conserved core regions, segment matching, and satisfaction of spatial restraints. Software tools like MODELLER, COMPOSER, and SwissModel implement these approaches, with MODELLER being particularly popular for its use of spatial restraints derived from the template structure [17] [18].

The final step of model evaluation assesses the quality of the generated model using various geometric and statistical measures. Tools like PROCHECK analyze stereochemical quality, while statistical potentials such as those implemented in PROSA II assess the overall fold reliability [17] [21]. This evaluation step often triggers iterations through the previous steps if the model quality is deemed insufficient.

Figure 1: Comparative Modeling Workflow. The process begins with template selection and proceeds through alignment, model building, and evaluation, with iterative refinement until model quality is acceptable.

Ab Initio/De Novo Methodologies

Ab initio and de novo methods employ fundamentally different strategies from comparative modeling, focusing on conformational sampling and energy minimization without relying on explicit structural templates. These methods generally follow a paradigm involving extensive sampling of conformation space guided by scoring functions, followed by selection of native-like conformations from the generated decoys [16].

The TerItFix framework exemplifies a modern de novo approach that implements sequential stabilization as a search strategy. This method begins with approximately 500 individual Monte Carlo Simulated Annealing (MCSA) folding simulations using specialized backbone moves and energy functions for a reduced chain representation (backbone plus Cβ atoms). The best structures from these simulations are analyzed for recurring secondary structures and tertiary contacts, which then inform modified move sets and energy functions for subsequent rounds of simulation [22]. This iterative process progressively learns and stabilizes structural motifs through constraints derived from prior rounds, effectively mimicking the authentic folding process where early formed structure templates guide subsequent folding events.

Another prominent approach is implemented in the QUARK algorithm, which employs a fragment-assembly methodology. Unlike template-based methods that use large, global templates, QUARK assembles structures from continuously sized fragments (1-20 residues) excised from unrelated protein structures. These fragments provide local structural preferences without biasing the global fold. The algorithm uses a replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulation to assemble these fragments into complete structures, guided by a knowledge-based force field that includes terms for hydrogen bonding, solvation, and backbone and side-chain interactions [20].

Discrete Molecular Dynamics (DMD) with all-atom representation represents a more physically realistic ab initio approach. This method uses a simplified molecular dynamics engine that employs discontinuous potentials to enable larger time steps and more efficient conformational sampling. The force field includes terms for packing, solvation, and environment-dependent hydrogen bond interactions, making it transferable across different proteins without requiring known structural templates [19].

Figure 2: Ab Initio/De Novo Folding Workflow. The process involves initial conformational sampling, identification of recurring structural motifs, and iterative refinement through biased sampling until convergence.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Accuracy Metrics and Assessment Methods

Evaluating the performance of protein structure prediction methods requires standardized metrics that quantify the similarity between predicted and experimentally determined structures. The most common metrics include Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which measures the average distance between equivalent atoms after optimal superposition; Template Modeling Score (TM-score), which provides a more global measure of structural similarity that is less sensitive to local errors; and Global Distance Test (GDT), which calculates the percentage of residues that can be superimposed under a given distance cutoff [20].

For comparative models, assessment often includes additional measures of stereochemical quality such as Ramachandran plot statistics, rotamer preferences, and bond length/angle deviations. Composite scores that combine multiple assessment criteria have been developed to provide more reliable fold assessment. These include methods that use genetic algorithms to find optimal combinations of statistical potential scores, stereochemistry quality descriptors, sequence alignment scores, and protein packing measures [21].

Quantitative Performance Data

Direct performance comparisons between comparative modeling and ab initio/de novo approaches demonstrate the complementary strengths of these methods. In benchmark tests on known E. coli protein structures where homologous templates with >30% sequence identity were excluded, QUARK-based ab initio folding generated models with TM-scores 17% higher than those produced by traditional comparative modeling methods like MODELLER [20]. This performance advantage for hard targets without close homologs highlights the potential of modern ab initio methods to address the most challenging prediction cases.

