CRISPR-Mediated SOX9 Editing in Primary Immune Cells: Strategies for Enhancing Efficiency and Therapeutic Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing SOX9 gene editing in primary immune cells.

CRISPR-Mediated SOX9 Editing in Primary Immune Cells: Strategies for Enhancing Efficiency and Therapeutic Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing SOX9 gene editing in primary immune cells. SOX9 is a transcription factor with a dual role in immunology, acting as both a promoter of tumor immune escape and a facilitator of tissue repair. We explore the foundational biology of SOX9 in immune cell function, detail advanced CRISPR-Cas delivery systems including viral vectors and ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), and present strategies for troubleshooting low editing efficiency. The content further covers rigorous validation techniques to assess functional outcomes, such as changes in immune cell differentiation and cytokine production. By synthesizing current methodologies and validation frameworks, this resource aims to accelerate the development of SOX9-targeted immunotherapies for cancer and inflammatory diseases.

SOX9 in Immunity: Decoding Its Dual Role as an Oncogene and Regulator

SOX9 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9) is a transcription factor with a high-mobility group (HMG) DNA-binding domain that plays critical yet contradictory roles in both cancer progression and tissue repair. This "Janus-faced" character makes it a compelling but challenging therapeutic target. Research focuses on leveraging CRISPR-based gene editing to precisely manipulate SOX9 to harness its beneficial functions while suppressing its detrimental effects [1] [2].

Key Functional Domains of SOX9 Protein: The illustration below shows the primary functional domains of the human SOX9 protein and their roles.

Core Experimental Workflow for SOX9 Manipulation

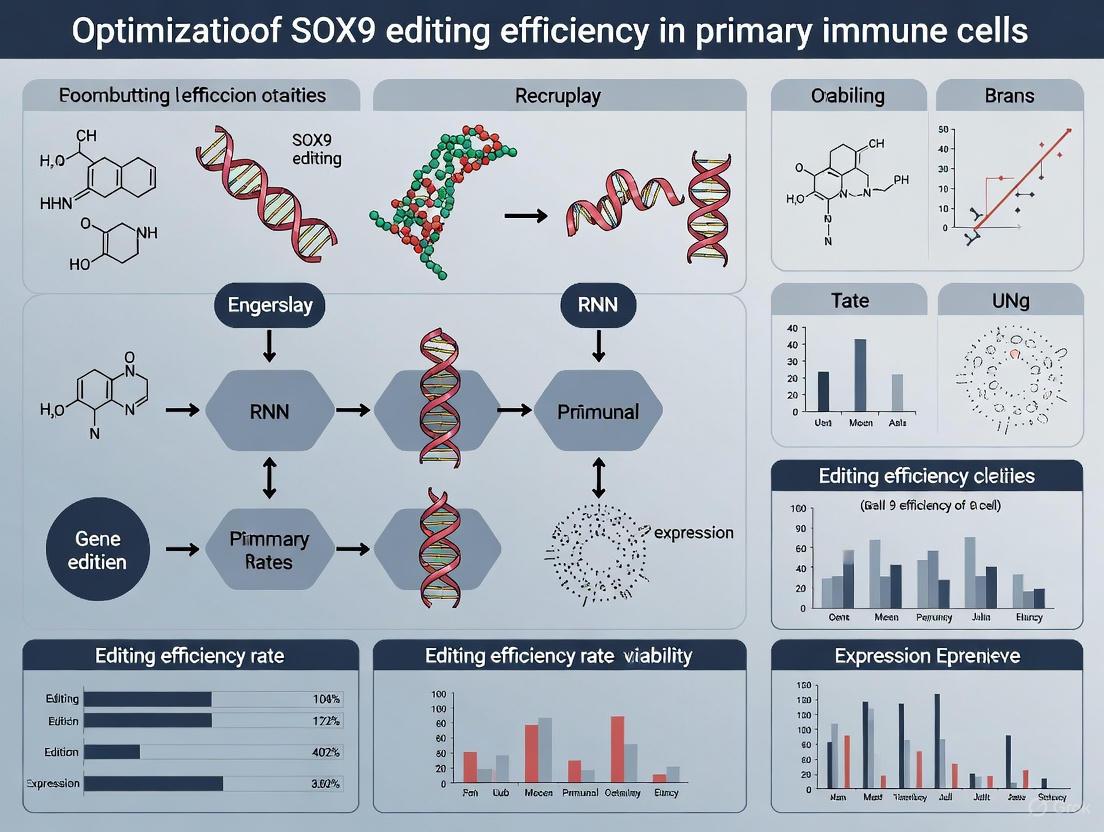

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for modulating SOX9 in primary immune cells for therapeutic purposes, integrating strategies from recent studies.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for SOX9 Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | dSpCas9-VP64 (CRISPRa), dSaCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi) [3] | Transcriptional activation (VP64) or inhibition (KRAB) of SOX9. | Allows fine-tuning of gene expression without permanent DNA changes. |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral vectors, hiNLS-Cas9 RNPs [3] [4] | Introducing CRISPR machinery into cells. | hiNLS-Cas9 enhances nuclear localization and editing efficiency in primary lymphocytes [4]. |

| Targeting Guides | Dual-gRNA vectors (e.g., Lenti-EGFP-dual-gRNA) [3] | Simultaneously express gRNAs for SpCas9 and SaCas9 to target multiple genes. | Enables coordinated activation of SOX9 and inhibition of RelA [3]. |

| Cell Culture | Primary human T cells, Bone Marrow Stromal Cells (BMSCs) [3] [5] | T cells: Immunotherapy research. BMSCs: Tissue repair models (e.g., osteoarthritis). | Primary cells are therapeutically relevant but challenging to edit [5]. |

| Analysis Kits | RNA-seq, scRNA-seq, Western Blot, FACS | Validate editing efficiency and functional outcomes (gene expression, protein levels). | scRNA-seq is crucial for analyzing heterogeneous cell populations [3]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Question: Our editing efficiency in primary human T cells is low. How can we improve this?

Answer: Low editing efficiency in primary cells is a common hurdle. Consider these strategies:

- Use hiNLS-Cas9 Constructs: A 2025 study demonstrated that incorporating hairpin internal Nuclear Localization Signals (hiNLS) within the Cas9 backbone, rather than using terminally fused NLS, significantly enhances nuclear import and editing efficiency in primary human T cells. This is critical when using transient delivery methods like Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) [4].

- Optimize Delivery Method: Electroporation of pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNPs is often the most efficient method for primary T cells. RNP delivery is transient, reducing off-target effects and immune responses [5] [4].

- Validate gRNA Activity: Always pre-screen gRNAs in easy-to-transfect cell lines before moving to primary cells. The sequence and purity of the gRNA are critical.

Question: How can we safely manipulate the dual nature of SOX9 without triggering oncogenesis in therapeutic applications?

Answer: The key is precise, context-specific modulation rather than complete knockout or strong overexpression.

- Employ CRISPRa/i: Use catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional activators (VP64) or repressors (KRAB) to fine-tune SOX9 expression to desired levels. This approach avoids permanent DNA breaks and captures the gene's natural regulation by intrinsic signaling factors [3] [6].

- Target Downstream Pathways: Instead of targeting SOX9 directly, manipulate its key downstream effectors or interacting partners in a tissue-specific manner. For example, in osteoarthritis, simultaneously activating SOX9 while inhibiting the inflammatory factor RelA (a component of NF-κB) enhanced chondrogenesis and reduced inflammation [3].

- Use Tissue-Specific Promoters: Control the expression of your CRISPR machinery with promoters that are active only in your cell type of interest (e.g., a chondrocyte-specific promoter for cartilage repair) to minimize off-target effects in other tissues.

Question: We need to model the complex role of SOX9 in the tumor immune microenvironment. What are the best functional assays?

Answer: Moving beyond simple expression analysis is crucial.

- Co-culture Assays: Co-culture SOX9-edited cancer cells with primary immune cells (e.g., T cells, macrophages). Measure T-cell killing efficiency, cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ), and expression of exhaustion markers (e.g., PD-1, LAG-3) [7] [1].

- In Vivo Validation: Use immunocompetent mouse models of cancer. Analyze how SOX9-modulated tumors influence immune cell infiltration (e.g., CD8+ T cells, Tregs, M1/M2 macrophages) via flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Bioinformatic analysis of human cancer data (e.g., TCGA) can correlate SOX9 levels with immune cell signatures [1].

- Plaque Clearance Assay: For non-cancer contexts like Alzheimer's, a key functional assay is to co-culture SOX9-enhanced astrocytes with amyloid-β plaques and measure phagocytic clearance [8].

