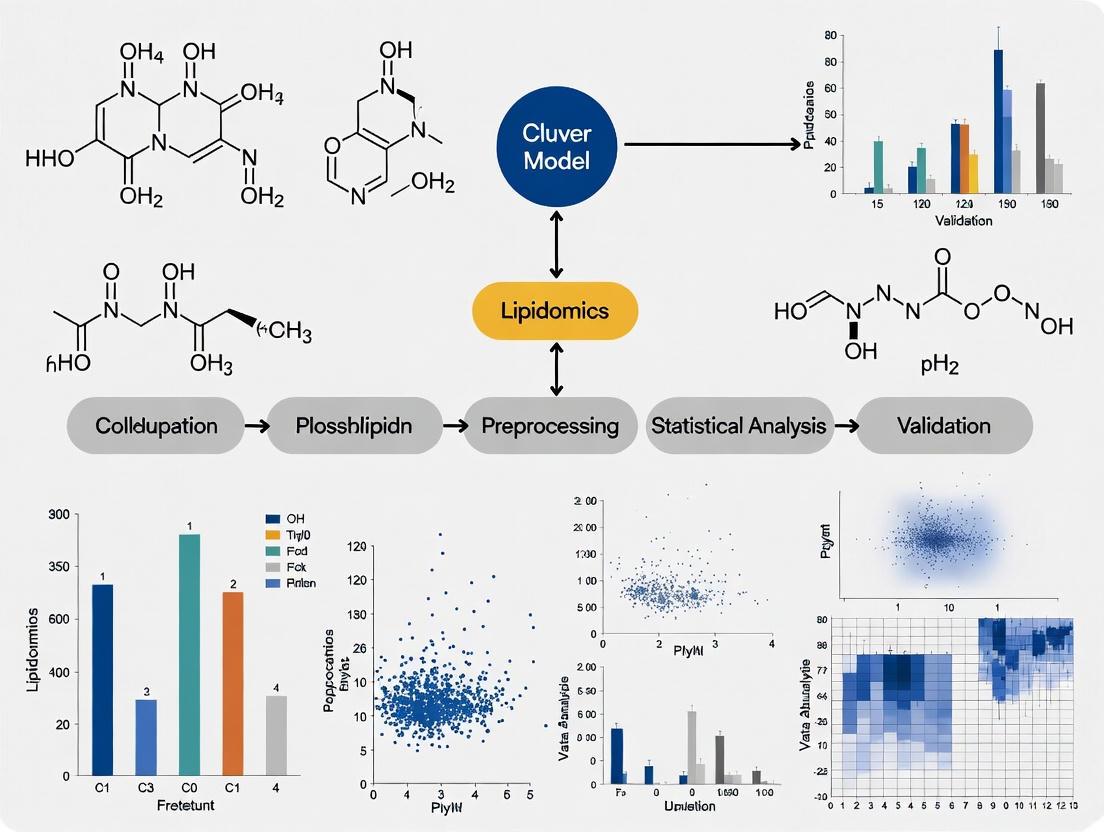

Cross-Validation of Lipidomic Biomarkers Across Diverse Populations: From Discovery to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the cross-validation of lipidomic findings across different populations, a critical step for translating lipid biomarkers into clinical practice.

Cross-Validation of Lipidomic Biomarkers Across Diverse Populations: From Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the cross-validation of lipidomic findings across different populations, a critical step for translating lipid biomarkers into clinical practice. We explore the foundational sources of lipidomic variation—including ethnicity, sex, age, and developmental stage—that necessitate rigorous cross-population validation. The review details advanced methodological approaches from large-scale cohort studies and automated platforms that enhance reproducibility, while addressing key troubleshooting challenges in standardization and data harmonization. Finally, we examine successful validation strategies employing machine learning and independent cohort replication, offering researchers and drug development professionals actionable insights for developing robust, clinically relevant lipidomic biomarkers with broad applicability.

Understanding Lipidomic Diversity: The Biological Imperative for Cross-Population Validation

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) represent the leading cause of death worldwide, imposing a substantial burden on healthcare systems. Dyslipidemia, a condition characterized by abnormal lipid metabolism, serves as a primary risk factor for CVDs. Research has consistently demonstrated that susceptibility to dyslipidemia and its cardiovascular consequences varies significantly across ethnic populations. South Asians (SAs)—individuals originating from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives—experience a disproportionately higher risk of developing dyslipidemia and subsequent CVDs compared to white Europeans (WEs). This review synthesizes evidence from comparative studies to elucidate the distinct lipid profiles, genetic underpinnings, and physiological responses that contribute to these ethnic disparities, providing a foundation for targeted therapeutic strategies and future research directions.

Comparative Lipid Profiles: South Asians vs. White Europeans

Epidemiological and clinical studies have identified a characteristic dyslipidemic pattern among South Asians, often termed "atherogenic dyslipidemia." This profile differs qualitatively and quantitatively from that typically observed in white European populations [1] [2]. The table below summarizes the key differences in lipid parameters between these ethnic groups.

Table 1: Comparative Lipid Profiles in South Asians and White Europeans

| Lipid Parameter | Pattern in South Asians vs. White Europeans | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| LDL Cholesterol | Similar or slightly lower circulating levels, but composed of denser, smaller particles [1]. | Smaller, denser LDL particles are more atherogenic and penetrate the endothelium more easily, contributing to CVD risk at lower serum concentrations [1]. |

| Triglycerides | Significantly higher levels; hypertriglyceridemia affects up to 70% of the SA population [1]. | Drives the formation of atherogenic, small dense LDL and reduces HDL levels, amplifying overall CVD risk [1] [2]. |

| HDL Cholesterol | Lower serum levels of HDL-C, and its protective effect against CVD is weaker [1] [3]. | The functionality of HDL is impaired, diminishing its role in reverse cholesterol transport and vascular protection [1]. |

| Lipoprotein(a) | Higher levels compared to white Europeans [1] [2]. | An independent, genetically determined risk factor for atherosclerosis and thrombogenesis [2]. |

This distinct lipid phenotype in South Asians is not fully captured by standard lipid panels, which measure total LDL cholesterol but not particle size or density. This underscores the need for more refined lipid assessment in this high-risk group.

Genetic and Molecular Basis of Disparities

The ethnic differences in lipid metabolism and CVD risk are rooted in genetic variations that influence key proteins and enzymes in the lipid pathway.

Key Genetic Variations

Mendelian randomization and genetic association studies have identified several genes with polymorphisms that exhibit different frequencies and effects in South Asian populations [1] [4]. These include:

- PCSK9 (Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9): A regulator of LDL receptor degradation. Notably, genetically proxied PCSK9 levels demonstrate a significantly weaker association with LDL-C in South Asians (β = 0.16) compared to Europeans (β = 0.37) [4]. This suggests that PCSK9 inhibitors, while effective, might have a different magnitude of effect in South Asians.

- CELSR2: A gene involved in lipoprotein metabolism, which has been linked to both dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease in South Asians [4].

- ANGPTL3 (Angiopoietin-Related Protein 3): An inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase, identified as a potential causal protein for lipid traits in South Asians [4].

- Other Genes: Variations in Apolipoprotein H, Lipoprotein Lipase, MBOAT7, SGPP1, and SPTLC3 have also been associated with the unique SA lipid profile [1] [3].

Protein Targets and Therapeutic Implications

The identification of these genetically validated proteins provides a roadmap for targeted therapies. Proteins like PCSK9, ANGPTL3, and Apolipoprotein(a) are the targets of existing or developing lipid-lowering drugs [4]. The evidence of population-specific effects highlights the importance of tailoring drug development and clinical trials to include diverse genetic backgrounds to ensure efficacy across populations.

Experimental Evidence: Physiological Responses to Metabolic Stress

Controlled intervention studies provide compelling evidence for the heightened metabolic susceptibility of South Asians. The GlasVEGAS study, a key experimental model, directly compared the metabolic consequences of weight gain in SA and WE men.

Experimental Protocol: The GlasVEGAS Study

- Objective: To compare the effects of induced weight gain on body composition, metabolic responses, and adipocyte morphology in SA versus WE men without overweight or obesity.

- Participants: 14 South Asian and 21 white European men.

- Intervention: A 4–6 week overfeeding regimen designed to induce a 5–7% gain in body weight.

