CRISPR-Cas9 Beta-Globin Mutation Correction: From Molecular Basis to Clinical Therapy in Sickle Cell Disease

This comprehensive review synthesizes current advancements in CRISPR-based gene editing strategies for correcting the beta-globin mutation in sickle cell disease (SCD).

CRISPR-Cas9 Beta-Globin Mutation Correction: From Molecular Basis to Clinical Therapy in Sickle Cell Disease

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current advancements in CRISPR-based gene editing strategies for correcting the beta-globin mutation in sickle cell disease (SCD). Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, the article explores the molecular pathology of SCD, detailing various CRISPR methodologies including direct HBB correction, BCL11A targeting for fetal hemoglobin reactivation, and emerging base/prime editing approaches. It critically examines delivery challenges, safety considerations, and optimization strategies, while presenting clinical validation data from approved therapies like Casgevy. The analysis compares CRISPR approaches with conventional treatments and other gene therapy platforms, addressing technical hurdles, manufacturing scalability, and future directions for clinical translation of these transformative genetic medicines.

The Molecular Pathology of Sickle Cell Disease and CRISPR Therapeutic Rationale

The β-globin gene (HBB) encodes the beta-globin subunit of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Normal adult hemoglobin (HbA) is a tetramer consisting of two alpha-globin and two beta-globin chains, each associated with a heme group that binds oxygen [1]. Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a monogenetic disorder caused by a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the HBB gene. This A>T point mutation occurs in the sixth codon of the β-globin gene, resulting in the substitution of valine for glutamic acid at position 6 in the beta-globin chain (Glu6Val, E6V) [2] [1]. This specific genetic alteration leads to the production of an abnormal hemoglobin variant known as hemoglobin S (HbS).

The substitution of a hydrophilic amino acid (glutamic acid) with a hydrophobic one (valine) creates a hydrophobic interaction site on the surface of the beta-globin chain. Under deoxygenated conditions, these abnormal hemoglobin molecules polymerize into rigid, insoluble strands that deform red blood cells into the characteristic sickle shape [2]. These sickled cells exhibit decreased flexibility and increased adhesion to vascular endothelium, leading to microvascular occlusion, tissue ischemia, and both acute and chronic organ damage [2]. Additionally, sickled erythrocytes have a significantly shorter lifespan (10-20 days versus 120 days for normal red blood cells), resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia [2].

The clinical manifestations of SCD are primarily driven by these pathophysiological processes and include vaso-occlusive pain crises, acute chest syndrome, stroke, and progressive organ damage [2]. Interestingly, despite being a monogenic disorder, SCD exhibits considerable phenotypic heterogeneity influenced by genetic modifiers such as co-inheritance of alpha-thalassemia and polymorphisms in genes affecting fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production, including BCL11A and HBS1L-MYB [2].

Table 1: Genetic and Biochemical Basis of Sickle Cell Disease

| Aspect | Normal Physiology | Sickle Cell Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| HBB Genotype | Two normal β-globin alleles | Homozygous Glu6Val (E6V) point mutation |

| Hemoglobin Type | Hemoglobin A (HbA) | Hemoglobin S (HbS) |

| Amino Acid Position 6 | Glutamic acid (hydrophilic) | Valine (hydrophobic) |

| Red Blood Cell Shape | Biconcave disc | Sickled crescent (when deoxygenated) |

| Primary Pathology | Normal oxygen transport | Hemoglobin polymerization, vaso-occlusion, hemolysis |

| Common Symptoms | None | Pain crises, anemia, infection risk, organ damage |

Current CRISPR-Based Therapeutic Strategies for HBB Mutation Correction

The precise understanding of the genetic defect in SCD has enabled the development of targeted gene correction strategies using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Current approaches primarily focus on either directly correcting the pathogenic E6V point mutation or reactivating fetal hemoglobin (HbF) to compensate for the defective HbS. The direct gene correction strategy represents the most ideal curative approach as it addresses the fundamental genetic lesion while preserving physiologic regulation of gene expression [3].

Direct HBB Gene Correction

The direct correction approach utilizes high-fidelity Cas9 precomplexed with chemically modified guide RNAs to introduce a precise double-strand break near the E6V mutation in the HBB gene. This is followed by homology-directed repair (HDR) using a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (rAAV6) vector delivering a donor DNA template with the correct nucleotide sequence [3]. This method has demonstrated up to 60% HBB allelic correction in clinical-scale manufacturing of patient-derived CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) [3]. Preclinical studies show long-term engraftment of these corrected cells in immunodeficient mice with multi-lineage correction frequencies of approximately 20% in hematopoietic organs, sufficient to reverse the sickling phenotype [3]. Toxicology studies have demonstrated no evidence of abnormal hematopoiesis, genotoxicity, or tumorigenicity from the engrafted gene-corrected cells, supporting the safety profile of this approach [3].

Fetal Hemoglobin Reactivation

An alternative strategy involves reactivating fetal hemoglobin through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated disruption of repressive regulatory elements. This approach targets the BCL11A gene enhancer or the LRF repressor binding sites in the γ-globin gene promoters [4] [5]. BCL11A is a master transcriptional regulator that suppresses γ-globin expression during development, and its disruption leads to sustained HbF production in adult red blood cells [5]. Similarly, targeting LRF binding sites in the γ-globin promoters has shown potent HbF synthesis in erythroid progeny derived from edited HSPCs [4]. This strategy has proven clinically successful, with the FDA approval of exagamglogene autotemcel (exa-cel), which utilizes CRISPR technology to inactivate BCL11A, for the treatment of SCD [6] [5].

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR-Based Therapeutic Strategies for Sickle Cell Disease

| Parameter | Direct HBB Gene Correction | BCL11A Targeting (HbF Reactivation) | LRF Binding Site Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | HBB gene E6V mutation | BCL11A erythroid enhancer | γ-globin promoter LRF binding sites |

| Therapeutic Goal | Restore normal β-globin | Increase γ-globin (HbF) | Increase γ-globin (HbF) |

| CRISPR Mechanism | Homology-directed repair | Non-homologous end joining | Non-homologous end joining |

| Donor Template Required | Yes (rAAV6) | No | No |

| Editing Efficiency | Up to 60% allelic correction [3] | High rate of indels at target site [5] | High frequency of disruption [4] |

| HbF Levels | Physiological HbA production | Significant HbF increase (>20%) | Potent HbF synthesis [4] |

| Clinical Status | Preclinical (Phase I/II planned) [3] | FDA approved (exa-cel) [6] | Preclinical/Clinical trials |

Experimental Protocols for HBB Gene Correction in Hematopoietic Stem Cells

The development of CRISPR-based therapies for SCD requires robust experimental protocols that can be translated to clinical applications. The following section details key methodologies for HBB gene correction in patient-derived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

Isolation and Mobilization of CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem Cells

HSPCs are obtained from SCD patients via plerixafor mobilization rather than granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), which is contraindicated in SCD due to potential toxicity [3]. Plerixafor is a CXCR4 antagonist that induces rapid and reversible mobilization of CD34+ HSPCs into peripheral circulation [3]. CD34+ cells are then purified from leukapheresis products using immunomagnetic selection with clinical-grade CD34 MicroBeads and an AUTOMACS PRO system, achieving purities exceeding 90% [3] [7]. Cells are cultured in serum-free media supplemented with recombinant human cytokines (SCF, Fit3-L, TPO, IL-3) and small molecule enhancers (StemRegenin-1, UM171) to maintain stemness while promoting proliferation [3] [7].

CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery and HBB Gene Editing

The editing process utilizes ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes consisting of purified high-fidelity Cas9 protein complexed with synthetic, chemically modified single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting sequences near the E6V mutation [3] [4]. These RNP complexes are delivered to HSPCs via electroporation, providing efficient editing with reduced off-target effects compared to viral delivery methods. Following electroporation, cells are immediately transduced with rAAV6 donor vectors containing the homologous DNA template with the corrected HBB sequence and flanking homology arms of approximately 250 base pairs each [3]. The use of rAAV6 significantly enhances homology-directed repair efficiency in HSPCs. Edited cells are cultured for 48-72 hours before analysis of editing efficiency and transplantation.

Assessment of Editing Efficiency and Safety

Editing efficiency is quantified using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) with allele-specific probes to distinguish between corrected and uncorrected HBB alleles [3]. Next-generation sequencing provides comprehensive analysis of on-target editing rates and potential off-target effects. In vitro erythroid differentiation is performed to assess functional correction by measuring HbS polymerization and sickling propensity under deoxygenated conditions [3] [4]. Safety assessments include karyotyping, whole-genome sequencing, and translocation assays to detect chromosomal abnormalities, with particular focus on known genomic fragile sites [4].