Key Experimental Data and Quantitative Findings

Table: Summary of Key Experimental Outcomes from SOX9 Research

| Study Focus | Experimental Model | Key Intervention | Primary Quantitative Outcome | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis (OA) Treatment | Mouse OA model [3] | IA injection of BMSCs with CRISPRa-Sox9 + CRISPRi-Rela | Significant attenuation of cartilage degradation; pain relief. | Promoted cartilage integrity, inhibited catabolic enzymes, suppressed immune cell activation. |

| Alzheimer's Disease Model | Symptomatic Alzheimer's mouse models [8] | Overexpression of Sox9 in brain astrocytes | Improved cognitive performance in memory tests; reduced amyloid-β plaque levels over 6 months. | Enhanced plaque phagocytosis ("vacuuming") by astrocytes, preserving cognitive function. |

| Melanoma Initiation | Genetic melanoma mouse model; human melanoma cells [9] | Sox10 knockdown leading to Sox9 upregulation | Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in melanoma cells. | Sox9 activation exhibited an anti-tumorigenic effect, antagonizing Sox10's pro-tumorigenic role. |

| Breast Cancer Proliferation | Breast cancer cell lines (e.g., T47D, MCF-7) [7] | SOX9 knockdown / overexpression | SOX9 inactivation reduced tumor occurrence; SOX9 promoted proliferation via AKT/SOX10 and HDAC9 pathways. | SOX9 acts as a driver of tumor initiation and proliferation, particularly in basal-like breast cancer. |

| Editing Efficiency | Primary human T cells [4] | hiNLS-Cas9 RNP delivery | Enhanced knockout efficiencies for genes like B2M and TRAC compared to standard NLS-Cas9. | Improved nuclear import and editing efficiency, critical for therapeutic development. |

Signaling Pathways in SOX9 Function

The diagram below summarizes the dual and context-dependent signaling pathways of SOX9, highlighting its opposing roles in cancer versus tissue repair.

FAQ: Understanding SOX9 Structure and Function

What is the primary functional domains of the SOX9 protein?

The human SOX9 protein comprises 509 amino acids and contains several key functional domains that govern its activity as a transcription factor [10]:

- HMG Box: A high mobility group DNA-binding domain that facilitates sequence-specific DNA binding to the consensus motif AGAACAATGG (with AACAAT as the core element). This domain binds the minor groove of DNA, inducing DNA bending by forming an L-shaped complex [10].

- Dimerization Domain (DIM): Enables SOX9 homodimerization, which is required for DNA binding and transactivation of cartilage-specific genes. SOXE proteins (SOX8, SOX9, SOX10) can also heterodimerize through this domain [10].

- Transactivation Domains: Two activation domains located in the middle (TAM) and C-terminus (TAC) of the protein that interact with transcriptional co-activators. The TAC domain physically interacts with MED12, CBP/p300, TIP60, and WWP2 to enhance transcriptional activity [10].

- PQA-Rich Domain: A proline/glutamine/alanine-rich domain that enhances transactivation capability but lacks autonomous transactivation function [10].

How does SOX9 bind DNA and regulate transcription in different cellular contexts?

SOX9 exhibits two distinct modes of action on the genome, as identified in chondrocyte studies [11]:

- Class I Sites: SOX9 associates indirectly with transcriptional start sites of highly expressed genes with no chondrocyte-specific signature through protein-protein interactions with basal transcriptional components.

- Class II Sites: SOX9 directly binds through sub-optimal Sox9-dimer binding to evolutionarily conserved active enhancers that regulate chondrocyte-specific gene activity. The number and grouping of these enhancers into super-enhancer clusters likely determines target gene expression levels [11].

The protein can function as either a monomer (e.g., in testicular Sertoli cells) or dimer (e.g., in chondrocytes), with active SOX9-binding dimer motifs in regulatory regions showing cell-type specificity [10].

What technical challenges are associated with studying SOX9 function in immune cells?

Research on SOX9 in primary immune cells faces several technical hurdles:

- Low Editing Efficiency: CRISPR-mediated knock-ins rely on homology-directed repair (HDR), which is inefficient in primary B cells and T cells that often reside in a quiescent state favoring non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) over HDR [12].

- Cellular Toxicity: Standard CRISPR/Cas9 delivery methods can be toxic to primary immune cells, reducing viability and experimental yield.

- Nuclear Localization Limitations: The transient nature of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes (1-2 day half-life) requires rapid nuclear localization for effective editing before metabolic degradation [4].

Troubleshooting SOX9 Editing in Primary Immune Cells

Problem: Low CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency in primary human lymphocytes

Solution: Implement advanced nuclear localization signal (NLS) engineering to enhance editing efficiency [4].

Table: Optimization Strategies for SOX9 Editing in Primary Immune Cells

| Challenge | Solution | Experimental Notes | Expected Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor nuclear import of Cas9 | Use hairpin internal NLS (hiNLS) constructs instead of terminally fused NLS | Install hiNLS at selected sites within Cas9 backbone | Enhanced editing efficiency in primary T cells compared to standard NLS constructs |

| Low HDR efficiency in quiescent cells | Optimize HDR template design with appropriate homology arm lengths | Use 30-60 nt for short donor oligos; 200-300 nt for longer HDR donors | Increased knock-in rates through improved homologous recombination |

| Cellular preference for NHEJ over HDR | Consider cell cycle synchronization strategies | Target cells in S/G2 phases when HDR is more active | Can improve HDR efficiency by 2-5 fold in some cell types |

| Unwanted re-cutting of edited loci | Incorporate silent mutations in PAM sites in donor templates | Design templates that disrupt Cas9 binding after successful editing | Reduces repetitive cutting and improves cell viability |

Experimental Protocol: Enhanced RNP Delivery for SOX9 Editing

This protocol adapts recently published approaches for high-efficiency editing in primary immune cells [12] [4]:

hiNLS-Cas9 RNP Complex Preparation:

- Use hiNLS-Cas9 constructs instead of standard NLS-Cas9

- Complex with chemically modified sgRNA targeting SOX9 genomic locus

- Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to form RNP complexes

Primary Immune Cell Electroporation:

- Isolate primary human B cells or T cells from fresh blood samples

- Resuspend 1×10^6 cells in 20μL electroporation buffer

- Add 5μL of prepared RNP complexes (final concentration 2μM)

- Electroporate using optimized settings (e.g., 1350V, 30ms pulse width, 2 pulses)

HDR Template Design Considerations:

- For single nucleotide changes or small tags: use single-stranded DNA templates

- For larger inserts (e.g., fluorescent proteins): use plasmid templates with 500nt homology arms

- Consider strand preference: targeting strand preferred for PAM-proximal edits, non-targeting strand for PAM-distal edits [12]

Post-Editing Analysis:

- Assess editing efficiency at 48-72 hours post-electroporation via flow cytometry or sequencing

- Evaluate cell viability using trypan blue exclusion

- Validate functional outcomes through Western blot or qPCR for SOX9 expression

Problem: Inconsistent SOX9 transcriptional activity across different immune cell subtypes

Solution: Account for cell-type specific co-factors and chromatin accessibility.

SOX9's transcriptional activity depends on tissue-specific accessibility to target gene chromatin and the availability of binding partners [10]. In immune cells, this may mean:

- Pre-screening chromatin accessibility via ATAC-seq to identify open chromatin regions near SOX9 targets

- Evaluating expression of known SOX9 co-factors (MED12, CBP/p300, TIP60) in your specific immune cell type

- Considering cell-specific differentiation state, as SOX9 function varies between progenitor and differentiated cells

Research Reagent Solutions for SOX9 Studies

Table: Essential Reagents for SOX9 Research in Immune Cells

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Method | Application in SOX9 Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Editors | hiNLS-Cas9 constructs | Enhanced nuclear import for efficient SOX9 editing in primary cells | Superior to terminally-fused NLS for RNP delivery [4] |

| Delivery Systems | Electroporation systems (e.g., Neon, Amaxa) | RNP delivery into primary immune cells | Optimize voltage and pulse duration for cell type |

| HDR Templates | Single-stranded DNA oligos (30-60nt arms) | Introducing precise mutations in SOX9 locus | Ideal for point mutations and small tags [12] |

| HDR Templates | Plasmid donors (200-500nt arms) | Larger insertions (e.g., fluorescent tags) | Required for inserts >200bp [12] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-SOX9 (specific epitopes) | Western blot, immunofluorescence | Validate specificity using SOX9-deficient controls |

| Cell Culture | Enhanced cytokine cocktails | Maintain viability of edited primary cells | Optimize for specific immune cell subtypes |

Structural and Functional Diagrams of SOX9

SOX9 Functional Domains and Interactions

Optimized CRISPR Workflow for SOX9

SOX9 in Immune Cells: Technical FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the documented role of SOX9 in T-cell differentiation and how can I study it?

SOX9 is involved in the lineage commitment of early thymic progenitors, influencing the balance between αβ and γδ T-cell differentiation. It cooperates with transcription factor c-Maf to activate Rorc and key Tγδ17 effector genes like Il17a and Blk [1].

- Experimental Protocol: In Vitro T-cell Differentiation and SOX9 Modulation

- Isolate Progenitors: Harvest early thymic progenitors from mouse models (e.g., C57BL/6).

