Dead-End Elimination in Protein Science: A Comprehensive Guide to Side-Chain Prediction and Design

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) algorithm, a foundational and provably accurate method for solving the combinatorial problem of protein side-chain prediction and design.

Dead-End Elimination in Protein Science: A Comprehensive Guide to Side-Chain Prediction and Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) algorithm, a foundational and provably accurate method for solving the combinatorial problem of protein side-chain prediction and design. We explore DEE's core theorem and its evolution, including advanced criteria like minimized-DEE (MinDEE) that incorporate energy minimization for greater accuracy. The scope extends to practical applications in computational protein redesign, drug discovery, and enzyme engineering, alongside a critical evaluation of its performance against other methods. Troubleshooting guidance and a discussion of future directions, such as integration with machine learning and polarizable force fields, are included to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to effectively apply and advance these computational techniques.

The Foundations of Dead-End Elimination: From a Core Theorem to a Dominant Algorithm

Defining the Combinatorial Challenge in Protein Side-Chain Positioning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core combinatorial problem in protein side-chain prediction? The core problem is framed as a combinatorial optimization of a complex energy function over amino acid sequences and their conformations [1]. Given a fixed protein backbone, the goal is to find the set of side-chain conformations (rotamers) that yields the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC). The challenge arises because the number of possible combinations grows exponentially with the number of residues. For example, problems of up to 10^244 combinations for a hydrophobic core design and 10^1044 for a side-chain placement problem have been documented, presenting a computationally intractable problem without specialized algorithms [2].

FAQ 2: Why is the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem central to solving this problem? The Dead-End Elimination theorem provides a powerful condition to identify rotamers that cannot be part of the GMEC [3]. By pruning these "dead-end" rotamers from the search space, DEE dramatically reduces the combinatorial explosion, making it possible to find the optimal solution for systems that would otherwise be unsolvable through exhaustive search. It has been a foundational method in the field for decades [4] [3] [5].

FAQ 3: What are the common sources of error in side-chain prediction, particularly for surface residues? A major source of error is related to solvent accessibility. Polar and charged residues (e.g., ARG, LYS, GLN) with high solvent exposure show increased rotamer prediction errors [6]. These surface side chains have fewer geometric restraints and higher mobility [7]. Furthermore, they tend to adopt high-energy, non-canonical "off" rotamers that are stabilized by solvent interactions, which are difficult for scoring functions to model accurately [6]. Accounting for conformational mobility and crystal packing is crucial for improving the accuracy of surface residue predictions [7].

FAQ 4: My DEE algorithm fails to converge on a solution for large proteins. What strategies can I use?

DEE can be combined with other algorithms to handle larger problems. One effective strategy is to use DEE for an initial, powerful reduction of the search space and then complete the optimization with a complementary algorithm like Branch-and-Terminate (B&T) or A* search [1] [8]. Another modern approach is to frame the problem as a Cost Function Network (CFN) and use solvers like toulbar2, which can incorporate and maintain DEE rules during search, improving efficiency by several orders of magnitude [1]. For very large systems, graph theory methods can decompose the protein into smaller, manageable biconnected components [5].

FAQ 5: How does side-chain conformational variability impact the assessment of prediction programs? Protein side-chain conformation is not always a "single-answer" problem [9]. Quantitative analyses have identified several types of conformational variations in experimental structures, including discrete, cloud, and flexible conformations. This polymorphism means that a single native structure may not represent all biologically relevant states. Therefore, benchmarking prediction programs against a single structure can be misleading. Assessments should consider these variations, using large-scale datasets and potentially accepting multiple correct conformations [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Prediction Accuracy for Surface Residues

Problem: Your side-chain predictions are highly accurate for the protein core but perform poorly on solvent-exposed surface residues.

Solutions:

- Incorporate an entropy-like term: Use the colony energy, a phenomenological term that favors rotamers located in frequently sampled regions of conformational space, effectively smoothing the energy landscape. This approach approximates entropic effects and has been shown to significantly improve prediction accuracy for surface side chains [7].

- Refine hydrogen bond accounting: Implement a detailed hydrogen-bond energy function that considers solvent accessibility. For example, use a term that scales the hydrogen-bond energy based on the fractional solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of the side chain [7].

- Include the crystallographic environment: For predictions meant to match a specific crystal structure, include neighboring protein chains and heteroatoms from the crystal lattice in the energy calculation. This can improve the accuracy of χ1 and χ1+2 predictions for surface side chains to over 80% and 70%, respectively [7].

Guide 2: Managing Computational Complexity and Runtime

Problem: The side-chain prediction calculation is too slow or fails to converge due to combinatorial complexity.

Solutions:

- Employ advanced DEE criteria: Use generalized and extended DEE theorems, such as the Single Split DEE criterion, which can provide an additional ~18% elimination power on top of standard DEE criteria [4]. These generalized algorithms can solve problems that are hundreds of log-units larger than what was previously possible [2].

- Utilize hybrid algorithms: Combine DEE with other methods. Let DEE reduce the problem size as much as possible, then switch to a graph theory-based algorithm (like in SCWRL) [5] or a Branch-and-Terminate (B&T) algorithm to find the solution on the reduced set [8].

- Leverage modern solvers: Model the problem as a Cost Function Network (Weighted CSP) and use a solver like

toulbar2. This approach has been shown to improve upon the DEE/A* method by several orders of magnitude [1].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from the literature to aid in benchmarking and method selection.

Table 1: Performance of Side-Chain Prediction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Reported χ1 Accuracy (%) | Reported χ1+2 Accuracy (%) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCWRL (Graph Theory) | 82.6 [5] | 73.7 [5] | Uses backbone-dependent rotamer library & graph decomposition |

| Method with Colony Energy | 82 (surface residues, with crystal packing) [7] | 73 (surface residues, with crystal packing) [7] | Approximates entropic effects for surface residues |

| Generalized DEE | N/A | N/A | Solves problems of up to 10^1044 combinations [2] |

Table 2: Residue-Specific Rotamer Error Analysis

| Residue Type | Relative Error Tendency | Primary Correlating Factor |

|---|---|---|

| ARG, LYS, GLN | High [6] | High Solvent Accessibility [6] |

| Buried Hydrophobic | Low [7] | Strong packing restraints [7] |

| Surface Polar (H-bonded) | Moderate-High [7] | Participation in specific H-bonds [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Standard DEE/A* Workflow for Protein Design

This protocol outlines the key steps for using DEE and A* search to solve a computational protein design (CPD) problem, reduced to a binary Cost Function Network [1].

- Problem Definition: Define the protein backbone and the set of sequence positions to be designed, along with the allowed amino acid residues and their rotamers at each position.

- Energy Function Definition: Specify the energy function, which typically includes terms for van der Waals interactions, torsional energies, hydrogen bonding, and rotamer probabilities from a backbone-dependent rotamer library [7] [5].

- Dead-End Elimination (DEE): Iteratively apply DEE criteria to eliminate rotamers that cannot be part of the GMEC. Start with basic criteria and proceed to more advanced, computationally expensive ones (e.g., Goldstein, Split DEE) [2] [4].

- Combinatorial Search (A): On the reduced rotamer set, use the A search algorithm to find the global minimum energy conformation. The A* algorithm efficiently explores the remaining combinatorial tree using a heuristic to guide the search [1].

- Validation: Analyze the resulting sequence and structure for stability and function. This may involve molecular dynamics simulations or other validation checks.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking a Side-Chain Prediction Program

This methodology is adapted from large-scale evaluations of prediction accuracy [9] [6].

- Dataset Curation:

- Obtain a non-redundant set of high-resolution protein structures (e.g., better than 2.0 Å resolution).

- Filter to include only single chains to simplify solvent accessibility calculations.

- Apply quality filters: retain only residues with all atoms having B-factors ≤ 40 Ų and occupancies of 1 to ensure coordinate reliability [6].

- Structure Processing:

- Accuracy Calculation:

- For each residue, calculate the absolute difference in dihedral angles (χ1, χ2, etc.) between the predicted and experimental conformations.

- A prediction is considered correct if all calculated χ angles are within 40° of the experimental values [7] [5].

- Report overall accuracy and stratify results by residue type, solvent accessibility, and secondary structure.

