CRISPR-Cas9 in Genetic Disorder Therapy: From Molecular Tools to Clinical Breakthroughs

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology in treating genetic disorders.

CRISPR-Cas9 in Genetic Disorder Therapy: From Molecular Tools to Clinical Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology in treating genetic disorders. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas systems, details methodological advances and specific therapeutic applications for monogenic diseases, analyzes critical challenges such as off-target effects and delivery, and evaluates clinical validation through recent trials and comparative efficacy. The synthesis of current evidence highlights the paradigm shift from symptom management to curative potential, while also addressing the ongoing hurdles and future directions necessary for the widespread clinical translation of these innovative therapies.

The CRISPR-Cas9 Revolution: Understanding the Core Technology and Its Therapeutic Potential

From Bacterial Immunity to a Genome Engineering Revolution

The journey of CRISPR-Cas systems from a curious genetic sequence in bacteria to a revolutionary genome-editing toolkit represents one of the most significant advancements in modern biotechnology. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) were first identified in 1987 in Escherichia coli as a set of unusual repetitive DNA sequences downstream of the iap gene [1]. For years, these sequences remained a molecular mystery until bioinformatics analyses revealed they were present in approximately 40% of bacteria and 90% of archaea [2]. The critical breakthrough came when researchers recognized that the spacer sequences between CRISPR repeats matched viral and plasmid DNA, suggesting a role in adaptive immunity [2] [1].

The functional validation of this hypothesis came in 2007 when Barrangou and colleagues demonstrated that Streptococcus thermophilus could acquire new spacers from invading viruses and that these spacers conferred resistance to subsequent viral attacks [2] [1]. This discovery confirmed CRISPR-Cas as a bacterial adaptive immune system. The system functions in three main stages: (1) adaptation, where new spacers are acquired from invading DNA; (2) expression, where CRISPR RNA (crRNA) is transcribed and processed; and (3) interference, where Cas proteins use crRNAs to identify and cleave matching foreign DNA sequences [1].

The transformation of this bacterial defense mechanism into a programmable gene-editing tool began with key discoveries elucidating the molecular components. Researchers found that in the Type II CRISPR system, the Cas9 protein is the sole enzyme responsible for DNA cleavage [2]. Critical work by the Charpentier group revealed the mechanism of crRNA biogenesis, showing that a trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) was essential for mature crRNA formation [2]. The pivotal moment came in 2012 when Doudna and Charpentier engineered the dual RNA guide (crRNA:tracrRNA) into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and demonstrated that Cas9 could be programmed to cleave any DNA sequence complementary to the sgRNA [3]. This simplification created the versatile CRISPR-Cas9 system that has revolutionized genetic research and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system operates as a precise molecular scissor guided by RNA-DNA recognition. The system consists of two fundamental components: the Cas9 endonuclease and the guide RNA (gRNA) [3]. The gRNA is a synthetic fusion of two natural RNA molecules - the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) that specifies the target sequence, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) that serves as a scaffold for Cas9 binding [4] [3].

The mechanism of action begins with gRNA-Cas9 complex formation. The gRNA directs Cas9 to the target DNA sequence through Watson-Crick base pairing between its 20-nucleotide guide sequence and the complementary DNA strand [3] [1]. Target recognition requires the presence of a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence immediately adjacent to the target region [5] [1]. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [5].

Once the gRNA binds its complementary sequence and Cas9 recognizes the PAM, the enzyme undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains [3]. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand, resulting in a precise double-strand break (DSB) 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [4] [3].

Cellular repair of these programmed DSBs occurs primarily through two pathways [5] [4]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, enabling gene knockout.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a homologous DNA template to repair the break, allowing for specific gene corrections or insertions.

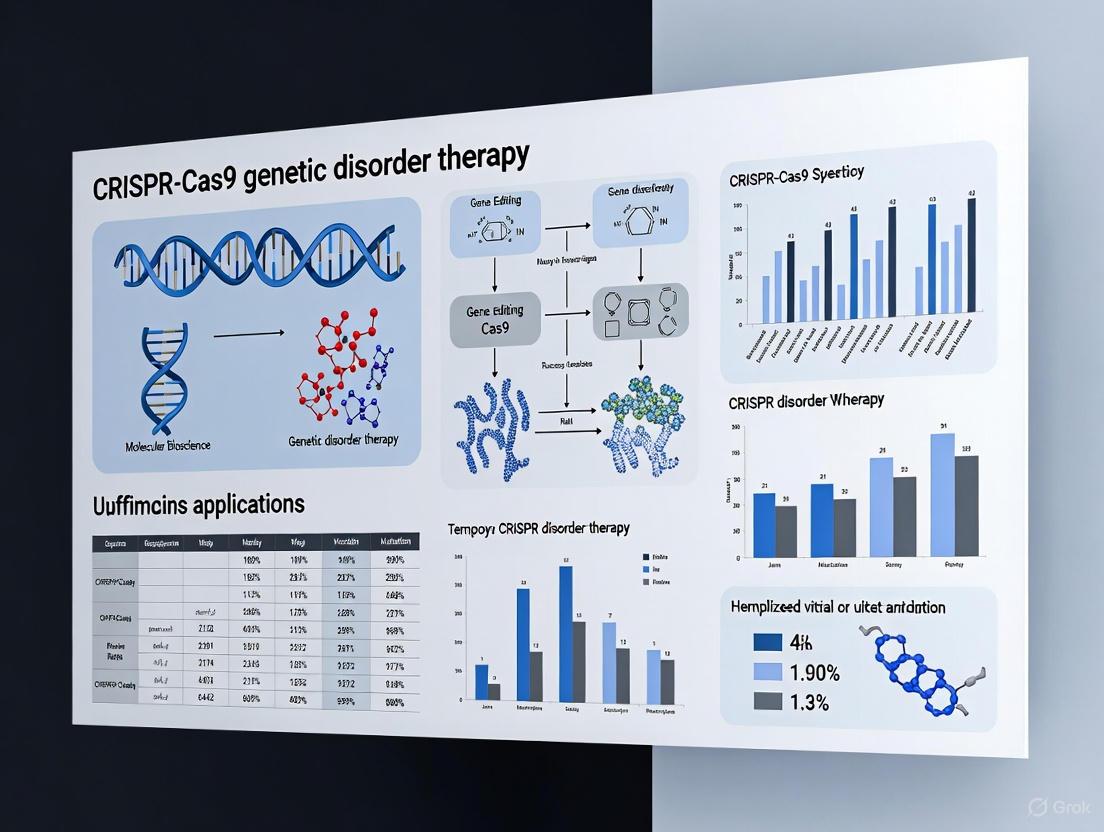

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and DNA Repair Pathways. This workflow illustrates the sequential process from gRNA-Cas9 complex formation through target recognition, DNA cleavage, and cellular repair pathways.

Advanced CRISPR Toolkit: Beyond Basic Gene Editing

The fundamental CRISPR-Cas9 system has evolved into a diverse toolkit with capabilities extending far beyond simple gene disruption. These advanced derivatives have significantly expanded therapeutic applications:

Catalytically Impaired Cas9 Variants: The creation of dead Cas9 (dCas9), through point mutations in both nuclease domains, eliminates cleavage activity while retaining DNA-binding capability [6] [2]. dCas9 serves as a programmable DNA-targeting platform that can be fused to various effector domains for [6]:

- Gene regulation (CRISPRi/CRISPRa) when fused to transcriptional repressors or activators

- Epigenetic editing when fused to DNA methyltransferases or histone modifiers

- Chromatin imaging when fused to fluorescent proteins

Base Editing: Developed to overcome the limitations of HDR efficiency, base editors enable direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base pair to another without requiring DSBs [5] [4]. These systems fuse dCas9 or Cas9 nickase to deaminase enzymes:

- Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs): Convert C•G to T•A base pairs

- Adenine Base Editors (ABEs): Convert A•T to G•C base pairs

Prime Editing: This more recent innovation uses a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) and a Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site [4]. Prime editors can achieve all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring DSBs [4].

CRISPR-Based Diagnostics and Imaging: CRISPR systems have been adapted for diagnostic applications (e.g., SHERLOCK, DETECTR) and live-cell chromatin imaging using dCas9 fused to fluorescent proteins [6] [2].

Therapeutic Applications in Genetic Disorders

CRISPR-Cas9 technology has demonstrated remarkable potential for treating genetic disorders through diverse therapeutic approaches, with both ex vivo and in vivo applications showing promising results in clinical trials.

