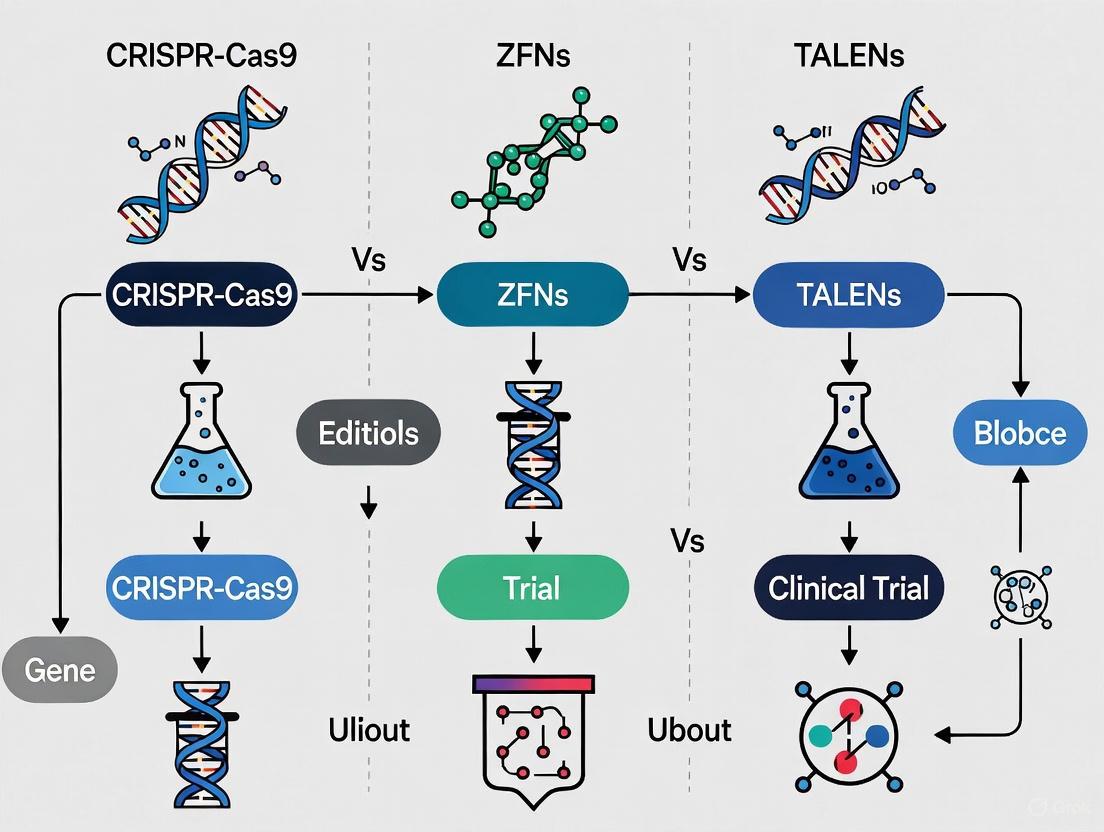

CRISPR-Cas9 vs. ZFNs and TALENs: A Comprehensive Analysis of Efficiency and Clinical Trial Applications

This article provides a systematic comparison of three major genome-editing technologies—CRISPR-Cas9, ZFNs, and TALENs—focusing on their efficiency, specificity, and clinical trial performance.

CRISPR-Cas9 vs. ZFNs and TALENs: A Comprehensive Analysis of Efficiency and Clinical Trial Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of three major genome-editing technologies—CRISPR-Cas9, ZFNs, and TALENs—focusing on their efficiency, specificity, and clinical trial performance. Drawing from recent 2025 clinical updates and parallel nuclease comparison studies, we examine foundational mechanisms, therapeutic applications across diverse diseases, and strategies for optimizing specificity and delivery. The analysis synthesizes quantitative efficiency data and off-target profiles to guide researchers and drug development professionals in platform selection for preclinical and clinical applications, while exploring future directions including base editing, prime editing, and delivery innovations.

The Evolution of Programmable Nucleases: From ZFNs to CRISPR-Cas Systems

Historical Development and Key Milestones in Gene Editing Technologies

The advent of gene-editing technologies has revolutionized molecular biology, providing researchers with the unprecedented ability to make precise modifications to genomic DNA across a wide range of organisms [1]. These technologies enable the addition, removal, or alteration of specific DNA sequences, facilitating applications from basic research to clinical therapies [1]. The field has evolved through three major generations of programmable nucleases: Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas system, with the latter emerging as the most extensively employed platform due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency [1] [2]. This review traces the historical development of these technologies, compares their functional mechanisms and performance metrics, and examines their relative efficiencies in clinical research contexts, with a particular focus on the ongoing comparison between CRISPR-Cas9 and earlier platforms (ZFNs and TALENs).

Historical Timeline of Gene Editing Technologies

Early Foundations and Meganucleases

The journey toward precision genome editing began with meganucleases, also known as homing endonucleases, which were among the first classes of programmable nucleases used for this purpose [1]. These naturally occurring enzymes recognize large DNA target sequences (14-40 base pairs) and induce site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) [1]. While meganucleases exhibited high specificity and relatively small size that facilitated delivery, their adoption was limited by the considerable difficulty in reprogramming their target specificity [1]. Recent engineering advances by companies like iECURE and Precision BioSciences have overcome some limitations, leading to new clinical applications, but the platform's complexity paved the way for more versatile systems [1].

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs): The First Generation

The first major breakthrough in programmable nucleases came with the development of ZFNs. The foundation was laid in 1985 with the identification of the first zinc-finger protein, transcription factor IIIA (TFIIIA), in Xenopus oocytes [1]. ZFNs are chimeric proteins comprising a zinc finger DNA-binding domain adapted from zinc finger-containing transcription factors, fused to the endonuclease domain of the bacterial FokI restriction enzyme [3]. Each zinc finger domain recognizes a 3-4 bp DNA sequence, and tandem arrays of these domains (typically 3-6 fingers) can be engineered to bind extended nucleotide sequences (9-18 bp) [1] [3]. ZFNs function as pairs, with each monomer binding to opposite DNA strands separated by a 5-6 bp spacer sequence; dimerization of the FokI nuclease domains across this spacer activates DNA cleavage [1]. While ZFNs demonstrated that targeted genome editing was feasible, they presented significant challenges: engineering zinc finger arrays with high affinity for desired sequences proved difficult, target site selection was limited, and concerns about off-target effects persisted [3].

TALENs: The Second Generation

The discovery of Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) from the plant pathogen Xanthomonas led to the development of TALENs, which offered substantial improvements over ZFNs [1] [3]. Similar to ZFNs, TALENs consist of a DNA-binding domain fused to a FokI nuclease domain [1]. However, their DNA recognition mechanism is notably simpler: each TALE repeat comprising 33-35 amino acids recognizes a single nucleotide through two specific amino acid residues termed Repeat Variable Di-residues (RVDs) [1]. The RVD code is straightforward: NG recognizes 'T', NI recognizes 'A', HD recognizes 'C', and NN, HN, or NK recognize 'G' [1]. This one-to-one correspondence made TALENs significantly easier to design and engineer compared to ZFNs, with target site selection having fewer constraints [3]. Despite these advantages, TALENs remained challenging to scale due to labor-intensive assembly processes and delivery difficulties stemming from their large size [1] [4].

CRISPR-Cas: The Third Generation Revolution

The most transformative development in gene editing came with the adaptation of the CRISPR-Cas system, which originated as a bacterial immune defense mechanism [5] [2]. The history of CRISPR began in 1987 when unusual repetitive sequences were first observed in the E. coli genome [5] [2]. Francisco Mojica's pioneering work in the 1990s and early 2000s revealed that these Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR), together with CRISPR-associated (cas) genes, functioned as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, providing protection against viruses and other mobile genetic elements [5]. A crucial breakthrough came in 2012 when Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, who would later receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020, elucidated the molecular mechanism of the type II CRISPR-Cas9 system and demonstrated its programmability for genome editing [5] [2]. Unlike ZFNs and TALENs that rely on protein-DNA interactions for targeting, CRISPR-Cas9 uses a guide RNA (gRNA) molecule to direct the Cas9 nuclease to specific DNA sequences through complementary base pairing [1] [2]. This RNA-programmed approach made CRISPR-Cas9 dramatically simpler, more versatile, and more accessible than previous technologies [4].