Preclinical Engraftment and Toxicology Studies

The functional potential of gene-corrected HSPCs is evaluated using immunodeficient mouse models (e.g., NGS mice) [3]. Cells are administered via intravenous or intra-femoral injection following sublethal irradiation. Engraftment is monitored over 16-24 weeks using flow cytometry to quantify human CD45+ cell chimerism and multi-lineage differentiation potential (myeloid, lymphoid, erythroid) [3]. Secondary transplantation assays evaluate long-term hematopoietic stem cell activity. Bone marrow is analyzed post-engraftment to assess persistence of gene correction and HbA production. Comprehensive toxicology studies examine potential genotoxicity, tumorigenicity, and abnormal hematopoiesis [3].

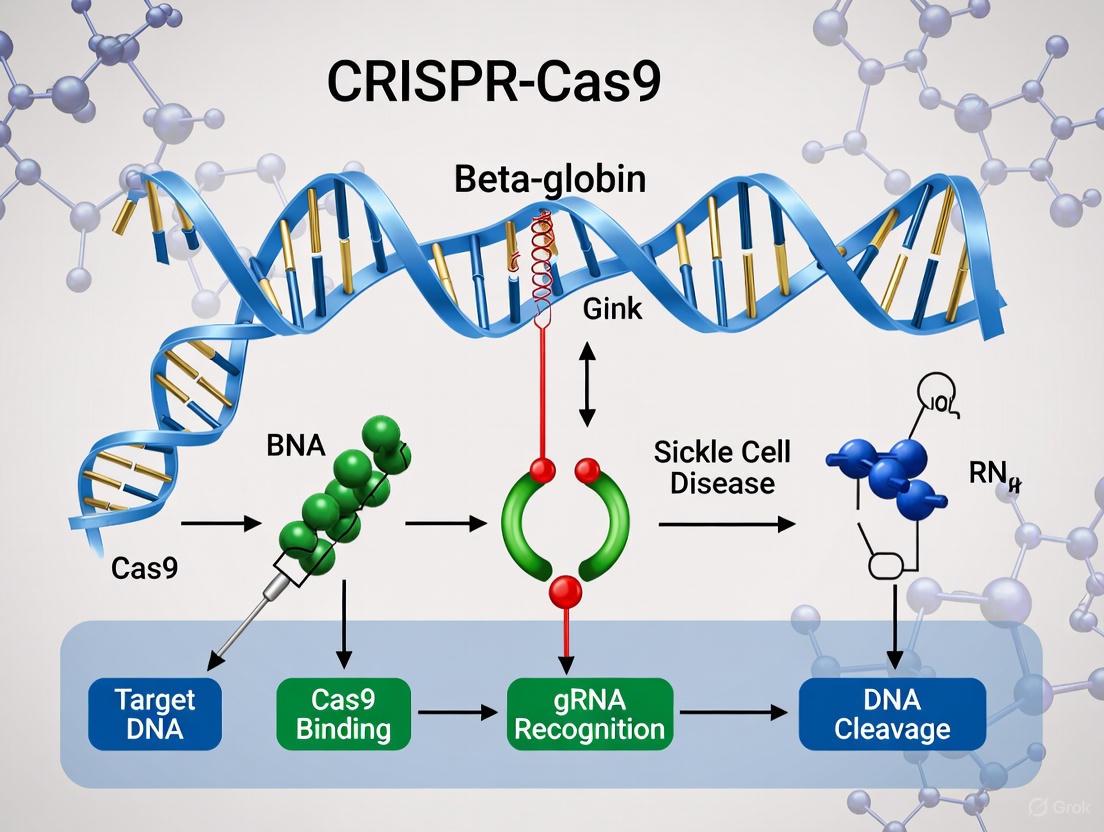

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for CRISPR-based HBB gene correction in sickle cell disease, showing key stages from hematopoietic stem cell collection to preclinical validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The implementation of CRISPR-based gene correction protocols requires specialized reagents and tools optimized for working with hematopoietic stem cells. The following table details essential research solutions for HBB gene editing studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HBB Gene Correction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| HSPC Mobilization | Plerixafor (Mozobil) | CXCR4 antagonist mobilizes CD34+ cells to peripheral blood for collection [3]. |

| Cell Separation | CD34 MicroBead Kit | Immunomagnetic selection of CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells [7]. |

| Cell Culture Media | StemSpan Serum-Free Medium | Base medium for HSPC culture, maintains stemness while supporting proliferation [7]. |

| Cytokine Cocktail | SCF, Fit3-L, TPO, IL-3 | Essential growth factors for HSPC survival, expansion, and maintenance of multipotency [7]. |

| Small Molecule Enhancers | StemRegenin-1 (SR1), UM171 | Potent agonists that enhance HSPC expansion and self-renewal ex vivo [3] [7]. |

| CRISPR Enzyme | High-fidelity Cas9 (HiFi Cas9) | Engineered Cas9 variant with reduced off-target effects while maintaining high on-target activity [3]. |

| Guide RNA | Chemically modified sgRNAs | Synthetic single-guide RNAs with chemical modifications to enhance stability and editing efficiency [3] [4]. |

| Donor Template Vector | rAAV6 with HBB Donor | Recombinant AAV serotype 6 efficiently delivers homologous donor template for HDR in HSPCs [3]. |

| Delivery Method | Electroporation System | Non-viral delivery method for introducing RNP complexes into HSPCs (e.g., Neon, Amaxa) [3]. |

| Editing Assessment | ddPCR Assays | Ultra-sensitive quantification of HBB allelic correction frequency using allele-specific probes [3]. |

| Safety Assessment | Next-Generation Sequencing | Comprehensive analysis of on-target editing, off-target effects, and chromosomal rearrangements [4]. |

Clinical Translation and Regulatory Landscape

The transition from preclinical research to clinical application of CRISPR-based therapies for SCD has achieved significant milestones. Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) became the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based medicine for SCD in late 2023, representing a landmark in the field [6] [8]. This therapy utilizes CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the BCL11A enhancer in patient-derived HSPCs, leading to sustained HbF production and inhibition of HbS polymerization [6]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that this approach can significantly reduce or eliminate vaso-occlusive crises in SCD patients [6].

Direct HBB gene correction strategies are advancing toward clinical trials, with foundational preclinical data supporting Investigational New Drug (IND) applications to the FDA [3]. Phase I/II trials will primarily evaluate safety, engraftment efficiency, and therapeutic efficacy of gene-corrected HSPCs. Current clinical-scale manufacturing protocols can process approximately 1-5×10^9 CD34+ cells with viability exceeding 80% post-editing [3].

The field is also exploring next-generation approaches including base editing and prime editing which offer potentially safer alternatives by minimizing DNA double-strand breaks [5]. Additionally, research continues into in vivo delivery systems that could eliminate the need for ex vivo manipulation of HSPCs, though this remains challenging for hematopoietic targets [6].

Figure 2: Logical pathway from genetic defect to clinical outcomes, showing how different CRISPR therapeutic strategies address the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease.

The successful clinical translation of CRISPR therapies requires addressing several challenges, including manufacturing scalability, cost reduction, and ensuring equitable access to these transformative treatments [6]. As of 2025, significant progress has been made in arranging reimbursement through state Medicaid programs and national health systems, though financial barriers remain substantial for these high-cost therapies [6]. The continued refinement of gene editing technologies promises to further enhance the safety, efficacy, and accessibility of curative approaches for sickle cell disease.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most prevalent monogenic disorders worldwide, affecting millions of people globally [9] [10]. This hereditary hemoglobinopathy arises from a specific single nucleotide transversion point mutation in the β-globin gene (HBB) located on chromosome 11, which leads to the substitution of the sixth amino acid in the β-globin chain from glutamic acid to valine [9] [10] [11]. This single substitution results in the production of abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS), which undergoes polymerization under deoxygenated conditions, fundamentally altering red blood cell (RBC) physiology and triggering a complex pathophysiological cascade culminating in the vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) that characterizes this debilitating disease [9] [11]. The understanding of this molecular pathway is particularly crucial in the current era of CRISPR-based gene editing approaches, which aim to correct the fundamental genetic defect underlying SCD.