Table 1: Selected Clinical Trials of CRISPR-Cas9 Therapeutics for Genetic Disorders

| Disease | Target Gene | Intervention | Clinical Phase | Delivery Method | NCT Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease | BCL11A | CTX001 | Phase II/III | Electroporation (ex vivo) | NCT03745287 |

| Transfusion-Dependent Beta-Thalassemia | BCL11A | CTX001 | Phase II/III | Electroporation (ex vivo) | NCT03655678 |

| Leber Congenital Amaurosis | CEP290 | EDIT-101 | Phase I/II | AAV5 (in vivo) | NCT03872479 |

| Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis | TTR | NTLA-2001 | Phase I | Lipid Nanoparticles (in vivo) | NCT04601051 |

| Hereditary Angioedema | KLKB1 | NTLA-2002 | Phase I/II | Lipid Nanoparticles (in vivo) | NCT05120830 |

Ex Vivo Therapeutic Approaches

Ex vivo genome editing involves modifying patient cells outside the body before transplanting them back into the patient. This approach has shown remarkable success for hematological disorders:

Sickle Cell Disease and Beta-Thalassemia: The therapies CTX001 target the BCL11A gene, a repressor of fetal hemoglobin [5]. By disrupting the BCL11A enhancer in autologous hematopoietic stem cells, these treatments reactivate fetal hemoglobin production, which compensates for the defective adult hemoglobin in sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia [5] [7]. Clinical trials have reported successful transfusion independence in thalassemia patients and resolution of vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell patients [5].

Cancer Immunotherapies: CRISPR-edited CAR-T cells have been developed for cancer treatment. Early-phase clinical trials have used CRISPR for multiple edits in T cells, including disrupting endogenous T-cell receptors and immune checkpoint genes to enhance antitumor activity [8].

In Vivo Therapeutic Approaches

In vivo delivery of CRISPR therapeutics involves directly administering the editing components to patients:

Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis: NTLA-2001 uses lipid nanoparticles to deliver CRISPR components to the liver, targeting the TTR gene to reduce production of misfolded transthyretin protein [5]. Early clinical results demonstrated dose-dependent protein reduction up to 96% [5].

Leber Congenital Amaurosis: EDIT-101 uses an AAV5 vector to deliver CRISPR components to retinal cells, aiming to correct a mutation in the CEP290 gene that causes this inherited form of blindness [5].

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Preclinical studies have successfully used CRISPR to restore dystrophin expression by excising mutation-containing exons in animal models [9].

Experimental Protocols for Genetic Disorder Research

Protocol: Ex Vivo Genome Editing of Hematopoietic Stem Cells for Hemoglobinopathies

This protocol outlines the methodology for editing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to reactivate fetal hemoglobin for treating sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, based on successful clinical approaches [5] [7].

Materials and Reagents:

- Human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells

- Cas9 protein or mRNA

- sgRNA targeting the BCL11A erythroid enhancer

- Electroporation buffer

- Stem cell culture media (StemSpan with cytokines)

- Homology-directed repair template (if using HDR)

Procedure:

- HSC Mobilization and Collection: Mobilize CD34+ cells from the patient using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and collect via apheresis.

- Cell Preparation: Isulate CD34+ cells using immunomagnetic selection and culture overnight in StemSpan medium supplemented with cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3-L).

- Ribonucleoprotein Complex Formation: Incubate Cas9 protein with sgRNA targeting the BCL11A enhancer (molar ratio 1:2) for 10-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Electroporation: Wash cells and resuspend in electroporation buffer. Electroporate 1-2×10^6 cells/mL with RNP complex using appropriate settings (e.g., 1500V, 10ms pulse width).

- Recovery and Expansion: Immediately transfer electroporated cells to pre-warmed culture medium and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48-72 hours.

- Quality Control: Assess editing efficiency by T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing. Verify cell viability and phenotype.

- Transplantation: Infuse edited cells back into the patient after myeloablative conditioning.

Validation Methods:

- Measure indel frequency at the BCL11A enhancer

- Quantify fetal hemoglobin expression by FACS and HPLC

- Assess erythroid differentiation in vitro

- Verify absence of off-target edits at predicted sites

Protocol: In Vivo Genome Editing for Liver Disorders

This protocol describes the approach for in vivo genome editing using lipid nanoparticle delivery, as demonstrated in clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis [5] [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- LNP-formulated Cas9 mRNA

- LNP-formulated sgRNA targeting the TTR gene

- Saline for dilution

- Animal model of disease (e.g., transgenic mice expressing human TTR)

Procedure:

- LNP Formulation: Prepare LNPs containing Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA using microfluidic mixing technology with ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid.

- Dose Preparation: Dilute LNP suspension in sterile saline to appropriate concentration for administration.

- Administration: Administer via intravenous injection at doses typically ranging from 0.1-1.0 mg/kg mRNA.

- Monitoring: Observe animals for potential adverse effects and monitor serum TTR levels over time.

- Tissue Collection: At endpoint, collect liver tissue and blood for analysis.

Validation Methods:

- Measure serum TTR reduction by ELISA

- Quantify editing efficiency in liver tissue by NGS

- Assess potential off-target effects by whole-genome sequencing

- Evaluate liver histology and function

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Applications

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, Staphylococcus aureus Cas9, Campylobacter jejuni Cas9 | DNA cleavage with varying PAM requirements and molecular sizes |

| Guide RNA Systems | Synthetic sgRNA, crRNA:tracrRNA duplex, U6-driven expression vectors | Target sequence specification and Cas nuclease recruitment |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV vectors (AAV2, AAV5, AAV9), Lentiviral vectors, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation systems | Intracellular delivery of CRISPR components |

| Editing Modalities | Wildtype Cas9, Cas9 nickase (D10A), dead Cas9 (dCas9), Base editors (CBE, ABE), Prime editors | Enable different types of genetic modifications (knockout, base conversion, precise editing) |

| Detection & Validation | T7 Endonuclease I assay, Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE), Next-generation sequencing, Western blot, Flow cytometry | Assessment of editing efficiency and functional outcomes |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the remarkable progress in CRISPR-based therapies, several challenges remain to be addressed for broader clinical application:

Delivery Efficiency: Efficient and specific in vivo delivery remains a significant hurdle. Current viral vectors (AAV) have packaging size constraints and can elicit immune responses, while non-viral methods (LNPs) need improved tissue targeting [5] [3]. Ongoing research focuses on developing novel delivery systems, including engineered AAV capsids and synthetic nanoparticles with enhanced tropism for specific tissues [4].

Off-Target Effects: Unintended editing at off-target sites with sequence similarity to the gRNA remains a safety concern [9] [10]. Strategies to mitigate this include:

- Using high-fidelity Cas9 variants with reduced off-target activity

- Careful gRNA design with computational prediction of potential off-target sites

- RNP delivery instead of plasmid DNA, which reduces exposure time

- Comprehensive off-target assessment using methods like CIRCLE-seq or GUIDE-seq

Immune Responses: Pre-existing immunity to bacterial Cas proteins in human populations and immune responses to delivery vectors may impact safety and efficacy [9] [3]. Approaches to address this include screening patients for pre-existing immunity, using Cas orthologs from less common bacteria, or employing transient delivery methods.

Ethical Considerations: The ability to perform germline editing raises significant ethical questions that require careful public discourse and regulatory frameworks [10] [7]. Most current clinical applications focus on somatic cell editing, which affects only the treated individual.

The future of CRISPR therapeutics lies in developing more precise, efficient, and safe systems. Next-generation editors with enhanced specificity, reduced immunogenicity, and broader targeting scope will expand therapeutic possibilities. As delivery technologies advance and long-term safety data accumulate, CRISPR-based therapies are poised to transform treatment for countless genetic disorders.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, derived from an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria, has revolutionized genome editing by providing researchers with a precise and programmable method for modifying DNA sequences [11] [12]. This technology centers on the ability of the Cas9 nuclease to create targeted double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in DNA when guided by a short RNA molecule [13]. For therapeutic research, this molecular complex offers unprecedented potential for correcting genetic mutations underlying hereditary disorders. The system's core components—the Cas9 enzyme and guide RNA (gRNA)—function together as a highly specific DNA-targeting complex that can be directed to virtually any genomic locus, making it particularly valuable for developing treatments for monogenic diseases such as sickle cell anemia and β-thalassemia [14] [12]. Understanding the precise mechanism by which these components achieve DNA cleavage is fundamental to advancing CRISPR-Cas9 applications in genetic therapy research.