- Error Analysis:

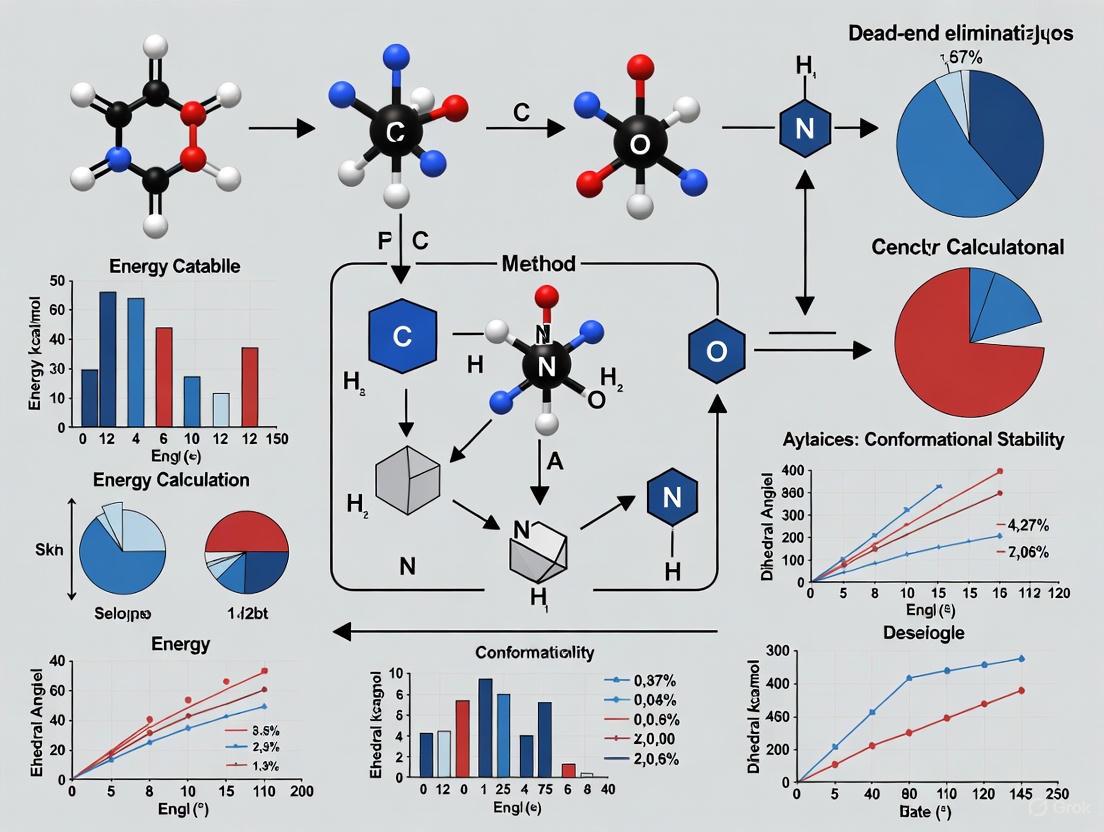

Core Concept Visualization

Diagram 1: DEE Algorithm Flow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Side-Chain Prediction Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Backbone-Dependent Rotamer Library | Provides discrete, statistically derived side-chain conformations based on backbone φ/ψ angles. | Dunbrack library is widely used [6] [5]. |

| Dead-End Elimination (DEE) Algorithm | Prunes the combinatorial search space by eliminating rotamers that cannot be in the GMEC. | Can be implemented with standard and split criteria [4] [3]. |

| Cost Function Network (CFN) Solver | Solves the CPD problem as a Weighted CSP, often with integrated DEE. | toulbar2 solver shows high efficiency [1]. |

| Graph Decomposition | Breaks the residue interaction graph into smaller subproblems for efficient solving. | Used in SCWRL for rapid prediction [5]. |

| Energy Function | Scores rotamer combinations; typically includes van der Waals, torsion, and H-bond terms. | May include specialized terms like colony energy for surface residues [7]. |

Predicting the three-dimensional structure of a protein is a fundamental challenge in computational biology. A critical sub-problem is protein side-chain positioning, which involves finding the optimal spatial arrangements of amino acid side chains given a fixed protein backbone structure. The complexity arises because each side chain can adopt multiple distinct conformations, known as rotamers. The resulting combinatorial explosion makes an exhaustive search computationally intractable for all but the smallest systems. The Dead-End Elimination (DEE) Theorem provides a provable, exact solution to this NP-hard problem by intelligently pruning the conformational search space, guaranteeing to find the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) without enumerating all possibilities [3] [10].

Understanding the Core DEE Theorem

Fundamental Principles and Requirements

The Dead-End Elimination algorithm is a method for minimizing a function over a discrete set of independent variables. For protein structure prediction, it requires four key components [10]:

- A discrete set of independent variables: The rotameric states for each side chain position.

- Precomputed energy values: Energies for individual rotamers and their pairwise interactions.

- Elimination criteria: Mathematical conditions to identify "dead-ending" rotamers that cannot be part of the GMEC.

- An objective function: Typically a physics-based or knowledge-based energy function to be minimized.

The Original DEE Theorem Statement

The original dead-end elimination theorem, as introduced by Desmet et al. in 1992, provides the foundational criterion for identifying rotamers that cannot be members of the global minimum energy conformation [3]. The theorem states that a rotamer ( rk^A ) at position ( k ) can be eliminated if another rotamer ( rk^B ) at the same position exists such that for all possible combinations of the other rotamers in the protein, the following inequality holds:

Original Singles Criterion: [ Ek(rk^A) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \min{X} E{kl}(rk^A, rl^X) > Ek(rk^B) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \max{X} E{kl}(rk^B, rl^X) ]

Where:

- ( Ek(rk^A) ) is the self-energy of rotamer ( A ) at position ( k )

- ( E{kl}(rk^A, r_l^X) ) is the pairwise interaction energy between rotamer ( A ) at position ( k ) and rotamer ( X ) at position ( l )

- ( \min{X} E{kl}(rk^A, rl^X) ) represents the best possible interaction energy ( r_k^A ) can achieve with any rotamer at position ( l )

- ( \max{X} E{kl}(rk^B, rl^X) ) represents the worst possible interaction energy ( r_k^B ) can have with any rotamer at position ( l ) [10]

This criterion effectively states that if rotamer ( rk^A ) is always worse than ( rk^B ) regardless of what other rotamers are chosen throughout the protein, then ( r_k^A ) is a "dead end" and can be eliminated from further consideration.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Reagents for DEE Experiments

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in DEE |

|---|---|---|

| Rotamer Libraries | Provides discrete sets of probable side-chain conformations with associated probabilities [11] | Defines the initial conformational search space for each residue position |

| Energy Functions | Physics-based or knowledge-based potential functions for calculating interaction energies [10] | Scores rotamer self-energies and pairwise interactions to evaluate conformational quality |

| DEE Algorithm Implementation | Computer code implementing DEE criteria and convergence checks [10] | Performs the actual dead-end elimination process to reduce conformational space |

| Tree Decomposition Solver | Algorithm for solving the remaining combinatorial problem after DEE reduction [11] | Finds GMEC in the dramatically reduced search space after DEE pruning |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard DEE Implementation Workflow

Energy Matrix Preparation Protocol

Rotamer Library Selection: Choose an appropriate backbone-dependent rotamer library (e.g., SCWRL4 library, Dunbrack library) [11].

Self-Energy Calculation: For each residue position ( i ) and each rotamer ( r_i^A ), compute:

- Torsional energy components

- Solvation energy terms

- Backbone-dependent energy terms

Pairwise Interaction Matrix Construction: For each pair of residue positions ( (i, j) ) and each rotamer pair ( (ri^A, rj^B) ), compute:

- Van der Waals interactions

- Electrostatic interactions

- Hydrogen bonding potentials

- Desolvation penalties [10]

Energy Matrix Optimization: Implement efficient data structures (sparse matrices) to handle the ( O(N^2p^2) ) memory requirements, where ( N ) is the number of residues and ( p ) is the average number of rotamers per residue [10].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my DEE implementation fail to converge for proteins with more than 100 residues?

Issue: The algorithm stalls or requires excessive memory for larger proteins.

Solution:

- Implement the Goldstein criterion [10] as a more efficient elimination condition: [ Ek(rk^A) - Ek(rk^B) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \min{X} \left(E{kl}(rk^A, rl^X) - E{kl}(rk^B, rl^X)\right) > 0 ]

- Use conformational splitting (Split DEE) which partitions the conformational space more effectively [11]

- Employ sparse matrix storage for pairwise energy terms

- Implement iterative depth control - start with stricter elimination thresholds

FAQ 2: How can I validate that my DEE implementation correctly finds the GMEC?