The HbS Polymerization Cascade

The initial pathogenic event in SCD is the polymerization of deoxygenated HbS. The substitution of valine for glutamic acid establishes hydrophobic interactions between the valine of one HbS molecule and alanine, phenylalanine, and leucine residues of adjacent HbS molecules in the deoxygenated state [9]. This creates a hydrophobic patch that binds to the hydrophobic groove of a third HbS molecule, forming an HbS tetramer. The intermittent aggregation of these tetramers results in the formation of double-stranded polymer chains, which subsequently combine to form long helical fourteen-stranded insoluble fibers [9]. This polymerization process exhibits a characteristic delay time before the rapid phase of polymer formation, which is dependent on deoxy-HbS concentration and the transit time of RBCs through the microvasculature [12].

Table 1: Key Factors in HbS Polymerization

| Factor | Role in Polymerization | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Deoxygenation | Promotes hydrophobic interactions enabling polymer formation | Oxygen therapy; Hyperbaric oxygen [13] |

| HbS Concentration | Higher concentrations decrease delay time and accelerate polymerization | Hydration therapy; Hemodilution [12] |

| Intracellular HbF Levels | Inhibits HbS polymerization by disrupting polymer contacts | Hydroxyurea; Genetic modulation of BCL11A [9] [14] |

| 2,3-DPG Levels | Decreases oxygen affinity, promoting deoxygenation and polymerization | Modulating erythrocyte metabolism [10] |

| Temperature | Affects polymerization kinetics | Avoiding hypothermia; Temperature control [9] |

| pH | Acidosis promotes polymerization | Managing metabolic acidosis [10] |

The polymerization of HbS transforms normally discoid, flexible RBCs into rigid, sickle-shaped cells with reduced deformability and shorter lifespan (10-20 days compared to 120 days for normal RBCs) [9]. These morphological changes are reversible initially with reoxygenation, but repeated sickling cycles cause irreversible membrane damage, leading to permanently sickled cells that are highly fragile and prone to hemolysis [10].

Pathophysiology of Vaso-Occlusion: A Multicellular Cascade

Vaso-occlusion in SCD represents a multistep, multicellular process involving complex interactions between sickled erythrocytes, leukocytes, platelets, and the vascular endothelium, rather than simply being a consequence of rigid sickle cells obstructing blood flow [12] [11]. The historical evolution of our understanding of VOC is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Evolution of Scientific Understanding of VOC

| Year | Scientific Observation | Contribution to VOC Understanding |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | James Herrick's description of sickle-shaped RBCs | Original description of abnormal RBC morphology [12] |

| 1949 | Linus Pauling's demonstration of mutated hemoglobin | Identified SCD as a molecular disease of hemoglobin [12] |

| 1974 | Hofrichter and Eaton's "delay time" concept | Established kinetics of deoxy-HbS polymerization [12] |

| 1980 | Hebbel and Hoover's adhesion studies | Demonstrated increased propensity of SS-RBCs to adhere to endothelium [12] |

| 1989 | Kaul and Nagel's intravital studies | Showed SS reticulocytes initiate VOC by adhering to endothelium [12] |

| 2002 | Turhan and Frenette's leukocyte studies | Provided in vivo evidence for role of leukocytes in initiating VOC [12] |

| 2009 | Wallace and Linden's iNKT cell research | Identified role of iNKT cells in amplifying inflammation [12] |

The contemporary model of VOC pathogenesis involves several interconnected pathways:

Endothelial Activation and Adhesion

The vascular endothelium in SCD patients exists in a chronically activated state. Up to 50% of SCD patients experience endothelial dysfunction, primarily due to diminished nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability resulting from NO scavenging by cell-free plasma hemoglobin and L-arginine depletion by cell-free arginase released from hemolyzed RBCs [9]. This endothelial activation triggers increased expression of adhesion molecules including VCAM-1, ICAM-1, P-selectin, and E-selectin, which promote vascular occlusion and vasoconstriction [9] [12]. Activated platelets also contribute to this process through binding of platelet CD47 to endothelial thrombospondin, triggering exhibition of α2β3 on platelet surfaces that facilitates attachment to ICAM-4 on endothelial cells [9].

Hemolysis and Oxidative Stress

Intravascular hemolysis releases free hemoglobin and heme into the plasma, creating a pro-oxidant environment [10] [15]. Cell-free hemoglobin scavenges nitric oxide, while heme promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETosis) and activates inflammatory pathways through transcription factors such as BTB and CNC homologue (BACH) 1 and Spi-C [11]. Sickle erythrocytes exhibit increased NADPH oxidase activity and undergo HbS autoxidation at accelerated rates, generating excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [10] [15]. The antioxidant defense systems in SCD are compromised, with reduced levels of both enzymatic antioxidants (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) and non-enzymatic antioxidants (glutathione, vitamin E, vitamin C), establishing a state of chronic oxidative stress [10].

Inflammation and Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

SCD is characterized by a chronic inflammatory state with elevated baseline leukocyte counts and activated phenotypes of neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets [11]. Ischemia-reperfusion injury following microvascular occlusions promotes chronic inflammation through increased oxidant production and enhanced leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium [12] [11]. This inflammatory cascade is amplified by the activation of CD1d-restricted invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells, which are more numerous and hyperresponsive to hypoxia/reoxygenation in SCD [12]. These cells secrete IFN-γ and chemokines that recruit additional lymphocytes to sites of inflammation, worsening tissue damage [12].

Pathophysiology of Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Adhesion Assays

Early studies investigating VOC utilized in vitro adhesion assays to examine the adhesive interactions between sickle RBCs and endothelial cells. These experiments demonstrated that sickle RBCs, particularly low-density reticulocytes, exhibit increased adherence to vascular endothelium compared to normal RBCs [12]. Specific molecular interactions identified include α4β1 integrin on sickle RBCs binding directly to endothelial VCAM-1, and interactions between RBC LW (ICAM-4) and endothelial αvβ3 integrin [12]. These assays were instrumental in establishing the importance of RBC-endothelial adhesion in the initiation of VOC.

Animal Models of SCD

The development of transgenic murine models of SCD in the late 1990s represented a significant advancement in VOC research [12]. These models have enabled in vivo investigation of VOC pathophysiology using techniques such as intravital microscopy, which has visualized the preferential adhesion of sickle RBCs and leukocytes in postcapillary venules and the role of inflammatory stimuli in driving the vaso-occlusive cascade [12]. Studies in SCD mice have demonstrated diurnal variations in leukocyte recruitment, with higher densities of adherent leukocytes in venules at nighttime corresponding with more dramatic VOC phenotypes [12].

CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing Protocols

Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing have enabled precise correction of the SCD-causing E6V mutation in patient-derived hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The experimental workflow involves:

- HSC Collection: CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are collected from mobilized peripheral blood of SCD patients [16].

- Electroporation of RNP Complexes: Cells are electroporated with Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) consisting of Cas9 complexed with chemically modified single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) with 2'-O-methyl 3'phosphorothioate (MS) modifications at both termini to enhance stability and activity [16].

- rAAV6 Donor Delivery: Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (rAAV6) vectors containing homology arms flanking the HBB target site are used to deliver homologous repair templates [16].

- Enrichment of Corrected Cells: At day 4 post-electroporation, successfully targeted cells are enriched based on high GFP expression (when using GFP-containing donors) through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic bead selection, achieving populations with >90% targeted integration [16].

- Transplantation: Corrected HSCs are infused back into myeloablated recipients, where they engraft and reconstitute the hematopoietic system with RBCs capable of producing adult hemoglobin (HbA) [16].

This methodology has demonstrated efficient correction of the SCD mutation in multiple patient-derived HSC samples, with edited erythrocytes expressing normal β-globin mRNA and maintaining intact transcriptional regulation of edited HBB alleles [16].