Structural Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

The Cas9 Nuclease Architecture

The Cas9 protein possesses a bilobed architecture consisting of two primary lobes: the recognition (REC) lobe and the nuclease (NUC) lobe [11]. The REC lobe, comprised primarily of REC1, REC2, and REC3 domains, is responsible for binding the guide RNA and facilitating interactions with the target DNA [15]. The NUC lobe contains the catalytic core of the enzyme with two nuclease domains—HNH and RuvC—along with the PAM-interacting domain essential for initiating DNA binding [11] [16].

- HNH Domain: Cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA (target strand) [11] [12]

- RuvC Domain: Cleaves the non-complementary DNA strand (non-target strand) [11] [12]

- PAM-Interacting Domain: Recognizes the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site that serves as a binding signal [11] [13]

In eukaryotic cells, Cas9 requires nuclear localization signals (NLS) for transport into the nucleus where it can access genomic DNA [11]. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy have revealed that Cas9 undergoes significant conformational rearrangements upon binding to both guide RNA and target DNA, enabling its activation for DNA cleavage [15] [16].

Guide RNA: The Targeting Molecule

The guide RNA consists of two fundamental components that can be combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for experimental applications [11] [17]:

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA): A ~20 nucleotide sequence complementary to the target DNA that provides targeting specificity [11] [18]

- tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA): A structural RNA that binds to Cas9 and facilitates complex formation [11]

The sgRNA forms a stable complex with Cas9, creating a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex capable of scanning the genome for complementary DNA sequences [13] [18]. The 5' end of the sgRNA contains the spacer sequence that determines DNA targeting through Watson-Crick base pairing, while the 3' end forms a scaffold that interacts with the Cas9 protein [17] [19].

Table 1: Key Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

| Component | Structure | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Bilobed protein (REC and NUC lobes) | RNA-guided DNA endonuclease |

| HNH Domain | β-βα metal finger fold | Cleaves target DNA strand complementary to guide RNA |

| RuvC Domain | RNase H-like fold | Cleaves non-target DNA strand |

| PAM-Interacting Domain | Arg-rich motif | Recognizes NGG protospacer adjacent motif |

| crRNA | ~20 nt RNA sequence | Provides target specificity through DNA complementarity |

| tracrRNA | Structured RNA scaffold | Binds Cas9 and stabilizes crRNA |

Molecular Mechanism of Targeted DNA Cleavage

DNA Target Recognition and R-loop Formation

The process of targeted DNA cleavage begins with PAM recognition, where the Cas9-sgRNA complex scans the genome for the protospacer adjacent motif (typically 5'-NGG-3' for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) [11] [13]. The PAM sequence serves as an essential binding signal, and its recognition triggers local DNA melting, allowing the seed sequence (nucleotides 8-10 at the 3' end of the guide sequence) to initiate pairing with the target DNA [13] [15].

Following seed pairing, the R-loop expands as the sgRNA continues to hybridize with the target DNA in a 3' to 5' direction [13] [15]. Cryo-EM studies have revealed that this process occurs in distinct steps, with the REC2 and REC3 domains facilitating the accommodation of the emerging RNA-DNA heteroduplex [15]. The directional hybridization ensures that mismatches between the guide RNA and target DNA, particularly in the PAM-proximal seed region, are efficiently discriminated against, providing a critical checkpoint for target specificity [15] [16].

Conformational Activation and DNA Cleavage

Upon complete R-loop formation, Cas9 undergoes significant conformational changes that activate its nuclease domains [15] [16]. Structural studies have identified multiple conformational states of the HNH domain, with the active state positioning the catalytic residue H840 close to the scissile phosphate of the target DNA strand [16]. This conformational activation represents a critical checkpoint that monitors the integrity of the guide-target duplex before permitting DNA cleavage [15].

The cleavage event itself results in a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [13] [12]. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the opposite strand, with both domains functioning as metal-dependent nucleases [11] [16]. The resulting DSB then engages the cellular DNA repair machinery, enabling genome editing through either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or precise homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways [11] [18].

DNA Repair Pathways and Genome Editing Outcomes

Following Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage, cellular repair mechanisms determine the final genomic outcome. The two primary repair pathways—non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR)—offer distinct applications for genetic therapy research [11] [12].

Table 2: DNA Repair Pathways Following Cas9 Cleavage

| Repair Pathway | Mechanism | Editing Outcome | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Error-prone ligation of broken ends without template | Small insertions or deletions (indels); gene disruption | Gene knockouts; disruption of pathogenic genes |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | High-fidelity repair using homologous donor template | Precise gene correction or insertion | Correction of point mutations; gene insertion therapy |

The NHEJ pathway is active throughout the cell cycle and represents the dominant repair mechanism in most mammalian cells [11] [18]. While efficient, this pathway often results in small random insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site, which can disrupt gene function by introducing frameshift mutations or premature stop codons [13] [12]. For therapeutic applications, NHEJ is particularly valuable for disrupting pathogenic genes, such as those involved in genetic disorders driven by gain-of-function mutations [14].

In contrast, the HDR pathway utilizes a donor DNA template with homology to the sequences flanking the break site to enable precise genome editing [11] [18]. Although HDR occurs at lower frequencies than NHEJ and is restricted to specific cell cycle phases, it offers the potential for correcting disease-causing mutations with single-nucleotide precision [12]. Therapeutic strategies employing HDR typically provide an engineered donor template along with the CRISPR-Cas9 components, enabling the replacement of defective genomic sequences with functional ones [14].

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Delivery

The delivery of preassembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes represents a highly efficient and specific approach for genome editing applications [11]. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for RNP-based editing:

sgRNA Design: Design sgRNA with optimal GC content (40-60%) and minimal off-target potential using bioinformatics tools [11] [17]. Ensure the target site is adjacent to a PAM (5'-NGG-3') and lacks significant homology to other genomic regions [11].

RNP Complex Assembly:

- Combine recombinant Cas9 protein (10-20 µM) with synthetic sgRNA at a 1:1.2-1.5 molar ratio in nuclease-free buffer

- Incubate at 25°C for 10-15 minutes to allow complex formation [11]

Cell Delivery:

Post-transfection Processing:

- Allow cells to recover for 24-72 hours in complete medium

- Assess editing efficiency using T7E1 assay, tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE), or next-generation sequencing [11]

This RNP delivery method offers advantages including reduced off-target effects due to transient Cas9 activity, and minimal risk of genomic integration compared to plasmid-based approaches [11].

Validation and Analysis of Editing Outcomes

Comprehensive validation of CRISPR-Cas9 editing is essential for therapeutic applications:

Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-editing and extract genomic DNA using standard protocols

Editing Efficiency Analysis:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target region using flanking primers (amplicon size: 300-500 bp)

- Next-generation Sequencing: Sequence amplicons to precisely quantify indels and verify HDR events

- Alternative Methods: T7E1 assay or SURVEYOR assay for initial screening of editing efficiency [11]

Off-target Assessment:

- Use computational prediction tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) to identify potential off-target sites

- Perform targeted sequencing of top predicted off-target loci with sequence similarity to the sgRNA

- Consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9(1.1) to minimize off-target editing [11] [13]

Advanced Cas9 Engineering for Enhanced Specificity

Wild-type Cas9 can tolerate mismatches between the guide RNA and target DNA, potentially leading to off-target effects that pose challenges for therapeutic applications [11] [13]. Several engineered Cas9 variants have been developed to address this limitation:

Table 3: Engineered Cas9 Variants for Improved Specificity

| Cas9 Variant | Engineering Strategy | Key Features | Therapeutic Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-fidelity Cas9 (SpCas9-HF1) | Structure-guided mutagenesis to reduce non-specific DNA contacts | ~500-fold reduction in off-target editing while maintaining on-target efficiency | Enhanced safety profile for clinical applications |

| Enhanced Specificity Cas9 (eSpCas9) | Weakened interactions with non-target DNA strand | Reduced off-target effects without compromising on-target activity | Improved target specificity for precision medicine |

| Hyper-accurate Cas9 (HypaCas9) | Enhanced proofreading capability through allosteric regulation | Improved discrimination against mismatched targets | Reduced risk of unintended genomic alterations |

| Cas9 Nickase (nCas9) | Inactivation of either HNH or RuvC domain (D10A or H840A mutation) | Creates single-strand breaks instead of DSBs; requires paired gRNAs for DSB formation | Significantly reduced off-target effects when used as paired nickases |

Additional engineering efforts have focused on altering PAM specificity to expand the targeting range of Cas9. Variants such as xCas9 and SpCas9-NG recognize alternative PAM sequences (NG, GAA, and GAT for xCas9), thereby increasing the number of targetable genomic sites for therapeutic applications [13].

