Comparative Analysis of Preprocessing Methods for Molecular Descriptors: Enhancing QSAR Modeling and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of preprocessing techniques for molecular descriptors, a critical step in building robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models.

Comparative Analysis of Preprocessing Methods for Molecular Descriptors: Enhancing QSAR Modeling and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of preprocessing techniques for molecular descriptors, a critical step in building robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational role of descriptors in chemoinformatics, evaluates a wide array of feature selection and data normalization methodologies, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance. Through a validation-focused lens, it benchmarks the effectiveness of various preprocessing techniques, including Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Forward/Backward Selection, in improving predictive accuracy for tasks like anti-cathepsin activity prediction. The synthesis of these insights provides a actionable framework for selecting and applying preprocessing methods to enhance the efficiency and success of computational drug discovery pipelines.

Molecular Descriptors and Preprocessing: The Bedrock of Modern Cheminformatics

Molecular descriptors are the final result of a logical and mathematical procedure, which transforms chemical information encoded within a symbolic representation of a molecule into a useful number or the result of some standardized experiment [1]. They serve as the foundational bridge between the physical world of chemistry and the computational world of machine learning, enabling the prediction of molecular properties, activities, and behaviors [2]. The evolution of these descriptors mirrors the advancement of computational chemistry itself, moving from simple, human-engineered fingerprints to complex, data-driven representations learned by deep neural networks. This progression is critical for modern drug discovery, where the accurate and efficient representation of molecules directly impacts the success of virtual screening, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, and de novo molecular design [3] [4]. The choice of representation is not merely a technical preliminary but a decisive factor that influences the performance of downstream predictive tasks, making a comparative analysis of preprocessing methods essential for researchers in the field.

A Comparative Taxonomy of Molecular Representations

Molecular representations can be broadly classified into several categories based on their underlying principles and the nature of the information they encode. The following table summarizes the key types, their characteristics, and primary applications.

Table 1: Taxonomy of Major Molecular Descriptor Types

| Descriptor Category | Core Principle | Representation Format | Key Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints [5] [4] | Encodes presence/absence of specific substructures | Binary or count-based vectors | Computational efficiency, interpretability, proven performance in similarity search | Virtual screening, QSAR, clustering |

| Property-Based Descriptors [1] [4] | Calculates theoretical physicochemical properties | Numerical vectors of continuous/categorical values | Direct encoding of chemically meaningful properties | QSAR, exploratory data analysis |

| Graph-Based Representations [5] [2] | Models molecules as graphs (atoms=nodes, bonds=edges) | Adjacency, node feature, and edge feature matrices | Naturally captures molecular topology and connectivity | Molecular property prediction, AI-driven drug discovery |

| String-Based Representations [2] [4] | Uses character strings to denote structure (e.g., SMILES, InChI) | Text strings (e.g., SMILES, InChI) | Compact, human-readable, easy to store and process | Data storage, de novo molecular design |

| Language Model-Based Representations [3] [4] | Applies NLP models to treat molecules as a "chemical language" | Continuous vectors (embeddings) | Data-driven feature learning, captures complex structural patterns | Property prediction, scaffold hopping |

| Data-Driven Continuous Descriptors [6] | Employs NMT or autoencoders to learn from molecular structures | Low-dimensional continuous vectors | Captures semantic meaning, enables molecular optimization and exploration | QSAR, virtual screening, compound optimization |

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data and Protocols

Taste Prediction: GNNs and Consensus Models vs. Traditional Fingerprints

A comprehensive comparative analysis on a dataset of 2601 molecules from ChemTastesDB evaluated the performance of various molecular representations for predicting taste modalities like sweetness, bitterness, and umami [5]. The study employed a standardized data preparation protocol, splitting the dataset into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:1:2 ratio while ensuring the distribution of taste categories was representative in each subset [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Models on Taste Prediction Tasks [5]

| Molecular Representation | Model Architecture | Sweet Prediction (Accuracy) | Bitter Prediction (Accuracy) | Umami Prediction (Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | Not Specified | Competitive baseline | Competitive baseline | Competitive baseline |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | DeepPurpose Toolkit | High performance | High performance | High performance |

| Fingerprints + GNN (Consensus) | DeepPurpose Toolkit | Top performance | Top performance | Top performance |

The results revealed that Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) outperformed other approaches in taste prediction [5]. Furthermore, the study found that consensus models, which combine diverse molecular representations, demonstrated improved performance. Specifically, the hybrid molecular fingerprints + GNN consensus model emerged as the top performer, highlighting the complementary strengths of GNNs, which can learn complex structure-property relationships, and molecular fingerprints, which provide a robust, predefined feature set [5].

Peptide Function Prediction: The Surprising Efficacy of Fingerprints

In a large-scale benchmark study encompassing 132 peptide datasets, simple molecular fingerprints combined with a LightGBM classifier were tested against more complex graph neural networks and transformer-based models [7]. The experimental protocol involved representing peptides as atom-level graphs, which were then vectorized using count-based molecular fingerprints [7].

Table 3: Molecular Fingerprints for Peptide Function Prediction [7]

| Molecular Fingerprint Type | Subgraph Structure | Key Characteristics | Performance vs. GNNs/Transformers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) | Circular atom neighborhoods | Analogous to shallow GNNs; domain-specific, deterministic | State-of-the-art accuracy |

| Topological Torsion (TT) | Linear paths of 4 atoms | Designed for short-range molecular interactions | Competitive or superior performance |

| RDKit Fingerprint | All subgraphs up to 7 bonds | Includes small cyclic structures; non-linear paths | State-of-the-art accuracy |

Despite being inherently local and lacking the ability to model long-range dependencies, these fingerprint-based models achieved state-of-the-art accuracy, outperforming complex deep learning models like GNNs and graph transformers [7]. This challenges the assumed necessity of explicitly modeling long-range interactions for peptide property prediction and highlights molecular fingerprints as efficient, interpretable, and computationally lightweight alternatives.

Essential Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Comparative QSAR Modeling

The general procedure for constructing a QSAR or QSPR model using molecular descriptors follows a systematic workflow, as outlined in studies involving software like Mordred [1].

Diagram 1: QSAR Model Construction Workflow

1. Dataset Preparation: The first step involves sourcing and curating a dataset of molecules with associated target properties or activities. For example, the taste prediction study used 2601 molecules from ChemTastesDB, removing duplicates and multi-taste molecules to ensure data quality [5]. The dataset is then split into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 7:1:2 ratio) to allow for model training and unbiased evaluation [5] [1].

2. Descriptor Calculation: Molecular descriptors are computed for every compound in the dataset. This can be performed using software like Mordred, which calculates over 1800 2D and 3D descriptors [1]. Preprocessing steps, such as adding or removing hydrogen atoms and Kekulization, are often handled automatically by the software to ensure correctness.

3. Model Construction and Training: A machine learning model is trained on the calculated descriptors of the training set to predict the target property. Algorithms range from classical methods like Random Forest and SVM to more advanced deep learning architectures like GNNs [5] [7].

4. Model Evaluation: The final step is to evaluate the predictive performance and potential generalization of the constructed model by predicting the target activities of the compounds in the held-out test dataset [1].

Protocol for Neural Machine Translation of Molecular Representations

A modern, data-driven approach to generating molecular descriptors involves using a neural machine translation (NMT) model, which learns to translate between different molecular representations [6].

Diagram 2: Neural Machine Translation for Descriptors

1. Data Preparation and Tokenization: A large corpus of chemical structures is gathered, and each molecule is represented in two semantically equivalent but syntactically different formats, such as InChI and SMILES [6]. These sequence-based representations are tokenized on a character level (e.g., treating "Cl" and "Br" as single tokens) and converted into one-hot vector representations.

