Evaluating Cathepsin B Inhibition Models: From Computational Screening to Therapeutic Applications in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases

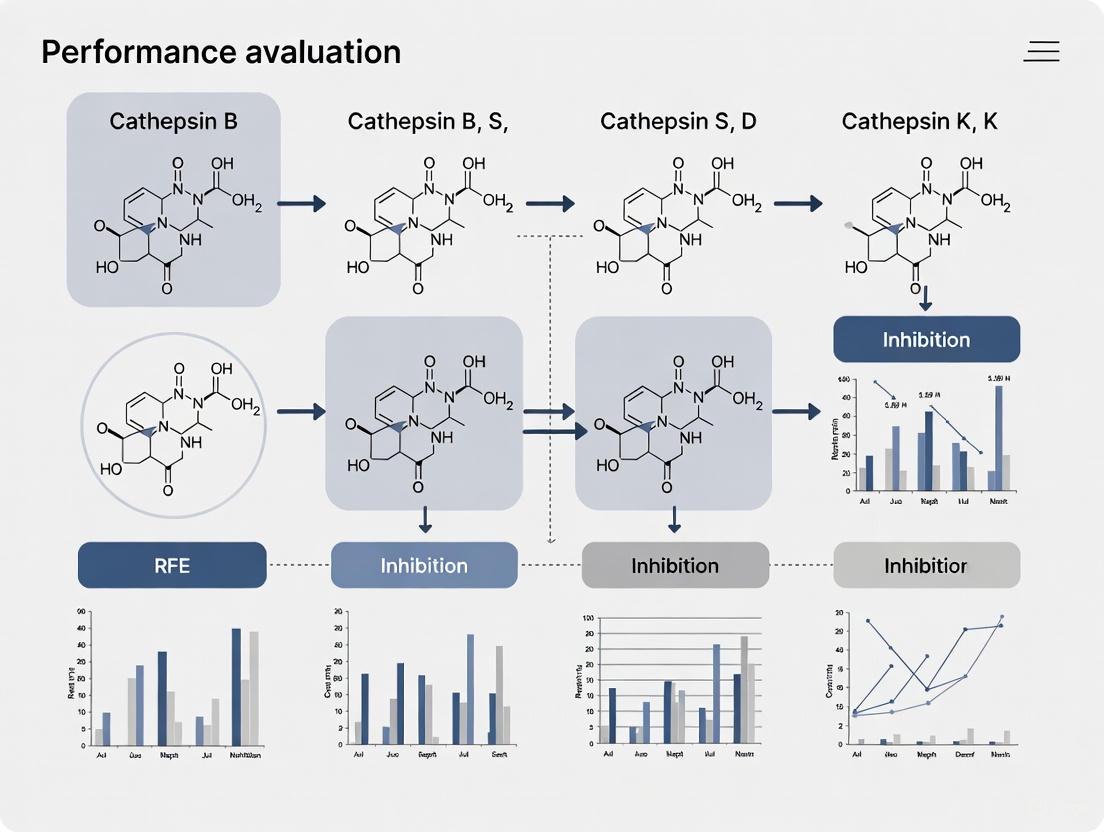

This comprehensive review systematically evaluates the performance of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) models in identifying and optimizing Cathepsin B inhibitors.

Evaluating Cathepsin B Inhibition Models: From Computational Screening to Therapeutic Applications in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Abstract

This comprehensive review systematically evaluates the performance of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) models in identifying and optimizing Cathepsin B inhibitors. Cathepsin B, a cysteine protease implicated in cancer progression, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease, represents a promising therapeutic target. This article explores foundational biological roles of Cathepsin B across pathological contexts, examines computational and experimental methodologies for inhibitor screening, addresses critical optimization challenges including selectivity and pH-dependent activity, and validates approaches through comparative analysis of emerging therapeutic candidates. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this work integrates structural biology, machine learning, and clinical translation to advance targeted inhibition strategies.

Cathepsin B as a Multifaceted Therapeutic Target: Biological Roles and Disease Implications

Cathepsin B (CTSB), a lysosomal cysteine protease of the papain family, is a key player in tumor progression. While it normally functions in intracellular protein turnover within the acidic lysosomal environment, its dysregulation in cancer contexts contributes significantly to malignant transformation. In various human cancers, CTSB undergoes overexpression, altered trafficking, and secretion into the extracellular space, where it facilitates critical tumor-promoting processes including extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, angiogenesis, and metastasis [1] [2]. This review synthesizes current mechanistic understanding of CTSB in cancer progression, compares its roles across different cancer models, and details the experimental approaches used to evaluate CTSB function and inhibition, providing a resource for therapeutic development.

Molecular Regulation and Trafficking of Cathepsin B in Cancer

Transcriptional and Post-transcriptional Regulation

The CTSB gene, located on chromosome 8p22, is regulated by multiple promoters rich in GC content but lacking TATA and CAAT boxes [1]. Key transcription factors including Ets1, Sp1, and Sp3 bind to these promoter regions and activate transcription [1]. Ets1, a proto-oncogene that enhances invasiveness, is frequently overexpressed in cancers such as breast cancer [1]. Upstream stimulatory factors (USFs) that bind to the E-box in the promoter can either increase or repress CTSB expression, providing a link to stress-responsive pathways [1]. Post-transcriptionally, alternative splicing generates variants like CB(-2) and CB(-2,3). The CB(-2) variant translates more efficiently, while CB(-2,3) produces a truncated protein that may be mislocalized to mitochondria and involved in cell death pathways [1].

Altered Trafficking and Localization

In normal physiology, CTSB is synthesized as a preproenzyme and traffics through the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus to lysosomes [1]. In cancer cells, this trafficking is disrupted, leading to CTSB secretion and association with the plasma membrane [1]. This redistribution is facilitated by binding to the annexin II heterotetramer, which localizes CTSB to caveolae, specialized membrane microdomains [1] [3]. This pericellular localization positions CTSB to degrade ECM components and activate proteolytic cascades critical for invasion.

The following diagram illustrates the key regulatory and trafficking pathways of Cathepsin B in a cancer cell:

Mechanisms of Action in Cancer Progression

Facilitation of Invasion and Metastasis

CTSB promotes invasion through direct degradation of ECM components and activation of other proteases [2]. As a cysteine protease with both endopeptidase and exopeptidase activities, CTSB can cleave various structural proteins in the basement membrane and interstitial matrix [1]. In colorectal cancer models, CTSB silencing reduced invasion capacity and metastatic spread in immunodeficient mice [4]. Furthermore, CTSB can process and activate other proteolytic enzymes, including urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), thereby amplifying the overall proteolytic cascade that enables cancer cell dissemination [1].

Regulation of Angiogenesis

CTSB modulates the angiogenic switch through multiple mechanisms. In endothelial cells, suppression of CTSB activity increased VEGF mRNA and protein levels, correlating with elevated HIF-1α, while also reducing the anti-angiogenic protein endostatin [5]. This suggests CTSB helps balance pro- and anti-angiogenic factors. Additionally, CTSB can inactivate tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs), specifically TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, thereby releasing their inhibition of MMPs and creating a pro-angiogenic environment [6]. This TIMP inactivation represents an indirect mechanism whereby CTSB promotes blood vessel formation to support tumor growth.

Role in Programmed Cell Death

CTSB localizes to the cytosol under pathological conditions due to lysosomal membrane permeabilization, where it participates in multiple programmed cell death (PCD) pathways [3]. In apoptosis, CTSB can cleave Bid to its active form (tBid), triggering mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation [3]. CTSB also contributes to pyroptosis by promoting NLRP3 inflammasome activation, though the specific substrates remain unclear [3]. The dual role of CTSB in both promoting and inhibiting cell death depending on cellular context adds complexity to its functions in tumor progression.

Experimental Models and Data Comparison

Research into CTSB function employs diverse experimental approaches, from in vitro enzyme assays to complex in vivo models. The table below summarizes key experimental findings and methodologies across different cancer models.