- Modulate SOX9: Use CRISPR/dCas9 systems for overexpression (CRISPRa) or knockdown (CRISPRi). For knockout, use CRISPR/Cas9 with SOX9-targeting sgRNAs [3] [13].

- Differentiate Cells: Culture progenitors in conditions favoring αβ or γδ T-cell lineages. Use cytokine cocktails (e.g., IL-7 for γδ T cells).

- Analyze Outcomes:

- Flow Cytometry: Surface markers for αβ (TCRαβ) and γδ (TCRγδ) T cells.

- qPCR/RNA-Seq: Expression of

SOX9,Rorc,Il17a,Blk. - ChIP-Seq: Validate SOX9 binding at

Rorclocus [1].

FAQ 2: How does SOX9 influence macrophage function in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME), and what are the key pathways?

SOX9 expression in cancer cells is promoted by Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) via a TGF-β signaling axis. This SOX9 upregulation in turn drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), metastasis, and immune suppression [14].

- Key Signaling Pathway: TAMs secrete TGF-β → Activates C-jun and SMAD3 in cancer cells → Binds SOX9 promoter → Upregulates SOX9 expression → SOX9 drives EMT and tumor progression [14].

- Experimental Protocol: Investigating the TAM-SOX9 Axis

- Co-culture System: Co-culture TAMs (e.g., PMA-induced THP-1 macrophages) with cancer cell lines (e.g., A549, H1299).

- Inhibit Pathway: Use TGF-β receptor inhibitors or SOX9 RNAi in cancer cells.

- Functional Assays:

- Western Blot: Analyze SOX9, E-cadherin (epithelial marker), vimentin (mesenchymal marker).

- Transwell Assays: Measure cell migration and invasion.

- ELISA: Quantify TGF-β in supernatant [14].

FAQ 3: What is the oncogenic role of SOX9 in B-cell lymphomagenesis, specifically in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)?

SOX9 is overexpressed in IGH-BCL2+ DLBCL and functions as an oncogene. It drives cell proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, and promotes tumorigenesis by directly upregulating DHCR24, a key enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis [1] [15].

- Experimental Protocol: Targeting the SOX9-DHCR24 Axis in DLBCL

- Modulate SOX9: Silence SOX9 in DLBCL cells (e.g., using shRNA or CRISPRi).

- Rescue with DHCR24: Enforce DHCR24 expression in SOX9-knockdown cells.

- Phenotypic Assays:

- Cell Viability/Proliferation: MTT or colony formation assays.

- Cell Cycle Analysis: Flow cytometry for PI staining.

- Apoptosis Assay: Annexin V staining.

- In Vivo Validation: Use DLBCL xenograft models; measure tumor load and cholesterol content after SOX9 knockdown or cholesterol synthesis inhibition [15].

SOX9 Expression and Functional Data

Table 1: SOX9 Expression and Correlation with Immune Cells in Human Cancers

| Cancer Type | SOX9 Expression vs. Normal | Correlation with Immune Cell Infiltration | Prognostic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) [1] | Upregulated | - Negative correlation with B cells, resting mast cells, monocytes [1].- Positive correlation with neutrophils, macrophages, activated mast cells [1]. | SOX9 is a characteristic gene for early and late diagnosis [1]. |

| Pan-cancers (e.g., LUAD, LIHC) [16] | Significantly increased in 15 cancer types | In thymoma, negatively correlated with genes in PD-L1 and T-cell receptor signaling pathways [16]. | High SOX9 correlates with worse Overall Survival in LGG, CESC, THYM [16]. |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) [14] | Upregulated | Density of TAMs (CD163+) positively correlates with SOX9 expression in tumor cells [14]. | High co-expression of CD163 and SOX9 indicates shorter OS and DFS [14]. |

| Ovarian Cancer (HGSOC) [13] | Chemotherapy-induced | Associated with a stem-like, chemoresistant state [13]. | Top quartile of SOX9 expression has shorter overall survival after platinum treatment [13]. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SOX9 Research in Immune Cells

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems (VP64/KRAB) [3] | Precise transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) or repression (CRISPRi) of SOX9. | Enhancing chondrogenic potential in MSCs by Sox9 activation; studying gene function without permanent knockout [3]. |

| TGF-β Receptor Inhibitor [14] | Inhibits TGF-β signaling upstream of SOX9. | Blocking TAM-induced SOX9 upregulation and EMT in lung cancer cell co-cultures [14]. |

| Cordycepin (CD) [16] | Small molecule inhibitor of SOX9 expression. | Dose-dependent downregulation of SOX9 mRNA and protein in prostate and lung cancer cells [16]. |

| DHCR24 Inhibitors [15] | Targets the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway downstream of SOX9. | Inhibiting tumorigenesis in SOX9-high DLBCL xenograft models [15]. |

This table lists key materials and tools used in contemporary SOX9 immune cell research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SOX9 Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems (VP64/KRAB) [3] | Precise transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) or repression (CRISPRi) of SOX9. | Enhancing chondrogenic potential in MSCs by Sox9 activation; studying gene function without permanent knockout [3]. |

| TGF-β Receptor Inhibitor [14] | Inhibits TGF-β signaling upstream of SOX9. | Blocking TAM-induced SOX9 upregulation and EMT in lung cancer cell co-cultures [14]. |

| Cordycepin (CD) [16] | Small molecule inhibitor of SOX9 expression. | Dose-dependent downregulation of SOX9 mRNA and protein in prostate and lung cancer cells [16]. |

| DHCR24 Inhibitors [15] | Targets the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway downstream of SOX9. | Inhibiting tumorigenesis in SOX9-high DLBCL xenograft models [15]. |

SOX9 Signaling and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: SOX9's role in T-cells, macrophages, and B-cells involves distinct pathways. In macrophages, TGF-β signaling drives SOX9 upregulation, promoting cancer progression. In B-cells, SOX9 directly activates cholesterol synthesis. In T-cells, SOX9 influences lineage commitment.

Diagram 2: A general workflow for optimizing SOX9 editing efficiency in primary immune cells involves careful gRNA design, tool selection, and thorough validation before functional analysis.

The transcription factor SOX9 (SRY-related HMG-box 9) is increasingly recognized as a pivotal regulator of the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly through its profound effects on immune cell infiltration and function. As a developmental transcription factor with roles in chondrogenesis, bone formation, and organ development, SOX9 is frequently dysregulated in various cancers [17] [18]. Recent evidence has established that SOX9 contributes to tumor progression not only through cell-autonomous mechanisms but also by creating an immunosuppressive TME that facilitates immune evasion [17] [1]. This technical resource addresses the practical experimental challenges of studying SOX9-immune interactions, with special emphasis on optimizing editing efficiency in primary immune cells—a critical requirement for advancing both basic research and therapeutic development.

SOX9 exhibits a complex "double-edged sword" nature in immunobiology, acting as a Janus-faced regulator with context-dependent functions [1]. In multiple cancer types, including lung adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, and glioblastoma, SOX9 expression correlates with suppressed anti-tumor immunity through mechanisms involving impaired immune cell infiltration and function [17] [19] [20]. This technical support center provides comprehensive troubleshooting guides and methodological frameworks to help researchers overcome the significant experimental challenges in this field, particularly the difficulty of achieving efficient gene editing in primary immune cells while maintaining cell viability and function.

Technical Background: SOX9 Mechanisms in Immune Regulation

Molecular Structure and Functional Domains

SOX9 protein contains several critically important functional domains that determine its activity in immune and cancer biology:

- Dimerization Domain (DIM): Located ahead of the HMG box, facilitates protein-protein interactions [1]

- HMG Box Domain: Evolutionarily conserved DNA-binding motif that recognizes specific DNA sequences (ATTGTT) and induces DNA bending [21] [22]

- Transcriptional Activation Domains: TAM (central) and TAC (C-terminal) domains that interact with cofactors to enhance transcriptional activity [1]

- PQA-Rich Domain: Proline/glutamine/alanine-rich region necessary for transcriptional activation [1]

Mutations in the HMG domain, such as F12L and H65Y, significantly impair DNA binding capacity, while C-terminal truncations diminish transactivation potential, providing molecular insights for experimental approaches targeting SOX9 function [22].

