Dynamic Programming in Protein Structural Alignment: From Foundational Algorithms to Cutting-Edge AI Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of dynamic programming (DP) strategies for protein structural alignment, a cornerstone technique in computational biology.

Dynamic Programming in Protein Structural Alignment: From Foundational Algorithms to Cutting-Edge AI Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of dynamic programming (DP) strategies for protein structural alignment, a cornerstone technique in computational biology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of DP, detailing its robustness and inherent limitations. The content delves into modern methodological advancements, including hybrid algorithms that combine DP with genetic algorithms and machine learning, as well as novel formulations using optimal transport. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects, such as parameter sensitivity and strategies to avoid local optima, and provides a rigorous framework for the validation and comparative analysis of alignment tools against established benchmarks. By synthesizing traditional approaches with the latest AI-driven innovations, this article serves as a vital resource for leveraging structural alignment to accelerate discoveries in protein function annotation, evolutionary studies, and drug design.

The Core Engine: Understanding Dynamic Programming's Role in Protein Structural Alignment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core recursive relation at the heart of the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm, and how does it enable global sequence alignment?

The core recursion for the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm, which performs global sequence alignment, is defined for a matrix F where F[i, j] represents the score of the optimal alignment between the first i characters of sequence A and the first j characters of sequence B [1]. The recurrence relation is calculated for each cell (i, j) as follows [1] [2]:

F[i, j] = max( F[i-1, j-1] + S(A_i, B_j), F[i-1, j] + gap, F[i, j-1] + gap )

Where:

F[i-1, j-1] + S(A_i, B_j)represents a match or mismatch, whereS(A_i, B_j)is the similarity score between charactersA_iandB_j[1].F[i-1, j] + gaprepresents an insertion of a gap in sequence B (a deletion from sequence A) [1].F[i, j-1] + gaprepresents an insertion of a gap in sequence A (a deletion from sequence B) [1].

This relation breaks the problem into smaller subproblems, and by solving and storing their solutions in a matrix (a process central to dynamic programming), it constructs the optimal full alignment [3] [4]. The algorithm guarantees finding the alignment with the highest possible score across the entire length of both sequences [3].

FAQ 2: How does the fundamental DP recursion extend from sequence alignment to protein structural alignment?

In protein structural alignment, the fundamental DP concept remains the same, but the "similarity score" S(i, j) is replaced by a measure of three-dimensional structural similarity between residues i and j, often based on the spatial coordinates of their Cα atoms [5] [6]. The recursion maximizes the sum of structural similarity scores instead of sequence similarity scores [6].

A common recursion form for structural alignment is [6]:

V_{ij} = min( V_{i-1,j} + ρ, V_{i,j-1} + ρ, V_{i-1,j-1} + S_{ij} )

Here, S_{ij} is a structural similarity measure, and ρ is a gap penalty. This allows the algorithm to find spatially equivalent residue pairs between two protein structures, which is critical for inferring functional, structural, and evolutionary relationships that are not always evident from sequence alone [5] [6].

FAQ 3: What are the advantages of using a bottom-up dynamic programming approach over a top-down recursive approach with memoization?

The primary advantages are reduced space complexity and a guaranteed optimal computation order [4] [7].

- Bottom-Up Approach: The computation starts from the smallest subproblems and iteratively builds up to the main problem. This allows for careful management of memory, as only the immediately required previous solutions need to be stored. For example, in the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm, the entire

m x nmatrix is filled, but for problems like Fibonacci or the House Robber, only the last two results are needed, resulting in constant space complexity, O(1) [4]. - Top-Down Approach (Memoization): The algorithm starts with the main problem and recursively breaks it down, caching the results of subproblems to avoid recomputation. While this avoids redundant calculations, it still requires storing all subproblem solutions (O(n) or O(mn) space) and incurs the overhead of recursive function calls [4].

For researchers, the bottom-up approach is often preferred in structural bioinformatics for its efficiency and straightforward implementation when the order of subproblem evaluation is clear [4] [7].

FAQ 4: My structural alignment algorithm is highly sensitive to small changes in the gap penalty parameter. How can I improve its robustness?

Sensitivity to parameters like gap penalty is a known challenge. Research indicates that DP-based solutions can be inherently robust to parametric variation within certain ranges [6]. A study on the EIGAs structural alignment algorithm showed it remained highly effective at identifying similar proteins over a breadth of parametric values [6].

To improve robustness in your experiments:

- Use an Affine Gap Penalty: Instead of a single gap penalty

ρ, use two parameters:ρ_ofor initiating a gap andρ_cfor continuing a gap. This model is more biologically realistic as extending a gap is often considered less penalizing than starting a new one. However, this adds a parameter that may require tuning [6]. - Parameter Sweeping: Systematically test a range of parameter values and evaluate the resulting alignments against a benchmark dataset of known structural relationships to identify a stable, effective range for your specific application [6].

FAQ 5: What are the key software tools and visualizers available for debugging and understanding DP algorithms in bioinformatics?

Several tools can help visualize and debug the DP matrix filling process, which is crucial for learning and troubleshooting.

Table: Key Dynamic Programming Visualization and Analysis Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Functionality | Key Features / Benefits | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| dpvis [7] | A Python library for visualizing DP algorithms. | Step-by-step animation; Interactive self-testing mode; Minimal code modification required. | Requires initial setup in a Python environment. |

| VisuAlgo [8] | Web-based visualization of recursion trees and DAGs. | Shows the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) of subproblems; Illustrates dramatic search-space difference. | The DAG can become cluttered for larger problems. |

| Easy Hard DP Visualizer [7] | Visualizes 1D/2D DP subproblem arrays from JavaScript code. | Highlights dependencies for each subproblem. | Lacks rewind/pause features for specific frames. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Optimal Alignments or Incorrect Scores

This issue arises when the DP algorithm does not find the correct optimal alignment, leading to biologically implausible results.

- Step 1: Verify the Scoring System. Check that the values in your similarity matrix

Sand the gap penaltyρare appropriate for your data (e.g., protein vs. DNA). A mismatch in scoring semantics can completely alter the outcome [1]. - Step 2: Check the Recurrence Relation Implementation. Manually trace the calculation of a few cells in your DP matrix, especially where a branching decision (diagonal, left, or up) occurs. Ensure the

max(ormin) function is correctly implemented and that all three terms are being considered [1]. - Step 3: Validate the Traceback Procedure. The optimal path might be correct, but an error in the traceback can produce a wrong alignment. Ensure you correctly handle branches if multiple paths lead to the optimal score [1]. Use a visualization tool like dpvis or VisuAlgo to step through the matrix filling and traceback process [8] [7].

Issue 2: Unacceptable Computational Performance for Large Structures

Protein structural comparisons can be computationally intensive, scaling with the product of the sequence lengths, O(mn) [1] [6].

- Step 1: Profile Your Code. Identify bottlenecks. The DP matrix filling itself is inherently O(mn), but expensive distance calculations for

S_{ij}in structural alignment can be a major slowdown [6]. - Step 2: Consider Heuristic Pre-Filtering. For large database searches, use a fast, less accurate algorithm (e.g., a 0D "finger-print" method like FragBag that compares histograms) to filter out obviously dissimilar structures before running the accurate, slower DP algorithm [6].

- Step 3: Explore Algorithmic Optimizations. Investigate the use of GPUs, as some studies report significant speedups (e.g., 36-fold for TM-align) by porting the computationally intensive parts to a graphics card [6].

Issue 3: Algorithm Fails to Handle Non-Sequential Alignments

A key limitation of classical sequential DP is its inability to find non-sequential alignments, where the order of residues in the backbone is not preserved, which is important in some protein comparisons [6].

- Potential Solution 1: Investigate Alternative Algorithms. Classical DP iterates sequentially along the backbone. Future research could investigate adapting DP to iterate in a different order or using bipartite graph matching in place of DP to obtain non-sequential alignments [6].