Table 1: Comparative Experimental Data on Cathepsin B in Cancer Models

| Cancer Type/Model | Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Molecular Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer [4] | CTSB silencing (RNAi) in human CRC cells; Xenograft models | Inhibited growth in soft agar; Reduced invasion and metastatic spread; Increased p27Kip1 levels | Lysosomal degradation of p27Kip1 cell cycle inhibitor |

| Glioma [1] | Transgenic models; Protease targeting studies | Single CTSB targeting less effective than multi-protease targeting | Part of proteolytic pathway with other proteases/receptors |

| Pancreatic & Mammary Carcinoma [1] | Transgenic murine models | Causal roles in initiation, growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis | Promotion of tumor cell proliferation; Involvement in tumor-associated macrophages |

| Endothelial Cells & Angiogenesis [5] | Tube formation assay in collagen; CTSB inhibition (CA-074-Me) | Eliminated dependence on exogenous VEGF; Increased HIF-1α and VEGF; Reduced endostatin | Regulation of intrinsic angiogenic threshold; Balance of pro/anti-angiogenic factors |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Tube Formation Assay for Angiogenesis Studies

The tube formation assay evaluates endothelial cell morphogenesis into capillary-like structures, simulating early stages of angiogenesis [5].

Materials:

- Collagen gel mixture: 80% VITROGEN, 0.02 N NaOH, 20 mM HEPES, 2 mg/ml NaHCO₃, 0.5 μg/ml fibronectin, 0.5 μg/ml laminin, and 10.5 mg/ml RPMI powder [5].

- Cells: Bovine Retinal Endothelial Cells (BRECs) or Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) [5].

- Inhibitors: Cathepsin B inhibitor (CA-074-Me) [5].

Methodology:

- Lower gel layer: Add 400 μL of collagen gel mixture per well to a 24-well plate. Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours for polymerization [5].

- Cell seeding: Seed 1 × 10⁵ BRECs or 7 × 10⁴ HUVECs per well in appropriate medium. Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C [5].

- Upper gel layer: Remove medium and add 150 μL of fresh collagen gel mixture on top of the cell layer [5].

- Treatment: Add test compounds (e.g., VEGF, CTSB inhibitors) in culture medium.

- Analysis: After incubation (typically 24-48 hours), quantify tube formation by measuring total tube length, number of branch points, or enclosed areas using microscopy and image analysis software [5].

RNA Interference and Xenograft Studies

Gene silencing followed by xenograft implantation assesses the role of CTSB in tumorigenesis and metastasis in vivo [4].

Materials:

- Cells: Human colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines (e.g., HCT116, HT-29) [4].

- Animals: Immunodeficient mice (e.g., CD1 nu/nu, SCID) [4].

- Reagents: CTSB-specific shRNA/siRNA, transfection reagent, Matrigel [4].

Methodology:

- CTSB knockdown: Transfect CRC cells with CTSB-specific RNAi constructs using standard protocols (e.g., lipofection) [4].

- Validation: Confirm knockdown efficiency via Western blotting or qPCR [4].

- Xenograft establishment: Subcutaneously inject control and CTSB-deficient cells (e.g., 5 × 10⁶ cells in Matrigel) into flanks of mice [4].

- Metastasis models: For spontaneous metastasis, use orthotopic implantation; for experimental metastasis, use intravenous injection [4].

- Monitoring: Measure primary tumor volume weekly with calipers. For metastasis, image organs (e.g., lungs, liver) ex vivo after sacrifice and count metastatic nodules [4].

- Tissue analysis: Process tumors for immunohistochemistry (IHC) or Western blotting to analyze proliferation markers (e.g., Ki-67), apoptosis (e.g., cleaved caspase-3), and pathway components (e.g., p27Kip1) [4].

Cathepsin B Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy

Inhibiting CTSB has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach. The diagram below illustrates the mechanistic strategy for selective CTSB inhibition in the pathogenic cytosolic environment, a novel approach for conditions like traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer's disease that may also inform cancer therapeutic development [7].

The pH-dependent inhibitor strategy leverages the different microenvironments where CTSB operates. Under normal conditions, CTSB functions in acidic lysosomes (pH ~4.6). In pathology, lysosomal leakage releases CTSB into the neutral cytosol (pH ~7.2) [7] [3]. Inhibitors like Z-Arg-Lys-AOMK are designed to be selective for the neutral pH form of CTSB, potentially targeting the disease-associated pool of the enzyme while sparing its normal physiological function [7]. In cancer, the extracellular tumor microenvironment can also be slightly acidic, which may influence the efficacy of such pH-sensitive agents.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cathepsin B Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function / Mechanism | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CA-074 / CA-074Me [5] [4] | Selective, potent cathepsin B inhibitor (CA-074Me is cell-permeable prodrug) | Inhibiting extracellular vs. intracellular CTSB; Studying CTSB loss-of-function in vitro and in vivo |

| E64d [7] | Broad-spectrum cysteine protease inhibitor (prodrug of E64c) | General cysteine protease inhibition; Assessing overall class contribution to pathology |

| Z-Arg-Lys-AOMK [7] | Neutral pH-selective cathepsin B inhibitor | Selective targeting of cytosolic (pathogenic) CTSB without affecting lysosomal CTSB |

| CTSB-specific siRNA/shRNA [4] | RNA interference for targeted gene knockdown | Establishing stable CTSB-deficient cell lines; Determining long-term functional consequences |

| Anti-Cathepsin B Antibodies [4] | Detection of CTSB protein levels and localization | Immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, immunofluorescence for expression analysis |

| Activity-Based Probes [1] | Covalently bind active enzyme forms, enabling detection | Labeling active CTSB on tumor cell surfaces; Identifying compensatory proteases |

Cathepsin B emerges as a multifunctional protease that significantly contributes to cancer progression through diverse mechanisms, including direct ECM degradation, regulation of angiogenesis, modulation of cell death pathways, and control of cell cycle progression. Its value as a therapeutic target is supported by evidence from genetic knockout and pharmacological inhibition studies across multiple cancer models. The development of sophisticated tools, such as pH-selective inhibitors and activity-based probes, continues to refine our understanding of CTSB's pathophysiological roles and promises to enable more targeted therapeutic interventions. Future research should focus on clarifying context-specific functions of CTSB in different cancer types and stages, and exploring combination therapies that simultaneously target CTSB and complementary proteolytic pathways.

The intricate interplay between protein aggregation pathways represents a central frontier in neurodegenerative disease research. Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), the two most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders, are characterized by the accumulation of specific pathological proteins—amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau in AD, and α-synuclein (α-syn) in PD [8] [9]. Emerging evidence reveals that these proteins operate within a connected pathological network, where cross-talk between Aβ and α-syn accelerates cognitive decline and disease progression [8] [9]. Within this complex protein interplay, lysosomal proteases—particularly cathepsins—have emerged as critical regulators of both Aβ processing and α-syn clearance mechanisms.

This review examines the dual role of cathepsin B as a nexus between AD and PD pathophysiology, focusing on its dual functions in amyloid-beta processing and alpha-synuclein clearance. We synthesize current experimental evidence to evaluate cathepsin B's potential as a therapeutic target, providing researchers with structured experimental data, methodological approaches, and analytical frameworks for investigating lysosomal pathways in neurodegenerative proteinopathies.

Cathepsin B at the Crossroads of Neurodegenerative Pathways

Cathepsin B is a lysosomal cysteine protease belonging to the papain family, normally localized to the lysosomal lumen where it maintains cellular homeostasis through protein degradation [10] [11]. Beyond its classical lysosomal functions, cathepsin B operates extracellularly under pathological conditions and participates in multiple signaling pathways relevant to neurodegeneration [11]. Genetic studies have identified variants in the CTSB gene encoding cathepsin B that are associated with increased PD risk, particularly through mechanisms that reduce enzyme expression or function [10].

The enzyme demonstrates a complex, context-dependent relationship with neurodegenerative processes. Cathepsin B can cleave both monomeric and fibrillar forms of α-syn, and its inhibition impairs autophagy, reduces glucocerebrosidase activity, and leads to accumulation of lysosomal content [10]. Simultaneously, cathepsin B interacts with Aβ metabolism, though these relationships remain less fully characterized than its functions in α-syn clearance. This dual involvement positions cathepsin B as a potentially significant modulator at the intersection of AD and PD pathology.

Table 1: Cathepsin B Functions in Neurodegenerative Protein Processing

| Biological Context | Effect on α-Synuclein | Effect on Amyloid-β | Net Pathological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Lysosomal Function | Cleaves monomeric and fibrillar α-syn [10] | Limited data; potential cleavage of Aβ species | Protective through aggregate clearance |

| Reduced Expression/Activity | Impaired α-syn fibril degradation; increased p-α-syn inclusions [10] | Predicted increased Aβ accumulation based on parallel pathways | Pathogenic through reduced clearance |

| Inflammatory Milieu | Potential enhanced cleavage generating aggregation-prone truncations [10] | Possible altered processing | Context-dependent: protective or pathogenic |

| Genetic Risk Variants | Reduced clearance capacity; increased Lewy body pathology risk [10] | Theoretical increased plaque deposition risk | Increased overall neurodegenerative risk |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Cathepsin B Functional Analysis

Genetic Manipulation Approaches

Investigations into cathepsin B function have employed sophisticated genetic models to establish causal relationships between enzyme activity and protein clearance. Both knockout and activation models have been developed across different cellular systems:

CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Generation: CTSB-knockout induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines are created using single-guide RNA (gRNA) targeting exon 4 with a single-stranded DNA repair template to introduce a stop codon. Transfected iPSCs are selected via puromycin resistance, with edited clones verified by digital PCR and Western blot confirmation of protein loss [10].