CRISPR/Cas9 HSC Gene Editing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SCD Pathophysiology and Gene Editing Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Platforms | CRISPR/Cas9 RNPs, Base Editors (BEs), Prime Editors (PEs) | Precise correction of HBB E6V mutation; BCL11A targeting for HbF reactivation [14] [16] |

| Delivery Systems | rAAV6, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation | Efficient delivery of editing components to hematopoietic stem cells [14] [16] |

| Cell Culture Models | Patient-derived CD34+ HSPCs, Humanized SCD murine models | Preclinical testing of editing efficiency and safety; VOC pathophysiology studies [12] [16] |

| Adhesion Molecule Reagents | Anti-P-selectin aptamers, VCAM-1/ICAM-1 blocking antibodies | Investigating leukocyte-RBC-endothelial interactions in VOC [9] [12] |

| Oxidative Stress Assays | DCFDA, Lipid peroxidation kits, GSH/GSSG assays | Quantifying ROS production and antioxidant capacity in sickle erythrocytes [10] [15] |

| Analytical Tools | In-Out PCR, NGS off-target assays, HPLC for hemoglobin | Assessing targeted integration efficiency, safety profiles, and hemoglobin switching [16] |

Implications for CRISPR-Based Therapeutic Approaches

The detailed understanding of HbS polymerization and VOC pathophysiology has directly informed the development of CRISPR-based therapeutic strategies for SCD. Current approaches primarily focus on two strategic paradigms:

Direct Mutation Correction

The most straightforward approach involves precise correction of the E6V point mutation in the HBB gene using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair. This strategy utilizes Cas9 ribonucleoproteins combined with rAAV6-delivered homologous donor templates to convert the sickle allele back to the normal β-globin sequence [16]. This approach has demonstrated allelic modification frequencies of approximately 19% in multiple HSPC donors, with the potential to restore normal hemoglobin production and prevent HbS polymerization entirely [16]. The development of enrichment protocols using FACS or magnetic beads to purify populations with >85% targeted integration has addressed the challenge of achieving therapeutic levels of corrected cells in vivo [16].

BCL11A Targeting for HbF Reactivation

An alternative strategy involves targeting the BCL11A gene, a transcriptional repressor of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). Reduction of BCL11A expression prevents HbS polymerization by increasing HbF expression, which incorporates into hemoglobin tetramers and disrupts the hydrophobic interactions necessary for HbS polymer formation [9] [14]. This approach has been successfully implemented in the FDA-approved therapy exagamglogene autotemcel (exa-cel), which has demonstrated robust and sustained improvements in quality of life for patients with severe SCD, with clinically meaningful improvements in physical, social, functional, and emotional well-being observed as early as six months post-treatment [17].

The path from the single nucleotide mutation in the β-globin gene to the devastating clinical manifestations of vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell disease involves a complex, multistep pathophysiology centered on HbS polymerization. This process initiates a cascade of events including erythrocyte sickling, chronic hemolysis, oxidative stress, endothelial activation, and persistent inflammation that culminates in episodic microvascular occlusion. The detailed elucidation of these mechanisms has been instrumental in guiding the development of novel CRISPR-based gene therapies that directly target the underlying genetic defect. As these innovative therapies progress through clinical trials and into clinical practice, they offer the promise of durable, potentially curative treatments for this debilitating monogenic disorder, transforming the lives of patients affected by sickle cell disease worldwide.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) management has long relied on a triad of therapeutic approaches: the pharmacologic agent hydroxyurea, chronic red blood cell transfusions, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). While these interventions have improved patient survival and quality of life, they are characterized by significant limitations including variable efficacy, treatment-related toxicities, and accessibility challenges. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of these foundational treatments, framing their shortcomings as the imperative driving current research into targeted genetic corrections, notably CRISPR-based therapies. Structured data on efficacy, implementation protocols, and mechanistic pathways are presented to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a consolidated reference on the pre-gene therapy landscape of SCD management.

Sickle cell disease is a monogenic autosomal recessive disorder caused by a point mutation in the β-globin gene (HBB), substituting valine for glutamic acid at position 6. This results in the production of hemoglobin S (HbS), which polymerizes under deoxygenated conditions, leading to erythrocyte sickling, hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusion, and end-organ damage [18]. The clinical management of SCD has focused on mitigating these pathophysiological consequences. For decades, the therapeutic arsenal was confined to hydroxyurea, chronic transfusion regimens, and HSCT—each providing symptomatic relief or disease modification but falling short of a definitive, widely applicable cure. The limitations inherent in these conventional modalities have established a clear rationale for the development of therapies aimed directly at the underlying genetic defect.

Hydroxyurea: A Disease-Modifying Agent with Adherence Barriers

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Efficacy

Hydroxyurea, an oral, once-daily medication approved by the FDA in 1998, remains a first-line disease-modifying therapy. Its primary mechanism involves the cytotoxic inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase, leading to cellular stress that stimulates the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) [19]. Elevated HbF levels interfere with HbS polymerization, thereby reducing sickling of red blood cells. Clinically, this translates to fewer vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) and acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, along with decreased need for blood transfusions [20].

Real-world, long-term studies confirm its sustained benefits. A 2024 analysis of 2,147 pediatric patients with severe SCD genotypes (HbSS/HbSβ⁰) demonstrated that hydroxyurea use was associated with 0.36 fewer emergency department visits and 0.84 fewer hospital days per patient-year compared to those not on the treatment [20]. The efficacy, however, is tightly linked to adherence; improvements in hemoglobin concentration are predominantly observed in patients with laboratory markers indicating consistent intake [20].

Documented Limitations and Barriers

Despite its efficacy, hydroxyurea is underutilized, with adherence being a central challenge. Barriers can be categorized within the framework of intentional and unintentional nonadherence, as identified in a large 2022 study [19].

Table 1: Barriers to Hydroxyurea Adherence and Utilization

| Barrier Category | Specific Barriers | Affected Population |

|---|---|---|

| Unintentional Nonadherence | Forgetting to take medication, competing life demands, challenges with pharmacy refills | Common across all age groups [19] |

| Intentional Nonadherence | Worry about long-term side effects (e.g., cancer risk, fertility impacts), aversion to medications, belief that "tried and it did not work" | Particularly prevalent in young adults and adults [19] |

| Provider-Level Barriers | Lack of familiarity with prescribing guidelines, hesitation to prescribe for non-HbSS/HbSβ⁰ genotypes despite indications | Contributes to under-prescription [19] |

| Formulation & Systemic Barriers | Lack of widely available liquid formulations for children, medication costs | Impacts accessibility, especially for pediatric populations [19] |

The perception of hydroxyurea's origin as a chemotherapy agent continues to fuel concerns about cancer risk and teratogenicity, despite studies showing long-term safety [19]. Furthermore, adults aged 26 and older are the demographic least likely to be on hydroxyurea therapy, highlighting a critical gap in lifelong care [19].

Experimental and Clinical Assessment Protocols

Protocol for Monitoring Hydroxyurea Efficacy in Clinical Trials:

- Baseline Assessment: Complete blood count (CBC) with differential, HbF percentage (by HPLC), renal and hepatic function panels.

- Dosing & Titration: Initiate therapy at 15-20 mg/kg once daily. Titrate every 8 weeks to maximum tolerated dose (MTD), typically capped at 35 mg/kg, targeting absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 2.0 x 10⁹/L [19].

- Efficacy Endpoints:

- Primary: Annual rate of VOCs requiring medical attention.

- Secondary: Change in HbF percentage from baseline, annual number of hospitalizations and ED visits, incidence of ACS, transfusion requirements.

- Adherence Monitoring: Use of pharmacy refill data, patient diaries, and laboratory markers such as mean corpuscular volume (MCV), which typically increases with consistent therapy.

Red Blood Cell Transfusion: Burden of Iron and Alloimmunization

Transfusion Modalities and Indications

Red blood cell transfusion is a cornerstone intervention for both acute complications and chronic management of SCD. It aims to improve oxygen-carrying capacity and dilute the proportion of HbS-containing red cells to prevent vaso-occlusion [21]. The three primary methodologies are:

- Simple Transfusion: Most widely available; involves infusion of RBC units without removal of patient blood. Carries a high risk of iron overload and hyperviscosity if hemoglobin is raised significantly above baseline [21].

- Manual Exchange Transfusion: Involves alternating phlebotomy and transfusion. Provides better control of HbS% and reduces iron accumulation compared to simple transfusion but is time-consuming and requires significant staff training [21].

- Automated Red Cell Exchange (RCE): Uses apheresis technology to simultaneously remove patient blood and replace it with donor RBCs. Offers the best control of HbS%, minimal iron loading, and allows for longer intervals between procedures. However, it requires specialized equipment, robust venous access, and is less widely available [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Transfusion Modalities in SCD

| Parameter | Simple Transfusion | Manual Exchange | Automated RCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbS% Control | Poor | Intermediate | Best |

| Iron Accumulation | High | Intermediate | Low |

| Time Consumption | Low | High | Intermediate |

| Specialist Equipment | Not required | Not required | Required |

| Venous Access | Peripheral | Peripheral/Central | Often Central |

| Availability | Widespread | Widespread | Limited |

Evidence for transfusion is strongest for primary and secondary stroke prevention, supported by randomized controlled trials [21]. Outside neurological indications, practice is guided by observational data and expert opinion, leading to significant variation. For instance, the proportion of patients transfused for recurrent pain across different centers varies from 16% to 54% [21].