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | Wild-type SpCas9, High-fidelity variants (SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) | General genome editing, applications requiring high specificity | Choose based on specificity requirements and delivery method |

| Guide RNA Formats | Synthetic sgRNA, crRNA:tracrRNA duplex, plasmid-encoded sgRNA | Flexible experimental designs; synthetic RNAs offer immediate activity | Synthetic RNAs reduce off-target risks; plasmid formats enable stable expression |

| Delivery Vehicles | Electroporation systems, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), viral vectors (AAV, lentivirus) | Cell type-specific delivery optimization | LNPs ideal for primary cells; viral vectors for hard-to-transfect cells |

| Detection & Validation | T7E1 assay, next-generation sequencing, digital PCR, flow cytometry | Assessment of editing efficiency and specificity | Multiplexed approaches recommended for comprehensive validation |

| HDR Donor Templates | Single-stranded DNA oligos, double-stranded DNA plasmids, AAV vectors | Precision genome editing, gene correction | Optimize design with long homology arms (≥800 bp) for efficient HDR |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Outlook

The mechanistic understanding of Cas9 DNA cleavage has enabled remarkable advances in therapeutic development for genetic disorders. Recent clinical trials demonstrate the potential of CRISPR-Cas9 for treating monogenic diseases:

Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia: The FDA-approved therapy Casgevy utilizes ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 editing of hematopoietic stem cells to reactivate fetal hemoglobin production, effectively compensating for the defective adult hemoglobin in these disorders [14].

Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR): Intellia Therapeutics has demonstrated successful in vivo genome editing using LNP-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 to reduce levels of disease-causing transthyretin protein in the liver, with clinical trials showing ~90% reduction in serum TTR levels that remains durable over time [14].

Rare Genetic Disorders: The landmark case of a personalized CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency established a regulatory precedent for rapidly developed bespoke therapies for ultra-rare genetic conditions [14]. This approach, developed and delivered in just six months, illustrates the potential for CRISPR-based interventions for previously untreatable disorders.

Emerging delivery technologies, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), have enabled efficient in vivo delivery of CRISPR components to target tissues, opening new avenues for therapeutic development [14]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence tools like CRISPR-GPT is accelerating experimental design and optimization, potentially reducing development timelines for CRISPR-based therapies [20].

As the field advances, ongoing challenges include optimizing delivery efficiency, minimizing off-target effects, and ensuring equitable access to these transformative therapies. Continued research into the fundamental mechanisms of Cas9 function will further refine this powerful technology, ultimately expanding its potential for treating a broad spectrum of genetic disorders.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas systems has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development by providing unprecedented ability to manipulate genomes. While the initial CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as programmable "genetic scissors" that create double-strand breaks (DSBs), recent innovations have dramatically expanded the CRISPR toolkit beyond this foundational mechanism [21] [22]. Base editors and prime editors represent the next generation of precision genome editing tools that overcome fundamental limitations of conventional CRISPR-Cas9, particularly for therapeutic applications where precision and safety are paramount [23].

These advanced editors are particularly valuable in the context of genetic disorder therapy research, where many diseases are caused by specific point mutations that require precise correction rather than gene disruption [21]. Over 75,000 pathogenic genetic variants have been identified in humans, and previously developed genome editing methods could only correct a minority of these variants [24]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of Cas9 nucleases, base editors, and prime editors, with specific experimental protocols and resource guidance to enable researchers to select and implement the optimal tool for their genetic correction objectives.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Capabilities

Core Mechanisms of Action

CRISPR-Cas9 Nucleases utilize a complex of Cas9 enzyme and guide RNA (gRNA) to create targeted double-strand breaks in DNA [21]. The system relies on recognition of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site [21]. Once DSBs are generated, cellular repair mechanisms are harnessed to achieve the desired genetic change: error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) typically results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, while homology-directed repair (HDR) can incorporate donor DNA templates for precise changes [21] [23]. However, HDR efficiency is generally low, especially in non-dividing cells, and the process frequently produces a mixture of outcomes including undesirable indels [21] [23].

Base Editors represent the first major evolution beyond standard CRISPR nucleases, enabling direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without creating DSBs [21] [22]. These fusion proteins combine a catalytically impaired Cas protein (nCas9) with a deaminase enzyme [23]. Two primary classes have been developed: Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) convert cytosine to thymine (C→T) through a cytidine deaminase, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert adenine to guanine (A→G) using an engineered adenosine deaminase [21] [23]. Base editors operate within a defined "editing window" where all susceptible bases are modified, which can lead to bystander edits when multiple target bases are present in this window [24].

Prime Editors constitute the most versatile precision editing system, capable of installing all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring DSBs or donor DNA templates [21] [24]. The system employs a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit, along with a fusion protein consisting of Cas9 nickase fused to an engineered reverse transcriptase [25] [24]. After nicking the target DNA, the pegRNA's primer binding site anneals to the nicked strand, and the reverse transcriptase synthesizes new DNA containing the edited sequence using the pegRNA's template region [24] [26].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of CRISPR Editing Technologies

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Base Editors | Prime Editors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Precision | Low (mixed outcomes) | Moderate (editing window) | High (specific change) |

| Efficiency for Point Mutations | Typically <10% (HDR) [24] | High (typically 50-80%) [22] | Variable (1-50%) [24] |

| Indel Formation | High (∼50-90% of events) [23] | Low (<1-10%) [23] | Low (typically 1-10%) [24] |

| Theoretical Targeting Scope | ∼37.5% of pathogenic SNPs [21] | ∼25% of pathogenic SNPs [21] | ∼89% of pathogenic SNPs [21] |

| Primary Editing Byproducts | Indels, translocations [23] | Bystander edits within window [24] | Low complexity outcomes [24] |

| Typical Edit Size | Large deletions/insertions | Single base changes | Up to ∼20 bp edits [25] |

Table 2: Molecular Capabilities of CRISPR Editing Technologies

| Edit Type | CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Base Editors | Prime Editors |

|---|---|---|---|

| C→T | Possible via HDR | Yes (CBE) [21] | Yes [24] |

| A→G | Possible via HDR | Yes (ABE) [21] | Yes [24] |

| Transversions | Possible via HDR | No | Yes [24] |

| Small Insertions | Possible via HDR | No | Yes (∼20 bp max) [25] |

| Small Deletions | Yes (via NHEJ) | No | Yes [24] |

| Multiple Simultaneous Edits | Challenging | No | Possible [24] |

| Gene Disruption | Excellent | Possible | Less efficient [25] |

Therapeutic Applications and Experimental Evidence

Application-Specific Technology Selection

The choice of CRISPR technology depends heavily on the specific genetic correction objective. For disease modeling where gene disruption is desired, conventional CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease remains highly effective [23]. For therapeutic correction of point mutations, base editors offer high efficiency when the desired change is a transition mutation (C→T, G→A, A→G, or T→C) and the target base is optimally positioned within the editing window [22]. Prime editors provide the broadest capabilities for precise edits, particularly when the required change involves transversions, small insertions or deletions, or when bystander editing must be avoided [24].

Sickle Cell Disease Case Study: Research demonstrates how both base editing and prime editing can effectively address the same genetic disorder through different approaches. A base editing strategy successfully converted the sickle cell disease mutation (A→T in β-globin) to a nonpathogenic variant known as hemoglobin G Makassar using a custom adenine base editor, achieving 68% editing efficiency in mouse models with stable correction over 16 weeks [22]. Alternatively, a prime editing approach directly reverted the mutation to the normal sequence with 42% efficiency in erythroid precursors after 17 weeks in humanized mice [22]. The base editing approach benefited from higher efficiency, while the prime editing approach achieved the exact natural sequence with potentially fewer off-target effects.

Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR): Intellia Therapeutics' phase I clinical trial demonstrated the in vivo therapeutic potential of CRISPR-Cas9 delivered via lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) to target the TTR gene in the liver [14]. This treatment achieved approximately 90% reduction in disease-related protein levels sustained over two years, with functional improvement in symptoms [14]. This success highlights the movement of CRISPR technologies toward therapeutic reality.

Decision Framework for Technology Selection

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Base Editing Experimental Protocol

Objective: Precise correction of a point mutation using adenine or cytosine base editing.