Gene Activation Strategies: CTSB gene activation utilizes CRISPR-based synergistic activation mediators (SAM) to enhance endogenous expression. This approach increases cathepsin B transcription without overexpression artifacts, providing a physiologically relevant model to study enhanced clearance capacity [10].

iPSC-Derived Neuronal Models: Human iPSCs are differentiated into dopaminergic neurons using patterned growth factors (e.g., bFGF, heregulin, activin A, IGF-1) with ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) added during final maturation stages. These models recapitulate disease-relevant vulnerability and allow assessment of α-syn clearance in human neuronal populations [10] [12].

Pharmacological Modulation Protocols

Complementing genetic approaches, pharmacological tools enable acute manipulation of cathepsin B activity:

Cathepsin B Inhibitors: CA-074Me is a cell-permeable cathepsin B-specific inhibitor administered at concentrations ranging from 10-100 μM for 24-72 hours. Treatment efficacy is validated through fluorometric activity assays using Z-Arg-Arg-AMC substrates [10] [11].

Lysosomal Function Assessment: Concomitant evaluation of lysosomal integrity is performed using LysoTracker staining for lysosomal acidity and immunoblotting for LAMP1/LAMP2 to assess lysosomal membrane stability [10].

Protein Aggregation and Clearance Assays

Standardized methodologies for generating and quantifying protein aggregates are essential for clearance studies:

α-Syn Preformed Fibrils (PFF) Production: Recombinant monomeric α-syn (5mg/ml in PBS) is agitated at 1000 rpm for 7 days at 37°C. Fibrils are sonicated (20% amplitude, 1s on/off for 30s) before use to ensure uniform fragmentation [10] [12].

Aβ Fibril Generation: Synthetic Aβ42 monomers are dissolved in 10mM NaOH/PBS (2mg/ml) and agitated at 1500 rpm for 4 days at 37°C. Cy3-labeling enables fluorescence-based quantification [12].

Clearance Quantification: Cells are exposed to sonicated fibrils (1-5μg/ml) for 24-72 hours. Internalized aggregates are quantified via ELISA, immunocytochemistry, or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [10] [12]. Clearance rates are calculated as the percentage reduction in intracellular aggregates over time.

Cathepsin B in α-Synuclein Clearance: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

The role of cathepsin B in α-synuclein clearance exemplifies the complex balance between protective and potentially detrimental effects in protein quality control. Evidence from multiple experimental systems indicates that cathepsin B promotes the lysosomal degradation of α-syn aggregates through several interconnected mechanisms.

Genetic and pharmacological studies demonstrate that cathepsin B reduction impairs autophagy, decreases glucocerebrosidase activity, and leads to accumulation of lysosomal content, ultimately reducing clearance of α-syn fibrils [10]. Conversely, CTSB gene activation enhances fibril clearance capacity, supporting a protective role. In midbrain organoids and iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons, cathepsin B inhibition potentiates the formation of phosphorylated α-syn inclusions following exposure to preformed fibrils [10]. This clearance function occurs within the broader context of the autophagy-lysosomal pathway, where fibrillar α-syn is primarily targeted by autophagy while monomeric or prefibrillar species are handled by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and chaperone-mediated autophagy [13].

The cellular context significantly influences cathepsin B's effects. In microglia, cathepsin B participates in P62-mediated selective autophagy of α-syn fibrils, while in astrocytes, different mechanisms predominate [13]. Importantly, crosstalk between these cell types enhances overall clearance capacity. Co-cultures of astrocytes and microglia demonstrate significantly reduced intracellular α-syn deposits compared to monocultures, with live imaging revealing that microglia can attract and clear protein deposits from astrocytes through direct membrane contacts and tunneling nanotubes [12].

Table 2: Experimental Findings on Cathepsin B in α-Synuclein Clearance

| Experimental System | Intervention | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons | CTSB knockout vs. activation | KO: impaired fibril clearance; Activation: enhanced clearance | [10] |

| Neuroglioma cells | CTSB siRNA knockdown | Reduced degradation of α-syn preformed fibrils | [10] |

| Midbrain organoids | CA-074Me inhibition | Increased phosphorylated α-syn inclusions | [10] |

| Astrocyte-microglia co-culture | None (comparative analysis) | Enhanced aggregate clearance compared to monocultures | [12] |

| In vitro enzymatic assays | Recombinant cathepsin B | Cleaves both monomeric and fibrillar α-syn | [10] |

Cathepsin B in Alpha-Synuclein Clearance Pathways

Cathepsin B in Amyloid-Beta Processing: Emerging Connections

While cathepsin B's role in α-synuclein clearance is relatively well-established, its involvement in amyloid-beta processing represents an emerging frontier with significant implications for AD pathophysiology and the interconnection between neurodegenerative processes. The current understanding of these relationships, though less comprehensive, points to complex interactions within the protein triumvirate of Aβ, tau, and α-syn [8] [9].

Protein interactome analyses reveal that Aβ, tau, and α-syn operate within a connected network, where each can influence the aggregation and toxicity of the others [9]. Within this framework, cathepsin B emerges as a potential modulator of Aβ pathology through several hypothesized mechanisms. As a lysosomal protease, cathepsin B likely participates in Aβ degradation through the endosomal-lysosomal system, similar to its role in α-syn clearance. Additionally, cathepsin B may indirectly influence Aβ generation through its interactions with other proteases involved in amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing [9].

The crosstalk between Aβ and α-syn pathologies provides another dimension to cathepsin B's potential involvement. Studies indicate that Aβ plaque deposition can dramatically accelerate both the seeding and spreading of α-syn aggregation in the brain [9]. This synergistic relationship may create a feed-forward cycle of protein aggregation that cathepsin B could potentially modulate through its dual substrate specificity. Furthermore, the observed co-existence of Aβ and α-syn pathologies in a majority of autopsied AD brains suggests the possible involvement of shared clearance mechanisms, with cathepsin B as a plausible candidate [14] [8].

Table 3: Cathepsin B and Amyloid-β: Evidence and Potential Mechanisms

| Evidence Type | Findings | Implications for Aβ Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Interactome Analysis | APP, MAPT, and SNCA share common interactors and pathways [9] | Cathepsin B may operate at intersection of Aβ and α-syn pathologies |

| Pathological Co-existence | Aβ/α-syn/tau co-pathology in >50% of AD brains [14] [8] | Suggests shared clearance mechanisms potentially involving cathepsin B |

| Cross-promotion of Aggregation | Aβ accelerates α-syn seeding and spreading [9] | Cathepsin B may modulate this synergistic toxicity |

| Therapeutic Targeting | Multi-target approaches needed for mixed proteinopathies [8] | Supports cathepsin B as potential target for combined pathology |

Integrated Experimental Workflow for Cathepsin B Functional Analysis

A comprehensive approach to evaluating cathepsin B in neurodegenerative protein processing requires the integration of methodological streams across cellular models, functional assays, and analytical endpoints. The following workflow provides a structured framework for investigating cathepsin B's dual roles in Aβ and α-syn pathology.