In large-scale assessments like the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, ab initio methods have demonstrated steadily improving performance. For example, in CASP9, QUARK successfully predicted correct folds (TM-score > 0.5) for 8 out of 18 Free Modeling (FM) target proteins with lengths below 150 residues that had no analogous templates in the PDB. In CASP10, the same method produced models with TM-score > 0.5 for two FM targets with lengths > 150 residues, representing some of the largest successful free modeling achievements in CASP history [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Prediction Methods on E. coli Proteome

| Method Category | Target Type | Success Rate (TM-score > 0.5) | Typical RMSD (Å) | Applicable Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Modeling | Easy/Medium targets (64.6% of proteome) | High (>70%) | 1-5 | Sequences with detectable templates |

| Ab Initio (QUARK) | Hard targets (<30% identity) | ~16% (72/495 proteins) | 3-10 | Proteins without close templates |

| All-Atom DMD | Small proteins (20-60 residues) | Native/near-native in all cases tested | N/R | Small single-domain proteins |

For smaller proteins (20-60 residues), all-atom discrete molecular dynamics with replica exchange sampling has demonstrated remarkable success, reaching native or near-native states in folding simulations of six small proteins with distinct native structures [19]. In these cases, multiple folding transitions were observed, with computationally characterized thermodynamics in qualitative agreement with experimental data, suggesting that the physical principles governing folding are being adequately captured by the method.

Research Applications and Practical Implementation

Genome-Wide Structure Prediction

The integration of multiple structure prediction approaches enables comprehensive genome-wide structure modeling efforts. A hybrid pipeline combining ab initio folding and template-based modeling applied to the Escherichia coli genome demonstrated the complementary value of both approaches. For the 64.6% of E. coli proteins categorized as Easy/Medium targets (with strong homologous templates), comparative modeling methods like I-TASSER could generate reliable models. For the remaining 495 Hard targets (no detectable templates), QUARK-based ab initio folding produced models with correct folds (TM-score > 0.5) for 72 proteins and substantially correct portions (TM-score > 0.35) for 321 proteins [20]. This integrated approach allowed structural fold assignment to SCOP fold families for 317 sequences based on structural analogy to existing proteins in PDB, demonstrating progress toward comprehensive genome-wide structure modeling.

Practical Considerations and Resource Requirements

The computational demands of different prediction methods vary dramatically and represent a critical practical consideration for researchers. Comparative modeling methods are relatively efficient, with model generation typically requiring minutes to hours on standard computing hardware for single proteins. In contrast, ab initio and de novo methods demand substantially greater computational resources. For example, predicting the tertiary structure of protein T0283 using Rosetta@home required almost two years and approximately 70,000 home computers participating in a distributed computing project [16].

To make ab initio methods more practical, reduced representations that simplify the atomic detail of proteins are often employed. The TerItFix method uses a chain representation lacking explicit side chains, rendering the simulations many orders of magnitude faster than all-atom molecular dynamics simulations while still capturing essential folding physics [22]. Similarly, discrete molecular dynamics employs simplified potentials to accelerate sampling while maintaining an all-atom representation [19].

Table 3: Computational Requirements of Different Prediction Approaches

| Method | Computational Demand | Sampling Strategy | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Modeling (MODELLER) | Low to Moderate | Satisfaction of spatial restraints | Standard workstation |

| Ab Initio (QUARK) | High | Fragment assembly with Monte Carlo | High-performance computing cluster |

| All-Atom DMD | Very High | Replica exchange molecular dynamics | Specialized supercomputing resources |

| TerItFix | Moderate | Monte Carlo with iterative biasing | Medium-sized computing cluster |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of protein structure prediction requires access to specialized software tools and databases. Key resources include:

- MODELER: A popular software tool for homology modeling that uses methodology derived from NMR spectroscopy data processing to satisfy spatial restraints [18].