- Potential Solution 2: Use Specialized Structural Aligners. For production work requiring non-sequential alignment, rely on established, specialized algorithms that are designed to handle such cases, though they may be slower [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Quantitative Data for Common Scoring Parameters

Table: Example Scoring Schemes for Needleman-Wunsch Algorithm [1]

| Scoring Scheme Purpose | Match Score | Mismatch Score | Gap Penalty (ρ) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Similarity | +1 | -1 | -1 | The original scheme used by Needleman and Wunsch. |

| Edit Distance | 0 | -1 | -1 | The final alignment score directly represents the edit distance. |

| Heavy Gap Penalization | +1 | -1 | -10 | Useful when gaps are considered highly undesirable in the alignment. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational "Reagents" for DP-Based Alignment

| Item / Concept | Function / Explanation | Example in Bioinformatics |

|---|---|---|

| Similarity Matrix (S) | A lookup table that defines the score for aligning any two residues (or nucleotides) with each other. It encodes biological likelihood [1] [2]. | BLOSUM, PAM matrices for amino acids; Identity matrix for simple DNA matches [2]. |

| Gap Penalty (ρ) | A cost deducted from the alignment score for introducing a gap (insertion or deletion). It can be constant (linear) or variable (affine) [1] [6]. | A linear penalty of -2; An affine penalty with open=-5 and extend=-1. |

| DP Matrix (F or V) | A two-dimensional array that stores the optimal scores for all subproblems (alignments of sequence prefixes). The solution is built by filling this matrix [1] [7]. | The core data structure in Needleman-Wunsch and many structural alignment algorithms like EIGAs. |

| Traceback Matrix | An auxiliary data structure (often integrated into the DP matrix) that records the path taken to reach each cell, enabling the reconstruction of the optimal alignment [1]. | Stores arrows pointing to the parent cell (diagonal, left, or up). |

Mandatory Visualizations

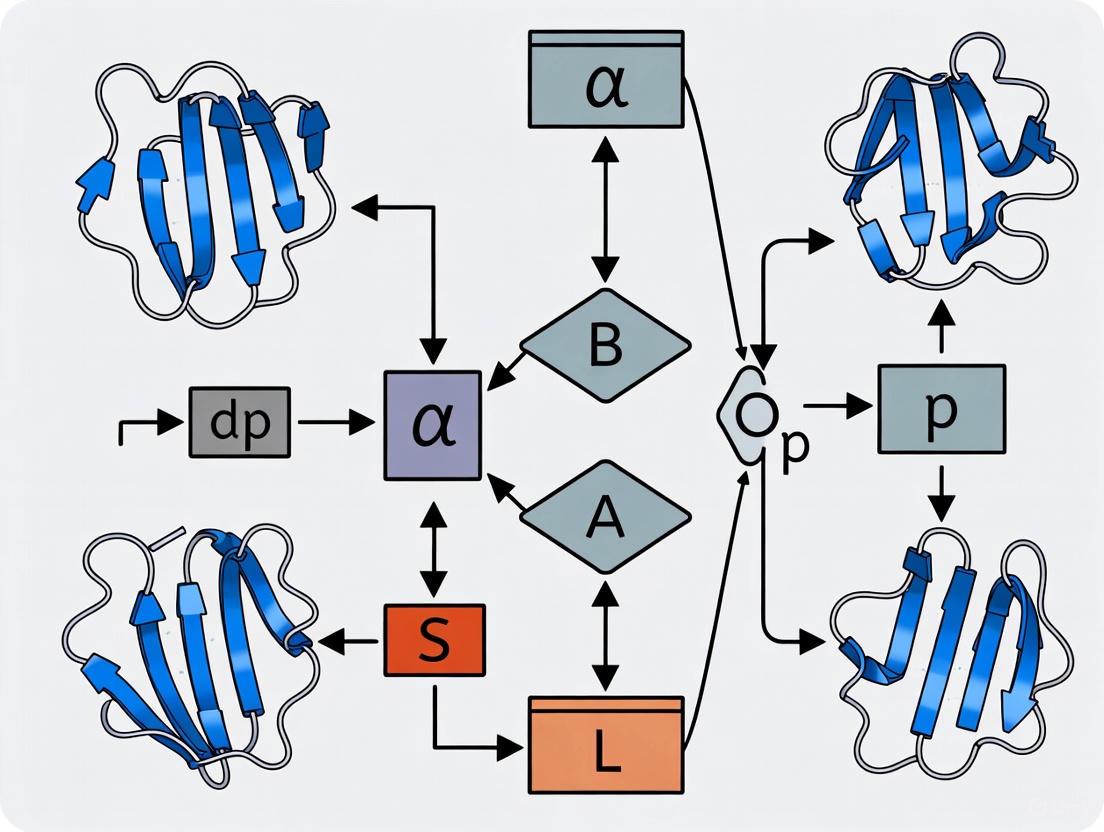

Diagram: DP Alignment Workflow

Diagram: From Sequence to Structure Alignment

Why DP? Addressing the NP-Hard Challenge of Residue Correspondence

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is finding the optimal residue correspondence considered NP-hard? The problem requires evaluating all possible mappings between the residues of two protein structures to find the set that maximizes structural similarity after optimal superposition. An exhaustive search of this solution space is computationally intractable for all but the smallest proteins, as the number of possible alignments grows exponentially with protein length, placing it in the NP-hard complexity class [9] [10].

If the problem is NP-hard, how can Dynamic Programming (DP) provide a solution? DP does not solve the NP-hard problem in its entirety. Instead, it efficiently finds the optimal sequence-order preserving alignment for a given scoring function. It works by breaking the problem into smaller, overlapping subproblems (aligning protein prefixes), solving each once, and storing the solution. This avoids redundant computations but relies on a pre-defined scoring scheme to compare residues and is typically restricted to alignments where the residue order is preserved [6] [10].

My DP-based alignment has a low RMSD but a poor TM-score. What does this mean? This indicates that your alignment, while geometrically precise for a small subset of residues (low RMSD), fails to capture a large, biologically meaningful structural core. Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is sensitive to local deviations and can be inflated by poorly aligned regions. The Template Modeling Score (TM-score) is a length-normalized measure that is more sensitive to global topology. A low TM-score suggests the aligned regions may not represent a significant fold similarity, often with scores below 0.2 indicating randomly unrelated proteins [11] [12].

What can I do if my proteins have the same fold but different domain connectivity (e.g., circular permutations)? Standard DP, which requires sequential residue matching, will fail in this scenario. You should use algorithms specifically designed for non-sequential or flexible alignments. Tools like jCE-CP (Combinatorial Extension with Circular Permutations) or the flexible version of jFATCAT are capable of detecting similarities in proteins with different topologies [11].

How can I escape local optima during structural alignment? Relying solely on a single initial guess for correspondence can trap an algorithm in a local optimum. Advanced methods combine DP with global search heuristics. For example, the GADP-align algorithm uses a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to explore a wide range of initial alignments globally before refining them with iterative DP, thereby reducing the risk of local traps [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High Sensitivity to Gap Penalty Parameters

- Symptoms: Small changes in gap opening (

ρ_o) or extension (ρ_c) penalties lead to dramatically different alignments. - Underlying Cause: The DP scoring function is overly sensitive to the chosen parameters, making the alignment unstable.

- Solution:

- Robustness Testing: Run your alignment across a range of gap penalties and observe if the core aligned regions remain stable. Algorithms like EIGAs have been shown to be robust across a breadth of parametric values [6].

- Use a Size-Independent Score: Employ a scoring function like TM-score for evaluation, as it is less sensitive to protein size and alignment length [9] [12].

- Consult Literature: Use gap penalty values that are standard for your chosen algorithm or have been validated in benchmark studies.

Problem: Inaccurate Alignment for Proteins with Low Sequence Identity

- Symptoms: The alignment fails to identify obvious structural similarities between proteins with no detectable sequence relationship.

- Underlying Cause: The scoring function for residue similarity may be overly reliant on sequence-derived information.

- Solution:

- Leverage Structural Information: Use algorithms that define residue similarity based on structural fingerprints, such as local fragment geometry [6] or the alignment of Secondary Structure Elements (SSEs) [9].

- Apply Consistency Transformation: Pre-process with methods that enhance the residue affinity matrix by incorporating information from all pairwise alignments in a set, which improves accuracy for distant homologs [13].

- Choose the Right Tool: Opt for methods known for sequence-independent alignment, such as TM-align or DALI [11] [12] [10].

Problem: Long Computation Times for Large-Scale Database Comparisons

- Symptoms: An all-against-all comparison of a large set of protein structures is computationally prohibitive.