Comparative Mechanisms of Action

Fundamental DNA Recognition and Cleavage

All three major gene-editing platforms (ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9) operate through a common fundamental principle: creating targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which subsequently engage the cell's endogenous repair mechanisms [1]. However, they differ significantly in their molecular architectures and targeting mechanisms.

ZFNs utilize a protein-based recognition system where engineered zinc finger arrays bind to specific DNA sequences, with each finger recognizing approximately 3 bp [1] [3]. The FokI nuclease domain must dimerize to become active, necessitating the design of ZFN pairs that bind opposite DNA strands with proper spacing and orientation [1].

TALENs similarly employ protein-based DNA recognition through TALE repeat arrays, but with a more straightforward code where each repeat recognizes a single nucleotide via its RVDs [1] [3]. Like ZFNs, TALENs require dimerization of FokI nuclease domains for DNA cleavage [1].

CRISPR-Cas9 represents a paradigm shift from protein-based to RNA-based recognition [1] [2]. The system combines the Cas9 nuclease with a synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) containing a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target DNA [2]. Cas9 undergoes conformational changes upon gRNA binding and target recognition, activating its two nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH) that cut opposite DNA strands [2]. A critical requirement for Cas9 activity is the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site (5'-NGG-3' for the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) [2].

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

After DSB formation, cellular repair pathways determine the editing outcome. The primary pathways are:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair mechanism that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site, potentially disrupting gene function and enabling gene knockouts [1] [3].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a homologous DNA template (either endogenous or exogenously supplied) to repair the break, allowing for specific nucleotide changes or insertion of new genetic material [1] [3].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Design and Practical Implementation

The practical implementation of gene-editing technologies varies significantly in terms of design complexity, time requirements, and cost structure, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Design and Practical Implementation Parameters

| Parameter | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | Protein-based (zinc finger domains) | Protein-based (TALE repeats) | RNA-based (guide RNA) |

| Nuclease Component | FokI | FokI | Cas9 |

| Design Complexity | High (context-dependent effects) | Moderate (modular design) | Low (simple base pairing) |

| Development Timeline | ~1 month or longer [1] | ~1 month [1] | Within a week [1] |

| Relative Cost | High [1] [4] | Medium [1] | Low [1] [4] |

| Targeting Constraints | Limited targeting density (every 200 bp in random sequence) [3] | Fewer constraints, must begin with "T" [1] | Requires PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9) [2] |

Efficiency and Specificity Data from Comparative Studies

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the relative performance of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9. A landmark study using GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing) to evaluate off-target activity in HPV-targeted gene therapy revealed substantial differences in specificity [6].

Table 2: Off-Target Activity Comparison by GUIDE-seq Analysis [6]

| Target Region | CRISPR-Cas9 Off-Targets | TALENs Off-Targets | ZFN Off-Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| URR | 0 | 1 | 287 |

| E6 | 0 | 7 | Not reported |

| E7 | 4 | 36 | Not reported |

The GUIDE-seq analysis demonstrated that SpCas9 was more specific than both ZFNs and TALENs in these target regions, with ZFNs showing particularly high off-target activity in the URR region [6]. The study also found that ZFN specificity could be inversely correlated with the count of middle "G" in zinc finger proteins, and that TALEN designs with improved efficiency (using αN or NN modules) inevitably increased off-target effects [6].

Beyond specificity, CRISPR-Cas9 generally shows higher editing efficiency and greater versatility for multiplexing (simultaneously editing multiple genes) compared to traditional methods [4]. However, it's important to note that TALENs may outperform CRISPR-Cas9 in certain challenging genomic contexts, such as regions with high GC content or repetitive sequences [7].

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Assessment

GUIDE-seq Methodology for Off-Target Detection

The GUIDE-seq method represents a comprehensive approach for identifying off-target effects of gene-editing nucleases. The detailed protocol involves:

Oligonucleotide Transfection: Co-deliver nuclease components (ZFN mRNA, TALEN mRNA, or CRISPR Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes) with a blunt-ended, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag into susceptible cells using appropriate transfection methods [6].

Genomic DNA Extraction and Processing: Harvest cells 2-3 days post-transfection and extract genomic DNA. Fragment DNA using sonication or enzymatic methods and end-repair using T4 DNA polymerase, Klenow fragment, and T4 polynucleotide kinase [6].

Adapter Ligation and Amplification: Ligate sequencing adapters to the repaired DNA fragments. Perform PCR amplification using primers specific to the adapter sequences and the incorporated dsODN tag to enrich for tagged fragments [6].

High-Throughput Sequencing and Bioinformatics: Sequence the amplified libraries using high-throughput sequencing platforms. Process sequencing reads through a specialized bioinformatics pipeline to map dsODN integration sites and identify potential off-target sites across the genome [6].

Validation: Confirm identified off-target sites using independent methods such as targeted amplicon sequencing [6].

On-Target Efficiency Assessment

For comprehensive evaluation of editing technologies, on-target efficiency should be assessed through:

Surveyor or T7 Endonuclease I Assays: Detect insertion-deletion mutations (indels) at the target site through mismatch cleavage of heteroduplex DNA.

Next-Generation Sequencing: Perform targeted amplicon sequencing of the edited locus to precisely quantify editing efficiency and characterize the spectrum of induced mutations.

Flow Cytometry or Fluorescence-Based Reporter Systems: For studies involving gene correction or insertion, utilize fluorescent reporter systems to quantify HDR efficiency.

Functional Assays: Implement phenotypic or functional assays relevant to the specific target gene to confirm biological consequences of editing.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Editing Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Components | ZFN pairs, TALEN pairs, Cas9 protein, Cas9 mRNA | Core editing machinery for inducing targeted DNA breaks |

| Targeting Modules | Zinc finger arrays, TALE repeat arrays, sgRNA expression constructs | Determine target specificity of editing complexes |

| Delivery Systems | Electroporation systems, Lipid nanoparticles, AAV vectors, Lentiviral vectors | Facilitate intracellular delivery of editing components |

| Detection Assays | T7E1 surveyor assay, GUIDE-seq reagents, NGS libraries | Assess on-target efficiency and genome-wide off-target effects |

| Repair Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA donor vectors with homology arms | Enable precise editing through HDR pathway |

| Validation Tools | Antibodies for Western blot, PCR primers, Sanger sequencing | Confirm editing outcomes and protein expression |

| Cell Culture Resources | Appropriate cell lines, Culture media, Selection antibiotics | Maintain cellular systems for editing experiments |

The historical development of gene editing technologies reveals a clear trajectory toward increasing simplicity, accessibility, and versatility. While ZFNs and TALENs established the feasibility of targeted genome editing and continue to have value for specific applications where their particular characteristics are advantageous, CRISPR-Cas9 has emerged as the predominant platform due to its straightforward design, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency [1] [4]. Direct comparative studies indicate that CRISPR-Cas9 generally offers favorable efficiency and specificity profiles compared to earlier technologies, though all platforms require careful optimization and validation [6].

The future of gene editing continues to evolve with the development of more advanced CRISPR-based technologies, including base editors that enable precise single-nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks, and prime editors that can implement all twelve possible base-to-base conversions as well as small insertions and deletions [8]. These innovations, along with ongoing improvements in delivery systems and specificity, promise to further expand the therapeutic applications of gene editing in clinical research [2] [8] [9]. As the field advances, the choice between platforms will continue to depend on the specific requirements of each application, with CRISPR-Cas9 currently representing the most versatile and accessible option for most research and therapeutic contexts.