- Pre-/Post-Intervention Assessments:

- Body Composition: Measured via whole-body MRI to quantify adipose tissue (subcutaneous, visceral) and lean tissue volumes.

- Metabolic Function: Assessed via a mixed-meal tolerance test, measuring glucose, insulin, and triglyceride levels over 300 minutes. Insulin sensitivity was calculated using the Matsuda index and HOMA-IR.

- Adipocyte Morphology: A subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue biopsy was taken to analyze adipocyte size and size distribution [5].

Key Findings and Quantitative Data

The study revealed profound ethnic differences in the metabolic response to weight gain, with South Asians experiencing significantly greater adverse effects.

Table 2: Metabolic and Body Composition Responses to Weight Gain in the GlasVEGAS Study

| Parameter | South Asian Men | White European Men | P-value for Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Gain | +6.5% ± 0.3% | +6.3% ± 0.2% | 0.62 |

| Δ Matsuda Index | -38% | -7% | 0.009 |

| Δ Fasting Insulin | +175% | No significant change | 0.02 |

| Δ Lean Tissue Mass | Lower increase | Greater increase | Not specified |

| Baseline Mean Adipocyte Volume | 76% larger | Reference | 0.006 |

| Baseline Large Adipocytes | 60% of total volume | 9.1% of total volume | 0.005 |

The data demonstrates that despite equivalent weight gain, South Asian men suffered a dramatically greater decline in insulin sensitivity and a more pronounced increase in insulin resistance. This was coupled with a baseline adipocyte morphology characterized by larger, lipid-filled cells and a reduced population of small adipocytes, suggesting a limited capacity for safe lipid storage in subcutaneous fat depots [5]. This "adipocyte dysfunction" is hypothesized to lead to ectopic fat deposition and greater metabolic dysfunction in SAs, even with modest weight gain.

Methodologies for Advanced Lipid Research

Understanding ethnic disparities requires sophisticated technologies that move beyond traditional bulk lipid measurements.

Single-Cell Lipidomics

Single-cell lipidomics represents a transformative approach for capturing cellular heterogeneity in lipid metabolism that is obscured in bulk tissue analysis [6].

- Core Technology: Ultra-sensitive high-resolution mass spectrometry (e.g., Orbitrap, FT-ICR) enables the identification and quantification of lipid molecules at the attomole level in individual cells [6].

- Workflow: Individual cells are isolated, their lipidomes are profiled via MS, and the data is computationally analyzed to identify cell-type-specific lipid signatures and metabolic states.

- Application: This technique can reveal how different cell types (e.g., adipocytes, macrophages) within adipose tissue from various ethnic groups contribute to overall lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses [6].

Mass Spectrometry Imaging

Spatial distribution of lipids within tissues is critical for understanding localized effects.

- Core Technology: Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging allows for the visualization of the spatial distribution of hundreds of lipids directly from thin tissue sections [6].

- Workflow: A tissue section is coated with a matrix and irradiated with a laser, which desorbs and ionizes molecules from discrete locations. A mass spectrum is acquired at each pixel, generating a spatial map of lipid abundance.

- Application: MSI can be used to map lipid heterogeneity in atherosclerotic plaques or liver sections, identifying ethnic-specific patterns of lipid accumulation associated with disease progression [6].

The following table details key reagents and databases essential for conducting rigorous lipidomics research in diverse populations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Cross-Population Lipidomics

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function and Application | Relevance to Ethnic Disparity Research |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Lipid Standards | Internal standards for absolute quantification of lipid species in MS-based workflows [7]. | Ensures accurate and comparable quantification of lipid profiles across different study cohorts. |

| LIPID MAPS Database | A curated database providing reference on lipid structures, nomenclature, and metabolic pathways [6]. | Essential for the consistent identification and annotation of lipid species discovered in diverse populations. |

| NIST Plasma Reference Material | A standardized reference plasma used for quality control to monitor batch-to-batch reproducibility [7]. | Critical for maintaining data quality and allowing valid comparisons in multi-center or longitudinal studies. |

| Antibodies for Lipid-Associated Proteins | Proteins like PCSK9, ANGPTL3, and Apo(a) for validating genetic findings via Western Blot or ELISA [4]. | Allows for the functional validation of genetically identified protein targets in plasma or tissue samples from different ethnic groups. |

Visualizing Experimental and Metabolic Pathways

The diagrams below illustrate the core experimental workflow and a key metabolic pathway relevant to the discussed ethnic disparities.

Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Phenotyping

Genetic & Metabolic Pathway in Dyslipidemia

The evidence from genetic, clinical, and experimental studies consistently demonstrates that South Asians possess a unique lipid phenotype and a heightened metabolic susceptibility compared to white Europeans. This is characterized by a more atherogenic lipid profile (featuring small dense LDL, high triglycerides, and dysfunctional HDL), genetic variations in key lipid-regulating genes, and a pronounced deterioration in metabolic health upon weight gain. These findings underscore that ethnicity is a critical biological variable in lipid metabolism and CVD risk. Future research must leverage advanced tools like single-cell lipidomics and mass spectrometry imaging to further unravel the cellular mechanisms of these disparities. Ultimately, this knowledge must inform the development of population-specific risk assessment tools, treatment guidelines, and therapeutic agents to achieve equitable cardiovascular health outcomes.

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, has revealed significant sexual dimorphism in human lipid metabolism, providing crucial insights for precision medicine. The circulatory lipidome demonstrates high individuality and sex specificity, constituting fundamental prerequisites for next-generation metabolic health monitoring [7]. Specific lipid classes, particularly sphingomyelins and ether-linked phospholipids, consistently exhibit pronounced sex-specific patterns that persist across diverse populations and disease states. These sex-specific lipidomic fingerprints influence aging trajectories, disease susceptibility, and therapeutic responses, forming an essential context for cross-validation of lipidomic findings across different populations.

Understanding these dimorphic patterns requires integrating analytical lipidomics with systems biology approaches. This guide objectively compares lipidomic performance data across multiple studies, providing researchers with validated signatures and methodologies for investigating sex-specific lipid metabolism in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Key Lipid Classes in Sexual Dimorphism

Comparative Analysis of Sex-Specific Lipid Patterns

Table 1: Sex-Specific Lipid Signatures Across Multiple Studies

| Lipid Class | Specific Lipid Species | Sex-Bias | Concentration Difference | Biological Context | Study Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphingomyelins | Multiple species | Female-biased | Significantly higher in females [7] | Healthy aging | Lausanne population (N=1,086) [7] |

| Ether-linked phospholipids | Plasmalogens | Female-biased | Significantly higher in females [7] | Healthy aging | Lausanne population (N=1,086) [7] |

| Ceramides | Multiple species | Dynamic with aging | Age-associated increases in both sexes [8] | Aging "crests" | Aging cohort (N=1,030) [8] |

| Hexosylceramides | Hex1Cer | Female-specific | Increased with age only in women [9] | Aging dynamics | Aging cohort (N=1,030) [9] |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamine | LPE | Female-specific | Global increase with aging [9] | Aging dynamics | Aging cohort (N=1,030) [9] |

| Phosphatidylcholine | PC(18:0p/22:6) | Disease-associated | Decreased in pediatric IBD [10] | Inflammatory bowel disease | Pediatric cohort (N=263) [10] |

| Lactosyl ceramide | LacCer(d18:1/16:0) | Disease-associated | Increased in pediatric IBD [10] | Inflammatory bowel disease | Pediatric cohort (N=263) [10] |

Temporal Dynamics in Sex-Specific Lipid Metabolism

The aging process reveals non-linear dynamics in lipid metabolism, with specific "aging crests" where lipidomic changes accelerate. Research has identified three distinct aging crests at 55-60, 65-70, and 75-80 years, with the 65-70 years crest dominant in men and the 75-80 years crest in women [8]. These temporal patterns highlight the importance of considering age as a critical variable when validating lipidomic findings across populations.

During these transitional periods, ether lipids and sphingolipids drive sex-specific aging dynamics, with functional indices indicating compositional shifts in lipid species that suggest impairment of lipid functional categories [8]. These include loss of dynamic properties, alterations in bioenergetics, antioxidant defense, cellular identity, and signaling platforms.