Key Mechanisms of SOX9-Mediated Immune Modulation

Table 1: SOX9-Mediated Effects on Immune Cell Populations in the TME

| Immune Cell Type | Effect of SOX9 Expression | Proposed Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ T Cells | Suppressed infiltration and function | Collagen-rich matrix formation; immune checkpoint regulation [17] | Flow cytometry, IHC in murine LUAD [17] |

| Natural Killer (NK) Cells | Inhibited activity | Altered chemokine signaling; microenvironment remodeling [17] [1] | Gene expression analysis in human LUAD [17] |

| Dendritic Cells | Reduced antigen presentation | Direct suppression of dendritic cell function [17] | Single-cell RNA sequencing validation [17] |

| Macrophages | Polarization toward M2 phenotype | Altered cytokine milieu; direct transcriptional regulation [1] | Bioinformatics analysis of human datasets [1] |

| B Cells | Reduced infiltration | Unknown mechanism | TCGA data analysis in colorectal cancer [1] |

SOX9-Mediated Immunosuppression in Tumor Microenvironment

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying SOX9-Immune Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Cas9, Cas12a, sgRNAs targeting SOX9 | Gene knockout in immune and tumor cells [21] | Delivery efficiency varies by immune cell type; requires optimization |

| Viral Delivery Vectors | Adenoviruses, AAVs, Lentiviruses | Stable gene expression in primary cells [21] | AAVs have limited packaging capacity; lentiviruses offer higher efficiency |

| Non-Viral Delivery | Lipid nanoparticles, Gold nanoparticles, Electroporation | CRISPR RNP delivery to immune cells [21] | Reduced immunogenicity; suitable for primary immune cell editing |

| Cell Culture Models | 3D tumor organoids, Air-liquid interface systems | Mimicking tumor-immune interactions [17] | Preserves native tissue architecture and signaling |

| Animal Models | KrasG12D; Sox9flox/flox GEMM, Syngeneic grafts | In vivo validation of SOX9-immune axis [17] | GEMMs provide native tumor progression; syngeneic enables immune studies |

| Analysis Tools | CUT&RUN, ATAC-seq, scRNA-seq, Hi-C | Epigenetic and transcriptional profiling [23] | Requires specialized bioinformatics expertise for data interpretation |

Optimizing SOX9 Editing in Primary Immune Cells: Protocols & Workflows

CRISPR-Cas Workflow for Primary Immune Cell Editing

CRISPR-Cas Workflow for Primary Immune Cell Editing

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SOX9 Knockout in Primary T Cells

Materials Required:

- Human primary T cells from healthy donors

- Cas9 protein (commercial source)

- SOX9-targeting sgRNA (designed against HMG domain)

- Electroporation system (e.g., Neon Transfection System)

- RPMI-1640 complete medium with IL-2 (100 U/mL)

- Flow cytometry antibodies for validation

Step-by-Step Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Preparation: Design three sgRNAs targeting critical exons of SOX9, particularly in the HMG domain essential for DNA binding. Validate cutting efficiency in immortalized cell lines before primary cell experiments [21] [22].

RNP Complex Formation: Complex 10μg of Cas9 protein with 5μg of sgRNA at room temperature for 10-15 minutes to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. This approach reduces off-target effects compared to plasmid-based delivery [21].

Primary T Cell Activation: Activate isolated T cells using anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 48 hours to enhance CRISPR editing efficiency. Cell cycle status significantly impacts editing success.

Electroporation Parameters: Use optimized electroporation conditions—typically 1600V for 20ms with 1 pulse for T cells. Adjust parameters based on cell type and viability outcomes.

Post-Editing Recovery: Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed complete medium with IL-2. Allow 48-72 hours for protein turnover before assessing editing efficiency.

Validation Methods: Assess editing efficiency via T7E1 assay or next-generation sequencing. Confirm SOX9 knockout at protein level by Western blot and functional consequences through DNA binding assays [22].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is SOX9 editing efficiency low in primary macrophages compared to tumor cell lines? A1: Primary macrophages present unique challenges including lower proliferation rates and robust DNA repair mechanisms. Consider using Cas12a which may have better efficiency in certain primary cells, and optimize pre-stimulation protocols with GM-CSF or M-CSF to enhance editing receptivity [21].

Q2: How can I validate the functional consequences of SOX9 knockout in immune cells? A2: Beyond standard molecular validation, assess functional parameters including migration toward tumor conditioned medium, cytokine production profiles, and expression of immune checkpoint markers. Co-culture with tumor organoids provides a physiologically relevant functional assay [17].

Q3: What are the best controls for SOX9 immune editing experiments? A3: Include both non-targeting sgRNA controls and targeting controls against genes with known immune functions. Consider using the A19V SOX9 mutant which maintains DNA binding capacity as a specificity control for certain functional assays [22].

Q4: How does SOX9 affect different immune cell populations in the TME? A4: SOX9 predominantly suppresses anti-tumor immunity by reducing infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells while potentially promoting immunosuppressive populations. The exact effects are context-dependent and vary across cancer types [17] [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting SOX9 Editing in Immune Cells

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | Poor sgRNA design; suboptimal delivery; low cell viability | Test multiple sgRNAs; optimize RNP concentration; adjust electroporation parameters | Validate sgRNAs in easy-to-edit cell lines first; titrate delivery conditions |

| High cell death post-editing | Electroporation toxicity; excessive RNP concentration | Reduce voltage/pulse duration; use lower RNP amounts; implement recovery protocols | Include viability-enhanced media; optimize cell density during delivery |

| Inconsistent results between donors | Donor-specific genetic variations; differing immune cell states | Increase donor sample size; standardize activation protocols; include internal controls | Pre-screen donors for SOX9 expression; use standardized isolation methods |

| Functional effects not observed | Incomplete knockout; protein persistence; compensatory mechanisms | Use multiple sgRNAs; allow sufficient time for protein turnover; assess SOX8 compensation | Implement dual validation methods; consider inducible knockout systems |

| Off-target effects | sgRNA specificity issues; excessive Cas9 activity | Use computational sgRNA design tools; employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants; utilize RNP delivery | Perform whole-genome sequencing; include proper controls; use minimal effective Cas9 concentration |

Advanced Methodologies: Assessing SOX9-Immune Interactions

Comprehensive Analysis Workflow

Comprehensive SOX9-Immune Interaction Analysis Workflow

Specialized Techniques for SOX9-Immune Research

Chromatin Conformation Analysis: Hi-C data reveals that SOX9 resides within a ~1.87 Mb TAD on chromosome 17q24.3, with tissue-specific subdomains correlating with its regulatory elements. This architectural organization significantly impacts SOX9 expression and function in different immune contexts [18].

Single-Cell Multiomics: Combine scRNA-seq with surface protein expression to comprehensively map SOX9 effects across immune cell populations. This approach identified the correlation between SOX9 expression and reduced CD8+ T cell infiltration in lung adenocarcinoma [17].

Spatial Transcriptomics: Map SOX9 expression patterns within tissue architecture to understand geographical relationships between SOX9+ tumor cells and immune populations. This technique revealed the "immune desert" phenomenon in SOX9-high prostate cancer regions [1].

The intricate relationship between SOX9 and immune cell infiltration represents a promising frontier in cancer research with significant therapeutic implications. The technical frameworks and troubleshooting guides provided here address the most pressing experimental challenges in this field, particularly the optimization of SOX9 editing in primary immune cells. As research advances, targeting the SOX9-immune axis may yield novel therapeutic opportunities for overcoming immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. The continued refinement of gene editing approaches in primary immune cells will be essential for both understanding fundamental biology and developing next-generation immunotherapies that reverse SOX9-mediated immunosuppression.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the role of SOX9 in immune cells? SOX9 is a transcription factor that plays a significant role in immune cell development and function. It participates in the differentiation and regulation of diverse immune lineages. For T-cell development, SOX9 can cooperate with c-Maf to activate Rorc and key Tγδ17 effector genes (Il17a and Blk), modulating the lineage commitment of early thymic progenients and influencing the balance between αβ T-cell and γδ T-cell differentiation [1]. While it does not have a well-defined major role in normal B-cell development, SOX9 is overexpressed in certain B-cell lymphomas, where it acts as an oncogene by promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis [1].

How does SOX9 expression correlate with immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment? The expression of SOX9 is strongly linked to the composition of immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, a relationship that varies by cancer type. The table below summarizes key correlations identified through bioinformatics analyses.

| Cancer Type | Positive Correlation With | Negative Correlation With |

|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | Neutrophils, Macrophages, Activated Mast cells, Naive/Activated T cells [1] | B cells, Resting Mast cells, Resting T cells, Monocytes, Plasma cells, Eosinophils [1] |

| General Pan-Cancer Analysis | Memory CD4+ T cells [1] | CD8+ T cell function, NK cell function, M1 Macrophages [1] |

| Prostate Cancer (PCa) | Tregs, M2 macrophages (TAM Macro-2), Anergic neutrophils [1] | CD8+ CXCR6+ T cells, Activated neutrophils [1] |

Why is optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency critical for SOX9 research in primary immune cells? Primary immune cells are notoriously difficult to transfect and edit. Optimizing editing efficiency is essential because:

- Therapeutic Relevance: High editing efficiency via a low, transient enzyme dose is a primary goal for therapeutic applications to minimize off-target effects and immune responses [4].

- RNP Transience: When using ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for delivery—a preferred method for therapeutic use due to its transient nature—the Cas9 enzyme has a short 1-2 day half-life. The enzyme must localize to the nucleus rapidly to induce editing before it is degraded by the cell [4].