Materials Required:

- Base editor plasmid (ABE8e for A→G or BE4max for C→T conversions)

- Target-specific sgRNA plasmid or synthetic sgRNA

- Appropriate delivery system (lipofection, electroporation, AAV)

- Target cells with known mutation

- PCR reagents for amplification of target region

- Next-generation sequencing platform for efficiency analysis

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Target Site Identification: Identify target sequence containing the pathogenic mutation. Verify that the target base falls within the optimal editing window (typically positions 4-8 for SpCas9-based editors) and check for potential bystander bases that might be unintentionally modified [23].

sgRNA Design and Preparation: Design sgRNA with 20-nt spacer sequence complementary to target site adjacent to appropriate PAM (NGG for SpCas9). Synthesize as plasmid expression construct or chemically modified synthetic sgRNA for improved stability.

Base Editor Delivery:

- For plasmid transfection: Co-transfect base editor and sgRNA plasmids at 3:1 ratio using appropriate transfection reagent.

- For RNP delivery: Pre-complex purified base editor protein with sgRNA at 3:1 molar ratio in Cas9 reaction buffer, incubate 15 minutes at room temperature, then deliver via electroporation.

- Include appropriate controls: sgRNA-only, base editor-only, and untreated cells.

Editing Efficiency Analysis:

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-delivery.

- Extract genomic DNA and amplify target region by PCR.

- Perform next-generation sequencing (minimum 10,000x coverage) or Sanger sequencing with decomposition analysis.

- Calculate editing efficiency as percentage of sequencing reads containing desired edit.

Off-Target Assessment:

- Analyze top predicted off-target sites by in silico prediction tools.

- Perform targeted sequencing of potential off-target loci.

- For therapeutic applications, conduct whole-genome sequencing to identify unexpected edits.

Troubleshooting Notes: Low editing efficiency may require optimization of sgRNA sequence, testing different base editor variants, or adjusting delivery conditions. High bystander editing may necessitate redesign to alternative target sites or switching to prime editing approach.

Prime Editing Experimental Protocol

Objective: Precise installation of specific point mutations, small insertions, or deletions.

Materials Required:

- Prime editor plasmid (PEmax recommended)

- pegRNA expression plasmid or synthetic pegRNA

- Optional: nicking sgRNA for PE3/PE3b systems

- Delivery system (electroporation recommended for hard-to-transfect cells)

- Target cells

- PCR and sequencing reagents

Step-by-Step Workflow:

pegRNA Design:

- Design pegRNA with 20-nt spacer sequence targeting desired locus.

- Engineer reverse transcriptase template (RTT) to encode desired edit with 8-15 nt of homologous sequence flanking both sides.

- Include primer binding site (PBS) of 10-15 nt complementary to DNA 3' of nick site.

- Consider using epegRNA designs with 3' RNA pseudoknots to enhance stability [24].

pegRNA Validation: Test multiple pegRNA designs for each target as efficiency varies significantly based on sequence context. Computational tools are available to predict optimal pegRNA designs.

Prime Editor Delivery:

- For plasmid transfection: Co-transfect prime editor and pegRNA plasmids at 1:3 ratio.

- For RNP delivery: Complex purified PEmax protein with in vitro transcribed pegRNA.

- For PE3/PE3b systems: Include additional nicking sgRNA plasmid or synthetic RNA.

- Include essential controls: pegRNA-only, prime editor-only, and untreated cells.

Editing Efficiency Optimization:

- Test various PBS lengths (10-15 nt) and RTT lengths.

- Evaluate different architectures (PE2, PE3, PE3b, PE5).

- Consider temporary mismatch repair inhibition (PE4/PE5 systems) to improve efficiency [24].

- Allow sufficient time for editing - analyze at 72-96 hours post-delivery.

Analysis and Validation:

- Amplify target region by PCR and sequence by next-generation sequencing.

- Calculate prime editing efficiency as percentage of reads with exact desired edit.

- Screen for byproducts including undesired insertions, deletions, or point mutations.

- For clonal applications, isolate single-cell clones and expand for comprehensive genotyping.

Troubleshooting Notes: Prime editing efficiency is highly variable across targets. If efficiency remains low after optimization, consider alternative pegRNA designs, testing specialized PE6 variants for specific edit types, or using dual-pegRNA strategies. Delivery optimization is often critical for success.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor Plasmids | PEmax, ABE8e, BE4max [24] | Express editor proteins | Choose size-optimized versions for viral delivery |

| Guide RNA Systems | pegRNA, sgRNA, epegRNA [24] | Target specification and edit template | Chemical modification improves stability |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), AAV, electroporation [14] | Deliver editing components to cells | LNPs enable redosing [14] |

| Validation Tools | NGS assays, Sanger sequencing, T7E1 assay | Assess editing efficiency and specificity | NGS provides quantitative accuracy |

| Cell Culture | Stem cell media, cytokines, transfection reagents | Maintain and edit target cells | Optimization needed for primary cells |

| Control Reagents | Off-target prediction algorithms, control gRNAs | Establish experimental specificity | Include multiple negative controls |

The CRISPR toolkit has evolved substantially from the initial Cas9 nuclease to increasingly sophisticated base editing and prime editing systems. Each technology offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them complementary rather than competing solutions. Conventional CRISPR-Cas9 remains ideal for gene disruption applications, base editors provide highly efficient point mutation correction for transition mutations within their editing windows, and prime editors offer unprecedented versatility for precise genetic manipulations including transversions, insertions, and deletions [24] [22].

Current research focuses on addressing the remaining limitations of these technologies, including further improving editing efficiency, expanding targeting scope through engineered Cas variants with altered PAM requirements, enhancing specificity to minimize off-target effects, and developing optimized delivery systems capable of transporting these large molecular machines to target tissues in vivo [23] [24]. The successful clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapies for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, along with promising ongoing clinical trials for conditions like hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis and hereditary angioedema, underscore the tremendous therapeutic potential of these technologies [14] [27].

As the field continues to advance, researchers should maintain a flexible approach to technology selection, choosing the most appropriate tool based on their specific genetic correction objective rather than defaulting to familiar methods. The protocols and comparisons provided in this application note offer a foundation for making informed decisions and implementing these powerful genome engineering technologies in both basic research and therapeutic development contexts.

Monogenic disorders, resulting from mutations in a single gene, represent a class of over 7,000 known human diseases that collectively affect approximately 300 million people worldwide [28]. Historically, treatment for these conditions has focused primarily on symptom management due to the inherent challenges in addressing their genetic roots. The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology has fundamentally shifted this therapeutic paradigm, enabling direct correction of pathogenic mutations at the DNA level [29] [30]. This powerful technology functions as a programmable molecular scissor, utilizing a Cas nuclease guided by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to create precise double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci, which are then repaired by the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms [29] [31].

The applications of CRISPR-based therapies have expanded dramatically, with the first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy (Casgevy for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia) marking a watershed moment for the field [14] [32]. Current research has further advanced beyond traditional CRISPR-Cas9 to include more precise genetic modification tools such as base editing and prime editing, which can directly convert one DNA base to another without creating double-strand breaks, thereby reducing potential off-target effects [28] [33]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the spectrum of monogenic disorders amenable to CRISPR therapy, detailed experimental protocols for researchers, and essential tools advancing this revolutionary therapeutic approach.

The Expanding Spectrum of Addressable Monogenic Disorders

CRISPR-based therapeutic strategies are being actively investigated for a wide range of monogenic diseases, with approaches tailored to the specific genetic mutation and pathological mechanism. The table below summarizes key disease targets, therapeutic strategies, and current development status.