The precision of gene-editing technologies hinges on the fundamental molecular mechanisms by which proteins and RNA molecules recognize and bind to specific DNA sequences. Programmable nucleases, including Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas9 system, represent three generations of these technologies, each employing distinct recognition systems [2] [10]. ZFNs and TALENs rely on protein-DNA recognition, where custom-designed protein domains bind to specific DNA sequences [11]. In contrast, the CRISPR-Cas9 system utilizes an RNA-DNA recognition mechanism, where a guide RNA (gRNA) molecule directs the Cas nuclease to its target via Watson-Crick base pairing [12] [10]. Understanding these core mechanisms is essential for evaluating their efficiency, specificity, and applicability in clinical research. This guide provides a structured comparison of these systems, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Recognition Mechanisms

Protein-DNA Recognition Systems

Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) are fusion proteins comprising a DNA-binding domain and a FokI endonuclease domain [11]. The DNA-binding domain is composed of multiple C2H2 zinc finger modules, each recognizing a 3-base pair (bp) DNA sequence [10]. By assembling an array of these modules (typically 3 to 6), ZFNs can target a unique 9 to 18 bp sequence [11]. A significant limitation is the context-dependent affinity between fingers, which can make the design of effective ZFNs complex and time-consuming [11]. A pair of ZFNs must bind opposite strands of the DNA, flanking the cleavage site, to allow the FokI domains to dimerize and create a double-strand break (DSB) [11].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) also use the FokI nuclease domain but employ a different DNA-binding domain derived from Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) from Xanthomonas bacteria [10]. The TALE domain consists of tandem 33-35 amino acid repeats, each repeat binding to a single DNA base pair [11]. Specificity is determined by two hypervariable amino acids at positions 12 and 13, known as the Repeat Variable Diresidue (RVD) [11]. The RVD code is simple and robust: for example, Asn-Ile (NI) recognizes adenine (A), His-Asp (HD) recognizes cytosine (C), Asn-Gly (NG) recognizes thymine (T), and Asn-Asn (NN) recognizes guanine (G) or adenine (A) [11]. This one-to-one correspondence makes TALENs easier to design and more predictable than ZFNs, though the highly repetitive nature of the TALE array presents cloning challenges [10].

RNA-DNA Recognition System (CRISPR-Cas9)

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea that has been repurposed for genome editing [12] [2]. Its DNA-targeting complex consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [10]. The gRNA is a chimeric single guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines the functions of the endogenous CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [2]. The gRNA contains a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA site, facilitating recognition through RNA-DNA hybridization [12] [10]. This mechanism is fundamentally different from the protein-DNA recognition used by ZFNs and TALENs.

For the Cas9 nuclease to bind and cleave its target, the DNA sequence must be adjacent to a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [12] [10]. The canonical PAM for the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is 5'-NGG-3', where 'N' is any nucleotide [2]. The PAM sequence is recognized directly by the Cas9 protein, not the gRNA. Upon binding, the Cas9 enzyme undergoes a conformational change, and its two nuclease domains (HNH and RuvC) create a double-strand break (DSB) three base pairs upstream of the PAM site [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Recognition Mechanisms

| Feature | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition System | Protein-DNA | Protein-DNA | RNA-DNA |

| Recognition Molecule | Zinc Finger Protein (ZFP) | TALE Repeat Array | Guide RNA (gRNA) |

| Specificity Principle | Each zinc finger recognizes 3 bp | Each TALE repeat recognizes 1 bp | gRNA spacer binds via complementary base pairing |

| Target Sequence Length | 9-18 bp (for a pair) | 14-20 bp (for a pair) | ~20 nt (gRNA spacer) + PAM |

| Nuclease Domain | FokI | FokI | Cas9 (HNH & RuvC domains) |

| Key Constraint | Context-dependent finger affinity; complex design | Repetitive sequence cloning challenges | Requires a PAM sequence (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in how these systems recognize and bind to DNA.

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Data

Efficiency and Specificity Data

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the real-world performance of these technologies. A 2021 study using the GUIDE-seq method to assess off-target activity in targeting the Human Papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) genome offered a parallel comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 [13].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison in HPV16 Gene Therapy Study [13]

| Nuclease | Target Gene | On-Target Efficiency | Off-Target Count (GUIDE-seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZFN | URR | High (by T7E1 assay) | 287 - 1,856 |

| TALEN | URR | High (by T7E1 assay) | 1 |

| TALEN | E6 | High (by T7E1 assay) | 7 |

| TALEN | E7 | High (by T7E1 assay) | 36 |

| SpCas9 | URR | High (by T7E1 assay) | 0 |

| SpCas9 | E6 | High (by T7E1 assay) | 0 |

| SpCas9 | E7 | High (by T7E1 assay) | 4 |

The data shows that SpCas9 demonstrated superior specificity, with zero off-targets detected in the URR and E6 genes and only 4 in the E7 gene, outperforming ZFNs and TALENs in this specific context [13]. ZFNs, in particular, showed a high number of off-target events (287 to 1,856), which was correlated with the count of middle "G" in the zinc finger proteins [13]. The study concluded that SpCas9 was both more efficient and specific than the ZFNs and TALENs tested for HPV gene therapy [13].

Key Experimental Protocols

To contextualize the data above, below are the core methodologies used in such comparative studies.

1. GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing) This is a genome-wide method for profiling off-target nuclease activity [13].

- Procedure: Cells are transfected with the nuclease (e.g., ZFN, TALEN, or CRISPR-Cas9) along with a short, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag. When a double-strand break (DSB) occurs, this dsODN tag is integrated into the break site via the cell's repair machinery.

- Genomic DNA Extraction & Library Construction: Genomic DNA is harvested and sheared. Adaptor-ligated libraries are prepared for next-generation sequencing.

- Sequencing & Bioinformatics: High-throughput sequencing is performed. Specialized bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., those adapted for ZFNs and TALENs) are used to identify genomic locations where the dsODN tag has been integrated, which correspond to both on-target and off-target nuclease cleavage sites [13].

2. T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) Cleavage Assay This is a common method for initial validation of nuclease activity and on-target efficiency [13].

- Procedure: The genomic region surrounding the target site is amplified by PCR from nuclease-treated cells.

- Heteroduplex Formation: The PCR product is denatured and reannealed. If non-homologous indels are present due to NHEJ repair, mismatched heteroduplexes will form.

- Digestion and Analysis: The T7E1 enzyme, which cleaves at mismatched sites, is used to digest the heteroduplexed PCR products. The cleavage fragments are visualized by gel electrophoresis, and the band intensity is used to estimate the mutation frequency.

The experimental workflow for evaluating these nucleases, from design to off-target assessment, is summarized below.

Clinical Trial Context and Applications

The transition of gene-editing technologies from bench to bedside is evidenced by their growing presence in clinical trials. As of a 2023 review, there were 13, 6, and 42 registered clinical trials related to ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPRs, respectively, on ClinicalTrials.gov [13]. This distribution highlights the rapid adoption of CRISPR-Cas9 due to its ease of design and high efficiency.

- ZFN Trials: Early successes include phase I trials for HIV treatment, where ZFNs were used to disrupt the CCR5 gene in CD4+ T cells to confer resistance to the virus [13] [11].

- TALEN Trials: TALENs have been used to generate universal chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells. A prominent example is UCART19, which induced remission in a patient with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) [13].

- CRISPR Trials: CRISPR-Cas9 has the broadest clinical application. A landmark achievement was the FDA approval of Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) for sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassaemia (TDT) [10]. This therapy involves ex vivo editing of the BCL11A gene in autologous hematopoietic stem cells using CRISPR-Cas9 [10]. Ongoing trials are exploring CRISPR for cancer, HIV, and other genetic disorders [12] [10].

The primary clinical advantage of CRISPR-Cas9 lies in its rapid programmability. Designing a new gRNA is significantly faster and less expensive than engineering novel ZFN or TALEN proteins, accelerating both basic research and therapeutic development [2] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful gene-editing experiments require a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Editing Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Programmable Nuclease | The core enzyme that performs the genetic modification (e.g., ZFN, TALEN, Cas9 protein or mRNA). |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) or DNA-binding Domain Plasmid | Encodes the targeting component (gRNA for CRISPR; ZF/TALE arrays for ZFNs/TALENs). |

| Delivery Vector (Viral/Non-Viral) | Facilitates the introduction of editing components into cells (e.g., AAV, Lentivirus, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation) [2] [14]. |

| dsODN Tag (for GUIDE-seq) | Short double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide that integrates into DSB sites for unbiased off-target detection [13]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) | Enzyme used in the mismatch cleavage assay to quickly assess nuclease cutting efficiency [13]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Library Prep Kit | For preparing sequencing libraries from genomic DNA to analyze editing outcomes (on-target and off-target). |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Media, sera, and supplements for maintaining the cellular models used in the experiments. |

| Bioinformatics Software Pipeline | Critical for analyzing GUIDE-seq and NGS data to map and quantify on-target and off-target events [13]. |

The molecular recognition mechanisms underpinning ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9 fundamentally shape their application in research and clinical trials. Protein-DNA systems (ZFNs/TALENs) demonstrated the feasibility of targeted genome editing but faced challenges in design and scalability. The RNA-DNA system (CRISPR-Cas9), with its simple programmability and high efficiency, has rapidly become the dominant platform, reflected in its growing number of clinical trials and recent therapeutic approvals. Quantitative data from direct comparisons indicates that CRISPR-Cas9 can achieve superior specificity, though off-target effects remain a critical consideration for all platforms. The choice of system depends on the specific application, but the trend in clinical research strongly favors CRISPR-Cas9 and its derivatives due to their versatility and the continuous innovation in improving their precision and safety.