- Underlying Cause: Classical structural alignment algorithms (DALI, CE, SSAP) are accurate but can be too slow for database-scale applications [6].

- Solution:

- Employ Fast Filtering Algorithms: Use efficient "1D" or "0D" algorithms like FragBag (which uses a histogram of backbone fragments) as a pre-filter to identify potential matches before running a more accurate, slower aligner [6].

- Utilize Hybrid Methods: Implement algorithms like CATHEDRAL, which combine a fast secondary structure-based search with a more precise double-dynamic programming algorithm [6].

- Leverage Hardware Acceleration: Some implementations of algorithms like TM-align have been modified to run on GPUs, providing significant speedups [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Methodology: The GADP-align Hybrid Protocol

This protocol combines a Genetic Algorithm (GA) with iterative Dynamic Programming to find a global alignment [9].

- Initial SSE Matching: Encode the secondary structure of each protein as a sequence of elements (H for helix, S for strand). Use the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm to generate an initial correspondence between these SSE sequences.

- Genetic Algorithm Population Initialization: Create a population of chromosomes. Each chromosome represents a possible alignment, defined by matched SSE pairs and a random set of corresponding residues within those SSEs.

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculate the fitness of each chromosome using the TM-score after applying the optimal superposition based on its proposed residue correspondence.

- Genetic Operations:

- Selection: Use tournament selection to choose parent chromosomes.

- Crossover: Combine segments of two parent chromosomes to produce offspring.

- Mutation: Randomly increase or decrease the number of aligned residues within an SSE pair.

- Shift: Shift SSE correspondences left or right to explore new matchings.

- Dynamic Programming Refinement: For the highest-scoring chromosomes, run an iterative DP algorithm to refine the residue-level alignment and compute the final Kabsch transformation for superposition.

- Termination: The algorithm terminates when the maximum fitness score remains unchanged for 30 generations or after 100 generations.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key metrics for evaluating structural alignments, as used by tools like those on the RCSB PDB site [11] and in research [9].

| Metric | Description | Interpretation | Typical Values for Related Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| TM-score | Measures topological similarity, normalized by protein length. | 0-1 scale; <0.2: random, >0.5: same fold [11] [12]. | >0.5 |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation of superposed Cα atoms. | Lower is better, but sensitive to local errors and length. | < 2.0 - 4.0 Å |

| Aligned Length | Number of residue pairs in the final alignment. | Larger values generally indicate greater similarity. | Varies with protein size and similarity. |

| Sequence Identity | Percentage of aligned residues that are identical. | Not a structural metric, but provides evolutionary context. | Can be very low (<20%) even with high TM-score. |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function in Structural Alignment |

|---|---|

| RCSB PDB Pairwise Structure Alignment Tool | Web-accessible interface to run multiple alignment algorithms (jFATCAT, CE, TM-align) without local installation [11] [14]. |

| TM-align Standalone Code | Downloadable C++ or Fortran source code for local, high-volume or integrated alignment pipelines [12]. |

| DaliLite | Standalone program for structural alignments based on the DALI method, useful for fold comparisons [10]. |

| PDBx/mmCIF File Format | Standard format for protein structure coordinate files, required by most modern alignment tools [11]. |

| Kabsch Algorithm | A method for calculating the optimal rotation matrix that minimizes the RMSD between two sets of points [9]. |

| Mol* Viewer | An interactive molecular visualization tool integrated into the RCSB PDB for viewing and analyzing alignment results [11]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the hybrid GADP-align algorithm, which tackles the NP-hard challenge by combining global search with local optimization.

Advanced Method: SAS-Pro Bilevel Optimization

For researchers requiring high-precision alignments, the SAS-Pro (Simultaneous Alignment and Superposition) model presents an advanced alternative. It formulates the alignment problem as a single bilevel optimization problem, thereby avoiding the suboptimal solutions that can arise from the traditional two-stage approach [15].

Traditional Two-Stage Approach:

- Stage 1 (Assignment): Use heuristics or DP to find residue correspondences based on a simplified scoring function.

- Stage 2 (Superposition): Use the Kabsch algorithm to find the optimal rotation-translation for the current assignment.

- These stages are repeated iteratively, but the decoupling means the final alignment is not guaranteed to be globally optimal [15].

SAS-Pro Bilevel Formulation:

- Master Problem: Optimizes the binary assignment variables (

x_ij). - Subproblem: For any given assignment, computes the optimal rotation-translation transformation (

T) by minimizing RMSD. - This model simultaneously addresses assignment and superposition, which can lead to alignments with better RMSD values and larger lengths than two-stage methods. It can also be extended to find non-sequential alignments by relaxing the sequentiality constraints [15].

- Master Problem: Optimizes the binary assignment variables (

Frequently Asked Questions

About Scoring Functions

Q1: What is the difference between a general-purpose and a family-specific amino acid similarity matrix?

General-purpose matrices, like BLOSUM or PAM, are derived by averaging substitution frequencies across many diverse protein families to represent the entire "protein universe." They are essential for tasks like database searches where a query sequence is aligned against millions of diverse sequences. In contrast, family-specific matrices are derived from the substitution patterns observed within a single protein family or structural fold. Using a family-specific matrix for sequences from that family can significantly improve alignment quality, as it utilizes substitution patterns that were averaged out in general-purpose matrices [16].

Q2: How do I choose the right substitution matrix for my protein sequences?

The choice depends on the relatedness of your sequences and the biological question. For general purposes or searching databases, BLOSUM62 is a robust default for proteins [17]. For closely related sequences, use matrices with higher numbers (e.g., BLOSUM80); for distantly related sequences, use lower numbers (e.g., BLOSUM45) [17]. If you are working with a specific, well-characterized protein family, a family-specific matrix, if available, will likely yield the most accurate alignments [16]. The VTML series are also high-quality general-purpose matrices [16].

About Gap Penalties

Q3: What are the main types of gap penalties, and when should I use them?

The three primary types of gap penalties are:

- Linear: A fixed cost per gap unit. It is computationally simple but less biologically realistic [18].

- Affine: The most widely used type, it consists of a gap opening penalty and a (smaller) gap extension penalty. This model reflects the biological observation that initiating an insertion or deletion event is less likely than extending an existing one [17] [18].

- Convex: A non-linear penalty where the cost per unit decreases as the gap length increases. This can be more biologically realistic for long gaps but is computationally complex [17] [18]. For most applications, the affine gap penalty is recommended due to its balance of biological realism and computational efficiency [17].

Q4: How do I set the values for gap opening and gap extension penalties?

There is no universal set of values, but common practices exist. The gap opening penalty is typically set higher than the extension penalty, with ratios often ranging from 10:1 to 20:1 [18]. Empirical determination using benchmark datasets with known correct alignments (like BAliBASE) is considered a robust method [18]. The table below summarizes typical values and determination methods.

| Consideration | Typical Values / Methods |

|---|---|

| Protein vs. DNA | Protein sequences generally use higher gap penalties than DNA [18]. |

| Protein Example | Gap opening: -10 to -15; Gap extension: -0.5 to -2 [18]. |

| DNA Example | Gap opening: -15 to -20; Gap extension: -1 to -2 [18]. |

| Empirical Determination | Use benchmark datasets (e.g., BAliBASE, PREFAB) and parameter sweeping [18]. |

About the Optimization Model

Q5: Why is dynamic programming considered "robust" in the context of structural alignment?

Dynamic programming (DP) finds an optimal alignment by solving a series of smaller sub-problems. The solution at each cell in the DP matrix is selected from a few possibilities (e.g., match/mismatch or indel). Research on the EIGAs structural alignment algorithm has shown that the optimal path through this matrix often remains unchanged over a substantial range of parameter values (like gap penalty) and similarity scores. This means that minor perturbations in the input parameters or structural similarity measures do not necessarily alter the final alignment, making the DP approach inherently stable and robust for many practical applications [6].

Q6: What is the difference between global, local, and semi-global alignment?

- Global Alignment: Forces the alignment to span the entire length of all sequences. It is best suited for sequences of similar length and high similarity. The Needleman-Wunsch algorithm is used for this [19] [1].

- Local Alignment: Identifies regions of high similarity within longer sequences. It is useful for finding conserved domains in otherwise divergent sequences. The Smith-Waterman algorithm is used for this [19].