2. Model Architecture and Training: The model comprises an encoder and a decoder network. The encoder (e.g., a CNN or RNN) processes the input sequence (e.g., an InChI) and compresses it into a fixed-size continuous "latent representation" vector. The decoder (an RNN) then uses this vector to generate the output sequence (e.g., a SMILES string). The entire model is trained to minimize the translation error between the predicted and actual output sequences [6].

3. Descriptor Extraction: Once the model is trained, the encoder can be used independently. Feeding any new molecule's input representation (e.g., InChI) into the encoder yields its corresponding low-dimensional, continuous descriptor, which can then be used for downstream QSAR or virtual screening tasks [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Software

The implementation of the experimental protocols described above relies on a suite of software libraries and computational tools. The following table details key resources for calculating and utilizing molecular descriptors.

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Research

| Tool Name | Type/Brief Description | Key Function | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mordred [1] | Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Calculates >1800 2D and 3D molecular descriptors. Can be used via CLI, web app, or Python API. | BSD (Open Source) |

| RDKit [4] | Cheminformatics Software | A foundational toolkit that supports various representations (SMILES, fingerprints) and cheminformatics operations. | Open Source |

| DeepPurpose [5] | Deep Learning Toolkit | A molecular modeling toolkit that integrates various molecular representation methods (CNNs, RNNs, GNNs) for prediction tasks. | Not Specified |

| Scikit-Fingerprints [7] | Python Library for Fingerprints | Provides efficient computation of molecular fingerprints (ECFP, Topological Torsion, etc.) for use with ML models like LightGBM. | Open Source |

| Dragon [1] | Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Widely used proprietary software for calculating a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors. | Proprietary |

The landscape of molecular descriptors is rich and varied, spanning from deterministic fingerprints and descriptors to learned, continuous representations. Benchmarking studies consistently show that no single representation is universally superior. While modern GNNs and consensus models can achieve top performance in specific tasks like taste prediction [5], traditional fingerprints remain remarkably competitive and can even surpass complex deep learning models in domains like peptide function prediction [7]. The emergence of data-driven descriptors from translation models offers a powerful path to capturing the fundamental semantics of molecular structure [6]. The choice of representation is, therefore, task-dependent. Researchers must weigh factors such as dataset size, computational resources, required interpretability, and the specific biological or chemical endpoint being modeled. The ongoing development and rigorous comparative analysis of these preprocessing methods for molecular descriptors will continue to be a cornerstone of innovation in cheminformatics and AI-driven drug discovery.

In the field of molecular research and drug development, the quality of machine learning outcomes depends fundamentally on the quality of the input data. Molecular descriptor datasets, often comprising thousands of calculated features, inherently suffer from noise, redundancy, and the curse of dimensionality—a phenomenon where high-dimensional data becomes sparse, making patterns harder to detect and models less effective [8] [9]. Without robust preprocessing, even the most sophisticated algorithms struggle with computational inefficiency, overfitting, and diminished interpretability. This comparative analysis examines critical preprocessing methodologies for molecular descriptor data, providing experimental validation of their performance impact and offering practical frameworks for research implementation. The systematic reduction of data complexity is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of success in quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) studies and cheminformatics applications [10] [1].

Understanding the Data Challenge: Molecular Descriptors and the Curse of Dimensionality

Molecular descriptors are mathematical representations of molecular structures and properties, serving as essential inputs for predictive modeling in cheminformatics [1]. Software tools like Mordred can calculate more than 1,800 two- and three-dimensional descriptors, transforming chemical structures into quantifiable features for machine learning applications [1]. However, this descriptive richness creates significant analytical challenges through the curse of dimensionality, where the feature space becomes increasingly sparse as dimensions grow, reducing model performance and increasing computational demands [8] [9].

The fundamental challenges in raw molecular descriptor data include:

- Noase: Irrelevant features and measurement artifacts that obscure meaningful signals, leading to models that learn noise rather than true underlying patterns [11].

- Redundancy: High multicollinearity among descriptors, where multiple features capture similar structural information, introducing instability in model coefficients and interpretations [10].

- Computational Complexity: As dimensions increase, computational requirements grow exponentially, creating practical bottlenecks in model training and hyperparameter optimization [9].

These challenges necessitate rigorous preprocessing pipelines to transform raw descriptor data into robust feature sets capable of supporting accurate, interpretable, and generalizable predictive models.

Comparative Analysis of Preprocessing Methods

Feature Selection Approaches

Feature selection techniques identify and retain the most relevant molecular descriptors while eliminating redundant or uninformative features, preserving the original feature semantics for enhanced interpretability.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods for Molecular Descriptors

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Best-Suited Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Threshold | Removes low-variance features | Simple, fast, reduces dimensionality | May discard low-variance predictive features | All descriptor types [9] |

| Correlation Analysis | Eliminates highly correlated features | Reduces multicollinearity, simple implementation | Only captures linear relationships | Continuous descriptors [10] |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Iteratively removes least important features | Model-specific, produces optimized subsets | Computationally intensive, may overfit | All descriptor types [9] |

| Mutual Information | Selects features with highest dependency | Captures non-linear relationships | Requires large sample sizes | Continuous, categorical descriptors [9] |

Feature Extraction Approaches

Feature extraction transforms original descriptors into a new, reduced set of features that capture essential information while dramatically reducing dimensionality.

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods for Molecular Descriptors

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Molecular Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Linear projection to orthogonal components | Maximizes variance, improves efficiency | Sensitive to scaling, difficult interpretation | Exploratory analysis, data compression [8] [12] |

| t-SNE | Non-linear projection preserving local similarities | Excellent cluster visualization | Computationally heavy, not for predictive modeling | High-dimensional data visualization [8] [9] |

| UMAP | Graph-based non-linear dimensionality reduction | Preserves local/global structure, faster than t-SNE | Sensitive to parameters, primarily for visualization | Visualization of complex manifolds [8] [9] |

| Autoencoders | Neural network learning compressed representations | Captures complex non-linearities | Computationally intensive, requires large data | Non-linear relationship capture [9] [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Validation

Systematic Descriptor Selection Methodology

A study demonstrated in [10] established a robust protocol for descriptor selection and model training. The methodology begins with calculating numerous molecular descriptors using specialized software, followed by systematic reduction of feature multicollinearity. This process enables discovery of new relationships between global properties and molecular descriptors while maintaining model interpretability [10].

The experimental workflow encompasses:

- Data Collection: Curating experimental data for up to 8,351 molecules from public repositories like DrugBank, PubChem, ChEMBL, and ZINC [12].

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating mathematical representations using calculators such as Mordred, which can process over 1,800 descriptors and handles large molecules efficiently [1].

- Feature Subset Selection: Applying correlation analysis and multicollinearity reduction to identify optimal descriptor subsets.

- Model Training with TPOT: Implementing the Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT) to automate model selection and hyperparameter tuning.

- Validation: Assessing model performance using independent test sets and reporting mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) metrics.

Performance Comparison Across Molecular Properties

Table 3: Experimental Performance of Preprocessed Models on Molecular Property Prediction

| Molecular Property | Dataset Size | Preprocessing Method | Performance (MAPE) | Key Descriptors Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point | 8,351 molecules | Multicollinearity reduction + TPOT | 10.5% | Constitutional, thermodynamic descriptors |

| Boiling Point | 7,892 molecules | Multicollinearity reduction + TPOT | 8.2% | Topological, electronic descriptors |

| Flash Point | 6,451 molecules | Multicollinearity reduction + TPOT | 7.8% | Structural, atomic contribution descriptors |

| Yield Sooting Index | 2,147 molecules | Multicollinearity reduction + TPOT | 9.1% | Aromaticity, functional group descriptors |

| Net Heat of Combustion | 5,923 molecules | Multicollinearity reduction + TPOT | 3.3% | Constitutional, thermodynamic descriptors |

The experimental results demonstrate that systematic preprocessing yields excellent predictive accuracy across diverse molecular properties, with MAPE ranging from 3.3% to 10.5% [10]. Importantly, the method maintains interpretability, providing scientific insights into which molecular descriptors most significantly contribute to property predictions.