Experimental Methodologies for Lipidomic Profiling

Standardized Lipidomic Workflow Protocols

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Sex-Specific Lipidomic Studies

| Methodological Component | Standard Protocol | Technical Variations | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Semiautomated using stable isotope dilution approach [7] | Manual extraction for specific tissues [11] | Use of reference materials (NIST SRM 1950) [7] [9] |

| Lipid Separation | Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) [7] | Reversed-phase C18 columns [12] | Internal standards for each lipid class [13] |

| Mass Spectrometry Analysis | LC-MS/MS with targeted approach [9] | High-resolution TOF/MS [12] | Batch-to-batch reproducibility monitoring (median 8.5% RSD) [7] |

| Data Processing | Targeted processing with internal standard normalization [7] | Untargeted with chemometrics [11] [14] | Peak area RSD <7.8%, mass accuracy <500 ppb [12] |

| Statistical Analysis | Linear and non-linear modeling [9] | PCA, PLS-DA, random forest [11] | Cross-validation across independent cohorts [10] |

Cross-Validation Approaches Across Populations

Robust validation of sex-specific lipidomic findings requires multiple cohort designs and advanced statistical modeling. The integration of machine learning algorithms has significantly enhanced the identification of reproducible lipid signatures across populations. For instance, in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease, a diagnostic lipidomic signature comprising only lactosyl ceramide (d18:1/16:0) and phosphatidylcholine (18:0p/22:6) was validated across independent cohorts, demonstrating consistent performance [10].

Similarly, in breast cancer research, lipidomic profiling of patients categorized by HR and HER2 status revealed distinct lipid compositions across groups, with triglycerides such as TG(16:0-18:1-18:1)+NH4 showing significant differences, validated through principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and random forest classification [11].

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Networks

Hormonal Regulation of Lipid Metabolism

The sexual dimorphism observed in lipidomic profiles is fundamentally regulated by hormonal influences, with estrogen playing a particularly significant role in shaping female-specific lipid patterns. Estrogen signaling impacts multiple aspects of lipid metabolism, including sphingolipid biosynthesis, peroxisomal ether lipid synthesis, and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation.

In breast cancer research, lipidomic profiles correlate strongly with hormone receptor status, with specific triglycerides and phosphatidylinositol phosphates serving as crucial features for accurate tumor classification [11]. This demonstrates how hormonal signaling directly influences lipid composition in both physiological and pathological states.

Ether Lipid and Sphingolipid Interrelationships

The diagram illustrates the coordinated regulation of ether lipids and sphingolipids by hormonal signaling, particularly estrogen. These lipid networks collectively influence membrane properties, cellular signaling platforms, and antioxidant defense mechanisms—all of which demonstrate sex-specific characteristics and contribute to differential disease susceptibility between males and females.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Core Lipidomics Research Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Sex-Specific Lipidomics

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Application Context | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry | Xevo MRT Mass Spectrometer [12] | High-resolution lipidomic profiling | 100,000 FWHM resolution, <500 ppb mass accuracy [12] |

| Chromatography | ACQUITY Premier UPLC CSH C18 [12] | Lipid separation | 1.7 µm particle size, 2.1 × 50 mm dimensions [12] |

| Quality Control | NIST SRM 1950 [7] [9] | Inter-laboratory standardization | Reference for 'normal' human plasma lipid concentrations [9] |

| Internal Standards | EquiSPLASH [12] | Quantification normalization | Contains multiple stable isotope-labeled lipid species [12] |

| Data Processing | LipoStar2 Software [12] | Lipid identification and statistical analysis | Enables database searching and pathway profiling [12] |

| Statistical Analysis | Random Forest Classification [11] | Pattern recognition in lipidomic data | Identifies significant lipid features in complex datasets [11] |

Analytical Performance Standards

Reproducible sex-specific lipidomics requires stringent quality control measures. High-performance instruments should demonstrate mass accuracy <500 ppb and peak area RSD <7.8% across hundreds of injections to ensure detection of subtle sex-specific differences [12]. Between-batch reproducibility should target median CV <8.5% across all quantified lipid species, with biological variability significantly exceeding analytical variability [7].

For sex-specific analyses, the implementation of sex-stratified quality control pools is recommended, as general reference materials may not capture the full spectrum of sex-specific lipid variation. Additionally, the use of stable isotope internal standards for each lipid class improves quantitative accuracy when comparing concentrations between sexes [13].

The consistent identification of sex-specific lipidomic fingerprints across diverse populations and disease contexts underscores the fundamental importance of considering biological sex as a critical variable in lipidomics research. The robust patterns observed for sphingomyelins and ether-linked phospholipids highlight their roles as key mediators of sexual dimorphism in metabolic health and disease susceptibility.

Cross-validation of these findings across independent cohorts—from aging populations to specific disease contexts—strengthens the evidence for biologically significant sex differences in lipid metabolism. As lipidomics continues to transition toward clinical applications [13], the integration of sex-specific reference ranges and analytical frameworks will be essential for realizing the full potential of precision medicine approaches targeting lipid metabolism.

For researchers investigating sex-specific lipidomics, the consistent implementation of standardized protocols, rigorous quality control measures, and validation across independent populations will ensure the continued advancement of this critical field at the intersection of lipid biology and sexual dimorphism.

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid molecules, has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding metabolic health and disease risk across the human lifespan. Mounting evidence suggests that in utero and early life exposures may predispose individuals to metabolic disorders in later life, with dysregulation of lipid metabolism playing a critical role in such outcomes [15]. The developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) paradigm suggests that prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal influences result in long-term developmental, physiological, and metabolic changes that can contribute to later life disease risk, including cardiovascular diseases and related cardiometabolic conditions [15]. While large population-based studies have established specific lipids to be associated with cardiometabolic disorders in adults, little is known about lipid metabolism in early life until recently [15]. Understanding the key determinants of early life lipid metabolism will inform the development of risk-stratification and early interventions for metabolic diseases. This review synthesizes current evidence on lipidomic trajectories from gestation through childhood and their implications for long-term health outcomes, with particular emphasis on cross-population validation of findings.

Methodological Approaches in Developmental Lipidomics

Analytical Technologies and Protocols

The advances in lipidomic profiling have been driven primarily by technological innovations in mass spectrometry. Most large-scale population studies now utilize ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) for comprehensive lipid profiling [15] [16]. The typical workflow involves lipid extraction using organic solvents such as butanol:methanol (1:1) with 10 mM ammonium formate containing deuterated internal standards, followed by chromatographic separation and mass spectrometric analysis [15].

For lipid extraction, 10 µL of plasma is typically mixed with 100 µL of butanol:methanol (1:1) with 10 mM ammonium formate containing a mixture of internal standards. Samples are vortexed, sonicated for an hour, and then centrifuged before transferring the supernatant for analysis [15]. Liquid chromatography is commonly performed using C18 columns with solvent gradients ranging from aqueous to organic phases, and mass spectrometry analysis is conducted in both positive and negative ion modes with dynamic scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) [15].

Quality control procedures are critical for ensuring data reliability. Most studies incorporate pooled quality control samples extracted alongside the study samples at regular intervals (typically 1 QC per 20 samples) to monitor technical variation, with additional technical QCs to account for instrument performance [15]. The inclusion of reference materials such as NIST 1950 SRM samples allows for alignment across different datasets and laboratories [15].

Cross-Study Methodological Consistency

A comparative analysis of major developmental lipidomics studies reveals consistent methodological approaches across research groups, which enables cross-population validation:

Table 1: Methodological Comparison Across Major Developmental Lipidomics Studies

| Study | Cohort | Sample Size | Lipid Species | Analytical Platform | Age Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS [15] | Australian (Caucasian) | 1074 mother-child dyads | 776 features, 39 classes | UHPLC-MS/MS | 28wk gestation, birth, 6mo, 12mo, 4yr |

| GUSTO [16] | Singaporean (Asian) | 1247 mother-child pairs | 480 species | LC-MS/MS | 26-28wk gestation, birth, 4-5yr postpartum, 6yr |

| HOLBAEK [17] | Danish (Caucasian) | 1331 children | 227 annotated lipids | MS-based lipidomics | Cross-sectional (6-16yr) |

| MDC-CC [18] | Swedish (Caucasian) | 4067 participants | 184 lipid species | Shotgun lipidomics | Adult baseline + 23yr follow-up |

| PROTECT [19] | Puerto Rican | 259 mother-child pairs | Bioactive lipids | HPLC-MS/MS | 26wk gestation, 1-3yr childhood |

Developmental Lipidomic Trajectories from Gestation to Childhood

The Prenatal and Perinatal Period

The lipid environment during gestation plays a crucial role in fetal development. Comprehensive lipid profiling of mother-child dyads in the Barwon Infant Study revealed that the lipidome differs significantly between mother and newborn, with cord serum enriched with long chain poly-unsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) and corresponding cholesteryl esters relative to maternal serum [15]. This selective transfer mechanism ensures adequate LC-PUFAs for fetal brain and nervous system development.