- Semi-Global Alignment: A hybrid used when one wishes to align a sequence fully against a part of a much longer sequence (e.g., a gene against a chromosome) without penalizing gaps at the ends of the shorter sequence [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Alignment Quality or Biologically Implausible Gaps

Potential Cause 1: Incorrect gap penalty parameters.

- Symptoms: Alignments with too many short gaps (over-gapping) or too few gaps, forcing mismatches.

- Solution:

- Adjust the ratio: If you see many fragmented short gaps, your gap extension penalty may be too low relative to the opening penalty. Try increasing the extension penalty.

- Benchmark: Use a set of sequences with a known reference alignment (from structural data, e.g., SABmark [16]) and perform a parameter sweep. Systematically vary the gap opening and extension penalties and select the pair that produces alignments with the highest percentage of correctly aligned positions against the reference [18].

- Consider context: If available, use position-specific gap penalties. Tools like MAFFT and PSI-BLAST can apply lower gap penalties in variable loop regions and higher penalties in conserved core secondary structures [18].

Potential Cause 2: A suboptimal substitution matrix.

- Symptoms: Low overall alignment score, failure to align known conserved motifs.

- Solution:

- Switch matrices: If you are using a general-purpose matrix like BLOSUM62, try BLOSUM45 for distantly related sequences or BLOSUM80 for close relatives [17].

- Use a family-specific matrix: If your proteins belong to a well-studied family, check if a family-specific matrix has been published. Studies show these can significantly improve alignment accuracy [16].

Problem: Algorithm is Too Slow for Large-Scale Analysis

Potential Cause: The O(mn) time/space complexity of full dynamic programming is prohibitive for many long sequences.

- Solution: Utilize heuristic strategies that leverage faster algorithms.

- Divide and Conquer: Use tools like MUMmer or Minimap2 that find exact matches ("anchors") between sequences first. These anchors segment the dynamic programming matrix, drastically reducing the search space and computation time [20].

- Bounded Dynamic Programming: For highly similar sequences, use algorithms that restrict the dynamic programming calculation to a narrow "strip" around the matrix diagonal. This assumes the optimal path will not deviate far from the diagonal [20].

- Profile-Based Alignment: For multiple sequence alignment, build a profile from a smaller subset of sequences and then align remaining sequences to the profile, which is computationally more efficient than all-vs-all pairwise alignment [18].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating a New Scoring Function

This protocol can be used to benchmark a new scoring function (e.g., a novel substitution matrix or set of gap penalties) against existing standards.

1. Acquire a Benchmark Dataset:

- Obtain a standardized set of reference alignments, such as those from SABmark [16]. This database provides pairs and groups of sequences with reference alignments based on structural superpositions, which are considered a "gold standard." It is divided into superfamily (homologous) and twilight zone (analogous) subsets.

2. Generate Test Alignments:

- Using your new scoring function and a standard dynamic programming algorithm (e.g., Needleman-Wunsch for global alignment), perform pairwise alignments for all sequence pairs in the benchmark dataset.

3. Quantify Alignment Accuracy:

- Compare each test alignment to its corresponding reference structural alignment.

- Calculate the percentage of correctly aligned positions. A standard metric is the number of aligned residue pairs in the test alignment that are also aligned in the reference alignment.

4. Statistical Analysis:

- Compute the average accuracy across all alignments in the dataset for your new function.

- Perform a statistical test (e.g., a paired t-test) to determine if the difference in performance between your new function and an established standard (e.g., using BLOSUM62 with affine gap penalties) is statistically significant [16].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for optimizing a dynamic programming-based alignment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources used in the field of protein structural alignment.

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function / Application | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SABmark | Benchmark Dataset | A "gold standard" set of reference sequence alignments based on structural superposition; used for evaluating alignment algorithm performance. | [16] |

| BLOSUM Matrices | Substitution Matrix | A family of general-purpose amino acid similarity matrices. Higher numbers (e.g., BLOSUM80) for close, lower (e.g., BLOSUM45) for distant relationships. | [17] [16] |

| VTML Matrices | Substitution Matrix | Another series of high-quality, general-purpose amino acid substitution matrices. | [16] |

| Family-Specific Matrices | Substitution Matrix | Custom similarity matrices derived from the substitution patterns of a single protein family, which can improve alignment accuracy. | [16] |

| Affine Gap Penalty | Scoring Parameter | A two-part penalty consisting of a gap opening and a gap extension cost, reflecting the biological reality of indels. | [17] [18] |

| SAT (Sequence Alignment Teacher) | Educational Software | An interactive Java tool to visualize the dynamic programming matrix and understand the effect of parameter changes. | [21] |

| MUSTANG, TM-align, CE | Alignment Algorithms | Classical structural alignment algorithms used for benchmarking and obtaining reference structural alignments. | [22] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Parametric Sensitivity in DP-Based Alignment

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face regarding the sensitivity of Dynamic Programming (DP) parameters in protein structural alignment.

FAQ 1: How sensitive is my structural alignment to the choice of gap penalty?

Issue: The optimal alignment produced by a DP algorithm can appear to change significantly with small adjustments to the gap penalty parameters, leading to uncertainty in results.

Explanation: The sensitivity to gap penalties is often problem-dependent. Research on the EIGAs algorithm demonstrates that DP solutions can be remarkably stable over a substantial range of parametric values [6]. The underlying reason is that the DP recursion selects optimal values from a few possibilities; these values can adjust over nearby numbers without necessarily altering the final optimal solution [6].

Solution:

- Conduct a Parametric Sweep: Systematically vary the gap open (

ρ_o) and gap extension (ρ_c) penalties over a reasonable range and observe the resulting alignments. - Identify the Stability Range: As demonstrated in foundational DP examples, a unique solution may remain optimal over a broad range of penalty values (e.g.,

0.15 < ρ < ∞in a model case) [6]. Focus on parameter ranges where your core alignment is conserved. - Use Robustness as a Metric: Calculate the robustness score for individual aligned residues (edges). This score measures the fraction of near-optimal alignments in which a particular residue match appears. Edges with high robustness are more likely to be structurally correct and less sensitive to parameter changes [23].

Experimental Protocol for Parametric Stability Assessment:

- Input: Your target protein structures (P, Q).

- Parameters: Define a matrix of gap open (

ρ_o) and gap extension (ρ_c) penalties. - Procedure: For each parameter combination, compute the optimal sequence alignment using the DP algorithm.

- Analysis: Compare alignments using the stability of the core structural alignment and the robustness scores of aligned residues.

- Output: A report identifying the range of parameters that produce a stable, high-confidence alignment core.

FAQ 2: How can I account for uncertainty in atomic coordinates (e.g., from B-factors) in my structural alignment?

Issue: Experimental protein structures have inherent uncertainty in the precise 3D coordinates of their atoms, which is often quantified by B-factors. A rigid alignment algorithm might be overly sensitive to these small perturbations.

Explanation: Modern fast algorithms, such as EIGAs, have been shown to be robust against this type of structural uncertainty. Efficacy in identifying structurally similar proteins is maintained even when the coordinates of Cα atoms are perturbed randomly within probability distributions scaled by their B-factors [6].

Solution:

- Incorporate Uncertainty Explicitly: Model the atomic coordinates as probability distributions instead of fixed points. The standard deviation of these distributions can be derived from experimental B-factors [6].

- Utilize Robust Algorithms: Leverage modern DP-based algorithms designed for such robustness. Their underlying optimization model can tolerate small variations within appropriate tolerances without significant degradation in alignment quality.

- Validate with Multiple Samples: Generate multiple perturbed versions of your input structure (within the uncertainty bounds) and run alignments. A robust result will show a consistent alignment core across most samples.

FAQ 3: My sequence alignment is optimal, but it poorly matches the "true" structural alignment. Why?

Issue: An alignment that is optimal in terms of sequence score may differ from the alignment based on 3D structural superposition, which is often considered a gold standard.

Explanation: This is a known challenge. Structurally accurate alignments often have sub-optimal sequence alignment scores [23]. The "optimal" sequence alignment is tied to a specific scoring matrix and gap penalty set, which may not perfectly capture the evolutionary and physical constraints that preserve 3D structure.

