Decoding Hypoxia Tolerance: From Molecular Sensors to Therapeutic Innovations

This review synthesizes current research on the physiological and molecular mechanisms of hypoxia tolerance, a critical area for understanding disease pathology and developing therapeutic interventions.

Decoding Hypoxia Tolerance: From Molecular Sensors to Therapeutic Innovations

Abstract

This review synthesizes current research on the physiological and molecular mechanisms of hypoxia tolerance, a critical area for understanding disease pathology and developing therapeutic interventions. We explore the foundational biology, including the central role of the HIF signaling pathway and associated metabolic reprogramming. The article details methodological approaches for assessing tolerance and the therapeutic potential of hypoxic preconditioning. It further addresses challenges in translating basic research and compares adaptive strategies across species and pathological contexts. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis highlights emerging biomarkers, innovative therapeutic strategies, and future directions for targeting hypoxia-driven processes in cancer, inflammatory diseases, and ischemia.

Core Molecular Sensors and Signaling Pathways in Oxygen Sensing

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) serves as the central transcriptional regulator of cellular adaptation to oxygen deprivation, a master switch controlling the molecular response to hypoxic stress. Since its initial identification in 1995 as a heterodimeric transcription factor, HIF-1 has emerged as a critical mediator of physiological and pathological processes [1]. This transcription factor orchestrates the expression of hundreds of genes that collectively enhance oxygen delivery, facilitate metabolic adaptation, and promote cell survival under hypoxic conditions. The sophisticated regulation of HIF-1α occurs through oxygen-dependent and independent mechanisms, with its dysfunction implicated in numerous pathologies, particularly cancer [1] [2]. Within solid tumors, hypoxic regions develop due to rapid proliferation and inadequate vascular supply, creating a microenvironment where HIF-1α drives angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion [3] [4]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of HIF-1α molecular regulation, physiological functions, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic targeting strategies, framed within the broader context of hypoxia tolerance research for scientific and drug development professionals.

Molecular Mechanisms of HIF-1α Regulation

Structural Organization and Isoforms

HIF-1 is a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of an oxygen-regulated HIF-1α subunit and a constitutively expressed HIF-1β subunit (also known as ARNT) [4]. The HIF family includes three alpha subunits (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α) each with distinct expression patterns and functions. HIF-1α mediates responses to acute hypoxia, while HIF-2α and HIF-3α dominate during chronic hypoxia [3]. Structurally, HIF-1α contains several critical domains: a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain for DNA binding and dimerization, PER-ARNT-SIM (PAS) domains facilitating heterodimerization, an oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD), and two transactivation domains (TAD-N and TAD-C) [4].

Table: HIF-1α Structural Domains and Functional Characteristics

| Domain | Position | Function | Regulatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| bHLH | N-terminal | DNA binding & dimerization | Constitutive activity |

| PAS | Adjacent to bHLH | Heterodimerization with HIF-1β | Structural stabilization |

| ODDD | Central region | Oxygen-sensitive degradation | Proline hydroxylation by PHDs |

| TAD-N | N-terminal | Transcriptional activation | Oxygen-independent regulation |

| TAD-C | C-terminal | Transcriptional activation | Asparagine hydroxylation by FIH-1 |

Oxygen-Dependent Regulation

Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α undergoes rapid proteasomal degradation through an exquisite oxygen-sensing mechanism. Prolyl-4-hydroxylases (PHD1-3) hydroxylate specific proline residues (P402 and P564) within the ODDD domain using oxygen as an essential co-substrate [1] [2]. This hydroxylation creates a recognition site for the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL), which recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that polyubiquitinates HIF-1α, targeting it for proteasomal degradation with a remarkably short half-life of 6-8 minutes [1]. Simultaneously, factor-inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH-1) hydroxylates an asparagine residue (N803) within the C-TAD domain, preventing recruitment of transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP [1] [4]. Under hypoxic conditions, both PHD and FIH-1 activity decreases due to limited oxygen availability, leading to HIF-1α stabilization, nuclear translocation, heterodimerization with HIF-1β, and transcriptional activation of target genes [1] [2].

Oxygen-Independent Regulation

HIF-1α stability and activity can be modulated through multiple oxygen-independent mechanisms, particularly in pathological conditions like cancer. Genetic alterations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors, including PTEN, p53, and AKT, can enhance HIF-1α protein synthesis [1]. Additionally, growth factor signaling through receptor tyrosine kinases activates PI3K-AKT-mTOR and MAPK pathways, increasing HIF-1α translation [2]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were historically proposed as regulators of HIF-1α stability, though recent evidence using advanced peroxide reporters suggests mitochondrial ROS may be dispensable for hypoxic HIF-1α stabilization, favoring a model where mitochondria contribute primarily as oxygen consumers [5]. Post-translational modifications including acetylation, SUMOylation, and phosphorylation further fine-tune HIF-1α activity and protein interactions [2].

HIF-1α Transcriptional Program and Physiological Functions

Genomic Targets and Adaptive Responses

HIF-1 activates a diverse transcriptional program encompassing hundreds of genes that collectively enable cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Through binding to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) in promoter/enhancer regions, HIF-1 coordinates processes including angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, erythropoiesis, pH regulation, cell survival, and invasion [2]. Key target genes include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for angiogenesis, erythropoietin (EPO) for erythropoiesis, glucose transporters (GLUT1, GLUT3) and glycolytic enzymes for metabolic adaptation, carbonic anhydrase IX for pH regulation, and matrix metalloproteinases for extracellular matrix remodeling [2] [6].

Table: Major HIF-1α Target Genes and Functional Categories

| Functional Category | Representative Target Genes | Physiological Role |

|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis | VEGF, VEGFR1 | Blood vessel formation |

| Metabolic Reprogramming | GLUT1, GLUT3, HK2, LDHA | Glucose uptake & glycolysis |

| Erythropoiesis | EPO | Red blood cell production |

| pH Regulation | CA9, MCT4 | Intracellular pH homeostasis |

| Extracellular Matrix | MMP2, MMP9, FN1 | Matrix remodeling & invasion |

| Cell Proliferation/Survival | IGF2, TGF-α | Growth & apoptosis resistance |

| Inflammation/Immunity | TNFα | Immune cell recruitment |

Pathological Functions in Cancer

In the tumor microenvironment, HIF-1α activation drives multiple hallmarks of cancer progression. HIF-1α promotes angiogenesis through VEGF induction, though the resulting vasculature is often disorganized and leaky, further exacerbating hypoxia [4]. Metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis (the Warburg effect) enables cancer cell survival in hypoxic conditions while generating lactate that acidifies the microenvironment and suppresses immune cell function [3] [4]. HIF-1α enhances invasive and metastatic potential by upregulating matrix metalloproteinases (particularly MMP-9) and the MET receptor tyrosine kinase, facilitating extracellular matrix degradation and tumor cell dissemination [6]. Furthermore, HIF-1α creates an immunosuppressive microenvironment by upregulating PD-L1, recruiting regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and polarizing macrophages toward an M2 phenotype [4]. These coordinated processes establish HIF-1α as a critical mediator of tumor progression and therapeutic resistance.

Experimental Methodologies for HIF-1α Research

Stabilization and Detection Protocols

Hypoxia Induction Systems: For in vitro studies, specialized hypoxia workstations or modular incubator chambers are utilized to maintain precise oxygen concentrations (typically 0.1-5% O₂). Chemical hypoxia mimetics including cobalt chloride (CoCl₂, 100-400 μM), desferrioxamine (DFO, 100-300 μM), and dimethyloxallyl glycine (DMOG, 1 mM) inhibit PHD activity and stabilize HIF-1α under normoxic conditions [1].

Protein Extraction and Western Blotting: Due to rapid degradation, HIF-1α requires specialized protein extraction techniques. Cells should be lysed directly in pre-warmed SDS buffer containing protease inhibitors (Complete Mini EDTA-free tablets) and PHD inhibitors (1 mM DMOG). Standard protocols involve SDS-PAGE (4-12% Bis-Tris gels), transfer to PVDF membranes, blocking with 5% BSA in TBST, and immunoblotting with anti-HIF-1α antibodies (mouse monoclonal [H1alpha67] or rabbit polyclonal). Hif-1β serves as a loading control for the heterodimerization complex [6].

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry: For cellular localization studies, cells are fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked with 5% normal serum, and incubated with primary antibodies against HIF-1α overnight at 4°C. Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488/594) enable visualization by confocal microscopy. For tissue samples, antigen retrieval using citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95-100°C for 20 minutes is essential prior to antibody incubation [6].

Functional Activity Assays

Luciferase Reporter Systems: The HIF-1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODD) fused to luciferase provides a sensitive quantitative reporter. Cells transfected with ODD-luciferase constructs are exposed to experimental conditions, followed by luminescence measurement. This system demonstrates high dynamic range and correlates well with endogenous HIF-1α protein levels and target gene expression [5].