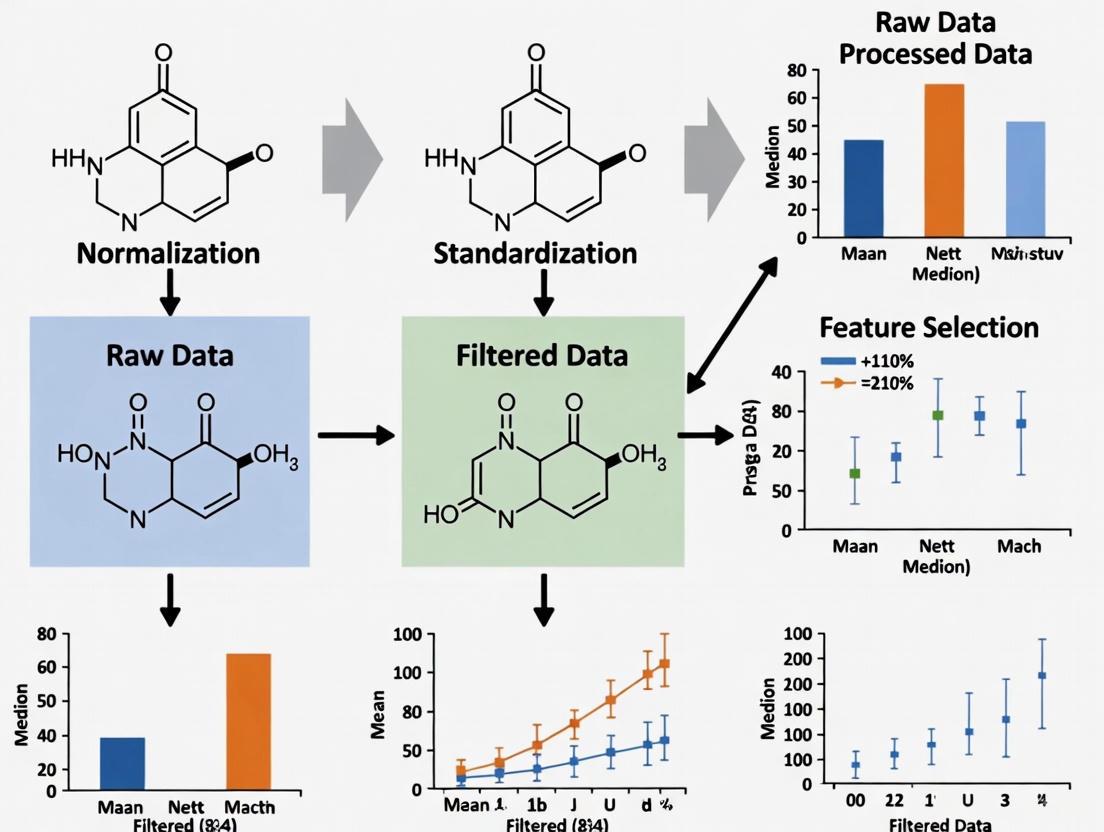

Visualizing Preprocessing Workflows

Molecular Descriptor Preprocessing Pipeline

Method Selection Framework for Molecular Data

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Descriptor Preprocessing

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mordred | Descriptor Calculator | Calculates 1,800+ 2D/3D molecular descriptors | QSAR/QSPR studies, feature generation | BSD [1] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Descriptor Calculator | Calculates 1,875 molecular descriptors and fingerprints | Cheminformatics, virtual screening | Open Source [1] |

| Scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Implements PCA, feature selection, model training | General-purpose preprocessing and modeling | BSD [11] |

| TPOT | Automated ML | Optimizes machine learning pipelines | Model selection and hyperparameter tuning | Open Source [10] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Chemical representation and manipulation | Fundamental structure processing | BSD [1] |

| UMAP | Dimensionality Reduction | Non-linear dimensionality reduction | Visualization of high-dimensional data | BSD [8] |

Preprocessing molecular descriptors is not merely a technical prerequisite but a scientifically substantive phase that critically influences model performance, interpretability, and translational impact. The experimental evidence demonstrates that systematic approaches to addressing noise, redundancy, and dimensionality can achieve excellent predictive accuracy (MAPE 3.3-10.5%) while maintaining interpretability essential for scientific discovery [10]. As molecular datasets continue to grow in scale and complexity, robust preprocessing methodologies will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating drug discovery and materials development. Future directions point toward deeper integration of domain knowledge into preprocessing pipelines, adaptive methods for streaming chemical data, and increased utilization of hybrid approaches that combine the interpretability of feature selection with the expressive power of non-linear feature extraction.

In molecular research, the transformation of raw chemical structures into quantifiable numerical representations is a foundational step for building predictive models. Molecular descriptors are defined as the final result of a logical and mathematical procedure which transforms chemical information encoded within a symbolic representation of a molecule into a useful number [13]. These descriptors form the essential variables in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies, where researchers seek to establish mathematical relationships between molecular structures and their properties or biological activities [1]. The preprocessing of these descriptors—encompassing feature selection, normalization, and data correction—is critical for developing robust, interpretable, and predictive models. These preprocessing steps ensure that the resulting models capture genuine biological or chemical relationships rather than artifacts of data collection or representation.

The molecular descriptor calculation process typically begins with symbolic representations of molecules, such as SMILES strings or molecular graphs, and applies well-defined algorithms to generate thousands of potential descriptors spanning different dimensions of chemical information [13]. These include 0D descriptors (simple counts of atoms or bonds), 1D descriptors (substructural fragments), 2D descriptors (topological indices based on molecular connectivity), and 3D descriptors (geometrical properties based on spatial coordinates) [13]. However, this raw descriptor space presents numerous analytical challenges, including high dimensionality, correlated features, varying scales, and technical artifacts, necessitating sophisticated preprocessing pipelines before model development.

Comparative Framework for Preprocessing Methods

Evaluation Metrics and Experimental Protocols

To objectively compare preprocessing techniques, researchers employ standardized evaluation protocols focusing on multiple performance dimensions. The most significant metrics include predictive accuracy (measured via cross-validation on holdout test sets), computational efficiency (calculation time and resource requirements), model interpretability (ability to extract chemically meaningful insights), and robustness (performance consistency across diverse chemical datasets). Experimental evaluations typically employ benchmark chemical datasets with known properties, such as drug activity compounds, environmental toxicity datasets, or physicochemical property collections.

In controlled comparative studies, researchers typically implement a consistent modeling algorithm (such as Random Forest or Support Vector Machines) while varying only the preprocessing methodology. The standard protocol involves: (1) calculating an extensive set of molecular descriptors using software such as Mordred, which can generate over 1800 descriptors [1]; (2) applying different preprocessing techniques to the descriptor matrix; (3) training models on identically split training sets; and (4) evaluating performance on held-out test sets using metrics like RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) for regression tasks or AUC (Area Under Curve) for classification problems. This controlled approach ensures fair comparisons between preprocessing methods.