The advent of programmable genome editing technologies has redefined the boundaries of biological research and therapeutic development. Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas system represent three generations of engineered nucleases that enable precise genetic modifications by inducing targeted DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [15] [11]. These tools have accelerated the development of novel disease models and targeted gene therapies, with an increasing number of candidates entering clinical trials [13] [10]. A critical factor influencing the efficacy, specificity, and clinical applicability of these technologies is the fundamental design principle underpinning their creation: modular assembly. This article provides a systematic comparison of the modular design principles of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR guide RNAs, and examines how these principles impact their performance in preclinical and clinical research.

Comparative Design Principles of Engineered Nucleases

The core functionality of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas systems relies on their ability to be programmed to recognize and cleave specific DNA sequences. However, the molecular architecture and the process for assembling their DNA-recognition modules differ significantly.

Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs): Triplet-Based Modular Assembly

ZFNs are fusion proteins comprising an array of engineered Cys2-His2 zinc-finger proteins attached to the cleavage domain of the FokI restriction enzyme [15] [11]. Each zinc-finger domain is approximately 30 amino acids arranged in a conserved ββα configuration and primarily recognizes a 3-base pair (bp) DNA triplet [15] [11].

- Design Principle: The modular assembly process involves linking multiple individual zinc-finger domains in tandem to recognize an extended nucleotide sequence (typically 9-18 bp) [15] [11]. The FokI domain requires dimerization to become active; therefore, a pair of ZFNs must be designed to bind opposite strands of DNA, with their cleavage domains facing each other. The spacer between the two binding sites is critical for efficient cleavage [11].

- Assembly Challenge: A significant technical hurdle is that the assembly of zinc-finger domains with high affinity is not always straightforward, as DNA recognition by individual fingers can be influenced by context-dependent interactions with their neighbors [15] [11]. This complexity has made it difficult for non-specialists to engineer ZFNs, though open-source libraries and commercial sources (e.g., CompoZr) have been developed to provide pre-validated components [15].

The following diagram illustrates the modular structure and assembly of a ZFN pair:

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs): One-to-One Modular Assembly

TALENs share a similar chimeric structure with ZFNs, utilizing the FokI nuclease domain, but employ a different DNA-binding domain derived from Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) from Xanthomonas bacteria [15] [11].

- Design Principle: The DNA-binding domain of TALENs consists of a series of 33-35 amino acid repeats. The key discovery was that each repeat recognizes a single base pair, and the specificity is determined by two hypervariable amino acids at positions 12 and 13, known as the Repeat-Variable Diresidues (RVDs) [15] [11]. Common RVDs include:

- Assembly Challenge: While the one-to-one code simplifies design, the assembly of TALE repeat arrays is technically challenging due to the high sequence similarity between repeats, which can lead to recombination during cloning. Methods like "Golden Gate" assembly and high-throughput solid-phase assembly have been developed to overcome this, but the process can remain labor-intensive and time-consuming [15].

The logical workflow for designing and assembling TALENs is shown below:

CRISPR-Cas Systems: RNA-Guided Programmability

The CRISPR-Cas system fundamentally differs from ZFNs and TALENs by utilizing a guide RNA (gRNA) for DNA recognition, rather than engineered proteins [11] [10].

- Design Principle: The system consists of two core components: the Cas9 nuclease and a synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA). The sgRNA is a chimeric RNA molecule that combines the functions of the natural crRNA (which confers sequence specificity through ~20 nucleotides of complementarity to the target DNA) and tracrRNA (which is essential for Cas9 maturation and binding) [10]. The only strict genomic requirement for Cas9 activity is the presence of a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which is 5'-NGG-3' for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) [10].

- Assembly Workflow: Designing a new CRISPR target is exceptionally rapid. It primarily involves synthesizing a ~20 nt gRNA sequence that is complementary to the target DNA, immediately adjacent to a PAM site. This simple process eliminates the need for complex protein engineering, which is a major bottleneck for ZFNs and TALENs [4].

The simplicity of the CRISPR-Cas9 design is captured in the following workflow:

Experimental Data: Efficiency and Specificity

The differences in design principles directly translate into variations in editing efficiency and specificity, which are critical for clinical applications. A direct comparison of these technologies in preclinical models provides compelling data.

Table 1: Comparison of Gene Knock-in Efficiencies in Bovine and Goat Fetal Fibroblasts

| Editing System | Target Gene | Knock-in Cargo | Knock-in Efficiency | P-value vs. CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | Bovine MSTN | eGFP | 13.68% | P<0.01 [16] |

| ZFNs | Bovine MSTN | hFat-1 | 0% | P<0.01 [16] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Bovine MSTN | eGFP | 77.02% | - [16] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Bovine MSTN | hFat-1 | 79.01% | - [16] |

| TALENs | Goat CSN2 | eGFP | 32.35% | P<0.01 [16] |

| TALENs | Goat CSN2 | hFat-1 | 26.47% | P<0.01 [16] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Goat CSN2 | eGFP | 70.37% | - [16] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Goat CSN2 | hFat-1 | 74.29% | - [16] |

Table 2: Off-Target Profile Comparison in HPV16 Gene Therapy Context (GUIDE-seq Data)

| Editing System | Target Gene | Number of Off-Target Sites Identified |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | URR | 0 [13] |

| TALEN | URR | 1 [13] |

| ZFN | URR | 287 [13] |

| SpCas9 | E6 | 0 [13] |

| TALEN | E6 | 7 [13] |

| SpCas9 | E7 | 4 [13] |

| TALEN | E7 | 36 [13] |

The data from these studies consistently demonstrates that CRISPR/Cas9 achieves significantly higher knock-in efficiencies than ZFNs and TALENs in mammalian cell lines [16]. Furthermore, in a direct comparison of off-target activity using a sensitive genome-wide method (GUIDE-seq), SpCas9 exhibited fewer off-target sites than TALENs and ZFNs when targeting the same HPV16 viral genes, suggesting it can be a more specific tool in certain therapeutic contexts [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, this section outlines the key methodologies used to generate the comparative data.

Protocol for Comparing Knock-in Efficiencies

This protocol is adapted from the study comparing ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in efficiency in bovine and dairy goat fetal fibroblasts [16].

Nuclease and Donor Construction:

- Design and engineer ZFN, TALEN, or CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids to target a specific locus (e.g., bovine MSTN or goat CSN2).

- Construct a donor plasmid containing the cargo gene (e.g., eGFP or hFat-1) flanked by 5' and 3' homology arms corresponding to the nuclease target site.

Cell Transfection:

- Co-transfect the nuclease plasmids (ZFNs, TALENs, or CRISPR/Cas9) along with the donor plasmid into the target cells (e.g., bovine fetal fibroblasts) using electroporation.

Selection and Cloning:

- Apply antibiotic selection (e.g., G418) to eliminate non-transfected cells.

- Isolate single-cell clones using methods such as mouth pipetting, flow cytometry, or a cell shover.

Genotyping and Analysis:

- Screen for successful knock-in events by performing PCR across the homology arms of the donor plasmid.

- Confirm the PCR products by sequencing.

- Calculate the knock-in efficiency as the percentage of positive clones among the total number of selected clones.

Protocol for GUIDE-seq Off-Target Detection

This protocol is based on the study that applied GUIDE-seq to ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 for an unbiased comparison of off-target effects [13].

dsODN Tag Transfection:

- Co-deliver the engineered nuclease (ZFN, TALEN, or SpCas9 with sgRNA) and a blunt, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag into the target cells (e.g., HEK293T cells harboring HPV16 genes).