Solution:

- Explore Near-Optimal Alignments: Do not rely solely on the single optimal alignment. Generate a set of near-optimal alignments (those with scores close to the best). The pool of these alignments has been shown to substantially overlap with structure-based alignments [23].

- Use a Probabilistic Model: Employ methods like the probA program that generate a set of probabilistic alignments. This ensemble can more effectively sample the alignment space and often includes alignments closer to the structural truth [23].

- Build a Predictive Model: Develop a logistic regression model that uses features from near-optimal alignments—such as robustness, edge frequency, and maximum bits-per-position—to classify which aligned residues are likely to appear in a structural alignment [23].

Quantitative Data on DP Robustness

Table 1: Features for Predicting Structurally Accurate Alignments from Near-Optimal Pools [23]

| Feature | Description | Utility in Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Robustness | The fraction of near-optimal alignments in which a specific residue pair (edge) appears. | High robustness strongly predicts that an edge is correct and structurally conserved. |

| Edge Frequency | How often an edge appears across the entire ensemble of alternative alignments. | Correlates with structural accuracy; correct edges tend to persist. |

| Maximum Bits-per-Position | A measure of the local conservation and information content at a position. | Identifies functionally or structurally critical residues that are likely to be aligned correctly. |

Table 2: Performance of Robustness in Classifying Structural Alignment Edges [23]

| Sequence Similarity Tier | Average % Identity | Performance of Robustness Classifier |

|---|---|---|

| High (E() < 10⁻¹⁰) | ~48% | Excellent accuracy in identifying structurally correct edges. |

| Medium (10⁻¹⁰ < E() < 10⁻⁵) | ~26.9% | Good performance, but benefits from additional features. |

| Low (E() ~ 10⁻⁵) | ~22.6% | Remains a useful predictor, though alignment ambiguity increases. |

Workflow Visualization: Assessing Parametric Robustness

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for evaluating the robustness of your DP alignment against parametric variation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Metrics for Robust Structural Alignment Research

| Tool / Metric | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| EIGAs Algorithm | DP-based Alignment Algorithm | A specific algorithm noted for its demonstrated robustness against both parametric and structural variation [6]. |

| Zuker Algorithm | Near-Optimal Alignment Generator | Produces a set of suboptimal alignments for a given sequence pair, used to calculate robustness scores [23]. |

| probA Program | Probabilistic Alignment Tool | Generates an ensemble of alignments based on statistical weighting, useful for sampling a wider variety of structurally accurate solutions [23]. |

| TM-score | Structural Similarity Metric | A scale for measuring the topological similarity of protein structures, often used as a benchmark for evaluating sequence alignments [24]. |

| RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) | Structural Distance Metric | Measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed proteins. The LCP problem aims to find the largest subset with RMSD below a threshold [25]. |

| Robustness Score | Alignment Confidence Metric | Quantifies the reliability of an individual aligned residue pair by its persistence in near-optimal alignments [23]. |

Beyond the Basics: Advanced DP Methods and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

What is the core principle behind the SARST2 filter-and-refine strategy? SARST2 employs a two-stage methodology to balance search speed with alignment accuracy. The filter stage rapidly reduces the search space by integrating primary, secondary, and tertiary structural features with evolutionary statistics to create a simplified representation of protein structures. The refine stage then performs detailed, accurate alignments on the promising candidate structures identified by the filter, using a weighted contact number-based scoring scheme and a variable gap penalty based on substitution entropy [26].

How does SARST2 relate to Dynamic Programming (DP) in structural alignment? While SARST2 itself uses fast linear encoding for its initial filter, its philosophy is aligned with a central theme in structural bioinformatics: using efficient methods to enable the application of more computationally intensive, accurate algorithms like DP. Many efficient structural alignment algorithms have a single application of dynamic programming at their core [6]. SARST2’s filter-and-refine approach makes large-scale studies feasible, allowing for subsequent deeper analysis with DP-based methods, which are known for finding optimal alignments but can be slow for database-wide comparisons [26] [6].

What performance advantage does SARST2 offer over other methods? In large-scale benchmarks, SARST2 has demonstrated superior performance by completing searches of the AlphaFold Database significantly faster and with substantially less memory usage than both BLAST and Foldseek, all while achieving state-of-the-art accuracy [26].

Implementation and Troubleshooting

FAQs: Common Setup and Execution Issues

Q1: I am getting compilation errors for the SARST2 source code. What are the prerequisites? SARST2 is implemented in Golang and is available as a standalone program. To avoid compilation issues, you can download the pre-built standalone programs directly from the official website (https://10lab.ceb.nycu.edu.tw/sarst2) or the GitHub repository (https://github.com/NYCU-10lab/sarst2) [26]. Ensure your system meets the basic requirements to run these executables.

Q2: How can I perform a massive database search on a standard personal computer? SARST2 is specifically designed for this scenario. Its high resource efficiency enables massive database searches using ordinary personal computers. The algorithm’s design, which includes a diagonal shortcut for word-matching and a machine learning-enhanced filter, minimizes both CPU time and memory footprint, making large-scale structural genomics projects more accessible [26].

Q3: The search results seem inaccurate for certain structural classes. How can I improve this? The accuracy of linear encoding methods like SARST2 can vary across different protein structural classes (e.g., all-alpha, all-beta, alpha/beta). The original SARST method was evaluated on these different classes. If you encounter issues, consult the benchmark studies in the SARST2 publication to understand its performance limitations for your specific protein class of interest [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Performance and Accuracy

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High False Positive Rate | Filtering stage threshold is set too low, allowing too many non-homologous structures to pass. | Adjust the filtering threshold to a more stringent value. Review the expectation values (E-values) provided in the results to assess reliability [27]. |

| High False Negative Rate | Filter is too aggressive, discarding true homologs. Evolutionary statistics may not be capturing remote homology. | Lower the filtering threshold. Ensure the integrated evolutionary statistics are computed from a diverse and representative multiple sequence alignment [26]. |

| Long Search Times | Database size is very large, and the filter is not pruning candidates efficiently. | The diagonal shortcut for word-matching is designed to speed up this process. Verify you are using the latest version of SARST2, as it includes optimizations for speed [26]. |

| Low Alignment Accuracy | The refinement stage may be using suboptimal parameters for your specific dataset. | Tune the parameters of the weighted contact number-based scoring scheme and the variable gap penalty, which depends on substitution entropy [26]. |

Performance Optimization and Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics of SARST2

The following table summarizes the key quantitative performance data for SARST2 as reported in large-scale benchmarks.

| Metric | SARST2 Performance | Comparative Method (BLAST) | Comparative Method (Foldseek) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Speed | Significantly faster | Slower | Slower |

| Memory Usage | Substantially less | Higher | Higher |

| Accuracy | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods | Lower | Lower |

| Scalability | Enables massive DB searches on ordinary PCs | Less efficient for large DB | Less efficient for large DB |

| E-value | Provides statistically meaningful expectation values | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

Workflow Diagram: SARST2 Filter-and-Refine Strategy

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow and data flow of the SARST2 algorithm.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for research in protein structural alignment, particularly in the context of methods like SARST2.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SARST2 | Standalone Program | High-throughput, resource-efficient protein structure alignment against massive databases [26]. |

| TM-align | Algorithm & Server | Sequence-independent protein structure alignment based on TM-score, using heuristic dynamic programming iterations [12]. |

| US-align | Algorithm & Server | Universal structure alignment for proteins, RNAs, and DNAs; extended from TM-align [28]. |

| RCSB PDB Alignment Tool | Web Server | Provides a unified interface for multiple pairwise structural alignment algorithms (jFATCAT, CE, TM-align) [14] [11]. |

| AlphaFold Database | Database | Source of predicted protein structures for use as input or as a search target in database scans [26] [11]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Benchmarking SARST2 Performance

This protocol outlines the methodology for replicating large-scale benchmark tests of SARST2, as cited in the search results [26].

Objective: To evaluate the accuracy, speed, and memory efficiency of SARST2 against state-of-the-art methods like BLAST and Foldseek in a database search scenario.

Materials and Software:

- SARST2: Download the standalone program from https://10lab.ceb.nycu.edu.tw/sarst2 or https://github.com/NYCU-10lab/sarst2 [26].

- Comparison Tools: Install BLAST and Foldseek for comparative analysis.

- Hardware: An ordinary personal computer is sufficient for SARST2.