A striking finding from the GUSTO cohort was that levels of 36% of profiled lipids were significantly higher (absolute fold change > 1.5) in antenatal maternal circulation compared to the postnatal phase, with phosphatidylethanolamine levels changing the most [16]. Compared to antenatal maternal lipids, cord blood showed lower concentrations of most lipid species (79%) except lysophospholipids and acylcarnitines [16], suggesting selective placental transfer or fetal metabolism priorities.

The Barwon Infant Study also identified specific associations between antenatal factors and cord serum lipids. The majority of cord serum lipids were strongly associated with gestational age and birth weight, with most lipids showing opposing associations for these two parameters [15]. Each mode of birth showed an independent association with cord serum lipids, indicating that the labor process itself influences neonatal lipid metabolism [15].

Postnatal Development and Early Childhood

The transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life involves dramatic metabolic adaptations, with the lipidome undergoing significant reorganization. In the Barwon Infant Study, researchers observed marked changes in the circulating lipidome with increasing child's age. Specifically, alkenylphosphatidylethanolamine species containing LC-PUFAs increased with child's age, whereas the corresponding lysophospholipids and triglycerides decreased [15].

The GUSTO cohort provided additional insights by comparing changes from birth to 6 years of age with changes between a 6-year-old child and an adult. Changes in lipid concentrations from birth to 6 years were much higher in magnitude (log2FC = -2.10 to 6.25) than the changes observed between a 6-year-old child and an adult (postnatal mother) (log2FC = -0.68 to 1.18) [16]. This indicates that early childhood represents a period of particularly dynamic lipidomic reorganization.

Nutritional influences, particularly breastfeeding, had a significant impact on the plasma lipidome in the first year of life. The Barwon Infant Study reported up to 17-fold increases in a few species of alkyldiaclylglycerols at 6 months of age associated with breastfeeding [15], highlighting how early nutritional exposures can dramatically shape lipid metabolism.

Childhood to Adolescence: Emergence of Cardiometabolic Risk Signatures

As children grow older, specific lipid patterns begin to associate with cardiometabolic risk. The HOLBAEK study, which included children and adolescents with normal weight, overweight, or obesity, identified distinct lipid signatures associated with adiposity and metabolic health [17]. Their analysis revealed that ceramides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylethanolamines were associated with insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk, whereas sphingomyelins showed inverse associations [17].

Notably, the study found that a panel of three lipids predicted hepatic steatosis as effectively as liver enzymes, suggesting the potential for lipidomic signatures in early detection of metabolic complications [17]. The interaction between obesity and age revealed that pubertal development stages showed different lipidomic patterns in normal weight versus overweight/obesity groups, indicating that obesity may disrupt typical developmental lipid trajectories [17].

Table 2: Key Lipid Classes and Their Developmental Associations

| Lipid Class | Gestational Trends | Postnatal Trends | Association with Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-chain PUFAs | Enriched in cord serum vs maternal [15] | Variable based on diet | Essential for neurodevelopment [19] |

| Lysophospholipids | Higher in cord blood vs other lipids [16] | Decrease with age [15] | Signaling molecules; associated with inflammation |

| Ceramides | Not prominently featured in gestation | Increase with obesity [17] | Cardiometabolic risk, insulin resistance [17] |

| Sphingomyelins | Not prominently featured in gestation | Protective inverse associations [17] | Inverse association with cardiometabolic risk [17] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines | Most changed in pregnancy vs postpartum [16] | Alkenyl species increase with age [15] | Associated with cardiometabolic risk [17] |

| Triglycerides | Lower in cord blood [16] | Decrease with age in early childhood [15] | Traditional cardiometabolic risk markers |

Cross-Population Validation of Lipidomic Findings

The generalizability of lipidomic discoveries requires validation across diverse populations. Several studies have undertaken such cross-population comparisons, with consistent findings emerging despite ethnic and geographic differences.

The GUSTO study validated its findings in the independent Barwon Infant Study cohort, noting that associations of cord blood lipidomic profiles with birth weight displayed distinct trends compared to lipidomic profiles associated with child BMI at 6 years [16]. This suggests that different stages of development may have unique lipidomic determinants of growth and adiposity.

When comparing pediatric versus maternal obesity signatures, researchers found similarities in association with consistent trends (R² = 0.75) between child and adult BMI [16]. However, a larger number of lipids were associated with BMI in adults (67%) compared to children (29%) [16], indicating that the lipidomic signature of adiposity becomes more pronounced with age.

The Malmö Diet and Cancer-Cardiovascular Cohort study demonstrated that lipidomic risk scores showed only marginal correlation with polygenic risk scores, indicating that the lipidome and genetic variants may constitute largely independent risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [18]. This finding has important implications for risk prediction models, suggesting that lipidomic profiling provides complementary information to genetic testing.

Pathway Visualization: Lipid Metabolism in Early Development

The following diagram illustrates key lipid metabolic pathways and their changes throughout early development, based on findings from multiple cohort studies:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful lipidomic research requires specific reagents and materials to ensure accurate, reproducible results. The following table details key research reagent solutions used across the cited studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Developmental Lipidomics

| Reagent/ Material | Function | Example Specifications | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | Quantification reference | Deuterated or non-physiological IS mixture [15] | Critical for accurate quantification |

| Butanol:Methanol (1:1) | Lipid extraction | With 10 mM ammonium formate [15] | Efficient extraction of diverse lipid classes |

| C18 UHPLC Columns | Lipid separation | ZORBAX eclipse plus C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) [15] | High-resolution separation |

| Reference Plasma | Quality control | NIST 1950 SRM sample [15] | Cross-laboratory standardization |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive | 10 mM in mobile phases [15] | Enhances ionization efficiency |

| SPE Columns | Sample cleanup | Strata-X Polymeric SPE [19] | Bioactive lipid isolation |

| Deuterated Standards | Bioactive lipid quant | Oxylipins and parent PUFAs [19] | Essential for oxylipin analysis |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Biomarker Development

The longitudinal trajectories of lipid species from gestation through childhood offer valuable insights for both biomarker and therapeutic development. Lipidomics is increasingly being recognized as an important tool for the identification of druggable targets and biochemical markers [20]. Several promising avenues have emerged from recent developmental studies:

Predictive Biomarkers for Metabolic Disease

The Malmö Diet and Cancer-Cardiovascular Cohort study demonstrated that lipidomic risk scores could stratify participants into risk groups with a 168% increase in type 2 diabetes incidence rate in the highest risk group and a 77% decrease in the lowest risk group compared to average case rates [18]. Notably, this lipidomic risk assessment required only a single mass spectrometric measurement that is relatively cheap and fast compared to genetic testing [18].

In pediatric populations, the HOLBAEK study identified specific lipid signatures that could predict hepatic steatosis as effectively as liver enzymes [17], suggesting opportunities for non-invasive monitoring of metabolic liver disease in children. Their finding that ceramides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylinositols were associated with insulin resistance while sphingomyelins showed protective associations [17] points to potential biomarkers for early detection of metabolic dysfunction.

Intervention Monitoring and Personalized Approaches

Lipidomic profiling also shows promise for monitoring intervention responses. In the PREVIEW study, researchers identified serum lipids that could serve as evaluative or predictive biomarkers for individual glycemic changes following diet-induced weight loss [21]. They found that dietary intervention significantly reduced diacylglycerols, ceramides, lysophospholipids, and ether-linked phosphatidylethanolamine, while increasing acylcarnitines, short-chain fatty acids, and organic acids [21].

The HOLBAEK intervention study further demonstrated that family-based, nonpharmacological obesity management reduced levels of ceramides, phospholipids, and triglycerides, indicating that lowering the degree of obesity could partially restore a healthy lipid profile in children and adolescents [17]. This suggests that lipidomic profiling could be used to monitor response to lifestyle interventions in pediatric populations.