Table 1: Monogenic Diseases Amenable to CRISPR Therapy

| Disease Category | Specific Disorders | Target Gene(s) | CRISPR Strategy | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological | Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) [31] | HBB, BCL11A | BCL11A enhancer disruption to reactivate fetal hemoglobin [32] | FDA-Approved (Casgevy) [14] |

| Transfusion-Dependent Beta Thalassemia (TDT) [31] | HBB, BCL11A | BCL11A enhancer disruption [31] | FDA-Approved (Casgevy) [14] | |

| Hemophilia A & B [31] [32] | F8, F9 | Gene correction/insertion to restore clotting factor expression [31] | Clinical Trials | |

| Neuromuscular | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) [30] | DMD | Exon skipping/deletion to restore reading frame [30] | Preclinical (mice, dog models) |

| Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) [28] | SMN2 | Base editing to convert SMN2 into SMN1-like function [28] [33] | Preclinical | |

| Metabolic | Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis (hATTR) [14] | TTR | Gene disruption to reduce pathogenic protein production [14] | Phase III Trials |

| Ornithine Transcarbamylase (OTC) Deficiency [30] | OTC | In vivo gene correction in hepatocytes [30] | Preclinical (mouse models) | |

| Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ia [33] | G6PC | Base editing to correct metabolic abnormalities [33] | Preclinical (humanized mouse model) | |

| Phenylketonuria (PKU) [30] | PAH | Gene correction in hepatocytes [30] | Preclinical (mouse, pig models) | |

| Other | Hereditary Angioedema (HAE) [14] | KLKB1 | Gene disruption to reduce kallikrein protein [14] | Phase I/II Trials |

| Cystic Fibrosis (CF) [30] | CFTR | Correction of ΔF508 mutation in epithelial cells [30] | Preclinical (cell, sheep, rabbit models) |

The diversity of strategies highlights CRISPR's versatility. For loss-of-function disorders, the goal is often gene correction or insertion, while for gain-of-function or dominant-negative disorders, gene disruption or silencing is a viable path [31]. The recent success of Casgevy exemplifies a creative indirect strategy: instead of correcting the mutated HBB gene itself, it disrupts the enhancer of BCL11A, a repressor of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), thereby reactivating HbF production to compensate for the defective adult hemoglobin [32].

Quantitative Outcomes of Leading Clinical Candidates

The efficacy of these therapies is demonstrated by robust clinical and preclinical data. The following table summarizes key quantitative outcomes from prominent studies.

Table 2: Efficacy Outcomes from Key CRISPR Therapy Studies

| Therapy / Target | Disease Model | Key Efficacy Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy (SCD/TDT) [32] | Human Patients | Proportion of HbF in total hemoglobin | 43.9% at 6 months, sustained for ≥24 months |

| hATTR Therapy [14] | Human Patients (Phase I) | Reduction in disease-related TTR protein | ~90% reduction, sustained for 2 years |

| HAE Therapy [14] | Human Patients (Phase I/II) | Reduction in kallikrein protein and attacks | 86% kallikrein reduction; 8/11 patients attack-free |

| DMD Therapy [30] | mdx mouse model | Dystrophin-positive muscle fibers | Up to 70% of myogenic area |

| OTC Deficiency Therapy [30] | spf^(ash) mouse model | Hepatocyte correction rate | ~10% of hepatocytes corrected |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Based Therapeutic Development

Protocol 1: Ex Vivo Editing of Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs) for Hemoglobinopathies

This protocol outlines the methodology used in the development of Casgevy, an autologous ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9-edited cell therapy for SCD and TDT [32].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Patient-derived CD34+ HSPCs: Sourced from bone marrow aspiration or apheresis after mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) [31] [32].

- CRISPR Reagents: Cas9 nuclease (e.g., SpCas9) and synthetic sgRNA designed to target the erythroid-specific enhancer region of the BCL11A gene [32].

- Electroporation System: Such as the Lonza 4D-Nucleofector, for efficient delivery of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into HSCs [31].

- Cell Culture Media: Serum-free expansion media supplemented with cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3-L) to maintain stem cell viability and proliferation during editing [31].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- HSC Mobilization and Collection: Mobilize hematopoietic stem cells from the patient's bone marrow into the peripheral blood using G-CSF. Collect CD34+ cells via leukapheresis and purify using immunomagnetic selection [32].

- CRISPR RNP Complex Formation: Complex purified, high-fidelity Cas9 protein with synthetic sgRNA at a predetermined molar ratio in an appropriate electroporation buffer. Incubate for 10-15 minutes at room temperature to form the RNP complex [31].

- Electroporation: Resuspend the CD34+ cells in the RNP-containing buffer and electroporate using a pre-optimized protocol for HSCs. Immediate rescue of cells into pre-warmed culture media is critical for viability [32].

- Myeloablative Conditioning: While edited cells are in culture, administer a myeloablative conditioning regimen (e.g., busulfan) to the patient to create marrow space for the engraftment of the edited HSCs [14].

- Cell Reinfusion and Engraftment: After a brief ex vivo culture period (typically 1-2 days), wash and cryopreserve the edited cells. Thaw and infuse the final product back into the patient via intravenous infusion. Monitor for engraftment (neutrophil and platelet recovery) and subsequent tracking of HbF levels [14] [32].

Protocol 2: In Vivo Gene Editing via Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) for Liver Disorders

This protocol describes the methodology for systemic in vivo gene editing, as exemplified by therapies for hATTR and the landmark case of a personalized treatment for CPS1 deficiency [14].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- LNP Formulation: CRISPR-Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles with ionizable cationic lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid components. LNPs are preferred for liver-targeted delivery due to natural tropism and lower immunogenicity compared to viral vectors [14].

- Animal Model: Validated murine or larger animal model of the target disease (e.g., Agxt1^-/- mice for primary hyperoxaluria type I) [30].

- Analytical Reagents: Antibodies for Western blot/ELISA to quantify target protein reduction, and primers for next-generation sequencing (NGS) to assess editing efficiency and off-target profiling [14] [30].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- LNP Formulation and QC: Formulate CRISPR-Cas9 mRNA and guid sgRNA into LNPs using microfluidic mixing techniques. Characterize LNPs for size (typically 70-100 nm), polydispersity, encapsulation efficiency, and endotoxin levels [14].

- Dose Determination and Administration: Establish a dosing regimen based on preclinical animal studies. Administer the LNP formulation via a single intravenous injection (e.g., tail vein in mice, peripheral IV in larger animals and humans) [14].

- Biodistribution and Efficacy Analysis: At predetermined time points post-injection, sacrifice a cohort of animals to analyze biodistribution. The liver is the primary target organ. Analyze editing efficiency in genomic DNA extracted from hepatocytes using NGS. Quantify the reduction of the pathogenic protein (e.g., TTR) in plasma by ELISA [14].

- Safety and Off-Target Analysis: Evaluate potential immunogenicity by measuring cytokine levels. Perform broad off-target analysis using in silico prediction followed by CIRCLE-seq or similar unbiased methods on genomic DNA from treated liver tissue [29] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development of CRISPR therapies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogs key solutions for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Therapeutic Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Editing Machinery | High-fidelity SpCas9 protein [29], ABE8e adenine base editor [28], CBE4 cytosine base editor [28] | Engineered proteins with improved specificity and expanded editing windows to minimize off-target effects and broaden targetable sites. |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV vectors (e.g., AAV8 for liver) [30], Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [14], Electroporation systems [31] | Enable transport of CRISPR components to target cells (in vivo) or facilitate efficient intracellular delivery (ex vivo). |

| sgRNA Tools | Chemically modified sgRNAs [31], sgRNA libraries for screening [29] | Modified sgRNAs enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity; libraries enable functional genomics and target discovery. |

| Cell Culture Systems | CD34+ HSPC expansion media [31], Human iPSCs [32] | Specialized media maintains stemness during editing; iPSCs provide a versatile patient-specific model for disease modeling and therapy development. |

| Analysis & QC Kits | NGS-based editing efficiency assays (e.g., Illumina), Off-target detection kits (e.g., GUIDE-seq) [29], ELISA for protein quantification [14] | Critical for quantifying primary editing outcomes, identifying potential off-target sites, and measuring functional phenotypic correction. |

The therapeutic landscape for monogenic diseases is being fundamentally reshaped by CRISPR-based gene editing. From the first FDA approvals for hemoglobinopathies to the rapid advancement of in vivo base editing and personalized therapies, the field is demonstrating tangible clinical success. The protocols and tools outlined herein provide a framework for researchers to advance new therapies. Future progress will hinge on overcoming persistent challenges in delivery efficiency, ensuring long-term safety, and expanding the reach of these potentially curative treatments to all patients in need.