Molecular Descriptor Software and Computational Tools

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing

| Software Tool | Descriptor Count | Preprocessing Capabilities | License | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mordred [1] | >1800 | Automated preprocessing, parallel computation | BSD (Open source) | High speed, handles large molecules, Python integration |

| Dragon [1] [13] | ~5000 | Comprehensive descriptor normalization | Proprietary | Extensive descriptor library, well-established |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [1] | 1875 | Limited built-in preprocessing | Open source | Multiple interfaces, fingerprints |

| ChemoPy [1] | 1135 | Python-based preprocessing | Open source | Integrates with Python ML stack |

| Rcpi [1] | 307 | R-based preprocessing pipeline | Open source | Integrates with R bioconductor |

These software tools employ various algorithms to compute descriptors from molecular structures. For instance, topological descriptors are derived from molecular graph representations, where atoms correspond to vertices and bonds to edges [13]. Geometric descriptors require 3D coordinate information and capture spatial molecular characteristics. The choice of software significantly impacts the available descriptor space and subsequent preprocessing requirements, with tools like Mordred demonstrating particular efficiency for large molecules and high-throughput applications [1].

Feature Selection Techniques for Molecular Descriptors

Feature selection methods aim to identify the most relevant molecular descriptors while eliminating redundant or irrelevant variables. These techniques are broadly categorized into three approaches: filter methods, wrapper methods, and embedded methods [14]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations for molecular descriptor preprocessing.

Filter methods operate independently of any machine learning algorithm, evaluating descriptors based on statistical properties such as correlation with the target variable, chi-square tests, or mutual information [14]. For molecular descriptors, common filter approaches include Pearson correlation for continuous targets (e.g., binding affinity) and chi-square or ANOVA F-value for categorical targets (e.g., active/inactive classification). These methods are computationally efficient and scalable to high-dimensional descriptor spaces, making them suitable for initial dimensionality reduction. However, they ignore feature dependencies and may select redundant descriptors that capture similar chemical information.

Wrapper methods employ a specific machine learning algorithm to evaluate descriptor subsets, using predictive performance as the selection criterion [14]. Common strategies include forward selection (iteratively adding the most improving descriptors), backward elimination (iteratively removing the least important descriptors), and recursive feature elimination. These methods can capture descriptor interactions and often yield superior predictive performance compared to filter methods. For example, Recursive Feature Elimination with Support Vector Machines has been successfully applied for gene selection in cancer classification [14]. The primary limitation is computational intensity, particularly with large descriptor sets.

Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process [14]. Techniques like LASSO regression penalize model complexity, effectively driving coefficients of irrelevant descriptors to zero. Random Forests provide built-in feature importance metrics based on how much each descriptor decreases impurity across decision trees. These methods balance computational efficiency with consideration of descriptor interactions, making them particularly valuable for QSAR modeling. Regularization parameters in embedded methods require careful tuning via cross-validation to optimize the trade-off between model complexity and performance.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methods on Molecular Datasets

| Method Category | Typical Descriptor Reduction | Computational Time | Model Accuracy | Handling Descriptor Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | 60-80% | Low | Moderate | Poor |

| Wrapper Methods | 70-90% | High | High | Excellent |

| Embedded Methods | 50-80% | Moderate | Moderate to High | Good |

Experimental Protocols for Feature Selection Evaluation

Standardized experimental protocols for evaluating feature selection methods in molecular studies involve multiple steps. Researchers typically begin with a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors calculated from a diverse chemical dataset with known experimental properties. The protocol applies different feature selection techniques to this full descriptor set, then builds models using the selected descriptors and evaluates performance on held-out test compounds.

A robust evaluation includes stability analysis—assessing how consistently a feature selection method identifies important descriptors across different chemical subsets or data perturbations. This is particularly important for molecular descriptors, as unstable selections may indicate overfitting or limited generalizability across chemical space. Additionally, researchers should validate that selected descriptors align with chemical knowledge, providing interpretable structure-property relationships rather than black-box predictions.

Recent innovations include hybrid approaches that combine filter and embedded methods, using fast filter techniques for initial dimensionality reduction followed by more sophisticated embedded methods for final selection. This strategy balances computational efficiency with performance optimization, particularly valuable for large-scale molecular datasets with thousands of compounds and descriptors.

Normalization and Scaling Techniques

Technical Comparison of Normalization Approaches

Normalization techniques address the challenge of molecular descriptors existing on different measurement scales, which can bias machine learning algorithms toward high-magnitude features. Different normalization methods offer distinct advantages depending on the distribution characteristics of the molecular descriptors and the presence of outliers.

Min-Max Scaling transforms descriptor values to a fixed range, typically [0, 1], by subtracting the minimum value and dividing by the range [15]. This approach preserves the original distribution shape while ensuring consistent scaling across all descriptors. However, Min-Max Scaling is highly sensitive to outliers, as extreme descriptor values can compress the majority of transformed values into a narrow interval. This method is most appropriate for molecular descriptors with bounded ranges and minimal outliers.

Standardization (Z-score normalization) centers descriptor values by subtracting the mean and scaling to unit variance [15]. This approach produces descriptors with mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1, satisfying the distributional assumptions of many statistical models and machine learning algorithms. Standardization is less sensitive to outliers than Min-Max Scaling but assumes an approximately normal distribution for optimal performance. For molecular descriptors with naturally skewed distributions, alternative approaches may be preferable.

Robust Scaling utilizes median and interquartile range (IQR) instead of mean and standard deviation [15]. This approach minimizes the influence of outliers in the descriptor values, making it suitable for molecular datasets with extreme values or technical artifacts. Robust Scaling is particularly valuable for 3D molecular descriptors that may exhibit high variability across conformational space or for datasets combining diverse chemical classes with different descriptor value ranges.

Absolute Maximum Scaling divides each descriptor value by the maximum absolute value, resulting in a range of [-1, 1] [15]. While computationally simple, this method is highly sensitive to outliers and rarely represents the optimal choice for molecular descriptor preprocessing unless dealing with sparse descriptor matrices in specialized applications.

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of Normalization Techniques for Molecular Descriptors

| Normalization Method | Formula | Outlier Sensitivity | Optimal Data Distribution | Molecular Application Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min-Max Scaling [15] | (X - Xmin)/(Xmax - X_min) | High | Uniform, bounded | Constitutional descriptors, counts | ||

| Standardization [15] | (X - μ)/σ | Moderate | Approximately normal | Electronic descriptors, properties | ||

| Robust Scaling [15] | (X - median)/IQR | Low | Skewed, outlier-prone | 3D descriptors, kinetic parameters | ||

| Absolute Maximum Scaling [15] | X/max( | X | ) | High | Sparse features | Spectral fingerprints, binary features |

Experimental Insights on Normalization Efficacy

Controlled experiments evaluating normalization techniques for molecular descriptors demonstrate that the optimal approach depends on both the descriptor characteristics and the modeling algorithm. Tree-based methods like Random Forests are generally insensitive to descriptor scaling, while distance-based algorithms (K-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Machines with RBF kernels) and gradient-based optimization (neural networks, logistic regression) show significant performance variations with different normalization strategies.

In benchmark studies using diverse QSAR datasets, Robust Scaling frequently outperforms other methods when applied to molecular descriptors derived from heterogeneous chemical series. This advantage stems from the method's resilience to outlier values that commonly occur when descriptors capture extreme molecular features or when datasets combine multiple chemical classes. Standardization demonstrates superior performance for normally distributed physicochemical properties, while Min-Max Scaling proves effective for bounded descriptors like molecular fingerprints or binary structural indicators.

The normalization sequence within the preprocessing pipeline also impacts performance. Research indicates that normalizing descriptors after feature selection but before model training generally yields superior results compared to normalizing the entire descriptor set initially. This approach prevents leakage of information from the test set during the normalization process and avoids amplifying noise from irrelevant descriptors.