Limitations and Global Burden

The chronicity of transfusion therapy introduces significant complications.

- Iron Overload: Each unit of transfused blood contains 200-250 mg of iron. Without iron chelation therapy, this leads to accumulation, causing endocrine dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, and liver cirrhosis. Patients on simple transfusion typically require chelation after approximately one year of regular therapy [21].

- Alloimmunization: The development of antibodies against foreign RBC antigens occurs in approximately 20-30% of patients with SCD. This complicates cross-matching, delays future transfusions, and can cause severe hemolytic reactions. It is often attributed to ethnic differences in antigen prevalence between predominantly Caucasian blood donors and African-American patients [22].

- Infection Risk: Despite improved screening, transmission of infections such as hepatitis B and C remains a concern, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the blood supply may not meet WHO safety standards [22].

- Access and Logistics: In LMICs, access to safe, sustainable blood is a major barrier. Even in high-income nations, the burden of regular hospital visits for RCE or simple transfusion significantly impacts quality of life [22].

Standardized Transfusion Protocol

Protocol for Chronic Transfusion Therapy in SCD (Stroke Prevention):

- Pre-transfusion Testing: Extended RBC phenotyping (for C, E, K antigens) of the patient should be performed before the first transfusion to guide prophylactic antigen matching.

- Transfusion Goal: Maintain HbS% below a target threshold, typically 30-40%, to reduce stroke risk. The target hemoglobin should not exceed 10 g/dL to avoid hyperviscosity [21].

- Transfusion Interval: Typically every 3-4 weeks for simple transfusion; can be extended to 4-6 weeks for automated RCE.

- Adjunct Therapy:

- Iron Chelation: Initiate with deferasirox or deferoxamine when serum ferritin consistently exceeds 1000 ng/mL or after 1-2 years of chronic transfusion.

- Monitoring: Regularly monitor ferritin, liver function, and conduct echocardiography and T2* MRI for organ iron quantification.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Curative Yet High-Risk Option

Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is currently the only widely available curative therapy for SCD. It involves replacing the patient's hematopoietic system with that of a healthy donor. The first successful transplant was performed in 1984 [23].

Indications: HSCT is generally reserved for patients with severe SCD manifestations, such as stroke, recurrent ACS, refractory VOC, or progressive organ damage. The availability of a fully matched sibling donor is a key requirement for optimal outcomes [23]. The procedure is most successful in children, with studies showing improved survival in those under 10 years of age [23].

Technique: The process involves a myeloablative conditioning regimen (e.g., busulfan/cyclophosphamide) to ablate the patient's bone marrow, followed by infusion of donor stem cells. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis is critical. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimens have been developed to reduce toxicity, particularly in older patients [23].

Efficacy: A decade-long follow-up from the DREPAGREFFE-1 trial demonstrated superior outcomes for children with SCD who received HSCT compared to those on standard care (chronic transfusion/hydroxyurea). Transplant recipients showed significantly better physical, school, and social functioning, improved cognitive performance, and a halt in the progression of silent cerebral infarcts [24]. A decision analysis model assigned the highest quality-of-life utility score to HSCT (0.85) compared to hydroxyurea (0.80) and chronic transfusion (0.71) [25].

Significant Limitations and Risks

The curative potential of HSCT is counterbalanced by substantial risks that limit its application.

- Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD): This occurs when donor immune cells attack the recipient's tissues. It can be acute (affecting skin, liver, gut) or chronic (a multi-system disorder), and can be fatal or cause significant long-term morbidity [23].

- Infertility: Myeloablative conditioning regimens commonly cause permanent infertility, a significant concern for patients and families. Fertility preservation procedures are recommended prior to transplant [24].

- Graft Rejection/Failure: The risk of the graft not "taking" or the disease recurring exists, particularly if adequate immunosuppression is not achieved.

- Donor Availability: Only about 15-20% of patients with SCD have a fully matched sibling donor, severely restricting eligibility [23].

- Treatment-Related Mortality: The procedure carries an estimated 5-10% risk of mortality from infections, organ toxicity, or GVHD [23].

- Long-Term Effects: Patients remain at risk for long-term complications from the conditioning regimen and chronic GVHD, requiring lifelong specialist follow-up.

HSCT Clinical Trial Methodology

Protocol for Myeloablative Allogeneic HSCT from a Matched Sibling Donor:

- Candidate Selection: Patients <16 years with severe SCD (e.g., stroke, recurrent ACS) and an HLA-matched sibling donor.

- Pre-transplant Preparation (Conditioning): Administer myeloablative regimen (e.g., Busulfan 14-16 mg/kg IV, Cyclophosphamide 200 mg/kg). GVHD prophylaxis with a calcineurin inhibitor (e.g., cyclosporine) and methotrexate.

- Stem Cell Source: Infuse bone marrow or umbilical cord blood-derived hematopoietic stem cells from the donor.

- Post-Transplant Monitoring:

- Engraftment: Monitor for neutrophil and platelet recovery.

- Chimerism: Assess donor-derived hematopoietic cells. A myeloid chimerism of ≥20% is sufficient for a clinical cure [23].

- Complications: Monitor for and manage infections, GVHD, and organ toxicity.

- Primary Efficacy Endpoint: Event-free survival (freedom from SCD-related events and transplant-related mortality).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for SCD Therapy Development

The transition from conventional treatments to gene-based cures relies on a specific toolkit of research reagents and model systems. The following table details key materials essential for preclinical research in HBB-targeted gene correction.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HBB Correction Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) | The target cell population for ex vivo gene editing; capable of reconstituting the entire hematopoietic system. | Sourced from mobilized peripheral blood, bone marrow, or umbilical cord blood of healthy donors or SCD patients for autologous therapy [18]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System (e.g., SpCas9) | Creates a precise double-strand break in the DNA at a targeted genomic locus to enable gene correction. | Used with a guide RNA (gRNA) targeting the HBB gene mutation site for knock-in correction or targeting the BCL11A erythroid enhancer for HbF induction [26]. |

| gRNA for HBB or BCL11A | Guides the Cas9 nuclease to the specific DNA sequence for cleavage. | HBB-gRNA directs correction of the Glu6Val mutation; BCL11A-gRNA disrupts the HbF repressor [26]. |

| AAV6 Donor Template | Serves as a viral vector to deliver the homologous donor DNA template for precise HDR-mediated correction. | Used to provide a correct HBB sequence for repairing the SCD mutation in CD34+ HSPCs after a CRISPR-induced cut [18]. |

| Base Editors / Prime Editors | Advanced genome editing tools that directly convert one base to another without causing a double-strand break, offering a safer alternative. | Used to convert the diseased HbS (GTG) codon into a non-pathogenic variant like HbG-Makassar (GCG) in human HSPCs [26]. |

| X-VIVO 15 or STEMSPAN Media | Serum-free cell culture media optimized for the expansion and maintenance of human HSPCs during ex vivo manipulation. | Used to culture CD34+ cells during the gene editing process [18]. |

| Cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3-L) | Recombinant growth factors that promote HSPC survival and proliferation during ex vivo culture. | Added to culture media to enhance cell viability and maintain stemness throughout the editing and transplantation workflow [18]. |

| NSG (NOD-scid-gamma) Mice | An immunodeficient mouse model that allows for the engraftment of human hematopoietic cells, enabling in vivo assessment of edited HSCs. | Used to transplant gene-edited human CD34+ cells to evaluate long-term engraftment, multi-lineage differentiation, and functional correction of the sickle phenotype [18]. |

The historical landscape of SCD treatment, defined by hydroxyurea, transfusions, and HSCT, is marked by a trade-off between efficacy and significant limitations. Hydroxyurea's potential is hampered by adherence barriers and perceptions of risk. Transfusions, while life-saving, introduce a cascade of complications like iron overload and alloimmunization, and their efficacy is highly dependent on the modality and consistent access. HSCT, though curative, is restricted by donor availability and associated with profound risks like GVHD and infertility.

These collective shortcomings underscore the clear and pressing need for therapies that address the root genetic cause of SCD without incurring the burdens of chronic care or the severe risks of allogeneic transplantation. The limitations of these conventional therapies form the foundational rationale for the development of autologous, targeted genetic interventions, such as CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene correction, which aim to provide a durable, widespread, and safer curative solution.