Verification Protocol:

- Small System Validation: Test on a small peptide (5-10 residues) where exhaustive enumeration is feasible

- Energy Comparison: Ensure the final GMEC energy is lower than any single conformation sampled during elimination

- Backbone Consistency: Validate that predicted side chains have reasonable steric compatibility with the backbone

- Comparison to Crystal Structures: Benchmark against high-resolution X-ray structures with good electron density [11]

Expected Performance Metrics:

- Typical elimination: 85-95% of original rotamers [11]

- χ1 accuracy: 86% within 40° of X-ray positions [11]

- χ1+2 accuracy: 75% within 40° of X-ray positions [11]

FAQ 3: What are the common pitfalls in energy function parameterization?

Common Issues and Solutions:

Table 2: Energy Function Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly Repulsive Van der Waals | Too many clashes, unrealistic compressed structures | Reduce repulsive term scaling, implement soft-core potentials [11] |

| Inadequate Solvation Model | Buried polar residues, exposed hydrophobic residues | Incorporate context-dependent solvation, use Gaussian Exclusion Model [11] |

| Poor Electrostatic Treatment | Incorrect salt bridges, misoriented hydrogen bonds | Implement distance-dependent dielectric, explicit hydrogen bonding potentials |

| Backbone Dependency Errors | Systematic rotamer preference errors | Use backbone-dependent rotamer libraries with kernel density estimates [11] |

FAQ 4: How does DEE performance compare to alternative methods?

Comparative Analysis:

Table 3: DEE vs. Alternative Methods for Side-Chain Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead-End Elimination | Global optimization with provable GMEC [10] | Highest (when converges) [11] | Variable (O(N²p²) to O(N³p³)) [10] | Small to medium proteins, design applications |

| Monte Carlo | Stochastic sampling with thermal fluctuations [3] | Medium-High | Fast, O(Np) per iteration | Large systems, conformational sampling |

| Genetic Algorithms | Evolutionary operators on population [3] | Medium | Medium, depends on population size | Complex landscapes, multi-objective optimization |

| Mean Field Theory | Self-consistent solution of probabilities [10] | Medium | Fast, O(Np²) | Initialization for other methods |

FAQ 5: What are the current limitations of DEE and how are they addressed?

Limitations and Advanced Solutions:

Combinatorial Explosion in Design:

- Problem: Protein design expands the sequence space exponentially

- Solution: Combine DEE with sequence selection algorithms [10]

Backbone Flexibility:

- Problem: Fixed backbone assumption limits accuracy

- Solution: Implement multi-backbone DEE with consensus modeling [11]

Membrane Proteins:

- Problem: Standard energy functions poorly represent membrane environments

- Solution: Develop membrane-specific potentials and solvation terms

Advanced DEE Methodologies

Split DEE Criterion

The Split DEE criterion represents a significant advancement over the original theorem by effectively splitting the conformational space into partitions for more efficient elimination [11]. This approach makes it possible to complete protein design calculations that were previously intractable due to combinatorial explosion.

Split DEE Implementation:

DEE in Protein Design Applications

In protein design applications, the DEE algorithm must consider both conformational and sequence space [10]. The modified algorithm incorporates:

- Sequence-dependent rotamer libraries

- Position-specific amino acid sets

- Compatibility scoring with target backbone

The implementation typically achieves 17.7% additional elimination power beyond standard criteria on test sets of sixty proteins [11].

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Quantitative Elimination Power

Table 4: DEE Elimination Efficiency Across Protein Sizes

| Protein Size (Residues) | Initial Rotamers | Final Rotamers After DEE | Elimination Percentage | Computation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (<50) | 500-1,000 | 25-50 | 95-98% | Seconds to minutes |

| Medium (50-100) | 1,000-5,000 | 100-500 | 90-95% | Minutes to hours |

| Large (100-200) | 5,000-20,000 | 500-2,000 | 85-90% | Hours to days |

| Very Large (>200) | 20,000+ | 2,000+ | 80-85% | Days to weeks |

Prediction Accuracy Standards

For successful side-chain prediction, expect the following accuracy benchmarks when using high-quality input backbones and modern rotamer libraries [11]:

- χ1 angles: 86% within 40° of experimental positions

- χ1+2 angles: 75% within 40° of experimental positions

- Buried residues: >89% χ1 accuracy

- Exposed residues: Variable accuracy depending on flexibility

Higher accuracy is obtained for side chains with higher electron density in reference crystal structures, indicating lower conformational disorder [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the basic requirements for implementing a Dead-End Elimination (DEE) algorithm? A DEE implementation requires four core pieces of information [10]:

- A well-defined finite set of discrete independent variables (e.g., protein side-chain rotamers).

- A precomputed numerical value (the "energy") associated with each variable and their interactions (pairs, triples, etc.).

- Specific mathematical criteria for determining when a variable is a "dead end" and can be eliminated from consideration.

- An objective function (the "energy function") to be minimized.

Q2: What does the total energy function in protein side-chain prediction typically look like? The total energy ((E{TOT})) is a combination of self-energy and interaction energy terms [10]: (E{TOT} = \sum{k} E{k}(r{k}) + \sum{k \neq l} E{kl}(r{k}, r{l})) Here, (N) is the number of residues, (r{k}) is the rotamer at position (k), (E{k}(r{k})) is the self-energy of rotamer (r{k}), and (E{kl}(r{k}, r{l})) is the interaction energy between rotamers (r{k}) and (r{l}).

Q3: My DEE algorithm is not converging or is running slowly. What could be wrong? This is a common troubleshooting scenario. The issue often lies with the initial pruning criteria or the rotamer library. First, ensure your precomputed energy matrices are accurate. Second, start by applying the simpler Singles Elimination Criterion to prune the search space significantly before moving to the more computationally intensive Pairs Elimination Criterion [10]. Third, verify the quality and detail of your rotamer library; a highly detailed library can improve both the accuracy and speed of side-chain modeling [4].

Q4: How does the Goldstein criterion improve upon the basic singles elimination rule? The Goldstein criterion is a refinement that provides greater eliminating power. It arises from algebraic manipulation before applying minimization and is considered a more powerful criterion for identifying dead-end rotamers [10]. The rule states that a rotamer (r{k}^{A}) can be eliminated if there is another rotamer (r{k}^{B}) for the same residue such that the following inequality holds: (E{k}(r{k}^{A}) - E{k}(r{k}^{B}) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \min{X} \left(E{kl}(r{k}^{A}, r{l}^{X}) - E{kl}(r{k}^{B}, r{l}^{X})\right) > 0)

Q5: What are the key differences between using DEE for protein structure prediction versus protein design? In protein structure prediction, the amino acid sequence is fixed, and the goal is to find the side-chain conformations that minimize the energy for a given backbone. In protein design, the sequence itself is variable, and DEE is used to find amino acid sequences that fold into a desired structure [10]. This means the set of possible rotamers at a position includes different amino acid types, vastly increasing the complexity of the combinatorial problem.

Troubleshooting Common DEE Experimental Issues

Problem: Insufficient Elimination Power

- Symptoms: The algorithm fails to reduce the combinatorial search space to a tractable size. The remaining number of rotamer combinations is too large for a final search step.

- Solution Path:

- Verify Implementation of Singles Criterion: Ensure the basic singles elimination criterion is correctly implemented and applied iteratively until no more rotamers can be eliminated [10].

- Implement Pairs Criterion: Proceed to implement and apply the more powerful pairs elimination criterion. This criterion examines pairs of rotamers and can eliminate combinations that seem viable in isolation but are suboptimal when considered together [10].

- Use Advanced Criteria: Incorporate more powerful and general criteria like Conformational Splitting or the Goldstein criterion [10]. These can significantly extend the range of convergence for harder problems.

Problem: Inaccurate Energy Evaluation

- Symptoms: The final predicted side-chain conformations are energetically unstable or do not match expected experimental structures (e.g., from crystallography).

- Solution Path:

- Check Energy Function Parameters: Review the force field or statistical potential parameters used to calculate (Ek) and (E{kl}). Inaccurate parameters lead to incorrect minimization.

- Validate Rotamer Library: Ensure the rotamer library is backbone-dependent and appropriate for the resolution of your prediction task [4]. Using an outdated or oversimplified library is a common source of error.