Data Correction Methods

Technical Artifact Correction and Quality Control

Data correction methods address systematic biases, technical artifacts, and quality issues in molecular descriptor data. These approaches include handling missing descriptor values, correcting for experimental artifacts, and identifying erroneous measurements that could distort structure-property relationships.

In molecular descriptor datasets, missing values commonly arise when calculation algorithms fail for certain molecular structures or when descriptors are undefined for specific chemical classes. Common strategies include descriptor removal (eliminating descriptors with excessive missing values), molecular removal (excluding compounds with missing descriptors), or imputation (estimating plausible values based on available data). For QSAR applications, imputation methods range from simple approaches (mean/median substitution) to sophisticated modeling techniques (k-nearest neighbors imputation based on similar compounds). The optimal approach depends on the missing data mechanism and proportion, with more advanced methods required when data are not missing completely at random.

Technical artifact correction addresses systematic biases introduced by descriptor calculation algorithms or experimental measurement processes. For example, certain topological indices may exhibit numerical instability for specific molecular graph configurations, while 3D descriptors may show conformational dependence that introduces noise. Correction methods include mathematical transformations to stabilize variance, alignment procedures to account for different molecular conformations, and batch effect correction when descriptors are calculated using different software versions or computational environments.

Quality control procedures identify and address outliers and erroneous values in molecular descriptor datasets. Statistical approaches include median absolute deviation (MAD) methods that flag descriptor values exceeding a threshold (typically 3-5 MADs from the median) as potential outliers [16]. For molecular data, domain knowledge should complement statistical criteria, as extreme descriptor values may represent legitimate chemical features rather than measurement errors. Robust statistical techniques that minimize outlier influence during model building provide an alternative to outright removal of suspected outliers.

Advanced Correction in Specialized Applications

In emerging applications like single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, specialized data correction methods have been developed that offer insights for molecular descriptor preprocessing. Residuals-based normalization approaches first identify stable features (genes with minimal biological variation in the scRNA-seq context), then use these features to estimate and correct technical biases [17]. This conceptual framework could extend to molecular descriptors by identifying "stable" descriptors that show minimal variation across related compounds, then using these to correct systematic errors.

Variance stabilization transformations represent another advanced correction technique, particularly valuable for count-based molecular descriptors or descriptors with mean-variance relationships. These transformations ensure that variance remains relatively constant across different magnitude levels, satisfying the homoscedasticity assumption of many statistical tests and modeling approaches. For molecular descriptors exhibiting Poisson-like or quasi-Poisson mean-variance relationships (common in count descriptors like atom-type occurrences), specialized variance stabilization approaches have been developed [17].

In high-performance computing environments, cloud-based distributed computing frameworks enable efficient application of data correction methods to large-scale molecular descriptor datasets [18]. These approaches partition the computational workload across multiple nodes, significantly reducing processing time for resource-intensive correction algorithms like iterative imputation or robust covariance estimation. Implementation considerations include data security for proprietary chemical structures, computational overhead for data distribution and aggregation, and algorithm-specific parallelization strategies.

Integrated Preprocessing Workflows

Optimal Sequencing of Preprocessing Steps

The sequence of preprocessing operations significantly impacts molecular descriptor quality and subsequent modeling performance. Based on comparative studies, the optimal workflow follows: (1) data correction and cleaning, (2) feature selection, and (3) normalization/scaling. This sequence ensures that technical artifacts and missing values are addressed before selection, preventing biased selection of descriptors with systematic errors, while normalization after selection avoids amplifying noise from irrelevant descriptors.

Evidence from single-cell genomics research supports performing feature selection before normalization, contrary to traditional workflows [17]. In this revised approach, feature selection identifies both highly variable descriptors (capturing meaningful chemical differences) and stable descriptors (reflecting technical biases). The stable descriptors then inform the normalization process, enabling more targeted correction of systematic errors. For molecular descriptors, this could translate to identifying descriptors that primarily reflect calculation artifacts rather than genuine chemical variation.

Implementation considerations include iterative refinement, where preliminary models inform additional preprocessing adjustments. For instance, analysis of model residuals may reveal patterns indicating incomplete normalization or uncorrected artifacts, guiding additional preprocessing steps. This cyclic approach to preprocessing recognizes that optimal parameters may be dataset-dependent and require empirical determination rather than rigid application of standardized protocols.

Workflow Visualization and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the optimized preprocessing workflow for molecular descriptors, integrating feature selection, normalization, and data correction into a coordinated pipeline:

Diagram Title: Molecular Descriptor Preprocessing Workflow

Implementation of this integrated workflow requires both computational tools and domain knowledge. The "Scientist's Toolkit" for molecular descriptor preprocessing includes both software resources and methodological approaches:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Mordred [1], Dragon [13] | Generate raw molecular descriptors from chemical structures |

| Feature Selection Implementation | scikit-learn feature_selection [14], FSelector (R) | Apply filter, wrapper, and embedded selection methods |

| Normalization Libraries | scikit-learn preprocessing [15] | Implement scaling and normalization techniques |

| Computational Frameworks | Cloud computing platforms [18] | Enable distributed processing for large descriptor sets |

| Quality Control Metrics | Median Absolute Deviation [16] | Identify outliers and technical artifacts |

Preprocessing of molecular descriptors through feature selection, normalization, and data correction represents a critical determinant of success in QSPR/QSAR modeling and chemical informatics. Comparative analyses demonstrate that the optimal preprocessing strategy depends on multiple factors, including descriptor characteristics, dataset size, modeling objectives, and computational resources. Robust scaling combined with embedded feature selection generally provides strong performance across diverse molecular datasets, though specialized applications may benefit from method customization.

Future directions in molecular descriptor preprocessing include increased automation through intelligent workflow systems that dynamically select preprocessing methods based on dataset characteristics. Integration with cloud computing infrastructures enables application of more computationally intensive methods to larger chemical datasets [18]. Additionally, specialized preprocessing approaches for emerging descriptor types, such as those derived from quantum chemical calculations or molecular dynamics simulations, will continue to evolve as these applications mature.

The comparative framework presented here provides researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting and implementing preprocessing methods tailored to their specific molecular modeling challenges. By applying rigorous preprocessing protocols aligned with both statistical principles and chemical knowledge, researchers can extract maximum value from molecular descriptor data, advancing drug discovery, materials design, and chemical optimization efforts.

The Impact of Preprocessing on Downstream QSAR Model Performance and Interpretability

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a cornerstone in modern drug discovery, enabling the prediction of biological activity and pharmacokinetic properties of chemical compounds from their molecular structures [19] [20]. The foundational principle of QSAR lies in establishing a mathematical relationship between molecular descriptors—numerical representations of chemical structures—and a biological endpoint of interest [21]. While the choice of machine learning algorithm is crucial, the preprocessing of these molecular descriptors profoundly influences the reliability, predictive power, and interpretability of the final model [22]. Preprocessing transforms raw descriptor data into a refined set of features that can more effectively train a model, impacting everything from computational efficiency to the model's ability to generalize to new compounds. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key preprocessing methodologies, evaluating their impact on downstream QSAR model performance within the broader context of comparative analysis of molecular descriptors research.