β-hemoglobinopathies, primarily sickle cell disease (SCD) and β-thalassemia, are among the most common monogenic disorders worldwide, affecting millions and causing significant morbidity and mortality [27]. These conditions stem from mutations in the β-globin gene (HBB), which disrupt the structure or production of adult hemoglobin (HbA), leading to dysfunctional red blood cells [14] [28]. For SCD, a single nucleotide substitution (HBB: c.20A>T; p.Glu7Val) results in sickle hemoglobin (HbS) that polymerizes under deoxygenation, causing red blood cells to sickle and leading to vaso-occlusion, hemolysis, and end-organ damage [18]. In β-thalassemia, over 200 different HBB mutations can cause either absent (β⁰) or reduced (β⁺) β-globin synthesis, creating an imbalance in globin chain ratios, ineffective erythropoiesis, and chronic anemia [14] [27].

Current management strategies, including blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy, address symptoms but not the underlying genetic cause [14]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) can be curative but is limited by donor availability and graft-versus-host disease risks [28]. The advent of CRISPR-based genome editing technologies has ushered in a new therapeutic paradigm focused on precise genetic correction to restore normal hemoglobin function [14] [28]. This whitepaper delineates the therapeutic goals and technical methodologies for genetic correction strategies within the broader context of CRISPR research for β-globin mutation correction.

Therapeutic Goals and Strategic Approaches

The primary therapeutic goal for genetic correction of β-hemoglobinopathies is to achieve durable production of functional non-pathogenic hemoglobin within erythrocytes, sufficient to ameliorate or eliminate disease pathophysiology. This overarching goal can be broken down into several key objectives and strategic approaches.

Table 1: Core Therapeutic Goals for Genetic Correction of β-Hemoglobinopathies

| Therapeutic Goal | Molecular/Physiological Outcome | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Eliminate HbS Polymerization | Reduce proportion of HbS tetramers below critical gelling threshold (<5-10%) [18] | Prevention of vaso-occlusive crises, hemolysis, and end-organ damage |

| Restore Hemoglobin Tetramer Stability | Ensure sufficient β-like globin chains to pair with α-globin chains, preventing α-globin precipitation [27] | Correction of anemia, reduction of ineffective erythropoiesis |

| Achieve Therapeutically Relevant Hemoglobin Levels | Attain total hemoglobin >9-10 g/dL or fetal hemoglobin (HbF) >30% in majority of circulating erythrocytes [27] | Transfusion independence, normalized quality of life [17] |

| Ensure Clonal Stability & Long-Term Engraftment | Maintain gene-corrected hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in bone marrow niche with multi-lineage differentiation potential [3] | Sustained, lifelong curative effect |

Three principal CRISPR-based strategic pathways have been developed to achieve these goals, each with distinct molecular mechanisms.

- Direct Mutation Correction: This strategy aims to precisely correct the specific pathogenic point mutation in the endogenous HBB gene. For SCD, this involves converting the single A>T nucleotide mutation back to the wild-type sequence, thereby restoring the production of normal adult hemoglobin (HbA) [3] [18]. This approach preserves the native regulatory control of the HBB locus.

- Fetal Hemoglobin (HbF) Reactivation: This indirect approach does not target the HBB gene itself. Instead, it disrupts repressors of the fetal γ-globin genes, such as BCL11A, or their binding sites in the globin locus [14] [28] [29]. This re-activates the production of HbF (α₂γ₂), which does not sickle and can effectively substitute for the defective adult hemoglobin, ameliorating the disease [27].

- Functional Gene Addition: This strategy uses lentiviral vectors to introduce a functional copy of the HBB gene (or an anti-sickling variant) into the HSPC genome, ensuring production of non-pathogenic hemoglobin [27]. This is not a gene editing approach per se but a gene therapy often discussed alongside editing strategies.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and decision points between these core strategic pathways.

Quantitative Efficacy Benchmarks and Clinical Outcomes

The success of genetic correction strategies is quantified against specific biochemical and hematological benchmarks. Achieving these thresholds is strongly correlated with positive clinical outcomes, including transfusion independence in β-thalassemia and freedom from vaso-occlusive crises in SCD [17].

Table 2: Key Efficacy Benchmarks for Genetic Correction Strategies

| Parameter | Therapeutic Threshold | Reported Clinical Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| HbF Reactivation (for SCD) | >30% HbF-containing erythrocytes (F-cells) [27] | Exa-cel therapy: Elimination of VOCs in 96.7% of SCD patients at 24 months [18] [17] |

| Donor Cell Chimerism | ≥20% donor myeloid chimerism in bone marrow [18] | Associated with reversal of sickle phenotype post-allogeneic HSCT |

| HBB Allelic Correction (Ex Vivo) | Up to 60% allelic correction achieved in clinical-scale manufacturing [3] | ~20% gene correction frequency post-engraftment in murine models [3] |

| Transfusion Independence (for TDT) | Total hemoglobin sustained >9 g/dL without transfusions [17] | Exa-cel therapy: 93.5% of TDT patients achieved transfusion independence for ≥12 months [17] |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes | Scores exceeding Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) [17] | Exa-cel: Clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life, social, emotional, and sleep impacts [17] |

The clinical translation of these strategies has been highly successful. For the HbF reactivation strategy via BCL11A disruption, the approved therapy exagamglogene autotemcel (exa-cel, Casgevy) has demonstrated robust and sustained clinical benefits. As of a 2025 business update, approximately 115 patients had undergone cell collection for this treatment, with 29 patients having already received infusions [30]. Real-world application, as in the case of a 33-year-old with beta thalassemia major, demonstrates the therapeutic journey from lifelong monthly transfusions and iron chelation to the potential for a definitive cure [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for HBB Gene Correction

The following section provides a detailed methodology for an ex vivo CRISPR-based HBB gene correction protocol in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), as derived from foundational preclinical studies [3]. This protocol is representative of the processes used to develop clinically relevant genetic medicines.

The experimental workflow for ex vivo gene correction is complex and multi-staged, requiring precise execution at each step to ensure the yield of a therapeutically viable product. The entire process, from cell collection to infusion, can span several months.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: HSPC Mobilization and Collection

- Mobilization: Administer plerixafor (Mozobil), a CXCR4 antagonist, to mobilize CD34+ HSPCs from the bone marrow niche into peripheral blood. Plerixafor is preferred over G-CSF for SCD patients due to the risk of severe toxicity with G-CSF [3].

- Leukapheresis: Collect mobilized HSPCs via apheresis. Target cell dose should meet clinical-scale manufacturing requirements for a full human dose [3] [30].

Step 2: Cell Processing and Culture

- Isolation: Isulate CD34+ cells from the leukapheresis product using clinical-grade magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS).

- Culture: Resuspend and culture CD34+ cells in serum-free medium supplemented with cytokines (e.g., SCF, TPO, FLT3-L) and the small molecule UM171, an agonist that has been shown to improve the protocol by supporting the maintenance and expansion of primitive hematopoietic stem cells during the ex vivo culture period [3].

Step 3: CRISPR Genome Editing

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Formation: Pre-complex a high-fidelity Cas9 protein with a chemically modified, single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the specific genomic locus. Chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl-3'phosphorothiate) on the sgRNA enhance stability and editing efficiency [3] [28].

- Donor Template Preparation: Prepare a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (rAAV6) vector containing the homologous donor DNA template for the HBB gene. The donor template carries the intended correction (e.g., the wild-type sequence for SCD) flanked by homology arms.

- Co-Delivery: Deliver the Cas9 RNP complexes via electroporation into the cultured CD34+ HSPCs. Immediately following electroporation, transduce the cells with the rAAV6 donor template. This combination has been shown to achieve high frequencies of homology-directed repair (HDR) in long-term engrafting HSCs [3].

Step 4: Patient Conditioning

- Myeloablative Regimen: Administer a myeloablative conditioning regimen, typically with busulfan, to the patient. This is a critical step to create "space" in the bone marrow niche for the engraftment and expansion of the newly infused gene-corrected HSPCs [29].

Step 5: Product Infusion

- Final Formulation: The gene-corrected cell product (e.g., Drug Product-gcHBB-SCD) is washed, formulated in infusion medium, and released via quality control testing.

- Administration: Infuse the final cell product intravenously into the patient [3] [29].

Step 6: Engraftment and Monitoring

- Engraftment Period: Monitor the patient closely in the weeks following infusion for evidence of neutrophil and platelet engraftment, typically occurring within 2-4 weeks.