- Inspect Precomputed Energies: The energy matrices must be precomputed correctly [10]. A bug in this step will propagate through the entire DEE process.

Quantitative Data for DEE Implementation

Table 1: Standard DEE Pruning Criteria and Formulae

| Criterion Name | Mathematical Rule | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Singles Elimination [10] | (E{k}(r{k}^{A}) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \min{X} E{kl}(r{k}^{A}, r{l}^{X}) > E{k}(r{k}^{B}) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \max{X} E{kl}(r{k}^{B}, r{l}^{X})) | Eliminates a single rotamer (r{k}^{A}) if another rotamer (r{k}^{B}) at the same position is always better. |

| Pairs Elimination [10] | (U{kl}^{AB} + \sum{i=1}^{N} \min{X}\left(E{ki}(r{k}^{A}, r{i}^{X}) + E{lj}(r{l}^{B}, r{j}^{X})\right) > U{kl}^{CD} + \sum{i=1}^{N} \max{X}\left(E{ki}(r{k}^{C}, r{i}^{X}) + E{lj}(r{l}^{D}, r{j}^{X})\right)) | Eliminates a pair of rotamers ((r{k}^{A}, r{l}^{B})) if another pair ((r{k}^{C}, r{l}^{D})) is always better. |

| Goldstein Criterion [10] | (E{k}(r{k}^{A}) - E{k}(r{k}^{B}) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \min{X} \left(E{kl}(r{k}^{A}, r{l}^{X}) - E{kl}(r{k}^{B}, r{l}^{X})\right) > 0) | A more powerful version of the singles criterion for increased elimination power. |

Table 2: Representative Scale of DEE Problem Solving Capability

| Problem Type | Combinatorial Complexity | CPU Time to Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Protein Design | 10(^{115}) combinations | < 2 weeks | [2] |

| Hydrophobic Core Design | 10(^{244}) combinations | < 1.5 days | [2] |

| Side-Chain Placement | 10(^{1044}) combinations | ~1 hour | [2] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Basic DEE Cycle for Side-Chain Prediction

This protocol outlines the key methodology for applying DEE to a protein side-chain positioning problem with a fixed backbone [10] [4].

Input Preparation:

- Obtain the protein's atomic coordinates (backbone).

- Assign a set of possible rotamers to each side-chain position using a rotamer library (e.g., a backbone-dependent library [4]).

Energy Matrix Calculation:

- Precompute the self-energy (E{k}(r{k})) for every rotamer at every position. This energy can include terms like torsional strain and van der Waals interactions with the backbone.

- Precompute the pairwise interaction energy (E{kl}(r{k}, r_{l})) for all rotamer pairs between all residue pairs. This is typically the most computationally expensive step.

Iterative DEE Pruning:

- Step A: Apply the Singles Elimination criterion to the entire set of rotamers. Remove all rotamers identified as dead ends.

- Step B: Apply the Pairs Elimination criterion to the remaining set of rotamers and rotamer pairs. Remove all pairs identified as dead ends.

- Iterate: Re-apply the Singles and Pairs criteria to the progressively smaller search space until no more rotamers or pairs can be eliminated (convergence).

Final Search and Validation:

- Perform a final combinatorial search (e.g., by simple enumeration) over the remaining, highly reduced set of rotamer combinations to find the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC).

- Validate the resulting structure by comparing it to a known native structure (if available) or by checking its energetic reasonableness.

Core DEE Algorithm Workflow and Logic

DEE Pruning Logic Decision Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a DEE Implementation

| Item | Function in DEE Implementation |

|---|---|

| Rotamer Library | A curated set of discrete, likely side-chain conformations. Drastically reduces the conformational search space. Can be backbone-independent or, more effectively, backbone-dependent [4]. |

| Force Field / Energy Function | A set of mathematical functions and parameters (e.g., CHARMM [4]) used to calculate the potential energy of a molecular system. It is used to precompute the self and pairwise interaction energies for the DEE criteria. |

| Precomputed Energy Matrices | Look-up tables storing the self-energies ((Ek)) and pairwise interaction energies ((E{kl})) for all rotamers. These matrices are the foundational data upon which the DEE pruning rules operate [10]. |

| DEE Pruning Criteria (Singles, Pairs, etc.) | The core algorithms that perform the combinatorial optimization. They are the logical rules that identify and eliminate suboptimal rotamers and rotamer pairs without evaluating the entire search space [10]. |

| Final Search Algorithm | A method (e.g., exhaustive enumeration, A* search) used to find the global minimum energy conformation from the greatly reduced set of rotamers that survive the DEE pruning process [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a rotamer library and why is it fundamental to side-chain prediction? A rotamer library is a curated collection of statistically probable, discrete conformations of amino acid side chains, derived from experimentally determined protein structures [12]. They are fundamental because the side-chain conformation prediction problem is framed as selecting the correct rotamer combination for a given protein backbone that minimizes the overall energy [12]. By reducing the continuous conformational space to a discrete set of rotamers, these libraries make the computationally complex problem of side-chain packing tractable [3].

Q2: My molecular modeling software (e.g., Rosetta) reports "unrecognized atom" errors when I use a custom rotamer library. What is the most likely cause?

This error frequently occurs due to incorrect atom name formatting in your rotamer library file. The software expects atom names to follow a specific spacing and naming convention (e.g., " N " vs ".N..") [13]. For non-canonical amino acids, ensure your parameter file correctly defines the backbone atoms (N, CA, C, O) and that the POLY_IGNORE list does not accidentally include these critical backbone atoms [13]. Always verify the file format and use dedicated conversion tools to generate library files.

Q3: What is the key difference between backbone-independent and backbone-dependent rotamer libraries?

- Backbone-independent libraries assign rotamer probabilities based only on the amino acid identity, ignoring the local protein structure [12] [14].

- Backbone-dependent libraries significantly improve upon this by conditioning rotamer probabilities on the local backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ), providing a more context-aware and accurate prediction [12] [14].

Q4: How does the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem use rotamer libraries? The Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem is a powerful search algorithm that efficiently prunes the combinatorial space of rotamer combinations. It identifies and eliminates rotamers that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation before the detailed search begins [3]. By integrating a rotamer library with an energy function, DEE can solve large-scale side-chain prediction problems, such as one with 10¹⁰⁴⁴ combinations, in a practical amount of time [2].

Q5: Are small side-chain motions sufficient for accurate protein-ligand docking? Yes, research indicates that for many systems, small, minimal rotations are both necessary and sufficient to achieve accurate dockings. Studies show that most side chains do not shift to a new rotamer upon ligand binding; instead, they undergo small adjustments from their apo conformation to accommodate the ligand [15]. This "minimal rotation hypothesis" is a computationally efficient model that works well, especially when the protein backbone does not undergo large conformational changes [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Accuracy in Side-Chain Predictions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Outdated Rotamer Library:

- Cause: Using a backbone-independent or an old backbone-dependent library that lacks modern contextual information.

- Solution: Upgrade to a state-of-the-art backbone-dependent library (e.g., Dunbrack 2010) or, for higher accuracy, implement a protein-dependent rotamer library. This advanced library type uses the full 3D backbone structure and algorithms like belief propagation to re-rank rotamer probabilities based on the specific spatial environment of each residue [12] [14].

Inefficient Search Algorithm:

- Cause: An exhaustive combinatorial search is infeasible for proteins of even moderate size.

- Solution: Integrate a powerful combinatorial optimizer like the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) algorithm. Generalized DEE theorems can handle extremely hard problems, making large-scale protein design and side-chain placement tractable [2]. Ensure your DEE implementation includes advanced criteria like the "Single Split DEE" for additional elimination power [4].

Inadequate Handling of Flexibility in Docking:

- Cause: Treating the protein receptor as entirely rigid during ligand docking can lead to steric clashes and poor prediction of binding modes.

- Solution: Use docking tools like SLIDE that model protein side-chain flexibility explicitly. These tools allow side chains to rotate as little as necessary to achieve steric complementarity with the ligand, which closely mimics natural binding events [15].

Problem: Errors with Custom Non-Canonical Amino Acid Rotamer Libraries

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Incorrect Parameter File for Polymer Residues:

- Cause: Using a parameter file designed for a small-molecule ligand (without polymer connections) for a residue that is part of the polypeptide chain.