Comparative Analysis of Preprocessing Techniques

Feature Selection Methods

Feature selection techniques aim to reduce data dimensionality by selecting a subset of relevant molecular descriptors, thereby mitigating overfitting and enhancing model interpretability [22]. The table below compares the performance of different feature selection approaches based on their application in predicting oral absorption.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methodologies in QSAR Modeling

| Feature Selection Approach | Description | Reported Impact on Model Performance | Key Findings / Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Stage Preprocessing (Filter Methods) | A pre-processing step selects a descriptor subset, followed by model building [22]. | Higher model accuracy in most cases for oral absorption prediction [22]. | Using the top 20 molecular descriptors from Random Forest predictor importance yielded the most accurate C&RT classification model [22]. |

| One-Stage (Embedded) Approach | The model algorithm (e.g., C&RT) performs feature selection internally during training [22]. | Lower model accuracy compared to the two-stage approach for oral absorption prediction [22]. | Can be inadequate as fewer compounds are available for selection further down a decision tree, potentially leading to suboptimal descriptor choices [22]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Recursively removes the least important features and builds a model on the remaining features [23]. | (Specific quantitative data not provided in search results; listed as a key technique) [23]. | A core technique for feature selection in molecular descriptor preprocessing [23]. |

| Forward Selection / Backward Elimination | Stepwise methods that add or remove one feature at a time based on model performance [23]. | (Specific quantitative data not provided in search results; listed as a key technique) [23]. | A core technique for feature selection in molecular descriptor preprocessing [23]. |

Data Normalization and Feature Engineering

Beyond feature selection, other preprocessing steps are critical for preparing molecular descriptor data for modeling.

- Data Normalization: Molecular descriptors often exist on vastly different numerical scales (e.g., molecular weight vs. count of hydrogen bond donors). Normalization, such as the min-max method, rescales all features to a consistent range, which is essential for the stable training of many machine learning algorithms [19]. The min-max method rescales a component ( xl ) to ( x'l ) using the formula: ( xl' = (xl - \mathtt{min}{xl}) / (\mathtt{max}{xl} - \mathtt{min}{xl}) ) [19].

- Data-Driven Descriptor Generation: Advanced, unsupervised deep learning methods can generate novel molecular descriptors. For instance, translation-based models can learn continuous molecular descriptors by translating between different molecular representations (e.g., InChI to SMILES). These data-driven descriptors have shown competitive performance in QSAR modeling and virtual screening tasks compared to human-engineered fingerprints [6].

Experimental Protocols for Preprocessing Evaluation

To ensure the reproducibility and robust evaluation of preprocessing methods, the following experimental protocols can be adopted.

Protocol for Evaluating Feature Selection Techniques

This protocol is derived from studies that compared one-stage and two-stage feature selection methods for predicting oral absorption [22].

- Dataset Curation: Collect a set of compounds with measured biological activity (e.g., oral absorption percentage) and calculated molecular descriptors.

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute a wide array of molecular descriptors for each compound using software such as Mordred [1] or PaDEL-Descriptor [1].

- Application of Feature Selection Methods:

- One-Stage Approach: Apply a decision-tree-based algorithm (e.g., C&RT) directly to the full set of descriptors, allowing the algorithm's embedded feature selection to operate.

- Two-Stage Approach:

- Stage 1 (Pre-processing): Apply a filter feature selection method (e.g., Random Forest predictor importance) to the training set to select a top-ranked subset of descriptors (e.g., the top 20).

- Stage 2 (Model Building): Use the C&RT algorithm to build a model using only the pre-selected subset of descriptors from Stage 1.

- Model Validation: Partition the dataset into training and test sets. Construct models on the training set and evaluate their prediction accuracy on the held-out test set. Use techniques like cross-validation and data randomization (Y-scrambling) to validate model robustness and avoid chance correlations [22] [21].

- Performance Comparison: Compare the accuracy and interpretability of models generated by the one-stage and two-stage approaches.

General QSAR Preprocessing and Modeling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard QSAR pipeline, highlighting the crucial preprocessing stages within the broader modeling context.

Diagram Title: QSAR Workflow with Preprocessing Stages

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Resources for Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing

| Tool / Resource | Type | Key Function in Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|

| Mordred | Software | Calculates a comprehensive set of >1800 2D and 3D molecular descriptors. Known for high speed and ease of use as a Python package [1]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Another widely used open-source calculator for 1875 molecular descriptors and fingerprints [1]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | A core open-source toolkit for cheminformatics; often used as a dependency for descriptor calculation and handling molecular data [1]. |

| Random Forest | Algorithm | Used not only for modeling but also as a filter method for feature selection by ranking predictor importance [22]. |

| C&RT (Classification and Regression Trees) | Algorithm | A decision-tree algorithm with an embedded feature selection mechanism; used to compare one-stage and two-stage selection efficacy [22]. |

| ECFP (Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints) | Molecular Fingerprint | A circular structural fingerprint widely used to represent molecular structures in QSAR studies and similarity searching [24]. |

The preprocessing of molecular descriptors is not merely a preliminary step but a pivotal factor determining the success of a QSAR modeling campaign. Empirical evidence demonstrates that a two-stage feature selection approach, which involves a dedicated pre-processing step to filter descriptors, frequently yields models with superior predictive accuracy and interpretability compared to relying on a model's internal, one-stage selection process [22]. The careful application of techniques such as data normalization, feature selection, and even the generation of novel data-driven descriptors, provides a robust foundation for building QSAR models that are both predictive and insightful. As the field advances with more complex descriptors and algorithms, the role of systematic and comparative preprocessing will remain essential for extracting meaningful structure-activity relationships from chemical data.

A Practical Guide to Preprocessing Techniques and Their Implementation

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Scattering in Spectral Data

- Theoretical Foundations of SNV and MSC

- Comparative Analysis: SNV vs. MSC

- Experimental Protocols and Workflows

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

- Conclusion and Recommendations

In vibrational spectroscopy, including Near-Infrared (NIR) and Raman techniques, the recorded spectra are a complex mixture of chemical and physical information. The chemical information, derived from light absorption by molecular bonds, is often the primary analytical target. However, unwanted physical light-scattering effects caused by variations in particle size, sample packing density, and path length can obscure these chemical signals [25] [26]. These scattering effects manifest in spectra as additive baseline offsets (shifts along the intensity axis), multiplicative scaling (changes in spectral slope), and more complex wavelength-dependent variations that can tilt or curve the baseline [26]. If left uncorrected, these variations can severely degrade the performance of subsequent quantitative analysis and machine learning models, making accurate compound identification or concentration prediction challenging [27]. Filter methods like Standard Normal Variate (SNV) and Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) were developed explicitly to separate these physical scattering effects from the chemical absorbance information [28].

Theoretical Foundations of SNV and MSC

Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC)

MSC is a reference-spectrum-based method that aims to correct scattering by aligning each individual spectrum to an ideal reference, typically the mean spectrum of the dataset [25] [28]. The core assumption is that the average spectrum reasonably approximates a scattering-free spectrum, as random scattering effects vary from sample to sample.

The mathematical correction is a two-step process performed for each spectrum ( X_i ):

- Linear Regression: The spectrum ( Xi ) is regressed against the reference mean spectrum ( X{m} ) using ordinary least squares: ( Xi \approx ai + bi \cdot X{m} ). The intercept ( ai ) models the additive scattering (baseline shift), and the slope ( bi ) models the multiplicative scattering (pathlength or particle size effect) [25] [28].

- Correction Application: The corrected spectrum ( X{i}^{msc} ) is then calculated as: ( X{i}^{msc} = (Xi - ai) / b_i ) [25] [28]. This step effectively removes the estimated additive and multiplicative components, leaving behind the chemically relevant absorbance features.

Standard Normal Variate (SNV)

SNV is an individual-spectrum-based correction method. Unlike MSC, it operates on each spectrum independently without requiring a reference spectrum, making it less sensitive to outliers within the dataset [28].