- Query Set: A curated set of protein structures with known folds.

- Target Database: The AlphaFold Database or a similar large-scale structural database.

Procedure:

- Preparation:

- Format the target database for use with each tool (SARST2, BLAST, Foldseek).

- Prepare a set of query protein structures.

Execution:

- Run SARST2 to search each query against the target database. Record the time-to-completion and peak memory usage.

- Repeat the search process using BLAST and Foldseek with their default parameters, recording the same performance metrics.

Accuracy Assessment:

- For each tool, collect the hit list and alignment scores for each query.

- Use a ground-truth classification (e.g., from SCOP or CATH) to determine true and false positives.

- Calculate standard metrics such as sensitivity and precision to quantify accuracy.

Data Analysis:

- Compare the search speed (queries per second) and memory usage (peak RAM) of SARST2 against the other methods.

- Plot ROC curves or precision-recall curves to visually compare the alignment accuracy.

Troubleshooting Diagram: Alignment Inaccuracy

For diagnosing issues with alignment results, follow the logical process below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of combining a Genetic Algorithm (GA) with Iterative Dynamic Programming (DP) in GADP-align?

The primary advantage is that this hybrid approach helps in exploring the global alignment space and prevents the algorithm from getting trapped in local optimal solutions. The genetic algorithm performs a broad, heuristic search for correspondence between secondary structure elements, while the iterative dynamic programming technique refines this alignment. This combination avoids the limitations of methods that rely solely on an initial guess for corresponding residues, which can lead to suboptimal alignments, especially when sequence identity is low or secondary structure elements have different sizes [29].

Q2: My alignment results have a low TM-score. What parameters should I investigate adjusting first?

A low TM-score indicates poor structural similarity. You should first investigate the genetic algorithm parameters that control the search space and convergence. Key parameters to adjust are listed in the table below [29]:

| Parameter | Description | Default Value | Adjustment for Low TM-score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size (N) | Number of chromosomes in each generation. | 100 | Consider increasing to enhance genetic diversity. |

| Crossover Probability (Pc) | Likelihood that two chromosomes will exchange genetic material. | 0.75 | Slightly increasing may help, but avoid values too high. |

| Mutation Probability (Pm) | Likelihood of a random change in a chromosome. | 0.04 | Try a small increase to help escape local optima. |

| Shift Probability (Ps) | Likelihood of shifting SSE matching left or right. | 0.45 | This is a key operator; ensure it is not set too low. |

Q3: How does GADP-align handle initial matching, and why might this fail on proteins with few secondary structure elements?

GADP-align first creates an initial map of correspondence between Secondary Structure Elements (SSEs) — α-helices and β-strands — of the two proteins. It encodes the SSEs as a sequence (e.g., 'H' for helix, 'S' for strand) and uses the Needleman-Wunsch global sequence alignment algorithm to find the best match. Coils and loops are ignored in this initial stage [29]. This method might fail if the proteins have very few or no defined SSEs, as the initial match would have little information to guide the subsequent residue-level alignment. In such cases, the algorithm would rely heavily on the genetic operators (mutation, shift) to discover a good alignment from a poor starting point.

Q4: What is the function of the "Shift Operator" in the Genetic Algorithm, and when is it most critical?

The Shift Operator is a specialized genetic operator in GADP-align that generates a new matching between the SSE sequences by shifting them left or right relative to each other. Its primary function is to prevent the algorithm from converging on a local optimal matching and to help it explore the global optimal matching instead. It is most critical when the initial alignment from the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm on SSEs is incorrect or suboptimal, allowing the algorithm to correct the frame of the alignment [29].

Q5: Can GADP-align be used for multiple sequence alignment, or is it strictly for pairwise comparison?

The GADP-align algorithm, as described in the available research, is designed for pairwise protein structure alignment. The search results do not indicate an extension for multiple sequence alignment. Another study in the search results mentions a procedure for multiple alignments by first performing all pairwise alignments to find a "median" structure and then aligning everything to it [30], but this is a separate method and not part of GADP-align.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Algorithm Convergence Problems

Problem: The algorithm converges too quickly to a suboptimal solution (premature convergence) or fails to converge after a reasonable number of generations.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Mutation rate is too low. | Increase the mutation probability (Pm) to introduce more diversity into the population. |

| Selection pressure is too high. | Review your tournament selection size (k). A very high k means only the very best individuals are selected, reducing diversity. |

| Shift probability is too low. | The shift operator (Ps) is crucial for global exploration. Ensure it is not set to a very low value. |

| Population size is too small. | A small population lacks genetic diversity. Increase the population size (N) to give the algorithm more material to work with. |

Issue 2: Inaccurate Alignment in Specific Regions

Problem: The final alignment is generally good but shows significant errors in regions like loops or coils.

Explanation: GADP-align's initial matching is based solely on Secondary Structure Elements (SSEs), and coils/loops are explicitly ignored in this phase. The alignment in these regions is determined later during the residue-level alignment. Inaccuracies here are common because these regions are inherently more flexible and variable.

Solution:

- Post-processing: Consider using the output of GADP-align as an initial alignment for a more refined, local alignment tool that is sensitive to flexible regions.

- Fitness Function: The TM-score fitness function is a global measure. While it is effective, it may not prioritize local errors. Visually inspect the alignment in molecular visualization software to determine if the local inaccuracy is critical for your analysis.

Issue 3: Poor Handling of Proteins with Low Secondary Structure

Problem: The alignment performance degrades for proteins that are largely composed of coils or loops.

Explanation: This is a fundamental limitation of the GADP-align approach, as its heuristic search is guided by the initial SSE matching. Without a sufficient number of SSEs, the algorithm lacks a strong directional cue.

Solution:

- Alternative Methods: For proteins with very low secondary structure content, consider using alignment methods that do not rely heavily on SSEs for initial guidance. Tools like TM-align [12] or others that use different heuristics (e.g., gapless threading, fragment matching) might be more robust in these specific cases.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the GADP-align algorithm:

Detailed Protocol: Running a GADP-align Experiment

Objective: To obtain an accurate pairwise structural alignment of two protein structures using the GADP-align hybrid method.

Inputs:

- Two protein structures in PDB format.

Procedure:

- Preprocessing:

- Extract the secondary structure assignment for each protein from the PDB files or calculate it using a tool like DSSP.

- Encode the secondary structure elements into a sequence of 'H' (α-helix) and 'S' (β-strand). Ignore coils and loops.

Initial SSE Matching:

- Align the two SSE sequences using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm.

- Use a scoring system: +2 for identical SSEs, -1 for non-identical SSEs, and a gap-opening penalty of -2.

- This produces the initial correspondence map between SSEs.

Genetic Algorithm Setup:

- Initial Population: Generate an initial population of 100 chromosomes. Each chromosome represents the initial SSE matching. For each pair of matched SSEs in a chromosome, randomly select an initial list of corresponding residues (between 20% and 100% of the shorter SSE's length).

- Fitness Evaluation: For each chromosome, calculate its fitness using the TM-score function. The formula used is:

TM-score = max [ Σ<sub>i</sub> 1 / (1 + (d<sub>i</sub>/d<sub>0</sub>)²) ] / L<sub>Target</sub>whereL<sub>Target</sub>is the length of the shorter protein,L<sub>ali</sub>is the number of aligned residues,d<sub>i</sub>is the distance between the i-th pair of aligned residues, andd<sub>0</sub>(L<sub>Target</sub>) = 1.24 * ∛(L<sub>Target</sub> - 15) - 1.8[29]. - Selection: Use tournament selection (with tournament size

k=3) to choose parents for the next generation. - Genetic Operators:

- Crossover: Perform a two-point crossover on selected parents with a probability

Pc=0.75. - Mutation: Randomly increase or decrease the number of aligned residues within a matched SSE pair with a probability

Pm=0.04. - Shift: Shift the SSEs left or right in the matching with a probability

Ps=0.45.

- Crossover: Perform a two-point crossover on selected parents with a probability

Iterative Dynamic Programming:

- For the high-fitness alignments proposed by the genetic algorithm, an iterative dynamic programming technique is applied to refine the residue-to-residue alignment.

Termination:

- The algorithm repeats steps 3-4 for a predefined number of generations or until the TM-score improvement falls below a threshold.