- Solution: When creating a non-canonical amino acid, you must use a polymer-aware parameter file generator (e.g.,

molfile_to_params_polymer.py). This ensures the definition ofUPPER_CONNECTandLOWER_CONNECTatoms, which are crucial for integrating the residue into the protein chain [13].

Incorrect Atom Definitions in the Molfile:

- Cause: The root atom and backbone atoms (

N,CA,C,O) are not properly labeled in the input molfile for the parameter generator. - Solution: Carefully check the molfile tags. The

M ROOTatom must not be listed inM POLY_IGNORE. Correctly defineM POLY_N_BB,M POLY_CA_BB,M POLY_C_BB, andM POLY_O_BBto correspond to the correct atom indices in your structure [13].

- Cause: The root atom and backbone atoms (

Comparison of Rotamer Library Types

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of different generations of rotamer libraries.

| Library Type | Contextual Information | Key Features | Typical Prediction Accuracy | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone-Independent | Amino acid identity only | - First-generation libraries- Limited discriminative power | Lower | Historical context; simple applications |

| Backbone-Dependent | Amino acid identity & local backbone dihedral angles (ϕ, ψ) | - Industry standard for years- Encodes sequentially local information | Medium to High [12] | Homology modeling; general side-chain prediction |

| Protein-Dependent | Full 3D protein backbone structure & spatial neighbor interactions | - Encodes spatially local information- Uses MRF and belief propagation- Re-ranks rotamer probabilities | Significantly higher than backbone-dependent libraries [12] [14] | High-accuracy prediction; protein design |

| Deep Neural Network | Learned features from protein structure data | - No physics-based assumptions- >25% accuracy improvement for aromatic residues [16] | State-of-the-Art [16] | Quality control in crystallography; Cryo-EM assignment |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Side-Chain Prediction using a Protein-Dependent Rotamer Library

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating and using a protein-dependent rotamer library, which significantly improves accuracy over standard libraries without global optimization [12] [14].

- Input. Provide the protein's backbone structure in PDB format.

- Modeling. Model the protein structure as a Markov Random Field (MRF), where each residue is a node and edges represent spatial interactions.

- Energy Function. Employ a knowledge-based energy function (e.g., the SCWRL3 energy function) to define the potentials within the MRF.

- Inference. Perform probabilistic inference using the sum-product belief propagation algorithm on the MRF. This computes the marginal probability distribution for each residue's rotamers, considering the full spatial context.

- Output. The output is a protein-dependent rotamer library, where each rotamer for each residue is associated with a context-aware probability. This library can be used directly for analysis or as a highly informed input for subsequent global search algorithms like DEE.

Protocol 2: Incorporating Flexibility in Docking with the Minimal Rotation Hypothesis

This protocol, based on the docking tool SLIDE, is designed to mimic natural side-chain motions during ligand binding [15].

- Preparation. Obtain the apo (unbound) protein structure and the 3D structure of the small molecule ligand.

- Template Generation. Represent the protein's binding site as a template of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding interaction points.

- Matching and Transformation. Use geometric hashing to find matches between ligand interaction centers and the protein template. Transform the ligand into the binding site based on these matches.

- Induced-Fit Optimization. For each candidate ligand orientation, optimize the complex by allowing small, necessary rotations of protein side chains and ligand torsions to relieve steric clashes. This step prioritizes minimal movements from the starting conformation.

- Scoring and Selection. Score the final protein-ligand complexes based on steric complementarity and interaction energy. The best poses are those that achieve a good fit with minimal conformational change to the protein.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Dunbrack Backbone-Dependent Rotamer Library | A widely adopted standard rotamer library that provides probabilities based on a residue's backbone ϕ and ψ angles [12]. | Serves as the baseline input for many side-chain prediction pipelines and protein design software. |

| SCWRL4 Software | A widely used program for protein side-chain conformation prediction that uses a combination of rotamer libraries and a powerful search algorithm [12]. | Benchmarking side-chain predictions; generating structural models for homology modeling. |

| Dead-End Elimination (DEE) Algorithm | A combinatorial optimization algorithm that prunes rotamers which cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation [2] [3]. | Making large-scale protein design and side-chain placement problems computationally tractable. |

| CABS Coarse-Grained Model | A reduced-representation model for fast Monte Carlo dynamics simulations of protein structure fluctuations and folding [17]. | Studying near-native dynamics, conformational transitions, and flexible molecular docking. |

| SLIDE Docking Software | A docking tool that models protein-ligand interactions by allowing small, induced-fit rotations of protein side chains and ligand flexibility [15]. | Predicting binding modes for ligands when the protein receptor structure is in its apo form. |

Workflow Visualization

Rotamer Library & DEE Research Workflow

Rotamer Library Evolution & Information Context

Advanced DEE Methodologies and Their Transformative Applications in Biomedicine

Dead-End Elimination (DEE) is a cornerstone algorithm in computational structural biology, designed to solve the combinatorial explosion inherent in protein side-chain prediction and design. By efficiently identifying and eliminating rotamers (discrete side-chain conformations) that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC), DEE dramatically reduces the solution space, making it possible to find the optimal arrangement of side chains. The Singles and Pairs Elimination Theorems form the core pruning criteria of this method. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers effectively implement these criteria in their experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind the Dead-End Elimination Theorem?

The DEE theorem provides a condition to identify and eliminate rotamers that cannot be members of the global minimum energy conformation. It operates on the principle that if the energy of a given rotamer, in its best possible environment, is still higher than the energy of an alternative rotamer in its worst possible environment, then the first rotamer is a "dead end" and can be permanently removed from consideration. This effectively controls the computational explosion of the rotamer combinatorial problem [18] [19].

Q2: When should I consider using the Pairs Elimination criterion over the Singles criterion?

The Pairs Elimination criterion is a more powerful, albeit computationally more intensive, extension of the Singles criterion. You should consider employing it when the Singles criterion fails to converge or when it does not eliminate a sufficient number of rotamers to make the problem computationally tractable. The Pairs criterion examines pairs of rotamers simultaneously, allowing for the identification of dead-end combinations that the Singles criterion might miss, thereby significantly enhancing your pruning power [10].

Q3: My DEE algorithm is not converging. What could be the issue?

A common reason for lack of convergence is that the initial rotamer library is too large or contains many rotamers with similar high energies. First, ensure you are applying the Singles and Pairs criteria iteratively until no more rotamers can be eliminated. If convergence remains slow, consider:

- Pre-pruning: Use steric clash checks or energy thresholds to remove obviously unfavorable rotamers before applying formal DEE criteria [20].

- Goldstein Criterion: Implement the enhanced Goldstein criterion, which is a more powerful version of the singles elimination rule, to increase pruning efficiency [10].

- Check Energy Functions: Verify the accuracy and consistency of your precomputed self and pair energies.

Q4: What are the basic requirements for implementing DEE in my protein design pipeline?

An effective DEE implementation requires four key components:

- A well-defined finite set of discrete independent variables (e.g., a rotamer library for each residue position).

- Precomputed numerical values (energies) for each rotamer (self-energy) and for interactions between rotamers (pair energy).

- A criterion (like the Singles or Pairs theorem) for determining when a rotamer is a "dead end."

- An objective function (the total energy function) to be minimized [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow Computational Performance

Symptoms: The DEE cycle (iterative application of Singles and Pairs criteria) takes an excessively long time.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Large rotamer library | Pre-prune rotamers using steric clashes or a high energy threshold relative to the current minimum [20]. |

| Inefficient pair energy calculations | Precompute and store all pairwise interaction energies in a 4D matrix (N2p2) for rapid access during elimination checks [10]. |

| Over-reliance on pairs criterion | Ensure you are applying the simpler, faster singles criterion until it can eliminate no more rotamers before invoking the pairs criterion. |

Problem: Inaccurate or Unexpected GMEC

Symptoms: The final predicted side-chain conformation has unrealistically high energy or appears sterically unreasonable.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inaccurate energy function | Review the parameters of your force field or statistical potential. |

| Overly aggressive pruning | If using pre-pruning, relax the energy or clash thresholds. Verify that the Goldstein criterion is implemented correctly to prevent the premature elimination of viable rotamers [10] [21]. |

| Insufficient rotamer library | Ensure your rotamer library is comprehensive enough to model side-chain flexibility accurately. A library that is too restricted may not contain the true GMEC. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for applying the core DEE pruning criteria. It begins with the initial setup of the protein system and rotamer library, followed by energy calculations. The core iterative process involves applying the singles and pairs elimination theorems to prune the conformational space. This cycle continues until convergence is achieved, at which point the global minimum energy conformation is determined from the remaining set of rotamers.