- SwissModel: An automated web server for basic homology modeling that provides a user-friendly interface for comparative model building [17].

- QUARK: A de novo structure prediction algorithm that assembles structures from continuously sized fragments through replica-exchange Monte Carlo simulations [20].

- Discrete Molecular Dynamics (DMD): A rapid sampling engine used in protein folding studies with all-atom representation and specialized force fields [19].

- 3D-PSSM: A protein threading tool that combines sequence profiles with secondary structure and solvation potential information for fold recognition [17].

- PROCHECK: A structure validation tool that assesses stereochemical quality of protein models using Ramachandran plots and other geometric checks [17].

- Protein Data Bank (PDB): The central repository for experimentally determined protein structures that serves as the primary source of templates for comparative modeling and fragments for de novo methods [20].

- SCOP Database: A manual classification of protein structural domains that enables fold assignment and functional annotation of predicted models [20].

The three major approaches to protein structure prediction—comparative modeling, ab initio, and de novo methods—offer complementary strengths for addressing the sequence-structure gap in molecular biology. Comparative modeling provides accurate, high-resolution models when homologous templates are available, covering a significant portion of most proteomes. Ab initio and de novo methods address the challenging frontier of proteins without clear homologs, using physical principles and sophisticated sampling algorithms to predict novel folds. The continuing development of hybrid approaches that combine elements from both paradigms represents the most promising direction for comprehensive genome-wide structure modeling. As computational power increases and algorithms refine, the integration of these approaches will increasingly enable researchers to obtain structural insights for any protein of interest, accelerating drug discovery and fundamental biological understanding.

Combinatorial optimization serves as the computational backbone of modern protein folding research, tackling some of the most challenging problems in structural bioinformatics. The field grapples with enormous search spaces where the number of possible protein configurations grows exponentially with sequence length, creating computationally intractable (NP-hard) problems even for classical supercomputers. Energy functions—whether derived from physical force fields or learned from data—must accurately discriminate between correct and incorrect folds while remaining computationally feasible to evaluate. Computational tractability remains the final gatekeeper, determining which optimization approaches can transition from theoretical frameworks to practical tools for researchers. This guide systematically compares the current landscape of combinatorial optimization methodologies, evaluating their performance across these three core challenges to inform selection decisions for specific research scenarios.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Approaches

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and trade-offs of prominent optimization approaches used in protein folding research.

Table 1: Comparison of Combinatorial Optimization Approaches for Protein Folding

| Optimization Approach | Typical Applications in Protein Research | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Representative Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning-based Folding | Tertiary structure prediction from sequence | High accuracy, rapid inference on known fold types | Limited novel fold prediction, high computational resources for training | AlphaFold, ESMFold, OmegaFold [23] |

| Classical Heuristics & Metaheuristics | Network analysis of PPI, side-chain positioning | Theoretical guarantees, interpretability, handles constraints | Exponential time complexity for exact methods, often requires approximations | Maximum clique/independent set algorithms [24], Simulated Annealing [25] |

| Quantum-Inspired Optimization | Side-chain packing, rotamer selection | Potential quantum advantage for specific problem classes, novel exploration of energy landscape | Hardware limitations, mapping overhead, currently proof-of-concept scale | QAOA, Quantum Annealing for QUBO [25] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Inverse protein folding, sequence design | Sample efficiency, handles black-box functions, integrates constraints | Limited to moderate parameter dimensions, sequential evaluation | Deep Bayesian Optimization [3] |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Predictive Accuracy and Computational Efficiency