The comprehensive profiling of lipidomic changes from gestation through childhood has revealed dynamic developmental trajectories that reflect both normal metabolic maturation and early signs of disease predisposition. Cross-population studies have consistently demonstrated that early life factors including gestational age, birth weight, mode of delivery, and infant feeding practices leave discernible imprints on the lipidome that may influence long-term health outcomes.

Future research directions should include expanded longitudinal sampling across the entire developmental spectrum, from gestation through older age, to better understand critical transition periods. Additionally, integration of lipidomics with other omics technologies—including genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—will provide more comprehensive insights into the complex interplay between genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and metabolic health across the lifespan.

The demonstrated utility of lipidomic signatures for risk prediction and intervention monitoring suggests strong potential for clinical translation. However, standardization of analytical protocols and validation in diverse populations will be essential before widespread clinical implementation. As these methods become more accessible and cost-effective, lipidomic profiling may become an valuable tool for personalized prevention and management of metabolic diseases from early life.

Impact of Lifestyle and Environmental Factors on Population-Specific Lipid Profiles

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of cellular lipids, has evolved into a powerful tool for understanding metabolic health and disease risk. While genetic predispositions establish baseline lipid levels, a growing body of evidence underscores that lifestyle and environmental factors are potent modulators of the lipid profile, contributing to significant variations across different populations. These influences range from broad geographical and climatic conditions to specific dietary and physical activity patterns. Framing lipidomic findings within this context is crucial for cross-population research, as it helps disentangle the complex interplay of inherent and external factors shaping lipid metabolism. This guide objectively compares lipid profile data from diverse populations and details the experimental protocols that enable robust, comparable findings essential for drug development and public health strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Lipid Profiles Across Populations

Environmental and lifestyle factors produce distinct lipid profile signatures in different populations. The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from key studies, highlighting these disparities.

Table 1: Prevalence of Dyslipidemia and Lipid Abnormalities Across Populations

| Population / Study Cohort | Dyslipidemia Prevalence | Key Lipid Abnormalities (Prevalence or Mean Levels) | Primary Associated Environmental/Lifestyle Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islamabad & Rawalpindi, Pakistan [22] | 86% | High TG (50%), Low HDL (48%), High LDL (31%), High TC (29%) | Urbanization, dietary shifts |

| Peruvian Cohort (Rural Areas) [23] | High Non-HDL-C: 88.0% | Hypertriglyceridemia: Lower prevalence vs. urban (PR=0.75) | Rural lifestyle, diet high in carbohydrates, high physical activity [23] |

| Peruvian Cohort (Semi-Urban Areas) [23] | High Non-HDL-C: 96.0% | High LDL-C: Higher prevalence vs. highly urban (PR=1.37) | Transitional economy, changing dietary patterns |

| Chinese Middle-Aged & Elderly [24] | Not Specified | Nonlinear associations with TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C | Air pollutants (PM~2.5~, NO~2~, O~3~), meteorological factors (temperature, humidity) |

| Metabolic Syndrome Patients (India) [25] | 91% (≥1 abnormal lipid) | TC: 220.6 ± 38.5 mg/dL, TG: 186.9 ± 54.3 mg/dL, LDL-C: 140.4 ± 31.2 mg/dL, HDL-C: 38.7 ± 8.9 mg/dL | Central obesity, insulin resistance, dietary habits |

Table 2: Lipid Profile Ratios and Cardiovascular Risk Indicators

| Lipid Ratio | Pakistan Study Cohort [22] | Ideal / Low-Risk Ratio | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-C to HDL-C Ratio | 2.7 | < 2.0 | Higher than ideal, indicating elevated cardiovascular disease risk [22] |

| Triglyceride to HDL-C Ratio | 4.7 | < 2.0 | Higher than ideal, indicating elevated risk of insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease [22] |

| Cholesterol to LDL-C Ratio | 1.8 | ~1.0 - 3.0 (Context dependent) | Within normal range [22] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Cross-Population Lipidomics

To ensure findings are valid and comparable across different studies and populations, rigorous and standardized experimental protocols are mandatory. The following sections detail key methodologies.

Protocol 1: Blood Collection and Standard Lipid Profile Analysis

This protocol is foundational for clinical lipidology and was used in studies such as the Pakistani dyslipidemia investigation and the Metabolic Syndrome study in India [22] [25].

- Objective: To accurately measure standard lipid panel components (Total Cholesterol, Triglycerides, LDL-C, and HDL-C) from blood serum.

- Sample Collection:

- Sample Processing:

- Collected blood samples are allowed to clot.

- Samples are centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate serum from blood cells [22].

- Biochemical Analysis:

- Serum is analyzed on automated clinical chemistry analyzers (e.g., Cobas e-311) [22].

- Enzymatic colorimetric methods are employed to quantify Total Cholesterol, Triglycerides, and HDL-C [25].

- LDL-C is often calculated using the Friedewald formula (provided TG levels are <400 mg/dL): LDL-C = Total Cholesterol - HDL-C - (Triglycerides/5) [25].

- Quality Control: Analysis batches include standard calibrators and control samples to ensure accuracy and reproducibility [22] [25].

Protocol 2: Advanced MS-Based Lipidomics for Biomarker Discovery

This protocol leverages mass spectrometry for deep phenotyping and is critical for studies exploring predictive biomarkers and subtle metabolic shifts, such as the PREVIEW sub-study [26] [27].

- Objective: To identify and quantify a wide panel of lipid species (hundreds to thousands) for discovery of evaluative or predictive biomarkers.

- Sample Preparation:

- A stable isotope dilution approach is used for robust quantification, where known amounts of isotope-labeled lipid standards are added to the samples prior to extraction [7].

- Semiautomated or manual liquid-liquid extraction (e.g., using methyl-tert-butyl ether) is performed to isolate lipids from serum or plasma [7].

- Lipid Separation and Analysis:

- Technique: Liquid Chromatography coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Chromatography: Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) is often used for class-specific separation, while Reversed-Phase Chromatography (RPLC) separates lipids by acyl chain length and saturation [26].

- Mass Spectrometry: A high-resolution mass spectrometer operates in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) modes to measure the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of intact lipid ions and their characteristic fragments [26] [27].

- Data Processing:

- Quality Control:

Protocol 3: Statistical and Pathway Analysis for Interpretation

This protocol outlines the analytical workflow for deriving biological meaning from complex lipidomics datasets, particularly in cross-population and intervention studies [24] [28].

- Objective: To identify statistically significant lipid alterations and place them in a biological context.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalization: Data is normalized to correct for variations in sample concentration and instrument sensitivity.

- Batch Effect Correction: Methods like ComBat are applied to remove technical artifacts from different processing batches [28].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Univariate Analysis: T-tests (for two groups) or ANOVA (for multiple groups) are used to identify lipids with significant abundance changes, with False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing [28].

- Multivariate Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) are used to visualize group separations and identify lipids driving the differences [28].

- Machine Learning: For complex datasets, Random Forest models can be used to rank the importance of environmental factors (e.g., air pollutants, temperature) and identify nonlinear associations with lipid levels [24].

- Pathway Analysis:

- Differentially abundant lipids are input into tools like MetaboAnalyst.

- Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) or Pathway Topology Analysis is performed to identify enriched metabolic pathways (e.g., glycerophospholipid metabolism, sphingolipid signaling), providing mechanistic insights [28].

The following diagram visualizes the integrated workflow from sample collection to biological insight.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Lipidomics Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Serum Separator Tubes (SST) | Collects and preserves blood samples; gel barrier separates serum during centrifugation for clinical lipid profiling [22]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Lipid Standards | Added to samples before extraction; enables absolute quantification by correcting for losses during preparation and ion suppression in MS [7]. |

| NIST Plasma Reference Material | Quality control material analyzed across batches to monitor and correct for instrumental drift and ensure reproducibility in large-scale studies [7]. |

| Chromatography Columns (HILIC & RPLC) | HILIC columns separate lipids by class (polar head group); RPLC columns separate by acyl chain hydrophobicity, providing comprehensive lipidome coverage [26]. |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits | Reagent kits for colorimetric or fluorometric measurement of specific lipid classes (e.g., total cholesterol, triglycerides) on automated analyzers [25]. |

The impact of lifestyle and environmental factors on lipid profiles is profound and varies significantly across populations, driven by factors such as urbanization, diet, altitude, and air pollution. Cross-validation of lipidomic findings demands rigorous, standardized experimental protocols—from meticulous blood collection and advanced mass spectrometry to sophisticated statistical and pathway analysis. For researchers and drug development professionals, acknowledging and controlling for these population-specific influences is paramount. It ensures the discovery of robust biomarkers, facilitates the development of targeted therapies, and ultimately paves the way for more effective, personalized cardiovascular and metabolic disease interventions on a global scale.