Cathepsin B Investigation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Cathepsin B Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Cathepsin B Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons [10], Human iPSC-derived astrocytes [12], Microglia [12] | Physiological relevance for neurodegenerative studies | Co-culture systems enhance physiological mimicry [12] |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 CTSB knockout constructs [10], CTSB activation systems [10], siRNA/shRNA | Mechanistic studies of CTSB function | Verify edits with sequencing and Western blot [10] |

| Pharmacological Modulators | CA-074Me (CTSB inhibitor) [10] [11], Cathepsin B activators | Acute modulation of enzyme activity | Validate efficacy with activity assays [10] |

| Protein Aggregates | α-Syn preformed fibrils [10] [12], Aβ fibrils [12] | Substrate for clearance assays | Standardize sonication protocols for reproducibility [12] |

| Activity Assays | Z-Arg-Arg-AMC substrate [10], Lysotracker staining [10], LAMP1/2 immunoblotting | Functional assessment of lysosomes | Multiplex approaches recommended [10] |

| Detection Methods | Phospho-α-syn antibodies [10], ELISA for protein quantification [12], Live-cell imaging [12] | Quantification of pathology and clearance | Combine methods for validation |

Cathepsin B occupies a critical position at the intersection of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta processing and Parkinson's disease alpha-synuclein clearance pathways. The experimental evidence demonstrates that cathepsin B promotes clearance of α-synuclein aggregates through lysosomal degradation mechanisms, with reduced activity impairing autophagy and increasing pathological inclusions. While direct evidence for cathepsin B's role in amyloid-beta processing remains more limited, its position within the interconnected network of neurodegenerative proteinopathies suggests broader involvement in protein homeostasis.

The complex, context-dependent nature of cathepsin B function—with both protective and potentially detrimental effects—highlights the importance of sophisticated experimental approaches that capture the intricacies of protein clearance pathways. The integrated methodological framework presented here provides researchers with a systematic approach for investigating cathepsin B in neurodegenerative processes, with particular utility for evaluating therapeutic strategies targeting lysosomal function in protein aggregation disorders. Future research elucidating the precise mechanisms governing cathepsin B's dual roles may yield valuable insights for developing targeted interventions for Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and related neurodegenerative conditions characterized by mixed proteinopathies.

Cathepsin B (CatB) is a lysosomal cysteine protease belonging to the papain superfamily that plays crucial roles in both physiological and pathological processes. Unlike other members of this family, cathepsin B possesses a unique structural feature—a 20-residue insertion called the occluding loop—that enables its dual endopeptidase and exopeptidase (peptidyldipeptidase) activities [15]. This loop, which blocks the primed terminus of the active site cleft, contains two adjacent histidine residues (H110 and H111) that provide positive charges to anchor the negatively-charged C-terminal carboxylate of exo-substrates [16]. The structural versatility of cathepsin B, particularly its sensitivity to pH changes and the dynamic nature of its occluding loop, makes it a compelling target for drug development in conditions ranging from cancer and Alzheimer's disease to traumatic brain injury [17] [16] [18].

The enzyme's active site comprises the canonical catalytic triad of cysteine proteases (C29, H199, and N219), with the interdomain interface forming the active site cleft that accommodates substrate binding [16]. Cathepsin B's activity is strongly pH-dependent, with optimal function in acidic environments (pH 4.5-5.5) but significant activity preservation possible at neutral pH under certain conditions, particularly when stabilized by interactions with molecules like heparin [16]. This pH sensitivity is governed by protonation state changes in key residues, including those in the active site and occluding loop, which alter electrostatic potential and structural dynamics [16]. Understanding these structural features is essential for developing effective inhibitors that can target cathepsin B in various disease contexts.

Active Site Architecture and Occluding Loop Mechanism

Structural Components of the Catalytic Machinery

The active site of cathepsin B is formed at the interface between two distinct domains that create a large polar surface area. The catalytic residues C29, H199, and N219 project their side chains into this interface, forming the essential machinery for peptide bond hydrolysis [16]. The cysteine residue (C29) acts as a nucleophile, while the histidine (H199) functions as a general base/acid during the catalytic cycle. Asparagine (N219) helps orient the histidine residue for optimal catalysis. This active site cleft runs the length of the enzyme surface and is partially obstructed on its prime side by the unique occluding loop, which confers cathepsin B with its distinctive exopeptidase capability [15].

The occluding loop represents a 20-residue insertion not found in other papain-family enzymes, with the 12 central residues being particularly critical for function. This structural element controls access to the active site for larger substrates while providing the molecular architecture necessary for dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase activity [15]. Site-directed mutagenesis studies have confirmed that deletion of the entire occluding loop or its central portion completely abolishes exopeptidase activity while preserving endopeptidase function [15] [16]. Additionally, the occluding loop contributes to thermal stability and provides resistance against endogenous inhibitors like cystatin C, which shows 40-fold higher affinity for cathepsin B when the occluding loop is modified or deleted [15].

Molecular Mechanism of the Occluding Loop

The occluding loop functions as a structural gatekeeper that regulates substrate access and enzyme specificity. The two histidine residues (H110 and H111) located on this loop create a positively charged patch that specifically interacts with the C-terminal carboxylate group of peptide substrates, facilitating the exopeptidase activity by which cathepsin B removes dipeptides from the C-terminus of proteins [16]. This mechanism is unique to cathepsin B within the papain family and expands its functional repertoire beyond the endopeptidase activity characteristic of other cysteine cathepsins.

During proenzyme activation, the occluding loop undergoes significant reorientation to accommodate binding of the propeptide, which itself is a potent inhibitor of the enzyme [15]. This structural rearrangement is essential for the transition from zymogen to active enzyme, with the propeptide binding affinity increasing 50-fold when the occluding loop is altered, indicating strong interactions between these structural elements [15]. The flexibility and dynamic motions of the occluding loop, particularly under different pH conditions, contribute importantly to regulating cathepsin B activity and inhibition.

Figure 1: Occluding Loop Functional Relationships. The occluding loop, containing H110-H111, regulates exopeptidase activity, while the active site residues (C29-H199-N219) mediate endopeptidase function.

pH-Dependent Structural Dynamics and Activity Regulation

Molecular Basis of pH Sensitivity

Cathepsin B exhibits remarkable sensitivity to pH changes, which significantly impacts its structural stability and catalytic efficiency. The enzyme is normally active within acidic lysosomes (pH ~4.6-5.5) but can also function in neutral environments (pH ~7.2) under certain pathological conditions [16] [19]. This pH-dependent behavior stems from alterations in the protonation states of key titratable residues, particularly at the interdomain interface and within the active site. Computational pKa calculations have identified six key residues that display distinct protonation states under different pH conditions: E36, H199, E171, H110, H97, and H190 [16].

At alkaline pH, the catalytic histidine (H199) undergoes deprotonation, which subsequently affects the ionization state of the catalytic cysteine (C29), shifting its pKa from approximately 3.7 at pH 5.5 to 7.3 at pH 8.0 [16]. This coupling between H199 and C29 ionization states directly impacts catalytic efficiency. Similarly, H110 in the occluding loop shows altered protonation states with pH changes, affecting its ability to anchor substrate C-terminal and thereby modulating exopeptidase activity. These protonation changes collectively alter the electrostatic potential at the cathepsin B surface, influencing substrate binding, inhibitor affinity, and overall structural stability.

pH-Mediated Structural Changes and Heparin Stabilization

Under alkaline conditions, cathepsin B undergoes significant structural destabilization characterized by increased overall flexibility, loss of interactions between active site residues, decreased helical content, and domain separation [16]. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that the occluding loop exhibits particularly high-amplitude motions at neutral/alkaline pH, compromising its gatekeeping function and contributing to enzyme inactivation [16]. These structural changes explain the rapid inactivation of cathepsin B observed at physiological pH when not stabilized by co-factors or specific interactions.

Heparin and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) can prevent pH-induced inactivation by binding to basic surface regions on cathepsin B and restricting enzyme flexibility [16]. This interaction promotes rearrangement of contacts between cathepsin B domains, maintains helical content, and stabilizes the active site configuration. Molecular docking studies have identified two primary heparin-binding sites on cathepsin B, through which heparin exerts an allosteric stabilizing effect that modulates large-amplitude motions, particularly in the occluding loop [16]. This protective mechanism explains how membrane-associated forms of cathepsin B resist alkaline inactivation in physiological environments.

Figure 2: pH-Dependent Activity Regulation. Cathepsin B remains stable and active at acidic pH but becomes unstable at alkaline pH unless stabilized by heparin binding.