The performance of deep learning-based protein folding tools varies significantly across different sequence lengths and computational constraints. The following table synthesizes experimental benchmarking data from comparative studies.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of ML Protein Folding Tools on Standard Hardware (A10 GPU) [23]

| Model | Sequence Length | Running Time (s) | PLDDT Score | CPU Memory (GB) | GPU Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESMFold | 50 | 1 | 0.84 | 13 | 16 |

| 400 | 20 | 0.93 | 13 | 18 | |

| 800 | 125 | 0.66 | 13 | 20 | |

| OmegaFold | 50 | 3.66 | 0.86 | 10 | 6 |

| 400 | 110 | 0.76 | 10 | 10 | |

| 800 | 1425 | 0.53 | 10 | 11 | |

| AlphaFold (ColabFold) | 50 | 45 | 0.89 | 10 | 10 |

| 400 | 210 | 0.82 | 10 | 10 | |

| 800 | 810 | 0.54 | 10 | 10 |

Algorithmic Performance Across Problem Types

Classical randomized optimization algorithms demonstrate distinct performance characteristics across different problem landscapes relevant to protein research.

Table 3: Performance of Randomized Algorithms on Combinatorial Problem Types [26]

| Algorithm | Binary Problems | Permutation Problems | General Combinatorial Problems | Computational Efficiency | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHC | Limited performance due to local optima | Poor performance on complex constraints | Moderate for simple landscapes | High | Low |

| SA | Good with careful annealing schedule | Moderate, depends on neighborhood structure | Good for various problem types | Medium | Medium |

| GA | Excellent with appropriate representation | Good with specialized operators | Excellent, balanced performance | Medium to Low | Medium |

| MIMIC | Superior on correlated landscapes | Limited exploration capability | Excellent solution quality | Low (high memory) | High |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Protocol for Protein Folding Tools

Experimental evaluations of protein folding tools follow standardized protocols to ensure fair comparison. The benchmarking methodology for data presented in Table 2 involved:

Hardware Configuration: All models were executed on identical infrastructure featuring an A10 GPU with standardized driver versions and containerization to ensure consistent performance measurement [23].

Sequence Selection: Standardized sequences of varying lengths (50-1600 amino acids) were selected from diverse protein families to represent typical use cases while avoiding unusual structural complexities that might skew results [23].

Evaluation Metrics:

- Running Time: Measured from initialization to complete structure output, excluding model loading time.

- PLDDT Score: Standard confidence metric ranging from 0-1, with higher values indicating greater reliability.

- Memory Usage: Peak memory consumption during inference on both CPU and GPU [23].

Validation Procedure: Results were validated against known structures where available, with multiple runs to account for stochastic variations in performance [23].

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Workflow for Side-Chain Optimization

The quantum-classical methodology for protein side-chain optimization follows a structured pipeline [25]:

Problem Formulation: The side-chain conformation problem is mapped to a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) model where each binary variable represents a specific rotamer choice for each amino acid side-chain.

Energy Calculation: Classical computation of pairwise interaction energies between rotamers using molecular mechanics force fields, creating an energy matrix for the optimization problem.

Quantum Encoding: Transformation of the QUBO problem into an Ising Hamiltonian compatible with quantum processing units using parity encoding techniques.

Hybrid Execution: Implementation of the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) with parameterized quantum circuits, where classical optimizers tune quantum parameters to minimize the energy function.

Solution Extraction: Measurement of the quantum state to obtain candidate solutions, followed by classical post-processing to validate structural constraints and refine solutions.

Inverse Folding via Bayesian Optimization

The inverse protein folding workflow using Bayesian optimization employs this multi-stage methodology [3]:

Objective Specification: Define the target protein structure and similarity metrics (e.g., RMSD, TM-score) to quantify how closely designed sequences match the desired fold.

Surrogate Modeling: Construct a probabilistic model (typically Gaussian process regression) that approximates the relationship between sequence features and structural outcomes based on initial sampling.

Acquisition Function Optimization: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound) to balance exploration of novel sequences with exploitation of promising regions.

Iterative Refinement: Sequentially evaluate candidate sequences, update the surrogate model, and refine the search direction until convergence criteria are met.