From Bench to Bedside: Therapeutic Strategies and Clinical Applications for Genetic Diseases

The emergence of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized the therapeutic landscape for genetic disorders, presenting two fundamental strategic paradigms: ex vivo and in vivo gene editing [29] [30]. Ex vivo therapy involves the genetic modification of patient-derived cells outside the body followed by reinfusion, while in vivo therapy delivers editing machinery directly to target cells inside the patient [34]. For hematopoietic disorders such as sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia, ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) has demonstrated remarkable clinical success [35] [36]. Conversely, in vivo approaches show increasing promise for treating solid organ disorders like Duchenne muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis, where target tissues are not readily accessible for extraction [30] [37]. This application note delineates detailed protocols and strategic considerations for both approaches within the broader context of CRISPR-Cas9 applications for genetic disorder therapy, providing researchers with essential methodologies for therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Strategic Approaches

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Ex Vivo and In Vivo Therapy Approaches

| Parameter | Ex Vivo Therapy | In Vivo Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Target Cells | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), T-cells, other immunocytes [35] [36] | Hepatocytes, myocytes, neuronal cells, respiratory epithelial cells [30] |

| Therapeutic Workflow | Cell extraction → Ex vivo editing → Expansion → Reinfusion [36] | Direct systemic or localized administration of editing components [38] |

| Editing Efficiency | High (30-90% in HSPCs) [35] | Variable (5-70% depending on delivery system) [37] |

| Key Advantages | Controlled editing conditions, precise quality control, reduced immune responses, transient editor exposure [35] [36] | Non-invasive, potential for multi-tissue editing, no cell manipulation artifacts [38] [39] |

| Major Challenges | Complex cell processing, risk of cell differentiation during culture, need for conditioning regimens [35] | Delivery efficiency, immune clearance, potential off-target effects in inaccessible tissues [38] [40] |

| Ideal Disorder Types | Hematological disorders (SCD, β-thalassemia, SCID), immunodeficiencies [35] [36] | Monogenic disorders affecting solid organs (DMD, CF, OTC deficiency) [30] |

| Clinical Stage | Multiple Phase I/II/III trials (e.g., CTX001 for SCD and β-thalassemia) [36] | Early-phase clinical trials (e.g., NTLA-2001 for ATTR amyloidosis) [39] |

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes in Preclinical Models

| Disease Model | Editing Approach | Target | Efficiency | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickle Cell Disease [35] | Ex vivo (HSPCs) | HBB | >90% indel frequency | Increased HbF levels, reduced sickling |

| β-thalassemia [35] [30] | Ex vivo (HSPCs) | HBB | 93% indel frequency | Improved hemoglobin levels |

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [30] | In vivo (AAV-CRISPR) | Dystrophin | Up to 70% myogenic area | Dystrophin restoration, improved force generation |

| Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency [30] | In vivo (AAV-CRISPR) | OTC | 10% hepatocyte correction | Improved protein tolerance, survival |

| Phenylketonuria [30] | In vivo (AAV-CRISPR) | PAH | Partial hepatocyte correction | Reduced blood phenylalanine |

| Atherosclerosis [30] | In vivo (AAV-CRISPR) | LDLR | Partial rescue | Reduced cholesterol, smaller plaques |

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows for ex vivo and in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutic approaches.

Ex Vivo Therapy: Applications and Protocols for Hematopoietic Disorders

Ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 therapy has demonstrated remarkable success for hematopoietic disorders, with clinical trials showing transformative outcomes for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia [35] [36]. This approach leverages the accessibility and engraftment potential of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) to establish durable therapeutic effects.

Strategic Advantages for Hematopoietic Disorders

The hematopoietic system presents unique advantages for ex vivo editing: (1) HSPCs can be relatively easily accessed via mobilization and apheresis; (2) edited HSPCs possess the capacity to engraft and reconstitute the entire blood system; (3) ex vivo manipulation avoids systemic delivery challenges; and (4) quality control can be performed pre-infusion [35]. Furthermore, the transient exposure of cells to editing components ex vivo minimizes the risk of persistent off-target effects and immune recognition [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: HSPC Editing for Hemoglobinopathies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ex Vivo HSPC Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Isolation | CD34+ immunomagnetic selection kits (e.g., CliniMACS) | Isolation of target HSPC population with >90% purity [35] |

| Editing Machinery | SpCas9 RNPs with target-specific sgRNA | Direct delivery of precomplexed ribonucleoprotein for rapid editing with minimal off-target effects [40] |

| Delivery Method | Electroporation systems (e.g., Neon, 4D-Nucleofector) | High-efficiency RNP delivery with optimized programs for HSPCs [35] |

| Culture Media | Serum-free expansion media with cytokines (SCF, TPO, FLT3-L) | Maintenance of stemness and viability during ex vivo culture [36] |

| Quality Control | NGS-based off-target assays, flow cytometry, CFU assays | Assessment of editing efficiency, viability, and functional potential [35] |

Protocol: HSPC Editing for Hemoglobinopathies

Step 1: HSPC Mobilization and Collection

- Mobilize HSPCs using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or plerixafor [35]

- Collect cells via apheresis (yield: typically 5-20 × 10^6 CD34+ cells/kg patient weight)

- Critical Note: Patients with sickle cell disease may experience vaso-occlusive crises during mobilization - require careful monitoring [35]

Step 2: CD34+ Cell Selection and Culture

- Isplicate CD34+ cells using immunomagnetic selection (purity >90%)

- Culture cells in serum-free medium (StemSpan) supplemented with:

- Culture duration: 24-48 hours pre-editing to activate cells

Step 3: RNP Complex Formation and Delivery

- Design sgRNA targeting therapeutic locus (e.g., BCL11A erythroid enhancer for SCD)

- Complex high-fidelity SpCas9 protein with sgRNA at molar ratio 1:2

- Incubate 10-20 minutes at room temperature to form RNP complexes

- Electroporate using optimized parameters (e.g., Neon System: 1600V, 10ms, 3 pulses)

- Cell density: 1-2 × 10^6 cells per electroporation reaction [35]

Step 4: Post-Editing Culture and Quality Control

- Culture edited cells for 48 hours in expansion medium

- Assess editing efficiency: T7E1 assay or NGS (expect 30-90% indels)

- Evaluate cell viability (expect >70% recovery)

- Perform CFU assays to confirm differentiation potential [35] [36]

Step 5: Patient Conditioning and Reinfusion

- Administer myeloablative conditioning (busulfan 4-6 mg/kg)

- Thaw and wash edited cells in infusion medium

- Infuse via central venous catheter (target dose: >2 × 10^6 CD34+ cells/kg)

- Monitor for engraftment (neutrophils >500/μL by day +21, platelets >20,000/μL by day +28) [36]

In Vivo Therapy: Applications and Protocols for Solid Organ Disorders

In vivo delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutics represents a promising approach for genetic disorders affecting solid organs where ex vivo manipulation is impractical [38] [30]. This strategy requires sophisticated delivery systems to transport editing components to target tissues.

Delivery System Selection and Optimization

Table 4: Delivery Systems for In Vivo CRISPR-Cas9 Therapy

| Delivery System | Cargo Format | Advantages | Limitations | Target Tissues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) [38] [37] | Plasmid DNA | High transduction efficiency, tissue-specific serotypes, long-term expression | Limited packaging capacity (<4.7kb), immunogenicity, potential genotoxicity | Liver, muscle, CNS, retina |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) [38] [37] | mRNA, sgRNA | Modular design, high payload capacity, transient expression, reduced immunogenicity | Primarily hepatic tropism, optimization required for other tissues | Liver, immune cells |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLP) [40] [37] | RNP | Transient activity, reduced off-target effects, modular targeting | Lower editing efficiency compared to viral vectors, complex production | Broad potential |

| Extracellular Vesicles [40] | RNP, mRNA | Native biological carrier, low immunogenicity, natural targeting | Heterogeneous composition, standardization challenges | Broad potential |

Diagram 2: Decision framework for in vivo CRISPR-Cas9 delivery system selection.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: LNP-Mediated In Vivo Delivery

Protocol: LNP-Mediated In Vivo Genome Editing for Liver Disorders

Step 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Payload Design and Preparation

- For targeted gene disruption: Format Cas9 as mRNA with co-encapsulated sgRNA

- For base editing: Format base editor as mRNA with sgRNA

- For prime editing: Format prime editor as mRNA with pegRNA [35] [37]

- Critical Consideration: Optimize codon usage for target species and incorporate modified nucleotides (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine) to reduce immunogenicity and enhance stability [38]

Step 2: LNP Formulation and Characterization

- Utilize ionizable cationic lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102)

- Prepare lipid mixture in ethanol:

- Ionizable lipid (50 mol%)

- Phospholipid (10 mol%)

- Cholesterol (38.5 mol%)

- PEG-lipid (1.5 mol%)

- Prepare aqueous phase containing CRISPR mRNA/sgRNA in citrate buffer (pH 4.0)

- Use microfluidic mixer for precise nanoprecipitation (flow rate ratio 3:1 aqueous:ethanol)

- Dialyze against PBS (pH 7.4) to remove ethanol and establish neutral pH [38] [37]