Gene Expression Analysis: Quantitative RT-PCR of established HIF-1 target genes (BNIP3, ENO2, VEGF, CA9) validates transcriptional activity. RNA is extracted using TRIzol reagent, reverse transcribed, and amplified with SYBR Green chemistry. Reference genes (GAPDH, β-actin) control for RNA input and reverse transcription efficiency [5].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP): To directly assess HIF-1α binding to genomic targets, crosslink cells with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes, quench with glycine, sonicate chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments, immunoprecipitate with HIF-1α antibody, and analyze bound DNA fragments by qPCR using primers spanning HREs in promoter regions of target genes [2].

In Vivo Metastasis Models

The functional role of HIF-1α in metastasis has been elucidated using specialized in vivo models. In experimental metastasis assays, 5×10³ to 1×10⁶ HIF-1α-deficient or control tumor cells (e.g., L-CI.5s murine T-lymphoma or CT-26L colon carcinoma) are injected intravenously into syngeneic immunocompetent mice [6]. Animals are sacrificed at predetermined endpoints (hours to weeks), organs are harvested, and metastatic burden quantified through X-gal staining of lacZ-tagged cells, histological analysis (H&E staining), or immunohistochemistry. For spontaneous metastasis models, cells are implanted orthotopically or intradermally, primary tumors are measured regularly with calipers, and metastases analyzed after primary tumor resection or at endpoint [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for HIF-1α Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α Inhibitors | PX-478 (inhibits translation), EZN-2968 (antisense oligonucleotide), Acriflavine (disrupts HIF-1α/p300 interaction) | Mechanistic studies & therapeutic targeting [3] |

| PHD Inhibitors | DMOG, FG-4592, Adaptaquin (AQ) | Stabilize HIF-1α under normoxia for experimental manipulation [5] |

| Antibodies | Anti-HIF-1α (H1alpha67), anti-HIF-1β, anti-pVHL, anti-hydroxy-HIF-1α | Western blotting, immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry [6] |

| Cell Lines | SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma, L-CI.5s murine T-lymphoma, CT-26L colon carcinoma | In vitro & in vivo hypoxia models [6] [5] |

| Reporter Systems | ODD-luciferase constructs, HRE-driven fluorescent reporters | Quantitative assessment of HIF-1α stabilization & activity [5] |

| Animal Models | Immune-competent syngeneic mice (DBA/2, BALB/C) | Metastasis studies & therapeutic evaluation [6] |

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Implications

HIF-1α Inhibitor Development

Targeting HIF-1α represents a promising therapeutic strategy, particularly for overcoming treatment resistance in cancer. Multiple inhibitor classes have been developed with distinct mechanisms of action. Small molecule inhibitors including PX-478 suppress HIF-1α translation, while EZN-2968 is an antisense oligonucleotide that targets HIF-1α mRNA [3]. Natural compounds like acriflavine directly disrupt the HIF-1α-p300 interaction, preventing transactivation of target genes [3]. Computational approaches using machine learning models (random forest, SVM, XGBoost) combined with molecular docking and dynamics simulations have identified novel potential HIF-1α inhibitors from natural product libraries, including Arnidiol and Epifriedelanol [7]. Combination therapies pairing HIF-1α inhibitors with conventional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy demonstrate enhanced efficacy by counteracting hypoxia-driven resistance mechanisms [3].

Combination Therapy Strategies

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment driven by HIF-1α activation contributes significantly to treatment resistance across multiple modalities. HIF-1α promotes chemoresistance through upregulation of drug efflux pumps (P-glycoprotein), enhancement of DNA repair capacity, and inhibition of apoptosis [3]. In radiotherapy, HIF-1α contributes to radioresistance as oxygen is essential for radiation-induced DNA damage fixation [3]. Immunotherapy resistance emerges through HIF-1α-mediated upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules (PD-L1), recruitment of immunosuppressive cells (Tregs, MDSCs), and creation of metabolic barriers that impair cytotoxic T cell function [4]. Combining HIF-1α inhibitors with established treatment modalities represents a promising approach to overcome these resistance mechanisms, with numerous clinical trials currently evaluating this strategy [3] [4].

HIF-1α stands as a master regulator of cellular hypoxia response, coordinating a sophisticated transcriptional program that enables adaptation to oxygen deprivation. Its regulation through oxygen-dependent hydroxylation and proteasomal degradation represents a fundamental physiological mechanism, while its pathological activation in cancer and other diseases highlights its therapeutic significance. Advanced experimental methodologies including sensitive reporter systems, genetic manipulation approaches, and sophisticated in vivo models continue to elucidate the complex functions of HIF-1α in hypoxia tolerance. Ongoing development of HIF-1α-targeted therapeutics, particularly in combination with conventional treatments, holds substantial promise for overcoming therapy resistance mediated by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. For research and drug development professionals, continued investigation into HIF-1α biology and inhibition strategies remains crucial for advancing our understanding of hypoxia tolerance and developing more effective interventions for cancer and other hypoxia-associated diseases.

The cellular response to hypoxia is precisely orchestrated by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway, with prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs) and factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) acting as primary oxygen sensors. This technical guide elucidates the hierarchical relationship between these hydroxylases, which creates a graded response system to diminishing oxygen availability. Through their differential oxygen sensitivities, PHDs and FIH sequentially regulate HIF-1α stability and transcriptional activity, enabling cells to fine-tune adaptive processes including angiogenesis, metabolism, and survival. Understanding this sophisticated regulatory mechanism provides critical insights for physiological adaptations to hypoxia and reveals therapeutic opportunities for ischemic diseases, cancer, and other pathologies characterized by oxygen dysregulation. This review integrates current molecular knowledge with experimental approaches, offering researchers a comprehensive framework for investigating hypoxia sensing mechanisms.

In mammalian cells, the master regulator of oxygen homeostasis is hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of an oxygen-sensitive HIF-1α subunit and a constitutively expressed HIF-1β subunit [8] [1]. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is continuously synthesized but rapidly degraded, maintaining negligible steady-state levels. Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α accumulates, translocates to the nucleus, dimerizes with HIF-1β, and activates hundreds of genes involved in adaptive physiological responses [1]. These genes coordinate diverse processes including angiogenesis (VEGF), erythropoiesis (EPO), glucose metabolism (GLUT1), and cell survival (BNIP3), making the HIF pathway central to both normal physiology and disease pathogenesis [8] [1].

The oxygen-sensing mechanism revolves around the enzymatic activity of Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent dioxygenases that use molecular oxygen as a substrate [1]. The prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHD1-3, also known as EGLN1-3) and factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) constitute the primary oxygen sensors that post-translationally modify HIF-1α in an oxygen-dependent manner [1] [9]. PHDs catalyze the hydroxylation of specific proline residues (Pro402 and Pro564 in HIF-1α) within the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD), while FIH catalyzes the hydroxylation of an asparagine residue (Asn803) in the C-terminal transactivation domain (CAD) [1]. These hydroxylations have distinct functional consequences that are sequentially engaged as oxygen availability declines, enabling cells to mount appropriately graded hypoxic responses.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hierarchical Hydroxylase Activity

Differential Oxygen Affinities Create a Two-Tiered Sensing System

The hierarchical regulation of HIF-1α by PHDs and FIH stems from their fundamentally different oxygen sensitivities, characterized by their Michaelis constants (K~m~) for oxygen [1]. PHDs have a relatively high K~m~ for oxygen (approximately 100-250 µM O₂), making them effective sensors in the normoxic to mildly hypoxic range (∼1-5% O₂) [1]. In contrast, FIH has a significantly lower K~m~ for oxygen (approximately 90 µM O₂), maintaining its activity under more severe hypoxia where PHD activity is already substantially diminished [1]. This differential affinity creates a two-tiered regulatory system that sequentially controls HIF-1α function as oxygen tension declines.

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters of HIF Hydroxylases

| Hydroxylase | Target Residue on HIF-1α | Functional Consequence | Approximate K~m~ for O₂ | Activity Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHD2 | Pro402, Pro564 | Proteasomal degradation via pVHL | 100-250 µM | Inactivated in mild hypoxia (∼1-5% O₂) |

| FIH | Asn803 | Impaired coactivator recruitment | ∼90 µM | Inactivated in severe hypoxia (<1% O₂) |

The sequential engagement of these hydroxylases results in distinct activation states of HIF-1α along the oxygen gradient [1]. Under normoxia, both PHD and FIH are fully active, leading to continuous HIF-1α degradation and suppression of its transcriptional activity. As oxygen tension decreases into the mildly hypoxic range (∼1-5% O₂), PHD activity declines first, allowing HIF-1α protein stabilization and nuclear translocation. However, FIH remains active in this range, hydroxylating Asn803 and thereby limiting the transcriptional potency of the accumulated HIF-1α by blocking its interaction with transcriptional coactivators p300/CBP [1]. Only under more severe hypoxia (<1% O₂) does FIH activity decline, permitting full transcriptional activation of HIF-1α target genes [1]. This sophisticated regulatory mechanism enables cells to fine-tune their hypoxic response according to the severity of oxygen deprivation.

Structural Basis for Hydroxylase Specificity and Function

The molecular structures of PHDs and FIH determine their substrate specificity and functional outcomes. PHD2, the most important regulator of HIF-1α stability among the three PHD isoforms, contains a catalytic domain that recognizes the LXXLAP motif in HIF-1α's ODDD [10]. Notably, PHD2 also possesses an N-terminal zinc finger domain of the MYND type, which we have previously proposed recruits PHD2 to the HSP90 pathway to promote HIF-α hydroxylation [10]. This zinc finger can function as an autonomous recruitment domain to facilitate interaction with HIF-α, and ablation of zinc finger function by a C36S/C42S Egln1 knock-in mutation results in upregulation of the erythropoietin gene, erythrocytosis, and augmented hypoxic ventilatory response - all hallmarks of Egln1 loss of function and HIF stabilization [10].

FIH, while also belonging to the 2OG-dependent oxygenase family, displays distinct structural characteristics that enable its specific recognition of the HIF-1α CAD domain [11]. The FIH active site contains aromatic residues, including Trp296, positioned within 5Å of the iron center [11]. In the absence of HIF-α, O₂-activation in FIH becomes uncoupled, leading to self-hydroxylation at Trp296 and formation of a purple Fe(III)-O-Trp chromophore - this alternative reactivity may affect human hypoxia sensing by potentially regulating FIH availability under prolonged hypoxia [11].

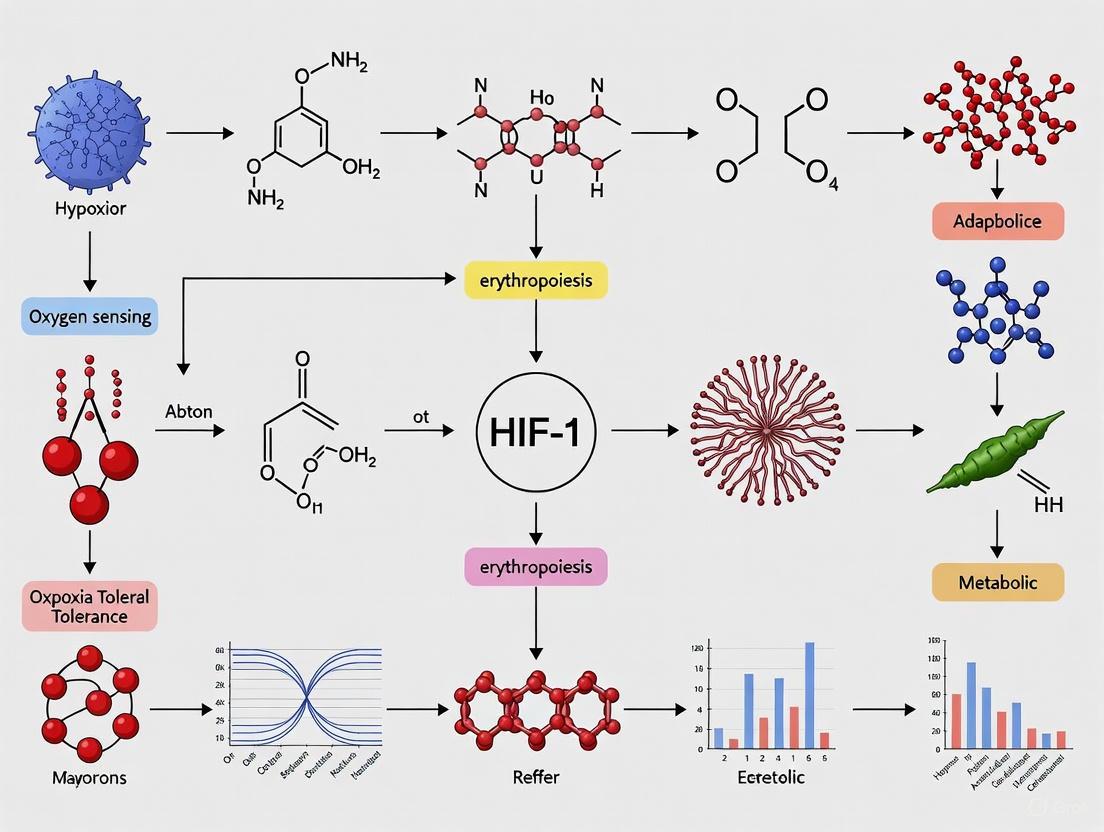

The diagram below illustrates the sequential regulation of HIF-1α by PHDs and FIH along a decreasing oxygen gradient:

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Graded Hypoxia Sensing

In Vitro Hydroxylase Activity Assays

Peptide Binding Assays provide a direct method for investigating PHD-substrate interactions. These assays utilize biotinylated peptides corresponding to specific regions of target proteins (e.g., p23 residues 151-160, FKBP38 residues 47-56, or HSP90 regions) prebound to streptavidin-agarose resins [10]. The resins are then incubated with cell lysates containing the hydroxylase of interest (e.g., EGFP-PHD2 1-63 or mutants thereof) in buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1 μM ZnCl₂ and protease inhibitors [10]. After incubation for 2 hours at 4°C with rocking, resins are washed and eluted proteins are analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using specific antibodies (e.g., anti-GFP for EGFP-tagged PHD2) [10]. This approach enables mapping of specific interaction domains and assessment of how mutations (e.g., zinc finger ablation) affect binding capability.

In Vitro Biotinylation Assays allow direct assessment of hydroxylase activity. Proteins are prepared by TNT T7 Quick coupled transcription/translation reticulocyte lysate reactions, where 0.2 μg of plasmid template is incubated with TNT T7 Quick master mix, 50 μM methionine, 1 μM zinc, and 10 μM biotin in a total volume of 10 μl at 30°C for 60 minutes [10]. BirA or BirA fusion proteins obtained in separate reactions can be included as appropriate. The reaction products are subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and far-Western blotting is performed using streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugates for detection [10]. This method enables direct visualization of hydroxylation-dependent interactions under controlled oxygen conditions.

Auto-hydroxylation Assays are particularly useful for studying FIH activity and regulation. In a typical protocol, apo-FIH (100 μM in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.50) is incubated with FeSO₄ (500 μM) and α-ketoglutarate (500 μM) anaerobically in a sealed cuvette for 1 hour [11]. After measuring the initial absorption spectrum, the cuvette is opened to introduce O₂, and the reaction is monitored by UV-vis spectrophotometer over 10,000 seconds [11]. The formation of a characteristic absorption band at λ~max~ = 583 nm (ε₅₈₃ = 3 × 10³ M⁻¹ cm⁻¹) indicates the generation of an Fe(III)-O-Trp chromophore, confirming auto-hydroxylation at Trp296 [11]. The hydroxylation site can be further identified by LC-MS/MS analysis of tryptic digests, comparing unmodified and +16 Da modified peptide fragments [11].

Table 2: Experimental Results from Hydroxylase Inhibition Studies

| PHD Inhibitor | Effective Concentration for HIF-1α Stabilization | Effect on Autophagy Markers | Protection from OGD Insult |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMOG | 1-2 mM (PC12 cells) | Increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, decreased p62 | Significant reduction in LDH release |

| FG4592 (Roxadustat) | 100 μM (PC12 cells), 30 μM (primary neurons) | Increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, decreased p62, increased Beclin1 | Significant reduction in LDH release |

| Bayer 85-3934 (Molidustat) | 100 μM (PC12 cells) | Increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, decreased p62, increased Beclin1 | Significant reduction in LDH release |

| GSK1278863 (Daprodustat) | 100 μM (PC12 cells) | Increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, decreased p62, increased Beclin1 | Significant reduction in LDH release |

Cellular Models for Hypoxia Response Analysis

Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Models replicate ischemic conditions in vitro. In a representative protocol, PC12 cells or primary rat neurons are subjected to OGD in a hypoxia workstation (0.3% O₂) for 6 hours following 24-hour pretreatment with PHD inhibitors [12]. For the OGD insult, cells are transferred to deoxygenated, glucose-free medium in a hypoxic chamber, while control cells are maintained in oxygenated, glucose-containing medium [12]. Cell viability is assessed post-OGD using MTT assay for mitochondrial activity and LDH release for cytotoxicity. This approach demonstrates that PHD inhibitor pretreatment (100 μM FG4592, FG2216, GSK1278863, or Bay85-3934) 24 hours before OGD significantly reduces LDH release and increases MTT activity compared to vehicle (1% DMSO) pretreatment, indicating a protective effect [12].

HIF-1α Stabilization Assays directly measure the core oxygen sensing mechanism. Cells are treated with PHD inhibitors at varying concentrations (e.g., 1-100 μM for clinical inhibitors, 1 μM-2 mM for DMOG) for 24 hours in normoxia [12]. HIF-1α protein levels are then assessed by Western blotting of nuclear extracts. Typically, the "clinical" PHD inhibitors (FG4592, FG2216, GSK1278863, Bay85-3934) significantly stabilize HIF-1α at 100 μM in PC12 cells, while DMOG requires higher concentrations (1-2 mM) for the same effect [12]. In primary neurons, HIF-1α is stabilized by FG4592 (30 μM) and DMOG (100 μM) [12]. This assay directly demonstrates the differential potency of hydroxylase inhibitors and their cell-type specific effects.

Autophagy Induction Assessment evaluates a key downstream consequence of HIF stabilization. Cells treated with PHD inhibitors are analyzed for autophagy markers by Western blotting [12]. Key markers include LC3b-II/LC3b-I ratio (increased during autophagy), p62/SQSTM1 (decreased during autophagy), and Beclin1 (increased in autophagy induction) [12]. Typically, PHD inhibitors (100 μM) significantly increase the LC3b-II/LC3b-I ratio and downregulate p62 in PC12 cells, similar to the known autophagy inducer rapamycin [12]. FG4592, GSK1278863, and Bay85-3934 (100 μM) also significantly increase Beclin1 levels [12]. These findings demonstrate that HIF stabilization by PHD inhibition induces autophagic flux, which may contribute to the protective effects observed in OGD models.

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for analyzing the HIF hydroxylase pathway:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for HIF Hydroxylase Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHD Inhibitors | DMOG, FG4592 (Roxadustat), GSK1278863 (Daprodustat), Bay85-3934 (Molidustat) | Chemical stabilization of HIF-α for functional studies | Varying potencies; DMOG is non-specific while clinical inhibitors are more potent [12] |

| Cell Lines | HEK293FT, PC12, SKNBE2, Primary rat neurons | In vitro modeling of hypoxia response | Cell-type specific responses observed; primary cells may show different sensitivity [10] [12] [13] |

| Antibodies | Anti-HIF-1α, anti-GFP, anti-H3 (loading control) | Detection and quantification of protein expression/ localization | Critical for Western blotting, immunoprecipitation; nuclear extraction required for HIF-1α detection [10] [13] |

| Molecular Biology Tools | pGIPZ lentiviral shRNAmir vectors, BirA biotinylation system, Strepavidin-agarose | Genetic manipulation and protein interaction studies | Lentiviral shRNA enables efficient HIF1A knockdown; biotinylation systems facilitate interaction studies [10] [13] |

| Hypoxia Chambers/Systems | In Vivo 200 Hypoxia Workstation, nitrogen-controlled chambers | Precise oxygen control for experimental hypoxia | Essential for establishing specific oxygen tensions (0.1-5% O₂) to probe hydroxylase sensitivities [10] [12] |

| Activity Assay Reagents | FeSO₄, 2-oxoglutarate, ascorbate, ZnCl₂, protease inhibitors | In vitro hydroxylase activity measurements | Cofactor supplementation crucial for maintaining enzyme activity in cell-free systems [10] [11] |

The graded hypoxia sensing system, mediated by the sequential activities of PHDs and FIH, represents a sophisticated biological mechanism for fine-tuning cellular responses to oxygen deprivation. The differential oxygen sensitivities of these hydroxylases create a two-tiered regulatory system that allows cells to mount appropriate adaptive responses along a continuum of oxygen availability, from mild to severe hypoxia. This mechanistic understanding has profound implications for both basic physiology and therapeutic development.

From a physiological perspective, this graded sensing system enables precise metabolic adaptation, angiogenic responses, and survival decisions under hypoxic stress. The molecular insights gleaned from studying PHDs and FIH inform our understanding of natural adaptations to hypoxia, such as those occurring in high-altitude populations [10]. From a therapeutic standpoint, the differential regulation of HIF-1α stability and activity offers multiple intervention points for modulating the hypoxic response. Small molecule inhibitors targeting PHDs are already in clinical use for anemia treatment (e.g., roxadustat, daprodustat), while ongoing research explores their potential in ischemic diseases [12]. Future therapeutic strategies may exploit the sequential nature of this regulatory system to achieve more precise modulation of HIF activity for specific clinical applications.

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cellular adaptation to hypoxia, with the Warburg effect representing one of the most fundamental shifts in energy metabolism. This phenomenon, wherein cells preferentially utilize glycolysis for ATP production even in the presence of adequate oxygen, plays a critical role in physiological adaptation to low oxygen tension and in pathological processes such as cancer progression [14] [15]. Under hypoxic conditions, oxygen-sensing machinery triggers extensive molecular rewiring that extends far beyond glycolysis to encompass amino acid metabolism, lipid desaturation, and redox homeostasis. Understanding these mechanisms within the broader context of hypoxia tolerance research provides valuable insights for developing therapeutic strategies against ischemic diseases and cancer. This technical guide examines the molecular architecture of metabolic reprogramming under hypoxia, integrating quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools to serve researchers and drug development professionals investigating these complex adaptive mechanisms.

Molecular Mechanisms of Hypoxia Sensing and Signaling

The HIF Signaling Pathway

The cellular response to hypoxia is primarily mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), heterodimeric transcription factors consisting of an oxygen-regulated α-subunit (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or HIF-3α) and a constitutively expressed β-subunit (HIF-1β) [16] [15]. Under normoxic conditions, prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing enzymes (PHD1-3) hydroxylate specific proline residues on HIF-α using oxygen, α-ketoglutarate, iron (Fe²⁺), and vitamin C as co-substrates [16]. This hydroxylation triggers recognition by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein (pVHL), which recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets HIF-α for proteasomal degradation [16]. Concurrently, factor-inhibiting HIF (FIH) hydroxylates an asparagine residue in the C-terminal transactivation domain of HIF-α, preventing its interaction with transcriptional co-activators p300/CBP and further suppressing HIF signaling [16].

During hypoxia, PHD and FIH activity decreases due to oxygen limitation, leading to HIF-α stabilization, nuclear translocation, dimerization with HIF-1β, and recruitment of co-activators to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) in target genes [16]. HIF-1α and HIF-2α exhibit distinct but overlapping functions: HIF-1α predominantly regulates acute hypoxic response genes including glycolytic enzymes and pH regulators, while HIF-2α more strongly influences erythropoietin (EPO), matrix metalloproteinases, and iron metabolism genes [16]. The HIF switch mechanism transitions signaling from HIF-1 to HIF-2/3 during prolonged hypoxia, which represents a crucial adaptation for chronic oxygen deprivation [16].

Additional Regulatory Mechanisms

Beyond direct oxygen sensing, HIF activity is modulated by multiple secondary mechanisms. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β), NF-κB, and growth factors such as TGF-β can activate HIF-1α through PHD2 inhibition [16]. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway enhances HIF-1α synthesis, while heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) and receptor for activated C-kinase 1 (RACK1) participate in oxygen-independent degradation pathways [16]. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) also promotes HIF-1α degradation, adding another layer of regulation to this complex system [16].

Figure 1: HIF Signaling Pathway in Normoxia and Hypoxia. Under normoxia, active PHD enzymes target HIF-α for degradation. During hypoxia, PHD inhibition enables HIF-α stabilization, dimerization with HIF-1β, and activation of metabolic reprogramming genes.

The Warburg Effect and Metabolic Rearrangements

Fundamentals of the Warburg Effect

The Warburg effect describes the metabolic shift in which cells preferentially utilize glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation for ATP generation, even when oxygen is available [14] [15]. While glycolysis produces only 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule compared to 36 ATP molecules generated through complete oxidative metabolism, its kinetic efficiency and capacity to generate biosynthetic precursors make it advantageous for rapidly proliferating cells [15]. This metabolic reprogramming provides necessary energy and biosynthetic precursors that support cell survival and proliferation under hypoxic stress [17].

Hypoxia drives this metabolic shift primarily through HIF-1-mediated transcriptional upregulation of glucose transporters, glycolytic enzymes, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), while simultaneously suppressing pyruvate entry into mitochondria through induction of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) [17] [18]. The resulting glycolytic flux increases lactate production, which is excreted from cells, acidifying the tumor microenvironment and promoting invasion and metastasis [18].

Metabolic Symbiosis in the Tumor Microenvironment

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment exhibits complex metabolic relationships between different cell populations. The "Reverse Warburg Effect" describes a symbiotic relationship where cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) perform aerobic glycolysis and provide metabolites, including lactate, to cancer cells which then utilize them for oxidative phosphorylation [15]. Similarly, lactate produced by hypoxic cancer cells can be taken up by aerobic cancer cells via monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and utilized for oxidative phosphorylation [15]. This metabolic symbiosis creates heterogeneity within tumors and represents a potential therapeutic target.

Table 1: Key Enzymes and Transporters in Hypoxia-Driven Metabolic Reprogramming

| Component | Function | Regulation by HIF | Impact on Metabolism |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter | Upregulated | Increases glucose uptake |

| HK I/II | Hexokinase (first glycolytic step) | Upregulated | Increases glycolytic flux |

| PFK-1 | Phosphofructokinase-1 (rate-limiting) | Upregulated | Enhances glycolytic rate |

| PKM2 | Pyruvate kinase M2 isoform | Upregulated | Directs carbons to biosynthesis |

| LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A | Upregulated | Converts pyruvate to lactate |

| MCT4 | Monocarboxylate transporter 4 | Upregulated | Exports lactate from cells |

| PDK1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 | Upregulated | Inhibits pyruvate entry to TCA |

| CAIX | Carbonic anhydrase IX | Upregulated | Acidifies microenvironment |

Quantitative Dynamics of Lactate Production

Computational modeling has elucidated the quantitative relationship between oxygen tension, HIF-1 levels, and lactate accumulation. Studies demonstrate that lactate concentration increases progressively with decreasing oxygen levels, with particularly sharp increases below 1.5% oxygen [18]. The temporal dynamics show a delay of approximately 5 minutes before lactate production increases following hypoxic exposure, with accumulation continuing over time [18].

Table 2: Lactate Production Under Varying Oxygen Concentrations

| Oxygen Level (%) | Lactate Concentration (mM) | Time to Detectable Increase | HIF-1α Activity Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 (Normoxia) | 5.50 | N/A | Baseline |

| 6 | 5.66 | >30 minutes | Mildly elevated |

| 3 | 5.78 | 15-30 minutes | Moderately elevated |

| 1.5 | 5.95 | 5-15 minutes | Highly elevated |

| 0.5 | 6.05 | <5 minutes | Maximally elevated |

Sensitivity analysis of glycolytic enzymes reveals that phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), phosphoglucomutase (PGM), phosphoglycerate mutase (PGAM), and glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) exert the strongest influence on lactate production rates, identifying them as key regulatory nodes in the hypoxic glycolytic pathway [18].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Hypoxic Metabolism

Protocol: Computational Modeling of Lactate Dynamics

Purpose: To establish a quantitative relationship between hypoxia intensity and intracellular lactate levels and identify key regulators of the glycolysis pathway [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Hypoxia chamber or hypoxia-inducing chemicals (e.g., CoCl₂)

- Lactate assay kit (colorimetric or fluorometric)

- Glucose measurement reagents

- Cell culture reagents for specific cell lines

- RNA extraction and qRT-PCR reagents for HIF target genes

Procedure:

- Establish Hypoxic Conditions: Culture cells in a hypoxia chamber with precisely controlled oxygen levels (0.5%, 1.5%, 3%, 6%) or treat with chemical hypoxia inducers.

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect cells and media at multiple time points (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes) after hypoxic exposure.

- Metabolite Measurement:

- Lyse cells for intracellular metabolite measurement

- Use lactate assay kit according to manufacturer's protocol

- Measure glucose consumption from culture media

- Gene Expression Analysis:

- Extract total RNA from parallel samples

- Perform qRT-PCR for HIF-1α and glycolytic enzymes (GLUT1, HK2, PFK-1, LDHA)

- Data Integration:

- Input metabolite concentrations and enzyme expression data into mathematical model

- Use ordinary differential equations to represent metabolic fluxes

- Perform sensitivity analysis by varying enzyme activity parameters (KEh)

Validation: Compare model predictions with experimental lactate measurements across different oxygen concentrations and time points. Validate key predictions using enzyme inhibitors or siRNA-mediated knockdown of identified key regulators.

Protocol: Assessing Metabolic Symbiosis

Purpose: To investigate lactate shuttle between hypoxic and aerobic cancer cell populations [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- ¹³C-labeled glucose

- MCT1 and MCT4 inhibitors

- Co-culture system (Transwell or direct co-culture)

- Mass spectrometry for metabolite tracing

- pH sensors for extracellular acidification rate

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Establish hypoxic and aerobic cell populations in co-culture system.

- Isotope Tracing: Feed ¹³C-labeled glucose to hypoxic cells.

- Metabolite Tracking: Track ¹³C-lactate transfer to aerobic cells using mass spectrometry.

- Functional Assays: Measure oxygen consumption rate in aerobic cells with and without hypoxic cell-derived lactate.

- Inhibition Studies: Apply MCT1 and MCT4 inhibitors to disrupt lactate shuttle.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Hypoxic Metabolism. The process begins with establishing controlled hypoxic conditions and progresses through sampling, measurement, and computational analysis to identify key regulatory enzymes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hypoxia Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia Inducers | CoCl₂, DFOM, Hypoxia chambers | Induce HIF stabilization and hypoxic response | Chemical inducers convenient but may have off-target effects |

| HIF Pathway Modulators | PHD inhibitors (FG-4592), HIF-1α inhibitors (PX-478) | Manipulate HIF signaling pathway | Useful for establishing causal relationships |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-DG, Lonidamine, Oxamate | Target specific metabolic enzymes | 2-DG inhibits hexokinase; Oxamine inhibits LDHA |

| Isotope Tracers | ¹³C-glucose, ¹³C-glutamine | Metabolic flux analysis | Enables tracking of nutrient fate |

| MCT Inhibitors | AZD3965 (MCT1), Syrosingopine (MCT4) | Disrupt lactate transport | MCT1 inhibition blocks lactate uptake; MCT4 blocks export |

| Antibodies | Anti-HIF-1α, Anti-CAIX, Anti-GLUT1 | Detect protein expression and localization | HIF-1α requires special handling due to rapid degradation |

| Assay Kits | Lactate assay, Glucose uptake, ATP assay | Quantify metabolic parameters | Colorimetric assays suitable for high-throughput screening |

Therapeutic Targeting of Hypoxic Metabolism

Nanomedicine Approaches

Recent advances in nanomedicine have enabled more precise targeting of hypoxic tumor metabolism. Nanocarriers can be engineered to specifically deliver therapeutic agents to the hypoxic tumor microenvironment, targeting the Warburg effect and associated metabolic pathways [14]. These approaches allow for controlled drug release and improved bioavailability of metabolic inhibitors that traditionally faced challenges in clinical application [14]. Strategies include nanoparticles functionalized with hypoxia-sensitive ligands or designed to release their payload specifically in low oxygen environments.

Targeting Metabolic Enzymes and Transporters

Promising therapeutic targets include carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX), which is strongly induced by hypoxia and contributes to extracellular acidification, facilitating invasion and metastasis [19]. Clinical trials are exploring CAIX inhibitors in combination with conventional therapies. Similarly, monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), particularly MCT1 and MCT4, represent attractive targets for disrupting metabolic symbiosis in tumors [15]. MCT1 inhibitors are currently in clinical development and show promise in selectively targeting tumor cells dependent on lactate uptake.

Biomarker Discovery and Personalized Medicine

Research into individual variations in hypoxia tolerance has identified potential biomarkers, including HIF-1, HSP70, and nitric oxide (NO), which may help stratify patients for targeted metabolic therapies [16]. Understanding these differences can contribute to personalized medicine approaches for diagnostics and treatment of cancers and other hypoxia-related diseases, potentially identifying patients most likely to benefit from therapies targeting hypoxic metabolism [16].

Metabolic reprogramming under hypoxia represents a complex, multifaceted adaptation that extends well beyond the classic Warburg effect to encompass dynamic interactions between signaling pathways, metabolic enzymes, and cellular populations within tissues. The molecular mechanisms centered on HIF signaling integrate with numerous regulatory networks to reshape cellular metabolism in response to oxygen deprivation. Advanced experimental approaches, including computational modeling, metabolic flux analysis, and nanotherapeutic targeting, provide powerful tools for investigating and manipulating these processes. As research continues to unravel the complexities of hypoxic metabolism, new therapeutic opportunities emerge for targeting these pathways in cancer, ischemic diseases, and other conditions characterized by oxygen limitation. The integration of basic mechanistic studies with translational applications promises to advance both our fundamental understanding of cellular adaptation to hypoxia and our ability to therapeutically target these processes in disease states.

Hypoxia, or low oxygen tension, is a pervasive feature of both physiological and pathological contexts, from solid tumors to ischemic diseases. In the tumor microenvironment, hypoxia arises when rapidly proliferating cancer cells outpace the delivery of oxygen by the vasculature, creating regions with oxygen partial pressures (pO2) of ≤10 mm Hg (approximately 1.3% O2), compared to normoxic tissue levels of 23-70 mm Hg [20]. Within this hypoxic niche, cells face a dual challenge: the direct stress of oxygen deprivation and the indirect consequences of metabolic adaptation, which includes increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [21] [22]. This elevated oxidative stress can damage lipids, proteins, and critically, DNA. Paradoxically, while hypoxia itself does not directly cause DNA damage, it significantly inhibits multiple DNA repair pathways, creating a state of heightened genetic instability [20] [23]. This interplay between oxidative stress and compromised DNA repair represents a double-edged sword: it drives disease progression and mutagenesis, yet also reveals unique vulnerabilities that can be targeted therapeutically. This review dissects the molecular mechanisms linking hypoxia, oxidative stress, and DNA damage, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals focused on the physiological molecular mechanisms of hypoxia tolerance.

Molecular Mechanisms: From Oxygen Sensing to DNA Damage

HIF Signaling and Oxidative Stress in Hypoxia

The cellular response to hypoxia is orchestrated primarily by the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) pathway. HIF is a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of an oxygen-sensitive α-subunit (HIF-1α or HIF-2α) and a constitutively expressed β-subunit [21]. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-α is continuously hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs), leading to its recognition by the von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex and subsequent proteasomal degradation [21]. Under hypoxic conditions, PHD activity is inhibited, stabilizing HIF-α. The stabilized subunit translocates to the nucleus, dimerizes with HIF-1β, and activates the transcription of hundreds of genes involved in angiogenesis, glycolysis, and cell survival by binding to Hypoxia Response Elements (HREs; 5'-(A/G)CGTG-3') [24] [21].

A critical and paradoxical aspect of the hypoxic response is the increase in mitochondrial ROS production, primarily at Complex III of the electron transport chain [21] [25]. This ROS surge acts as a signaling molecule that further stabilizes HIF-1α by inhibiting PHD activity, creating a feed-forward loop that amplifies the hypoxic response [21]. However, when sustained, this increase in oxidative stress leads to damage of cellular macromolecules.

Figure 1: Hypoxic Signaling and DNA Damage Cascade. This diagram illustrates the core pathway through which hypoxia leads to genetic instability via HIF stabilization, mitochondrial ROS production, and inhibition of DNA repair pathways.

DNA Damage and Repair Pathway Inhibition

The hypoxic microenvironment contributes to genomic instability not by directly damaging DNA, but primarily by impairing multiple DNA repair pathways, effectively creating a mutator phenotype [20] [26] [23]. The effects are multifaceted and depend on the duration and severity of hypoxia.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Suppression HDR, a high-fidelity pathway for repairing DNA double-strand breaks, is profoundly suppressed under hypoxic conditions through multiple mechanisms:

- Transcriptional Repression: Hypoxia induces nuclear E2F4/p130 complexes that bind to the promoters of key HDR genes like BRCA1 and RAD51, suppressing their expression [20] [23].

- Translational Control: Hypoxia dramatically reduces the translational efficiency of specific HDR genes, including RAD51, BRCA1, and BRCA2, without globally affecting protein synthesis [23].

- miRNA Regulation: Hypoxia-induced miRNAs, such as miR-210, miR-373, and miR-155, directly target the 3'-UTRs of HDR genes like RAD52 and RAD23B, further suppressing their expression [20].

- Epigenetic Silencing: Prolonged hypoxia promotes epigenetic silencing of BRCA1 and RAD51 via histone demethylase LSD1 and Polycomb protein EZH2 [20] [23].

Mismatch Repair (MMR) and Base Excision Repair (BER) The MMR pathway, which corrects DNA replication errors, is also impaired in hypoxia. For instance, the mlh1 gene is repressed in a HDAC-dependent manner [24]. Similarly, BER capacity is reduced, although the mechanisms are less well-characterized [20].

Activation of DNA Damage Signaling Despite the absence of direct DNA damage, hypoxia activates key DNA damage signaling kinases. Severe hypoxia induces replication stress due to nucleotide pool depletion, activating the ATR-CHK1 pathway. This leads to phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX) and other targets, which function to stabilize replication forks rather than repair DNA damage [20] [23]. The ATM kinase is also activated under hypoxia, independently of the MRN complex, and protects cells from apoptosis upon reoxygenation [20].

Quantitative Biomarkers of Hypoxia-Induced Stress and Damage

The cellular response to hypoxic stress can be quantified through specific biomarkers that reflect the degree of oxidative stress, DNA damage, and metabolic adaptation. The following parameters are crucial for experimental assessment and therapeutic targeting.

Table 1: Key Biomarkers in Hypoxic Environments

| Biomarker Category | Specific Marker | Measurement Technique | Biological Significance | Representative Change in Hypoxia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress | Mitochondrial ROS | DCFH-DA fluorescence [22] | Indicator of superoxide & H₂O₂ production | Increase by ~25-40% [22] [25] |

| Lipid Peroxidation | TBARS assay [22] | Membrane damage | Significant increase [22] | |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio | Enzymatic recycling assay [22] | Cellular redox status | Decreased ratio [22] | |

| DNA Damage | Oxidative DNA Lesions | Fpg-/Endo-III-modified Comet Assay [27] | 8-oxoguanine & pyrimidine oxidation | Increase by ~25% [27] |

| DNA Strand Breaks | Alkaline Comet Assay [28] | Direct DNA integrity assessment | Variable (NS in OSAS) [28] | |

| γH2AX Foci | Immunofluorescence [20] [23] | Replication stress & DSB signaling | Pan-nuclear staining & foci formation [23] | |

| Antioxidant Enzymes | MnSOD Activity | spectrophotometric assay [22] | Mitochondrial superoxide scavenging | Phase-dependent change [22] |

| GPx Activity | NADPH consumption assay [22] [27] | H₂O₂ & organic peroxide reduction | Increased protein/content activity [22] | |

| Metabolic Adaptation | Extracellular Lactate | Colorimetric assay [25] | Glycolytic flux | ~2-fold increase [25] |

| Extracellular Acidification | pH meter [25] | Tumor microenvironment acidification | pH decrease from 7.4 to ~6.8 [25] |

Table 2: DNA Repair Pathway Alterations in Hypoxia

| DNA Repair Pathway | Key Regulated Genes/Proteins | Mechanism of Regulation in Hypoxia | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | BRCA1, RAD51, RAD52, FANCD2 | Transcriptional repression (E2F4/p130), translational inhibition, miRNA targeting (miR-210, miR-155), epigenetic silencing (LSD1, EZH2) [20] [23] | Increased mutation frequency, chromosomal instability, gene amplification [20] [26] |

| Mismatch Repair (MMR) | MLH1, MSH2 | HDAC-dependent repression [24] [23] | Microsatellite instability [20] |

| Base Excision Repair (BER) | OGG1, APE1 | Not fully characterized | Accumulation of oxidative base lesions [20] |

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | DNA-PKcs | Activated via phosphorylation (Ser2056) [20] | Altered DSB repair fidelity [20] |

| Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) | DDB2, XPC | Transcriptional downregulation by HIF-1 [23] | Reduced repair of bulky adducts [23] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vitro Models of Hypoxia

Coverslip-Induced Hypoxia Model This method creates oxygen gradients by culturing cells under a coverslip with a central hole that serves as the only oxygen source [25].

- Protocol: Plate cells (e.g., HaCaT keratinocytes) on a chambered coverglass. Cover with a glass coverslip containing a central drilled hole (diameter: 1-2 mm). Culture for 24-48 hours. Cells at the periphery experience severe hypoxia (<0.1% O₂), while cells near the central hole experience moderate hypoxia (1-3% O₂) [25].

- Applications: Simultaneous visualization of intracellular hypoxia (using BioTracker Hypoxia Dye) and oxidative stress (using ROS-sensitive fluorescent probes), measurement of extracellular acidification, and assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential (using TMRM or JC-1 dyes) [25].

- Advantages: Generates physiological oxygen gradients compatible with live-cell imaging; allows correlation of spatial position with hypoxic status.

Controlled Atmosphere Chambers

- Protocol: Use specialized incubators or modular chambers that allow precise control of oxygen levels (typically 0.1-5% O₂), CO₂ (5%), and temperature (37°C) [20].

- Applications: Bulk analysis of molecular responses (Western blot, RNA sequencing), studies of DNA repair capacity, and high-throughput drug screening [20] [23].

- Considerations: Acute hypoxia (<24h) versus chronic hypoxia (>72h) induces distinct biological responses; reoxygenation phases can generate additional ROS bursts [26] [22].

Assessing Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage

Quantifying Intracellular ROS

- DCFH-DA Assay: Cells are loaded with 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (10-20 μM, 20-30 min at 37°C), which is oxidized to fluorescent DCF by ROS. Fluorescence is measured by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy [22].

- MitoSOX Red: Specifically detects mitochondrial superoxide (5 μM, 10 min incubation). The signal is quantified by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy [25].

Measuring DNA Damage

- Comet Assay (Alkaline): Detects single-strand breaks. Cells are embedded in low-melting-point agarose on a microscope slide, lysed (2.5M NaCl, 100mM EDTA, 10mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, pH 10), subjected to electrophoresis under alkaline conditions (pH>13), stained with SYBR Gold, and analyzed for DNA migration ("comet tail") [27] [28].

- Enzyme-Modified Comet Assay: Incorporates bacterial DNA repair enzymes (Formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase, Fpg, or Endonuclease III, Endo-III) to detect specific oxidative base lesions (e.g., 8-oxoguanine) [27].

- Immunofluorescence for γH2AX: Cells are fixed (4% paraformaldehyde), permeabilized (0.5% Triton X-100), stained with anti-γH2AX antibody, and counterstained with DAPI. Foci are quantified by fluorescence microscopy [20] [23].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Hypoxia Studies. This diagram outlines a comprehensive methodology for assessing the molecular impacts of hypoxia, from cell culture under low oxygen to integrated data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hypoxia Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia Mimetics | Dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG), CoCl₂, Deferoxamine (DFO) | Inhibit PHDs to stabilize HIF-α under normoxia [20] | May not fully recapitulate all aspects of true hypoxia; useful for initial screening |

| Hypoxia Detection | Pimonidazole, BioTracker Hypoxia Dye | Forms protein adducts in hypoxic cells (<1.3% O₂) for detection by IF/IHC [25] | Pimonidazole requires antibody detection; BioTracker allows live-cell imaging |

| ROS Detection | DCFH-DA, MitoSOX Red, Dihydroethidium | General ROS or specific superoxide detection by flow cytometry/microscopy [22] [25] | DCFH-DA detects various ROS; MitoSOX is mitochondrial superoxide-specific |

| DNA Damage Assays | Comet Assay kits, Anti-γH2AX antibodies | Quantify strand breaks/oxidative lesions or DSB signaling [27] [28] | Enzyme-modified Comet detects specific base damage; γH2AX indicates replication stress/DSBs |

| Antioxidant Enzymes | Anti-MnSOD, Anti-GPx antibodies | Measure protein levels by Western blot/IF [22] | Activity assays (spectrophotometric) provide functional data |

| HDAC Inhibitors | Vorinostat (SAHA), Trichostatin A | Test epigenetic contributions to DNA repair gene silencing [24] [23] | Can reverse hypoxia-induced repression of some DNA repair genes (e.g., MLH1) |

| HIF Inhibitors | EZN-2968, PX-478 | Direct HIF-1α inhibitors for target validation [21] | Used to dissect HIF-dependent vs. HIF-independent effects |

The interplay between hypoxia, oxidative stress, and DNA damage represents a complex adaptive response with profound implications for cancer biology and therapeutic development. The hypoxic microenvironment triggers a double-edged sword: while the initial increase in ROS functions as a signaling mechanism to activate HIF-mediated adaptation, the subsequent oxidative stress and concurrent suppression of multiple DNA repair pathways foster a state of genetic instability that drives tumor evolution and heterogeneity [21] [20] [23]. From a therapeutic perspective, this creates unique vulnerabilities. Hypoxic tumor cells, already deficient in HDR, become exquisitely sensitive to PARP inhibitors, following the principles of synthetic lethality [23]. Similarly, the dysregulated redox balance in hypoxic cells could be exploited by pro-oxidant therapies or agents that further disrupt already compromised antioxidant systems [21] [22]. Future research should focus on delineating the temporal dynamics of these processes—how acute versus chronic hypoxia differentially influence oxidative stress and DNA repair—and on developing more sophisticated in vitro models that better recapitulate the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment [26] [25]. A deeper understanding of these molecular mechanisms will pave the way for novel targeted interventions that specifically exploit the vulnerabilities of hypoxic cells, potentially overcoming the therapeutic resistance associated with tumor hypoxia.

Hypoxia, or low oxygen availability, represents a fundamental physiological stressor that triggers complex cellular adaptation programs. Beyond the immediate transcriptional responses mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), cells can develop a "molecular memory" of hypoxic exposure through epigenetic modifications. DNA methylation, the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides, has emerged as a crucial mechanism governing this hypoxic stress memory. This whitepaper examines the role of DNA methylation in mediating long-term cellular adaptations to hypoxia, framing this epigenetic regulation within the broader context of physiological molecular mechanisms for hypoxia tolerance.

Molecular Mechanisms of DNA Methylation in Hypoxia Response

Hypoxia-Induced Alterations in DNA Methylation Machinery

Exposure to hypoxic conditions directly regulates the expression and activity of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), the enzymes responsible for establishing and maintaining DNA methylation patterns. Research across multiple model systems demonstrates that hypoxia triggers specific changes in DNMT expression profiles:

Table 1: DNA Methyltransferase Expression in Response to Hypoxia

| DNMT Type | Tissue/Cell Type | Hypoxic Exposure | Expression Change | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Rat hippocampus | Hypobaric hypoxia (25,000 ft, 14 days) | Increased [29] | Associated with neurodegeneration |

| DNMT3a | Rat hippocampus | Hypobaric hypoxia (25,000 ft, 14 days) | No significant change [29] | - |

| DNMT3b | Rat hippocampus | Hypobaric hypoxia (25,000 ft, 14 days) | Increased [29] | Linked to spatial memory impairment |

| DNMT3 | Goldfish brain | Chronic hypoxia (2.1 kPa PO₂, 4 weeks) | No significant change [30] | - |

| DNMT3 | Goldfish heart | Chronic hypoxia (2.1 kPa PO₂, 4 weeks) | Increased [30] | Tissue-specific epigenetic regulation |

Beyond DNMT regulation, hypoxia also affects the ten-eleven translocation (TET) methylcytosine dioxygenases, which catalyze DNA demethylation. In goldfish, a champion of hypoxia tolerance, chronic hypoxia (2.1 kPa PO₂) time-dependently regulated TET expression across tissues. tet2 transcript abundance increased in 4-week hypoxic brain and liver, while tet3 increased in brain, white muscle, and heart after 4 weeks of hypoxia [30]. This suggests that both methylation and demethylation pathways are dynamically regulated under oxygen limitation.

Global and Gene-Specific DNA Methylation Changes

Hypoxia exposure induces both global and gene-specific DNA methylation changes that contribute to long-term cellular adaptation:

Table 2: DNA Methylation Changes in Hypoxic Conditions

| Study Model | Hypoxic Exposure | Global DNA Methylation | Gene-Specific Methylation | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human pulmonary fibroblasts (CCD19Lu) | 1% O₂, 8 days | Significant hypermethylation [31] | Thy-1 promoter hypermethylation [31] | Thy-1 silencing, myofibroblast differentiation |

| Goldfish | 2.1 kPa PO₂, 1 week | Decreased in brain [30] | - | Metabolic suppression |

| Goldfish | 2.1 kPa PO₂, 4 weeks | Increased in brain and heart [30] | - | Tissue-specific adaptation |

| Rat hippocampus | Hypobaric hypoxia (25,000 ft, 14 days) | - | BDNF promoter hypermethylation [29] | BDNF downregulation, memory impairment |

The intersection between mitochondrial metabolism and epigenetics in hypoxic environments reveals sophisticated adaptation mechanisms. Mitochondria, as the "powerhouse of the cell," undergo metabolic changes during hypoxia that influence epigenetic regulation, including DNA methylation patterns that control gene expression networks for angiogenesis, cell survival, and metabolism [32].

DNA Methylation Regulates Transcription Factor Binding in Hypoxia

Methylation-Dependent Control of HIF-DNA Interactions

DNA methylation directly impacts the hypoxia response by regulating the binding of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs) to their target sequences. Research demonstrates that HIFs fail to bind CpG dinucleotides that are methylated in their consensus binding sequence (RCGTG) [33]. This methylation-mediated repression occurs through:

- Steric Hindrance: In silico structural modeling reveals that 5-methylcytosine causes steric hindrance in the HIF binding pocket, physically preventing transcription factor binding [33].

- Cell-Type-Specific Responses: Cell-type-specific DNA methylation landscapes, established under normoxic conditions, determine genome-wide HIF binding profiles and thus cellular responses to hypoxia [33].

- Immunotolerance in Tumors: DNA methylation normally repels HIF binding from repeat regions, but cancer-associated DNA hypomethylation exposes these binding sites, inducing HIF-dependent expression of cryptic transcripts that can compromise tumor immunotolerance [33].

Methylation Sensitivity of HIF Binding

The methylation sensitivity of HIF binding was established through multiple experimental approaches. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) for HIF1β in MCF7 breast cancer cells revealed that HIF binding peaks exhibited invariably low methylation levels (4.95 ± 0.15%) compared to average genomic CpG methylation (61.6 ± 0.07%) [33]. Furthermore, comparative analyses across multiple cell lines (MCF7, RCC4, SK-MEL-28) demonstrated that HIF1β binding peaks unique to individual cell lines were unmethylated specifically in cells where the binding site was active, while shared binding sites were unmethylated across all cell lines [33].

Diagram 1: DNA Methylation-Mediated Gene Regulation in Hypoxia

Functional Consequences in Physiological Systems

Neurological Implications: Neurodegeneration and Memory Impairment

The brain reacts particularly sensitively to oxygen deprivation, with DNA methylation playing a key role in hypoxia-induced neurological impairments. In rat models exposed to hypobaric hypoxia simulating 25,000 feet for 14 days:

- Increased expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3b in the hippocampus correlated with decreased phosphorylation of Methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) and reduced Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) expression [29].

- Cresyl violet and Fluoro-Jade C staining revealed significantly enhanced neurodegeneration in the CA1 region of the hippocampus [29].

- Spatial memory impairment was demonstrated through Morris water maze tests, linking DNMT upregulation and BDNF suppression to cognitive deficits [29].

This pathway represents a clear mechanism by which hypoxic stress creates epigenetic memory through DNA methylation, leading to long-term functional neurological consequences.

Pulmonary Fibrosis and Myofibroblast Differentiation

In human pulmonary fibroblasts, chronic hypoxia (1% O₂ for 8 days) induced significant global hypermethylation accompanied by increased expression of myofibroblast markers [31]. Specific findings included:

- Thy-1 mRNA expression suppression in hypoxic cells, restored with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine [31].

- Methylation-specific PCR confirmed Thy-1 promoter methylation following fibroblast exposure to 1% O₂ [31].

- This epigenetic switching represents a mechanism by which hypoxia promotes the myofibroblast phenotype characteristic of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis pathogenesis [31].

Metabolic Suppression in Hypoxia-Tolerant Species

Goldfish, renowned for their hypoxia tolerance, employ epigenetic mechanisms to achieve metabolic suppression during chronic hypoxia. Unlike mammalian models where hypoxia often induces hypermethylation, goldfish exhibit time-dependent and tissue-specific DNA methylation dynamics:

- Global DNA methylation decreased after 1 week of hypoxia in brain tissue but increased after 4 weeks in both brain and heart [30].

- Components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway (ago2, dgcr8, xpo5) were induced in the chronic hypoxia-acclimated brain, suggesting combined transcriptional and post-transcriptional repression supports metabolic suppression [30].

- These epigenetic modifications contribute to the hypometabolic state that allows goldfish to survive chronic hypoxia with up to 74% metabolic rate suppression [30].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo Hypoxia Exposure Models

Hypobaric Hypoxia Rat Model

- Animals: Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (220 ± 10 g) [29]

- Exposure Protocol: Continuous HH at simulated altitude of 25,000 feet (~7,600 m) for 14 days in animal decompression chamber, with 10-15 min daily intervals for animal care [29]

- Environmental Control: Chamber temperature maintained at 25 ± 2°C, humidity 55 ± 5% [29]

- Behavioral Assessment: Spatial memory evaluated using Morris water maze before and after HH exposure for memory retention [29]

Goldfish Chronic Hypoxia Model

- Acclimation: Gradual reduction to severe hypoxia (2.1 kPa PO₂) over one week, maintained for 1-4 weeks [30]

- Tissue Analysis: Brain, liver, white muscle, and heart collected at normoxia, 1 week hypoxia, and 4 weeks hypoxia [30]

In Vitro Cell Culture Models

Human Pulmonary Fibroblast Model

- Cell Line: CCD19Lu normal human pulmonary fibroblasts [31]

- Hypoxic Conditions: 1% O₂ in hypoxic chamber (Coy Laboratories) for up to 8 days [31]

- Demethylation Treatment: 1 μM 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine replenished every second day for 8 days [31]

Cancer Cell Line Models

- Cell Lines: MCF7 (breast cancer), RCC4 (renal cell carcinoma), SK-MEL-28 (melanoma) [33]

- Hypoxic Exposure: 0.5% O₂ for 16 hours (acute hypoxia) to stabilize HIFs without inducing hypoxia-mediated hypermethylation [33]

Molecular Biology Techniques

DNA Methylation Analysis

- Global Methylation: Flow cytometry with monoclonal anti-5-methylcytosine antibody after HCl denaturation [31]

- Promoter-Specific Methylation: Methylation-specific PCR (MSPCR) with bisulfite-converted genomic DNA [31]

- Genome-Wide Methylation: Target enrichment-based bisulfite sequencing (>40× coverage) or whole-genome bisulfite sequencing [33]

- 5mC vs 5hmC Discrimination: 5-methylcytosine DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (5mC-DIP-seq) [33]

Gene Expression Analysis

- RNA Quantification: NanoDrop spectrophotometry and agarose gel integrity verification [29]

- cDNA Synthesis: Verso cDNA synthesis kit with housekeeping gene (GAPDH) compatibility assessment [29]

- Real-time PCR: SYBR Green master mix with ΔΔCT method for relative quantification [29]

- Primer Design: Exon-exon boundary spanning primers to ensure mature mRNA amplification [31]

Protein Analysis

- Immunoblotting: Protein extraction from snap-frozen hippocampus with RIPA buffer [29]

- Antibody Targets: DNMT1, DNMT3a, DNMT3b, MeCP2, pMeCP2, BDNF [29]

Chromatin Studies

- HIF Binding Mapping: Chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) for HIF1β [33]

- Peak Calling: Model-based analysis for ChIP-seq (MACS) with HRE motif enrichment validation [33]

Diagram 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying DNA Methylation in Hypoxia

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hypoxia DNA Methylation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT Inhibitors | 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine | Demethylating agent | Restores gene expression silenced by hypoxia-induced hypermethylation [31] |

| Hypoxia Chamber Systems | Coy Laboratories chambers | Maintain precise low O₂ environments | In vitro chronic hypoxia exposure (1% O₂) [31] |

| Animal Decompression Chambers | Custom hypobaric chambers | Simulate high-altitude conditions | In vivo hypobaric hypoxia exposure [29] |

| Methylation Detection Antibodies | Monoclonal anti-5-methylcytosine | Global methylation quantification | Flow cytometry analysis of global 5mC levels [31] |

| DNA Methylation Analysis Kits | Bisulfite conversion kits | Convert unmethylated cytosine to uracil | MSPCR, bisulfite sequencing [33] [31] |

| ChIP-seq Kits | HIF1β ChIP-seq reagents | Genome-wide HIF binding mapping | Identify methylation-sensitive HIF binding sites [33] |

| Gene Expression Master Mixes | SYBR Green master mix | Real-time PCR quantification | DNMT, TET, BDNF expression analysis [29] |

| Primary Antibodies for Western Blot | DNMT1, DNMT3a, DNMT3b, MeCP2, pMeCP2, BDNF | Protein expression quantification | Immunoblotting of methylation machinery and targets [29] |

DNA methylation serves as a critical mechanism for hypoxic stress memory across physiological systems, from pathological conditions in mammals to adaptive responses in hypoxia-tolerant species. The evidence demonstrates that hypoxia induces both global and gene-specific DNA methylation changes through regulation of DNMTs and TET enzymes, with functional consequences including neurodegeneration, fibroblast differentiation, and metabolic suppression. The methylation-dependent blockade of HIF binding to target genes reveals a sophisticated regulatory layer controlling cellular hypoxia responses. These findings highlight the potential of DNMT inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for hypoxia-related pathologies and establish DNA methylation as a fundamental component of the physiological molecular mechanisms underlying hypoxia tolerance.

Assessing Tolerance and Harnessing Adaptive Mechanisms for Therapy

Hypoxia, or oxygen deficiency, represents a significant challenge across various fields, from clinical medicine to aquaculture and environmental biology. Understanding an organism's capacity to withstand low oxygen conditions is crucial for predicting survival, assessing ecological impacts, and developing therapeutic interventions. The predisposition to hypoxia-related disorders is largely governed by an individual's basic tolerance to oxygen deficiency [16]. This in-depth technical guide examines the current landscape of hypoxia tolerance metrics, spanning from whole-organism physiological measurements to cutting-edge molecular biomarkers, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive toolkit for assessing hypoxic responses across experimental contexts.

Physiological Metrics of Hypoxia Tolerance

Critical Oxygen Tension (Pcrit)

Definition and Physiological Significance: The critical oxygen tension (Pcrit) is arguably the most prevalent metric for quantifying hypoxia tolerance in aquatic organisms, particularly fishes [34]. It is defined as the oxygen level below which an animal can no longer maintain a stable rate of oxygen uptake (ṀO₂), transitioning from an oxygen regulator to an oxygen conformer [35] [34]. Below this threshold, the organism's oxygen uptake becomes dependent upon ambient oxygen availability, and it must increasingly rely on anaerobic metabolism, reduce its metabolic rate, or both to survive [35].

Methodological Considerations: Pcrit is typically determined by placing a post-absorptive animal in a respirometer and gradually decreasing oxygen levels while continuously measuring oxygen uptake rates [34]. The resulting data plot of ṀO₂ against ambient PO₂ allows researchers to identify the inflection point where regulation fails. It is important to note that Pcrit can be determined for different metabolic rates, including standard metabolic rate (SMR), routine metabolic rate (RMR), and maximum metabolic rate (MMR), each providing different physiological information [34]. A significant methodological concern is the inconsistent increase in partial pressure of CO₂ within a closed respirometer during Pcrit measurements, which can vary from 650 to 3500 µatm and potentially affect blood acid-base balance and Pcrit values themselves [34].

Limitations and Controversies: Despite its widespread use, Pcrit faces substantial criticism. A comprehensive review highlights six key limitations: (1) calculation often involves selective data editing; (2) values depend greatly on determination method; (3) lack of strong theoretical justification; (4) it does not represent the transition point from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism; (5) unreliable as an index of hypoxia tolerance; and (6) carries minimal information content [36]. This has led to calls for more informative alternatives, such as the regulation index and Michaelis-Menten or sigmoidal allosteric analyses [36].

Table 1: Factors Influencing Pcrit Measurements in Fishes

| Factor | Effect on Pcrit | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Positive correlation | Higher temperatures increase metabolic rate and Pcrit | [34] |

| Body Mass | Positive correlation | Larger individuals generally have higher Pcrit | [34] |

| Salinity | Variable | Effect depends on species and osmoregulatory strategy | [34] |

| Metabolic Rate | Positive correlation | Higher routine metabolic rate correlates with higher Pcrit | [34] |

| CO₂ Accumulation | Increases Pcrit | Often overlooked methodological artifact | [34] |

Loss of Equilibrium (LOE) and Related Metrics

Definition and Practical Application: Loss of equilibrium (LOE) represents a more severe metric of hypoxia tolerance, defined as the oxygen level or time at which fish lose their capacity for coordinated movement and the ability to right themselves [35]. As this failure would almost certainly result in mortality in natural settings, it has also been termed the incipient lethal oxygen level (ILOL) or incipient lethal oxygen saturation (ILOS) [35]. LOE has largely replaced mortality as an experimental endpoint due to animal welfare concerns, with the added benefit that fish typically recover completely if promptly returned to well-oxygenated water [35].

Validation and Ecological Relevance: The ecological relevance of LOE is supported by research demonstrating that fish with longer times to LOE during laboratory exposures showed greater survival than fish with shorter times when subsequently maintained in semi-natural outdoor enclosures [35]. This correlation between LOE time and fitness argues for its biological significance beyond a mere laboratory measurement.