Output:

- The alignment with the highest TM-score is selected as the final result. This includes the list of equivalent residues and the optimal superposition of the two structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in a GADP-align experiment.

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Key Parameters / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Needleman-Wunsch Algorithm | To generate the initial global alignment of Secondary Structure Element (SSE) sequences. | Scoring: +2 (match), -1 (mismatch), -2 (gap penalty). Provides the initial heuristic [29]. |

| TM-score | A size-independent scoring function used as the fitness measure to evaluate the quality of structural alignments. | Values > 0.5 indicate generally the same fold; values < 0.2 suggest unrelated proteins [12]. |

| Tournament Selection | A selection method in the GA that chooses the fittest individual from a random subset of the population for reproduction. | Helps maintain selection pressure. Tournament size k=3 is used in GADP-align [29]. |

| Shift Operator | A specialized GA operator that shifts the correspondence of SSEs to explore different global matchings. | Critical for avoiding local optima. Probability Ps=0.45 [29]. |

| Iterative Dynamic Programming | A technique that refines the residue-level alignment based on the correspondence map provided by the GA. | Used to optimize the spatial superposition and final residue matching iteratively [29] [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My PSSM is not detecting divergent homologs effectively. What could be wrong? The sensitivity of a Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) is highly dependent on the quality and diversity of its seed alignment. If the seed alignment contains sequences that are too similar, the PSSM will not be informative enough for detecting remote homologs. The optimal diversity for a seed alignment is around 30–50% average pairwise identity [31]. Furthermore, the algorithm used to construct the seed alignment significantly impacts performance. For the most accurate detection of a core structural scaffold, consider using seed alignments based on structural similarity (e.g., from VAST) rather than sequence similarity alone, as this has been shown to produce superior results [31].

Q2: What are the primary limitations of using Dynamic Programming (DP) in my reinforcement learning model for protein alignment? While DP provides a strong theoretical foundation, it has key limitations for real-world biological applications:

- Model Dependency: DP algorithms assume a perfect and complete model of the environment, including known transition probabilities and reward functions. In protein research, these are often unknown or too complex to model accurately [32].

- Computational Complexity: The state and action spaces for protein structures are extremely large. DP methods can become computationally prohibitive and time-consuming, suffering from exponential growth in complexity with high-dimensional spaces [32].

Q3: I am working with membrane proteins. Which structural alignment method is most accurate? No single method is universally superior for membrane proteins. A consensus approach is recommended for higher reliability. Fragment-based methods, such as FR-TM-align, have been shown to be particularly useful for aligning membrane protein structures and are better suited for handling large conformational changes [33]. For robust results, combine alignments from multiple methods (e.g., FR-TM-align, DaliLite, MATT, and FATCAT) and use their agreement to assign confidence values to each position in the final alignment [33].

Q4: How can neural networks like DeepBLAST improve my structural alignments when I only have sequence data? Tools like DeepBLAST use neural networks to estimate structural similarity and generate alignments from sequence information alone. They are trained to predict structural alignments that are nearly identical to those produced by state-of-the-art structural alignment algorithms, providing a powerful method for remote homology search and alignment without requiring known 3D structures for all sequences in your analysis [34].

Q5: What does a significant PSSM E-value tell me in a fold recognition server like 3D-PSSM? In servers like 3D-PSSM, a significant E-value indicates that the match between your query sequence and a library template is statistically unlikely to have occurred by chance. This E-value is a composite score based on the compatibility of your sequence with the template's 3D structure, incorporating factors like 1D-PSSMs, 3D-PSSMs, secondary structure matching, and solvent accessibility propensities [35]. A lower E-value corresponds to a higher confidence in the proposed fold assignment.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Accuracy in PSSM-Sequence Alignments

Problem: The molecular models generated from your PSSM-sequence alignments have low contact specificity when compared to the known protein structures.

Investigation & Resolution:

Diagnose the Seed Alignment:

- Check the average pairwise identity of the sequences in your seed alignment. If it is above 50%, the PSSM may lack the diversity needed to recognize distant relatives [31].

- Examine the alignment method used. Global sequence aligners (e.g., ClustalW) can produce less accurate PSSM-sequence alignments compared to local or structure-based methods, especially for sequences with low identity [31].

Recommended Protocol for High-Accuracy PSSMs:

- Curate a diverse sequence set: Aim for a seed alignment with 30–50% average pairwise identity [31].

- Use a structure-based alignment algorithm: If 3D structures are available for some family members, construct the seed alignment using a structural alignment tool like VAST or a fragment-based method. Research shows this leads to PSSM-sequence alignments with contact specificity nearly as good as full structure-structure alignments [31] [33].

- Validate with contact specificity: Use a metric like contact specificity to quantitatively assess the accuracy of your predicted molecular models against known structures [31].

Issue: Neural Network Model Fails to Converge During PPI Network Alignment

Problem: Your deep learning model for protein-protein interaction (PPI) network alignment does not converge or produces poor results.

Investigation & Resolution:

Verify Input Features: The RENA (REcurrent neural network Alignment) method demonstrates that successful network alignment relies on combining multiple data types [36] [37]. Ensure your model's input features include:

- Sequence similarity: Incorporate BLAST scores or other sequence comparison metrics.

- Topological similarity: Calculate network-based features like the Page Rank score for nodes in both networks.

Reframe the Problem: The network alignment problem is NP-hard. The RENA approach successfully transforms it into a binary classification problem [37]. For each potential node pair (one from each network), the task is to classify the pair as "Align" or "NotAlign." This structured approach can significantly improve model performance.

Adopt a Proven Architecture: Implement a deep learning architecture that has been shown to work, such as a network with Embedding layers, Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) layers, and Fully Connected (Dense) layers with a softmax activator function for the final classification [37].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: PSSM-Sequence Alignment Accuracy by Seed Alignment Method

Table comparing the median contact specificity of molecular models derived from PSSMs built using different seed alignment algorithms, across varying levels of sequence diversity [31].

| Seed Alignment Algorithm | Alignment Type | >50% Avg Pairwise Identity | <50% Avg Pairwise Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAST | Local-Structure | ~80% | ~70% |

| BLAST | Local-Sequence | ~80% | Lower than VAST |

| ClustalW-pairwise | Global-Sequence | ~80% | Lower than BLAST |

| ClustalW | Global-Sequence | ~80% | Lowest |

Protocol: Constructing an Optimal PSSM for Remote Homology Detection

This protocol is designed to create a PSSM with high sensitivity and alignment accuracy for detecting divergent protein family members [31].

- Gather Sequences: Collect a diverse set of homologous protein sequences. Use tools like PSI-BLAST to find initial family members.

- Create Seed Alignment:

- Assess Diversity: Calculate the average pairwise identity within the seed alignment. If it is outside the 30-50% range, consider curating the sequence set to achieve better diversity [31].

- Build the PSSM: Use the refined seed alignment as input to a PSSM-construction program, such as the one implemented in PSI-BLAST.

- Iterate and Validate: Use the PSSM to search a sequence database. Statistically significant new hits can be added to the seed alignment to refine the PSSM in an iterative process.

Protocol: Deep Learning-Based PPI Network Alignment (RENA method)

This protocol outlines the steps for predicting node alignments between two PPI networks using a recurrent neural network [37].

- Preprocessing & Feature Extraction:

- Input: Two PPI networks,

N1 = (V1, E1)andN2 = (V2, E2). - Sequence Similarity: For every possible node pair (u, v) where u is in V1 and v is in V2, compute a BLAST score.

- Topological Similarity: For every node in both networks, calculate a Page Rank score. Compute other network topological features as required.

- Input: Two PPI networks,

- Dataset Creation:

- Form a dataset where each data point represents a potential node pair (u, v).

- The features for this pair are the extracted sequence and topological similarities.

- The label is "Align" if the nodes are considered equivalent (e.g., based on known orthology), otherwise "NotAlign."

- Model Training:

- Architecture: Construct a neural network with Embedding layers, RNN layers (e.g., LSTM or GRU), and Fully Connected layers.

- Output Layer: Use a softmax activator function for the binary classification ("Align"/"NotAlign").

- Train the model on the created dataset.

- Alignment Prediction:

- Feed the feature data for all potential node pairs into the trained model.