- Characterize LNP properties:

- Size: 70-100 nm (dynamic light scattering)

- PDI: <0.2

- Encapsulation efficiency: >90% (RiboGreen assay)

- Endotoxin: <5 EU/mL

Step 3: In Vivo Administration and Biodistribution

- Administration route: Intravenous injection via tail vein (mice) or peripheral vein (large animals)

- Dosage: 1-3 mg mRNA/kg body weight

- Critical Note: Pre-dose with antihistamines or corticosteroids if immunogenicity concerns exist

- Assess biodistribution via quantitative PCR or bioimaging

- Expected liver tropism: >80% of administered dose [38]

Step 4: Editing Efficiency and Safety Assessment

- Collect tissue samples at peak expression (24-72 hours post-injection)

- Quantify editing efficiency:

- NGS of target locus (expect 5-70% depending on target and delivery)

- Sanger sequencing with TIDE decomposition analysis

- Assess potential off-target effects:

- GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq for unbiased off-target identification

- NGS of predicted off-target sites

- Monitor immune responses:

Step 5: Functional Efficacy Evaluation

- Measure phenotypic correction:

- Protein restoration (western blot, immunohistochemistry)

- Metabolic or functional assays specific to target disease

- Physiological improvement in disease models

- Assess durability of effect:

- Short-term (1-2 weeks): Peak editing

- Long-term (4-12 weeks): Stable phenotypic correction [30]

Advanced Genome Editing Tool Selection

Beyond standard CRISPR-Cas9 systems, advanced editors offer specialized capabilities for different therapeutic contexts.

Table 5: Advanced Genome Editing Systems for Therapeutic Applications

| Editing System | Mechanism | Therapeutic Advantages | Format Considerations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Editors [35] [37] | Chemical conversion of single bases without DSBs | Reduced indel formation, efficient in non-dividing cells | BE4max with additional nuclear localization signals | Point mutation corrections (e.g., sickle cell disease) |

| Prime Editors [35] [37] | Reverse transcriptase template-guided editing | Versatile (all transition/transversion mutations, small insertions/deletions), no DSB requirement | Dual-AAV system for packaging or smaller Cas9 orthologs | Diseases requiring precise sequence rewriting |

| CRISPR-Activated Transposases [37] | Transposase-mediated gene insertion | Large DNA insertion (>5kb) without host repair mechanisms | Optimized transposon donor design | Gene insertion therapies (e.g., factor VIII in hemophilia) |

The strategic selection between ex vivo and in vivo therapeutic approaches depends fundamentally on target tissue accessibility, disease pathophysiology, and available delivery technologies. Ex vivo editing offers precise control for hematopoietic disorders, while in vivo approaches present transformative potential for solid organ diseases. As delivery technologies continue to advance and editing precision improves, both strategies will expand their therapeutic reach. Future developments should focus on enhancing delivery efficiency to non-hepatic tissues, reducing immunogenicity, and improving safety profiles through more sophisticated editing systems and thorough preclinical assessment.

The treatment of monogenic hematologic disorders has been transformed by the advent of precise gene-editing technologies. Among these, the CRISPR-Cas9 system represents a paradigm shift in therapeutic development for severe inherited hemoglobinopathies, specifically sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT). These conditions stem from mutations in the β-globin gene (HBB) on chromosome 11, leading to defective hemoglobin synthesis, chronic anemia, and significant morbidity and mortality [41] [42]. For decades, clinical management has relied primarily on supportive care, including chronic red blood cell transfusions and iron chelation therapy, with the only curative option being allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)—a procedure limited by donor availability and significant associated risks [43] [42].

The year 2023 marked a historic turning point, as regulatory agencies in the United Kingdom, United States, and European Union granted the first approvals for CRISPR-Cas9-based therapies, Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) and Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel) [41] [44]. This review details the experimental protocols, mechanistic basis, and clinical data underpinning these advances, framing them within the broader thesis that CRISPR-Cas9 technology offers a viable, one-time functional cure for these debilitating genetic disorders.

Pathophysiological Basis and Therapeutic Targets

Sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia, while both β-hemoglobinopathies, have distinct pathophysiological mechanisms. SCD is caused by a point mutation (Glu6Val) in the HBB gene, resulting in the production of hemoglobin S (HbS). Under deoxygenated conditions, HbS polymerizes, causing erythrocytes to assume a sickled shape. This leads to hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs), and end-organ damage [41] [42]. An estimated 100,000 Americans, predominantly of African descent, live with SCD [41].

In contrast, TDT results from over 350 different mutations in the HBB gene that reduce (β+) or eliminate (β0) the synthesis of the β-globin chain. This leads to an excess of unpaired α-globin chains, which form aggregates that precipitate in erythroid precursors, causing ineffective erythropoiesis and severe anemia. Patients require lifelong transfusions, with a global prevalence of carriers estimated at 80-90 million [41] [43].

A key physiological insight underpinning CRISPR therapies is the role of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). HbF (α2γ2) is the primary hemoglobin during fetal development but is largely replaced by adult hemoglobin (HbA, α2β2) after birth. However, elevated HbF levels can ameliorate the symptoms of both SCD and TDT. In SCD, HbF interferes with HbS polymerization, while in TDT, γ-globin chains can pair with excess α-globin chains to form functional hemoglobin, compensating for the lack of β-globin [45] [42]. The transcription factor BCL11A is a known repressor of γ-globin expression and HbF production. Therefore, a primary therapeutic strategy is to disrupt the BCL11A gene or its erythroid-specific enhancer to reactivate HbF synthesis [45] [46].

Approved CRISPR-Cas9 Therapeutics: Mechanisms and Protocols

Casgevy (Exagamglogene Autotemcel)

Casgevy, developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics, is an autologous ex vivo CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited therapy. Its mechanism of action involves the disruption of a cis-acting enhancer element within the BCL11A gene, specifically in erythroid cells, to de-repress HbF production [41] [45].

Experimental and Manufacturing Protocol:

The following workflow details the standard operating procedure for Casgevy treatment, from cell collection to patient follow-up.

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Casgevy Manufacturing

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) | Autologous patient-derived cells serving as the starting material for ex vivo editing; capable of reconuting the entire hematopoietic system [45] [47]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed complex of Cas9 enzyme and synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA); directs specific cleavage in the BCL11A erythroid enhancer region. Minimizes off-target effects compared to plasmid delivery [45] [42]. |

| Electroporation System | Physical method (e.g., Nucleofector) for transiently permeabilizing cell membranes to enable efficient RNP delivery into CD34+ HSPCs with high viability [45]. |

| Myeloablative Busulfan | Conditioning chemotherapy administered to the patient prior to infusion to create marrow "space" and facilitate engraftment of the edited HSPCs [41] [44]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Cytokines | Specified serum-free media supplemented with cytokines (e.g., SCF, TPO, Fit3-L) to maintain HSPC viability and potency during the ex vivo editing process [45]. |

Lyfgenia (Lovotibeglogene Autotemcel)

Lyfgenia, developed by bluebird bio, is also an autologous cell-based gene therapy but employs a different mechanism. It uses a lentiviral vector to introduce a functional gene encoding HbAT87Q, a hemoglobin variant designed to be anti-sickling, into patient HSPCs [41] [44]. While not a CRISPR-based therapy, its concurrent approval and similar ex vivo autologous stem cell transplant protocol position it as a key pillar of the new era of gene therapy for SCD.

Quantitative Clinical Outcomes

Robust data from clinical trials demonstrate the high efficacy of these therapies, summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Summary of Efficacy Outcomes from Key Clinical Trials

| Therapy / Clinical Trial | Patient Population | Primary Efficacy Endpoint | Efficacy Results | Key Biomarker Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy (CLIMB SCD-121) [41] | SCD (n=31, age ≥12) | Freedom from severe VOC for ≥12 consecutive months | 29/31 (93.5%) of patients met the primary endpoint [41] | Robust, pancellular HbF distribution; increased total Hb |

| Casgevy (CLIMB THAL-111) [41] [43] | TDT (n=35, mean age 18.1) | Transfusion independence for ≥12 consecutive months | 32/35 (91.4%) of patients achieved transfusion independence [43] | Mean HbF: 11.9 g/dl; Mean Total Hb: 13.1 g/dl [43] |

| Lyfgenia [44] | SCD | Elimination of severe VOC (6-18 mo. post-infusion) | 94% of evaluable patients free of severe VOC [44] | Production of functional HbAT87Q |