The table below provides the formal mathematical definitions for the two primary pruning criteria.

Table 1: Core Pruning Theorems of the Dead-End Elimination Algorithm.

| Theorem | Formal Condition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Singles Elimination [10] | E_k(r_k^A) + Σ_{l=1}^N min_X E_kl(r_k^A, r_l^X) > E_k(r_k^B) + Σ_{l=1}^N max_X E_kl(r_k^B, r_l^X) |

Rotamer A at position k can be eliminated if its energy in its best-case scenario is worse than the energy of an alternative rotamer B in its worst-case scenario. |

| Pairs Elimination [10] | U_kl^AB + Σ_{i=1}^N min_X [E_ki(r_k^A, r_i^X) + E_lj(r_l^B, r_j^X)] > U_kl^CD + Σ_{i=1}^N max_X [E_ki(r_k^C, r_i^X) + E_lj(r_l^D, r_j^X)] |

The rotamer pair (A,B) at positions (k,l) can be eliminated if its combined energy in its best-case scenario is worse than the energy of an alternative pair (C,D) in its worst-case scenario. |

Key: E_k: Self-energy of a rotamer. E_kl: Pairwise interaction energy. min_X / max_X: Minimum/Maximum over all possible rotamers at the interacting position. U_kl^AB: Combined self and pair energy for a specific rotamer pair.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key components required for implementing DEE in a protein structure prediction or design experiment.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for DEE Experiments.

| Item | Function in DEE Experiment |

|---|---|

| Rotamer Library | A curated set of discrete, energetically favorable side-chain conformations for each amino acid type; reduces continuous conformational space to a discrete combinatorial problem [18]. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical functions and parameters used to calculate the self-energy (E_k) of a rotamer and the pairwise interaction energy (E_kl) between rotamers [10]. |

| Precomputed Energy Matrix | A data structure (often a 4D matrix) storing all calculated pairwise interaction energies between rotamers of different residues, which is essential for the efficient evaluation of DEE criteria [10]. |

| DEE Software Suite | Implementation of the DEE algorithm (e.g., incorporating Goldstein, Merge-Decoupling) to perform iterative pruning and finally determine the GMEC [20] [2] [21]. |

Advanced Optimization: The Convergence Cycle

For complex problems, achieving convergence requires the iterative application of increasingly powerful criteria. The following diagram illustrates this process, which can involve advanced methods like the Goldstein criterion for deeper singles elimination and the Merge-Decoupling DEE (MD-DEE) for efficient pair-based pruning, ultimately leading to a tractable combinatorial space.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Rotamer Elimination with the Goldstein Criterion

Problem: The standard Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem fails to eliminate a significant number of rotamers, leaving a large combinatorial space that is computationally expensive to search.

Diagnosis: The standard DEE criterion might be insufficient for your protein system. The Goldstein criterion is a more powerful refinement that can eliminate more rotamers by considering energy differences.

Solution: Implement the Goldstein criterion. This criterion identifies a rotamer ( rk^A ) as a dead end if it satisfies the following inequality compared to a candidate rotamer ( rk^B ) for the same residue ( k ): [ Ek(rk^A) - Ek(rk^B) + \sum{l=1}^{N} \min{X} \left( E{kl}(rk^A, rl^X) - E{kl}(rk^B, rl^X) \right) > 0 ] Procedure:

- For a target residue ( k ), select a candidate rotamer ( r_k^B ) (often the current best candidate).

- For every other rotamer ( r_k^A ) of residue ( k ), compute the energy difference term.

- Calculate the sum over all other residues ( l ), and for each, find the minimum value of the pairwise energy difference over all possible rotamers ( r_l^X ) for residue ( l ).

- If the inequality holds, rotamer ( r_k^A ) can be permanently eliminated.

- Iterate the process until no more rotamers can be eliminated.

Verification: After application, the number of remaining rotamers per residue should be significantly reduced. A useful benchmark is a reduction in the total rotamer count by 17-25% beyond what standard DEE achieves [4] [21].

Guide 2: Handling Stagnation in Complex Systems with Conformational Splitting

Problem: The DEE algorithm (even with the Goldstein criterion) stagnates on larger or more complex proteins, failing to find the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC).

Diagnosis: The energy landscape might be too complex for standard criteria to resolve. Conformational splitting introduces a more powerful, albeit computationally intensive, criterion to break these deadlocks.

Solution: Implement the Conformational Splitting DEE criterion. This method "splits" the conformational space to identify dead-end rotamer pairs.

Procedure: The conformational splitting criterion is more complex and operates on pairs of rotamers. A pair of rotamers ( A ) and ( B ) for residues ( k ) and ( l ) (( U{kl}^{AB} )) can be eliminated if there exists another pair ( C ) and ( D ) (( U{kl}^{CD} )) such that: [ U{kl}^{AB} + \sum{i=1}^{N} \min{X} \left( E{ki}(rk^A, ri^{X}) + E{lj}(rl^B, rj^{X}) \right) > U{kl}^{CD} + \sum{i=1}^{N} \max{X} \left( E{ki}(rk^C, ri^{X}) + E{lj}(rl^D, rj^{X}) \right) ] Where ( A \neq C ), ( B \neq D ), and ( k \neq l ).

- Identify Target Pairs: Focus on residue pairs with high interaction energies.

- Compute Splitting Terms: For each candidate rotamer pair ( (A,B) ), calculate the sum over all other residues ( i ), finding the minimum combined interaction energy.

- Find a Superior Pair: Search for an alternative rotamer pair ( (C,D) ) for the same residue pair, and calculate the sum using the maximum combined interaction energy.

- Apply Elimination: If the inequality is satisfied, the pair ( (A,B) ) is a dead-end and can be eliminated.

- Iterate: This process is integrated into the broader DEE cycle until convergence.

Verification: This method should allow the DEE algorithm to proceed towards convergence in previously stalled cases. It has been shown to provide an additional ~17.7% elimination power over standard criteria [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of the Goldstein criterion over the original DEE criterion?

The Goldstein criterion is a stricter, more powerful version of the original singles DEE criterion. It is derived through algebraic manipulation to be a more effective pruning tool. While the original criterion may fail to eliminate many rotamers, the Goldstein criterion can typically remove an additional 17-25% of rotamers, drastically reducing the conformational space that needs to be searched later [10] [21].

FAQ 2: When should I use Conformational Splitting DEE?

Conformational Splitting DEE is a next-line strategy when simpler methods like the Goldstein criterion are insufficient. It is particularly valuable for:

- Large proteins with many interacting side chains.

- Protein design problems where the rotamer library is large.

- Systems where the DEE algorithm fails to converge using only singles elimination. It is more computationally expensive and is often used after applying singles elimination criteria [4].

FAQ 3: Are there even more advanced DEE algorithms?

Yes, research into DEE is ongoing. The Merge-Decoupling DEE (MD-DEE) is one such advancement that works by forming residue-pairs and has been shown to achieve further rotamer reduction after the Goldstein criterion has been applied [21]. Other enhancements focus on graph-theory-based decomposition of the residue interaction graph to solve the remaining combinatorial problem efficiently after DEE pruning [5].

FAQ 4: What are the key reagents and tools for implementing these algorithms?

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for DEE Enhancement

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Rotamer Library | A discrete set of allowed side-chain conformations and their probabilities, derived from statistical analysis of protein structures. It is the foundational "search space" for DEE [5]. |

| Energy Function | A mathematical function calculating the energy of a conformation. It typically includes terms for van der Waals forces, torsion angles, hydrogen bonding, and rotamer probability [7]. |

| Protein Backbone Structure | The fixed atomic coordinates of the protein's main chain (N-Cα-C). This is the scaffold onto which side-chain rotamers are placed and evaluated [10]. |

| DEE Algorithm Core | The software implementation of the basic Dead-End Elimination theorem, which serves as the platform for integrating advanced criteria like Goldstein and Conformational Splitting [10]. |

Workflow and Algorithmic Relationships

Algorithm Enhancement Decision Workflow

Table: Performance Comparison of DEE Enhancement Criteria

| DEE Criterion | Theoretical Basis | Typical Elimination Power Increase | Computational Cost | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Singles DEE | Original elimination theorem [10] | Baseline | Low | Initial pruning for all problems. |

| Goldstein Criterion | Refined inequality based on energy differences [10] | 17% - 25% beyond standard DEE [21] | Moderate | Standard follow-up to basic DEE when more power is needed. |

| Conformational Splitting | Splits conformational space; operates on rotamer pairs [4] | ~17.7% beyond standard criteria [4] | High | Breaking stagnation in complex systems like large proteins or design. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of MinDEE over traditional Dead-End Elimination (DEE)?