Comparative Analysis of Cathepsin B Inhibitor Classes

Performance Comparison of Inhibitor Strategies

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cathepsin B Inhibitor Classes

| Inhibitor Class | Representative Compounds | Mechanism of Action | pH Selectivity | Key Molecular Interactions | Experimental IC₅₀/Ki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occluding Loop-Targeted | E-64 derivatives [20] | Binds occluding loop His pairs | Poor above pH 5.5 | Ionic interaction with H110-H111 | ~nM range at pH ≤5.5 [20] |

| pH-Selective Inhibitors | Z-Arg-Lys-AOMK [19] | Irreversible active site binding | 100-fold selective for pH 7.2 | Catalytic C29, occluding loop residues | Low nM at pH 7.2 [19] |

| Natural Product Inhibitors | Nicandrenone, Picrasidine M [18] | Competitive active site binding | Variable | Trp30, Trp221, catalytic residues | Superior binding affinity in silico [18] |

| Repurposed Drugs | Lurasidone, Paliperidone [21] | Catalytic pocket binding | Under investigation | Multiple active site residues | Stable complexes in 500ns MD [21] |

| Peptidic Inhibitors | CA-074Me [18] [21] | Irreversible active site inhibitor | Limited | Gln23, Cys29, His199, Trp221 | Reference compound [18] |

Structural Basis for Inhibitor Efficacy

The comparative analysis of cathepsin B inhibitors reveals distinct structure-activity relationships governed by interactions with both the active site and occluding loop. Inhibitors targeting the occluding loop, such as E-64 derivatives, show strong pH dependence with dramatically reduced efficacy (decreased kinact/KI) as pH increases from 4 to 7.8, corresponding to a single ionization event with pKa 4.4 [20]. This limitation has prompted the development of pH-selective inhibitors like Z-Arg-Lys-AOMK, which was rationally designed based on cathepsin B's preference for cleaving peptides with Arg in the P2 position at neutral pH, contrasted with its preference for Glu in P2 at acidic pH [19].

Natural products and repurposed drugs represent promising avenues for cathepsin B inhibition, with compounds like Nicandrenone and Picrasidine M demonstrating superior binding affinities and robust interactions with catalytic residues in molecular dynamics simulations [18]. Similarly, repurposed antipsychotics Lurasidone and Paliperidone form stable complexes with cathepsin B throughout 500ns MD simulations, suggesting their potential as lead compounds for further development [21]. These inhibitors typically engage key residues including Trp30, Cys29, His110, His111, and His199, leveraging both the active site machinery and occluding loop interactions for selective inhibition.

Experimental Methodologies for Cathepsin B Research

Key Experimental Protocols

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Deletion Analysis: Fundamental insights into occluding loop function have been obtained through deletion mutagenesis studies where all or part of the 20-residue occluding loop was removed [15]. Experimental protocols involve generating human procathepsin B variants with specific deletions, expressing them in yeast systems like Pichia pastoris, and comparing autoprocessing kinetics and enzymatic activities of mutant versus wild-type enzymes. These studies have confirmed that deletion of the 12 central residues abolishes exopeptidase activity while maintaining endopeptidase function, and significantly increases affinity for inhibitors like cystatin C and the propeptide [15].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of pH Effects: Detailed protocols for assessing pH-dependent structural changes involve molecular dynamics simulations using different protonation states corresponding to acidic (pH 5.5) and alkaline (pH 8.0) conditions [16]. Simulations typically run for 40ns or longer, analyzing parameters such as hydrogen bond occupancy, helical content preservation, domain separation, and occluding loop mobility. These studies incorporate pKa predictions from tools like PROPKA to determine appropriate protonation states for titratable residues under different pH conditions [16]. MD simulations have also been used to validate the stabilizing effect of heparin binding on cathepsin B structure at alkaline pH.

Virtual Screening for Inhibitor Identification: Computational screening approaches employ structure-based virtual screening of large compound libraries (e.g., IMPPAT 2 with ~18,000 phytochemicals or DrugBank with ~3,500 FDA-approved drugs) [18] [21]. Standard protocols include molecular docking with tools like AutoDock or InstaDock, followed by molecular dynamics simulations of 100-500ns to assess complex stability [18] [21]. Additional filtering includes pharmacokinetic profiling, ADMET prediction, and binding free energy calculations using MM-GBSA/PBSA methods [17] [18]. These workflows have successfully identified novel natural product inhibitors and repurposed drug candidates with high binding affinity and specificity for cathepsin B.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Approaches

QSAR modeling represents a powerful tool for investigating correlations between chemical structures and anti-cathepsin B activity [22]. Experimental protocols involve calculating molecular descriptors representing physical, chemical, structural, and geometric properties of compounds, followed by data preprocessing and feature selection to reduce descriptor complexity. Key preprocessing methods include filtering approaches like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and wrapping methods such as Forward Selection (FS), Backward Elimination (BE), and Stepwise Selection (SS) [22]. These methods, particularly when coupled with nonlinear regression models, have demonstrated promising performance in predicting IC₅₀ values for anti-cathepsin B compounds, enabling more efficient lead compound optimization.

Figure 3: Virtual Screening Workflow. Computational pipeline for identifying cathepsin B inhibitors from large compound libraries.

Research Reagent Solutions for Cathepsin B Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cathepsin B Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | Pichia pastoris [15] | Recombinant cathepsin B production | Proper folding, post-translational modifications |

| Reference Inhibitors | CA-074Me, E-64 [18] [21] | Experimental controls, validation | Well-characterized specificity, potency |

| Activity Assays | Z-Phe-Arg-AMC [19] | Enzymatic activity measurement | Fluorogenic substrate, continuous monitoring |

| Structural Biology Resources | PDB IDs: 1GMY, 1CSB [18] [23] | Molecular docking, structure analysis | High-resolution crystal structures |

| Computational Tools | AutoDock, InstaDock [23] [21] | Virtual screening, binding pose prediction | Automated workflows, high throughput |

| MD Simulation Software | AMBER, GROMACS [16] | Dynamics, stability assessment | pH-dependent protonation states |

| Specialized Substrates | Z-Arg-Lys-AMC [19] | pH-dependent activity profiling | Selective for neutral pH activity |

The structural biology of cathepsin B reveals a sophisticated enzymatic machinery whose function is intricately regulated by its unique occluding loop and sensitive to pH-induced conformational changes. The occluding loop serves as a structural determinant for exopeptidase activity and modulates inhibitor access to the active site, while pH-dependent protonation states of key residues govern catalytic efficiency and structural stability. These insights have enabled the development of increasingly sophisticated inhibitor strategies, from early occluding loop-targeted compounds to advanced pH-selective inhibitors that capitalize on cathepsin B's differential cleavage preferences at neutral versus acidic pH.

Future research directions should focus on leveraging these structural insights to develop context-specific inhibitors that target cathepsin B in particular cellular compartments or disease states without disrupting its physiological functions. The promising results from natural product screening and drug repurposing efforts provide diverse chemical starting points for optimization. As structural characterization methods continue to advance, particularly in capturing dynamic enzyme states and protein-ligand interactions under physiologically relevant conditions, our understanding of cathepsin B biology will further deepen, enabling more precise therapeutic targeting of this multifunctional protease in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other pathological conditions.

Cysteine cathepsins are a family of lysosomal proteolytic enzymes that play critical roles in protein turnover, antigen presentation, and various other physiological processes. As members of the papain-like protease family, their activity must be precisely regulated to prevent inappropriate tissue damage and maintain cellular homeostasis. Unregulated cathepsin activity has been implicated in numerous pathological conditions, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory disorders. The primary endogenous regulators of these enzymes are protein inhibitors known as cystatins, which comprise a superfamily of tight-binding, reversible inhibitors that control cysteine protease activity in intracellular and extracellular environments.

The cystatin superfamily is classified into three types based on their structural characteristics and subcellular localization. Type 1 cystatins (stefins A and B) are intracellular proteins of approximately 100 residues that lack disulfide bonds and secretion signal peptides. Type 2 cystatins (C, D, E, F, S, SA, and SN) are secreted proteins of about 120 amino acids that contain two conserved disulfide crosslinks and a secretion signal sequence. Type 3 cystatins are the kininogens, which are multidomain plasma proteins containing three type-2 cystatin-like domains, one of which is inactive as a protease inhibitor [24]. This review will focus specifically on the comparative analysis of Stefin A (cystatin A) and cystatin C, two prominent members of this inhibitor family that play crucial yet distinct roles in regulating cysteine cathepsin activity in physiological and pathological contexts, with particular emphasis on their performance in cathepsin B, S, D, and K inhibition models relevant to current research.

Comparative Structural and Functional Characteristics

Molecular Structures and Inhibition Mechanisms

Stefin A and cystatin C share a common evolutionary origin and structural fold despite their different subcellular localizations and biological functions. Both inhibitors feature a conserved five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet wrapped around a five-turn α-helix, forming a wedge-shaped structure that inserts into the active site of target cysteine cathepsins [24]. However, they differ significantly in their precise mechanisms of interaction with various cathepsins.