- Long-Term Follow-Up: Conduct weekly checkups for approximately six months to track blood counts and ensure the edited stem cells are producing healthy levels of all blood lineages. The definitive measure of success is transfusion independence for transfusion-dependent thalassemia or freedom from vaso-occlusive crises for SCD [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The execution of the aforementioned protocol relies on a suite of critical research reagents and materials. The following table details key components, their functions, and considerations for their use in developing genetic correction therapies for hemoglobinopathies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HBB Gene Correction Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Plerixafor (Mozobil) | CXCR4 antagonist mobilizes HSPCs from bone marrow to peripheral blood for collection [3]. | Preferred over G-CSF for SCD patient mobilization due to safety profile [3]. |

| CD34 MicroBead Kit | Immunomagnetic selection and isolation of CD34+ HSPCs from heterogeneous leukapheresis product [3]. | Critical for obtaining a target cell population with >90% purity for editing [3]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Engineered CRISPR-associated nuclease with reduced off-target activity [3]. | Essential for enhancing the safety profile of the therapeutic edit. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Single-guide RNA directs Cas9 to the specific target genomic locus (e.g., BCL11A erythroid enhancer or HBB locus) [3] [28]. | 2'-O-methyl-3'phosphorothiate modifications increase stability and editing efficiency [28]. |

| rAAV6 Serotype Vector | Delivery vehicle for the homologous donor DNA template to facilitate HDR-mediated gene correction [3]. | Demonstrates high efficiency of transduction in human HSPCs [3] [18]. |

| Electroporation System | Device for delivering Cas9 RNP complexes directly into the cytoplasm/nucleus of target HSPCs. | Enables transient, high-efficiency editing with low toxicity compared to viral delivery of editing components [28]. |

| UM171 Molecule | A small molecule agonist used in culture media to promote the maintenance and expansion of primitive hematopoietic stem cells ex vivo [3]. | Protocol optimization with UM171 can lead to higher in vivo retention of gene-corrected alleles [3]. |

| Lymphodepleting Agents (e.g., Busulfan) | Myeloablative chemotherapeutic agent used for patient conditioning to create bone marrow niche space [29]. | Critical for enabling successful engraftment of the infused gene-corrected HSPCs. |

The field of genetic correction for β-hemoglobinopathies has progressed from conceptual validation to clinical reality, as evidenced by the approval of CRISPR-based therapies like Casgevy [30]. The therapeutic goals are clearly defined: to restore normal hemoglobin function through direct mutation correction, fetal hemoglobin reactivation, or functional gene addition. Quantitative benchmarks, such as achieving HbF levels >30% or stable engraftment with ≥20% corrected cells, provide clear targets for therapeutic development.

Robust and detailed experimental protocols, leveraging reagents like plerixafor-mobilized CD34+ cells, high-fidelity Cas9 RNP, and rAAV6 donor templates, have enabled the transition from bench to bedside [3]. These foundational protocols continue to be refined, with next-generation research focusing on in vivo delivery of editing components to bypass the complex and costly ex vivo manufacturing process, and the development of targeted conditioning agents to reduce the toxicity of current regimens [30]. As the field advances, the ongoing challenge will be to broaden global access to these transformative therapies, particularly in regions with the highest prevalence of SCD and β-thalassemia [27].

CRISPR-Cas9 is an adaptive immune system found in prokaryotic organisms that has been repurposed for precise genome editing in eukaryotic cells [31]. The system consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-stranded breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA), which directs Cas9 to specific genomic locations [31]. This technology has revolutionized genetic engineering, offering unprecedented precision in modifying DNA sequences. For therapeutic applications in monogenic disorders such as sickle cell disease (SCD), CRISPR-Cas9 enables researchers to target and correct the underlying genetic mutations responsible for pathogenesis [18] [26]. The fundamental mechanism involves a complex interplay between the gRNA's targeting capability and the Cas9 nuclease's DNA cleavage activity, which together facilitate precise genetic modifications through cellular repair processes.

Core Mechanism: gRNA Design and Cas9 Nuclease Function

Guide RNA (gRNA) Design Principles

The guide RNA is a synthetic fusion molecule that combines the functions of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [31]. This ~100 nucleotide RNA molecule contains a 20-nucleotide spacer sequence at its 5' end that is complementary to the target DNA site, and a scaffold sequence at its 3' end that facilitates binding to the Cas9 nuclease. Effective gRNA design requires careful selection of the spacer sequence to ensure specificity and efficiency. The target site must be adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) with the sequence 5'-NGG-3' for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 [31]. The PAM sequence is essential for Cas9 recognition but is not part of the gRNA targeting sequence. gRNAs are typically designed to target sites as close as possible to the pathogenic mutation to maximize correction efficiency while minimizing off-target effects. For sickle cell disease research, gRNAs can be designed to target either the mutated β-globin gene (HBB) itself or regulatory genes such as BCL11A that control fetal hemoglobin expression [18] [26].

Cas9 Nuclease Mechanism

The Cas9 nuclease is a multi-domain enzyme that creates double-stranded breaks in DNA through its two distinct nuclease domains: HNH and RuvC [31]. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA spacer sequence, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand. Upon gRNA binding to the target DNA sequence, Cas9 undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease activity, resulting in a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site. This break then triggers the cell's innate DNA repair mechanisms, primarily non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) [26]. NHEJ is an error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, while HDR uses a donor DNA template to enable precise genetic corrections—the preferred pathway for therapeutic correction of the sickle cell mutation [18].

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and DNA Repair Pathways. The gRNA:Cas9 complex binds target DNA adjacent to a PAM sequence, creating double-strand breaks repaired via NHEJ or HDR pathways.

Quantitative Parameters for gRNA Selection

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimal gRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| gRNA Length | 20 nucleotides | Balances specificity and efficiency |

| GC Content | 40-60% | Prevents secondary structures; improves stability |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' | Essential for Cas9 recognition and binding |

| Off-Target Score | >90 (prediction tools) | Minimizes unintended genomic edits |

| On-Target Score | >50 (prediction tools) | Maximizes editing efficiency at intended target |

Therapeutic Application in Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell disease is caused by an A>T point mutation at codon 6 of the β-globin gene (HBB: c.20A>T), resulting in the substitution of valine for glutamic acid (p.Glu7Val) and the production of pathological hemoglobin S (HbS) [18]. This single nucleotide polymorphism leads to hemoglobin polymerization under deoxygenated conditions, causing red blood cells to assume a sickled shape, chronic hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusive crises, and multi-organ damage [32]. CRISPR-Cas9 therapy offers two primary strategic approaches for treating SCD: direct correction of the HBB mutation or indirect therapeutic approaches through manipulation of hemoglobin switching regulators.

Direct Correction Strategy

The direct correction approach involves designing gRNAs that target sequences immediately adjacent to the sickle cell mutation in the HBB gene, enabling precise correction through HDR using a donor DNA template containing the wild-type sequence [18]. This strategy requires the co-delivery of Cas9, gRNA, and a donor template into hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). The donor template typically contains the correct nucleotide (A instead of T) along with homologous arms ranging from 400-800 bp to facilitate efficient HDR. This method achieves permanent genetic correction at the endogenous HBB locus, restoring normal β-globin expression and function. Research has demonstrated successful correction of the sickle mutation in human HSPCs using this approach, with corrected cells demonstrating reduced sickling and improved survival [18]. However, the efficiency of HDR remains a challenge, as it competes with the more prevalent NHEJ pathway, which can introduce unintended mutations at the target site.

Indirect Therapeutic Approaches

Indirect approaches target regulatory genes rather than the mutated HBB gene itself. The most advanced strategy involves disrupting the BCL11A gene, which encodes a transcriptional repressor of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) [26]. Naturally occurring mutations in the BCL11A enhancer are associated with hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin and ameliorated SCD symptoms. CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to disrupt the BCL11A gene or its enhancer in HSPCs, thereby reducing BCL11A expression and allowing for persistent HbF production in adult red blood cells. HbF contains gamma-globin chains that do not polymerize with HbS and effectively interfere with HbS polymerization, preventing sickling of red blood cells [26]. This approach has led to the development of Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based therapy for SCD, which has demonstrated clinical efficacy in multiple patients [26].

Figure 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Therapeutic Strategies for Sickle Cell Disease. Two main approaches either correct the HBB mutation directly or disrupt BCL11A to induce fetal hemoglobin production.