Advanced Lipidomic Platforms and Study Designs for Multi-Center Validation

High-Throughput HILIC and RPLC-MS/MS Platforms for Large-Scale Cohort Analysis

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) serves as the cornerstone of modern large-scale lipidomic and metabolomic studies. For comprehensive analysis of complex biological samples, no single chromatographic technique can sufficiently capture the entire metabolome. Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) and Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) have emerged as complementary techniques that, when combined, significantly expand metabolome coverage [29]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their performance characteristics, implementation protocols, and applications in large-scale cohort studies, framed within the context of cross-validating lipidomic findings across different populations.

Technical Comparison of HILIC and RPLC Platforms

Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) employs hydrophobic stationary phases (typically C18 or C8) with a polar mobile phase. Separation occurs primarily through hydrophobic interactions, where analytes are retained based on their hydrophobicity. Non-polar compounds with longer alkyl chains and higher molecular weight exhibit stronger retention, while polar compounds elute quickly, often with inadequate separation from the void volume [30] [31].

Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) utilizes hydrophilic stationary phases (e.g., bare silica, amide, or zwitterionic materials) with a mobile phase consisting of a high proportion of organic solvent (typically acetonitrile) with a small amount of aqueous buffer. The separation mechanism involves partition of analytes between the organic-rich mobile phase and a water-enriched layer immobilized on the stationary phase, supplemented by secondary electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding [32]. This mechanism provides excellent retention for polar and ionizable compounds that are poorly retained in RPLC.

Performance Characteristics in Cohort Studies

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of HILIC and RPLC Platforms

| Performance Metric | HILIC Platform | RPLC Platform | Combined Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility (Intrabatch CV) | <12% [29] | Similar to HILIC [29] | Maintains performance of individual methods |

| Reproducibility (Interbatch CV) | <22% (over 40 days) [29] | Similar to HILIC [29] | Maintains performance of individual methods |

| Polar Compound Coverage | Excellent for logD < 0 [30] | Limited for polar compounds [30] | Up to 108% more features in plasma [29] |

| Non-polar Compound Coverage | Limited | ~90% for logD > 0 [30] | Comprehensive coverage |

| Peak Width | ~7 seconds [30] | ~4 seconds [30] | Platform-dependent |

| Analysis Time | ~25 minutes [30] | ~20-24 minutes [30] | Combined runtime ~45 minutes |

Table 2: Compound Class Coverage by Chromatographic Platform

| Compound Class | HILIC Performance | RPLC Performance | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phospholipids | Class-based separation [31] | Species-based separation [31] | HILIC co-elutes by class; RPLC separates by fatty acyl chains |

| Sphingolipids | Excellent for glycosphingolipids [10] | Good for ceramides [13] | Complementary coverage |

| Lyso-phospholipids | Effective retention [31] | Moderate retention [31] | Both suitable with different selectivity |

| Acylcarnitines | Excellent retention [33] | Limited retention | HILIC preferred |

| Cholesteryl Esters | Poor retention | Excellent retention [13] | RPLC preferred |

| Triacylglycerols | Limited retention | Excellent retention [10] | RPLC preferred |

| Organic Acids | Good with anion exchange [30] | Limited retention | IC complementary to both |

Experimental Protocols for Large-Scale Cohort Analysis

Sample Preparation Workflow

For comprehensive lipidomic profiling, a standardized sample preparation protocol is essential for maintaining reproducibility across large cohorts:

- Protein Precipitation: Add 375 μL ice-cold methanol to 50 μL plasma, vortex thoroughly [31].

- Lipid Extraction: Add 1250 μL methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), vortex, and incubate for 1 hour at 4°C with shaking [31].

- Phase Separation: Add 375 μL water, vortex, centrifuge (10 min, 4°C, 1000×g) [31].

- Organic Phase Collection: Transfer the upper organic phase to a new tube.

- Re-extraction: Repeat extraction of aqueous phase with 500 μL MTBE/MeOH/H2O (4/1.2/1, v/v) [31].

- Combination and Evaporation: Combine organic phases and evaporate to dryness under vacuum [31].

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute in 200 μL pure isopropanol with vigorous vortexing [31].

- Dilution: Dilute with isopropanol to final concentration of 0.03 μL plasma/μL isopropanol [31].

HILIC-MS/MS Methodology

Optimal Stationary Phase: Zwitterionic sulfobetaine (ZIC-HILIC) column (e.g., SeQuant ZIC-HILIC, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) operated at neutral pH provides optimal performance for diverse hydrophilic metabolites [29].

Mobile Phase Composition:

- Eluent A: 95% acetonitrile with 5% water containing 5-10 mM ammonium formate or acetate [30] [29]

- Eluent B: 95% water with 5% acetonitrile containing 5-10 mM ammonium formate or acetate [30] [29]

Gradient Program:

- 0-20 min: 0-40% B (curve linear or slightly convex)

- 20-22 min: 40-100% B

- 22-25 min: 100% B (wash)

- 25-25.1 min: 100-0% B

- 25.1-30 min: 0% B (re-equilibration) [30] [32]

MS Parameters:

- Ionization: ESI positive/negative switching

- Mass Analyzer: Q-TOF or Orbitrap for untargeted; TQ-SIM for targeted

- Scan Range: m/z 100-1500

- Source Temperature: 300°C

- Drying Gas Flow: 10 L/min [30] [29]

RPLC-MS/MS Methodology

Optimal Stationary Phase: C18 columns with aqueous stability (e.g., Hypersil GOLD for urine, Zorbax SB aq for plasma) [29].

Mobile Phase Composition:

- Eluent A: Acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v) with 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid [31]

- Eluent B: Isopropanol/acetonitrile/water (85:10:5, v/v) with 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid [31]

Gradient Program:

- 0-20 min: 10-86% B (curve 4)

- 20-22 min: 86-100% B

- 22-25 min: 100% B (wash)

- 25-25.1 min: 100-10% B

- 25.1-30 min: 10% B (re-equilibration) [31]

MS Parameters:

- Ionization: ESI positive/negative switching

- Mass Analyzer: Q-TOF or Orbitrap

- Scan Range: m/z 200-2000

- Source Temperature: 300°C

- Drying Gas Flow: 12 L/min [31]

Quality Control Procedures

For large-scale cohort analysis, implement rigorous quality control:

- Pooled QC Samples: Create from aliquots of all samples; analyze regularly throughout batch [7]

- Reference Materials: Include NIST SRM 1950 plasma with each batch [7]

- Internal Standards: Use deuterated lipid standards for quantification (e.g., SPLASH LIPIDOMIX) [31]

- System Suitability Tests: Monitor retention time stability, peak width, and intensity of reference compounds [7]

Figure 1: Integrated HILIC and RPLC-MS/MS Workflow for Large-Scale Cohort Analysis

Cross-Validation of Lipidomic Findings Across Populations

The combination of HILIC and RPLC platforms enables robust cross-validation of lipidomic signatures across diverse populations. This orthogonal approach verifies that identified biomarkers represent true biological signals rather than method-specific artifacts.

Case Study: Cardiovascular Risk Stratification

In a large-scale CAD cohort (n = 1,057), untargeted lipidomics revealed characteristic lipid signatures associated with adverse cardiovascular events [33]. The most prominent upregulated lipids in patients with cardiovascular events belonged to phospholipids and fatty acyls classes. The orthogonal separation by HILIC and RPLC confirmed these findings, with the platelet lipidome identifying 767 lipids with characteristic changes in patients with adverse CV events [33].

Statistical models incorporating both HILIC and RPLC data demonstrated improved risk prediction. The CERT2 score, incorporating ceramides (better separated by RPLC) and phosphatidylcholines (well-separated by both techniques), yielded hazard ratios of 1.44-1.69 for cardiovascular mortality across multiple cohorts [13].