Traditional DEE algorithms operate on a rigid-rotamer model, pruning rotamers that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) based on static, pre-computed energies. However, when energy minimization is applied as a post-processing step, the algorithm loses its provable guarantee, as a pruned rotamer might minimize to a lower energy state than the identified rigid-GMEC. MinDEE solves this by incorporating the effects of continuous energy minimization directly into the elimination criteria. This guarantees that the rotamers forming the true, minimized-GMEC are not pruned, making it a provable algorithm for finding the lowest-energy conformation after minimization [22].

Q2: In which specific research applications is MinDEE particularly valuable?

MinDEE is particularly powerful in applications where accurate modeling of side-chain flexibility is critical for predicting molecular function and interactions. Key applications include:

- Protein Redesign: Optimizing protein sequences for novel functions, stability, or catalytic activity by accurately evaluating the combinatorial space of side-chain conformations [22] [23].

- Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding: Improving the accuracy of binding affinity predictions by accounting for side-chain and ligand flexibility upon binding [22].

- Computer-Aided Drug Design: Enabling the more reliable design of small molecules that interact with protein targets with high specificity, by providing a better model of the protein's flexible binding site [22].

- Studying Protein-Protein Interactions: Methods like OPUS-Mut, which rely on side-chain packing favorableness, benefit from the accurate conformational ensembles identified by MinDEE for evaluating interaction interfaces [24].

Q3: My MinDEE calculations are not converging efficiently. What could be the issue?

Slow convergence in MinDEE can stem from several factors. The table below outlines common issues and recommended solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Parameters | Poorly calibrated forcefield or energy parameters. | Validate your energy function on a set of known structures. Adjust van der Waals scaling or electrostatic parameters if necessary. |

| Rotamer Library | Using an undersampled or low-resolution rotamer library. | Switch to a more detailed, backbone-dependent rotamer library to provide a better starting set of conformations for the minimization process. |

| Convergence Criteria | Overly strict convergence tolerances. | Slightly relax the energy tolerance for the MinDEE criterion, as this can significantly speed up pruning without sacrificing critical accuracy. |

Q4: How does the MinDEE algorithm handle continuous rotamer flexibility?

The MinDEE algorithm, and its extension iMinDEE, was developed to move beyond discrete rotamer libraries. While traditional DEE uses a finite set of rigid rotamers, MinDEE considers a continuous space of side-chain conformations. The iMinDEE algorithm performs a local continuous minimization of each rotamer's conformation within a defined region. It then uses these minimized energies in its elimination criteria, allowing it to prune the continuous search space provably while accounting for the fact that side chains can adopt low-energy states between the discrete rotamers in standard libraries [23].

Q5: What are the key differences between the Goldstein criterion and the MinDEE criterion?

The Goldstein criterion is a refinement of the basic DEE singles criterion that increases its pruning power for rigid rotamers through algebraic manipulation. It is more efficient but is still fundamentally designed for a rigid-rotamer model. In contrast, the MinDEE criterion is a novel formulation specifically designed to account for the effects of energy minimization during the pruning process. It guarantees that no rotamers which could be part of the final minimized-GMEC are eliminated, a guarantee the Goldstein criterion cannot provide in a minimization context [22] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Failure to Identify the Native-like Minimum Energy Conformation

Problem: The algorithm converges and reports a GMEC, but this conformation is structurally distant from the known native fold or a validated experimental structure and has an unrealistically high energy.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Reference & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Validate Side-Chain Packing | Use a tool like RosettaHoles to check for voids and poor packing in the core. | A poorly packed core indicates issues with the van der Waals term or rotamer sampling [23]. |

| 2. Check Solvation Effects | Ensure your energy function includes an implicit solvation model or a Generalized Born (GB) term. | Solvation effects are critical for modeling surface residues and electrostatic interactions accurately [23]. |

| 3. Verify Rotamer Library | Use a modern, backbone-dependent rotamer library. | Backbone-dependent libraries provide more accurate prior probabilities for rotamer occurrences, improving the quality of the initial conformational set [25]. |

| 4. Benchmark Forcefield | Test your energy parameters on a set of high-resolution crystal structures. | This ensures your forcefield is correctly calibrated to stabilize native-like conformations over non-native ones [23]. |

Issue: Computationally Prohibitive Runtime for Large Systems

Problem: The MinDEE calculation takes an excessively long time or runs out of memory when applied to large proteins or protein complexes.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Reference & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Apply Pre-filtering | Use a faster, less stringent criterion (like basic DEE or Goldstein) for an initial pass to reduce the rotamer set. | This significantly reduces the conformational space before applying the more computationally intensive MinDEE algorithm [10] [26]. |

| 2. Implement iMinDEE | Use the iMinDEE algorithm, which is specifically optimized for continuous rotamers. | iMinDEE is designed to prune the continuous search space with an efficiency close to that of traditional DEE for rigid rotamers, making larger systems feasible [23]. |

| 3. Strategic System Setup | For very large systems, consider a divide-and-conquer strategy or focus minimization only on critical, flexible regions. | Restricting the minimization to key residues (e.g., an active site or binding interface) can dramatically reduce computational cost while retaining accuracy where it matters most [22]. |

Experimental Protocol: Protein Core Redesign Using MinDEE

This protocol outlines the key steps for using the MinDEE algorithm to redesign the core of a protein for enhanced thermostability.

Objective: To identify a sequence and its corresponding side-chain conformation that stabilizes the protein's core, using the MinDEE algorithm to ensure the identified global minimum is valid after energy minimization.

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Methodology

System Preparation:

- Obtain the starting protein backbone structure (e.g., from PDB: 1EY0, 2LZM).

- Define the "core" residues to be redesigned. This is typically done by calculating relative solvent accessibility, selecting residues with less than 5-10% exposure.

Rotamer and Sequence Setup:

- Load a detailed, backbone-dependent rotamer library (e.g., the Penultimate Rotamer Library).

- For each core position to be redesigned, specify the set of allowed amino acid identities. This often restricts choices to hydrophobic residues (e.g., Val, Leu, Ile, Phe, Tyr, Trp, Met).

Energy Pre-computation:

- Calculate the self-energy for each rotamer and the pairwise interaction energies between all rotamers on different residues. This generates the energy matrices required for DEE.

- The energy function should include terms for van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, and solvation.

Pruning with MinDEE:

- First, apply the traditional DEE or Goldstein criterion to eliminate a large fraction of obviously suboptimal rotamers. This step is crucial for efficiency.

- Then, apply the MinDEE criterion iteratively. MinDEE will prune rotamers that cannot be part of the minimized-GMEC, using an energy function that incorporates local minimization.

Identification of GMEC:

- After MinDEE pruning, the remaining conformational space is vastly reduced. The exact minimized-GMEC is identified from this set.

- The output is the optimal sequence and the side-chain conformation for that sequence, which is the global minimum after energy minimization.

Experimental Validation:

- The top-ranked designed sequences should be synthesized and experimentally characterized.

- Key experiments include:

- Thermal Denaturation: Measure the melting temperature (Tm) to confirm increased thermostability.

- X-ray Crystallography: Solve the crystal structure of the designed protein to verify that the predicted side-chain packing matches the experimental electron density.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential computational tools and resources for conducting research with the MinDEE algorithm.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Backbone-dependent Rotamer Library | Provides discrete, low-energy side-chain conformations as a starting point for the search. | Libraries are derived from high-resolution crystal structures; examples include the Penultimate Rotamer Library and the Dunbrack Library [26]. |

| iMinDEE Software | The core algorithm that performs the provable search for the minimized-GMEC. | An extension of DEE that guarantees the identification of the global minimum energy conformation after continuous minimization of side chains [23]. |

| All-Atom Energy Function | Scores the quality of a side-chain conformation by evaluating steric, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions. | Typically includes van der Waals, solvation, torsion angle, and electrostatic terms. Must be differentiable for minimization [22] [23]. |

| OPUS-Mut | A side-chain modeling method used for scoring protein-protein interactions and docking poses. | Useful for evaluating the success of a design by assessing the packing favorableness at protein-protein interfaces [24]. |

Application in Computational Protein Redesign and Novel Enzyme Engineering

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

What is the core principle of Dead-End Elimination (DEE) in protein side-chain prediction?