Genomic DNA Extraction and Library Preparation:

- Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- Fragment the DNA and construct sequencing libraries. Use primers specific to the dsODN tag to enrich for fragments that have been integrated at nuclease-induced DSB sites.

Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Perform high-throughput sequencing of the enriched libraries.

- Use specialized bioinformatics algorithms (as developed in the cited study) to map the sequencing reads to the reference genome and identify off-target sites where the dsODN has been integrated.

Validation:

- Validate potential off-target sites identified by GUIDE-seq using an independent method, such as targeted deep sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these genome-editing technologies requires a suite of specific reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Modular Genome Editing

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-validated ZFN Modules | Provides functional, context-dependent zinc-finger arrays for target recognition. | Available via open-source platforms (e.g., Oligomerized Pool Engineering - OPEN) or commercially (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich CompoZr) [15] [11]. |

| TALE Repeat Kit (Golden Gate Assembly) | Enables efficient and ordered assembly of TALE repeat arrays using a standardized cloning strategy. | Kits often include pre-made RVD modules for each nucleotide (NI, HD, NN, NG) to streamline construction [15]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease (WT & HiFi) | The effector enzyme that creates DSBs. High-fidelity (HiFi) variants reduce off-target effects. | Wild-type SpCas9 is commonly used. Cas9-HF1 and eSpCas9 are engineered mutants with improved specificity [4] [10]. |

| sgRNA Synthesis Kit | For in vitro transcription or chemical synthesis of guide RNAs. | Commercial kits allow for rapid production of sgRNAs from a DNA template. Custom sgRNAs can also be ordered from synthesis companies [4]. |

| Delivery Vectors | Plasmid, viral, or mRNA-based systems to introduce editing components into cells. | Plasmids (common for all); Lentivirus/AAV (for CRISPR); mRNA/protein (can reduce off-targets and immune responses) [11] [4]. |

| dsODN Tag (for GUIDE-seq) | A short, double-stranded oligonucleotide that integrates into DSBs for genome-wide off-target detection. | This is the key reagent for the GUIDE-seq method, enabling unbiased identification of off-target sites for all three nuclease types [13]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I / Mismatch Detection Assay | A quick and accessible method to detect nuclease-induced indels at the target site. | Cheaper and faster than sequencing, but less comprehensive than genome-wide methods like GUIDE-seq [13]. |

The modularity of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR guide RNAs is the foundational principle that determines their programmability, efficiency, and ultimate utility in research and therapy. While ZFNs and TALENs demonstrated the feasibility of targeted genome editing, their reliance on complex protein engineering presents a significant barrier to widespread and rapid adoption. In contrast, the RNA-guided simplicity of the CRISPR-Cas system, where targeting a new sequence requires only the synthesis of a short gRNA, has democratized genome editing [4].

Experimental data consistently shows that this design advantage translates into superior performance. CRISPR-Cas9 achieves significantly higher gene knock-in efficiencies and, in several direct comparisons, has demonstrated fewer off-target effects than ZFNs and TALENs targeting the same genomic loci [13] [16]. These factors—combined with lower cost and greater scalability—have positioned CRISPR-Cas9 as the leading platform for both basic research and clinical applications, as evidenced by the first FDA-approved CRISPR-based therapy, Casgevy [10]. As the field progresses, innovations like base editing and prime editing, which build upon the CRISPR framework, are further expanding the toolkit for precise genetic manipulation, ensuring that the principles of modular design will continue to drive the future of genetic medicine.

The clinical trial landscape for genome editing technologies has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past decade, moving from protein-engineered platforms to RNA-programmable systems. Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), the first generation of programmable nucleases, demonstrated the profound potential of targeted gene editing in clinical settings but faced significant challenges in design and accessibility [17]. Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) emerged with a more straightforward design principle, while CRISPR-Cas9 represented a paradigm shift through its RNA-guided targeting mechanism [4]. This quantitative analysis examines the clinical trial registration patterns, efficiency metrics, and technological adoption rates across these three major genome editing platforms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based comparisons to inform therapeutic development strategies.

The evolution of these technologies reflects a broader trend in clinical research toward precision medicine. As of March 2025, ClinicalTrials.gov contained 404,637 registered interventional clinical trials, with a significant peak of 27,802 trials initiated in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. Within this expansive landscape, genome editing therapies have carved out a rapidly growing niche, particularly for oncology applications, which represent the largest category of clinical trials by disease focus [18]. The quantitative comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9 in this review encompasses trial volumes, efficiency data from direct comparative studies, and analysis of technical specifications that impact their clinical applicability.

Quantitative Clinical Trial Landscape

Registered Clinical Trials by Editing Platform

Table 1: Global Clinical Trial Registration Metrics by Genome Editing Technology

| Editing Platform | Registered Clinical Trials (as of 2025) | Therapeutic Applications | Notable Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | 13 trials (as of Oct 2020) [13] | HIV resistance (CCR5 disruption), Hemophilia, MPS I/II [13] [17] | Phase 2 for HIV approach [13] |

| TALENs | 6 trials (as of Oct 2020) [13] | B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (UCART19) [13] | Phase 1 for UCART19 [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | 42 trials (as of Oct 2020) [13] | Cancer, viral infections, hereditary diseases, hematological disorders [13] [19] | Phase 3 for hATTR, SCD, and TBT [19] |

The distribution of clinical trials across editing platforms reveals a dramatic shift in research and development focus. While ZFNs and TALENs demonstrated proof-of-concept for gene editing therapies, their clinical footprint remains limited with only 13 and 6 registered trials respectively as of 2020 [13]. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas9 has experienced exponential growth with 42 registered trials by 2020, expanding to encompass diverse disease areas including cancer, viral infections, hereditary diseases, and hematological disorders [13]. The first quarter of 2025 alone saw 6,071 phase I-III interventional trials initiated across all therapeutic areas, with early-phase research accelerating significantly [20].

This transition reflects broader patterns in clinical research, where oncology continues to dominate therapeutic focus areas. In 2025, the top 10 therapeutic areas by trial volume were all in oncology, with thoracic cancer showing the highest growth rate at 25% [20]. Genome editing trials have followed this trend while also expanding into non-oncology indications, with 51% of newly initiated gene therapy trials in Q3 2024 targeting non-oncology conditions [21].

Technical Comparison of Major Genome Editing Platforms

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Design Considerations

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition System | Zinc-finger proteins [17] | RVD tandem repeat region of TALE protein [17] | Single-strand guide RNA [17] |

| Nuclease Domain | FokI [17] | FokI [17] | Cas9 [17] |

| Target Sequence Size | Typically 9–18 bp per ZFN monomer, 18–36 bp per ZFN pair [17] | Typically 14–20 bp per TALEN monomer, 28–40 bp per TALEN pair [17] | Typically 20 bp guide sequence + PAM sequence [17] |

| Targeting Limitations | Difficult to target non-G-rich sites [17] | 5ʹ targeted base must be a T for each TALEN monomer [17] | Targeted site must precede a PAM sequence [17] |

| Engineering Approach | Requiring substantial protein engineering [17] [4] | Requiring complex molecular cloning methods [17] [4] | Using standard cloning procedures and oligo synthesis [17] [4] |

| Delivery Challenges | Relatively easy as the small size of ZFN expression elements is suitable for a variety of viral vectors [17] | Difficult due to the large size of functional components [17] | Moderate as the commonly used SpCas9 is large and may cause packaging problems for viral vectors such as AAV [17] |

The technical specifications of each platform reveal fundamental differences that impact their clinical application. ZFNs employ zinc-finger proteins that typically recognize 3-bp DNA sequences per finger, with arrays of 3-6 fingers providing target specificity [17]. However, their clinical development has been constrained by the difficulty of targeting non-G-rich sites and the substantial protein engineering expertise required [17] [4]. TALENs improved targeting flexibility through TALE repeats that recognize single nucleotides, but their large size and complex molecular cloning present delivery challenges [17]. CRISPR-Cas9 significantly simplified the design process through standard cloning procedures and guide RNA synthesis, though the commonly used SpCas9 presents packaging challenges for viral vectors like AAV due to its size [17].