The SNV correction for a single spectrum ( X_i ) also involves two conceptual steps:

- Mean Centering: The spectrum is centered by subtracting its own mean value ( \bar{Xi} ): ( X{i,centered} = Xi - \bar{Xi} ). This addresses the additive scattering component [28].

- Scaling by Standard Deviation: The mean-centered spectrum is then scaled by its own standard deviation ( \sigmai ): ( X{i}^{snv} = (Xi - \bar{Xi}) / \sigma_i ) [28]. This step corrects for the multiplicative scattering component, effectively putting all spectra on a similar scale with unit variance.

Comparative Analysis: SNV vs. MSC

The choice between SNV and MSC depends on the dataset characteristics and the analytical goals. The following table provides a structured comparison based on theoretical and practical considerations.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of SNV and MSC Preprocessing Methods

| Feature | Standard Normal Variate (SNV) | Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Individual, reference-free normalization [28] | Correction based on a reference spectrum (usually the dataset mean) [25] [28] |

| Mathematical Approach | Row-wise autoscaling (mean-centering followed by scaling to unit variance) [28] | Linear regression of each spectrum against a reference, followed by correction using slope and intercept [25] [28] |

| Handling of Additive Effects | Corrected via mean-centering [28] | Corrected via subtraction of the regression intercept ( a_i ) [25] |

| Handling of Multiplicative Effects | Corrected via scaling by standard deviation [28] | Corrected via division by the regression slope ( b_i ) [25] |

| Primary Advantage | Robust to outliers in the dataset; simple and does not require a "good" reference [28] | Relates all spectra to a common reference, which can be physically meaningful [28] |

| Primary Disadvantage | May remove some chemically relevant variance if it correlates with physical properties | Performance is dependent on the quality of the reference spectrum; can be skewed by outliers [28] |

| Output Interpretation | Spectra are scaled to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. | Corrected spectra are an estimate of the ideal, scattering-free chemical absorbance. |

| Typical Result | Often nearly identical to MSC, as the two methods are related by a linear transformation [28] | Often nearly identical to SNV, as the two methods are related by a linear transformation [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing SNV and MSC follows a systematic workflow. The diagram below outlines the key decision points and steps for applying these preprocessing techniques to a spectral dataset.

Spectral Preprocessing Workflow

A practical demonstration of this workflow can be found in a study using a NIR reflectance dataset of 50 fresh peach samples [28]. The experimental protocol is as follows:

- Data Acquisition: NIR reflectance spectra were collected over the wavelength range of 1100 nm to 2300 nm (at 2 nm intervals).

- Data Loading and Definition: The spectral data and corresponding wavelength array were loaded into a Python environment using the

pandaslibrary. - Preprocessing Application:

- MSC Protocol: The mean spectrum of the entire dataset was calculated and used as the reference. Each spectrum was then mean-centered and regressed against this reference. The corrected spectrum was obtained by subtracting the intercept and dividing by the slope of the regression line [28].

- SNV Protocol: For each spectrum individually, the mean absorbance value was calculated and subtracted from the spectrum. The result was then divided by the standard deviation of the absorbance values across all wavelengths for that specific spectrum [28].

- Visualization and Comparison: The original, MSC-corrected, and SNV-corrected spectra were plotted for visual inspection. The results demonstrated that for this well-behaved dataset, both MSC and SNV produced visually identical corrected spectra, effectively removing baseline variations and enhancing spectral features related to chemical composition [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Building and validating preprocessing methods requires a combination of standard datasets, software tools, and computational resources. The following table details key components for a research toolkit in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Spectral Preprocessing Research

| Tool / Material | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Spectral Datasets | Provides benchmark data for developing, testing, and comparing preprocessing methods and algorithms. | NIST SRD 35 (IR) [29], Publicly available NIR datasets (e.g., peach spectra [28]) |

| Programming Languages & Libraries | Provides the computational environment for implementing algorithms and performing data analysis. | Python with NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn [28] |

| Reference Materials | Physical standards with known properties used for instrument calibration and method validation. | Certified reference materials (CRMs) specific to the analyte and matrix (e.g., pharmaceutical powders) |

| Spectral Preprocessing Software | Software packages, often commercial, that provide validated and user-friendly implementations of algorithms. | Various chemometrics software packages (e.g., CAMO's The Unscrambler, Eigenvector's PLS_Toolbox) |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) or Cloud Resources | Computational resources for handling large-scale spectral datasets and running complex machine learning models. | Local HPC clusters, Cloud computing platforms (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure) |

SNV and MSC are foundational techniques for mitigating scattering effects in spectral data. While their mathematical approaches differ—MSC relying on a reference spectrum and SNV operating on each spectrum individually—they often yield remarkably similar results because they both target the same underlying additive and multiplicative scatter phenomena [28].

The choice between them should be guided by the nature of the dataset:

- Use MSC when a reliable, representative reference spectrum is available or can be constructed. This is often the case with controlled, high-quality datasets where the mean spectrum is a good approximation of the true chemical signal [28].

- Use SNV when the dataset contains potential outliers or when a valid reference spectrum is difficult to define. Its independence from a global reference makes it more robust in such scenarios [28].

For critical applications, the best practice is to empirically evaluate both methods (and their potential combinations with derivatives) within the specific modeling workflow, selecting the one that yields the most accurate and robust predictive model [26]. As the field advances, these classic methods continue to serve as vital preprocessing steps, enabling machine learning models to extract clearer chemical insights from complex spectral data.

In the field of cheminformatics and molecular design, researchers routinely calculate over 1,800 molecular descriptors to characterize chemical structures for Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models [1]. This high-dimensional data presents significant challenges for model interpretation, computational efficiency, and overfitting. Wrapper methods address these challenges by selecting optimal feature subsets based on their actual impact on model performance, unlike filter methods that rely solely on statistical properties [30]. For drug development professionals working with molecular descriptors such as those generated by Mordred software, wrapper methods provide a sophisticated approach to identify the most relevant structural characteristics predictive of biological activity, toxicity, or other properties of interest [1] [31].

Wrapper methods are characterized by their model-dependent nature, iterative selection process, and use of performance-based evaluation [30]. These methods treat feature selection as a search problem where different feature combinations are evaluated through the lens of a specific machine learning algorithm. This approach comes with increased computational costs but typically results in feature sets that yield better predictive performance for the chosen model [32]. For molecular descriptor research, this means selected features maintain stronger relevance to the target property, whether predicting protein binding affinity, solubility, or other pharmacological characteristics.

Theoretical Foundations of Wrapper Methods

Core Principles and Mechanism

Wrapper methods operate on a fundamental principle: the optimal feature subset is determined by how well it improves the performance of a specific machine learning algorithm [30]. Unlike filter methods that assess features independently of the model, wrapper methods incorporate the model as an integral component of the selection process [33]. This model-dependent approach allows wrapper methods to capture complex interactions between features and the learning algorithm, typically resulting in better predictive performance despite higher computational requirements [30] [32].

The mechanism follows an iterative search process that evaluates different feature combinations against a predetermined evaluation criterion [30]. For regression problems in molecular descriptor research, this criterion might include p-values, R-squared, or Adjusted R-squared values, while classification tasks may use accuracy, precision, recall, or f1-score [32]. The process continues until an optimal feature subset is identified, balancing model complexity with predictive capability.