Quantitative Therapeutic Thresholds

Table 2: Therapeutic Efficacy Parameters for SCD Gene Editing

| Parameter | Therapeutic Threshold | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Efficiency | >20% | Minimum for phenotypic correction |

| Donor Myeloid Chimerism | ≥20% | Correlates with 100% donor RBCs in peripheral blood |

| HbF Levels | >20% | Sufficient to inhibit HbS polymerization |

| Vector Copy Number (VCN) | <5 | Safety threshold for lentiviral approaches |

| Engraftment Efficiency | >80% | For sustained therapeutic effect |

Experimental Workflow for SCD Gene Correction

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Collection and Preparation

The therapeutic workflow begins with the collection of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from the patient. CD34+ cells can be isolated from bone marrow harvest or through mobilization into peripheral blood using plerixafor, a CXCR4 antagonist [32]. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is typically avoided in SCD patients due to the risk of vaso-occlusive crises. The collected CD34+ cells are then cultured in cytokine-rich media (SCF, TPO, FLT3-L) to maintain stemness while promoting cell cycle progression, which is essential for efficient CRISPR editing as HDR primarily occurs in cycling cells [32].

CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery and Electroporation

For clinical applications, CRISPR-Cas9 components are typically delivered to HSPCs via electroporation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [18]. These complexes consist of purified Cas9 protein pre-assembled with synthetic gRNA, which enables rapid genome editing while minimizing off-target effects associated with prolonged Cas9 expression. The RNP delivery method results in rapid clearance of CRISPR components, reducing immunogenicity and potential off-target activity. For HDR-based approaches, a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or adeno-associated virus (AAV) donor template is co-electroporated with the RNP complex. Optimization of electroporation parameters is critical for maintaining high cell viability while achieving efficient editing.

Transplantation and Engraftment

Following CRISPR editing, cells are infused back into the patient after myeloablative conditioning with busulfan to create niche space in the bone marrow [32]. Busulfan conditioning is essential for efficient engraftment of the modified HSPCs. Patients require close monitoring for engraftment signs, typically evidenced by neutrophil and platelet count recovery within 2-4 weeks post-transplantation. The establishment of ≥20% donor myeloid chimerism has been shown to correlate with 100% donor-derived red blood cells in peripheral blood due to the selective survival advantage of corrected RBCs over sickle RBCs [32].

Figure 3: Experimental Workflow for SCD Gene Therapy. Key steps from HSPC collection to transplantation and therapeutic outcome assessment.

Research Reagent Solutions for SCD Gene Editing

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Based Sickle Cell Disease Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | SpCas9, Cas12a (Cpf1), MAD7 | DNA cleavage with varying PAM requirements |

| gRNA Design Tools | ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits), CRISPick | Design and analysis of gRNA efficiency and specificity |

| Delivery Methods | Electroporation systems, AAV6 serotype | Introduction of CRISPR components into HSPCs |

| HDR Donor Templates | ssODNs, AAV donor vectors, dsDNA templates | Precise correction of sickle mutation |

| Cell Culture Media | StemSpan, cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3-L) | Maintenance and expansion of HSPCs |

| Analysis Tools | Sanger sequencing, NGS, ICE analysis, MAGeCK | Assessment of editing efficiency and specificity |

Analytical Methods for CRISPR Editing Assessment

Editing Efficiency Quantification

The Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) tool enables robust analysis of CRISPR editing efficiency from Sanger sequencing data, providing NGS-quality analysis at significantly reduced cost [33]. ICE analyzes sequencing chromatograms from edited samples by deconvoluting the complex traces resulting from heterogeneous editing outcomes. The algorithm calculates indel percentages, knockout scores (proportion of cells with frameshift or 21+ bp indels), and knock-in scores (proportion of sequences with desired knock-in edit) [33]. For HDR-based approaches, digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) is employed to precisely quantify correction rates at the target locus.

Off-Target Analysis

Comprehensive off-target analysis is essential for therapeutic applications. In silico prediction tools identify potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity to the gRNA spacer. Empirically, genome-wide methods such as GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq can detect actual off-target cleavage events [18]. For clinical applications, targeted deep sequencing of predicted off-target sites is performed to ensure the safety of the edited cell product.

Functional Validation

Functional assessment of edited cells includes in vitro differentiation of HSPCs into erythroid lineages followed by analysis of hemoglobin expression via HPLC and measurement of sickling propensity under low-oxygen conditions [18]. For preclinical validation, edited HSPCs are transplanted into immunodeficient mice to assess long-term engraftment potential and lineage differentiation in vivo.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system represents a transformative technology for the treatment of sickle cell disease through precise genome editing of hematopoietic stem cells. The dual strategies of direct HBB mutation correction and BCL11A-targeted fetal hemoglobin induction offer promising therapeutic avenues, with the latter already achieving clinical validation and regulatory approval. Continued optimization of gRNA design, delivery methods, and editing efficiency will further enhance the safety and efficacy of these approaches. As the field advances, CRISPR-based therapies hold the potential to provide durable, one-time treatments for sickle cell disease and other monogenic disorders, moving from innovative research concepts to established clinical modalities.

CRISPR Editing Strategies for Beta-Globin Correction: Technical Approaches and Workflows

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a monogenic autosomal recessive disorder and one of the most prevalent severe monogenic diseases worldwide, affecting approximately 500,000 neonates globally each year [18]. The molecular pathogenesis of SCD stems from a single-nucleotide transversion in the β-globin gene (HBB), where an adenine-to-thymine substitution results in the replacement of glutamic acid with valine at codon 6 (HBB: c.20A>T; p.Glu7Val) [18]. This specific point mutation leads to the production of sickle hemoglobin (HbS), which polymerizes under deoxygenated conditions, distorting red blood cells into a characteristic sickle shape [18]. The abnormal erythrocytes trigger downstream pathological events including vaso-occlusion, hemolytic anemia, ischemic damage to organs and tissues, and significantly reduced lifespan—averaging 42 years for females and 38 years for males in the United States [18].

Direct correction of the SCD point mutation via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategies, moving beyond symptomatic management toward a curative genetic intervention. Unlike approaches that introduce exogenous genes or modulate related pathways, HDR-based correction aims to precisely revert the pathogenic mutation to the wild-type sequence at the endogenous HBB locus, thereby restoring normal β-globin production and hemoglobin function while maintaining native regulatory control [27]. This technical guide examines the current methodologies, challenges, and applications of HDR-mediated HBB gene correction within the broader context of CRISPR research for SCD.

Fundamental Principles of HDR-Mediated Gene Correction

Homology-Directed Repair is a precise DNA repair pathway that becomes active primarily in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, utilizing homologous DNA sequences as templates to faithfully repair double-strand breaks (DSBs) [34]. In the context of gene editing for SCD, this natural cellular mechanism is co-opted by introducing a site-specific DSB near the pathogenic mutation using programmable nucleases alongside a donor template containing the correct HBB sequence with homologous arms.

The competitive relationship between HDR and error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) presents a significant challenge for therapeutic applications. NHEJ frequently dominates DSB repair in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), particularly in quiescent populations, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the HBB gene rather than correcting it [34] [35]. This competition underscores the importance of optimizing experimental conditions to favor HDR outcomes, including cell cycle synchronization, delivery methods, and the design of editing reagents.

The fundamental workflow for HDR-based HBB correction involves several critical steps: (1) isolation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from a patient; (2) introduction of sequence-specific nucleases to create a DSB near the E6V mutation; (3) co-delivery of a donor template with the correct HBB sequence; (4) ex vivo culture to allow for repair and expansion; and (5) reinfusion of corrected cells following conditioning [18] [27]. Successful engraftment of these corrected HSCs can then theoretically restore normal erythropoiesis, with even partial chimerism demonstrating therapeutic potential—studies suggest that as little as 20% donor myeloid chimerism may be sufficient to reverse the sickle phenotype [18].

Donor Template Design and Delivery Strategies

Donor Template Variants and Design Considerations

The design of the donor template is a critical determinant of HDR efficiency and safety. Currently, two primary template types dominate HBB correction strategies: viral-based templates (particularly recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 6, rAAV6) and synthetic single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) [34] [35].

Table 1: Comparison of Donor Template Platforms for HBB Gene Correction

| Template Type | Size Capacity | HDR Efficiency (In Vitro) | Engraftment Persistence (In Vivo) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rAAV6 | ~4.7 kb | High (34% reported with optimized cassettes) [36] | Reduced long-term persistence in some studies [34] | High transduction efficiency in HSPCs, large cargo capacity | Potential immune responses, production complexity |

| ssODN | <200 bp | Moderate | Superior long-term persistence in engrafting HSCs [34] | Simple design, cost-effective, minimal immunogenicity | Limited homology arm length, lower HDR efficiency for large edits |

| Adenovirus 5/35 | ~36 kb | Variable | Limited data available | Very large cargo capacity | Increased cytotoxicity, complex production |

| IDLV | ~8 kb | Moderate | Limited data available | Non-integrating, extended template persistence | Lower HDR efficiency compared to AAV6 |