What are common issues affecting PCR/qPCR when validating SOX9 expression? When benchmarking SOX9 expression levels using qPCR, the following issues related to plastic consumables can arise [24]:

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| No or low amplification | Suboptimal fit to the thermal cycler's block; suboptimal plate construction. | Use plates verified for compatibility with your thermal cycler. Select plates with uniform, thin-wall polypropylene wells for optimal thermal conductivity. |

| Low qPCR signal | Signal loss through clear well walls. | Use plates with white wells to reduce signal refraction and enhance fluorescence reflection to the detector. |

| Variable qPCR data | Well-to-well variation (crosstalk). | Use plates with white wells to prevent optical crosstalk between adjacent wells. |

| False positive results | Presence of DNA contaminants on seals; improper sealing leading to cross-contamination. | Request a manufacturer's Certificate of Analysis confirming the absence of human DNA. Use seals treated to destroy contaminants (e.g., ethylene oxide for ISO 18385). Ensure all wells are properly sealed. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Low CRISPR Editing Efficiency in Primary Human Lymphocytes

Problem: Low knockout rates when editing the SOX9 gene in primary human T cells.

Solution: Enhance nuclear delivery of the Cas9 enzyme. A proven strategy is to optimize the nuclear localization signals (NLS) within the Cas9 construct. The traditional method uses terminally fused NLS sequences. A more advanced approach uses hairpin internal nuclear localization signals (hiNLS) installed at selected sites within the backbone of CRISPR-Cas9 [4].

- Procedure:

- Utilize hiNLS Cas9 constructs: These constructs increase NLS density without compromising protein yield.

- Delivery Method: Deliver the editing machinery as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex via electroporation.

- Validation: This method has been shown to enhance the knockout efficiency of genes like B2M and TRAC in primary human T cells, which is a robust proxy for assessing editing capability [4].

- Mechanism: The hiNLS strategy facilitates more efficient and rapid import of the Cas9 RNP complex into the nucleus. This is critical in primary cells where the RNP has a short half-life and must reach the nucleus quickly to perform editing before degradation [4].

Guide 2: Inconsistent SOX9 Expression Data in Immune Cell Subsets

Problem: High variability in SOX9 expression measurements across different samples or immune cell isolations.

Solution: Standardize cell sorting and analysis protocols to account for heterogeneity.

- Procedure:

- Rigorous Cell Sorting: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate highly pure populations of target immune cell subsets (e.g., T cells, B cells, monocytes). Rely on multiple surface markers for precise identification [25].

- Quality Control: Post-sorting, perform stringent quality control. This includes determining cell viability (e.g., using 7AAD staining) and establishing quality metrics for sequencing libraries, such as median gene and unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts [25].

- Single-Cell Resolution: For the most precise benchmarking, consider using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). This technology can quantify SOX9 expression and reveal its heterogeneity within and between immune cell subsets, which bulk RNA-seq might average out [25].

Guide 3: Differentiating Direct vs. Indirect SOX9 Effects in Functional Assays

Problem: Difficulty in determining whether an observed phenotypic change in immune cells is due to direct regulation by SOX9 or an indirect downstream effect.

Solution: Combine precise TF modulation with chromatin accessibility assays.

- Procedure:

- Precise SOX9 Titration: Use a system that allows for tunable modulation of SOX9 protein levels (e.g., the dTAG degradation system) in your cellular model [26]. This allows you to study effects across a range of physiologically relevant dosages, rather than a complete knockout.

- Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq): Perform ATAC-seq on cells with titrated SOX9 levels to map changes in chromatin accessibility.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify SOX9-dependent regulatory elements (REs) whose accessibility changes with SOX9 dosage.

- Note that most REs are buffered against small dosage changes, but REs that are directly and primarily regulated by SOX9 show heightened sensitivity [26].

- Correlate the sensitivity of these REs with changes in the expression of nearby genes. Genes involved in key functions like chondrogenesis are often linked to these sensitive REs [26]. This integrated approach helps pinpoint the most direct targets of SOX9.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| hiNLS Cas9 Constructs | CRISPR-Cas9 variants with hairpin internal Nuclear Localization Signals for enhanced nuclear import and editing efficiency in primary human lymphocytes [4]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. The preferred method for transient, high-efficiency delivery with reduced off-target effects and immune response risk [4]. |

| dTAG Degradation System | A chemical biology tool that allows for rapid and precise degradation of a target protein (e.g., SOX9). Enables the study of TF dosage effects at physiologically relevant levels [26]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | A high-resolution transcriptomics technology used to profile SOX9 expression and heterogeneity across individual cells within complex populations like primary immune cell subsets [25]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Molecular profiling technique that maps gene expression data (including SOX9) onto tissue architecture, revealing the spatial context of immune-stromal-tumor interactions [25]. |

| Cordycepin (CD) | An adenosine analog that has been shown to inhibit both mRNA and protein expression of SOX9 in a dose-dependent manner in various cancer cell lines, indicating its potential as a research tool for modulating SOX9 [16]. |

Advanced Delivery and CRISPR Toolkits for Efficient SOX9 Manipulation

Editing genes in primary immune cells presents unique challenges, including low transfection efficiency and sensitivity to DNA damage. When the research goal involves a key transcription factor like SOX9—crucial for cell fate and differentiation—choosing the right CRISPR tool is paramount. This guide compares three primary CRISPR systems: the traditional Cas9 nuclease, transcriptional modulators using dCas9 (CRISPRa/i), and Base Editors. The following FAQs and structured data will help you select and optimize the right system for your work on SOX9 in primary immune cells.

CRISPR System Comparison Tables

The table below summarizes the core mechanisms and primary applications of the three main CRISPR systems to inform your initial choice.

| CRISPR System | Core Mechanism | Primary Application in SOX9 Research | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks (DSBs), repaired by NHEJ or HDR [27]. | Complete gene knockout to study loss-of-function. | Permanent disruption of SOX9 gene function. |

| dCas9 Modulators (CRISPRi/a) | Catalytically dead Cas9 fused to effectors blocks or recruits transcription machinery [27] [28]. | Precise up/down-regulation of SOX9 expression without altering DNA sequence. | Reversible transcriptional silencing (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa). |

| Base Editors | Cas9 nickase fused to a deaminase enzyme directly converts one base pair to another [29]. | Introduction of specific point mutations to study SOX9 structure-function or model SNPs. | Single nucleotide change without inducing DSBs. |

This second table outlines critical experimental considerations for deploying these systems in hard-to-transfect primary immune cells.

| CRISPR System | Delivery Considerations | Key Design Factor | Best for SOX9 When You Need: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Viral vectors (e.g., Lentivirus, AAV); Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) for reduced off-targets & toxicity [21]. | sgRNA design targeting early exons; control sample to identify background variants [30]. | To completely abolish protein function and study the resulting phenotype. |

| dCas9 Modulators (CRISPRi/a) | Efficient delivery of the larger dCas9-effector fusion is crucial; consider lentivirus [28]. | sgRNA must target the promoter or transcriptional start site (TSS) of SOX9 [28]. | To study the effects of graded, reversible changes in SOX9 expression levels. |

| Base Editors | Requires careful optimization of delivery to maintain high efficiency while minimizing indel byproducts. | The target base must be located within the editing window of the base editor [29]. | To model a specific disease-associated single nucleotide variant or disrupt a functional domain precisely. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do I choose between permanently knocking out SOX9 versus transiently knocking it down?

The choice depends on your biological question and the nature of your cells.

- Use Cas9 Nuclease for a permanent knockout: This is ideal if you are studying long-term effects in a cell population that can tolerate a double-strand break and the complete, irreversible loss of SOX9 function. This is common in proliferation or survival screens [31].

- Use CRISPRi for a reversible knockdown: This is superior for studying essential genes where a permanent knockout would be lethal to your primary immune cells. It allows for partial, tunable repression without damaging the DNA, which can better mimic the action of therapeutic drugs [28].

Why do different sgRNAs designed for the same SOX9 target show variable efficiency?

It is common for different sgRNAs targeting the same gene to exhibit substantial variability in editing efficiency [31]. This is due to:

- Chromatin Accessibility: The target region in the SOX9 promoter or gene body may be packed tightly (heterochromatin) or loosely (euchromatin).

- sgRNA Sequence Properties: The specific nucleotide composition and potential secondary structure of the sgRNA itself can affect its stability and binding affinity.

- Mitigation Strategy: Always design and test 3-4 sgRNAs per target. For CRISPRa/i, ensure your sgRNAs are designed to bind the promoter region or transcriptional start site of SOX9, as binding elsewhere will be ineffective [28].

What is the recommended sequencing depth for analyzing a CRISPR screen on SOX9-edited immune cells?

For a genome-wide CRISPR screen, a sequencing depth of at least 200x coverage per sample is generally recommended [31]. The required data volume can be estimated with the formula: Required Data Volume = Sequencing Depth × Library Coverage × Number of sgRNAs / Mapping Rate. Sufficient depth is critical for distinguishing true hits from noise in your screen.