Dead-End Elimination (DEE) is a theorem-based algorithm that reduces the combinatorial complexity of protein side-chain conformation prediction by systematically identifying and eliminating rotamers that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC). The fundamental principle is that if the energy of a rotamer for a residue is always higher than another rotamer of the same residue when all possible combinations of other residues are considered, the higher-energy rotamer can be "eliminated" from the search space. This pruning process dramatically improves computational efficiency while guaranteeing that the GMEC is preserved [27].

How does DEE integrate with broader protein redesign frameworks like IPRO?

The Iterative Protein Redesign and Optimization (IPRO) framework utilizes DEE as a core component for rotamer optimization during its iterative cycles. In IPRO, a local backbone perturbation is first applied. Then, within a redesign window, DEE and other optimization techniques identify optimal residue mutations and rotamer combinations. This is followed by backbone relaxation and ligand redocking. The framework has been extended to handle specificity redesign by solving a two-level optimization problem that simultaneously minimizes binding energy for desired ligands while constraining binding energy for competing ligands to remain above a threshold [28].

Algorithmic and Computational Troubleshooting

| Common Challenge | Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to converge | Overly large rotamer library; insufficient DEE pruning [27]. | Monitor rotamer elimination rate per iteration. | Use improved DEE criteria (e.g., MinDEE for minimized energies) or divide-and-conquer strategies [27]. |

| Inaccurate GMEC identification | Use of a scoring function with poor discriminatory power [29]. | Compare predicted vs. crystal structure for a single residue on a fixed backbone [29]. | Re-optimize scoring function weights on a high-resolution training set [29]. |

| Low prediction accuracy for surface residues | Inadequate treatment of solvation and electrostatic effects [30]. | Analyze accuracy by residue environment (buried, surface, interface). | Incorporate a solvation energy term and use a variable dielectric model to improve polarization treatment [31] [29]. |

| Long computation times for large proteins | Combinatorial explosion of rotamer combinations. | Profile computation time versus number of residues and rotamers per residue. | Implement a graph-based decomposition of side-chain clusters or use faster search algorithms like Monte Carlo with simulated annealing [30]. |

Which specific DEE improvements can address slow computation times in large-scale redesign?

Provably accurate enhancements to the classic DEE algorithm can yield speedups of more than a factor of 1000. Key improvements include more efficient pruning criteria and the development of divide-and-conquer strategies that break the large optimization problem into smaller, more manageable subproblems. These advanced DEE algorithms have been successfully applied to the redesign of proteins like Gramicidin Synthetase A, plastocyanin, and protein G [27].

Scoring Function and Modeling Optimization

What should I do if my side-chain predictions are inaccurate even with an extensive rotamer library?

Evidence suggests that the scoring function, not the search strategy or library size, is often the main obstacle to accurate side-chain modeling [29]. If you are using a standard force field like CHARMM or AMBER without modification, it may not be optimal for the discrete rotamer-based search. Develop and optimize a dedicated scoring function. One optimized function includes terms for contact surface, volume overlap, backbone dependency, electrostatic interactions, and desolvation energy. The weights of these terms were optimized by minimizing the average RMSD between predicted and true conformations in high-resolution structures, achieving 87.9% χ1 accuracy and 1.34 Å overall RMSD in full-protein prediction tests [29].

How do I model the effects of the protein's internal dielectric environment on side-chain packing?

The internal dielectric constant within a protein is not uniform. Using a single, fixed value can reduce prediction accuracy. Implementing a variable dielectric model that allows the internal dielectric constant to vary as a function of the interacting residues can lead to qualitative improvements. This model has been shown to reduce errors in lysine side-chain predictions by 40%, increasing accuracy from 62.6% to 76.8%. It also substantially improves the accuracy of loop predictions [31].

Experimental Validation and Practical Application

What are the key reagents and computational tools for a protein redesign pipeline?

The table below lists essential components for setting up a computational protein redesign experiment focused on altering ligand specificity.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Structure | Serves as the initial template for redesign (e.g., from PDB). | The crystal structure of AraC (PDB: ...) was used as the starting point for effector specificity redesign [28]. |

| Rotamer Library | A discrete set of probable side-chain conformations. | Backbone-dependent libraries (e.g., Dunbrack library) are commonly used by programs like SCWRL4 and Rosetta [30]. |

| IPRO Framework | An iterative computational framework for protein redesign. | Used to redesign the effector binding specificity of the AraC transcriptional regulator [28]. |

| DEE/MinDEE Algorithm | The core algorithm for pruning the rotamer search space. | Essential for efficiently finding the GMEC in designs; MinDEE is used when energy minimization is incorporated [27]. |

| Structural Water Molecules | Explicitly modeled water molecules that mediate hydrogen bonds. | Critical for accurate ligand docking in the AraC binding pocket, reducing RMSD from 3.53 Å to 0.20 Å [28]. |

Figure 1: Dead-End Elimination (DEE) Basic Workflow

Figure 2: Iterative Protein Redesign and Optimization (IPRO) Cycle

How do I validate a computationally redesigned enzyme before moving to wet-lab experiments?

Before experimental validation, perform extensive in silico characterization:

- Binding Affinity Calculations: Use the final scoring function to calculate the binding energy for both the target and competing ligands. A successful design should show a significantly improved (lower) binding energy for the target and a worsened (higher) energy for competitors [28].

- Specificity Analysis: Ensure the difference in binding energies (ΔΔG) between desired and undesired ligands is large enough to suggest functional specificity.

- Structural Inspection: Visually inspect the final model to ensure the designed mutations create sensible steric and chemical interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, salt bridges) with the target ligand and that no major steric clashes are introduced.

- Backbone Flexibility: Check if critical residues for the protein's mechanical function (e.g., the N-terminal arm in AraC) have been inadvertently mutated, which could disrupt the coupling between binding and function [28].

Driving Discovery in Drug Design and Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem and how does it relate to protein-ligand docking?

The Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem is a method designed to solve the combinatorial explosion problem in protein side-chain prediction by identifying and eliminating rotamers (side-chain conformations) that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) [3]. In the context of drug design, this is crucial because accurately predicting the structure of a protein's binding site, including side-chain orientations, is a fundamental step for reliable protein-ligand docking [32]. DEE makes the computational challenge of side-chain placement tractable, which directly improves the accuracy of predicting how a small molecule (ligand) will bind to a protein target [33].

FAQ 2: My docking poses are inaccurate despite using a high-resolution protein structure. What could be wrong?

Inaccurate poses often result from improper handling of protein and ligand flexibility. The side chains in your protein's binding site might not be in the optimal conformation for the ligand you are docking [32]. Solution: Consider using a protocol that includes side-chain prediction and packing, for instance, by employing a DEE-based algorithm to find the GMEC for the side chains around the binding pocket before performing the docking calculation [3] [11]. This ensures the protein's receptor structure is more realistically modeled for the specific ligand.

FAQ 3: How can I efficiently sample the vast conformational space of a ligand in a large or shallow binding site?

Traditional atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can be computationally prohibitive for this task [34]. Solution: Consider using a coarse-grained (CG) force field like Martini [34]. This approach unites groups of atoms into single interaction sites, dramatically increasing sampling speed. It has been successfully used for unbiased millisecond sampling of protein-ligand interactions, accurately identifying binding pockets and pathways without prior knowledge, which is ideal for challenging binding sites like those at the protein-lipid interface [35] [34].

FAQ 4: Why is my virtual screening yielding many false positives? How can I improve the enrichment of my results?

False positives in virtual screening are frequently due to limitations in the scoring functions used to estimate binding affinity [32]. These functions often struggle to accurately capture the delicate balance of energetic contributions, such as hydrophobic effects, electrostatic interactions, and entropy [32]. Solution: Do not rely on a single scoring function. Implement a consensus scoring approach or follow up top hits with more rigorous, albeit computationally expensive, free energy calculations. For targets where ligands bind at the protein-lipid interface, ensure your scoring function or protocol accounts for the ligand's requirement to first partition into the membrane [35].

Troubleshooting Guides