- The model outputs the predicted probability of alignment for each pair.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Machine Learning-Enhanced Protein Alignment

A table of key software tools and their primary functions in this field.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevant Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSI-BLAST | Algorithm / Server | Constructs PSSMs and performs iterative homology searches [31]. | Building and refining PSSMs from sequence data. |

| VAST | Algorithm | Performs 3D structure-structure alignment [31] [10]. | Creating high-quality seed alignments for PSSMs. |

| DALI / DaliLite | Algorithm / Server | Performs 3D structure alignment based on contact patterns [33] [10]. | Fold comparison and structure-based seed alignment. |

| FR-TM-align | Algorithm | Fragment-based structure alignment, robust for conformational changes [33]. | Aligning membrane proteins or structures with large shifts. |

| DeepBLAST | Algorithm / Software | Neural network for predicting structural alignments from sequence [34]. | Estimating structural similarity when only sequence data is available. |

| T-Coffee (Expresso) | Server | Multiple sequence aligner that can incorporate structural information [38]. | Creating accurate MSAs using 3D structure data. |

| 3D-PSSM | Server | Threading-based fold recognition using 3D profiles [35]. | Predicting 3D structure and function for a protein sequence. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Protein Structural Alignment Research Workflow

PSSM Quality Factors

Protein substructure alignment is a fundamental task in computational biology, essential for understanding protein function, evolution, and enabling structure-based drug design. Traditional methods have largely relied on dynamic programming (DP) approaches, which, while effective, face limitations in identifying local functional motifs embedded within different overall fold architectures [39]. PLASMA (Pluggable Local Alignment via Sinkhorn MAtrix) represents a paradigm shift, reformulating the alignment problem as a regularized optimal transport (OT) task [39]. This novel framework leverages differentiable Sinkhorn iterations to provide a learnable, efficient, and interpretable alternative to DP-based methods, capable of accurately aligning partial and variable-length substructures between proteins [39].

The following workflow illustrates PLASMA's core operational process:

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The table below details the essential computational components and their functions within the PLASMA framework:

| Component Name | Type/Function | Key Parameters & Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Residue Embeddings [39] | Input Features | d-dimensional vectors from pre-trained protein language models; encode structural/biochemical context |

| Siamese Network [39] | Cost Computation | Learns task-specific residue similarities; uses Layer Normalization (LN) |

| Sinkhorn Iterations [39] | Optimization Core | Entropy-regularized OT solver; produces soft alignment matrix; differentiable |

| Plan Assessor [39] | Similarity Scoring | Summarizes alignment matrix into interpretable κ score [0,1] |

| PLASMA-PF [39] | Parameter-Free Variant | Training-free alternative; maintains competitive performance without task-specific data |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does PLASMA fundamentally differ from traditional dynamic programming approaches for structural alignment?

PLASMA differs from DP-based methods in both its underlying mathematical framework and its output characteristics. While DP methods rely on recursive scoring and explicit gap penalties to find an optimal path [6], PLASMA reformulates alignment as an entropy-regularized optimal transport problem [39]. This key difference enables PLASMA to naturally handle partial and variable-length matches without requiring explicit fragment enumeration. Additionally, unlike traditional DP with fixed, position-independent gap penalties [6], PLASMA's cost matrix is learnable, allowing it to adapt to specific biological contexts through training. The output also differs significantly: whereas DP produces a single optimal alignment path, PLASMA generates a soft alignment matrix that captures probabilistic correspondences between all residue pairs, providing richer interpretability [39].

Q2: What are the computational complexity requirements of PLASMA, and how do they scale with protein size?

PLASMA achieves a computational complexity of O(N²) [39], where N represents the number of residues in the larger of the two proteins being aligned. This complexity stems primarily from the construction of the pairwise cost matrix and the Sinkhorn iterations. When compared to established methods, this places PLASMA in a favorable position for practical applications: it is approximately 4 times faster than CE and 20 times faster than DALI and SAL [40], making it suitable for large-scale structural comparisons, such as mining the AlphaFold Database (AFDB) for conserved functional motifs.

Q3: My PLASMA alignments appear noisy with weak biological relevance. How can I improve alignment quality?

Poor alignment quality typically stems from suboptimal residue embeddings or cost function miscalibration. Implement the following troubleshooting steps:

- Validate Embedding Quality: Ensure the pre-trained protein language model generating your residue embeddings was trained on diverse structural data. Domain-specific fine-tuning may be necessary for specialized applications.

- Inspect Cost Matrix: Visualize the learned cost matrix to verify it reflects meaningful biochemical or structural similarities. High costs should correspond to residue pairs with low compatibility.

- Adjust Regularization: The entropy regularization parameter (ε) in Sinkhorn iterations balances alignment precision and computational ease. Decrease ε for sharper, more deterministic alignments, but be aware this may increase numerical instability and require more iterations to converge.

- Utilize PLASMA-PF: If you lack high-quality training data, switch to the PLASMA-PF (parameter-free) variant, which provides a robust, training-free alternative that often performs comparably [39].

Q4: During training, the Sinkhorn iterations fail to converge. What could be causing this issue?

Divergence in Sinkhorn iterations often indicates numerical instability, frequently related to the regularization parameter or cost matrix values:

- Regularization Strength: Excessively weak regularization (ε too small) makes the OT problem closer to its original "hard" formulation, leading to numerical overflow. Increase ε to strengthen entropy regularization, which stabilizes the iterative process [39].

- Cost Matrix Scaling: Ensure your cost matrix values are within a reasonable numerical range. Experiment with normalizing or standardizing cost values before feeding them into the Sinkhorn loop.

- Iteration Limit: Implement a practical iteration limit (e.g., 100-1000 steps) with convergence monitoring based on the change in the alignment matrix between steps (e.g., L2-norm difference < 1e-6).

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Performing Residue-Level Substructure Alignment with PLASMA

This protocol details the steps to align a query protein against a candidate protein to identify conserved local motifs using PLASMA.

Inputs: Two protein structures (Query 𝒫q and Candidate 𝒫c) in PDB format.

Outputs: Soft alignment matrix Ω and interpretable similarity score κ.

Feature Extraction:

- Generate residue-level embeddings

𝑯q ∈ ℝ^(N×d)and𝑯c ∈ ℝ^(M×d)for the query and candidate proteins, respectively, using a pre-trained protein representation model (e.g., a protein language model). The dimensiondis defined by the chosen model [39].

- Generate residue-level embeddings

Cost Matrix Computation:

- Feed the embeddings through the Siamese network architecture to compute the learnable cost matrix

𝒞. - The cost between residue

iof the query and residuejof the candidate is calculated as:𝒞ij = ‖[ϕθ(LN(𝒉q,i)) - ϕθ(LN(𝒉c,j))]+‖1[39] whereϕθis a learnable network,LNdenotes Layer Normalization, and[·]+is the ReLU activation.

- Feed the embeddings through the Siamese network architecture to compute the learnable cost matrix

Optimal Transport Solution:

- Solve the entropy-regularized OT problem using differentiable Sinkhorn iterations.

- Initialize the Sinkhorn kernel:

K = exp(-𝒞/ε), whereεis the regularization parameter. - Iterate until convergence (or for a fixed number of steps):

- The resulting soft alignment matrix is:

Ω = diag(u) · K · diag(v).

Similarity Scoring:

- Pass the alignment matrix

Ωto the Plan Assessor module. - This module summarizes

Ωinto a single, interpretable similarity scoreκin the range [0,1], quantifying the overall quality of the substructure match [39].

- Pass the alignment matrix

Protocol: Large-Scale Database Screening with PLASMA-PF

This protocol uses the parameter-free PLASMA-PF variant for screening a query motif against a large structural database.

Inputs: Query substructure, Database of protein structures. Outputs: Ranked list of candidate proteins with similarity scores.

Preprocessing:

- Convert the entire structural database into residue-level embeddings offline to maximize efficiency.

Alignment:

- For each database protein, run the PLASMA-PF alignment against the query substructure.

- Since PLASMA-PF is training-free, it uses a fixed, biologically informed cost function instead of a learnable one [39].

Post-processing:

- Collect the similarity scores

κfor all query-database pairs. - Rank database proteins in descending order of their

κscores. - Apply a significance threshold (e.g.,

κ > 0.5) to filter low-quality matches and focus on biologically relevant hits.

- Collect the similarity scores