Case Study: Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

A blood-based diagnostic lipidomic signature for pediatric IBD was identified and validated across multiple cohorts using combined chromatographic approaches [10]. The signature comprised:

- Increased lactosyl ceramide (d18:1/16:0) - well-separated by HILIC

- Decreased phosphatidylcholine (18:0p/22:6) - separated by both techniques

This signature achieved an AUC of 0.85 (95% CI 0.77-0.92) in discriminating IBD from symptomatic controls, significantly outperforming hsCRP (AUC = 0.73) [10]. The combination of HILIC and RPLC provided complementary coverage that enhanced diagnostic performance.

Biological Variability and Analytical Reproducibility

In population studies (n = 1,086), HILIC-based methodology demonstrated robust measurement of 782 circulatory lipid species spanning 22 lipid classes [7]. The median between-batch reproducibility was 8.5% across 13 independent batches. Critically, biological variability per lipid species significantly exceeded batch-to-batch analytical variability, confirming that technical performance adequately captures biological signals [7].

Figure 2: Cross-Validation Framework for Lipidomic Findings Across Populations

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HILIC and RPLC-MS/MS Lipidomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function & Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX [31] | Quantification normalization | "One ISTD-per-lipid class" approach |

| Reference Materials | NIST SRM 1950 [7] | Quality control, inter-lab standardization | Provides consensus values |

| HILIC Columns | ZIC-HILIC [29], BEH Amide [30] | Polar compound separation | Zwitterionic for broad coverage |

| RPLC Columns | Accucore C18 [31], Hypersil GOLD [29] | Non-polar compound separation | Aqueous-stable for lipidomics |

| Extraction Solvents | MTBE, methanol, isopropanol [31] | Lipid extraction from biological matrices | MTBE method provides high recovery |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Ammonium formate, ammonium acetate [32] | MS-compatible buffering | Volatile for MS detection |

HILIC and RPLC-MS/MS platforms offer complementary strengths for large-scale cohort lipidomic analysis. RPLC provides excellent coverage for non-polar to moderately polar lipids (~90% for logD > 0), while HILIC effectively captures polar metabolites poorly retained by RPLC. When combined, these platforms expand metabolome coverage by 44-108% compared to RPLC alone [29], enabling more comprehensive biomarker discovery.

The orthogonal separation mechanisms facilitate cross-validation of lipidomic findings across different populations, strengthening the biological significance of identified signatures. Implementation of standardized protocols with rigorous quality control enables reproducible measurement of hundreds of lipid species across large cohorts, with between-batch reproducibility of <10% achievable [7].

For large-scale cohort studies aiming to discover and validate lipidomic biomarkers, a combined HILIC and RPLC approach provides the most comprehensive coverage and strongest validation framework, ultimately enhancing the translation of lipidomic findings into clinically useful applications.

Reproducibility is a fundamental pillar of scientific research, yet it remains a significant challenge in lipidomics, especially in multi-center studies where protocol variations can lead to inconsistent results [34]. The integration of lipidomic profiles into clinical and precision medicine hinges on the ability to cross-validate findings across diverse populations reliably. Automated sample preparation has emerged as a critical technological solution, minimizing manual handling errors and standardizing protocols to enhance data reproducibility [35] [36]. This guide objectively compares the performance of automated and manual sample preparation methods, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data to inform their analytical strategies for large-scale, multi-population lipidomic studies.

The Role of Standardization in Cross-Validation Lipidomics

Cross-validation of lipidomic findings across different populations requires exceptionally high levels of analytical consistency. Biological lipidomes are highly dynamic and influenced by genetics, diet, and environment, introducing substantial inter-individual variability that can obscure genuine biomarker signals [26]. In multi-center studies, this inherent biological variation is compounded by pre-analytical inconsistencies arising from differences in sample handling, extraction techniques, and operator skill across sites [34].

Automated sample preparation directly addresses these challenges by implementing standardized, protocol-driven workflows that are consistently replicated across instruments and laboratories. This standardization is crucial for reducing operational variances, thereby ensuring that observed lipid differences reflect true biological phenomena rather than technical artifacts [35]. The resulting improvement in data quality strengthens the statistical power of studies exploring lipidomic variations across demographic and geographic populations, ultimately accelerating the translation of lipid biomarkers into clinical practice [37].

Performance Comparison: Automated vs. Manual Sample Preparation

Direct comparative studies provide compelling evidence for the advantages of automation in lipidomic sample preparation. The following data, synthesized from cross-validation studies, highlights key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance comparison between manual and automated sample preparation for lipidomics

| Performance Metric | Manual Preparation | Automated Preparation | Implications for Multi-Center Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision (CV%) | Majority < 15% [38] | Majority < 15%; occasional species >20% [38] | Good overall precision; automation requires method optimization for specific lipids |

| Throughput | Limited by manual pipetting | High; 96-well or 384-well plate formats [35] [36] | Essential for processing thousands of samples in large biobanks [38] |

| Calibration Accuracy (Mean Bias%) | Mostly between -10% to +10% [38] | Mostly between -20% to +20% [38] | Automated methods meet acceptance criteria but may show slightly higher variability |

| Sample-to-Sample Variation | Higher due to human intervention | 1.8-fold reduction reported in proteomics [36] | Directly enhances reproducibility across study sites |

| Operator Dependency | High | Minimal after initial programming | Critical for standardizing protocols across multiple research centers |

Case Study: Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) Analysis in Whole Blood

A robust comparison between an optimized automated method and a manual method for quantifying the alcohol biomarker PEth 16:0/18:1 in whole blood demonstrates automation's practical benefits. The automated method used a liquid handler for a 96-well plate format with blood samples pre-treated by freezing to reduce viscosity and clogging. The manual method involved traditional tube-based liquid-liquid extraction [39].

Both methods were validated and showed good agreement, with coefficients of variation (CV) below 15% and accuracy within 15% of the target value. A key finding was that the automated method effectively eliminated pipetting challenges associated with viscous whole blood, improving operational robustness. Furthermore, the automated 96-well format significantly increased throughput, enabling rapid processing of large sample volumes received by the laboratory [39].

Case Study: Cross-Validation of a High-Throughput Lipidomics Platform

In another systematic comparison, a manual protein precipitation protocol was cross-validated against an automated procedure using a Hamilton Microlab STAR liquid handling system for the analysis of multiple lipid classes in plasma.

The results demonstrated that both methods produced CVs mostly below 15% across a set of internal standards (n=40). While the manual preparation yielded slightly better accuracy for back-calculated standard concentrations (majority within ±10% vs. ±20% for automation), the automated procedure satisfactorily met method acceptance criteria. The authors concluded that automation offers a cost-effective solution for large-scale lipidomic studies, despite manual preparation in glass vials potentially providing marginally superior precision for smaller datasets [38].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure experimental reproducibility, this section outlines the specific methodologies from the cited comparison studies.

- Sample Pretreatment: For the automated method, all whole blood samples (calibrators, quality controls, and clinical samples) were frozen at -80 °C for at least 60 minutes to induce hemolysis. This step reduces viscosity and prevents pipette tip clogging.

- Automated Extraction (96-well plate):

- An automated liquid handler was used to transfer 50 µL of pre-treated frozen blood and 200 µL of 2-propanol (containing internal standard) to a 96-well plate.

- The aspirating and dispensing parameters for the blood and solvent were specifically optimized for the robot.

- The plate was sealed, mixed, and then centrifuged.

- The supernatant was directly transferred to an analysis plate for UHPLC-MS/MS.

- Manual Extraction (Tube-based):

- 50 µL of untreated whole blood was manually pipetted into a tube.

- 200 µL of 2-propanol (with internal standard) was added.

- The tube was vortex-mixed and then centrifuged.

- The supernatant was manually transferred to a vial for UHPLC-MS/MS.

- UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis: Chromatographic separation was performed, and PEth 16:0/18:1 was detected and quantified using mass spectrometry in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode.

- Sample Preparation: The study used a simple protein precipitation method suitable for automation.

- Manual Protocol: One part plasma (25 µL) was transferred to a low-protein-binding Eppendorf tube, and five parts of an isopropanol/acetonitrile (1:2, v/v) solution containing a cocktail of deuterated internal standards were added. Samples were vortexed, shaken for two hours at 5°C, and then centrifuged. The supernatant was transferred to glass vials for LC-MS/MS analysis.