Direct Comparative Studies: Efficiency and Specificity

Experimental Protocol for GUIDE-seq Comparison

A landmark 2021 study provided the first direct parallel comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9 using the GUIDE-seq (genome-wide unbiased identification of double-stranded breaks enabled by sequencing) method to evaluate on-target efficiencies and genome-wide off-target activities [13]. The experimental workflow targeted three critical genes of human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16): the non-coding upstream regulatory region (URR), E6, and E7.

The methodology encompassed several key stages:

Nuclease Design and Validation: Researchers designed ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9 sgRNAs targeting identical regions of HPV16 URR, E6, and E7 genes. Initial screening using T7 endonuclease 1 (T7E1) and dsODN breakpoint PCR approaches identified efficient constructs for each platform [13].

GUIDE-seq Implementation: Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs) were integrated into nuclease-induced double-stranded breaks, serving as markers for sequencing-based identification of cleavage sites. This approach was adapted for all three nuclease platforms despite their different cleavage mechanisms [13].

Off-Target Analysis: Sequencing reads were aligned to the reference genome to identify off-target sites. Novel bioinformatics algorithms were developed to accommodate the different cutting patterns of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 [13].

Efficiency Quantification: On-target editing efficiency was measured using targeted sequencing, while specificity was assessed by the number and distribution of off-target sites identified through GUIDE-seq [13].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for GUIDE-seq comparison of gene editing platforms

Quantitative Efficiency and Specificity Results

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Editing Efficiency and Specificity in HPV16 Study

| Editing Platform | Target Gene | On-Target Efficiency | Off-Target Sites Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | URR | Variable across designs | 287-1,856 sites [13] |

| TALENs | URR | High with optimized designs | 1 site [13] |

| TALENs | E6 | High with optimized designs | 7 sites [13] |

| TALENs | E7 | High with optimized designs | 36 sites [13] |

| SpCas9 | URR | High efficiency | 0 sites [13] |

| SpCas9 | E6 | High efficiency | 0 sites [13] |

| SpCas9 | E7 | High efficiency | 4 sites [13] |

The comparative analysis revealed striking differences in both efficiency and specificity across platforms. ZFNs demonstrated substantial variability in off-target activity, with different designs generating between 287-1,856 off-target sites in the URR gene alone [13]. The study further identified that ZFN specificity inversely correlated with counts of middle "G" in zinc finger proteins, providing a design parameter for future optimization [13]. TALENs showed improved specificity over ZFNs but still generated 1-36 off-target sites depending on the target gene [13]. The research also noted that TALEN designs with improved efficiency (using αN or NN domains) inevitably increased off-target effects, highlighting a trade-off between activity and specificity [13].

Most significantly, SpCas9 outperformed both earlier platforms across all metrics, demonstrating high efficiency with zero off-target sites detected in URR and E6 genes, and only 4 off-target sites in the E7 gene [13]. This superior performance profile, combined with easier design and lower development costs, has accelerated the adoption of CRISPR-Cas9 in clinical trials despite the more established safety profiles of ZFNs and TALENs in human studies.

Clinical Trial Design and Therapeutic Applications

Phase Distribution and Enrollment Patterns

Clinical trials for genome editing technologies display distinct phase distribution patterns that reflect their developmental maturity. The overall clinical trial landscape is dominated by Phase 2 studies, which saw significant growth in 2025 with 2,278 trials initiated in the first half of the year alone [20]. Phase 1 activity also surged by 21% year-over-year, indicating a healthy pipeline of early-stage research [20]. For genome editing technologies specifically, CRISPR-Cas9 has advanced to Phase 3 trials for multiple indications, including hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), sickle cell disease (SCD), and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT) [19]. These late-stage trials represent critical milestones in translating gene editing from research concepts to approved therapies.

Trial design has evolved substantially to address the unique challenges of genome editing therapies. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain the dominant study design across clinical research, accounting for 66% of interventional trials [18]. For genome editing applications, parallel group designs are most common (59.9%), followed by single group assignment (27.4%) and crossover models (8.2%) [18]. The enrollment numbers for editing-based trials vary significantly by phase and platform, with Phase 3 trials generally having the largest median number of participants to ensure adequate statistical power for efficacy endpoints [18].

Therapeutic Area Focus and Delivery Methods

Table 4: Primary Therapeutic Applications by Editing Platform

| Editing Platform | Lead Therapeutic Areas | Notable Clinical Examples | Delivery Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | Infectious disease, Metabolic disorders [13] [17] | CCR5-disrupted CD4+ T cells for HIV resistance [13] | Ex vivo delivery using viral vectors [17] |

| TALENs | Oncology [13] | UCART19 for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [13] | Ex vivo engineering of CAR-T cells [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Hematological disorders, Genetic diseases, Oncology, Liver-related conditions [13] [19] | Casgevy for SCD and TBT [19], hATTR therapy [19] | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for in vivo delivery [19] |

The therapeutic focus of genome editing platforms has expanded from niche applications to broad disease categories. ZFNs pioneered clinical translation with an HIV therapy approach that disrupts the CCR5 co-receptor in CD4+ T cells, progressing to Phase 2 clinical trials [13]. TALENs found early success in oncology applications, particularly with universally compatible CAR-T cells (UCART19) that induced molecular remission in an infant with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [13]. CRISPR-Cas9 has diversified across multiple therapeutic areas, with notable success in hematological disorders like sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, genetic conditions such as hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, and various cancer types [13] [19].

Delivery methods have evolved significantly across platforms. Early ZFN and TALEN approaches relied predominantly on ex vivo modification of patient cells followed by reinfusion [13] [17]. CRISPR-Cas9 therapies have pioneered in vivo delivery using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that accumulate preferentially in the liver, enabling systemic administration for conditions like hATTR and hereditary angioedema [19]. The LNP delivery platform has additionally enabled multiple dosing regimens, as demonstrated by the personalized CRISPR treatment for CPS1 deficiency where an infant safely received three doses with improved outcomes following each administration [19].

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Toolkits

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing Studies

| Research Reagent | Function | Platform Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GUIDE-seq dsODNs [13] | Marker integration for genome-wide off-target detection | Universal detection pipeline for ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 [13] |

| T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) [13] | Detection of nuclease-induced mutations via mismatch cleavage | Initial efficiency screening for all three nuclease platforms [13] |

| Gal4 Reporter System [22] | Yeast-based validation of nuclease activity via reporter gene restoration | Screening and validation of effective ZFNs [22] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [19] | In vivo delivery of editing components with liver tropism | CRISPR-Cas9 delivery for hATTR, HAE, and other liver-targeted therapies [19] |

| Barbas Zinc Finger Modules [23] | Pre-characterized DNA-binding domains for ZFN construction | Modular assembly of ZFNs with expanded targeting range [23] |

The experimental toolkit for genome editing research has evolved to address the specific challenges of each platform. GUIDE-seq dsODNs have become a critical reagent for comprehensive off-target profiling, with adapted protocols now available for ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR systems [13]. The T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) assay remains a widely accessible method for initial efficiency screening across all platforms, providing a rapid assessment of nuclease activity before more comprehensive analysis [13]. For ZFN development specifically, the Gal4 Reporter System in yeast enables simultaneous screening and validation of effective nucleases, addressing the historical challenge of high failure rates with modular assembly approaches [22].

Delivery reagents represent a crucial category, with Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) emerging as the leading platform for in vivo delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components [19]. Their natural liver tropism has made them particularly suitable for therapies targeting proteins produced in the liver, such as transthyretin for hATTR and kallikrein for hereditary angioedema [19]. For ZFN development, pre-characterized Barbas Zinc Finger Modules facilitate modular assembly approaches, though success rates improve significantly with longer arrays (up to six fingers) that increase binding affinity [23].

The clinical trial landscape for genome editing technologies reveals a clear trajectory from protein-engineered platforms (ZFNs, TALENs) to RNA-programmable systems (CRISPR-Cas9). Quantitative data from clinical trial registries and direct comparative studies consistently demonstrate CRISPR-Cas9's advantages in design simplicity, efficiency, and specificity [13] [17]. The dramatic disparity in trial numbers—with CRISPR-based trials outpacing ZFNs and TALENs combined by more than 3-fold as of 2020—reflects these technical advantages and the consequent shift in research investment [13].