Comparative Framework with Other Feature Selection Methods

Table: Comparison of Feature Selection Techniques

| Method Type | Basis for Selection | Computational Cost | Model Dependency | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Statistical measures (correlation, chi-square, variance) | Low | Independent | Fast execution; Model-agnostic |

| Wrapper Methods | Model performance metrics | High | Dependent | Captures feature interactions; Optimized for specific algorithm |

| Embedded Methods | Built-in feature importance during model training | Moderate | Integrated | Balanced approach; Less prone to overfitting |

Wrapper methods distinguish themselves from filter and embedded approaches through their direct optimization for a specific predictive algorithm [34] [33]. While filter methods like correlation analysis or chi-square tests offer speed and simplicity, they may miss complex feature interactions relevant to the model. Embedded methods such as LASSO or tree-based importance perform selection during model training, offering a middle ground [34]. For molecular descriptor research, where the relationship between structural features and biological activity can be complex and non-linear, wrapper methods provide particularly valuable insights by tailoring feature selection to the specific analytical model being developed.

Comprehensive Analysis of Primary Wrapper Techniques

Forward Selection

Forward selection follows an incremental approach to feature selection, beginning with an empty set and progressively adding the most contributive features [35] [32]. The algorithm starts by evaluating all possible single-feature models, selecting the one that provides the greatest improvement to the model according to a predefined criterion (e.g., lowest p-value or highest accuracy). In subsequent iterations, the method tests each remaining feature in combination with the already-selected features, adding the one that yields the most significant performance improvement. This process continues until no remaining features provide statistically significant enhancement to the model [32].

In the context of molecular descriptor research, forward selection might begin with basic descriptors like molecular weight or atom count, progressively adding more complex descriptors such as topological indices or quantum mechanical properties. The key advantage lies in its ability to manage computational load by considering progressively fewer feature combinations as the process continues [32]. However, a significant limitation is its inability to reassess previously selected features—once a descriptor is included, it remains in the final model regardless of whether it becomes redundant after the introduction of other features [35].

Backward Elimination

Backward elimination operates in the reverse direction of forward selection, beginning with a full model containing all available features and iteratively removing the least significant ones [35] [32]. The process starts by fitting a model with all potential molecular descriptors, identifying the feature with the highest p-value (or lowest contribution metric), and removing it if it exceeds a predetermined significance threshold. The model is refit with the remaining features, and the process repeats until all remaining features demonstrate statistical significance [32].

This approach is particularly valuable in molecular descriptor research when researchers want to ensure they consider all potential descriptors initially, especially when prior knowledge suggests certain structural features might be relevant. The main advantage of backward elimination is its comprehensive initial assessment of all features, which prevents potentially important descriptors from being overlooked at the outset [35]. The primary drawback mirrors that of forward selection: once a feature is removed, it cannot be reconsidered, potentially excluding descriptors that might become significant in combination with other features [35].

Stepwise Selection

Stepwise selection represents a hybrid approach that combines elements of both forward and backward methods [35] [36]. After each forward addition step, the algorithm performs a backward review to assess whether any previously included features have become redundant given the newly added feature. This bidirectional checking allows the method to address the primary limitation of standard forward selection by allowing for the removal of features that no longer contribute significantly to model performance [35].

For molecular descriptor research, stepwise selection offers a particularly robust approach as it can capture the complex interdependencies between structural descriptors. A topological index might initially appear significant but could become redundant when a more comprehensive 3D descriptor is added to the model. Stepwise selection automatically detects these scenarios, resulting in more parsimonious feature sets. This method generally outperforms unidirectional approaches in handling multicollinearity among molecular descriptors, as it continuously re-evaluates the contribution of all selected features throughout the process [35].

Recursive Feature Elimination

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) represents a more sophisticated wrapper approach that employs a greedy optimization strategy to select features [35] [34]. Rather than building up or reducing features incrementally, RFE works by repeatedly constructing models and eliminating the least important features based on model-specific importance metrics (e.g., regression coefficients or feature importance scores). The process continues until all features have been ranked, at which point the optimal subset can be selected [34].

In practice, RFE might begin with all 1,800+ descriptors available in Mordred, fit a model, eliminate the bottom 10% of features based on importance scores, refit the model with the remaining features, and repeat until a predetermined number of features remains [1] [34]. This approach is particularly effective for molecular descriptor research because it can accommodate complex machine learning models like Support Vector Machines or Random Forests that may capture non-linear relationships between structural features and biological activity. However, RFE can be computationally intensive and potentially unstable, as feature importance may vary across different data subsamples [35].

Table: Comparison of Primary Wrapper Method Performance Characteristics

| Method | Computational Efficiency | Feature Interaction Handling | Risk of Local Optima | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Selection | High (especially with many features) | Limited | Moderate | Initial exploration; High-dimensional descriptor spaces |

| Backward Elimination | Lower (especially with many features) | Good | Moderate | When domain knowledge exists; Smaller descriptor sets |

| Stepwise Selection | Moderate | Better | Lower | Balanced approach; Multicollinear descriptors |

| Recursive Feature Elimination | Low to Moderate | Best | Lower | Complex models; Stable feature sets |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Workflow Diagram for Wrapper Method Implementation

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Implementing wrapper methods for molecular descriptor selection requires a systematic approach to ensure robust and reproducible results. The following protocol outlines key steps:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing Before applying wrapper methods, molecular descriptor data must be thoroughly preprocessed. This includes handling missing values—particularly important for 3D descriptors that may be unavailable for large molecules [1]—and standardizing descriptor values to ensure comparable scales. For Mordred-generated descriptors, which include both 2D and 3D molecular characteristics, initial filtering may remove zero-variance descriptors that offer no discriminatory power. The dataset should then be divided into training, validation, and test sets, typically using an 80/10/10 split to enable proper evaluation of selected feature subsets [1] [32].

Model Configuration and Evaluation Framework The choice of machine learning algorithm for the wrapper method should align with the research objective. For QSPR regression tasks, linear models with p-value evaluation may be appropriate, while classification tasks like activity prediction may benefit from logistic regression or Support Vector Machines [32] [33]. The evaluation framework must employ cross-validation (typically 5- or 10-fold) to avoid overfitting during the feature selection process. Performance metrics should be selected based on the problem type: R-squared and Adjusted R-squared for regression, accuracy and F1-score for classification tasks [32].

Implementation Example Using Python

For molecular descriptor data stored in a DataFrame X with target variable y, forward selection can be implemented as follows [32]:

Similar implementations can be developed for backward elimination (setting forward=False) and stepwise selection (setting floating=True) [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Essential Tools for Molecular Descriptor Research with Wrapper Methods

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Mordred, PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon | Generate molecular descriptors from chemical structures | Mordred calculates 1800+ 2D/3D descriptors; Open-source BSD license [1] |

| Programming Environments | Python (scikit-learn, mlxtend), R (olsrr) | Implement wrapper methods and machine learning models | Mlxtend provides SequentialFeatureSelector; olsrr offers stepwise implementation [32] [36] |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn, caret (R), tidymodels (R) | Build predictive models for evaluation in wrapper methods | Provide regression, classification algorithms and evaluation metrics [34] [32] |

| Visualization Tools | matplotlib, seaborn, ggplot2 | Visualize feature selection progress and performance | Plot accuracy vs. feature count; Compare method performance [33] |

| Chemical Structure Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel | Preprocess chemical structures before descriptor calculation | Handle aromaticity, hydrogen addition, stereochemistry [1] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Computational Efficiency Benchmarks

The computational demands of wrapper methods vary significantly based on the approach and the initial number of molecular descriptors. Forward selection generally offers the best efficiency for high-dimensional descriptor spaces, as it begins with simple models and gradually increases complexity [32]. Backward elimination becomes computationally intensive with large descriptor sets (e.g., 1,800+ Mordred descriptors) since it must begin with a full model [36]. Stepwise selection typically falls between these extremes, while Recursive Feature Elimination can be most demanding due to repeated model building [35] [34].