The molecular mechanism of inhibition involves three distinct contact regions that contribute differently to the binding energy. Kinetic studies with natural and recombinant variants reveal that for chicken cystatin (homologous to human cystatin C), the N-terminal segment contributes approximately 36% of the binding energy for papain complexes, while the first hairpin loop contributes 51%, and the second hairpin loop contributes 13% [25]. The essential nature of the N-terminal region is demonstrated by the dramatic 10,000-fold reduction in affinity for papain when this segment is removed from chicken cystatin. Interestingly, Stefin B (closely related to Stefin A) remains a tight-binding inhibitor of papain and actinidin even without its N-terminal segment, suggesting structural and functional differences in the inhibition mechanisms between type 1 and type 2 cystatins [25].

Structural analyses of complexes reveal that Stefin A binds deeper in the active site cleft of cathepsin H than Stefin B does in papain [24]. The N-terminal residues of Stefin A form a short turn that creates a hook structure, which pushes away the mini-chain in the active site cleft of cathepsin H, resulting in an "S-shaped" bend instead of the extended conformation observed in cathepsin H alone. This binding interaction induces significant conformational changes in cathepsin H, including disordered structure in a short insertion that normally forms a loop in the free enzyme [24].

Table 1: Structural and Functional Characteristics of Stefin A and Cystatin C

| Characteristic | Stefin A (Cystatin A) | Cystatin C |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Type 1 cystatin (stefin) | Type 2 cystatin |

| Molecular Weight | ~100 residues (11 kDa) | ~120 residues (13 kDa) |

| Structural Features | Single chain, no disulfide bonds | Two conserved disulfide crosslinks |

| Subcellular Localization | Intracellular | Extracellular, secreted |

| Signal Peptide | Absent | Present (26 amino acids) |

| Tissue Distribution | Restricted (mainly epidermal cells) | Ubiquitous (all nucleated cells) |

| Binding Regions | N-terminus and two hairpin loops | N-terminus and two hairpin loops |

| Inhibition Mechanism | Competitive, tight-binding | Competitive, tight-binding |

Tissue Distribution and Expression Patterns

The tissue distribution of Stefin A and cystatin C reflects their distinct biological roles. Stefin A demonstrates a restricted tissue distribution, being found mainly in epidermal cells and exhibiting limited expression patterns. In contrast, cystatin C is widely expressed across virtually all nucleated cells in the body and is constitutively produced at a constant rate [24] [26]. This ubiquitous expression pattern aligns with cystatin C's role as a general extracellular regulator of cysteine protease activity.

The differential expression extends to pathological conditions. In colorectal cancer, Stefin A and cystatin C levels are moderately increased in patient sera (1.4-fold and 1.6-fold respectively compared to healthy controls), while Stefin B levels remain statistically unchanged [27]. In squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), cystatin C levels in tumor tissue were found to be 1.18 times lower than in corresponding normal mucosa, with the degree of reduction correlating with disease progression [26].

Inhibitory Performance Against Key Cathepsins

Quantitative Inhibition Profiles

The inhibitory efficacy of Stefin A and cystatin C varies significantly across different cysteine cathepsins, reflecting their specialized biological functions. Both inhibitors display distinctive affinity profiles for cathepsins B, H, L, and S, with important implications for their physiological roles and potential therapeutic applications.

Table 2: Inhibition Constants (Kᵢ) of Stefin A and Cystatin C for Various Cysteine Cathepsins

| Target Enzyme | Stefin A Kᵢ (M) | Cystatin C Kᵢ (M) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin B | Weaker inhibitor [24] | Weaker inhibitor [24] | Mouse stefins A & B comparison |

| Cathepsin H | 0.31 × 10⁻⁶ [24] | < 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ [24] | Human liver-derived inhibitors |

| Cathepsin L | Variable inhibition [24] | Potent inhibition [24] | General characteristic |

| Cathepsin S | Limited data | Potent inhibition [28] | Specific interaction |

| Papain | 10000-fold lower affinity without N-terminal segment [25] | Tight-binding [25] | Recombinant variant studies |

The data reveals that cystatin C generally demonstrates higher affinity for most cathepsins compared to Stefin A, particularly for cathepsin H where cystatin C exhibits sub-nanomolar inhibition (Kᵢ < 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ M) compared to Stefin A's micromolar range inhibition (Kᵢ = 0.31 × 10⁻⁶ M) [24]. This approximately 3000-fold difference in inhibitory potency highlights the specialized functions of these inhibitors, with cystatin C serving as a potent extracellular regulator, while Stefin A functions primarily in intracellular compartments.

For cathepsin B, both Stefin A and cystatin C demonstrate relatively weaker inhibition compared to their effects on other cathepsins. Studies indicate that inhibition of cathepsin B by stefins A and B follows a slow-binding mechanism, with stefin B exhibiting a two-step mechanism involving slow isomerization of the enzyme-inhibitor complex [25]. This relatively weaker inhibition of cathepsin B may reflect this enzyme's unique structural features, including its occluding loop that potentially interferes with inhibitor binding.

Specificity and Binding Affinity Considerations

The specificity of Stefin A and cystatin C for different cathepsins is influenced by structural variations in both the enzymes and inhibitors. For instance, the first hairpin loop plays a critical role in determining binding specificity, as demonstrated by a Val48→Asp mutant of stefin B that exhibited a 240-fold lower affinity for papain [25]. Similarly, single amino acid substitutions in Stefin A can significantly impact its inhibitory capacity, with the E94K mutation in Stefin A decreasing binding affinity for cathepsin B by approximately 8% and resulting in complex instability during molecular dynamics simulations [29].

The S2 and S3 pockets of cathepsins represent key determinants of inhibitor specificity. These structural features are particularly important for distinguishing between highly similar cathepsins such as S, K, and L, which share more than 57% amino acid sequence identity [28]. While detailed structural studies of Stefin A and cystatin C with these specific cathepsins are limited, the general principle that the S2 and S3 pockets govern inhibitor selectivity underscores the importance of these regions for understanding the differential inhibitory profiles of physiological cystatins.

Experimental Methodologies for Inhibitor Characterization

Kinetic Characterization Protocols

The determination of inhibition constants and mechanisms for Stefin A and cystatin C typically employs well-established enzymological approaches. The standard methodology involves incubating fixed concentrations of cysteine cathepsins with varying concentrations of inhibitors across appropriate pH ranges (typically pH 5.0-7.5 for most cathepsins), using fluorogenic or chromogenic substrates to monitor residual enzyme activity.

For determination of inhibition constants (Kᵢ values), the general experimental workflow follows these key steps:

- Enzyme Activation: Pre-incubate procathepsins in activation buffer (e.g., 100 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, pH 5.5) at 37°C for 15-30 minutes to generate mature enzymes.

- Inhibitor Titration: Prepare serial dilutions of purified Stefin A or cystatin C in appropriate assay buffer.

- Reaction Setup: Incubate activated enzyme with different inhibitor concentrations for a fixed time period (typically 15-60 minutes) to allow complex formation.

- Activity Measurement: Add specific substrate (e.g., Z-FR-AMC for cathepsin B or Z-VVR-AMC for cathepsin S) and monitor product formation continuously using a fluorometer or spectrophotometer.

- Data Analysis: Calculate residual enzyme activity and determine Kᵢ values using appropriate inhibition models (competitive, non-competitive, or mixed-type) through nonlinear regression analysis of dose-response data [25] [24].

Slow-binding inhibition, as observed for stefins A and B with cathepsin B, requires more specialized kinetic approaches involving pre-incubation of enzyme and inhibitor for extended time periods followed by measurement of reaction progress curves to determine association and dissociation rate constants [25].

Structural Analysis Techniques

Structural characterization of Stefin A and cystatin C complexes with target cathepsins employs both X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The crystallographic analysis of human Stefin A in complex with cathepsin H revealed the deep binding mode of Stefin A within the active site cleft and the associated conformational changes in both molecules [24].

The standard protocol for structural analysis includes:

- Protein Purification: Recombinant expression in E. coli or eukaryotic systems followed by affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Complex Formation: Incubation of purified cathepsins with stoichiometric amounts of inhibitors under controlled conditions.

- Crystallization: Screening of numerous crystallization conditions using robotic systems and optimization of initial hits.

- Data Collection and Structure Determination: X-ray diffraction data collection at synchrotron sources followed by molecular replacement or experimental phasing and iterative model building and refinement [24] [29].