Constraint Integration: Incorporate biological constraints (e.g., stability requirements, functional site preservation) directly into the acquisition function or through filtering mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Libraries for Optimization in Protein Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold/ColabFold | Deep Learning Model | Protein structure prediction from sequence | Rapid tertiary structure prediction with high accuracy [23] |

| ESMFold | Deep Learning Model | Protein structure prediction leveraging language models | Fast inference for high-throughput applications [23] |

| OmegaFold | Deep Learning Model | Structure prediction without multiple sequence alignment | Handling proteins with limited homology data [23] |

| Qiskit | Quantum Computing Framework | Quantum algorithm development and simulation | Implementing QAOA for side-chain optimization [25] |

| D-Wave Ocean | Quantum Annealing SDK | QUBO formulation and quantum annealing execution | Solving combinatorial optimization problems [25] |

| Rosetta | Molecular Modeling Suite | Protein structure prediction and design | Classical benchmark for quantum and ML methods [25] |

| Gurobi | Mathematical Optimizer | Solving LP, QP, and MIP problems | Energy minimization in classical approaches [27] |

| PyTorch/TensorFlow | ML Framework | Developing and training custom deep learning models | Implementing novel protein folding architectures |

The landscape of combinatorial optimization for protein folding reveals a diverse ecosystem where different approaches excel under specific constraints. Deep learning methods currently dominate tertiary structure prediction, offering remarkable speed-accuracy tradeoffs but requiring substantial computational resources for training. Classical optimization approaches maintain relevance for well-constrained subproblems like side-chain positioning and network analysis, particularly when interpretability and constraint handling are prioritized. Emerging quantum and Bayesian methods show promise for specific problem classes like inverse folding and rotamer selection but remain in developmental stages for widespread practical application.

Selection of an appropriate optimization strategy must consider multiple dimensions: sequence characteristics, available computational budget, accuracy requirements, and interpretability needs. For rapid structure prediction of typical proteins, ESMFold provides the best balance of speed and accuracy, while AlphaFold remains the gold standard for accuracy when resources permit. For novel protein design and inverse folding problems, Bayesian optimization approaches offer sample-efficient exploration of sequence space. As quantum hardware matures, hybrid quantum-classical approaches may become increasingly viable for specific combinatorial subproblems like side-chain packing. The optimal approach frequently involves combining multiple methodologies, leveraging their complementary strengths to address the multifaceted challenges of protein folding research.

Algorithmic Arsenal: Key Combinatorial and AI-Driven Methods

Protein structure prediction is a fundamental challenge in molecular biology, driven by the thermodynamic hypothesis that a protein's native, functional state resides at its global free energy minimum [28]. The immense conformational space, combined with a rugged energy landscape riddled with local minima, makes this problem NP-hard [29]. Among the various computational strategies employed, Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) and Genetic Algorithms (GAs) represent a class of robust, physics-inspired heuristics that mimic natural selection to navigate this complex landscape efficiently. These algorithms maintain a population of candidate protein conformations, which are gradually improved through iterative processes of selection, mutation, and crossover [30]. Unlike some domain-specific methods, EAs are highly flexible and can be adapted to various energy functions and coarse-grained models, making them a versatile tool in the computational biologist's toolkit [29]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of EA-based approaches against other combinatorial optimization methods, outlining their principles, workflows, and performance in the context of modern protein folding research.

Foundational Principles and Algorithmic Workflow

The core premise of evolutionary algorithms is to treat protein structure prediction as an optimization problem, where the goal is to find the conformation that minimizes a scoring or energy function.

Core Components of a Genetic Algorithm for Protein Folding

- Population: A set of multiple candidate protein conformations (chromosomes) is maintained simultaneously, which helps explore different regions of the conformational space.

- Fitness Function: This function, typically a physics-based or knowledge-based energy function, evaluates the quality of each conformation. In the Hydrophobic-Polar (HP) model, the fitness is often the number of hydrophobic (H-H) contacts, as these represent favorable interactions that drive folding [29].

- Selection: Individuals from the population are selected for "breeding" based on their fitness, ensuring that better conformations have a higher chance of passing on their traits.