Despite the clear trend toward CRISPR-dominated research, earlier platforms maintain relevance for specific applications where their well-characterized safety profiles and high precision offer advantages [4]. The clinical trial ecosystem continues to evolve, with 2025 marking a significant recovery in early-phase research activity and a diversification into non-oncology indications [20] [21]. As genome editing technologies mature, successful translation will increasingly depend on addressing delivery challenges, optimizing specificity further, and navigating the evolving regulatory landscape for these transformative therapeutic modalities.

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation of Gene Editing Platforms

The therapeutic application of gene-editing technologies, including Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9, Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), is critically dependent on the delivery system used to transport the editing machinery into target cells [24] [25]. The choice of delivery method directly impacts editing efficiency, specificity, safety, and ultimately, the success of clinical trials. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three primary delivery systems—viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), and electroporation—within the context of delivering modern CRISPR-Cas9 versus the more traditional ZFNs and TALENs platforms.

Gene editing involves making precise modifications to genomic DNA. While ZFNs and TALENs rely on engineered protein domains to recognize and cut specific DNA sequences, the CRISPR-Cas9 system uses a guide RNA (gRNA) for target recognition, simplifying design and reducing costs [24] [4]. A critical challenge for all these platforms is the safe and efficient delivery of their molecular components—whether they are proteins, mRNA, or plasmid DNA—into the nucleus of target cells [26] [27].

The efficacy of a delivery system is measured by its ability to achieve high transfection efficiency (the proportion of cells that take up the editing tools) while minimizing off-target effects (unintended edits at similar DNA sites) and cytotoxicity (cell death) [26]. The optimal delivery strategy often depends on the application, particularly whether the editing is performed ex vivo (on cells outside the body) or in vivo (inside the body).

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Systems

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of viral vectors, LNPs, and electroporation for delivering gene-editing reagents.

| Delivery System | Mechanism of Action | Typical Payload | Editing Efficiency | Off-Target Risk | Immunogenicity & Safety | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV, Lentivirus) | Viral infection mediates cellular entry and gene delivery [28]. | DNA encoding editors [26]. | High [28]. | Sustained editor expression can increase risk [26]. | Moderate to High; pre-existing immunity and inflammatory responses are concerns [26] [28]. | In vivo therapy; ex vivo stem cell editing [28] [27]. | Long-term expression; High tropism for specific tissues [28]. | Limited packaging capacity; risk of insertional mutagenesis [26] [28]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Endocytosis; lipids fuse with cell membrane to release payload [28]. | mRNA, RNP complexes [26]. | Moderate to High (especially in liver) [26]. | Transient activity lowers risk [26]. | Low; suitable for repeated dosing [28]. | In vivo therapy (e.g., mRNA vaccines); systemic delivery [26] [28]. | Rapid manufacturing; large payload capacity; low immunogenicity [26] [28]. | Primarily transient expression; challenge of targeting specific tissues beyond the liver [28]. |

| Electroporation | Electrical pulses create transient pores in cell membrane [27]. | RNP complexes, plasmid DNA [27]. | Very High (in ex vivo settings) [27]. | Low (especially with RNP delivery) [27]. | High cytotoxicity if parameters are not optimized [27]. | Ex vivo cell engineering (e.g., stem cells, T cells) [27]. | High efficiency for hard-to-transfect cells; direct delivery of RNPs minimizes off-targets [27]. | Not suitable for in vivo delivery; can cause significant cell death [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Delivery and Evaluation

To illustrate how these delivery systems are evaluated in a research setting, below is a detailed protocol for a typical ex vivo gene-editing experiment using electroporation, a common method for clinical applications involving immune cells or stem cells.

Detailed Methodology: Ex Vivo Gene Editing of T Cells via Electroporation

This protocol outlines the steps for knocking out a gene in human primary T cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system delivered as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex via electroporation [27].

1. Preparation of Gene-Editing Components

- CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex Formation: Synthesize and purify a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the gene of interest. Complex the sgRNA with recombinant Cas9 protein at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 (Cas9:gRNA) in a nuclease-free buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to allow RNP formation [27].

- Cell Isolation and Activation: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from a donor blood sample using density gradient centrifugation. Isolate T cells using a negative selection kit. Activate the T cells by culturing them in a medium supplemented with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and IL-2 for 24-48 hours [27].

2. Electroporation Delivery

- Cell Preparation: Harvest activated T cells and resuspend them in an electroporation-compatible buffer at a concentration of 1-2 x 10^7 cells/mL.

- Electroporation Setup: Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex. Transfer the mixture to an electroporation cuvette.

- Electrical Parameters: Apply one or more electrical pulses using a square-wave electroporator. Optimal parameters for primary T cells are typically a voltage of 1500-2000 V, pulse width of 10-20 ms, and a single pulse [27].

- Post-Transfection Recovery: Immediately after pulsing, transfer the cells to pre-warmed culture medium and incubate at 37°C. Analyze cell viability 24 hours post-electroporation, expecting 50-80% viability with optimized protocols [27].

3. Assessment of Editing Outcomes

- Efficiency Analysis (48-72 hours post-editing): Harvest genomic DNA from a sample of edited cells. Use a mismatch detection assay (e.g., T7E1 or TIDE) to quantify the percentage of insertions/deletions (indels) at the target locus. For precise quantification, perform next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the amplified target region [27].

- Functional Validation (7-14 days post-editing): Evaluate the knockout efficiency at the protein level using flow cytometry (if targeting a surface receptor) or Western blot. Perform functional assays relevant to the target gene, such as cytokine release assays or target cell killing assays for engineered T cells [24].

- Safety Profiling: Perform whole-genome sequencing or dedicated off-target analysis methods (e.g., GUIDE-seq) on the edited cell population to identify and quantify any unintended genomic modifications [24] [27].

Diagram Title: Ex Vivo Gene Editing Workflow via Electroporation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Successful implementation of gene-editing delivery protocols requires specific reagents and materials. The table below lists key solutions for the electroporation protocol described above.

| Research Reagent Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The core nuclease enzyme that creates double-strand breaks in DNA [27]. | Forming the RNP complex for delivery via electroporation or LNPs to reduce off-target effects and duration of editor activity [27]. |

| In Vitro-Transcribed sgRNA | A synthetic RNA molecule that guides the Cas9 protein to the specific target DNA sequence [27]. | Programming the CRISPR-Cas9 system to edit a specific gene; can be easily designed and synthesized for new targets. |

| Electroporation Buffer & Kits | Specialized, low-conductivity solutions that maintain cell viability during electrical pulsing [27]. | Resuspending cells for electroporation to ensure efficient delivery of RNP, mRNA, or DNA with minimal cell death. |

| Anti-CD3/CD28 Activator | Magnetic beads or antibodies that simulate antigen presentation to activate T cells [27]. | Priming primary T cells for expansion and making them more receptive to electroporation and gene editing. |

| Cytokines (e.g., IL-2) | Signaling proteins that regulate immune cell growth and differentiation [27]. | Added to culture medium to support T-cell survival and proliferation after activation and the stress of electroporation. |

| Nuclease Detection Assay | Enzymatic kits (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I) that detect mismatches in heteroduplex DNA [27]. | Rapid, initial quantification of gene-editing efficiency at the target locus by measuring the rate of indels. |

The choice between viral vectors, LNPs, and electroporation is not one-size-fits-all and is deeply intertwined with the choice of gene-editing platform. The simplicity and versatility of CRISPR-Cas9 have synergized with advancements in LNP and RNP electroporation, enabling scalable and transient delivery that is well-suited for many clinical applications [26] [4]. In contrast, the complexity and cost of engineering ZFNs and TALENs have limited their delivery primarily to viral vectors or ex vivo electroporation, confining them to niche applications where their high specificity is paramount [4].

Future progress will focus on developing next-generation delivery systems with enhanced tissue targeting and reduced immunogenicity. Hybrid approaches, which combine the favorable attributes of different systems, are also emerging [28]. As delivery technologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly unlock the full therapeutic potential of gene editing, enabling more effective and safer treatments for a wide range of genetic disorders.