- Automated Protocol: The above steps were replicated using a Hamilton Microlab STAR liquid handling system in a 96-well plate format. After centrifugation, the supernatant was automatically transferred to a 96-well analysis plate.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis (LipidQuan Workflow):

- Instrumentation: Waters ACQUITY UPLC I-Class PLUS System coupled to a Xevo TQ-XS Mass Spectrometer.

- Chromatography: An ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide Column (2.1 mm x 100 mm, 1.7 µm) was used. Lipids were separated over an 8-minute gradient.

- Mass Spectrometry: Data acquisition was performed in both positive and negative ionization modes using targeted multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

- Data Analysis: Lipid identification and quantification were performed using TargetLynx software, comparing back-calculated concentrations of standards and QC replicates between the two preparation methods.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for implementing robust and reproducible lipidomics sample preparation, whether manual or automated.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for lipidomic sample preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Workflow | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards (e.g., Splash Lipidomix) | Corrects for extraction efficiency and instrument variability; essential for quantification [40] [38] | Added to plasma/serum before protein precipitation to monitor performance of each sample [38] |

| Isopropanol/Acetonitrile Solvent System | Precipitates proteins and efficiently extracts a broad range of lipid classes [38] | Used in a 1:2 (v/v) ratio with plasma for simple and automatable protein crash [38] |

| Chlorinated Solvents (e.g., Dichloromethane) | Facilitates liquid-liquid extraction for comprehensive lipid recovery [40] | Used in a modified Bligh & Dyer method (DCM/MeOH/water 2:2:1) for wide lipid coverage [40] |

| 96-Well Plates (Polypropylene) | Standardized format for high-throughput automated processing | Used in robotic systems for holding samples, reagents, and final extracts [39] [38] |

| Calibrator Solutions (e.g., Odd-Chained Lipidomix) | Enables construction of calibration curves for absolute quantification | Spiked into control matrix to create a standard curve for concentration calculations [38] |

Workflow and Impact Visualization

The logical progression from sample collection to data acquisition, and the comparative impact of manual versus automated methods on data quality, can be visualized through the following diagrams.

Diagram 1: Comparative sample preparation workflow.

Diagram 2: Impact on multi-center study objectives.

The consistent implementation of automated sample preparation is a critical success factor for cross-validating lipidomic findings across different populations. While manual methods can achieve excellent precision on a small scale, the operational superiority of automation in reducing human error, standardizing protocols, and enabling high-throughput is undeniable for multi-center research [39] [36] [38]. As the field moves toward integrating lipidomics into precision medicine, the adoption of these robust, scalable workflows will be indispensable for generating reproducible and clinically actionable data from diverse global cohorts.

Crossover study designs represent a powerful methodological approach in clinical research, enabling investigators to compare interventions with greater precision by having each participant serve as their own control. This design significantly reduces inter-individual variability—a major confounding factor in parallel-group trials—particularly valuable in emerging fields like lipidomics where biological variability can obscure treatment effects. By minimizing the influence of confounding variables and reducing sample size requirements, crossover trials offer distinct advantages for detecting subtle intervention effects. However, these designs require careful implementation to address potential carryover effects and other methodological challenges. This review examines the fundamental principles, applications, and methodological considerations of crossover designs, with emphasis on their growing importance in nutritional science, pharmacology, and biomarker research.

Crossover studies are randomized, repeated measurement designs where participants receive multiple interventions in sequential periods, typically separated by washout phases [41]. In the most basic 2x2 crossover design, participants are randomly allocated to one of two sequences: receiving treatment A followed by B, or treatment B followed by A [42]. This design enables direct within-participant comparison of interventions, effectively controlling for inherent biological variability that often confounds parallel-group studies where each participant receives only one treatment [43].

The fundamental strength of crossover designs lies in their ability to separate within-participant variability from between-participant variability [43]. In traditional parallel-group designs, between-participant variability inflates standard errors, potentially masking true treatment effects. By using each participant as their own control, crossover designs eliminate between-participant variability from treatment effect estimates, resulting in greater statistical power and precision [43]. This advantage is particularly valuable when studying heterogeneous populations or interventions with modest effect sizes, as it allows researchers to detect differences with smaller sample sizes—in some cases reducing participant requirements by 60-70% compared to parallel designs [41].

Crossover designs have evolved significantly since their initial application in agricultural experiments in the mid-nineteenth century [43]. Today, they are extensively used in pharmaceutical development (particularly bioequivalence studies), nutritional science, psychology, and biomarker research [43]. Their utility continues to expand with the growing emphasis on personalized medicine and understanding of individual differences in treatment response.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Core Components and Terminology

Understanding crossover designs requires familiarity with several key components:

- Treatments: The interventions being compared, typically denoted by capital letters (A, B, etc.) [42]

- Sequence: The order in which treatments are administered to participant groups (e.g., AB or BA) [41]

- Period: The time during which a specific treatment is administered and outcomes are measured [41]

- Washout: A critical interval between treatment periods where no intervention is administered, allowing treatment effects to dissipate [41]

The most fundamental crossover design is the 2x2 crossover (2 treatments, 2 sequences, 2 periods), though more complex designs exist for comparing multiple treatments across multiple periods [43]. The design's structure enables researchers to distinguish several effects: direct treatment effects, period effects (where outcomes differ based on timing regardless of treatment), and sequence effects (where the order of administration influences results) [42].

Statistical Foundation

The statistical advantage of crossover designs becomes apparent when comparing their model to parallel-group designs. In a parallel-group trial, the response for the k-th subject in the i-th group is represented as:

Yik = μ + τd*(i) + E_ik

where Eik includes both between-subject variability (σs²) and within-subject variability (σ²) [43]. This combination inflates standard errors for treatment effect estimates. In contrast, crossover designs enable estimation of treatment effects through within-subject differences, effectively eliminating between-subject variability and resulting in smaller standard errors and greater statistical power [43].

Table 1: Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Crossover Designs

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Each participant serves as own control, reducing confounding [44] | Potential for carryover effects from previous treatments [41] |

| Requires smaller sample sizes (60-70% reduction in some cases) [41] | Not suitable for acute or curable conditions [41] |

| Increased statistical power for detecting treatment differences [43] | Longer study duration may increase dropout rates [41] |

| All participants receive active treatment at some point [41] | Complex statistical analysis requiring specialized expertise [45] |

| Ideal for detecting individual response variability [46] | Cannot be used for treatments with permanent effects [44] |

Experimental Evidence and Comparative Data

Exercise Physiology Application

A rigorous crossover study examined individual variability in responses to different exercise training protocols [46]. Twenty-one recreationally active adults completed three weeks of both endurance training (END: 30 minutes at ~65% VO₂peak) and sprint interval training (SIT: eight 20-second intervals at ~170% VO₂peak) in randomized order with a three-month washout period between interventions [46].

The study demonstrated significant inter-individual variability in training responses. While group-level analyses showed main effects of training for VO₂peak, lactate threshold, and submaximal heart rate, individual patterns differed substantially between END and SIT protocols [46]. Using typical error (TE) measurement to define non-response (failing to demonstrate changes greater than 2×TE), researchers identified non-responders for VO₂peak (TE: 0.107 L/min), lactate threshold (TE: 15.7 W), and submaximal heart rate (TE: 10.7 bpm) following both END and SIT [46].

Table 2: Response Rates to Different Exercise Training Modalities [46]

| Outcome Measure | Non-Responders to END | Non-Responders to SIT | Consistent Responders to Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| VO₂peak | Observed | Observed | Pattern differed between protocols |

| Lactate Threshold | Observed | Observed | Pattern differed between protocols |

| Submaximal Heart Rate | Observed | Observed | Pattern differed between protocols |

| Key Finding | All individuals responded in at least one variable when exposed to both END and SIT |

Notably, the study found no significant positive correlations between individual responses to END versus SIT across any measured variable, suggesting that non-response to one training modality does not predict non-response to another [46]. This highlights the value of crossover designs for detecting individual-specific intervention effects that would be obscured in group-level analyses.

Nutritional Intervention Application

A replicate crossover trial investigating dietary nitrate supplementation provides another exemplary application [47]. Fifteen healthy males participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial where they consumed either nitrate-rich beetroot juice (~14.0 mmol nitrate) or nitrate-depleted beetroot juice (~0.03 mmol nitrate) on four separate laboratory visits, with each condition administered twice in randomized order [47].