How can I detect and validate CRISPR-editing events at the SOX9 locus specifically?

For accurate detection of editing events, especially from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data, use specialized bioinformatic tools like CRISPR-detector [30]. This tool is critical because it:

- Performs co-analysis of treated and control samples to subtract pre-existing background variants.

- Provides integrated structural variation calling and functional annotations of editing-induced mutations.

- Offers improved accuracy through haplotype-based variant calling to handle sequencing errors.

Essential Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Core Mechanism and Experimental Application Workflow

Diagram 2: SOX9 Editing Project Pathway for Immune Cells

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below lists essential materials and reagents you will need to execute a SOX9 editing project in primary immune cells.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes for Primary Immune Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic sgRNA | Guides the CRISPR complex to the target SOX9 locus. | Chemically synthesized sgRNA is recommended over plasmid-based versions for higher efficiency and lower off-target effects [28]. |

| Cas9, dCas9, or Base Editor | The effector protein that executes the edit. | For Cas9, the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is preferred to reduce toxicity and off-target effects. For dCas9, ensure it is fused to the appropriate activator/repressor domain (e.g., KRAB for CRISPRi) [28]. |

| Delivery Vehicle (e.g., Lentivirus, Electroporation System) | Introduces CRISPR components into cells. | Electroporation of RNPs is highly effective for many immune cell types. Lentivirus can be used for dCas9-effector fusions and for hard-to-transfect cells [21]. |

| CRISPR Library | For genome-wide or focused screens. | A custom, hypothesis-driven library targeting SOX9 and its known interactors can be more efficient than a genome-wide one [32]. |

| Validation Tool (e.g., CRISPR-detector) | Bioinformatics software for detecting on- and off-target edits. | Essential for confirming edits, especially in WGS data. Tools like CRISPR-detector provide functional annotation of mutations [30]. |

| Positive Control sgRNA | A validated sgRNA to confirm system functionality. | Crucial for troubleshooting. If your positive control fails to show the expected enrichment or depletion, the screening conditions may need optimization [31]. |

For researchers aiming to optimize SOX9 editing efficiency in primary immune cells, selecting the appropriate delivery vehicle is a critical experimental decision. This technical support center provides a comparative analysis and troubleshooting guide for the three predominant delivery systems: Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAV), Lentiviruses (LV), and non-viral methods like Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) electroporation. The choice among these impacts everything from editing persistence and cargo capacity to cell viability and safety profile, making a thorough understanding essential for success in gene therapy and drug development workflows.

Delivery Vehicle Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each delivery vehicle to guide your initial selection for SOX9 editing projects.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Gene Delivery Vehicles

| Feature | AAV (Adeno-Associated Virus) | Lentivirus (LV) | Non-Viral (RNP Electroporation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | In vivo gene delivery [33] | Ex vivo gene correction (e.g., in T cells, HSCs) [33] [34] | Ex vivo gene editing (e.g., CAR-T, primary immune cells) [35] [34] |

| Payload Type | DNA (ssAAV or dsAAV) | RNA (reverse transcribed to DNA) | Pre-assembled CRISPR-Cas9 Protein + gRNA (RNP complex) [36] |

| Genomic Integration | Non-integrating (episomal) | Integrating (into host genome) | Non-integrating (transient activity) |

| Cargo Capacity | ~4.4 kb [37] [38] | ~10 kb [34] | Limited primarily by RNP complex size and electroporation efficiency |

| Editing Persistence | Long-term expression in non-dividing cells [37] | Long-term, stable expression due to integration [33] | Transient (reduces off-target risk) |

| Typical Transduction Efficiency in Immune Cells | Varies by serotype; can be high | High | High, but dependent on cell health and electroporation optimization |

| Key Safety Considerations | Low immunogenicity; low risk of insertional mutagenesis [33] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis; immunogenicity concerns [33] [34] | No viral vector-related risks; potential for cell toxicity from electroporation [35] |

| Relative Cost & Manufacturing | Moderate to high; scalable production available [33] | Moderate to high; complex production [33] | Lower cost; simpler manufacturing of RNP components [34] |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQs and Troubleshooting for AAV

Q1: What is a major limitation when using AAV for gene editing, and how can it be mitigated? The primary limitation is its small cargo capacity of approximately 4.4 kb [37] [38]. For SOX9 editing, this can be challenging as the human SOX9 coding sequence itself is about 1.7 kb, leaving limited space for promoters, regulatory elements, or complex editing machinery. Mitigation strategies include using compact promoters or exploring dual-AAV systems, though the latter reduces overall efficiency.

Q2: My AAV transduction efficiency in primary immune cells is low. What could be the cause? Low efficiency can stem from several factors:

- Incorrect Serotype: AAV serotypes have distinct tissue tropisms. AAV2 has broad infectivity but may not be optimal for all immune cell types. Testing serotypes like AAV5 or AAV6 in a pilot study is recommended [37].

- Low Titer/Improper Dosing: Confirm the viral titer and ensure an adequate dose. For in vivo work in mice, doses typically range from 10^11 to 10^12 vector genomes (vg) per animal [37].

- Impure Preparation: Empty capsids (particles without the genome) can compete for cell binding. Use purified AAV preparations to ensure a high percentage of genomic particles [33].

FAQs and Troubleshooting for Lentivirus

Q1: I am concerned about the safety of lentiviral vectors. How have these risks been addressed? Modern lentiviral vectors are self-inactivating (SIN) and derived from HIV-1, with key pathogenic genes removed. Compared to their gamma-retroviral predecessors, they exhibit a safer integration profile with a reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis [33] [34]. However, the risk is not zero, and this remains a key consideration for clinical applications.

Q2: I am not getting high lentiviral transduction efficiency in my primary T cells. What should I check?

- Transduction Enhancers: Ensure you are using a transduction enhancer like Polybrene reagent [39].

- Cell Health and Status: Use healthy, actively dividing cells. Lentiviruses can transduce non-dividing cells, but proliferation often improves outcomes.

- Multiplicity of Infection (MOI): Titrate the virus. Using too low an MOI will result in low efficiency. Start with a range of MOIs to find the optimum for your cell type [39].

- Viral Titer and Quality: Low titer or improperly stored (multiple freeze-thaw cycles) virus will lead to poor performance. Always aliquot and store viral stocks at -80°C [39].

FAQs and Troubleshooting for RNP Electroporation

Q1: Electroporation is causing high cytotoxicity in my primary immune cells. How can I improve viability? High cell death is a common challenge with electroporation. Consider these approaches:

- Switch to Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Recent studies show that for mRNA delivery, LNPs can outperform electroporation by significantly prolonging CAR expression and functionality in T cells while causing less cytotoxicity and altered gene expression [35].

- Optimize Parameters: If using electroporation, systematically optimize pulse voltage, width, and buffer conditions. Research indicates that resuspending cells in optimized buffers (e.g., Buffer R for the Neon system) can improve viability [35].

- Use High-Quality RNPs: Ensure your Cas9 protein and sgRNA are pure and properly complexed. Chemically modified, extended sgRNAs have been shown to increase editing efficiency, potentially allowing for lower, less toxic doses [36].

Q2: The gene editing efficiency with my RNP complex is inconsistent. What can I do?

- RNP Quality and Delivery: Use a chemically modified sgRNA to enhance stability and efficiency. One study using an extended, GC-rich, chemically modified sgRNA achieved biallelic editing and near-complete germline transmission of a Sox9 edited allele in zebrafish [36].

- Validate Your RNP: Check the activity of your RNP complex in an easy-to-transfect cell line before moving to primary cells.

- Confirm Delivery: Use a fluorescently labeled tracer RNA or protein to confirm successful delivery into the cells during electroporation.

Essential Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision-making pathway for selecting a delivery vehicle based on your experimental goals for SOX9 research.

Diagram 1: Decision pathway for delivery vehicle selection.

The diagram below outlines the general mechanism of how SOX9, as a transcription factor, regulates gene expression. Disrupting this pathway is the goal of SOX9 editing strategies.