Diagram Title: Delivery System Profiles and Best-Fit Applications

Ex vivo gene therapy represents a revolutionary approach in modern medicine, wherein cells are extracted from a patient, genetically modified outside the body, and then reinfused to treat disease. This field has rapidly evolved from a research concept to a clinical reality, particularly for hematological malignancies and genetic disorders. The core advantage of ex vivo manipulation lies in the controlled introduction of genetic modifications while avoiding the immune responses and delivery challenges associated with in vivo approaches. Current technological landscapes show that 79.78% of ex vivo gene therapies target neoplasms, with T cells as the primary cell type (75.26%) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) being the most common genetic modification (83.19%) [29]. While stem cells constitute a smaller proportion (2.41%), they have demonstrated significant clinical promise, especially hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) for genetic blood disorders [29].

The emergence of precise genome editing tools has dramatically accelerated ex vivo therapy development. Three major generations of programmable nucleases have enabled targeted genetic modifications: Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and CRISPR-associated systems (CRISPR-Cas9) [11]. Each platform offers distinct mechanisms for creating double-strand breaks in DNA, triggering cellular repair processes that can be harnessed for therapeutic gene editing. The choice among these platforms involves careful consideration of efficiency, specificity, cost, and ease of design – factors critically important for clinical applications where safety and efficacy are paramount.

Table 1: Overview of Major Genome Editing Platforms

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-binding mechanism | Protein-based (zinc finger domains) | Protein-based (TALE repeats) | RNA-based (guide RNA) |

| Target recognition | 3-4 bp per zinc finger domain | 1 bp per TALE repeat | 20 bp guide RNA sequence + PAM |

| Nuclease component | FokI dimer | FokI dimer | Cas9 single protein |

| Ease of design | Complex, requires specialized expertise | Moderate, modular but repetitive | Simple, requires only guide RNA design |

| Development timeline | 2000s | 2010s | 2012-present |

| Multiplexing capacity | Limited | Limited | High (multiple gRNAs) |

Genome Editing Platforms: Mechanisms and Evolution

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

Each genome editing platform operates through distinct molecular mechanisms to achieve targeted DNA modification:

ZFNs are fusion proteins comprising an array of site-specific DNA-binding domains adapted from zinc finger-containing transcription factors, attached to the endonuclease domain of the bacterial FokI restriction enzyme. Each zinc finger domain recognizes a 3- to 4-bp DNA sequence, and tandem domains can bind extended nucleotide sequences (typically 9-18 bp). ZFNs function as pairs that recognize two sequences flanking the target site, one on each DNA strand. Upon binding, the FokI domains dimerize and cleave the DNA, generating a double-strand break (DSB) with 5' overhangs [11].

TALENs similarly fuse DNA-binding domains to FokI nuclease domains but use transcription activator-like effector (TALE) repeats derived from plant pathogens. Each TALE repeat is 33-35 amino acids long with two adjacent residues (repeat-variable di-residues or RVDs) conferring specificity for a single DNA base pair. This one-to-one correspondence between TALE repeats and DNA bases provides greater design flexibility than ZFNs. Like ZFNs, TALENs function as pairs binding opposite DNA strands, with FokI dimerization required for DSB formation [11].

CRISPR-Cas9 systems originated as adaptive immune mechanisms in bacteria and archaea. The most widely used CRISPR-Cas9 system employs a single Cas9 nuclease guided by a synthetic RNA molecule (guide RNA or gRNA) that combines tractRNA and crRNA functions. The gRNA directs Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM, typically 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9). Cas9 then generates a blunt-ended DSB approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [13] [11].

All three platforms leverage cellular DNA repair mechanisms after creating DSBs: error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, while homology-directed repair (HDR) can introduce precise genetic modifications using an exogenous DNA template [11].

Evolution of Editing Platforms

The development of genome editing technologies has progressed through distinct generations, each addressing limitations of its predecessors:

First-generation ZFNs faced challenges in design and validation, as assembling zinc finger domains to bind extended nucleotide sequences with high affinity proved difficult for nonspecialists. Open-source libraries and protocols eventually improved accessibility, but design constraints remained, with target sites limited to approximately every 200 bp in random DNA sequences using open-source components [11].

Second-generation TALENs emerged with a more straightforward design paradigm due to the modular one-repeat-to-one-base recognition code. While still requiring protein engineering, TALEN design became more accessible to nonspecialists. However, the highly repetitive nature of TALE arrays made cloning and delivery challenging, and the large size of TALEN constructs presented difficulties for viral vector packaging [11].

Third-generation CRISPR-Cas systems revolutionized the field through their simplicity and versatility. The RNA-guided approach eliminated the need for complex protein engineering – designing new targets requires only synthesis of a short gRNA sequence. This dramatically reduced costs, time requirements, and technical barriers. Additionally, CRISPR enabled facile multiplexing by introducing multiple gRNAs simultaneously, a capability severely limited in ZFN and TALEN platforms [13] [11].

Diagram Title: Evolution of Genome Editing Platforms

Comparative Performance Analysis in Ex Vivo Applications

Editing Efficiency and Specificity Data

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the performance characteristics of different editing platforms. A comprehensive study targeting human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) genes compared the efficiency and specificity of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 using genome-wide unbiased identification of double-stranded breaks enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq) [13].

Table 2: Editing Efficiency and Off-Target Profile Comparison in HPV16 Model

| Editing Platform | Target Gene | On-target Efficiency | Off-target Sites Identified | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | URR | Variable across designs | 287-1,856 sites | Specificity correlated with "G" content in zinc fingers |

| TALENs | URR | High | 1 site | Design variations (αN/NN) increased efficiency but also off-targets |

| TALENs | E6 | High | 7 sites | - |

| TALENs | E7 | High | 36 sites | - |

| SpCas9 | URR | High | 0 sites | - |

| SpCas9 | E6 | High | 0 sites | - |

| SpCas9 | E7 | High | 4 sites | - |

The study demonstrated that SpCas9 generally exhibited higher efficiency and specificity compared to ZFNs and TALENs, with fewer off-target events across all target genes [13]. Specifically, in the URR gene, SpCas9 generated no detectable off-target sites, while ZFNs produced hundreds to thousands depending on the specific design. The variability in ZFN performance was particularly notable, with specificity reversely correlated with the count of middle "G" nucleotides in zinc finger proteins [13].

Applications in CAR-T Cell Engineering

CAR-T cell therapy has emerged as a breakthrough treatment for hematological malignancies, with six FDA-approved products for B-cell malignancies and multiple myeloma [30] [31]. The engineering of CAR-T cells exemplifies the application of genome editing technologies in ex vivo therapies.

CAR Structure and Generations: CARs are synthetic receptors consisting of three major domains: an extracellular antigen-recognition domain (typically a single-chain variable fragment or scFv), a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain [30] [31]. CAR-T cells have evolved through multiple generations:

- First-generation: CD3ζ chain only, showed limited persistence and efficacy

- Second-generation: Added one costimulatory domain (CD28 or 4-1BB), significantly improved persistence and antitumor activity

- Third-generation: Combined multiple costimulatory domains (e.g., CD28 + 4-1BB)

- Fourth-generation ("TRUCKs"): Engineered to secrete cytokines or express additional proteins

- Fifth-generation: Incorporates additional membrane receptors like IL-2 receptor for JAK/STAT signaling [31]

Current FDA-approved CAR-T products are predominantly second-generation, with either CD28 or 4-1BB costimulatory domains [31]. The choice of costimulatory domain affects T-cell metabolism and persistence – CD28 domains promote effector memory phenotype and aerobic glycolysis, while 4-1BB domains favor central memory development and fatty acid metabolism, resulting in longer persistence [30].

Editing Platform Applications: Genome editing enhances CAR-T therapy through several approaches:

- Gene disruption: Knocking out endogenous T-cell receptors to prevent graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic approaches

- Insertion of CAR constructs: Targeted integration of CAR genes into specific genomic loci

- Modification of checkpoint molecules: Disrupting PD-1 or other inhibitory receptors to enhance antitumor activity

CRISPR-Cas9 has become the preferred platform for many of these applications due to its multiplexing capability and ease of design. For instance, simultaneously disrupting multiple checkpoint genes while inserting a CAR construct can be accomplished with a single CRISPR delivery [31]. Furthermore, CRISPR enables precise integration of CAR genes into specific loci like the TRAC (T cell receptor alpha constant) locus, which suppresses endogenous TCR expression while potentially enhancing CAR-T cell stability and function [31].

Applications in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Therapies

Ex vivo gene editing of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) holds promise for treating genetic blood disorders like sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Recent advances have addressed long-standing challenges in HSC manipulation: