Distinct Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia: Biomarker Discovery, Pathophysiological Insights, and Clinical Implications

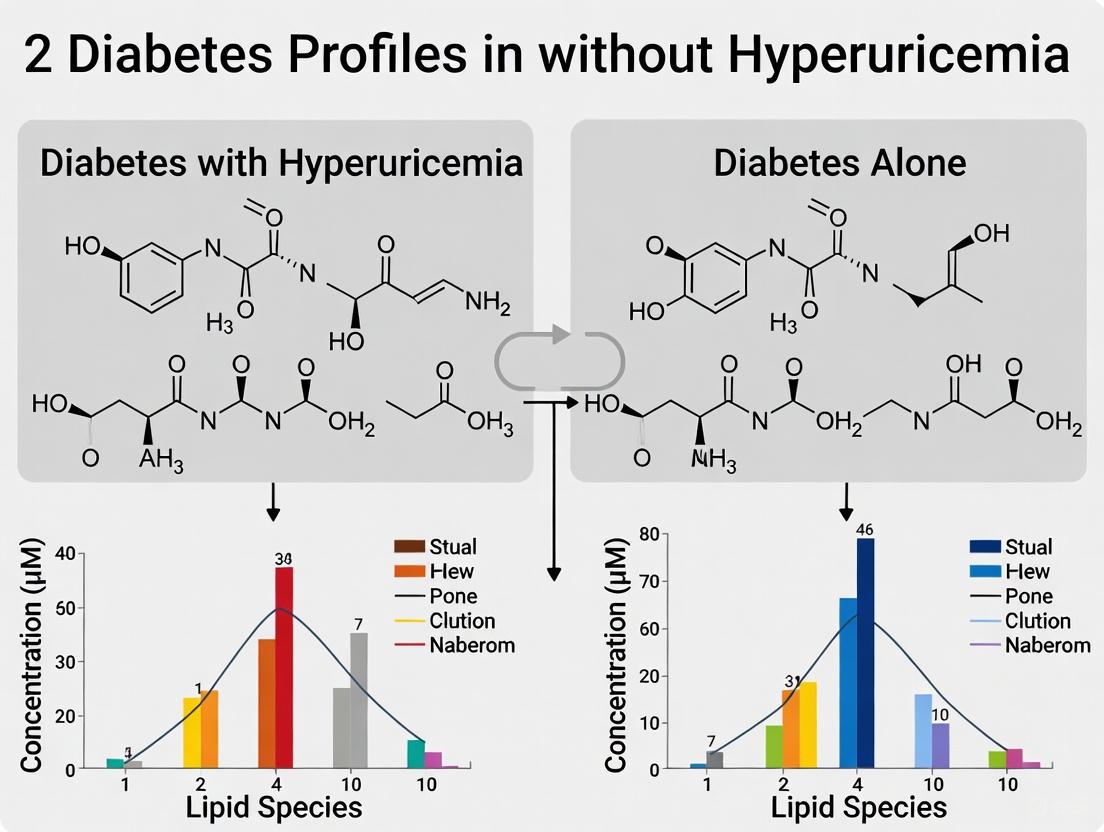

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct plasma lipidomic profiles that differentiate patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) from those with diabetes and comorbid hyperuricemia (DH).

Distinct Lipidomic Signatures in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia: Biomarker Discovery, Pathophysiological Insights, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct plasma lipidomic profiles that differentiate patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) from those with diabetes and comorbid hyperuricemia (DH). Utilizing advanced mass spectrometry-based lipidomics, recent studies reveal significant upregulation of specific triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and phosphatidylcholines (PCs) in DH, with marked perturbations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways. We explore the methodological frameworks for lipidomic analysis, address key challenges in biomarker validation and reproducibility, and evaluate the comparative performance of lipid signatures against conventional clinical biomarkers. This synthesis is intended to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals about the potential of lipidomics for revealing novel pathophysiological mechanisms, identifying diagnostic biomarkers, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies for this high-risk patient population.

Unraveling the Lipidomic Landscape: Key Alterations in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

Clinical and Epidemiological Significance

The co-occurrence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA) represents a significant clinical challenge in metabolic medicine. Epidemiological studies reveal a substantial overlap between these conditions, with HUA prevalence among diabetic patients reported at 21.24% in China and 20.70% in North America [1]. This coexistence is clinically consequential, as patients with both conditions face significantly worse outcomes than those with either condition alone.

A substantial 7-year cohort study of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3-5 demonstrated that the combination of DM and HUA synergistically increases risk. Compared to patients with neither condition, those with both DM and HUA had dramatically elevated hazards for all-cause mortality (HR = 2.12) and end-stage kidney disease (HR = 2.46) [2]. This risk profile was substantially worse than for either condition alone, underscoring the clinical importance of their co-occurrence.

Table 1: Comparative Risk for Adverse Outcomes in CKD Patients (Stages 3-5) [2]

| Condition | All-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratio (HR) | End-Stage Kidney Disease Hazard Ratio (HR) |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperuricemia alone | 1.48 | 1.34 |

| Diabetes alone | 1.52 | 1.59 |

| Diabetes + Hyperuricemia | 2.12 | 2.46 |

Recent scientometric analysis reveals consistently growing research interest in the HUA-diabetes relationship, with publication output peaking at 170 publications in 2021 alone [1]. This reflects increasing recognition of their pathophysiological interplay and clinical implications.

Lipidomic Profiles: Diabetes with Hyperuricemia vs. Diabetes Alone

Advanced lipidomic technologies have revealed distinct plasma lipid profiles that differentiate patients with coexisting diabetes and hyperuricemia (DH) from those with diabetes alone (DM). Using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS), researchers have identified characteristic lipid alterations that provide mechanistic insights into this metabolic synergy [3].

Key Lipidomic Alterations

A comprehensive untargeted lipidomic analysis identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with multivariate analyses revealing significant separation between DH, DM, and normoglycemic control (NGT) groups [3]. The most prominent differences between DH and DM groups include significant upregulation of specific lipid species:

Table 2: Significantly Altered Lipid Metabolites in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia (DH) vs. Diabetes Alone (DM) and Healthy Controls [3]

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Molecules Altered | DH vs. NGT | DH vs. DM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 others | Significantly upregulated | 13 TGs upregulated |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and others | Significantly upregulated | 10 PEs upregulated |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and others | Significantly upregulated | 7 PCs upregulated |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | - | One PI downregulated | Not specified |

| Total Significant Lipids | - | 31 | 12 |

These lipid alterations are not merely correlative but reflect fundamental disturbances in metabolic pathways. The collective analysis revealed enrichment of these differential lipids in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed in DH patients [3].

Other studies in middle-aged and elderly Chinese populations have corroborated these findings, identifying 123 lipids significantly associated with uric acid levels, predominantly glycerolipids (GLs) and glycerophospholipids (GPs). Specific lipid signatures strongly associated with HUA risk included diacylglycerols [DAG(16:0/22:5), DAG(16:0/22:6), DAG(18:1/20:5), DAG(18:1/22:6)], phosphatidylcholine [PC(16:0/20:5)], and triacylglycerol [TAG(53:0)], while lysophosphatidylcholine [LPC(20:2)] was inversely associated with HUA risk [4].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Human Study Protocols

Human lipidomic studies follow rigorous standardized protocols. In one representative study, researchers recruited 17 patients each for DH, DM, and healthy control groups, matched 1:1 by sex and age [3]. After overnight fasting, blood samples were collected and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature. The upper plasma layer (0.2 mL) was aliquoted and stored at -80°C until analysis.

The lipid extraction protocol involved:

- Thawing samples on ice and vortexing

- Adding 100 μL plasma to 200 μL of 4°C water

- Mixing with 240 μL pre-cooled methanol

- Adding 800 μL methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)

- Sonicating in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes

- Standing at room temperature for 30 minutes

- Centrifuging at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C

- Collecting and drying the upper organic phase under nitrogen [3]

Animal Model Development

To investigate the mechanistic interplay between these conditions, researchers have developed a novel diabetic hamster model with combined hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia. The model induction protocol involves:

Diabetes Induction: Intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ, 30 mg/kg) once daily for 3 consecutive days to induce pancreatic β-cell damage [5]

Hyperuricemia Induction: Intragastric administration of potassium oxonate (PO, 350 mg/kg) and adenine (150 mg/kg) with 5% fructose water to inhibit uricase activity [5]

Dyslipidemia Induction: Feeding with high-fat/cholesterol diet (HFCD) containing 15% fat and 0.5% cholesterol [5]

This combined intervention successfully established a model exhibiting characteristic features of the human condition: serum uric acid (499.5 ± 61.96 μmol/L), glucose (16.88 ± 2.81 mmol/L), triglyceride (119.88 ± 27.14 mmol/L), and total cholesterol (72.92 ± 16.62 mmol/L) [5].

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The relationship between diabetes and hyperuricemia involves complex, bidirectional pathophysiological mechanisms. Uric acid contributes to insulin resistance through multiple pathways, including increased oxidative stress, stimulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and chronic inflammatory responses [6].

Key Mechanistic Insights

Research indicates that uric acid impairs pancreatic β-cell survival and function, though alone it may be insufficient to induce diabetes [1]. In the context of pre-existing metabolic dysfunction, however, elevated uric acid accelerates disease progression through several mechanisms:

Oxidative Stress: Uric acid transitions from antioxidant to pro-oxidant at elevated concentrations, generating reactive oxygen species that impair insulin signaling [6]

Inflammatory Activation: Uric acid crystals and soluble urate activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, promoting interleukin-1β production and chronic inflammation [6]

Lipid Metabolism Disruption: Uric acid induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and activates sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), promoting hepatic fat accumulation [7]

Endothelial Dysfunction: Elevated uric acid impairs nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation and promotes endothelial inflammation [6]

The identified lipidomic alterations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways reflect these underlying mechanistic disturbances, potentially serving as both biomarkers and mediators of the enhanced metabolic risk in DH patients [3].

Diagram: Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Hyperuricemia to Diabetes Progression and Lipidomic Alterations. The diagram illustrates how elevated uric acid (UA) triggers multiple pathological processes that converge to promote insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, and the distinct lipidomic profile characteristic of diabetes with hyperuricemia (DH).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Diabetes-Hyperuricemia Lipidomic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application Purpose | Technical Specifications | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-MS/MS System | Lipid separation and quantification | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm); SCIEX 5500 QTRAP mass spectrometer [3] | High-resolution lipid separation and sensitive detection |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Lipid extraction | LC-MS grade [3] [7] | Organic solvent for efficient lipid extraction from plasma |

| Potassium Oxonate (PO) | Hyperuricemia induction in models | >98% purity; 350 mg/kg dosage in hamsters [5] | Uricase inhibitor to elevate serum uric acid |

| Streptozotocin (STZ) | Diabetes induction in models | >98% purity; 30 mg/kg dosage in hamsters [5] | Pancreatic β-cell cytotoxin for diabetes modeling |

| SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Standard | Lipid quantification reference | Commercially available mass spec standard mixture [7] | Internal standard for lipid semi-quantification |

| Ammonium Formate | Mobile phase additive | 10 mM in acetonitrile/water and acetonitrile/isopropanol [3] | Enhances ionization efficiency in mass spectrometry |

This toolkit enables comprehensive investigation of the diabetes-hyperuricemia relationship, from model creation to molecular analysis. The standardized protocols ensure reproducibility across studies, while the analytical methods provide deep metabolic profiling capabilities essential for understanding the complex interplay between these conditions.

The clinical co-occurrence of diabetes and hyperuricemia represents a distinct metabolic phenotype with characteristic lipidomic signatures, enhanced clinical risks, and unique pathophysiological mechanisms. The distinct lipidomic profile marked by alterations in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways provides both biomarkers for risk stratification and insights into potential therapeutic targets.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Longitudinal Studies: Tracking lipidomic evolution from isolated diabetes to diabetes with hyperuricemia

- Therapeutic Intervention: Investigating how urate-lowering therapies affect the diabetic lipidome and clinical outcomes

- Mechanistic Studies: Elucidating how specific lipid species contribute to insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction

- Diagnostic Applications: Developing clinical algorithms incorporating lipidomic signatures for personalized risk assessment

The robust experimental models and analytical methodologies now available provide powerful tools to address these questions, potentially leading to improved clinical management strategies for this high-risk patient population.

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid pathways and networks, has revolutionized our understanding of metabolic diseases by revealing the profound diversity and complexity of the lipidome [8]. Lipids are no longer viewed merely as energy storage molecules but as dynamic mediators of cellular signaling, membrane structure, and metabolic regulation. The human lipidome encompasses tremendous structural diversity, with over 40,000 lipid structures cataloged in the LIPID MAPS database as of 2018, organized into eight major categories: fatty acyls, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides [8].

Advances in mass spectrometry technologies have enabled comprehensive lipid profiling, revealing that alterations in specific lipid classes and subclasses are intimately associated with metabolic disease progression [9] [8]. This review examines the current landscape of lipidomics research, with particular focus on the distinct lipidomic signatures that differentiate complex metabolic conditions such as diabetes with concurrent hyperuricemia from diabetes alone. Through comparative analysis of experimental data and methodologies, we provide a resource for researchers and drug development professionals working to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Lipidomics Technologies and Methodologies

Analytical Platforms for Lipid Separation and Detection

Mass spectrometry has emerged as the cornerstone technology for lipidomic analysis due to its high sensitivity and capacity for high-throughput applications [8]. The two primary approaches are liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and shotgun lipidomics, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Chromatography-based lipidomics utilizing ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry provides superior separation of structurally similar lipid species. The method described by [10] uses a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) with a mobile phase consisting of 10 mM ammonium formate in water (A) and 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-isopropanol (B). This approach offers excellent analytical specificity for individual lipid species within a given class but requires longer analysis times and introduces potential variability through multiple processing steps [8].

Shotgun lipidomics directly introduces lipid extracts into the mass spectrometer without chromatographic separation, relying instead on differential ionization and mass-to-charge ratio resolution. The Lipidyzer platform described in [9] utilizes a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex QTRAP 5500) with differential mobility separation (DMS), enabling identification and quantification of >1,000 lipid species across 16 subclasses. This approach offers high-throughput capabilities from limited biological samples but has reduced capacity to distinguish isobaric lipid species compared to LC-MS methods [8].

Lipid Extraction and Quantification Methods

Effective lipid extraction is critical for comprehensive lipidome coverage. The Folch method (chloroform:methanol, 2:1) and Bligh and Dyer method (chloroform:methanol, 1:2) represent traditional biphasic extraction approaches that partition lipids into an organic phase while removing proteins and nucleic acids [8]. Recent advances favor monophasic extraction methods using solvents such as isopropanol, which improve recovery of polar lipid species that may partially partition into the aqueous phase in biphasic systems [10] [11].

For accurate quantification, lipidomic workflows incorporate deuterated internal standards. The longitudinal study by [9] included 54 deuterated spike-in standards across nine lipid subclasses at known concentrations. Lipid species without corresponding labeled standards were normalized against structurally similar standards with correlated signal patterns. This approach enables precise quantification across wide concentration ranges spanning up to four orders of magnitude [9].

Table 1: Key Methodological Approaches in Lipidomics Studies

| Study | Extraction Method | Separation Platform | Detection Method | Internal Standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Not specified | Differential Mobility Separation | QTRAP 5500 MS | 54 deuterated standards across 9 subclasses |

| [10] | Monophasic (MTBE/methanol) | UHPLC BEH C18 column | Tandem MS | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX, deuterated Cer & FA |

| [11] | Monophasic (isopropanol) | Reversed-phase C8 column | QTRAP 6500+ MS | Deuterated standards specified in supplementary |

| [12] | Not specified | LC-MS platform | Untargeted MS | Not specified |

Figure 1: Generalized Lipidomics Workflow. The typical pipeline involves sample collection, lipid extraction with internal standards, separation by chromatography or direct infusion, mass spectrometry detection, and computational analysis.

Lipidomic Signatures in Metabolic Diseases

Diabetes Mellitus with Hyperuricemia vs. Diabetes Alone

Comprehensive lipidomic profiling reveals distinct patterns that differentiate diabetes mellitus with hyperuricemia (DH) from diabetes alone (DM). A study comparing these conditions identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, with multivariate analyses showing clear separation between DH, DM, and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) groups [10].

The DH group exhibited 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites compared to NGT controls, characterized by:

- 13 triglycerides significantly upregulated, including TG(16:0/18:1/18:2)

- 10 phosphatidylethanolamines significantly upregulated, including PE(18:0/20:4)

- 7 phosphatidylcholines significantly upregulated, including PC(36:1)

- 1 phosphatidylinositol significantly downregulated

Pathway analysis revealed these differential lipids were enriched in glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) [10]. When comparing DH versus DM groups directly, researchers identified 12 differential lipids that were similarly enriched in these core pathways, underscoring their central role in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [10].

Hyperuricemia and Gout-Associated Lipid Alterations

Lipidomic studies of hyperuricemia and gout reveal consistent alterations in glycerophospholipid metabolism. A comprehensive targeted lipidomic analysis of 608 plasma lipids in 94 hyperuricemia and 196 gout patients found the most significant changes included upregulation of phosphatidylethanolamines and downregulation of lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogens/plasmanyls [11].

Notably, more profound lipid disturbances were observed in early-onset patients (age ≤ 40 years), with multivariate statistics differentiating early-onset hyperuricemia and gout groups from healthy controls with >95% accuracy [11]. Urate-lowering treatment (ULT) appeared to partially correct this lipid imbalance, suggesting a modifiable component to these lipid alterations.

Obesity and Insulin Resistance-Associated Lipid Changes

Longitudinal deep lipidome profiling of >1,500 plasma samples from 112 participants followed for up to 9 years has revealed dynamic lipidome alterations associated with insulin resistance and ageing [9]. Individuals with insulin resistance exhibited disturbed immune homeostasis and accelerated changes in specific lipid subclasses during ageing, including:

- Altered associations between lipids and clinical markers

- Distinct trajectories for large and small triacylglycerols

- Differential changes in ester- and ether-linked phosphatidylethanolamines

Pediatric studies have identified increased ceramides alongside decreased lysophospholipids and omega-3 fatty acids in children with obesity [12]. Specific lipid classes showed strong associations with cardiometabolic risk, with ceramides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylinositols associated with insulin resistance, while sphingomyelins showed inverse associations [12].

Table 2: Key Lipid Classes Altered in Metabolic Diseases

| Lipid Class | Subclasses | Diabetes with Hyperuricemia | Gout/Hyperuricemia | Obesity/Insulin Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerophospholipids | Phosphatidylcholines (PC) | Upregulated [10] | Not specified | Divergent trends [12] |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) | Upregulated [10] | Upregulated [11] | Associated with insulin resistance [12] | |

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) | Not specified | Downregulated [11] | Decreased [12] | |

| Glycerolipids | Triglycerides (TG) | Upregulated [10] | Not specified | Increased [12] |

| Diacylglycerols (DG) | Not specified | Not specified | Increased [12] | |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramides (Cer) | Not specified | Not specified | Increased [12] |

| Sphingomyelins (SM) | Not specified | Not specified | Decreased [12] |

Pathophysiological Implications and Mechanisms

Lipid Metabolism Pathways in Metabolic Disease

The consistent identification of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism as disturbed pathways across multiple metabolic conditions points to their central role in disease pathophysiology. Glycerophospholipids are essential components of cellular membranes and play crucial roles in signal transduction, while glycerolipids, particularly triglycerides, represent key energy storage molecules.

The upregulation of specific phosphatidylethanolamines and triglycerides in diabetes with hyperuricemia suggests increased membrane remodeling activity and altered energy storage patterns [10]. The reduction in lysophosphatidylcholines, observed in both hyperuricemia and obesity, may reflect increased inflammation or altered phospholipase activity [11] [12].

Ceramide-Mediated Insulin Resistance

The association between ceramides and insulin resistance represents a key mechanism linking lipid dysregulation to metabolic dysfunction. Ceramides, a class of sphingolipids, have been shown to impair insulin signaling through multiple mechanisms, including inhibition of AKT/PKB activation and promotion of inflammatory pathways [12]. In pediatric obesity, ceramides partially mediate the association between obesity and cardiometabolic traits, suggesting these pathways are activated early in disease progression [12].

Figure 2: Ceramide-Mediated Pathway to Metabolic Dysfunction. Obesity-driven lipid accumulation promotes ceramide synthesis, which impairs insulin signaling and promotes inflammation, leading to systemic metabolic dysfunction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard; Deuterated ceramide (d18:1-d7/15:0); Oleic acid-d9 [11] | Quantification accuracy through isotope dilution |

| Chromatography Columns | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) [10]; Reversed-phase BEH C8 column [11] | Lipid separation by hydrophobicity |

| Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) [10]; Isopropanol [11]; Chloroform-methanol mixtures [8] | Lipid isolation from biological matrices |

| MS Instrumentation | QTRAP 6500+ [11]; Triple-quadrupole MS with DMS [9]; UHPLC-MS/MS systems [10] | Lipid detection and quantification |

Comprehensive lipidomic profiling has revealed the remarkable diversity of the lipidome and its intricate connections to metabolic disease pathophysiology. The distinct lipid signatures differentiating diabetes with hyperuricemia from diabetes alone highlight the nuanced lipid disturbances underlying complex metabolic conditions. The consistent involvement of glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways across multiple studies suggests these represent core perturbed processes in metabolic disease.

Advanced mass spectrometry platforms, coupled with robust extraction and quantification methods, now enable researchers to characterize hundreds to thousands of lipid species simultaneously, providing unprecedented insights into lipid metabolism. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, lipidomics promises to deliver novel biomarkers for early detection, stratification, and monitoring of metabolic diseases, ultimately guiding the development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

Lipidomic profiling reveals distinct plasma lipid signatures that differentiate patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH) from those with diabetes mellitus alone (DM). Through untargeted lipidomics based on ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS), researchers have identified a specific panel of upregulated lipid molecules—notably triglycerides (TGs), phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and phosphatidylcholines (PCs)—in DH patients. These differentially expressed lipids are predominantly enriched in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways, providing a molecular basis for the exacerbated metabolic dysregulation observed when hyperuricemia complicates diabetes. This comparative analysis synthesizes key experimental data and methodologies to guide future research and therapeutic development in metabolic disease.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia are common metabolic disorders that frequently co-exist, creating a combined condition (DH) associated with worsened clinical outcomes. Lipidomics, a branch of metabolomics, has emerged as a powerful tool for characterizing specific lipid disturbances in metabolic diseases beyond conventional clinical biomarkers [3]. While previous studies have separately documented lipid alterations in diabetes [9] and hyperuricemia [3], only recent investigations have directly compared the lipidomic profiles of DH versus DM alone. These studies reveal that the hyperuricemic state in diabetic patients induces specific lipidomic changes characterized by upregulated TGs, PEs, and PCs, highlighting the complex interplay between purine and lipid metabolism in disease progression. Understanding these distinct lipid signatures provides valuable insights for developing targeted interventions for this high-risk patient population.

Comparative Lipidomic Profiles: DH vs. DM

Signature Lipid Molecules

A comprehensive UHPLC-MS/MS-based lipidomic analysis of plasma samples from DH and DM patients identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses [3]. Multivariate analyses revealed significant separation trends among DH, DM, and healthy control (NGT) groups, confirming distinct lipidomic profiles.

Table 1: Signature Upregulated Lipid Molecules in DH vs. DM and NGT

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Molecules | Regulation in DH vs. NGT | Regulation in DH vs. DM | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significantly upregulated | Upregulated | Energy storage, lipid accumulation, insulin resistance |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significantly upregulated | Upregulated | Membrane structure, cellular signaling |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significantly upregulated | Upregulated | Membrane integrity, lipid transport |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | One unspecified PI | Downregulated | Not specified | Cell signaling processes |

When comparing DH versus DM groups specifically, researchers identified 12 significantly differential lipids that were also predominantly enriched in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways [3]. The collective analysis of these metabolite groups revealed their enrichment in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [3].

Pathway Analysis

The differential lipid signature in DH patients reflects profound disruptions in key metabolic pathways:

Glycerophospholipid Metabolism: This pathway showed the highest impact value (0.199) in DH patients, indicating substantial alterations in membrane lipid composition and signaling precursors [3]. The upregulation of multiple PC and PE species suggests increased membrane remodeling activity and potential impacts on membrane fluidity and signaling in the combined disease state.

Glycerolipid Metabolism: With an impact value of 0.014, this pathway demonstrated significant perturbation, primarily driven by the elevated TG species [3]. This finding reflects enhanced lipogenesis and impaired lipid clearance mechanisms in DH patients, potentially contributing to increased cardiovascular risk.

The consistency of pathway perturbations across both DH vs. NGT and DH vs. DM comparisons underscores the central role of these metabolic disruptions in the pathophysiology of hyperuricemia complicating diabetes [3].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Study Population Design

The foundational lipidomic study employed a carefully designed participant selection protocol [3]:

Participant Recruitment: 17 patients each diagnosed with DM and DH were selected from permanent residents aged 18 years and above in Fuzhou City, China, from June 2019 to July 2020, with 1:1 matching by sex and age, plus 17 healthy controls.

Inclusion Criteria: Participants were 18 years or older with completed questionnaires and blood collection, signed informed consent, and meeting American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria for diabetes (fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or random blood glucose >11.0 mmol/L). DH patients additionally exhibited fasting blood uric acid levels >420 μmol/L in men and >360 μmol/L in women.

Exclusion Criteria: Use of hypoglycemic agents; recent use of drugs affecting uric acid metabolism (diuretics, lipid-lowering drugs, aspirin, benzbromarone, allopurinol); diagnosis of gout, primary kidney disease, renal insufficiency, leukemia, or tumors; combination with psychiatric diseases or low cooperation; pregnancy and lactation.

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

The protocol for sample preparation followed rigorous standardized procedures [3]:

Blood Collection and Processing: 5 mL of fasting morning blood was collected and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature. The upper layer of plasma (0.2 mL) was aliquoted, with quality control samples created by mixing equal groups of samples.

Lipid Extraction: 100 μL of thawed plasma was mixed with 200 μL of 4°C water, then 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol was added. After mixing, 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) was added, followed by 20 minutes of sonication in a low-temperature water bath and 30 minutes of standing at room temperature.

Phase Separation: Centrifugation at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C separated the phases. The upper organic phase was collected and dried under nitrogen. The dried residue was reconstituted for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis.

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis Conditions

The analytical conditions for lipidomic profiling were comprehensively optimized [3]:

Chromatographic Conditions: Separation used a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of A: 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile solution in water and B: 10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile isopropanol solution.

Mass Spectrometry: The UHPLC system was coupled with tandem mass spectrometry, enabling high-sensitivity detection and quantification of lipid species. Quality control samples were randomly inserted into the analytical sequence to ensure data reliability.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for lipidomic profiling of diabetes with hyperuricemia (DH) versus diabetes alone (DM).

Metabolic Pathway Dysregulation

The lipidomic alterations observed in DH patients reflect coordinated disruptions in interconnected metabolic pathways:

Diagram 2: Dysregulated metabolic pathways and their clinical implications in DH versus DM.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomic Studies in Metabolic Disease

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Columns | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1×100mm, 1.7μm) | Lipid separation by hydrophobicity | Provides high-resolution separation of complex lipid mixtures |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | UHPLC-MS/MS with triple quadrupole or Q-Exactive Focus | Lipid identification and quantification | Enables untargeted lipidomics with high sensitivity |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), Methanol, Isopropanol | Lipid extraction from biological samples | MTBE/methanol/water system enables efficient lipid recovery |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Ammonium formate, Formic acid | Enhance ionization efficiency in MS | Improves signal intensity and stability |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Mix of 54 deuterated lipid standards | Quantification normalization | Corrects for extraction and ionization variance |

| Quality Control Materials | Pooled plasma samples | Monitoring analytical performance | Identifies technical variability across batches |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

The distinct lipid signature characterizing DH patients provides crucial insights for both biomarker development and therapeutic targeting. The upregulation of specific TG, PE, and PC species in DH versus DM alone suggests that hyperuricemia exacerbates pre-existing lipid metabolic disturbances in diabetes through shared pathophysiological mechanisms. These findings align with broader research showing that lipidome alterations are associated with diabetes progression and complications [9] [13].

From a therapeutic perspective, the identified pathway perturbations—particularly in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism—offer potential intervention targets. The robustness of these findings across different analytical approaches strengthens their validity and suggests clinical relevance. Future research should focus on validating these lipid signatures in larger, diverse cohorts and exploring targeted interventions that specifically address the combined metabolic burden of diabetes with hyperuricemia.

Comprehensive lipidomic profiling reveals a distinct signature of upregulated TGs, PEs, and PCs in patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia compared to those with diabetes alone. These lipid alterations, enriched in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways, provide a molecular basis for the exacerbated metabolic dysregulation observed in the combined condition. The standardized experimental protocols and analytical workflows presented here offer a robust framework for future investigations into lipid-mediated mechanisms in metabolic disease, potentially guiding the development of targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for this high-risk patient population.

Lipidomics has unveiled distinct dysregulation in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism in patients with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hyperuricemia (HU) compared to those with T2DM alone. This comparison guide synthesizes evidence from mass spectrometry-based lipidomic profiles to objectively delineate these differences. Data demonstrate that the comorbid condition features a more pronounced perturbation of specific lipid species, including upregulated triglycerides (TGs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs), and an enhanced dysregulation of core metabolic pathways. This analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a structured overview of the specific lipid alterations and the experimental methodologies used to identify them.

The co-occurrence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hyperuricemia (HU) represents a significant clinical challenge, associated with amplified renal and cardiovascular risk [14] [15]. Dyslipidemia is a common feature in both conditions, but emerging lipidomic technologies reveal that the specific nature of lipid disturbances differs substantially between patients with T2DM alone and those with T2DM and HU. A recent study reported a striking 81.6% prevalence of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia co-occurrence in a cohort of patients with uncontrolled T2DM, underscoring the clinical importance of this metabolic intersection [14] [15]. Beyond conventional lipid panels, advanced lipidomics can identify hundreds of individual lipid species, providing a more nuanced understanding of the underlying pathophysiology. Specifically, glycerophospholipid metabolism and glycerolipid metabolism have been identified as the two most significantly perturbed pathways in patients with comorbid T2DM and HU [10]. This guide compares the lipidomic profiles between these patient groups, summarizes key experimental data, and details the methodologies enabling these discoveries.

Comparative Lipidomic Profiles: Diabetes with Hyperuricemia vs. Diabetes Alone

Direct comparative lipidomics reveals a distinct signature in patients with concomitant disease. A 2025 untargeted lipidomic study that compared patients with T2DM and HU (the DH group) against those with T2DM alone (the DM group) and healthy controls (NGT) identified a specific set of differentially expressed lipids [10].

Table 1: Key Differential Lipid Species in DH vs. DM and NGT Groups [10]

| Lipid Class | Specific Lipid Molecules (Examples) | Trend in DH vs. NGT | Trend in DH vs. DM | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 others | Significantly Upregulated | Information Missing | 13 TGs were significantly elevated in DH compared to NGT. |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 others | Significantly Upregulated | Information Missing | 10 PEs were significantly elevated in DH compared to NGT. |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 others | Significantly Upregulated | Information Missing | 7 PCs were significantly elevated in DH compared to NGT. |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not Specified | Significantly Downregulated | Information Missing | One PI was significantly downregulated in DH. |

| Glycerophospholipid Pathway | N/A | Significantly Enriched | Significantly Enriched | Most significantly perturbed pathway (Impact value: 0.199). |

| Glycerolipid Pathway | N/A | Significantly Enriched | Significantly Enriched | Second significantly perturbed pathway (Impact value: 0.014). |

Another study investigating T2DM with hyperlipidemia, a condition closely related to HU, also found significant lipid disparities. When comparing the T2D HL (hyperlipidemia) group to the T2D group, 22 lipids from 4 lipid classes were differentially expressed, with the glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway being significantly affected [16]. This consistent identification of glycerophospholipid disruption across studies highlights its central role in the pathology of complicated diabetes.

Furthermore, a study on serum uric acid (SUA) correlation in T2DM patients found that SUA had a strong positive correlation with triglycerides (TG) (( rs = 0.65, p < 0.0001 )) and a significant negative correlation with HDL-C (( rs = -0.35, p < 0.0001 )) [17]. This reinforces the close relationship between uric acid levels and specific components of the glycerolipid profile.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

The lipidomic data presented rely on sophisticated analytical platforms. The following workflow outlines the typical process for the untargeted lipidomic studies cited.

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Study Population and Sample Collection

The core comparative study recruited 17 patients each for the Diabetes with Hyperuricemia (DH), Diabetes Mellitus (DM), and Normal Glucose Tolerance (NGT) groups, matched for sex and age [10]. Similar studies collected fasting venous blood from participants. Plasma or serum was obtained by centrifugation (e.g., 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes) and stored at -80°C until analysis to preserve lipid integrity [10] [18].

Lipid Extraction and Pre-processing

The preferred method for lipid extraction is often a liquid-liquid technique. As detailed in the research:

- A 100 μL plasma sample is vortexed after adding 200 μL of 4°C water [10].

- 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol is added, followed by 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) for liquid-liquid extraction [10].

- The mixture is sonicated in a low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes and left to stand at room temperature for 30 minutes [10].

- After centrifugation (e.g., 14,000 g, 15 min, 10°C), the upper organic phase is collected and dried under a nitrogen stream [10]. The dried lipids are then reconstituted in an appropriate solvent like isopropanol for instrumental analysis [10].

Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) is the cornerstone technology for untargeted lipidomics due to its high sensitivity and wide analytical range [10] [16].

- Chromatography: Separation is typically performed on a reversed-phase column, such as a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm). The mobile phase often consists of acetonitrile/water mixtures and acetonitrile/isopropanol mixtures, both with additives like 10 mM ammonium formate [10].

- Mass Spectrometry: Analysis is conducted in both positive and negative ionization modes to capture a broad spectrum of lipids. Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) modes like MSE are employed to collect comprehensive MS and MS/MS data for all ions, reducing false negatives [16].

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

- Multivariate Analysis: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) are used to visualize group separation and identify lipids contributing most to the variance [10] [19].

- Differential Lipid Screening: Statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test) combined with Fold Change (FC) analysis are applied to pinpoint significantly altered lipid molecules [10].

- Pathway Analysis: Platforms such as MetaboAnalyst 5.0 are used to map the dysregulated lipids onto metabolic pathways (e.g., KEGG) to identify significantly perturbed pathways based on impact and p-values [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successfully conducting these lipidomic comparisons requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-MS/MS System | High-resolution separation and accurate mass detection of complex lipid mixtures. | Core analytical platform used in comparative studies [10]. |

| Methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) | Organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction of a wide range of lipid classes. | Used in the MTBE-based lipid extraction method [10] [16]. |

| Reversed-Phase UPLC Column (e.g., C18) | Chromatographic separation of individual lipid species prior to mass spectrometry. | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm particle size) [10]. |

| Ammonium Formate / Formic Acid | Mobile phase additives to improve ionization efficiency and chromatographic resolution. | 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile/water and acetonitrile/isopropanol [10]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Pooled sample aliquots injected at regular intervals to monitor instrument stability and data quality. | Randomly inserted into the sample sequence to ensure analytical reproducibility [10] [18]. |

| Metabolic Pathway Analysis Software | Bioinformatics tool for interpreting lipidomic data in a biological context. | MetaboAnalyst 5.0 platform for pathway enrichment analysis [10]. |

Dysregulated Metabolic Pathways: A Visual Synthesis

The convergence of lipidomic data points to specific dysregulated metabolic pathways. The following diagram synthesizes the key findings regarding glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism in the context of diabetes and hyperuricemia.

The diagram illustrates how insulin resistance, a hallmark of T2DM often quantified by the Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) index [20], drives the dysregulation. This leads to increased flux through both the glycerolipid pathway (producing TGs) and the glycerophospholipid pathway, resulting in the characteristic elevation of PCs and PEs, and the observed decrease in PI, as seen in patients with comorbid diabetes and hyperuricemia [10] [16].

In the evolving landscape of metabolic disease research, the investigation of lipidomic profiles has unveiled critical insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying disease progression. This comparative analysis focuses on a particularly vulnerable population: younger patients presenting with concurrent diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia (HUA). Emerging evidence substantiates that early-onset phenotypes exhibit more profound lipid disruptions than their older counterparts or those with diabetes alone, suggesting a distinct metabolic trajectory with significant implications for prognosis and therapeutic targeting. The co-occurrence of diabetes and hyperuricemia represents a potent metabolic challenge, with dyslipidemia serving as a key intermediary in disease pathogenesis. Recent investigations have quantified the prevalence of this metabolic triad, revealing that dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia co-occur in 81.6% of patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, underscoring the clinical magnitude of this phenomenon [14]. This review synthesizes contemporary lipidomic evidence to delineate the specific lipid alterations characterizing younger patient cohorts, providing a foundation for precision medicine approaches in metabolic disease management.

Comparative Lipidomic Profiling: Young vs. Older Cohorts

Methodological Framework for Lipidomic Analysis

The foundational methodologies enabling precise lipidomic differentiation across patient cohorts involve sophisticated analytical platforms. A standardized protocol for plasma untargeted lipidomic analysis utilizes ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) to achieve comprehensive lipid separation and identification [3]. The technical workflow begins with plasma sample preparation via a monophasic extraction using isopropanol containing internal deuterated standards (e.g., SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard) for quantification accuracy [11]. Chromatographic separation employs reversed-phase columns (Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 or BEH C8, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) with mobile phases consisting of 10 mM ammonium formate in water (A) and 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-isopropanol (B) [3] [11]. Mass spectrometric detection using QTRAP 6500+ systems facilitates the semi-quantification of hundreds to thousands of lipid molecules across multiple subclasses, with data processing through specialized software (Analyst version 1.6.2) [11]. Multivariate statistical approaches, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), then enable differentiation of lipidomic profiles between patient groups with high accuracy (>95% for distinguishing early-onset hyperuricemia/gout from healthy controls) [11].

Table 1: Core Lipidomic Analysis Protocol

| Protocol Component | Specification | Application in Comparative Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Monophasic extraction with isopropanol + internal standards (deuterated lipids) | Ensures quantification accuracy across all patient cohorts |

| Chromatography | UHPLC with reversed-phase BEH C18/C8 columns (1.7 μm particle size) | Separates complex lipid mixtures from plasma samples |

| Mass Spectrometry | QTRAP 6500+ MS system with electrospray ionization | Detects and semi-quantifies 600+ lipid species |

| Data Processing | Analyst software (v1.6.2) with multivariate statistics (PCA, OPLS-DA) | Differentiates patient groups with >95% accuracy for early-onset phenotypes |

| Quality Control | Standard reference material (NIST SRM 1950) | Maintains analytical consistency across batch runs |

Lipidomic Alterations in Early-Onset Hyperuricemia and Diabetes

Comparative lipidomic profiling reveals substantial quantitative and qualitative differences in younger versus older patients with hyperuricemia, with parallel implications for diabetic populations. A comprehensive targeted lipidomic analysis of 608 plasma lipids demonstrated that both hyperuricemia and gout patients show significant alterations in lipid profiles, with the most profound changes observed in early-onset cases (age ≤40 years) [11]. The most significant perturbations include the upregulation of phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) and downregulation of lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogens/plasmanyls, with these alterations being markedly more pronounced in younger patients [11]. This pattern suggests accelerated glycerophospholipid metabolism dysregulation in early-onset disease, potentially contributing to more rapid disease progression and earlier development of complications. The distinct lipidomic signature of younger patients persists even after controlling for traditional risk factors, indicating that age of onset represents an independent determinant of metabolic phenotype severity.

Table 2: Lipid Class Alterations in Early-Onset vs. Late-Onset Metabolic Disease

| Lipid Class | Early-Onset Alteration (≤40 years) | Late-Onset Alteration (>40 years) | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | Significantly upregulated [11] | Moderately upregulated | Increased membrane fluidity, potential impact on insulin signaling |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine Plasmalogens | Significantly downregulated [11] | Moderately downregulated | Reduced antioxidant capacity, increased oxidative stress |

| Triglycerides (TGs) | Multiple species significantly elevated (e.g., TG 16:0/18:1/18:2) [3] | Selective elevation | Enhanced lipid storage, adipose tissue expansion |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | Significant upregulation (e.g., PC 36:1) [3] | Moderate changes | Altered membrane composition, potential cell signaling effects |

| Phosphatidylinositols (PIs) | Downregulated [3] | Minimal change | Disrupted intracellular signaling pathways |

Pathway-Level Disturbances in Younger Cohorts

Beyond discrete lipid class alterations, pathway analysis reveals systematic metabolic disturbances that distinguish younger patient cohorts. When comparing patients with diabetes combined with hyperuricemia (DH) against those with diabetes alone (DM) and healthy controls (NGT), multivariate analyses demonstrate significant separation trends among all three groups, confirming distinct lipidomic architectures [3]. Crucially, the collective analysis of 31 significantly altered lipid metabolites in DH patients reveals their enrichment in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways [3]. These pathway-level disturbances manifest more intensely in younger patients, suggesting that the co-occurrence of hyperuricemia and diabetes activates a feed-forward cycle of metabolic dysregulation that is particularly deleterious when established early in the lifespan. The identification of these pathway-specific perturbations provides a mechanistic foundation for understanding the accelerated disease trajectory observed in younger patients with concomitant metabolic conditions.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The lipidomic disruptions observed in younger patients with diabetes and hyperuricemia originate from interconnected molecular mechanisms that propagate metabolic dysfunction. The relationship between hyperuricemia and insulin resistance exhibits bidirectionality, with elevated uric acid promoting insulin resistance through oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and adipocyte dysregulation, while insulin resistance conversely contributes to elevated uric acid levels through reduced renal excretion [21]. At a cellular level, uric acid has been demonstrated to impair insulin signaling pathways by inhibiting IRS1 and Akt phosphorylation, thereby reducing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues [21]. Simultaneously, in hepatic models, uric acid induces fat accumulation by stressing the endoplasmic reticulum and activating sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), a master regulator of lipogenesis [11]. The resulting lipidomic landscape creates a pro-inflammatory milieu characterized by elevated ceramides and reduced cardioprotective lipid species, establishing a molecular environment conducive to accelerated vascular complications and microvascular damage. These mechanisms appear amplified in younger patients, potentially due to greater metabolic flexibility and more responsive (yet vulnerable) signaling networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Advancing research into early-onset lipid disruptions requires specialized reagents and analytical platforms designed for comprehensive lipidomic characterization. The following toolkit delineates essential resources for investigators in this field, compiled from methodologies employed in contemporary studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Lipidomic Investigation

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18/C8 columns (1.7μm) | Lipid separation | High-resolution separation of complex lipid mixtures |

| Mass Spectrometry | SCIEX QTRAP 6500+ LC-MS/MS System | Lipid identification and quantification | High-sensitivity detection of 600+ lipid species |

| Internal Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard | Quantification accuracy | Deuterated lipid standards across multiple classes |

| Reference Materials | NIST SRM 1950 - Metabolites in Frozen Human Plasma | Quality control | Standardized reference for method validation |

| Sample Preparation | Isopropanol extraction with MTBE | Lipid extraction | Efficient recovery of diverse lipid classes |

| Data Processing | Analyst Software (v1.6.2) | Data acquisition and processing | Instrument control and initial data processing |

| Statistical Analysis | MetaboAnalyst 5.0 Platform | Pathway analysis | Identification of perturbed metabolic pathways |

| Multivariate Statistics | SIMCA-P+ Software | OPLS-DA modeling | Differentiation of patient cohort lipidomic profiles |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The distinct lipidomic signature characterizing younger patients with concomitant diabetes and hyperuricemia carries significant implications for therapeutic strategy development and clinical management. Evidence suggests that urate-lowering treatment (ULT) may partially correct the lipidomic imbalance observed in early-onset cohorts, with studies demonstrating that ULT administration is associated with a normalization of specific lipid class alterations, particularly glycerophospholipids [11]. This effect highlights the potential for targeted metabolic interventions to modify disease trajectory in younger, high-risk patients. Beyond conventional urate-lowering approaches, emerging research indicates that pharmacological agents with pleiotropic metabolic effects, including SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, may simultaneously address hyperglycemia, hyperuricemia, and associated lipid disruptions through interconnected mechanisms [14] [22]. Future research directions should prioritize longitudinal studies tracking lipidomic evolution in response to targeted interventions, with particular emphasis on the window of opportunity presented by early-onset disease. Additionally, the integration of multi-omics approaches—combining lipidomics with genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—will enable more comprehensive phenotyping and personalized therapeutic approaches for younger patients exhibiting these profound lipid disruptions.

The comprehensive analysis of lipidomic profiles in patients with diabetes and hyperuricemia reveals a critical distinction between early-onset and late-onset phenotypes. Younger patients (≤40 years) demonstrate more profound disruptions across multiple lipid classes, particularly phosphatidylethanolamines, lysophosphatidylcholine plasmalogens, and triglycerides, with concomitant disturbances in glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways. These quantifiable differences, detectable via advanced UHPLC-MS/MS platforms, substantiate the concept of early-onset metabolic disease as a distinct clinical entity with accelerated pathophysiological progression. The delineation of these lipidomic signatures provides both prognostic insight and therapeutic opportunity, highlighting the imperative for age-specific management approaches in patients presenting with concomitant diabetes and hyperuricemia. As precision medicine continues to evolve, lipidomic profiling promises to enhance risk stratification and enable targeted interventions for this metabolically vulnerable population.

The study of complex metabolic diseases like diabetes and hyperuricemia has evolved beyond single-omics approaches, revealing the critical need for integrated analyses that connect lipidomic perturbations with genetic susceptibility and proteomic alterations. This integrated perspective is essential for unraveling the multifaceted pathophysiology of diabetes with hyperuricemia (DH) compared to diabetes alone (DM). Lipidomics, which provides a comprehensive profile of lipid species within a biological system, serves as a crucial bridge between genetic predispositions and functional protein effects. When combined with proteomic and genetic data, lipidomic profiles transform from mere biomarkers into powerful tools for understanding disease mechanisms, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and developing personalized treatment strategies for metabolic disorders.

Lipidomic Perturbations in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia vs. Diabetes Alone

Distinct Lipidomic Profiles Revealed by Untargeted Analysis

Comprehensive lipidomic analyses reveal significant alterations in plasma lipid metabolites between patients with diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH) and those with diabetes alone (DM). Using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS), researchers have identified 1,361 lipid molecules across 30 subclasses, demonstrating a clear separation in lipidomic profiles between DH, DM, and normal glucose tolerance (NGT) groups [10].

Table 1: Significantly Altered Lipid Classes in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia vs. Diabetes Alone

| Lipid Class | Representative Lipid Species | Change in DH vs. DM | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) | ↑ Significantly upregulated | Associated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) | ↑ Significantly upregulated | Membrane fluidity and signaling alterations |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) | ↑ Significantly upregulated | Disrupted membrane integrity and signaling |

| Phosphatidylinositols (PIs) | Not specified | ↓ Downregulated | Impaired intracellular signaling |

| Sphingolipids | Sphingosine(d16:0) | ↑ In insulin resistance | Associated with IR in obesity [23] |

| Coenzyme | Coenzyme(Q8) | ↑ In insulin resistance | Mitochondrial dysfunction [23] |

Multivariate analyses including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) have confirmed distinct lipidomic separation between these patient groups, highlighting the profound impact of hyperuricemia on lipid metabolism in diabetic individuals [10]. The collective analysis of these altered metabolites reveals their enrichment in six major metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) identified as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [10].

Pathway Analysis and Metabolic Implications

The integration of lipidomic data with pathway analysis tools such as MetaboAnalyst 5.0 has been instrumental in identifying the core metabolic disruptions in diabetes with hyperuricemia. The discovery that glycerophospholipid and glycerolipid metabolism pathways are significantly perturbed in DH patients provides crucial insights into the mechanistic links between hyperuricemia and lipid dysregulation in diabetes [10].

These pathway disturbances correlate with clinical observations of accelerated renal and cardiovascular damage in diabetic patients with concomitant hyperuricemia. The upregulation of specific triglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylcholines suggests enhanced lipogenesis and membrane remodeling processes that may contribute to the progression of diabetic complications [10]. Furthermore, the downregulation of phosphatidylinositols indicates potential disruptions in intracellular signaling cascades that are critical for insulin action and metabolic homeostasis.

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Lipidomic Profiling Methodology

The standard workflow for lipidomic analysis in metabolic disease research involves several critical steps that ensure comprehensive lipid coverage and accurate quantification:

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Collect 5 mL of fasting morning blood in EDTA-coated tubes and centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature [10].

- Plasma Separation: Aliquot 0.2 mL of the upper plasma layer into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes and store at -80°C until analysis [10].

- Lipid Extraction: Thaw samples on ice and vortex. Take 100 μL and add 200 μL of 4°C water followed by 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol. Add 800 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), sonicate for 20 minutes in a low-temperature water bath, and incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes [10].

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C. Collect the upper organic phase and dry under nitrogen stream [10].

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried lipids in 100 μL of isopropanol for UHPLC-MS/MS analysis [10].

UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis Conditions:

- Chromatography: Utilize a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) with mobile phase A (10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile solution in water) and mobile phase B (10 mM ammonium formate acetonitrile isopropanol solution) [10].

- Mass Spectrometry: Perform analysis using a tandem mass spectrometry system with electrospray ionization in both positive and negative ion modes to maximize lipid coverage [10].

- Quality Control: Insert quality control samples randomly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument performance and data quality [10].

Proteomic Integration Protocols

The integration of proteomic data with lipidomic profiles requires specialized approaches to identify protein-lipid networks:

Proteomic Data Acquisition:

- Multiplex Proteomic Assays: Utilize high-throughput proteomic platforms such as the Olink platform to quantify hundreds of proteins simultaneously in plasma samples [23].

- Protein Correlation Networks: Apply weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify modules of co-expressed proteins that correlate with clinical phenotypes [24].

Integrated Analysis Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize both lipidomic and proteomic datasets, impute missing values using k-nearest neighbor imputation, and apply inverse normal transformation to account for technical variability [24].

- Network Construction: Build weighted lipid and protein co-expression networks using appropriate similarity measures and identify modules of tightly correlated molecules [24].

- Module-Phenotype Correlation: Correlate module eigenvalues with clinical traits such as disease status, progression, and relevant biochemical parameters [24].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Employ gene ontology enrichment analysis to examine biological processes and molecular functions of protein modules associated with disease phenotypes [24].

Figure 1: Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for Lipidomic and Proteomic Data in Metabolic Disease Research

Proteomic Correlates of Lipidomic Perturbations in Metabolic Disease

Key Protein Biomarkers and Their Clinical Utility

Integrated proteomic and lipidomic analyses have identified specific protein biomarkers that strongly correlate with lipid disturbances in metabolic diseases including diabetes with hyperuricemia. These proteins not only serve as diagnostic markers but also provide insights into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Table 2: Protein Biomarkers Associated with Lipidomic Perturbations in Metabolic Disease

| Protein Biomarker | Full Name | Expression in IR/DH | AUROC Value | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FABP4 | Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 | Overexpressed | Not specified | Lipid chaperone, inflammation |

| PAI | Serpin Family E Member 1 | Overexpressed | 0.65 | Fibrinolysis inhibition |

| IGFBP-1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 | Lower expression | 0.89 | IGF regulation, glucose metabolism |

| PON3 | Paraoxonase 3 | Lower expression | 0.81 | Antioxidant protection |

| Adiponectin | Adiponectin | Lower expression | Less than IGFBP-1/PON3 | Insulin sensitization |

The diagnostic performance of these protein biomarkers often surpasses traditional metabolic indicators. For instance, IGFBP-1 demonstrated an AUROC of 0.89 for diagnosing insulin resistance, significantly higher than adiponectin (AUROC 0.67) and leptin (AUROC 0.65) [23]. Similarly, PON3 showed an AUROC of 0.81, highlighting the superior diagnostic capability of these proteomic markers derived from integrated omics analyses [23].

Network Analysis of Protein-Lipid Interactions

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) of integrated proteomic and lipidomic data has revealed functionally significant modules associated with metabolic diseases. Studies in Alzheimer's disease (as a model of complex metabolic disorder) have identified five key protein modules out of seventeen that correlate with disease phenotypes, involving processes such as positive regulation of cytokine production, neutrophil-mediated immunity, and humoral immune responses [24].

Similarly, lipid modules comprising phospholipids, triglycerides, sphingolipids, and cholesterol esters have shown significant correlations with disease risk loci involved in immune response and lipid metabolism [24]. These network-based approaches demonstrate how integrated omics analyses can reveal organized functional modules rather than just individual biomarkers, providing a systems-level understanding of metabolic diseases including diabetes with hyperuricemia.

Genetic Susceptibility and Multi-Omics Integration

Genetic Loci Influencing Lipidomic Profiles

The integration of genomic data with lipidomic and proteomic profiles has revealed how genetic susceptibility loci influence lipid metabolism in metabolic diseases. Network analyses have demonstrated significant associations between established disease risk loci and specific lipid/protein modules that correlate with clinical phenotypes [24].

For instance, specific lipid modules comprising phospholipids, triglycerides, sphingolipids, and cholesterol esters have been correlated with risk loci involved in immune response and lipid metabolism [24]. Similarly, protein modules involved in immune responses show correlations with risk loci in the complement system and lipid metabolism, including the APOE ε4 genotype [24]. These findings highlight how genetic susceptibility can shape both the proteomic and lipidomic landscape in metabolic diseases.

Mendelian Randomization and Causal Inference

Advanced statistical approaches such as Mendelian randomization can leverage genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between lipid species and disease outcomes. This approach helps distinguish between causal lipid mediators and reactive changes in the disease process, providing valuable insights for therapeutic target prioritization.

While the specific search results don't provide detailed Mendelian randomization analyses in diabetes with hyperuricemia, the network analysis approaches described demonstrate the principle of using genetic data to inform lipidomic and proteomic associations [24]. Future studies specifically applying Mendelian randomization to the DH vs. DM comparison would strengthen causal inference in the observed lipidomic differences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column | Lipid separation | 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particles |

| Mass Spectrometry | UHPLC-MS/MS with ESI source | Lipid identification and quantification | High resolution, positive/negative mode switching |

| Proteomic Platforms | Olink Proteomics | Multiplex protein quantification | High-throughput, plasma proteomics |

| Proteomic Platforms | SOMAscan (SomaLogic) | Aptamer-based protein detection | 1016 protein targets with Uniprot ID [24] |

| Bioinformatics | MetaboAnalyst 5.0 | Pathway analysis | Lipid pathway enrichment, network visualization |

| Bioinformatics | WGCNA R Package | Co-expression network analysis | Module identification, phenotype correlation |

| Statistical Analysis | IBM SPSS Statistics v30 | Statistical modeling | Logistic regression, ROC analysis |

| Specialized Reagents | Potassium Oxonate (PO) | Hyperuricemia induction | Uricase inhibitor, 350 mg/kg dose [5] |

Visualization and Data Representation in Multi-Omics Studies

Effective visualization of integrated omics data requires careful consideration of design principles to accurately communicate complex relationships. Key guidelines include maximizing the data-ink ratio by eliminating non-data ink and redundant elements [25]. This principle emphasizes that every bit of ink (or pixels) in a visualization should present new information, leading to cleaner and more effective graphics.

Additional critical guidelines include:

- Self-explanatory visualizations: Figures should include clear titles, axis labels with units, and sufficient context to be understood without excessive reference to the main text [25].

- Meaningful baselines: Axes, particularly in bar charts, should start at appropriate baselines (usually zero) to avoid distorting data patterns [25].

- Direct labeling: Instead of legends, label elements directly when possible to avoid indirect look-up and facilitate faster comprehension [25].

- Colorblind-aware palettes: Approximately 8% of males worldwide have color vision deficiency, necessitating careful color selection that differentiates by saturation and brightness rather than just hue [25].

Figure 2: Multi-Omics Network Linking Genetic Susceptibility to Clinical Outcomes in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia

The integration of lipidomic data with genetic and proteomic susceptibility information represents a transformative approach to understanding complex metabolic diseases like diabetes with hyperuricemia. The distinct lipidomic signatures observed in DH compared to DM alone, characterized by elevations in specific triglycerides, phosphatidylethanolamines, and phosphatidylcholines, along with corresponding proteomic alterations in proteins like FABP4, PAI, IGFBP-1, and PON3, provide a comprehensive molecular portrait of this metabolic phenotype.

The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks described herein, including UHPLC-MS/MS lipidomics, multiplexed proteomics, and WGCNA network analysis, provide researchers with robust methodologies for conducting integrated omics studies. The essential research tools and visualization principles further support the generation and communication of high-quality multi-omics data.

Future directions in this field will likely include larger-scale longitudinal studies to establish temporal relationships between omics changes and disease progression, as well as interventional studies to determine how these integrated omics profiles respond to treatment. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated computational methods for multi-omics data integration will enhance our ability to extract biologically meaningful insights from these complex datasets, ultimately advancing personalized approaches to managing diabetes and its metabolic comorbidities.

Advanced Lipidomics in Practice: From Mass Spectrometry to Biomarker Panels

Lipidomics, defined as the systems-level analysis of lipids and their interactors, has become an essential strategy for understanding the mechanisms underlying cellular signaling, metabolism, and homeostasis [26]. In the context of metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperuricemia, lipidomics provides powerful insights into pathological mechanisms and potential diagnostic signatures [3] [26]. The biological significance of lipids in multiple physio-pathological events has driven the development of lipidomics as a discipline, with technological innovations enabling increasingly comprehensive analysis of the lipidome [27]. Within this field, two primary analytical paradigms have emerged: untargeted (hypothesis-generating) and targeted (hypothesis-driven) lipidomics [28]. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) has become the cornerstone technology for both approaches, offering the sensitivity, selectivity, and throughput required for meaningful lipidomic profiling in complex biological matrices [3] [29] [30]. This guide objectively compares these core analytical platforms within the specific research context of comparing lipidomic profiles in diabetes with hyperuricemia versus diabetes alone.

Untargeted versus Targeted Lipidomics: A Strategic Comparison

Conceptual Frameworks and Applications

Untargeted and targeted lipidomics represent complementary approaches with distinct philosophical frameworks and application domains. Untargeted lipidomics employs a holistic analytical strategy to profile the complete lipid repertoire within biological specimens without prior selection of targets [28]. This hypothesis-free approach serves as a discovery tool to map lipid diversity, uncover novel metabolic pathways, and elucidate lipid functional networks across biological systems [28]. In contrast, targeted lipidomics adopts a hypothesis-driven methodology, focusing on precise quantification of predefined lipid panels [28]. Leveraging techniques such as Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), this approach prioritizes analytical rigor for specific lipid classes or molecules, delivering absolute quantification via internal standards [26] [28]. It is optimized for validating biomarkers, monitoring metabolic fluxes, and assessing therapeutic interventions [28].

In diabetes and hyperuricemia research, these approaches serve sequential purposes. Untargeted methods can identify novel lipid signatures associated with disease comorbidity, while targeted approaches enable rigorous validation and quantification of these candidates across larger patient cohorts [3] [28].

Technical Specifications and Performance Characteristics

The fundamental differences between these approaches are reflected in their technical implementations and performance characteristics, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Approaches

| Dimension | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning Mode | Full Scan + Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Selective Reaction Monitoring (SRM/MRM) |

| Target Scope | Global coverage (>1,000 lipids) | Specific targets (<100 to ~600 lipids) |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative (relative quantification) | Absolute quantification (standard curve method) |

| Sensitivity | Moderate | High (zeptomole detection limits) |

| Instrument Configuration | Q-TOF, Orbitrap (high resolution) | Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) |

| Data Analysis Core | Spectrum matching, fragment ion annotation | Ion pair optimization, internal standard correction |

| Typical Applications | Biomarker discovery, metabolic pathway analysis | Clinical diagnostics validation, drug monitoring |

| Advantages | Unbiased, high discovery power | High sensitivity, precise quantification |

| Limitations | Lower quantitative accuracy, database dependent | Poor scalability, inability to detect novel lipids |