For dynamic studies of inhibitor binding, molecular dynamics simulations provide complementary information about complex stability and flexibility, as demonstrated in the analysis of Stefin A mutants with reduced affinity for cathepsin B [29].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Cystatin-Cathepsin Interactions

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Cystatin-Cathepsin Interactions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Human recombinant cystatin C [26], Stefin A variants [29] | Kinetic studies, structural biology, cellular assays | High purity (>95%), confirmed activity, endotoxin-free for cellular studies |

| Activity Assays | Fluorogenic substrates (Z-FR-AMC, Z-VVR-AMC) [28] | Enzyme activity measurements, inhibition constant determination | Cathepsin-specific, sensitive fluorescence detection, suitable for continuous assays |

| Antibodies | Monoclonal anti-cystatin C (1A2) [26], polyclonal anticystatin C IgG | ELISA, Western blot, immunohistochemistry | Specific for native and complexed forms, no cross-reactivity with related inhibitors |

| Cell-Based Models | iPSC-derived neurons [30], cancer cell lines | Functional validation, pathological relevance | Disease-relevant context, reproducible phenotype, tractable for manipulation |

| Clinical Samples | Paired tumor-normal tissues [26], patient sera [27] | Correlation with disease progression, prognostic significance | Well-annotated clinical data, proper preservation, ethical approval |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for generating reliable data on cystatin-cathepsin interactions. The monoclonal antibody 1A2 specifically recognizes both recombinant and native human cystatin C without cross-reactivity to closely related inhibitors like stefins A and B, making it invaluable for immunoassays [26]. For kinetic studies, recombinant proteins expressed in E. coli systems maintain proper folding and inhibitory function while allowing production of mutant variants for structure-function studies [29] [26].

Pathological Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Role in Disease Pathogenesis

Dysregulation of the balance between cysteine cathepsins and their endogenous inhibitors contributes significantly to various pathological conditions. In cancer progression, altered expression of Stefin A and cystatin C correlates with clinical outcomes across multiple cancer types. In colorectal cancer, high serum levels of stefin B and cystatin C are associated with significantly increased risk of death (hazard ratio = 1.6 and 1.3, respectively) [27]. For squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN), low tumor levels of cystatin C predict poor disease-free survival (P = 0.013) and disease-specific survival (P = 0.013) in univariate analysis [26].

In neurodegenerative disorders, the cystatin-cathepsin axis plays important roles in protein aggregation clearance. Recent research demonstrates that recombinant cathepsins B and L promote α-synuclein clearance and restore lysosomal function in human and murine models with α-synuclein pathology, suggesting therapeutic potential for Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies [30]. Interestingly, muscle-derived cathepsin B has been shown to improve motor coordination, memory function, and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's Disease mouse model, highlighting the complex interplay between different proteolytic systems across tissues [31].

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Potential

The consistent production rate of cystatin C by all nucleated cells has established it as a superior biomarker for glomerular filtration rate (GFR) compared to creatinine, particularly in special populations like children with posterior urethral valves where muscle mass and nutritional status vary considerably [32]. Creatinine-based formulas consistently yield slightly higher eGFR values (median differences of 1.5 to 2.6 mL/min/1.73 m²) compared to cystatin C-based methods, potentially reflecting creatinine's susceptibility to extrarenal factors like muscle mass [32].

Therapeutic targeting of the cystatin-cathepsin axis represents an emerging frontier in drug development. For cathepsin S, involved in various disease pathophysiologies including autoimmune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, extensive efforts have been made to develop specific inhibitors [28]. The development of selective cathepsin inhibitors must address the challenge of significant structural similarities between different cathepsin family members, particularly in the S2 and S3 substrate binding pockets that determine inhibitor specificity [28].

Figure 2: Physiological and Pathological Consequences of Cystatin-Cathepsin Balance

Stefin A and cystatin C represent two essential components of the physiological regulatory system for cysteine cathepsin activity, each with distinct structural characteristics, inhibitory profiles, and biological functions. While both inhibitors employ a conserved structural fold to block the active sites of their target enzymes, they demonstrate marked differences in specificity and affinity across the cathepsin family. Cystatin C generally exhibits higher affinity for most cathepsins and serves as the primary extracellular regulator, while Stefin A functions predominantly in intracellular compartments with a more restricted tissue distribution.

The performance evaluation of these physiological inhibitors reveals a sophisticated regulatory network where relatively small structural differences translate into significant functional specialization. The differential expression patterns and distinct inhibitory profiles of Stefin A and cystatin C enable precise spatial and temporal control of cathepsin activity under physiological conditions. Dysregulation of this balance contributes to various pathological processes, particularly in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting these natural regulatory pathways. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise structural determinants of inhibitor specificity and developing therapeutic strategies that restore the natural balance between cysteine cathepsins and their physiological inhibitors in disease states.

Cathepsin B (CTSB), a lysosomal cysteine protease, is a pivotal enzyme in cellular homeostasis and a significant player in cancer progression. Its role, however, is not monolithic; it exhibits profound context-dependency, varying across cancer types, cell lines, and physiological conditions. Understanding these expression patterns and the intricate balance between CTSB and its endogenous inhibitor, Stefin A (STFA), is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies. This guide objectively compares CTSB expression and function across various cancer models, providing a foundation for evaluating CTSB-targeted inhibition models in oncological research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of CTSB/STFA Expression and Function

The interplay between CTSB and its natural inhibitor, Stefin A (STFA), is a critical determinant of proteolytic activity and tumor progression. The table below summarizes the expression patterns and functional outcomes of the CTSB/STFA axis across different cellular contexts.

Table 1: CTSB/STFA Expression Patterns and Functional Correlations Across Cell Lines

| Cell Line / Cancer Type | CTSB Expression & Activity | STFA Expression & Regulation | Key Phenotypic Outcomes | Clinical/Experimental Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal Cancer (769-P) | High expression and activity [33] [34]. | Impaired regulatory feedback; CTSB overexpression alters STFA levels [33]. | Promotes invasion and metastasis [33]. | Correlates with advanced tumor stages and poor prognosis [34]. |

| Prostate Cancer (Du145) | High expression and activity [33] [34]. | Impaired regulatory feedback [33]. | Promotes tumor aggressiveness [34]. | Associated with disease progression. |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (MDA-MB-231) | High expression associated with better outcomes [35]. | Information not specified in search results. | Knockout increases 3D invasion and chemosensitivity [35]. | Cell-line specific role; effects are not generalizable [35]. |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (MDA-MB-468) | High expression associated with better outcomes [35]. | Information not specified in search results. | Knockout increases cell viability and drives chemoresistance [35]. | Cell-line specific role; differential mTOR/Akt activation [35]. |

| Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) | Cytoplasmic expression in 34.6% of patients; correlated with migration [36]. | Information not specified in search results. | Promotes migration and invasion [36]. | Independent unfavorable prognostic factor in buccal mucosa carcinoma [36]. |

| Glioblastoma (GBM) | Commonly overexpressed [37]. | Information not specified in search results. | Contributes to angiogenesis, tumor progression, and pharmacological resistance [37]. | Targeted in drug delivery systems; silencing enhances radiosensitivity [37]. |

| Non-Cancerous (Hek293T Embryonic Kidney) | Lower basal activity; distinct regulatory response [33] [34]. | Normal regulatory feedback maintained [33]. | Silencing STFA decreases cell viability [34]. | Represents a non-malignant regulatory baseline [33] [34]. |

A key finding across studies is the fundamental disruption of the CTSB-STFA regulatory loop in cancer cells compared to non-cancerous cells. In embryonic renal cells (Hek293T), CTSB and STFA exist in a tightly regulated balance. However, in renal cancer cells (769-P) and prostate cancer cells (Du145), this feedback mechanism is impaired. Research demonstrates that exogenously increasing CTSB levels can significantly alter STFA expression in cancer cells, suggesting a corrupted feedback mechanism influenced by CTSB's enzymatic activity [33]. This dysregulation creates a proteolytic environment conducive to invasion and metastasis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Protocol 1: Investigating the CTSB-STFA Regulatory Interplay

This methodology is central to understanding the expression patterns summarized in Table 1.

- 1. Cell Culture and Transfection: Non-cancerous embryonic renal cells (Hek293T), renal cancer cells (769-P), and prostate cancer cells (Du145) are cultured. Cells are transfected with plasmids for CTSB gain-of-function (overexpression), loss-of-function (silencing), or treated with biochemical inhibitors [33].

- 2. Gene Expression Analysis: Total RNA is extracted 48 hours post-transfection. mRNA expression levels of CTSB and STFA are quantified using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) [33] [34].

- 3. Protein Expression and Activity Assay: Protein lysates are analyzed by Western Blot to detect CTSB and STFA protein levels. CTSB enzymatic activity is measured using fluorogenic substrates (e.g., Z-Phe-Arg-AMC) [34].