- Genetic Operators: These operators create new candidate solutions:

- Crossover: Combines structural fragments from two parent conformations to generate offspring. Advanced techniques may use lattice rotation to increase the success rate of this operation [29].

- Mutation: Introduces random changes to an individual's conformation to maintain diversity. This is often implemented via move sets like pull-move, k-site move, or end-move [29].

- Local Search: Many modern EA implementations hybridize the global search of the GA with local search heuristics like Generalized Pull Move or K-site Move to refine conformations and accelerate convergence [29].

The HP Lattice Model

A critical simplification used in many EA studies is the HP Lattice Model. This model classifies each amino acid in a sequence as either Hydrophobic (H) or Polar (P). The protein chain is then folded onto a discrete lattice (e.g., 2D square, 3D cubic, or 3D Face-Centered Cubic (FCC)), and the objective is to find a self-avoiding walk that maximizes the number of topological H-H contacts, which are non-sequential neighbors on the lattice [29]. The 3D FCC lattice, with its high packing density and 12 neighboring points per node, is often preferred as it produces conformations closer to real proteins and avoids parity problems found in simpler cubic lattices [29].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow of an evolutionary algorithm applied to protein folding.

Performance Comparison with Other Combinatorial Optimization Methods

Evolutionary Algorithms are one of several combinatorial optimization strategies for tackling the protein folding problem. The table below summarizes how they compare to other prominent approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Combinatorial Optimization Approaches for Protein Folding

| Method | Key Principle | Representative Algorithms/Tools | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary/Genetic Algorithms | Population-based global search inspired by natural selection [30]. | EA with Lattice Rotation & Move Sets [29], Multi-Objective GA (MOGA) [31]. | Robust and flexible with arbitrary energy functions [29]; Hybridization potential with local search; Capable of discovering novel folds without templates. | Performance can degrade with increasing problem size [32]; Heuristic nature means no guarantee of global optimum. |

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Formulates problem as a linear program with integer variables to find proven global minimum [32]. | Standard MILP Solvers [32]. | Exact method providing mathematical guarantee of optimality for the discrete model. | Becomes computationally intractable for large sequences due to NP-hardness [32]. |

| Dead-End Elimination (DEE) / A* | Prunes conformation space by eliminating rotamers that cannot be part of the global minimum [33]. | DEE/A* [33], integrated in toulbar2 (CFN solver) [33]. | An exact method that can be highly efficient for specific problems, especially in protein design [33]. | Efficiency deteriorates with more complex energy interactions [32]. |

| Constraint Programming (CP) | Models the problem as a set of constraints (e.g., self-avoidance) that must be satisfied [29]. | HPstruct [29]. | State-of-the-art performance on HP lattice models; can ensure global optimum [29]. | Does not always converge; difficult to adapt for complex, non-lattice energy functions [29]. |

| Quantum Annealing (QA) | Uses quantum fluctuations to tunnel through energy barriers and find low-energy states [34]. | QA for coarse-grained lattice models [34]. | Potential scaling advantage for rugged energy landscapes via quantum tunneling [34]. | Currently at proof-of-concept stage; limited to very short sequences on current hardware [34]. |

Analysis of Comparative Performance Data

The theoretical comparison is further illuminated by specific experimental performance data, particularly on standardized HP lattice models.

Table 2: Experimental Performance on 3D FCC HP Model

| Sequence / Protein | Algorithm | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark sequences (e.g., 1CNL) | Improved EA [29] | Lattice rotation, K-site mutation, generalized Pull Move. | Found optimal conformations previously not found by earlier EA-based approaches. |

| Various HP sequences | Constraint Programming (HPstruct) [29] | Exact method for constraint satisfaction on a lattice. | Best observed performance when it converges [29]. |

| Short peptide sequences (≤18 residues) | Quantum Annealing [34] | Novel tetrahedral lattice encoding on quantum hardware. | Able to find ground states for very short sequences; scaling advantage observed only on embedded problems [34]. |