Diagram 2: SOX9 transcriptional activation mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Delivery and Editing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HEK 293T Cell Line | Production of high-titer AAV and Lentiviral particles [37] [39]. | Highly transfectable; constitutively expresses SV40 large T antigen for high viral protein expression [37]. |

| Stbl3 E. coli | Cloning of lentiviral constructs [39]. | recA13 mutation minimizes unwanted recombination between LTR regions in the plasmid [39]. |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Transfection reagent for plasmid delivery into packaging cells during viral production [39]. | Can be toxic to cells; optimize DNA-to-reagent ratio and avoid antibiotics in the medium during transfection [39]. |

| Polybrene Reagent | A cationic polymer used to enhance viral transduction efficiency [39]. | Reduces electrostatic repulsion between viral particles and the cell membrane. Test for cell type sensitivity [39]. |

| AAVpro Purification Kit | Purifies AAV particles of any serotype from cell lysates [37]. | Fast (~4 hours) alternative to lengthy ultracentrifugation; suitable for in vivo studies [37]. |

| GenVoy-ILM LNP Kit | Formulating mRNA-loaded LNPs for non-viral delivery [35]. | Optimized for T cell transfection; delivery mechanism is ApoE4/LDL-R pathway dependent [35]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Component of the RNP complex for CRISPR editing [36]. | Enhanced stability and editing efficiency. Use extended, GC-rich versions for high-efficiency biallelic editing [36]. |

Protocol for High-Efficiency RNP Transfection into Hard-to-Edit Primary Human T Cells and Macrophages

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key advantage of using RNP transfection over other methods for primary immune cells? RNP (ribonucleoprotein) transfection involves delivering pre-complexed Cas9 protein and guide RNA directly into cells. This method leads to rapid genome editing with high efficiency and reduced off-target effects because the RNP complex degrades quickly after cutting the DNA. It is particularly beneficial for primary T cells and macrophages, which are sensitive to the prolonged nuclease expression common with DNA-based delivery methods [40].

Q2: My gene knockout efficiency in primary T cells is low. What is the most critical parameter to optimize? The molar ratio of sgRNA to Cas9 protein in the pre-formed RNP complex is critical. A common optimization is to use an excess of sgRNA. One study demonstrated that a 3:1 molar ratio of gRNA to Cas9 dramatically increased knockout efficiency compared to a 1:1 ratio, while a further increase provided no additional benefit [41].

Q3: How can I improve the viability of my primary cells after electroporation? Low viability can result from reagent toxicity or harsh electroporation conditions. To mitigate this:

- Optimize delivery parameters: Use electroporation protocols specifically optimized for your primary cell type [42].

- Use low-toxicity reagents: Consider novel systems like the PAGE (Peptide-Assisted Genome Editing) system, which uses a cell-penetrating Cas9 and an endosomal escape peptide, resulting in low cellular toxicity and minimal transcriptional perturbation [43].

- Ensure cell health: Use healthy, actively dividing cells and avoid over-confluency. High-quality, endotoxin-free nucleic acids and proteins are also crucial [44] [45].

Q4: I need to perform homology-directed repair (HDR) in primary T cells. What strategies can enhance knock-in efficiency? HDR is less efficient than non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) but can be improved with the following:

- Use of NHEJ inhibitors: Adding small molecules like M3814 can inhibit the competing NHEJ pathway and significantly promote HDR, enabling high efficiencies of biallelic knock-in [46] [42].

- Optimize HDR template design: Using smaller DNA templates (e.g., Nanoplasmids) and incorporating a Cas9 Target Sequence (CTS) within the template can improve HDR rates [42].

- Delivery method: Electroporation is a robust method for co-delivering RNP and HDR template DNA into primary T cells [42].

Troubleshooting Guide

The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and solutions to help you achieve high-efficiency editing.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Efficiency and High Toxicity in Primary Immune Cells

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Knockout Efficiency• Low protein loss by flow cytometry• Low indel frequency by sequencing | • Suboptimal RNP complex formation• Inefficient delivery into cells• Poor gRNA design or quality | • Titrate the sgRNA:Cas9 molar ratio (e.g., 3:1) during RNP complexing [41].• Use chemically modified, high-purity synthetic gRNAs.• Validate delivery efficiency (e.g., using a fluorescent tracer RNA) [41]. |

| Low HDR/Knock-in Efficiency• Low reporter expression• Poor biallelic integration | • NHEJ outcompetes HDR• Low HDR template concentration or poor design• Low RNP activity | • Add NHEJ inhibitors (e.g., M3814 at 2 µM) during editing [46] [42].• Increase HDR template concentration; use smaller plasmids (Nanoplasmids) and include a CTS [42].• Optimize the timing of HDR template delivery relative to RNP. |

| High Cell Mortality Post-Transfection• Significant cell death within 12-24 hours• Poor cell recovery and expansion | • Electroporation-induced toxicity• Excessive RNP or DNA concentration• Poor health of starting cell culture | • Use a gentler or optimized electroporation protocol (e.g., Lonza's 4D Nucleofector or MaxCyte's ExPERT with protocol ETC4) [41] [42].• Reduce the amount of RNP/DNA to the minimum required for efficient editing [44].• Ensure cells are isolated and cultured properly; use low-passage, high-viability cells. |

| High Variability Between Donors/Experiments• Inconsistent editing efficiency across biological replicates | • Donor-to-donor genetic variation• Inconsistent cell activation state• Slight variations in protocol | • Use a consistent and robust cell activation protocol (e.g., anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for T cells).• Include internal positive controls in every experiment.• Pre-optimize the protocol using cells from multiple donors to establish a robust workflow [42]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Efficiency RNP Electroporation for Primary Human T Cells

This protocol is adapted from established methods for achieving >90% knockout efficiency in primary T cells [41] [42].

Key Reagents:

- Cells: Activated human primary T cells (48-72 hours post-activation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28).

- RNP Complex: Recombinant Cas9 protein and target-specific synthetic crRNA/tracrRNA (with optional chemical modifications).

- Equipment: Electroporator (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector or MaxCyte ExPERT).

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Prepare RNP Complex:

- Resuspend crRNA and tracrRNA to a stock concentration of 160 µM in nuclease-free buffer.

- Mix crRNA and tracrRNA in a 1:1 ratio (e.g., 5 µL each) to form the gRNA duplex. Heat at 95°C for 5 minutes and cool to room temperature.

- Combine 10 µL of the 80 µM gRNA duplex with 10 µL of 40 µM Cas9 protein (e.g., from IDT or similar supplier). This gives a final 3:1 molar ratio of gRNA:Cas9.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the RNP complex.

Prepare Cells:

- Harvest activated T cells and wash with PBS. Count the cells and resuspend them in the appropriate electroporation buffer (e.g., Lonza's P3 buffer or MaxCyte's electroporation buffer) at a concentration of 10-20 million cells per 100 µL.

Electroporation:

- Add the pre-formed RNP complex (20 µL from step 1) to 100 µL of cell suspension. Mix gently.

- Transfer the entire mixture to a certified electroporation cuvette.

- Electroporate using a pre-optimized program. For T cells, programs like DN-100 on the Lonza 4D or ETC4 on the MaxCyte GTx are effective starting points [41] [42].

Post-Transfection Recovery:

- Immediately after electroporation, add pre-warmed culture medium to the cells.

- Transfer the cells to a culture plate and incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Assess editing efficiency and cell viability 48-72 hours post-transfection.

Protocol 2: Peptide-Assisted Genome Editing (PAGE) for Sensitive Primary Cells

For cells that are highly sensitive to electroporation, the PAGE system offers a gentle yet highly efficient alternative [43].

Key Reagents:

- Cell-Penetrating Cas9 (Cas9-CPP): Purified recombinant Cas9 fused with cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and nuclear localization signals (NLS), such as TAT-4xNLS-Cas9-2xNLS-sfGFP (Cas9-T6N).

- Assist Peptide (AP): TAT-HA2 peptide, a fusion of a CPP (TAT) and an endosomal escape peptide (HA2).

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Prepare PAGE Components:

- Pre-complex the Cas9-CPP (e.g., Cas9-T6N) with the target-specific sgRNA to form RNP as in Protocol 1.

- Prepare a stock solution of the TAT-HA2 assist peptide.

Incubate Cells with PAGE:

- Resuspend primary cells (e.g., T cells or macrophages) in serum-free medium.

- Add the pre-formed Cas9-CPP RNP complex to the cells at a final concentration of 0.5 µM.

- Add the TAT-HA2 peptide to the cell mixture.

- Incubate the cells for 30 minutes at 37°C.

Remove Surface-Bound Complexes and Culture:

- After incubation, treat cells with trypsin to remove surface-bound protein.

- Wash the cells and resuspend them in complete culture medium.

- Continue culturing and analyze editing efficiency after 3-4 days. This method has been shown to achieve >80% editing in primary human T cells with minimal toxicity [43].

Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for High-Efficiency RNP Transfection

| Reagent | Function & Role in Optimization | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Increases stability and reduces innate immune response; critical for high efficiency in primary cells. | Synthetic crRNA and tracrRNA with phosphorothioate bonds [41]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitor (M3814) | Enhances HDR efficiency by suppressing the competing NHEJ DNA repair pathway, crucial for knock-in experiments. | M3814 (DNA-PKcs inhibitor) [46] [42]. |

| Cell-Penetrating & Endosomal Escape Peptides | Enables efficient delivery of RNP without electroporation, minimizing cellular toxicity. | TAT-HA2 peptide [43]. |

| Optimized Electroporation Buffers & Kits | Specialized formulations that maintain cell viability while enabling efficient molecular delivery during electrical pulses. | Lonza P3 Kit [41], MaxCyte Electroporation Buffer [42]. |

| HDR Template with Cas9 Target Site (CTS) | A DNA repair template designed with a Cas9 cut site to protect the integrated sequence from repeated cleavage, boosting HDR yields. | Nanoplasmid HDR templates with CTS [42]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Optimized RNP Electroporation Workflow for Primary T Cells

Diagram 2: Mechanism of the PAGE Delivery System

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the therapeutic goal of simultaneously activating SOX9 and inhibiting the NF-κB pathway in osteoarthritis? The goal is to enhance cell-based therapies for osteoarthritis (OA). SOX9 is the master regulator of chondrogenesis (cartilage formation), while the NF-κB pathway drives destructive inflammation in joints. By using CRISPR-dCas9 to simultaneously upregulate SOX9 and inhibit RelA (a key subunit of NF-κB), researchers can engineer mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) with enhanced cartilage-forming potential and reduced inflammatory response. This dual modification significantly attenuated cartilage degradation and relieved pain in a mouse model of OA [3] [47].