- 4. Subcellular Localization: Immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy are used to determine the cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of CTSB and STFA. Colocalization analysis confirms direct protein interaction [34].

Protocol 2: Assessing CTSB in Cell Migration and Invasion

- 1. Gene Knockdown: Oral cancer cell lines (e.g., OC2, CAL27) are treated with CTSB-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) or a non-targeting control siRNA for 48 hours. Knockdown efficiency is confirmed by Western Blot [36].

- 2. Transwell Migration Assay: After knockdown, cells are harvested and seeded into the upper chamber of a Transwell insert in serum-free medium. The lower chamber contains medium with serum as a chemoattractant. Cells are incubated for 48 hours to allow migration [36].

- 3. Analysis: Migrated cells on the lower surface of the membrane are fixed, stained, and counted under a microscope. A significant reduction in migrated cells in the CTSB-knockdown group indicates its role in promoting migration [36].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams visualize the key regulatory pathways and experimental workflows described in the research.

Diagram 1: CTSB-STFA regulatory interplay in cancerous vs. non-cancerous contexts. In non-cancerous cells, a homeostatic balance is maintained. In cancer, this feedback is impaired, leading to a proteolytic imbalance that drives invasion and metastasis [33] [34].

Diagram 2: A generalized experimental workflow for analyzing CTSB function. Studies typically involve genetic manipulation of CTSB (knockdown or overexpression), followed by validation at molecular and functional levels to assess its impact on cancer phenotypes [34] [35] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their applications in CTSB research, as utilized in the cited studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Cathepsin B Investigation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CTSB siRNA / shRNA | Knocks down CTSB gene expression to study loss-of-function phenotypes. | Used to inhibit oral cancer cell (OC2, CAL27) migration [36] and to study TNBC cell invasion and chemosensitivity [35]. |

| CTSB Expression Plasmids | Overexpresses CTSB to study gain-of-function effects and regulatory mechanisms. | Employed to demonstrate the feedback regulation of STFA in cancer cell lines [33]. |

| Fluorogenic Substrates (e.g., Z-Phe-Arg-AMC) | Measures CTSB enzymatic activity. The substrate emits fluorescence upon cleavage. | Used to quantify CTSB activity in various cell lines following STFA modulation [34] [38]. |

| Specific Inhibitors (e.g., CA074, E-64) | Irreversibly or reversibly inhibits CTSB activity to probe its catalytic function. | CA074 used for structural studies and specificity profiling [39]. E-64 used in inhibition kinetics with immobilized CTSB [38]. |

| Anti-Cathepsin B Antibodies | Detects CTSB protein levels and localization via Western Blot, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence. | Used for protein level validation in knockdown/overexpression experiments and for subcellular localization studies [34] [36]. |

| Transwell Chambers | Assesses cell migration and invasion capabilities in vitro. | Demonstrated that CTSB knockdown reduces the migratory capacity of oral cancer cells [36]. |

Computational and Experimental Approaches for Cathepsin B Inhibitor Discovery

Virtual screening has emerged as an indispensable computational tool in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly identify potential hit compounds from vast chemical libraries. Among the most effective strategies are ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and structure-based molecular docking. These approaches are particularly valuable for targets like cathepsin B, a cysteine protease whose inhibition is a promising therapeutic strategy for conditions including Alzheimer's disease [23] [40]. Ligand-based methods extract essential chemical features from known active compounds, while structure-based techniques leverage three-dimensional protein structures to predict binding interactions. When integrated, these complementary approaches form a powerful workflow for identifying novel bioactive molecules with greater efficiency and lower costs than traditional high-throughput screening methods.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore models abstract the essential steric and electronic features responsible for a molecule's biological activity, providing a template for virtual screening. These features typically include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic regions (H), aromatic rings (AR), and ionizable groups [41]. The model development process involves identifying common chemical features from a set of known active compounds and optimizing the model to maximize its ability to discriminate between active and inactive molecules [41].

In a study targeting 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (17β-HSD2), researchers developed three complementary pharmacophore models using structurally diverse training compounds. These models collectively achieved 87% sensitivity in retrieving known active compounds while excluding inactive ones, demonstrating the power of well-validated pharmacophore approaches [41]. The models consisted of 6-7 chemical features with exclusion volumes defining steric constraints, and when applied to screen over 200,000 compounds, they identified 1,531 hits (0.75% of the database), illustrating effective enrichment [41].

Structure-Based Molecular Docking

Molecular docking predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule when bound to a protein target, estimating binding affinity through scoring functions. This method requires knowledge of the protein's three-dimensional structure, either from experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, NMR) or homology modeling [23] [42]. Docking algorithms typically employ search algorithms (e.g., Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm in AutoDock) to explore possible binding conformations and scoring functions to rank them by predicted binding energy [23].

For cathepsin B inhibition studies, docking simulations have revealed critical interactions with active site residues including Gln23, Cys29, His110, His111, His199, and Trp221 [23]. These precise molecular insights enable rational inhibitor design and optimization beyond what ligand-based methods alone can provide.

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

The most effective virtual screening strategies combine both approaches in a sequential workflow to leverage their complementary strengths as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Integrated virtual screening workflow combining ligand-based pharmacophore modeling (green) and structure-based docking (blue) with key filtering steps.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of virtual screening approaches

| Feature | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore | Structure-Based Docking |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Requirement | Known active ligands | Target protein 3D structure |

| Key Advantages | Does not require protein structure; Can identify diverse chemotypes | Provides atomic-level binding insights; Can design novel scaffolds |

| Limitations | Dependent on quality/ diversity of known actives | Limited by scoring function accuracy; Computationally intensive |

| Typical Hit Rate | 0.1-1.0% of screened database [41] | 1-10% of pre-filtered compounds [42] |

| Key Software Tools | LigandScout, MOE, Discovery Studio | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD |

| Best Applications | Target with known ligands but no structure; Scaffold hopping | Structure-rich targets; Binding mode prediction |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model Development

The development of a high-quality pharmacophore model requires careful curation of training compounds and rigorous validation as shown in Figure 2.

Step 1: Training Set Compilation

- Select 5-30 known active compounds with structural diversity and potency data (e.g., IC₅₀ values)

- Include confirmed inactive compounds for model validation [41]

- For cathepsin B models, 24 known inhibitors of both natural and synthetic origin were used [23]

Step 2: Molecular Feature Alignment

- Use software such as LigandScout or MOE to identify common chemical features

- Align conformations of training compounds to maximize feature overlap

- Define feature tolerances and exclusion volumes based on molecular superimposition [43]

Step 3: Model Validation

- Test model against decoy sets containing known active and inactive compounds

- Calculate sensitivity (ability to find actives) and specificity (ability to exclude inactives)

- Optimal models achieve high sensitivity (>0.8) while maintaining high specificity [41]

In carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitor discovery, a validated 4-feature pharmacophore model containing two aromatic hydrophobic centers and two hydrogen bond donor/acceptor features successfully identified novel inhibitors with nanomolar potency [43].

Structure-Based Docking Protocol

Step 1: Protein Preparation

- Obtain 3D structure from PDB (e.g., 1CSB for cathepsin B) [23]

- Remove water molecules, add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges

- Define flexible residues if using induced fit docking approaches

Step 2: Ligand Preparation

- Generate 3D conformations with tools like Open Babel or LigPrep

- Assign proper protonation states at physiological pH

- Define rotatable bonds for conformational sampling

Step 3: Docking Execution

- Set up grid box encompassing the binding site of interest

- Run docking simulations with multiple poses per ligand (typically 10-50)

- Use scoring functions (Vina, ChemScore, etc.) to rank binding affinities

Step 4: Pose Analysis and Selection

- Cluster similar binding poses

- Analyze key protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-π stacking)

- Select top-ranked poses with complementary interactions to binding site

For cathepsin B inhibitors, this approach identified critical interactions with the catalytic dyad (Cys29 and His199) and other binding pocket residues [23] [40].

Advanced Integration with Machine Learning and AI

Emerging approaches are incorporating machine learning and deep generative models to enhance virtual screening. The CMD-GEN framework bridges ligand-protein complexes with drug-like molecules using coarse-grained pharmacophore points sampled from diffusion models [44]. This hierarchical architecture decomposes 3D molecule generation into pharmacophore point sampling, chemical structure generation, and conformation alignment, effectively addressing instability issues in molecular conformation prediction.