Q2: Why use CRISPR-dCas9 instead of traditional CRISPR-Cas9 for this application? CRISPR-dCas9 uses a "dead" Cas9 that lacks DNA-cutting ability but can still be targeted to specific DNA sequences. This allows for fine-tuned transcriptional regulation (CRISPRa for activation, CRISPRi for interference) without making permanent, potentially deleterious changes to the DNA. This is ideal for precisely modulating gene expression to desired levels, such as boosting SOX9 or dampening RelA, to enhance cellular functions for therapy [3] [27].

Q3: My gene activation or repression efficiency is low. What are the primary factors I should check? Low efficiency in CRISPR-dCas9 experiments can stem from several common issues [48] [49]:

- sgRNA Design: The guide RNA may be suboptimal. Verify its specificity and efficiency using bioinformatics tools.

- Delivery Efficiency: The CRISPR components may not be efficiently delivered into your target cells. Optimize your transfection method (e.g., electroporation, viral vectors) for your specific cell type, especially for challenging primary immune cells [12].

- Component Concentration: The concentration of the sgRNA and dCas9-effector fusion proteins may be too low. Verify concentrations and ensure an appropriate ratio is being delivered [50].

- Expression Levels: Confirm that the promoters driving dCas9 and sgRNA expression are active in your target cells.

Q4: How can I minimize off-target effects in my dCas9 experiments? While dCas9 doesn't cut DNA, it can still bind to off-target sites, potentially causing unintended gene regulation. Key strategies to minimize this include [51] [27]:

- Careful sgRNA Design: Use highly specific sgRNAs with minimal similarity to other genomic sequences, aided by computational prediction tools.

- Use of High-Fidelity Variants: Consider using high-fidelity dCas9 variants engineered for improved specificity.

- Optimal Delivery: Using preassembled Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) can reduce off-target effects compared to plasmid-based delivery [50].

- Control Expression: Finely tune the expression level and duration of dCas9-sgRNA complexes to minimize prolonged binding.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low Knock-in or HDR Efficiency in Primary Cells

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: The cell's repair machinery favors NHEJ over HDR.

- Solution: Primary cells, particularly quiescent ones like some immune cells, heavily favor the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) repair pathway over the precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) needed for knock-ins. Consider using small molecule inhibitors of NHEJ key proteins to temporarily shift the balance toward HDR [12].

- Cause 2: Suboptimal HDR template design.

- Solution: Optimize your Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) template design. For short insertions (e.g., tags, point mutations), use single-stranded DNA oligos with homology arms of 30-60 nucleotides. For larger insertions (e.g., fluorescent proteins), use double-stranded DNA templates (like plasmids) with longer homology arms (200-500 nucleotides) [12].

- Cause 3: Low transfection efficiency and cell viability.

- Solution: Primary human B cells and other immune cells can be difficult to transfect. Electroporation is often the most effective method. Systematically optimize voltage and pulse parameters to maximize delivery while maintaining high cell viability. Using modified, chemically synthesized sgRNAs can also improve stability and reduce toxicity [50] [12].

Problem: Inconsistent SOX9 Activation Phenotypes

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Epigenetic barriers and chromatin state.

- Solution: SOX9 is a pioneer factor that can bind closed chromatin, but its efficiency can be context-dependent [23]. Ensure your sgRNAs are designed to target regions accessible within your specific cell type's chromatin landscape. Using multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene can also help achieve more robust and consistent activation [50].

- Cause 2: Inefficient delivery of the multi-component system.

- Solution: The system requires simultaneous delivery of dCas9 fused to an activator (like VP64) and the sgRNA targeting the SOX9 promoter. Low co-delivery efficiency will result in a mosaic population. Using a single vector system or the RNP delivery method can ensure all components are present in the same cell [3] [50].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Simultaneous Sox9 Activation and RelA Inhibition

The following protocol is adapted from the study that successfully engineered MSCs for osteoarthritis therapy [3].

1. Vector Construction

- CRISPRa for SOX9: Construct a lentiviral vector expressing a fusion protein of dSpCas9 (a Streptococcus pyogenes dCas9 mutant) and the transcriptional activation domain VP64.

- CRISPRi for RelA: Construct a second lentiviral vector expressing a fusion of dSaCas9 (a Staphylococcus aureus dCas9 mutant) and the transcriptional repression domain KRAB.

- Dual-gRNA Vector: Construct a lentiviral vector (e.g., Lenti-EGFP-dual-gRNA) expressing two sgRNA scaffolds: one for SpCas9 targeting the SOX9 promoter, and one for SaCas9 targeting the RelA promoter.

2. sgRNA Design and Screening

- Design 4-5 sgRNAs for each target gene (SOX9 and RelA) using established bioinformatics tools.

- The table below lists the effective sgRNA sequences and their genomic positions from the cited study [3].

Table: Effective sgRNA Sequences for SOX9 Activation and RelA Inhibition

| Target Gene | sgRNA Name | Guide Sequence (5' to 3') | PAM | Position Relative to TSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOX9 | Sox9-2 | CGGGTTGGGTGACGAGACAGG |

AGG | -167 |

| SOX9 | Sox9-3 | ACTTACACACTCGGACGTCCC |

GGG | -276 |

| SOX9 | Sox9-4 | TGGACCGGATTTTGGAAGGG |

GGG | -124 |

| RelA | RelA-1 | CCGAAATCCCCTAAAAACAGA |

GTGAGT | -41 |

| RelA | RelA-2 | TGATGTGTTGCGTCCTCCGGC |

CAGAGT | -628 |

| RelA | RelA-3 | TGCTCCCGCGGAGGCCAGTGA |

CTGAAT | -189 |

3. Cell Culture and Viral Transduction

- Culture target cells (e.g., bone marrow-derived MSCs or primary immune cells) in standard growth medium.

- Co-transduce cells with the three lentiviral constructs (dSpCas9-VP64, dSaCas9-KRAB, and the dual-gRNA vector) at an appropriate Multiplicity of Infection (MOI). Include controls (unmodified cells, cells with non-targeting gRNA).

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate successfully transduced cells based on a reporter gene (e.g., EGFP).

4. Validation of Gene Modulation

- Molecular Validation:

- qRT-PCR: Measure mRNA expression levels of SOX9, RelA, and downstream target genes (e.g., chondrogenic markers like ACAN for SOX9; inflammatory genes like NFKBIA for NF-κB).

- Western Blot: Confirm changes in SOX9 and RelA protein levels.

- Functional Validation:

- Chondrogenic Differentiation Assay: Culture transduced MSCs in chondrogenic differentiation medium. Assess cartilage matrix formation using Alcian Blue or Safranin O staining.

- Immunomodulatory Assay: Challenge cells with pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) and measure the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors or the suppression of T-cell proliferation [52].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: CRISPR-dCas9 Dual-Modification System for Cell Engineering

CRISPR-dCas9 System for OA Cell Therapy

Diagram: Key SOX9 and NF-κB Roles in Cell Fate and Immunity

SOX9 and NF-κB Roles in Fate and Immunity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-dCas9-Mediated Gene Modulation

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-VP64 Activator | Transcriptional activation domain fused to catalytically dead Cas9. Targets and upregulates genes like SOX9. | Select the appropriate dCas9 ortholog (e.g., dSpCas9). VP64 is a common but relatively weak activator; stronger systems (e.g., VPR) may be considered [3]. |

| dCas9-KRAB Repressor | Transcriptional repression domain fused to dCas9. Targets and downregulates genes like RelA. | KRAB is a potent repressor domain. Ensure the dCas9 ortholog (e.g., dSaCas9) matches the gRNA scaffold and PAM requirement [3] [27]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Synthetic single-guide RNA that directs dCas9 to the target DNA sequence. | Chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) enhance stability, improve editing efficiency, and reduce immune stimulation in cells compared to in vitro transcribed (IVT) gRNAs [50]. |

| Lentiviral Vectors | Efficient delivery system for CRISPR components into a wide range of cells, including primary and hard-to-transfect cells. | Allows for stable, long-term expression. Biosafety Level 2 practices are required. Optimize MOI to balance efficiency and cytotoxicity [3]. |